Abstract

Introduction

Emergency airway management is a common and critical task EMS clinicians perform in the prehospital setting. A new set of evidence-based guidelines (EBG) was developed to assist in prehospital airway management decision-making. We aim to describe the methods used to develop these EBGs.

Methods

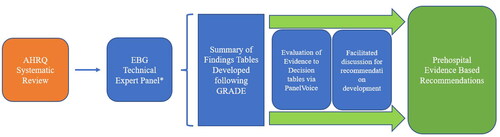

The EBG development process leveraged the four key questions from a prior systematic review conducted by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) to develop 22 different population, intervention, comparison, and outcome (PICO) questions. Evidence was evaluated using the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) framework and tabulated into the summary of findings tables. The technical expert panel then used a rigorous systematic method to generate evidence to decision tables, including leveraging the PanelVoice function of GRADEpro. This process involved a review of the summary of findings tables, asynchronous member judging, and online facilitated panel discussions to generate final consensus-based recommendations.

Results

The panel completed the described work product from September 2022 to April 2023. A total of 17 summary of findings tables and 16 evidence to decision tables were generated through this process. For these recommendations, the overall certainty in evidence was “very low” or “low,” data for decisions on cost-effectiveness and equity were lacking, and feasibility was rated well across all categories. Based on the evidence, 16 “conditional recommendations” were made, with six PICO questions lacking sufficient evidence to generate recommendations.

Conclusion

The EBGs for prehospital airway management were developed by leveraging validated techniques, including the GRADE methodology and a rigorous systematic approach to consensus building to identify treatment recommendations. This process allowed the mitigation of many virtual and electronic communication confounders while managing several PICO questions to be evaluated consistently. Recognizing the increased need for rigorous evidence evaluation and recommendation development, this approach allows for transparency in the development processes and may inform future guideline development.

Introduction

Airway management in the prehospital setting varies depending on EMS clinician education, scope of practice, clinical guidelines, patient presentation, and protocols (Citation1, Citation2). Previous research suggests that prehospital airway management success rates and patient outcomes could be optimized (Citation3–5). The reasons for variability in performance are multifactorial and may be due to environment, patient condition, training, experience, and device choice (Citation3). These potential variabilities in practice and outcomes necessitate the development of up-to-date and evidence-based clinical guidelines (EBG) that may assist EMS clinicians in choosing the most appropriate airway management approach. With this in mind, developing a new EBG for prehospital airway management was partly supported by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA), the Office of Emergency Medical Services, and the National Association of State EMS Officials (NASEMSO).

As part of this project, this companion manuscript to the EBG paper describes the detailed methodology to develop these evidence-based recommendations, including using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) methodology for rigorous evidence evaluation followed by a systematic approach for recommendation development (Citation6, Citation7).

Methods

Study Plan and Protocol

This project aimed to develop evidence-based recommendations and treatment guidelines for prehospital airway management. This study began with a systematic review of existing literature by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) and advanced with the expertise of a technical expert panel (Citation8). Through a funded partnership with NHTSA, the AHRQ identified prehospital airway management literature to help inform an evidence-based approach to prehospital airway management. The AHRQ published its findings through the Pacific Northwest Evidence-Based Practices Center (Contract No. 290-2015-00009-I) (Citation2).

The AHRQ review categorized airway management interventions for adult and pediatric populations with four conditions: out-of-hospital cardiac arrest, medical, mixed emergencies, and trauma. Airway management interventions included bag-valve-mask only (BVM), supraglottic airway devices (SGA), and endotracheal intubation (ETI). Three key questions for these approaches generated PICO (population, intervention, comparison, outcome) questions: BVM-only compared to SGA, BVM-only compared to ETI, and SGA compared to ETI (). PICO questions were developed for evaluation by the panel for each combination of these populations and interventions. These airway intervention outcomes were categorized into the highest-priority patient health outcomes: survival and neurological function. Intermediate-level outcomes, considered a second priority, were first-pass success, overall success, and return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC). The fourth key question evaluated four technique modifiers among mixed emergencies: no medication vs. rapid sequence intubation (RSI), sedation-assisted intubation vs. RSI, no medication vs. sedation-assisted intubation, and direct laryngoscopy (DL) vs. video laryngoscopy (VL). Similar outcomes were evaluated.

Table 1. Generated PICOs (population, intervention, comparison, outcome) categorized by key question.

The panel, identified by NASEMSO, consisted of adult and pediatric airway management experts, EMS physicians, medical directors, clinicians, educators, researchers, and an evidence-based guideline methodologist to provide a holistic approach to guideline development. This selection process allowed the TEP members to have direct experience with prehospital airway management and, as members of the target user population, to understand the views and preferences of EMS clinicians. In addition, this TEP experiences a high level of knowledge to make recommendations for better outcomes for our target population, the patient. The panel used as its foundation the work conducted by the AHRQ (), taking information from the systematic review and adding expert-level context to develop recommendations. The research plan included regular weekly synchronous online meetings to discuss and develop recommendations since face-to-face meetings may not have been possible due to pandemic restrictions. The panel evaluated the 22 PICO questions in the AHRQ review and attempted to generate associated evidence for decision tables, leading to the recommendations.

Details of the AHRQ Review

The AHRQ review was a detailed search of Ovid® MEDLINE®, CINAHL®, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, and Scopus®) from 1990 to September 2020, including the reference lists. The developed search strategies, noted in Supplementary Appendix 3, include search terms and completion dates. The AHRQ review document details how specific articles were identified, screened, and retained (Citation8).

Developing Summary of Findings Tables from AHRQ Review

Through an extensive literature search described by the AHRQ, the systematic review yielded 99 studies, including 22 randomized controlled trials and 77 observational evaluations. The AHRQ then used a validated strength of evidence grading process to develop PICO questions comparing BVM to ETI, BVM to SGA, ETI to SGA, no medication to RSI, sedation-assisted intubation to RSI, no medication to sedation-assisted intubation, and DL to VL (). This grading process analyzed the included studies for consistency, precision, and directness, allowing for a certainty assessment to be generated.

The strength of evidence grading, conducted by the AHRQ, was transposed as the strength of certainty for all generated PICO questions and populated into the summary of findings tables using the GRADEPro Guideline Development Tool (GRADEPro GDT) (Citation6). One author (CBG) generated all summary of findings tables, and two authors (JRP, ARP) verified the information for accuracy, allowing the panel to receive consistent information. Individual and pooled analysis tables from the systematic review were added to each summary of findings table.

Applying a Systematic Method to Developing Recommendations

Panel members were emailed the summary of findings tables and all AHRQ-relevant literature for each PICO question. Then, over ∼1 week, the panel members were individually tasked with evaluating the evidence and completing the PanelVoice portion in GRADEpro to share their expert opinions and recommendations. Finally, in a synchronous, online video conferencing format, the panel reviewed the evidence and the panel members’ collective comments submitted in the PanelVoice. The PanelVoice portion in GRADEpro uses 12 criteria to inform each recommendation: problem, desirable effects, undesirable effects, certainty in evidence, values, balance of effects, resources required, certainty in evidence of required resources, cost-effectiveness, equity, acceptability, and feasibility (Citation8). These 12 criteria allowed the TEP to integrate independently, for each PICO question reviewed, the benefits and harms of each intervention as well as the views and preferences of the EMS clinicians regarding the airway interventions. Detailed explanations for each criterion can be found in the GRADE methodology handbook (Citation6).

The evidence to decision tables, prepared using GRADEPro GDT, provided a structured approach that allowed the panel members’ judgments and reasoning for each recommendation to be precise and transparent for the target user audience (Citation9). To support the panel in making informed judgments through facilitated online discussions, associated information for each of the 12 criteria was added to the evidence to decision tables along with some studies in the systematic review and PubMed-identified studies not in the systematic review. However, if no relevant evidence was found, all details, including subject matter expert opinions used to make a judgment, were included in the additional considerations section (Citation9). Contextual additions were meant to supplement, not dictate, discussion regarding each PICO question. During each online meeting, a GRADE methodologist (ESL) facilitated the discussion to evaluate the comments on the 12 criteria and assist panel members with making final recommendations about each PICO question. In addition, panel members were encouraged to discuss evidence through video and live chat functions to be inclusive and balanced for all participants. Final recommendations were developed after a review of the evidence, a summary of findings tables, asynchronous member judging using PanelVoice, and facilitated panel discussions. During facilitated discussions, panel consensus was defined as the agreement of >85% of panel members. Any opposing views were respected and noted in the evidence to the decision table.

Results

Utilizing this systematic approach, and with support from NASEMSO staff, the panel evaluated 22 PICO questions during twenty online and one in-person meeting from September 2022 to April 2023. All aspects of this project were conducted electronically (by email or internet) with regularly scheduled virtual meetings for the summary of findings table review and evidence to decision table generation, except for one face-to-face meeting at NAEMSP in Tampa, Florida. Descriptions of the panel members and their conflicts of interest are included in the recommendations manuscript (Citation7).

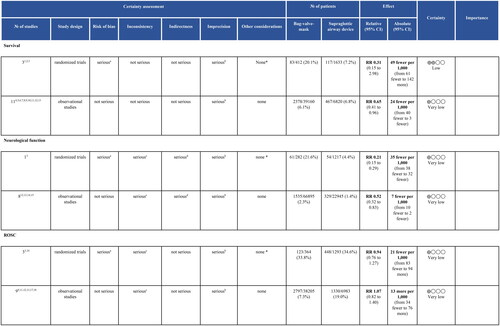

Summary of findings tables were generated for 17 PICO questions identified in the AHRQ systematic review. Unfortunately, five PICO questions were not evaluated using the GRADE methodology due to a lack of literature presented with those comparisons. shows a portion of the summary of findings table for comparing BVM vs. SGA in airway management of pediatrics in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA). The rest of the outcomes for this PICO question, and all the other summary of findings tables, are available in Supplementary Appendix 1.

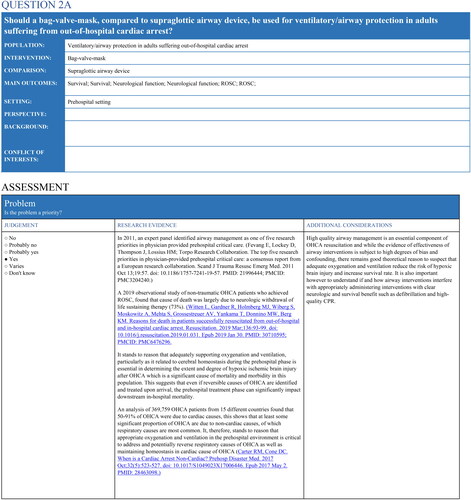

From the generated summary of findings tables, the panel conducted asynchronous PanelVoice evaluations and online facilitated discussions by the methodologist before developing the evidence to decision tables. shows a portion of the evidence to decision table comparing BVM to SGA among adults in OHCA. The panel generated 16 evidence to decision tables from the summary of findings tables. Additionally, even though some evidence was presented for one PICO, the panel felt the evidence was inappropriate to answer this PICO question, and no recommendation was generated. All evidence to decision tables are reported in Supplementary Appendix 2.

Figure 3. Abbreviated evidence to decision table for bag-valve-mask vs. supraglottic airway for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest.

All included studies were conducted between 1992 and 2020, with 55% of studies conducted between 2014 and 2020. Certainty of evidence was primarily “very low” or “low,” leading to increased use of the selection “don’t know” among the balance of effects and resources required. Uncertainty, via lack of studies, affected certainty in evidence of required resources and cost-effectiveness. The lack of data for equity decisions also led to an increased judgment of “don’t know.” Feasibility was well represented, with most judgments consisting of “yes” or “probably yes.” Sixteen “conditional recommendations” and six “no recommendations because of lacking evidence” were generated. A separate manuscript contains the details of each recommendation for dissemination to EMS clinicians (Citation7).

Discussion

In this evaluation, we leveraged established EBG development techniques using the GRADEpro system and a rigorous systematic approach to developing treatment recommendations for prehospital airway management. Specifically, we used the PanelVoice function of the GRADEpro GDT for the development of each treatment recommendation. This process started with the asynchronous review and judging by panel members, followed by a facilitated online group discussion for final treatment recommendation development. This process minimized the panel’s overall cognitive burden in managing each PICO question. This approach was necessary because members were tasked with developing recommendations for 22 PICO questions, most with more than one key outcome, and reviewing the results of many detailed evidence evaluations over their time on the panel.

Allowing the panel members time to review and comment on the evidence before meeting online allowed participating members to share their opinions without bias or pressure from other group members. The online setting allowed the panel to debate using the evidence to help eliminate any bias or confounding arising from previous unfounded beliefs. In addition, this approach is a good model for developing other prehospital EBGs for which the cognitive burden and pressure for the expert panel may be significant or as an alternative to in-person meetings in which multiple face-to-face meetings are not possible.

Many techniques used in this EBG development process are similar to those of other previously developed EBGs and have been applied in previously developed prehospital care guidelines (Citation3, Citation6). For example, many other organizations have used the GRADE methodology, including the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation, the American Heart Association, and the American College of Chest Physicians (Citation10–17). The assembled experts in those studies generated a summary of findings tables using the GRADE methodology and allowed for developing recommendations tables.

Specific to airway management, the GRADE methodology has been previously applied to a 2018 analysis of the difficulty of intubation and extubation in anesthesia (Citation18). In this EBG process, the authors assembled a panel of experts who identified evidence related to their chosen PICO questions. Contrasting this approach to the methodology used to generate our recommendations, the presence of an AHRQ systematic review and generation of evidence to decision tables increases the methodological rigor and improves process transparency.

Benefits of this technique include allowing for previously unavailable guideline transparency while managing competing interests (Citation6). Further, it provides for future decision-making in this area to understand the panel’s perspective, mindset, and motivations with clear documentation of how the decisions were derived. Finally, the asynchronous judging by panel members, with the ability to describe their positions, enables them to safely express views that may be in the minority, ensuring all voices are heard and not lost by the effect of other influential members or ideas. Given the speed of new knowledge creation and ongoing trials related to prehospital airway management, we recommend a guideline update be considered within 2–5 years. Such an update should include a systematic review revision of relevant literature performed by AHRQ.

Limitations

Several challenges were faced in using this process for guideline development. Since the panel did not convene in person, except at the NAEMSP conference in January 2023, held in Tampa, Florida, working relationships for this project were formed only through email and online meetings. Members may have had varying availability to be present at all virtual meetings, so some panel members’ opinions or voices may not have been heard. However, using PanelVoice in this process may have mitigated this effect. Second, due to the design of the AHRQ systematic review, the panel was required to GRADE all the PICO questions evaluated. This step was important so the panel had similar data to develop evidence to decision tables for recommendations. Third, we focused our evaluation and work on supporting the EMS clinicians’ decision-making for airway management. However, we did not have a representative of the target population, the patient, on the TEP. Finally, through the evaluation done by the group, we discovered a limited body of high-quality literature that directly addressed the prehospital questions evaluated by the panel. Of the 22 PICO questions addressed, eleven had “very low” certainty in evidence, five with “no evidence,” four with “low” certainty in evidence, one with “low–moderate,” and one had evidence the panel could not rely on (Supplementary Appendix 1). Certainty of evidence drivers included literature directness to prehospital care, emergency department-conducted studies, and data precision.

Conclusion

In this evaluation, we leveraged established EBG development techniques, the GRADE framework, and a systematic process to develop treatment recommendations for prehospital airway management. This process included individual asynchronous reviews of the evidence, voting, online video meetings, and the GRADE recommendation system to mitigate potential bias in recommendation development. Future guideline processes should consider this approach to increase transparency in the recommendation development processes.

Author Contributions

CBG, JRP, and ARP conceived, designed, and collected the data. All authors analyzed the data. CBG, JRP, ESL, and ARP drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed substantially to the interpretation of the data and revision of the manuscript. CBG takes responsibility for the paper as a whole.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (369.2 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (93.4 KB)Acknowledgments

This document’s contents are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the U.S. government’s official views or an endorsement. For more information, please visit EMS.gov and HRSA.gov.

Disclosure Statement

Christopher Gage, Jonathan Powell, Nicole Bossom, Remle Crowe, Kyle Guilde, Matthew Yeunge, Davis Maclean, Lorin Browne, Eddy Lang, and Ashish Panchal report no potential conflicts of interest. Jeffrey L. Jarvis and J. Matthew Sholl report receiving honoraria from NASEMSO for their work as co-principal investigators on this project.

Additional information

Funding

References

- National Association of State EMS Officials (NASEMSO). National Model EMS Clinical Guidelines. National Association of State EMS Officials (NASEMSO); 2022 Mar 11 [accessed 2022 Nov 21]. https://nasemso.org/wp-content/uploads/National-Model-EMS-Clinical-Guidelines_2022.pdf.

- Ångerman S, Kirves H, Nurmi J. A before-and-after observational study of a protocol for use of the C-MAC videolaryngoscope with a Frova introducer in prehospital rapid sequence intubation. Anaesthesia. 2018;73(3):348–55. doi:10.1111/anae.14182.

- Prekker ME, Kwok H, Shin J, Carlbom D, Grabinsky A, Rea TD. The process of prehospital airway management. Crit Care Med. 2014;42(6):1372–8. doi:10.1097/ccm.0000000000000213.

- Davis DP, Bosson N, Guyette FX, Wolfe A, Bobrow BJ, Olvera D, Walker RG, Levy M. Optimizing physiology during prehospital airway management: an NAEMSP position statement and resource document. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2022;26(sup1):72–9. doi:10.1080/10903127.2021.1992056.

- Van Schuppen H, Boomars R, Kooij FO, den Tex P, Koster RW, Hollmann MW. Optimizing airway management and ventilation during prehospital advanced life support in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: a narrative review. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2021;35(1):67–82. doi:10.1016/j.bpa.2020.11.003.

- Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, Oxman A. GRADE handbook for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. The GRADE Working Group; 2013. https://www.gradepro.org/

- Jarvis J. Evidence-based guideline for prehospital airway management. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2023. doi:10.1080/10903127.2023.2281363.

- Carney N, Totten AM, Cheney T, Jungbauer R, Neth MR, Weeks C, Davis-O’Reilly C, Fu R, Yu Y, Chou R, et al. Prehospital airway management. A systematic review. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2022;26(5):716–727. doi:10.1080/10903127.2021.1940400.

- Alonso-Coello P, Oxman AD, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Vandvik PO, Meerpohl J, et al. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 2: clinical practice guidelines. BMJ. 2016;353:i2089. doi:10.1136/bmj.i2089.

- Magid DJ, Aziz K, Cheng A, Hazinski MF, Hoover AV, Mahgoub M, Panchal AR, Sasson C, Topjian AA, Rodriguez AJ, et al. Part 2: evidence evaluation and guidelines development: 2020 American Heart Association guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation. 2020;142(16_suppl_2):S358–S365. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000898.

- Nolan JP, Maconochie I, Soar J, Olasveengen TM, Greif R, Wyckoff MH, Singletary EM, Aickin R, Berg KM, Mancini ME, et al. Executive summary: 2020 international consensus on cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care science with treatment recommendations. Circulation. 2020;142(16_suppl_1):S2–S27. doi:10.1161/cir.0000000000000890.

- Smith MP, Lown M, Singh S, Ireland B, Hill AT, Linder JA, Irwin RS, CHEST Expert Cough Panel. Acute cough due to acute bronchitis in immunocompetent adult outpatients: CHEST expert panel report. Chest. 2020;157(5):1256–65. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2020.01.044.

- Gausche-Hill M, Brown KM, Oliver ZJ, Sasson C, Dayan PS, Eschmann NM, Weik TS, Lawner BJ, Sahni R, Falck-Ytter Y, et al. An evidence-based guideline for prehospital analgesia in trauma. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2014;18 Suppl 1(sup1):25–34. doi:10.3109/10903127.2013.844873.

- Lipp C, Dhaliwal R, Lang E. Analgesia in the emergency department: a GRADE-based evaluation of research evidence and recommendations for practice. Crit Care. 2013;17(2):212. doi:10.1186/cc12521.

- Shah MI, Macias CG, Dayan PS, Weik TS, Brown KM, Fuchs SM, Fallat ME, Wright JL, Lang ES. An evidence-based guideline for pediatric prehospital seizure management using GRADE methodology. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2014;18 Suppl 1(sup1):15–24. doi:10.3109/10903127.2013.844874.

- Thomas SH, Brown KM, Oliver ZJ, Spaite DW, Lawner BJ, Sahni R, Weik TS, Falck-Ytter Y, Wright JL, Lang ES. An evidence-based guideline for the air medical transportation of prehospital trauma patients. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2014;18 Suppl 1(sup1):35–44. doi:10.3109/10903127.2013.844872.

- Patterson PD, Higgins JS, Van Dongen HPA, Buysse DJ, Thackery RW, Kupas DF, Becker DS, Dean BE, Lindbeck GH, Guyette FX, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for fatigue risk management in emergency medical services. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2018;22(sup1):89–101. doi:10.1080/10903127.2017.1376137.

- Langeron O, Bourgain JL, Francon D, Amour J, Baillard C, Bouroche G, Chollet Rivier M, Lenfant F, Plaud B, Schoettker P, et al. Difficult intubation and extubation in adult anaesthesia. Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med. 2018;37(6):639–51. doi:10.1016/j.accpm.2018.03.013.