Abstract

Definitive management of trauma is not possible in the out-of-hospital environment. Rapid treatment and transport of trauma casualties to a trauma center are vital to improve survival and outcomes. Prioritization and management of airway, oxygenation, ventilation, protection from gross aspiration, and physiologic optimization must be balanced against timely patient delivery to definitive care. The optimal prehospital airway management strategy for trauma has not been clearly defined; the best choice should be patient-specific.

NAEMSP recommends:

The approach to airway management and the choice of airway interventions in a trauma patient requires an iterative, individualized assessment that considers patient, clinician, and environmental factors.

Optimal trauma airway management should focus on meeting the goals of adequate oxygenation and ventilation rather than on specific interventions. Emergency medical services (EMS) clinicians should perform frequent reassessments to determine if there is a need to escalate from basic to advanced airway interventions.

Management of immediately life-threatening injuries should take priority over advanced airway insertion.

Drug-assisted airway management should be considered within a comprehensive algorithm incorporating failed airway options and balanced management of pain, agitation, and delirium.

EMS medical directors must be highly engaged in assuring clinician competence in trauma airway assessment, management, and interventions.

Introduction

Prehospital advanced trauma airway management includes several low-frequency, high-consequence procedures, while mastery of basic trauma airway assessment and management is a foundational skill needed for every patient. Appropriate prioritization of airway management within the larger context of the patient, clinician, and environmental considerations drives the choice of necessary airway interventions. Decisions on airway management in trauma patients should be targeted toward achieving specific resuscitation goals to maintain focus on achieving the best patient outcomes rather than on the performance of specific procedures. Airway management failures account for 8 to 15% of potentially preventable trauma deaths (Citation1–4). As such, medical director involvement in the assurance of EMS clinician initial and ongoing competency in procedural skills and in critical decision-making are core elements of quality prehospital trauma airway management.

General Approach to the Prehospital Trauma Airway

The approach to airway management and the choice of airway interventions in a trauma patient requires an iterative, individualized assessment which considers patient, clinician, and environmental factors.

Appropriate airway management options in the trauma patient should be viewed as dynamic, demanding modification based on multiple factors that may vary throughout the prehospital care phase. Frequent patient assessment promotes recognition of clinical trends that may require changes in airway management strategy. Placing clinical assessment of patient factors in the context of the clinician and environmental factors clarifies the appropriate options for optimal patient outcomes.

Patient Factors

Trauma patient evaluation for advanced airway management should include initial and repeat assessments for ineffective ventilation, hypoxia, airway obstruction, risk of aspiration, profound shock, and severe cognitive impairment/agitation/altered mental status (Citation5–7). Many of these factors can be temporized in the prehospital environment with basic interventions such as positioning, supplemental oxygen, airway adjuncts, and ongoing hemodynamic resuscitation. Altered or deteriorating mental status is one of the most common indications for advanced airway management in trauma patients (Citation8), although it is not always necessary even in that clinical scenario (Citation5, Citation9). While a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score <8 was traditionally used as an indication for advanced airway management (Citation7, Citation10), subsequent research suggests that a GCS score of < 8 alone does not correlate well with hypoxia, aspiration, need for prolonged intensive care unit care, or mortality, and thus must be only one component of the decision for advanced airway management (Citation11). In cases of hemodynamic instability, patients must be resuscitated prior to placement of advanced airways to reduce the risk of further hypoperfusion, cardiovascular collapse, and worse outcomes including peri-intubation arrest (Citation12, Citation13).

Clinician Factors

Successful prehospital airway management is dependent on the skill and competency of the clinician, which is difficult to both attain and maintain (Citation14–17). Provider proficiency, experience, and comfort level, as well as their belief in the benefit of specific airway procedures may affect both the provider’s airway choice as well as the resultant short and long-term patient outcomes.

Environmental Factors

Environmental factors that influence decisions on advanced airway management may include distance to the hospital, locally available resources, and scene safety. Patients who are close to a trauma center may be better managed with basic airway interventions given that advanced interventions may lead to delays in transport and definitive care (Citation18, Citation19). Only critical interventions should be performed on scene, and additional resuscitation and interventions should occur en route to definitive care. In some cases, interventions may be optimal after arrival at the hospital. Alternatively, a patient needing to travel a long distance in an aircraft may benefit from early advanced airway management to limit predictable risk of decompensation including hypoxia and hypercarbia, which would exacerbate the underlying injury (such as TBI) (Citation20). In some circumstances, advanced airway management must be delayed due to hazards or threats in complex tactical or operational environments (Citation21).

Evidence suggests that the location (i.e., prehospital vs. shortly following hospital arrival) of advanced airway management may be associated with patient outcomes. While some studies found that in-hospital intubation is associated with better outcomes compared with prehospital intubation (Citation22, Citation23), others found that location of intubation was not associated with mortality or early ventilator-acquired pneumonia in spite of increased intensive care unit, mechanical ventilation, and hospital length of stay (Citation24). A military study noted lower survival for prehospital as compared to emergency department intubation (Citation22). Hawkins et al. evaluated 288 intubated pediatric trauma patients and noted that overall mortality was highest in the more severely injured scene intubation group (29.7%) as compared with those intubated at the referring hospital or pediatric trauma center, but age, injury severity, and neurologic status were more associated with mortality than the intubation location (Citation25).

Goals of Trauma Airway Management

Optimal trauma airway management should focus on meeting the goals of adequate oxygenation and ventilation rather than on specific interventions. EMS clinicians should perform frequent reassessments to determine if there is a need to escalate from basic to advanced airway interventions.

Effective airway maneuvers are of crucial importance in the critically injured patient and should be goal-directed to prevent hypoxemia, hypercarbia, hypocarbia, and hypotension (Citation26), particularly those with traumatic brain injury, burns, and hemorrhagic shock. While training often focuses on advanced airway interventions in the care of the trauma patient, this approach loses sight of the higher priority: maintaining oxygenation and ventilation. The two guiding principles are:

Rescue care should focus on oxygenation and ventilation — not specific airway interventions.

Airway care should begin with basic procedures, escalating to advanced interventions only when indicated.

The current prehospital traumatic brain injury (TBI) literature underscores two important observations: 1) oxygenation and ventilation are critical to improved TBI outcomes, and 2) while intended to optimize care, advanced airway management may not be associated with controlled oxygenation or ventilation and may be linked to poor outcomes. These overarching observations underscore that optimization of oxygenation and ventilation must receive the highest priority in TBI care. Studies highlighting the importance of oxygenation and ventilation include Davis et al. (Citation27) and Kim et al. (Citation28) Chuck et al. recently published a cross-sectional analysis of statewide EMS guidelines specific to TBI that suggests avoidance of hyperventilation/hypocapnia and hypoxemia (goal SpO2 > 90%) and supports endotracheal intubation only in those patients with depressed respiratory effort (Citation29).

Resuscitation efforts should start with the most basic interventions, escalating to more advanced interventions only when basic measures are no longer sufficient. Early and aggressive basic airway management including suction, oropharyngeal or nasopharyngeal airways, supplemental oxygen, and assisted ventilations with a bag-valve-mask are the mainstays of rapid early intervention. There is ongoing controversy with trauma airway management, most prominently in the TBI patient, in whom hypoxemia and hypotension exacerbate secondary brain injury. Davis et al. and Dumont et al. clearly described aggressive ventilation and hypocarbia worsening outcomes (Citation27, Citation30). Recent guidance re-emphasizes quality basic airway support to assure adequate oxygenation and ventilation concurrent with resuscitation to avoid or reverse hypotension during rapid transport to definitive care (Citation31). Of note, Davis et al. (Citation27) found that hyperventilation is common after intubation for TBI, underscoring that intubation often leads to inadvertent overventilation. Escalation to increasingly invasive airway interventions should only be applied as required to meet those goals and prevent secondary injury due to hypoxia, hypercarbia, or the consequences of an unsecured airway including aspiration. Given these findings, emphasis on meticulous surveillance of airway status using continuous monitoring (including oximetry and capnography) and frequent reassessment is of the utmost importance in facilitating the best patient outcome.

Even when basic measures do not provide for adequate oxygenation and ventilation, prehospital advanced airway placement in the trauma patient remains controversial because of the evidence that outcomes are worsened with endotracheal intubation. While the supraglottic airway (SGA) may represent an alternative, data are limited, and there are concerns over aspiration risks and the inability to optimize oxygenation and ventilation. The ongoing Prehospital Airway Control Trial (NCT 04100564) may clarify which option is best in trauma patients. A recent Cochrane review concluded that of the range of techniques for endotracheal intubation, use of video laryngoscopy improves glottic views, prevents airway trauma, and reduces the incidence of failed intubations (Citation32). Studies show that prehospital intubation attempts may lead to hypoxia and then cardiac arrest (Citation33, Citation34). Some evidence suggests that close airway surveillance and monitoring helps significantly in limiting hypoxic adverse events during advanced airway maneuvers (Citation35).

A comprehensive approach to trauma airway management proposed by Gamberini et al. includes three pillars: operator experience, airway devices, and pharmacological choices (Citation24). Based on a recent review of the literature, this multifaceted approach rather than focus on the procedure of intubation itself leads to improved overall outcomes. When endotracheal intubation is unsuccessful and advancing to surgical airway is considered, Schauer et al. found no difference in short-term outcomes between combat casualties managed with cricothyrotomy versus SGA (Citation22). Significant airway burns and expanding neck hematomas may be among few conditions that warrant expedited escalation of airway interventions, as the lack of an anticipatory approach with early intervention can result in a failed airway.

As the need for more invasive airway management is anticipated, the patient should be optimized physiologically to tolerate both the airway intervention (i.e., SGA, endotracheal intubation, surgical airway, mechanical ventilation) and the potential pharmacologic interventions needed to facilitate them (e.g., drug-facilitated intubation, post-intubation medication management) without untoward effects that worsen outcomes (e.g., hypotension, hypoxia, hyper- or hypocarbia).

Priorities in Trauma Airway Management

Management of immediately life-threatening injuries should take priority over advanced airway insertion.

In the prehospital trauma patient, treatment of hemorrhagic shock and other immediate life threats should be the focus of patient management rather than placement of an advanced airway. Potentially harmful effects of endotracheal intubation and positive pressure ventilation on the trauma patient in hemorrhagic shock include reduced cardiac output, apnea, hypoxia, hypocapnia due to inadvertent hyperventilation (Citation28, Citation36), and prolongation of scene times (Citation19). Unless there is an injury leading to airway obstruction, the recommendation is for resuscitation with blood products prior to airway management (Citation37). Studies have affirmed the incidence of hypotension (Citation38) and cardiac arrest in hemorrhagic shock patients undergoing intubation (Citation29). Drug-assisted airway management (DAAM) and decreases in cardiac output related to positive pressure ventilation can also contribute to hypotension in patients in hemorrhagic shock, potentially leading to peri-intubation cardiac arrest (Citation37, Citation39–43).

The traditional sequence of airway, breathing, and circulation (ABCs) has been practiced in trauma care for decades despite the lack of supporting evidence. More recently, authors have advocated for a CAB or circulation-first approach (Citation13). The Trauma Hemostasis and Oxygenation Research (THOR) study group consensus opinion is that the focus in hemorrhagic shock should be on improving blood flow over increasing oxygenation (Citation44). Chou et al. found field intubation in patients with hemorrhagic shock was associated with higher mortality (Citation45). In addition to red cells, plasma may be useful in the treatment of hemorrhagic shock prior to intubation (Citation46). For immediately life-threatening injuries, a circulation-first approach in the field may focus on basic airway maneuvers and rapid transport to definitive care in many prehospital systems.

Drug Assisted Airway Management in the Trauma Patient

Drug-assisted airway management should be considered within a comprehensive algorithm incorporating failed airway options and balanced management of pain, agitation, and delirium.

Some trauma patients (especially those with TBI) have intact protective airway reflexes and, therefore, may require pharmacologic assistance to undergo advanced airway management. DAAM encompasses the spectrum of techniques using pharmacologic agents to facilitate advanced airway insertion, including the use of neuromuscular blockade assisted intubation (Citation47). The decision to use DAAM must be personalized according to the patient, clinician, and environmental factors present in each scenario. Because of the complexities and risks inherent in DAAM, EMS clinicians entrusted with this skill should be carefully selected, trained, credentialed, and their skill retention monitored by the EMS medical director.

DAAM medications may adversely affect patient physiology in the trauma patient, particularly those in hemorrhagic shock and those with TBI. Hemorrhagic shock may alter the need for medication administration, and lower doses may be needed in select patients (Citation48). Trauma patients may be physiologically labile and therefore require continuous monitoring when the airway is being managed. This is particularly true in TBI patients as not only incidence but also length of hypotension and hypoxia negatively affect patient outcomes, and these may be exacerbated by DAAM (Citation28, Citation49).

Training in Trauma Airway Management

EMS medical directors must be highly engaged in assuring clinician competence in trauma airway assessment, management, and interventions.

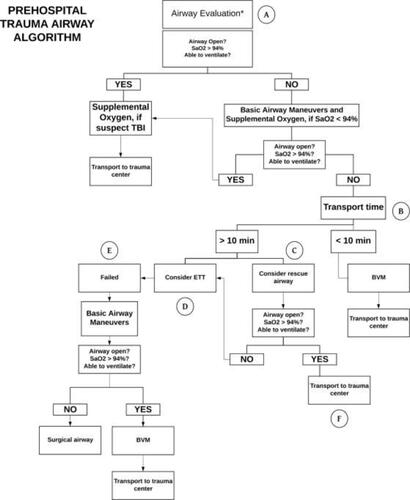

Prehospital management of the trauma airway begins with establishing best practices, yet the effect of these recommendations is dependent on their appropriate application within each agency. The development of guidelines, education, maintenance of skills, and quality assurance are dependent on a highly involved EMS medical director. Medical oversight should adhere to quality management practices similar to those in airway management of nontrauma patients. Unique aspects of the trauma airway that will need to be taken into consideration include the potential effects of specific injuries, hypotension related to hemorrhagic shock, consideration of cervical spine injuries, and time/distance to the nearest appropriate facility in the area. Some have tried an algorithmic approach to the prehospital trauma airway, such as the one suggested by Brown et al. in (Citation19). While such an approach may have merit in some cases, it does not promote the refined critical decision-making needed to tailor care to the demands of specific trauma patient types (i.e., TBI) in the framework of the individual EMS clinician’s skills and credentialing.

While developing guidelines for trauma airway management, medical directors must focus on common barriers to their application and adoption by clinicians. Barriers include limitations on airway management practice opportunities including the ideal, hospital-based live patient clinicals, or even cadaver training. While high fidelity simulation helps with critical thinking and technical skills, the nuances of live experiences are invaluable in providing experience for actual patient management. Guidelines that are specific to the agency and take agency’s clinician expertise and experience into consideration are paramount and have documented positive effects on the actual use of a guideline (Citation50). Guidelines should describe when to escalate, what airway goals are targeted, choice of appropriate patient destination, and potentially mode of transport when applicable.

Both initial and continuing education on high-criticality/low-frequency airway intervention such as the trauma airway set the stage for assuring clinician competency. Similar to other high-stakes patient populations, medical director involvement in education and quality assurance is associated with improved prehospital clinician adherence to guidelines and therefore has the potential to affect patient outcomes (Citation51–54). With respect to trauma airway management, the guiding principle is that there are many ways to educate and all of them are likely effective as long as they are tailored to the level of clinician and incorporate some degree of ongoing education or structured review (Citation55, Citation56).

Figure 1. Prehospital adult trauma airway management algorithm (Citation19). Adapted from Brown CVR, Inaba K, Shatz DV, Moore EE, Ciesla D, Sava JA, Alam HB, Brasel K, Vercruysse G, Sperry JL, et al. Western Trauma Association critical decisions in trauma: airway management in adult trauma patients. Trauma Surg Acute Care Open. 2020;5(1):e000539. This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY- NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non- commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited, appropriate credit is given, any changes made indicated, and the use is non- commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Future Research

Limited evidence exists in many areas on this subject, and there are ample opportunities to fill research gaps (). Some additional clarity is expected from ongoing studies such as the Prehospital Airway Control Trial study, comparing SGA and endotracheal intubation in trauma patients. In blunt trauma, there is no evidence of improved outcomes with advanced life support interventions, including intravenous access and airway management, which are associated with higher complication and mortality rates (Citation57). Secondary analysis of traumatic arrests in the ROC and PROPHET registries showed decreased odds of survival from traumatic arrest with SGA or endotracheal intubation compared to bag-valve-mask alone. This result is potentially biased by uncontrolled confounders such as injury severity and deserves further inquiry (Citation58).

Table 1. Prehospital trauma airway management research opportunities. Modified from Brown et al. (Citation19).

Summary

In traumatically injured patients, choices of airway interventions and their timing must be balanced with the need to optimize hemodynamic resuscitation and prompt transport of the patient to a designated facility for definitive care of his or her injuries. As a result, unless there is an imperative to secure the airway in an injured patient to prevent impending obstruction, endotracheal intubation in the field for a trauma patient in hemorrhagic shock is not recommended and resuscitation of hemorrhagic shock should be the priority over advanced airway management. As the need for more invasive airway management is anticipated, the patient should first be optimized physiologically to tolerate both the airway intervention and to avoid the known untoward effects that worsen outcomes. EMS medical directors should create guidelines that emphasize quality basic airway management coupled with rapid transport to definitive care in the majority of patients, with ongoing hemodynamic resuscitation in transit (Citation7). If adequate oxygenation and ventilation goals cannot be met with basic airway interventions, then a deliberate escalating approach to more advanced methods should be employed.

References

- Davis DP, Koprowicz KM, Newgard CD, Daya M, Bulger EM, Stiell I, Nichol G, Stephens S, Dreyer J, Minei J, et al. The relationship between out-of-hospital airway management and outcome among trauma patients with Glasgow Coma Scale Scores of 8 or less. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2011;15(2):184–92. doi:https://doi.org/10.3109/10903127.2010.545473.

- Lairet JR, Bebarta VS, Burns CJ, Lairet KF, Rasmussen TE, Renz EM, King BT, Fernandez W, Gerhardt R, Butler F, et al. Prehospital interventions performed in a combat zone: a prospective multicenter study of 1,003 combat wounded. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;73(2 Suppl 1):S38–S42. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/TA.0b013e3182606022.

- Wang HE, Yealy DM. Out-of-hospital endotracheal intubation: where are we? Ann Emerg Med. 2006;47(6):532–41. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.01.016.

- Crewdson K, Fragoso-Iniguez M, Lockey DJ. Requirement for urgent tracheal intubation after traumatic injury: a retrospective analysis of 11,010 patients in the Trauma Audit Research Network database. Anaesthesia. 2019;74(9):1158–64. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/anae.14692.

- Lockey DJ, Healey B, Crewdson K, Chalk G, Weaver AE, Davies GE. Advanced airway management is necessary in prehospital trauma patients. Br J Anaesth. 2015;114(4):657–62. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/bja/aeu412.

- Sise MJ, Shackford SR, Sise CB, Sack DI, Paci GM, Yale RS, O'Reilly EB, Norton VC, Huebner BR, Peck KA. Early intubation in the management of trauma patients: indications and outcomes in 1,000 consecutive patients. J Trauma. 2009;66(1):32–40, discussion 9–40. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/TA.0b013e318191bb0c.

- Mayglothling J, Duane TM, Gibbs M, McCunn M, Legome E, Eastman AL, Whelan J, Shah KH, Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma. Emergency tracheal intubation immediately following traumatic injury: an Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma practice management guideline. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;73(5 Suppl 4):S333–S40. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/TA.0b013e31827018a5.

- Miraflor E, Chuang K, Miranda MA, Dryden W, Yeung L, Strumwasser A, Victorino GP. Timing is everything: delayed intubation is associated with increased mortality in initially stable trauma patients. J Surg Res. 2011;170(2):286–90. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2011.03.044.

- Duncan R, Thakore S. Decreased Glasgow Coma Scale score does not mandate endotracheal intubation in the emergency department. J Emerg Med. 2009;37(4):451–5. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2008.11.026.

- Winchell RJ, Hoyt DB. Endotracheal intubation in the field improves survival in patients with severe head injury. Trauma Research and Education Foundation of San Diego. Arch Surg. 1997;132(6):592–7. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/archsurg.1997.01430300034007.

- Davis DP, Vadeboncoeur TF, Ochs M, Poste JC, Vilke GM, Hoyt DB. The association between field Glasgow Coma Scale score and outcome in patients undergoing paramedic rapid sequence intubation. J Emerg Med. 2005;29(4):391–7. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2005.04.012.

- Spaite DW, Hu C, Bobrow BJ, Chikani V, Barnhart B, Gaither JB, Denninghoff KR, Adelson PD, Keim SM, Viscusi C, et al. The effect of combined out-of-hospital hypotension and hypoxia on mortality in major traumatic brain injury. Ann Emerg Med. 2017;69(1):62–72. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2016.08.007.

- Ferrada P, Callcut RA, Skarupa DJ, Duane TM, Garcia A, Inaba K, Khor D, Anto V, Sperry J, Turay D, et al. Circulation first—the time has come to question the sequencing of care in the ABCs of trauma; an American Association for the Surgery of Trauma multicenter trial. World J Emerg Surg. 2018;13:8. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s13017-018-0168-3.

- Benger JR, Kirby K, Black S, Brett SJ, Clout M, Lazaroo MJ, Nolan JP, Reeves BC, Robinson M, Scott LJ, et al. Effect of a Strategy of a supraglottic airway device vs tracheal intubation during out-of-hospital cardiac arrest on functional outcome: the AIRWAYS-2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;320(8):779–91. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.11597.

- Wang HE, Seitz SR, Hostler D, Yealy DM. Defining the learning curve for paramedic student endotracheal intubation. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2005;9(2):156–62. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10903120590924645.

- Wang HE, Kupas DF, Hostler D, Cooney R, Yealy DM, Lave JR. Procedural experience with out-of-hospital endotracheal intubation. Crit Care Med. 2005;33(8):1718–21.

- Pepe PE, Roppolo LP, Fowler RL. Prehospital endotracheal intubation: elemental or detrimental? Crit Care. 2015;19:121. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-015-0808-x.

- Cudnik MT, Newgard CD, Wang H, Bangs C, Herringtion R. Endotracheal intubation increases out-of-hospital time in trauma patients. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2007;11(2):224–9. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10903120701205208.

- Brown CVR, Inaba K, Shatz DV, Moore EE, Ciesla D, Sava JA, Alam HB, Brasel K, Vercruysse G, Sperry JL, et al. Western Trauma Association critical decisions in trauma: airway management in adult trauma patients. Trauma Surg Acute Care Open. 2020;5(1):e000539. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/tsaco-2020-000539.

- Cudnik MT, Newgard CD, Wang H, Bangs C, Herrington R. Distance impacts mortality in trauma patients with an intubation attempt. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2008;12(4):459–66. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10903120802290745.

- Callaway DW, Smith ER, Cain J, Shapiro G, Burnett WT, McKay SD, Mabry R. Tactical emergency casualty care (TECC): guidelines for the provision of prehospital trauma care in high threat environments. J Spec Oper Med. 2011;11(3):104–22.

- Schauer SG, Naylor JF, Chow AL, Maddry J, Cunningham CW, Blackburn MB, Nawn CD, April MD. Survival of casualties undergoing prehospital supraglottic airway placement versus cricothyrotomy. J Spec Oper Med. 2019;19(2):91–4.

- Bochicchio GV, Ilahi O, Joshi M, Bochicchio K, Scalea TM. Endotracheal intubation in the field does not improve outcome in trauma patients who present without an acutely lethal traumatic brain injury. J Trauma. 2003;54(2):307–11.

- Gamberini L, Baldazzi M, Coniglio C, Gordini G, Bardi T. Prehospital airway management in severe traumatic brain injury. Air Med J. 2019;38(5):366–73. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amj.2019.06.001.

- Hawkins RB, Raymond SL, Hamann HC, Taylor JA, Mustafa MM, Islam S, Larson SD. Outcomes after prehospital endotracheal intubation in suburban/rural pediatric trauma. J Surg Res. 2020;249:138–44. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2019.11.034.

- Kim MW, Shin SD, Song KJ, Ro YS, Kim YJ, Hong KJ, Jeong J, Kim TH, Park JH, Kong SY. Interactive effect between on-scene hypoxia and hypotension on hospital mortality and disability in severe trauma. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2018;22(4):485–96. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10903127.2017.1416433.

- Davis DP, Dunford JV, Poste JC, Ochs M, Holbrook T, Fortlage D, Size MJ, Kennedy F, Hoyt DB. The impact of hypoxia and hyperventilation on outcome after paramedic rapid sequence intubation of severely head-injured patients. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2004;57(1):1–10.

- Kim WY, Kwak MK, Ko BS, Yoon JC, Sohn CH, Lim KS, Andersen LW, Donnino MW. Factors associated with the occurrence of cardiac arrest after emergency tracheal intubation in the emergency department. PLoS One. 2014;9(11):e112779. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0112779.

- Chuck CC, Martin TJ, Kalagara R, Shaaya E, Kheirbek T, Cielo D. Emergency medical services protocols for traumatic brain injury in the United States: a call for standardization. Injury. 2021;52(5):1145–50. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.injury.2021.01.008.

- Dumont TM, Visioni AJ, Rughani AI, Tranmer BI, Crookes B. Inappropriate prehospital ventilation in severe traumatic brain injury increases in-hospital mortality. J Neurotrauma. 2010;27(7):1233–41. doi:https://doi.org/10.1089/neu.2009.1216.

- Lockey DJ, Wilson M. Early airway management of patients with severe head injury: opportunities missed? Anaesthesia. 2020;75(1):7–10. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/anae.14854.

- Lewis SR, Butler AR, Parker J, Cook TM, Schofield-Robinson OJ, Smith AF. Videolaryngoscopy versus direct laryngoscopy for adult patients requiring tracheal intubation: a Cochrane systematic review. Br J Anaesth. 2017;119(3):369–83. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/bja/aex228.

- Dunford JV, Davis DP, Ochs M, Doney M, Hoyt DB. Incidence of transient hypoxia and pulse rate reactivity during paramedic rapid sequence intubation. Ann Emerg Med. 2003;42(6):721–8. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0196-0644(03)00660-7.

- Mort TC. Emergency tracheal intubation: complications associated with repeated laryngoscopic attempts. Anesth Analg. 2004;99(2):607–13.

- Jarvis JL, Gonzales J, Johns D, Sager L. Implementation of a clinical bundle to reduce out-of-hospital peri-intubation hypoxia. Ann Emerg Med. 2018;72(3):272–9. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2018.01.044.

- Wang HE, Brown SP, MacDonald RD, Dowling SK, Lin S, Davis D, Schreiber MA, Powell J, van Heest R, Daya M. Association of out-of-hospital advanced airway management with outcomes after traumatic brain injury and hemorrhagic shock in the ROC hypertonic saline trial. Emerg Med J. 2014;31(3):186–91. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/emermed-2012-202101.

- Hudson AJ, Strandenes G, Bjerkvig CK, Svanevik M, Glassberg E. Airway and ventilation management strategies for hemorrhagic shock. To tube, or not to tube, that is the question! J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2018;84(6S Suppl 1):S77–S82. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/TA.0000000000001822.

- Green RS, Butler MB, Erdogan M. Increased mortality in trauma patients who develop postintubation hypotension. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2017;83(4):569–74. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/TA.0000000000001561.

- Heffner AC, Swords DS, Neale MN, Jones AE. Incidence and factors associated with cardiac arrest complicating emergency airway management. Resuscitation. 2013;84(11):1500–4. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resuscitation.2013.07.022.

- Shafer SL. Shock values. Anesthesiology. 2004;101(3):567–8. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/00000542-200409000-00002.

- Cournand A, Motley HL. Physiological studies of the effects of intermittent positive pressure breathing on cardiac output in man. Am J Physiol. 1948;152(1):162–74. doi:https://doi.org/10.1152/ajplegacy.1947.152.1.162.

- Pepe PE, Roppolo LP, Fowler RL. The detrimental effects of ventilation during low-blood-flow states. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2005;11(3):212–8.

- Pepe PE, Lurie KG, Wigginton JG, Raedler C, Idris AH. Detrimental hemodynamic effects of assisted ventilation in hemorrhagic states. Crit Care Med. 2004;32(9 Suppl):S414–S20.

- Woolley T, Thompson P, Kirkman E, Reed R, Ausset S, Beckett A, Bjerkvig C, Cap AP, Coats T, Cohen M, et al. Trauma Hemostasis and Oxygenation Research Network position paper on the role of hypotensive resuscitation as part of remote damage control resuscitation. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2018;84(6S Suppl 1):S3–s13. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/TA.0000000000001856.

- Chou D, Harada MY, Barmparas G, Ko A, Ley EJ, Margulies DR, Alban RF. Field intubation in civilian patients with hemorrhagic shock is associated with higher mortality. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2016;80(2):278–82. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/TA.0000000000000901.

- Sperry JL, Guyette FX, Brown JB, Yazer MH, Triulzi DJ, Early-Young BJ, Adams PW, Daley BJ, Miller RS, Harbrecht BG, et al. Prehospital plasma during air medical transport in trauma patients at risk for hemorrhagic shock. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(4):315–26. doi:https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1802345.

- Jarvis JL, Lyng JW, Miller BL, Perlmutter MC, Abraham H, Sahni R. Prehospital drug assisted airway management: an NAEMSP Position Statement and Resource Document. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2022;26(0):42–53. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10903127.2021.1990447.

- Egan ED, Johnson KB. The influence of hemorrhagic shock on the disposition and effects of intravenous anesthetics: a narrative review. Anesth Analg. 2020;130(5):1320–30. doi:https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000004654.

- Manley G, Knudson MM, Morabito D, Damron S, Erickson V, Pitts L. Hypotension, hypoxia, and head injury: frequency. Arch Surg. 2001;136(10):1118–23. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/archsurg.136.10.1118.

- Rubiano AM, Vera DS, Montenegro JH, Carney N, Clavijo A, Carreño JN, Gutierrez O, Mejia J, Ciro JD, Barrios ND, et al. Recommendations of the Colombian Consensus Committee for the management of traumatic brain injury in prehospital, emergency department, surgery, and intensive care (Beyond One Option for Treatment of Traumatic Brain Injury: A Stratified Protocol [BOOTStraP]). J Neurosci Rural Pract. 2020;11(1):7–22. doi:https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0040-1701370.

- Marino MC, Ostermayer DG, Mondragon JA, Camp EA, Keating EM, Fornage LB, Brown CA, Shah MI. Improving prehospital protocol adherence using bundled educational interventions. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2018;22(3):361–9. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10903127.2017.1399182.

- Stoecklein HH, Youngquist ST. The role of medical direction in systems of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Cardiol Clin. 2018;36(3):409–17. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccl.2018.03.008.

- Jensen M, Louka A, Barmaan B. Effect of Suction Assisted Laryngoscopy Airway Decontamination (SALAD) training on intubation quality metrics. Air Med J. 2019;38(5):325. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amj.2019.07.002.

- Forney ED, Stokes NA, Ashley DW, Montgomery A, Benjamin Christie D. Can education and enhanced medical director oversight improve definitive airway control in the prehospital environment? Am Surg. 2021;87(1):159–61. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0003134820945228.

- Skube ME, Witthuhn S, Mulier K, Boucher B, Lusczek E, Beilman GJ. Assessment of prehospital hemorrhage and airway care using a simulation model. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2018;85(1S Suppl 2):S27–S32. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/TA.0000000000001800.

- Luckey-Smith K, High K, Cole E. Effectiveness of surgical airway training laboratory and assessment of skill and knowledge fade in surgical airway establishment among prehospital providers. Air Med J. 2020;39(5):369–73. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amj.2020.05.019.

- Farrell MS, Emery B, Caplan R, Getchell J, Cipolle M, Bradley KM. Outcomes with advanced versus basic life support in blunt trauma. Am J Surg. 2020;220(3):783–6. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2020.01.012.

- Evans CC, Petersen A, Meier EN, Buick JE, Schreiber M, Kannas D, Austin MA, Resuscitation Outcomes Consortium Investigators. Prehospital traumatic cardiac arrest: management and outcomes from the resuscitation outcomes consortium epistry-trauma and PROPHET registries. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2016;81(2):285–93. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/TA.0000000000001070.