Abstract

Background: The EMS Practice Analysis provides a vision of current prehospital care by defining the work performed by EMS professionals. In this manuscript, we present the National Advanced Life Support (ALS) EMS Practice Analysis for the advanced EMT (AEMT) and paramedic levels of certification. The goal of the 2019 EMS Practice Analysis is to define the work performed by EMS professionals and present a new template for future practice analyses. Methods: The project was executed in three phases. Phase 1 defined the types/frequency of EMS clinical presentations using the 2016 National Emergency Medical Services Information System (NEMSIS) dataset. Phase 2 defined the criticality or potential for harm of these clinical presentations through a survey of a random sample of nationally certified EMS professionals and medical directors. Phase 3 defined the tasks and the associated knowledge, skills, and abilities (KSA) that encompass EMS care through focus groups of subject matter experts. Results: In Phase 1, the most common EMS adult impressions were traumatic injury, abdominal pain/problems, respiratory distress/arrest, behavioral/psychiatric disorder, and syncope/fainting. The most common pediatric impressions were traumatic injury, behavioral/psychiatric disorder, respiratory distress/arrest, seizure, and abdominal pain/problems. Criticality was defined in Phase 2 with the highest risk of harm for adults being airway obstruction, respiratory distress/arrest, cardiac arrest, hypovolemia/shock, allergic reaction, or stroke/CVA. In comparison, pediatric patients presenting with airway obstruction, respiratory distress/arrest, cardiac arrest, hypovolemia/shock, allergic reaction, stroke/CVA, and inhalation injury had the highest potential for harm. Finally, in Phase 3, task statements were generated for both paramedic and AEMT certification levels. A total of 425 tasks and 1,734 KSAs were defined for the paramedic level and 405 tasks and 1,636 KSAs were defined for the AEMT level. Conclusion: The 2019 ALS Practice Analysis describes prehospital practice at the AEMT and paramedic levels. This approach allows for a detailed and robust evaluation of EMS care while focusing on each task conducted at each level of certification in EMS. The data can be leveraged to inform the scope of practice, educational standards, and assist in validating the ALS levels of the certification examination.

Introduction

Providing patient care in the prehospital setting involves performing emergency care in unique, unpredictable and dynamic environments. Over time, the challenges faced by EMS professionals evolve making it imperative to clearly understand current prehospital practice to better set the scope of practice, define educational standards and objectives, and to update the certification examination. The mechanism by which the work performed by EMS professionals is defined is through a Practice Analysis.

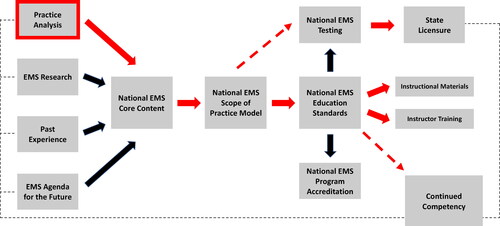

A Practice Analysis is an overview of a profession or occupation with a goal to provide a comprehensive and parsimonious view of the patterns of practice that characterize that profession (Citation1). According to the Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing, a Practice Analysis study seeks to gather “information about job duties and tasks, responsibilities, worker characteristics, and other relevant information” (Citation2). Practice Analysis serves as a significant source of validity in certification and licensure examinations designed to assess professional competence (Citation3, Citation4). For prehospital care, the first Practice Analysis was conducted by the National Registry of Emergency Medical Technicians in 1994 and at five-year intervals thereafter (1999, 2004, 2009, and 2014) to continually develop a clear and accurate representation of the current practice of out-of-hospital emergency medical care (Citation5). Additonally, the goal of the EMS Practice Analysis is not limited to defining a vision of current EMS care, but also informs the scope of practice process, informs the educational standard setting process to update initial and continuing EMS provider training, and provides the required content validity for all levels of the certification examination ().

Figure 1. The EMS practice analysis informs many aspects of the EMS educational systems in its roles as one of the key components of the system. From the EMS Education Agenda for the Future: A Systems Approach, 1999, https://www.ems.gov/pdf/education/EMS-Education-for-the-Future-A-Systems-Approach/EMS_Education_Agenda.pdf.

Importantly, as we leverage the Practice Analysis to evolve prehospital medicine, it is critical to continue to assess both the source and quality of the data while applying new theories and best practices to current methodology. In this manuscript, we present the new template for the National Advanced Life Support (ALS) EMS Practice Analysis for the advanced emergency medical technician (AEMT) and paramedic levels of certification. This template combines established methodology with updated data sources, analysis strategy as well as expanded EMS professional and medical director engagement. Further, we describe the development of a hybrid-traditional model of job task analysis where lists of EMS tasks and associated knowledge, skills and abilities were generated based upon known clinical impressions in EMS practice. This approach will allow for a more detailed and robust evaluation of EMS care while focusing on each task conducted at each level of certification in EMS. The results of this study will be used to: inform the national core content, inform the educational standards process, design a new examination specification, and guide the development of content for the National Registry ALS examinations. A separate Practice Analysis will be conducted in the future for the Basic Life Support (BLS) programs following the template described.

Methods

A Practice Analysis was conducted for the ALS certification levels, AEMT and paramedic. The ALS Practice Analysis was conducted following guidelines from the National Commission for Certifying Agencies (Citation6) and the Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing (Citation2). The 2019 National ALS EMS Practice Analysis included three project phases: 1) defining the types and frequency of clinical presentations in prehospital care; 2) defining the criticality or potential for harm of these clinical presentations; and 3) defining the tasks and the associated knowledge, skills, and abilities that encompass prehospital care at the AEMT and paramedic levels. Each phase was approved by the American Institutes for Research Institutional Review Board.

Phase 1

Study Design and Population

Using the 2016 National Emergency Medical Services Information System (NEMSIS) Version 2 Public Release Research dataset (7, 8), Phase 1 involved a cross-sectional evaluation of a national convenience sample of EMS patient care records (Citation9). The NEMSIS dataset contains data elements that are uniformly collected to allow EMS stakeholders to evaluate EMS needs and performance. Included in the study were all EMS events with patient interactions and documented provider impressions. The clinical characteristics included for analysis were provider primary/secondary impressions, patient signs/symptoms, and procedures and medications provided by EMS. The 2016 NEMSIS Version 2 Public Release Research data dictionary has defined provider impression as the EMS professionals’ understanding of the patient’s primary problem or condition that led to the specific treatment decisions (e.g. procedures, medications). As such, patient signs/symptoms, procedures, and medications were analyzed by provider impression.

Measurements

Events that had a disposition where no patient interaction occurred (e.g., no patient found or cancelled) were excluded. Events that had both a primary and a secondary impression of a “not value” (not applicable, not recorded, not reporting, not known, or not available) were considered uninformative and, thus, also excluded. Events that had only a primary or a secondary impression of a “not value”, however, were retained. Inhalation injury (toxic gas) and smoke inhalation impressions were combined. Respiratory distress and respiratory arrest impressions were also combined due to encompassing similar domains. Events were classified into categories by impression, with an event being included in the respective category if the primary or secondary impression included that impression. After the exclusion of “not value” impressions, there were a total of 25 impressions that were considered informative.

Categorization of patient signs/symptoms, procedures, and medications was done in a similar manner. For example, events that had both a primary and other associated sign/symptom of bleeding were only counted once. Signs/symptoms with any of the “not values” as both the primary and other associated signs/symptoms were excluded. After the exclusion of “not value” signs/symptoms, there were a total of 21 signs/symptoms analyzed by impression. Procedures performed, with emphasis placed on procedures directly involving patients, were also analyzed. Procedures of a “not value” (e.g., not applicable or not recorded), activations (e.g., “Activation-Advanced Hazmat Specialty Service/Response Team”), assessments (e.g., “Assessment-Adult”), contact medical control, patient transportation (e.g., “Patient Loaded-Helicopter Hot-Load”), and rescue were excluded. In total, there were a total of 90 procedures of interest. The final element analyzed was medications administered during the event. Not applicable, unknown (e.g., “unknown IV gtt medication” or “unknown medication code”), and patient home medications were excluded due to incomplete information. Medications given were documented by EMS professionals with over 1,306 unique values (Citation7). These were cross-referenced to the medications identified in the National Model EMS Clinical Guidelines (Citation10) and grouped into 47 categories (e.g., brand, generic, and misspellings grouped).

Analysis

Indicator variables were generated for each of the 25 impressions of interest to capture if an event had either a primary or secondary impression. Indicator variables were generated similarly for each sign/symptom, procedure, and medication to denote events with each of these. Pediatric and adult sign/symptom, procedure, and medication indicator variables were tabulated for an overall view of the distribution of these respective areas across all impressions. After stratifying by impression, the same analysis of tabulating signs/symptoms, procedures, and medications was repeated. All analyses were conducted using STATA IC Version 16 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

Phase 2

Study Design and Population

In this phase, we conducted a cross-sectional survey with a sample of randomly selected, nationally certified EMS professionals and medical directors who were currently providing ALS prehospital care as identified in the National Registry EMS Certification database. We included EMS professionals working at the AEMT or paramedic certification level in the civilian prehospital setting or who were employed as medical directors of an EMS agency. We excluded those not currently working as an AEMT, paramedic, or medical director; those who had never worked as an EMS professional; or those affiliated with a military EMS agency.

Sample size calculations for simple random sampling were made to obtain estimates at the 95% confidence level, accounting for the finite population size and an acceptable 5% margin of error. Due to poor and declining response rates in the past (Citation11, Citation12), the sample was inflated assuming the response rate that would be achieved was conservative compared to the 2014 response rates (Citation5). We inflated AEMT and paramedic sampling by a conservative inflation factors of 10%. Concerning medical directors, a total of 10,884 medical directors were found in the National Registry database. Excluding duplicate email addresses, a total of 10,325 medical directors were sampled for the survey. We also expected that some medical directors may have their emails directed to the agency EMS educators/coordinators. Due to the uncertainty of the response rate from this group, the survey was sent to all medical directors. With a conservative 5% response rate, we estimated approximately 516 responses.

Survey Development

To gain an understanding of the study population, respondents were surveyed on personal demographics and EMS-related characteristics of their EMS position and agency. The survey used items from the previous practice analyses, large scale EMS demography studies (Citation13) and the NEMSIS impressions from the prehospital setting. The criticality for patient presentation was assessed using validated techniques (Citation14). Respondents were asked, “What is the potential for harm to the patient if you do not provide proper care?” using the following response categories: no harm, little harm, moderate harm, and high harm. Two sets of items regarding the same list of impressions as in Phase 1 were given for adult patients (≥18 years) and pediatric patients (0–17 years). The questions were presented in two categories of adults and pediatrics due to the difference in anatomy and physiology that lead to variations in the criticality. The surveys for AEMTs and paramedics were identical, but the survey items for medical directors reflected the demographics of the main agency or organization with which the medical director was affiliated.

Data collection was started by a pre-notification email, sent a week prior, informing the sample of EMS professionals that they would be receiving an electronic survey. The survey invitations were electronically sent to individuals in January 2019, and reminder e-mails were sent to those who had not responded at one and two weeks after the initial survey invitation (Citation15). The electronic questionnaire was conducted using the SurveyGizmo (Boulder, CO, USA) platform. Data were collected for two months. Each survey had a unique identifier linking the results to the respondent limiting individuals to one response. The survey responses were kept confidential, and individuals were only contacted if they had not yet participated.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated to describe the demographic characteristics of respondents, as well as the frequency and percentage in each harm category for each impression. Sex was dichotomized as male/female. The race and ethnicity survey items were similar to that used in the U.S. Census. Years of experience was organized into quartiles. Community size was dichotomized into urban (population ≥25,000) and rural (population <25,000). STATA IC version 16 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX) was used for statistical analysis.

Phase 3

Study Design

In Phase 3, teams of paramedic and AEMT subject matter expert (SME) panels were assembled to identify the tasks and KSAs associated with these levels of certification. In this work, a more traditional approach was followed where lists of tasks were generated based upon clinical impressions, followed by the identification of the KSAs associated with the tasks. This was labeled a hybrid-traditional approach because the tasks lists were created based upon the specific clinical impression under consideration by the panel rather than on major work behaviors or duties. The clinical impressions were generated following a secondary analysis of the NEMSIS dataset (Phase 1). Panels were conducted by industrial-occupational (I/O) psychology facilitators, using the previously identified clinical impressions (Phase 1) to formulate task lists and populate each task with the KSAs to perform each task. Two separate, independent panels, held one week apart, were assembled for the paramedic and AEMT levels. The initial tasks and KSAs were derived by the paramedic panel, while the AEMT SME panel analyzed the tasks and KSAs generated by the paramedic panel and indicated which applied to the AEMT level. These methods were developed in accordance with predetermined national standards for testing (Citation2).

Focus Group Identification and Training

All SMEs were selected with a focus on diversity in gender, age, region, and type of service and organization. Medical directors, State EMS directors and EMS educators were specifically included in panels for diversity of role representation. Panelists were nominated based on their national recognition and expertise at the paramedic or AEMT level of certification. Twelve SMEs participated in the paramedic panel, and eight SMEs participated in the AEMT panel (Appendix 1 and 2).

This step of the project was launched on April 15th, 2019 with release of an asynchronous training video for panel members to view before participation. Panels were held at the National Registry where, upon arrival, panelists were briefed on the overall project and received additional training on task list development process.

Focus Group Task Identification

Focus groups were lead and supervised by faculty from the University of Akron’s Center for Organizational Research. The five facilitators working with each individual focus group were graduate students in the industrial-organizational psychology program. Faculty and facilitators conducted the panel, collected the SME generated tasks and KSAs, and cleaned the collected data.

Panel members were divided into focus groups of three with a facilitator assigned to each group to review the group’s assigned impressions. Each paramedic panel was then asked to generate 10–20 tasks per impression, 2–20 KSAs per task, and reviewed and made final edits or changes to their specific task list. The procedure for the AEMT panel differed from the paramedic panel since the tasks and KSAs produced by the paramedic panel comprehensively captured the universe of tasks and KSAs found in the prehospital setting. The AEMT panel was then tasked to indicate whether each task must be performed by an AEMT; whether each KSA is required of an AEMT; to suggest any other revisions for paramedic or AEMT tasks/KSAs; and to review and make final edits or changes to the task list.

Clinical impressions were used as a starting point for the development of task lists and KSAs. All 25 impressions from Phase 1 were evaluated by SMEs with 8 additional areas evaluated including: pre-scene tasks, post-scene tasks, disaster and mass casualty incidents, written communication, affective communication, provider wellness, scene communications, and professionalism and ethics. These impressions were given to multiple focus groups (teams of three) for evaluation to ensure that the impressions were covered adequately.

Analysis

The raw data generated by the panels were inputted into Task-KSA matrices, cleaned and processed (Appendix 3). Task-KSA matrices were produced for each impression by the paramedic panel. Following the paramedic panel, the resulting Task-KSA matrices were cleaned, edited, and combined to have matrices ready for the AEMT panels. The matrices were then cleaned and edited again after the AEMT panels, resulting in 33 Task-KSA matrices.

Results

Phase 1

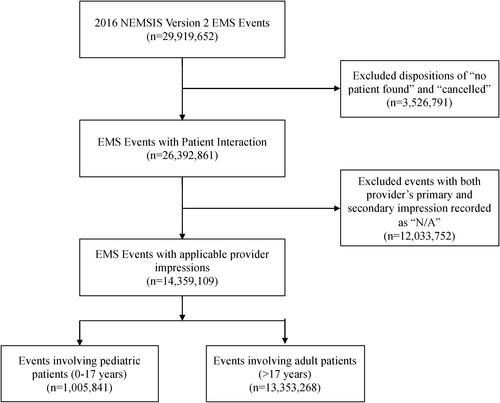

There were a total of 29,919,652 EMS activations during the study period. There were 14,359,109 events that had one of the 25 informative impressions of interest listed as either the provider’s primary or secondary impression and eligible for inclusion in the analysis. Because NEMSIS allows the data entry of both a primary and secondary impression for each event, there were a total of 15,825,075 impressions recorded across 14,359,109 events (). Eligible impressions were then separated into adult (≥18 years) and pediatric (0–17 years) events.

For adult impressions, there were 14,743,589 informative impressions across 13,353,268 events. The most common impressions were traumatic injury (18.8%), abdominal pain/problems (11.5%), respiratory distress/arrest (10.8%), behavioral/psychiatric disorder (10.6%), and syncope/fainting (9.1%) (). For all the adult impressions, the most common signs/symptoms were pain (25.1%), change in responsiveness (12.7%), breathing problem (10.0%), weakness (9.0%), and none (8.0%). Across all adult impressions, the most commonly performed procedures were venous access-extremity (33.2%), cardiac monitor (20.9%), pulse oximetry (19.2%), 12 lead ECG obtained or transmitted (17.6%), and blood glucose analysis (14.2%). The most commonly administered medications were oxygen (14.5%), normal saline (9.6%), aspirin (4.0%), nitroglycerin (3.3%), and ondansetron (3.0%). An example of these results for the adult impression of trauma is shown in .

Table 1. Overall provider primary or secondary impressions by number of adult impressions

There were 1,081,486 informative pediatric impressions across 1,005,841 pediatric events (7% of total events). The most prevalent pediatric impressions were traumatic injury (28.1%), behavioral/psychiatric disorder (15.3%), respiratory distress/arrest (13.1%), seizure (11.0%), and abdominal pain/problems (7.7%) (). Pain (19.5%) was the most common sign/symptom across all pediatric impressions, followed by change in responsiveness (12.7%), breathing problem (11.1%), mental/psych (10.2%), and none (9.7%). Across all pediatric impressions, the most commonly performed procedures were venous access-extremity (14.2%), cardiac monitor (13.2%), pulse oximetry (13.2%), blood glucose analysis (7.2%), and pain measurement (4.6%). The most commonly administered medications across all pediatric impressions were oxygen (6.9%) normal saline (4.6%), albuterol (2.0%), fentanyl (1.6%), and ondansetron (1.4%).

Table 2. Overall provider primary or secondary impressions by number of pediatric impressions

Table 3. Demographics of the study population (overall and by level of practice) for the phase 2 survey

Phase 2

There was a total of 4,080 responses for the 25,075 surveys that were deployed in January 2019 (total response rate = 16.3%) (Appendix 5). A total of 1,553 responses were received from AEMTs (response rate = 20.9%), 1,499/7,758 responses from paramedics (response rate = 19.3%), and 1,028/9,876 responses from medical directors (response rate = 10.4%). A total of 3,318 responses met the inclusion criteria and were included in the analysis. Most respondents were non-Hispanic white and male with a variety of years of experience between AEMTs, paramedics, and medical directors (Table3). Many respondents were working for fire departments or private companies, providing primarily 9-1-1 services at their main job, and working in urban settings; less than 10% of EMS professionals were working in a mobile integrated health capacity.

Impressions with the potential for the highest harm to the patient were those associated with high mortality rates and severity of patient presentation (). Adult patients who presented with an airway obstruction, respiratory distress/arrest, cardiac arrest, hypovolemia/shock, allergic reaction, or stroke/CVA were rated as having a potential for high harm (>80%). Adult patients who presented with abdominal pain/problems or behavioral/psychiatric disorder were rated as having a potential for low harm (18.1% and 22.3%, respectfully). Obvious death was ranked as having the potential for the lowest harm (68.1%) to the adult patient.

Table 4. The potential harm to an adult and pediatric patient if proper care is not provided in the prehospital setting for EMS impressions rated with the highest possibility of harm (high harm >80% per respondents)

Similar to adult categories, impressions with the potential for the highest harm to the pediatric patients were associated with high mortality rates with some variation between the two age categories (). Pediatric patients who presented with an airway obstruction, respiratory distress/arrest, cardiac arrest, hypovolemia/shock, allergic reaction, stroke/CVA, and inhalation injury were rated as having a potential for high harm (>80%).

Phase 3

Task-KSA matrices were produced for each impression by the paramedic panel. An example a completed Task/KSA Matrix for the Domain of Cardiology & Resuscitation, subdomain of Focused Assessment and Pathophysiologyis shown in . After cleaning the tasks and KSAs and combining duplicate entries, there were a total of 425 tasks and 1,734 KSAs for the paramedic program. The subsequent AEMT panel identified that a total of 405 tasks and 1,636 KSAs from the paramedic task and KSA lists applied to the AEMT level.

Table 5. Complete task/KSA matrix for the domain of cardiology & resuscitation, subdomain of focused assessment and pathophysiology

Discussion

The 2019 ALS Practice Analysis defines the methodology to be used in future evaluations of the care provided in the prehospital setting. In this iteration of the Practice Analysis, we were able to define the work performed in the prehospital setting using psychometrically sound methodology along with new data sources, thus improving the precision of our estimates. This also allowed for a nuanced analysis of prehospital care which was not possible in the past (Citation5). However, as noted previously, the goal of this analysis was not limited to defining a vision of current care. These data can be leveraged to inform the scope of practice, educational standards, and assist in validating the ALS levels of the certification examination. Content from this Practice Analysis has been used in the development of the EMS Educational Standards, National Registry examination specifications, and will be disseminated for the next scope of practice process by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration’s Office of EMS.

Since the last Practice Analysis, much of what we have learned about prehospital care still holds true; however, several findings were new and challenging. The majority of prehospital events involved adult patients, with a small fraction involving pediatric patients. This is consistent with recent data on prehospital pediatric events with estimates of 7% (Citation16, Citation17). The most common impressions noted for adults have not changed dramatically with traumatic injury, abdominal pain, and respiratory distress/arrest leading the list (Citation18). However, we also noted an increase in events associated with behavioral/psychiatric disorders, higher than previous estimates (Citation18). This was also true in pediatric events where behavioral/psychiatric emergencies were second behind traumatic injury. The large contribution of behavioral emergencies seen here mirrors what has been reported in ambulatory pediatric populations and supports the concept of an increased number of mental health complaints in pediatrics (Citation16, Citation19, Citation20). These results demonstrate the critical role that the Practice Analysis plays in tracking trends in EMS care such that education content, training, and assessment can all accurately reflect real world practice.

Additional updates with the current Practice Analysis methodology include the use of the NEMSIS dataset to define frequency of impressions. Previous practice analyses used survey methodology for the assessment of frequency and criticality of clinical impressions, similar to other specialties (Citation21–23). In the current analysis, the methodology was updated to mirror that used by the American Board of Emergency Medicine, which leverages emergency department data from the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey to evaluate frequency of visits, conditions, and diagnoses (Citation24). The use of the 2016 NEMSIS dataset included data from most of the EMS activations for 46 of 50 states and territories, making it an ideal sources data to evaluate prehospital care. This removed the confounding effects of recollection bias of the previous methods and allowed for the analysis of procedures, medications, and signs and symptoms. This approach allowed for a more detailed understanding of prehospital clinical impressions, thereby improving their transition into educational content and assessments.

One exciting innovation in this Practice Analysis is the derivation of all the tasks performed by prehospital providers along with their associated KSAs. The paramedic task list defines the full scope of behaviors performed in the prehospital setting. All other certification levels, which are encompassed by the paramedic scope, will have smaller numbers of tasks and KSAs. Interestingly, we noted only a small margin between paramedics and AEMTs, with a limited number of tasks differentiating the two. It appears that for many of these tasks, the difference between levels may be due to depth of knowledge rather than whether a specific task was within scope. This will require further evaluation to better understand how this concept can be integrated in the clinical model for prehospital care (Citation25). Finally, SME’s noted that many identified tasks were thought to be encompassed at the EMT level in the basic performance of a patient assessment and physical exam. This concept will also require further evaluation in a future Practice Analysis for the EMT and EMR levels.

As with any evaluation, there are several limitations and expected challenges in the current evaluation. First, in Phase 1, with the use of NEMSIS, there is a possibility of misclassification as well as variations in documentation between agencies and states. We also excluded NEMSIS defined procedures such as assessments, contact medical direction, or patient transportation due to inconsistent patterns of documentation. Additionally, in the dataset (as noted in ), 12 million records have “N/A” as the providers primary and secondary impression and therefore were excluded. Further, we used version 2 of the dataset compared to the updated version 3 since at the time of the analysis agencies were in the process of transitioning to version 3. Sampling EMS professionals for Phase 2 was also challenging. To compensate for historically low response rates for electronic surveys in EMS (Citation11, Citation12), we conducted a sample size calculation with inflation of the sample. We still obtained an overall response rate of 16%. However, as noted in the appendices, the survey respondents were similar in characteristics to a nationally registered population (Citation13). In Phase 3, using a SME group, we accept that we are unable to make a representative stakeholder group which matches the EMS population. Our intention was to have expertise in defining and understanding overall EMS tasks and the associated KSAs, while selecting as diverse a group of experts as possible. Another challenge we identified was the large number of tasks derived by our experts since it was difficult to identify which tasks are specifically associated with a certain level. In this manuscript we included all the tasks and KSA, however, as we move to the BLS Practice Analysis, effort will need to be placed to identify tasks which encompass specifically the EMT and EMR levels so that the gap between the certification levels is more transparent.

Conclusion

The 2019 ALS Practice Analysis describes prehospital practice at the AEMT and paramedic levels. This approach allows for a detailed and robust evaluation of EMS care while focusing on each task conducted at each level of certification in EMS. The data can be leveraged to inform the scope of practice, educational standards, and assist in validating the ALS levels of the certification examination.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (45.8 KB)References

- Kane M. Model-based practice analysis and test specifications. Appl Meas Educ. 1997;10(1):5–18. doi:https://doi.org/10.1207/s15324818ame1001_1.

- American Educational Research Association, American Psychology Association, National Council on Measurement in Education. Standards for educational and psychological testing. Washington (DC): American Educational Research Association; 2014.

- Wang N. Examining reliability and validity of job analysis survey data. J Appl Meas. 2003;4(4):358–69.

- Raymond MR. Job analysis, pratice analysis and the content of credentialing examinations. In: S Lane, MR Raymond, T Haladyna, editors. Handbook of test development. 2nd ed. New York (NY): Routledge; 2016. p. 144–64.

- National Registry of Emergency Medical Technicians. 2014 National EMS practice analysis [Internet]. Columbus, OH; 2015. [cited 2020 Dec 9]. https://zurl.co/810x.

- National Commission for Certifying Agencies. Standards for the accreditation of certification programs. [Internet]. 2014. http://www.credentialingexcellence.org/p/pr/vi/prodid=169.

- National EMS Information System. V2 dataset dictionaries—NEMSIS [Internet]. 2020. https://nemsis.org/technical-resources/version-2/version-2-dataset-dictionaries/.

- National EMS Information System. V2 public EMS strong dashboard [Internet]. 2020. [cited 2020 Sep 15]. https://nemsis.org/view-reports/public-reports/version-2-public-dashboards/v2-ems-strong-dashboard/.

- Mann NC, Kane L, Dai M, Jacobson K. Description of the 2012 NEMSIS public-release research dataset. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2015;19(2):232–40. doi:https://doi.org/10.3109/10903127.2014.959219.

- National Association of State EMS Officials. National model EMS clinical guidelines [Internet]. Washington, DC; 2017. https://www.ems.gov/pdf/advancing-ems-systems/Provider-Resources/National-Model-EMS-Clinical-Guidelines-September-2017.pdf.

- Cash RE, White-Mills K, Crowe RP, Rivard MK, Panchal AR. Workplace incivility among nationally certified EMS professionals and associations with workforce-reducing factors and organizational culture. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2019;23(3):346–55. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10903127.2018.1502383.

- Cash RE, Crowe RP, Rodriguez SA, Panchal AR. Disparities in feedback provision to emergency medical services professionals. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2017;21(6):773–81. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10903127.2017.1328547.

- Rivard MK, Cash RE, Mercer CB, Chrzan K, Panchal AR. Demography of the National Emergency Medical Services Workforce: a description of those providing patient care in the prehospital setting. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2020;24:1–8.

- Spray JA, Huang CY. Obtaining test blueprint weights from job analysis surveys. J Educ Meas. 2000;37(3):187–201. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-3984.2000.tb01082.x.

- Dillman DA, Smyth JD, Christian LM. Internet, phone, mail and mixed-mode survey: the tailored design survey. Indianapolis, IN: John Wiley and Sons Ltd; 2014.

- Diggs LA, Sheth-Chandra M, De Leo G. Epidemiology of pediatric prehospital basic life support care in the United States. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2016;20(2):230–8. doi:https://doi.org/10.3109/10903127.2015.1076099.

- Shah MN, Cushman JT, Davis CO, Bazarian JJ, Auinger P, Friedman B. The epidemiology of emergency medical services use by children: an analysis of the national hospital ambulatory medical care survey. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2008;12(3):269–76. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10903120802100167.

- Duong HV, Herrera LN, Moore JX, Donnelly J, Jacobson KE, Carlson JN, Mann CN, Wang HE. National characteristics of emergency medical services responses for older adults in the United States. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2018;22(1):7–14. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10903127.2017.1347223.

- Yuknis ML, Weinstein E, Maxey H, Price L, Vaughn SX, Arkins T, Benneyworth BD. Frequency of pediatric emergencies in ambulatory practices. Pediatrics. 2018;142(2):e20173082. doi:https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-3082.

- Chun TH, Mace SE, Katz ER, Shook JE, Callahan JM, Conners GP, Conway EE, Dudley NC, Gross TK, Lane NE, et al. Executive summary: evaluation and management of children and adolescents with acute mental health or behavioral problems. Part I: common clinical challenges of patients with mental health and/or behavioral emergencies. Pediatrics. 2016;138(3):e20161571. doi:https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-1571.

- National Council of State Board of Nursing. Report of findings from the 2017 RN nursing knowledge survey [Internet]. 2018. https://www.ncsbn.org/12254.htm.

- National Council of State Board of Nursing. Report of findings from the 2018 LPN/VN nursing knowledge survey (Vol. 76) [Internet]. 2019. https://www.ncsbn.org/13519.htm.

- Tyler DO, Hoyt KS, Evans DD, Schumann L, Ramirez E, Wilbeck J, Agan D. Emergency nurse practitioner practice analysis: report and implications of the findings. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2018;30(10):560–9. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/JXX.0000000000000118.

- Hockberger RS, La Duca A, Orr NA, Reinhart MA, Sklar DP. Creating the model of a clinical practice: the case of emergency medicine. Acad Emerg Med. 2003;10(2):161–8. doi:https://doi.org/10.1197/aemj.10.2.161.

- Freel J. EMS education agenda for the future: a systems approach [Internet]. Prehospital Emergency Care. 2000. https://www.ems.gov/pdf/education/EMS-Education-for-the-Future-A-Systems-Approach/EMS_Education_Agenda.pdf.