Abstract

Background

Burnout among emergency health care professionals is well-described, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic. Prevention interventions, such as mindfulness, focus on the management of stress.

Objective

To evaluate the effects of the FIRECARE program (a mindfulness intervention, supplemented by heart coherence training and positive psychology workshops) on burnout, secondary stress, compassion fatigue, and mindfulness among advanced life support ambulance staff of the Paris Fire Brigade.

Materials and methods

We used a non-randomized, two-group quasi-experimental study design with a waitlist control and before-and-after measurements in each group. The intervention consisted of six, once-weekly, 2.5-h sessions that included individual daily meditation and cardiac coherence practice. The study compared intervention and waitlist control groups, and investigated baseline, post-program, and 3-month follow-up change on burnout (measuring using the ProQOL-5 scale) and mindfulness (measuring using the FMI scores). Baseline burnout (measured using the ProQOL-5) was evaluated and used in the analysis.

Results

Seventy-four 74 participants volunteered to participate; 66 were included in the final analysis. Of these, 60% were classified as suffering from moderate burnout, the ‘burnout cluster’. A comparison of intervention and waitlist control groups found a decrease in the burnout score in the burnout cluster (p = 0.0003; partial eta squared = 0.18). However, while secondary stress fell among the burnout cluster, it was only for participants in the intervention group; scores increased for those in the waitlist group (p = 0.003; partial eta squared = 0.12). The pre-post-intervention analysis of both groups also showed that burnout fell in the burnout cluster (p = 0.006; partial eta squared = 0.11). At 3-month follow-up, the burnout score was significantly reduced in the intervention group (p = 0.02; partial eta squared = 0.07), and both the acceptance (p = 0.007) and mindfulness scores (p = 0.05; partial eta squared = 0.05) were increased in the baseline burnout cluster.

Conclusion

FIRECARE may be a useful approach to preventing and reducing burnout among prehospital caregivers.

Introduction

Burnout among caregivers is a well-described pathology. Unfortunately, it is often under-diagnosed, and prevention remains insufficient. Emergency physicians are frequently confronted with the need to make stressful, crucial, and rapid decisions. They are especially vulnerable to burnout, and this situation has clearly worsened with the COVID-19 pandemic (Citation1, Citation2). Several studies have shown the benefits of mindfulness interventions among caregivers and first responders (Citation3) not only for burnout and stress management, but also for complications due to chronic stress, such as anxiety, depression, and insomnia (Citation4–15).

Mindfulness is defined here as a state of consciousness where attention is focused on the present moment, the ‘here and now’ (Citation16). By increasing awareness of the present moment through work on breathing and body sensations, it can enhance attention and concentration, help people distance themselves from their thoughts and ruminations, better-regulate their emotions and impulses, and improve health. Caregivers become more willing to respond to situations consciously rather than automatically, and therefore become more available to engage in caring relationships with their patients (Citation17). Furthermore, mindfulness is known to reinforce resilience (Citation18) and empathy (Citation4). New research also suggests that compassion and empathy are protective factors against burnout (Citation5), and predict lower levels of anxiety and depression (Citation6). Mindfulness now plays a major role in scientific research and among the public. The recent COVID-19 pandemic has stimulated interest in well-being interventions designed to reduce work-related stress among caregivers (Citation7–9). However, despite the high demand for interventions, they remain few and far between, and a key limitation for caregivers is a lack of availability due to their demanding professional workload (Citation10).

The Paris Fire Brigade (PFB) is the fire department of the City of Paris. It is a military institution. It provides fire protection services, technical rescue/special operations services, chemical, biological, radiological, nuclear, and high-yield explosive/hazardous materials response services, and emergency medical response services within Paris and three adjacent departments (Seine Saint-Denis, Val-de-Marne, Hautes-Seine). All year round, 24 h a day, the PFB deploys six ALS ambulances each staffed by an emergency physician, a nurse, and an ambulance operator. These ambulances form part of the Parisian prehospital rescue system, along with the civilian emergency medical service (called SAMU), serving an area of 762 km2 and 7 million inhabitants, and receiving at the 1-1-2 call-center (the public access number for emergency services in France) 3500 emergency calls per day. The ALS crews work on 24 or 48-h shifts, 120 shifts a year. They are among the first to respond to life-threatening incidents, and, consequently, are exposed to traumatic situations, such as death, grief, injury, or pain on a daily basis (Citation11–13). They are sleep-deprived and endure physical hardship, which weakens their resilience and capacity for compassion, and increases the risk of operational fatigue and burnout (Citation14). The risks are particularly high within the PFB because some caregivers have previously served as firefighters, and many of the physicians are military physicians who were deployed on active service before their assignment to the Brigade (Citation15). Therefore, these professionals are more at risk of developing three main pathologies linked to their day-to-day work: (i) compassion fatigue, described as a “deep, painful wear and tear to the distress of others” leading to a state of exhaustion and saturation of the care relationship (Citation19–21); (ii) vicarious trauma or secondary traumatic stress, a phenomenon first described by Figley, as a situation where the caregiver integrates into his or her cognitive universe the experiences, emotions, and traumas of his or her patients; and (iii) burnout, which refers to “physical, emotional and mental exhaustion resulting from prolonged investment in emotionally demanding work situations” (Citation22).

It has been established that intervention efficacy can be maximized if it builds on small social structures, and encourages team members to look out for each other, and support each other during stressful transitions (Citation23, Citation24). However, regular group mindfulness practice is difficult to achieve in a real-world military community. In addition, military personnel are often more focused on taking action than on looking after others. Finally, in the military environment, fear of stigmatization by both the institution and peers is another potential barrier to care (Citation25). These observations suggest that prevention programs must consider the possibility that military caregivers may be suffering from undiagnosed burnout.

In this context, we designed the FIRECARE program for the ALS ambulance staff of the PFB. The intervention was based on the mindfulness based on cognitive therapy (MBCT) program, supplemented with heart coherence training, and positive psychology workshops (to increase adherence). Heart coherence training is a breathing practice for managing stress and emotions. The person takes six breaths per minute, for a minimum of 3 min. The practice acts on the physical components of stress and leads to a rapid decrease in heart rate and respiratory frequency, and a reduction in vascular pressure (Citation26). Positive psychology refers to understanding and optimizing individual and collective potential through the prism of development and adaptability (Citation27).

Our objective was to evaluate the effects of the FIRECARE program on burnout, secondary stress, compassion fatigue (primary objective), and mindfulness (secondary objective) among ALS ambulances staff of the PFB. A third objective was to evaluate the maintenance of the effects obtained 3 months after the intervention.

Our hypothesis was that the implementation of the FIRECARE program would have a positive, demonstrable effect on the professional life of prehospital caregivers in the PFB, by reducing burnout and secondary traumatic stress with respect to baseline (primary outcome). The other hypotheses were that the FIRECARE program would increase the mindfulness functioning with respect to baseline and that the effects observed on burnout, secondary traumatic stress, and mindfulness functioning after the program were still present at 3 month follow-up.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

We used a non-randomized, two-group quasi-experimental study design with a waitlist control and before-and-after measurements in each group. Exposure to the intervention occurred over a 6-week period. Due to operational demands and difficulties in scheduling shifts, we were unable to randomize participants. Volunteers were allocated to the intervention or waitlist control group depending on their shifts, respecting a similar ratio of physicians, nurses, and ambulance operators.

The FIRECARE intervention was offered to members of the PFB medical team in 2021. Inclusion criteria were: (i) age over 18; (ii) working as a physician, nurse, or ambulance operator in the PFB; (iii) having had a recent medical checkup; (iv) willing to volunteer to participate in the intervention; and (v) having signed the consent form. The primary exclusion criterion was participation in another, parallel research study. Secondary exclusion criteria were: (i) having participated in the development and drafting of the research protocol; (ii) attending <50% of the program; (iii) having left the program and/or the study after one or more sessions; and (iv) developing, during the program, a psychological disorder requiring urgent treatment.

The FIRECARE Program

The FIRECARE program was inspired by the MBCT program, supplemented by heart coherence training and positive psychology workshops. It was composed of six, once-weekly sessions each lasting 2.5 h. Activities included mindfulness and positive psychology workshops, individual daily meditation, and heart coherence training. It was designed and delivered by an MBCT instructor with a degree in positive psychology and heart coherence training. The participants followed the program in person, remotely, or by replaying videos. All sessions followed the same structure. The content of the program is presented in . Heart coherence training was supported by the ZenSpire Army® device, designed by ZenSpire and the French Military Biomedical Research.

Table 1. The FIRECARE program.

Data Acquisition

A 28-item socio-biographical questionnaire was used to collect standard sociodemographic data, such as age, health status, profession, years of professional experience, and years in the PFB.

Psychological Variables

The Professional Quality of Life Scale version 5 (ProQOL-5) (Citation28) has been validated in French. It consists of 30 items rated from 1–5, divided into three subscales: burnout; secondary traumatic stress; and compassion satisfaction. There is no total score; the score for each construct is obtained from the sum of the values of the 10 items of each subscale. Scores are interpreted as low (≤22), average (23–41), and high (≥42).

The Freiburg Mindfulness Inventory (FMI) is a 14-item self-report mindfulness questionnaire. It measures the person’s ability to live fully in the present moment and assesses his or her level of self-perception (Citation29). The FMI has a total score and two subscale scores for presence and acceptance. The mean score is 38.98 (Citation30).

Practice and Satisfaction Measures

At the end of the intervention, and at 3-month follow-up, several questions were added to the questionnaire. These questions asked participants about the frequency of their meditation and heart coherence training practice, and their degree of satisfaction with the intervention.

Procedure

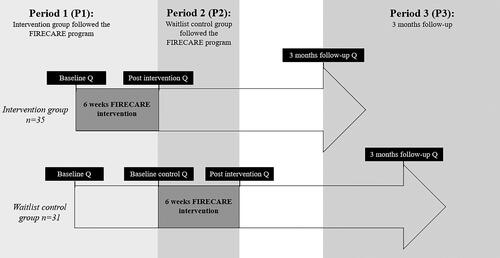

The FIRECARE intervention and the study evaluating it were presented to the PFB’s prehospital caregivers during an information meeting. After signing the clinical consent form and checking the inclusion and exclusion criteria, volunteers were divided into two groups, the intervention group and the waitlist control group that followed the FIRECARE program after the intervention group. Each group followed the FIRECARE program for 6 weeks. Trial participation is represented in .

Figure 1. Periods of interest during the program. P1 represents the first period in which the intervention group followed FIRECARE, and the control group was waitlisted, P2 represents the second period in which the waitlist control group followed FIRECARE. P3 is defined as three-month follow-up for the intervention group and the waitlist control group.

ProQOL-5 and FMI questionnaires were prepared in Sphinx software (Sphinx Online V4, France) and sent to participants’ emailboxes via a hyperlink. Questionnaires were sent to participants before the first FIRECARE intervention for both groups (i.e., baseline questionnaire); after the first intervention (i.e., post-intervention questionnaire for the intervention group; baseline control questionnaire for the waitlist control group); after the second intervention for the waitlist control group (i.e., post-intervention); and at 3-month follow-up for both groups. The 6-week time lag between the two groups made it possible to compare responses for the intervention and the waitlist control groups.

The following three periods of interest were defined. P1 represents the 6-week period during which the intervention group followed the FIRECARE program, and the control group was on the waitlist; P2 is the 6-week period during which the waitlist control group followed the FIRECARE program. P3 is defined as the 3-month follow-up for the intervention group and the control group. These periods are represented in .

Several studies have shown that mindfulness interventions are particularly effective in symptomatic patients (Citation31). We therefore decided to explore this angle and compare baseline data for symptomatic participants (those with burnout) with non-symptomatic participants. “Burnout” was defined as a score on the ProQOL-5 burnout subscale at baseline >23. “No burnout” was defined as a score ≤23.

The primary outcome was to compare subscale scores of the ProQOL-5 scale (i.e., burnout, secondary stress, and compassion satisfaction) for intervention and waitlist control groups after the first intervention, as a function of the burnout level at baseline. Secondary outcomes were to evaluate the immediate effect of the intervention, measured as FMI scores (i.e., total, presence, and acceptance), compared to the waitlist group, as a function of the burnout level at baseline; the immediate effect of the intervention on ProQOL-5’s subscales, FMI total, presence, and acceptances cores for both groups, as a function of their burnout level at baseline (before-and-after); and the persistence of the benefits of the FIRECARE intervention at 3-month follow-up, measured using the ProQOL-5 subscales, FMI total, presence, and acceptance, for both groups, as a function of their burnout level at baseline (before-and-after).

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were expressed as mean ± SD. Statistics were computed for all outcome measures with the Statistica software package (version 7.1, StaSoft-France, Maisons-Alfort, France). The Shapiro–Wilk test was used to determine whether data were normally distributed.

Our main aim was to evaluate the immediate effect of the FIRECARE intervention by comparing post-intervention scores on the ProQOL-5 scale to scores for the waitlist control group, as a function of participants’ burnout levels at baseline (intent to treat). The primary outcome was therefore the difference in burnout scores for the waitlist control group vs. the intervention group before and immediately after the first intervention. A positive effect was determined as a significant difference (p ≤ 0.05) between delta 1 intervention (i.e., delta 1i) and delta 1 control (i.e., delta 1c). For the significant effects, the effect size was indicated using partial eta squared, with a small effect size of 0.01, a medium effect size of 0.06, and a large effect size higher than 0.14 (Citation32). The estimator for the immediate effect of the intervention was the mean value of delta 1 and its standard deviation.

Secondary aims were to evaluate the immediate effect of the first FIRECARE intervention on FMI scores as a function of the burnout level at baseline (delta 1i vs. delta 1c); the immediate effect of the FIRECARE intervention on ProQOL-5 and FMI scores for all participants as a function of their burnout levels at baseline (delta 1i vs. delta 2); and the persistence of any benefits at 3-month follow-up, measured on ProQOL-5 and FMI scales, for all participants, as a function of their burnout levels at baseline. The estimator for the latter effect was the mean value of delta 3 (immediately after vs. at 3-month follow-up) and its standard deviation.

Means were compared using a paired samples Student’s t-test. Percentages were compared using chi-square or Fisher’s exact test, depending on the number of participants considered. An analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed post-intervention if normality conditions were met. A repeated measures ANOVA was used to compare the three measures (before, immediately after, and at 3 months) if the conditions for applying it were met. Analyses are presented with and without stratification regarding the category of professionals (physicians, nurses, ambulance operators). Calculations were carried out with Microsoft Excel and STATA 16.0.

Ethical Considerations

All procedures were in accordance with the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki, revised in 2000. All participants gave written informed consent. The study was approved by the Committee of the Protection of Persons South-West and Overseas 4 (RIPH2, 2020-A03452-37) on December 21, 2020. All data were anonymized and processed according to current French legislation.

Results

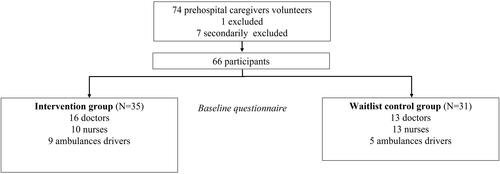

Seventy-four participants working for the PFB as ALS ambulances staff volunteered to follow the FIRECARE program. One participant was excluded because he was involved in developing the research protocol. Seven participants were excluded at a later date: five ended the program early because their shifts made it impossible to continue (6.76%), and baseline data were incomplete for two participants (2.7%). None of these participants left the program due to lack of interest or side effects. Sixty-six subjects were thus included. The flow chart process is represented in .

Following these exclusions, data from 66 participants were analyzed: 29 physicians (44%), 23 nurses (35%), and 14 ambulance operators (21%). Sociodemographic data are presented in .

Table 2. Sociodemographic data for total sample, intervention group and waitlist control group.

Baseline Data

At baseline, the subscales of the ProQOL score show that 40% of participants had low burnout scores (<23), and 60% had moderate burnout scores (23–41). Nobody had a high burnout score. Furthermore, 60% had low secondary stress scores, and 40% had moderate secondary stress scores. None of the participants had high secondary stress scores. Compassion satisfaction scores were as follows: 82% had moderate scores, and 18% had high scores. Data at inclusion are presented in .

Table 3. ProQOL-5 subscales and FMI score baseline data for intervention and control group.

Between-Group Comparisons (Intent to Treat)

There were no significant differences between waitlist control and intervention groups for sociodemographic variables. There were more participants with moderate burnout in the intervention group than in the control group, but the difference was not significant (p = 0.07). Furthermore, there were no significant differences for secondary stress (p = 0.29), compassion satisfaction (p = 0.19), or mindfulness (FMI total, acceptance, and presence) (p = 0.78). Data are presented in .

After the First Program (Intervention Group vs. Waitlist Control Groups, as Function of the Burnout Level at Baseline)

ProQOL-5’s Subscales (Primary Outcome)

Burnout

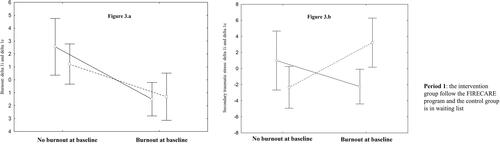

There was a significant post-intervention decrease in the burnout scores for all participants (intervention and waitlist control groups) compared to baseline (p = 0.0003; partial eta squared = 0.18). No difference was found between the intervention (delta 1i) and the control (delta1c) groups (p = 0.38), as shown in .

Figure 3. Immediate impact of the FIRECARE program on the burnout score (ProQOL-5) (a) and the secondary traumatic stress (b) according to the burnout level at baseline vs. waitlist control group. Delta 1i represents the value of the score measured after vs. before during period 1 for the experimental group. Delta 1c represents the value of the score during period 1 for the waitlist control group. F (1, 62) = 0.75, p = 0.38 (a); F (1, 62) = 9.02, p = 0.0038 (b).

Secondary Traumatic Stress

A Newman’s post-hoc analysis found that secondary traumatic stress scores fell among the burnout cluster of the intervention group, while scores for those in the burnout cluster of the waitlist control group increased (p = 0.003; partial eta squared = 0.12). Specifically, delta 1e was negative for the burnout cluster of the intervention group, while delta 1c was positive for the burnout cluster of the waitlist control group at the end of P1 as shown in .

Compassion Satisfaction

There was no effect on compassion satisfaction as a function of the burnout cluster at baseline (p = 0.16) or between the two groups (p = 0.12).

FMI

There were no significant differences in FMI delta scores according to the burnout level at baseline (acceptance: p = 0.45; presence: p = 0.36; total: p = 0.39) or between the two groups (delta 1i vs. delta 1c) (acceptance: p = 0.11; presence: p = 0.69; total p = 0.81).

Before-and-After FIRECARE Program (After Both Program)

ProQOL 5’s Subscales

Burnout

The second program tended to be more effective than the first (p = 0.05; partial eta squared = 0.06). Participants who were in the burnout cluster at baseline had significantly lower burnout scores after the program (negative delta 1, p = 0.006; partial eta squared = 0.11), while no difference was found between the two groups (p = 0.14). Although non-significant (p = 0.07), burnout scores for 13 of the 39 participants who were in the burnout cluster at baseline fell to normal levels after the FIRECARE program.

Secondary Traumatic Stress

No significant difference was found for secondary traumatic stress between burnout and no burnout clusters (p = 0.15), or between the period of the program (p = 0.13).

Compassion Satisfaction

Although non-significant, the second program tended to have more effect on satisfaction compassion (p = 0.08). No significative difference was found between the burnout and no burnout clusters (p = 0.39), or between the period of the program (p = 0.59).

FMI

Presence increased significantly during the first program (p = 0.05; partial eta squared = 0.05) for both burnout levels (p = 0.25), and both groups (p = 0.78). However, there were no significant differences on the acceptance subscale, either as a function of the burnout level at baseline (p = 0.16) or by group (p = 0.47).

Total scores on the FMI scale tended to increase after the program for the no burnout cluster (p = 0.07) for both groups (p = 0.24).

At 3-Month Follow-up (Before-and-After)

ProQOL 5’s Subscales

Burnout

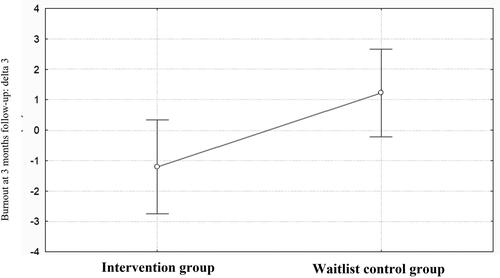

There was no difference in burnout at 3-month follow-up between the burnout and no burnout clusters (p = 0.5) or between the two groups (p = 0.4). At 3-month follow-up, nine participants with burnout had normalized their burnout scores, 22 non-burnouts and 29 burnouts remained stable, and six increased their burnout scores (p = 0.00001). If we do not consider the burnout cluster, burnout scores were significantly reduced their burnout score in the intervention group in comparison with the waitlist control group (p = 0.02; partial eta squared = 0.07), as shown in .

Figure 4. Three months follow-up impact of the FIRECARE program on burnout score (ProQOL-5) according to the period of the FIRECARE program. Delta 3 represents the value of the score measured after vs. at 3 months follow up of the training for intervention group and waitlist control group. F (1, 62) = 5.28, p = 0.024.

Secondary Stress and Compassion Satisfaction

There was no significant difference in secondary traumatic stress and compassion satisfaction between the burnout and no burnout clusters (p = 0.98, p = 0.39) or for the two groups (p = 0.45, p = 0.59).

FMI

Acceptance tended to have significantly increased among the burnout cluster (p = 0.07) for both groups. However, there were no significant differences on the acceptance subscale between the groups (p = 0.38), nor interactions between groups or periods (p = 0.32). The total FMI score significantly increased among participants in the burnout cluster (p = 0.05; partial eta squared = 0.05), and the second program seemed to be more effective (p = 0.06).

Mindfulness and Heart Coherence Training

During the FIRECARE program, 90% of participants in both groups, reported practicing the heart coherence training several times a week, and 84% reported practicing mindfulness meditation several times a week. At 3-month follow-up, 68% were still practicing the heart coherence training several times a week, and 27% were still practicing mindfulness meditation several times a week. A comparison of participants who no longer practiced meditation and those who did found a significant decrease in the total ProQOL 5 score (t = −2.58; p = 0.02), but no difference in the secondary stress score at 3-month follow-up (t = −1.96: p = 0.058).

Satisfaction

In total, 83% of participants were satisfied with the program, and 80% had recommended it to their colleagues and other PFB units.

Discussion

Our baseline data showed that 60% of participants had moderate burnout scores, and 40% had moderate secondary traumatic stress scores. None of the participants had high burnout or secondary traumatic stress scores. Moreover, all scored moderate (82%) or high (18%) for compassion satisfaction. These results contrast with the literature, where emergency department data report higher rates of burnout and secondary traumatic stress (Citation33). It is possible that in our study, either individuals with burnout did not volunteer to participate in the program, or that the unit’s operational demands are so intense that it is difficult for people with severe burnout to function. As mental health problems are sometimes perceived as a sign of weakness in the military (Citation34), it is also possible that personnel feared stigmatization by their peers, or by the institution (Citation25). A comparison of the intervention and waitlist control groups found that in both cases there was a significant decrease in the burnout scores for members of the burnout cluster. The effect sizes were high (Citation32). We hypothesize that the prospective new initiative, and the new institutional approach to caring for staff, had a placebo effect on the waitlist group, which influenced their burnout scores. This observation is consistent with several studies that show that institutional recognition influences well-being at work (Citation35).

However, it should be noted that secondary traumatic stress scores increased in the burnout cluster of the waitlist control group, while it fell in the burnout cluster of the intervention group. Our results regarding burnout should therefore be interpreted with caution, along with results for the other sub-scales of the ProQOL-5, especially with this population of first responders who are particularly exposed to repeated trauma (Citation36).

Burnout scores fell significantly among participants in the burnout cluster of both groups immediately after the program, and scores on the ProQOL-5 scale remained stable for asymptomatic (no burnout) participants. At 3-month follow-up, the first program was significantly more effective in reducing burnout for both burnout and no burnout clusters with medium effects size. Those who maintained their mindfulness practice significantly decreased their secondary traumatic stress scores. The literature suggests that the meditative practice should be consistent to be efficient and have an effect on brain plasticity (Citation37, Citation38). In our study, we observe that mindfulness practice had fallen significantly at 3-month follow-up compared to reported practice during the program (84 vs. 27%). This can explain the lack of a significant difference in burnout at 3-month follow-up.

Concerning the FMI score, while an immediate improvement in mindfulness was observed in asymptomatic subjects, it was also observed in symptomatic subjects at 3-month follow-up. We hypothesize that participants with higher burnout scores might find meditation practice more difficult and need more time to get into the program and observe an effect. This improvement is important, because some studies of first responders report that mindful awareness is associated with lower anxiety and depressive symptoms, and predicts better occupational health (lower burnout and higher compassion satisfaction) (Citation39, Citation40).

Of the 74 volunteers, only five left the program. Compared to previous studies, attendance remained very high, showing that the program is both feasible and acceptable for the target population (Citation41). Several studies report that caregivers find it difficult to maintain their participation due to their schedules and other restrictions, despite a clear interest in this type of intervention (Citation42). In our study, participants were able to follow the program in person, remotely, or by replaying videos, and this probably facilitated their participation. It should be noted that our program took place at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, when the health system and clinicians were under particular pressure, due to increased stress and uncertainty, and reduced social interactions. Several studies show that during the pandemic, MBSR training was an effective strategy to reduce distress among caregivers during periods of crisis (Citation43).

Another challenge was to encourage compliance with respect to mindfulness practice during and after the program. Only a few participants were familiar with mindfulness before the program began. Although the participants have been introduced to the idea during the initial presentation, they were surprised by the investment it required. Some of the participants reported that as they went deeper into the program, the absence of clear goals was very difficult. To carry out their mission, these prehospital caregivers are used to operating under pressure, in an emergency, making quick decisions, and pushing their physical and mental limits. Although many participants were looking for tools and solutions to better manage their stress, mindfulness is an invitation to slow down, to be aware, and to connect to one’s experience in the present, which many found difficult. Several studies have explored the effect of a shorter meditation intervention, with promising results (Citation10, Citation19, Citation43).

A recent meta-analysis underlines the importance of exploring potential participants’ needs before selecting the type of mindfulness intervention (Citation44). We anticipated this risk by supplementing the program with the heart coherence training and positive psychology workshops. Heart coherence training was used to help participants to become aware of their breathing. We provided the participants with a box designed for the army, pre-set to 3 min, which could be used discretely in all circumstances. At 3-month follow-up, 68% of participants still practiced the technique. Positive psychology workshops were a minor part of this intervention and mainly addressed the management of emotions. It could have been interesting, given the profile of participants, to increase the ratio of positive psychology workshops and work in more depth on emotion regulation, and strengthen individual and collective resources before the main program was launched (Citation45). Nevertheless, mindfulness interventions are not a miracle cure. Recent work within the wellness literature suggests that the end goal should be to achieve a culture of wellness, by addressing all aspects of the environment. In the medical context, reviews of burnout and wellness interventions in all specialties reveal that interventions that focus on system change, rather than individual physicians, are more successful (Citation46–48).

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. First, the sample was small, and we did not run a randomized controlled trial. The literature underlines the need to conduct large-scale randomized controlled trials to measure the effects of mindfulness interventions to increase methodological rigor, reduce bias, and limit the effects of nonspecific factors (e.g., time) (Citation44, Citation49). In our study, participants were not randomized between the two groups because of operational constraints during the COVID-19 pandemic. The distribution was made according to participants’ schedules, by their managers. Second, the control group was not a true control group, but a waitlist control group. Due to the large number of volunteers, it was difficult to not allow participants to follow the program for ethical reasons. Half of the overall group of volunteers were waitlisted during the first program and took part in the intervention immediately after the intervention group ended theirs.

Another limitation is that our study was conducted in only one French ALS ambulance unit, and there may have been emotional contamination between participants in the two groups who worked together. Also, there was a significant difference between the groups regarding the burnout cluster at baseline: specifically, there were more participants with burnout in the intervention group than in the waitlist control group. This may explain why the second FIRECARE intervention tended to be more effective than the first regarding the burnout scores and the compassion satisfaction scores. It is also possible that the instructor benefited from his experience of running the first program and improved his skills during the second program.

Nevertheless, our results showed that, at 3-month follow-up, the FIRECARE program was significantly more effective in reducing burnout in the intervention group, regardless of the baseline burnout level. As mentioned above, it is possible that there was a delayed effect of the program on symptomatic participants. As the first group had more symptomatic participants, it is possible that they needed more time to benefit from the program.

Despite these limitations, our results suggest that our combined intervention, based on MBCT, heart coherence training techniques, and positive psychology is a relevant approach to preventing or reducing burnout in first responders, such as prehospital caregivers. Our study is original in several ways. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study of French first responders, the first to combine mindfulness, heart coherence training, and positive psychology, and the first to explore the effects of a program as a function of baseline burnout symptoms. The program integrates evidence-based prevention principles by combining data from the literature, and the specific characteristics of a military, first responder population.

Conclusion

Burnout among health care professionals is a well-described pathology, especially in the emergency department, and the COVID-19 pandemic worsened it. The literature highlights several approaches to improve health care professional’s quality of professional life and psychological issues.

Here, we presented a combined intervention based on mindfulness, heart coherence training, and positive psychology proposed to the ALS ambulance staff of the PFB. Our results suggest that it is a relevant approach to preventing or reducing burnout, secondary traumatic stress, and improving mindfulness among prehospital emergency caregivers. These effects were maintained at 3-month follow-up. However, this type of intervention requires the physical and psychological availability of the participants and needs to be combined with other preventive approaches and institutional improvements for long-term efficiency.

Authors’ Contributions

LG wrote the manuscript. LG and MT processed data. MT contributed substantially to the revision of the manuscript. AD, RK, JD, MP, GB, ST, and BP take responsibility for the paper. All authors carefully read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the Paris Fire Brigade and the French Military Biomedical Research for their support.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Neto MLR, Almeida HG, Esmeraldo JD, Nobre CB, Pinheiro WR, de Oliveira CRT, Sousa IdC, Lima OMML, Lima NNR, Moreira MM, et al. When health professionals look death in the eye: the mental health of professionals who deal daily with the 2019 coronavirus outbreak. Psychiatry Res. 2020;288:112972. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112972.

- Di Giuseppe M, Nepa G, Prout TA, Albertini F, Marcelli S, Orrù G, Conversano C. Stress, burnout, and resilience among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 emergency: the role of defense mechanisms. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(10):5258. doi:10.3390/ijerph18105258.

- Chung AS. TF18 mindfulness in emergency medicine. Ann Emerg Med. 2015;66(4):S162. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2015.07.487.

- Kemper KJ, Khirallah M. Acute effects of online mind-body skills training on resilience, mindfulness, and empathy. J Evid Based Complementary Altern Med. 2015;20(4):247–253. doi:10.1177/2156587215575816.

- Thirioux B, Birault F, Jaafari N. Empathy is a protective factor of burnout in physicians: new neuro-phenomenological hypotheses regarding empathy and sympathy in care relationship. Front Psychol. 2016;7:763. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00763.

- Neff KD. The role of self-compassion in development: a healthier way to relate to oneself. Hum Dev. 2009;52(4):211–214. doi:10.1159/000215071.

- Britt TW, Shuffler ML, Pegram RL, Xoxakos P, Rosopa PJ, Hirsh E, Jackson W. Job demands and resources among healthcare professionals during virus pandemics: a review and examination of fluctuations in mental health strain during COVID‐19. Appl Psychol. 2021;70(1):120–149. doi:10.1111/apps.12304.

- Lomas T, Medina JC, Ivtzan I, Rupprecht S, Eiroa-Orosa FJ. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of mindfulness-based interventions on the well-being of healthcare professionals. Mindfulness. 2019;10(7):1193–1216. doi:10.1007/s12671-018-1062-5.

- Job demands-resources theory and self-regulation: new explanations and remedies for job burnout [Internet]. [cité 2023 mars 20]. Disponible sur: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32856957/

- Xu HG, Tuckett A, Kynoch K, Eley R. A mobile mindfulness intervention for emergency department staff to improve stress and wellbeing: a qualitative study. Int Emerg Nurs. 2021;58:101039. doi:10.1016/j.ienj.2021.101039.

- Botha E, Gwin T, Purpora C. The effectiveness of mindfulness based programs in reducing stress experienced by nurses in adult hospital settings: a systematic review of quantitative evidence protocol. JBI Database Syst Rev Implement Rep. 2015;13(10):21–29. doi:10.11124/jbisrir-2015-2380.

- Marmar CR, McCaslin SE, Metzler TJ, Best S, Weiss DS, Fagan J, Liberman A, Pole N, Otte C, Yehuda R, et al. Predictors of posttraumatic stress in police and other first responders. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1071(1):1–18. doi:10.1196/annals.1364.001.

- Quevillon RP, Gray BL, Erickson SE, Gonzalez ED, Jacobs GA. Helping the helpers: assisting staff and volunteer workers before, during, and after disaster relief operations. J Clin Psychol. 2016;72(12):1348–1363. doi:10.1002/jclp.22336.

- Gerace A, Rigney G. Considering the relationship between sleep and empathy and compassion in mental health nurses: it’s time. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2020;29(5):1002–1010. doi:10.1111/inm.12734.

- Lamblin A, Derkenne C, Trousselard M, Einaudi MA. Ethical challenges faced by French military doctors deployed in the Sahel (Operation Barkhane): a qualitative study. BMC Med Ethics. 2021;22(1):153. doi:10.1186/s12910-021-00723-2.

- Paulson S, Davidson R, Jha A, Kabat-Zinn J. Becoming conscious: the science of mindfulness. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2013;1303:87–104. doi:10.1111/nyas.12203.

- Braun SE, Kinser PA, Rybarczyk B. Can mindfulness in health care professionals improve patient care? An integrative review and proposed model. Transl Behav Med. 2019;9(2):187–201. doi:10.1093/tbm/iby059.

- Denkova E, Zanesco AP, Rogers SL, Jha AP. Is resilience trainable? An initial study comparing mindfulness and relaxation training in firefighters. Psychiatry Res. 2020;285:112794. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112794.

- Pérula-de Torres L-A, Atalaya JCV-M, García-Campayo J, Roldán-Villalobos A, Magallón-Botaya R, Bartolomé-Moreno C, Moreno-Martos H, Melús-Palazón E, Liétor-Villajos N, Valverde-Bolívar FJ, et al. Controlled clinical trial comparing the effectiveness of a mindfulness and self-compassion 4-session programme versus an 8-session programme to reduce work stress and burnout in family and community medicine physicians and nurses: MINDUUDD study protocol. BMC Fam Pract. 2019;20(1):24. doi:10.1186/s12875-019-0913-z.

- Figley CR. Compassion fatigue: psychotherapists’ chronic lack of self care. J Clin Psychol. 2002;58(11):1433–1441. doi:10.1002/jclp.10090.

- Zhang YY, Zhang C, Han XR, Li W, Wang YL. Determinants of compassion satisfaction, compassion fatigue and burn out in nursing: a correlative meta-analysis. Medicine. 2018;97(26):e11086. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000011086.

- Freudenberger H. Staff burn‐out. J Soc Issues. 1974;30(1):159–165. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4560.1974.tb00706.x.

- Bliese PD, Adler AB, Castro CA, éditeurs. Research-based preventive mental health care strategies in the military. In: Deployment psychology: evidence-based strategies to promote mental health in the military. Washington (DC): American Psychological Association; 2011. p. 103–124.

- Adler AB, Bliese PD, Castro CA. Deployment psychology: evidence-based strategies to promote mental health in the military. Washington (DC): American Psychological Association; 2011. Vol. xii, p. 294.

- Britt TW, Jennings KS, Cheung JH, Pury CLS, Zinzow HM. The role of different stigma perceptions in treatment seeking and dropout among active duty military personnel. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2015;38(2):142–149. doi:10.1037/prj0000120.

- McCraty R, Zayas MA. Cardiac coherence, self-regulation, autonomic stability, and psychosocial well-being. Front Psychol. 2014;5:1090. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01090.

- Gable SL, Haidt J. What (and why) is positive psychology? [Internet]. 2005 [cité 2023 mars 22]. Disponible sur: https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.9.2.103

- Stamm B. The concise ProQOL manual: the concise manual for the Professional Quality of Life Scale. 2nd ed. Pocatello; 2010 [accessed 2023 Sep 14]. http://ProQOL.org/uploads/ProQOL_Concise_2ndEd_12-2010.pdf

- Walach H, Buchheld N, Buttenmüller V, Kleinknecht N, Schmidt S. Measuring mindfulness–The Freiburg Mindfulness Inventory (FMI). Pers Individ Differ. 2006;40(8):1543–1555. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2005.11.025.

- Trousselard M, Steiler D, Raphel C, Cian C, Duymedjian R, Claverie D, Canini F. Validation of a French version of the Freiburg Mindfulness Inventory-short version: relationships between mindfulness and stress in an adult population. Biopsychosoc Med. 2010;4(1):8. doi:10.1186/1751-0759-4-8.

- Dethoor M, Vialatte F, Martinelli M, Peri P, Lançon C, Trousselard M. Predictive factors of response to mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) for patients with depressive symptoms: the machine learning’s point of view. OBM Integr Complement Med. 2022;7(4):1–31. doi:10.21926/obm.icm.2204058.

- Lakens D. Calculating and reporting effect sizes to facilitate cumulative science: a practical primer for t-tests and ANOVAs. Front Psychol. 2013;4:863. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00863.

- Petrino R, Riesgo LGC, Yilmaz B. Burnout in emergency medicine professionals after 2 years of the COVID-19 pandemic: a threat to the healthcare system? Eur J Emerg Med. 2022;29(4):279–284. doi:10.1097/MEJ.0000000000000952.

- Nash WP, Silva C, Litz B. The historic origins of military and veteran mental health stigma and the stress injury model as a means to reduce it. Psychiatr Ann. 2009;39(8):789–794. doi:10.3928/00485713-20090728-05.

- Munn LT, Huffman CS, Connor CD, Swick M, Danhauer SC, Gibbs MA. A qualitative exploration of the National Academy of Medicine model of well-being and resilience among healthcare workers during COVID-19. J Adv Nurs. 2022;78(8):2561–2574. doi:10.1111/jan.15215.

- Jahnke SA, Poston WSC, Haddock CK, Murphy B. Firefighting and mental health: experiences of repeated exposure to trauma. Work. 2016;53(4):737–744. doi:10.3233/WOR-162255.

- Lutz A, Greischar LL, Rawlings NB, Ricard M, Davidson RJ. Long-term meditators self-induce high-amplitude gamma synchrony during mental practice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(46):16369–16373. doi:10.1073/pnas.0407401101.

- Fox KC, Nijeboer S, Dixon ML, Floman JL, Ellamil M, Rumak SP, Sedlmeier P, Christoff K. Is meditation associated with altered brain structure? A systematic review and meta-analysis of morphometric neuroimaging in meditation practitioners. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2014;43:48–73. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.03.016.

- McDonald MA, Yang Y, Lancaster CL. The association of distress tolerance and mindful awareness with mental health in first responders. Psychol Serv. 2022;19(Suppl 1):34–44. doi:10.1037/ser0000588.

- Westphal M, Bingisser M-B, Feng T, Wall M, Blakley E, Bingisser R, Kleim B. Protective benefits of mindfulness in emergency room personnel. J Affect Disord. 2015;175:79–85. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2014.12.038.

- Burton A, Burgess C, Dean S, Koutsopoulou GZ, Hugh-Jones S. How effective are mindfulness-based interventions for reducing stress among healthcare professionals? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Stress Health. 2017;33(1):3–13. doi:10.1002/smi.2673.

- Klein A, Taieb O, Xavier S, Baubet T, Reyre A. The benefits of mindfulness-based interventions on burnout among health professionals: a systematic review. Explore. 2020;16(1):35–43. doi:10.1016/j.explore.2019.09.002.

- Marotta M, Gorini F, Parlanti A, Berti S, Vassalle C. Effect of mindfulness-based stress reduction on the well-being, burnout and stress of Italian healthcare professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Clin Med. 2022;11(11):3136. doi:10.3390/jcm11113136.

- Spinelli C, Wisener M, Khoury B. Mindfulness training for healthcare professionals and trainees: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Psychosom Res. 2019;120:29–38. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2019.03.003.

- Salvarani V, Rampoldi G, Ardenghi S, Bani M, Blasi P, Ausili D, Di Mauro S, Strepparava MG. Protecting emergency room nurses from burnout: the role of dispositional mindfulness, emotion regulation and empathy. J Nurs Manag. 2019;27(4):765–774. doi:10.1111/jonm.12771.

- Yester M. Work-life balance, burnout, and physician wellness. Health Care Manag. 2019;38(3):239–246. doi:10.1097/HCM.0000000000000277.

- Stehman CR, Clark RL, Purpura A, Kellogg AR. Wellness: combating burnout and its consequences in emergency medicine. West J Emerg Med. 2020;21(3):555–565.

- Samu urgences de France. RÉSULTATS DE L’ENQUÊTE SUdF SITUATION DES URGENCES EN JUILLET 2022; 2022. Disponible sur: https://www.samu-urgences-de-france.fr/medias/files/sudf_enquete_202207_resultats_VF.pdf

- Goldberg SB, Riordan KM, Sun S, Davidson RJ. The empirical status of mindfulness-based interventions: a systematic review of 44 meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2022;17(1):108–130. doi:10.1177/1745691620968771.