Abstract

Background

Timely prehospital emergency care significantly improves health outcomes. One substantial challenge delaying prehospital emergency care is in locating the patient requiring emergency services. The goal of this study was to describe challenges emergency medical services (EMS) teams in Rwanda face locating emergencies, and explore potential opportunities for improvement.

Methods

Between August 2021 and April 2022, we conducted 13 in-depth interviews with three stakeholder groups representing the EMS response system in Rwanda: ambulance dispatchers, ambulance field staff, and policymakers. Semi-structured interview guides covered three domains: 1) the process of locating an emergency, including challenges faced; 2) how challenges affect prehospital care; and 3) what opportunities exist for improvement. Interviews lasted approximately 60 min, and were audio recorded and transcribed. Applied thematic analysis was used to identify themes across the three domains. NVivo (version 12) was used to code and organize data.

Results

The current process of locating a patient experiencing a medical emergency in Kigali is hampered by a lack of adequate technology, a reliance on local knowledge of both the caller and response team to locate the emergency, and the necessity of multiple calls to share location details between parties (caller, dispatch, ambulance). Three themes emerged related to how challenges affect prehospital care: increased response interval, variability in response interval based on both the caller’s and dispatcher’s individual knowledge of the area, and inefficient communication between the caller, dispatch, and ambulance. Three themes emerged related to opportunities for processes and tools to improve the location of emergencies: technology to geolocate an emergency accurately and improve the response interval, improvements in communication to allow for real-time information sharing, and better location data from the public.

Conclusion

This study has identified challenges faced by the EMS system in Rwanda in locating emergencies and identified opportunities for intervention. Timely EMS response is essential for optimal clinical outcomes. As EMS systems develop and expand in low-resource settings, there is an urgent need to implement locally relevant solutions to improve the timely locating of emergencies.

Background

A prehospital emergency medical services (EMS) system can improve a country’s health outcomes and save lives. Few guidelines regarding the structure of EMS systems exist, particularly for low-resource settings, but it has been noted that the timely locating of an emergency is a challenge for many countries, even when they have ambulance services (Citation1, Citation2). Difficulty locating a patient requiring emergency care increases the response interval, contributes to overall inefficiency in the system, and ultimately can contribute to poor clinical outcomes (Citation3).

Life-threatening and time-sensitive injuries and diseases are among the primary causes of mortality and morbidity in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) (Citation4–7). Rwanda has a formal, national EMS system, and has seen rapid growth in EMS utilization (Citation8). However, this system still faces a number of challenges, including insufficient personnel, and limited technological and financial resources and communication infrastructure. The Ministry of Health strategic plan for the EMS system notes the ability to accurately and efficiently locate an emergency as a particularly prominent challenge that impedes timely, quality EMS services (Citation8).

This study explores the challenge of locating an emergency event for EMS teams working in Kigali, Rwanda, and offers stakeholder perspectives on potential opportunities to address these challenges.

Methods

Overview

This study is a collaboration between researchers at the University of Utah, University of Washington, University of Birmingham, Rwanda Biomedical Center division of emergency medical service in Rwanda (Service d’Aide Medicale Urgente, or SAMU), and partners at the University Teaching Hospital of Kigali. The study was funded by the US National Institutes of Health (R21 TW011636) with the intent of developing and piloting a mobile health tool in Kigali, Rwanda to improve the communication between dispatch, ambulances, and receiving hospitals, as a means of improving patient health outcomes in medical emergency settings. In this phase of the project, we conducted and analyzed individual in-depth interviews with stakeholders to describe challenges that EMS teams in Rwanda face in responding efficiently to emergencies, and to explore potential opportunities for improvement.

Setting

Rwanda has a well-structured health system that includes the Ministry of Health, Rwanda Biomedical Center, eight referral hospitals, and four provincial hospitals, as well as district hospitals, local health centers and health posts, and community health workers (Citation9). In addition, private health care infrastructure supports these public health care provisions (Citation10). The city of Kigali is divided into two main types of areas: urban and suburban/rural. In urban areas, street and house numbers are easily identifiable during EMS response. In suburban and rural areas there are current limitations in the prevalence of street and house numbers, but availability of street and house numbers is increasing yearly. The national EMS system is directed by SAMU, which has a national jurisdiction and coordinates a dispatch center and 344 ambulances deployed throughout the country. Individuals reporting medical emergencies can call a national number (“912”), which is received by the SAMU central dispatch center, who can deploy and support ambulances and emergency medical field teams (Citation9).

Study Population

This study included a convenience sample of 13 stakeholders recruited from SAMU and the Ministry of Health representing three groups: central dispatch center staff, ambulance field staff, and policymakers working on the EMS system. Prospective participants were identified by SAMU leadership as individuals who would be available to participate in interviews and provide meaningful insights into the topic. Eligible participants were identified through workplace rosters, and contacted in person or through email or phone to introduce the study. All individuals who were contacted consented to participate.

Procedures

Each interview was conducted at a site and time convenient to the participant and interviewer, either in person or via Zoom. Interviews were conducted by the second author MN, who has experience working for SAMU as a nurse anesthetist. Interviews were conducted in the language preferred by the participant (English, French, or Kinyarwanda). The interview guides were tailored to the stakeholder group and included open-ended questions, followed by more specific inquiries to further explore examples and detailed information. The guides included three main sections: perspectives on current prehospital emergency care continuum, suggestions for improvements to the current system, and thoughts on development of a mobile health tool to address challenges. Each of these three topics received approximately equal attention during the interview process. Interviews were audio-recorded with participant consent, and were transcribed; interviews in French and Kinyarwanda were translated into English.

Analysis

Interview transcripts were organized and coded using NVivo (Version 12). Applied thematic analysis (Citation11) was used to identify themes across three domains: the process of locating an emergency, how challenges affect prehospital care, and opportunities for processes and tools. First, five transcripts were reviewed to identify inductive themes in each domain and to create a detailed codebook. As coding commenced, the codebook was revised to add additional codes, or expand the definition of codes. Coding was conducted by the first author (MH) with direct supervision by the second author (MHW), who has expertise in qualitative methods. The final code report was shared with members of the Rwandan team, including the primary interviewer (second author, MN) and the immediate past head of accident and emergency at the University Hospital of Kigali (seventh author, MN) in order to interpret and contextualize the data.

Ethics

The study was approved by the ethical review boards of the University Teaching Hospital of Kigali and the University of Utah. All participants provided oral informed consent, and no financial incentives were provided for participation.

Results

The sample (n = 13) represented three stakeholder groups within the EMS response system in Rwanda: full-time communication and dispatch officers (n = 8), ambulance field staff (n = 8), and policymakers (n = 3). Six individuals were nurse anesthetists who rotated across both the dispatch center and the field ambulance.

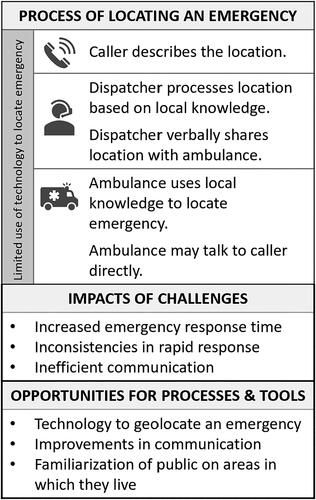

summarizes the themes that emerged across three domains: the process of locating an emergency, how challenges of locating the emergency affect prehospital care, and opportunities for processes and tools to improve emergency location.

Current Process of Locating an Emergency

Stakeholder interviews outlined the current process of locating an emergency. When dispatch first receives a call, they ask the caller to describe information about their location.

The caller calls 912. We ask the caller where the incident happened. They orient us to their location. We just are oriented by the caller. (Dispatch Staff, Interview 003)

The dispatcher processes the location based on his or her personal knowledge of and familiarity with the area, using landmarks when needed.

In case the caller doesn’t know the exact name of the cell, or sector, it may have some landmarks that will allow the dispatcher to know the location. (Dispatch & Ambulance Staff, Interview 001)

The dispatcher then shares location details with the ambulance staff, describing it the way the caller had.

We describe [the location] just as we have got it from the caller and if the team is not easily locating the scene, we call again the caller and share the information to the field team. (Dispatch & Ambulance Staff, Interview 006)

If teams get lost and callers are unable to provide guidance, no technological tools are available to assist in geolocation.

Sometimes teams get lost on the way and sometimes the callers don’t know the place to guide the dispatch team. And the latter does not have technological capacity to geolocate. (Policymaker, Interview 019)

Ambulance staff use their own knowledge and experience with the area to locate the emergency to the best of their ability.

The teams reach the scene using their ordinary capabilities…It’s just the basic information, landmarks that are shared from the caller to dispatch that the ambulance team will rely on. (Dispatch & Ambulance Staff, Interview 001)

The dispatch staff may reach out again to the caller to get additional information about the location. If needed, ambulance staff may also speak directly with the caller in order to locate the scene of emergency.

Sometimes we share the caller’s number to the (ambulance) team so that they can call the caller to make sure that the description the caller is giving us is okay for them to get an idea of that location. (Dispatch Staff, Interview 004)

Across all the stages of locating the emergency, there is very limited use of technology. Some dispatch and ambulance staff described using technology informally, such as using their personal smartphones or tablets for accessing map technology or communicating with callers via WhatsApp to share geo-locations.

We judge by using landmarks and sometimes when it’s a patient who can have like a tablet (smartphone) and when we are confused we can tell them to locate the area and send us by our own (personal) phones, on WhatsApp. And we make a WhatsApp localization by putting in Google maps and know that area. (Dispatch & Ambulance Staff, Interview 006)

How Challenges Locating an Emergency Affect Prehospital Care

The challenges associated with locating an emergency had three significant effects: 1) increased EMS response interval, 2) inconsistencies in rapid response, and 3) inefficient communication.

First, challenges in locating an emergency contribute to increased response intervals overall. Participants spoke about how these delays could lead to negative health outcomes.

I think the main challenge is the patient location. And as the emergency medical service is relying on the time response to save lives, we know that any second, minute lost is certainly a life that is lost. (Dispatch & Ambulance Staff, Interview 001)

Second, challenges in locating an emergency contributed to inconsistent efficiency of care. If callers are able to describe their locations and EMS staff on service know the area, then response intervals can be good. However, in the absence of that localized knowledge, response intervals are likely to be poor.

You just try to tell them to describe the location and you imagine with your experience. If you have been to that location before, you can get the idea. If you haven’t been to the location before you tell (the caller) to get someone who is familiar with that location because it’s very challenging because sometimes the caller can misdirect the team because he or she doesn’t know the location. (Dispatch Staff, Interview 004)

Third, challenges in locating an emergency contribute to an inordinate amount of time spent on location-focused communication, which stretches already scarce human resources. Because this communication is verbal, with independent phone calls among three parties (caller, dispatch, and ambulance), it is not only time-consuming, but also inefficient.

I think these are some of the challenges that are hindering our operations. So, there is a gap of the inter-operability of EMS, hospitals, and the caller, especially on the flow of information. And this is playing a critical role on the time response in a negative way. (Dispatch & Ambulance Staff, Interview 001)

Opportunities for Processes and Tools

In stakeholder interviews, three specific areas were identified as opportunities to improve the efficient location of emergencies: 1) technology to geolocate an emergency, 2) improvements in communication, and 3) familiarization of the public on areas in which they live.

Participants universally noted the need for technological tools to automatically geo-locate an emergency based on the call.

My wish is to have a software that can help us to locate the call, the exact place where the call comes from, that can help us and then can improve our response time today for the person who really needs assistance. (Dispatch & Ambulance Staff, Interview 005)

Participants also expressed the need for improvements in communication, recommending tools that facilitate real-time interaction between the patient, dispatch, and ambulance as a way to reduce delays caused by the current back and forth nature of calls among the three parties.

It would be better if there was a system to locate the caller directly without asking the call center. I mean a connection of the dispatcher and the ambulance team so that they know exactly where to go. (Dispatch & Ambulance Staff, Interview 009)

Finally, participants suggested initiatives to familiarize the public on the areas in which they live as a way to improve the public’s ability to communicate their location in the event of an emergency.

Infrastructures are there, but people are not aware of that. They do not see why there is a number on the street. They do not see the usefulness of the number of their compound. I think that government should increase the awareness of the community about the role or the use of those infrastructures. (Dispatch & Ambulance Staff, Interview 013)

Discussion

This study documents the experiences and perspectives of EMS stakeholders in Rwanda regarding the challenge of locating emergencies. While Rwanda has a robust EMS system that is a model for other countries in Africa, the task of locating emergency incidents remains a challenge that compromises efficient care. Participants in the study described the current process of locating an emergency and identified areas where efficiency could be enhanced. Improving this process is important as even the best EMS teams and most updated technology and supplies will be wasted if an ambulance cannot reach patients quickly (Citation12). Tools to improve the location of emergencies have the potential to save time and in turn improve patient outcomes.

A notable challenge in Rwanda’s current EMS system is the limited and only informal use of technology across all stages of locating emergency events. When an ambulance is delayed in correctly identifying the location of an emergency event, the trained EMS staff is delayed arriving at the scene (Citation13). Since rapid response is crucial in emergency situations, an increase in response intervals due to inefficient location of the emergency can lead to morbidity and mortality (Citation14). The data suggest that system factors contribute to inefficiencies in prehospital care, including inconsistencies as a result of variability in how well locations are identified by the callers and described to dispatch staff, as well as a staff members’ reliance on personal familiarity and knowledge of an area. These factors also result in fractured communication, as verbal handover and the back and forth nature of numerous calls between dispatcher, ambulance, and caller may result in key information being lost, particularly in the hectic circumstances of emergency calls.

Stakeholders noted several areas with opportunity to improve the efficient location of emergencies. There is a need for technological tools to automatically geo-locate an emergency, in order to minimize inconsistencies inherent in relying on personal familiarity of an area and depending on the caller’s ability to describe the location of an emergency effectively (Citation15). A technological tool with the capability of automatically sharing the caller’s geo-location to dispatch could reduce these inconsistencies, and reduce delays that are a result of inability to identify location, allowing for more rapid response intervals (Citation16). As GPS-enabled phones are increasingly ubiquitous, this technology holds great promise, but dependence on GPS-enabled phones may cause inequity in access to EMS services. Similarly, stakeholders expressed the need for improvements in communication, suggesting the development of technology to support three-way communication between the caller, dispatch, and the ambulance team. More streamlined communication could reduce delays caused by the current back and forth nature of independent phone calls between the caller, dispatch, and ambulance (Citation17). Participants also suggested the creation and implementation of initiatives that familiarize the public on the areas in which they live and visit, such as radio or television announcements about the importance of knowing street names in the area. Such an initiative could improve the general population’s ability to communicate their location to dispatch staff in the event of an emergency, reducing delays in locating the emergency and improving response intervals (Citation18). Previous public education initiatives have worked well in changing public health behavior in Rwanda, including initiatives to increase community-based health insurance coverage, decrease of maternal/child mortality, and introduction of HPV vaccines (Citation19–21).

Study Limitations

Limitations of the study design and methods must be considered. First, this study includes perspectives from three stakeholder groups: ambulance dispatchers, ambulance field staff, and policymakers. However, other stakeholder groups that could provide valuable feedback were not included, such as community members, patients, and local telecommunications/cell phone companies, limiting the discussion of opportunities for process and tools to those suggested by individuals employed by the EMS system, rather than the general public using the EMS system. Second, the interviews were subject to social desirability bias. The interview participants may have moderated their perspectives since the interviewer was a member of the EMS infrastructure. However, the key themes were consistent across all interviews. Lastly, this study focused on staff who predominantly work in the capital city of Kigali, so their perspectives may not reflect the challenges to providing EMS care in the rural provinces of the country.

Conclusion

This study has identified challenges faced by the EMS system in Kigali, Rwanda in locating emergencies, assessed the effects of those challenges, and identified opportunities for intervention through process and tool development. Timely EMS response is essential for optimal clinical outcomes, particularly in low-resource settings, and there is an urgent need to implement locally relevant solutions to improve the efficient location of emergencies in Rwanda. These solutions could be evaluated and adapted to fit the needs and circumstances of other low-resource settings globally.

Disclosure Statement

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Jayaraman S, Ntirenganya F, Nkeshimana M, Rosenberg A, Dushime T, Kabagema I, Uwitonze JM, Uwitonize E, Nyinawankusi J d, Riviello R, et al. Building trauma and EMS systems capacity in Rwanda: lessons and recommendations. Ann Glob Health. 2021;87(1):104.

- World Health Organization. Prehospital trauma care systems/ceditors: scott Sasser … [et al.]. World Health Organization; 2005 [cited 2023 Jan 10]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/43167

- Osebor I, Misra S, Omoregbe N, Adewumi A, Fernandez-Sanz L. Experimental simulation-based performance evaluation of an SMS-based emergency geolocation notification system. J Healthc Eng. 2017;2017:e7695045. doi:10.1155/2017/7695045.

- Chisumpa VH, Odimegwu CO, Saikia N. Adult mortality in sub-Saharan Africa: cross-sectional study of causes of death in Zambia. Trop Med Int Health. 2019;24(10):1208–20. doi:10.1111/tmi.13302.

- Mould-Millman NK, Sasser SM, Wallis LA. Prehospital research in Sub-Saharan Africa: establishing research tenets. Acad Emerg Med. 2013;20(12):1304–9. doi:10.1111/acem.12269.

- Reiner RC, Hay SI, LBD Triple Burden Collaborators The overlapping burden of the three leading causes of disability and death in sub-Saharan African children. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):7457. doi:10.1038/s41467-022-34240-6.

- Razzak J, Usmani MF, Bhutta ZA. Global, regional and national burden of emergency medical diseases using specific emergency disease indicators: analysis of the 2015 Global Burden of Disease Study. BMJ Glob Health. 2019;4(2):e000733. doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2018-000733.

- EMS Strategic Plan. Ministry of Health of Rwanda. 2018.

- Rosenberg A, Nyinawankusi J, Habihirwe R, Dworkin M, Nsengimana V, Putman J, et al. Prehospital emergency obstetric care by SAMU in Kigali, Rwanda. Obstet Gynecol Res. 2020;3(2):81–94.

- Private Health Facilities in Rwanda Health Service Package. Republic of Rwanda Ministry of Health; 2017 [cited 2023 Feb 26]. Available from: https://www.moh.gov.rw/index.php?eID=dumpFile&t=f&f=47025&token=7373f8b9333f62e5db302a7c33626662ca8a5e38

- Guest G, MacQueen K, Namey E. Applied Thematic Analysis. 2455 Teller Road, Thousand Oaks California 91320 United States: SAGE Publications, Inc., 2012 [cited 2023 Jan 14]. Available from: https://methods.sagepub.com/book/applied-thematic-analysis

- Kobusingye OC, Hyder AA, Bishai D, Hicks ER, Mock C, Joshipura M. Emergency medical systems in low- and middle-income countries: recommendations for action. Bull World Health Organ. 2005;83(8):626–31.

- Abedian S, Lornejad H, Kolivand P, Karampour A, Safari E. Save lives: the application of geolocation-awareness service in Iranian pre-hospital EMS information management system. World Academy of Science, Engineering and Technology International Journal of Health and Medical Engineering. 2021;15:337–40.

- McCoy CE, Menchine M, Sampson S, Anderson C, Kahn C. Emergency medical services out-of-hospital scene and transport times and their association with mortality in trauma patients presenting to an urban level I trauma center. Ann Emerg Med. 2013;61(2):167–74. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2012.08.026.

- Ecker H, Lindacher F, Dressen J, Wingen S, Hamacher S, Böttiger BW, Wetsch WA. Accuracy of automatic geolocalization of smartphone location during emergency calls—A pilot study. Resuscitation. 2020;146:5–12. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2019.10.030.

- Weinlich M, Kurz P, Blau MB, Walcher F, Piatek S. Significant acceleration of emergency response using smartphone geolocation data and a worldwide emergency call support system. PLoS One. 2018;13(5):e0196336. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0196336.

- Fukaguchi K, Goto T, Yamamoto T, Yamagami H. Experimental implementation of NSER mobile app for efficient real-time sharing of prehospital patient information with emergency departments: interrupted time-series analysis. JMIR Form Res. 2022;6(7):e37301. doi:10.2196/37301.

- Penadés MC, Vivacqua As Borges MRS, Canas JH. International Reports on Socio-Informatics (IRSI), Proceedings of the CSCW 2016-Workshop: toward a Typology of Participation in Crowdwork: the role of the public in the improvement of emergency plans. 2016 [cited 2023 Jan 26]. Available from: chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www.iisi.de/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/irsi_vol13-iss1_2016_penades.pdf

- Wang W, Temsah G, Mallick L. The impact of health insurance on maternal health care utilization: evidence from Ghana, Indonesia and Rwanda. Health Policy Plan. 2017;32(3):366–75. doi:10.1093/heapol/czw135.

- Binagwaho A, Farmer PE, Nsanzimana S, Karema C, Gasana M, de Dieu Ngirabega J, Ngabo F, Wagner CM, Nutt CT, Nyatanyi T, et al. Rwanda 20 years on: investing in life. Lancet. 2014;384(9940):371–5. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60574-2.

- Torres-Rueda S, Rulisa S, Burchett HED, Mivumbi NV, Mounier-Jack S. HPV vaccine introduction in Rwanda: impacts on the broader health system. Sex Reprod Healthc. 2016;7:46–51. doi:10.1016/j.srhc.2015.11.006.