Abstract

Background

Interprofessional learning activities can contribute to preparing students to function in health care teams. Although the importance of communication is acknowledged, there is still a lack of understanding about how students learn to communicate interprofessionally.

Aim

To explore occupational therapist and physiotherapist students learning of skills in interprofessional communication by studying the students’ communication while working together with a virtual patient.

Material and methods

The students carried out a virtual patient encounter in pairs of two, using one computer per student, sitting side by side. The students’ actions and conversations were recorded as video films, the oral communication was transcribed and analysed using qualitative content analysis.

Results

The students created a social learning environment by posing questions, acknowledging each other and clarifying their professional perspective using familiar professional concepts. Comparing their professional views, students related their peers’ statements to their own. Departing from their own profession and using the created open environment, the students’ communication led to an interprofessional meaning-making process, with students aiming to understand each other.

Conclusions and significance

A reciprocal learning situation was created when students worked together in a virtual setting. Communicating and making shared decisions about a patient can facilitate learning how to communicate interprofessionally and improve students’ understanding of their own profession.

Introduction

Current research verifies the importance of interprofessional teamwork to delivering safe, high quality and effective health care [Citation1]. Health care has become increasingly complex through the development of expertise and technological advancements as well as the involvement of multiple professionals in patients’ care. To collaborate with other health professionals and to understand their skills and knowledge represent important competences for future health care professionals [Citation2–4]. Occupational therapists (OT) and physiotherapists (PT) often work with the same groups of patients, especially in primary health care, even though they use different means, assessments and treatments to support the patients. A reciprocal understanding of each other’s professional language, is thus crucial to providing patients with high quality care [Citation5,Citation6]. Overall, to achieve efficient interprofessional teamwork, the ability of practitioners to communicate is an important and essential factor [Citation7–9]. Communication competences, like a reciprocal understanding of professional language, constitute a foundation upon which effective collaboration between professionals can address clinical needs [Citation10,Citation11]. To perform high quality care, the professionals have to be able to communicate with each other and understand the significance of each other’s work [Citation12], and what collaboration means for the patient [Citation13].

Pedagogical research shows that it is important for OT and PT students to become aware of and to learn and to train in communication skills so as to mature in their professional identity by developing the ability to communicate with patients and professionals [Citation12,Citation14,Citation15]. Interprofessional learning (IPL) activities contribute to increased professional knowledge and skills and to improved collaboration between the professions [Citation4,Citation16,Citation17]. IPL activities are opportunities in which students have the possibility to learn from, with and about each other, while encountering patients and/or health care situations together [Citation1,Citation2,Citation4]. Social and verbal interaction is thus an important aspect of the students’ developmental process of learning [Citation18].

To make sense of new ideas and information, the students process information and knowledge by interacting with and engaging each other [Citation18]. IPL activities can facilitate OT and PT students’ interactions as they work to gain knowledge and skills that support their professional role and identity, as well as clarify similarities and differences between the two professions. IPL activities can also be a means through which the students can develop collaboration and communication skills [Citation12,Citation15,Citation17]. The students’ communication competences are strengthened if they have opportunities to engage in shared decision making [Citation13,Citation14] and are enabled to acquire knowledge, skills and attitudes that they would not have been able to acquire effectively in a non-IPL activity. IPL also increases the students’ ability to look at tasks from other professionals’ perspectives, as well as from their own [Citation19–21]. When students understand each other’s roles, and when they are able to communicate with and are aware of the knowledge that other health care professionals possesses, they can become more skilful in their own professions [Citation12,Citation22,Citation23]. Professional communication comprises a certain terminology and an understanding of how to use language for professional purposes [Citation8,Citation24]. Within the framework of occupational therapy and physiotherapy, clinical skills and communication training are primarily centred on the process, but also on situation-specific communication techniques [Citation25–28]. Communication is also progressively trained through the student’s clinical education and the students can train their communication abilities both in a specific learning situation and during routine encounters [Citation29,Citation30]. The experience of mastering professional language gives the students ability to communicate with confidence [Citation24].

Despite convincing proofs of the importance of communicative competence, there are limited studies of how students learn to communicate during interprofessional learning activities. In order to facilitate students’ communicative learning process, knowledge is needed about how students communicate with each other as a means for learning. To explore the communication between students, an interprofessional virtual patient (VP) setting for OT and PT students was organised. No previous studies that use VP to explore only the students’ communication have been found. A few studies reported the use of VP as part of an IPL activity for students from rehabilitation and medical programmes [Citation31,Citation32]. The reference material regarding communication that is pertinent to this study comes from single professions or from general theories of communication [Citation8,Citation29,Citation33–35].

The aim of this study was to explore occupational therapist and physiotherapist students learning of skills in interprofessional communication by studying the students´ communication while working together with a virtual patient.

Materials and methods

The context

The study was carried out with students from occupational therapy (OT) and physiotherapy (PT) at a medical university, Karolinska Institutet, Sweden. Parts of PT and OT students’ clinical education are performed in primary health care where the students train and develop professional and interprofessional knowledge and skills. The students carry out their clinical education in primary health care for different durations and periods and during various stages of their education; thus, the students have few opportunities to meet students from other professions with whom to carry out IPL activities. To create opportunities for students to study together, a VP has been developed, enabling students to meet and learn together in a safe environment [Citation36–38].

The setting

The virtual patient encounter

In this study a virtual patient encounter was designed and created by one of the authors (KB). It was especially adapted for OT and PT students to stimulate interprofessional learning in primary health care. Two occupational therapists and one physiotherapist from primary rehabilitations centres secured the professional content and a physician verified the medical facts. A video film of an indoor environment was produced, and the environment was chosen to illustrate areas that could be problematic for a patient after a hip fracture. The virtual patient encounter follows the first part of a home visit that a home rehabilitation team may perform in primary health care. The structure of the virtual patient encounter follows a virtual patient model and is divided into four parts: concrete experience, reflective observation, abstract conceptualisation and active experimentation with embedded reflective learning processes [Citation39]. Each part of the virtual patient encounter addresses both OTs and PTs. The information and content that are presented are based on areas that are important for the patient’s rehabilitation and on the clinical reasoning of both professions.

The students’ task with the VP is twofold: (1) to reason if and how the indoor environment can pose a possibility or an obstacle to patient’s rehabilitation after a hip fracture and (2) to suggest different interventions relevant to the patient’s care. The virtual patient encounter has been previously evaluated by students. They believed that the patient encounter facilitates dialogue and communication between the students [Citation40]. In , the main parts of the patient encounter, including the flow of information and tasks related to the virtual patient encounter, are illustrated.

Figure 1. Flow-chart of students’ activities that were performed with the virtual patient, with the teacher’s instructions in italics, (modification of the VP model in Leanderson et al. E-poster: AMEE, Milano, 2014 [Citation41]).

![Figure 1. Flow-chart of students’ activities that were performed with the virtual patient, with the teacher’s instructions in italics, (modification of the VP model in Leanderson et al. E-poster: AMEE, Milano, 2014 [Citation41]).](/cms/asset/abd11f21-3e29-4571-8471-a0c5495c8291/iocc_a_1761448_f0001_b.jpg)

Participants

The students were recruited through advertisement at the local educational premises of Karolinska Institutet:

Facebook pages for each educational programme for students in semesters three to six;

Personal emails to occupational therapist and physiotherapist students in semesters four to six; and

Direct, on-campus contact with occupational therapist students in semesters four to six.

Eight students – seven females and one male – volunteered to participate in the study. They were between 20 and 24 years old. The students were divided into four interprofessional pairs representing four PT students from semester six, three OT students from semester four and one OT student from semester three.

Data collection

To comprehensively understand the students’ communication while they worked together during a common patient encounter, the entire sessions were observed. The students carried out the virtual patient encounter in pairs of two by using one computer per student, sitting side by side. The students’ conversations and actions were recorded with video films, and the oral communications were fully transcribed. The virtual patient encounter took each pair of students 70–90 min to perform. The data includes 280–360 min of video film, which provided comprehensive data regarding the students’ communication during a planned learning activity.

Data analysis

The data analysis process was initiated as the video films were watched several times, and the students’ actions and interactions, such as body language and non-verbal communication, were noted. These notes were used as a framework and connected to the transcribed conversation during a later stage of the analysis. The students’ conversations were analysed using qualitative content analysis [Citation42].

The transcribed texts were analysed in several steps.

Initially, all the texts from the four student groups were read separately to obtain both an overview of the dialogue and the researchers’ first impressions, which were noted.

Questions were then asked to the material, regarding who talks about what and how the students were talking about (1) the patient, (2) their own professional areas, (3) the other students’ professional areas and (4) common interprofessional areas.

Meaning units were identified with the answers to those questions that were representative of the students’ communication.

The contents of the meaning units were compared and were thereafter sorted into categories.

To ensure that various types of the students’ communication were included in the analysis, different theoretical aspects – such as the social use of the language and those patterns or genres of language that shared similar structures – were taken into account [Citation43].

In the final step, the underlying meaning of the categories was interpreted revealing three themes, and the notes from the observations of the students’ behaviour were integrated.

The data was then individually analysed by both researchers during the process to ensure that different aspects of the student’s communication were included.

The researchers discussed the analysis to reach consensus and to confirm the consistency of the themes.

To define the quality of the qualitative research, trustworthiness – including credibility and dependability – was to be considered [Citation42,Citation44,Citation45]. The included students were chosen from semester three or later, based on the assumption that they would have reached the ability to reason about a patient from a professional perspective. The different steps throughout the entire research process are described clearly and may enhance dependability. A clear description of the study context [Citation46], the methodology and the findings, supported by citations, makes it possible to ascertain the transferability of the results into other contexts [Citation42,Citation44].

Ethical considerations

The study was conducted according to the WMA Declaration of Helsinki – Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects, 1964/2008. Each student received written and oral information about the study before the test session. The students were informed that they would be filmed and that only the researchers would have access to the material. To ensure the students’ anonymity, all data and transcriptions were coded. All students signed a written consent to participate and were informed that they could withdraw from the study at any time. There were no personal or professional links between the researchers and the students that could affect the students’ level of performance or the researchers’ assessment of the students’ performance or competences.

Findings

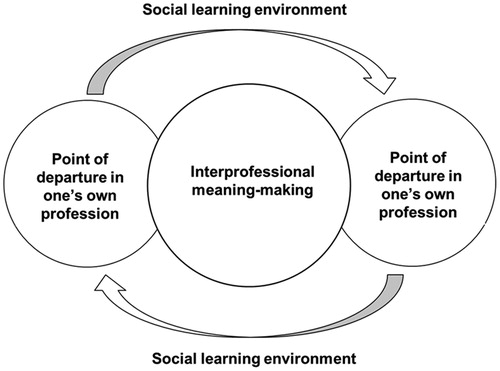

The analysis of the observations and the oral communications between the students, regarding how and what the students talked about, revealed three themes: (1) social learning environment, (2) point of departure in one’s own profession and (3) interprofessional meaning making. The three themes affected, interacted and related to each other during the whole process as the students’ performed the patient encounter. Creating an open environment became a prerequisite to enabling the students to talk about their own profession and to progressively reach interprofessional meaning making. depicts the interactive processes that occur between the themes.

Figure 2. The interactive processes between the categories regarding the students’ communication during their performance of the virtual patient.

Social learning environment

The theme social learning environment included different non-verbal and oral communication techniques that the students used throughout the entire session to create a coherent and open environment, which permitted the exchange of ideas and knowledge.

The students created an open environment, which they maintained throughout the entire process of performing the patient case, and where communication, collaboration and interaction occurred between them. To create contact and to ensure an open social learning environment, the students searched for eye contact and quickly glanced at each other. They had to turn their head towards each other so that they could look at each other, since they sat side by side. To strengthen their point of view or to clarify uncertainties, the students took breaks, turned to each other and used gestures to explain and to show what they wanted to convey.

The students asked each other questions, including whether they had perceived each other’s clinical reasoning, thoughts or suggestions correctly. They asked each other questions for clarification if there were clinical reasoning or concepts that belonged to the other profession.

Do you mean that he will have to move downstairs? (PT)

Do you also prescribe such walking aids? (OT)

The students shared their thoughts and asked each other questions about their notes. They coordinated with each other before writing their own reflections about the patient’s problems and rehabilitation, and they drew conclusions from the reflective discussions.

What should we write then? (OT)

I also write “availability”….”focus on the bathroom” on your part (directed to the OT student). (PT)

The students confirmed each other’s observations, and they gave and received feedback. They confirmed what the other student brought up regarding clinical reasoning – thoughts, suggestions or treatments – that they concluded were relevant suggestions, similarities and differences between their professional areas. They also gave confirmation concerning the patient’s problems and rehabilitation.

Absolutely, but I agree on that. I also think that it’s really important. I write technical aids and exercises. (PT)

Yes, exactly. You want the patient to be independent and to manage by himself and to follow the restrictions, but that there are different interventions on how to reach this. (OT)

The students’ conversation moved back and forth while they filled in or took over each other’s sentences and reasoning, repeated what the other student said, paused during their own thinking, and left their sentences unfinished. The students’ discourses were woven together into the same clinical reasoning.

What the patient himself wants [is] to exercise to be as independent as possible. It is also what I’m also focusing on in the everyday life. (OT)

Is it something else, then, or is it the same thing as “aims”, or what do you mean by …? (PT)

Aims, that we (the OT profession) set up aims. (OT)

… up and down these stairs all the time, and then a hip surgery. Check if he walks the stairs at all. (PT)

Yes. (OT)

Is he walking upstairs after the surgery? (PT)

Really, check at … suggest a refurnish, just until he’s well again. For a while, assist in moving the bedroom downstairs … really just to prevent the risk of falling. (OT)

Point of departure in one’s own profession

The theme point of departure in one’s own profession included different aspects of the students’ communication regarding their own profession.

The students talked about and formulated clinical reasoning, which was part of their own professional field, in relation to the patient’s problems and rehabilitation, the patient’s environment; they also discussed how to plan their treatments. The students used vocabulary and concepts that they were familiar with and confident with using during the learning activity.

It completely depends on why the patient should have a walking aid. When I was in the orthopaedic ward, some had to walk with touchdown weight bearing, and some had to do non-weight bearing, and some could bear weight until their pain limit. Then it is a little different about what applies, and then when you’re going to instruct in stair walking, and so on. (PT)

The students discussed, talked about and reflected using their own professional field and knowledge.

I only thought of that (the stairs) were narrow, but there was nothing … . I had no idea that painted stairs were slippery. (OT)

From this, to see the need for technical aid and which rehabilitation conditions he has, I still want to see. When I’m talking about rehabilitation conditions, I both want to see. Aha! But what conditions are there in the home and what conditions are there for the patient? (PT)

During the discussion and reflection, the students brought up what they believed they had mastered (or not) in their own professional area.

But I feel that in my profession, it’s not I who will try out this kind of stuff, because I feel that I have not mastered that. But walking aids, that I could do … but about this uplift of various kinds, it is not anything that we have learned so much about. It’s nothing I’m educated in. (PT)

And then, I also think much about this social activity, that it is important. I do not focus so much on this physical activity, exercise, because I feel that I really have not mastered this field, but that you have a rich social life…. (OT)

The students tested and used vocabulary and concepts that they were uncertain of. Sometimes they had difficulties with the phrasing and with how they were supposed to formulate their clinical reasoning (e.g. the similarities and differences in their suggestions for addressing the patient’s problems and rehabilitation).

So, adaption for disable … . Or, perhaps you do not say [it] like this, but “adapted seat”? Could you say [it] like that? (PT)

How can you say this? Rehabilitate, or … or do you focus on the patient’s body functions? … body functions and how to treat it. (OT)

Interprofessional meaning-making

The theme interprofessional meaning-making included different aspects of the students’ communication. This occurred when students encountered the other student’s professional area and discovered how the other student talked about his/her professional area. There emerged a process of clarification about how one’s own professional area related to and impacted the other student’s professional area, and vice versa.

The students talked about their different professional fields, including how they perceived the other professional field in relation to their own.

That I focus on maybe taking a PADL (physical activities of daily living). You focus on examining movements and restrictions. (OT)

Yes, somewhat more focused on this with exercise and the body’s function, and you may be wise about how you could carry out your activities. (PT)

The students talked about how different ways of working, including how to solve rehabilitation and environmental problems, affected each other’s work. The students described that they had to consider how they may have had to adjust their own plans or solutions in relation to the other professional’s work.

If I say, like, “Yes, we have decided [that the patient needs] a technical aid,” but then you could come in and say, “Yes, but this exercise is actually good to do.” So, you could adjust this technical aid. (OT)

… ensure that the patient gets the best possible. To find this balance, we talked about… the need for technical aids and exercises, for example. (PT)

The students expressed that they had a rather similar perspective regarding the patient’s problems and their goals for the treatment plan, but they had different purposes for focussing on a certain problem or an environmental area. They discussed how their suggestions, solutions, treatments and interventions differed and how these aspects complemented each other’s plan for the patient’s rehabilitation or environmental adaptations. They concluded that their clinical reasoning had been woven together.

I wrote “the same aim regarding the patient, for instance, independence, follow restrictions, but the OT and PT have different solutions for reaching them”. (OT)

… just as we wrote before, that [we], on the whole, looked at the same things, but that we have different purposes with the int… that is, we have the same aim, maybe, but different interventions. (PT)

The students explained that they exchanged knowledge and experience to achieve a breadth of perspectives, which would help them to avoid missing important areas. Next time, they would be able to solve the patient’s problems from different perspectives, which would enable them to offer the patients the best care.

… just that it is a good foundation to be standing on. That you look at the same things, and it contributes to that, you can exchange knowledge with each other. Because, if you should look at completely different things, it would not yield … . then, it should be two (perspectives) anyway … . how are we going to express what we mean? (OT)

… as we wrote earlier, that you exchange your own approaches and that you later maybe look at it (the patient encounter) differently the next time. That you have a broader view of the problem. (PT)

During their reflections, the students described the patient’s problems, including different interventions and adaptations in the patient’s environment, according to the similarities and differences between the two professional fields. Below a physiotherapist student compare the OT and the PT professional focus.

Physiotherapist rehabilitation – exercise … and then trying out … walking aids. Occupational therapist – you carry out an ADL (activities of daily living) assessment together, and out of this, see both what need for technical aids there is and what conditions for rehabilitation there is; … . set up the actual aims and set up a rehabilitation plan together with the patient; … I focus more on the exercise and you on the technical aids or adaptation of the home. (PT)

Discussion

The observations of occupational- and physiotherapist students working together in a virtual patient setting revealed interesting communication patterns about ongoing professional and interprofessional learning processes. The students’ clarified their actions and reasoning from the perspective of their own profession, both for themselves and for the other student, by using professional concepts and knowledge. By discussing and considering their individual professional areas, an interprofessional meaning-making process emerged. The communication was characterised by the will to understand each other’s perspectives and to express one’s own professional knowledge. A point of departure was the students’ act of continuously returning to their own profession, which was foundation to the students’ communication and interactions with each other.

The OT and PT students’ efforts to create a situation of trust and respect for each other appear to be crucial for the interprofessional meaning-making process. A meaningful and open learning environment was created with different communication techniques, like posing questions and acknowledging each other [Citation47,Citation48]. The students also used various forms of non-verbal communication and body language to underline their will to listen to each other, as well as to explain and make sure that they could understand each other [Citation49]. The open environment created by the students appeared to make them confident about expressing and testing areas of professional knowledge and vocabulary, even if they were not sure if their reasoning were correct or not [Citation47].

The OT and PT student’s asked each other clarification questions and questions that enabled them to adjust their language and actions [Citation20], which gave the students opportunities to process information and the experience to develop professional competence [Citation50]. During the interaction between the students, there was a continuing process of making judgements that was associated with the process of listening, during which the students had to understand when to interrupt or to remain patient [Citation33]. As displayed in several ways in the theme social learning environment, the OT and PT students used different means of communication to respond to each other’s clinical reasoning: encouraging, supporting, giving feedback and confirming. At the same time, the students continuously interrupted and continued each other’s clinical reasoning. The students alternated between interactions by interrupting and responding to each other to create communication between each other [Citation29,Citation51], which facilitated their learning.

To develop a professional communication identity and competence [Citation8,Citation34], the OT and PT students have to develop their own repertoire of communication skills, since professional language comprises a certain terminology [Citation8,Citation35]. The students can learn professional language not only ‘from talk’ but also ‘to talk’; the latter is a process in which the students, through talking with others, can learn their professional language [Citation18]. The OT and PT students used vocabulary and concepts from their own profession that they knew how to use with certainty. They also struggled with their vocabulary, including how to formulate and express concepts that they were uncertain of. Through listening to the other students’ talk and to talk by themselves, the students crafted opportunities to clarify, to train, to develop their own professional language [Citation18,Citation52,Citation53] and to explore the other student’s professional language and field [Citation54]. The OT and PT students also discussed how they interacted and affected each other’s work, including how they may have to adjust their own plans or solutions in relation to the other professional’s work. When the students understand the other professional’s priorities and professional field, the students can both alter the way they view a situation [Citation55] and prepare to become more skilful in their own field [Citation30,Citation35], and at interprofessional teamwork [Citation9,Citation35].

Few studies describe how student’s communicative practices during interprofessional learning activities may support their understanding about other professions and thus significantly impact their interprofessional teamwork [Citation56,Citation57]. The OT and PT students in this study, when working together with a virtual patient encounter, showed communication patterns that led to an interprofessional meaning-making process, which might could be transferred to students from other professions.

There are pros and cons when constructing a fictitious learning environment. On one hand, it is not authentic, and the same communication pattern may not occur if the students meet in a clinical setting. On the other hand, this learning environment might be beneficial for the students as they can train and practice their communication skills, which allows students from different professions to learn and practice in a familiar, safe and calm environment. During the learning activity, the students can pause to listen to each other, to discuss and to ask questions, as well as to move back and forth through the material for clarifying, and thus enhancing, understanding. One limitation, though, is that the students do not interact with an ordinary patient in a primary health care with whom they can communicate as part of their training and learning. However, students may benefit from focussing only on competences related to communication. Eventually they can transfer their experiences of communicating with each other in future learning activities and professional work.

Methodological considerations and limitation

The data is limited concerning the number of groups of students. However, focussing in depth on students’ performance provided a comprehensive picture of the communication taking place during learning environments. In this study, the students’ oral communication was transcribed, and the transcribed text was analysed. A limitation could be that certain aspects, such as body language, eye contact and tone of voice [Citation49], were only used as a framework to explore the students’ communication. Since those aspects are important, because power relations occur between the students [Citation43], some perspectives into their communication may be missing. To explore and to understand the students’ communication pattern, working from the language only, the students’ oral communication was analysed in depth.

Implications and further research

The advantages of a safe and calm learning environment, provided by using a virtual patient setting in interprofessional learning, should be considered. Virtual patient encounters could also be used in further research that aims to reach a deeper understanding of professional and interprofessional communication.

Conclusions

The communication between health professions students in a virtual setting, in this case OT and PT students, was characterised by a reciprocal learning situation with two dimensions – one cognitive and one social – that merged during the session. Students’ communication pattern reveals that they become aware of the specific concepts and language belonging to their own profession as well as the similarities and differences of the other students’ profession. Communicating and making shared decisions about a common patient in a safe learning environment can lead to interprofessional meaning making and facilitate understanding of students’ own profession.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Reeves S, Fletcher S, Barr H, et al. A BEME systematic review of the effects of interprofessional education: BEME Guide No. 39. Med Teach. 2016;38:656–668.

- CAIPE. Centre for the advancement of interprfessional education. 2002. Available from: http://caipe.org.uk/about-us/defining-ipe/.

- Ponzer S, Faresjo T, Mogensen E. [Future care requires interprofessional cooperation]. Lakartidningen. 2009;106:929–931.

- Barr H, Ford F, Gray R, et al. Interprofessional education guidelines. London: Centre for the Advancement of Interprofessional Education (CAIPE); 2017.

- Liaw SY, Zhou WT, Lau TC, et al. An interprofessional communication training using simulation to enhance safe care for a deteriorating patient. Nurse Educ Today. 2014;34:259–264.

- Solomon P, Salfi J. Evaluation of an interprofessional education communication skills initiative. Educ Health (Abingdon). 2011;24:616.

- van Rijssen H, Schellart A, Anema J, et al. A theoretical framework to describe communication processes during medical disability assessment interviews. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:375.

- Lumma-Sellenthin A. Learning professional skills and attitudes. Medical students’ attitudes towards communication skills and group learning. Linköping: Linköpings Univeristy; 2013.

- Denniston C, Molloy E, Nestel D, et al. Learning outcomes for communication skills across the health professions: a systematic literature review and qualitative synthesis. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e014570.

- Nugus P, Greenfield D, Travaglia J, et al. How and where clinicians exercise power: interprofessional relations in health care. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71:898–909.

- Schoop M. An empirical study of multidisciplinary communication in healthcare using a language-action perspective. Germany: Department of Computer Science, Informatik V – Information Systems, Aachen University of Technology; 1999. p. 59–72.

- Reeves S, Perrier L, Goldman J, et al. Interprofessional education: effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes (update). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(3):CD002213.

- Busari JO, Moll FM, Duits AJ. Understanding the impact of interprofessional collaboration on the quality of care: a case report from a small-scale resource limited health care environment. JMDH. 2017;10:227–234.

- Norgaard B, Draborg E, Vestergaard E, et al. Interprofessional clinical training improves self-efficacy of health care students. Med Teach. 2013;35:e1235–e1242.

- Steinert Y. Learning together to teach together: interprofessional education and faculty development. J Interprof Care. 2005;19:60–75.

- Aguilar A, Stupans I, Scutter S, et al. Exploring how Australian occupational therapists and physiotherapists understand each other’s professional values: implications for interprofessional education and practice. J Interprof Care. 2014;28:15–22.

- Green BN, Johnson CD. Interprofessional collaboration in research, education, and clinical practice: working together for a better future. J Chiropr Educ. 2015;29:1–10.

- Morris C, Blaney D, editors. Work-based learning. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010.

- Reeves S, Lewin S, Espin S, et al., editors. Interprofessional teamwork for health and social care. Ames (Iowa): CAIPE.Wiley-Blackwell publishing Ltd; 2010.

- Suter E, Arndt J, Arthur N, et al. Role understanding and effective communication as core competencies for collaborative practice. J Interprof Care. 2009;23:41–51.

- Chen A, Arms T, Jnes B, et al. editors. Interprofessional education in the clinical setting. New York: Springer Publishing Company; 2018.

- Barnsteiner J, Disch J, Hall L, et al. Promoting interprofessional education. Nursing Outlook. 2007;55:144–150.

- Lumague M, Morgan A, Mak D, et al. Interprofessional education: the student perspective. J Interprof Care. 2006;20:246–253.

- Silverman J, Kurtz S, Draper J. Skills for communiation with patients. Vol. 3. 3rd ed. London (UK): Radcliffe Publishing Ltd; 2013.

- Russell K, Williamson S, Hobson A. The art of clinical supervision: the traffic light system for the delegation of care. Aust J Adv Nurs. 2017;35:33–39.

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing third edition helping people change. Lettland: Guilford Press; 2012.

- Tamura-Lis W. Teach-Back for quality education and patient safety. UNJ. 2013;2013:267–271.

- Ferreira PH, Ferreira ML, Maher CG, et al. The therapeutic alliance between clinicians and patients predicts outcome in chronic low back pain. Phys Ther. 2013;93:470–478.

- Fossum B. Communication in the health services: two examples. Stockholm: Institutionen för Folkhälsovetenskap; 2003.

- Baptiste S, Solomon P, editors. Developing communication skills. 2nd ed. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer; 2010.

- Shoemaker M, Platko C, Cleghorn S, et al. Virtual patient care: an interprofessional education approach for physician assistant, physical therapy and occupational therapy students. J Interprof Care. 2014;28:365–367.

- Shoemaker M, de Voest M, Booth A, et al. A virtual patient educational activity to improve interprofessional competencies: a randomized trial. J Interprof Care. 2015;29:395–397.

- Ajjawi R, Higgs J. Core components of communication of clinical reasoning: a qualitative study with experienced Australian physiotherapists. Adv Health Sci Educ. 2012;17:107–119.

- Hiller A, Delany C, editors. Communication in physiotherapy: challenging established theoretical approaches. Oslo (Norway): Nordic Open Access Scholarly Publishing (NOASP); 2018.

- Joynes V. Defining and understanding the relationship between professional identity and interprofessional responsibility: implications for educating health and social care students. Adv in Health Sci Educ. 2018;23:133–149.

- Cook D, Triola M. Virtual patients: a critical literature review and proposed next steps. Med Educ. 2009;43:303–311.

- Walkup N, Wishner C, Gardner A, editors. Simulation in clincal education. New York: Springer Publishing Company; 2018.

- van Soeren M, Devlin-Cop S, Macmillan K, et al. Simulated interprofessional education: an analysis of teaching and learning processes. J Interprof Care. 2011;25:434–440.

- Salminen H, Zary N, Bjorklund K, et al. Virtual patients in primary care: developing a reusable model that fosters reflective practice and clinical reasoning. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16:e3.

- Björklund K. Using the virtual patient model developed at Centre for Family Medicine for creating interprofessional dialogue in learning between occupational therapy and physiotherapist students. Stockholm: Department of Learning, Information, management and Ethic (LIME), Karolinska Institutet; 2013.

- Leanderson C, Björklund K, Nabil Z. Students as producers of virtual patients: exposing the expert knowledge through a virtual patient blueprint. The Association for Medical Education in Europe. Milano: AMEE; E-poster, 9II2; 30 August–3 September, 2014.

- Graneheim U, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today. 2004;24:105–112.

- Fairclough N. Analysing discourse. In: Textual analysis for social reserach. Oxon: Psychology Press; 2003.

- Creswell W. Qualitative inquiry & reseach design: choosing among five approaches. 3rd ed. Singapore: Sage Publications Ltd.; 2013.

- Guba E, Lincoln Y. Competing paradigms in qualitative research. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage; 1994.

- Hodges B, Kuper A, Reeves S. Discourse analysis. BMJ. 2008;337:a879–a879.

- Oandasan I, Reeves S. Key elements for interprofessional education. Part 1: the learner, the educator and the learning context. J Interprof Care. 2005;19(sup1):21–38.

- Silén C, Uhlin L. Self-directed learning - a learning issue for students and faculty! Teach High Educ. 2008;13:461–475.

- Parry R, Brown K. Teaching and learning communication skills in physiotherapy. Physiotherapy. 2009;95:294–301.

- Silén C. editor. Lärande inom verksamhetsförlagd utbilidning, VFU. Lund: Studentlitteratur AB.; 2013.

- Cohn K. Developing effective communication skills. J Oncol Pract. 2007;3:314–317.

- Lingard L. The rhetorical ‘turn’ in medical education: what have we learned and where are we going? Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2007;12:121–133.

- Plack M. The development of communication skills, interpersonal skills, and a professional identity within a community of practice. J Phys Ther Educ. 2006;20:37–46.

- Jakobsen F, Hansen TB, Eika B. Knowing more about the other professions clarified my own profession. J Interprof Care. 2011;25:441–446.

- Mellor R, Cottrell N, Moran M. “Just working in a team was a great experience…” - student perspectives on the learning experiences of an interprofessional education program. J Interprof Care. 2013;27:292–297.

- Smith LM, Keiser M, Turkelson C, et al. Simulated interprofessional education discharge planning meeting to improve skills necessary for effective interprofessional practice. Prof Case Manage. 2018;23:75–83.

- Fox S. Communication and interprofessional collaborative practice: collective sensemaking work school of communication faculty of communication, art, and technology. Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of doctor of philosophy. British Columbia, Canada: School of Communication Faculty of Communication, Art, and Technology, Simon Fraser University; 2015.