Abstract

Introduction

Multiple national organizations and federal agencies have promoted the development, implementation, and evaluation of evidence-based guidelines (EBGs) for prehospital care. Previous efforts have identified opportunities to improve the quality of prehospital guidelines and highlighted the value of high-quality EBGs to inform initial certification and continued competency activities for EMS personnel.

Objectives

We aimed to perform a systematic review of prehospital guidelines published from January 2018 to April 2021, evaluate guideline quality, and identify top-scoring guidelines to facilitate dissemination and educational activities for EMS personnel.

Methods

We searched the literature in Ovid Medline and EMBASE from January 2018 to April 2021, excluding guidelines identified in a prior systematic review. Publications were retained if they were relevant to prehospital care, based on organized reviews of the literature, and focused on providing recommendations for clinical care or operations. Included guidelines were appraised to identify if they met the National Academy of Medicine (NAM) criteria for high-quality guidelines and scored across the six domains of the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation (AGREE) II tool.

Results

We identified 75 guidelines addressing a variety of clinical and operational aspects of EMS medicine. About half (n = 39, 52%) addressed time/life-critical conditions and 33 (44%) contained recommendations relevant to non-clinical/operational topics. Fewer than half (n = 35, 47%) were based on systematic reviews of the literature. Nearly one-third (n = 24, 32%) met all NAM criteria for clinical practice guidelines. Only 27 (38%) guidelines scored an average of >75% across AGREE II domains, with content relevant to guideline implementation most commonly missing.

Conclusions

This interval systematic review of prehospital EBGs identified many new guidelines relevant to prehospital care; more than all guidelines reported in a prior systematic review. Our review reveals important gaps in the quality of guideline development and the content in their publications, evidenced by the low proportion of guidelines meeting NAM criteria and the scores across AGREE II domains. Efforts to increase guideline dissemination, implementation, and related education may be best focused around the highest quality guidelines identified in this review.

Introduction

Since the publication of the first National EMS Research Agenda in 2002 (Citation1), and the 2007 publication “Emergency Medical Services: At the Crossroads” by the National Academy of Medicine (NAM, formerly the Institute of Medicine) (Citation2), there have been extensive efforts to increase the science that guides EMS medicine. Evidence-based guidelines (EBGs) form the basis for translating the latest scientific research into clinical practice (Citation3). Following the recommendations of the National EMS Advisory Council (Citation4) and the Federal Interagency Committee on EMS (Citation5), the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) and the Health Resources and Services Administration have funded multiple projects to create prehospital EBGs (Citation6–10), and to evaluate their implementation (Citation11–15). Similarly, other national and international organizations have continued their ongoing work to develop and disseminate guidelines relevant to EMS medicine, including the American Heart Association (Citation16) and the European Resuscitation Council (Citation17). Continuously monitoring the release of guidelines, synthesizing recommendations, and maintaining a repository of guidance germane to EMS medicine may contribute substantially to dissemination and implementation.

The National Prehospital EBG Strategy identified a need to establish a sustainable process that promotes the development, implementation, and evaluation of prehospital EBGs (Citation18). In fulfillment of this strategy, the Prehospital Guidelines Consortium (PGC) performed a systematic review of 71 prehospital EBGs published through September 2018 (Citation19). This prior review identified important gaps in the development and reporting of prehospital guidelines, and additional work by the PGC identified specific topic areas that should be areas of focus for new guideline development or updates (Citation20). Further work performed by the PGC evaluated the existing implementation science relevant to prehospital EBGs (Citation21) and along with guideline implementation efforts across multiple states funded by NHTSA (Citation11), identified gaps in knowledge dissemination, among other aspects, limiting implementation of EBGs across EMS systems. To further improve this knowledge dissemination, multiple national organizations have recommended that an updated repository of prehospital EBGs be maintained (Citation18), an effort initiated by the PGC in 2017 (www.prehospitalguidelines.org/ebgs).

Considering the importance of evidence-based prehospital care, the National Continued Competency Program from the National Registry of Emergency Medical Technicians (NREMT) contains requirements for education on EMS research and evidence-based guidelines (Citation22). With the intent of informing related initial certification and continued competency activities for EMS personnel, and to continually update the repository of prehospital EBGs consistent with the National Prehospital EBG Strategy, NREMT and the PGC formed a memorandum of understanding in 2021 establishing a sustainable process to continuously monitor and biennially identify the latest prehospital EBGs. Subsequently, we performed an interval systematic review of prehospital EBGs to inform the EMS community about the latest guidelines published since our inaugural systematic review of prehospital EBGs. This systematic review update aimed to identify new EBGs relevant to EMS clinical medicine and non-clinical operations published since 2018. We further aimed to evaluate the quality of published prehospital guidelines and identify top-scoring guidelines that could be incorporated into initial certification and continued competency activities for EMS personnel.

Methods

Study Design & Search Strategy

We performed a systematic review and structured appraisal of published guidelines relevant to prehospital care (defined below). This work was performed by members of the PGC’s Research and Development Committees, along with co-investigators who assisted with screening records, full-text reviews, and manuscript preparation. Our systematic review involved a research librarian who searched Ovid MEDLINE and EMBASE for articles published from inception to April 30, 2021, excluding EMBASE conference abstracts. The keywords and search strategy are described in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2. Search terms were developed using the search terms used in 2018, with the addition of “abstract search (ab.)” for the EMS search string and the search term “first responder*.ti,ab,kw.” Additionally, we manually searched bibliographies and position statements published by the National Association of EMS Physicians during the search period for additional articles that met our screening criteria for prehospital EBGs. Records retained in these searches were screened for topical relevance and full-text articles were examined in detail if they were published after January 1, 2018, and not included in the prior systematic review (Citation19). Non-English language publications were excluded from the initial search and duplicates were subsequently excluded.

Guideline Selection and Categorization

Two investigators (RMH and BTP) independently screened records (titles and abstracts) that met three inclusion criteria for our definition of a “prehospital evidence-based guideline”: the record addresses a clinical or operational topic relevant to prehospital care or EMS medicine (Citation23), provides recommendations/guidance for clinical care or operations, and describes performance of an organized review of the literature as a basis for forming those recommendations (e.g., systematic review, narrative review, rapid review, scoping review, or simply “literature review”). We used the first 50 records/articles from the searches to train co-investigators how to systematically apply review criteria during the screening process as described by Ng et al. (Citation24). In terms of EBG content and scope, a guideline was included/retained if at least one section of the guideline was determined to be relevant to prehospital care, even if the bulk or rest of the guideline document was related to hospital-based care. We also evaluated position statements from professional organizations using the above-mentioned criteria.

Initial screening was conducted using DistillerSR (Evidence Partners, Ontario, Canada) and articles were retained if they met all three criteria. Conflicts were resolved by discussion of two senior investigators (CMG and PDP). Retained articles and articles found by bibliography and related searches underwent full-text review with adjudication of conflicts by discussion. The final decision for including or excluding a guideline document was based on consensus of five co-investigators (KMB, REC, CMG, PDP, and CTR).

We then used the American Board of Emergency Medicine 2019 Core Content of EMS Medicine to categorize each guideline by content area (Citation23). Guidelines addressing multiple clinical or operational topics were categorized into multiple topic areas where appropriate and based on investigator judgment.

Guideline Appraisal

We appraised the evidence evaluation, development, and reporting of each guideline using the National Academy of Medicine (NAM) criteria for clinical practice guidelines and the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation (AGREE) II tool, as previously described (Citation19). Tables describing the qualitative NAM criteria for clinical practice guidelines and the six AGREE II guideline domains can be found in this prior publication.

The NAM criteria were previously adapted based on criteria for clinical practice guidelines established for the National Guidelines Clearinghouse by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) (Citation25). These criteria were adapted from the NAM publication “Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust” (Citation26). Guidelines were assessed on all NAM criteria, as summarized in . Appraisals were determined by independent full-text review of three co-investigators (KMB, REC, and CTR), with review of disagreements and final consensus of four investigators (KMB, REC, CMG, and CTR). Supplementary content that was referenced or linked within the cited guideline as an evidentiary basis for the guideline’s recommendations (e.g., a separate systematic review of the literature that directly linked to the guideline’s recommendations) was considered as part of the guideline for NAM scoring. All retained guidelines met the additional NAM criteria of being published in English, available to the public (for free or for a fee), and being the most recent versions.

Table 1. Criteria for clinical practice guidelines assessment.

Consistent with our prior systematic review, we modified the NAM criteria to include operational guidelines not otherwise described as “clinical practice guidelines,” such as the guideline by Schwellnus et al. describing methods of data recording and reporting during mass gathering sports events that are relevant to EMS quality improvement and research (Citation27). A guideline was identified as “produced under the auspices of an association or similar entity”’ if it was described as created, sponsored, supported, or endorsed by one or more medical specialty associations; relevant professional societies, public or private organizations; government agencies at the federal, state, or local level; or health care organizations or plans (Citation25). A guideline was determined to be based on a systematic review if explicitly performed for the guideline and stated as such, or if recommendations were explicitly based on a separate systematic review that was tied to the individual recommendations, such as in the guideline by Williams et al. (Citation10). If not explicitly stated in the guideline document, we considered a systematic review to have been performed if all of its key elements (search strategy, study selection, synthesis of evidence, and summary of evidence synthesis) were reported and this evidence review informed the recommendations. When a guideline’s literature search identified a relevant systematic review but did not form the basis for the guideline’s recommendations, we did not consider this criterion fulfilled (e.g., guideline by Ahmed et al.) (Citation28). In adjudicating the “presence of a synthesis of evidence from selected studies” (e.g., a detailed description or evidence tables) or a “summary of evidence synthesis” (e.g., a descriptive aggregate summary of studies or summary table), we considered these criteria fulfilled if they were present for at least one of the recommendations in the guideline, even if other recommendations in the guideline were consensus-based. Similarly, we considered a guideline to be “informed by a systematic review of the literature” if any of the recommendations were informed by a systematic review, even if other recommendations were included based on expert opinion, such as the guideline by Incagnoli et al. (Citation29).

Each guideline was appraised further by the independent review of three investigators (KMB, REC, and CTR) across the six AGREE II domains summarized in . The AGREE II appraisal tool consists of 23 domain items, and individual appraisals were performed using the My AGREE PLUS platform (AGREE Collaboration, available at www.agreetrust.org/resource-center/agree-plus) (Citation30, Citation31). We combined individual appraisals for each domain by averaging the reviewers’ scores for each item within domains and displaying this as a proportion of the maximum score available for each domain. We then averaged these totals across all domains to provide an overall proportional score for each guideline. For Domain 6 (Editorial Independence), if no technical expert panel or recommendations-developing group was specified, we assumed the recommendations were developed by the listed authors, and we determined “reporting of conflicts relevant to the guideline” based on the reported conflicts of the authors.

Table 2. Appraisal of guidelines for research and evaluation (AGREE) II assessment.

Reporting

Findings are presented in accordance with the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA; Supplementary Table 3).

Results

Guideline Search

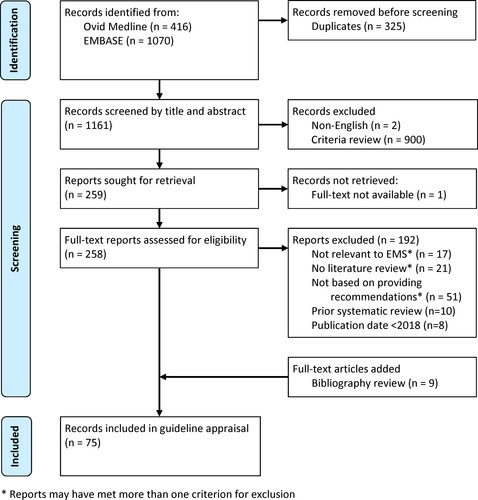

Our search strategy yielded 1,161 articles after removal of duplicate records (). Of these citations, we excluded two non-English records and 900 based on inclusion/exclusion criteria through screening of titles and abstracts, with substantial inter-rater agreement (kappa = 0.65). Of the remaining citations, 192 were excluded by full-text review for reasons in . An additional nine articles meeting review criteria were added based on bibliography review and search of organizational position statements that met the inclusion criteria. Ultimately, 75 guidelines were included for appraisal (Citation10, Citation27–29, Citation32–102).

Guideline Topics

Almost all appraised guidelines (n = 73, 97%) addressed at least one clinical aspect within the classification of the core content of EMS medicine (Supplementary Table 4) (Citation23). There were many guidelines addressing multiple topics, including a guideline by Zideman et al. that provided recommendations related to 20 PICO topics, which were categorized into 12 core content areas of EMS medicine (Citation101). The most frequently addressed components of EMS medicine among included guidelines were time/life-critical conditions (n = 39, 52%), injury (n = 26, 35%), medical emergencies (n = 26, 35%), and special clinical considerations (n = 26, 35%). Few guidelines were specific to pediatric prehospital care (n = 16, 21%), and fewer than half addressed non-clinical aspects of EMS medicine (n = 33, 44%).

Guideline Appraisal

Results of the guidelines appraisal based on NAM criteria and AGREE II scoring are summarized in and , respectively. Fewer than a third of prehospital guidelines (n = 24, 32%) contained all NAM criteria for high-quality guidelines (). Most guidelines contained assessments of benefits and harms (n = 73, 97%), had systematically developed recommendations (n = 70, 93%), and were developed or endorsed by one or more associations or professional organizations (n = 68, 91%). Fewer than half (n = 35, 47%) reported performing or contained the key elements of a systematic review of the literature. Only 31 (41%) reported explicit synthesis of the evidence leading to recommendations, which was the most commonly missing NAM criterion for clinical guidelines.

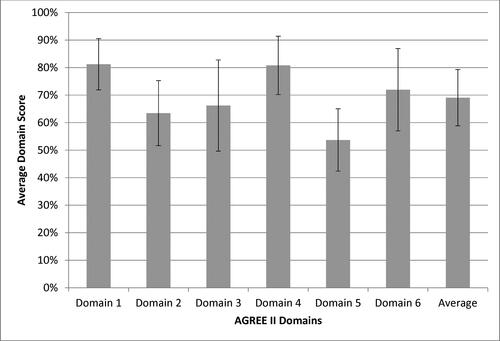

Most guidelines (n = 46, 65%) had average domain scores between 50-75% (, ). Only 27 (38%) guidelines scored above 75%. Across prehospital guidelines, the highest domain scores (% of available points ± SD) were found for Domain 1 (Scope and Purpose) and Domain 4 (Clarity of Presentation), which scored at 81% (±9%) and 81% (±11%), respectively. Domain 5 (Applicability) scored the lowest at 54% (±11%). The average score across all domains was 69% (±10%). Averaged individual domain item scores are provided in Supplementary Table 5.

Figure 2. Average scores across AGREE II domains (average of three appraisers ± standard deviation).

Domain 1 – Scope and Purpose (description of objectives, questions, and population)

Domain 2 – Stakeholder Involvement (description of input gained from stakeholders including target population)

Domain 3 – Rigor of Development (description of methodology of evidence evaluation and development of recommendations)

Domain 4 – Clarity of Presentation (clarity of recommendations including options for management)

Domain 5 – Applicability (description of implementation and evaluation)

Domain 6 – Editorial Independence (description of potential conflicts from funding body or guideline development group members)

Discussion

Our systematic review identified 75 EBGs germane to prehospital emergency care published between January 1, 2018, and April 30, 2021, after or otherwise not included in the prior systematic review completed in September 2018 (Citation19). Our findings identified more EBGs than the total number of guidelines reported in the prior systematic review (n = 71) (Citation19), demonstrating a high level of interest and substantial effort toward creating and updating EBGs for prehospital care. Almost all guidelines (97%) provided recommendations for clinical aspects of EMS medicine with only 33 guidelines (44%) focusing on operations. The high number of prehospital EBGs identified in this interval suggests an ongoing need to periodically identify and evaluate the quality of new guidelines to support the dissemination and implementation of new evidence-based recommendations, such as on a biennial basis.

Similar to the prior systematic review of prehospital EBGs (Citation19), we found specific deficiencies in the methodology for developing or reporting guidelines based on NAM criteria. Fewer than one third contained all elements of high-quality guidelines. Importantly, many prehospital EBGs are based on consensus recommendations and provide only limited descriptions of their literature reviews or how published scientific evidence was used to inform specific recommendations. Fewer than half stated that recommendations were based on systematic reviews of the literature or reported all the key elements of a systematic review. Commonly missed systematic review elements included search strategy and study selection, which are essential to understanding what literature was retained and being able to reproduce the review’s findings. Similarly, many guidelines did not meet the NAM reporting threshold for a “synthesis of evidence” describing individual studies (e.g., a detailed narrative description or evidence tables) or a “summary of the evidence synthesis” that aggregates individual studies and relates the evidence to the recommendations (e.g., a descriptive summary of included studies in narrative form or as summary tables). These elements are needed for readers to understand the basis and strength of recommendations and to relate the evidence supporting specific recommendations to their own EMS systems.

The AGREE II Domain 1 (Scope and Purpose) and Domain 4 (Clarity of Presentation) continued to score highly in this review compared to the previous review (Citation19), demonstrating this is a continued strength of EMS guidelines. On the other hand, aggregate scores across Domain 2 (Stakeholder Involvement), Domain 3 (Rigor of Development), and Domain 6 (Editorial Independence) made notable improvements yet continue to be opportunities for improvement in many guidelines. In domains that had higher aggregate scores overall compared with the prior systematic review, specific items that continued to score poorly were the “incorporation of statements related to the target population’s preferences and views” (Domain 2, Item 5), and a “specific statement describing the procedure and timeline for updating the guideline” (Domain 3, Item 14) (Citation30).

A minority of guidelines (n = 27, 38%) scored above 75% across AGREE II domains, though this compared favorably with the prior systematic review in which only 13% had scores in the top quartile. While better, this demonstrates a continued opportunity to improve the performance and reporting of key elements of guideline development that informs the EMS community. Specifically, guidelines continued to score poorly in Domain 5 (Applicability). This domain relates largely to how well the guideline addresses the ability to implement the guideline. To score highly, guidelines must describe facilitators and barriers to application of the guideline, provide implementation advice or tools, describe resource implications, and provide monitoring or auditing criteria. This finding further emphasizes the need to strengthen implementation science for prehospital EBGs, as identified in a prior systematic review of how prehospital EBGs are implemented in EMS systems (Citation21). The low score of Domain 5 across guidelines was largely driven by a lack of monitoring or auditing criteria being included in guidelines. Examples of such content provided in the AGREE II checklist include: “Criteria to assess guideline implementation or adherence to recommendations, criteria for assessing impact of implementing the recommendations, advice on the frequency and interval of measurement, and operational definitions of how the criteria should be measured” (Citation30). EBGs can improve in this domain by incorporating specific content to facilitate guideline implementation, and performance metrics that can be used to determine how well a guideline was implemented and if it was effective at achieving the intended goals. An example of such implementation tools can be found for the fatigue in EMS guideline by Patterson et al. (Citation9, Citation103).

Our review identified additional valuable publications that did not meet our criteria for prehospital EBGs and were not retained in this review. Publications with recommendations that merely cited peer-reviewed literature but did not report organized searches of the literature were not retained. For example, the position statement by Fischer et al. did not report performing or being based on a specific organized review of the literature in developing its recommendations, but provided citations of relevant publications (Citation104). Other articles citing relevant studies but not describing organized reviews or synthesis of the literature were also excluded (Citation105–107). A guideline by Koenig et al. that reported performing a literature search but found no relevant published studies, with recommendations based solely on consensus opinion, was similarly excluded (Citation108). On the other hand, we included the reviews and related position statements by Cicero et al. and Lyng et al. because they involved new organized literature reviews to inform practice recommendations contained within the position statements (Citation42, Citation67). These examples highlight the challenge of defining an “evidence-based guideline” that differentiates such guidelines from review articles, editorials, or consensus statements informed by, but not based on, an organized review of the literature.

The content of prehospital EBGs published between 2018 and 2021 continues to be focused on clinical aspects of EMS medicine (Supplementary Table 4). More than half of guidelines had to do with time/life-critical conditions, largely represented by guidelines relevant to cardiopulmonary resuscitation, such as updated guidelines from the American Heart Association (Citation33, Citation36, Citation40, Citation48–50, Citation52, Citation63, Citation80–82, Citation84) and the European Resuscitation Council (Citation54, Citation55, Citation65, Citation68, Citation72, Citation77, Citation78, Citation83, Citation89, Citation91, Citation96, Citation101). Fewer than half of guidelines we found (n = 33, 44%) involved operational topics, such as medical oversight, quality management, research, and special operations, though this was three times as many as were found in the prior review (n = 11, 15%) (Citation19). A variety of articles relevant to COVID-19 were screened, but ultimately not retained as there was very limited research to be reviewed early in the pandemic, thus not meeting inclusion criteria. We also identified new guidelines that at least in part addressed content relevant to operational topics and questions, including system finance (Citation67); public health (Citation36, Citation59, Citation78, Citation89); data collection, management, and analysis (Citation27, Citation36, Citation54); epidemiology (Citation54); and a variety of previously unaddressed special operations topics (Citation27, Citation38, Citation44, Citation59, Citation61, Citation79, Citation87, Citation93, Citation94). Across both systematic reviews, we continue to not find prehospital EBGs addressing several core content areas of EMS medicine including assault/abuse, renal emergencies, dermatology, behavioral emergencies, geriatrics, or bariatric issues.

While all gaps in knowledge represent areas of potential focus for future guideline development, members of the PGC collaborated on a gap analysis of prehospital guidelines that identified top areas for both clinical and operational prehospital guideline development, informed by the prior systematic review (Citation20). The prioritized list of clinical EBG gaps included airway management, care of the pediatric patient, and management of behavioral emergencies, while operational EBG gaps included defining and measuring the effects of EMS care on patient outcomes, practitioner wellness, and practitioner safety. This most recent effort, which includes the time during which this gap analysis was completed, reveals seven new guidelines relevant to airway compromise and respiratory failure and 16 guidelines focusing on pediatric patients, demonstrating these are indeed focus areas for clinical guideline development within the EMS community. A new systematic review of airway management by the Evidence-based Practice Center of AHRQ supported by NHTSA is anticipated to yield a new evidence-based guideline on airway management for EMS (Citation109). Similarly, six new guidelines were identified relevant to EMS personnel health and wellness. On the other hand, our review identified no additional guidelines relevant to behavioral emergencies or the other high-priority areas identified in the EBG gap analysis. These findings can be used to inform the EMS community of priority areas where new guidelines have been developed and specific topics that should continue to be areas of focus for future guideline development.

Limitations

There are several limitations associated with this systematic review. Our search criteria, though refined from the prior review, missed some guidelines found later in bibliography searches. Including searches of bibliographies is a strength of this systematic review. Other guidelines may have been missed, particularly those in other medical disciplines whose titles and abstracts did not indicate any potential relevance to prehospital care. On the other hand, the agreement between screeners was substantial (kappa = 0.65) and improved from the prior review (kappa = 0.35), identifying improvements in knowledge and training within our group for identifying prehospital EBGs. Additionally, the total number of guidelines found in the 3-year span of this review compared to prior work suggests that our search methods were robust. Members of our investigative team performing guideline appraisals identified specific challenges in appraising guidelines based on the NAM criteria or AGREE II domains. Specifically, they reported that quality assessments of guidelines were often subject to reviewer interpretation. Even use of standardized criteria such as that promoted by NAM and AHRQ, or the individual items and domains of the validated AGREE II scoring tool are subject to reviewer variability. This variability may result in differing judgements and assessments of guidelines by other investigators. Criteria were particularly challenging to identify in guideline publications based on separate systematic reviews of the literature and especially where key elements were reported in supplementary material. Overall, the structured individual review, training of co-investigators, and consensus approach described herein mitigated reviewer discrepancies, though adjudication of NAM criteria by consensus review was required for many publications. Furthermore, subjectivity to the AGREE II scoring mechanism was mitigated by using an average of three independent reviewers for each individual item (following recommendations from the AGREE Collaborative, which is to have two to four reviewers rate each guideline) (Citation31), and these were performed by reviewers with extensive experience in systematic reviews and prehospital guideline development.

Conclusions

This updated systematic review of EBGs identified many prehospital guidelines published between 2018 and 2021. We identified numerous guidelines that could inform the EMS community of evidence-based approaches to clinical care and operations. We highlight guideline quality and discuss gaps that remain for guidelines germane to prehospital care. The highest quality guidelines identified may benefit the EMS community with focused efforts supporting dissemination, implementation, and evaluation. To optimize their quality, future prehospital guidelines should ensure they incorporate and report existing criteria for high-quality guidelines, such as those promoted by NAM and by the AGREE II checklist.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (482.3 KB)Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Rose Turner from the Health Sciences Library System, University of Pittsburgh, for her assistance in completion of the systematic literature search.

Disclosure Statement

This work was supported through a cooperative agreement between the National Registry of EMTs (NREMT) and the Prehospital Guidelines Consortium, with funding from NREMT. KMB, REC, BTP, CTR, and PDP received support through this cooperative agreement. RMH was supported through an internal grant from the University of Cincinnati Department of Emergency Medicine. CMG declares no financial support for this work. Separate from this work, CMG reports funding from CDC, NIOSH, NIH, US Department of Defense, and Kaiser Foundation Hospitals. PDP reports funding from CDC, NIOSH, NIH, and the ZOLL foundation. REC reports funding from NIH.

References

- Sayre MR, White LJ, Brown LH, McHenry SD. National EMS Research Agenda. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2002;6(3 Suppl):S1–S43.

- Institute of Medicine (U.S.). Committee on the Future of Emergency Care in the United States Health System. Emergency medical services at the crossroads. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2007.

- Wright JL. Evidence-based guidelines for prehospital practice: a process whose time has come. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2014;18(Suppl 1):1–2.

- National Emergency Medical Services Advisory Council. National Emergency Medical Services Advisory Council Summary Report [2010-2012]. Report No. DOT HS 811 705. Washington, DC: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, 2013. [accessed Apr. 21, 2022]. Available from: www.nhtsa.gov/staticfiles/nti/pdf/811705.pdf.

- Federal Interagency Committee on EMS. FICEMS Strategic Plan. Report No. DOT HA 811 990. Washington, DC: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration; 2014. [accessed Apr. 21, 2022]. Available from: http://www.ems.gov/ficems/plan.htm.

- Shah MI, Macias CG, Dayan PS, Weik TS, Brown KM, Fuchs SM, Fallat ME, Wright JL, Lang ES. An evidence-based guideline for pediatric prehospital seizure management using GRADE methodology. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2014;18(Suppl 1):15–24. doi:10.3109/10903127.2013.844874

- Gausche-Hill M, Brown KM, Oliver ZJ, Sasson C, Dayan PS, Eschmann NM, Weik TS, Lawner BJ, Sahni R, Falck-Ytter Y, et al. An evidence-based guideline for prehospital analgesia in trauma. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2014;18(Suppl 1):25–34. doi:10.3109/10903127.2013.844873

- Thomas SH, Brown KM, Oliver ZJ, Spaite DW, Lawner BJ, Sahni R, Weik TS, Falck-Ytter Y, Wright JL, Lang ES. An evidence-based guideline for the air medical transportation of prehospital trauma patients. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2014;18(Suppl 1):35–44. doi:10.3109/10903127.2013.844872

- Patterson PD, Higgins JS, Van Dongen HPA, Buysse DJ, Thackery RW, Kupas DF, Becker DS, Dean BE, Lindbeck GH, Guyette FX, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for fatigue risk management in emergency medical services. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2018;22(Suppl 1):89–101. doi:10.1080/10903127.2017.1376137

- Williams K, Lang ES, Panchal AR, Gasper JJ, Taillac P, Gouda J, Lyng JW, Goodloe JM, Hedges M. Evidence-based guidelines for EMS administration of naloxone. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2019;23(6):749–63.

- Adelgais KM, Sholl JM, Alter R, Gurley KL, Broadwater-Hollifield C, Taillac P. Challenges in statewide implementation of a prehospital evidence-based guideline: an assessment of barriers and enablers in five states. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2019;23(2):167–78. doi:10.1080/10903127.2018.1495284

- Brown KM, Hirshon JM, Alcorta R, Weik TS, Lawner B, Ho S, Wright JL. The implementation and evaluation of an evidence-based statewide prehospital pain management protocol developed using the national prehospital evidence-based guideline model process for emergency medical services. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2014;18(Suppl 1):45–51. doi:10.3109/10903127.2013.831510

- Nassif A, Ostermayer DG, Hoang KB, Claiborne MK, Camp EA, Shah MI. Implementation of a prehospital protocol change for asthmatic children. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2018;22(4):457–65. doi:10.1080/10903127.2017.1408727

- Browne LR, Shah MI, Studnek JR, Ostermayer DG, Reynolds S, Guse CE, Brousseau DC, Lerner EB. Multicenter evaluation of prehospital opioid pain management in injured children. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2016;20(6):759–67. doi:10.1080/10903127.2016.1194931

- Carey JM, Studnek JR, Browne LR, Ostermayer DG, Grawey T, Schroter S, Lerner EB, Shah MI. Paramedic-identified enablers of and barriers to pediatric seizure management: a multicenter, qualitative study. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2019;23(6):870–81. doi:10.1080/10903127.2019.1595234

- Merchant RM, Topjian AA, Panchal AR, Cheng A, Aziz K, Berg KM, Lavonas EJ, Magid DJ, Adult B, Advanced Life Support PB, et al. Part 1: executive summary: 2020 American Heart Association guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation. 2020;142(16_suppl_2):S337–S357. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000918

- Perkins GD, Graesner JT, Semeraro F, Olasveengen T, Soar J, Lott C, Van de Voorde P, Madar J, Zideman D, Mentzelopoulos S, et al. European resuscitation council guidelines 2021: executive summary. Resuscitation. 2021;161:1–60. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2021.02.003

- Martin-Gill C, Gaither JB, Bigham BL, Myers JB, Kupas DF, Spaite DW. National Prehospital evidence-based guidelines strategy: a summary for EMS stakeholders. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2016;20(2):175–83. doi:10.3109/10903127.2015.1102995

- Turner S, Lang ES, Brown K, Franke J, Workun-Hill M, Jackson C, Roberts L, Leyton C, Bulger EM, Censullo EM, et al. Systematic review of evidence-based guidelines for prehospital care. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2021;25(2):221–34. doi:10.1080/10903127.2020.1754978

- Richards CT, Fishe JN, Cash RE, Rivard MK, Brown KM, Martin-Gill C, Panchal AR. Priorities for prehospital evidence-based guideline development: a modified Delphi analysis. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2022;26(2):286–304. doi:10.1080/10903127.2021.2005194

- Fishe JN, Crowe RP, Cash RE, Nudell NG, Martin-Gill C, Richards CT. Implementing prehospital evidence-based guidelines: a systematic literature review. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2018;22(4):511–9.

- National Continued Competency Program. National Registry of Emergency Medical Technicians. 2016. [accessed May 18, 2022]. Available from: https://www.nremt.org/Document/nccp.

- Delbridge TR, Dyer S, Goodloe JM, Mosesso VN, Perina DG, Sahni R, Pons PT, Rinnert KJ, Isakov AP, Kupas DF, et al. The 2019 core content of emergency medical services medicine. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2020;24(1):32–45. doi:10.1080/10903127.2019.1603560

- Ng L, Pitt V, Huckvale K, Clavisi O, Turner T, Gruen R, Elliott JH. Title and Abstract Screening and Evaluation in Systematic Reviews (TASER): a pilot randomised controlled trial of title and abstract screening by medical students. Syst Rev. 2014;3:121. doi:10.1186/2046-4053-3-121

- National Guideline Clearinghouse. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2019. [accessed 2022 Apr 21]. Available from: https://www.ahrq.gov/gam/index.html.

- Institute of Medicine (US). Committee on Standards for Developing Trustworthy Clinical Practice Guidelines, Graham R, Mancher M, Miller Wolman, D. Clinical practice guidelines we can trust. 2011.

- Schwellnus M, Kipps C, Roberts WO, Drezner JA, D'Hemecourt P, Troyanos C, Janse van Rensburg DC, Killops J, Borresen J, Harrast M, et al. Medical encounters (including injury and illness) at mass community-based endurance sports events: an international consensus statement on definitions and methods of data recording and reporting. Br J Sports Med. 2019;53(17):1048–55. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2018-100092

- Ahmed N, Audebert H, Turc G, Cordonnier C, Christensen H, Sacco S, Sandset EC, Ntaios G, Charidimou A, Toni D, et al. Consensus statements and recommendations from the ESO-Karolinska Stroke Update Conference, Stockholm 11–13 November 2018. Eur Stroke J. 2019;4(4):307–17. doi:10.1177/2396987319863606

- Incagnoli P, Puidupin A, Ausset S, Beregi JP, Bessereau J, Bobbia X, Brun J, Brunel E, Buleon C, Choukroun J, et al. Early management of severe pelvic injury (first 24 hours). Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med. 2019;38(2):199–207. doi:10.1016/j.accpm.2018.12.003

- Brouwers MC, Kerkvliet K, Spithoff K, Consortium ANS. The AGREE Reporting Checklist: a tool to improve reporting of clinical practice guidelines. BMJ. 2016;352:i1152. doi:10.1136/bmj.i1152

- Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, Fervers B, Graham ID, Grimshaw J, Hanna SE, et al. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ. 2010;182(18):E839–E842. doi:10.1503/cmaj.090449

- Adeoye O, Nystrom KV, Yavagal DR, Luciano J, Nogueira RG, Zorowitz RD, Khalessi AA, Bushnell C, Barsan WG, Panagos P, et al. Recommendations for the establishment of stroke systems of care: a 2019 update. Stroke. 2019;50(7):e187–e210. doi:10.1161/STR.0000000000000173

- Atkins DL, de Caen AR, Berger S, Samson RA, Schexnayder SM, Joyner BL, Jr., Bigham BL, Niles DE, Duff JP, Hunt EA, et al. 2017 American Heart Association focused update on pediatric basic life support and cardiopulmonary resuscitation quality: an update to the American Heart Association guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation. 2018;137(1):e1–e6. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000540

- Babl FE, Tavender E, Ballard DW, Borland ML, Oakley E, Cotterell E, Halkidis L, Goergen S, Davis GA, Perry D, et al. Australian and New Zealand guideline for mild to moderate head injuries in children. Emerg Med Australas. 2021;33(2):214–31. doi:10.1111/1742-6723.13722

- Bennett BL, Hew-Butler T, Rosner MH, Myers T, Lipman GS. Wilderness medical society clinical practice guidelines for the management of exercise-associated hyponatremia: 2019 update. Wilderness Environ Med. 2020;31(1):50–62. doi:10.1016/j.wem.2019.11.003

- Berg KM, Cheng A, Panchal AR, Topjian AA, Aziz K, Bhanji F, Bigham BL, Hirsch KG, Hoover AV, Kurz MC, et al. Part 7: systems of care: 2020 American Heart Association guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation. 2020;142(16_suppl_2):S580–S604. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000899

- Best RR, Harris BHL, Walsh JL, Manfield T. Pediatric drowning: a standard operating procedure to aid the prehospital management of pediatric cardiac arrest resulting from submersion. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2020;36(3):143–6.

- Blancher M, Albasini F, Elsensohn F, Zafren K, Holzl N, McLaughlin K, Wheeler AR, 3rd, Roy S, Brugger H, Greene M, et al. Management of multi-casualty incidents in mountain rescue: evidence-based guidelines of the international commission for mountain emergency medicine (ICAR MEDCOM). High Alt Med Biol. 2018;19(2):131–40. doi:10.1089/ham.2017.0143

- Bouzat P, Valdenaire G, Gauss T, Charbit J, Arvieux C, Balandraud P, Bobbia X, David JS, Frandon J, Garrigue D, et al. Early management of severe abdominal trauma. Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med. 2020;39(2):269–77.

- Charlton NP, Pellegrino JL, Kule A, Slater TM, Epstein JL, Flores GE, Goolsby CA, Orkin AM, Singletary EM, Swain JM. 2019 American Heart Association and American Red Cross focused update for first aid: presyncope: an update to the american heart association and american red cross guidelines for first aid. Circulation. 2019;140(24):e931–e8. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000730

- Cheng T, Farah J, Aldridge N, Tamir S, Donofrio-Odmann JJ. Pediatric respiratory distress: California out-of-hospital protocols and evidence-based recommendations. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. 2020;1(5):955–64.

- Cicero MX, Adelgais K, Hoyle JD, Lyng JW, Harris M, Moore B, Gausche-Hill M. Medication dosing safety for pediatric patients: recognizing gaps, safety threats, and best practices in the emergency medical services setting. A position statement and resource document from NAEMSP. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2021;25(2):294–306.

- Cook TM, El-Boghdadly K, McGuire B, McNarry AF, Patel A, Higgs A. Consensus guidelines for managing the airway in patients with COVID-19: Guidelines from the Difficult Airway Society, the Association of Anaesthetists the Intensive Care Society, the Faculty of Intensive Care Medicine and the Royal College of Anaesthetists. Anaesthesia. 2020;75(6):785–99. doi:10.1111/anae.15054

- Cottey L, Jefferys S, Woolley T, Smith JE. Use of supplemental oxygen in emergency patients: a systematic review and recommendations for military clinical practice. J R Army Med Corps. 2019;165(6):416–20.

- Craig S, Cubitt M, Jaison A, Troupakis S, Hood N, Fong C, Bilgrami A, Leman P, Ascencio-Lane JC, Nagaraj G, et al. Management of adult cardiac arrest in the COVID-19 era: consensus statement from the Australasian College for Emergency Medicine. Med J Aust. 2020;213(3):126–33.

- Doherty C, Neal R, English C, Cooke J, Atkinson D, Bates L, Moore J, Monks S, Bowler M, Bruce IA, et al. Multidisciplinary guidelines for the management of paediatric tracheostomy emergencies. Anaesthesia. 2018;73(11):1400–17.

- Dow J, Giesbrecht GG, Danzl DF, Brugger H, Sagalyn EB, Walpoth B, Auerbach PS, McIntosh SE, Nemethy M, McDevitt M, et al. Wilderness medical society clinical practice guidelines for the out-of-hospital evaluation and treatment of accidental hypothermia: 2019 update. Wilderness Environ Med. 2019;30(4S):S47–S69.

- Duff JP, Topjian A, Berg MD, Chan M, Haskell SE, Joyner BL, Jr., Lasa JJ, Ley SJ, Raymond TT, Sutton RM, et al. 2018 American Heart Association focused update on pediatric advanced life support: an update to the american heart association guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation. 2018;138(23):e731–e9. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000612

- Duff JP, Topjian AA, Berg MD, Chan M, Haskell SE, Joyner BL, Jr., Lasa JJ, Ley SJ, Raymond TT, Sutton RM, et al. 2019 American Heart Association focused update on pediatric advanced life support: an update to the american heart association guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation. 2019;140(24):e904–e14.

- Duff JP, Topjian AA, Berg MD, Chan M, Haskell SE, Joyner BL, Jr., Lasa JJ, Ley SJ, Raymond TT, Sutton RM, et al. 2019 American Heart Association focused update on pediatric basic life support: an update to the american heart association guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation. 2019;140(24):e915–e21. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000736

- Eggleston W, Palmer R, Dube PA, Thornton S, Stolbach A, Calello DP, Marraffa JM. Loperamide toxicity: recommendations for patient monitoring and management. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2020;58(5):355–9. doi:10.1080/15563650.2019.1681443

- Escobedo MB, Aziz K, Kapadia VS, Lee HC, Niermeyer S, Schmolzer GM, Szyld E, Weiner GM, Wyckoff MH, Yamada NK, et al. 2019 American Heart Association focused update on neonatal resuscitation: an update to the american heart association guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation. 2019;140(24):e922–e30. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000729

- Gowens P, Aitken-Fell P, Broughton W, Harris L, Williams J, Younger P, Bywater D, Crookston C, Curatolo L, Edwards T, et al. Consensus statement: a framework for safe and effective intubation by paramedics. Br Paramed J. 2018;3(1):23–7. doi:10.29045/14784726.2018.06.3.1.23

- Grasner JT, Herlitz J, Tjelmeland IBM, Wnent J, Masterson S, Lilja G, Bein B, Bottiger BW, Rosell-Ortiz F, Nolan JP, et al. European resuscitation council guidelines 2021: epidemiology of cardiac arrest in Europe. Resuscitation. 2021;161:61–79. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2021.02.007

- Greif R, Lockey A, Breckwoldt J, Carmona F, Conaghan P, Kuzovlev A, Pflanzl-Knizacek L, Sari F, Shammet S, Scapigliati A, et al. European resuscitation council guidelines 2021: education for resuscitation. Resuscitation. 2021;161:388–407. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2021.02.016

- Hachimi-Idrissi S, Coffey F, Hautz WE, Leach R, Sauter TC, Sforzi I, Dobias V. Approaching acute pain in emergency settings: European Society for Emergency Medicine (EUSEM) guidelines-part 1: assessment. Intern Emerg Med. 2020;15(7):1125–39. doi:10.1007/s11739-020-02477-y

- Hachimi-Idrissi S, Dobias V, Hautz WE, Leach R, Sauter TC, Sforzi I, Coffey F. Approaching acute pain in emergency settings; European Society for Emergency Medicine (EUSEM) guidelines-part 2: management and recommendations. Intern Emerg Med. 2020;15(7):1141–55. doi:10.1007/s11739-020-02411-2

- Hart J, Tracy R, Johnston M, Brown S, Stephenson C, Kegg J, Waymack J. Recommendations for prehospital airway management in patients with suspected COVID-19 infection. West J Emerg Med. 2020;21(4):809–12.

- Hodgson L, Phillips G, Saggers RT, Sharma S, Papadakis M, Readhead C, Cowie CM, Massey A, Weiler R, Mathema P, et al. Medical care and first aid: an interassociation consensus framework for organised non-elite sport during the COVID-19 pandemic. Br J Sports Med. 2022;56(2):68–79. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2020-103622

- Hodroge SS, Glenn M, Breyre A, Lee B, Aldridge NR, Sporer KA, Koenig KL, Gausche-Hill M, Salvucci AA, Rudnick EM, et al. Adult patients with respiratory distress: current evidence-based recommendations for prehospital care. West J Emerg Med. 2020;21(4):849–57.

- Hughes A, Almeland SK, Leclerc T, Ogura T, Hayashi M, Mills JA, Norton I, Potokar T. Recommendations for burns care in mass casualty incidents: WHO Emergency Medical Teams Technical Working Group on Burns (WHO TWGB) 2017-2020. Burns. 2021;47(2):349–70. doi:10.1016/j.burns.2020.07.001

- Kimura K, Kimura T, Ishihara M, Nakagawa Y, Nakao K, Miyauchi K, Sakamoto T, Tsujita K, Hagiwara N, Miyazaki S, et al. JCS 2018 guideline on diagnosis and treatment of acute coronary syndrome. Circ J. 2019;83(5):1085–196. doi:10.1253/circj.CJ-19-0133

- Kleinman ME, Goldberger ZD, Rea T, Swor RA, Bobrow BJ, Brennan EE, Terry M, Hemphill R, Gazmuri RJ, Hazinski MF, et al. 2017 American Heart Association focused update on adult basic life support and cardiopulmonary resuscitation quality: an update to the american heart association guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation. 2018;137(1):e7–e13. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000539

- Le Conte P, Terzi N, Mortamet G, Abroug F, Carteaux G, Charasse C, Chauvin A, Combes X, Dauger S, Demoule A, et al. Management of severe asthma exacerbation: guidelines from the Societe Francaise de Medecine d‘Urgence, the Societe de Reanimation de Langue Francaise and the French Group for Pediatric Intensive Care and Emergencies. Ann Intensive Care. 2019;9(1):115.

- Lott C, Truhlář A, Alfonzo A, Barelli A, González-Salvado V, Hinkelbein J, Nolan JP, Paal P, Perkins GD, Thies K-C, et al. European resuscitation council guidelines 2021: cardiac arrest in special circumstances. Resuscitation. 2021;161:152–219. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2021.02.011

- Lou M, Ding J, Hu B, Zhang Y, Li H, Tan Z, Wan Y, Xu AD. Chinese Stroke Association guidelines for clinical management of cerebrovascular disorders: executive summary and 2019 update on organizational stroke management. Stroke Vasc Neurol. 2020;5(3):260–9. doi:10.1136/svn-2020-000355

- Lyng JW, White C, Peterson TQ, Lako-Adamson H, Goodloe JM, Dailey MW, Clemency BM, Brown LH. Non-auto-injector epinephrine administration by basic life support providers: a literature review and consensus process. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2019;23(6):855–61. doi:10.1080/10903127.2019.1595235

- Madar J, Roehr CC, Ainsworth S, Ersdal H, Morley C, Rudiger M, Skare C, Szczapa T, Te Pas A, Trevisanuto D, et al. European resuscitation council guidelines 2021: newborn resuscitation and support of transition of infants at birth. Resuscitation. 2021;161:291–326. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2021.02.014

- Maschmann C, Jeppesen E, Rubin MA, Barfod C. New clinical guidelines on the spinal stabilisation of adult trauma patients - consensus and evidence based. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2019;27(1):77. doi:10.1186/s13049-019-0655-x

- Medley TL, Miteff C, Andrews I, Ware T, Cheung M, Monagle P, Mandelstam S, Wray A, Pridmore C, Troedson C, et al. Australian clinical consensus guideline: the diagnosis and acute management of childhood stroke. Int J Stroke. 2019;14(1):94–106. doi:10.1177/1747493018799958

- Megarbane B, Oberlin M, Alvarez JC, Balen F, Beaune S, Bedry R, Chauvin A, Claudet I, Danel V, Debaty G, et al. Management of pharmaceutical and recreational drug poisoning. Ann Intensive Care. 2020;10(1):157.

- Mentzelopoulos SD, Couper K, Voorde PV, Druwe P, Blom M, Perkins GD, Lulic I, Djakow J, Raffay V, Lilja G, et al. European resuscitation council guidelines 2021: ethics of resuscitation and end of life decisions. Resuscitation. 2021;161:408–32. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2021.02.017

- Mills BM, Conrick KM, Anderson S, Bailes J, Boden BP, Conway D, Ellis J, Feld F, Grant M, Hainline B, et al. Consensus recommendations on the prehospital care of the injured athlete with a suspected catastrophic cervical spine injury. Clin J Sport Med. 2020;30(4):296–304. doi:10.1097/JSM.0000000000000869

- Mitchell SJ, Bennett MH, Bryson P, Butler FK, Doolette DJ, Holm JR, Kot J, Lafere P. Pre-hospital management of decompression illness: expert review of key principles and controversies. Diving Hyperb Med. 2018;48(1):45–55. doi:10.28920/dhm48.1.45-55

- Munjal M, Ahmed SM, Garg R, Das S, Chatterjee N, Mittal K, Javeri Y, Saxena S, Khunteta S. The transport medicine society consensus guidelines for the transport of suspected or confirmed COVID-19 patients. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2020;24(9):763–70. doi:10.5005/jp-journals-10071-23584

- Nasr A, Alimohammadi N, Isfahani M, Alijanpour S. Development and domestication of a clinical guideline for pharmacological pain management of trauma patients in prehospital setting. Arch Trauma Res. 2019;8(2):110–7. doi:10.4103/atr.atr_18_19

- Nolan JP, Sandroni C, Bottiger BW, Cariou A, Cronberg T, Friberg H, Genbrugge C, Haywood K, Lilja G, Moulaert VRM, et al. European resuscitation council and European society of intensive care medicine guidelines 2021: post-resuscitation care. Intensive Care Med. 2021;47(4):369–421. doi:10.1007/s00134-021-06368-4

- Olasveengen TM, Semeraro F, Ristagno G, Castren M, Handley A, Kuzovlev A, Monsieurs KG, Raffay V, Smyth M, Soar J, et al. European resuscitation council guidelines 2021: basic life support. Resuscitation. 2021;161:98–114. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2021.02.009

- Onifer DJ, McKee JL, Faudree LK, Bennett BL, Miles EA, Jacobsen T, Morey JK, Butler FK. Jr. Management of hemorrhage from craniomaxillofacial injuries and penetrating neck injury in tactical combat casualty care: iTClamp mechanical wound closure device TCCC guidelines proposed change 19-04 06 June 2019. J Spec Oper Med. 2019;19(3):31–44. doi:10.55460/H8BG-8OUP

- Panchal AR, Berg KM, Cabanas JG, Kurz MC, Link MS, Del Rios M, Hirsch KG, Chan PS, Hazinski MF, Morley PT, et al. 2019 American Heart Association focused update on systems of care: dispatcher-assisted cardiopulmonary resuscitation and cardiac arrest centers: an update to the American Heart Association Guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation. 2019;140(24):e895–e903. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000733

- Panchal AR, Berg KM, Hirsch KG, Kudenchuk PJ, Del Rios M, Cabanas JG, Link MS, Kurz MC, Chan PS, Morley PT, et al. 2019 American Heart Association focused update on advanced cardiovascular life support: use of advanced airways, vasopressors, and extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation during cardiac arrest: an update to the American Heart Association guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation. 2019;140(24):e881–e94.

- Panchal AR, Berg KM, Kudenchuk PJ, Del Rios M, Hirsch KG, Link MS, Kurz MC, Chan PS, Cabanas JG, Morley PT, et al. 2018 American Heart Association focused update on advanced cardiovascular life support use of antiarrhythmic drugs during and immediately after cardiac arrest: an update to the American Heart Association guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation. 2018;138(23):e740–e9. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000613

- Perkins GD, Olasveengen TM, Maconochie I, Soar J, Wyllie J, Greif R, Lockey A, Semeraro F, Van de Voorde P, Lott C, et al. European resuscitation council guidelines for resuscitation: 2017 update. Resuscitation. 2018;123:43–50. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2017.12.007

- Powers WJ, Rabinstein AA, Ackerson T, Adeoye OM, Bambakidis NC, Becker K, Biller J, Brown M, Demaerschalk BM, Hoh B, et al. Guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: 2019 update to the 2018 guidelines for the early management of acute ischemic stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2019;50(12):e344–e418. doi:10.1161/STR.0000000000000211

- Rodriguez-Pardo J, Fuentes B, Alonso de Lecinana M, Campollo J, Calleja Castano P, Carneado Ruiz J, Egido Herrero J, Garcia Leal R, Gil Nunez A, Gomez Cerezo JF, et al. Acute stroke care during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ictus Madrid Program recommendations. Neurologia (Engl Ed). 2020;35(4):258–63.

- Roquilly A, Vigue B, Boutonnet M, Bouzat P, Buffenoir K, Cesareo E, Chauvin A, Court C, Cook F, de Crouy AC, et al. French recommendations for the management of patients with spinal cord injury or at risk of spinal cord injury. Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med. 2020;39(2):279–89. doi:10.1016/j.accpm.2020.02.003

- Schmidt AC, Sempsrott JR, Hawkins SC, Arastu AS, Cushing TA, Auerbach PS. Wilderness medical society clinical practice guidelines for the treatment and prevention of drowning: 2019 update. Wilderness Environ Med. 2019;30(4S):S70–S86. doi:10.1016/j.wem.2019.06.007

- Schon CA, Gordon L, Holzl N, Milani M, Paal P, Zafren K. Determination of death in mountain rescue: recommendations of the international commission for mountain emergency medicine (ICAR MedCom). Wilderness Environ Med. 2020;31(4):506–20. doi:10.1016/j.wem.2020.06.013

- Semeraro F, Greif R, Böttiger BW, Burkart R, Cimpoesu D, Georgiou M, Yeung J, Lippert F, S Lockey A, Olasveengen TM, et al. European resuscitation council guidelines 2021: systems saving lives. Resuscitation. 2021;161:80–97. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2021.02.008

- Smith M, Johnston K, Withnall R. Systematic approach to delivering prolonged field care in a prehospital care environment. BMJ Mil Health. 2021;167(2):93–8. doi:10.1136/jramc-2019-001224

- Soar J, Bottiger BW, Carli P, Couper K, Deakin CD, Djarv T, Lott C, Olasveengen T, Paal P, Pellis T, et al. European resuscitation council guidelines 2021: adult advanced life support. Resuscitation. 2021;161:115–51. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2021.02.010

- Spahn DR, Bouillon B, Cerny V, Duranteau J, Filipescu D, Hunt BJ, Komadina R, Maegele M, Nardi G, Riddez L, et al. The European guideline on management of major bleeding and coagulopathy following trauma: fifth edition. Crit Care. 2019;23(1):98. doi:10.1186/s13054-019-2347-3

- Strapazzon G, Reisten O, Argenone F, Zafren K, Zen-Ruffinen G, Larsen GL, Soteras I. International Commission for Mountain Emergency Medicine Consensus Guidelines for on-site management and transport of patients in canyoning incidents. Wilderness Environ Med. 2018;29(2):252–65. doi:10.1016/j.wem.2017.12.002

- Sumann G, Moens D, Brink B, Brodmann Maeder M, Greene M, Jacob M, Koirala P, Zafren K, Ayala M, Musi M, et al. Multiple trauma management in mountain environments - a scoping review: evidence based guidelines of the International Commission for Mountain Emergency Medicine (ICAR MedCom). Intended for physicians and other advanced life support personnel. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2020;28(1):117. doi:10.1186/s13049-020-00790-1

- Terheggen U, Heiring C, Kjellberg M, Hegardt F, Kneyber M, Gente M, Roehr CC, Jourdain G, Tissieres P, Ramnarayan P, et al. European consensus recommendations for neonatal and paediatric retrievals of positive or suspected COVID-19 patients. Pediatr Res. 2021;89(5):1094–100. doi:10.1038/s41390-020-1050-z

- Van de Voorde P, Turner NM, Djakow J, de Lucas N, Martinez-Mejias A, Biarent D, Bingham R, Brissaud O, Hoffmann F, Johannesdottir GB, et al. European resuscitation council guidelines 2021: paediatric life support. Resuscitation. 2021;161:327–87. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2021.02.015

- Vanhoy MA, Horigan A, Stapleton SJ, Valdez AM, Bradford JY, Killian M, Reeve NE, Slivinski A, Zaleski ME, et al. Clinical practice guideline: family presence. J Emergency Nurs. 2019;45(1):76-e1.

- Willmore R. Cardiac arrest secondary to accidental hypothermia: rewarming strategies in the field. Air Med J. 2020;39(1):64–7. doi:10.1016/j.amj.2019.09.012

- Wong GC, Welsford M, Ainsworth C, Abuzeid W, Fordyce CB, Greene J, Huynh T, Lambert L, Le May M, Lutchmedial S, et al. 2019 Canadian Cardiovascular Society/Canadian Association of Interventional Cardiology guidelines on the acute management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: focused update on regionalization and reperfusion. Can J Cardiol. 2019;35(2):107–32. doi:10.1016/j.cjca.2018.11.031

- Yokobori S, Kanda J, Okada Y, Okano Y, Kaneko H, Kobayashi T, Kondo Y, Shimazaki J, Takauji S, Hayashida K, et al. Working group on heatstroke medical care during the C-e. Heatstroke management during the COVID-19 epidemic: recommendations from the experts in Japan. Acute Med Surg. 2020;7(1):e560.

- Zideman DA, Singletary EM, Borra V, Cassan P, Cimpoesu CD, De Buck E, Djarv T, Handley AJ, Klaassen B, Meyran D, et al. European Resuscitation Council Guidelines 2021: First aid. Resuscitation. 2021;161:270–90. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2021.02.013

- Zileli M, Osorio-Fonseca E, Konovalov N, Cardenas-Jalabe C, Kaprovoy S, Mlyavykh S, Pogosyan A. Early management of cervical spine trauma: WFNS spine committee recommendations. Neurospine. 2020;17(4):710–22. doi:10.14245/ns.2040282.141

- Martin-Gill C, Higgins JS, Van Dongen HPA, Buysse DJ, Thackery RW, Kupas DF, Becker DS, Dean BE, Lindbeck GH, Guyette FX, et al. Proposed performance measures and strategies for implementation of the fatigue risk management guidelines for emergency medical services. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2018;22(sup1):102–9.

- Fischer PE, Perina DG, Delbridge TR, Fallat ME, Salomone JP, Dodd J, Bulger EM, Gestring ML. Spinal motion restriction in the trauma patient - a joint position statement. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2018;22(6):659–61. doi:10.1080/10903127.2018.1481476

- Ong GY, Ng BHZ, Mok YH, Ong JS, Ngiam N, Tan J, Lim SH, Ng KC. Interim Singapore guidelines for basic and advanced life support for paediatric patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19. Singapore Med J. 2022;63(8):419–25.

- Zong ZW, Chen SX, Qin H, Liang HP, Yang L, Zhao YF. Representing the Youth Committee on Traumatology branch of the Chinese Medical Association tPLAPC, Youth Committee on Disaster Medicine tTbotCMRA, the Disaster Medicine branch of the Chongqing Association of Integrative M. Chinese expert consensus on echelons treatment of pelvic fractures in modern war. Mil Med Res. 2018;5(1):21.

- Zong ZW, Zhang LY, Qin H, Chen SX, Zhang L, Yang L, Li XX, Bao QW, Liu DC, He SH, et al. Expert consensus on the evaluation and diagnosis of combat injuries of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army. Mil Med Res. 2018;5(1):6.

- Koenig KL, Benjamin SB, Beÿ CK, Dickinson S, Shores M. Emergency department management of the sexual assault victim in the COVID era: a model SAFET-I guideline from San Diego County. J Emerg Med. 2020;59(6):964–74. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2020.07.047

- Carney N, Totten AM, Cheney T, Jungbauer R, Neth MR, Weeks C, Davis-O'Reilly C, Fu R, Yu Y, Chou R. Prehospital airway management: a systematic review. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2022;26(5):716–27.