ABSTRACT

Antarctic tourism has been growing increasingly and diversifying over the past two decades. In parallel, Antarctic tourism scholarship has particularly focused on tourism development and management. This industry- and policy-focused research has neglected to address how these developments affect place-making processes in Antarctica. This article is grounded in conceptual developments of ‘Arctification’, a phenomenon that appears to have significant impacts on the making of the Arctic as a place (to visit) using specific narratives in tourism. Thus, this study expands these conceptual developments to Antarctic tourism by investigating tourism’s role in place-making in Antarctica through ‘Antarctification’. Four types of narratives emerge from tourism promotion materials constituting the core of Antarctification: Antarctica as a place (1) of exploration, (2) that is wild and empty, (3) of superlatives, and (4) needing environmental stewardship and ambassadorship. The use of these narratives locks Antarctica into particular imaginaries designed to attract visitors. Identifying these dominant narratives is critical, as they may markedly impact conservation agendas, Antarctic wildlife encounters, icescapes, and heritage.

1. Introduction

Antarctic tourism has been growing increasingly and diversifying over the past two decades (Tejedo et al., Citation2022). Tourism has become pervasive in and around the continent – particularly on the Antarctic Peninsula – yet affecting the geographies and place-making of Antarctica as a whole. Nevertheless, as analyzed by Stewart et al. (Citation2017), tourism studies of Antarctica have targeted the industry’s development and management perspectives. Scholars from the social sciences, such as Antonello (Citation2017), Dodds (Citation2016), Provant et al. (Citation2021), and Schweitzer (Citation2017), have raised the critical need to shift beyond these industry- and policy-focused priorities. They urge researchers to analyze human engagements with and perceptions of the continent, aiming to better understand the processes and challenges of place-making. A few authors have explored the geographies and ethnographies of place-making in Antarctica by investigating how these processes manifest in education practices (Salazar, Citation2013), research stations’ organization (Collis & Stevens, Citation2007), and scientific communities (O’Reilly & Salazar, Citation2017) in places such as McMurdo, Scott, and Mawson stations, and King George Island. However, studies have yet to explore place-making processes through tourism.

Tourism has been described as ‘a force of spatial change […] creating geographical attractiveness’ (Hultman & Hall, Citation2012, p. 547), shaping and modifying places. Pierini (Citation2009) noted that tourist products and destinations are usually presented through positive characteristics, with descriptions interwoven with evaluations in promotional materials that construct biased identities of places, products, and experiences. Consequently, tourism discourse manipulates potential visitors (Danciu, Citation2014), leading to emotive persuasion (e.g. pleasing the aesthetic senses) and influencing decision making (Petty & Briñol, Citation2015). As noted by Weightman (Citation1987, p. 229), tourism promotion attempts to ‘mystify the mundane’, ‘romanticize the strange’, and ‘amplify the exotic’. In other words, tourism promotion aims to convince consumers that every destination is above average (see Zelinsky, Citation1988), utilizing discourse characterized by extreme language in which the mediocre, the average, and the normal are never exalted (Borra, Citation1978).

Recent research on Arctic tourism has centered on the concept of ‘Arctification’, which has gained attention primarily from Nordic scholars (see Bohn & Varnajot, Citation2021; Carson, Citation2020; Cooper et al., Citation2019; Marjavaara et al., Citation2022; Rantala et al., Citation2019). ‘Arctification’ has been defined as a social phenomenon characterized by the stereotypical production and promotion of cryospheric narratives, images, and places in the North as Arctic (Carson, Citation2020; Rantala et al., Citation2019). Scholars argue that Arctification is expressed through the language, semantics, and images used in tourism promotion materials, which create and reinforce a specific idea of the Arctic as a snowy, frozen, and uninhabited place (Bohn & Varnajot, Citation2021; Marjavaara et al., Citation2022). This results in the standardization of tourism products and experiences regarding snow and ice, neglecting the other seasons and the dynamic nature of the region (Saarinen & Varnajot, Citation2019). Arctification, however, plays a notable role in the production of the geographical attractiveness of the Arctic as a tourist destination (Varnajot & Saarinen, Citation2022). Although the Arctic and Antarctica share several geographical similarities (Hall & Saarinen, Citation2010), this phenomenon has not been explored in the context of Antarctic tourism.

Drawing on the concept of Arctification, this paper examines the phenomenon of ‘Antarctification’ in tourism. As in the case of the Arctic, a comprehensive understanding of the meanings and mechanisms of place-making induced by tourism in Antarctica is indispensable for examining tourism dynamics and their impacts on shaping Antarctica as a tourist destination. Additionally, understanding these processes is imperative for formulating effective policy-making strategies, as a limited understanding of a phenomenon or a concept may results in worse associated policies, guidelines, and regulations (Hall, Citation2005). The need for effective policies becomes even more critical in tourism, with the imperative needs for environmental sustainability (Saarinen & Varnajot, Citation2019) and for better management of tourism’s impacts on conservation agendas, wildlife encounters, icescapes, and heritage. In this research paper, we explore narratives used by the tourism industry operating in Antarctica and the implications of these on the production of Antarctica as a place.

This article is structured into four sections. The first section introduces the theories of place-making and the production of space that inform the processes of Antarctification (and Arctification). The second section presents the methodology. The third section focuses on key identified narratives of Antarctification promoted by the industry: Antarctica as a place (1) of exploration, (2) wild and empty, (3) of superlatives, and (4) needing environmental stewardship and ambassadorship. The last section discusses the implications of these narratives for the scientific community, gateway cities, and the tourism industry, offering critical considerations regarding Antarctification as a driver of place-making and the touristification of Antarctica.

2. Social spatialization and representations of space

The term ‘Arctification’ refers to a specific form of touristification taking place in the Arctic. Originally, the Circumpolar North was named after the Greek term Arktikós, designating the parts of the world that lay to the far north, beneath Ursa Major (Lopez, Citation2001). ‘Touristification’, however, is ‘understood as a complex process in which various stakeholders interfere, transforming a territory through tourist activity’ (Ojeda & Kieffer, Citation2020, p. 143). In simple terms, ‘touristification’ refers to the increase of tourism in a given geographical space (Jover & Díaz-Parra, Citation2020). In the Arctic, particularly in the European North, Arctification has led to a specific touristification, leading to the development of distinct tourism activities and experiences (e.g. dogsledding, snowmobiling, northern lights safaris) and semantics, as observed by Saarinen and Varnajot (Citation2019) and Marjavaara et al. (Citation2022), respectively. In addition, as argued by Ojeda and Kieffer (Citation2020), to study touristification (and, thus, Arctification or Antarctification), one must identify how discourses and narratives apply to a geographic area, which this article aims to accomplish for Antarctic tourism.

As a process of ongoing, geographically specific meaning making, Arctification is premised on Shields’ (Citation1991) notion of ‘social spatialization’ (Varnajot & Saarinen, Citation2022). This notion refers to the active process of producing and reproducing places’ identities through practices and discourses of social meanings associated with how spaces should and could be. Using Lefebvre’s (Citation1991) work in the Production of Space, Shields showed how idealism and materialism come together, informing how social perspectives about space play a role in the material production of space. Shields demonstrated how abstract concepts could create new spaces that confront existing ones, thereby revealing the latent social relationships within those spaces.

As Elden (Citation2004) noted, any move to conceive space as a social construct is grounded in the relationships inherent in and immanent to that space and serves to reproduce those relationships. For Lefebvre, space literally arises from these contradictions of material and mental processes. The resulting productive forces operate not merely within space but on it, while space also equally constrains them (Elden, Citation2004). By emphasizing these distinctions and relationships, Lefebvre (Citation1991) argues, ‘[S]pace is at once work and product – a materialization of “social being”’ (p. 101–102, emphasis in the original). Furthermore:

There is not the material production of objects and the mental production of ideas. Instead, our mental interaction with the world, our ordering, generalizing, abstracting, and so on produces the world that we encounter, as much as the physical objects we create. This does not simply mean that we produce reality, but that we produce how we perceive reality. (Elden, Citation2004, p. 44)

Following Lefebvre, representations of space entail conceptualizations of space as produced by people, institutions, and organizations that imagine space based on the prevailing order of society. The way space is conceived is reflected in planning, buildings, and monuments that reflect dominant forces in society, their codes, their knowledge, and the symbolism legible in spatial manifestations. These representations are codifications produced by those who hold the power to manifest their ideals. Representational spaces are where people live their everyday lives. These spaces are physical material spaces, or ‘space as directly lived through its associated images and symbols, and hence the space of “inhabitants” and “users”’ (Lefebvre, Citation1991, p. 39). Being lived through, space is where time and history are qualitative, fluid, and dynamic. What keeps representations of space and representational spaces together, yet apart, are spatial practices lived directly before they are conceptualized.

As such, there is a dialectical interaction between conceived and lived spaces, between ideal and everyday representations, and between practiced and material spaces. These interactions structure both the production and reproduction of social and material relations and ensure cohesion. Hence, understanding representations of space in Antarctica can provide insights into the impacts of Antarctica as a tourist destination, as the conceived spaces of the travel industry directly impinge upon tourists’ lived experiences and spatial practices.

Tourism as polar place-making

As explained by Lefebvre (Citation1991), people’s experiences of landscapes and places are embodied and subjective. Therefore, any tourist destination can be understood as resulting from interacting natural and artificial features on the one hand (Framke, Citation2002) and people’s ascribed meanings and values on the other (Murphy, Citation2013; Young, Citation1999). Due to the absence of an indigenous or permanent population, the meanings and values associated with Antarctica are ascribed, produced, and reproduced by those who visit Antarctica for science, tourism, or other purposes. This resonates to some degree with Arctic tourism, which, according to Saarinen and Varnajot (Citation2019, p. 110), is produced ‘by outsiders, for outsiders’. When it comes to Arctification, the narratives emerging from the associated meanings and values are marked by an intensification of the region’s winter and cryospheric imaginaries, as outlined above, generating a stereotypical picture of the Arctic that is reflected in tourism products and experiences engaging with snow and ice (Saarinen & Varnajot, Citation2019). These narratives of Arctification help create expectations about what the tourist destination should be (Adler, Citation1989; Cox et al., Citation2009; Tussyadiah et al., Citation2011). In addition, since these narratives are ongoing constructions of meaning making, they are not fixed or static. Rather, they are influenced by representations, discourses, and the very materiality of place. This makes tourist destinations dynamic, transforming, and changing units of space (Agnew, Citation2011; Saarinen, Citation2004).

Furthermore, as Bystrowska and Dawson (Citation2017) recall, the values and meanings underpinning narratives constructing spaces and places are subjective and can differ among people and organizations. Place-making thereby involves both material and mental processes. Narratives express everyday sense-making, feelings of belonging, and emotional attachments to life and land. These meanings and values are articulated in various ways. Narratives used by the tourism industry, for instance, frame values and meanings through marketing, branding, and image-creation processes.

There is no clear definition of a narrative. However, as Ryan (Citation2007, p. 24) notes, ‘[M]ost narratologists agree that a narrative consists of material signs, the discourse, which convey a certain meaning (or content), the story, and fulfill a certain social function’. Consequently, narratives communicate a meaningful story to an audience. In tourism, these generally result from language, definitions, and metaphors, often associated with images or footage of destinations. Altogether, these participate in shaping spatial understanding and the making of tourist destinations (Medby, Citation2019; Tuan, Citation1991).

Antarctification

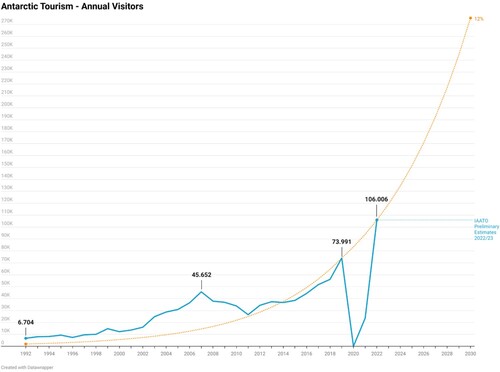

Tourism in Antarctica and, therefore, its touristification are not recent phenomena, spanning over two centuries (Snyder, Citation2007). First, it mainly consisted of curious and independent adventurers and explorers (Hall & Johnston, Citation1995; Stonehouse & Snyder, Citation2010). The first organized tour took place in 1958 (Liggett et al., Citation2011; Reich, Citation1980), and the first flights over the ‘White Continent’ from New Zealand and Australia (without landing) began in 1977 (Headland, Citation1994). Although tourism only takes place in summer (November–March), it is increasingly diversified (Lamers & Gelter, Citation2012; Liggett et al., Citation2011), ranging from seaborne tourism (e.g. expedition cruises) to land-based activities and, increasingly, air transportation, reflecting the ongoing touristification of Antarctica. Despite this diversification, seaborne tourism still represents over 95% of the Antarctic tourism market (Li et al., Citation2022). Visitor numbers have rapidly increased from 74,000 in 2019–2020 (IAATO, Citation2020) to 106,000 in 2022–2023 (IAATO, Citation2022a; ). The day-to-day management of most tourism operations is conducted by the International Association of Antarctica Tour Operators (IAATO), a voluntary self-regulating tourism body founded in 1991, while international Antarctic relations are regulated by the Antarctic Treaty System (ATS), which includes the Antarctic Treaty and its related agreements.

Figure 1. Tourist numbers in Antarctica in the past 30 years and preliminary estimates.

Ddata source: Citation2022a.

Antarctica has emerged as a last-chance tourism destination in the context of global climate change, highlighting the well-known paradox in the polar tourism literature (see Eijgelaar et al., Citation2010) regarding the high carbon emissions associated with traveling. The touristification of Antarctica and growing tourism numbers present further environmental challenges (Tejedo et al., Citation2022), including long-recognized wildlife disturbances (Erize, Citation1987), invasive species and pathogens (Frenot et al., Citation2005), and fossil fuel emissions (Farreny et al., Citation2011). Therefore, tourism actors are challenged to find a critical balance between maintaining the allure of Antarctica and the growth associated with their business models. Due to this intricate balance, many tourism scholars struggle to reconcile this dominant growth paradigm with notions of sustainability (see Bianchi & de Man, Citation2021), particularly in Antarctica. Indeed, as recalled by Boluk et al. (Citation2019, p. 859), ‘[S]ustainable tourism was the industry’s way to rationalize the consumption of the environment, commodifying it for the tourists’ gaze and enforcing its preservation as an exclusive amenity for advantaged tourists’. Building on the idea of Arctification, Antarctification can then be understood as the representation of the Antarctic through particular narratives, semantics, and imaginaries in tourism promotion, products, and experiences.

3. Methods

This article aims to identify the core narratives that constitute Antarctification. Specifically, we sampled narratives from companies operating in Antarctica utilizing IAATO’s member directory database (IAATO, Citationn.d.). As of 2023, 108 companies have joined the IAATO, either as operators or associated members. ‘Operators’ are companies working directly in Antarctica, while ‘associated members’ are tour operators or agents booking and organizing products via operators’ existing programs. As such, both operators and associated members use promotional materials, providing valuable qualitative resources on how Antarctica is produced as a place.

The analysis involved hermeneutic cycles of reading tourism companies’ online promotional materials. Generally, ‘hermeneutics’ is an interpretive methodology in which researchers seek to understand a phenomenon rather than seek explanations (Gretzel, Citation2017). Accordingly, we interpreted the narratives conveyed in the tourism promotional materials and then used abductive coding to identify emerging themes. Correspondingly, we do not attempt to label and provide a representative overview of all Antarctic narratives but instead emphasize the most prominent themes identified (see Rageh et al., Citation2013). Four interrelated narratives emerged: (1) exploration, (2) wilderness and emptiness, (3) superlatives, and (4) environmental stewardship and ambassadorship. Interestingly, our four narratives resonate with and support Nielsen’s (Citation2023) key framings of Antarctica in consumer culture, where the continent is perceived as a place for heroes, extremes, purity, and fragility.

4. Narratives of Antarctification

Narrative of exploration

The history of human exploration in Antarctica is replete with epic stories and exploits, which continue to capture media attention through news, movies, documentaries, and books, as evidenced by the recent discovery of Ernest Shackleton’s lost ship, Endurance, in March 2022. Tales such as Edgar Allan Poe’s The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket (Citation2010) or Jules Verne’s An Antarctic Mystery (Citation2006) have also furthered the narrative of exploration associated with Antarctica in collective imaginaries (Leane, Citation2012). The tourism industry has exploited these to promote Antarctica as a destination for adventure and exploration.

Tourism companies have quickly understood that Antarctica’s history of human exploration could represent a great opportunity for tourism development, utilizing the commodification of people’s representations and collective imaginaries. The use of these narratives in tourism can be traced to the launch of commercial travel on the continent. In 1966, Lars-Eric Lindblad turned the narrative of polar exploration into a commercial tourism product by organizing and structuring voyages around shore excursions and education, which still forms the basis for the ‘expedition cruise’ segment today (Snyder, Citation2007). Imaginaries from polar exploration also inspire and motivate modern travelers and lead to depictions of extreme adventures and experiences (Schillat, Citation2016), which are often used by the tourism industry. An example is the title of the tour package of the Australian-based company Aurora Expedition (Citation2019), ‘In Shackleton’s Footsteps’, aiming to recreate his epic adventure. The brochure states the following:

Thanks to the cold conditions, the well-preserved hut looks just as it did all those years ago—a fascinating place to get a feeling for the olden days of Antarctic exploration.

We are always keen to explore new territories, so if the opportunity arises, we will! That's why we call our cruises, ‘Expeditions of Exploration and Adventure’—who knows where we will go?

History comes alive as you stand at 90° South, the ultimate goal of polar explorers Amundsen and Scott. Imagine how it felt to head out across the frozen continent and into the unknown over 100 years ago. (Citationn.d.)

Narrative of wilderness and emptiness

Geographers have been fascinated by void spaces (Huijbens, Citation2005; Kingsbury & Secor, Citation2021). Even tourism studies have explored the idea of emptiness in the context of wilderness management. Saarinen (Citation2019) points out that, for tourism, the wilderness often represents an empty space where leisure activities can take place. Emptiness can also be produced, as in the context of wilderness areas, which are often viewed as pristine and untrammeled spaces (supposedly) free from negative human influences. Interestingly, these wilderness areas are actively empty of negative anthropogenic influences and are thereby the products of human societies’ governance and management (Sæþórsdóttir et al., Citation2011).

Moreover, discourses about Antarctica often present the continent as an empty and wild space (Provant et al., Citation2021). This depiction is amplified by the tourism industry, which is simultaneously becoming one of the main motives for human presence in the region. The narrative of emptiness is central to the promotion of Antarctic tourism. For example, tour operator Hurtigruten uses this narrative in its online promotional materials to encourage travel to Antarctica. The company emphasizes the continent’s emptiness, claiming this:

The vast emptiness of the southernmost continent cannot be exaggerated. When you travel to Antarctica, it’s just you, your shipmates, and the scientists and long-term travelers you meet in some settlements along the way. (Hurtigruten, Citationn.d.-a.)

Imagine a place so pristine and remote you can hear snowflakes hitting the water. (Aurora Expeditions, Citationn.d.)

Many of the diaries and published accounts of early exploration of the continent […] include myriad references to unique soundscapes of the region. These typically describe sounds produced by Antarctica’s glaciers, icebergs, and other forms of ice, its distinctive wildlife, and its highly changeable and often extreme wind conditions. (Philpott & Leane, Citation2022, p. 1)

Experience the magnificent vastness. To hear the silence. Or to have leisurely encounters with penguins without being forced to leave because others are waiting their turn. (Lindblad Expeditions, Citation2020, p. 24)

Narrative of superlatives

Antarctica is arguably a place of extremes (see Kelman, Citation2022). For example, the lowest air temperature recorded on the Earth’s surface was measured at −89.2°C in July 1983 at the Vostok station (Turner et al., Citation2009). Even though tourists might not encounter these extreme weather conditions, extreme language and superlatives often characterize the continent in tourism narratives and discourses. Although Antarctica has features that certainly make it a unique destination, the observed narratives from tourism operators expand from mere descriptions to a eulogistic and highly evaluative vocabulary filled with examples of extreme language and superlatives. For example, Antarctic Logistics & Expeditions, a company offering air transportation, logistic support, and guided expeditions to the interior of the continent, proposes that tourists will:

Embark on a journey to the remote interior of the great white continent. Antarctica is a land of extremes and only a select few have the opportunity to visit the highest, driest, windiest, coldest continent on earth! Immerse yourself in the ultimate wilderness, surrounded by pristine views, untouched spaces, and profound silence. (Citationn.d.)

Being here, surrounded by icy waters, glaciers, and icebergs big as cathedrals will probably make you feel like you’ve landed in a completely new world. Antarctica is magnificent, mesmerizing, and massive. You might need to stop for a moment to be able to take it all in. (Citationn.d.-b.)

Discover the seventh continent, as few have or ever will. Venture into the epic landscapes of remote West Antarctica, where we are sure to set foot on ice no other humans have. […] Walk among a colony of hundreds of thousands of king penguins and be among the few to have shared a beach with endemic royal penguins. […] This is wildness and wildlife at its finest, portions of which were seen before only by the likes of Scott, Ross, Amundsen, and Shackleton. (Lindblad Expeditions, Citationn.d.-a.)

Accordingly, Antarctica materializes an exaggerated representation of superlatives and extremes through tourism discourse. Ultimately, this leads to considering the continent as otherworldly, a place that should be contemplated and managed differently from other destinations, which constitutes another core element of Antarctification.

Narrative of environmental stewardship and ambassadorship

The narrative of environmental care emerged over 30 years ago and has become a prominent theme in Antarctic tourism (Splettstoesser, Citation2000). This narrative was reinforced by the establishment of the IAATO in 1991 and the ratification of the Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty in 1998. Accordingly, environmental protection has become one of the objectives of the tourism industry in and around Antarctica, manifesting mainly in two ways.

First, due to the absence of state authority in Antarctic tourism governance and management, the responsibility for enforcing and improving environmental standards largely falls on the willingness of individual Antarctic tourism actors. Hence, various voluntary initiatives and programs have emerged to promote environmental stewardship. Bennett et al. (Citation2018, p. 599) defined ‘environmental stewardship’ as follows:

Actions taken by individuals, groups, or networks of actors, with various motivations and levels of capacity, to protect, care for, or responsibly use the environment in pursuit of environmental and/or social outcomes in diverse social–ecological contexts.

Tour operating companies also utilize notions of environmental care and responsibility in their promotional materials to further develop their role as environmental stewards of Antarctica. Some examples can be observed in the following:

Lindblad Expeditions cares deeply about the planet and is proud to serve as a catalyst for meaningful change. (Lindblad Expeditions, Citationn.d.-b.)

To make sure you can speak informatively when you return home, every one of our cruises has a focus on the environment. (Hurtigruten, Citationn.d.-c)

Second, in the absence of a ‘recipient community’ socioeconomically benefiting from tourism visitation, tour operators have been actively promoting the idea of tourists caring for and protecting the environment as a way of legitimizing activities in Antarctica. This is enforced by climate change concerns, as ‘in the age of “eco-guilt,” the industry also needs to address tourists’ consciousness of the harms caused by their trips’ (Blacker et al., Citation2021, p. 784). Thus, the Antarctic experience is actively framed as a life-changing event, with tourists becoming ambassadors for the continent’s protection (Alexander et al., Citation2019; Powell et al., Citation2012). IAATO promotes its Antarctic Ambassador program, claiming ‘that visitors returning from the region have often been moved to make changes in their lives which support conservation and educate others on the importance of protecting these precious places’ (IAATO, Citation2021b).

Moreover, tour operators have been promoting citizen science activities, which can reinforce stewardship and ambassadorship commitments. Lindblad Expeditions (Citationn.d.-c.), for example, encourages its passengers to ‘[become citizen scientists] and help researchers collect data from this remote, difficult-to-reach corner of the world’. In this sense, tourists might feel more connected to the place, as they are not only enjoying holidays but also assisting scientific research, thus, being active agents of environmental protection. Hence, tourism operators claim that citizen science experiences can lead to a greater appreciation of environmental stewardship and increased engagement in pro-environmental behaviors. Nevertheless, this raises concerns regarding greenwashing, wherein the tourism industry participates in symbolic – instead of essential – research and deliberately misleads participants. This can also be termed ‘sciencewashing’.

Despite many years of active promotion by tour operators and the IAATO, the concept of ambassadorship seems to be primarily based on assumptions rather than empirical evidence. Considering the relatively high greenhouse gas contributions associated with any Antarctic visit, it has been questioned whether tourists should be perceived as ambassadors of the Antarctic environment (Amelung & Lamers, Citation2007; Farreny et al., Citation2011). Moreover, due to the estimated growth of the touristification of Antarctica and the associated emissions of greenhouse gases and pollution (see Gössling & Peeters, Citation2015; Gössling & Scott, Citation2018; Lenzen et al., Citation2018), this ambassadorship narrative is expected to face increasing challenges and become more anachronistic in the future. The emphasis on environmental stewardship and ambassadorship constitutes another core narrative of Antarctification. Through the tourism lens, Antarctica is framed as a tourist destination dedicated to environmental care and shared responsibility.

4. Concluding discussion

In this article, we contend that the touristification of Antarctica is supported by multiple narratives, making a place-making process we call ‘Antarctification’. We identified four key narratives picturing Antarctica as a place of modern exploration, wild and empty, full of superlatives, and dedicated to environmental stewardship and ambassadorship (). Our selection of narratives is by no means exclusive. However, it serves as an invitation to scholarship on the role and implications of such narratives on tourism development and the production of space in Antarctica.

Table 1. Key perspectives on Antarctification.

The process of Antarctification can be defined as an assemblage of narratives, which stand for a series of reductionist and biased elements that work together to constitute an ideal of Antarctic tourism. These elements can be called ‘toured objects’ (Wang, Citation1999, p. 351). They are sites, attractions, and ceremonies that may be simplified, embellished, or ‘adopted to the tastes of tourists’ (Cohen, Citation1988, p. 381). Identifying these narratives and their limitations () helps monitor their development and change, which is critical for the governance of Antarctic tourism due to their important implications for the representational space (e.g. tourism actors’ practices). As recalled by Merchant (Citation2003, p. 37), narratives bring ‘an ethic and the ethic gives permission to act in a particular way toward nature and other people’ (see Antonello, Citation2017). Ethical issues related to the development of tourism in Antarctica have been well highlighted in polar tourism scholarship (see Alexander et al., Citation2019; Cajiao et al., Citation2022; Eijgelaar et al., Citation2010; Powell et al., Citation2008). Yet, tourism actors often get different considerations, far from insights gained in academic discourses (Müller, Citation2015) in the Antarctic case, fueled by at least the four narrative tropes we have identified.

Place-making processes in Antarctica have traditionally been explored through the spatial organization of scientific communities in research stations. This is not surprising, knowing that scientists have long held a near monopoly on the long-term physical presence in Antarctica and, as such, have produced an authoritative narrative of the Antarctic environment (Antonello, Citation2017; Carey, Citation2019; Jaksic et al., Citation2019; O’Reilly, Citation2017). As Collis and Stevens (Citation2007) and O’Reilly and Salazar (Citation2017) demonstrated, scientific communities have been putting significant effort into making Antarctica a familiar place. For example, in the Australian Mawson station, one can walk to Market Square or along Main and Coronation streets (Collis & Stevens, Citation2007). In contrast, the growing tourism industry has been shaping Antarctica the other way around, exceptionalizing Antarctica and acting as a significant driving force to keep the Antarctic region perceived as wild and extreme. Therefore, conflicting place-making processes are currently at stake in Antarctica. On the one hand, the scientific community makes efforts to turn the continent into something homelike and familiar (see Pottier, Citation2022). On the other hand, the tourism industry locks the continent into narratives of extraordinariness, myths, and extremeness (see Urry, Citation1990).

In addition, as Antarctification tends to exalt Antarctica as otherworldly, questions regarding the identity of tourists arise. In promotional tourism materials, visitors are rarely referred to as ‘tourists’ per se but as ‘passengers’ (in the case of cruise tourism), ‘ambassadors’, ‘guests’, or even ‘explorers’. Their trip is not framed as just any sort of trip but as an expedition, an experience. By ascribing and developing particular narratives to Antarctica as a mythical, exclusive, and unique destination, people visiting the ‘White Continent’ may perceive themselves as liberated from mass tourism channels and practices. As Antarctic tourism is actively disassociated with mass tourism, a trip to Antarctica might be perceived as more acceptable from an ethical perspective (see Merchant, Citation2003). Ultimately, this deliverance of the Antarctic tourist may lead to overlooking associated issues, such as carbon emissions, the introduction of alien species, or disturbances of scientific activities (Farreny et al., Citation2011; McGeoch et al., Citation2015; O’Reilly & Salazar, Citation2017). An example of how a trip to Antarctica can be made more admissible is if one participates in citizen science activities or is assured of becoming an ambassador for protecting the environment. As such, the environmental stewardship and ambassadorship narrative can be perceived as justifying the tourism industry’s presence in this part of the world, highlighting potential greenwashing issues.

Although Antarctica is vast, with varied geographies and landscapes, Antarctification as a place-making process leads to a homogenization of the representations of the continent, overlooking regional differences and local tourism geographies. The Antarctic Peninsula, for example, concentrates over 90% of all tourism activities (Bender et al., Citation2016), while the rest of the continent remains visited by tourists only occasionally. Similar place-making consequences have been observed in the Circumpolar North following Arctification processes (see Saarinen & Varnajot, Citation2019). Even though Antarctification shapes Antarctica as a remote, wild, and challenging place to reach, it is at odds with the lived and perceived spaces of the Antarctic due to the growing number of visitors. This shift between the perceived Antarctica in tourism narratives and the materialistic tourist experience highlights the production of space through the interactions between conceived and lived spaces.

The regularly growing tourist numbers () illustrate the intensification and touristification of tourism in Antarctica. Accordingly, more companies operate in and around the ‘White Continent’, more ships able to sail the Antarctic waters are being built, and increasingly affordable products heighten tourism opportunities in the Antarctic region. As highlighted by McGee and Leane (Citation2020), this contributes to the erosion of barriers between the rest of the world and the Antarctic continent, ultimately increasing the role of gateway cities like Ushuaia (Argentina), Punta Arenas (Chile), Christchurch (New Zealand), Hobart (Australia), or Cape Town (South Africa) for providing seaborne and airborne access and support (Leane et al., Citation2021). The material linkages and routes are established through conceived purposes and ideas, including the four narratives identified in this work.

In tourism, narratives, discourses, and representations generally lead, stimulate, and direct spatial practices. For example, cruise operators’ recent greater interest in citizen science emerges from stewardship and ambassadorship narratives. The ship scheduler organized by IAATO resulted from the empty and wild narrative. Bystrowska and Dawson (Citation2017) showed how sailing conditions and shipping logistics could influence place-making in the context of expedition cruise tourism in Svalbard. Given the presence of the same cruise operators in Antarctica, our study on the production of Antarctification by the tourism industry supports and furthers Bystrowska and Dawson’s (Citation2017) claims. On the one hand, it confirms the significant role of tourism in place-making processes in polar regions. On the other hand, by conceptualizing Antarctification, this work newly illuminates the tourism industry’s modalities to produce and shape places, particularly in Antarctica, where such studies are lacking.

Nevertheless, tourism companies are not the only actors shaping places and destinations. In the Arctic, tourists, themselves, and policy makers are also driving forces of Arctification (Bohn et al., Citation2023; Bohn & Varnajot, Citation2021). Varnajot (Citation2019), for example, investigated how the Arctic is portrayed on social media and how it shapes Rovaniemi (Finland) as an Arctic destination. Similarly, Antarctification results not only from the tourism industry’s promotion and marketing strategies but also from accounts and representations by different actors describing Antarctica in specific terms, such as IAATO and tourists, themselves. Picard (Citation2015), for example, investigated the magical values that tourists ascribe to Antarctica. Future research could further explore the production of Antarctification and associated place-making processes from the perspective of tourists (e.g. through social media) and different regulatory bodies.

From a conceptual perspective, the meaning of touristification has recently shifted from a geographical concept to ideological debates associated with tourism phobia and gentrification, challenging the usefulness of the term (Jover & Díaz-Parra, Citation2020; Ojeda & Kieffer, Citation2020). Nevertheless, similar to touristification, Antarctification must be understood for its geographic concept, without ideological preconceived notions concerning tourism growth or sustainability. As such, Antarctification can serve as an efficient conceptual tool for future studies of geographical changes in Antarctic landscapes and environments, in socioeconomic dynamics and, more generally, in the relationships between tourism actors and Antarctica. The framing of place-making processes in Antarctica under the term ‘Antarctification’ is critical, as it offers a sound and context-sensitive framework for necessary policy-making strategies as well as guidelines and regulations that should be implemented considering the estimated growing touristification of Antarctica.

In the Arctic, recent studies have also shown how processes of Arctification affect and direct spatial practices in adaptation strategies to climate change and the increasing lack of a cryosphere in destinations such as Lapland (Varnajot & Saarinen, Citation2021, Citation2022). As Arctification locks the Arctic into representations of white landscapes, climate change adaptation strategies tend to address the challenges associated with disappearing snow and ice. In the context of climate change, this approach can be considered tourism maladaptation (Scott et al., Citation2022). Similarly, studying Antarctification can help better anticipate potential maladaptation strategies to future crises affecting Antarctica and the associated gateway cities dependent on the tourism industry. Corroborating this, the study of place-making through narratives developed by the tourism industry can support resilience-building strategies, adaptation, and responses to future crises.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments, as well as to our colleagues for insightful suggestions and discussions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aase, J. G., & Jabour, J. (2015). Can monitoring maritime activities in the European high arctic by satellite-based automatic identification system enhance polar search and rescue? The Polar Journal, 5(2), 386–402. https://doi.org/10.1080/2154896X.2015.1068534

- Adler, J. (1989). Travel as performed art. American Journal of Sociology, 94(6), 1366–1391. https://doi.org/10.1086/229158

- Agnew, J. (2011). Space and place. In J. Agnew & D. Livingstone (Eds.), Handbook of geographical knowledge (pp. 316–330). Sage.

- Alexander, K. A., Liggett, D., Leane, E., Nielsen, H. E., Bailey, J. L., Brasier, M. J., & Haward, M. (2019). What and who is an Antarctic ambassador? Polar Record, 55(6), 497–506. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0032247420000194

- Amelung, B., & Lamers, M. (2007). Estimating the greenhouse gas emissions from Antarctic tourism. Tourism in Marine Environments, 4(2–3), 121–133. https://doi.org/10.3727/154427307784772020

- Antarctic Logistics & Expeditions. (n.d.). https://antarctic-logistics.com/trip/antarctic-odyssey/

- Antonello, A. (2017). Engaging and narrating the Antarctic ice sheet: The history of an earthly body. Environmental History, 22(1), 77–100. https://doi.org/10.1093/envhis/emw070

- Aurora Expeditions. (2019). https://www.auroraexpeditions.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/asg73-trip-notes-aurora-expeditions.pdf

- Aurora Expeditions. (n.d.). https://www.auroraexpeditions.com.au/destination/antarctica-cruises/

- Bastmeijer, K., & Roura, R. (2004). The Antarctic Treaty System and existing legal instruments to address cumulative impacts. American Journal of International Law, 98(4), 763–781. https://doi.org/10.2307/3216699

- Bender, N. A., Crosbie, K., & Lynch, H. J. (2016). Patterns of tourism in the Antarctic Peninsula region: A 20-year analysis. Antarctic Science, 28(3), 194–203. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954102016000031

- Bennett, N. J., Whitty, T. S., Finkbeiner, E., Pittman, J., Bassett, H., Gelcich, S., & Allison, E. H. (2018). Environmental stewardship: A conceptual review and analytical framework. Environmental management, 61(4), 597–614. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-017-0993-2

- Bianchi, R. V., & de Man, F. (2021). Tourism, inclusive growth and decent work: A political economy critique. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 29(2–3), 353–371. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1730862

- Blacker, S., Kimura, A. H., & Kinchy, A. (2021). When citizen science is public relations. Social Studies of Science, 51(5), 780–796. https://doi.org/10.1177/03063127211027662

- Bohn, D., Carson, D., Demiroglu, C. O., & Lundmark, L. (2023). Public funding and destination evolution in sparsely populated Arctic regions. Tourism Geographies, 25(8), 1833–1855.

- Bohn, D., & Varnajot, A. (2021). A geopolitical outlook on Arctification in Northern Europe: Insights from tourism, regional branding and higher education institutions. In L. Heininen, H. Exner-Pirot, & J. Barnes (Eds.), Arctic yearbook 2021: Defining and mapping sovereignties, policies and perceptions (pp. 279–292). Arctic Portal.

- Boluk, K. A., Cavaliere, C. T., & Higgins-Desbiolles, F. (2019). A critical framework for interrogating the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals 2030 Agenda in tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 27(7), 847–864. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2019.1619748

- Borra, J. L. F. (1978). Semiología del lenguaje turístico: Investigación sobre los folletos españoles de turismo [Semiology of tourist language: Research on Spanish tourism brochures]. Estudios Turísticos, 57, 17–203.

- Bystrowska, M., & Dawson, J. (2017). Making places: The role of Arctic cruise operators in ‘creating’ tourism destinations. Polar Geography, 40(3), 208–226. https://doi.org/10.1080/1088937X.2017.1328465

- Bystrowska, M., Wigger, K., & Liggett, D. (2017). The use of information and communication technology (ICT) in managing high arctic tourism sites: A collective action perspective. Resources, 6(3), 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources6030033

- Cajiao, D., Leung, Y. F., Larson, L. R., Tejedo, P., & Benayas, J. (2022). Tourists’ motivations, learning, and trip satisfaction facilitate pro-environmental outcomes of the Antarctic tourist experience. Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism, 37, 100454. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jort.2021.100454

- Carey, M. (2019). Science and power in Antarctica. Progress in Human Geography, 43(2), 391–393. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132517744705b

- Carson, D. (2020). Urban tourism in the Arctic: A framework for comparison. In D. K. Müller, D. A. Carson, S. de la Barre, B. Granås, GÞ Jóhannesson, G. Øyen, O. Rantala, J. Saarinen, T. Salmela, K. Tervo-Kankare, & J. Welling (Eds.), Arctic tourism in times of changes: Dimensions of urban tourism (pp. 6–17). Nordic Council of Ministers.

- Cohen, E. (1988). Authenticity and commoditization in tourism. Annals of tourism research, 15(3), 371–386. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(88)90028-X

- Collis, C., & Stevens, Q. (2007). Cold colonies: Antarctic spatialities at Mawson and McMurdo stations. Cultural Geographies, 14(2), 234–254. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474474007075356

- Cooper, E. A., Spinei, M., & Varnajot, A. (2019). Countering ‘Arctification’: Dawson City’s ‘Sourtoe Cocktail’. Journal of Tourism Futures, 6(1), 70–82. https://doi.org/10.1108/JTF-01-2019-0008

- Cox, C., Burgess, S., Sellitto, C., & Buultjens, J. (2009). The role of user-generated content in tourists’ travel planning behavior. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 18(8), 743–764. https://doi.org/10.1080/19368620903235753

- Danciu, V. (2014). Manipulative marketing: Persuasion and manipulation of the consumer through advertising. Theoretical and Applied Economics, 21(2), 591.

- Debord, G. (1983). The society of the spectacle. Black & Red.

- Dodds, K. (2016). Foreword. In P. Roberts, A. Howkins, & L.-M. van der Watt (Eds.), Antarctica and the humanities (pp. v–vii). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Eijgelaar, E., Thaper, C., & Peeters, P. (2010). Antarctic cruise tourism: The paradoxes of ambassadorship, “last chance tourism” and greenhouse gas emissions. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 18(3), 337–354. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669581003653534

- Elden, S. (2004). Understanding Henri Lefebvre. Continuum.

- Erize, F. J. (1987). The impact of tourism on the Antarctic environment. Environment International, 13(1), 133–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-4120(87)90051-1

- Farreny, R., Oliver-Sola, J., Lamers, M., Amelung, B., Gabarrell, X., Rieradevall, J., Boada, M., & Benayas, J. (2011). Carbon dioxide emissions of Antarctic tourism. Antarctic Science, 23(6), 556–566. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954102011000435

- Fletcher, R. (2010). The emperor’s new adventure: Public secrecy and the paradox of adventure tourism. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 39(1), 6–33. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891241609342179

- Framke, W. (2002). The destination as a concept: A discussion of the business-related perspective versus the socio-cultural approach in tourism theory. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 2(2), 92–108. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250216287

- Frenot, Y., Chown, S. L., Whinam, J., Selkirk, P. M., Convey, P., Skotnicki, M., & Bergstrom, D. M. (2005). Biological invasions in the Antarctic: Extent, impacts and implications. Biological Reviews, 80(1), 45–72. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1464793104006542

- Goffman, E. (1959). The presentation of self in everyday life. Doubleday.

- Gössling, S., & Peeters, P. (2015). Assessing tourism’s global environmental impact 1900–2050. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 23(5), 639–659. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2015.1008500

- Gössling, S., & Scott, D. (2018). The decarbonisation impasse: Global tourism leaders’ views on climate change mitigation. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 26(12), 2071–2086. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2018.1529770

- Gretzel, U. (2017). #travelselfie: A netnographic study of travel identity communicated via Instagram. In S. Carson & M. Pennings (Eds.), Performing cultural tourism (pp. 115–127). Routledge.

- Haase, D., Lamers, M., & Amelung, B. (2009). Heading into uncharted territory? Exploring the institutional robustness of self-regulation in the Antarctic tourism sector. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 17(4), 411–430. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669580802495717

- Hall, C. M. (2005). Tourism: Rethinking the social science of mobility. Prentice-Hall.

- Hall, C. M., & Johnston, M. E. (1995). Introduction: Pole to pole: Tourism issues, impacts and the search for a management regime in Polar Regions. In C. M. Hall & M. E. Johnston (Eds.), Polar tourism: Tourism in the arctic and Antarctic regions (pp. 1–26). Wiley.

- Hall, C. M., & Saarinen, J. (2010). Polar tourism: Definitions and dimensions. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 10(4), 448–467. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2010.521686

- Headland, R. K. (1994). Historical development of Antarctic tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 21(2), 269–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(94)90044-2

- Huijbens, E. H. (2005). Void spaces: Apprehending the use and non-use of public spaces in the urban. [Doctoral dissertation]. Department of Geography, Durham University, England.

- Hultman, J., & Hall, C. M. (2012). Tourism place-making: Governance of locality in Sweden. Annals of Tourism Research, 39(2), 547–570. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2011.07.001

- Hurtigruten. (n.d.-a). https://www.hurtigruten.com/en-us/expeditions/stories/9-reasons-to-travel-to-antarctica/

- Hurtigruten. (n.d.-b). https://global.hurtigruten.com/destinations/antarctica/highlights-of-antarctica-2022-2023/?_hrgb=3

- Hurtigruten. (n.d.-c). https://www.hurtigruten.com/de-de/expeditions/focusthema/earth-day/

- IAATO. (2020). Antarctic visitor figures 2019–2020. https://iaato.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/IAATO-on-Antarctic-visitor-figures-2019-20-FINAL.pdf

- IAATO. (2021a). Marketing Antarctica. An advisory from IAATO for IAATO Member staff and agents engaged in marketing/public relations. https://iaato.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/IAATO_Internal-Marketing-Antarctica.compressed.pdf

- IAATO. (2021b). Antarctic ambassadorship day announced for 2022. https://iaato.org/antarctic-ambassadorship-day-announced-on-30th-anniversary-of-international-association-of-antarctica-tour-operators/

- IAATO. (2022a). IAATO overview of Antarctic tourism: 2021–22 season and preliminary estimates for 2022–23 season. XLIV ATCM17/IP042.

- IAATO. (2022b). IAATO bylaws. https://iaato.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/IAATO-Bylaws-Updated-May-2022.pdf.

- IAATO. (n.d.). Membership directory. https://iaato.org/who-we-are/member-directory/

- Jaksic, C., Steel, G., Stewart, E. J., & Moore, K. (2019). Antarctic stations as workplaces: Adjustment of winter-over crew members. Polar Science, 22, 100484. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polar.2019.100484

- Jover, J., & Díaz-Parra, I. (2020). Gentrification, transnational gentrification and touristification in Seville, Spain. Urban Studies, 57(15), 3044–3059. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098019857585

- Kelman, I. (2022). Antarcticness: Inspirations and imaginaries. UCL Press.

- Kingsbury, P., & Secor, A. J. (2021). A place more void. University of Nebraska Press.

- Laing, J. H., & Crouch, G. I. (2005). Extraordinary journeys: An exploratory cross-cultural study of tourists on the frontier. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 11(3), 209–223. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356766705055707

- Lamers, M., & Gelter, H. (2012). Diversification of Antarctic tourism: The case of a scuba diving expedition. Polar record, 48(3), 280–290. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0032247411000246

- Larsen, J. (2008). De-exoticizing tourist travel: Everyday life and sociality on the move. Leisure Studies, 27(1), 21–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614360701198030

- Leane, E. (2012). Antarctica in fiction: Imaginative narratives of the Far South. Cambridge University Press.

- Leane, E., Lucas, C., Marx, K., Datta, D., Nielsen, H., & Salazar, J. F. (2021). From gateway to custodian city: Understanding urban residents’ sense of connectedness to Antarctica. Geographical Research, 59(4), 522–536. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-5871.12490

- Lefebvre, H. (1991). The production of space. Blackwell.

- Lemelin, R. H., Stewart, E. J., & Dawson, J. (2012). An introduction to last chance tourism. In J. D. Lemelin & E. J. Stewart (Eds.), Last chance tourism: Adapting tourism opportunities in a changing world (pp. 3–9). Routledge.

- Lenzen, M., Sun, Y. Y., Faturay, F., Ting, Y. P., Geschke, A., & Malik, A. (2018). The carbon footprint of global tourism. Nature Climate Change, 8(6), 522–528. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-018-0141-x

- Li, G., Li, W., Dou, Y., & Wei, Y. (2022). Antarctic shipborne tourism: Carbon emission and mitigation path. Energies, 15(21), 7837. https://doi.org/10.3390/en15217837

- Liggett, D., McIntosh, A., Thompson, A., Gilbert, N., & Storey, B. (2011). From frozen continent to tourism hotspot? Five decades of Antarctic tourism development and management, and a glimpse into the future. Tourism Management, 32(2), 357–366. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2010.03.005

- Lindblad Expeditions. (2020). Antarctica: A how-to guide to a safe & rewarding Antarctica experience. [Former online brochure].

- Lindblad Expeditions. (n.d.-a). https://www.expeditions.com/itineraries/epic-antarctica/

- Lindblad Expeditions. (n.d.-b). https://world.expeditions.com/about/making-a-difference/

- Lindblad Expeditions. (n.d.-c). https://world.expeditions.com/destinations/antarctica/

- Lopez, B. (2001). Arctic dreams. Vintage Books.

- MacCannell, D. (1973). Staged authenticity: Arrangements of social space in tourist settings. American Journal of Sociology, 79(3), 589–603. https://doi.org/10.1086/225585

- Marjavaara, R., Nilsson, R. O., & Müller, D. K. (2022). The Arctification of northern tourism: A longitudinal geographical analysis of firm names in Sweden. Polar Geography, 45(2), 119–136. https://doi.org/10.1080/1088937X.2022.2032449

- McGee, J., & Leane, E. (2020). Antarctica looking forward: Four themes. In E. Leane & J. McGee (Eds.), Anthropocene Antarctica: Perspectives from the humanities, law and social sciences (pp. 187–189). Routledge.

- McGeoch, M. A., Shaw, J. D., Terauds, A., Lee, J. E., & Chown, S. L. (2015). Monitoring biological invasion across the broader Antarctic: A baseline and indicator framework. Global Environmental Change, 32, 108–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2014.12.012

- Medby, I. A. (2019). Language-games, geography, and making sense of the Arctic. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 107, 124–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2019.10.003

- Merchant, C. (2003). Reinventing Eden: The fate of nature in western culture. Routledge.

- Merrifield, A. (2000). Henri Lefebvre. A socialist in space. In M. Crang & N. Thrift (Eds.), Thinking space (pp. 167–182). Routledge.

- Müller, D. K. (2015). Issues in Arctic tourism. In B. Evengård, J. Nymand Larsen, & Ø. Paasche (Eds.), The new arctic (pp. 147–158). Springer.

- Murphy, P. E. (2013). Tourism: A community approach. Routledge.

- National Science Foundation. (2022). U.S. Antarctic environmental stewardship.

- Nielsen, H. E. F. (2023). Brand Antarctica: How global consumer culture shapes our perceptions of the Ice Continent. University of Nebraska Press.

- Ojeda, A. B., & Kieffer, M. (2020). Touristification. Empty concept or element of analysis in tourism geography? Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 115, 143–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2020.06.021

- O’Reilly, J. (2017). The technocratic Antarctic: An ethnography of scientific expertise and environmental governance. Cornell University Press.

- O’Reilly, J., & Salazar, J. F. (2017). Inhabiting the Antarctic. The Polar Journal, 7(1), 9–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/2154896X.2017.1325593

- Petty, R. E., & Briñol, P. (2015). Emotion and persuasion: Cognitive and meta-cognitive processes impact attitudes. Cognition and Emotion, 29(1), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2014.967183

- Philpott, C., & Leane, E. (2022). The silent continent? Textual responses to the soundscapes of Antarctica. ISLE: Interdisciplinary Studies in Literature and Environment, 29(4), 1030–1054. https://doi.org/10.1093/isle/isab025

- Picard, D. (2015). White magic: An anthropological perspective on value in Antarctic tourism. Tourist Studies, 15(3), 300–315. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468797615597858

- Pierini, P. (2009). Adjectives in tourism English on the web: A corpus-based study. CIRCULO de Linguistica Aplicada a la Comunicacion, 40, 93–116.

- Poe, E. A. (2010). The narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket. Broadview Editions.

- Polar Quest. (n.d.). https://www.polar-quest.com/trips/antarctica/fly-to-the-south-pole-20222023

- Pottier, S. (2022). Multiple identities of an Antarctic station through the appropriation of the inhabited space. The Polar Journal, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/2154896X.2022.2084914

- Powell, R. B., Brownlee, M. T., Kellert, S. R., & Ham, S. H. (2012). From awe to satisfaction: Immediate affective responses to the Antarctic tourism experience. Polar Record, 48(2), 145–156. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0032247410000720

- Powell, R. B., Kellert, S. R., & Ham, S. H. (2008). Antarctic tourists: Ambassadors or consumers? Polar Record, 44(3), 233–241. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0032247408007456

- Provant, Z., Elderbrock, E., Willingham, A., Carey, M., Antonello, A., Moffat, C., Sutherland, D., & Shahid, S. (2021). Reframing Antarctica’s ice loss: Impacts of cryospheric change on local human activity. Polar Record, 57, e13. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0032247421000024

- Quark Expeditions. (n.d.). https://www.quarkexpeditions.com/adventure-options/hiking-antarctic

- Rageh, A., Melewar, T. C., & Woodside, A. (2013). Using netnography research method to reveal the underlying dimensions of the customer/tourist experience. Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal, 16(2), 126–149. https://doi.org/10.1108/13522751311317558

- Rantala, O., de la Barre, S., Granås, B., Jóhannesson, GÞ, Müller, D. K., Saarinen, J., Tervo-Kankare, K., Maher, P. T., & Niskala, M. (2019). Arctic tourism in times of change: Seasonality. Nordic Council of Ministers.

- Reich, R. J. (1980). The development of Antarctic tourism. Polar Record, 20(126), 203–214. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0032247400003363

- Ryan, M.-L. (2007). Toward a definition of narrative. In D. Herman (Ed.), The Cambridge companion to narrative (pp. 22–36). Cambridge University Press.

- Saarinen, J. (2004). ‘Destinations in change’: The transformation process of tourist destinations. Tourist studies, 4(2), 161–179. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468797604054381

- Saarinen, J. (2019). What are wilderness areas for? Tourism and political ecologies of wilderness uses and management in the Anthropocene. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 27(4), 472–487. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2018.1456543

- Saarinen, J., & Varnajot, A. (2019). The Arctic in tourism: Complementing and contesting perspectives on tourism in the Arctic. Polar Geography, 42(2), 109–124. https://doi.org/10.1080/1088937X.2019.1578287

- Salazar, J. F. (2013). Geographies of place-making in Antarctica: An ethnographic approach. The Polar Journal, 3(1), 53–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/2154896X.2013.776294

- Schillat, M. (2016). Images of Antarctica as transmitted by literature. In M. Schillat, M. Jensen, M. Vereda, R. A. Sánchez, & R. Roura (Eds.), Tourism in Antarctica: A multidisciplinary view of new activities carried out on the White Continent (pp. 21–39). Springer.

- Schweitzer, P. (2017). Polar anthropology, or why we need to study more than humans in order to understand people. The Polar Journal, 7(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/2154896X.2017.1351783

- Scott, D., Knowles, N., & Steiger, R. (2022). Is snowmaking climate change maladaptation? Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2022.2137729

- Sæþórsdóttir, A.-D., Hall, C. M., & Saarinen, J. (2011). Making wilderness: Tourism and the history of the wilderness idea in Iceland. Polar Geography, 34(4), 249–273. https://doi.org/10.1080/1088937X.2011.643928

- Shields, R. (1991). Places on the margin: Alternative geographies of modernity. Routledge.

- Snyder, J. M. (2007). Pioneers of polar tourism and their legacy. In J. Snyder & B. Stonehouse (Eds.), Prospects for polar tourism (pp. 15–31). CABI.

- Splettstoesser, J. (2000). IAATO’s stewardship of the Antarctic environment: A history of tour operator’s concern for a vulnerable part of the world. International Journal of Tourism Research, 2(1), 47–55. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1522-1970(200001/02)2:1<47::AID-JTR183>3.0.CO;2-7

- Stewart, E. J., Liggett, D., & Dawson, J. (2017). The evolution of polar tourism scholarship: Research themes, networks and agendas. Polar Geography, 40(1), 59–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/1088937X.2016.1274789

- Stewart, E. J., Liggett, D., Lamers, M., Ljubicic, G., Dawson, J., Thoman, R., Havisto, R., & Carrasco, J. (2020). Characterizing polar mobilities to understand the role of weather, water, ice and climate (WWIC) information. Polar Geography, 43(2–3), 95–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/1088937X.2019.1707319

- Stonehouse, B., & Snyder, J. (2010). Polar tourism: An environmental perspective. Channel View Publications.

- Student, J., Amelung, B., & Lamers, M. (2016). Towards a tipping point? Exploring the capacity to self-regulate Antarctic tourism using agent-based modelling. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 24(3), 412–429. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2015.1107079

- Taylor, J. P. (2001). Authenticity and sincerity in tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 28(1), 7–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(00)00004-9

- Tejedo, P., Benayas, J., Cajiao, D., Leung, Y. F., De Filippo, D., & Liggett, D. (2022). What are the real environmental impacts of Antarctic tourism? Unveiling their importance through a comprehensive meta-analysis. Journal of Environmental Management, 308, 114634. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2022.114634

- Trilling, L. (1972). Sincerity and authenticity. Oxford University Press.

- Tuan, Y. F. (1991). Language and the making of place: A narrative-descriptive approach. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 81(4), 684–696. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8306.1991.tb01715.x

- Turner, J., Anderson, P., Lachlan-Cope, T., Colwell, S., Phillips, T., Kirchgaessner, A., Marshall, G. J., King, J. C., Bracegirdle, T., Vaughan, D. G., Lagun, V., & Orr, A. (2009). Record low surface air temperature at Vostok station. Antarctica. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, 114, D24102.

- Tussyadiah, I. P., Park, S., & Fesenmaier, D. R. (2011). Assessing the effectiveness of consumer narratives for destination marketing. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 35(1), 64–78. https://doi.org/10.1177/1096348010384594

- Urry, J. (1990). The tourist gaze. Sage.

- Van Bets, L. K., Lamers, M. A., & van Tatenhove, J. P. (2017). Collective self-governance in a marine community: Expedition cruise tourism at Svalbard. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 25(11), 1583–1599. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2017.1291653

- Vannini, P., & Vannini, A. (2022). Assembling wild nature: Icelandic wilderness as a natureculture meshwork. In J. Valkonen, V. Kinnunen, H. Huilaja, & T. Loikkanen (Eds.), Infrastructural being: Rethinking dwelling in a naturecultural world (pp. 61–84). Palgrave-MacMillan.

- Varnajot, A. (2019). Digital Rovaniemi: Contemporary and future arctic tourist experiences. Journal of Tourism Futures, 6(1), 6–23. https://doi.org/10.1108/JTF-01-2019-0009

- Varnajot, A., & Saarinen, J. (2021). After glaciers?’ Towards post-Arctic tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 91, 103205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2021.103205

- Varnajot, A., & Saarinen, J. (2022). Emerging post-Arctic tourism in the age of Anthropocene: Case Finnish Lapland. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 22(4–5), 357–371. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2022.2134204

- Verne, J. (2006). An Antarctic mystery. Mondial.

- Wang, N. (1999). Rethinking authenticity in tourism experience. Annals of Tourism Research, 26(2), 349–370. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(98)00103-0

- Weightman, B. A. (1987). Third world tour landscapes. Annals of tourism research, 14(2), 227–239. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(87)90086-7

- Williams, P., & Soutar, G. (2005). Close to the “edge”: Critical issues for adventure tourism operators. Asia pacific journal of tourism research, 10(3), 247–261. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941660500309614

- Young, M. (1999). The social construction of tourist places. Australian Geographer, 30(3), 373–389. https://doi.org/10.1080/00049189993648

- Zelinsky, W. (1988). Where every town is above average: Welcoming signs along America’s highways. Landscape, 30(1), 1–10.