Abstract

Background: How we identify ourselves is strongly related to employment. Young adults are a vulnerable group with regard to entering the Labor market. If they also have mental health problems, entering becomes more difficult and increases risk of early marginalization. Nevertheless, working can be essential for personal recovery process.

Aims: To explore experiences of young adults with mental health problems who are starting to work, with a focus on the process of developing work identity.

Methods: Grounded theory design was used. The data collection consisted of 13 in-depth interviews with young adults with mental health problems aged 19–26 years, who had worked for at least three months.

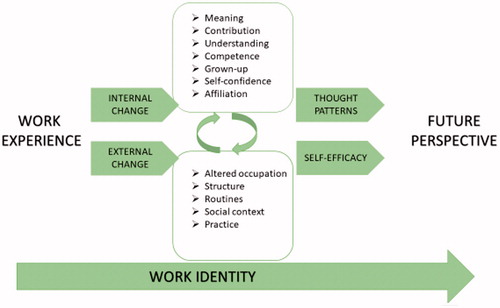

Results: The experience of starting to work contributed to a process of internal and external change, new feelings, challenges, and understanding of the surrounding world. Former negative thought patterns became more positive. New roles and occupational patterns were developed and altered views on abilities, and thus self-efficacy. This development contributed to a work identity, and new directions in life.

Conclusions: There is therapeutic potential in supporting work identity development, and this support can empower the personal recovery process for young adults.

Introduction

In Sweden, mental health problems are the most common reason for sick-leave among women and second among men [Citation1]. Mental health (MH) is an overarching concept that includes various conditions, from common mental disorders such as generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) and depression for example, to more serious mental disorders such as schizophrenia and manic depressive disorders which conditions is associated with serious functional impairments [Citation2]. Among young adults, MH problems are serious public health challenges that influence school status, transition to work, and career development [Citation3]. Nevertheless, work is a usual goal for most persons with MH problems [Citation4,Citation5], and has an essential meaning for personal recovery [Citation6–9]. Most interventions focus on the treatment of MH disease and symptoms [Citation10], and not on promotion of resources and abilities [Citation11]. Less than 23% of persons with long-lasting MH problems in Sweden report engaging in regular work [Citation12]. People with long-term unemployment belongs to one of six socially marginalized groups in Europe, of being socially isolated and not having the ability to fully participate in society [Citation13]. To combat unemployment among persons with MH problems, we should focus on young adults who have not yet been marginalized to a socially deprived living situation. With early interventions, we may counteract marginalization and support the critical passage of occupation development during transition into adulthood. Increased awareness and knowledge about how young adults with MH problem acquire work and develop work identity may improve the clinical reasoning among occupational therapists and other professionals in MH services and vocational rehabilitation.

Risk for MH problem is higher among persons who are poor, homeless, unemployed, refugees, have low education, and are children or adolescents [Citation14]. Accordingly, young adults may be seen as a high-risk group. During the 21st century, MH problems among young adults in Sweden increased by about one third. In 2011, seven percent of men and ten percent of women aged 18–24 years had contact with MH services. Overall, 79 500 young adults needed some form of psychiatric treatment in Sweden [Citation3]. Young adults are considered a sensitive group with regard to MH and entering the Labor market [Citation1]. MH is viewed as including mental, psychological, and social well-being. MH affects how we think, feel, act, and determines how we handle stress, relate to others, and make choices [Citation14]. MH problems at a young age has consequences later in life, including level of education attained and working life [Citation3]. Further, lack of work experience can lead to loss of roles and social status [Citation15], as well as difficulties in identifying oneself with the work role [Citation7]. In turn, if young adults with MH problems have few opportunities to develop work identity, setting work-related goals becomes difficult. Occupational therapists and other professionals have the important task of recognizing and counteracting the difficulties that young persons may have in building an identity and future career [Citation4,Citation7].

The development of work identity can be understood from different recovery perspectives. Traditionally, MH services and vocational rehabilitation are based on a clinical recovery perspective [Citation16] that focuses primarily on improvement of function and symptoms. In this study, we emphasize a personal recovery perspective, which includes the possibilities of having a meaningful life and developing meaningful life roles despite having MH symptoms and problems [Citation17]. This perspective entails a person-centred and personal recovery-oriented practice that includes the individual needs with regard to housing, education, work, and social life. What is important is to provide individuals with opportunities for community integration, normative life roles [Citation17–19], and goals for personal recovery [Citation7–9,Citation19], in contrast to them being subjected to a marginalized situation. Two randomized controlled trials show that persons with MH problems, who received person-centred support of an integrated MH and vocational rehabilitation service, gained and kept their employment to a larger extent than the controls who received traditional stepwise and separated services. Moreover, the intervention group had a higher sense of empowerment, fewer symptoms, and higher levels of community integration [Citation20,Citation21]. Qualitative research points in the same direction [Citation11,Citation22,Citation23]. An integration of mental health and vocational rehabilitation services that lead to work may increase the chance of recovery [Citation17,Citation24]. However, whether young adults with MH problems develop their work identity within such integrated services is not known.

The way we identify ourselves is strongly attached to work. Productive occupations constitute a constructive area for personal development and identity-shaping [Citation25,Citation26]. Identity develops from lived experience—what people do and engage in [Citation26,Citation27]. Lived experience is the basis for the feeling of who we are and what our position is in the community. A person’s occupational identity consists of the sense of who they are and wish to become. Occupational identity involves a personal sense of capacity, what is perceived as interesting and satisfying, and what is obligatory and important [Citation28]. These are principles that we rediscover in the personal recovery perspective [Citation29]. Furthermore, how others perceive and respond to us and the impact of environmental support also have the potential to advance identity development. Social interaction can be seen as the primary opportunity to get feedback on oneself and how others perceive us [Citation28,Citation30]. The social environment of professionals from MH and vocational services [Citation11], contributes with a social space [Citation15] which offers opportunities for daily social interaction to develop and change one’s identity [Citation27]. This work role identification deals with both the environment’s response to, and personal perception of, external and internal factors. When we perceive that we behave like someone with a certain role, we identify with the role and its implied status [Citation30]. Thus, the view of our own ability is related to how we perceive ourselves in a certain role. For example, our view of work ability may be related to recent work experience [Citation31]. If a disability affects the ability to participate, or external factors create circumstances that prevent participation, then identity is threatened [Citation28,Citation32]. To summarize the references above, because work may support identity development and participation in community, there is a broader meaning of work than economics and getting employed. Work is not primarily ‘having something to do’ but promotes personal recovery and helps personal exploration [Citation19]. With this background, the aim of this study was to explore the experiences of young adults with MH problems when starting to work, with a focus on the process of developing work identity. A further aim was to develop knowledge to improve the clinical reasoning among occupational therapists and professionals in MH services and vocational rehabilitation who strive to support young adults’ with MH problems in their transitions to work, and thus, everyday social and community life.

Material and methods

Design and context

The present study had a qualitative grounded theory research design [Citation33] and the material consisted of 13 in-depth interviews with young adults with MH problems. Grounded theory is an inductive research method distinct as a systematic generation of theory from data. Grounded theory analysis stay close to the empirical evidence, and is an appropriate method of studying process [Citation33]. The study was conducted in the medium-sized Swedish city of Södertälje with a population of approximately 90 000. The study was part of a larger supported employment project of Individual Enabling and Support (IES) for persons with affective disorders in the Skåne county council. The IES ethical registration number was 2011–544 [Citation34]. An additional ethics application was approved for the Södertälje context in which young adults with MH problems participated (ethical registration number 2014–277). Since the project departed from a supported employment intervention and a personal recovery perspective, the MH services and vocational rehabilitation service of the municipality were integrated into one inclusive service.

Informants

The inclusion criteria were aged 18–26 years, having a MH problem (primarily depression or bipolar disorder), and regular employment or an internship for at least three months. In Sweden, the most common age range defining young adults is 18–24 years [Citation35]. However, at the public employment service the age range is 18–25 years, with the exception of an age range of 18–29 years for persons with a disability [Citation36]. In this study we delimit at 26 years in accordance to the MH services range. ‘Working’ was defined as performing a productive job in a mainstream workplace setting that is available for any citizen. This is in contrast to working in sheltered or segregated settings set aside for persons with disabilities, such as day centers. In total, 16 persons were asked to participate; three declined and 13 entered the study. Eight informants were women and five were men, with a mean age of 21 years. Work experience ranged from three to seven months, and informants were evenly distributed within this range. Areas of work were trade and service (n = 3), operations and maintenance (n = 2), restaurant (n = 2), animal keeper (n = 2), computer/information technology (IT) (n = 2), educational work (n = 1), and transportation (n = 1). All informants had contact with MH services. Nine visited a unit for adolescents and young adults aged 16–23, while the others visited a unit for adults aged 18–65. All informants received integrated MH services and vocational support. They either had their primary contact with a supported employment specialist from the municipality who worked on the team, or with the case manager from the team.

Ethical considerations

According to the principle of autonomy [Citation37], information about voluntary participation, use of data in relation to the research aim, and the ability to withdraw from the study at any time, was given to all informants, and written informed consent was signed prior to the interviews. All data were handled confidentially. The opportunity to talk about experiences is often perceived as beneficial, but it cannot be ignored that research questions can trigger negative feelings and thoughts. Our intention was for the informants to feel that they were a resource and contributed critical knowledge to this research field.

Data collection

Theoretical sampling was applied to guide data collection. The analysis began after the first interview was done, and this governed further data collection. Informants were selected one at a time in order to discover features and dimensions connected to the research aim. This process continued until no new information emerged that added new dimensions to the analysis, and a theoretical saturation was reached [Citation38]. As part of the theoretical sampling, interviews were conducted in two rounds. The first eight interviews were performed between February and April 2015, with informants from the Södertälje branch of the IES project. A thorough analysis was then performed in 2016. In the second round, five more interviews were performed between April and July 2017. The rationale was to raise further questions on self-efficacy and to include informants having primary contact with employment specialists and case managers to address vocational needs. The responsible therapist in the MH service or the supported employment specialist first examined informant’s interest to participate, then the first author (UL) contacted them and booked an appointment. Each interview lasted approximately 60 minutes and was conducted face-to-face in a private room at the workplace or on the premises of the MH or vocational service. The first author (UL), an occupational therapist with long experience from MH and vocational rehabilitation services conducted all interviews, which were retrospective and aimed at getting the informants to tell about their experience of starting to work as openly and freely as possible. The thematic interview guide was composed by the first author and took inspiration from the IES project interview guide developed by the second author (UB) [Citation23] and the Worker Role Interview instrument [Citation39]. The guide was the basis for each interview and started with the broad, open-ended question based on the main theme of identity, participation, and work. The interview developed in a conversation and the in-depth interviewing departed in questions like: Can you describe your role at work and what it means to you? Can you tell me how you look at your work situation in relation to the Labor market? As noted above, most interview guide adjustments were made in prior to the second round of interviews with the goal of deepening the preliminary categories. To facilitate the analysis, interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim by the first author [Citation40].

Data analysis

According to grounded theory, constant comparisons characterize the entire analysis process, and proceed through the stages of open and axial coding [Citation38]. Open coding focused on dividing and joining the data into theoretical codes and common categories. Then, emerging categories were checked through axial coding where the relationships were investigated, and questions about created conditions were then posed. Literature related to the central concepts was sought in order to investigate emerging categories and hypotheses and make them empirically grounded. Notes about links and contact points between the categories were taken throughout the analysis of initial interpretations [Citation38]. At the end of this phase in analysis the emerging categories were collapsed into six main categories: ‘starting work supports identity development’, ‘work increases occupational level and structure over time’, ‘work provides opportunities to practice skills’, ‘work changes thought patterns from negative to more positive’, ‘external changes affect internal changes and vice versa’, and ‘starting work gives direction in life’. In a final analytical step, the main categories led to a hypothesis or tentative model of development of a work role. This development appeared to be a process. The analysis was conducted in ongoing consultation with the second author. A draft was reviewed in a doctoral seminar in occupational therapy and occupational science at Lund University with senior researchers in attendance.

Results

Work experiences were described as providing a development process. As illustrated in a tentative model (), the process consists of an interchange between internal and external elements that contribute to the change and development of work identity. The process of developing work identity is presented in three main headings close to the model, along with sub-categories (shown in italics).

Internal elements transform thought patterns

The informants described that by starting to work, an internal change that involved several internal elements occurred. One sub-category was an increased feeling of creating meaning in everyday life. Working contributed to a sense of meaning and was a reason for getting up in the morning. If the informants did not show up, they were missed and asked for by managers and work colleagues. One informant realized, ‘To help, to feel that you do something real that is good, that I have a role here in community, it feels good’. Another sub-category concerned the increased experience of contribution. To work meant making a difference and contribution for themselves and others. When the informants were doing something at work that others appreciated and approved of, it became a strong driving force. One informant said about the new role at work, ‘I have things that I’m good at there, for example to come up with symbols and to redraw [something]. There are several who have been satisfied with what I have done. I feel important, and I like to feel important.’ New experiences that emerged through work, together with confirmation from the external setting or environment, led to a new understanding of themselves and the surrounding world. When the informants managed challenges and their MH in relation to work, awareness of themselves increased and a new understanding resulted. They validated their own resources and difficulties.

How informants were building competence through their new experiences of a workplace context was evident. The perception of resources and skills versus difficulties directed the informants in how to match these qualities to the new working situation. This knowledge about one’s own competence proved to be fundamental for making decisions about what to do in the future, and thus for career development. Unlike previous situations when informants often avoided contact with others, work demanded and motivated them to interact and communicate with others. Social interaction was facilitated through being a working person. They perceived new social competence that affected both close and distant relations. Workplace feedback proved to be prerequisite for role building and perceived competence. One informant said, ‘At home I am very passive. At work I have drive and pay attention to everything. They say I’m smart. I correct things and make things happen. I can learn things instead of just sitting and doing nothing.’

To develop a work identity was also about being a grown-up and developing an adult role. As opposed to a previous passive existence and being strongly tied to their families, work represented an arena for self-development and building an adult identity. Work offered opportunities to relate and respond to others from the perspective of a competent adult, rather than as a child in relation to family members. At work they did things they did not think they could, which made their self-confidence grow. Work provided a conversation topic, role and status that they previously lacked in social contexts when they were unemployed and on sick-leave. One informant said, ‘When I come home, I can tell about my day. One has more to tell, a little more to be proud of.’ When the informants took responsibility at work, they might initially perceive it to be scary. However, the experience of responsibility meant a lot for their self-confidence. As a working person, they felt a greater sense of participation in their own lives and in relation to their community in general.

Another sub-category was affiliation by doing something with others in a work context. Their initial negative attitudes towards integration into the community and Labor market changed into more positive attitudes once they began work. The sense of affiliation and connectedness appeared on two different levels, partly driven by the experiences of meaning and contributing, and a desire to be a part of and contribute to community. One informant said, ‘One felt that it was worthless not to contribute anything to the community. I lived on benefits, like a real loser. Now I have something, now I can say that I do this.’ Another level of affiliation had the character of a desire to change one’s own situation, feel better, and prior to have money and rights as a community member. One young woman realized, ‘I have it so much better now that I started to work. I have my own housing like I wanted. I feel stronger and have developed myself as well.’ At both levels, the experience of a sense of affiliation gave new direction in life. They had become something and started setting goals for future career development.

In short, the internal changes that occurred gave the informants new awareness about themselves, and this contributed to new feelings and interpretations of the outside world. Earlier negative thought patterns changed into more positive ones.

External elements influence self-efficacy

External changes in parallel to the internal change became evident when the informants started to work. Everyday life changed through altered occupation, and an increase in engagement level resulted in busier days. The more informants engaged, the more their physical fatigue increased, and this in turn improved their sleep. Before beginning to work, poor sleep was a big issue, and often days and nights were inverted (i.e., they slept days and had difficulty sleeping at night). Further, the daily rhythm and structure of the days changed. Work meant that new routines were introduced and this required more thorough time management. The workplace contributed to a social context that facilitated development of regular contact and interaction with others. When the informants explored skills and performed them at work, a new arena for further practice and skill development was provided. When they practiced practical and more intellectually oriented skills in relation to colleagues, there was greater personal development, and development of new roles and work identity. External elements, together with internal elements, created new and increased self-efficacy.

Interplay forward a future perspective

In summary, starting work contributed to internal and external processes of change. New feelings, challenges, and understandings of ‘me’ and the surrounding world. These influenced how the young adults identified themselves in relation to work. The internal and external factors involved in change contributed to each other and transformed thought patterns into more positive ones, and self-efficacy in relation to work increased. Thus, earlier negative thoughts about themselves and their situation changed, and their perceptions of self-efficacy developed. This experience and reflection process became a source for identity development and finding out ‘who I am…’ The reciprocal interplay between internal and external elements contributed to a positive development process that gave a future perspective and work identity ().

Discussion

This study provides an understanding of how work identity may develop among young adults with MH problems. From of an individual perspective, developing a work identity is a mean for connectedness, participation, and a working life. Thus, development of work identity is part of the personal recovery process, and building new meaning and valued roles despite the presence of illness. These findings are in line with previous research [Citation29]. From a community perspective, shifting the practice focus from a clinical recovery perspective to a personal recovery-oriented service [Citation7–9,Citation17,Citation41] is in accordance with current Swedish national guidelines and policy [Citation42,Citation43]. Using a personal recovery-oriented service may affect the enormous long-term costs of unemployment and sick-leave benefits. Having a large number of individuals who are not in the Labor market has negative consequences for the community as well as the individuals themselves. Our results suggest that providing opportunities for development of a work identity supports personal recovery and may improve the MH and well-being of young adults.

When analyzing the data, it became evident that new thought patterns embraced the informants’ belief in their own work capacity. Therefore, we introduced the concept of self-efficacy into the analysis [Citation44]. We assumed that increased self-efficacy instilled more positive thought patterns, and vice versa, and that this may enhance the transition to work and career development. Self-efficacy is affected by how our capacity and effort unite or meet resistance in life, e.g., the response of personal performance during work [Citation26,Citation44]. Abilities need to be challenged and opportunities to practice and develop competence need to exist for the development of self-efficacy. Self-efficacy is affected by a person’s previous achievements, experiences, conviction, and dedication. The workplace functioned as an occupational arena that was both constructive and productive in its nature which impacted on self-efficacy in a realistic way [Citation44]. When young adults are unemployed and on sick leave, considerable time is spent on quiet activities. They are not provided with many opportunities for increasing self-efficacy or exploring an understanding of ‘what is fine with me’, ‘what I want to do in the future’, etc. The informants showed that increased self-efficacy had a large impact on their motivation and goal setting, life choices, and going forward in life. Having a sense of competence and efficiency, also called personal causation, are important for the volition and motivation to occupy oneself [Citation25,Citation26,Citation28]. This reasoning is consistent with a previous Swedish return-to-work study on the importance of work experience for motivation among young adults with general disabilities [Citation45]. Another study of youth development showed that there was a relationship between having little self-efficacy and being unemployed and having financial support from the parents [Citation46]. The development of work identity provided an opportunity for liberation, developing an adult identity, and transition to adulthood. The new understanding of themselves and the surrounding world, as well as changes in activities enhanced their adult perspective and supported future work aspirations. Further, work identity is linked to strengthened identity as a whole [Citation47]. In summary, it is important that young adults have opportunities to develop their work identities and self-efficacy.

We anticipated that supporting work identity might be an essential part of the personal recovery process for individuals that includes future career development. Central elements inherent in the personal recovery process were rediscovered. As reflected in our results, such elements could be described as having own achievements, assessing situations in an independent way, developing identity, hoping and having optimism for the future, and being involved in a social process among others [Citation17,Citation29]. For the informants, starting to work counteracted the sense of being marginalized. We assume that early efforts towards work can prevent long-term exclusion and provide the opportunity to live a meaningful life. Involuntary unemployment is an aspect of occupational deprivation, and implies that all people do not have the same opportunities for community participation.It becomes an occupational loss with negative effects on physical and MH [Citation15]. Today, return-to-work interventions may be viewed as having a clinical recovery perspective on mental health. This entails a focus on the mental disorder and symptoms, and work ability assessment in relation to the functional limitations, and skills training in prevocational settings [Citation48]. This situation adversely affects opportunities of young adults with MH problems to reach work since vocational support connected to a mainstream workplace is seldom provided. Efforts to improve this situation are a prioritized area in Sweden [Citation16]. International policies signal that treatment and rehabilitation should not focus on clinical recovery. Instead a person-centred practice which pay attention to the individual’s personal resources and efforts in living a meaningful life is emphasized [Citation49,Citation50]. Sweden’s health authorities recommend that vocational rehabilitation integrated with MH service is one of the highest priority psychosocial interventions for people with severe MH problems [Citation42]. This is an important area for development, and it is a challenge to foster person-centred interventions that begin with individuals’ needs and resources in relation to their starting to work. Increased awareness among professionals of the potential of developing a work identity during the transition to work is important for changing current attitudes towards a personal recovery perspective and succeeding in integration of MH and vocational services. Consequently, simultaneous determination of work, occupational, environmental, and clinical factors, and providing guidance on how to support young adults’ status and changes toward working lives [Citation51,Citation52], offering real workplace support instead of prevocational rehabilitation in sheltered settings, and collaboration with employers is critical [Citation11]. MH services ought to integrate recommended evidence-based practices like supported employment [Citation53], and supported education for young adults who want to study [Citation54].

Applications for occupational therapy

We believe that the integrated approach of vocational rehabilitation and MH services [Citation17,Citation20,Citation21,Citation24] can be applicable in occupational therapy practice when moving towards a more personal recovery-oriented service [Citation17–19]. The model reflected in the results may support the occupational therapist in his or her clinical reasoning when supporting young adults in their development of a work identity as a mean to social and community life [Citation55]. In such a person-centred practice, it is essential to attend young adults’ resources, needs and preferences when selecting interventions, not solely following standard practice [Citation17,Citation29]. Of course, such conclusions and efforts towards recovery are already ongoing within the occupational therapy practice, as reviewed by Gibson and colleagues [Citation18].

Methodological considerations

With regard to inclusion criteria, informants shared overwhelmingly positive experiences of starting to work. They had taken part in individual support to reach, gain, and maintain work. This positive outcome may have been affected through the person-centred support. While it is possible that we failed to include persons from different contexts, in the second round of the grounded theory analysis we included informants who had not received focused support from employment specialists. Instead, they received general team support and vocational services and they did not differ with regard to how they discussed their work experiences. Credibility is about truth and believability of the data [Citation56]. The interviewer’s (UL) preconceptions provide a good starting point for qualitative research since the interviewer is very experienced in working with the target group. The second author’s (UB) experience in occupational therapy practice, research, and MH services research contributed to the interpretations. The pre-understanding contributed to and was a part of the discovery of the tentative theory in form of experiences, perspectives, and interaction with the study structure [Citation38,Citation56]. The dependability of the results is strengthened by the use of a study protocol, the description of study design and procedures, and the tentative model of the development of the work identity. We conclude that it is possible for another researcher to understand the process and procedures used in this study.

Implications for future research

A parallel personal recovery process takes place and is reflected in a change of occupational patterns and increased quality of life. A quantitative and longitudinal perspective should be applied to investigate whether such research could give a more comprehensive picture of the importance of supporting the transition to work in relation to health during the initial phase of identity building in young adults. Previous research showed that supported employment increased occupational engagement and life satisfaction for persons with MH problems over time [Citation20,Citation34]. Investigating whether young adults with MH problems experience similar changes with supported employment would be helpful.

Conclusions

Our study provides information that was not previously considered. Theories on work identity development have mainly considered the situation of adults who are already in the Labor market. Perhaps our results are not transferable to other groups, other diagnoses or ages, but we assume that the process of developing work identity supports the transition to adulthood and a career development for young adults with mental health problems. These findings support that development of work identity can be anticipated to be a part of a personal recovery process for individuals. Support of young adults with mental health problems through opportunities to work is critical.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the study participants, and the Medical Faculty at Lund University, and the Coordination Association in Södertälje (SFRIS), which is part of a Swedish national organization that finances coordinated rehabilitation efforts to prevent or shorten sick leave and unemployment.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- Socialförsäkringsrapport. Sjukfrånvarons utveckling. Delrapport 1, år 2014 [Sick leave development. Progress report 1, year 2014]. Stockholm: Försäkringskassan; 2014. Swedish.

- Statens offentliga utredningar (SOU). Vad är psykiskt funktionshinder? Nationell psykiatrisamordning ger sin definition av begreppet psykiskt funktionshinder [What is mental disability? National psychiatric coordination provides their definition of the concept of mental disability]. Stockholm: SOU; 2006:5. Swedish.

- Socialstyrelsen. Psykisk ohälsa bland unga. Underlagsrapport till barn och ungas hälsa, vård och omsorg 2013 [Mental health problems among young people. Support report for children and young people's health, care and concern 2013] Stockholm: Socialstyrelsen (The Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare); 2013:5–43. Swedish.

- Bedell JR, Draving D, Parrish A. A description and comparison of experiences of people with mental disorders in supported employment and paid prevocational training. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 1998;21:279–283.

- Mc Quilken M, Zahniser JH, Novak J, et al. The work project survey: consumer perspectives on work. J Vocat Rehabil. 2003;18:59–68.

- Bejerholm U, Areberg C. Factors related to the return to work potential in persons with severe mental illness. Scand J Occup Ther. 2014;21:277–286.

- Boardman J, Grove R, Perkins R, et al. Work and employment for people with psychiatric disabilities. Br J Psychiatry. 2003;182:467–468.

- Dunn EC, Wewiorski NJ, Rogers ES. The meaning and importance of employment to people in recovery from serious mental illness: results of a qualitative study. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2008;32:59–62.

- Provencher HL, Gregg R, Mead S, et al. The role of work in the recovery of persons with psychiatric disabilities. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2002;26:132–145.

- Joyce S, Modini M, Christensen H, et al. Workplace interventions for common mental disorders: a systematic meta-review. Psychol Med. 2016;46:683–697.

- Porter S, Lexén A, Johanson S, et al. Critical factors for the return-to-work process among people with affective disorders: voices from two vocational approaches. Work. 2018;60:221–234.

- Nordström M, Skärsäter I, Björkman T, et al. The life circumstances of persons with a psychiatric disability: a survey in a region in southern Sweden. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2009;16:738–748.

- Priebe S, Matanov A, Shor R, et al. Good practice in mental health care for socially marginalised groups in Europe: a qualitative study of expert views in 14 countries. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:248.

- World Health Organization. Investing in mental health. Geneva: WHO; 2003.

- Christiansen C, Townsend EA. Introduction to occupation: the art and science of living: new multidisciplinary perspectives for understanding human occupation as a central feature of individual experience and social organization. New Jersey: Pearson Health Science; 2010.

- Statens offentliga utredningar (SOU). Ambition och ansvar. nationell strategi för utveckling av samhällets insatser till personer med psykiska sjukdomar och funktionshinder [Ambition and responsibility: national strategy for development of community interventions for people with mental illnesses and disabilities]. Stockholm: SOU; 2006:100. Swedish.

- Anthony WA. Recovery from mental illness: the guiding vision of the mental health service system in the 1990s. Psychos Rehabil J. 1993;16:11–23.

- Gibson RW, D'Amico M, Jaffe L, et al. Occupational therapy interventions for recovery in the areas of community integration and normative life roles for adults with serious mental illness: a systematic review. Am J Occup Ther. 2011;65:247–256.

- Bebout RR, Harris M. Personal myths about work and mental illness: response to Lysaker and Bell. Psychiatry. 1995;58:401–404.

- Areberg C, Bejerholm U. The effect of IPS on participants; engagement, quality of life, empowerment, and motivation: a randomized controlled trial. Scand J Occup Ther. 2013;20:420–428.

- Porter S, Bejerholm U. The effect of Individual Enabling and Support on empowerment and depression severity in persons with affective disorders: outcome of a randomized control trial. Nord J Psychiatry. 2018;72:259–267.

- Areberg C, Björkman T, Bejerholm U. Experiences of the Individual Placement and Support approach in persons with severe mental illness. Scand J Caring Sci. 2013;27:589–596.

- Johanson S, Markström U, Bejerholm U. Enabling the return-to-work process among people with affective disorders -A multiple case study. Scand J Occup Ther. 2017;27:1–14.

- Bejerholm U, Björkman T. Empowerment in supported employment research and practice: is it relevant? Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2011;57:588–595.

- Pierce DE. Occupation by design: building therapeutic power. Philadelphia: FA Davis Company; 2003.

- Christiansen CH, Bryan GT. The 1999 Eleanor Clarke Slagle Lecture. Defining lives: occupation as identity: an essay on competence, coherence, and the creation of meaning. Am J Occup Ther. 1999;53:547–558.

- Hammel WK. Self-care, productivity, and leisure, or dimensions of occupational experience? Rethinking occupational “categories”. Can J Occup Ther. 2009;76:107–114.

- Kielhofner G. A model of human occupation: theory and application. 4th ed. Baltimore (MD): Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008.

- Leamy M, Bird V, Le Boutillier C, et al. Conceptual framework for personal recovery in mental health: systematic review and narrative synthesis. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;199:445–452.

- Marwaha S, Durrani A, Singh S. Employment outcomes in people with bipolar disorder: a systematic review. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2013;128:179–193.

- Corrigan PW, Powell KJ, Rüsch N. How does stigma affect work in people with serious mental illnesses? Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2012;35:381–384.

- Laliberte-Rudman D. Linking occupation and identity: lessons learned through qualitative exploration. J Occup Sci. 2002;9:106S–111S.

- Glaser B. Basics of grounded theory analysis: emergence vs. forcing. Mill Valley (CA): Sociology Press; 1992.

- Bejerholm U, Larsson ME, Johanson S. Supported employment adapted for people with affective disorders-A randomized controlled trial. J Affect Disord. 2017;207:212–220.

- Hollertz K. The problems go ahead, the solutions consist of - organizing municipal efforts for young unemployed with support problems [dissertation]. Lund: Lund University; 2010.

- Arbetsförmedlingen. Unga med funktionsnedsättning [Young with disabilities]. Arbetsförmedlingens faktablad; 2014-10. Swedish. Available from: https://www.arbetsformedlingen.se/download/18.5b13d27d12d089d185180001381/1413804810705/vissa-unga-med-funktionsnedsattning.pdf

- Beauchamp TL, Childress JF. Principles of biomedical ethics. 7th ed. Oxford: University Press; 2013.

- Corbin J, Strauss A. Grounded theory research. Procedures, canons and evaluative criteria. Z Soziol. 1990;19:418–427.

- Fisher GS. Administration and application of the Worker Role Interview: looking beyond functional capacity. Work. 1999;12:13–24.

- Kvale S, Brinkman S. The qualitative research interview. Lund: Studentlitteratur AB; 2009.

- Topor A. Recovery from severe mental disorders. Stockholm: Natur och kultur; 2001.

- Socialstyrelsen. Nationella riktlinjer för vård och stöd vid schizofreni och schizofreniliknande tillstånd [National guidelines for care and support in schizophrenia and schizophrenia-like conditions]. Stockholm: Socialstyrelsen (The Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare); 2017. Swedish.

- Socialdepartementet. Reviderad handlingsplan för riktade insatser inom området psykisk ohälsa 2014-2016 [Revised action plan for target interventions in the field of mental health 2014-2016]. Stockholm: Regeringen; 2014.

- Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev. 1977;84:191–215.

- Andersén Å, Larsson K, Pingel R, et al. The relationship between self-efficacy and transition to work or studies in young adults with disabilities. Scand J Public Health. 2018;46:272–278.

- Mortimer JT, Kim M, Staff J, et al. Unemployment, parental help, and self-efficacy during the transition to adulthood. Work Occup. 2016;43:434–465.

- Leufstadius C, Eklund M, Erlandsson LK. Meaningfulness in work–Experiences among employed individuals with persistent mental illness. Work. 2009;34:21–32.

- Socialstyrelsen. ICF, klassifikation av funktionstillstånd, funktionshinder och hälsa [icf, classification of function states, disability and health]. Falun: Socialstyrelsen (The Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare); 2015. Swedish.

- Bellack AS, Drapalski A. Issues and developments on the consumer recovery construct. World Psychiatry. 2012;11:156–160.

- Bejerholm U, Roe D. Personal recovery within positive psychiatry. Nord J Psychiatry. 2018;72:420–430.

- Hasson H, Andersson M, Bejerholm U. Barriers in implementation of evidence-based practice: supported employment in Swedish context. J Health Org Mgt. 2011;25:332–345.

- Becker DR, Drake RE. A working life for people with severe mental illness. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2003.

- Socialstyrelsen. Individanpassat stöd till arbete enligt ips-modellen-vägledning för arbetscoacher [Individualized support for work according to the IPS mode-guidance for work coaches]. Stockholm: Socialstyrelsen (The Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare); 2012.

- Arbesman M, Logsdon DW. Occupational therapy interventions for employment and education for adults with serious mental illness; a systematic review. Am J Occup Ther. 2011;65:238–246.

- Mattingly C, Fleming MH. Clinical reasoning: forms of inquiry in a therapeutic practice. Philadelphia: F.A. Davis Company; 1994.

- Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today. 2004;24:105–112.