Abstract

Objective: Paramedicine in Canada has experienced significant growth in recent years, which has resulted in a misalignment between existing guiding conceptualizations and how the profession is structured and enacted in practice. As a result, well-established boundaries, directions, and priorities may be poorly aligned with existing frameworks. The objective of this study was to explore emerging and future states of paramedicine in Canada such that guiding principles could be derived. We asked: How should paramedicine be conceptualized and enacted in Canada going forward, and, what might be the necessary enablers? Methods: This study involved in-depth one-on-one semi-structured interviews with Canadian paramedicine thought leaders. We used purposive and snowball sampling strategies to identify potential participants. Interview guide questions were used to stimulate discussion about the future of paramedicine in Canada and suggestions for implementation. We used inductive qualitative content analysis as our analytical approach, informed by a constructivist and interpretivist orientation. Results: Thirty-five key informants from across Canada participated in interviews. Ten themes were identified: (1) prioritizing patients and their communities; (2) providing health care along a health and social continuum; (3) practicing within an integrated health care framework, and partnering across sectors; (4) being socially responsive; (5) enacting professional autonomy; (6) integrating the health of professionals; (7) using quality-based frameworks; (8) enacting intelligent access to and distribution of services; (9) enacting a continuous learning environment; and, (10) being evidence-informed in practice and systems. Six enablers were also identified: shift professional culture and identity, enhance knowledge, promote shared understanding of paramedicine, integrate data environments, leverage advancing technology, advance policy, regulation and legislation. Conclusions: Our results provide a conceptual framework made up of guiding principles and enablers that provide a consolidated lens to advance the paramedicine profession in Canada (and elsewhere as appropriate) while ensuring contextual and regional needs and differences can be accounted for.

Introduction

Paramedicine in Canada has experienced significant changes in recent years, and this has resulted in a misalignment between existing conceptualizations of the profession and emerging practice (Citation1). For instance, in contrast to more “traditional” responsibilities (e.g., responding to emergencies and providing transport to emergency departments), paramedics have played a role in delivering primary care in under-serviced rural areas, have been integrated into long-term care settings, and support palliative and family health teams (Citation1–4). Increasingly, paramedicine is becoming recognized as a profession whose unique point of contact with broad patient groups can be leveraged to better serve health care needs and meet new policy goals (Citation5, Citation6)

What paramedicine is, how it should be organized, and what newer roles and conceptualizations mean, are challenging well-established boundaries and guiding frameworks are lacking (Citation7–9). The most recent Canadian national framework was produced in 2006 by the Emergency Medical Services Chiefs of Canada (now Paramedic Chiefs of Canada [PCC]), which included six strategic directions: injury and prevention; emergency medical response; community health; training and research; public education; and emergency preparedness (Citation9). Despite this framework, some have cautioned that aspects of paramedicine (e.g., community paramedicine) continue to suffer from lack of coordination and that without it, there is risk of paramedicine becoming “piece-meal patches to a system in crisis” (Citation5). Since 2006, a number of advances that are not clearly captured in these pillars have emerged, such as more focused frameworks for community paramedicine (Citation5), different roles paramedics are to embody in their work (Citation10), research targets (Citation11), issues related to physical demands (Citation12), dimensions of practice (Citation13), the need for case management (Citation14), assessment of competence frameworks (Citation15), insights related to mental health (Citation16) and safety threats (Citation17, Citation18). Given how a rapidly shifting health care system is changing how professions are organizing and evolving (Citation19, Citation20), the variable clinical practice structures, broadening public and health care system use of paramedicine, and diverse views among stakeholders about what paramedicine is or should be, calls for a better understanding of the current and future state of paramedicine.

In the absence of a guiding framework, the objective of this study was to explore emerging and future states of paramedicine in Canada such that a framework could be derived. Specifically, we asked: how should paramedicine be conceptualized and enacted in Canada going forward and what might be necessary to achieve it? The aim of our study was to offer principles and enabling factors that could promote a national direction, discussion, and further study for paramedicine in Canada and internationally where possible.

Methods

Overview Study Design

This study involved semi-structured interviews with thought leaders within the Canadian paramedicine context. We used a peer-nomination process to identify informants, and used role types in paramedicine and geography to further inform our sampling. We analyzed our interviews using qualitative content analysis, while adopting an inductive, constructivist, and interpretivist orientation (Citation21, Citation22). This work was commissioned and funded by the PCC but conducted independently. Ethical approval was provided by the University of Toronto.

Context

Within Canada, paramedicine is organized as either public or private providers that are provincially or municipally operated. Paramedicine is self-regulated in some, but not all, provinces. Paramedicine generally includes the provision of health care services in a public safety model, offering mostly out-of-hospital emergency services with an emphasis on resuscitation and transportation. Numerous alternative models of care are locally derived in terms of scope, policy, oversight, education, and quality assurance. There is a relatively consistent classification of paramedics across Canada, but scopes of practice vary within these classifications. There is a national competency profile that at the time of this study was in transition and not universally used or accepted (Citation23). Educational models are variable in length of program, content, credential awarded and accreditation status. Entry to practice and maintenance of certification expectations are also variable. Finally, clinical oversight models include both physician-led and collaborative paramedic-physician models. Given this diversity, this study used the term “paramedicine” broadly and included individuals shaping and providing services, the organizations within which they work, and the institutions that guide, regulate, or govern conduct.

Sampling Strategy and Key Informants

We used purposive and snowball sampling strategies to identify thought leaders in paramedicine to serve as key informants (Citation24). We began by using existing national and provincial networks to distribute a call for nominations for those who were considered well suited to speak on behalf of or about paramedicine in Canada. We accepted nominations between June and November, 2019 and prioritized our invitations according to frequency of nominations. We then used stakeholder groups, and geography to reach under-represented groups and promote diversity of views. Our sampling aims were to consider a relevant and diverse range of contexts and ideas rather than a strictly representative sample (Citation24).

Data Collection: Semi-Structured Interviews

An interview guide was structured to explore the state of paramedicine today, shifts that may be necessary, existing and future problems paramedicine might be a solution for, changes to structure and conceptualization, and future priorities. The draft guide was piloted to ensure clarity, the fostering of open dialogue, and to ensure leading questions were avoided. The guide evolved over time as necessary to explore emerging concepts.or tensions, discuss gaps, etc.

We used semi-structured, in-depth interviews as our primary source of data collection (Citation24). All interviews were conducted one-on-one by telephone by the primary investigator. Interviews were scheduled for 60 minutes but allowed to end naturally. Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim, and reviewed for accuracy prior to analysis. All memos taken during the interviews were included as data. We continued data collection until we had reached saturation and representativeness (Citation24).

Analysis

An inductive qualitative content analysis was conducted (Citation21). This included a process of deriving codes, abstractions, and preliminary groupings or themes based on extensive memos taken during and after each interview, and initial reading and open coding of the transcripts; organizing and grouping coding while looking for similarities, differences and redundancies by three members of the research team (WT, LB, AA); and frequent team meetings to discuss the guide and findings. Qualitative rigor was achieved through ensuring quality and accuracy of the data, prolonged engagement, constant comparison, and peer debriefing among the research team. We were diligent in searching for deviant cases in the data set, looking for meaningful variation that might have productively disrupted our analysis. QSR NVivo (http://www.qsrinternational.com/) was used to store, manage, and organize the data.

Results

There were 205 nominations received from 63 nominators across most of the country’s provinces and territories, resulting in a pool of 168 potential informants. Some informants were nominated more than once. Using the criteria and prioritization outlined above, a total of 47 invitations were sent. After 35 interviews, conducted between July, 2019 and December, 2020, recruitment was closed as saturation of ideas and representativeness was considered to have been achieved. Most of our sample identified as male (n = 25; 71%). Participants represented all 10 provinces and one of three territories, 18 stakeholder organizations, 10 stakeholder roles, and eight clinical roles (see ).

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of key-informants (n = 35)

We identified 10 themes and six cross-cutting enabling factors.When providing supportive quotes, we identify only the province from which the participant was situated to ensure confidentiality.

Prioritizing Patients & Their Communities

Participants described that the patient and their community is at the core of the profession. This meant understanding the interconnected relationship that patients have within their communities, and their needs. This includes appreciating emerging population health trends and the unique cultural and social community characteristics that subsequently shape and influence care delivery and system design. The health of a community was recognized as intrinsically connected to the wellbeing of individuals. As one participant noted:

We don’t think about the demographic of patients or population that’s going to live in that community from an EMS perspective…let’s get out of the traditional response technique and let’s start thinking about our community as a whole that we actually are integrated with rather than driving and responding to. (AB)

Shifting to a patient and community-centered approach was identified as a key driver and opportunity to enhance and adopt a holistic approach to care. For example, moving from technical and emergency/event-based responses to whole person, relationship-based care that embraced medical care alongside empathy, comfort, social health, and quality of life:

… it’s not just about giving somebody some analgesia. It’s about taking care of their other needs and being good communicators and making people feel comfortable and being empathetic. … we’re not trained to do that traditionally so it’s about moving into that more holistic care because that is something that we can and should be doing (BC)

Intentional patient and community engagement in evaluation, system redesign, and research initiatives was strongly recommended. Participants described a slow uptake to engage patients and their communities into the profession’s decision making and evaluation of services.

Providing Health Care along a Health and Social Continuum

Changing health care needs and increasing social needs of patients in their communities were described as key drivers. Shifting from a traditional emergency response model toward a health care model inclusive of preventative, supportive, urgent response, and community-based primary and chronic care was a vision that most participants agreed on. They talked about how paramedicine should be conceptualized as “an intersection between health and social care”(ON), obligating paramedicine of the future to include the necessary infrastructure and knowledge/skills:

…we also are sending them to some of the most complex, vulnerable patients…and, there’s a big gap between what they can provide or what they know they can provide at those scenes and then actually what we as a system, as an organization, have the capacity to do for those patients. Frequently, we’ll still visit patients nine or ten times before somebody realizes that their needs are more social or more complex and we have neglected to provide those at the first or second visit…I hope, in the future…that every frontline paramedic has the knowledge about primary health and paramedic’s role in the health care system will be that every interaction that we have with the patient, no matter when it started or why it started, is fulfilled with those abilities to care for them in a more rounded way. (MB)

Participants were signaling the importance of shifting from a traditional emergency and medical response model to one that is inclusive of complexity and holistic notions of community-based primary and chronic care, and that this become part of the profession’s core business. The roles of social determinants of health and social services were viewed by participants as significant foci in patient interactions, future service planning, and paramedic education and research.

Practicing within an Integrated Health Care Framework and Partnering across Sectors

Participants agreed that the changing role of paramedicine is most appropriately suited within health care, though some disagreed as to what extent the profession should let go of its public safety roots and identity. Many described the need to better integrate and collaborate with other health and social services across a range of sectors – health care, government, private industry, education, and research-based institutions – but with limited agreement on organizational models for achieving this:

If someone calls for help and we’re definitively managing that care, some people need to go to hospital, some people might need to go to clinic, some people might be able to stay in their home and be managed in some other manner. To me, that’s all of our core business. I think we’ve been very successful, at least, sort of [in] changing the philosophical view of the health authority, that the core business of EMS is no longer you call, we haul, it’s not just the 9-1-1 business, but we’re also there to support other aspects of the health care system (MB)

Some recommended that the profession reconsider and develop an agreed-upon and cohesive professional identity that is anchored in an integrated health care framework that can be understood relative to other professions, and better allow for role delineation and collaboration in a variety of contexts.

Being Socially Responsive

Participants discussed the need to be more attentive to societal issues, in the overall structure of the profession (e.g., education, staffing, professional and operational activities, etc.), in the way care is provided, and by leveraging the profession’s role in the community. This included the professional’s/profession’s obligation to contribute to their community in a way that makes the quality of life for the community and social environment better. We also heard about the profession’s inadequacy in attending to its own internal issues of diversity and gender inequality:

I would definitely see a greater emphasis on having the profession look like the patients they treat, so, greater indigenous representation, greater international representation in the profession. Right now, it’s extremely low on both fronts…it’s important that we have professionals that look like our patients and that understand the cultural nuances. (SK)

Being socially responsive meant better attending to systemic injustices such as indigenous rights, gender and race inequalities, as well as local issues within the context of the communities the profession serves.

Enacting Professional Autonomy

If you have someone who is always telling you what it is that you need to do, then when does the profession direct itself? (NS)

This quote illustrates participants’ consensus for professional autonomy. Paramedicine was described as a maturing profession that is ready and has the capacity for self-determination, and profession-directed advancement under its own governance, regulation, evidence generation, and improvement processes. Professional autonomy was described as “an enabler to paramedics being able to fulfill their professional role and contributions: …” (MB). Seeking professional autonomy was in part due to views that advancement has been held back when decision-making and practice oversight is conducted by others. A reframing of the relationship with physicians was often highlighted:

I see paramedicine as part of a health care team, an equal health care partner, for its knowledge, environment and specializations…there will always be a need for physicians as part of the team, but I would like to see them more consultative versus permissive…an advisor as opposed to an overseer. (ON)

Participants commented on the value of collaborations with physicians, as well as the challenges doing so has on moving toward professional autonomy.

Prioritizing the Health of Professionals

Participants expressed a deep concern for how the health and wellness of people who work within paramedicine is being addressed. Wellness or health was defined broadly, and included integrated physical, psychological, and social issues. Numerous threatening factors were identified, including: degree of safety and inclusiveness in the workplace, effect of newer roles, outdated organizational structures and decision making pathways, poorly aligned psychological supports, the effect of shift-work, and limited career advancement and fulfillment.

I think that we haven’t even touched the surface on some of the staffing issues that are out there in the psychological health and safety environment and in the violence towards paramedics, in the respectful workplace behaviours. There’s that whole employee wellness and safety piece. (AB)

The importance of workplace environments and culture in fostering wellness were discussed, particularly in regards to the role leadership plays in driving a culture that is inclusive and safe for everyone. Discrimination and harassment in the workplace was identified as contributing to psychological stress, and that addressing equity and diversity in the workplace, particularly with regard to gender in leadership, is overdue.

Participants acknowledged that the profession has done well to bring awareness to issues around the psychological effects of paramedicine, such as exposure to potentially traumatic events, and that this is creating legislative change, more research, and greater diversity of proposed solutions. This work needs to continue, with self-help, health and well-being woven into the ethos of the profession.

Using Quality-Based Frameworks

Participants expressed that paramedicine has been tethered to outdated, non-evidence-based, or poorly aligned ways of thinking about and measuring quality and performance. Response times, for example, was brought up repeatedly as overemphasized and an insufficient indicator of quality:

We’ve got to get away from the response time modelling and we’ve got to get away from call volume measurements as the sign of the performance of a system. There is so much evidence that in the vast majority of EMS responses, response time makes little to no difference. Yet, we continue to use an eight-minute yardstick, that is really based on no science (BC).

Many described the need for a conceptual shift in terms of what matters, to whom and why. Some wanted to see an increased emphasis on “…the measuring of clinical performance and the strategies to improve clinical performance” (AB) while others said “Quality is more than just clinical patient care, it’s definitely about the patient experience and it’s also about cost and efficiency” (MB). Participants highlighted the difficulty with existing quality models in detecting meaningful change. This was discussed in terms of the structural, cultural, or organizational shifts that would be necessary, such as a greater investment in technology, improved access to and analysis of data, overcoming risk aversion, involving patients in setting indicators, and improved reporting structures that are transparent, comparable, and consistent:

I think the greater transparency to the public in any performance metrics that you might design or implement or that have external validity to other provinces as well. (BC).

Overall, there was a call for a renewed culture of performance and quality measurement that better reflects the priorities of the profession, the public, and health care broadly.

Enacting Intelligent Access to, and Distribution of, Services

Participants provided insight into new ways that paramedic services can be effectively and equitably accessed, distributed, and informed by patient preference and needs. Inefficiencies in the ways in which paramedic expertise has been used and the limitations of existing dispatch systems were identified as significant concerns:

The balance for me is I believe the 9-1-1 system, in and of itself, was set-up for emergencies so it’s that balance between does 9-1-1 become an access point for all health care concerns, emergent or non-emergent? (AB).

Participants suggested systems and strategies that meet the needs of the public, patients, and communities while accounting for localized health care system contexts and resources were required. This meant some restructuring and better alignment between demand and the services paramedicine would offer in the future. Several strategies were identified including alternative access pathways, enhanced scopes of practice, caller triage, primary and secondary triage systems, technologies to identify/predict emergency responses and to manage logistics of resource distribution, and directing patients to non-emergency services, and other alternatives to ambulance transport:

We should stop transporting patients for the sake of transporting patients. We should stop taking patients to the ED because they don’t have other means to see a clinician or because they think that getting by ambulance to the ED will make them skip the line. I think that from the quality perspective, we call that waste. We should get rid of that. That’s not adding value to our service, and certainly not to the system. (BC)

Fostering a Continuous Learning Environment

Participants described the need for an enhanced organizational learning culture that supports both individual and system growth. This also meant ensuring that the supporting structures necessary to promote greater responsiveness to health care system needs and improving the profession’s performance on an ongoing basis are in place. This cultural growth orientation was framed in several ways, including philosophical shifts, risk and experimentation aversion, critical review of existing practices, improving opportunities, and how data (as an example) are used in the system:

EMS agencies don’t view their data over time…they’re making all these strategic decisions about things that perhaps they’re not getting the right information, because they’re not [using] their data…we could spend some money on getting some people to support us that know a lot about data, so we could make better decisions. I don’t think all of our EMS leadership is equipped to do that. (MB)

Participants discussed continuous learning as a mechanism for achieving credibility with health care peers, better clinical and system performance, better data utilization, and fulsome integration of advanced technologies. The discussions represented a shift toward better and ongoing readiness and developmental state.

Being Evidence-Informed in Practice and Systems

Transforming paramedic practice, systems, behaviors, and many of the features described above were linked to the profession’s capacity to generate and use knowledge, data, and evidence. Developing a paramedic-led body of knowledge, in addition to drawing from literature, was identified by participants as key to the profession’s practice, growth, credibility, and autonomy, describing research “as the foundation for the way things go forward” (ON). Recognizing existing limitations within the profession to generate research, leaders shared experiences of having to reach outside of the profession for support:

So busy doing, not many of us have been focused on publishing. Because of the capacity of data we do have a contract with a health research group affiliated with the university contracted to provide research capacity, and they are doing our evaluations. (PEI)

Participants noted ways of being better at having an evidence informed system. These included: better access to and sharing of data, overcoming knowledge/capacity gaps, and ensuring an infrastructure that supports research. Others discussed a future state that was reflective of an organizational commitment and culture that views research as fundamental, integrated, embedded, and core business.

Creating a National Vision for Paramedicine: Enabling Factors

Participants provided several insights into elements that were identified as necessary activities toward promoting achievement of several themes. Six enabling factors were identified and are included in .

Table 2. Six cross cutting features that were described as enabling factors to achieve principles guiding the future of paramedicine in Canada, with their descriptions

Discussion

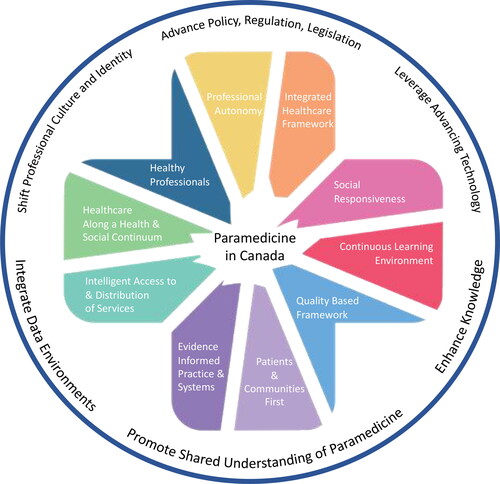

In this study, we identified 10 themes and six enabling factors that provide a consolidated conceptual framework to guide and evaluate emerging and future states of paramedicine in Canada. Using these findings, we propose a consolidated list of principles and definitions in , with both principles and enabling factors represented in . These principles and enabling factors provide an opportunity to flexibly shape paramedicine across a diversity of communities by serving as a stimulus for a productive bringing together of existing and future activities for shared progress.

Figure 1. The future of paramedicine in Canada: Proposed guiding principles and their enabling factors. The figure represents the emphasis on health care, and the equal but unique individual contributions of each principle, coming together to inform what paramedicine is in Canada. Enabling factors supporting the principles are represented in the outer ring and are not aligned with any particular principle or group of principles.

Table 3. Proposed principles derived from identified themes and definitions to guide the future of paramedicine in Canada

The principles and enablers identified represent an evolution in paramedicine in Canada, (and possibly in other settings), but are also consistent with some earlier visions. For instance, earlier visioning reports introduced similar transitions to primary-care-like concepts, integrated care, and emphasis on research (Citation9). When viewed as principles and considered against historical and other more contemporary Canadian national (Citation9, Citation10, Citation23, Citation24), and international frameworks (Citation25, Citation26), they present new opportunities and areas of focus. These can be organized in three broad ways. First is a calling for the profession to be more accountable to and for itself. This includes prioritizing the wellness of professionals, the ability to generate and use evidence deemed relevant by the profession, and having the capacity to detect and act on areas in need of change in all facets of the profession. Second is a greater accountability to the public and communities served. The public must have greater involvement in shaping and structuring access to services, informing performance and quality indicators, and ensuring social and health inequities/injustices are not ignored. Third is accountability related to better aligned services as solutions to health care challenges. An example might be positioning paramedicine as a team concept by minimizing discontinuities in care, ensuring services are accessible in better ways, and by organizing health and social services rather than focusing mainly on transportation, biomedical, or emergent needs.

As an evolution for paramedicine, and in these three ways in particular, principles are a suitable structure. They provide the opportunity to consolidate efforts and generate expected behavior and shape decision making, without being overly prescriptive. While holding principles constant, actors can flexibly study and enact them in unique and context-specific ways, and yet connect those activities for shared progress.

The complexity and magnitude of the promise associated with these principles calls for vigorous leadership from numerous sectors but also careful examination These principles may be difficult to enact (especially nationally) without leadership from governments, policy makers, regulators, accreditors, community leaders, patient groups, service operators, and educators to name a few. Scholar-led initiatives with capacity and funding will need to assist the profession in knowledge production and curation. Much of what is included in these principles will require additional investment, will need to be developed further over time through experience, and will require shared data, cross-jurisdictional talk, and implementation of the enabling factors. Careful consideration should be given to what we did not hear in the interviews, where tensions remain (e.g., whether to deemphasize or abandon deeply rooted resuscitation and transport identity, to adopt generalist or specialist models), and toward a better understanding of potential barriers. These principles and enablers are proffered as a starting point for discussion and offer flexibility for local implementation and interpretation. Provisions must be made for frequent evaluation, and additional study to support principle development, correction, or refinement. While some of these needs are reflected within the enabling factors, additional information or strategies may be necessary. At this vital point the challenges are great, but so too are the opportunities.

Limitations

Our sample was weighted heavily on leaders within the system, thereby minimizing the voices of other key informants such as frontline paramedics, the air ambulance community, patients and some other health care professionals. Asking the public, those removed from paramedicine but responsible for health care, and public safety or public health personnel, and ensuring greater equity, inclusion and diversity, may have resulted in different outcomes. Northern and indigenous communities were not well represented despite our efforts. Future research should explore the views of these groups. Finally, some data collection took place prior to and during the COVID-19 pandemic. The role paramedics played in the COVID-19 response may have influenced informants’ views and contributions.

Conclusions

Perspectives from national thought leaders in Canadian paramedicine revealed a working framework centered on renewed and new accountabilities within the profession, to the public, and toward better aligning services within the needs of the public and health care system. Our results provide a conceptual framework made up of 10 guiding principles and six enablers that provide a consolidated lens and pathway to advance the profession while ensuring contextual and regional needs and differences can be accounted for. We call on the paramedic profession and its stakeholders to elaborate on and where appropriate enact the principles outlined while simultaneously leveraging identified enablers so that a future paramedicine will continue to evolve for the benefit of the public, its members, and the health care system.

References

- O’Meara P, Stirling C, Ruest M, Martin A. Community paramedicine model of care: an observational, ethnographic case study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:39. doi:10.1186/s12913-016-1282-0.

- Marshall EG, Clarke B, Peddle S, Jensen J. Care by design: new model of coordinated on-site primary and acute care in long-term care facilities. Can Fam Physician. 2015;61(3):e129–34.

- Carter AJE, Arab M, Cameron C, Harrison M, Pooler C, McEwan I, Austin M, Helmer J, Ozel G, Heathcote J, et al. A national collaborative to spread and scale paramedics providing palliative care in Canada: breaking down silos is essential to success. Prog Palliat Care. 2021;29(2):59–65. doi:10.1080/09699260.2020.1871173.

- Dainty KN, Seaton MB, Drennan IR, Morrison LJ. Home visit-based community paramedicine and its potential role in improving patient-centered primary care: a grounded theory study and framework. Health Serv Res. 2018;53(5):3455–70. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.12855.

- Cameron P, Carter A. Community paramedicine: a patch, or a real system improvement? CJEM. 2019;21(6):691–3. doi:10.1017/cem.2019.439.

- Agarwal G, Angeles R, Pirrie M, Marzanek F, McLeod B, Parascandalo J, Dolovich L. Effectiveness of a community paramedic-led health assessment and education initiative in a seniors' residence building: the Community Health Assessment Program through Emergency Medical Services (CHAP-EMS)). BMC Emerg Med. 2017;17(1):8. doi:10.1186/s12873-017-0119-4.

- Department of Health. Taking health care to the patient: transforming NHS Ambulance Services. London (UK): COI Communications for the Department of Health; 2005 Jun 2005. Available from: http://ircp.info/Portals/11/Future/NHS%20EMS%20Policy%20Recommendation2005.pdf.

- Association of Ambulance Chief Executives. Taking health care to the patient 2: a review of 6 years’ progress and recommendations for the future. 2011 Jun. Available from: http://aace.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/taking_health.care_to_the_patient_2.pdf.

- Emergency Medical Services Chiefs of Canada. The future of EMS in Canada: defining the new road ahead. Calgary (AB): Emergency Medical Services Chiefs of Canada; 2006 May 31. Available from: https://pscs.ca/images/stories/committee/EMSCC-Primary_Health_Care.pdf.

- Tavares W, Bowles R, Donelon B. Informing a Canadian paramedic profile: framing concepts, roles and crosscutting themes. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16(1):477. doi:10.1186/s12913-016-1739-1.

- Jensen JL, Bigham BL, Blanchard IE, Dainty KN, Socha D, Carter A, Brown LH, Travers AH, Craig AM, Brown R, et al. The Canadian National EMS Research Agenda: a mixed methods consensus study. CJEM. 2013;15(2):73–82. doi:10.2310/8000.2013.130894.

- Coffey B, MacPhee R, Socha D, Fischer SL. A physical demands description of paramedic work in Canada. Int J Ind Ergon. 2016;53:355–62. doi:10.1016/j.ergon.2016.04.005.

- Bowles RR, van Beek C, Anderson GS. Four dimensions of paramedic practice in Canada: defining and describing the profession. Austral J Paramed. 2017;14(3):1–11. doi:10.33151/ajp.14.3.539.

- Leyenaar M, McLeod B, Chan J, Tavares W, Costa A, Agarwal G. A scoping study and qualitative assessment of care planning and case management in community paramedicine. Irish J Para. 2018;3(1):1–16. doi:10.32378/ijp.v3i1.76.

- Tavares W, Boet S, Theriault R, Mallette T, Eva KW. Global rating scale for the assessment of paramedic clinical competence. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2013;17(1):57–67. doi:10.3109/10903127.2012.702194.

- Carleton RN, Afifi TO, Taillieu T, Turner S, Mason JE, Ricciardelli R, McCreary DR, Vaughan AD, Anderson GS, Krakauer RL, et al. Assessing the relative impact of diverse stressors among public safety personnel. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(4):1–15. doi:10.3390/ijerph17041234.

- Donnelly EA, Bradford P, Davis M, Hedges C, Socha D, Morassutti P, Pichika SC. What influences safety in paramedicine? Understanding the impact of stress and fatigue on safety outcomes. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. 2020;1(4):460–73. doi:10.1002/emp2.12123.

- Bigham BL, Buick JE, Brooks SC, Morrison M, Shojania KG, Morrison LJ. Patient safety in emergency medical services: a systematic review of the literature. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2012;16(1):20–35. doi:10.3109/10903127.2011.621045.

- Susskind R, Susskind D. The future of the professions: how technology will transform the work of human experts. Oxford (UK): Oxford University Press; 2015.

- McCann L, Granter E, Hyde P, Hassard J. Still blue‐collar after all these years? An ethnography of the professionalization of emergency ambulance work. J Manag Stud. 2013;50(5):750–76. doi:10.1111/joms.12009.

- Elo S, Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs. 2008;62(1):107–15. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x.

- Crotty M. The foundations of social research: meaning and perspective in the research process. London (UK): SAGE Publications; 1998.

- Paramedic Association of Canada. National occupational competency profile. Ottawa (ON): Paramedic Association of Canada; 2015. http://paramedic.ca/site/nocp?nav=02.

- Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, editors. The SAGE handbook of qualitative research. Thousand Oaks (CA): SAGE Publications; 2011.

- Association of Ambulance Chief Executives. Public Health England. Developing a public health approach withing the ambulance sector: discussion paper. Crown copyright - Public Health England. 2021.

- EMS Agenda 2050 Technical Expert Panel. EMS agenda 2050: a people-centered vision for the future of emergency medical services. Report No. DOT HS 812 664. Washington, DC: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration; 2019. Available from: https://www.ems.gov/pdf/EMS-Agenda-2050.pdf.