ABSTRACT

Dissociative Identity Disorder (DID), formerly Multiple Personality Disorder, involves two or more distinct identities controlling behaviour, stemming from trauma-related dissociation. Understanding DID’s cognitive, neural, and psychometric aspects remains a challenge, especially in distinguishing genuine cases from malingering. We present a case of a DID patient with nine identities, evaluated to rule out malingering. Using the Millon Index of Personality Styles, we assessed the primary and two alternate identities, revealing marked differences. High consistency scores support validity. We suggest employing personality inventories beyond symptomatology to characterise dissociative identities’ consistency and adaptation styles, aiding in malingering assessments in future studies.

Introduction

Dissociative identity disorder (DID), formerly known as multiple personality disorder, is characterized by two or more identities (or personalities) that control a person’s behavior and affects 1.1% to 1.5% of the general population (Johnson et al., Citation2006; Sar, Citation2011). Typically, each identity has their own first-person perspective, self-awareness, personal history, self-image, and name (Nijenhuis & van der Hart, Citation2011; Putnam et al., Citation1986; van der Hart et al., Citation2005). These totally or partially compartmentalized identities are believed to be the product of dissociative defense mechanisms that unfold in the face of inescapable psychological trauma (Gleaves, Citation1996), most likely during childhood (Gušić et al., Citation2016; Lewis et al., Citation1997; Tamar-Gurol et al., Citation2008). A common clinical and forensic concern is the detection of malingerers (Brand, McNary, et al., Citation2006; Brand et al., Citation2019; Loewenstein, Citation2020; Pietkiewicz et al., Citation2021). i.e., individuals who simulate DID symptoms for secondary gain. Some malingerers may even feign DID symptoms for no gain other than assuming the role of a patient, as in factitious disorders (Armstrong, Citation1999; Brown & Scheflin, Citation1999). Therefore, developing tools to discriminate between real DID patients and malingerers has become a prime concern in the field.

One of the hallmarks of DID is inter-identity amnesia (IIA), which refers to the inability of different identities to remember events experienced by other identities. However, the validity of IIA assessment has been questioned by numerous studies. Researchers have utilized both explicit and implicit memory tests and have discovered that the performance of one identity can be influenced by the contents learned by another identity (Allen & Movius, Citation2000; Huntjens et al., Citation2002, Citation2007; Nissen et al., Citation1988). These findings include procedural (Huntjens et al., Citation2005), episodic (Huntjens et al., Citation2003; Marsh et al., Citation2018), and autobiographic memory contents (Huntjens et al., Citation2012, Citation2016). The discovery of the effect on autobiographical memory is particularly significant since the trauma-cantered theory of DID suggests that IIA should be most prominent in autobiographic content (Bryant, Citation1995; Dalenberg et al., Citation2012). Although some identities may focus more on traumatic memories (trauma identities) while others avoid them (avoidant identities), researchers have not found IIA to be specific to them. While TIs may retrieve more trauma-related memories than other identities, they do not exhibit IIA (Huntjens et al., Citation2014, Citation2016). Therefore, memory assessments have not been effective in distinguishing real DID patients from malingerers.

A promising venue is the study of the neural correlates of DID (for a systematic review, see Roydeva & Reinders, Citation2021). Structural MRI studies have reported reduced volumes in brain areas such as the hippocampus, parahippocampal gyrus, and amygdala in DID patients compared to healthy controls (Blihar et al., Citation2020; Dimitrova et al., Citation2023; Ehling et al., Citation2007; Vermetten et al., Citation2006), although recent studies have failed to find differences in amygdalar volume (Reinders et al., Citation2022). Differences in brain function have also been found, with DID individuals showing differences in regional cerebral blood flow in specific brain regions (Reinders et al., Citation2012, Citation2016; Sar et al., Citation2001, Citation2007). Studies have also explored differences in emotional reactivity between DID identities, with trauma identities showing stronger activation in certain brain regions than avoidant identities when presented with emotional stimuli (Reinders et al., Citation2014; Schlumpf et al., Citation2013, Citation2014). Finally, cortical and subcortical structural similarities have been found between DID-PTSD (patients suffering from both DID and posttraumatic stress disorder) and PTSD-only patients, with both groups having lower gray matter volume in certain brain areas compared to healthy controls (Chalavi, Vissia, Giesen, Nijenhuis, Draijer, Barker, et al., Citation2015; Chalavi, Vissia, Giesen, Nijenhuis, Draijer, Cole, et al., Citation2015). DID-PTSD patients also had smaller hippocampal and larger pallidum volumes compared to controls, and larger putamen and pallidum volumes compared to PTSD-only patients. More recent studies have delved more into the relationship between dissociation and PTSD (Lebois et al., Citation2021; Lebois, Harnett, et al., Citation2022; Lebois, Kumar, et al., Citation2022), shedding light on the relation between them. While these findings and others is still ongoing and show promising, the pursuit of identifying neural markers of DID is still ongoing.

Assessing DID with personality inventories

Studies assessing DID have employed structured interviews (Brand, McNary, et al., Citation2006), scales and questionnaires (Labott & Wallach, Citation2002; Vissia et al., Citation2016; Welburn et al., Citation2003), and personality inventories (Coons & Milstein, Citation1994) to discriminate between genuine patients and malingerers or simulators. However, these assessments may be insufficient to determine malingering volition (Drob et al., Citation2009).

The Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI/MMPI-2) has been repeatedly used to identify psychometric signatures of DID. However, DID patients often produce invalid profiles by elevating clinical scales such as Schizophrenia, Psychopathic Deviate, and Depression (Brand & Chasson, Citation2015; Coons et al., Citation1988; Welburn et al., Citation2003). The Schizophrenia scale strongly correlates with dissociative symptoms in DID patients, particularly in sexually abused women (Brand & Chasson, Citation2015; Elhai et al., Citation2001). DID patients also elevate the Infrequency scale (Brand, Armstrong, et al., Citation2006), which strongly correlates with the Dissociative Experiences Scale (DES; Allen & Coyne, Citation1995) and shows sensitivity to dissociative symptoms. Moreover, the Infrequency-psychopathology scale (Fp) has shown higher sensitivity at discriminating genuine DID patients from simulators (Brand & Chasson, Citation2015). Researchers have found that DID patients endorse items related to dissociation, trauma, depression, fearfulness, family conflict, and self-destructiveness, whereas simulators tend to endorse items consistent with popular media portrayals of DID as paranoid, delusional, antisocial, and unlawful individuals (Brand et al., Citation2016).

The Personality Assessment Inventory (PAI) has also been used to discriminate DID patients from malingerers, using validity scales such as Negative Impression (NIM), Malingering Index (MAL), and the Rogers Discriminant Function (RDF). DID patients often elevate NIM (Stadnik et al., Citation2013); however, this may partly reflect its inability to discriminate exaggerated from dissociative symptoms (Rodewald et al., Citation2011). MAL and RDF have also shown sensitivity to malingering, with RDF displaying higher sensitivity in DID patients (Rogers et al., Citation2012).

In summary, while these assessments have shown sensitivity to malingering in DID, they may not be able to determine malingering volition. Future studies are needed to establish the specificity of these assessments and to explore alternatives.

Here, we present the case of a highly functioning adolescent patient diagnosed with DID through a meticulous clinical assessment. Despite her symptoms, the patient maintained good relationships with family and friends and excelled academically. There was no evidence of primary or secondary gains or any factitious behavior. The patient underwent a standardized assessment protocol, including a widely-used structured interview for DID, evaluation by four independent mental health clinicians, and a psychometric assessment. To enhance the validity of the diagnosis and explore the utility of other instruments, we utilized the Millon Index of Personality Styles (MIPS), which assesses response consistency, positive impression, negative impression, and personality styles beyond psychopathology-inspired classifications. We evaluated the primary identity and two alternate identities, including a trauma identity (TI) and an avoidant identity (AI). Informed written consent was obtained from the patient to present her case study.

Case presentation

A 17-year-old patient, female, at third year of secondary schooling (eleventh year of school education), with excellent performance at school, brought by her sister, consulted with a psychiatrist (JCM-A) claiming to suffer from nine multiple personalities, all female and of diverse ages and personality traits, during the past two years. They reported that these personality “crises,” as they called them, were happening more frequently now, which led them to consult with a psychiatrist.

Initial assessment

The patient was first assessed by JCM-A, who had 20 years of experience diagnosing and treating adolescents with dissociative disorders at the time. She exhibited symptoms of dissociative amnesia, with memory gaps. She described them as “periods when I [she] wasn’t present”. Her sister (a school teacher not at the patient’s school; aged 28), who was present during the first three sessions with JCM-A, helped the patient filling in the gaps; she provided descriptions of her behavior during the episodes of dissociative amnesia when both were in the same room, e.g., at family dinner.

The patient was interviewed several times: with her sister, alone, and with her mother. The psychiatrist employed the Structured Interview for Dissociation Symptoms and Disorders (SCID-D; Steinberg, Citation1994), the Structured Interview of Reported Symptoms (SIRS; Rogers, Citation2010), the Structured Interview for Psychosis-Risk Symptoms (SIPS; Miller et al., Citation2003), and the Diagnostic Interview for Children and Adolescents (DICA-IV; American Psychiatric Association, Citation1994). Routine self-report scales were used to complement the assessment, including the Beck Depression Inventory II and the McLean Screening Instrument for Borderline Personality Disorder (MSI-BPD; Zanarini et al., Citation2003). Only DID, dissociative amnesia, and dissociative fugue diagnostic criteria were met.

The patient lived with her parents and sister; they both described living in harmony as a family and having no relevant conflicts. The patient maintained a close relationship with her sister, feeling confidence and emotional dependency to her. The patient did not report family history of psychiatric disorders, which was later confirmed by her sister. They reported no history of domestic violence, drug abuse, or financial struggle. The patient described her relationship with her parents as good, affectionate, and safe. She reported not using any substances both in sessions accompanied by her sister and when alone.

The patient excelled in school, achieving a grade point average of 6.5 on a 1–7 scale. Additionally, she had a small yet supportive group of friends. She described school as a pleasurable experience but was currently facing stress because her “personality crises” were causing her to miss some days of school.

The patient’s childbirth was uncomplicated, and there were no notable medical incidents during her infancy. Two years prior to her current medical appointment, the patient sought the assistance of another psychiatrist due to the emergence of multiple identities, but the assessment and treatment remained incomplete. When asked about traumatic events, she revealed that a man had threatened her with a knife during a bus trip with the intention of touching her genital area two years prior. She also shared that her best female friend, whom she had an erotic attraction to, had relocated to Canada.

The patient disclosed that she began experiencing changes in her identity two years before her medical appointment. The first occurrence happened during a family dinner at home in early 2011, when she abruptly fled the premises. She expressed:

The first time, it happened while I was having tea with my parents and sister. I stood up, opened the door, and run away to the street. They stopped me, as I was told, because I can’t remember, I began shouting violently: “someone wants to kidnap me… I’m Josefa, a homeless person … a beggar without family.” I couldn’t recognize anyone. Then, I was taken to the hospital.

The patient referred to her experiences as “personality crises,” which progressed in both frequency and duration. Initially, they lasted for two hours, but gradually increased to a week, with complete recovery in-between episodes. She had some recollection of each event, but they seemingly occurred without any clear correlation to stressful circumstances. As she explained:

They are an inner switch… I disappear. At the beginning I was able to remember something, like being in a movie, but I haven’t been able to remember the crises since January [2013]. I can’t remember anything anymore.

She characterized her encounters as ego-dystonic, annoying, and disruptive. She experienced fear and anguish in response to these “personality changes” and actively sought help.

In the initial clinical interview conducted in April 2013, the patient appeared to be of her chronological age. She exhibited full awareness, with no indication of temporospatial disorientation, alterations in prosody, or verbal expression. There were no impairments or variations in her thinking structure or content, such as delirious ideas or sensory-perceptual changes. Psychomotricity was not impacted. The patient did not display symptoms that could indicate mood, personality, or autism spectrum disorders. Her descriptions showed genuine empathetic concern, without any fantasy or exaggeration. There were no signs of voluntary secondary gain or manipulative objectives, such as malingering, during the initial clinical interview (as evidenced in the personality assessment as well; see below). Her moral consciousness was appropriate for her age, and her reasoning was capable of hypothetico-deductive functioning. She demonstrated the ability to envision herself in the future. Overall, her general functioning was considered good for her age and lifestyle.

Despite identifying herself as a quiet, responsible, and shy person with mental stability as her primary identity, she would sometimes adopt a sociable, reckless, and defensive alternate identity that is dissociative in nature. She did not exhibit any signs of social phobia or anxiety disorders, which was confirmed by the results of the State-Trait Anxiety inventory (Spielberger, Citation1983).

When inquired about her fears, she expressed a fear of losing loved ones or being separated from them. She initially identified as homosexual (with no gender dysphoria), but a year later, her sexual orientation was described as bisexual identity (with no gender dysphoria). Results from biochemical profile, electroencephalogram, and computed tomography showed no pathological signs.

In April 2013, the psychiatrist diagnosed her with DID after ruling out other categorical disorders. However, before disclosing the diagnosis and commencing treatment, the patient was referred to three other clinicians for independent assessment, including a child and adolescent psychiatrist, an adult psychiatrist, and a clinical psychologist.

Peer-assessment for dissociative disorders

The patient was first independently assessed by a child and adolescent psychiatrist (LAD) with 40 years of experience evaluating and treating patients with dissociative and personality disorders at the time of assessment. In addition, she was also assessed by an adult psychiatrist (EC) with 38 years of experiencing evaluating and treating patients with mood, anxiety, and dissociative disorders. The two psychiatrists did not work in the same location, were not in contact with each other, and were not informed by the treating psychiatrist (JCM-A) about his diagnosis. Nevertheless, they both independently concluded that the patient was suffering from DID.

Next, the patient was referred to a clinical psychologist (RCL) specialized in cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), medical hypnosis, and psychological assessment, for another independent assessment and subsequent treatment using CBT and medical hypnosis, based on its suggested efficacy for dissociative disorders (Cleveland et al., Citation2015; Deeley, Citation2016; Fine, Citation2012; Kennerley, Citation1996). During the first sessions, the patient was assessed using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM Disorders (SCID-IV; American Psychiatric Association, Citation2000), the Autism Diagnostic Interview Revised (ADI-R; Rutter et al., Citation2003), the SCID-D, the House-Tree-Person Projective drawings (Buck, Citation1977), the Thematic Apperception Test (Murray, Citation1943), and the Adaptive Behavior Inventory (ABI; Brown & Leigh, Citation1986). These instruments were applied to the patient’s primary identity during the first assessment sessions.

During subsequent sessions, the patient’s primary identity, along with two alternate identities (a trauma identity and an avoidant identity), were evaluated separately using the Dissociative Experiences Scale II (DES-II; Carlson & Putnam, Citation1993) to determine the severity of her symptoms. The Miller Forensic Assessment of Symptoms Test (Miller, Citation2001, Citation2005) was also used to assess the possibility of malingering. Of particular note, the assessment of the alternate identities took place on two separate sessions during which the patient introduced herself using a different name. Additionally, the MIPS was employed to evaluate the personality styles and profile consistency of each of these identities (see further below).

The assessment of her primary identity showed signs of dissociative amnesia, frequent depersonalization, and ineffective copying mechanisms. No out-of-body experiences were reported, and her emotional reactivity and social skills appeared within normal performance range. Similarly, the internal structure of her personality was found normal for her age range. However, the assessment including her sister and parent’s observations suggested signs of derealization (e.g., not recognizing family members during dissociative episodes), erratic behavior (e.g., either behaving aggressively or overly quietly), and occasionally presenting self-inflicted small injuries. No signs of factitious or malingering behavior were detected. The clinical psychologist proposed DID as main diagnostic hypothesis and suggested borderline personality disorder as second (though much less likely) possible candidate; this second candidate was ruled out later and the diagnosis of DID was supported by new information gathered in the following sessions with JCM-A and RCL, independently.

Following the treating psychiatrist’s recommendations, the patient underwent outpatient therapy with 10 mg of daily oral escitalopram, 40 mg of daily oral ziprasidone, and CBT including medical hypnosis as adjuvant technique with the clinical psychologist.

Evolution

During May 2013, the patient exhibited three alternate identities: “Alejandra” for a duration of five days, “Josefa” for four days, and “Úrsula” for one day. Although her sister’s departure from the house was initially considered as a possible stressor, the patient reported not experiencing any emotional distress due to this event. The medication plan was subsequently modified, with the discontinuation of ziprasidone and an increase in the dosage of escitalopram to 20 mg.

During June 2013, great improvement was observed: for two weeks the patient only reported one dissociative episode of 30 minutes of duration, after which she did not have dissociative episodes for a month and achieved full attendance at school. However, during July she exhibited an identity switch while at school; this new identity was acknowledged as “Elise.” The patient experienced the aforementioned episode following a discussion with a friend, although the patient did not describe the discussion as being relevant or stressful. Following the episode, the patient consulted with the treating psychiatrist and introduced herself as “Elisa.” During the session, the patient referred to her primary identity (PI) in the third person:

She [PI] is rude to us because she doesn’t like us… she is shy and doesn’t say anything when something bothers her, she doesn’t defend herself and rarely gets angry… she maintains good relationships with her classmates and teachers … she likes her school and classmates, but she is lazy at home. She doesn’t do the household chores.

After this, she switched to her PI. Two days later, she switched to an alternate identity called “Antonia,” self-inflicted wrist cuts, and took an overdose of psychoactive drugs while seemingly in an altered state of consciousness. She was checked into a hospital. During the next two months, she attended psychiatric and CBT sessions; she pointed out that she was unable to remember any of the episodes just described. Additionally, she described feeling a heterosexual attraction toward a man of her same age.

Over the next two months, she exhibited five alternate identities. Her school attendance was erratic. Importantly, she was lost for one night wandering the streets; her symptoms were attributed to a dissociative fugue episode. Furthermore, during this time she maintained an erotic relationship with a female friend. Also, her attendance to psychiatric and CBT sessions decreased in frequency.

Over the next four months, she reported no dissociative symptoms. However, the day before a psychiatric consult, she adopted the alternate identity of “Xiomara.” The patient was enquired about Xiomara’s date of origin, to which she replied:

I’ve been Xiomara since always, I’m 16, I do whatever I want… I don’t work or go to school, but today I appeared inside [PI] while at school because I live inside her, but I don’t talk to her… She doesn’t know me, and I don’t care.

The patient did not return to psychiatric consults after this event, but she kept attending CBT sessions, weekly or bimonthly, until June 2014, by which time her identity switches had decreased in frequency.

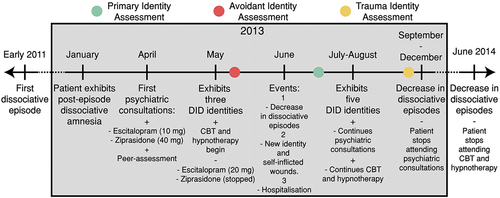

In 2021, RCL contacted the patient to learn about her current state. The patient was about to complete a university degree in speech therapy. She reported still experiencing dissociative crises on occasion; however, they were much less frequent and disruptive than in the 2012–2014 period. See for a timeline of relevant events.

Personality assessment

The MIPS is a 180-item inventory that explores the adaptation style of an individual (Millon, Citation1995, Citation2003). Personality ailments are seen as specific maladaptive personality styles. The MIPS measures each polarity of a personality dimension individually (Aparicio García & Sánchez-López, Citation1999), focusing on three personality areas: motivating styles (the emotional style of an individual at dealing with environmental demands), thinking styles (the cognitive style or thinking approach of an individual), and behaving styles (an individual’s style to interact with others). Importantly, the MIPS includes three validity indices that estimate the extent to which examinees are trying to give a false impression of themselves (e.g., malingering): Positive impression, Negative impression, and Consistency. In Consistency, a score below 3 (out of 5) invalidates the profile (Millon, Citation2003). We assessed three identities: her primary identity (“host”), an avoidant identity (introduced as “Angel”), and a trauma identity (introduced as “Xiomara”). The three identities were assessed one month apart from each other in this order (see ).

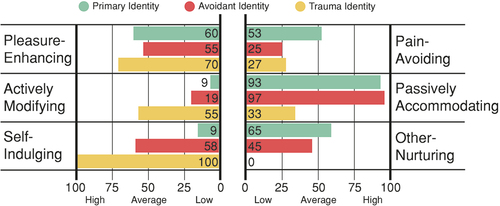

Motivating styles

Motivating styles assesses how individuals deal emotionally with their environment and its reinforcements. The three identities show visible differences in all motivational styles, perhaps except for Pleasure-Enhancing (). While both the primary identity and the avoidant identity showed a strong inclination to adopt a passive stance toward their life events, the trauma identity showed a weaker inclination in this area (Passively Accommodating). Additionally, the three identities showed very different profiles in Self-Indulging and Other-Nurturing; more specifically, while the primary identity showed a low inclination for self-gratification and satisfying her own needs before others’ (Self-Indulging), and a strong inclination to prioritizing others’ needs, the trauma identity exhibited the opposite trend, to an extreme. Remarkably, the primary identity and the trauma identity showed opposite elevations in most scales.

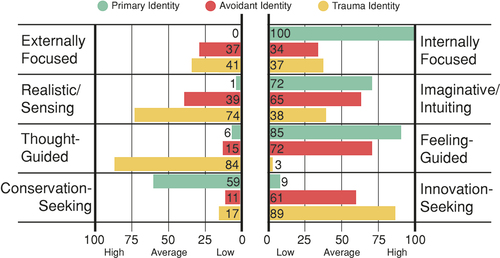

Thinking styles

Thinking styles assesses individuals’ modes of cognitive processing. The three identities showed visible differences in all styles; the largest differences were observed between the primary identity and the trauma identity (): while the primary identity scored extremely low in Externally Focused and extremely high in Internally Focused, both alternate identities elevated those scales moderately. A similar contrast was observed in Realistic/Sensing and Imaginative/Intuitive between primary identity and the alternate identities. Finally, while the primary identity showed an inclination to make decisions based on her emotions and current circumstances (Feeling-Guided) and a relatively strong inclination to organization and planning (Conservation-Seeking), the alternate identities showed opposite inclinations in those scales; apart from the avoidant identity in Feeling-Guided. Overall, very distinctive personality profiles were observed between identities, with the primary identity and the trauma identity showing opposite elevations in most scales.

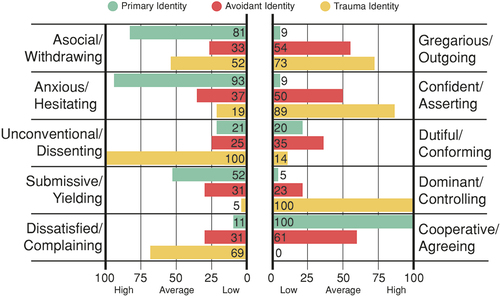

Behaving styles

Behaving styles assesses how individuals interact and develop social relationships. The identities showed visible differences (): while the primary identity showed inclination to social indifference (Asocial/Withdrawing), low interest in drawing attention from others (Gregarious/Outgoing), very high inclination to shyness and social awkwardness (Anxious/Hesitating), and low confidence (Confident/Asserting), the trauma identity showed the opposite pattern. The most extreme contrast is observed in Confident-Asserting: while the primary identity scored very low, the avoidant identity scored moderately, and the trauma identity scored very high. Furthermore, while the primary identity and the avoidant identity showed low tendency to agree with norms and a general attitude of nonconformity (Unconventional/Dissenting), the trauma identity showed an extreme inclination in favor of this style. Finally, the three identities had pronounced differences in how socially dominant, aggressive, and energetic they behave (Dominant/Controlling), e.g., while the primary identity scored very low here, the trauma identity scored extremely high. Thus, the primary identity and the trauma identity showed opposite elevations in most scales again.

Validity scales

The three personality profiles had high consistency (PI = 5; AI = 4; TI = 4; maximum possible score = 5). Additionally, while the primary identity and the avoidant identity scored mildly high in Positive Impression (PI = 6; A1 = 7), the trauma identity scored low (TI = 2). Finally, the primary identity scored in medium range for Negative Impression (PI = 6). However, both alternate identities scored very low in this scale (AI = 2; TI = 1). These observed scores suggest absence of malingering.

Additional scales: DES-II and M-FAST

In each assessment session, the patient was first asked to complete the DES-II (28 items) to assess the severity of her dissociative symptoms, and the M-FAST (25 items) to assess malingering. Her DES-II scores indicated high level of dissociation (PI = 41; AI = 47; TI = 49), and her M-FAST scores suggested absence of malingering (PI = 3; AI = 3; TI = 4; cutoff for suspecting malingering is 6).

Discussion

DID is characterized by the presence of two or more identities that exert control over a person’s behavior and self-awareness. It is believed that DID develops as a result of trauma-induced dissociations, which commonly occur during childhood (Dalenberg et al., Citation2012), although there is no consensus on this view. Some researchers have proposed that DID may also arise (totally or partially) due to social learning, media influence, and cultural expectations (Lilienfeld et al., Citation1999; Spanos, Citation1994). In addition to the ongoing debate about the nature of DID, clinicians must also contend with the issue of malingering (Brand & Chasson, Citation2015; Drob et al., Citation2009): how can they distinguish between genuine DID cases and those that are simulated?

We have presented a case study of a DID patient who displayed nine identities over the course of six months, with no indications of primary or secondary gain from the DID diagnosis. Both the treating psychiatrist and clinical psychologist agreed on this assessment. To further evaluate the patient’s case, three of her identities were assessed using the MIPS: her primary identity (PI), a trauma identity (TI), and an avoidant identity (AI). Notably, the three profiles displayed distinct differences, with the most significant differences observed between the primary identity and the trauma identity profiles. Additionally, all three profiles scored high in consistency and moderate to low in Positive Impression and Negative Impression scales, indicating that the profiles were technically valid for interpretation.

Interestingly, the primary identity and the trauma identity displayed markedly different, and sometimes even opposing, personality styles. This observation suggests that the two identities may have developed divergent adaptive strategies.

Our case study makes a twofold contribution. Firstly, it suggests that personality inventories that assess personality styles, rather than psychopathological traits (e.g., MMPI-2), may be useful in evaluating response consistency and positive/negative impression associated with each identity. Arguably, high consistency and moderate-to-low inclination to give a positive or negative impression should be expected between DID identities in genuine patients. Secondly, profiling DID identities can help clinicians understand each identity’s adaptation style, providing important insights about coping strategies that DID patients in their primary identity may need to develop. For example, our study found many areas in which the primary identity and trauma identity elevated opposite scales, indicating a possible compensation effect of the latter over the former. Arguably, trauma identities may develop in opposition to primary identities to bring new coping strategies (Kluft, Citation1988, 1991; Kluft & Fine, Citation1993; Ozturk & Sar, Citation2016). Oftentimes, our patient’s trauma identities viewed the primary identity as useless and shy, emphasizing the contrast in adaptation. Future studies could use personality style inventories that go beyond psychopathological traits to enhance malingering evaluations and complement psychotherapeutic assessments.

In conclusion, DID involves multiple identities, potentially due to trauma or cultural factors. Clinicians face challenges in distinguishing genuine cases from malingering. Our case study found distinct personality styles in different identities, suggesting the use of personality inventories to evaluate response consistency and coping strategies of different identities.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

All data underlying the results are available as part of the article and no additional source data are required.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Allen, J., & Coyne, L. (1995). Dissociation and vulnerability to psychotic experience. The dissociative experiences scale and the MMPI-2. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 183, 615–622. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005053-199510000-00001

- Allen, J. J., & Movius, H. L. (2000). The objective assessment of amnesia in dissociative identity disorder using event-related potentials. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 38, 21–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0167-8760(00)00128-8

- American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders DSM-IV. (4th ed).

- American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental Disorders, text revision. (4th ed).

- Aparicio García, M., & Sánchez-López, M. (1999). Los estilos de personalidad: Su medida a través del inventario Millon de estilos de personalidad. Annals of Psychology, 15, 191–211. Article recovered from: https://revistas.um.es/analesps/article/view/30071

- Armstrong, J. (1999). False memories and true lies: The psychology of a recanter. The Journal of Psychiatry & Law, 27, 519–547. https://doi.org/10.1177/009318539902700307

- Blihar, D., Delgado, E., Buryak, M., Gonzalez, M., & Waechter, R. (2020). A systematic review of the neuroanatomy of dissociative identity disorder. European Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 4, 100148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejtd.2020.100148

- Brand, B., Armstrong, J., & Loewenstein, R. (2006). Psychological assessment of patients with dissociative identity disorder. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 29, 145–168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psc.2005.10.014

- Brand, B., & Chasson, G. (2015). Distinguishing simulated from genuine dissociative identity disorder on the MMPI-2. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, & Policy, 7, 93–101. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035181

- Brand, B., Chasson, G., Palermo, C., Donato, F., Rhodes, K., & Voorches, E. (2016). MMPI-2 item endorsements in dissociative identity disorder vs. Simulators. The Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law, 44, 63–72.

- Brand, B., McNary, S., Loewenstein, R., Kolos, A., & Barr, S. (2006). Assessment of genuine and simulated dissociative identity disorder on the structured interview of reported symptoms. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 7, 63–85. https://doi.org/10.1300/J229v07n01_06

- Brand, B., Webermann, A., Snyder, B., & Kaliush, P. (2019). Detecting clinical and simulated dissociative identity disorder with the test of memory malingering. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, & Policy, 11, 513–520. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000405

- Brown, L., & Leigh, J. (1986). Adaptive behavior inventory. PRO-ED. https://marketplace.unl.edu/buros/adaptive-behavior-inventory.html

- Brown, D., & Scheflin, A. (1999). Factitious disorders and trauma-related diagnoses. The Journal of Psychiatry & Law, 27, 373–422. https://doi.org/10.1177/009318539902700303

- Bryant, R. A. (1995). Autobiographical memory across personalities in dissociative identity disorder: A case report. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 104, 625–631. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.104.4.625

- Buck, J. N. (1977). (H-T-P) house-tree-person projective drawing technique. Western Psychological Services. https://www.wpspublish.com/h-t-p-house-tree-person-projective-drawing-technique

- Carlson, E. B., & Putnam, F. W. (1993). An update on the dissociative experience scale. Dissociation, 6, 16–27.

- Chalavi, S., Vissia, E. M., Giesen, M. E., Nijenhuis, E. R. S., Draijer, N., Barker, G. J., Veltman, D. J., & Reinders, A. A. T. S. (2015). Similar cortical but not subcortical gray matter abnormalities in women with posttraumatic stress disorder with versus without dissociative identity disorder. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging, 231, Article 3. 308–319. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pscychresns.2015.01.014

- Chalavi, S., Vissia, E. M., Giesen, M. E., Nijenhuis, E. R. S., Draijer, N., Cole, J. H., Dazzan, P., Pariante, C. M., Madsen, S. K., Rajagopalan, P., Thompson, P. M., Toga, A. W., Veltman, D. J., & Reinders, A. A. T. S. (2015). Abnormal hippocampal morphology in dissociative identity disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder correlates with childhood trauma and dissociative symptoms. Human Brain Mapping, 36, Article 5. 1692–1704. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.22730

- Cleveland, J., Korman, B., & Gold, S. (2015). Are hypnosis and dissociation related? New evidence for a connection. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 63, 198–214. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207144.2015.1002691

- Coons, P., Bowman, E., & Milstein, V. (1988). Multiple personality disorder. A clinical investigation of 50 cases. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 176, 519–527. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005053-198809000-00001

- Coons, P., & Milstein, V. (1994). Factitious or malingered multiple personality disorder: Eleven cases. Dissociation: Progress in the Dissociative Disorders, 7, 81–85.

- Dalenberg, C. J., Brand, B. L., Gleaves, D. H., Dorahy, M. J., Loewenstein, R. J., Cardeña, E., Frewen, P. A., Carlson, E. B., & Spiegel, D. (2012). Evaluation of the evidence for the trauma and fantasy models of dissociation. Psychological Bulletin, 138, 550–588. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027447

- Deeley, Q. (2016). Hypnosis as therapy for functional neurologic disorders. In M. Hallett, J. Stone, & A. Carson (Eds.), Handbook of clinical neurology (pp. 585–595). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-801772-2.00047-3.

- Dimitrova, L. I., Dean, S. L., Schlumpf, Y. R., Vissia, E. M., Nijenhuis, E. R. S., Chatzi, V., Jäncke, L., Veltman, D. J., Chalavi, S., & Reinders, A. A. T. S. (2023). A neurostructural biomarker of dissociative amnesia: A hippocampal study in dissociative identity disorder. Psychological Medicine, 53, 805–813. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291721002154

- Drob, S., Meehan, K., & Waxman, S. (2009). Clinical and conceptual problems in the attribution of malingering in forensic evaluations. The Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law, 37, 98–106.

- Ehling, T., Nijenhuis, E., & Krikke, A. (2007). Volume of discrete brain structures in complex dissociative disorders: Preliminary findings. In E. de Kloet, M. Oitzl, & E. Vermetten (Eds.), Progress in brain research (pp. 307–310). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0079-6123(07)67029-0.

- Elhai, J., Gold, S., Mateus, L., & Astaphan, T. (2001). Scale 8 elevations on the MMPI-2 among women survivors of childhood sexual abuse: Evaluating posttraumatic stress, depression, and dissociation as predictors. Journal of Family Violence, 16, 47–57. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026576425986

- Fine, C. (2012). Cognitive behavioral hypnotherapy for dissociative disorders. American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis, 54, 331–352. https://doi.org/10.1080/00029157.2012.656856

- Gleaves, D. (1996). The sociocognitive model of dissociative identity disorder: A reexamination of the evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 120, 42–59. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.120.1.42

- Gušić, S., Cardeña, E., Bengtsson, H., & Søndergaard, H. (2016). Adolescents’ dissociative experiences: The moderating role of type of trauma and attachment style. Journal of Child and Adolescent Trauma, 9, 341–351. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40653-016-0107-y

- Huntjens, R. J. C., Peters, M. L., Woertman, L., van der Hart, O., & Postma, A. (2007). Memory transfer for emotionally valenced words between identities in dissociative identity disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 45, 775–789. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2006.07.001

- Huntjens, R. J. C., Postma, A., Hamaker, E. L., Woertman, L., Van Der Hart, O., & Peters, M. (2002). Perceptual and conceptual priming in patients with dissociative identity disorder. Memory & Cognition, 30, 1033–1043. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03194321

- Huntjens, R. J. C., Postma, A., Peters, M. L., Woertman, L., & van der Hart, O. (2003). Interidentity amnesia for neutral, episodic information in dissociative identity disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 112, 290–297. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843x.112.2.290

- Huntjens, R. J. C., Postma, A., Woertman, L., van der Hart, O., & Peters, M. L. (2005). Procedural memory in dissociative identity disorder: When can inter-identity amnesia be truly established? Consciousness and Cognition, 14, 377–389. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2004.10.001

- Huntjens, R. J. C., Verschuere, B., McNally, R. J., & Scott, J. G. (2012). Inter-identity autobiographical amnesia in patients with dissociative identity disorder. Public Library of Science ONE, 7, e40580. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0040580

- Huntjens, R. J. C., Wessel, I., Hermans, D., & van Minnen, A. (2014). Autobiographical memory specificity in dissociative identity disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 123, 419–428. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036624

- Huntjens, R. J. C., Wessel, I., Ostafin, B. D., Boelen, P. A., Behrens, F., & van Minnen, A. (2016). Trauma-related self-defining memories and future goals in dissociative identity disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 87, 216–224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2016.10.002

- Johnson, J., Cohen, P., Kasen, S., & Brook, J. (2006). Dissociative disorders among adults in the community, impaired functioning, and axis I and II comorbidity. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 40, 131–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2005.03.003

- Kennerley, H. (1996). Cognitive therapy of dissociative symptoms associated with trauma. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 35, 325–340. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8260.1996.tb01188.x

- Kluft, R. (1988). The phenomenology and treatment of extremely complex multiple personality disorder. Dissociation: Progress in the Dissociative Disorders, 1(4), 47–58.

- Kluft, R., & Fine, C. (1993). Clinical perspectives on multiple personality disorder. American Psychiatric Association Publishing.

- Labott, S., & Wallach, H. (2002). Malingering dissociative identity disorder: Objective and projective assessment. Psychological Reports, 90, 525–538. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.2002.90.2.525

- Lebois, L. A. M., Harnett, N. G., van Rooij, S. J. H., Ely, T. D., Jovanovic, T., Bruce, S. E., House, S. L., Ravichandran, C., Dumornay, N. M., Finegold, K. E., Hill, S. B., Merker, J. B., Phillips, K. A., Beaudoin, F. L., An, X., Neylan, T. C., Clifford, G. D., Linnstaedt, S. D., Germine, L. T. … Ressler, K. J. (2022). Persistent dissociation and its neural correlates in predicting outcomes after trauma exposure. American Journal of Psychiatry, 179, 661–672. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.21090911

- Lebois, L. A. M., Kumar, P., Palermo, C. A., Lambros, A. M., O’Connor, L., Wolff, J. D., Baker, J. T., Gruber, S. A., Lewis-Schroeder, N., Ressler, K. J., Robinson, M. A., Winternitz, S., Nickerson, L. D., & Kaufman, M. L. (2022). Deconstructing dissociation: A triple network model of trauma-related dissociation and its subtypes. Neuropsychopharmacology Reviews, 47, Article 13. 2261–2270. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41386-022-01468-1

- Lebois, L. A. M., Li, M., Baker, J. T., Wolff, J. D., Wang, D., Lambros, A. M., Grinspoon, E., Winternitz, S., Ren, J., Gönenç, A., Gruber, S. A., Ressler, K. J., Liu, H., & Kaufman, M. L. (2021). Large-scale functional brain network architecture changes associated with trauma-related dissociation. American Journal of Psychiatry, 178, 165–173. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2020.19060647

- Lewis, D., Yeager, C., Swica, Y., Pincus, J., & Lewis, M. (1997). Objective documentation of child abuse and dissociation in 12 murderers with dissociative identity disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 154, 1703–1710. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.154.12.1703

- Lilienfeld, S., Lynn, S., Kirsch, I., Chaves, J., Sarbin, T., Ganaway, G., & Powell, R. (1999). Dissociative identity disorder and the sociocognitive model: Recalling the lessons of the past. Psychological Bulletin, 125, 507–523. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.125.5.507

- Loewenstein, R. (2020). Firebug! Dissociative identity disorder? malingering? Or … ? An intensive case study of an arsonist. Psychological Injury and Law, 13, 187–224. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12207-020-09377-8

- Marsh, R. J., Dorahy, M. J., Verschuere, B., Butler, C., Middleton, W., & Huntjens, R. J. C. (2018). Transfer of episodic self-referential memory across amnesic identities in dissociative identity disorder using the autobiographical implicit association test. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 127, 751–757. https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000377

- Miller, H. (2001). The miller-forensic assessment of symptoms test (M-FAST): Professional manual. Psychological Assessment Resources. https://www.parinc.com/Products/Pkey/230

- Miller, H. A. (2005). The miller-forensic assessment of symptoms test (M-Fast): Test generalizability and utility across race, literacy, and clinical opinion. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 32, 591–611. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854805278805

- Miller, T. J., McGlashan, T. H., Rosen, J. L., Cadenhead, K., Ventura, J., McFarlane, W., Perkins, D. O., Pearlson, G. D., & Woods, S. W. (2003). Prodromal assessment with the structured interview for prodromal syndromes and the scale of prodromal symptoms: Predictive validity, interrater reliability, and training to reliability. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 29, 703–715. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007040

- Millon, T. (1995). Disorders of personality: DSM-IV and beyond. (2nd ed.). Wiley.

- Millon, T. (2003). Millon index of personality styles revised. Pearson.

- Murray, H. A. (1943). Thematic apperception test. Harvard University Press.

- Nijenhuis, E. R. S., & van der Hart, O. (2011). Dissociation in trauma: A new definition and comparison with previous formulations. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 12, 416–445. https://doi.org/10.1080/15299732.2011.570592

- Nissen, M. J., Ross, J. L., Willingham, D. B., Mackenzie, T. B., & Schacter, D. L. (1988). Memory and awareness in a patient with multiple personality disorder. Brain and Cognition, 8, 117–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/0278-2626(88)90043-7

- Ozturk, E., & Sar, V. (2016). Formation and functions of alter personalities in dissociative identity disorder: A theoretical and clinical elaboration. Journal of Psychology & Clinical Psychiatry, 6(6). https://doi.org/10.15406/jpcpy.2016.06.00385

- Pietkiewicz, I. J., Bańbura-Nowak, A., Tomalski, R., & Boon, S. (2021). Revisiting false-positive and imitated dissociative identity disorder. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.637929

- Putnam, F. W., Guroff, J. J., Silberman, E. K., Barban, L., & Post, R. M. (1986). The clinical phenomenology of multiple personality disorder: Review of 100 recent cases. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 47, 285–293.

- Reinders, A. A. T. S., Dimitrova, L. I., Schlumpf, Y. R., Vissia, E. M., Nijenhuis, E. R. S., Jäncke, L., Chalavi, S., & Veltman, D. J. (2022). Normal amygdala morphology in dissociative identity disorder. British Journal of Psychiatry Open, 8, e70. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2022.36

- Reinders, A. A. T. S., Willemsen, A. T. M., den Boer, J. A., Vos, H. P. J., Veltman, D. J., & Loewenstein, R. J. (2014). Opposite brain emotion-regulation patterns in identity states of dissociative identity disorder: A PET study and neurobiological model. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging, 223, Article 3. 236–243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pscychresns.2014.05.005

- Reinders, A. A. T. S., Willemsen, A. T. M., Vissia, E. M., Vos, H. P. J., den Boer, J. A., & Nijenhuis, E. R. S. (2016). The psychobiology of authentic and simulated dissociative personality states: The full monty. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 204, 445–457. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0000000000000522

- Reinders, A. A. T. S., Willemsen, A. T. M., Vos, H. P. J., Boer, J. A. D., Nijenhuis, E. R. S., & Laks, J. (2012). Fact or factitious? A psychobiological study of authentic and simulated dissociative identity states. Public Library of Science ONE, 7, e39279. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0039279

- Rodewald, F., Wilhelm-Göling, C., Emrich, H. M., Reddemann, L., & Gast, U. (2011). Axis-I comorbidity in female patients with dissociative identity disorder and dissociative identity disorder not otherwise specified. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 199, 122–131. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0b013e318208314e

- Rogers, R. (2010). Structured interview of reported symptoms. In The Corsini Encyclopedia of Psychology (pp. 1–2). John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470479216.corpsy0957.

- Rogers, R., Gillard, N. D., Wooley, C. N., & Ross, C. A. (2012). The detection of feigned disabilities: The effectiveness of the personality assessment inventory in a traumatized inpatient sample. Assessment, 19, 77–88. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191111422031

- Roydeva, M. I., & Reinders, A. A. T. S. (2021). Biomarkers of pathological dissociation: A systematic review. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 123, 120–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2020.11.019

- Rutter, M., Le Couteur, A., & Lord, C. (2003). Autism diagnostic interview revised (ADI-R). Western Psychological Services.

- Sar, V. (2011). Epidemiology of dissociative disorders: An overview. Epidemiology Research International, 2011, e404538. https://doi.org/10.1155/2011/404538

- Sar, V., Unal, S. N., Kiziltan, E., Kundakci, T., & Ozturk, E. (2001). HMPAO SPECT study of regional cerebral blood flow in dissociative identity disorder. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 2, 5–25. https://doi.org/10.1300/J229v02n02_02

- Sar, V., Unal, S. N., & Ozturk, E. (2007). Frontal and occipital perfusion changes in dissociative identity disorder. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging, 156, 217–223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pscychresns.2006.12.017

- Schlumpf, Y. R., Nijenhuis, E. R. S., Chalavi, S., Weder, E. V., Zimmermann, E., Luechinger, R., La Marca, R., Reinders, A. A. T. S., & Jäncke, L. (2013). Dissociative part-dependent biopsychosocial reactions to backward masked angry and neutral faces: An fMRI study of dissociative identity disorder. NeuroImage: Clinical, 3, 54–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nicl.2013.07.002

- Schlumpf, Y. R., Reinders, A. A. T. S., Nijenhuis, E. R. S., Luechinger, R., Osch van, M. J. P., Jäncke, L., & Chao, L. (2014). Dissociative part-dependent resting-state activity in dissociative identity disorder: A controlled fMRI perfusion study. Public Library of Science ONE, 9, Article 6. e98795. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0098795

- Spanos, N. P. (1994). Multiple identity enactments and multiple personality disorder: A sociocognitive perspective. Psychological Bulletin, 116, 143–165. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.116.1.143

- Spielberger, C. D. (1983). Manual for the State-Trait-Anxiety Inventory: STAI (form Y). Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

- Stadnik, R. D., Brand, B., & Savoca, A. (2013). Personality assessment inventory profile and predictors of elevations among dissociative disorder patients. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation: The Official Journal of the International Society for the Study of Dissociation (ISSD), 14, 546–561. https://doi.org/10.1080/15299732.2013.792310

- Steinberg, M. (1994). Interviewer’s guide to the structured clinical interview for DSM-IV® dissociative disorders (SCID-D). American Psychiatric Association.

- Tamar-Gurol, D., Sar, V., Karadag, F., Evren, C., & Karagoz, M. (2008). Childhood emotional abuse, dissociation, and suicidality among patients with drug dependency in Turkey. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 62, 540–547. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1819.2008.01847.x

- van der Hart, O., Bolt, H., & van der Kolk, B. A. (2005). Memory fragmentation in dissociative identity disorder. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 6, 55–70. https://doi.org/10.1300/J229v06n01_04

- Vermetten, E., Schmahl, C., Lindner, S., Loewenstein, R. J., & Bremner, J. D. (2006). Hippocampal and amygdalar volumes in dissociative identity disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 163, 630–636. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.2006.163.4.630

- Vissia, E. M., Giesen, M. E., Chalavi, S., Nijenhuis, E. R. S., Draijer, N., Brand, B. L., & Reinders, A. A. T. S. (2016). Is it trauma- or fantasy-based? Comparing dissociative identity disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, simulators, and controls. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 134, 111–128. https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.12590

- Welburn, K. R., Fraser, G. A., Jordan, S. A., Cameron, C., Webb, L. M., & Raine, D. (2003). Discriminating dissociative identity disorder from schizophrenia and feigned dissociation on psychological tests and structured interview. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 4, 109–130. https://doi.org/10.1300/J229v04n02_07

- Zanarini, M. C., Vujanovic, A. A., Parachini, E. A., Boulanger, J. L., Frankenburg, F. R., & Hennen, J. (2003). A screening measure for BPD: The McLean screening instrument for borderline personality disorder (MSI-BPD). Journal of Personality Disorders, 17, 568–573. https://doi.org/10.1521/pedi.17.6.568.25355