ABSTRACT

This study integrates two strands of the alliance burden-sharing literature: the research exploring the impact of the patron’s ability to credibly threaten abandonment and allies’ incentives to burden shift, and the call to disaggregate defense spending when evaluating burden sharing. We contend that allies burden shift by reallocating funds away from capabilities designed to counter threats the patron is unlikely to abandon. Using a novel dataset on naval power, we examine the impact of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization’s (NATO) 2014 Wales Pledge and find a notable reduction in non-US NATO naval capabilities post-pledge. We argue that this trend reflects members’ confidence that the US is unlikely to renege on its commitment to protect vital Sea Lines of Communications (SLOCs). Since the US cannot credibly threaten to abandon its commitment to protect the alliance’s SLOCs, NATO members’ increase in overall defense spending was shifted away from investments in naval capabilities.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022 was followed by a wave of statements from the leaders of North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) member states, who pledged to rapidly increase their military spending. At the 2022 NATO Madrid Summit, members recommitted to the Defence Investment Pledge made at the 2014 Wales Summit to work towards spending at least 2% of GDP on defense and to allocate at least 20% of their defense spending to equipment modernization by 2024 (NATO, Citation2023a). However, the unequivocal statements made to boost military expenditure have far from silenced the persistent public and academic debates about burden sharing within NATO. While most allies have indeed increased defense spending since 2014, only 11 allies met the 2% guideline in 2023 (NATO, Citation2024, p. 48). Even if NATO member states progress in implementing their ambitious spending commitments—and define 2% as a floor rather than a ceiling—burden-sharing issues will likely remain a defining characteristic of the alliance and continue to be subjected to extensive scholarly attention.

This study introduces a theory that bridges two streams of literature on burden sharing in asymmetric alliances: research that advocates for a more disaggregated approach to evaluating alliance members’ commitments (Becker, Citation2019, Citation2021; Becker & Malesky, Citation2017; Cooper & Stiles, Citation2021), and research that explores how fear of abandonment affects burden sharing within an alliance (Blankenship, Citation2020, Citation2021; Blankenship & Lin-Greenberg, Citation2022; Snyder, Citation1997).

States in an asymmetric alliance must ensure that their policy makes a sufficient contribution both to the alliance, which prevents alienation of the patron and the risk of its abandonment, and to its own domestic or national interests (Gannon & Kent, Citation2021; Snyder, Citation1984). Policymakers and scholars often refer to military spending as a percentage of GDP as a key indicator of members’ contribution to the alliance (Cooper & Stiles, Citation2021, p. 1195). However, as military expenditure can be directed toward various objectives, increasing a state’s military spending is not necessarily associated with strengthening the alliance’s collective defense. By reallocating resources within their defense budgets, member states may pursue domestic economic and political gains or invest in security priorities of specific importance to them. In doing so, they may shift burdens to other alliance members (Becker, Citation2021).

An extensive literature has argued that a patron’s ability to credibly signal its intention to abandon alliance members is a critical determinant of variation in allied burden sharing (Gerzhoy, Citation2015; Pressman, Citation2008; Snyder, Citation1997). Blankenship (Citation2021), for example, demonstrated that the more concerned an ally is about a patron’s potential abandonment, the more resources it will allocate to enhancing the alliance’s collective military capability. However, the risk of abandonment is not necessarily defined in absolute terms of an all-or-nothing proposition. A patron may signal its willingness to protect allies against specific threats yet indicate its reluctance to counter others. Consequently, allies might be more likely to invest in developing capabilities to counter threats the patron can credibly signal its unwillingness to protect. Conversely, allies are less likely to invest in developing capabilities designed to face strategic goals that the patron is unlikely to abandon.

We argue that this pattern of burden shifting tends to intensify when member states are compelled to increase military spending, either in response to growing external threats or to comply with commitments made to the alliance. The imperative to allocate more resources to “guns” at the expense of “butter” heightens allies’ efforts to use their defense budgets to extract private benefits. This tendency will be reflected in a reduction in those capabilities that the patron is less likely to abandon their provision. We test this proposition by analyzing changes in NATO members’ naval power from 2009 to 2019. We contend that the Wales Pledge guidelines and the changing security environment following Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014 motivated NATO members to reduce their investment in their naval capabilities. Our analysis demonstrates a significant decline in the naval power of non-US NATO members in the post-Wales Summit period, despite some notable investments in maritime security capacity building and the European Union’s (EU) ambitious vision to become a leading “global maritime security provider” (European Union Global Strategy, Citation2016, p. 41). European NATO members’ ability to reallocate funds from the maritime domain towards other objectives primarily stems from their confidence that safeguarding Europe’s primary Sea Line of Communications (SLOCs) will remain a public good whose provision the United States cannot afford to abandon.

As we explain, focusing on the naval capabilities of NATO members in the years after the Wales Summit may be regarded as an “easy” test for our argument. The characteristics of naval power in general, and the structure of NATO’s naval forces in particular, serve as inherent incentives for burden-shifting behavior. Such a pattern of behavior was amplified following 2014 when NATO members committed to increasing their defense budgets. While our analysis focuses on the maritime domain, we maintain that our argument and empirical findings capture a broader pattern of allies’ tendency to shift defense resources away from capabilities that are more likely to be provided by the patron. Research on burden-sharing should, therefore, not only adopt a more detailed approach that explores how allies spend their defense budgets but further disaggregate the fronts and threats to which the patron is more likely to commit.

The article proceeds as follows: In the next two sections, we briefly review the literature on burden sharing, linking maritime capabilities to studies disaggregating defense budgets to analyze how allies burden shift. Next, we explain why non-US NATO members have an inherent tendency to burden shift in developing naval capabilities and why this tendency increased following the Wales Pledge. Next, we introduce our dataset, which includes a novel measure of naval power, and present the statistical results that support our hypothesis. We then explore two alternative explanations for the observed negative association between the post-Wales Pledge era and NATO naval power. First, we consider the possibility that the apparent reduction in naval power reflects individual allies’ concerns about potential land warfare, prompting them to prioritize land forces over other capabilities. Second, we examine whether the reduction in naval power might stem from a more coordinated division of labor within NATO. We conclude by discussing how our findings contribute to the existing literature.

Beyond the 2% pledge: Why disaggregating capabilities and treats matters

Since Olson and Zeckhauser (Citation1966) introduced the economic theory of alliances, military spending has been the most widely used measure of members’ contributions to their alliance's collective military capabilities. Their seminal work considers an alliance as a pure public good that produces collective defense. Similar to other public goods, the collective defense or deterrence generated by alliances is non-excludable and non-rivalrous, thereby fostering incentives to free ride. This is particularly true in asymmetric alliances, where smaller members, whose contributions are less likely to be decisive, are incentivized to avoid spending their fair share. Olson and Zeckhauser accordingly argued that national defense burdens are correlated with members’ economic size.

The economic theory of alliances has high explanatory power in analyzing the United States’ disproportionate overcontribution to NATO, which accounted for 70% of the alliance’s defense expenditure in 2022, while its economy represented only 54% of the total GDP of the alliance members (NATO, Citation2023a, p. 50). However, it is less able to explain why certain significant economies, such as post-Cold War Germany, rank among NATO members with lower military spending relative to their GDP. This theory also fails to explain why some of the smallest economies in NATO rank among the highest spenders in terms of GDP (Blankenship, Citation2021; Plümper & Neumayer, Citation2015).

One prominent set of explanations for the disparity between the predictions of the classic theory of alliances and empirical findings highlights the shortcomings of the public goods analogy. Allies’ defense spending produces different outputs that vary in their contribution to the alliance’s collective security. Therefore, most of these outputs should be viewed as private or joint products rather than public goods (Cornes & Sandler, Citation1984). When allies allocate resources to capabilities designed to serve their specific security objectives, their military spending might generate benefits that can exclude other alliance members (Kim & Sandler, Citation2020). Even when the strategic objectives of an alliance and an individual member are highly aligned, which is a rare occurrence, that member may still pursue an allocation of resources that prioritizes those “private goods” that generate domestic gains or promote its own security interests (Becker, Citation2021; Gannon & Kent, Citation2021; Sandler, Citation2015).

Both theorists and policymakers highlight that adopting a straightforward and easily observable metric, such as the total military spending of its members, enhances the visibility of each member’s contribution and, in turn, reduces free-riding (Sandler, Citation2015, p. 200). This is one of the leading rationales behind NATO’s efforts to move towards establishing the 2% guideline. Initially introduced as a non-binding target at the 2002 Summit in the Czech Republic and reaffirmed at the 2006 Summit in Latvia, the 2% guideline was further formalized at the 2014 Wales Summit, which was held several months after the Russian invasion of Crimea (Alozious, Citation2022). Referring to the “new security challenges,” the Summit was the first time that the heads of state and government explicitly pledged to move toward investing 2% of their GDP on defense by 2024 (NATO, Citation2015, p. 6).

Nonetheless, the possibility of burden shifting remains substantial even when members comply with an easily visible policy on total military spending, whether in absolute terms or as a percentage of GDP or population. For example, to comply with the alliance’s prescribed military expenditure requirement, a country without a defense industry might prefer to invest in personnel, potentially stimulating its job market or consumption, rather than expanding equipment procurement, which would not yield domestic benefits (Becker, Citation2019).

NATO members’ willingness to mitigate this type of tendency to burden shift was a key motivation behind its members’ 2014 pledge to spend 20% of their defense budgets on equipment modernization within the next decade. Nonetheless, just as countries can shift resources within defense budgets from equipment to personnel, they might also be motivated to shift resources within the budget allocated to equipment. Similar to the case of the 2% guideline case, the question of how that 20% is spent may be just as important as whether members comply with this guideline.

The decision on resource allocation within an ally’s military equipment budget is influenced not only by domestic considerations, but also by strategic factors, such as the nature of the threats it faces and its confidence in other alliance members’ ability to address those threats. Unlike a citizen who can rely on their government to provide public goods irrespective of their individual contribution, a country in the anarchic international system that does not develop its military capabilities might find itself defenseless if its allies abandon it. Therefore, an ally’s burden sharing is highly conditional on its sense of security against external threats, which in turn depends on its confidence in its fellow alliance members, most notably the patron, to meet their commitments (Blankenship, Citation2020, Citation2021; Crawford, Citation2003; Snyder, Citation1997). A credible threat by the patron to abandon the alliance might heighten such perceived uncertainty and, consequently, affect the ally’s allocations of its military budget.

Studies investigating the relationship between a patron’s ability to generate a sense of security or insecurity and encourage burden sharing consider various measures based on allies’ aggregate military expenditures as the dependent variable (Blankenship, Citation2021). The few studies that adopted a more disaggregated approach divide defense spending into four components, as frequently seen in NATO and EU publications: equipment, personnel, operations and maintenance, and research and development (Becker, Citation2019, Citation2021; Becker & Malesky, Citation2017). While data disaggregation into these four categories enables a more nuanced analysis of how countries spend on defense, further disaggregation is needed to account for cases where countries are motivated to change allocations across and within these categories.

Even when meeting specific guidelines about spending a substantial share of their defense budget on equipment modernization, such as the NATO-agreed 20% target, countries have the discretion to allocate their equipment budget to the development of different products. NATO allies have indeed made notable progress on their commitment to spend more on major new equipment, and as of 2023, 28 allies met the 20% guideline compared to only seven in 2014 (NATO, Citation2024, p. 48). However, this progress, while important, does not necessarily suggest that the decision-making process about which capabilities to develop and invest in is free from private interest considerations. Allies might be inclined to shift resources away from developing and sustaining military capabilities that offer limited domestic economic and political benefits or support strategic goals that the patron is more likely to provide.

The maritime domain and burden sharing

We argue that the abovementioned burden-shifting tendency increases when allies are forced to augment their defense spending. More specifically, we contend that the need to move forward in meeting the Wales Pledge and to address the rising threat from Russia following its annexation of Crimea led NATO members to shift resources away from their naval capabilities.

Traditional European powers’ navies had declined before 2014, partially due to a significant reduction in the capabilities of the Russian Federation Navy (Caverley & Dombrowski, Citation2020, p. 584). In the post-Cold War era, European NATO members responded to the perceived decline in the need for defensive operations by adopting a system-centric naval approach based on maintaining stability and rules-based governance at sea and shifted their naval focus to less traditional cooperative missions. These new missions, seen as more cost-effective, consequently led to a reduction in naval budgets. However, for many European countries, shrinking budgets were sufficient to repurpose their Cold War-era naval forces (Stöhs, Citation2024, p. 114).

As naval budgets were continuously scaled back, a trend exacerbated by the financial crisis, the majority of members experienced a decline in their naval capabilities. However, we identify the 2014 Wales Pledge, widely regarded as NATO’s most important post-Cold War public initiative to address burden-sharing issues, as a turning point after which shifting resources from naval development intensified. This shift cannot be attributed exclusively to changes in the naval power balance between Europe and Russia, nor is it the result of a more coordinated cooperative division of labor among NATO allies. NATO members’ motivation and strategic capacity to divert resources from the maritime domain when forced to increase overall military spending are tied to several interrelated factors.

Our theory’s core factor for explaining why NATO members could afford to redirect resources away from their naval investments is their confidence that the United States would continue to honor its long-lasting commitment to protect international maritime commerce and the freedom of navigation. Drawing parallels to the role of the Royal Navy during the Pax Britannica, the United States has long stressed its navy’s significant role in ensuring worldwide freedom of navigation (Caverley & Dombrowski, Citation2020, p. 588). This commitment reduces its ability to credibly signal an intention to abandon NATO members that face a substantial disruption to their wartime maritime trade or other major maritime-related threats.

Drawing upon the Mahanian concept of “command of the sea,” Posen (Citation2003) famously argued that the United States holds “command of the commons,” namely the ability to project power across sea, space, and air while effectively countering other nations’ attempts to challenge its dominance in these realms. While some scholars suggest that the rise of China is undermining the United States’ command of the commons, the United States continues to be the preeminent global naval force (Caverley & Dombrowski, Citation2020; Gartzke & Lindsay, Citation2020, p. 696). The “command of the commons” is a critical strategic enabler that allows other NATO members to reduce their naval power. In other words, the United States’ strong commitment to freedom of navigation and its global naval dominance are costly signals that reassure American allies of the United States’ willingness to defend their SLOCs in wartime.

This argument might be counterintuitive to conventional wisdom regarding the relationship between the mobility of a country’s forces and its ability to reassure its allies of its commitments. The ability to rapidly deploy naval assets across theaters creates uncertainty regarding the preferred locations and functions of a country’s naval forces. As a result, unlike less mobile ground forces, deploying mobile naval forces is less effective in credibly signaling a commitment to use these forces if its ally comes under attack (Gartzke & Lindsay, Citation2020, p. 606).

These inherent characteristics of land and naval forces increase the probability of burden shifting from naval assets. The crucial question in this context pertains not only to the signals conveyed by the presence of forces in the allies’ region but also to the potential outcomes when these forces are redeployed elsewhere. Redeploying ground forces stationed on allies’ territory or relocating them to other regions may trigger more significant concerns of abandonment than the redeployment of naval assets, which can more readily return to the region if needed.

This holds true particularly in the case of NATO, given the principle of collective action explicitly referring to the maritime domain, as embedded in Article 5 and defined in Article 6 of the North Atlantic Treaty. Article 6 specifies that an armed attack includes attacks on vessels of any member party within the territorial waters of a NATO member in Europe, the North Atlantic, or the Mediterranean (NATO, Citation1949).

When the focus of the patron’s grand strategy shifts from one region to another, allies in the former region may be encouraged to reallocate defense budgets to fill the void left by the patron’s ground forces (Machain & Morgan, Citation2013), but such shifts are less likely to motivate them to increase their naval power. Specifically, the shift in the United States’ strategic attention to the Asia-Pacific region and the growing naval assets redirected to this region are not necessarily perceived as a concern by US allies in other regions. Oceanic mobility enables the US Navy to rapidly redeploy its assets from the Asia-Pacific region to other regions if the United States is interested in fulfilling its alliance commitments.

Kinne and Kang (Citation2023) recently showed that the defense network centrality of one partner in a bilateral defense cooperation agreement (DCA) could enable the other partner to reduce their defense spending. According to this logic, the maritime competition between China and the United States and the new emerging alliance networks in the Asia-Pacific region, which give much focus to naval-related issues, might benefit US allies in other regions because they increase their patron’s overall naval capabilities. This dynamic has become especially pertinent for several European NATO allies, which have recently reevaluated their strategies towards China, focusing on the expected rise in rivalry and competition elements. Notably, NATO’s 2022 Strategic Concept identified China as a strategic challenge for the first time (NATO, Citation2023a).

Beyond alliance obligations, the United States also has significant economic interests in safeguarding the uninterrupted flow of maritime traffic to and from European ports, as the EU is one of the United States’ most significant trade and investment partners. Blankenship (Citation2021) argues that allies in proximity to key maritime chokepoints around US adversaries are less likely to burden share, as their strategic importance to the United States reduces their fears of abandonment. While Blankenship highlights the strategic importance of these allies’ location in limiting adversary power projection, it is also important to acknowledge the global economy’s sensitivity to disruptions in seaborne trade traversing through such chokepoints.

An ally in a strategically important maritime location may have high confidence in the United States’ commitment to provide wartime support to counter an adversary’s attempt to project power or disrupt global seaborne trade. However, it does not necessarily guarantee protection against other threats unrelated to maritime activities. Allies might worry that the United States would pursue a selective approach and hesitate to intervene on their behalf in non-maritime-related missions. Indeed, as Beckley (Citation2015) demonstrated, US interventions on behalf of its allies have often been driven more by its own interests rather than by alliance obligations. These sources of variation in the patron’s willingness and ability to ensure protection against various specific threats might explain members’ choices regarding the way they spend their military budgets.

All other factors being equal, we therefore expect alliance members that are compelled to shift defense budgets and allocate more resources to equipment modernization will likely prefer to reallocate resources away from forces that align with the patron’s strategic interests. As allies must increase “guns” at the expense of “butter” and face limited flexibility in shifting funds between equipment and personnel, they find it more attractive to generate private benefits through resource reallocation within their budgets. One way to do so is to reduce funds to platforms the patron is more likely to provide, redirecting those resources toward goals that can yield private domestic or strategic benefits. Specifically, we maintain that the United States’ leverage to persuade its allies to amplify their contribution to burden sharing in the maritime domain is somewhat constrained compared to other operational domains, where the United States can more credibly signal its possible abandonment. Therefore, when NATO members were required to boost military spending, they reduced funds allocated to the maritime domain, which consequently led to delays in commissioning new naval platforms.

Naval power’s attributes and burden shifting

Setting the issue of burden sharing aside, most countries, in general, and most NATO members in particular, prioritize developing military capabilities designed to defend against foreign armies crossing their frontiers over maritime capabilities. Continental powers are typically more concerned about the threats posed by the rise of other land-based powers. The rise of maritime powers often evokes less concern, as these typically have fewer capabilities to threaten other countries’ territorial integrity (Levy & Thompson, Citation2010).

This is not to say that nations can afford to neglect the security of their SLOCs or disregard shifts in naval power balances. Gartzke and Lindsay (Citation2020), for example, challenge the abovementioned belief about sea power’s stabilizing influence, demonstrating that maritime nations tend to engage in more conflicts. Historically, the need to protect new trade routes and expand commerce drove great powers to bolster their navies. Securing maritime trade has become especially crucial in the still-globalized era, where supply chains span multiple regions, and most global trade is conducted by sea (Caverley & Dombrowski, Citation2020; Feldman & Shipton, Citation2022). Similar to many recent official strategic documents, NATO’s 2022 Strategic Concept describes maritime security as a key to peace and prosperity and emphasizes that the maintenance of sea-based trade is one of the key goals of its maritime strategy (NATO, (Citation2022)) ).

Global powers’ commitments to the freedom of navigation and countries’ network of alliances impact their ability to safeguard their own maritime trade. Yet, this does not imply that aligning with a maritime power eliminates the need to possess naval capabilities. First, allies have an interest in signaling that they honor their commitments and typically do not engage in overt free-riding. Conspicuous evasion of contributing to collective maritime efforts and complete reliance on other allies’ capabilities may be antagonizing.

Second, alliance members face uncertainty about their allies’ commitment to protect their trade during peacetime. Not every action disrupting an ally’s maritime trade produces direct geopolitical externalities for other allies or the patron. Consequently, allies must sustain naval forces capable of safeguarding their maritime trade routes from routine disruptions, which are less likely to trigger intervention from the patron.

Third, an alliance’s commitment to safeguard its allies’ maritime trade does not necessarily imply a commitment to protect other non-trade-related maritime threats. Indeed, securing trade remains a key motivation for strengthening naval power, yet it is not the only reason countries develop naval power. The imperative to protect near-shore and offshore “blue economy” activities and to address other, less traditional threats attributed to the so-called maritime security paradigm are also crucial motivators for states to bolster their fleets (Bueger & Mallin, Citation2023).

Modern navies comprise a range of platforms, including non-traditional elements such as aircraft, shore and offshore installations, and satellites. However, traditional naval vessels such as frigates, destroyers and aircraft carriers still possess distinct capabilities that remain relatively unparalleled. These include the ability to sustain a presence in critical regions far from home over extended durations and the capability to execute combat operations at sea or on land upon political directives. Therefore, investing in naval forces can serve the alliance’s strategic objective but also generate private benefits for the allies. For example, the navies of Great Britain and France, the preeminent European naval powers, allocate substantial resources to nuclear deterrence for the alliance (Caverley & Dombrowski, Citation2020, p. 584). However, the ability of these and other navies to project power globally also allows them to pursue their specific interests, such as upholding colonial empires or asserting influence against rivals not necessarily shared with the alliance.

We are, therefore, not suggesting in any way that the US commitment to freedom of navigation obviates the need for its allies to develop naval power. Nevertheless, the US commitment is pivotal in shaping resource allocation policies, specifically when allies are compelled to reallocate resources within their defense budgets.

NATO maritime burden sharing

NATO’s primary source of coordinated maritime power that can be rapidly deployed in times of tension is its Standing Naval Forces (SNF). The SNF comprises four groups: the Standing NATO Maritime Groups (SNMG1 and SNMG2) and the Standing NATO Mine Countermeasures Groups (SNMCMG1 and SNMCMG2). A task force’s command duration is usually one year, and each group’s composition typically changes every six months (NATO, Citation2023b). In response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, NATO activated its Graduated Response Plans in February 2022, resulting in the integration of the four forces into the NATO Very High Readiness Joint Task Force (NATO, Citation2023b).

These task groups offer a relatively low-cost means of power projection, sending high-value political signals of alliance unity without the international and domestic political concerns and complications associated with deploying ground forces (Tallis, Citation2022). From the individual member’s perspective, participation in these naval forces serves as a means to signal their commitment to the alliance. However, one may question whether this can be considered a “costly signal.” While the daily operating costs of platforms engaged in NATO maritime task forces may be relatively high, each member typically deploys a limited number of platforms. Undoubtedly, the sinking of member states’ naval assets would result in significant economic costs and potential loss of life of crew members. Such a scenario is, however, unlikely, given that most current peacetime NSF missions are conducted in favorable conditions and superior warships can usually sail away from unfavorable positions.

While the marginal costs of participating in maritime task forces are relatively low in both economic and risk terms, the marginal cost of increasing the alliance’s overall capability by one unit is notably high. Shipbuilding is characterized by high initial sunk costs and high variable costs in research and development (R&D) and production. Although the maritime domain is traditionally characterized by a relatively small number of platforms, these platforms are among the most expensive and technologically complex military hardware nations have at their disposal.

Furthermore, some products in the naval sector are characterized by short production series, resulting in high unit costs. This inherent feature of naval building makes it conducive to cross-national cooperation, as collaboration can help mitigate these high costs and achieve greater cost-effectiveness. The idea of consolidating European naval firms and establishing a “Naval Airbus” has been advocated for several decades. However, domestic pressures to engage with prominent local naval firms have hindered cross-national consolidation, impeding the ability to leverage economies of scale and enhance R&D and production efficiency (Bellais, Citation2017).

Hypothesis: The negative impact of the Wales Pledge on NATO naval power

Our theoretical discussion yields the prediction that when allies are forced to adjust their defense budgets, they reduce their capabilities aimed at defending against threats that the patron is more likely to protect against. The discussion above suggests that the maritime domain, within the context of NATO in the post-Wales Summit era, may be considered an “easy” case for testing our broader theoretical argument. The unique characteristics of naval power, coupled with the structure of NATO, the economic interdependence between the United States and Europe, and the state of global maritime competition, all contribute to reducing the United States’ ability to credibly signal its intention of abandoning its commitment to intervene in case of disruptions to maritime traffic in NATO’s SLOCs. Along with these variables that speak directly to our theoretical argument, the features of the naval industry and the high unit costs of producing naval platforms increase countries’ tendency to shift defense resources away from naval assets when facing a need to increase defense budgets.

We accordingly expect that non-US NATO members’ efforts or need to move forward in meeting their declared aim of spending 2% of GDP on defense and 20% of defense budgets on equipment modernization is associated with a reduction in their naval capabilities. Studies that quantitatively explored the impact of the Wales Pledge found a positive and statistical association between a simple variable that captures NATO defense spending in the post-2014 period (Becker et al., Citation2023; Blum & Potrafke, Citation2020). The data published by NATO and the empirical results reported by Becker et al. (Citation2023) also imply that the Wales Pledge generates the desirable effect of promoting defense expenditure on new equipment. We argue that the rise in total defense and equipment spending was accompanied by a reduction in the naval capabilities of non-US NATO members.

H1: The post-Wales Summit period is associated with a reduction in the maritime capabilities of non-US NATO allies.

One could, therefore, argue that the heightened perception of possible large-scale land conflicts in Europe led allies to focus specifically on modernizing land forces and prioritizing land force development at the expense of naval and other military capabilities. In the section that addresses alternative explanations, we will explain why we believe that this is not the case. Nonetheless, even if the 2014 annexation of Crimea triggered a drastic shift in favor of land over other naval capabilities, such a change would still support our argument about the relationship between allies’ ability to burden shift and their confidence in the United States maintaining its maritime commitments. Our main interest is the relationship between alliance members’ burden-shifting choices and the alliance patron’s ability to signal its commitment to defend against specific threats and domains. We hypothesize that this relationship will become particularly strong when allies are forced to adjust their defense budgets. Thus, to explore our causal mechanism, we are not required to determine the isolated effects of the Wales Pledge and of the Russian invasion on members’ motivations to burden shift.

Research design

We test our hypothesis using a country-year dataset that covers annual naval data from 2009 to 2019. The unit of analysis is the country-year for all non-US NATO allies with coastal access. The dataset begins in the late 2000s, when efforts to formalize the 2% guidelines gained momentum. We selected 2009 as the starting point to avoid the potential influences of the 2008 financial crisis and the Russian invasion of Georgia. The dataset ends in 2019 to exclude shocks caused by the COVID-19 crisis that might impact our results.

Dependent variable

Measuring the naval power of many countries over a long period is a complex and challenging task. Recent studies that include naval power variables in statistical analyses have relied on the dataset of Crisher and Souva (Citation2014), which reports the total tonnage for each active naval platform in the fighting naval forces of 73 countries in a country-year format. However, it does not include all NATO member states and extends only up to 2011.

We, therefore, created a new dataset of NATO members’ naval power to cover the period from 2009 to 2019 based on the annual editions of Jane’s Fighting Ships, published by Janes Information Group. These publications provide data and analysis on nearly all countries’ naval and coastguard capabilities. For each country, it reports several important aspects of each vessel (the class, type, tonnage, and armament). Thus, we could simply multiply the number of ships within each class by their tonnage to obtain the total tonnage per class. To calculate Naval Power, we summed the tonnage per class of all classes in a given year.

In the Online Appendix, we provide additional information on our coding method, explain our selection criteria for vessels, and list the types of platforms included in our coding. In general terms, we account for all platforms reported by Jane’s Fighting Ships. The contemporary maritime security agenda advocated by the EU and individual countries reflects a holistic multi-issue approach (Bueger & Mallin, Citation2023). The pursuit of this agenda might influence countries’ allocations within their navies. To refer to as many platforms as possible relevant to achieving traditional and less traditional maritime objectives, our platform inclusion criteria were as inclusive as possible. Thus, Naval Power captures the total tonnage of a state’s naval fighting forces, their support vessels and the vessels of their armed coastal guard.

We acknowledge that total tonnage is not a perfect measure of a navy’s performance in naval combat and other missions, as it refers exclusively to quantity, not quality. However, tonnage is usually strongly correlated with ship capabilities and typically captures an overall assessment of the size of naval platforms (Markowitz & Fariss, Citation2018, p. 86). More importantly for our research, a consistent rise in a state’s total tonnage would generally indicate higher investment in its navy.

Notably, total tonnage is sensitive to cases where a country purchases a single substantial platform. For example, in 2019, Norway commissioned the 27,500-ton Maud-Class Fleet replenishment vessel, the first and only fleet replenishment vessel procured by the Norwegian Navy (Jane’s Fighting Ships, Citation2019). This vessel increased the Norwegian Navy’s total tonnage by about 40 percent. Conversely, if a substantial platform is decommissioned from a country’s navy and is not replaced by an alternative platform, total tonnage would decrease significantly. As a general trend, we expect the latter case to be more common than the former in the post-Wales Pledge period.

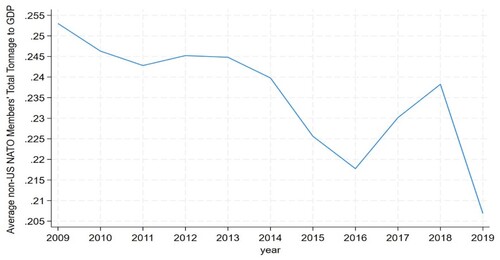

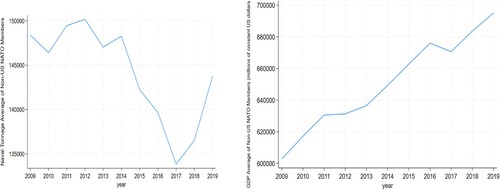

Following Markowitz and Fariss (Citation2018), we created an index that measures each state’s total tonnage relative to GDP.Footnote1 Dividing military expenditure, military unit size or equipment by GDP is also in line with academic research and NATO policy discussions on the so-called 3 Cs: Cash (defense share of GDP), Capabilities (equipment) and Contributions (operating and maintenance share). Since economic size impacts a member’s ability and motivation to maintain a large fleet, dividing total tonnage by GDP is essential.

shows the evolution of the average total tonnage to GDP index of non-US NATO members over our sample time frame. Yet, it should be noted that similar to other measures divided by total GDP, our measure might be a relatively conservative measure of a state’s investments in its navy. If a state’s total tonnage rises, but its tonnage growth rate is slower than its GDP growth rate, this measure will indicate a relative decline in naval power. further illustrates this point by showing the evolution of the index's two components—total tonnage and GDP.

We, therefore, subject our primary set model to a series of robustness tests in which the dependent variable is total tonnage and logged total tonnage. In the Appendix, we further divide total tonnage by military personnel and defense expenditure. We also replace total tonnage with the number of major naval platforms with offensive capabilities.

Independent variable

Our primary explanatory variable should capture how the Wales Pledge impacted non-US NATO members’ naval power. We achieve this by coding Wales Pledge, a dummy variable coded “1” for years after 2014 and “0” otherwise. We expect the coefficient of this variable to be negative, indicating that the post-Wales period is associated with a decline in NATO naval power.

Control variables

The models include variables commonly used in empirical research in which naval power is the dependent variable. Some of these control variables are particularly relevant for capturing the determinants of a state’s naval power, while others are relevant to naval power and overall defense spending. We also control for variables that are not typically included in studies on naval growth but are considered industry standards in empirical research on burden sharing. Recall that our expectation about trends in naval power is based on defense budget reallocation decisions. It is therefore crucial to control for factors that influence a state’s decision-making process regarding military expenditure allocation.

GDP and GDP per capita: According to the classic economic theory of alliances, countries with larger economies are expected to exhibit a reduced free-riding tendency. Therefore, we control for each state’s GDP (logged) in a given year, a key variable in the public choice literature.Footnote2 We also include the logarithm of GDP per capita to control for members’ wealth, which impacts a government’s capacity to allocate resources to defense spending in general and specifically to the acquisition of costly naval platforms.Footnote3 We obtained GDP data from UNCTADstat, produced by the UN DEAS Statistical Division (UNCATD, Citation2023).

Trade Openness: Global trade integration and the imperative to secure trade are important drivers of a country’s decision to strengthen its naval capabilities (Feldman et al., Citation2021). We therefore include the commonly used variable for a state’s economic dependence on foreign trade, operationalized as the ratio of a state’s total trade to its GDP.

Urban Population: We also include a variable that reflects the proportion of a country’s urban population, measured as a percentage of its total population. Several studies suggest that the demand for a navy that can protect the flow of trade increases as a state’s economy transitions from an agricultural to an urbanized industrial or service-based economy (Crisher, Citation2017; Feldman et al., Citation2021). Population data are taken from UNCTADstat.

Primary Energy Consumption (PEC): Markowitz et al. (Citation2019) take the logic mentioned above one step forward, demonstrating that more production-oriented economies are more likely to invest in power projection capabilities. They use a state’s domestic energy consumption as a proxy for production intensity, demonstrating a strong statistically significant association between this explanatory variable and total naval tonnage. Following this logic, we include the log-transformed primary energy consumption (PEC) measured in kilowatt-hours per person per year. These data come from Our World in Data (Ritchie et al., Citation2022).

Competition: Markowitz and Fariss (Citation2018) argue that states in more competitive geopolitical environments tend to develop power projection capabilities, allowing them to deploy forces over long distances. Using a country-year index of geopolitical competition that they developed, they demonstrated a strong association between their index and a state’s total naval tonnage. Since their data extend only to 2010, we followed their operationalization approach to calculate the geopolitical competition environment of each country in our models for the entire sample in the analysis. In general terms, the index refers to each state’s geographic position relative to every other state in the international system, the relative economic size of those other states, and the degree to which they possess inherent compatible interests.

Year in NATO: This variable is frequently used in studies on burden sharing within NATO to capture how long a country has been part of the alliance. It aims to capture the level of institutionalization among member states, assuming that new members might act differently from old members in regard to burden-sharing.

Threat and Russian Naval Power: To account for the threat posed to each NATO member by Russia, we calculated the inverse distance from each member’s capital city to Moscow, and multiplied it by the log of Russian military spending. Military spending data are taken from SIPRI (SIPRI, Citation2023), and distance data are taken from the Distance Between Capital Cities dataset. We also control for the logged total tonnage of Russia.

Alliance Naval Power: Prior studies incorporated a variable measuring the total defense expenditures of all allies, excluding Ally A, to represent the negative spillover effect of an increase in the military capabilities of all other states on the contributions of an individual Ally A (George & Sandler, Citation2018). Following this rationale, we include Alliance Naval Power, which is the total tonnage of all NATO allies minus that of Ally A (logged).

Country-fixed effects, Coastline, and Land Borders: We include country-fixed effects to control for omitted time-invariant characteristics of NATO members that might impact their tendencies to develop their naval power. While we believe this is the appropriate method for testing our hypothesis, including country-fixed effects does not allow us to specify geographic factors because they are perfectly collinear with country-fixed effects. Therefore, we start our empirical analysis with an alternative estimation that does not include country-fixed effects, which allows us to examine the impact of the geographic factors outlined in the literature. Specifically, Coastline is the log-transformed length of a state’s coastline in kilometers, based on the CIA World Factbook (CIA, Citation2023). In line with the expectations of the pioneers of modern naval strategy thinking, the coefficient of this variable is expected to be positive and significant, indicating that coastline length motivates the development of naval power. Since our causal mechanism focuses on processes that lead alliance members to shift investments away from naval power development, controlling for non-maritime-related geographic threats that impact how countries spend their defense budgets is essential. We accordingly include the logged total length of a country’s borders with all non-NATO members. In the Appendix, we include the results of robustness tests with more time-invariant factors.

Results

presents the results of our first set of models using standard panel estimation. We cluster standard errors at the country level to correct for heteroscedasticity and serial correlation. The dependent variable in Models 1 and 2 is Total Tonnage to GDP. Model 1 does not include country-fixed effects and thus enables the analysis of the impact of time-invariant factors. The dependent variable in Models 3 and 4 is Total Tonnage and Logged Total tonnage, respectively.

Table 1. Wales Pledge and Naval Power.

Overall, the results in strongly support our main argument about the Wales Pledge’s negative effect on non-US NATO members’ investments in their naval capabilities. In line with Hypothesis 1, the coefficient of Wales Pledge is negative and statistically significant in Models 1 and 2, suggesting that the post-Wales Pledge period is associated with a reduction in total tonnage to GDP. The negative and statistically significant coefficients of Wales Pledge in Models 3 and 4 indicate that, on average, the total tonnage of members in the post-Wales Pledge period was lower.

Substantively, according to Model 1, the tonnage to GDP ratio is, on average, lower by 0.04 in the post-Wales period. Model 2 indicates a more pronounced decline, with an average decrease of 0.03. To put these findings into perspective, between 2009 and 2019, the tonnage to GDP ratio averaged 0.23 with a standard deviation of 0.17, suggesting that the observed effects in both models are substantial.

As for the geographic time-invariant control, Model 1 shows that Coastline is positive and statistically significant. In line with modern naval strategies, these results suggest that NATO members with longer coastlines tend to develop their navies. The coefficient of the length of a country’s borders with its non-NATO members is positive and significant, indicating that states that share longer borders with non-NATO members tend to have larger fleets.

Years in NATO is positive and significant in Models 1 and 2, implying that long-time members have greater naval power. Threat is negative and significant in both models, suggesting that tonnage to GDP is lower among NATO members facing a greater state-centric threat from Russia. Conversely, Russia’s Naval Power is insignificant in both models, indicating that in our time frame, NATO members’ naval power was not influenced by changes in the Russian fleet. Alliance Naval Power is negative in both models, as expected, but achieves statistical significance only in Model 1, which indicates that members will tend to free ride in building their naval capabilities as the naval power of all other members increases. GDP and GDP per Capita are negative and significant in Model 1, indicating that larger NATO economies have a lower tonnage to GDP ratio. These variables are insignificant in Model 2.

Competition is positive yet statistically insignificant in Model 2 but surprisingly, negative and significant in Model 1. This suggests that the previously documented tendency of states in competitive geopolitical environments to gravitate toward maintaining a strong navy does not hold for NATO members within our study’s timeframe.

Turning to Models 3 and 4, the negative and significant coefficient of Wales Pledge suggests that, on average, the total tonnage of non-US NATO allies was higher before 2014. Substantively, the period following the Wales Pledge is associated with an average decline of 35,086 in total tonnage. In Model 4, where the dependent variable is the natural logarithm of total tonnage, findings suggest that the total tonnage of non-US NATO allies was 18 percent lower in the post-Wales Pledge period.

Robustness checks

We subjected our results to robustness tests. First, we code alternative specifications for Naval Power in the Online Appendix. We also include additional controls commonly used in the burden-sharing and naval expansion literature. Overall, these specifications did not change the substance of the results presented.

Secondly, we follow a growing body of studies on burden sharing and the demand for different military platforms that employ an Error Correction Model (ECM) (Becker, Citation2021; Becker et al., Citation2023: Cavatorta & Smith, Citation2017). An ECM regresses a first-differenced dependent variable on its lagged level and the first difference and lagged levels of all time-varying variables. This allows for the estimation of short-term and long-term effects in a single regression. The model is based on the theoretical assumption that the relationship between the dependent and independent variables resembles a dynamic movement toward equilibrium. In our context, it would be reasonable to assume that while shifting resources away from the maritime domain might have occurred very close to the Wales Pledge and the Russian invasion of Crimea, the comprehensive impact of changes in naval investments appears over a longer timeframe.

Methodologically, ECM is appropriate for stationary, non-cointegrated data. To test for cointegration of the dependent and independent variables, we performed Westerlund’s (Citation2005) tests of cointegration, which indicated that the data were not cointegrated. We also performed the Dickey-Fuller Fisher-type test, rejecting the presence of unit roots.Footnote4 Model 5 in presents the results of the ECM estimations, which suggest that the Wales Pledge had both a short-term and long-term negative effect on non-US NATO members’ tonnage to GDP ratio.

Table 2. Robustness Tests.

Model 6 reports the results obtained with a dynamic pooled mean group (PMG) ARDL model with fixed effects. In this method, the long-run slope coefficients are restricted to be equal across all panels (in our case, all non-US NATO members), and the short-run coefficients are allowed to vary across panels. Once again, the long-run and the short-run coefficients of Wales Pledge are negative and statistically significant. In Model 7, we present the results of the Arellano-Bond estimator, designed for datasets with multiple panels and a limited span of years. In our case, the dataset spans 11 years and includes 22 members. This estimator takes the first difference of the regression equation and then uses the first and second lagged dependent variable as an instrument for differenced lags of the dependent variable. Once again, the negative and statistically significant coefficient of Wales Pledge suggests that the post-Wales Pledge period is associated with a reduction in tonnage to GDP ratio.

Finally, we employ a difference-in-difference model to ensure that our results do not reflect a global trend of reducing naval power unrelated to NATO dynamics. Difference-in-differences is often used to explore the impact of implementing a new policy by comparing the difference between the “treated” units and the “control” units that are not exposed to the policy. Accordingly, we refer to the Wales Pledge as the policy and to NATO states as the “treated” group. In Model 8, the estimation compares the changes in NATO members’ naval power before and after 2014 with changes over the same period for all other countries in the international system. In Model 9, the control group refers only to other non-NATO US allies.Footnote5

We included all the controls used in the previous models yet excluded controls that specifically refer to NATO. The difference-in-differences method is applicable where the assumption of parallel trends is satisfied. In our context, we must ensure that the development of naval power in NATO members and other countries in the international system followed a parallel path in the pre-Wales Pledge period to verify that the DID method is applicable. While we could support this assumption in models setting total tonnage as the dependent variable, we failed to support it where the dependent variable is Total Tonnage to GDP. We, therefore, do not report the results of the later models.

includes the results of parallel-trends tests whose null hypothesis is that pretreatment period trajectories are parallel. The results indicate that we cannot reject this null hypothesis, meaning that linear trends are parallel. We also performed a Granger-type causality model where the null hypothesis is that there is no effect in anticipation of treatment. The results indicate that we cannot reject the null hypothesis, meaning that we should not be concerned that the difference in the outcomes results from developments that predate the “treatment.” Models 8 and 9 suggest that when focusing on total tonnage, the results provide support for our argument. The Average Treatment Effect on the Treated (ATET) is negative and statistically significant in both models. The results imply that the total tonnage of non-US NATO members is lower, relative to a case where they had not agreed in 2014 to increase overall defense spending.

Table 3. Robustness Test, Difference-in-Differences Specification.

Ideally, we would also introduce a DID model with a control group of non-NATO members that shared European NATO members’ concerns about the 2014 Russian invasion and perceived similar levels of US commitment to protecting their wartime SLOCs. This design would allow for isolating the specific effects of the NATO alliance dynamic following the Wales Pledge, distinguishing it from the concern generated by the Russian invasion. Regrettably, such a control group that could include a sufficient number of observations does not exist: Most non-NATO allies of the United States were not as directly impacted by the changing strategic environment resulting from the invasion. Furthermore, the non-NATO European states, some of whom were highly concerned about the changing strategic environment, lacked a formal defense alliance with the United States. In Model 10, the control group is comprised of non-NATO EU members and countries allied with the United States that imposed sanctions against Russia following the 2014 invasion. Most non-NATO EU countries could expect that blocking their maritime trade would inflict damage upon EU NATO members, and thus, they might have more confidence that such a scenario would become an interest of NATO. Non-NATO US allies that imposed sanctions on Russia sent a relatively “costly signal” to express their concern about the geopolitical implications of Russian aggression. As in the other two DID models, the ATET in Model 10 is negative and statistically significant.

Alternative explanations

While our theoretical mechanism focuses on alliance dynamics, one might worry that the reported reduction in naval power simply reflects the altered threat landscape following Russia’s 2014 Crimean invasion. That is to say, the annexation of Crimea motivated allies to bolster land forces at the expense of other capabilities. Consequently, regardless of alliance commitments, the reduction in naval power is driven by individual allies’ growing concerns about potential land warfare. Alternatively, it might be argued that the reduction in naval power is a result of a more coordinated division of labor within NATO that was driven by the need to restore NATO’s ability to conduct a large-scale maneuver. We believe that these two alternative explanations alone cannot account for our reported results, nor do they undermine our proposed causal mechanism.

Indeed, Russia's 2014 invasion of Crimea redirected significant attention to the land dimension of military strategy. While the invasion underscored the necessity for enhanced land maneuverability, it simultaneously increased the emphasis on naval power, highlighting the need for offensive and defensive maritime capabilities (Stöhs, Citation2024, p. 445). European strategy documents increasingly called for naval modernization, and while some steps toward this goal have been initiated, budget constraints often delayed the commissioning of new naval platforms. Although the response to the Crimea annexation might have led some allies to focus more on land forces, it does not undermine our core mechanism: The degree to which allies can prioritize one domain at the expense of another is related to their confidence that the patron will secure one of these domains.

The policy shifts following 2022 Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine exemplify the above argument. Three days after the invasion, in what is known as the Zeitenwende speech, German Chancellor Olaf Scholz announced the creation of a special 100 billion Euro fund for critical investments and armament initiatives. Presenting this proposal to the German Parliament, Chancellor Scholz stated, “This commitment extends beyond merely honoring our pledge to escalate defense spending to two percent of our GDP by 2024. It is an essential step for our own national security” (The Federal Government, Citation2022). Thus, whether this declaration reflects the German government’s efforts to meet the 2% GDP defense spending goal, its concerns about the Bundeswehr’s readiness, or probably a combination of these and other issues exacerbated by the war, our theory expects that Germany’s need to increase defense expenditure will intensify the dynamics of burden shifting we underscore.

The implementation of Chancellor Scholz’s explicit pledge for a special defense fund has become increasingly ambiguous. Contrary to initial expectations, it appears that the fund will not be used in addition to existing efforts to comply with the 2% guideline but rather will be used to reach that target. According to an announcement by the German government in late 2022, around 41% of the special fund is designed to enhance air capabilities, 25% to digitize the Bundeswehr, 20% to enhance land systems, and less than 11% targets maritime capabilities (The Military Balance, Citation2023, p. 54). Given Germany’s status as one of the world’s largest export-driven economies, growing concerns over China’s geopolitical challenges, and the significant impact of the Nord Stream pipeline attacks in September 2022, which exposed the vulnerability of critical maritime infrastructure, one might have expected a greater emphasis on maritime defense spending. While a range of factors influence decision-making about how to allocate the defense budget, our argument is that the ability of Germany and other European allies to allocate a small portion of their newly allocated funds to maritime capabilities might be related to its confidence that the United States will not abandon its alliance maritime commitments.

Another alternative explanation for our findings is that the endorsement of the Defence Investment Pledge marks a shift to a more coordinated division of labor, echoing the dynamics of the Cold War era. A key principle of the Cold War’s division of labor within NATO was that the United States and traditional European naval powers undertook the responsibility of securing SLOCs while other European allies specialized in defending their coastal regions (Mattelaer, Citation2016, p. 28). At the time, several European allies also possessed specialized skills in areas such as anti-submarine warfare (ASW) and minesweeping (Gannon, Citation2021, p. 35). Thus, if the Wales Pledge indeed revived these principles, our results would not reflect burden shifting but rather imply a more cooperative, efficient, and fair burden sharing. However, it is difficult to theoretically or empirically support the notion that the Wales Pledge and later decisions led to such a comprehensive, collectively agreed transformation in the division of labor.

Indeed, the NATO Defence Planning Process (NDPP), which is the main procedure used to convert NATO’s strategic vision into the allocation of specific military requirements, appeared to be more cooperative and effective during the 2014–2018 iteration. This was particularly evident during the second and the third stages of the NDPP, which defines the pool of Minimum Capability Requirements (MCR) and allocates requirements by establishing specific capability targets for each ally (Deni, Citation2020). Nonetheless, while allies’ endorsement of expanding MRC indicates a more cooperative defense planning process, it is far from indicating a strategic decision to restore the Cold War era division of labor described above.

The NDPP is designed to harmonize national and international planning activities to enable the achievement of NATO’s strategic goals expressed in key documents, yet it is not the strategy itself (Becker & Bell, Citation2020). The main strategy documents that shape the development of the Political Guidance of the DNPP do not imply strategic principles that would restore a Cold War model of the division of labor in the maritime domain. While some experts called for adapting NATO maritime strategy, the core principle outlined in NATO's, Citation2011 Alliance Maritime Strategy remained unchanged following Crimea's annexation (Stöhs, Citation2024, p. 400).

In 2014, the EU introduced the European Maritime Security Strategy (EUMSS), designed to serve as the framework for addressing security challenges at sea. The EUMSS, along with its action plan, subsequent updates, and related maritime initiatives, outlines the need to enhance the division of labor between EU members. However, the initiatives to implement the EUMSS that focused on improving labor division predominantly tackle specific EU concerns, such as immigration, or emphasize broad global ambitions, such as the promotion of rules-based governance at sea (Bueger & Edmunds, Citation2023; Stöhs, Citation2024, p. 400). Yet, until Russia's 2022 full-scale invasion, EUMSS updates largely overlooked the issue of division of labor in regard to traditional naval security issues.

Gannon (Citation2021) demonstrates that high interest alignment is crucial for fostering a comprehensive cooperative division of labor among allies. Russia’s 2014 invasion marks a turning point, ending the “foe of peace” era where allies lacked a specific common perceived threat (Becker & Bell, Citation2020). Nonetheless, disagreements about strategic goals and burden-sharing issues persisted among European allies and between the two sides of the Atlantic.

Since 2014, NATO and the EU have been conducting coordinated naval exercises and operations, although these efforts to strengthen cooperation have not prevented disagreements on collective responses to immediate threats. A prominent example was the reluctance of almost all European members to join the US—and UK-led International Maritime Security Construct (IMSC) in the Strait of Hormuz following Iranian attacks on oil tankers in 2019. European members’ reluctance to join the IMSC was partly attributed to their discomfort with the Trump administration's “maximum pressure” approach toward Iran (Bueger & Edmunds, Citation2023, p. 80).

Strategic interests were also far from being aligned with the Biden administration. A notable example highlighting the differences in maritime interest strategies and the lack of defense industry coordination among allies emerged with the 2021 establishment of the Australia-UK-US defense trilateral partnership, AUKUS. This new agreement not only blindsided France and prompted Australia to cancel a multi-billion dollar submarine contract with France, but also affected France’s Indo-Pacific geopolitical ambitions (“France’s humiliation by America will have lasting effects,” Citation2021).

Thus, despite some progress made in process design to harmonize capabilities, the post-Wales period is far from characterized by political conditions that could promote an explicit, comprehensive, coordinated shift in the division of labor.

Conclusion

Just as disaggregating military expenditure may improve analyses of burden sharing, we argue in this study that the literature should also disaggregate the commitments that the patron is more or less likely to credibly threaten to abandon. Allies are less likely to invest in capabilities to counter threats that the patron is less likely to abandon. This pattern intensifies when allies are compelled to increase their military budgets or spend more on equipment modernization.

We tested our broad theoretical argument by exploring the impact of the Wales Pledge on non-US NATO members. We argue that the need to meet their obligation to spend 2% of their GDP on defense and 20% of their defense budgets on equipment modernization increased non-US NATO members’ tendency to shift military spending from domains in which the patron is less likely to credibly signal its intention to abandon. We then explained why the maritime domain is such a predominant domain for burden shifting. Using a novel dataset of states’ naval capabilities, we found consistent and robust support for our hypothesis that the post-Wales Pledge period is associated with a reduction of the naval power of non-US NATO members.

To our knowledge, this study is the first to theoretically and empirically explore the maritime domain within the well-established literature on burden sharing in asymmetric alliances. We focused exclusively on naval power as an initial step toward linking the disaggregation of military capabilities to the disaggregation of the specific threats the patron is less likely to abandon. Admittedly, focusing on NATO’s naval capabilities in the context of the Wales Pledge may be regarded as an “easy” test for our theory. The characteristics of naval power, along with the US commitment to protect the freedom of navigation and the structure of NATO, are all factors that reduce the United States’ ability to credibly signal an intention to renege on its commitment to secure its allies’ sea assets.

We expect that the argument and findings presented in this study also apply to additional domains and capabilities in the air and on land. Thus, further disaggregation of specific capabilities and threats is warranted to establish the causal mechanism of our theory. Such a research agenda would contribute to the evolving scholarly efforts to move beyond the use of a simple military spending indicator when evaluating burden sharing. More specifically, adopting our proposed disaggregation approach would allow us to better assess the effectiveness of specific policies designed to foster fairer burden sharing among alliance members, such as the Wales Pledge.

Appendix.docx

Download MS Word (53 KB)Acknowledgments

We wish to thank the editors, two anonymous reviewers, and numerous colleagues for helpful feedback.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Replications materials available at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/J0ZXWV

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 All GDP data in the main text are measured in constant 2015 US dollars. In the Appendix, we reran all models with GDP expressed in nominal current US dollars.

2 Replacing GDP with Population has produced very similar results (see Appendix).

3 In the Appendix we also controlled for allies’ annual GDP growth, and replaced nominal GDP and GDP per capita with GDP in constant 2015 data. Our results are robust to these specifications.

4 The P-value for the Westerlund test is 0.41, indicating that we cannot reject the null hypothesis of no cointegration. Using STATA’s xtcointtest procedure, we find that the inverse chi-squared score is 63 with P-value = 0.04, indicating that we can reject the null hypothesis of unit roots.

5 Following Blankenship (Citation2021), we excluded Latin American countries from the control group, many of which are allied with the US through the Inter-American Treaty of Reciprocal Assistance.

6 The ORCID should end with a 6. The right ORCID is 0000-0002-9635-6516

Reference list

- Alozious, J. (2022). NATO’s two percent guideline: A demand for military expenditure perspective. Defence and Peace Economics, 33(4), 475–488. https://doi.org/10.1080/10242694.2021.1940649

- Becker, J. (2019). Accidental rivals? EU fiscal rules, NATO, and transatlantic burden-sharing. Journal of Peace Research, 56(5), 697–713. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343319829690

- Becker, J. (2021). Rusty guns and buttery soldiers: Unemployment and the domestic origins of defense spending. European Political Science Review, 13(3), 307–330. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773921000102

- Becker, J., & Bell, R. (2020). Defense planning in the fog of peace: The transatlantic currency conversion conundrum. European Security, 29(2), 125–148. https://doi.org/10.1080/09662839.2020.1716337

- Becker, J., Kreps, S. E., Poast, P., & Terman, R. (2023). Transatlantic shakedown: Presidential shaming and NATO burden sharing. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 68(2-3), 195–229. https://doi.org/10.1177/00220027231167840

- Becker, J., & Malesky, E. (2017). The continent or the “Grand Large”? Strategic culture and operational burden-sharing in NATO. International Studies Quarterly, 61(1), 163–180. https://doi.org/10.1093/isq/sqw039

- Beckley, M. (2015). The myth of entangling alliances: Reassessing the security risks of U.S. defense pacts. International Security, 39(4), 7–48. https://doi.org/10.1162/ISEC_a_00197

- Bellais, R. (2017). Against the odds: The evolution of the European naval shipbuilding industry. The Economics of Peace and Security Journal, 12(1), 5–11.

- Blankenship, B. (2020). Promises under pressure: Statements of reassurance in US alliances. International Studies Quarterly, 64(4), 1017–1030. https://doi.org/10.1093/isq/sqaa071

- Blankenship, B. (2021). The price of protection: Explaining success and failure of US alliance burden-sharing pressure. Security Studies, 30(5), 691–724. https://doi.org/10.1080/09636412.2021.2018624

- Blankenship, B., & Lin-Greenberg, E. (2022). Trivial tripwires?: Military capabilities and alliance reassurance. Security Studies, 31(1), 92–117. https://doi.org/10.1080/09636412.2022.2038662

- Blum, J., & Potrafke, N. (2020). Does a change of government influence compliance with international agreements? Empirical evidence for the NATO two percent target. Defence and Peace Economics, 31(7), 743–761. https://doi.org/10.1080/10242694.2019.1575141

- Bueger, C., & Edmunds, T. (2023). The European Union’s quest to become a global maritime-security provider. Naval War College Review, 76(2), 67–86.

- Bueger, C., & Mallin, F. (2023). Blue paradigms: Understanding the intellectual revolution in global ocean politics. International Affairs, 99(4), 1719–1739. https://doi.org/10.1093/ia/iiad124

- Cavatorta, E., & Smith, R. P. (2017). Factor models in panels with cross-sectional dependence: An application to the extended SIPRI military expenditure data. Defence and Peace Economics, 28(4), 437–456. https://doi.org/10.1080/10242694.2016.1261428

- Caverley, J. D., & Dombrowski, P. (2020). Too important to be left to the admirals: The need to study maritime great-power competition. Security Studies, 29(4), 579–600. https://doi.org/10.1080/09636412.2020.1811448

- CIA. (2023). The World Factbook.

- Cooper, S., & Stiles, K. W. (2021). Who commits the most to NATO? It depends on how we measure commitment. Journal of Peace Research, 58(6), 1194–1206. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343320980820

- Cornes, R., & Sandler, T. (1984). Easy riders, joint production, and public goods. The Economic Journal, 94(375), 580–598. https://doi.org/10.2307/2232704

- Crawford, T. W. (2003). Pivotal deterrence: Third-party statecraft and the pursuit of peace. Cornell University Press.

- Crisher, B. B. (2017). Naval power, endogeneity, and long-distance disputes. Research & Politics, 4(1), 205316801769170. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053168017691700

- Crisher, B. B., & Souva, M. (2014). Power at sea: A naval power dataset, 1865–2011. International Interactions, 40(4), 602–629. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050629.2014.918039

- Deni, J. R. (2020). Security threats, American pressure, and the role of key personnel: How NATO’s defence planning is alleviating the burden-sharing dilemma. (Monograph No. 919). Carlisle Barracks, PA: US Army War College Press. https://press.armywarcollege.edu/monographs/919.

- European Union Global Strategy. (2016). Shared vision, common action: A stronger Europe. https://www.eeas.europa.eu/sites/default/files/eugs_review_web_0.pdf.

- Feldman, N., Eiran, E., & Rubin, A. (2021). Naval power and effects of third-party trade on conflict. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 65(2–3), 342–371. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002720958180

- Feldman, N., & Shipton, M. (2022). Naval power, merchant fleets, and the impact of conflict on trade. Security Studies, 31(5), 857–884. https://doi.org/10.1080/09636412.2022.2153732

- France’s humiliation by America will have lasting effects. (2021, September 23). The Economist. https://www.economist.com/europe/2021/09/23/frances-humiliation-by-america-will-have-lasting-effects.

- Gannon, J. A. (2021). Use their force: Interstate security alignments and the distribution of military capabilities [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. University of California San Diego.

- Gannon, J. A., & Kent, D. (2021). Keeping your friends close, but acquaintances closer: Why weakly allied states make committed coalition partners. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 65(5), 889–918. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002720978800

- Gartzke, E., & Lindsay, J. R. (2020). The influence of sea power on politics: Domain- and platform-specific attributes of material capabilities. Security Studies, 29(4), 601–636. https://doi.org/10.1080/09636412.2020.1811450

- George, J., & Sandler, T. (2018). Demand for military spending in NATO, 1968–2015: A spatial panel approach. European Journal of Political Economy, 53, 222–236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2017.09.002

- Gerzhoy, G. (2015). Alliance coercion and nuclear restraint: How the United States thwarted west Germany’s nuclear ambitions. International Security, 39(4), 91–129. https://doi.org/10.1162/ISEC_a_00198

- Janes. (2008–2020 additions). Janes fighting ships yearbook. Jane’s Group.

- Kim, W., & Sandler, T. (2020). NATO at 70: Pledges, free riding, and benefit-burden concordance. Defence and Peace Economics, 31(4), 400–413. https://doi.org/10.1080/10242694.2019.1640937

- Kinne, B., & Kang, S. (2023). Free riding, network effects, and burden sharing in defense cooperation networks. International Organization, 77(2), 405–439. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818322000315

- Levy, J. S., & Thompson, W. R. (2010). Balancing on land and at sea: Do states ally against the leading global power? International Security, 35(1), 7–43. https://doi.org/10.1162/ISEC_a_00001

- Machain, C. M., & Morgan, T. C. (2013). The effect of US troop deployment on host states’ foreign policy. Armed Forces & Society, 39(1), 102–123. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095327X12442306

- Markowitz, J., & Fariss, C. (2018). Power, proximity, and democracy. Journal of Peace Research, 55(1), 78–93. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343317727328

- Markowitz, J., Fariss, C., & McMahon, R. B. (2019). Producing goods and projecting power: How what You make influences what you take. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 63(6), 1368–1402. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002718789735

- Mattelaer, A. (2016). Revisiting the principles of NATO burden-sharing. Parameters, 46(1), 25–33.

- NATO. (2022). NATO 2022 Strategic Concept. https://www.nato.int/nato_static_fl2014/assets/pdf/2022/6/pdf/290622-strategic-concept.pdf.

- NATO. (1949). The North Atlantic Treaty. https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/official_texts_17120.htm.