Abstract

Bag-valve-mask ventilation and endotracheal intubation have been the mainstay of prehospital airway management for over four decades. Recently, supraglottic device use has risen due to various factors. The combination of bag-valve-mask ventilation, endotracheal intubation, and supraglottic devices allows for successful airway management in a majority of patients. However, there exists a small portion of patients who are unable to be intubated and cannot be adequately ventilated with either a facemask or a supraglottic airway. These patients require an emergent surgical airway. A surgical airway is an important component of all airway algorithms, and in some cases may be the only viable approach; therefore, it is imperative that EMS agencies that are credentialed to manage airways have the capability to perform surgical airways when appropriate. The National Association of Emergency Medical Services Physicians (NAEMSP) recommends the following for emergency medical services (EMS) agencies that provide advanced airway management.

A surgical airway is reasonable in the prehospital setting when the airway cannot be secured by less invasive means.

When indicated, a surgical airway should be performed without delay.

A surgical airway is not a substitute for other airway management tools and techniques. It should not be the only rescue option available.

Success of an open surgical approach using a scalpel is higher than that of percutaneous Seldinger techniques or needle-jet ventilation in the emergency setting.

Key words:

Introduction—Availability of Surgical Airways

A surgical airway is reasonable in the prehospital setting when the airway cannot be secured by less invasive means.

Emergency airway management in critically ill and injured patients is very challenging, especially in the prehospital setting. While endotracheal intubation (ETI) is the mainstay of advanced airway management, difficult intubation occurs in roughly 25% of prehospital airways and is difficult to predict (Citation1). In addition, about 30% of prehospital intubations fail on the first attempt, which increases the risk of complications (Citation1, Citation2).

Therefore, it is critical for EMS clinicians to have multiple backups and anticipate next steps in the event of a difficult or failed airway. A supraglottic airway (SGA) should be available to all prehospital clinicians, since SGAs are a standard backup device in modern difficult airway algorithms and have become widely used as both primary and rescue devices in the prehospital setting. The combination of bag-valve-mask (BVM) ventilation, ETI, and an SGA has a high likelihood of success (Citation3). However, there are instances where BVM ventilation, ETI, and a SGA are all unsuccessful and a surgical airway is the only remaining alternative (Citation2). There are also instances where BVM ventilation, ETI, and SGA are unfeasible and a surgical airway is the primary approach; for example, a patient with major injury to both the face and airway, or those with tumors or other obstructions to the airway (Citation3, Citation4). Therefore, it is essential that advanced EMS clinicians be trained to perform surgical airways.

Historically, there has been uncertainty about the appropriateness of prehospital surgical airways based on concerns that they were overutilized and had high complication and failure rates. These concerns were based on studies published in the 1990s that showed utilization rates of 7.7 to 14.9% and long-term patient survival rates of less than 10% (Citation4, Citation5). In all of these studies, the agencies involved did not use paralytic agents, and more than one-third of cricothyrotomies were performed on patients who were already in cardiac arrest. One study reported on 56 prehospital surgical airways with only three patients with good neurologic recovery (5%); however, about 40% of these procedures were performed on patients who were already in cardiac arrest from blunt trauma (Citation4). During the same time period there were other studies published, from agencies using neuromuscular blocking agents to facilitate intubation, and these reported surgical airway utilization rates of 1.1 to 2.4% with better patient survival (Citation6–8). Recent data show that with the widespread use of SGAs the incidence of surgical airways in the prehospital setting is very low, about 0.5–0.7% per database reports of EMS agencies that provide advanced airway management (Citation9, Citation10). Also, in recent reports the success rate of prehospital surgical airways is variable and dependent on the circumstances and environment. Several reports of nonphysician prehospital personnel performing open (scalpel) surgical airways show success rates of 90 to 100% (Citation9–14).

In the combat setting, the distribution of tracheal intubation, SGA, and surgical airway management is different from that of the civilian population due to the inherent nature of combat. In a retrospective study of prehospital surgical airways performed in combat, the success rate was 68%. When performed by a physician or physician assistant, the success rate was higher at 85%. Of combat-related trauma admissions at that time, 0.62% required prehospital surgical airways (Citation15, Citation16). In a more recent study, approximately 4.9% of a combat population underwent prehospital airway management, including 1117 tracheal intubations (81%), only 27 SGA placements (2%), and 230 open surgical airways (17%) (Citation17).

Timing of Surgical Airway

When indicated, a surgical airway should be performed without delay.

Emergent surgical airways are often required in stressful and chaotic environments, when other procedures have failed and the patient’s status is rapidly deteriorating. A common mistake is to delay the surgical airway while persisting with a failed technique or contemplating another less invasive solution (Citation18). Regular training is necessary such that clinicians are comfortable with both the critical decision-making and the technical performance of the procedure in a timely manner (Citation19, Citation20).

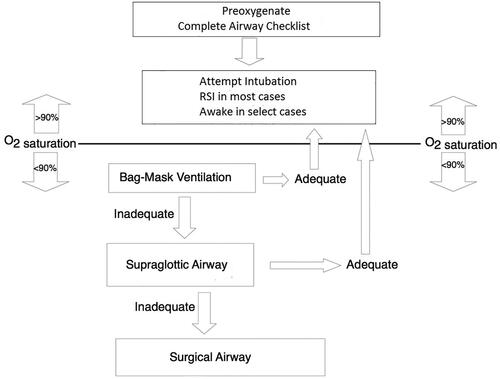

A cognitive aid, such as a simple algorithm, can also help clinicians quickly identify and commit to the need for a surgical airway (). In this context, algorithms may be valuable not only to affirm the decision to perform a surgical airway, but also to ensure that EMS clinicians have not missed other intervening airway management options. EMS clinicians should also apply parallel thinking in the management of difficult airways, preparing for a surgical airway concurrently, rather than after intubation and supraglottic airway insertion have failed.

Availability of Other Rescue Airway Techniques

A surgical airway is not a substitute for other airway management tools and techniques. It should not be the only rescue option available.

EMS agencies should not rely on surgical airway management as the sole available method for the rescue of difficult or failed airways. Historically, surgical airways were used more frequently in emergency settings due the lack of other proven devices and techniques, but now there are many well proven approaches to difficult emergency airways (Citation3, Citation9, Citation11, Citation21–32). The availability and implementation of modern emergency airway equipment, techniques and processes has significantly improved airway management and decreased the incidence of surgical airways in both the prehospital and emergency department settings (Citation9, Citation10, Citation24, Citation30–32). Some examples include the increased use of rapid sequence intubation, recognition of the importance of preoxygenation and the use of airway algorithms that include highly successful backup techniques (Citation3, Citation30, Citation33–36). In addition, implementation of a standard operating procedure, such as the routine use of video laryngoscopy (VL) and bougie, results in very high first-pass intubation success in both the emergency department and prehospital settings (Citation2, Citation3, Citation21, Citation25, Citation27, Citation35–40).

Finally, SGAs have become a standard device in emergency airway management and are used as both primary and backup devices (Citation28, Citation29, Citation41–45). Second generation SGAs can provide a better seal, may facilitate gastric emptying or tracheal intubation, and are preferred by many experts (Citation46). SGAs are critical in cases of known or unexpected difficult airways, and in the “cannot intubate and cannot facemask ventilate” scenario (Citation3, Citation26, Citation27). In two large studies, one in the operating room setting and one in the prehospital setting, an SGA was used to ventilate nearly all patients with difficult mask ventilation or failed intubation (Citation3, Citation47). In the PART trial, the majority of unsuccessful intubations were successfully rescued by placement of the laryngeal tube (Citation48).

Surgical Airway Techniques

Success of an open surgical approach using a scalpel is higher than that of percutaneous Seldinger techniques or needle-jet ventilation in the emergency setting.

When performing surgical airways, EMS clinicians experience higher success with the use of open scalpel techniques (Citation11). Also, most emergency physicians prefer an open scalpel technique when performing an emergency surgical airway. A systematic review of transtracheal jet ventilation concluded that it was associated with a high risk of device failure and barotrauma and recommended against using it in the emergency setting (Citation49). In addition, there has been debate in the anesthesiology literature about the relative merits of needle cannula (Seldinger: needle-guidewire-cannula) techniques (Citation50). However, the 4th National Audit Project of major airway complications in the United Kingdom evaluated 79 failed airways in the hospital setting that required a surgical airway. They found a 2% failure rate for open surgical airway techniques compared with a 65% failure rate for needle cannula techniques (Citation51). These findings led to the Difficult Airway Society’s strong recommendation for the use of scalpel cricothyrotomy techniques (Citation46). In addition, data from the National Emergency Airway Registry shows that in U.S. emergency departments open scalpel techniques have now completely supplanted needle cannula techniques (Citation52).

Another strong argument for the open technique is that it can negate the need for specialized equipment. One commonly taught technique, which is preferred by many emergency medicine experts, entails the use of a bougie as an aid to insertion of an endotracheal tube through the cricothyroid incision (Citation53–55).

Misidentification of the external cricoid landmarks is a common pitfall that can result in tube misplacement; therefore, making an initial vertical incision is recommended by most experts (Citation56–58). Many authors recommend placing a hook into the incision after incising the cricothyroid membrane to ensure identification and anchoring of the tract, and this is especially helpful in obese patients (Citation54, Citation55, Citation59). When using an endotracheal tube rather than a tracheostomy tube, care should be taken not to advance it too deeply, causing a mainstem intubation.

Summary

Surgical airways are a reasonable option in the prehospital setting. A surgical airway should not be viewed as a failure and should be performed without delay when indicated; however, a surgical airway should not be the only available rescue technique for difficult prehospital airways. Modern equipment, techniques, and processes improve emergency airway management and decrease the incidence of surgical airways and should be utilized by EMS clinicians who manage airways. An open surgical approach using a scalpel has a higher success rate than needle cannula techniques in the emergency setting. Regular simulation training is mandatory for clinicians who are credentialed to perform emergent surgical airways. Finally, it is important to note that there are no controlled clinical trials of emergency surgical airways, and the current recommendations are based on best available evidence and expert opinion.

References

- Jarvis JL, Wampler D, Wang HE. Association of patient age with first pass success in out-of-hospital advanced airway management. Resuscitation. 2019;141:136–43. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resuscitation.2019.06.002.

- Nicol T, Gil-Jardiné C, Jabre P, Adnet F, Ecollan P, Guihard B, Ferdynus C, Combes X. Incidence, complications, and factors associated with out-of-hospital first attempt intubation failure in adult patients: a secondary analysis of the CURASMUR Trial data. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2021;1–11.

- Combes X, Jabre P, Margenet A, Merle JC, Leroux B, Dru M, Lecarpentier E, Dhonneur G. Unanticipated difficult airway management in the prehospital emergency setting: prospective validation of an algorithm. Anesthesiology. 2011;114(1):105–10. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0b013e318201c42e.

- Fortune JB, Judkins DG, Scanzaroli D, McLeod KB, Johnson SB. Efficacy of prehospital surgical cricothyrotomy in trauma patients. J Trauma. 1997;42(5):832–6, discussion 837–8.

- Xeropotamos NS, Coats TJ, Wilson AW. Prehospital surgical airway management: 1 year's experience from the Helicopter Emergency Medical Service. Injury. 1993;24(4):222–4. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0020-1383(93)90172-3.

- Bulger EM, Copass MK, Maier RV, Larsen J, Knowles J, Jurkovich GJ. An analysis of advanced prehospital airway management. J Emerg Med. 2002;23(2):183–9. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/s0736-4679(02)00490-0.

- Salvino CK, Dries D, Gamelli R, Murphy-Macabobby M, Marshall W. Emergency cricothyroidotomy in trauma victims. J Trauma. 1993;34(4):503–5.

- Syverud SA, Borron SW, Storer DL, Hedges JR, Dronen SC, Braunstein LT, Hubbard BJ. Prehospital use of neuromuscular blocking agents in a helicopter ambulance program. Ann Emerg Med. 1988;17(3):236–42. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0196-0644(88)80114-8.

- Brown CA, 3rd, Cox K, Hurwitz S, Walls RM. 4,871 Emergency airway encounters by air medical providers: a report of the air transport emergency airway management (NEAR VI: “A-TEAM”) project. West J Emerg Med. 2014;15(2):188–93. doi:https://doi.org/10.5811/westjem.2013.11.18549.

- Wang HE, Mann NC, Mears G, Jacobson K, Yealy DM. Out-of-hospital airway management in the United States. Resuscitation. 2011;82(4):378–85. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resuscitation.2010.12.014.

- Hubble MW, Wilfong DA, Brown LH, Hertelendy A, Benner RW. A meta-analysis of prehospital airway control techniques part II: alternative airway devices and cricothyrotomy success rates. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2010;14(4):515–30. doi:https://doi.org/10.3109/10903127.2010.497903.

- High K, Brywczynski J, Han JH. Cricothyrotomy in Helicopter Emergency Medical Service Transport. Air Med J. 2018;37(1):51–3. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amj.2017.10.004.

- Brofeldt BT, Osborn ML, Sakles JC, Panacek EA. Evaluation of the rapid four-step cricothyrotomy technique: an interim report. Air Med J. 1998;17(3):127–30. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S1067-991X(98)90112-2.

- Schober P, Biesheuvel T, de Leeuw MA, Loer SA, Schwarte LA. Prehospital cricothyrotomies in a helicopter emergency medical service: analysis of 19,382 dispatches. BMC Emerg Med. 2019;19(1):12. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12873-019-0230-9.

- Mabry RL. An analysis of battlefield cricothyrotomy in Iraq and Afghanistan. J Spec Oper Med. 2012;12(1):17–23.

- Mabry RL, Edens JW, Pearse L, Kelly JF, Harke H. Fatal airway injuries during operation enduring freedom and operation Iraqi Freedom. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2010;14(2):272–7. doi:https://doi.org/10.3109/10903120903537205.

- Schauer SG, Naylor JF, Maddry JK, Beaumont DM, Cunningham CW, Blackburn MB, April MD. Prehospital airway management in Iraq and Afghanistan: a descriptive analysis. South Med J. 2018;111(12):707–13. doi:https://doi.org/10.14423/SMJ.0000000000000906.

- Joffe AM, Aziz MF, Posner KL, Duggan LV, Mincer SL, Domino KB. Management of difficult tracheal intubation: a closed claims analysis. Anesthesiology. 2019;131(4):818–29. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0000000000002815.

- Hubert V, Duwat A, Deransy R, Mahjoub Y, Dupont H. Effect of simulation training on compliance with difficult airway management algorithms, technical ability, and skills retention for emergency cricothyrotomy. Anesthesiology. 2014;120(4):999–1008. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0000000000000138.

- You-Ten KE, Bould MD, Friedman Z, Riem N, Sydor D, Boet S. Cricothyrotomy training increases adherence to the ASA difficult airway algorithm in a simulated crisis: a randomized controlled trial. Can J Anaesth. 2015;62(5):485–94. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-014-0308-5.

- Ångerman S, Kirves H, Nurmi J. A before-and-after observational study of a protocol for use of the C-MAC videolaryngoscope with a Frova introducer in pre-hospital rapid sequence intubation. Anaesthesia. 2018;73(3):348–55. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/anae.14182.

- Macke C, Gralla F, Winkelmann M, Clausen J-D, Haertle M, Krettek C, Omar M. Increased first pass success with C-MAC videolaryngoscopy in prehospital endotracheal intubation—a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Med Res. 2020;9(9):2719. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9092719.

- Louka A, Stevenson C, Jones G, Ferguson J. Intubation success after introduction of a quality assurance program using video laryngoscopy. Air Med J. 2018;37(5):303–5. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amj.2018.05.001.

- Wang HE, Donnelly JP, Barton D, Jarvis JL. Assessing advanced airway management performance in a national cohort of emergency medical services agencies. Ann Emerg Med. 2018;71(5):597–607.e3. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2017.12.012.

- Savino PB, Reichelderfer S, Mercer MP, Wang RC, Sporer KA. Direct versus video laryngoscopy for prehospital intubation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acad Emerg Med. 2017;24(8):1018–26. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/acem.13193.

- Thomsen JLD, Nørskov AK, Rosenstock CV. Supraglottic airway devices in difficult airway management: a retrospective cohort study of 658,104 general anaesthetics registered in the Danish Anaesthesia Database. Anaesthesia. 2019;74(2):151–7. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/anae.14443.

- Combes X, Jabre P, Jbeili C, Leroux B, Bastuji-Garin S, Margenet A, Adnet F, Dhonneur G. Prehospital standardization of medical airway management: incidence and risk factors of difficult airway. Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13(8):828–34. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1553-2712.2006.tb01732.x.

- McCall MJ, Reeves M, Skinner M, Ginifer C, Myles P, Dalwood N. Paramedic tracheal intubation using the intubating laryngeal mask airway. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2008;12(1):30–4. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10903120701709803.

- Timmermann A, Russo SG, Rosenblatt WH, Eich C, Barwing J, Roessler M, Graf BM. Intubating laryngeal mask airway for difficult out-of-hospital airway management: a prospective evaluation. Br J Anaesth. 2007;99(2):286–91. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/bja/aem136.

- Brown CA, 3rd, Bair AE, Pallin DJ, Walls RM, NEAR III Investigators. Techniques, success, and adverse events of emergency department adult intubations. Ann Emerg Med. 2015;65(4):363–70.e1. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2014.10.036.

- Walls RM, Brown CA, 3rd, Bair AE, Pallin DJ, NEAR II Investigators. Emergency airway management: a multi-center report of 8937 emergency department intubations. J Emerg Med. 2011;41(4):347–54. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2010.02.024.

- Sagarin MJ, Barton ED, Chng Y-M, Walls RM. Airway management by US and Canadian emergency medicine residents: a multicenter analysis of more than 6,000 endotracheal intubation attempts. Ann Emerg Med. 2005;46(4):328–36. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2005.01.009.

- Fouche PF, Stein C, Simpson P, Carlson JN, Zverinova KM, Doi SA. Flight versus ground out-of-hospital rapid sequence intubation success: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2018;22(5):578–87. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10903127.2017.1423139.

- Weingart SD, Levitan RM. Preoxygenation and prevention of desaturation during emergency airway management. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;59(3):165–75.e1. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2011.10.002.

- Driver BE, Prekker ME, Kornas RL, Cales EK, Reardon RF. Flush rate oxygen for emergency airway preoxygenation. Ann Emerg Med. 2017;69(1):1–6. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2016.06.018.

- Driver BE, Klein LR, Carlson K, Harrington J, Reardon RF, Prekker ME. Preoxygenation with flush rate oxygen: comparing the nonrebreather mask with the bag-valve mask. Ann Emerg Med. 2018;71(3):381–6. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2017.09.017.

- Driver B, Dodd K, Klein LR, Buckley R, Robinson A, McGill JW, Reardon RF, Prekker ME. The Bougie and first-pass success in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2017;70(4):473–8.e1. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2017.04.033.

- Driver BE, Prekker ME, Klein LR, Reardon RF, Miner JR, Fagerstrom ET, Cleghorn MR, McGill JW, Cole JB. Effect of use of a bougie vs endotracheal tube and stylet on first-attempt intubation success among patients with difficult airways undergoing emergency intubation: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;319(21):2179–89. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.6496.

- Sakles JC, Patanwala AE, Mosier JM, Dicken JM. Comparison of video laryngoscopy to direct laryngoscopy for intubation of patients with difficult airway characteristics in the emergency department. Intern Emerg Med. 2014;9(1):93–8. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11739-013-0995-x.

- Prekker ME, Kwok H, Shin J, Carlbom D, Grabinsky A, Rea TD. The process of prehospital airway management: challenges and solutions during paramedic endotracheal intubation. Crit Care Med. 2014;42(6):1372–8. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000000213.

- Braude D, Dixon D, Torres M, Martinez JP, O'Brien S, Bajema T. Brief research report: prehospital rapid sequence airway. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2021;25(4):583–7. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10903127.2020.1792015.

- Reardon RF, Martel M. The intubating laryngeal mask airway: suggestions for use in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2001;8(8):833–8. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1553-2712.2001.tb00217.x.

- Driver BE, Martel M, Lai T, Marko TA, Reardon RF. Use of the intubating laryngeal mask airway in the emergency department: a ten-year retrospective review. Am J Emerg Med. 2020;38(7):1367–72. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2019.11.017.

- Wang HE, Schmicker RH, Daya MR, Stephens SW, Idris AH, Carlson JN, Colella MR, Herren H, Hansen M, Richmond NJ, et al. Effect of a strategy of initial laryngeal tube insertion vs endotracheal intubation on 72-hour survival in adults with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;320(8):769–78.

- Benger JR, Kirby K, Black S, Brett SJ, Clout M, Lazaroo MJ, Nolan JP, Reeves BC, Robinson M, Scott LJ, et al. Effect of a strategy of a supraglottic airway device vs tracheal intubation during out-of-hospital cardiac arrest on functional outcome: the AIRWAYS-2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;320(8):779–91. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.11597.

- Frerk C, Mitchell VS, McNarry AF, Mendonca C, Bhagrath R, Patel A, O'Sullivan EP, Woodall NM, Ahmad I, Difficult Airway Society Intubation Guidelines Working Group. Difficult Airway Society 2015 guidelines for management of unanticipated difficult intubation in adults. Br J Anaesth. 2015;115(6):827–48. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/bja/aev371.

- Amathieu R, Combes X, Abdi W, El Housseini L, Rezzoug A, Dinca A, Slavov V, Bloc V, Dhonneur G. An algorithm for difficult airway management, modified for modern optical devices (Airtraq laryngoscope; LMA CTrachTM) a 2-year prospective validation in patients for elective abdominal, gynecologic, and thyroid surgery. J Am Soc Anesthesiol. 2011;114(1):25–33.

- Bonnette AJ, Aufderheide TP, Jarvis JL, Lesnick JA, Nichol G, Carlson JN, Hansen M, Stephens SW, Colella MR, Wang HE, et al. Bougie-assisted endotracheal intubation in the pragmatic airway resuscitation trial. Resuscitation. 2021;158:215–9. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resuscitation.2020.11.003.

- Duggan LV, Ballantyne Scott B, Law JA, Morris IR, Murphy MF, Griesdale DE. Transtracheal jet ventilation in the ‘can’t intubate can’t oxygenate’ emergency: a systematic review. Br J Anaesthesia. 2016;117(suppl_1):i28–38. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/bja/aew192.

- Cook TM. Response to: Emergency front-of-neck access: scalpel or cannula-and the parable of Buridan's ass. Br J Anaesth. 2017;119(4):840–1. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/bja/aex314.

- Katz JA, Avram MJ. 4th national audit project of the Royal College of Anaesthetists and the Difficult Airway Society: major complications of airway management in the United Kingdom: report and findings. J Am Soc Anesthesiol. 2012;116(2):496. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0b013e31823cf122.

- Brown CA, III, Fantegrossi A, Baker O, Walls RM. Reduction in cricothyrotomy rate in the emergency department: a report from the National Emergency Airway Registry (NEAR). Mediterranean Emergency Medicine Conference, Dubrovnik, Croatia; 2019.

- Braude D, Webb H, Stafford J, Stulce P, Montanez L, Kennedy G, Grimsley D. The bougie-aided cricothyrotomy. Air Med J. 2009;28(4):191–4. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amj.2009.02.001.

- Reardon R, Joing S, Hill C. Bougie-guided cricothyrotomy technique. Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17(2):225–225. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00638.x.

- Hill C, Reardon R, Joing S, Falvey D, Miner J. Cricothyrotomy technique using gum elastic bougie is faster than standard technique: a study of emergency medicine residents and medical students in an animal lab. Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17(6):666–9. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1553-2712.2010.00753.x.

- McGill J, Clinton JE, Ruiz E. Cricothyrotomy in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 1982;11(7):361–4. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/s0196-0644(82)80362-4.

- Erlandson MJ, Clinton JE, Ruiz E, Cohen J. Cricothyrotomy in the emergency department revisited. J Emerg Med. 1989;7(2):115–8. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0736-4679(89)90254-0.

- Bair AE, Chima R. The inaccuracy of using landmark techniques for cricothyroid membrane identification: a comparison of three techniques. Acad Emerg Med. 2015;22(8):908–14. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/acem.12732.

- Driver BE, Klein LR, Perlmutter MC, Reardon RF. Emergency cricothyrotomy in morbid obesity: comparing the bougie-guided and traditional techniques in a live animal model. Am J Emerg Med. 2021;50:582–6. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2021.09.015.