ABSTRACT

This article examines the challenges faced by Acervo Bajubá, an LGBT+ community archive located in São Paulo, Brazil. Departing from the observation of a disconnect between the recognition of the archive’s importance in terms of the content it holds and its consideration as a community epistemological project, the article argues for a paradigm shift in understanding archives. Contrariwise, the article proposes viewing Acervo Bajubá as an epistemological project that challenges conventional notions of community, history, and memory. It calls for a re-evaluation of the archive’s material conditions, bringing them to the forefront, and operating a recognition of its role as a legitimate knowledge producer – and not only as a repository for disciplinary projects and commitments. The article suggests that by expanding the concept of the archive-as-object and embracing archive-as-community-practice, alternative relationships with the past can be forged. Finally, through the analysis of two art-pieces produced in the context of an inventory process, the article argues for a concept and practice of archive that challenges disembodied notions of history, memory, and community, emphasising community practice and recognising the lives and bodies embedded within archival devices. It concludes by highlighting the importance of grounding the archive in the present time, and fostering creative tactics for envisioning alternative historical imaginaries and political repertoires.

Cet article examine les défis auxquels se confronte Acervo Bajubá, une archive communautaire LGBT+ située à São Paulo, au Brésil. Avec comme point de départ l'observation d'une fracture entre la reconnaissance de l'importance de l'archive sur le plan du contenu qu'elle héberge et sa considération comme un projet épistémologique communautaire, cet article présente des arguments en faveur d'un changement de paradigme autour de la compréhension des archives. Cet article propose qu'Acervo Bajubá soit au contraire vue comme un projet épistémologique qui met en question les notions conventionnelles de communauté, d'histoire et de mémoire. Il appelle à une réévaluation des conditions matérielles de l'archive, pour les mettre en avant, et recommande qu'il soit procédé à une reconnaissance de son rôle comme producteur légitime de connaissances – et pas seulement comme dépôt de projets et d'engagements. L'article suggère qu'en élargissant le concept de l'archive en tant qu'objet et en adoptant le concept d'archive comme pratique communautaire, il est possible d'établir des relations alternatives avec le passé. Enfin, à travers l'analyse de deux œuvres d'art produites dans le contexte d'un processus d'inventaire, l'article préconise un concept et une pratique de l'archive qui met en question les notions désincarnées d'histoire, de mémoire et de communauté, en mettant en relief la pratique communautaire et en reconnaissant les vies et les corps ancrés dans les dispositifs archivistiques. Il conclut en soulignant à quel point il est important d'ancrer l'archive dans le présent, et d'encourager des tactiques créatives pour concevoir des imaginaires historiques et des répertoires politiques alternatifs.

Este artículo examina los retos enfrentados por el Acervo Bajubá, un archivo de la comunidad LGBT+ con sede en São Paulo, Brasil. Tras constatar la desconexión entre el reconocimiento de la importancia de este archivo en términos del contenido que alberga y su consideración como proyecto epistemológico comunitario, el presente artículo aboga por un cambio de paradigma en la comprensión de archivos. Así, contraponiéndose a esta desconexión, este trabajo propone que el Acervo Bajubá sea considerado como un proyecto epistemológico que impugna las nociones convencionales de comunidad, historia y memoria. Al mismo tiempo, hace un llamado a reevaluar las condiciones materiales del archivo, colocándolas en un primer plano, y a materializar el reconocimiento de su papel como productor legítimo de conocimiento y no sólo como depósito de proyectos y compromisos disciplinarios. Ampliando el concepto de archivo-como-objeto y adoptando el de archivo-como-práctica-comunitaria, el artículo sugiere que pueden establecerse relaciones alternativas con el pasado. Por último, mediante el análisis de dos obras de arte producidas en el contexto de un proceso de inventario, el artículo intercede por un concepto y una práctica en torno al archivo que cuestione las nociones incorpóreas de historia, memoria y comunidad, haciendo hincapié en la práctica comunitaria e identificando las vidas y los cuerpos contenidos en los dispositivos archivísticos. Finalmente, se destaca la importancia de fundamentar el archivo en el tiempo presente y de fomentar prácticas creativas para idear imaginarios históricos y repertorios políticos alternativos.

Script 1. The academic researcher contacts the archive

On a Friday morning, in the midst of 2021, with the flexibilities of COVID-19 policies in Brazil, the script was enacted for the first time – although we did not know back then how we would repeatedly live it in the next months. A researcher, usually self-identified as a gay man or a lesbian woman, would email us briefly, explain their research topic and persuasively elaborate how they realised, while searching for sources in Google, that our archive holds an important copy of a certain item which would be really important for their research and, implicitly or explicitly, to the Brazilian LGBT+ community. After confirming a visit date, the researcher comes and visit us.

Script 2. The academic researcher goes to the archive

When aware of a particular item, the general plot leads to a quick and quiet visit to scan the item with a cellphone, through the use of apps like CamScanner, as we do not have digitisers. Most of the times, the piece will be cited, but no mention of the volunteer who hosted them or the archive itself will be made – and we will get to know about the work in the near future when a book or a thesis is published. And maybe another researcher will write again, asking for the same item. When there is no particular object to be found, the visit feels awkward: we give a quick tour around the archive, teach some of the rules for manipulating the objects, and mention the lack of an inventory (and ask for help in this process). The researcher usually stays less than an hour and leaves. The invitations for cataloging and inventory processes are rarely accepted.

Introduction

I begin this article with these two vignettes neither to demonise academic researchers (actually I am also one) nor to criticise institutionalised archives that centre preservation goals and target academic researchers rather than community-building activations and practices.Footnote1 What actually motivates these performative and somehow theatrical lines is a desire for communicating other practices of archive and scaling-upFootnote2 some of the nuisance experienced in the managing of the everyday of Acervo Bajubá.Footnote3 Located in São Paulo, Brazil, and founded in the early 2010s, Acervo Bajubá is an LGBT+Footnote4 community-oriented project holding more than 4,000 items that register dissident sexualities and gender identities and expressions in Brazil, from the 19th century to the present. Acervo Bajubá collaborates with exhibitions, qualification programmes, and several projects that produce, mediate, and circulate narratives about the histories and memories of the LGBT+ communities.

If we can read in the scripts a general perception of Acervo Bajubá as a legitimate institution in terms of the items it holds, it is also easy to notice how this recognition does not necessarily lead to an acknowledgment of the precariousness that shapes its real conditions – an imbalance that certainly motivates the inherent sarcasm of these scripts. And, to be fair to academic researchers, I am quite sure that the precarious conditions might not be even fully known by them. Notwithstanding, it is also hard to deny the visceral reactions one feels when reading this sort of email after several hours of hard work, such as transporting boxes or writing endless grant applications after one’s first or even second job’s work hours. In short, these strong reactions usually stem from the tension between academic intentions and their performative connections to the ‘LGBT+ community’, as well and their contradictions when interpreted from the everyday of an embodied LGBT+ community project that struggles to find participants and economic resources.

But the scripts also illustrate the misrecognition or disregard of Acervo Bajubá’s role as a legitimate knowledge producer in the present, including our own archival methods and concepts. If there is a recognition of our position as ‘archivists’, in the sense of that ‘house arrest’ through which an archive is made (Derrida and Prenowitz Citation1995, 10), it also becomes clear that power has always been inaugurated somewhere else, as insightfully provoked by Carolyn Steedman (Citation2002, 44), and hence we may be limited only to our guarding or hermeneutic functions.Footnote5

In simple words, it seems that Acervo Bajubá is legitimate to assemble important items to the ‘LGBT+ community’ (whatever that term may mean), and provide resources for the oftentimes demanded ‘memory’ (by notions such as memory-duty or ‘decolonial histories’), but not necessarily legitimate enough to create the items to be housed, nor to be considered as an epistemological and political project. In a nutshell, the scripts depict that our archive can hold important objects for academic researchers, but that does not lead to the recognition of our material conditions, nor to what we do as a community archive, rendering our labour as an invisible object of study, as we rarely ever receive emails interested in what or how we do, the invisible enabling conditions of any research visit.

However, what if we refuse disciplinary epistemologies and commitments to disciplinary projects and expand our vision to Acervo Bajubá beyond its content, looking at its ways of producing, circulating, and activating LGBT+ documents and narratives, as practices of an epistemology that may, in fact, underpin other affective attachments to archive and history? From a material point of view, what if we bring this invisibilised labour to the forefront as an actual episteme, centred in ‘a gesture of recognition and care, elaborated on listening, on affection’ (Fraccaroli Citation2023, 21) that may provide other relations to the past, beyond History and the search for ‘evidence’?Footnote6

The main intervention of the present article, in the mark of a special issue on ‘Decolonising Knowledge and Practice’, is to disrupt the monopoly of the paradigm of archive-as-repository for academic researchers, and, rather, proposing the study of Acervo Bajubá as an epistemological project, in which subsumed notions of community and memory are not taken for granted, but are centrally called into discussion as a first ethical and methodological premise. In such a frame, ‘the dematerialised aspect of what can happen’ (Green Citation2014, 275) in the domiciliation processes that constitute an archive are considered rather a risk than a positive effect per se.Footnote7 Indeed, being aware of this dematerialised aspect, we become concerned about how archives actually oftentimes make forgetting more possible than preserving (Green Citation2014, 276), and then we might even consider to take the risk of envisioning other possible relationships with the past in which ‘memory functions as an active process allowing continued reconsideration rather than a form of entombment to which archives are sometimes compared’ (Green Citation2014, 275, 281).

For Anjali Arondekar (Citation2005, 11), even with the rethinking of colonial methodologies and conceptions of the coloniality of the archive, there is still an assumption of a ‘telos of knowledge production still deemed approachable through what one finds’ when working with archives. Commenting on Arondekar’s discussions, Renisa Mawani (Citation2012, 347) explains the idea of archive as a ‘recalcitrant event’, in which this device (the archive) not only implies a problem of reading or interpretation, but also requires it as the pre-exigency of the archive itself (a supplementary relation). In that sense, for Mawani (Citation2012, 347), Arondekar proposes an approach to the archive as an ‘aporia’, in which the goal of the historical labour is ‘an unrepresentable search for an impossible object’.

Acknowledging the aforementioned ‘continued reconsideration’, this article is based on a community practice that shows that the archive can be something else if we walk away from the theatre of history (Taneja Citation2017), and perhaps work closely to a performance of the decolonial notion Arjun Appadurai proposes, which conceives the archive as a result of a collective effort, an anticipation of a collective memory, considering documents as interventions: ‘[A] collective will to remember’ (Appadurai Citation2003, 17). In that comprehension, beyond different ways of reading the archive, e.g. against or along the grain (Stoler Citation2009), I am more interested in expanding this conception of archive-as-object, as proposed by many artists and activists (de Jonge Citation2016, 7), towards a recognition of archive-as-community-practice. Such recognition entails looking at how the alliance of different bodies in the present space and time can shift the consigning authority of the transcendental Western archivist and embrace an ‘unrepresentability’, not only in terms of a search for an impossible object, but also reckoning an impossible subject or conception of community that motivates it. This position may open the archive to other experiences, cosmologies and enchantments, usually rendered invisible by the colonial epistemological framework of History, in an act of ‘a deep sense of accountability’ in which, instead of considering the archive itself as a challenge, we provincialise History, wondering if ‘the archive will submit to our engagements in the first place’ (Lewis Citation2014, 28).Footnote8

This article’s core contention is that, when queer bodies inhabit as archivists, the ‘utopian horizon’ and the ‘lived reality’ that constitutes an archive (Arondekar et al. Citation2015, 219) are fused as the dialogues that happen in this lived and concrete practice anticipate a need for a more serious consideration of any naïve or self-evident conception of LGBT+ community or subject to be searched in the archive. Thus, a notion of subject and community has to be performed firstly at the present time, evincing the impossibility of a taken-for-grant subject or community throughout time, either in the past or the present. In other words, different than academic research efforts, which are most of the times individual enterprises, engaging with the archive as a collective requires dialogues and coalitions. A community that is (per)formed in the present and then recognises the need for a constant call to other voices and bodies, particularly in the context of Brazil, a country shaped by several internal differences, wherein big historical narratives are a few times reliableFootnote9 becomes important. By assuming this impossibility and thus ‘queering the archivist’, a disembodied discussion on archival notions is rejected. In this approach, temporary and plural archivists emerge through temporary alliances, leading to diverse archive interpretations and expand the notions of what is considered as a document. New items can be found, produced and added, as the notion of document and its possible activations are expanded, and consequently a search based on an evidence paradigm or discipline’s primacy is materially decentred to a community-oriented political archival impulses and ethics.

From the intersections of the precarious material conditions and our political-epistemological commitments, this article echoes Terry Cook’s (Citation2013, 115) acknowledgment of the need to stop seeing community archiving as something ‘amateur and of limited value to the broader society’, and recognise it as an experience from which professional archivists and historians can learn much.Footnote10

In that frame, I aim to think about our embodied experiences within academic terms; that is to say, this writing is based on the impossible attempt of translating a lived practice into a theoretical essay, being shaped by dialogues with academic readings on queer archives of the ‘global North’, thereby producing and adding to that archival corpus.Footnote11 But, by so doing, I do not seek to undermine our practices to that corpus of knowledge or imply any kind of hierarchy between them. As a translation, aware of its limits, I intend to facilitate the communication of our embodied practice to a broader academic audience, hoping that academic researchers engage the other way around: embodying some of our concepts and experiencing other languages, practices and affective attachments to the archive, recognising the ‘archival desires’ that flicker in the handling of any document, from the inscription to the reading (Tortorici Citation2018, 18).

As a genre for this short discussion, this article endorses Clare Hemming’s claim that ‘stories matter’, and through the craft of a historical narrative of Acervo Bajubá, two different paradigms can emerge to the reader, and the shift to our current (and perhaps temporary) idea of archive can be comprehended.Footnote12 Although aware of the implicit progress narrative that may result from this narrative choice, this piece also seeks to be an empathetic and reparative reading (Hemmings Citation2011), conceiving that distinctions between these two moments/paradigms may be not that clear, and gesturing towards a narrative of an archive in which different stories, methods, and comprehensions are possible and can even coexist. This narrative is built in the first section, and in the second section I focus on the main aspects that this article seeks to work with, that of queering the archivist aspects of our project and its effects on a notion of community in this intertemporal encounter.

As a final methodological observation, in the process of feminist and decolonial writing, the separation of subject/object is refused (Kang Citation2009; Bisaillon et al. Citation2020). Thus, I seek to account my positionality as a central part of the method this writing performs, embracing Andrea Lira, Ana Luisa Muñoz-García, and Elisa Loncon’s (Citation2019, 476) arguments of how positionalities and identities must be reflected prior to raising research questions and projects. In that frame, I recognise that my involvement with Acervo Bajubá started through an invitation to participate in a podcast project, motivated by the circulation of previous works in which I discussed the limits of the mainstream LGBT+ historical and historiographic episteme in Brazil.Footnote13 I also recognise that although being a first-generation, queer, non-white, and non-binary researcher from the global South, the relative economic privilege I had must be highlighted, as it made it possible for me to access Brazilian public high education (despite my lack of cultural and symbolic capital).

Beyond my memories and previous work, this piece is a process of a writing strongly influenced by Black epistemologies as well, in particular referring to the aforementioned foreclosed invisible labour that materially makes the access to any archive possible.Footnote14 Bringing to the forefront the work that makes Acervo Bajubá’s collection a possible source to academic researchers, I want to highlight how the lived ‘backstage’ of any archive must be considered, and hence suggest how, although concerned with the content of ‘colonial archives’, the disposition and the conditions that enable the access to these archives may reproduce the coloniality that many researchers seek to undermine through their work.

As a memory work, I do not want to extend my views to other participants and acknowledge that any mistake, perspective’s conflict, or forgetting are only mine. However, any possible knowledge or inspiration that this article may motivate emerges from a community practice which should be credited.

(Auto)fictions: producing an archive identity and history

In ‘Constituting an archive’, Stuart Hall (Citation2001, 89) observes that ‘no archive arises out of thin air’, acknowledging the ‘prior conditions of existence’ of each archive and the tribute we need to pay to those involved in collecting items. Implicitly conceiving an idea of temporality (‘prior conditions’), he establishes a second moment, subsequent to this pre-existence: the moment of ‘constituting an archive’. Outlined as a radical shift, this moment occurs when a random collection becomes ‘something more ordered and considered: an object of reflection and debate’ (Hall Citation2001, 89), a moment of ‘the end of a certain kind of creative innocence, and the beginning of a new stage of self-consciousness, of self-reflexivity in an artistic movement’.

The reason for starting this section with this fragment is informed by the many parallels we can trace between it and Acervo Bajubá’s history, either regarding its ‘origins’ and a recent reorientation promoted by changes on the archive’s administration, and to a broader sociopolitical context in Latin America as well (Simonetto and Butierrez Citation2022). It was a pivotal moment when the collection's previously taken-for-granted meaning was called into question and we truly started to think of our internal practices, our implicit notions of document, history and memory, and the way we communicate them.

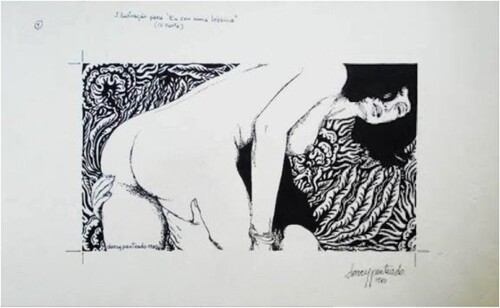

Still in Hall’s temporal frame, our ‘prior conditions of existence’ rely on Remom Bortolozzi’s relentless efforts of collecting items related to the LGBT+ communities throughout his years as a graduate student.Footnote15 The first activities date back to 2010, when a group of interested academic researchers and social activists gathered to discuss the LGBT+ history and memories in Brazil. For Bortolozzi,Footnote16 it was in 2012 when there was a fuse moment for the conception and implementation of Acervo Bajubá in a more formal sense as a more systematic collection of LGBT+ items. In that year, Bortolozzi found a Nanjing canvas of a lesbian oral sex scene, in really precarious conditions. On the top of it, it was possible to read ‘I. Ilustração para eu sou uma lésbica’ (in English: Illustration for I am a lesbian) and a signature on the bottom of it: Darcy Penteado (). These two fragments informed Bajubá’s first activities.

Based on research activities, this initial group got to know that ‘Eu sou uma lésbica’ referred to a feuilleton published at Status magazine, written by Cassandra Rios, a lesbian best-seller writer who was censored during the Brazilian civil–military dictatorship (1964–1985) (Morais Citation2023). The found Nanjing would later be included in one of the many books published by Rios, the first Brazilian woman author to sell more than 1 million copies. In that regard, Acervo Bajubá in the next subsequent years put countless efforts into collecting all of the works of Rios. Concerning Penteado, Bortolozzi acknowledges that before some exhibitions and memory works about him by the Museu da Diversidade de São Paulo around 2010, this pioneer of the gay movement in Brazil, plastic artist, and writer was not even remembered. Therefore, the piece brought two important figures to LGBT+ histories and memories in Brazil and served as a metaphor to think about the constant danger that these fragments of history are exposed to; in that scene, using Bortolozzi’s words, ‘exposed to mould’ and threatened by the ‘forgetting’.

Looking at this previous moment is not only important to pay tribute to Bortolozzi and other previous involved members, but also to recognise some of the implicit logics that shaped this collection and the ways it was first conceived. On the one hand, we can see a deep personal and affective involvement of academics and interested individuals on LGBT+ memories. On the other, it is also possible to perceive the concern with memories and histories through a cultural material perspective and, as Bortolozzi’s words resonate, somehow a duty of memory in those processes marked by the goal of ‘rescuing’ or ‘collecting’ objects and pieces.

In fact, in that first moment, Remom Bortolozzi and Felipe Areda (2017) described Acervo Bajubá not as an archive, but as a ‘collection’, refusing the consigning and patriarchal power of the archive, and alternatively deploying Walter Benjamin’s conception of ‘an infant collection’. This ‘infant collection’ would be open to an endless search for new objects that, once incorporated, could even change categorisations and the own meaning of the collection, a gesture that the authors claimed as a necessary step for a democratisation process of the LGBT+ memory in Brazil and an enabling condition for crafting a concept of LGBT+ culture. In order to do that, these two founding members gestured towards: (1) the need of a radical political subjective constitution by the enunciation of the ‘plural I’s’, as proposed by Brazilian lesbian poet Leila Míccolis, to think of the politicisation of personal experiences that permitted a constitution of a political, poetic, and moving plural ‘I’ in the mark of the beginning of the LGBT+ movement in Brazil; and (2) by the recognition of the rags that may constitute this fragmented memory, as they said to have learnt through the articulation of Benjamin’s conception of history as battling (and the idea of monument as barbarism), together with the artwork of José Leonilson:

Benjamin’s lesson was taught to us by works by Leonilson [Fortaleza, 1957–1993]. The plastic artist from Ceará – in the midst of the epidemic AIDS and the social panic that transformed our bodies, desires and loves in the very disease – knew how to contaminate life with his art, with a poetic production that inscribed from fragments, debris, ruins. Embroidering on pieces of sheets or painting with drops of blood, Leonilson allegorizes the effort to build a memory and a Brazilian LGBT culture like a writing from perdition. João Silvério Trevisan, commenting Leonilson's artwork, summarized: ‘Our rag, our art.’ (Bortolozzi and Areda Citation2017, 158)

First, the new participants would refer to it as an archive and not as a collection, perhaps as an effect of what they first felt when dealing with Acervo Bajubá: the collection was already composed, with implicit logics and categories to be understood. In that frame, despite the non-patriarchal theoretical assumptions and the open orientations that firstly constituted the collection, the participants found themselves in front of a stabilised and fixated corpus that could be read as something itself. And, from this position, they easily realised that, despite the original intentions, the ‘infant collector’ had always had values that oriented the choices they made.

When cleaning or getting to know the collection, the assembling orientations that constituted this archive were clear to the new and still external participants, who realised that more than half the records were related to dissident masculine sexualities, and that nearly all the collection was produced in the south-east region of Brazil, namely in Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo, many of them written by white south-east based scholars and intellectuals of the gay liberation fronts. This was even more quickly noticeable by the participants that joined the virtual activities that Acervo Bajubá had started to develop as an effect of the COVID-19 pandemic. In that context, the possibilities of accessing the archive were restricted, which led to a first concern about how to keep the archive alive during the pandemic. Notwithstanding, with the migration to virtual activities, the conditions of participation were expanded, and then people who lived in other regions of Brazil, in particular the north-east, could participate and bring their memories and perspectives to Acervo Bajubá.

Paradoxically, the many restrictions of access surprisingly led to other possibilities of access, a moment that made some of the members think about their own idea of access. In such a scene, if the initial gesture of Acervo Bajubá was certainly enacted by a desire for a different world-building, what the new participants found out was that this transcendental infant collector needed to be rendered as an embodied subject in terms of gender, race, social class, educational background, and geographical position, and consequently consider these as factors that indeed shape the world the collector inhabits and the possible objects they may gather.

This context of transition was marked by the recognition of how important some items indeed were, such as the aforementioned Nanjing, and the need to preserve them, but also how necessary it would be to critically consider the limits of these items in terms of ‘representation’, a clear-cut reminder of the dangers involved in claiming any project or idea of a Brazilian LGBT+ culture or community. It was at this moment, thinking from the differences that constituted these new ‘plural I’ of Acervo Bajubá, that we moved from the idea of LGBT+ community to the plural: LGBT+ communities. If thinking in terms of unit only between us demanded many dialogues and translations, how would it be possible to claim a single idea of community and culture?

This recognition was also a reminder of how the same document could be read in plural ways from different perspectives and positionalities, leading to the need to expand Míccolis’ ‘plural I’s’ not only in terms of the items, identities, or experiences to be represented, but also in terms of how these ‘plural I’s’ could, in fact, participate in these collecting and/or inscribing acts. In other words, the infant collector proposed by Bortolozzi and Areda (Citation2017) had to be radicalised to include the ‘plural I’s’ in its own body. Moreover, the lesson said to have been learnt with Leonilson also meant a need to consider more creatively the items we could store, but also produce from this ‘plural I’.

In a moment of high creativity, resembling the conditions that mark the paradigm shift that Hall (Citation2001) describes, several projects were central to reimagine our archival orientations and the idea of community we wanted to perform. With the live series ‘Laboratório de Memórias’ we invited other community archives of Latin America to share their practices and inspire us to think about what we actually meant by concepts that were taken for granted, such as memory and LGBT+ community.Footnote17 In conversation with María Belén Correa, a historical trans activist and one of the founders of Archivo de la Memoria Trans (Argentina), we learnt how a bottom–top model would be important to think about an old necessary task: the production of an inventory. If archival theories and methods were surely incorporated by the Archivo de la Memoria Trans, their incorporation was in grassroots terms and through clear political activations, such as the creation of job positions or professionalisation programmes for trans people, and the discussion of political and civil rights also in the present time. With the documentary series Transur Historias Invisibles (Uruguay), we also comprehended how a simple device such as a cellphone camera could be an incredible resource to record memories and produce histories.

Highlighting the importance of recording the ‘invisible histories’ of trans subjects in Argentina, Brazil, and Uruguay, the Uruguayan multiartist Sofía Saunier recognised how the first videos she recorded indeed had many technical problems. Notwithstanding, at the time of the interview (2021), she mentioned how even though, during the previous eight years, she could produce more than 60 interviews, and it was throughout this process (and not prior to it or later on) that she then had access to better equipment and developed editing, camera, and interviewing skills. Atrevidamente (Boldly), Saunier taught us how the fearlessness of attempting to record these stories, even without the proper equipment, is more important than any technological concern. With Transur, we learnt that the conditions of invisibility and social marginality are not only present in the archive as past temporalities, but also in the possibilities of recording and producing dissident narratives in the present. In a few words, if Saunier had waited for the ‘standard’ conditions for producing Transur, it would have never been possible, so embracing this archival/recording desire over the technical restrictions may become the enabling condition for (perhaps) a more ‘professional’ future (something that we would surely understand when we started our inventory), shifting the temporality of many archive paradigms.

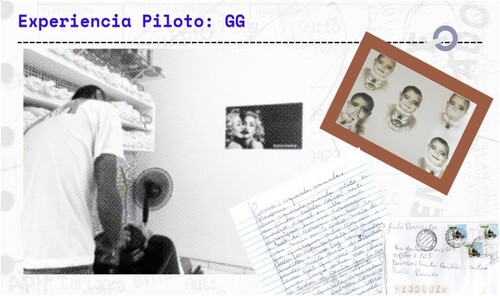

Listening to these activists created an effect of both realising we could produce different things, even with limited resources, targeting a broader audience; and thinking what we meant by community, memory, and history in dialogue with other individuals and collectives. Instead of interpellating them as a way of learning about history or ‘what happened’, assuming external milestones we realised that these different ‘rags’ we could produce would be more interesting if we took a step back, and first established dialogue possibilities to learn how these subjects would frame their lifeworlds and the place memory and history have in them. As an example, during the production of Passagem só de ida (in English, One-way Ticket), a podcast about queer migrations to São Paulo, we noticed how older generations would use different identity labels to describe their sexualities and gender identities; thus, their life stories would slip from the general historical milestones assumed by the mainstream scholar historical narratives on the topic in Brazil and the archives they usually report to (the police, cis-straight or gay liberation media, and the medical-legal discourse). That difference also occurred in a material dimension: in many cases, our archive did not have any material directly related to their reported experiences. In that context, we started to think of post-custodial strategies,Footnote18 such as the digitalisation of personal archives (letters, photographs, certificates), and different media records, such as the invitation for making a playlist of the person’s life. And, from this production, instead of looking at their lives from the archive, we would try to look for items in the archive from this new source of knowledge, which expanded from the individual trajectory to a wider and shared social and cultural context ().

Figure 2. Photos and letters of GG, the first interviewee of Passsagem Só de Ida. The picture of GG working (on the left) was taken in his hair-dresser saloon, in Pindamonhangaba, São Paulo, Brazil. The picture was sent by GG in 2020. The other archival pieces were sent together and were produced in different moments of GG’s life.

With the podcast, Acervo Bajubá began formulating a method that was later replicated in other projects. This method essentially involves inviting other collectives or social movements to consider potential memory activations, leading to temporary alliances that explore dissonances and convergences. Through this process, plural modes of engagement and activation of the items in Acervo Bajubá’s collection are envisioned, while also opening possibilities for adding other items to this repository. This method in a certain way resembles the ‘queer/ed archival methodology’ Jamie A. Lee (Citation2017) proposes, in particular thinking of how this always-shifting, embodied archivist can disrupt the stability of the body of knowledge present in an archive, shifting contexts/contents; shifting method/archivist for experiences that led to different productions, such as the podcasts or the many creative writing workshops we nowadays carry out in different institutions and with the participation of different audiences.

We also realised that sharing this space together resulted in affective attachments not only to the archive, but also among us. There was also something going on beyond this relation to the past, as the possibilities of use and access of these documents in the present time also made us aware of the barriers in terms of access and how they echoed the different positions, presences, and ways of representation of dissident bodies in the archive. In that sense, the different material conditions of the present mirrored different presences and representations in the archive. In simpler terms, the individuals and groups that were underrepresented in our archival repository were also the ones with more barriers to participate in the projects of Acervo Bajubá in the present time. Furthermore, as we transitioned back to in-person activities after the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic, many of us still felt inadequate to fully engage with this archive. Despite dedicating two years of continuous effort, the demands imposed by the paradigms of History and Library Science would resurface intermittently by many visitors and experts who would know about our project, and addressing them seemed impossible given our limited resources and conditions.

From the many projects and reflections we had in this moment, I choose to focus on a dialogue between two art-pieces produced in this context, as they better express a way of doing things, and offer reflections that were central both in the virtual rethinking of this collection, and also on this hard way back to the physical experience of an archive, sometimes making it difficult to establish a decisive temporal division. Both of these pieces seek to dialogue with embodied experiences of gender and sexuality, conceiving not only the different experiences and identities included or represented in the items of our archive, but also caring about the presence of different bodies in the archive as archivists in the present time. These artworks wonder about the ethical possibilities and choices in these labours of memory that may arise when we think about the two proposed questions: Whose memory is it? Who takes care of our memories?

Who takes care of our memories? Whose memory is it? The archive and the cafezinhoFootnote19

Sharing coffees in public and private spaces is a cultural habit in many regions of Brazil. In some situations, like when visiting a company or at work, we may drink a cafezinho in plastic disposable little cups despite the release of the dioxin enabled by the heat. Even knowing that, sometimes we just place another cup around the semi-melted former one. I refer to this materiality as it is the first reference that comes to my mind when remembering both our departure from Casa 1 and the arrival at Grupo de Incentivo à Vida, the HIV/AIDS NGO that houses us, and the beginning of the inventory process.

Because it was there, in this return to in-person activities, their banal everyday and unworried exchange, that after terrible months of a pandemic we started to get used once again to be with each other beyond virtual spaces and actually touch the archive. And when I think of that gesture, I think of Natan’s hand offering a cafezinho. I remember our initial exchanges, those coffees we shared and also our shyness, fear, and strangeness of approaching this archive. I could be wrong, but there was something in our presence, in these bodies circulating in this space, that seemed to escape our possibilities and desires. I do not say fear, but there was certainly a feeling of awkwardness, of inadequacy, of apprehension.

In this moment, we had constant visits of archive experts and academic researchers, who would always suggest many ways of doing the inventory, the best preservation practices and systems to manage this information. Notwithstanding, beyond the pressure and anxiety we would feel in this process, the suggestions would never materialise in actual efforts. It was at this point that we realised that this imbalance was nothing more than a result of the different affective attachments to the idea of an archive and what it should be. This non-presence could be read as a clear allegory of a dematerialised perspective of archive, a repertoire that conceives these best practices based in a distanced relationship between researchers and the archives. And more than the acknowledgement of our precarious conditions to enact this type of archive, we realised that our archival desire would probably be in this non-stabilising notion of archive that we would enact in every project, performing a different idea of community.

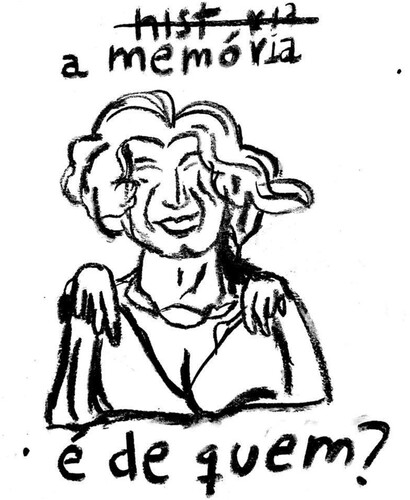

It is at this nod that Miss Biá in Charcoal was produced (). From the invitation of Bruno O., I drew in charcoal the image of Miss Biá, a São Paulo transformista,Footnote20 and wrote the question: ‘Whose memory?’ Her smile, a punctum, captures us as though she was ready not to answer but listen to the different answers to this question – an aspect closely related to one of her most famous performances: Herbe.

Miss Biá was a constant presence at the two most famous nightclubs of São Paulo’s transformismo: Nostro Mondo and Medieval, both of which opened in 1971. At these venues, she would lip-sync to iconic divas such as Liza Minnelli. However, she identified herself more as a ‘caricata’, an emic category for a more comedic performance. As she ‘confessed’ in a short interview with the newspaper Folha de São Paulo, published on 23 April 1995: ‘I’m a kind of caricata, I can’t appear too serious; even a glance from me can be funny.’

Indeed, the reference to this drawing was the photograph included in this interview which promoted Miss Biá’s performance of Herbe at Nostro Mondo: an impersonation of the famous Brazilian talk-show presenter Hebe Camargo. Miss Biá was a costume designer and make-up artist at TV Bandeirantes at the same time Hebe Camargo worked there. In her performance, Miss Biá would set the traditional sofa of Hebe’s programme and invite the same artists that would go to the original show.

I resort to this performance, as we may think with Miss Biá’s performance itself, in terms of how, instead of searching for evidences, we can conceive other relations to LGBT+ history and memories beyond content, and rather formulate those relations as an invitation to perform and embody the subject we wish to activate in the different archival adventures we may take. And by doing it, perhaps the community that emerges may resemble the community that once was alive. That was the proposal of Acervo Bajubá’s exhibition ‘Porta de Boate’ (Nightclub’s Door) in June 2023, at Bananal Espaço de Arte e Cultura (São Paulo), where Miss Biá’s sofa was performed as a memory/history device based on the intergenerational dialogue between younger transformistas and performers like Marcinha do Corintho and Gretta Star, contemporaries of Miss Biá.

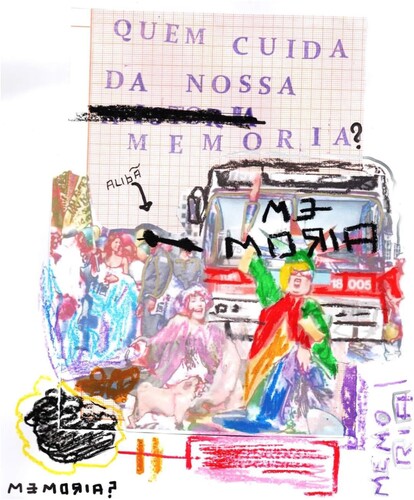

It is also at this point that a possible connection with Natan’s piece (), made in dialogue with Miss Biá in Charcoal, may make sense. Asking ‘who takes care of our memories?’, Natan expands my question by conceiving that there is always a subsumed ‘we’ in any memory effort, and that oftentimes this ‘we’ of ‘our memories’ is someone else, but not the one who takes care of the memories, as the distanced ‘who’ (quem) the image represents.

Thinking of subjects, the piece portrays Kaká di Polly, a historical São Paulo drag queen, dressed as the Statue of Liberty in front of a public-transport bus. This scene reports to her important role in the first São Paulo Pride in 1997, when she challenged the police by lying in front of a bus, impeding the traffic flow which would not permit the realisation of the first pride rally at the Paulista Avenue.

Natan’s question in fact resonates with some of Kaká di Polly’s critique by the end of her life on the forgetting of important political actors, despite the many LGBT+ ‘memory’ and ‘history’ politics and narratives, including in São Paulo Pride’s own organisation in 2020, which did not invite important social and political activists.Footnote21

Thinking of Kaká’s embodiment along Miss Biá’s willingness to listen can be read as decolonial inspirations for an archive that refuses the disembodiment of notions of history, memory, and community, and casts doubts on any disembodied idea of community as representation. Ultimately, what Acervo Bajubá proposes instead is a grammar of action that refuses the idea of community as a mere representation, betting on an idea of community as something that we in fact do:

As a community practice, our bet is to break with the musealization of the past and the objectification of the present. It is to operate other listening and speaking devices that make a circle be established between the experiences of the bodies that move and are present in this space in the present and that look, touch and consider these books not as crystallized knowledge of a past, but as a possibility for an act of recognition of the lives and bodies calcified in these archive-devices. (Fraccaroli Citation2023, 17)

A few (in)conclusive thoughts

By the second revision of the present article, Acervo Bajubá promoted a project called ‘Porta de Boate’, at Espaço Bananal (São Paulo). It was a collective research project focusing on the histories and memories of transformismo in São Paulo. In this process, many São Paulo nightclub advertisements of the 1970s and 1980s were found for the first time in the archive by a collective that was organically constituted to curate this exhibition. The advertisements were reproduced in bigger dimensions and assembled with wigs, towels, make-up, and other objects used by transformistas themselves to dress up.

One of the biggest objects assembled by the exhibition was a comber borrowed and actually used by Lufer Sattui, a Peruvian transformista based in São Paulo, who was part of the collective. In the mirror of the comber, written in lipstick, it could be read: ‘Support the transformista art. Donate.’ As a Pride month exhibition, different activations were planned, including the performance of the aforementioned Miss Biá’s sofa, a space wherein older and younger generations of transformistas could share memories of their performances and lifetime experiences. Being abroad, I could see some pictures and videos of the exhibition, however, there was a sense of frustration of not being able to be there and experience the different dialogues, from the initial ‘plural I’ constitution to the chosen activations.

I draw on this example as it clearly demonstrates the argument this article has attempted to build: by constituting a temporary alliance of queer archivist bodies in the present, many advertisements and materials were found and then included in that curatorship. Certainly, a different group of people and a different set of conditions of time and resources would result in another production of the ‘we’ the curatorship tried to express.

Bringing this ‘queer’ archivist constitution and its archival options to the forefront, alongside the inclusion of objects used by transformistas and the enactment of performances inspired by the research, clearly makes us aware of the limits of the calcified/calcifying devices that usually constitute an archive, such as books, articles, and photographs. This performative notion of archive evinces then the limitations of such records as it clearly gestures to the recognition of a lived material reality from which they depart and seek to represent – and, consequently, there is always going to be something left behind or not fully considered. A position that takes into account the limits of the separable categories through which modernity organises the world ontologically, as observed by the decolonial feminism of María Lugones (Citation2010, 746), who instead proposes an emphasis ‘on ground, on a historicized incarnate intersubjectivity’.

In that frame, this performative notion suggests the lived importance of building community as this shared position may define other relations to the past, beyond the mere concern with representation, thinking about the multiple possibilities of re-enactment of history through different media and social technologies, and reflecting on what these activations may mean or signify beyond disembodied notions of evidence, truth, or any other traditional concern related to History.

What Lufer’s comber teaches us is the importance of care work and ethics in the present time. It offers a critical insight into how a disembodied notion of archive may indeed reproduce the same conditions that made Darcy and Cassandra’s Nanjing be forgotten and exposed to mould. It is an invitation to think how many archival paradigms may not be possible to be deployed from certain material conditions, but also a recognition that, beyond it, they may not even be desired by these archivists.

It is by the experience of a lived archive, allowing the constitution and participation of the ‘plural I’s’ as archivists, researchers, and knowledge producers that enact a different concept of time, history, and memory, wherein academic discourses are displaced by localised and materialised knowledge, experiences, and practices. It is certainly by the expansion of the radical possibilities of participating in the creation and development of other relations to the archive and its constitution that a critique on the limits of the colonial archive may emerge. Beyond the need to think about the different modes of reading (i.e. along or against the grain), decolonising the archive requires a reflection about the enabling conditions of who is legitimate to inhabit the archive and what positions are legitimised as epistemologies, and not as objects/contents. As we have learnt with Saunier, the coloniality of knowledge shapes the possibilities of producing the archive, and so, if the goal is to decolonise the archive, an act of epistemological recognition must be pursued, including the redistribution of economic and symbolic resources beyond academic concerns; an embodied critical instance proposed by many community archives across the global South which academic researchers may learn with/from.

Acknowledgements

I thank Bruno O., Florence Belladonna Travesti, Lufer Sattui, and Marcos Tolentino, knowledge producers and memory workers of Acervo Bajubá. I am very grateful for the generosity of Natan (on Instagram @cancerianatan), also a memory worker of Acervo Bajubá, for sharing their artwork for this article. I would like to acknowledge and thank the insights, questions, and critiques I received during a keynote at the panel ‘Queer Echoes’, in the Gender Matters Symposium (The New School for Social Research, 2023), organised by Dr. Chiara Bottici and João Eduardo Freitas. In that event, Dr. Zeb Tortorici (NYU) provided insightful recommendations for the present text. Beyond this panel, I am also in debt to Dr. Maeghan Miller-Likhethe and her seminar ‘Global Archives’ at the Global Studies Department, UC Santa Barbara (Fall, 2022), where the first version of this text was produced. Finally, I would like to thank Dr. Debanuj DasGupta (UCSB) for the initial reflections on the notion of ‘archive’ and Dr. Elizabeth Marchant (UCLA), responsible of the ‘Independent Studies’ I took, for the readings and the final writing of this piece during the Spring of 2023.Funding

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Yuri Fraccaroli

Yuri Fraccaroli (they/them) is a PhD student in Feminist Studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara, USA and an active member of Acervo Bajubá. Their academic work is informed by the epistemologies and methods of Acervo Bajubá. This article is the result of an intense involvement with Acervo Bajubá (2020–2022). The main argument of this piece, against disembodied notions of archive, is inspired by all cleaning activities, the boxes we packed and carried in our address change in 2021, the countless rides I took with Bruno O., and all other invisible (and, for some, minor) labour that shapes Acervo Bajubá. Postal address: Department of Feminist Studies, 4631 South Hall, University of California, Santa Barbara, CA 93106-7110. Email: [email protected]

Notes

1 Indeed, Eichhorn (Citation2014) has critically challenged this either–or model, showing how some feminist archives and archivists in the US have an in-between position regarding activism and academia. With that I mean that one dimension does not necessarily deny the other. About the troubles of a positionality in between activism, arts, and academia, I am also inspired by Curiel’s memories in Sacchi et al. (Citation2021, 335).

2 The expression ‘scale-up’ is inspired by Kathi Weeks (Citation2021), here used as a desire for going beyond the localised nuisance and inserting the questions I draw here in a broader political economy of knowledge production.

3 Of uncertain origins, pajuba or bajuba is a linguistic style ‘built on lexical borrowings of various kinds, but particularly from the Yoruba language. First articulated by travestis, today it has not only been popularised to other LGBTIQ groups in Brazil, but some of its words have also entered the mainstream vocabulary as well’ (Araújo Citation2022, 292). Still according to Araújo, it is important to consider the circulation of Pajubá in Candomblé religion and its roots in Yoruba-Nago languages of West Africa, with its original uses meanings ‘secret’ or ‘mystery’, but also constituted by a series of shifting meanings by queer speakers, turning into ‘news’ or ‘gossip’ (Araújo Citation2022, 292).

4 Although I recognise ‘LGBT+’ as a Western and contested category that limits the diversity and historicity of the embodied experiences, subjectivities, practices, and identities of sex-gender dissidences, including the own linguistic notion of Bajubá, I choose to use this term to respect the political choice of Acervo Bajubá. The use of this terminology is justified by Bajubá due to conditions of communication and access, as proposed by a partner organisation, the political collective #VoteLGBT. Collecting public data and producing reports since 2016, #VoteLGBT chooses that term based on the following argument: ‘Every time we change or increase the acronym, we distance ourselves a little more from the non-activist population, which is a very important part of our audience. #VoteLGBT understands that the transformation of society towards the full participation of people requires the contribution of many people, and as an institution, it has chosen to solidify the acronym “LGBT+” because, on the one hand, it appeals to something better known (“LGBT”) and, on the other hand, it shows that there are more people to consider (“+”)’. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5b310b91af2096e89a5bc1f5/t/62839ef52f76f546de002ce0/1652793081067/220517_vote_relatorio_2022.pdf.

5 ‘The magistrate who is really in Derrida’s text, exercises a power he doesn’t always actually have, that has already always been inaugurated somewhere else’ (Steedman Citation2002, 44).

6 On the coexistence of different archival paradigms, and competing approaches, such as evidence and memory, see Cook (Citation2013).

7 ‘The meaning of archive, its only meaning, comes to it from the Greek arkheion: initially a house, a domicile, an address, the residence of the superior magistrates, the archons, those who commanded … To be guarded thus, in the jurisdiction of this stating the law, they needed at once a guardian and a localization. Even in their guardianship or their hermeneutic tradition, the archives could neither do without substrate nor without residence. It is thus, in this domiciliation, in this house arrest, that archives take place’ (Derrida & Prenowitz, Citation1995, 9–10).

8 In that regard, thinking of the transgender archive, Lewis (Citation2014) ponders about the risks of considering queer history as transparent and referential, advising us of the inherent foreclosures in the intelligibility process by which the subjects of the archive are frequently rendered: the deauthorisation of their lifeworlds through a translation based in the primacy of the historian and their episteme. In such a frame of epistemic violence, Lewis envisions a possibility of a deep sense of accountability, in which instead of considering the archive itself as a challenge, we must provincialise History and wonder if ‘the archive will submit to our engagements in the first place’ (Lewis Citation2014, 28).

9 For example, Gonzalez (Citation2020) observes how the ‘economic miracle’ that happened during the 1960s impacted the geographic regions of Brazil and racial groups in different ways, putting macro historical narratives into doubt.

10 Thinking of these intersections between materiality and political goals, the visual artist Bruno O. understands Acervo Bajubá’s activities as políticas do chão produced by tecnologias do chão. Chão means ‘floor’ or ‘ground’ in Brazilian Portuguese, hence this conceptual articulation means something close to politics of the ground, produced by technologies of the ground, in a sense of different social technologies that are produced/articulated departing from the floor we step on. Hence, ‘floor’ is understood in relation to the social and political actors that step on it, their political desires, economic possibilities, and the dialogues that are then produced with the available and created technologies. In that context, there is no separation between the local reality that is lived and the discussions that are motivated through the methods that are locally conceived and performed. The source of this concept is based in the personal and community memories of a lived practice not reduced or reducible to the act of writing or any written record.

11 What I write here is also a result of the many negotiations that result from these different spaces, grammars, and repertoires in relation to my positionality, a ‘global South’, as a queer scholar of colour.

12 The use of Clare Hemmings to think about archives is based in Eichhorn (Citation2014).

13 For a summary of this critique, see Fraccaroli (Citation2022).

14 In particular, I am inspired by the comments of Bliss (Citation2015, 87–8) on the politics implied in seeing Black feminism beyond a simple interdisciplinary framework or party programme, and how racialised and gendered dimensions have prevented from seeing it as a theory.

15 Remom Matheus Bortolozzi holds a PhD in Collective Health (University of São Paulo). He is a Psychology professor at Pontíficia Universidade Católica (PUC/PR) and was one of the founding members of Acervo Bajubá. Remom frequently teaches courses on the histories and memories of LGBT+ communities in Brazil and his current research project is focused on the solidarity mechanisms that the LGBT+ communities developed to face the HIV/AIDS epidemics.

16 Testimony present in the virtual exhibition ‘Clippings, Patches, Snippets and Reports: Browsing Through LGBT+ Memories’. https://artsandculture.google.com/u/1/story/iQURZdWsiQ2_-g (accessed 15 May 2023).

17 Acervo Bajubá and Casa 1 (2021) ‘Laboratório de Memórias’ | Video Series (YouTube Videos). https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PL2dRUoriDfmtrgqTg-i0pZ9uaydzfD5Y3 (accessed 15 May 2023).

18 According to the Dictionary of Archives Terminology, post-custodial is defined as an adjective related to ‘situations where records creators continue to maintain archival records with archivists providing management oversight even as they may also hold custody of other records. The literature on post-custodial thinking understands it as possibilities of shared governance and ownership (Zavala et al. Citation2017) and recognises that collecting and preserving records is not enough’. Agostinho (Citation2019, 151) signals the importance of post-custodial thinking in democratising access and care, shifting from the dependence on archival repository to the prioritisation of the ‘context of records creation’ over ‘records content’: ‘In this way, the entire community becomes the larger provenance of the records, and all layers of society are seen as equal participants in the making and interpretation of records’.

19 This section contains some of the central elements of Fraccaroli (Citation2023).

20 Although for an English-speaking audience a translation to drag queen could certainly help the comprehension, transformista is an emic category with common and different historical roots in Latin America, and transnational dialogues beyond it. In the Brazilian context, the superstar Rogeria and the show Les Girls, which circulated in South America, are probably the main reference. With articulations since the 1950s, transformistas’ performances would rely on the embodiment of a glamorous femininity based on Hollywood divas, but also French musicals. For an interesting attempt at historical periodisation of Brazilian trans performances on stage, see Jayo and Meneses (Citation2018).

21 Observatório G (2020) ‘Drag queen paulista critica falta de ativismo em Parada LGBT virtual de SP’. 19 June. https://observatoriog.bol.uol.com.br/noticias/drag-queen-paulista-critica-falta-de-ativismo-em-parada-lgbt-virtual-de-sp.

References

- Agostinho, Daniela (2019) ‘Archival encounters: rethinking access and care in digital colonial Archives’, Archival Science 19(2): 141–165. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10502-019-09312-0

- Anjali, Arondekar (2005) ‘Without a trace: sexuality and the colonial archive’, Journal of the History of Sexuality 14(1–2): 10–27. https://doi.org/10.1353/sex.2006.0001

- Appadurai, Arjun. (2003) ‘Archive and aspiration’, in Joke Brower and Arjen Mulder (eds.) Information is Alive - Arts and Theory on Archiving and Retrieving Data, Rotterdam: V2_NAI Publishers, 14–25.

- Araújo, Caio S. (2022) ‘Pajubá’, in M. Dilip and D. M. Menon (eds.) Changing Theory: Concepts from the Global South, London: Routledge India, 291–305. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003273530-26

- Arondekar, Anjali, Ann Cvetkovich, Christina B. Hanhardt, Regina Kunzel, Tavia Nyong’o, Juana María Rodríguez, Susan Stryker, Daniel Marshall, Kevin P. Murphy and Zeb Tortorici (2015) ‘Queering archives’, Radical History Review 2015(122): 211–231. https://doi.org/10.1215/01636545-2849630

- Bisaillon, L., A. Cattapan, A. Driessen, E. van Duin, S. Spruit, L. Anton and N. S. Jecker (2020) ‘Doing academia differently: “I needed self-help less than I needed a fair society”’, Feminist Studies 46(1): 130–157. https://doi.org/10.1353/fem.2020.0010

- Bliss, James (2015) ‘Hope against hope: queer negativity, black feminist theorizing, and reproduction without futurity’, Mosaic: A Journal for the Interdisciplinary Study of Literature 48(1): 83–98. https://doi.org/10.1353/mos.2015.0007

- Bortolozzi, Remom M. and Felipe Areda (2017) ‘Nosso caos, nosso cosmos: notas sobre a memória e a cultura LGBT Brasileira’, Uniletras 39 (2): 157–173. https://revistas.uepg.br/index.php/uniletras/article/view/9820

- Cook, Terry (2013) ‘Evidence, memory, identity, and community: four shifting archival paradigms’, Archival Science 13(2–3): 95–120. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10502-012-9180-7

- Derrida, Jacques and Eric. Prenowitz (1995) ‘Archive fever: A freudian Impression’, Diacritics 25(2): 9–63. https://doi.org/10.2307/465144

- de Jong, Ferdinand (2016) ‘At work in the archive: introduction to special issue’, World Art 6(1): 3–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/21500894.2016.1176391

- Eichhorn, Kate (2014) The Archival Turn in Feminism: Outrage in Order, Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

- Fraccaroli, Yuri (2022) ‘Dissidentes sexuais e de gênero e a ditadura civil-militar brasileira: entre a memória política e as memórias cotidianas’, Revista Uruguaya de Ciencia Política 31(1): 25–53. https://doi.org/10.26851/RUCP.31.1.2

- Fraccaroli, Yuri (2023) O arquivo e cafezinho, São Paulo: Autoria Compartilhada. https://acervobajuba.com.br/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/cafezinho_pb.pdf.

- González, Lélia (2020) Por um feminismo afro-latino-americano, Rio de Janeiro: Zahar.

- Green, Renée (2014) Other Planes of There: Selected Writings, Durham: Duke University Press.

- Hall, Stuart (2001) ‘Constituting an archive’, Third Text 15(54): 89–92. https://doi.org/10.1080/09528820108576903

- Hemmings, Clare (2011) Why Stories Matter: The Political Grammar of Feminist Theory, Durham: Duke University Press.

- Jayo, Martin and Emerson S. Meneses (2018) ‘Presença travesti e mediação sociocultural nos palcos brasileiros: uma periodização histórica’, Revista Extraprensa 11(2): 158–174. https://doi.org/10.11606/extraprensa2018.144077

- Kang, Laura. H. Y. (2009) ‘Epistemologies’, in Philomena Essed, David T. Goldberg and Audrey Kobayashi (eds.) A Companion to Gender Studies, New Jersey: Blackwell, 73–86.

- Lee, Jamie A. (2017) ‘A queer/ed archival methodology: archival bodies as nomadic Subjects’, Journal of Critical Library and Information Studies 1(2): 1–27.

- Lewis, Abram J. (2014) ‘I Am 64 and Paul McCartney doesn’t care’, Radical History Review 2014(120): 13–34. https://doi.org/10.1215/01636545-2703697

- Lira, Andrea, Ana L. Muñoz-García and Elisa Loncon (2019) ‘Doing the work, considering the entanglements of the research team while undoing settler colonialism’, Gender and Education 31(4): 475–489. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540253.2019.1583319

- Lugones, María (2010) ‘Toward a decolonial feminism’, Hypatia 25(4): 742–759. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1527-2001.2010.01137.x

- Mawani, Renisa (2012) ‘Law’s archive’, Annual Review of Law and Social Science 8(1): 337–365. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-lawsocsci-102811-173900

- Morais, Paula Lais Pombo (2023) ‘Vamos brincar de gatinho?’: Lesbianidades em Eu sou uma lésbica, de Cassandra Rios (Master’s Thesis, Federal University of Goiás), https://repositorio.bc.ufg.br/tede/handle/tede/12776 (accessed 14 August 2023).

- Ochoa, Marcia (2019) ‘La ciudadanía ingrata. El lugar sin límites’, Revista de Estudios y Políticas de Género 1(2): 69–83.

- Sacchi, Duen, Ochy Curiel, Marlene Wayar and John M Hughson (2021) ‘Disobedient epistemologies and decolonial histories’, GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 27(3): 329–344. https://doi.org/10.1215/10642684-8994042

- Simonetto, Patricio and Marce Butierrez (2022) ‘The archival riot: travesti /trans* audiovisual memory politics in twenty-first-century Argentina’, Memory Studies 16(2): 280–295. https://doi.org/10.1177/17506980211073099

- Steedman, C. (2002) Dust: The Archive and Cultural History, New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

- Stoler, Ann Laura (2009) Along the Archival Grain: Epistemic Anxieties and Colonial Common Sense, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Taneja, Anand V. (2017) Jinnealogy: Time, Islam, and Ecological Thought in the Medieval Ruins of Delhi, Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Tortorici, Zeb (2018) Sins Against Nature: Sex and Archives in Colonial New Spain, Durham: Duke University Press.

- Weeks, Kathi (2021) ‘Scaling-up: a marxist feminist archive’, Feminist Studies 47(3): 842–870. https://doi.org/10.1353/fem.2021.0039

- Zavala, Jimmy, Alda Allina Migoni, Michelle Caswell, Noah Geraci and Marika Cifor (2017) ‘‘A process where we’re all at the table’: community archives challenging dominant modes of archival practice’, Archives and Manuscripts 45(3): 202–215. https://doi.org/10.1080/01576895.2017.1377088.