ABSTRACT

Heatwaves, which are escalating in frequency, duration and intensity, have prompted governments worldwide to issue vital health warnings to protect populations. These include urging individuals to stay cool, hydrated, avoid direct sun exposure and minimise strenuous activities. Regrettably, a significant segment of the population faces substantial challenges in accessing these crucial recommendations due to a range of issues termed “systemic cooling poverty”. Systemic cooling poverty encompasses intricate layers of physical, social and intangible infrastructural deficiencies, impeding the provision of essential services necessary to ensure thermal safety during extreme heat episodes. Through an intersectional mixed-method examination, this study brings empirical evidence of the structural factors that exacerbate inequalities in attaining thermal safety among the African–Brazilian community, LGBTQI+ and disabled, living in two favelas in Rio de Janeiro. By shedding light on these lived experiences of cooling poverty, we contribute to the understanding of targeted interventions and policy measures that can alleviate the impacts of extreme heat and safeguard public health and well-being as temperatures rise.

Highlights

We examine the factors that contribute to inequalities and inequities in thermal justice.

We apply the concept of Systemic Cooling Poverty to the context of a tropical megacity Rio de Janeiro.

We show how transport poverty is linked with Systemic Cooling Poverty.

Intersectionality can help identify the patterns of social vulnerabilities in relation to place-based Systemic Cooling Poverty.

1. Introduction

Rising temperatures (Watts et al. Citation2021) are yielding an increasing number of powerful and long-lasting heat spells, winter and summer heatwaves (United Nations Environment and Programme Citation2021). The threat of extreme heat for human health is also one of the key findings of the latest IPCC assessment report: actual health risks related to heat depend on human vulnerability, which relates to the interconnection between pre-existing social, cultural and economic conditions. For example, in central and Latin American countries a major source of vulnerability is the high number of people living in informal settlements (IPCC Citation2022). While historically, research concentrated on elevated surface air temperatures, often overlooks humidity levels (Li, Yuan, and Kopp Citation2020), recent studies indicate that increase in temperatures coupled with rising humidity levels has the potential to exacerbate instances of heat stress and mortality. Although there is considerable variation in dry-hot temperatures across different regions, humans, for instance, have evolved to endure temperatures as high as 38°C (Li, Yuan, and Kopp Citation2020). However, in conditions of elevated humidity, even a temperature of 32°C can induce severe heat stress, with 35°C potentially leading to lethal consequences. It is now increasingly recognised that while dry heat temperatures can be harmful to the survival of human and more-than-human ecologies, humid heat stress presents a significant threat to survivability because the body cannot effectively thermoregulate (Vecellio et al. Citation2022).

As heatwaves increase around the world, governments (UKHSA Citation2023) and international health organisations (WHO Citation2023) advocate three universal heat stress prevention measures: staying hydrated, avoiding direct sunlight during peak hours and limiting physical exertion, especially during the day. However, patterns of inequality and social vulnerability prevent many from attending to these simple recommendations due to social exclusion and physical infrastructural deficiencies. Further, the compounding challenges from rising temperatures and humidity levels are exacerbated by the lack of social and technical cooling infrastructures. For instance, challenges with hydration may arise from water quality or limited access to public water and toilets, but also because of social norms and gender-based violence. In some regions of India, the lack of proper toilet facilities forces both women and men to resort to using bush or pit latrines, with severe consequences for sanitation and hygiene (Srinivasan Citation2015). As a result, women often feel forced to restrict their fluid intake, including water, to avoid frequent visits to open-air toilets to avoid assaults (Panchang, Joshi, and Kale Citation2022). Avoiding sun exposure may also not be a personal choice as it depends on the appropriateness of urban planning and availability of green and shaded areas (Jamei et al. Citation2016). Finally, avoiding physical exertion during the hottest hours may not be attainable by people because of systemic lack of opportunities are forced into outdoor informal occupations. Research in South East Asia shows how informal workers (such as seasonal sugarcane cutters) are more exposed to heat stress than regular workers in formal employment (Boonruksa et al. Citation2020).

The aim of this paper is to lay out how inaccessible and inefficient cooling infrastructures hinder the realisation of basic health recommendations during heatwaves among the most fragile segment of the population. We use the concept of “systemic cooling poverty” Mazzone et al. (Citation2023) to examine the circumstances in which individuals lack protection from excessive heat across various facets of daily life, encompassing activities such as commuting to work, staying at home or seeking shelter during extreme heatwaves. The study focuses on the tropical megacity of Rio de Janeiro, characterised by consistently high compound levels of heat and humidity throughout the year. We utilise a mixed-method analysis to gain insights into the lived experiences of Black communities residing in the favelas and to explore how inadequate infrastructures pose persistent threats to their health and well-being during heatwaves. We employ an intersectionality framework as a theoretical guide to both select our participants and analyse the compounded disadvantages that shape thermal inequities. By recognising the structural and historical causes of such inequities, we help respond to Sultana's call to decolonise climate (Sultana Citation2022). Intersectionality also serves as ontological ground through which we justify the use of mixed-methods and answer recent invocations for integration between different disciplines in climate justice (Colucci, Vecellio, and Allen Citation2023; Sultana Citation2022; Amorim-Maia et al. Citation2022; Mikulewicz et al. Citation2023). Through our empirical research, the study helps contribute to an understanding of thermal injustice in the Global South.

2. Paving the way for thermal justice

Qualitative research from the social sciences on heatwaves is re-surfacing (see Bosca Citation2023; Tawsif, Shafiul Alam, and Al-Maruf Citation2022; Klinenberg, Araos, and Koslov Citation2020), especially in light of the temperature-breaking extremes across the world in recent summers. Sociologists, physical and human geographers have long observed the detrimental effects of climate disasters on the intensification of place-based inequalities (Klinenberg Citation2002; Cutter, Boruff, and Shirley Citation2003). We now know that social inequality rooted in individual characteristics (gender, ethnicity, race, sexuality) and economic conditions (income disparities, low-income, migration status) tend to be entwined with spatial segregation (urban density, extreme land use, scarce ventilation, absence of green areas and waterbodies) where the most vulnerable groups tend to be located (Mitchell and Chakraborty Citation2019; Cutter et al. Citation2008). Yet, while individual vulnerabilities have been characterised in heat-related research (see Klinenberg Citation2002; Ergas, McKinney, and Bell Citation2021b), the cumulative intersectional disadvantages of extreme heat events among particular groups tend to be overlooked. A recent publication by Colucci and colleagues recommends the adoption of multidisciplinary approaches to generate intersectional knowledge addressing thermal violence within the carceral system (Colucci, Vecellio, and Allen Citation2021). Yet, there is still scarce empirical work on intersectionality and climate extremes, and the broad literature on climate adaptation has only marginally explored marginalised communities (Turek-Hankins et al. Citation2021).

The roots of thermal inequalities and inequities can often be found in historical geopolitical factors which have destabilised, dispossessed and eradicated a people-centred local adaptive knowledge. For example, in initial years, the standardisation of building codes were shaped by metrics of thermal comfort tailored to a specific group – primarily abled, Nordic white males – which exerted influence over the global construction industry and design practices (see Fanger Citation1972). Further, the inadequacy of cooling infrastructures reflect climate coloniality (Sultana Citation2022; Mercer and Simpson Citation2023) and manifest as outcomes of colonial influences in urban building design and architecture and knowledges. Indeed, prevailing urban planning models, greenery, architecture and building materials predominantly align with a framework reflective of the environmental attributes and design principles prevalent in the Global North (Sirayi and Beauregard Citation2021; Blundell Citation2020; Loo Citation2017; Muzorewa, Nyawo, and Nyandoro Citation2018; Kake Citation2020) while paving the way for the ubiquity of air conditioning (Shove, Walker, and Brown Citation2014). This standardised approach in constructing designs has endangered indigenous placemaking and materials in the Global South, precipitating a discernible deterioration in people's thermal comfort particularly when mechanical cooling options are not available. As argued by Chang, climate design in the tropics has been shaped by colonial medical ideas and the interests of the US air-conditioning corporations (Chang Citation2016). Concurrently, the indigenous communities’ traditional knowledge pertaining to strategies for maintaining optimal bodily and spatial coolness has been supplanted by colonial influences and capitalistic interests (Hobart Citation2023).

In response to this context, we frame thermal justice as the accessibility of all people to opportunities that can achieve safe body temperatures and thermal comfort. Thermal justice is intricately linked to both global climatic events and micro-climates, making it closely intertwined with the specific geographies and morphologies of local territories. To date, thermal justice lacks a definition, but it can be seen as a distinct phenomenon at the crossroads between environmental (Walker Citation2020) and spatial justice (Soja Citation2013). While all these “justices” are concerned with the environment, they all focus on different scales and actions. For environmental justice, the core idea is to address environmental inequalities and focus on empowering marginalised communities to have a voice in shaping environmental policies that affect them (Cole and Foster Citation2001; Schlosberg Citation1999; Walker Citation2020). Spatial justice is instead concerned by the role of geography in justice (Soja Citation2013) focusing on the local spatial distribution of resources and key services for human well-being. It highlights the distributive and procedural aspects of such inequalities at urban level and on how public goods can be equitably accessed by urban populations (Soja Citation2013).

Thermal justice encompasses both global and local dimensions, as it addresses the impact of anthropogenic global climate change which leads to rising mean global temperature and its localised effects of prolonged and intensified heatwaves. It focuses on the uneven distribution of negative externalities, such as the heat emissions from cooling technologies affecting individuals living and working outdoors, as well as heat retention caused by dense urban environments. Moreover, thermal justice also incorporates aspects of spatial justice concerning the unfair allocation and use of public goods like green cooling infrastructures, blue surfaces (e.g. fountains) and public services (e.g. public toilets and cooling centres). Together, it necessitates a thorough examination of exclusionary and segregative patterns that govern thermal rights in environments experiencing escalating temperatures.

2.1 Finding the systemic causes of thermal inequities

Identifying and addressing the systemic causes perpetuating thermal inequality in increasingly hot environments promotes thermal justice, which seeks to rectify the disparities and ensure equitable access to cooling resources and amenities for all members of society.

As argued by Mazzone et al. (Citation2023), there are a number of systemic aspects that reinforce thermal inequalities in the face of increasing temperatures and humidity. Systemic Cooling Poverty is considered as “the condition in which organisations, households and individuals are exposed to the detrimental effects of increasing humid heat stress as result of inadequate infrastructures. Such infrastructures can be physical, such as passive retrofit solutions, cold chains or personal technological cooling devices; social, such as networks of support and social infrastructures; or intangible, such as knowledge to intuitively adapt to the combined effects of heat and humidity”. The authors provide a framework identifying the physical, social and intangible infrastructures of exclusion from accessing cooling needs.

Using the framing of systemic cooling poverty complements previous studies linking spatial justice with energy poverty (Yenneti, Day, and Golubchikov Citation2016; Bouzarovski and Simcock Citation2017). In their spatialisation of energy poverty, Bouzarovski and Simcock (Citation2017) delve deeper into how domestic energy deprivations are intricately linked to the entire energy system (production and consumption), local economy and infrastructures (Bouzarovski and Simcock Citation2017). While Bouzarovski and Simcock (Citation2017) provide a comprehensive understanding of the interlinkages between energy poverty and spatial injustices, gaps in analysis remain. For example, the infrastructural implications of deficient urban planning and the geometric layout of urban areas on outdoor and indoor thermal comfort, such as of urban heat islands where absorptive surfaces in buildings, concrete, asphalt and other artificial surfaces trap heat (Santamouris Citation2014; Salata et al. Citation2017; He et al. Citation2021). Other examples include urban geometry and building orientation that reduce shading and ventilation opportunities (Triyuly, Triyadi, and Wonorahardjo Citation2021). Local micro-climates can also be further deteriorated by the intensity of transport and urban pollution which act as a magnifier for the entrapment of heat (Kammuang-Lue et al. Citation2015). The heat dumped by commercial activities, air conditioning in buildings and transport can also increment outdoor temperatures (Wen and Lian Citation2009). In addition to these issues, studies within the space and energy poverty literature often overlook the significance of passive cooling solutions such as urban greenery, water bodies, green roofs, reflective surfaces and shading (Samuel et al. Citation2013). Nonetheless, research in urban planning highlights their crucial role as micro-climatic factors capable of enhancing both indoor and outdoor thermal comfort (Ghosh and Das Citation2018). Furthermore, thermal comfort also depends on other socio-material factors and practices such as clothing, diets, hydration, food intake, human metabolism and habits (Khosla et al. Citation2022). As such, people who lack access to appropriate clothing, food, hydration and nutrition for their thermal comfort are essential to addressing thermal justice.

Starosielski calls “thermal autonomy” “a politics that is attentive to people's ability to regulate and mediate their own position within the thermal world” (p.23) (Starosielski Citation2021). Such autonomy we argue can be achieved if passive sustainable infrastructures and environmental resources are in place and available for all to benefit. For example, in extremely hot days, access to cold drinking water can be a “thermal right” (Starosielski Citation2021, p. 22). Thermal rights in certain regions of the world are constantly denied or hindered by governmental neglect, which results in withholding of safe water, available natural shading (Langenheim et al. Citation2020), or the inaccessibility of food. For example, research in the USA found that the high price of fresh water-rich food (vegetables and fruit) discourages low-income people, especially in urban racialised neighbourhoods (Larson, Story, and Nelson Citation2009). The withholding of proper sanitation and drinking water is also another crucial important denial of a fundamental thermal right.

To grasp how spatial injustices frequently perpetuate patterns of inequality and inequity, it is important to examine how individuals can escape from insufficient infrastructural heat traps. Mobility poverty is a term used to indicate the systemic lack of transportation options and limited mobility choices for individuals or communities (Lowans et al. Citation2021). Unlike transport poverty, which tends to be framed predominantly around the financial difficulties encountered by low-income people, mobility poverty encompasses geographical and physical impediments to access essential services, opportunities and resources due to inadequate transportation infrastructure (Kuttler and Moraglio Citation2021). The consequences of mobility poverty can result in social exclusion, limited job prospects, reduced access to healthcare and education, and overall diminished quality of life (Furszyfer, Dylan, and Sovacool Citation2023). Such a framing of mobility poverty is aligned with systemic cooling poverty in the shared focus on infrastructural deficiencies and place-vulnerability. An inaccessible, unsafe or excessively costly transportation system limits people's mobility and, subsequently, their capacity to find cooler places to regulate their internal temperatures. In this way, the inadequacies in the transportation sector intertwine with thermal rights, which include the ability to seek refuge in nearby cooling centres (such as blue/green spaces, libraries, hospitals and other conditioned environments) during extreme heat events. We argue for an approach to thermal justice that is holistic in examining the distribution of thermal inequities within a particular context and draws from and goes beyond approaches to climate justice, environmental justice and energy justice.

3. Methodology

3.1 Location

Infamously known for its numerous marginal settlements called favelas, Rio hosts over 763 favelas with 1.7 million people, almost one-sixth of Rio's total population of 6 million (IBGE Citation2022). The Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE) responsible for the national census calculates that 20% of the total residences in Rio de Janeiro can be categorised as informal and irregular (in Portuguese: aglomerados subnormais, IBGE Citation2010). Annual Wet-Bulb temperatures in Rio de Janeiro State for the period 1991–2020 reached 22°C, with annual peak of 25°C, and an annual relative humidity of 79% for the same period (Metereologia Citation2023). Record breaking heat has become a recurrent event, rather than occasional occurrence. On 15th January 2023, Rio de Janeiro reached 40°C, one of the highest temperatures ever registered in the city, with the neighbourhood of Irajá registering thermic sensationFootnote1 of 53°C. A month later, on the 5th of February 2023, Rio hit additional record-breaking temperatures of 41°C in the neighbourhood of Santa Cruz and a thermic sensation of 58°C. Record breaking events also occur during winter, and on 5th August 2022 Rio registered an unusual 38.5°C for this time of the year (Metereologia Citation2023). Such temperatures, however, do not consider different hotspots. For example, there are spaces which lack meteorological sensors, such as informal settlements, or areas of the city which usually see a concentration of heat because of agglomerations of people and infrastructures which experience higher than these registered temperatures.

3.2 Theoretical framework

The key theoretical approach guiding this research is intersectionality. Intersectionality was first introduced by Kimberlé Crenshaw (Crenshaw Citation1989) within critical theory and black feminist studies, showing the multidimensionality and concurrent cumulative social disadvantages of different social identities. An intersectionality framework considers the interconnected nature of multiple systems of oppression. These systems include, but are not limited to, categories such as race, gender, class, sexuality, ethnicity, nationality, indigeneity, ability, religion, species, scale (referring to different levels of analysis), and distinctions between rural and urban contexts as well as global divisions between the Global South and Global North (Ergas, McKinney, and Bell Citation2021a). Intersectionality links with climate justice in the shared focus on marginalised people as per (Mikulewicz et al. Citation2023): “intersectionality helps understand vulnerability as a process mediated by structural forces that are both local and global such as patriarchy, racism, colonialism and capitalism” (Mikulewicz et al. Citation2023, p. 4). The cumulative effect of the intersection of oppressed social identities such as being a woman and LBGTQI+,Footnote2 and black, for example, shifts away essentialist categorisation of being “women” or “indigenous” and instead provides a more nuanced contextualisation of the places, spaces and temporalities which can disproportionately disadvantage some people over others. We align with Anthias (Anthias Citation2012) in that “intersectionality does not refer to a unitary framework but a range of positions, and that essentially it is a heuristic device for understanding boundaries and hierarchies of social life” (p. 13). We use intersectionality to identify concurrent and cumulative inequalities in relation to excessive heat and use statistical analysis to characterise the association between individuals’ characteristics, including socio-economic, demographic and family conditions, and individual cooling strategies in an urban context. In thermal comfort research, this approach can shed light on how certain groups are more thermally vulnerable than others. Moreover, intersectionality helps decolonise research by including non-Western perspectives, knowledges, lived experiences and, for the purpose of this research, thermal sensations.

In the context of climate extremes, intersectionality emerges as a lens to understand the co-production of injustices. For Bhambra and Newell, the events occurring as a result of climate change (more frequent and destructive heatwaves, flooding) are entangled with capitalistic colonialism which encompasses racial inequality, enslavement and resource exploitation of the Global South (Bhambra and Newell Citation2022).

3.3 Research design

This research utilises a concurrent mixed-method design, combining quantitative and qualitative data. By employing both methods, it strengthens its rigor and comprehensiveness (Teddy and Yu Citation2007), providing multiple angles on cooling practices in the study area. Additionally, this approach triangulates multiple findings to arrive at stronger conclusions. Mixed methods also encourage researchers to think beyond the confines of a single method (Brannen Citation2005). However, there are critiques regarding the epistemological domain due to the contrasting philosophies of knowledge between qualitative and quantitative methods. Realist ontology assumes a single, observable and measurable reality, with the researcher in a positivist role. On the other hand, social constructionists believe in multiple realities constructed by participants, emphasising interpretivist epistemology (Creswell and David Creswell Citation2005). In specific research contexts, these philosophies can be less incompatible. Qualitative approaches can be used to trace general theories and trends, while the quantitative approach is not always limited to positivism (Brannen Citation2005). There is a continuum in research rather than absolute ontological positions, which is what mixed-methods propose. Here, we integrate elements of both qualitative and quantitative approaches, adapting the most suitable method for the specific problem at hand.

Informed by intersectionality theory, two co-authors of this paper, each possessing more than 20 years of experience advocating for the rights of African–Brazilian communities and the homeless population in Rio de Janeiro, have actively undertaken fieldwork. Their objective was to interact with and recruit volunteers within two favelas, Morro de São Carlos and Morro do Fallet. Through a snowballing interview technique, participants residing outside favelas were also recruited to participate in the research. From a climatic point of view, research suggests that favelas can be a hotspot during heatwaves as a result of building clustering, lack of green spaces and geomorphological location (Peres et al. Citation2018). Interviews were conducted between December 2021 and March 2022. For privacy purposes, we used pseudonyms. Semi-Structured Interviews (SSIs from now on) is a qualitative method that starts with a guided protocol and, by the end of the interview, answers from participants may become less structured, providing important details about their personalised experience about a certain topic. From a methodological point of view, the choice of SSIs can be justified as “SSIs accommodate a multiplicity of philosophical assumptions that may reflect feminist, critical, phenomenological and neo-positivist aims”(McIntosh and Morse Citation2015). SSIs can also be suitable for quantitative research, as the structured part of the questionnaire can be used for statistical analysis. We use statistical tools to characterise and visualise the differences in cooling behaviours among participants in a descriptive manner. We acknowledge the small size of the sample, which includes 32 individuals, and therefore its limited statistic accuracy and the lack of external validity. As a result, quantitative results are not used to develop general statements about the relationship between cooling solutions and selected characteristics of the population examined. Rather, they are triangulated with the qualitative insights coming from the non-structured part of the questionnaire.

Following the physical, social and intangible infrastructures framework highlighted in systemic cooling poverty, we asked participants questions covering access and willingness to visit green areas and what the main impediments were. We also asked about the ownership and use of air conditioning, refrigerators and fans and the frequency of such use. We further asked about participant's housing location, materials, and whether sanitation and access to potable water was in place. Such questions were crucial in understanding the multidimensional characteristics of cooling poverty.

4. Results

4.1 Descriptive statistics of respondents’ characteristics and behaviours

shows the challenges and vulnerabilities of people living in informal settlements, especially during hot weather. Informal settlements, characterised by overcrowding, limited infrastructure and inadequate housing, present specific challenges that exacerbate the urban heat island effect. The lack of access to blue and green spaces, inadequate housing conditions, water and sanitation issues, limited coping strategies for heat, limited household appliances, and the differential impacts of heat on marginalised populations are evident. Favelas’ dwellers are negatively impacted by the spatial distribution of green and blue spaces, highlighting the limited access to such areas for most participants (60% green spaces and 93% blue spaces).

Table 1. Factors that contribute to cooling poverty in Rio de Janeiro.

With regard to water infrastructure and housing conditions, reveals alarming statistics within informal settlements. The lack of access to potable water (97%) and sanitation facilities (60%) poses significant health risks and underscores the urgent need for improved infrastructure and services. About half of the participants live in homes with inadequate materials such as metal roofs (53%) and unfinished buildings (50%) further contributing to their vulnerability to heat and other environmental stressors. Most of the favela dwellers interviewed had black (44%) and mixed-race (47%) background with 22% of migrants, especially from Northeast Brazil. Most of the respondents consider themselves female (22%) and 78% call themselves heterosexual.

Table 2. Multidimensional systemic cooling poverty and socio-economic characteristics. Mean values computed across the 32 respondents. High-income individuals are those declaring more than the minimum salary. Number of respondents in parentheses.

In terms of coping strategies to mitigate the effects of heat, individuals tend to wear lighter garments during hot spells, particularly garments made of cotton textiles. Walking barefoot, which is a common strategy in tropical hot climates (see Mazzone and Khosla Citation2021) as a cooling strategy was not reported by any participants due to concerns regarding the potential transmission of diseases. Favelas’ dwellers also have limited ownership and use of air conditioning units. In fact, only five families living in favelas admitted the ownership of AC, while the prevalence of fans (average ownership of 1.8 fans per individual) highlight the reliance on household appliances for cooling purposes, albeit to a limited extent. A significant portion of participants (89%) admitted to illegal consumption of electricity, indicating the challenges faced by residents in accessing and affording electricity through legal means.

shows how the infrastructure and asset aspects of systemic cooling poverty intersect with socio-economic and dwelling characteristics. All respondents consider their home to be too hot, but not all of them have the same access to cooling opportunities. For example, access to blue areas is more common among high-income respondents or those who do not live in a favela, and similarly for the quality of water and sanitation. Income-poor respondents or favela-dwellers are more likely to have an unfinished house, or a place with poor insulation (metal roof) and have illegal access to electricity through gato. Most appliances are equally diffused among rich and poor respondents, with the exception of air-conditioning, which shows bigger differences.

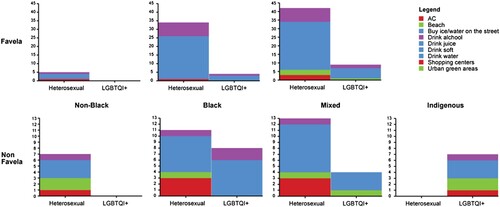

In terms of cooling strategies (), participants not living in a favela show a greater accessibility to behaviours such as going to the beach, visiting green spaces, and going to shopping centres. Living in a favela limits the options available for cooling. Drinking water, but especially juice or alcohol often remains one of the few cooling strategies preferred by our participants. The lack of transportation especially in favelas located uphill, as per our case studies, contributes to reducing accessibility to urban green areas, shopping centres and the beach. also reveals some differences in cooling strategies between black and mixed-race people and other ethnicities, especially when living in favelas, though the sample does not equally represent the different ethnicities and sexual orientations.

We introduce a multivariate regression (see ) to characterise associations between socio-demographic conditions (income, age, presence of children), dwelling type (favela or non-favela) and the probability of adopting four different cooling strategies.Footnote3 The utilisation of AC was primarily associated with the age of the respondents (older individuals exhibit a higher probability of resorting to this cooling strategy), the presence of children and income level. Residents of favelas seem to be more limited in their accessibility to green or blue areas, although the presence of children had a positive effect on the attractiveness of those cooling options. A statistically significant and positive correlation is observed between the consumption of alcoholic beverages and favela dwellers, while individuals residing in these settlements exhibited a reduced likelihood of visiting the beach as a strategy for temperature regulation, which is line with the patterns shown in .

Table 3. Linear probability model for cooling strategies adoption. Robust standard errors in parenthesis.

4.2 Intersectionality analysis

Disabilities can heavily limit the adaptation opportunities available to individuals. Mauro is a 52-year-old man with mobility impairment. His lived experience of heatwaves and increasingly hot summers in Rio de Janeiro shows how people with disabilities are particularly neglected during extreme climatic events (Chakraborty, Grineski, and Collins Citation2019). A recent study on heatwaves mortality in Australia shows how of the 543 fatalities due to heatwaves between 2010 and 2018, most victims were affected by one or multiple physical (heart conditions, diabetes, respiratory and kidney diseases) and mental (schizophrenia) disabilities (about 89%) (Coates et al. Citation2022). However, to our best knowledge there is very limited research aimed at capturing the lived experiences of people with mobility impairments during heatwaves. Mauro can help us shed some light on this neglected issue. In his words:

I would love to take four cold showers a day to seek comfort during heat. But I have some ‘logistic' (emphasis added) issues related to my condition which impede taking showers, so I only wash myself while laying down once a day.

Unlike abled participants, who can take an average of three cold showers per day during summer, the use of water as a cooling strategy for Mauro is not an option which makes him dependent on mechanical cooling with large financial implications. His electricity bill, he says, triples during the summer from air conditioning. He believes that in the summer the electricity bill is also higher because of more frequent use of the refrigerator and washing machine. Changes in sleeping habits have also been reported by Mauro, as they one AC unit and the entire family sleeps in the same room to avail of it. Mauro was further limited in his choices of cooling because of access issues. In his words: “I would love to go to the beach and waterfalls in Rio, but I can't because of accessibility issues”.

As seen in the literature, access to green spaces is a major challenge for mobility impaired individuals. Rio does not lack green spaces. There are at least nine major urban parks (Quinta da Boa Vista, Flamengo Park, Parque Lage to name a few) and smaller parks such as (Praça Paris). Despite the abundance of green areas in Rio de Janeiro, accessibility remains a major issue across intersecting social identities. For example, for 95% of the participants who live in the favela, accessing green or blue spaces is not an option (see also ) not only because of the cost of transportation, but also because of their geographical isolation. As per the words of Fernanda (46, mixed race, single mother of 3):

We stay at home to keep cool. With the children we use hose showers, buckets, and a small plastic swimming pool, which is already broken! Sometimes, I sunbathe with our neighbours who also stay in the community rather than going to the beach. In fact, it's a hassle to get there, especially with the children and transport is expensive. So, we find ways to stay here and cope with the heat. I also find that you get a fake sensation of cooling at the beach. During the time to get there, getting downhill, get transport which does not have AC, it's too hot. And when you get there, the sand is hot, and crowded! It's a nightmare. So, my body gets too hot on the beach, then we go back home, go uphill, and that feeling of heat stays with me even at night. No, I do not think leaving home during the summer is actually good for us. To cool the body, it's best to go to the waterfalls in Tijuca park, but it's too much hassle again. (Fernanda, 46)

Such cooling spaces, when available, may can also be inaccessible for transgender communities because of discrimination issues. As Genevieve (45, transwoman and migrant) describes

I never used public toilets in Rio, this because not only they’re difficult to find, but I always encounter some problems. There aren't designed toilets for us, so it always ends up in a fight […] I avoid going to shopping malls and waterfalls as we suffer from discrimination, everywhere people stare at us. The only place I find accessible is the beach. (Genevieve, 45)

Perceptions of social acceptability vary in different places. Often, these perceptions can have an impact on how people negotiate their thermal comfort in the city. An example is Vicky, a 33-year-old transwoman affected by HIV disability, who has relocated from Minas Gerais to Rio de Janeiro to access gender-affirming hormonal therapy. Unfortunately, her experience in the city has been marred by constant harassment from men and disapproving looks from women. This unwelcoming environment can create challenges for Vicky in navigating her thermal comfort within the city. For instance, she is hesitant to wear light wear clothing to avoid unwanted attention or harassment, although light wear clothing is a recommended cooling strategy during hot and humid days. She also reported to refrain from drinking too much water when she is outdoors to avoid using public toilets. In her words:

It never stops, from the moment I get out of my home to the moment I come back. There is always someone saying some horrible remarks about me and how I look. Men in particular whistle or make degrading comments. The discrimination is heavy here. Transgender women get looked down upon by women and harassed by men. Even when I go to the hospital to get my hormones, I’m called by my former name and there is a lack education on our matters. Everywhere feels unwelcoming. (Vicky, mixed-race, favela dweller and disabled, 33)

Vicky is an example of how concomitant intersecting disadvantages can severely impact access to thermal comfort. She faces inherent disadvantages stemming from her residence in a favela, primarily due to the limited physical infrastructures and the resulting geographic isolation of these communities. This isolation is exacerbated by the scarcity of affordable transportation options and inadequate connections to green and blue areas within the city. Moreover, her LGBTQI+ identity exposes her to social discrimination, impeding her access to heat adaptation strategies, such as adjusting clothing for better thermal comfort. Additionally, as someone with a disability resulting from HIV, she experiences social exclusion, further exacerbating the challenges she faces. Because of these concurrent disadvantages, Vicky lived in shelters and has been homeless for years. This issue is of considerable concern due to the fact that heatwaves disproportionately impact homeless individuals, with specific vulnerabilities observed among LGBTQI+ populations, who may experience additional discrimination and marginalisation within cooling shelters (Rodriguez Citation2021).

Access to water and hydration is one of the most fundamental health recommendations during heat events to prevent heat stress. In the informal settlements of Favela Sao Carlos and Morro Fallet, the lack of public transportation and financial resources hinder access to green and blue spaces, forcing residents to rely on water to cool down during the summer and extreme heat events. To do so, they improvise “cold showers” outdoors, also known as “banho de borracha” or “rubber bath” ().

Recently, the residents of Rio de Janeiro have been facing a water contamination issue that has made consuming water, food, and iced products unsafe for human health. The region's water supply is managed by the state-run water utility company, CEDAE (Companhia Estadual de Águas e Esgotos), which supplies for 70% of the region. The quality of the Guandu spring which supplies Rio de Janeiro “is variable, it has a high source of bacteria of faecal origin and bacteria that degrade aromatic compounds, which lead to sewage contamination”.Footnote4 The water crisis in Rio de Janeiro led to many hospitalisations as water entered in contact with mucous membranes, such as eyes, mouth and nose, for example, because bacteria and viruses can penetrate through them.Footnote5

Fernanda, (46 mixed race, mother of 3) states:

The quality of water in Rio is very bad. Last year there was a huge issue with the authorities in Rio because tap water stank, and it was brown. That's when I got the filter in my tap completely ruined and I had to buy bottled water. The problem is that I live with three children, we consume 2 gallons of water (20 L) per week. Each gallon of water costs 20R$, so it means 80R$ per month. But sometimes I can't afford this amount. So, I either boil some water or I find some ways to get it […] Water is the most fundamental good, but water is not cheap – here we don't drink tap water as it's really bad. Fernanda, (46 mixed race, mother of 3).

The residents of San Carlos favelas in Rio de Janeiro, including participants like Fernanda from low-income households, are compelled to negotiate their own hydration strategies in response to the compounding effects of heat, inadequate water infrastructure, and limited purchasing power. Nevertheless, these strategies are frequently burdensome, requiring significant amounts of time and effort to obtain potable, chilled water from various locations across the city, and are largely inaccessible to those who are physically challenged by disabilities. Fernanda herself attested to having to walk for over half an hour in hot conditions and walk uphill to reach a source of free drinking water. This case shows the challenges faced by residents of San Carlos favelas and highlights the complex mesh of factors such as socio-economic status, physical ability, and infrastructural conditions in shaping the experiences of marginalised communities in urban settings.

In light of these interviews and findings, it is evident that the socio-economic and environmental contexts of Sao Carlos and Fallet have significant implications for the movement patterns and well-being of its residents. As such, a deeper understanding of the interplay between mobility poverty and cooling poverty can contribute to the understanding of place-based vulnerability and help effective strategies to address the concerns and needs of marginalised communities in urban settings.

5. Discussion

Recommendations like seeking refuge in green spaces, shopping centres or libraries to avoid direct sunlight seem feasible in various contexts. However, our research shows that residents of informal settlements (favelas) in Rio de Janeiro face significant barriers in accessing these options due to proximity and transportation costs. This finding corroborates what Del Rio frames in terms of mobility poverty among the slum-dwellers of Mexico City (Furszyfer, Dylan, and Sovacool Citation2023). We found evidence that mobility poverty is interlocked with systemic cooling poverty because it magnifies the obstacles to access cooling services such as reaching green/blue areas or the nearest cooling centre or hospital in case of heat stroke. A more nuanced and insidious effect of the lack of mobility infrastructure in general is that people, especially elderly and people with disabilities might find themselves “trapped” in their spaces, and if these spaces are too hot, crowded and not ventilated, they are overexposed to heat stress. This situation metaphorically recall the “sweatbox” – a torture device used predominantly on racialised people during slavery and racial segregation to manipulate the body's ability to mediate internal temperatures, as analysed by Starosielski (Citation2021). We are acutely aware that individuals inhabiting the favelas endure living conditions akin to being trapped in a figurative sweatbox, given their limited resources and options to regulate internal temperatures. This unfortunate circumstance arises from historical segregation policies (Pino Citation1997) that have led to inefficient infrastructures, disproportionately affecting communities of African descent, Indigenous peoples and migrants from impoverished regions like the Northeast. Consequently, these marginalised and racialised groups bear the brunt of what can be described as a form of invisible “heat torture”, perpetuating the cycle of socio-economic disparities.

Based on interviews with favela dwellers, the primary heat adaptation strategy used to avoid direct sunlight is staying indoors. However, the infrastructural characteristics of favela dwellings, such as metal roofs and unfinished materials, worsen indoor temperatures, subjecting individuals to oppressive heat even indoors. As a result, they often resort to hydropractices to cope with the high temperatures. Unfortunately, the water crisis in 2021 made even hydropractices potentially harmful due to the use of unsafe water. The data collected, using both quantitative and qualitative methods, revealed a significant lack of access to potable drinking water, with 96% of participants reporting no access. This alarming finding highlights the widespread use of contaminated water during the research period, exposing individuals to potential health risks and hazardous consequences. Furthermore, the pervasive absence of accessible public restroom facilities, coupled with social discrimination experienced by LGBTQI+ further diminishes the likelihood of adherence to the health recommendation. This finding links with the literature on gender, water and sanitation insecurity (see Srinivasan Citation2015), and points to the additional research that is needed in these areas.

Most of the active cooling technologies are limited to fans and refrigerators, with only five favelas’ residents owning and using an AC unit. Participants admitted that they could only use ACs because of electricity thefts, otherwise they would not be able to afford it. While the use of an AC can be seen as a maladaptation practice (Farbotko and Waitt Citation2011), for many people especially those with chronic health conditions, disabilities and mobility poverty it can be a lifesaving solution. This indicates the importance of energy affordability in the attainment of thermal safety as already highlighted in the growing literature on energy poverty (Mastrucci et al. Citation2022).

This paper also elucidates the importance of immaterial infrastructures of knowledge and heat maladaptation. For individuals residing in favelas, ensuring proper hydration poses significant challenges due to not only the unavailability of potable water but also the lack of awareness that some practices might be dehydrating instead. For example, we have seen how there is a prevalence of drinking alcohol and highly sugared soft drinks during hot weather among racialised favela residents. Such practices do not help the body to stay hydrated. We also found that eating habits reflect what is found in previous studies on urban food security. Low-income communities tend to eat less fruit and vegetables (Freedman and Bell Citation2009), further exacerbating the risks to heat stress. The preferences for highly processed drinks and food among low-income racialised communities has been seen as a form of oppression “through poor nutrition”(Freeman Citation2007). We find this is a useful framing in terms of appropriate hydration to fight heat stress, as food is often a neglected coping strategy in heat adaptation discourses.

Favelas’ dwellers with childcare and reproductive responsibility such as provision of nutrition and hydration (as in the case of Fernanda) are particularly challenged in avoiding physical strain during the hottest hours of the day. This finding is in line with the literature on gender and climate shocks for example – see Lee et al. (Citation2021). In their study in Tanzania, Lee et al. (Citation2021) found that heat stress significantly increases female family labour supply in female-only households, while it reduces male family labour in dual-adult households without affecting female family labour. This means that women perform their gendered tasks despite hot temperatures. Our study evidences that the lack of basic water and transportation infrastructure can act as a multiplier of disadvantages posing serious heat stress risks on people living in favelas. This because favelas’ dwellers tend to live uphill and lack financial means to use public and informal local transportation (such as motorbikes or minivans).

6. Conclusion

Given the rising temperatures, widespread health advisories endorsed by governments and international health organisations often assume universal access to essential cooling infrastructures across all regions of the world. This study highlights how marginalised groups have limited access to options that reduce the risks posed by heat stress. The behaviours adopted by the participants in the study reveal that favela dwellers, migrants, disabled people, racialised transgender and racialised single mothers lack access to green and blue spaces, as well as to options that entail social interactions, such as going to shopping malls. This feature tends to cumulate when these groups live in favelas, which tend to be characterised by lack of basic water, green spaces and transportation infrastructure.

The intersectionality analysis shows how racialised women with children often cannot avoid physical exertion during the hottest hours of the day because of their reproductive gendered role. Similarly, racialised transgender people with HIV-related disabilities suffer from harassment, which impede their quest for thermal comfort in public spaces. Racialised transgender people also face microaggressions and acts of violence in public spaces due to societal norms and prejudices that increase the likelihood of homelessness (Goldsmith, Raditz, and Méndez Citation2022). This has further implications for their thermal comfort. These experiences can lead to a sense of exclusion and vulnerability, impacting the way transgender individuals interact with and navigate through urban spaces. It is important to recognise how the power dynamics that shape these experiences of marginalisation and harassment can also build thermal injustices.

Additionally, the research emphasised the cumulative negative impacts of heat on individuals with mobility disabilities, both in terms of physical limitations to use cooling strategies (e.g. hydropractices) and the social and infrastructural barriers they encounter. People with physical disabilities may have distinct thermal needs due to various factors, including differences in mobility, posture, body size and shape, and effects on the body's thermoregulatory responses caused by the disability itself or medications used to manage it. Assistive devices such as wheelchairs may also impact thermal requirements due to the materials used in their construction.

We believe the integration of systemic cooling poverty and mobility poverty can provide useful tools to identify intersectional thermal rights inequalities. We underscore the importance of considering intersectional vulnerabilities and implementing inclusive policies as thermal justice to address the unique challenges faced by marginalised populations. For example, alongside enduring policies aiming to actively diminish racial, gender and class disparities, recommendations can include the implementation of short-term solutions such as zero-emission “cooling rescue vehicles”. These vehicles could be a community-based solution designed to transport individuals at risk of heat stress, particularly those trapped in their homes due to transportation challenges, potentially offering crucial healthcare assistance to vulnerable populations. Another valuable initiative might be the creation of a platform for public engagement to foster inclusive discussions and incorporate diverse perspectives and ideas regarding access to passive cooling solutions. An additional initiative could concentrate on rescuing and safeguarding lost traditional knowledge on passive cooling among communities, thereby restoring and achieving thermal autonomy.

Forthcoming research will benefit from efforts to examine further the decolonisation of thermal comfort and scrutinise how existing paradigms permeate individuals’ endeavours to seek passive and available cooling solutions. Creating more inclusive and safe public spaces for all communities, and particularly those who are marginalised, will help ensure equitable access to thermal comfort for all.

Acknowledgements

We are greatly indebted to all participants who shared their stories and contributed to the paper. We would like to express our gratitude to J. Crimi and G. Squarci for their support.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 This term is used to describe how the temperature feels to the human body, taking into account factors such as humidity, wind speed and other atmospheric conditions, in addition to the actual air temperature. It provides a more accurate representation of how the weather conditions are perceived by individuals, compared to just the measured air temperature.

2 The acronym LGBTQI+ stands for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer/Questioning and Intersex, with the "+" representing additional diverse sexual orientations, gender identities and expressions that may not be explicitly included in the initial acronym. The "+" symbolizes inclusivity and recognises the evolving nature of identities within the LGBTQI+ community.

3 We interpret the coefficients in Table 3 as associations and remain agnostic about their magnitude and statistical significance. The small sample size limits the statistical power of the regressions and constrains the analysis to consider few explanatory variables. We only looked at those strategies demonstrating sufficient heterogeneity among participants, namely ownership of air conditioning (AC), visiting green or blue areas, consumption of alcoholic beverages, and going to the beach.

References

- Amorim-Maia, Ana T, Isabelle Anguelovski, Eric Chu, and James Connolly. 2022. “Intersectional Climate Justice: A Conceptual Pathway for Bridging Adaptation Planning, Transformative Action, and Social Equity.” Urban Climate 41: 101053. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.uclim.2021.101053.

- Anthias, Floya. 2012. “Intersectional What? Social Divisions, Intersectionality and Levels of Analysis.” Ethnicities 13 (1): 3–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468796812463547.

- Bhambra, Gurminder K, and Peter Newell. 2022. “More than a Metaphor: ‘Climate Colonialism’in Perspective.” Global Social Challenges Journal 1 (aop): 1–9.

- Blundell, Amelia. 2020. ‘ Hey Architect, Ko Wai Hoki Koe?’ Decolonising Mainstream Placemaking in Aotearoa, New Zealand. Open Access Te Herenga Waka-Victoria University of Wellington.

- Boonruksa, Pongsit, Thatkhwan Maturachon, Pornpimol Kongtip, and Susan Woskie. 2020. “Heat Stress, Physiological Response, and Heat Related Symptoms among Thai Sugarcane Workers.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17 (17): 1–15. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17176363.

- Bosca, Hannah Della. 2023. “Comfort in Chaos: A Sensory Account of Climate Change Denial.” https://doi.org/10.1177/02637758231153399.

- Bouzarovski, Stefan, and Neil Simcock. 2017. “Spatializing Energy Justice.” Energy Policy, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2017.03.064.

- Brannen, Julia. 2005. “Mixing Methods: The Entry of Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches into the Research Process.” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 8 (3): 173–184.

- Chakraborty, Jayajit, Sara E Grineski, and Timothy W Collins. 2019. “Hurricane Harvey and People with Disabilities: Disproportionate Exposure to Flooding in Houston, Texas.” Social Science & Medicine 226: 176–181.

- Chang, Jiat Hwee. 2016. “Thermal Comfort and Climatic Design in the Tropics: An Historical Critique.” Journal of Architecture 21 (8): 1171–1202. https://doi.org/10.1080/13602365.2016.1255907.

- Coates, Lucinda, Jonathan van Leeuwen, Stuart Browning, Andrew Gissing, Jennifer Bratchell, and Ashley Avci. 2022. “Heatwave Fatalities in Australia, 2001–2018: An Analysis of Coronial Records.” International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 67: 102671. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2021.102671.

- Cole, Luke W, and Sheila R Foster. 2001. From the Ground up: Environmental Racism and the Rise of the Environmental Justice Movement. Vol. 34. NYU Press.

- Colucci, Alex R, Daniel J Vecellio, and Michael J Allen. 2021. “Thermal (In)Equity and Incarceration: A Necessary Nexus for Geographers.” Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space 6 (1): 638–657. https://doi.org/10.1177/25148486211063488.

- Colucci, Alex R, Daniel J Vecellio, and Michael J Allen. 2023. “Critical Physical Geographies of Air, Atmosphere, and Climate.” In Progress in Environmental Geography. London: SAGE Publications Sage UK.

- Crenshaw, Kimberle. 1989. “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics.” University of Chicago Legal Forum 139: 139–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/0011-9164(90)80039-E.

- Creswell, John W, and J. David Creswell. 2005. Mixed Methods Research: Developments, Debates, and Dilemma. Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

- Cutter, Susan L, Lindsey Barnes, Melissa Berry, Christopher Burton, Elijah Evans, Eric Tate, and Jennifer Webb. 2008. “A Place-Based Model for Understanding Community Resilience to Natural Disasters.” Global Environmental Change 18 (4): 598–606. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2008.07.013.

- Cutter, Susan L, Bryan J Boruff, and Lynn W Shirley. 2003. “Cutter. Socail Vulnerability.Pdf.” Social Science Quarterly.

- Ergas, Christina, Laura McKinney, and Shannon Elizabeth Bell. 2021a. “Intersectionality and the Environment BT.” In Handbook of Environmental Sociology, edited by Beth Schaefer Caniglia, Andrew Jorgenson, Stephanie A Malin, Lori Peek, David N Pellow, and Xiaorui Huang, 15–34. Cham: Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-77712-8_2.

- Ergas, Christina, Laura McKinney, and Shannon Elizabeth Bell. 2021b. “Intersectionality and the Environment.” In Handbook of Environmental Sociology, edited by Beth Schaefer Caniglia, Andrew Jorgenson, Stephanie A Malin, Lori Peek, David N Pellow, and Xiaorui Huang, 524. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-77712-8.

- Fanger, P. O. 1972. “Thermal Comfort: Analysis and Applications in Environmental Engineering.” Applied Ergonomics 3 (3): 181. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0003-6870(72)80074-7.

- Farbotko, Carol, and Gordon Waitt. 2011. “Residential Air-Conditioning and Climate Change: Voices of the Vulnerable.” Health Promotion Journal of Australia 4: 13–15.

- Freedman, Darcy A, and Bethany A Bell. 2009. “Access to Healthful Foods among an Urban Food Insecure Population: Perceptions versus Reality.” Journal of Urban Health 86 (6): 825–838. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-009-9408-x.

- Freeman, Andrea. 2007. “Fast Food: Oppression through Poor Nutrition.” California Law Review 95: 2221.

- Furszyfer, Del Rio, D. Dylan, and Benjamin K Sovacool. 2023. “Of Cooks, Crooks and Slum-Dwellers: Exploring the Lived Experience of Energy and Mobility Poverty in Mexico’s Informal Settlements.” World Development 161: 106093. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2022.106093.

- Ghosh, Sasanka, and Arijit Das. 2018. “Modelling Urban Cooling Island Impact of Green Space and Water Bodies on Surface Urban Heat Island in a Continuously Developing Urban Area.” Modeling Earth Systems and Environment 4 (2): 501–515. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40808-018-0456-7.

- Goldsmith, Leo, Vanessa Raditz, and Michael Méndez. 2022. “Queer and Present Danger: Understanding the Disparate Impacts of Disasters on LGBTQ+ Communities.” Disasters 46 (4): 946–973. https://doi.org/10.1111/disa.12509.

- He, Bao Jie, Dongxue Zhao, Ke Xiong, Jinda Qi, Giulia Ulpiani, Gloria Pignatta, Deo Prasad, and Phillip Jones. 2021. “A Framework for Addressing Urban Heat Challenges and Associated Adaptive Behavior by the Public and the Issue of Willingness to Pay for Heat Resilient Infrastructure in Chongqing, China.” Sustainable Cities and Society 75 (May). 103361https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2021.103361.

- Hobart, Hi’ilei Julia Kawehipuaakahaopulani. 2023. Cooling the Tropics: Ice, Indigeneity, and Hawaiian Refreshment. Duke University Press.

- IBGE. 2010. Censo Demográfico 2010. Características Da População e Dos Domicílios. Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística.

- IBGE. 2022. “Preliminary Population of Municipalities Based on 2022 Population Census Data Collected up to December 25, 2022.”

- Instituto Nacional de Metereologia. 2023. "Instituto Nacional de Metereologia.” https://tempo.inmet.gov.br/ValoresExtremos/TMAX.

- IPCC. 2022. “Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability.”

- Jamei, Elmira, Priyadarsini Rajagopalan, Mohammadmehdi Seyedmahmoudian, and Yashar Jamei. 2016. “Review on the Impact of Urban Geometry and Pedestrian Level Greening on Outdoor Thermal Comfort.” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 54: 1002–1017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2015.10.104.

- Kake, Jade. 2020. “Spatial Justice—Decolonising Our Cities and Settlements.” Counterfutures 9: 123–135.

- Kammuang-Lue, Niti, Phrut Sakulchangsatjatai, Pisut Sangnum, and Pradit Terdtoon. 2015. “Influences of Population, Building, and Traffic Densities on Urban Heat Island Intensity in Chiang Mai City, Thailand.” Thermal Science 19 (suppl. 2): 445–455.

- Khosla, Radhika, Renaldi Renaldi, Antonella Mazzone, Caitlin McElroy, and Giovani Palafox-Alcantar. 2022. “Sustainable Cooling in a Warming World: Technologies, Cultures, and Circularity.” Annual Review of Environment and Resources 47 (1): 449–478. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-environ-120420-085027.

- Klinenberg, Eric. 2002. Heat Wave: A Social Autopsy of Disaster Chicago, Vol. 1. Hilos Tensados.

- Klinenberg, Eric, Malcolm Araos, and Liz Koslov. 2020. “Sociology and the Climate Crisis.” Annual Review of Sociology 46: 649–669. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-121919-054750.

- Kuttler, Tobias, and Massimo Moraglio. 2021. Re-Thinking Mobility Poverty: Understanding Users’ Geographies, Backgrounds and Aptitudes. Taylor & Francis.

- Langenheim, Nano, Marcus White, Nigel Tapper, Stephen J Livesley, and Diego Ramirez-Lovering. 2020. “Right Tree, Right Place, Right Time: A Visual-Functional Design Approach to Select and Place Trees for Optimal Shade Benefit to Commuting Pedestrians.” Sustainable Cities and Society 52: 101816. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2019.101816.

- Larson, Nicole I, Mary T Story, and Melissa C Nelson. 2009. “Neighborhood Environments: Disparities in Access to Healthy Foods in the U.S.” American Journal of Preventive Medicine 36 (1): 74–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2008.09.025.

- Lee, Yeyoung, Beliyou Haile, Greg Seymour, and Carlo Azzarri. 2021. “The Heat Never Bothered Me Anyway: Gender-Specific Response of Agricultural Labor to Climatic Shocks in Tanzania.” Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy 43 (2): 732–749. https://doi.org/10.1002/aepp.13153.

- Li, Dawei, Jiacan Yuan, and Robert E Kopp. 2020. “Escalating Global Exposure to Compound Heat-Humidity Extremes with Warming Environmental Research Letters with Warming.” Environmental Research Letters 15: 64003. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ab7d04.

- Loo, Yat Ming. 2017. “Towards a Decolonisation of Architecture.” The Journal of Architecture 22 (4): 631–638.

- Lowans, Christopher, Dylan Furszyfer Del Rio, Benjamin K Sovacool, David Rooney, and Aoife M Foley. 2021. “What Is the State of the Art in Energy and Transport Poverty Metrics? A Critical and Comprehensive Review.” Energy Economics 101: 105360. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2021.105360.

- Mastrucci, Alessio, Edward Byers, Shonali Pachauri, Narasimha Rao, and Bas van Ruijven. 2022. “Cooling Access and Energy Requirements for Adaptation to Heat Stress in Megacities.” Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change 27 (8): 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11027-022-10032-7.

- Mazzone, A., E. De Cian, G. Falchetta, A. Jani, M. Mistry, and R. Khosla. 2023. Understanding systemic cooling poverty. Nature Sustainability 6: 1533–1541. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-023-01221-6

- Mazzone, Antonella, and Radhika Khosla. 2021. “Socially Constructed or Physiologically Informed? Placing Humans at the Core of Understanding Cooling Needs.” Energy Research and Social Science 77: 102088. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2021.102088.

- McIntosh, Michele J., and Janice M Morse. 2015. “Situating and Constructing Diversity in Semi-Structured Interviews.” Global Qualitative Nursing Research 2), https://doi.org/10.1177/2333393615597674.

- Mercer, Harriet, and Thomas Simpson. 2023. “Imperialism, Colonialism, and Climate Change Science.” In Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change, e851. Wiley Online Library.

- Mikulewicz, Michael, Martina Angela Caretta, Farhana Sultana, and Neil J. W. Crawford. 2023. “Intersectionality & Climate Justice: A Call for Synergy in Climate Change Scholarship.” Environmental Politics, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2023.2172869.

- Mitchell, C. Bruce, and Jayajit Chakraborty. 2019. “Thermal Inequity.” In Routledge Handbook of Climate Justice, 1st ed., edited by Tahseen Jafry, 567. Earthscan.

- Muzorewa, Terence T, Vongai Z Nyawo, and Mark Nyandoro. 2018. “Decolonising Urban Space: Observations from History in Urban Planning in Ruwa Town, Zimbabwe, 1986-2015.” New Contree 81: 24.

- Panchang, Sarita Vijay, Pratima Joshi, and Smita Kale. 2022. “Women ‘Holding It’in Urban India: Toilet Avoidance as an under-Recognized Health Outcome of Sanitation Insecurity.” Global Public Health 17 (4): 587–600.

- Peres, Leonardo de Faria, Andrews José de Lucena, Otto Corrêa Rotunno Filho, and José Ricardo de Almeida França. 2018. “The Urban Heat Island in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, in the Last 30 Years Using Remote Sensing Data.” International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 64: 104–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jag.2017.08.012.

- Pino, Julio Cesar. 1997. “History of Favelas in Rio de Janeiro Author.” Latin American Research Review 32 (3): 111–122.

- Rodriguez, Beatriz. 2021. Extreme Heat Further Complicates the Lives of Homeless Women and LGBTQ People. PBS NewsHour.

- Salata, Ferdinando, Iacopo Golasi, Davide Petitti, Emanuele de Lieto Vollaro, Massimo Coppi, and Andrea de Lieto Vollaro. 2017. “Relating Microclimate, Human Thermal Comfort and Health during Heat Waves: An Analysis of Heat Island Mitigation Strategies through a Case Study in an Urban Outdoor Environment.” Sustainable Cities and Society, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2017.01.006.

- Samuel, D., G. Leo, S. M. Shiva Nagendra, and M. P. Maiya. 2013. “Passive Alternatives to Mechanical Air Conditioning of Building: A review.” Building and Environment, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2013.04.016.

- Santamouris, M. 2014. “Cooling the Cities - A Review of Reflective and Green Roof Mitigation Technologies to Fight Heat Island and Improve Comfort in Urban Environments.” Solar Energy 103: 682–703. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solener.2012.07.003.

- Schlosberg, David. 1999. Environmental Justice and the New Pluralism: The Challenge of Difference for Environmentalism. OUP Oxford.

- Shove, Elizabeth, Gordon Walker, and Sam Brown. 2014. “Transnational Transitions: The Diffusion and Integration of Mechanical Cooling.” Urban Studies 51 (7): 1506–1519. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098013500084.

- Sirayi, Mziwoxolo, and Devin Beauregard. 2021. “3 Colonial, Cultural Planning, and Decolonisation of South African Urban Space.” In Culture and Rural–Urban Revitalisation in South Africa: Indigenous Knowledge, Policies, and Planning, 35–53. Routledge.

- Soja, Edward W. 2013. Seeking Spatial Justice. Vol. 16. University of Minnesota Press.

- Srinivasan, Raji. 2015. “Lack of Toilets and Violence against Indian Women: Empirical Evidence and Policy Implications.” Available at SSRN 2612052.

- Starosielski, Nicole. 2021. Media Hot and Cold. Duke University Press.

- Sultana, Farhana. 2022. “The Unbearable Heaviness of Climate Coloniality.” Political Geography 99: 102638.

- Tawsif, Shehan, Md. Shafiul Alam, and Abdullah Al-Maruf. 2022. “How Households Adapt to Heat Wave for Livable Habitat? A Case of Medium-Sized City in Bangladesh.” Current Research in Environmental Sustainability 4: 100159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crsust.2022.100159.

- Teddy, Charles, and Fen Yu. 2007. “Mixed Methods Sampling: A Typology With Examples.” Journal of Mixed Methods Research 21 (77): 25. https://doi.org/10.1177/2345678906292430.

- Triyuly, Wienty, Sugeng Triyadi, and Surjamanto Wonorahardjo. 2021. “Synergising the Thermal Behaviour of Water Bodies within Thermal Environment of Wetland Settlements.” International Journal of Energy and Environmental Engineering 12 (1): 55–68. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40095-020-00355-z.

- Turek-Hankins, Lynée L, Erin Coughlan de Perez, Giulia Scarpa, Raquel Ruiz-Diaz, Patricia Nayna Schwerdtle, Elphin Tom Joe, Eranga K Galappaththi, et al. 2021. “Climate Change Adaptation to Extreme Heat: A Global Systematic Review of Implemented Action.” Oxford Open Climate Change 1 (1). https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfclm/kgab005.

- UKHSA. 2023. “Beat the Heat: Staying Safe in Hot Weather.” https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/beat-the-heat-hot-weather-advice/beat-the-heat-staying-safe-in-hot-weather.

- United Nations Environment, and Programme. 2021. “Beating the Heat.”.

- Vecellio, Daniel J, S. Tony Wolf, Rachel M Cottle, and W. Larry Kenney. 2022. “Evaluating the 35°C Wet-Bulb Temperature Adaptability Threshold for Young, Healthy Subjects (PSU HEAT Project).” Journal of Applied Physiology (Bethesda, Md.: 1985) 132 (2): 340–345. https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.00738.2021.

- Walker, Gordon. 2020. “Environmental Justice.” In International Encyclopedia of Human Geography (Second Edition), 221–225. Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.5840/wcp20-paideia199822401.

- Watts, Nick, Markus Amann, Nigel Arnell, Sonja Ayeb-Karlsson, Jessica Beagley, Kristine Belesova, Maxwell Boykoff, et al. 2021. “The 2020 Report of the Lancet Countdown on Health and Climate Change: Responding to Converging Crises.” The Lancet 397 (10269): 129–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32290-X.

- Wen, Yuangao, and Zhiwei Lian. 2009. “Influence of Air Conditioners Utilization on Urban Thermal Environment.” Applied Thermal Engineering 29 (4): 670–675. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2008.03.039.

- WHO. 2023. “Heatwaves.” Heatwaves. https://www.who.int/health-topics/heatwaves#tab=tab_1.

- Yenneti, Komali, Rosie Day, and Oleg Golubchikov. 2016. “Spatial Justice and the Land Politics of Renewables: Dispossessing Vulnerable Communities through Solar Energy Mega-Projects.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 76: 90–99.