Abstract

Background

Initial paramedic education must have sufficient rigor and appropriate resources to prepare graduates to provide lifesaving prehospital care. Despite required national paramedic accreditation, there is substantial variability in paramedic pass rates that may be related to program infrastructure and clinical support. Our objective was to evaluate US paramedic program resources and identify common deficiencies that may affect program completion.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional mixed methods analysis of the 2018 Committee on Accreditation of Educational Programs for the Emergency Medical Services Professions annual report, focusing on program Resource Assessment Matrices (RAM). The RAM is a 360-degree evaluation completed by program personnel, advisory committee members, and currently enrolled students to identify program resource deficiencies affecting educational delivery. The analysis included all paramedic programs that reported graduating students in 2018. Resource deficiencies were categorized into ten categories: faculty, medical director, support personnel, curriculum, financial resources, facilities, clinical resources, field resources, learning resources, and physician interaction. Descriptive statistics of resource deficiency categories were conducted, followed by a thematic analysis of deficiencies to identify commonalities. Themes were generated from evaluating individual deficiencies, paired with program-reported analysis and action plans for each entry.

Results

Data from 626 programs were included (response rate = 100%), with 143 programs reporting at least one resource deficiency (23%). A total of 406 deficiencies were identified in the ten categories. The largest categories (n = 406) were medical director (14%), facilities (13%), financial resources (13%), support personnel (11%), and physician interaction (11%). The thematic analysis demonstrated that a lack of medical director engagement in educational activities, inadequate facility resources, and a lack of available financial resources affected the educational environment. Additionally, programs reported poor data collection due to program director turnover.

Conclusion

Resource deficiencies were frequent for programs graduating paramedic students in 2018. Common themes identified were a need for medical director engagement, facility problems, and financial resources. Considering the pivotal role of EMS physicians in prehospital care, a consistent theme throughout the analysis involved challenges with medical director and physician interactions. Future work is needed to determine best practices for paramedic programs to ensure adequate resource availability for initial paramedic education.

Introduction

Paramedics are often the first advanced life support (ALS) responders encountered outside a health care facility, making them an essential part of the health care workforce (Citation1,Citation2). When paramedics arrive at a prehospital scene, they can bring high levels of clinical judgment to the public paired with an ability to perform interpretive diagnostics and provide life-saving procedures and medication administration (Citation3). Providing such detailed care requires knowledge, skills, and abilities developed in an academic setting with rigorous educational competency standards and national certification processes (Citation4). In greater than 95% of states and territories in the United States (US), this includes confirmed entry-level competency through a validated national certification assessment (Citation5).

To prepare students for these tasks, standards for paramedic educational programs must have similar rigor. Paramedic education programs in the United States are typically at least 1 year in length and exceed 1,000 hours of coursework (Citation6). With this condensed period, clear objectives and goals are needed to support the educational framework. In addition, US paramedic educational programs must meet national accreditation standards with regular evaluations of the facilities and program personnel to ensure continuing institutional quality (Citation6). These evaluations include reviewing the qualifications for program personnel, curriculum standards, and assessments from students and graduates (Citation7). All of these aspects are in place to provide safeguards for the student and the public.

Despite these standards, there is significant variation in the quality and preparation of paramedics during their initial education (Citation6,Citation8). Previous work has attempted to define high performance paramedic educational programs and their associated characteristics (Citation9,Citation10). However, little is known concerning the aspects of program infrastructure that affect success. We aim to better understand paramedic educational program resource deficiencies in the US and identify common deficiencies that may affect successful program completion.

Methods

Study Design and Population

We performed a retrospective cross-sectional mixed methods analysis of the 2018 Committee on Accreditation of Education Programs for the Emergency Medical Services Professions (CoAEMSP) annual program report survey. Included in this analysis were all Commission on Accreditation of Allied Health Education Programs (CAAHEP)-accredited and CoAEMSP-Letter of Review paramedic programs with enrolled students in 2018. The American Institutes of Research Institutional Review Board determined this study to be exempt.

Paramedic Accreditation and Annual Report

In the United States, graduation from a nationally accredited paramedic program is a requirement for certification, as it has been a prerequisite for attempting the National Registry of Emergency Medical Technicians (NREMT) paramedic certification exam since 2013 (Citation11). Accreditation of paramedic education programs is recommended by CoAEMSP and provided under CAAHEP, a programmatic post-secondary accreditation agency recognized by the Council for Higher Education Accreditation, which accredits more than 2,200 entry-level education programs in 32 health science professions (Citation12). As part of this national accreditation, each paramedic education program must also have a sponsoring institution: a post-secondary academic institution, a hospital or medical center, governmental education or medical service, or a branch of the United States armed forces (Citation4).

CAAHEP Standards and Guidelines provide an important framework for programs to measure and reflect on their overall effectiveness. Standard III.D, Resource Assessment, requires programs to at least annually assess the appropriateness and effectiveness of program resources, using this information as the basis for ongoing planning and improvement where necessary (Citation13). Data are self-reported by programs, and data definitions and quality are managed through education provided by CoAEMSP, including in-person conferences, webinars, newsletters, and email communication. The annual report is submitted for the program graduating class 2 years prior. Thus, the data reviewed were collected in 2020 but reflects program results from the 2018 paramedic cohort. This dataset was the most recent available from CoAEMSP at the time of the study.

Measurements

Data on paramedic educational program characteristics were collected, including program cohort and class sizes, program training, and infrastructure details. The numbers of classes or cohorts that graduated from the program during the survey period were reported as continuous variables categorized into meaningful cut points (0, 1, 2, 3, and greater than 4). Similarly, the total number of students enrolled in each program was a continuous variable and reported as median and interquartile range (IQR). The National Association of State EMS Officials region was a categorical variable, with each value corresponding to either the West, Western Plains, South, Great Lakes, or East regions (Citation14).

Additional program educational details were also evaluated. Total hours of instruction were defined as all phases of paramedic educational program hours, including didactic, laboratory, clinical, field experience, and capstone field internship. The total number of full-time faculty was measured as a continuous variable. The annual budget was categorized with meaningful cut points ($1–$100,000, $100,001–$500,000, $500,001–$1,000,000, $1,000,001–$1,500,000, $1,500,001–$2,000,000, or prefer not to answer). To measure program success, the proportion of students graduating was evaluated as a continuous variable, reported as median and IQR.

Lastly, the Resource Assessment Matrix (RAM) was evaluated. The RAM is a portion of the annual report, a holistic evaluation of the educational program completed by program personnel, advisory committee members, and students. The RAM is a standardized document required by all programs annually and is used to assess the availability of necessary resources (Citation13). This document is a composite measure that synthesizes the results of two separate surveys conducted by programs assessing resources available to both students and program representatives. The RAM is scored across ten parameters, with a corrective plan required for any scores below the established benchmark by CoAEMSP (80%). These parameters are program faculty, medical director, support personnel, curriculum, financial resources, facilities, clinical resources, field resources, learning resources, and physician interaction. The RAM requirements were dichotomized as meeting the benchmark or not.

Analysis

Included in this evaluation were all programs with students enrolled in a program cohort in 2018. Descriptive statistics were calculated (median, interquartile range, and frequency expressed as a percentage, as appropriate). Median and interquartile ranges were calculated for continuous variables. Frequencies and proportions were computed for categorical variables. As part of the preparation of self-reported data, any text or range responses to questions that asked for numbers (for example, a response of “240–280,” “at least 300”, etc. in response to “How many hours of instruction…?”) were removed. If a number was preceded by a qualifier such as a tilde (“∼”) or the word “approximately,” the qualifier was removed, and the value converted to a number. A response was excluded from the analysis if it was blank or ambiguous.

For the reported deficiencies and action plans, deductive thematic analysis was conducted, allowing for categorizing the data based on the key themes derived from the RAM (Citation15). First, a preliminary coding dictionary was developed based on previous themes reported in the RAM and the predefined categories by CoAEMSP. One study team member then coded the RAM output deficiencies and action plans for a small subset to confirm the final coding dictionary. The final coding dictionary was then used to code all program deficiencies and action plans. If multiple deficiencies were reported with the same theme, these were separated. If insufficient information or no RAM data were provided, it was themed as “insufficient data” or “no data provided.” These missing data were tabulated but excluded from the final list of themes. Finally, Wilcoxon rank-sum testing was used to evaluate changes in the proportion of graduating students between RAM compliant and RAM deficient programs. Statistical analysis was performed with Microsoft Excel and Stata IC Version 15.1 (Citation16).

Results

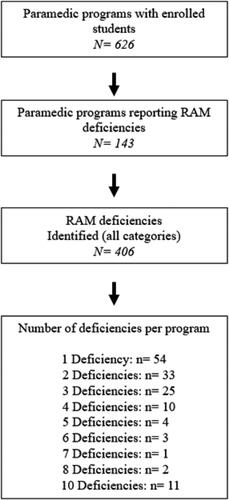

All programs graduating students in 2018 (n = 626) were included, encompassing a total of 17,422 students. Of these programs, 143 (23%) reported at least one RAM deficiency (). A total of 406 deficiencies were reported, with the number of deficient categories varying from 1 to 10, with the greatest occurring at one deficiency (13%).

Figure 1. Flow chart of the paramedic program RAM deficiencies and their distributions. A total of 143 of 626 programs report RAM deficiencies, with a cumulative total of 406 deficiencies ((1 * 54) + (2 * 33) + etc.).

Program demographics based on RAM compliance are noted in . A total of 4,178 (24%) students are enrolled in programs with reported deficiencies. Distributions of the number of cohorts per program and students enrolled per cohort were similar between RAM-compliant and RAM-deficiency programs. When program deficiencies were categorized by region, the areas with the most programs with any number of deficiencies were South and East at 48 (34%) and 35 (25%) programs, respectively. With respect to graduation rates, RAM-deficient programs had lower completion rates than RAM-compliant (median 79 and 81, respectively, p < 0.05).

Table 1. Demographics of paramedic educational programs that are RAM-compliant or have RAM deficiencies.

Thematic analysis was conducted, and the identified RAM deficiency domains are noted in . Out of the top five deficient domains, two regarded medical direction (medical director and physician interaction). Other highly deficient domains included facilities and financial resources. Excluded from this data are the missing values described by programs. Program responses of “no data collected” or “insufficient” responses accounted for 141 (35%) deficiencies. These themes were associated with programs most often reporting RAM surveys not being completed due to program director turnover. The specific themes underlying each deficiency domain are noted in . Themes that had greater than 10 deficiencies included limited medical director and physician interaction, lack of classroom space/equipment, and lack of faculty or clerical staffing.

Table 2. Identified RAM deficiency domains and their frequencies (n = 406 deficiencies).

Table 3. Theme frequency for each RAM domain.

Themes of the typical action plans developed by programs to address domain deficiencies are noted in . These action plan themes describe the various approaches taken to address the deficiencies. For example, for medical direction, the span of action plans encompassed hiring a new medical director, hiring an assistant medical director, intervening and speaking to the current medical director, and monitoring the medical director’s performance. Similarly, facility deficiency plans also spanned advocating for a new building, improving air conditioning and heating systems, providing more lab space, and continually monitoring facility conditions.

Table 4. Common action plans identified for each deficiency domain.

Discussion

Preparing paramedic clinicians for practice is a challenging task requiring significant educational infrastructure and qualified staff. Prior evaluations have demonstrated variability in program success, and one of the possible causes may be having appropriate resources for educating students (Citation8). In this evaluation, we describe resource deficiencies found in the RAM of accredited paramedic educational programs in the US. Resource deficiencies were frequent, and the primary domains identified were medical directors, facilities, and financial resources. The thematic analysis defined the large spectrum of challenges programs face and the diverse approaches to address them. Further, we found differences in graduation rates between programs that were RAM compliant and those that were not.

Lack of medical director involvement and physician interactions were documented as two of the most frequent RAM deficiencies (). This finding is a concerning trend since key aspects of the paramedic educational process depend on the medical director’s engagement. Based on CAAHEP standards, the medical director has the role of approving educational content, approving minimum requirements for patient contacts and procedures for students, approving processes leveraged to evaluate students throughout their training, and ensuring the competence of each graduate of the educational program (Citation4). Recognizing the critical role of physician interactions with paramedic students in training, this deficiency may significantly affect student success, though this still needs to be evaluated. Most importantly, medical directors should recognize that this deficiency holds the greatest opportunity for structured interventions since they are in the realm of control for a medical director (). Potential targets for intervention to enhance student experiences include the following: direct instruction of lecture or skill laboratories, case study discussion, cadaver lab dissections, emergency department teaching during clinical rotations, field ride-along, and end of course exam preparation.

Facilities and facility management were also noted as common deficiencies. Common themes identified included the need for additional classroom space and time or equipment in the lab. Recognizing that a core need for students is exposure to skills development for infrequent procedures, dedicated classroom and laboratory space is critically important (Citation17–19). One interesting theme in this domain was the common issue of temperature control in classroom settings. Previous evaluations have demonstrated that classroom temperature affects student perception, performance, and problem-solving (Citation20,Citation21). With this framework, developing a comfortable environment that supports the educational process is an important consideration.

Financial resource deficiencies were also a common thematic domain for programs and students. Financial aid was reported to be difficult for students to obtain, as well as a lack of ample space and equipment. This lack of funding limits the number of faculty and increases student to faculty ratios, limiting interactions and teaching opportunities. Additionally, this affeccts the quality and availability of teaching equipment (e.g., high fidelity simulation manikins, cadaver experiences) that are essential for student success. Finally, lack of scholarship availability may potentially limit opportunities for disadvantaged students. Taken together, financial challenges may affect student performance in various ways, and lacking financial resources continues to be common across paramedic educational programs (Citation22–25).

One significant challenge in analyzing the RAM data reported to CoAEMSP is the abundance of “no data collected” or “insufficient” responses. The lack of data collection accounted for over one-third of deficiencies, most often due to program director turnover. One study found that about half of the program directors, between 30 and 40 years old, wanted to leave their positions, and many reported the primary reasons as high workloads and little support (Citation26). Unfortunately, due to high rates of program director turnover, there is a lack of data concerning program resource needs that stem from a poor transitions in program leadership. This leads to delayed improvement of the educational environment (Citation26,Citation27).

Limitations

This evaluation was limited in several ways. First, the study was a cross-sectional evaluation of one year of reported data, thereby not capturing year-to-year variability. Additionally, programs that did not graduate students were not included in the study, which could limit reported deficiencies, and needs clarification. Further, the information provided by program directors limited thematic analysis of deficiencies and action plans, which may lead to misclassification bias. Finally, this was an analysis of self-reported data from each educational program to the accreditation agency, which may lead to bias that is not well-defined. However, since the data are reported to the accrediting body, the results may underestimate resource challenges.

Conclusion

Self-reported resource deficiencies were frequent in accredited paramedic education programs. The most frequent deficiencies were in the medical director, facilities, and financial resources categories. This study sheds light on the large-scale challenges around resource availability faced by paramedic educational programs and should be used as a guide to improve EMS educational environments. Further research is needed to better understand paramedic program resource deficiencies and their effect on program performance and overall student success.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Rivard MK, Cash RE, Mercer CB, Chrzan K, Panchal AR. Demography of the national emergency medical services workforce: a description of those providing patient care in the prehospital setting. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2021;25(2):213–20. doi:10.1080/10903127.2020.1737282.

- National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA). National EMS Scope of Practice Model 2019 (Report No. DOT HS 812-666). National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. https://www.ems.gov/pdf/National_EMS_Scope_of_Practice_Model_2019.pdf

- American Ambulance Association (AAA). 2021 ambulance industry employee turnover study. https://ambulance.org/sp_product/2022-ems-employee-turnover-study/

- Committee on Accreditation of Educational Programs for the Emergency Medical Services Professions (COAEMSP). Interpretations of the commission on accreditation of allied health education programs standards and guidelines. https://coaemsp.org/caahep-standards-and-guidelines.

- National Registry of Emergency Medical Technicians (NREMT). Paramedic certification. https://www.nremt.org/rwd/public/document/paramedic

- Ball MT, Powell JR, Collard L, York DK, Panchal AR. Administrative and educational characteristics of paramedic programs in the United States. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2022;37(2):152–56. doi:10.1017/S1049023X22000115.

- Committee on Accreditation of Educational Programs for the Emergency Medical Services Professions (COAEMSP). 2020 CoAEMSP annual report- frequently asked questions. https://coaemsp.org/annual-reports-caahep-accredited-programs.

- Moungey BM, Mercer CB, Powell JR, Cash RE, Rivard MK, Panchal AR. Paramedic and EMT program performance on certification examinations varies by program size and geographic location. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2022;26(5):673–81. doi:10.1080/10903127.2021.1980163.

- Rodriguez S, Crowe RP, Cash RE, Broussard A, Panchal AR. Graduates from accredited paramedic programs have higher pass rates on a national certification examination. J Allied Health. 2018;47(4):250–4.

- Margolis GS, Romero GA, Fernandez AR, Studnek JR. Strategies of high-performing paramedic educational programs. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2009;13(4):505–11. doi:10.1080/10903120902993396.

- National Registry of Emergency Medical Technicians (NREMT). Cognitive exams - general information. https://www.nremt.org/Document/cognitive-exams.

- Committee on Accreditation of Educational Programs for the Emergency Medical Services Professions (COAEMSP). https://coaemsp.org/

- Committee on Accreditation of Educational Programs for the Emergency Medical Services Professions (COAEMSP). Resource Assessment Matrix. Committee on Accreditation of Educational Programs for the Emergency Medical Services Professions. https://coaemsp.org/?mdocs-file=5740

- National Association of State EMS Officials: State Agencies & Regions. https://nasemso.org/about/state-agencies/

- Vaismoradi M, Turunen H, Bondas T. Content analysis and thematic analysis: implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nurs Health Sci. 2013;15(3):398–405. doi:10.1111/nhs.12048.

- Stata. Stata. https://www.stata.com/

- McKenna KD, Carhart E, Bercher D, Spain A, Todaro J, Freel J. Simulation use in paramedic education research (SUPER): a descriptive study. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2015;19(3):432–40. doi:10.3109/10903127.2014.995845.

- Birt J, Moore E, Cowling M. Improving paramedic distance education through mobile mixed reality simulation. Aust J Educ Technol. 2017;33(6):69–83. doi:10.14742/ajet.3596.

- Birtill M, King J, Jones D, Thyer L, Pap R, Simpson P. The use of immersive simulation in paramedicine education: a scoping review. Interact Learn Environ. 2023;31(4):2428–43. doi:10.1080/10494820.2021.1889607.

- Burke K, Burke-Samide B. Required changes in the classroom environment it’s a matter of design. Clearing House: J Educ Strategies, Issues Ideas. 2004;77(6):236–40. doi:10.3200/TCHS.77.6.236-240.

- Montazami A, Gaterell M, Nicol F, Lumley M, Thoua C. Developing an algorithm to illustrate the likelihood of the dissatisfaction rate with relation to the indoor temperature in naturally ventilated classrooms. Build Environ. 2017;111:61–71. doi:10.1016/j.buildenv.2016.10.009.

- Ruple JA, Frazer GH, Hsieh AB, Bake W, Freel J. The state of EMS education research project: characteristics of EMS educators. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2005;9(2):203–12. doi:10.1080/10903120590924807.

- Wills HL, Asbury EA. The incidence of anxiety among paramedic students. Aust J Paramed. 2019;16:1–6. doi:10.33151/ajp.16.649.

- Bentley MA, Shoben A, Levine R. The demographics and education of emergency medical services (EMS) professionals: a national longitudinal investigation. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2016;31(S1):S18–s29. In eng). doi:10.1017/s1049023x16001060.

- Brooks IA, Sayre MR, Spencer C, Archer FL. An historical examination of the development of emergency medical services education in the US through key reports (1966-2014). Prehosp Disaster Med. 2016;31(1):90–7. doi:10.1017/s1049023x15005506.

- Allmon EW. An exploration of turnover and turnover intention among program directors of nationally accredited paramedic education programs adult, higher, and community education. [theses & dissertations proquest]. Muncie, IN: Ball State University; 2020.

- Kokx GA. An exploration of program director leadership practices in nationally accredited paramedic education programs [theses & dissertations proquest]. Moscow, ID: University of Idaho; 2016.