ABSTRACT

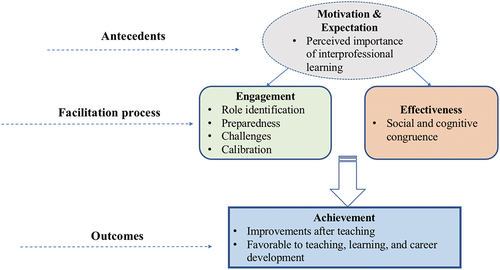

Enhancing health professional students’ effective learning and collaborative practice requires a deep understanding of strategies for facilitating interprofessional learning. While faculty members and clinical preceptors are recognized as facilitators in interprofessional education (IPE), there is limited knowledge about the impact of student facilitators’ engagement in IPE. Accordingly, this study aims to explore the perceptions and experiences of student facilitators in IPE. Thirteen student facilitators were recruited to lead an interprofessional learning program, and they were subsequently invited to participate in one-on-one interviews. An interview guide was developed to explore their motivations, expectations, engagement, effectiveness, and achievements in IPE facilitation. Thematic analysis was conducted using MAXQDA software to analyze the student facilitators’ experiences and perceptions. Eight interviewees from various disciplines, including Medicine, Nursing, Pharmacy, Speech and Hearing Sciences, and Social Work, took part in the study. The findings revealed that student facilitators highly valued their IPE facilitation experience, which aligned with their expectations and led to the creation of social networks, increased confidence, improved understanding of other professions, and the development of lifelong skills. Furthermore, the student facilitators demonstrated cognitive and social congruence by establishing a relaxed learning environment, displaying empathetic and supportive behaviors, and using inclusive language to engage IPE learners in group discussions. This study provides a comprehensive understanding of the role of student facilitators in IPE, contributing to the evolving literature on IPE. A conceptual framework was developed to explore the entire facilitation experience, encompassing the motivations and expectations of student facilitators, their engagement and effectiveness, and the observed achievements. These findings can inform the development of peer teaching training in IPE and stimulate further research in identifying relevant facilitator competencies for optimal delivery of IPE.

Introduction

In light of the increasingly complex healthcare setting and system, the collaboration of diverse health professionals has been shown to provide high-quality patient care and maintain healthcare service provision [Citation1]. Interprofessional education (IPE) has emerged as a key component in training future healthcare professionals, emphasizing effective collaboration for patient-centered care [Citation2,Citation3]. Healthcare professional students are also expected to be collaborative-practice ready and possess interprofessional competencies before they enter the clinical setting and healthcare workplace [Citation4]. By bringing together students from different healthcare disciplines, IPE aims to enhance learners’ core interprofessional competencies and improve understanding of the roles and responsibilities of different healthcare professionals [Citation5]. In this regard, identifying strategies for facilitating interprofessional learning is crucial for enhancing students’ effective learning and collaborative practice. However, facilitating interprofessional learning presents challenges due to professional differences and hierarchies within the learner group [Citation6,Citation7]. IPE facilitators, who are regarded as the gatekeepers within the learner groups, play a vital role in determining group dynamics, student engagement, and effective learning. Faculty members and clinical preceptors are commonly recognized as facilitators [Citation8]; however, a shortage of faculty members is regarded as one of the obstacles to IPE provision [Citation9,Citation10]. Consequently, incorporating approaches like peer teaching, which reinforce key concepts in the curriculum while requiring fewer faculty resources, can be beneficial for educators and practitioners seeking to overcome specific barriers to delivering IPE [Citation11,Citation12].

Peer teaching, initially proposed in medicine by Whitman and Fife [Citation13], has become increasingly popular as students actively take on teaching and facilitation roles [Citation14,Citation15]. It is considered one of the most valuable teaching methods in medical education because it benefits both peer teachers and learners [Citation16]. In light of the numerous benefits associated with peer teaching, such as addressed faculty manpower shortages, increased learner engagement, and improved knowledge retention, other health professions have also been actively exploring and implementing peer teaching models to enrich student learning experiences [Citation17,Citation18]. Extensive research in the literature has solidly established the value of peer teaching in health professions education [Citation18–20]. A systematic review, examining 44 studies, concluded that peer teaching in health professions education has a significant positive impact on improving procedural skills and yields comparable results to conventional teaching methods in acquiring resuscitation skills [Citation18]. Moreover, another review study, which encompassed findings from 45 studies, highlighted that peer teaching not only enhances knowledge retention but also fosters the development of professional skills, leadership capabilities, communication proficiency, and confidence among peer teachers [Citation19]. These studies collectively emphasize the substantial benefits of incorporating peer teaching approaches in health professions education. Furthermore, research indicates that cognitive and social congruence are crucial factors for an impactful peer teaching experience among students and student tutors [Citation21,Citation22] and serve as enablers of medical student learning [Citation23]. Cognitive congruence refers to the shared knowledge framework between learners and teachers [Citation14,Citation21]. Social congruence, on the other hand, involves peer teachers and learners sharing similar social roles [Citation21,Citation24], which creates an easy and safe learning environment [Citation14]. This allows learners to express their thoughts more freely compared to interactions with professional teachers or faculty members [Citation25]. Peer teaching offers benefits such as creating a relaxed and stimulating learning environment and improving understanding of students’ learning difficulties, as highlighted by a systematic review [Citation26]. The qualitative study by Loda et al. [Citation27] revealed that social congruence, characterized by the establishment of psychological safety between tutors and tutees, is evident in the development of trust between tutees and student tutors, who also demonstrate empathic and supportive behaviors. Together, the presence of both cognitive and social congruence impacts the learning environment, group dynamics, and the approach learners take to acquiring knowledge and skills [Citation28]. Moreover, both social and cognitive congruence are recognized as important and highly valued factors within the peer teaching experience [Citation29]. However, the extent to which the peer teaching mode can demonstrate social and cognitive congruence in engaging health professional learners within the context of IPE remains underexplored.

The feasibility and application of peer teaching in the field of medical education suggest its potential adaptation in the context of IPE [Citation10]. In IPE, student facilitators are students who receive facilitation and teaching training to guide and support their peers in interprofessional learning activities. It is crucial to have facilitators in IPE who can serve as role models for interprofessional leadership, establish a supportive learning environment, and foster acceptance and trust in interprofessional practice [Citation30]. By doing so, facilitators can effectively scaffold students’ learning and encourage their active engagement and ownership of the learning process. Leveraging their IPE or collaborative practice experiences, student facilitators have the potential to foster learners’ engagement and create a collaborative and inclusive learning environment. In the context of IPE, small group teaching emerges as the predominant approach, offering an effective mechanism to facilitate interprofessional learning in both classroom and clinical settings [Citation31]. This approach enhances teaching flexibility and promotes student engagement, thereby facilitating IPE effectively [Citation9,Citation31]. However, empirical evidence supporting the applicability of student facilitators in IPE is lacking; how they facilitate and what strategies they use; whether IPE student facilitators can demonstrate social and cognitive congruence to engage learners is still under-explored; and how the facilitation experience affects the learning outcomes of learners and their own development remains unclear [Citation30]. Furthermore, the current literature primarily focuses on the learners’ perspectives, leaving a gap in understanding the perceptions and experiences of student facilitators in IPE [Citation32,Citation33].

To bridge these gaps, this study aims to explore the perceptions and experiences of student facilitators in IPE. Accordingly, there are four research questions that were proposed:

What are the motivations and expectations of student facilitators in IPE?

How are the student facilitators engaged in IPE teaching activities?

How are cognitive and social congruences operationalized in IPE peer facilitation?

What impact will facilitating students in IPE have on student facilitators’ own collaborative perceptions, attitudes, knowledge, skills, and career development?

Methods

In this qualitative study, an interpretivist paradigm was employed to explore the teaching experiences of student facilitators in IPE.

Context

This study was derived from an IPE project at a university in Hong Kong. The IPE project aimed to promote collaboration-related behaviors among health professional students, which involved learners from various disciplines, including Medicine, Nursing, Pharmacy, Social Work, Chinese Medicine, Physiotherapy, Food and Nutritional Science, Clinical Psychology, and Speech and Hearing Sciences. Six teaching modules were designed for the IPE project, with learners divided into 20 to 37 teams across the modules (Appendix 1). Each team consisted of around 10 individuals from different disciplines. During the IPE course, learners were formed into different teams and participated in group discussions guided by a facilitator.

Participants

The recruitment for the study started in January 2023 by using university mass email to recruit student facilitators, along with the introduction of the IPE program. Purposive sampling was utilized to ensure a diverse range of participants with different backgrounds and experiences in IPE. Students who are health professions students (e.g., medicine, nursing, pharmacy, social work, and others) with or above year 3 could join as student facilitators. Ultimately, there were 13 students who participated in IPE as facilitators.

Before participating, they were invited to take part in an online peer teaching program that included a series of modules and assignments, combining synchronous and asynchronous modes, to provide didactic training on fundamental knowledge, facilitation techniques, and strategies (). Briefing and debriefing sessions related to IPE learning modules were provided before and after the facilitating sessions, respectively. We had a pool of trained facilitators to draw from for each face-to-face session. Facilitators were required to guide the group discussions for approximately 90 minutes per session.

The overarching role of student facilitators in IPE is to ensure that learners engage in team discussions where ideas from all disciplines are heard. They also observed group dynamics, ensuring balanced participation and addressing any dominance or passivity during discussions. During the process of care planning, student facilitators reinforced the importance of understanding how different areas of expertise can work together to provide holistic and coordinated care. Learners were reminded to prioritize team discussions before integrating ideas into the care plan. By following these steps and facilitation techniques, the goal was to create an inclusive and collaborative learning environment where learners could effectively apply interprofessional principles and enhance their understanding of teamwork in healthcare settings.

Data collection

After the IPE teaching program, all 13 facilitators were invited to participate in the one-on-one semi-structured interview. Ultimately, eight student facilitators, consisting of five females and three males, agreed to participate in the research. The student facilitators represented various disciplines, including four from Nursing (three students in Year 4 and one in Year 5), one graduate student from Social Work, one student in Year 5 from Speech and Hearing Sciences, one student in Year 3 from Pharmacy, and one student in Year 3 from Medicine.

Prior to the interview, the interviewer (i.e., QH) reiterated the research purpose and ethics. The interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim to ensure accuracy in capturing the participants’ responses and expressions. Using the interview guide (Appendix 2) as a prompt while allowing interviewees the flexibility to discuss their experiences and perspectives. Ethics approval was granted to this study by the Institutional Human Research Ethics Committee, with informed consent obtained from all interviewees prior to their involvement. Participants were informed that their participation was completely voluntary. Anonymity and confidentiality of participants were maintained, and ethical guidelines from relevant research ethics committees were followed.

Data analysis

The conversations between the interviewer and the student facilitators were transcribed verbatim. Following an interpretive approach, two researchers (QH and JL) conducted a thematic analysis of the student facilitators’ talks using MAXQDA [Citation34]. Both of these researchers have backgrounds in social science and have no conflicts of interest with student facilitators. Therefore, they approach the interviews and data analysis as objective observers, providing unbiased perspectives.

At the first stage, the two researchers conducted inductive coding [Citation34] on one of the transcribed interviews separately and identified some preliminary themes. At the second stage, the researchers coded the rest of the transcriptions recurrently based on the initial code system for two rounds to capture other themes. During this stage, the researchers worked in a collaborative manner to ensure the consistency of the themes, sub-themes, and codes. At the third stage, the two researchers reached consensus on the code system by refining the themes and codes before applying the third round of coding to the transcriptions. Note that the eight facilitators are assigned the pseudonyms F1, F2, F3, F4, F5, F6, F7, and F8 in the following texts for quoting their speeches.

To enhance the trustworthiness of the findings, we employed a strategy of member checking, where participants were given the opportunity to review and verify the accuracy of their interview transcripts. Additionally, reflectivity was maintained by the research team through the analysis by discussing the established assumptions, which process was employed to minimize bias and ensure the credibility and rigor of the study. In reporting the findings of this qualitative research, the study followed the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) [Citation35], demonstrating a commitment to maintaining rigor and credibility.

Results

We have summarized the findings of the interviews to present the perceptions and teaching experiences of student facilitators in IPE. The summary includes the identified themes, subthemes, and codes, which are presented in . A total of five themes and 17 sub-themes were identified during the analysis. To gain a comprehensive understanding of the impact of peer facilitation in IPE, the findings were organized chronologically, starting with the motivation and expectations of student facilitators before the facilitation session. This was followed by an exploration of their engagement and the effectiveness of their facilitation during the session. Lastly, the changes and improvements observed in the student facilitators after the facilitation concluded were discussed.

Table 1. Summary of the themes, sub-themes, and codes for the qualitative data.

Theme 1: motivations and expectations for being a student facilitator

We explored student facilitators’ motivation in two dimensions: intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. We found that seven interviewees reported intrinsic motivations, while three interviewees disclosed their extrinsic motivations. In intrinsic motivations, personal interests play a major role aside from time availability. Some student facilitators believe that peer teaching is a meaningful experience or an opportunity for them to learn from other disciplines. One facilitator’s quote is as follows:

The first motivation is just that I want to try more different roles, and then, and I feel like it is kind of interesting, as a peer or as a student, I want to kind of guide or have another role, like a different role with other students. So I just actually want to experience how it is. (F6)

The few extrinsic motivations encompass gaining teaching experience and improving communication skills. Two facilitators (F2 and F5) particularly mentioned they wanted to enhance their CVs for future teaching careers. One of the quotes is as follows

I can put it on my CV, or I can tell other people that I’ve joined this program before, so maybe I’m able to do the teaching work as well, like the PBL. (F5)

In terms of expectations towards serving as student facilitators, they generally foresaw two categories of expectations. Some expectations focus on knowledge acquisition, which exclusively includes learning discipline-specific knowledge. Another aspect is skill development that comprises collaboration, communication, and leadership skills, among which communication skill development is most favored by the learners because it is most frequently mentioned when they talk about their expectations. One student facilitator expressed the wish to enhance communication skills:

And about my experience, I think I will expect it to be an opportunity for me to… Because I haven’t been a facilitator in any activity before, I think it is a chance for me to learn how to be a peer facilitator, because a peer facilitator is different from a teacher. The teacher focuses on teaching the student, and the peer facilitator is more focused on how to facilitate communication between the peers. (F4)

Furthermore, student facilitators also recognized the importance of interprofessional learning, which triggered their further engagement in facilitation. They valued IPE in three regards, which include developing a sense of collaboration in clinical settings, career development, and facilitating critical thinking. An interviewee (F5) believes ‘it is important for [them] to learn how to communicate with people from different professions’ when he foresees his future clinical work requiring collaboration from other professions. Another student facilitator elaborated on why IPE is important for career development:

I think it is quite important, because in the future we also need to collaborate with all sorts of healthcare professionals, so I think it should be a very precious opportunity for me to learn and also to stimulate the future working environment. (F1)

To sum up, the long-term benefits are the reason behind the facilitators’ perceived importance of IPE, which echoes their motivation and expectation of developing skills and knowledge that persist over time.

Theme 2: engagement in IPE facilitation

An interesting dynamic for student facilitators was managing their dual roles as facilitators and learners. During some IPE modules, they took on a facilitator role, guiding discussion and activities. Yet in other modules, they became learners again. To better understand the identity shift process, we inquired about their perceptions of the two different roles. The major difference is that facilitators focus on the group as a whole, while learners focus on their individuality within the group. As they shift to the facilitator role, they become attentive to different perspectives from the team while realizing the responsibility of monitoring and facilitation. Interviewee F3 described the role shift: ‘But as a facilitator, I need to focus on the team dynamics and how to facilitate their discussion so that they can work together.’ Most were able to accurately differentiate between these two identities and associated responsibilities. Some drew upon previous experiences, like peer tutoring, to understand their facilitator duties.

Two facilitators felt the transition stressful or challenging. They struggled to establish credibility among classmates who were also the learners in their group, but eventually they found the identity shift rewarding, enjoying the chance to take charge of their peers’ learning. One facilitator said the following regarding her mental state before the facilitation:

I think in the beginning I was pretty stressed and nervous because I didn’t know what to expect. (F8)

After the teaching, this facilitator reported the following:

After I go into the task and join my time of being with the students, I actually find it quite rewarding and enjoyable, because I feel like a student, too, when I sit in the group and do all the tasks with them. (F8)

During the interview, the facilitators reported their experiences and perceptions of the complete teaching process from the beginning to the end. Four findings emerge from the facilitators’ reflections on their preparation for the facilitation. The first is that four facilitators (F1, F4, F5, and F7) would review the faculty-provided peer-teaching training materials before the first session. The second one is that F2 and F3 would use previous interprofessional learning experience as guidance. F1 and F6 reported that they would review some lecture notes and literature about the content knowledge of the teaching subjects. One thing rarely reported yet noteworthy is their emotional readiness. Only one student facilitator (F8) reported rehearsing a relaxed and open mental state when she prepared for the teaching. The interviewee disclosed the following:

And if you ask, what do I have to prepare, I think, to be relaxed and have an open mind, and really to just expect to have fun, because I think the ice-breaking game really helps to get familiar with each other, and after having some laugh, I think it’s easier to talk to the students and among themselves, too. (F8)

Through the progression of facilitation, the student facilitators realized some challenges. Among the six identified challenges, the most reported is having trouble adjusting group dynamics by half of the facilitators (F1, F4, F5, and F6). For example, one facilitator encountered frequent inactive dynamics in the tutorial groups:

It is quite difficult to make the students in a group talk. Because I have quite a lot of experience that they are just sitting there and doing their own work, but not really communicating to each other, and even that I can try to invite them to talk, but they just talk a few words, but then go back to normal. (F4)

Some found it tough guiding healthcare planning and understanding the jargon or concepts outside the facilitators’ realms of professions. Other less reported challenges include selecting group leaders while the learners are reluctant to claim extra responsibilities, resolving technical issues with the learning management systems, and jumping between two overlapping sessions.

After the teaching sessions, the facilitators had a calibration of their teaching performance through self-reflection to aim for improvement. They considered how to engage the learners, how to guide the process more smoothly, and how to adjust the mood of the discussions. Two student facilitators (F1 and F6) mentioned that they would set up role models after communicating with other facilitators about the teaching performance.

So, like, I was a student in her group in the IPE module. She really led the discussion so well, so I was trying to learn from her. What she actually did was try to ask the students more questions by asking students from each discipline to explain more about the choice of MC questions and also try to explain the concept to other groupmates. So I think she has led the discussion so well. So I could learn from her, so I think that’s my reflection. (F1)

Theme 3: effectiveness of IPE facilitation

The student facilitators demonstrated cognitive and social congruence in engaging IPE learners. In terms of social congruence, the following sub-themes could be identified: relaxed learning atmosphere, not intervening or dominating, ice-breaking, encouragement, understanding difficulties, and empathic and supportive behaviors. Among them, a popular strategy is to show empathy and supportive behaviors towards IPE learners. They were able to put themselves in the learner’s place. One quote below from the interviewee (F5):

So when I enter the room, I tell them I know there may be many overwhelming steps. I know it’s very late, and I know you want to go home, but I’m here to help you, so I know it may be difficult, but I will help you step by step to finish this program.

Additionally, if the learners are not communicating, all the student facilitators except F8 mentioned they will encourage and invite learners to share their opinions to warm up discussions. Icebreaking is also another effective strategy when IPE learners get cold feet in establishing socializations. Two facilitators (F7 and F8) intentionally maintain facilitation styles that are favorable and acceptable to the learners while also stressing the importance of not over-interfering with the discussions. Additionally, understanding learners’ difficulties was recognized by F4, who stated, ‘In my opinion, the most important thing we need to have is to understand the difficulty that the students have. As a peer facilitator, it is quite easy to understand their difficulty.’

In terms of cognitive congruence, student facilitators would use similar understandable language and past learning experience to facilitate the progress of the discussion. Since some of the facilitators have prior experience with IPE as learners, they could understand and guide the process. When the learners were stuck, facilitators would initiate questions, provide prompts, and provide clarifications to guide them. For example, one facilitator would raise questions when she found the learners were too reserved to speak out:

For some time, students might be a little bit timid to ask questions, even though they don’t really understand the information being different. But then, for myself, if I see something I don’t understand, I just raise it with the group. So the students find it useful if I raise the right questions. Apparently, that’s the question that’s on their minds too. (F8)

Theme 4: improvements after IPE facilitation

After the IPE facilitation, the student facilitators experienced some positive changes in different domains. In terms of knowledge and skill acquisition, communication skills stand out as the most discussed improvement. The student facilitators predominantly reported that they have become keener on speaking up and sharing opinions with others in the IPE session, accompanied by enrichment in knowledge of other disciplines.

With regard to the attitudinal aspects, the student facilitators’ confidence was boosted when managing the group of students. Besides, they vicariously learned to see the same questions from different perspectives, breaking stereotypes that they used to hold against other professions. A facilitator described this process as follows:

I noticed that in each discipline… because you may sometimes have these stereotypes in your head that [medical] students are like that, or you’re seeing students are this way. But I noticed that there are so many different kinds of students in each discipline, and I am getting an opportunity to join them as a student and also as a facilitator. And let me get past those stereotypes as well. And I also think I will be able to collaborate better with different disciplines by knowing the way they think, or, like, what the process of approaching a problem is. And modified my confidence and also my knowledge of those disciplines. (F7)

In this interdisciplinary learning community, upon increasing communications with learners and faculty staff, the facilitators strengthened networking and friendships, which they find joyful and helpful to shape learning experiences.

Theme 5: favorable to teaching, learning, and career prospects

Six facilitators (F1, F2, F4, F5, F7, and F8) believe IPE facilitation is a beneficial experience for teaching, learning, and professional development. They can accumulate teaching experience along with presentation and facilitation skills that are deemed beneficial to their future studies as well as their long-term professional development. A facilitator described the benefit outright:

Yeah. Well, actually, after this experience, I have thought about going back to the academic field and pursuing a higher level of education to maybe teach students, too, because this is really a good experience, and I find myself enjoying this process to be with the students, to learn with the students, and that makes me think about pursuing a PhD [degree]. (F8)

The student facilitators also perceived this IPE facilitation experience as favorable to their future careers. In the context of the future workplace, the F4 and F6 felt the interprofessional facilitation experience could strengthen their awareness of collaboration, as they acknowledged its importance both in their future workplace and academic pursuits.

I think it must be a useful experience because, during your research, you must work with others many times, so it’s a good chance. Yeah, just like a group leader. (F4)

After working with them, they actually have way more than this. So I know how to use this kind of resource better when I really become a nurse. And maybe, especially for the part where the patient needs to be discharged, the plan will be written by nurses. So then I may need to refer them to different resources or different disciplines. (F6)

One of the facilitators not only learned to communicate with other professions and witness their collaboration, but she also inadvertently gained some knowledge of other professions:

I think it’s very useful for me to get to know more things about not only my profession, but maybe other health professions, and also with other healthcare professionals like doctors, nurses, and also other disciplines like Chinese medicine and physiotherapy. I think it’s great for me to learn about this, because when I listen to their discussion and some of the sharing, I can learn a bit from them. (F3)

Discussion

The current study demonstrates the spectrum of student facilitators in facilitating an IPE teaching activity. Specifically, it explores what motivates participation as facilitators (Motivation), their expected gains from the facilitator role (Expectation), how they performed facilitation skills (Engagement), methods used to enable effective learning (Effectiveness), and what they gained from the facilitation experience (Achievement). This aims to address gaps in understanding peer-assisted learning applications in IPE contexts. A conceptual framework was developed to elucidate the cognitive to behavioral process of student facilitator experiences in IPE ().

Figure 2. Conceptual framework for the analysis and illustration of the perceptions and experiences of student facilitators in IPE.

Antecedents: motivations and expectations of serving as student facilitators

Our findings revealed that student facilitators were driven by strong motivations and expectations when taking on facilitation roles. Particularly consistent with other research, e.g., Vasset et al. [Citation36], facilitators recognized IPE’s value for enriching student learning, which drives their engagement as facilitators. A prominent motivator was the interprofessional learning experiences they had as participants, echoing the findings of Lindqvist and Reeves [Citation12]. Facilitators expressed a desire to ‘pay it forward’ by guiding learners through meaningful collaborative learning, indicating a transition from ‘motivation-to-learn’ to ‘motivation-to-teach’. Additionally, facilitators desired to develop leadership, communication, and facilitation skills for their future careers, with expected knowledge and skill gains. These motivations and expectations illuminate the potentially profound impact of interprofessional learning, which may not only trigger individuals to make commitments in collaborative practice in healthcare management but even in IPE and medical education teaching. Understanding the motivation and expectations of student facilitators can help optimize the IPE instructional design for both learners and facilitators.

Engagement: performing facilitation skills in IPE

An emerging finding within the theme was facilitators navigating between learner and facilitator roles. As in medical education research [Citation37,Citation38], adopting peer teaching roles involves identification and accommodation. Here, facilitators also experienced the learner-to-facilitator shift. Despite some role-switch challenges, most recognized dual roles value perspective-taking, growth, and adaptability. With experience, differentiated yet fluid roles indicated adaptability and teaching commitment.

Apparently, readiness through planning and preparation enables effective teaching presence [Citation39]. Student facilitators are thoroughly prepared to ensure impactful sessions by studying conflict resolution, team dynamics, and health profession roles to strengthen knowledge, previewing case studies and guidelines, and reviewing notes to understand content and logistics. Additionally, they reflected on IPE attitudes to cultivate openness and enthusiasm. This knowledge, skill, and mindset preparation created engaging, collaborative IPE learning. Their commitment to preparation shows dedication to delivering meaningful IPE through self-directed learning [Citation40].

Despite enjoying the facilitation process, facilitators found leading discussions challenging, consistent with the previous research [Citation41]. Apart from logistical challenges, student facilitators faced challenges in leading discussions, managing knowledge gaps and group dynamics, and addressing passive learners and silence in group discussions. These challenges are particularly pronounced in interprofessional learning due to the complexity of communication and collaboration across disciplines. Understanding these challenges is crucial for training and supporting student facilitators.

Furthermore, self-directed learning has been advocated for effective training in medical education [Citation40]. In this study, student facilitators also adopted post-session self-reflection to enhance skills by reviewing strengths and weaknesses. They focused on less confident areas like discussion tracking, quiet learner engagement, and setting improvement goals. Self-reflection enabled continuous growth and intentional observation of role models to emulate techniques. Overall, self-appraisal was seen as indispensable for building effective IPE facilitation skills through self-directed learning [Citation40]. Additionally, imitating and learning from exceptional peer facilitators is also recognized as an effective approach.

Effectiveness: scaffolding cognitive and social congruence

Encouragingly, student facilitators in the current study demonstrated both cognitive and social congruence to engage IPE learners. In terms of cognitive congruence, the sample of student facilitators recognized learners’ difficulties and struggles and were able to clarify what was important and what key points to learn [Citation21]. Additionally, student facilitators also have a solid understanding of the roles and responsibilities of different health professions; they therefore tend to integrate prior IPE learning experience and knowledge into facilitation and articulate the benefits of working collaboratively to improve patient outcomes. Moreover, cognitive congruence was nurtured through appropriate language that is familiar to learners [Citation27,Citation42,Citation43], employing facilitation techniques to facilitate group dynamics and explain difficult concepts, such as prompts, clarification, and initiating new questions to encourage learners to voice out, which in turn built learners’ comprehension [Citation44].

Social congruence enables peer facilitators to be more supportive and empathic throughout the facilitation, and they are prone to communicate with learners in an informal manner [Citation15]. In the current study, IPE student facilitators established trust and rapport in the learning environment early on through ice-breaking activities, which can get learners on board and make them feel more confident to join the discussion at the very beginning. Additionally, encouraging learners to actively participate by providing feedback may also reflect social congruence [Citation45,Citation46]. Likewise, IPE student facilitators encouraged perspective sharing without domination or intervention, promoting active listening and respectful communication by encouraging learners to share without fear of judgment or criticism. When they observed learners getting stuck, they reinforced the focus on collaboration and requested learners to discuss within the team by using techniques such as requests, directives, and encouragement. Being empathic and supportive was the key to successful facilitation in IPE, echoing previous research [Citation47]. In the current study, student facilitators emphasized that rather than dominance, it is crucial to create an inclusive, relaxed, and collegial learning environment. Unlike uniprofessional learning, attitudinal openness toward other professions, knowledge of one’s own and others’ roles, and interpersonal skills can create an engaging interprofessional learning environment [Citation12].

The current findings demonstrate the importance of cognitive and social congruence for peer teaching [Citation48] and extend its importance and application in the IPE context with student facilitators employing acceptable and favorable means. Cognitive and social congruence facilitated the development of a collaborative and teamwork-oriented culture among learners from different disciplines, preparing them for interprofessional healthcare practice.

Achievement: skill and knowledge acquisition and career development

Our findings align with IPE outcome typologies [Citation49], and demonstrate the benefits of facilitating IPE activities for student facilitators. Facilitators experienced improvements in socialization, including building networking with students from other professions and developing collegiality between disciplines [Citation50]. Many experienced positive affective changes, exhibiting increased respect for other health professions and valuing interprofessional collaboration [Citation51,Citation52]. Knowledge-wise, facilitators gained deeper insight into their own and other professions’ scopes of practice [Citation50]. Importantly, this study demonstrates the long-term benefits of peer facilitation, with sustained improvements in confidence and perceived competence in facilitation and communication skills [Citation53].

Facilitating also advanced career trajectories by building facilitators’ interprofessional competencies and identity formation. Aligning with the previous studies (e.g [Citation54]; [Citation55]; [Citation56], some of the facilitators pointed out that their teaching skills improved (including facilitation, leadership, and presentation skills), helping them prepare as educators by intentionally integrating the teaching skills into the medical education continuum [Citation22]. Furthermore, peer teaching experience has been recognized as a crucial factor in supporting students’ professional identity formation [Citation20,Citation29,Citation57]. Our study suggests that student facilitators appeared to have consolidated their professional identities as educators, which serves as a catalyst for their future roles as health professions educators. It is also worth noting how peer teaching experiences impact students’ professional identity formation. In accordance with the previous research [Citation58], the process of professional identity formation for student facilitators was found to be challenging, as they experienced stress while taking on the role of a teacher and striving for perfection. Hundertmark et al. [Citation58] further suggested that as peer teachers gain more teaching experience, their psychological stress diminishes. In the context of current interprofessional learning, student facilitators encounter a more demanding teaching environment as they strive to understand the terminology and concepts of other disciplines, particularly some clinical jargon. However, with more teaching experience, facilitators became more effective in navigating their teaching duties and understanding the responsibilities and roles of various health professions. Additionally, all the facilitators reinforced the importance of integrating IPE into the curriculum and workplace. Despite the fact that IPE has received widespread recognition, quite a number of health professional students reported that formal interprofessional learning opportunities may still not be common in their curriculum [Citation59]. Together, the current findings contribute unique evidence that identifies the transformative outcomes of students serving as facilitators. These multidimensional impacts show that being an IPE facilitator is a mutually beneficial endeavor that advances the professional growth of the facilitators’ teaching and learning [Citation30].

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

The current study provides some insights into student facilitation in IPE, addresses literature gaps, and extends the application of peer teaching in the context of IPE. Despite the small sample size, which may limit the transferability of the findings to larger populations, the study collected rich and contextualized information beyond medical students. By incorporating perspectives from different health professional students, we were able to delve deeply into the experiences, perceptions, and insights of the participants, thereby capturing the diversity and complexities of their perspectives. Importantly, the study developed a conceptual framework that discloses the understanding of the experiences of the whole teaching process and perceptions towards IPE facilitation, which advance both theoretical and practical understanding for systematic training of student facilitators. Further research across IPE contexts and incorporating learners’ perspectives by using different approaches to collect their insights (e.g., questionnaire surveys) could provide additional insights into the effectiveness of peer facilitation in IPE [Citation60–62];

Conclusions

Our findings contribute to existing research by confirming that student facilitators play a positive role in shaping group dynamics during IPE. Moreover, this study goes beyond previous work by delving into the perceptions and experiences of student facilitators throughout the IPE learning process and examining the changes that occur after their involvement in IPE teaching. Considering the limited exploration of the engagement of peer facilitation in IPE, our study takes a proactive approach by proposing a conceptual framework that provides researchers, medical teachers, and practitioners with insights for developing effective peer facilitation training programs in IPE. It is important to recognize that the development of student facilitators is an ongoing and iterative process that necessitates continuous guidance and education. By providing thoughtful training and support, we can empower student facilitators with the necessary skills and attributes to lead interprofessional learning activities effectively. As researchers and practitioners in the field of medical education, we have a dual responsibility: not only to deliver the best possible care to patients but also to support learners in their ongoing learning and career development journeys.

Acknowledgments

Gratitude to all the student facilitators who participated in the interviews for this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Zanotti R, Sartor G, Canova C. Effectiveness of interprofessional education by on-field training for medical students, with a pre-post design. BMC Med Educ. 2015;15(1):1–14. doi: 10.1186/s12909-015-0409-z

- Reeves S, Fletcher S, Barr H, et al. A BEME systematic review of the effects of interprofessional education: BEME Guide No. 39. Med Teach. 2016;38(7):656–668. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2016.1173663

- WHO. World health statistics 2010. World Health Organization; 2010. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241563987

- Pinto A, Lee S, Lombardo S, et al. The impact of structured inter-professional education on health care professional students’ perceptions of collaboration in a clinical setting. Physiother Canada. 2012;64(2):145–156. doi: 10.3138/ptc.2010-52

- Reeves S, Perrier L, Goldman J, et al. Interprofessional education: effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;2018(8):3. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002213.pub3

- Anderson ES, Cox D, Thorpe LN. Preparation of educators involved in interprofessional education. J Interprof Care. 2009;23(1):81–94. doi: 10.1080/13561820802565106

- Reeves S, Goldman J, Oandasan I. Key factors in planning and Implementing Interprofessional Education in health care settings. J Allied Health, 2007;36(4):231–235.

- Freeman S, Wright A, Lindqvist S. Facilitator training for educators involved in interprofessional learning. J Interprof Care. 2010;24(4):375–385. doi: 10.3109/13561820903373202

- Burgess A, Roberts C, van Diggele C, et al. Peer teacher training (PTT) program for health professional students: interprofessional and flipped learning. BMC Med Educ, 2017;17(1):239–239. doi: 10.1186/s12909-017-1037-6

- Lehrer MD, Murray S, Benzar R, et al. Peer-led problem-based learning in interprofessional education of health professions students. Med Educ Online. 2015;20(1):28851. doi: 10.3402/meo.v20.28851

- Egan-Lee E, Baker L, Tobin S, et al. Neophyte facilitator experiences of interprofessional education: implications for faculty development. J Interprof Care. 2011;25(5):333–338. doi: 10.3109/13561820.2011.562331

- Lindqvist SM, Reeves S. Facilitators’ perceptions of delivering interprofessional education: a qualitative study. Med Teach. 2007;29(4):403–405. doi: 10.1080/01421590701509662

- Whitman NA, Fife JD 1988. Peer teaching: to teach is to learn twice. ASHE-ERIC Higher Education Report No. 4, 1988. ERIC.

- Ten Cate O, Durning S. Dimensions and psychology of peer teaching in medical education. Med Teach. 2007;29(6):546–552. doi: 10.1080/01421590701583816

- Yew EHJ, Yong JJY. Student perceptions of facilitators’ social congruence, use of expertise and cognitive congruence in problem-based learning. Instructional Sci. 2014;42(5):795–815. doi: 10.1007/s11251-013-9306-1

- Stephens JR, Hall S, Andrade MG, et al. Investigating the effect of distance between the teacher and learner on the student perception of a neuroanatomical near-peer teaching programme. Surg Radiol Anat (Eng Ed). 2016;38(10):1217–1223. doi: 10.1007/s00276-016-1700-3

- Choi JA, Kim O, Park S, et al. The effectiveness of peer learning in undergraduate nursing students: a meta-analysis. Clini Simul Nursing. 2021;50:92–101. doi: 10.1016/j.ecns.2020.09.002

- Zhang H, Liao AWX, Goh SH, et al. Effectiveness of peer teaching in health professions education: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nurse Educ Today. 2022;118:105499. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2022.105499

- Tanveer MA, Mildestvedt T, Skjærseth IG, et al. Peer teaching in undergraduate medical education: what are the learning outputs for the student-teachers? A systematic review. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2023:723–739. doi: 10.2147/AMEP.S401766

- Yang MM, Golden BP, Cameron KA, et al. Learning through teaching: peer teaching and mentoring experiences among third-year medical students. Teach Learn Med. 2022;34(4):360–367. doi: 10.1080/10401334.2021.1899930

- Lockspeiser TM, O’Sullivan P, Teherani A, et al. Understanding the experience of being taught by peers: the value of social and cognitive congruence. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2008;13(3):361–372. doi: 10.1007/s10459-006-9049-8

- Ten Cate O, Durning S. Peer teaching in medical education: twelve reasons to move from theory to practice. Med Teach. 2007;29(6):591–599. doi: 10.1080/01421590701606799

- Huhn D, Eckart W, Karimian-Jazi K, et al. Voluntary peer-led exam preparation course for international first year students: tutees’ perceptions. BMC Med Educ. 2015;15(1):106–106. doi: 10.1186/s12909-015-0391-5

- Kani E, Asimakopoulou K, Daly B, et al. Characteristics of patients attending for cognitive behavioural therapy at one UK specialist unit for dental phobia and outcomes of treatment. Br Dent J, 2015;219(10):501–506. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2015.890

- Bene KL, Bergus G. When learners become teachers: a review of peer teaching in medical student education. Fam Med. 2014;46(10):783–787.

- Yu T-C, Wilson NC, Singh PP, et al. Medical students-as-teachers: a systematic review of peer-assisted teaching during medical school. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2011;2(default):157–172. doi: 10.2147/AMEP.S14383

- Loda T, Erschens R, Nikendei C, et al. Qualitative analysis of cognitive and social congruence in peer-assisted learning–the perspectives of medical students, student tutors and lecturers. Med Educ Online. 2020;25(1):1801306. doi: 10.1080/10872981.2020.1801306

- Sukrajh V, Adefolalu AO. Peer teaching in medical education: highlighting the benefits and challenges of its implementation. Eur J Edu Pedagogy. 2021;2(1):64–68. doi: 10.24018/ejedu.2021.2.1.52

- Zheng B, Wang Z. Near-peer teaching in problem-based learning: perspectives from tutors and tutees. PloS One. 2022;17(12):e0278256. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0278256

- van Diggele C, Burgess A, Mellis C. Planning, preparing and structuring a small group teaching session. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(Suppl 2):462–462. doi: 10.1186/s12909-020-02281-4

- Burgess A, van Diggele C, Mellis C. Faculty development for junior health professionals. Clin Teach. 2019;16(3):189–196. doi: 10.1111/tct.12795

- Hind M, Norman I, Cooper S, et al. Interprofessional perceptions of health care students. J Interprof Care. 2003;17(1):21–34. doi: 10.1080/1356182021000044120

- Johnson AW, Potthoff SJ, Carranza L, et al. CLARION: a novel interprofessional approach to health care education. Acad Med. 2006;81(3):252–256. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200603000-00010

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- O’Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, et al. Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med. 2014;89(9):1245–1251. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000388

- Vasset F, Ødegård A, Iversen HP, et al. University teachers’ experience of students interprofessional education: qualitative contributions from teachers towards a framework. Soc Sci Humaniti Open. 2023;8(1):100515. doi: 10.1016/j.ssaho.2023.100515

- Akinla O, Hagan P, Atiomo W. A systematic review of the literature describing the outcomes of near-peer mentoring programs for first year medical students. BMC Med Educ. 2018;18(1):98–98. doi: 10.1186/s12909-018-1195-1

- Burgess A, Dornan T, Clarke AJ, et al. Peer tutoring in a medical school: perceptions of tutors and tutees. BMC Med Educ. 2016:16(1):85–85. doi: 10.1186/s12909-016-0589-1

- Fraser SW, Greenhalgh T. Complexity science: coping with complexity: educating for capability. BMJ. Complexity science. 2001;323(7316):799–803. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7316.799

- Murad MH, Coto-Yglesias F, Varkey P, et al. The effectiveness of self-directed learning in health professions education: a systematic review. Med Educ. 2010;44(11):1057–1068. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2010.03750.x

- Lindqvist S. Interprofessional communication and its challenges. In: Brown J, Noble L, Papageorgiou A, et al., editors. Clinical Communication in Medicine. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.; 2016:157–167.

- Aba Alkhail B. Near-peer-assisted learning (NPAL) in undergraduate medical students and their perception of having medical interns as their near peer teacher. Med Teach. 2015;37(S1):S33–S39. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2015.1006602

- Nestel D, Kidd J. Peer tutoring in patient-centred interviewing skills: experience of a project for first-year students. Med Teach. 2003;25(4):398–403. doi: 10.1080/0142159031000136752

- Chou CL, Masters DE, Chang A, et al. Effects of longitudinal small-group learning on delivery and receipt of communication skills feedback. Med Educ. 2013;47(11):1073–1079. doi: 10.1111/medu.12246

- Chng E, Yew EHJ, Schmidt H. To what extent do tutor-related behaviours influence student learning in PBL? Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2015;20(1):5–21. 10.1007/s10459-014-9503-y

- Tayler N, Hall S, Carr NJ, et al. Near peer teaching in medical curricula: integrating student teachers in pathology tutorials. Med Educ Online. 2015;20(1):27921–27921. doi: 10.3402/meo.v20.27921

- Dornan T, Tan N, Boshuizen H, et al. How and what do medical students learn in clerkships? Experience based learning (ExBL). Adv Health Sci Educ. 2014;19(5):721–749. doi: 10.1007/s10459-014-9501-0

- Loda T, Erschens R, Loenneker H, et al. Cognitive and social congruence in peer-assisted learning - a scoping review. PloS One. 2019;14(9):e0222224. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0222224

- Barr H, Koppel I, Reeves S, et al. Effective interprofessional education: argument, assumption and evidence. Oxford: John Wiley & Sons; 2005.

- Moore C, Westwater-Wood S, Kerry R. Academic performance and perception of learning following a peer coaching teaching and assessment strategy. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2016;21(1);121–130. doi: 10.1007/s10459-015-9618-9

- Secomb J. A systematic review of peer teaching and learning in clinical education. J Clin Nurs. 2008;17(6):703–716. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2007.01954.x

- van Diggele C, Roberts C, Burgess A, et al. Interprofessional education: tips for design and implementation. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(Suppl 2):455–455. doi: 10.1186/s12909-020-02286-z

- Karia CT, Anderson E, Burgess A, et al. Peer teacher training develops “lifelong skills”. Med Teach. 2023;46(3):373–379. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2023.2256463

- Cusimano MC, Ting DK, Kwong JL, et al. Medical students learn professionalism in near-peer led, discussion-based small groups. Teach Learn Med. 2019;31(3):307–318. doi: 10.1080/10401334.2018.1516555

- Mohd Shafiaai MSF, Kadirvelu A, Pamidi N. Peer mentoring experience on becoming a good doctor: student perspectives. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12909-020-02408-7

- Nelson AJ, Nelson SV, Linn AMJ, et al. Tomorrow’s educators … today? Implementing near-peer teaching for medical students. Med Teach. 2013;35(2):156–159. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2012.737961

- Tamachi S, Giles JA, Dornan T, et al. “You understand that whole big situation they’re in”: interpretative phenomenological analysis of peer-assisted learning. BMC Med Educ. 2018;18(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12909-018-1291-2

- Hundertmark J, Alvarez S, Loukanova S, et al. Stress and stressors of medical student near-peer tutors during courses: a psychophysiological mixed methods study. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19(1):1–16. doi: 10.1186/s12909-019-1521-2

- Acquavita SP, Lewis MA, Aparicio E, et al. Student perspectives on Interprofessional Education and experiences. J Allied Health. 2014;43(2):31E–36E.

- Dandavino M, Snell L, Wiseman J. Why medical students should learn how to teach. Med Teach. 2007;29(6):558–565. doi: 10.1080/01421590701477449

- Kerry MJ, Spiegel-Steinmann B, Melloh M, et al. Student views of interprofessional education facilitator competencies: a cross-sectional study. J Interprof Care. 2021;35(1):149–152. doi: 10.1080/13561820.2019.1709428

- Thomas J, Clarke B, Pollard K, et al. Facilitating interprofessional enquiry-based learning: dilemmas and strategies. J Interprof Care. 2007;21(4):463–465. doi: 10.1080/13561820701273216

Appendices

Appendix 1. Teaching modules in IPE

Appendix 2.

Interview guide

How do you understand IPE? Is it important from your perspective?

Do you have the same experience with interprofessional collaboration? Or are there any collaborative practice experiences or learning opportunities in your curriculum?

Why did you join the program to be the facilitator? Do you have any expectations for the peer facilitation experience?

What is the difference between a student and a facilitator? How did you accommodate the identity shift from student to facilitator?

Before each teaching session, have you prepared for the class? How did you do that?

For the overall teaching experience, have you encountered any challenges or difficulties? How do you handle them?

During the facilitation, what strategies did you use to engage students that you felt were effective?

After the teaching session, what kinds of skills did you learn?

Have you had some self-reflection after each teaching event? Like to modify your personal teaching next time?

Whether this experience (facilitating students in IPE) modifies your own collaborative practice perceptions and attitudes, increases your own knowledge or skill acquisition, or leads to changes in your own collaborative practice behavior?

Do you think such peer facilitation experiences will be useful or helpful for your future career prospects or academic learning?