ABSTRACT

Every semester, the operating room (OR) ward receives students from different educational programmes. Although interprofessional knowledge is essential for OR teamwork, students have traditionally been prepared in an uniprofessional manner, with no focus on interprofessional learning outcomes. This report describes the work process of an interprofessional initiative undertaken to create a common learning resource aimed at preparing students for OR practice. With a focus on interprofessional learning, shared and profession-specific learning outcomes, which are needed to prepare for practice, were identified by an interprofessional faculty. To avoid timetabling and geographic barriers, learning outcomes and constructed learning activities were packaged into an e-module and delivered on-line as an adjunct to existing lectures and workshops. A survey was administered to 4th year medical (n = 42) and 1st year OR nurse students (n = 4) to evaluate their perceptions of the e-module. We found that most learning outcomes from the different syllabuses were common for all professions. The overall response rate of the survey was 59% (27 of 46 students). Eighteen of the 27 responding students had used the learning resource, of which 15 students considered it to be of ‘high’ or ‘very high’ value. In summary, this interprofessional initiative resulted in a new common learning resource for the OR, which was used and perceived valuable by a majority of the students. The learning outcomes needed to prepare students from different educational programmes for OR practice are, to a great extent, generic and interprofessional and we thus argue that the interprofessional nature of the faculty was essential for the success of the initiative.

Introduction

Every semester, the operating room (OR) ward receives students from several different educational programmes (nurses, OR nurses, anaesthetic nurses and medical students). The OR is very different from other hospital wards as its context requires a considerable amount of specific knowledge, e.g. about aseptic techniques, in order to ensure patient safety. Furthermore, surgeries performed in the OR demand a unique kind of teamwork between several different professions, one that is frequently executed while treating severely ill patients. Most students have no prior OR experience, and it is common for them to experience this learning environment as stressful, which may have a negative impact on their learning (Lyon, Citation2003). Accordingly, preparedness for practice has been shown to be an important factor for student learning in this milieu (Fernando et al., Citation2007a; Lyon, Citation2003).

Students, which have been asked about their experience of OR practice, have emphasised that the training of specific skills needed for the OR, such as scrubbing, and knowledge about theatre staff and their responsibilities should be included in the preparation (Fernando et al., Citation2007b). How to best acquire this knowledge and skills, however, has been poorly studied. The fact that surgery requires a high level of teamwork speaks per se to an interprofessional learning approach. Nevertheless, due to traditions and difficult logistics, student categories have usually been prepared in an uniprofessional manner, and learning activities have not related to interprofessional learning outcomes.

E-learning, defined as software-based resources delivered by an electronic device or computer and distributed online, is one way to overcome the timetabling and geographic barriers (Maertens et al., Citation2016), which frequently hinder interprofessional education. The fact that e-learning holds the possibility to incorporate multimedia makes it excellent for learning skills and offers potential for ‘just-in-time learning’ along with clinical experiences (Ruiz, Mintzer, & Leipzig, Citation2006). The aim of this study was to describe the work process of an interprofessional initiative taken to create a common learning resource, an e-module, for all students attending the OR.

Background

Work process

Four faculty members (adjunct or senior lecturers) from four education programmes (nurses, OR nurses, anaesthetic nurses and medical programme) within two different departments at Karolinska Institute came together to create a common learning resource for the OR. All faculty members had prior experience of interprofessional projects; they were all, to some extent, responsible for the OR practice but did not work together before the initiative. Initially the faculty made an inventory of what was currently done in order to prepare the students for their OR practice and concluded that all programmes had different scheduled lectures or workshops with this precise intention. However, due to time constraints, these learning activities needed to be kept to a minimum, and students had difficulty achieving the learning outcomes. Moreover, interprofessional learning outcomes were non-existent, and there was a need for supervised repetition, which was not possible with the available resources. Thus, the decision was made to create a new learning resource, as an adjunct to the existing lectures and workshops, with an interprofessional focus that would be delivered through an e-learning module. The learning resource targeted students undergoing clinical practice at Södersjukhuset, a 650-bed university hospital serving a population of 650,000 inhabitants. The OR ward performs orthopaedics, urology and general surgery.

The interprofessional faculty identified and scrutinised learning outcomes from the different course syllabi and national guidelines in order to prepare students for OR practice. For each learning outcome, faculty members chose suitable learning activities such as movies or recorded audio lectures. To provide feedback on the knowledge acquired, the faculty strived to provide formal assessments within the learning resource after each learning activity. Measures were taken to remain focussed on interprofessional knowledge in learning outcomes, activities and assessments.

The audio recorded lectures were produced in PowerPoint® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA) and Screencast-o-matic® (UserVoice, San Francisco, USA), and the movies were produced using a camcorder with a microphone. The learning material was packaged into an e-module using Articulate Storyline® (Articulate Global, New York, USA). The finalised e-module was delivered through the students’ ordinary learning management system (LMS) Ping Pong® (Ping Pong AB, Stockholm, Sweden), which could be accessed on computers, tablets and smart phones, both inside and outside the hospital.

The learning resource

The complete learning resource was based on seven learning outcomes, including knowledge and skills (). It was concluded that most learning outcomes were generic, but that selected learning outcomes were directed to a specific student category exclusively (). Each learning outcome was connected to a knowledge- or skill-based learning activity, which was either a movie or an audio-recorded lecture. One example of a knowledge-based activity with an interprofessional learning outcome was ‘Professions working in the OR’, which aimed to deepen the students’ knowledge of the various responsibilities of the OR team. ‘Gowning procedure in the OR’ is an example of a skill-based activity whereby the students were given an interprofessional perspective of a procedure.

Table 1. Learning outcome, activities and examination.

Most learning activities were followed by a FORMATIVE assessment in order to give immediate feedback to students. Some learning outcomes, however, were not considered suitable for assessment within the learning resource and were instead assessed in connection with the clinical practice, e.g. sterile glowing. Assessments within the learning resource consisted of multiple choice or matching-pair questions. Feedback consisting of a short description of the background relating to the right answer was also given after the assessments.

Methods

The learning resource was piloted on 4th year medical students, 3rd year nursing students and 1st year OR nurse students in the spring term of 2016. The students were introduced to the learning resource during the mandatory introduction workshops in the OR ward. However, the use of the learning resource was voluntary, and there was no scheduled time to complete the learning activities. Students could choose to access the different activities alone or together with other students.

A post-intervention research design was used to study student perspectives of the learning resource, how students had used it, and reasons for not using it. Data were obtained through a paper survey containing eight items with closed and open-ended questions. A 4-point Likert scale was used to rate student agreement with the statements in closed items. Due to logistics, answers were obtained from the medical (n = 42) and OR nurse students (n = 4) only. The survey was delivered to the students directly after their final exams, participation was voluntary, answers were collected anonymously and consent was implied with the return of the survey. Descriptive statistics were used to calculate frequencies (percentages) for each item and inductive thematic analysis was used for open-ended questions. Ethical permission was not deemed necessary since the Karolinska Institutet regarded the survey as a teaching audit.

Results

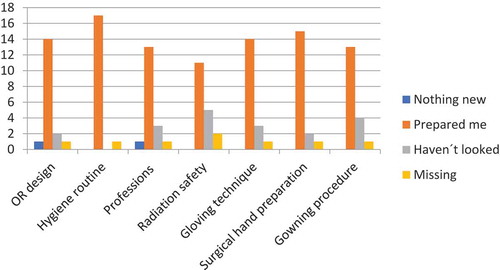

The response rate of the survey was 59% (27 of 46). Eighteen of 27 responding students answered that they had used the learning resource. Reasons for not using the learning resource could be divided into “Time constraints”, “Too little information of the learning resource existence” and “Technical problems”. Of the 18 students who had used the learning resource 15 considered it to be of ‘high’ or ‘very high’ value. When students were asked whether “The learning resource covered the learning material needed to be prepared for OR practise?” 50% strongly agreed, 33% agreed and 17% partly agreed. The students’ reviews of the different learning activities are shown in . No negative comments regarding the interprofessional (IPE) nature of the e-module were recorded.

Discussion

This report described the work process of an interprofessional initiative, which successfully resulted in a common learning resource for healthcare students in the OR. To our knowledge, the learning resource, which was delivered on-line and aimed to prepare students for OR practice, is the first of its kind. The students’ satisfaction with the content of the learning resource was high and they found it to be of high value when preparing for OR practice.

Key factors for success in implementing interprofessional education have previously been described by Hall and Zierler (Citation2015). The work process, described in this paper, to a large extent follows the recommendations in Hall and Zierler (Citation2015), and we share their experiences. Thus, we claim that the interprofessional nature of our faculty, the faculty members’ experience of prior IPE projects and the informal communication within the faculty were factors that all facilitated the work process. The authentic need for an additional learning resource, the apparent connection of the learning resource to students’ practice and the clear objective of the initiative, we argue, were likewise reasons for success.

The strengths of the learning resource can, to a high extent, be connected to its e-learning format, including its accessibility, control over learning sequence, learning pace and the possibility of endless repetition (Leong et al., Citation2015; Weber, Constantinescu, Woermann, Schmitz, & Schnabel, Citation2016). We perceived that these inherent qualities of e–learning, known to enhance learning in general, were even more valuable when designing interprofessional learning resources.

First and foremost, the possibility of asynchronous learning was essential, since the learning resource was targeted at several healthcare student categories, from different academies, arriving at different periods during the semester. The opportunity for students to tailor their learning was also very important, given that we address such a broad spectrum of students (Leong et al., Citation2015; Ruiz et al., Citation2006). Accessibility through different devices promotes ‘just-in-time learning’, and repetition in connection with clinical experiences is ideal for clerkship. This is known to have a major impact on learning (Weber et al., Citation2016), and it may also decrease the stress many students experience when entering the OR (Lyon, Citation2003).

The capacity of the learning resource to incorporate multimedia for learning activities suited the learning outcomes very well. The ability to see and hear the learning material, and not just to read it, is known to be more effective for learning, especially when preparing students for practical skills (Fernandoet al., Citation2007b; Weber et al., Citation2016). In this way, the optimal content and number of learning activities in the learning resource can be discussed. The fact that the students had the opportunity to choose the learning activities, that they were offered to support preparedness and were not mandatory made the decision less crucial. The freedom to choose also contributed to the decision to include more learning activities in the learning resource, even those that were profession-specific. The evaluation subsequently revealed that the students did choose, i.e. they did not go through all the learning activities.

One key shortfall with this learning resource is that it is not truly interprofessional. Although it stimulates learning about the different professions working in the OR and their responsibilities, and students may complete the learning activities together, it does not actively support students to learn from and with each other. To achieve this, a learning resource needs to enable interaction between students. This should be a natural development goal since interactivity within the module would also enhance learning (Ruiz et al., Citation2006). However, interactivity would demand a more complex design of the e-module and probably a greater level of technical expertise during development. Technical difficulties and lack of funding often serve as a hindrance when creating new learning resources, and we believe that the relative simplicity of the module, as well as the low costs, contributed to our success. We thus call on others to start similar projects. Although we only have the perspectives of medical students and a few OR nurse students, the results are promising. Ongoing studies will explore the perspectives of all student categories as well as the effect on their learning.

In relation to study limitations, we only obtained survey data from medical and OR nurse students, and the OR nurse students were only four during the study period. Different student categories might have different opinions on the learning resource but our limited data do not permit us to analyse this. It also needs to be mentioned that the sample size of our study was small, there was a relatively low response rate (59%), data was self-reported and the survey was a non-validated tool.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the article.

References

- Fernando, N., McAdam, T., Cleland, J., Yule, S., McKenzie, H., & Youngson, G. (2007a). How can we prepare medical students for theatre-based learning? Medical Education, 41(10), 968–974. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2923.2007.02839.x

- Fernando, N., McAdam, T., Youngson, G., McKenzie, H., Cleland, J., & Yule, S. (2007b). Undergraduate medical students’ perceptions and expectations of theatre-based learning: How can we improve the student learning experience? Surgeon, 5(5), 271–274. doi:10.1016/S1479-666X(07)80024-2

- Fernando, N., McAdam, T., Youngson, G., McKenzie, H., Cleland, J., & Yule, S. (2007c). Undergraduate medical students’ perceptions and expectations of theatre-based learning: How can we improve the student learning experience? Surgeon, 5(5), 271–274. doi:10.1016/S1479-666X(07)80024-2

- Hall, L. W., & Zierler, B. K. (2015). Interprofessional education and practice guide No. 1: Developing faculty to effectively facilitate interprofessional education. Journal Interprofessional Care, 29(1), 3–7. doi:10.3109/13561820.2014.937483

- Leong, C., Louizos, C., Currie, C., Glassford, L., Davies, N. M., Brothwell, D., & Renaud, R. (2015). Student perspectives of an online module for teaching physical assessment skills for dentistry, dental hygiene, and pharmacy students. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 29(4), 383–385. doi:10.3109/13561820.2014.977380

- Lyon, P. M. (2003). Making the most of learning in the operating theatre: Student strategies and curricular initiatives. Medical Education, 37(8), 680–688. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2923.2003.01583.x

- Maertens, H., Madani, A., Landry, T., Vermassen, F., Van Herzeele, I., & Aggarwal, R. (2016). Systematic review of e-learning for surgical training. British Journal of Surgery, 103(11), 1428–1437. doi:10.1002/bjs.10236

- Ruiz, J. G., Mintzer, M. J., & Leipzig, R. M. (2006). The impact of E-learning in medical education. Academic Medicine, 81(3), 207–212. doi:10.1097/00001888-200603000-00002

- Weber, U., Constantinescu, M. A., Woermann, U., Schmitz, F., & Schnabel, K. (2016). Video-based instructions for surgical hand disinfection as a replacement for conventional tuition? A randomised, blind comparative study. GMS Journal for Medical Education, 33(4). doi:10.3205/zma001056