Abstract

Background

Mental health problems (MHP) are a major public health challenge. Conventional healthcare has shown limitation on reducing MHP and there is a call for offering methods beyond healthcare as well as improve access to healthcare.

Aims

To explore experiences among people having MHP of (i) taking part in existential conversations in groups beyond conventional healthcare and (ii) seeking and receiving conventional healthcare.

Materials and methods

Four focus group interviews were conducted after finishing existential conversations in groups. Data was analyzed following thematic analysis.

Results

The theme Access to a community for exploration and acceptance describes communication through impressions and expressions together with others. A reflective perspective on everyday life, describes re-evaluation through reflection. Within the theme Experiences of healthcare related encounters, referring to the second aim, participants recollected feelings of disconnectedness, difficulties verbalizing MHP and dealing with rigid, standardized measures.

Conclusion

Existential conversations in group may contribute to a more reflected doing in accordance with one’s own values as well as improved mental health literacy. Design and measures within healthcare need to explicitly address MHP and consider individual’s own preferences.

Significance

This study contributes to understanding of coping with MHP in everyday life from an existential perspective.

Background

Mental health problems (MHP) are a fast-growing global concern which constitutes a major public health challenge [Citation1,Citation2] with extensive consequences for individuals and their families, personal networks, and workplaces, as well as for wider society. In 2018, one in nine persons in the EU experienced MHP [Citation1]. People with MHP have increased prevalence of poorer physical health, worser educational outcomes, greater unemployment, fewer job opportunities and decreased ability to manage everyday life. For some, these effects will be lifelong [Citation1].

MHP are usually met and treated within primary healthcare and may further on be an issue for specialized mental healthcare. Both organization of, and content in healthcare, primary as well as specialized, has been criticized for not addressing peoples’ MHP [Citation2–4]. Regarding organization, healthcare has been criticized for being fragmented and focused on reduction of diagnose specific symptoms through evidence-based guidelines with reliance on technical procedures following a rationalistic logic [Citation3–5]. This organizing principle with delineated diagnose specific guidelines, excluding patients with unclear diagnoses has raised frustration among both professionals [Citation4–6] and patients [Citation4] which may lead to underutilization of care, despite a growing need [Citation7,Citation8]. Knowledge of perceived barriers for seeking and getting help for people with MHP may inform the design of care to optimize availability and enhance appropriate help-seeking [Citation7].

Regarding content, it is stressed that MHP should not be understood only as an individual medical problem but also as an existential problem occurring in society [Citation3,Citation4]. The framing of MHP as solely a healthcare problem has limitations [Citation9]. A healthcare scope narrows both problems and, more importantly, their solutions. Efforts within healthcare improve health and reduce symptoms, thus having an impact on a functional level. However, solely medical interventions have a minor impact on activity and participation such as enhancing return to work [Citation9,Citation10]. A higher order goal for meeting MHP, going beyond symptom reduction and including social participation and existential issues is asked for [Citation3]. Interpreting MHP as a life problem, broadens the scope as well as possible solutions [Citation9]. As a result, there has been a call to expand treatments beyond conventional healthcare services [Citation2,Citation3] and promote partnership between healthcare and actors in the civil society such as values-based organizations i.e. non-profit organizations founded in a set of core values [Citation2,Citation4,Citation5].

The healthcare organization that this study concerns has the intention to improve access and participation for people with MHP and also to collaborate with organizations beyond healthcare to acknowledge existential issues as part of MHP. To make a change, knowledge on user’s own experiences of methods performed in civil society beyond conventional healthcare as well as their experiences of conventional healthcare are fundamental [Citation5,Citation11].

Existential health has shown to be a significant aspect for mental health and for strengthening resilience when encountering MHP [Citation12]. Melder [Citation12] defines existential health as a wide concept that may include both religious as well as secular world views. Melder’s research shows that many people lack an existential worldview that aids them through difficulties e.g. when encountering MHP. In the occupational science/occupational therapy (OS/OT) literature the value of an existential approach to enrich the discipline is stressed [Citation13–15]. Philosophical perspectives such as existentialism are considered essential since the profession “…operates in the often disorganized spaces of everyday life” [Citation13, p.394]. The core concepts doing, being, belonging and becoming in OS/OT theory [Citation13,Citation16] mirror an existential view on human occupation [Citation13–16] emphasizing aspects of meaningfulness. Being is mainly a personal aspect of doing and refers to who we are as well as when reflecting over doing. Being in the sense of reflecting has the potential to balance doing. The concept of becoming is linked to the idea of undergoing change in relation to doing. Belonging relates to feelings of being a part of a community, other people, a place, or a context and relates to a sense of attachment or fitting in [Citation13].

The conversations about life (CaL) course

The intervention in this study, which involves existential conversations in groups, is performed as a course that has been developed and organized within a values-based organization. The course called Conversations about Life (CaL), is not directed towards any specific mental health problem, and provides a way to handle general life problems for people in working age. The aim is to provide an opportunity for the person to stand back and reflect with the purpose of drawing up sustainable, healthy, and meaningful strategies. The CaL course has been practised for several years but has not yet been scientifically explored.

The theoretical underpinning for the CaL course emanates mainly from van Deurzen’s [Citation17] model for existential psychotherapy. This model identifies four dimensions of human existence: the physical, social, personal, and spiritual dimensions. The physical dimension is oriented towards our relationship with nature and our own body. The social dimension concerns our relationships with others, while the personal dimension concerns our relationship with ourselves. Finally, the spiritual dimension involves how we relate to the unknown, our beliefs and our convictions. These four dimensions together with the ability to work and handle everyday life, are central parts in CaL. The structure of the course is inspired by experiential learning [Citation18] which means that conversations, doings and reflections concern the individual’s personal experiences with the purpose of starting a process of change.

Individuals are referred to CaL either via healthcare or at their own initiative in collaboration with healthcare. A folder with information could be found in the waiting room or be delivered from a healthcare professional. The folder addressing people who feel a need for reflection on life and life management, also provided information on all included themes in the course together with contact information. Before decision to start all participants were invited to a study visit. Occasionally up to three study visits occurred. All participants in the CaL groups have a contact person within healthcare.

The aim of this study was twofold. The first aim was to explore participants’ experiences of taking part in existential health conversations in group and any long-term impact on everyday life. The second aim was to explore their experiences from seeking and receiving conventional healthcare for MHP.

Materials and methods

Study context

This study took place in a Southern region in Sweden and was initiated by the county council, which is responsible for healthcare, both primary and specialized, for patients with MHP. The study was undertaken in collaboration with a values-based organization providing existential dialogues in group.

The CaL course runs for ten weeks with one three-hour session per week. The leaders introduce each session and act as facilitators for the course and inform participants about shared expectations, such as mutual respect, acceptance of each other’s narratives and confidentiality. The leaders also take a participative role, discussing and sharing their personal experiences. Each session has a theme following the above-mentioned dimensions together with the ability to work and handle everyday life. A single session contains a range of activities including narratives, conversations, non-verbal interaction, self-expression exercises, creative activities and silent reflection all related to the current theme. A gratitude diary is kept during the course. The course is located outside healthcare context, in an informal environment that often has access to a garden.

Study design

This qualitative study used a focus group methodology [Citation19,Citation20], and data was analyzed following thematic analysis according to Braun and Clarke [Citation21].

Participants

Participants were recruited from four CaL courses (n = 29) provided by a values-based organization in three different cities in the south of Sweden. All participants had experience of seeking help for MHP in conventional healthcare. All 29 participants were informed about the purpose of the study both verbally and in writing.

A total of 23 participants from the four CaL courses, (aged 26–67, average age 50 years) took part in the focus groups. The duration of sick leave prior to the intervention ranged between zero and 96 months. Several participants were partly on sick leave and partly working (). Drop out was due to being busy with work or family duties (three participants), moved to another city (two participants). In one case the drop out was unknown.

Table 1. Participants’ demographics (n = 23).

Procedure and data collection

Focus groups were chosen because participants who share a common feature can express and reflect on their experiences and contribute with various reflections on a topic chosen by the researcher [Citation19]. The dynamic interaction in focus group discussions contributes to illuminate and verbalize features that are not expressed explicitly and accordingly elicit a variation of experiences as well as a more nuanced and deeper understanding of the phenomena in question. All focus groups were facilitated by the first author with open-ended semi-structured question areas and encouraging all participants to take part in the discussions and to maintaining a focus on the topics.

Four focus groups, consisting of between three and eight people, were conducted from December 2019 to January 2020 in the same settings as the CaL groups. Each focus group was held on a single occasion, four to eleven months after finishing CaL. Three of the focus groups consisted of participants from different CaL courses with the fourth focus group consisting of participants who had taken part in the same CaL course.

Three open-ended questions were presented to the participants, both in the written information and before the focus group discussions started. The three open-ended questions were not separated in the discussions but were rather intertwined and raised as the discussion naturally evolved:

What are your experiences of taking part in CaL? (First aim); How do you perceive any long-term impact from CaL on everyday life? (First aim); and What experiences do you have from seeking and receiving healthcare for MHP? (Second aim). The focus groups varied between 75-105 min in length, were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim.

Data analysis

Data was analyzed inductively following Braun and Clarke’s [Citation21] six phases: familiarization with data; generating initial codes; searching for potential themes; refinement of themes; labelling themes; and finally generating a thematic map of the data. The recordings were listened to several times and the transcribed data was read by the authors (IJ and DM) and a preliminary, individual analysis was performed by the authors (IJ and DM). The analyses and interpretations were then discussed among all authors (IJ, DM and KT) on several occasions, and tentative themes were discussed. This process was iterative with repeated reading, listening and discussion [Citation21].

Throughout the research process, validity and reliability of themes was a central focus. Validity was assured through presenting preliminary results in a meeting with representatives from participants in the CaL groups. Dependability was increased through description of the research process and confirmability was enhanced through using quotations in the results [Citation22].

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (Dnr: 2019-04076). Voluntary agreement to participate in the study was emphasized. All participants were given oral and written information about the study collectively. In some cases individual oral information was also provided. All participants were informed about the possibility to withdraw at any time without having to give an explanation. Individual informed written consent was obtained before the start of the focus groups. Confidentiality was assured in the presentation of participants’ demographics and quotations and participants were presented with fictitious names. Data were handled with confidentiality and stored without access to unauthorized persons following the principles of the declaration of Helsinki [Citation23].

Results

Three overarching themes were identified in the data analysis with ten sub-themes. The first theme Access to a community for exploration and acceptance describes the participants experiences of taking part in CaL together with other people in similar situations. In the theme A reflective perspective on everyday life, the participants describe changes they have made in their lives through participating in the CaL course. In the third theme, Experiences of healthcare related encounters, the participants recollect their experiences of seeking and receiving help for MHP ().

Table 2. Themes and sub-themes.

Access to a community for exploration and acceptance

The theme Access to a community for exploration and acceptance entails experiences of leaders as facilitators for the course, creating a permissive and safe environment which enable participants to lower their guard and begin a process of impression and expression. The experience of telling their own stories and hearing other people’s narratives helped them to become more receptive towards their own emotional state and that of other people’s.

Leaders as facilitators for a safe and inviting environment

The leaders were perceived as both facilitators and active participants in the course. In their facilitating function, the leaders were significant in terms of creating the frameworks for the physical and social environments as well as for planning the course. The leaders’ facilitating function also included creating a friendly and permissive atmosphere, with possibility to maintain one’s integrity. The structured reminder of the shared expectations and the process for each session enhanced feelings of security. A significant period of time was allocated to the sessions, so participants could feel comfortable without time pressures.

The physical environment was perceived as relaxing and restful. The homely, sometimes old-fashioned furniture was not always physically ergonomic but was ‘ergonomic for the soul.’ Anna (FG 4). Being met with lighted candles, coffee and an opportunity for small talk was appreciated, and formed a foundation for seeing each other as fellow beings. The participants expressed how they perceived the encounter within the CaL groups as welcoming, something to look forward to, and dignified.

In the active participant function, the leaders shared their own personal experiences of dilemmas that were discussed. This was perceived as enhancing a sense of being comfortable expressing one’s own experiences. In the CaL groups the participants had moved from feelings of disconnectedness towards a sense of belonging with glimpses of hope for the future. ‘…I think it would tone down much of…well…. sores in the soul that people have nowadays, they would be comforted very much if there was more of this, with competent leadership’. Sara (FG 1)

Being true to oneself and others – with integrity

All sessions began with the opportunity to express current feelings and what had happened since the last meeting in a team round. The participants expressed they felt the freedom to speak, choose what to say, or simply be quiet. There were descriptions of participants who had waited until the end of the course to express themselves in this team round. The participants felt acceptance whatever experiences and feelings they expressed. The freedom to choose when and what to share strengthened the sense of control and integrity. Some described how they needed time to feel mature before expressing their emotional state. This atmosphere helped them to lower their guard and their masks, while still feel valuable. In the conversations, they dared to be true both to themselves and to others. ‘… this thing about daring to drop your guard, yes, when you say something and I… Oh God, oh, how nice and me too and you and, well… we all have our stories, and you can sort of pick up something from everybody’. Nadja (FG 2) Thoughts and behaviours that had been comprehended as deviant appeared less strange when shared with others in an accepting atmosphere. Thus, despite having different problems, they could be inspired by others’ narratives. The participants described developing a sensitivity to both their own emotions, as well as to others’.

Communication through impression and expression

In the conversations, participants had the opportunity to listen to and be inspired by others. They reflected on their own situation in the light of other participants’ experiences and feelings. Hearing others express themselves could help them find words and ways to express themselves. By listening to others, they could identify both similarities and differences. Similarities implied that the intangible problems they lacked the words to express, could be defined and grasped. Differences allowed for a wider perspective on human circumstances.

In the CaL groups the participants gradually became more used to communicating their feelings and MHP, which for some participants was difficult and unusual. Even for those who were more experienced it was still unusual to discuss these matters among friends or even in the family.

William: – ‘It is really cool with this that we all are very different but still alike… That surprised me most of all. I know the first time when we came here, I thought, What have I embarked…And everybody is sitting and talking like that, it was so far away from what you were used to, that you sit and talk about what you think and feel, like that, and I thought, No, I will never come here again…But then the second time, so, sort of, now we are on to something.

John: – Yes

William: – And then after that, you just wanted to come every time…It is so, that is what you have been looking forward to.

Moderator: So, it was that strange the first time?

William: Yes, yes, it was like another planet.

Moderator: – Anyone more who experienced this?

Lana: –Yes, I felt also a little, I had some difficulties the first time, but then just, oh, I could never be without this.

William: – ‘No, exactly…and that we are so multifaceted may be the key’. (FG 1)

The communication with oneself was enhanced through non-verbal creative activities and reflection which could reveal intense feelings and insights within them. For example, in one session participants created a fence using wooden ice cream sticks. This fence symbolized what they wanted to keep away from and this artefact had a powerful impact on them. These fences were valued and helped remember the related feelings and thoughts.

Linda: ‘… well, the brain remembers in two ways, we made that fence… that fence…’

Nadja: I keep it in a kitchen drawer…

Emma: ‘I keep mine on the spice rack… it is a reminder’. (FG 2)

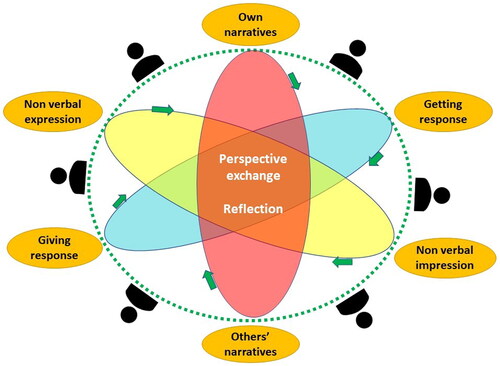

Opportunities for reflection were included in the exercises, as well as appearing in the silent listening to other participants’ stories and dialogues. Some exercises were performed in silence, and sometimes silent reflection was an exercise in itself. The participants described how they were unaccustomed to stopping and reflecting in their ordinary everyday lives. Impressions and expressions together with getting and giving response initiated a dynamic process that allowed for new perspectives, and more reflective thinking. The described dynamic process within the course can be illustrated as below ().

A reflective perspective on everyday life

This theme illuminates how the participants became more aware of their own inner values through re-evaluation, which helped them to maintain a reflected performance as well as reflected relationships. The reflective perspective had a zooming character, transcending from a close, being-in-the-moment perspective to an overarching helicopter perspective which also included other people.

Re-evaluation

For many of the participants, time for reflection, a habit incorporated from the CaL course into everyday life was experienced as enhancing performance. ‘So, you sort of put this in, a habit, to reflect more. ‘… I prioritize it more today.’ Lana (FG 1)

The awareness of their own values resulting from this reflection made it easier to prioritize. Being aware of their own values gave them the courage to resist conventionally high-valued activities with status which put pressure on them rather than contributing to feelings of meaning and satisfaction. This re-evaluation of the important things in life was expressed as emanating from reflection and contributed to a feeling of maturity.

The participants discussed how they felt more apt to accept and even encourage their own flaws, as well as noticing their own constructive characteristics. The range of being was extended to include both flaws and constructive characteristics. ‘I used to think it is not OK to show flaws…but now I have arrived in that it is OK….it is so important to show that, to set an example…because it creates an allowing environment’. John (FG 1)

Reflected performance

Changes regarding performance in everyday life were not revolutionary and were mainly related to reflected values. An increased awareness and appreciation of simple, accessible, and even repetitive everyday activities they had formerly taken for granted and hardly paid any attention to was raised. The participants related these experiences to the recurrent entries in their gratitude diaries during the CaL course. Activities they had previously performed without being mindfully present were now performed with more presence. Being present in simple activities, like going for a walk and being aware of the surroundings – whether rain or a beautiful sunrise – made the experience richer and more nuanced. The discovery of the subtle but rich content in these almost concealed activities contributed to a feeling of thankfulness and appreciation, making their everyday lives richer.

The participants felt that these simple, easily accessible activities were less valued in society. However, when performed with mental presence, these activities were experienced as valuable. These activities were often performed alone, thus allowing the participants to focus on their environment and their doings.

…go back to them like the basic needs almost and the little things in life…

it should be a perfect holiday and it should be a good car and it should be a good job…. you just have to go up, up, up, and then just… then you lose yourself like it’s not how you become happy. Paul (FG 3)

The participants expressed that they were less apt to fall into stressful patterns of performing. The reflective strategies they had achieved helped them to slow down and consider the performance of everyday activities. One result of this strategy was to not get stuck and dwell on uncomfortable events, but rather to accept them and let them pass. Their improved awareness of both their own reactions and other people’s reactions helped them to detect signs of unhealthy and stressful situations at an earlier stage in, for example work situations. The participants seemed to have obtained a sort of helicopter perspective on occupational performance and patterns, which helped them deal with stressful activities. ‘I am much more responsive to all the warning signals nowadays.’ Maria (FG 1)

Reflected relationships

In the CaL groups, the participants had experienced that lowering their guard and their masks, and showing their true feelings, was not dangerous. They had transferred this strategy to daily life and had experienced how encountering others in a less disguised manner gave them a true response in return. The lowering of their guard also gave them a feeling of relief.

The participants expressed a more thoughtful and conscious approach to their relationships which helped them to either restrict or develop them, depending on whether they were nourishing or draining, rather than just going on with them. For example, one participant had started to see her sister more often, while another participant limited contact with her brother. ‘… to examine your relationships, which you want to continue to build on and which not…which may take more energy than they give…’ Stella (FG 3)

Their relationships with themselves were also described as improved after the CaL course. The participants expressed that they could be more comfortable and enjoy being with themselves. The experience of a sense of normality and belonging from the CaL course was something the participants could maintain in their everyday lives.

Experiences of healthcare related encounters

Although focus group questions focused on experiences of seeking help from healthcare, the participants also raised healthcare related experiences with connection to their everyday life, outside healthcare. The experiences of listening, expressing, and reflecting, acquired in the CaL groups, seem to have enhanced the participants ability to collectively raise and verbalize their unspoken experiences of seeking help for MHP in a range of contexts.

In this theme the physical orientation and standardized measures within healthcare together with difficulties verbalizing experiences and feelings related to MHP were raised as thresholds for receiving care. The participants described how they could put on a protecting ‘mask’ in social encounters and feelings of disconnectedness were raised.

Rigidity and standardization

When seeking help, the circumstances in the waiting rooms at primary healthcare centres were perceived as signalling problems other than MHP. Seeing other visitors with apparent physical problems or young children playing in the waiting room could make them doubt both their experiences and also their seriousness. The participants expressed a feeling of being in the wrong place and questioning why they were sitting there, sometimes even regretting having sought help.

The encounters with healthcare professionals were characterized by rationality and time limits which the participants had difficulties responding to, due to their confused condition. There were experiences of the first encounter with the physician, who started by checking their blood pressure instead of directing the focus towards the expressed MHP.

… Then you come to the physician, what is the first thing he does? Checks my blood pressure! … My ass! But at the same time, I understand, you have to go to the healthcare centre, because you always have to… well, that depends, the first time you seek care you have to rule out that there isn’t anything physically wrong. William (FG 1)

A common experience among those who revisited healthcare was parroting – having to repeat their stories due to a change in professional contacts – which led to a lack of continuity requiring making an effort to build a new therapeutic relationship. Experiences of well-functioning communication with healthcare were also raised in the discussions. These were characterized by easily accessible support, such as direct communication with a professional via text message or phone, adapted care at varying frequencies according to current needs, and long-term contact. However, these contacts were mainly built up over the course of several years.

The imposed and rigid time limits in the sick leave process were also perceived as stressful. Sick leaves often lasted for about two or three weeks, following standardized guidelines, which meant that the participants started to reflect already after just one week whether work was possible. However, sick leave can often be prolonged after renewal of medical certificate. Much of the sick leave time was devoted to thinking about the ability to return to work, which meant that they had little time for recovery. Since it was perceived that employers and colleagues expected them to come back to work and that they could not live up to these expectations, they felt guilty about not being prepared to start working again.

When there was a week left [of the sick leave], I started to think… partly because of the employer, what will it be like, when do you come back… sort of… you have demands on you, maybe they expected I would be back… and then I feel… you start to think and consider whether I felt better… but that was a pressure I couldn’t handle. Susie (FG 4).

The therapeutic conversations within healthcare were perceived as standardized in terms of time and form. Some participants had positive experiences and found these conversations helpful. Other participants had experiences of short, condensed conversations. leading to a feeling of stress and not having finished talking. There were also perceptions of the conversations as one-way communication with the patient assumed to convey their problems to the therapist. The lack of personal responses in the therapeutic conversations could make them reluctant to talk and even feel more disconnected.

Nadja: –‘Then you just give of yourself in a way… because the therapist doesn’t sit there and say’, ‘Yes, I feel the same’.

Emma: – No.

Nadja: – And do you know, yesterday I felt really bad.

Emma: – No.

Nadja: – ‘But it is only me who… and then I finally almost feel, what the hell, am I that much of a problem?’ (FG 2)

In the focus group discussions, the rigid and standardized conversations in healthcare were contrasted to the conversations in the CaL groups which were characterized of mutual exchange among all participants, the leaders included.

Verbalizing a wordless chaos

To receive healthcare for MHP, the participants felt that they had to explain and describe their problems verbally in a sufficiently explicit manner. They described how they had initially experienced confusion when their MHP started. This was experienced as a wordless chaos.

Linda: – Because you can’t reach that feeling…I can’t reach what has created it…

Nadja: – mm

Linda: – I don’t know, it is…

Nadja: – Yes

Linda: – ‘…chaos and…then anxiety comes over me and then… I accuse myself, what’s wrong with me.’ (FG 2)

Lacking words to express oneself meant that a lot of energy was initially needed in order to manage to express problems and needs. This was perceived as having to prove their need for care. Feelings of being misunderstood when seeking initial help could affect their trust in healthcare. One example was a suggestion to try a new pillow to prevent having nightmares about past traumas. This recommendation led to mistrust and even avoidance seeking help. When the participants discussed their own inability to verbalize their MHP, they began to ponder the insufficiency of healthcare professionals to meet their inability to verbalize. However, these discussions also led to recollections of helpful strategies from healthcare. One example was a ‘crib sheet’, a list of words that the participant assessed as corresponding to feelings and experiences which helped them to make sense of and to convey their feelings.

The use of ‘masks’ when encountering others

The participants described how they often hesitated about how to appear due to the risk of stigmatizing reactions, and therefore put on a ‘mask’ both in healthcare and other encounters. This meant dressing up, putting on a smile or putting on makeup. This mask disguised and held back feelings. ‘Because most of the time you are smiling, always happy, everything is great, it’s bloody not…. You’re putting on an outward mask.’ Linda (FG 2)

The mask could protect against questions and could help to manage situations. Small talk worked with the help of the mask. On the other hand, maintaining the mask required energy. In the focus group discussions, it was obvious that the participants perceived that people in daily life responded to the mask they wore, and not to their inner state.

Experiences of not being understood, being avoided, and excluded, being diminished, or being questioned were raised in the focus group discussions. This could be experienced from healthcare professionals, other professionals as well as family members, friends, colleagues, and managers. These experiences often emanated from nonverbal expressions and subtle signs such as gazes, sighs, and tone of voice. ‘You feel sort of awkward, when you are not…you are not well, and people notice that quite quickly, so you get those gazes.’ Nadja (FG2)

The participants also discussed how they were almost astonished to meet ordinary people with ordinary jobs when they came to the CaL groups. This reaction may reveal their own prejudices of MHP.

Feelings of disconnectedness

Participants who were on sick leave described how connections with former workmates gradually disappeared. Eventually, they felt like they belonged to another group; a stigmatized and disconnected group emanating from how society labelled them: people with mental health problems on long-term sick leave. However, there were also experiences of long-term contact with the workplace and doing leisure activities together. In one case the individual had, besides MHP, visible walking aids, which workmates were anxious to take into consideration.

The participants expressed reluctance regarding meeting friends and even relatives who might ask about their health and sick leave, which restricted their connection with social networks. Public environments, such as restaurants, cafés, or pubs, were also avoided due to the risk of being confronted with questions about their mental ill health and/or sick leave. Withdrawal from other people thus restricted participation in both social and public life. The most common activities outside the home were going for a walk, going to a shopping mall, or visiting the library. ‘… it is difficult to meet others …because I know, when I have felt the worst, then I don’t want to meet anyone because it is hard…a hard meeting, as it were’. Paul (FG3)

Discussion

This study sets out to explore experiences and perceptions of existential group conversations and any long-term impact on everyday life as well as experiences of accessibility and participation when seeking and receiving support for MHP. To explore and convey the experiences, the discussion will be related to the concepts, doing, being, belonging and becoming [Citation13]. Throughout, we contrast our findings with previous research. We then propose how CaL provides a solution through provision of ‘belonging’ and offering an opportunity on reflection of ‘doing’.

Labelled belonging – feeling disconnected

The sub-theme Feelings of disconnectedness revealed that the participants saw themselves as belonging to a disconnected and stigmatized group – a group they had been assigned to through society’s labelling due to their MHP and being on sick leave. Thus, this belonging was a status that was imposed on them. Belonging is mainly defined as a positive feature emanating from individual experience of relations and connectedness [Citation13,Citation24]. The experience of belonging in this situation was rather the result of being disconnected from other belongings, such as being a person who is part of a working community. The impact of external labelling may have a greater impact on which belongings are available for a person than inner experiences of connectedness and a feeling of fitting in. The concept of belonging is a recently included concept within occupational therapy/science literature [Citation24] and is less problematized and developed. While risk factors have been associated with the concepts of doing, being and becoming, this has not – to our knowledge – been the case for the concept of belonging [Citation24,Citation25]. This finding may contribute to better understand and develop the notion of belonging.

Prior belonging – withdrawal and wearing a mask

An issue from the findings was reluctance to interact and withdrawal regarding social contexts. Withdrawal can be understood as avoiding appearing due to the risk of being questioned or stigmatized. In the discussions there were also narratives about former friends and workmates who gradually disappeared. Ponte [Citation26] describes, in her first-person account, how she feels left alone and abandoned after receiving a psychiatric diagnosis. She describes experiences of society withdrawing from her when she is confused and in need of support. The withdrawal process thus seems to act in a reciprocal manner.

The need to ‘wear a mask’, reluctance, and feelings of being in the wrong place expressed in the theme Experiences of healthcare-related encounters may be explained by the perceived risk of both stigma [Citation27] and provider stigma, that is stigmatizing attitudes from help providers [Citation28,Citation29]. Stigmatizing and pessimistic attitudes may block hope, which is an important issue for recovering from MHP [Citation26]. Studies have shown that professionals in primary healthcare feel less comfortable when dealing with patients with MHP. They also have more pessimistic expectations of the outcome of treatment [Citation27,Citation28]. A form of provider stigma may also occur in the therapeutic conversations within healthcare when the participants left meetings with feelings of being the troublesome problem [Citation26].

Being – keeping up appearances

Such stigma creates hesitation about how to present oneself, one’s being. This in turn influences both contact with professionals as well as other people. This may also explain the ‘wearing of a mask’ in everyday interactions. Disclosure of one’s ‘being’, for people with MHP is a crucial issue. Both disclosure and non-disclosure may have consequences on their life e.g. keeping a job [Citation27] which creates further hesitation about appearance and disclosure. Further, the transition from ‘mask’ to ‘disclosure’ could raise questions and confusion. Disclosure of ‘one’s being’ may initially involve highlighting the discrepancy between the mask, a vivid and healthy outlook and the reality of being on sick leave for MHP,

According to Goffman [Citation30] it is a natural phenomenon to want to present an idealized appearance. An idealized appearance gives the opportunity to strive towards something the person wants to and wishes to achieve [Citation30]. The participants in this study being on sick leave for MHP, may give a contradictory impression when presenting an idealized appearance. The use of a mask may be understood to present a wished version of oneself, revealing one’s aspiration which relates to ‘becoming’. The discrepancy in appearance – the ‘mask’ – may be understood as a presentation of the person’s aspiration and not necessarily his or her actual inner state.

Becoming – restrictive to exploratory

The participants experienced a discrepancy between conversations in healthcare and conversations in the CaL group. In healthcare, conversations were rigid in terms of time and communicational exchange. The relationship with health professionals is based on a differentiation of roles. The communication is characterized by one person presenting a problem and the other one providing a professional response. The roles and expectancies are uneven with legal differences regarding who will provide help and who will present a need for help. The formalized, structured conversations in healthcare meant some participants’ experienced feelings of stigmatization and isolation. The formalized conversations in healthcare may emanate from evidence-based standardized guidelines. van Os et al. [Citation3] are critical of standardized guidelines as these rely on group level evidence to be applied to individuals. They advocate for healthcare provision that is ‘tailored to serve the higher-order process of existential recovery and social participation’ [Citation3, p.88].

Connecting with this, a restricted ability among professionals to recognize and put words on experiences of MHP was also raised in the focus group discussions. The term ‘mental health literacy’ (MHL) was coined by Jorm [Citation31] and refers to ‘knowledge and beliefs about mental disorders which aid their recognition, management or prevention’ [Citation31, p.1166]. A key element of MHL is the ability to conceptualize an experience and recognize it as a MHP [Citation31] which enhance seeking help [Citation6]. Difficulties communicating feelings and experiences of MHP have been identified in other studies, in healthcare contexts [Citation32,Citation33], workplace contexts [Citation34,Citation35] and close social contexts [Citation36].

Limited MHL has been identified among professionals such as employers [Citation33,Citation34], rehabilitation professionals and service providers [Citation32,Citation33]. MHP have long been in the margins of healthcare which may explain the limited MHL among the latter group. Restricted MHL may have a negative impact on individuals’ becoming, for example recognizing and managing MHP. The discussions in the focus groups to include how healthcare professionals responded to their wordless chaos may indicate that the conversations in CaL had helped them to express and verbalize experiences, and to zoom out to gain a helicopter view on their perceived problems as structural problems and not only personal ones. The multiple ways of communication in the CaL groups, supported by the structure of the course, seemed to enhance the participants’ MHL. The variation of conversations and activities may have triggered a dynamic process between impression, expression, and reflection, together with giving each other response, both verbally and nonverbally. Results from other studies of methods for enhancing MHL have shown that taking time, listening in a non-judgmental manner, and communicating in a reassuring way [Citation8], using a mixture of communication media (e.g. listening, reading and creative expressions) [Citation37] and personal meetings with people with experience of MHP [Citation36] are all significant for improving MHL. All these aspects – listening in a non-judgmental manner, a mixture of ways of communication and personal meetings – are parts of the CaL groups. The participants reflections on professionals’ insufficiency to meet their limited ability to verbalize their feelings and experiences indicate that MHL limitation is a reciprocal phenomenon that may hinder becoming.

Opportunity to reflect on ‘doing’

The participants described how reflection helped them to re-evaluate in accordance with their own inner values. This reflection concerning own values seemed to strengthen their resilience towards MHP [Citation12]. Re-evaluation had an impact on both performing occupations and relationships. Both Wilcock and Hocking [Citation13] and Arendt [Citation38] raise the profound significance of reflection and consciousness for doing. Reflection raises consciousness and has the potential to consider consequences of doing and stop or change the direction of doing [Citation13,Citation38]. In the focus group discussions, it was raised how reflection was incorporated into their everyday life and helped to prioritize duties in accordance with one’s own values. This ‘reflected doing’ was also supported through the objects with symbolic messages that were created as part of the CaL sessions. They acted as souvenirs in participants’ everyday lives. These quite simple, tangible physical artefacts served as reminders for upholding constructive strategies.

In the theme A reflective perspective on everyday life, the participants described an ability to zoom in on perspectives in everyday life, from being present in the moment to getting an overview of activities in daily life. Being present in ordinary, everyday activities – as described in the focus group discussions – aligns with mindfulness. Mindful strategies have the potential to decrease stress and job burnout and increase self-compassion. Decreased stress has been shown to improve decision-making and enhance empathy [Citation39]. Mindfulness can be practised both formally and informally [Citation39, Citation40]. Formal mindfulness is practised as an occupation in itself, while informal mindfulness is incorporated into everyday activities. In the focus group discussions, the participants described these informal mindful moments in activities they previously only passed through without being mentally present, as enriching. The mindful experience not only resulted in feeling less stress but also contributed to discovering the richness in almost concealed activities. These almost concealed activities may align with the notion of hidden occupations [Citation41]. Hidden occupations may constitute a not negligible amount of time, yet they are not explicitly recognized. This may indicate that incorporating mindful strategies into everyday occupations can contribute not only to improved health but also to a richer experience of everyday life. The participants also described an enhanced ability to get an overview and reflect on their occupational patterns, thus taking a helicopter perspective. In this position, they were able to value and prioritize more in accordance with their own values. This perspective seems to align with occupational awareness [Citation39], which implies reflection on one’s own thoughts and feelings in relation to occupation.

Belonging – feeling connected

In the theme Access to a community for exploration and acceptance, the described belonging was characterized by sharing and feelings of connectedness. Similar experiences were explored with others in the CaL groups in a safe environment. The importance of this belonging, characterized by sharing, has been described as a facilitating factor for people recovering from MHP in several other studies e.g. Lund et al. 2019; Wästberg et al. 2021; Bergman et al. 2021 [Citation42–44]. Open minded conversation and reflection in an accepting and safe environment may counteract internalizing negative stereotypes connected with the labelled belonging. For people who have been labelled with a belonging they are reluctant towards, taking part in groups such as CaL in interaction with others may thus contribute to feelings of a belonging characterized by connectedness.

Limitations

One challenge when conducting focus groups is that some participants may dominate the discussions and inhibit other views. To enhance reliability, supplementary individual interviews can be recommended. However, in the focus groups where people met for the first time, it was mentioned how easily they could develop a trustful and open-minded discussion because the discussions reminded them of the CaL group format. In the focus groups – as in the CaL groups – there was a reminder that what was said should stay in the room.

The overall positive results may emanate from the recruitment process to the CaL courses. These courses are not part of ordinary healthcare but can be chosen. Most probably only those who were sincerely interested in the CaL course may have entered the course. Also, ambivalent individuals had the opportunity to do several study visits before deciding to take part which may have contributed to a homogenous group regarding experiences of CaL. Yet, individual’s preferences regarding a treatment influence both adherence and outcome and may be more important to consider than group level evidence [Citation3,Citation45].

In this study, MHP were not delineated according to diagnoses but rather as perceived mental health problems with an impact on everyday life. Thus, it was not known whether the participants had been diagnosed with common mental disorders or severe mental disorders, which may be a limitation. On the other hand, the purpose of CaL is not to treat, but rather to strengthen resilience towards MHP by addressing and enhancing existential health through the CaL course.

Conclusions

This study contributes to understanding of coping and dealing with MHP from an existential perspective. People having MHP may benefit from existential group conversations as an intervention to strengthen resilience towards MHP. Further, the findings indicate that existential conversations in group with peers may benefit MHL, enhance a zooming approach towards everyday life and relationships, through reflection, and gain a more reflected doing in accordance with one’s own values.

The participants’ experiences of both their own limited MHL and professionals’ limited MHL highlights the importance of enhancing the articulation and verbalization of MHP in consultations and wider society. Design and measures within healthcare need to explicitly address MHP. For optimizing outcome and adherence of treatment the importance of individualizing and consider individual’s own preferences regarding treatment is crucial.

Further, the study contributes with empirical understanding of the theoretical concepts of doing, being, becoming and belonging, which are common in occupational therapy and occupational science literature.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank all participants taking part in the interviews.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- OECD/European Union. Health at a glance: Europe 2020: state of health in the EU cycle. Paris: OECD Publishing; 2020.

- World Health Organisation (WHO). Civil society organizations to promote human rights in mental health and related areas: WHO Quality Rights guidance module. 2019 [cited 2023 Jun 15]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/329589

- van Os J, Guloksuz S, Vijn TW, et al. The evidence-based group-level symptom-reduction model as the organizing principle for mental health care: time for change? World Psychiatry. 2019;18(1):1–14. doi: 10.1002/wps.20609.

- Government Offices of Sweden. God och nära vård—rätt stöd till psykisk hälsa [good and close care–right support for mental health]. Vol. 2021. SOU; 2021 [cited 2022 Oct 22]. Available from: https://www.regeringen.se/rattsliga-dokument/statens-offentliga-utredningar/2021/01/sou-20216/.

- Vaeggemose U, Ankersen PV, Aagaard J, et al. Co‐production of community mental health services: organising the interplay between public services and civil society in Denmark. Health Soc Care Community. 2018;26(1):122–130. doi: 10.1111/hsc.12468.

- Rens E, Dom G, Remmen R, et al. Unmet mental health needs in the general population: perspectives of belgian health and social care professionals. Int J Equity Health. 2020;19(1):169. doi: 10.1186/s12939-020-01287-0.

- Mojtabai R, Olfson M, Sampson NA, et al. Barriers to mental health treatment: results from the national comorbidity survey replication. Psychol Med. 2011;41(8):1751–1761. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710002291.

- Svensson B, Hansson L. Effectiveness of mental health first aid training in Sweden. A randomized controlled trial with a six-month and two-year follow-up. PLOS One. 2014;9(6):e100911. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0100911.

- Damsgaard JB, Angel S. Living a meaningful life while struggling with mental health: challenging aspects regarding personal recovery encountered in the mental health system. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(5):1–10.

- Mikkelsen MB, Rosholm M. Systematic review and meta-analysis of interventions aimed at enhancing return to work for sick-listed workers with common mental disorders, stress-related disorders, somatoform disorders and personality disorders. Occup Environ Med. 2018;75(9):675–686. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2018-105073.

- Osborne SP, Radnor Z, Strokosch K. Co-Production and the Co-Creation of value in public services: a suitable case for treatment? Public Manage Rev. 2016;18(5):639–653. doi: 10.1080/14719037.2015.1111927.

- Melder C. The epidemiology of lost meaning: a study in the psychology of religion and existential public health. Scripta. 2012;24:237–258. doi: 10.30674/scripta.67417.

- Wilcock AA, Hocking C. An occupational perspective of health. 3rd ed. Thorofare, N.J.: Slack; 2015.

- Hammell KW. Dimensions of meaning in the occupations of daily life. Can J Occup Ther. 2004;71(5):296–305. doi: 10.1177/000841740407100509.

- Babulal GM, Selvaratnam A, Taff SD. Existentialism in occupational therapy: implications for practice, research, and education. Occup Ther Health Care. 2018;32(4):393–411. doi: 10.1080/07380577.2018.1523592.

- Hitch D, Pepin G. Doing, being, becoming and belonging at the heart of occupational therapy: an analysis of theoretical ways of knowing. Scand J Occup Ther. 2021;28(1):13–25. doi: 10.1080/11038128.2020.1726454.

- van Deurzen E. Existential counselling & psychotherapy in practice. London: Sage; 2012.

- Dewey J. Essays in experimental logic. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2007 [1916].

- Krueger RA. Focus groups: a practical guide for applied research. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc.; 2000.

- Freeman T. ‘Best practice’in focus group research: making sense of different views. J Adv Nurs. 2006;56(5):491–497. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.04043.x.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Nowell LS, Norris JM, White DE, et al. Thematic analysis: striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. Int J Qual Methods. 2017;16(1):160940691773384. doi: 10.1177/1609406917733847.

- World Medical Association (WMA). Declaration of Helsinki – ethical principles for medical research in-volving human subjects; 1964. Available from: https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki-ethical-principles-for-medical-research-involving-human-subjects.

- Hitch D, Pépin G, Stagnitti K. In the footsteps of wilcock, part one: the evolution of doing, being, becoming, and belonging. Occup Ther Health Care. 2014;28(3):231–246. doi: 10.3109/07380577.2014.898114.

- Hitch D, Pepin G, Stagnitti K. The pan occupational paradigm: development and key concepts. Scand J Occup Ther. 2018;25(1):27–34. doi: 10.1080/11038128.2017.1337808.

- Ponte K. Stigma, meet hope. Schizophr Bull. 2019;45(6):1163–1164. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbz011.

- Brouwers EPM. Social stigma is an underestimated contributing factor to unemployment in people with mental illness or mental health issues: position paper and future directions. BMC Psychol. 2020;8(1):36. doi: 10.1186/s40359-020-00399-0.

- Vistorte AOR, Ribeiro WS, Jaen D, et al. Stigmatizing attitudes of primary care professionals towards people with mental disorders: a systematic review. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2018;53(4):317–338. doi: 10.1177/0091217418778620.

- Charles JL. Mental health provider-based stigma: understanding the experience of clients and families. Soc Work Ment Health. 2013;11(4):360–375. doi: 10.1080/15332985.2013.775998.

- Goffman E. The presentation of self in everyday life. London: Penguin; 1990.

- Jorm AF. Why we need the concept of “mental health literacy”. Health Commun. 2015;30(12):1166–1168. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2015.1037423.

- Andersen MF, Nielsen K, Brinkmann S. How do workers with common mental disorders experience a multidisciplinary return-to-work intervention? A qualitative study. J Occup Rehabil. 2014;24(4):709–724. doi: 10.1007/s10926-014-9498-5.

- Lexén A, Emmelin M, Hansson L, et al. Changes in rehabilitation actors’ mental health literacy and support to employers: an evaluation of the SEAM intervention. Work. 2021;69(3):1053–1061. doi: 10.3233/WOR-213535.

- Jansson I, Gunnarsson AB. Employers’ views of the impact of mental health problems on the ability to work. Work. 2018;59(4):585–598. doi: 10.3233/WOR-182700.

- Thisted CN, Labriola M, Vinther Nielsen C, et al. Managing employees’ depression from the employees’, co-workers’ and employers’ perspectives. An integrative review. Disabil Rehabil. 2020;42(4):445–459. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2018.1499823.

- Stjernswärd S. Relatives and friends’ queries on a psychologists ‘question and answer’ forum online - authorship and contents. Inform Health Soc Care. 2015;40(2):154–166. doi: 10.3109/17538157.2014.907805.

- Mumbauer J, Kelchner V. Promoting mental health literacy through bibliotherapy in school-based settings. Profess School Counsel. 2018;21(1):85–94.

- Arendt H. The life of the mind: the groundbreaking investigation on how we think. New York (NY): Harvest Book; 1981 [1978].

- Goodman V, Wardrope B, Myers S, et al. Mindfulness and human occupation: a scoping review. Scand J Occup Ther. 2019;26(3):157–170. doi: 10.1080/11038128.2018.1483422.

- Elliot ML. Being mindful about mindfulness: an invitation to extend occupational engagement into the growing mindfulness discourse. J Occup Sci. 2011;18(4):366–376. doi: 10.1080/14427591.2011.610777.

- Eklund M, Erlandsson LK. Describing patterns of daily occupations-a methodological study comparing data from four different methods. Scand J Occup Ther. 2001;8(1):31–39. doi: 10.1080/11038120120035.

- Lund K, Argentzell E, Leufstadius C, et al. Joining, belonging, and re-valuing: a process of meaning-making through group participation in a mental health lifestyle intervention. Scand J Occup Ther. 2019;26(1):55–68. doi: 10.1080/11038128.2017.1409266.

- Wästberg BA, Harris U, Gunnarsson AB. Experiences of meaning in garden therapy in outpatient psychiatric care in Sweden. A narrative study. Scand J Occup Ther. 2021;28(6):415–425. doi: 10.1080/11038128.2020.1723684.

- Bergman P, Jansson I, Bülow PH. ‘No one forced anybody to do anything–and yet everybody painted’: experiences of arts on referral, a focus group study. NJACH. 2021;3(1–2):9–20. doi: 10.18261/issn.2535-7913-2021-01-02-02.

- Dorow M, Löbner M, Pabst A, et al. Preferences for depression treatment including internet-based interventions: results from a large sample of primary care patients. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9:181. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00181.