ABSTRACT

Collaboration among health care providers is intended to dissolve boundaries between the sectors of health care systems. The implementation of adequate augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) care of people without natural speech depends highly on collaboration among multiple stakeholders such as speech and language pathologists, teachers, or physicians. This paper examines existing barriers to and facilitators of collaboration from a stakeholder perspective. Five heterogeneous focus group interviews were conducted with N= 32 stakeholders including speech and language pathologists, AAC consultants, teachers, employees of sheltered workshops, parents, and relatives of AAC users, and other educational professionals (e.g., employees of homes for persons with disabilities) at three AAC counseling centers in Germany. Interview data were analyzed by structured qualitative content analysis. The results show very different experiences of collaboration in AAC care. Factors were identified that can have both positive and negative effects on the collaboration between all stakeholders (e.g., openness toward AAC, knowledge about AAC, communication between stakeholders). In addition, stakeholder-specific influencing factors, such as working conditions or commitment to AAC implementation, were identified. The results also reveal that these factors may have an impact on the quality of AAC care. Overall, the results indicate that good collaboration can contribute to better AAC care and that adequate conditions such as personnel, and time-related resources, or financial conditions need to be established to facilitate collaboration.

Introduction

Collaboration in healthcare has internationally been identified as a major challenge to healthcare improvement. In the report Framework for Action on Interprofessional Education and Collaborative Practice, the World Health Organization (World Health Organization (WHO), Citation2010) emphasized the relevance of interprofessional collaboration. The Institute of Medicine (Citation2001) declared that achieving effective coordination of patient care is a major challenge for healthcare. According to these reports and because healthcare is becoming increasingly complex, fragmented sectors need to work together (Greenhalgh, Citation2008; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine, Citation2015; WHO, Citation2010).

In this paper, the term collaboration is defined as a “[…] partnership, often between people from diverse backgrounds, who work together to solve problems or provide services,” as suggested by Reeves et al. (Citation2010, p. 6). Collaboration between various stakeholders in healthcare is intended to dissolve boundaries between the different sectors of the healthcare system (e.g., inpatient, outpatient, rehabilitation) and should provide more accessible and holistic care (Amelung et al., Citation2012). In addition, interruptions in healthcare processes and duplicate treatment can be avoided, and innovations can be implemented more easily. Thus, special forms of healthcare, such as integrated care or health networks, have been developed in order to enable collaborative healthcare (D’Amour et al., Citation2008; Lalani et al., Citation2020; Loewenbrück et al., Citation2020). In the healthcare of people with complex chronic conditions or complex care needs, multiple stakeholders (e.g., physicians, therapists, nursing staff, caregivers, payers) from different sectors are usually involved. To guarantee adequate healthcare, it is important for these stakeholders to collaborate and communicate with each other across sector boundaries (Amelung et al., Citation2012; Hwang et al., Citation2009; Tsakitzidis et al., Citation2016). Schoen et al. (Citation2011) examined the healthcare of people with complex care needs in 11 countries and found that healthcare was often inadequately coordinated. Therefore, in this paper we examined the collaboration between stakeholders in augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) care, and the respective barriers, and facilitators in Germany.

Background

Augmentative and alternative communication

AAC is a field focusing on people without natural speech that includes the use of unaided AAC systems (e.g., gestures) and aided AAC systems (e.g., communication boards, devices with voice output; Baxter et al., Citation2012; Sigafoos & Drasgow, Citation2001; Wilkinson & Madel, Citation2019). People who require AAC usually have chronic conditions and/or complex care needs (Beukelman et al., Citation2007; Light & McNaughton, Citation2012). Various congenital conditions (e.g., autism, cerebral palsy) or acquired disabilities (e.g., amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, stroke) lead to complex communication needs. The group of people who require AAC is very heterogeneous in age and disabilities (Beukelman & Mirenda, Citation2013; Creer et al., Citation2016; Harding et al., Citation2011). Although AAC care is very specific, it has similarities with other forms of care. Similarities can be found with geriatric care, in which care is provided for a vulnerable patient group with complex chronic conditions as well. As in AAC care, geriatric patients (e.g., patients with dementia) are often cared for at home by informal caregivers and also rely on the support of various stakeholders such as therapists, physicians, or other health and social care workers (Jirau-Rosaly et al., Citation2020; Tsakitzidis et al., Citation2016).

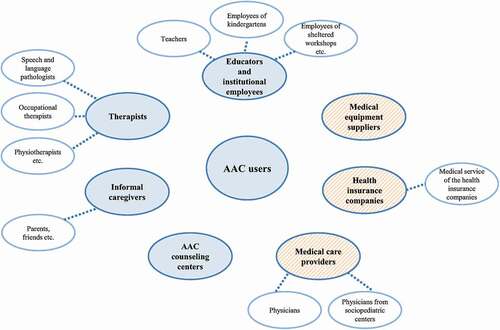

Potential stakeholders in AAC networks

Collaboration in AAC care as well as the care processes themselves vary greatly between countries and even within countries due to the involvement of many stakeholders of different levels of expertise, and varying role definitions, and degrees of standardization (Binger et al., Citation2012; Subihi, Citation2013; Waller, Citation2013). illustrates the potential stakeholders in AAC networks within the German health care system. This figure is based on experiences gained by the research team shadowing AAC counseling centers and on exchanges with practitioners working in AAC care.

Figure 1. Potential active (unicolored fields) and passive (striped fields) stakeholders in an AAC care network

In the German setting, stakeholders can be roughly divided into active and passive ones (see ). Active stakeholders are those actively involved in the use of the AAC system together with the AAC user, such as educators and institutional employees (e.g., teachers, employees of kindergartens), therapists (e.g., speech and language pathologists, physiotherapists), informal caregivers (e.g., parents, friends), and AAC counseling centers. In Germany, AAC counseling centers offer independent counseling on AAC systems and their use. Because counseling centers are not formally required by regulation, few centers exist in Germany. Although some therapists in Germany are also employed in educational and employment institutions, we consider this professional group as an independent stakeholder because they mainly work independently or in private practices. Passive stakeholders are mainly responsible for the procurement of the AAC systems, but do not use the AAC system together with the AAC user. In Germany, AAC systems must be prescribed by physicians and approved by a health insurance company. In some cases, the health insurance company’s service assesses the person’s need for an aided AAC system. Finally, the medical equipment supplier delivers the AAC system and offers technical instruction. The entire network consists of different subnetworks that differ between AAC users, depending on which stakeholders are involved (Alant et al., Citation2013; Binger et al., Citation2012). For example, there is often a subnetwork between speech and language pathologists and teachers as it is essential that teachers use AAC appropriately in the school setting (Binger et al., Citation2012).

The relevance of collaboration in AAC

The implementation and success of AAC care are highly dependent on stakeholder collaboration. The degree of collaboration has been shown to positively influence outcomes such as the adequacy of the AAC system or the use of the AAC system (Chung & Stoner, Citation2016; Murray et al., Citation2019; Stoner et al., Citation2010). The implementation of interventions such as team meetings including knowledge exchange on AAC use, collaborative development, and use of unified plans of support (e.g., plan of communication support) seem to have a positive impact on stakeholder collaboration and communication skills of AAC users (Alant et al., Citation2013; Hunt et al., Citation2002; Snodgrass & Meadan, Citation2018). The American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (Citation2002) emphasized that AAC care is multidisciplinary and supports the relevance of collaboration between stakeholders involved in AAC care. All persons who use the AAC system with the AAC user in everyday life should be included in a team (American Speech-Language-Hearing Association, Citation2002; Giel & Liehs, Citation2016; Sachse, Citation2010). Although the above-mentioned researchers have investigated the impact of collaboration on AAC care, they almost exclusively dealt with collaboration in the school setting as the meta-synthesis done by Chung and Stoner (Citation2016) illustrates. The meta-synthesis included 10 qualitative studies focused on the collaboration of stakeholders involved in public school AAC care in the United States. One goal of the meta-synthesis was to identify the different perspectives of the AAC team members in public schools on supporting students who use AAC. A research gap is evident regarding the entire AAC care network with all potential stakeholders and regarding all age groups of people who rely on AAC.

Aim and research questions

We aimed to examine the collaboration among all stakeholders involved in AAC care in Germany, including all groups of AAC users (adults and children) with all kinds of disabilities. As a result, the following research question was identified: What are barriers to and facilitators of collaboration in AAC care from a stakeholder perspective?

Methods

Research design

The data were collected within the research project New Service Delivery Model for Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC) Devices and Intervention. Within the project a complex intervention is being tested in a mixed-methods study design in three AAC counseling centers. The intervention and complete study design are explained in detail in the study protocol (Zinkevich et al., Citation2019). To assess the status quo of AAC care in Germany and to derive deficits and needs, focus group interviews were conducted prior to the intervention. In this paper, data from the semi-structured focus group interviews are analyzed with regard to the research question on collaboration. Because qualitative focus groups foster interaction between participants, this method was regarded as particularly useful when examining experiences of collaboration between stakeholders in the AAC network (Kitzinger, Citation2006; Kitzinger & Barbour, Citation1999; Krueger & Casey, Citation2009).

Participant selection and recruitment

Only active stakeholders were recruited for the focus group interviews, as they are in direct contact with AAC users and are an integral part of the individual AAC network. Therefore, we assumed that they have the best insight into the entire care process. The recruitment for all focus group interviews was carried out by purposeful sampling (Patton, Citation2002) to cover the perspectives of different groups of active stakeholders. Participants included therapists (e.g., speech and language pathologists), consultants at AAC counseling centers, educators and institutional employees (e.g., teachers, employees of sheltered workshops), informal caregivers (e.g., parents of AAC users), and other educational professionals (e.g., employees of homes for persons with disabilities). The AAC counseling centers helped recruit participants from their network. All participants were informed about the interviews in advance in writing. A total of five focus group interviews were conducted, in which 32 active stakeholders were interviewed. The heterogeneous composition of the focus group interviews is explained by the explorative character of the focus group interviews. Heterogeneity made it possible to examine the different perspectives of stakeholders through joint interaction. To limit heterogeneity the focus groups included active stakeholders only, whose roles and objectives regarding AAC care are usually very similar (Kitzinger, Citation2006; Lazar et al., Citation2017). Please see for detailed participant characteristics and for the composition of each focus group.

Table 1. Characteristics of focus group interview participants

Table 2. Focus groups’ participants

Data collection

The focus group interviews took place at the three AAC counseling centers involved in the project and were conducted by three researchers – one moderator (SAKU) and two persons for documentation (AZ, HS or AL). The interviews lasted an average of 75 minutes (range of 62 minutes to 83 minutes) and were audio recorded. Before the interviews started, all participants were informed verbally about the interview’s aims and the data protection measures applied. Participants were then asked to give their written informed consent. The interviews were conducted by using a semi-structured interview guideline (Goodman et al., Citation2012; Greenbaum, Citation1997; Morgan, Citation1997), which contained the following guiding questions:

How is AAC care currently practiced?

What are your experiences with AAC care?

In your opinion, how should ideal AAC care be organized?

In addition, a stimulus was used; participants were shown a figure illustrating the potential active and passive stakeholders of the AAC network (). Participants were then asked to visualize their positive and negative experiences in working with these stakeholders by using red and green stickers. After that, they were asked to verbally share their experiences.

Data analysis

The audio recordings were transcribed verbatim and pseudonymized. Interview data were analyzed by structured qualitative content analysis according to Kuckartz (Citation2016). First, a priori main categories were derived from the interview guideline. During the coding process, subcategories were inductively formed. The computer-aided coding of the text segments into the categories was performed using the MAXQDA Analytics Pro 2018 (version 18.0.1) software. The entire coding process was performed by two persons (SAKU, AZ) independently, with subsequent consensus agreement.

Ethical considerations

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Oldenburg Medical School (2017–137). The investigation was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration as amended and the underlying data protection regulation (EU GDPR).

Findings

The focus group interviews provide results on how stakeholders in AAC care work together, and which barriers, and facilitators impact collaboration. presents the results of the visualized positive and negative experiences regarding the collaboration with the various stakeholders. Mostly negative experiences were reported for collaboration with health insurance companies but also for collaboration with physicians. Stakeholders experienced collaboration with educators and institutional employees very heterogeneously, as shown by equal numbers of positive and negative experiences. Collaboration with the AAC counseling centers was perceived as almost exclusively positive.

Table 3. Results of the visualization of positive and negative experiences in the collaboration with other stakeholders conducted within the focus group interviews

Based on the narratives of the focus group participants regarding their visualized experiences a category system of barriers to and facilitators of collaboration was developed, which is shown in . The category system is divided into three main categories: central topics of collaboration, interface with active stakeholders, and interface with passive stakeholders. The categories are described below starting with the central topics of collaboration within the inner circle of .

Figure 2. Category system from the focus group interviews on barriers to and facilitators of collaboration in AAC care; METACOM Symbol © Annette Kitzinger

Central topics of collaboration

Central topics of collaboration include topics that many stakeholders mentioned as either barriers, or facilitators for collaboration, and which are therefore not stakeholder-specific. As a result, the following subcategories are relevant across several stakeholder groups and are presented in an aggregated form: openness toward AAC, knowledge about AAC, implementation of AAC, communication between stakeholders.

Openness toward AAC

Positive experiences regarding openness toward AAC were especially noted in the collaboration with teachers. It was reported that teachers were often very willing to use AAC, despite a lack of time and explicit training in AAC. In contrast, mixed experiences were reported for the collaboration with informal caregivers and physicians. Whereas informal caregivers valued the opportunity to exchange views with other stakeholders, informal caregivers often did not understand the need for AAC, as the following quotation from a speech and language pathologist illustrates: “And then […] they [informal caregivers] blocked and said something like, we already understand the kid, and they didn’t want to see why you should learn that or why the kid needs that […] for the future.” (B4CT0#1, speech and language pathologist, 201).

Many stakeholders stated that sheltered workshops negatively influenced collaboration due to a lack of openness toward AAC – as the following quotation shows: “Where a woman had communication needs and they were not met because the sheltered workshop wasn’t willing to even allow her to bring the device with her into the sheltered workshop.” (B4CT0#2, AAC consultant, 197).

Knowledge about AAC

Many stakeholders identified a lack of knowledge about AAC as a central barrier to collaboration and almost exclusively negative experiences were reported – especially in collaboration with physicians, health insurance companies, and therapists. Due to the dependence on physicians, their knowledge about AAC was regarded as crucial, as the following quotation of an AAC consultant illustrates: “In terms of physicians, you have to find one who personally understands what it’s all about and is in favor of it.” (B4CT0#2, AAC consultant, 176).

Furthermore, health insurance companies were often experienced as lacking knowledge about AAC and about different AAC systems, as shown in this quotation: “Well, health insurance companies present a major obstacle because their staff members usually don’t know anything about AAC. They know what a wheelchair is […] but not what AAC is.” (B8CT0#1, AAC consultant, 175).

Implementation of AAC

Regarding the extent to which the implementation of AAC influenced collaboration, many positive and negative experiences were reported – especially concerning collaboration with kindergartens, teachers, physicians, and sheltered workshops. Some kindergartens reportedly already had integrated AAC at the institutional level. However, it often took quite a long time for the children to be supplied with AAC services – as the following quotation illustrates:

Sometimes I think my initial expectations may be too high. I complete something and think, now it will be implemented. And then I wait. […] And I think, well, that way, you already have it. And then, once again, nothing happens. (B4CT0#1, speech and language pathologist, 90).

Concerning sheltered workshops, almost exclusively negative aspects were reported as AAC is often discontinued after the transition from school to a sheltered workshop due to a lack of openness toward AAC – as the following quotation of an AAC consultant illustrates: “[…] with adults, I always hear the argument […] we have tried everything. And now I already know beforehand that I can ask about 10 things […] and they will say no.” (B4BT0#2, AAC consultant, 198).

Communication between stakeholders

Regarding communication between stakeholders as a barrier to or facilitator of collaboration, positive and negative experiences were reported – mostly regarding physicians, therapists, and medical equipment suppliers. Regarding the collaboration with therapists, some examples of good communication with speech and language pathologists were reported, as the following quotation illustrates: “[…] we collaborate with a speech therapy practice; on two afternoons, they also visit our facility. And then, they also provide AAC support. The collaboration is just great.” (B7BT0#1, employee of a home for persons with disabilities, 140).

Negative aspects were reported especially concerning communication with the medical service of the health insurance companies and the health insurance companies themselves. Stakeholders were often not aware of each other’s areas of responsibility, as they do not communicate sufficiently with each other. Also, communication with physicians was often impeded by limited availability (e.g., not being forwarded by telephone to the relevant person).

Interface with active stakeholders

The interviews revealed that the interface with active stakeholders in AAC care is relevant for collaboration as they are directly involved in the use of the AAC systems. Therefore, barriers or facilitators were identified specifically in relation to active stakeholders (please see the middle circle of ).

Informal caregivers

Commitment to AAC implementation

Lack of motivation and commitment of informal caregivers were mentioned as a barrier to collaboration. From the stakeholders’ perspective, family members’ motivation to collaborate is necessary in order to ensure successful implementation of AAC – as the following quotation from an AAC consultant illustrates:

Well, I have to leave a lot to relatives, for them to do. To follow this path. Because no money is available for us to support them along the way. And if they’re motivated, it works well. But here, we do also have a lot of families that are not too motivated or don’t know many paths. Then it falls by the wayside. (B8CT0#1, AAC consultant, 202).

AAC counseling centers

Network development

Counseling centers were regarded as stakeholders that actively facilitate collaboration by building AAC networks – as illustrated by an employee of a home for persons with disabilities:

[…] emphasized over and over again that there was someone who was working toward it, the counseling center pointing out that there is a round table, and going through the trouble of getting everyone to sit at the same table again and again. (B3AT0, employee of a home for persons with disabilities, 347).

Social support of clients

Counseling centers influence the collaboration above all through support of AAC users and their caregivers, for example, by helping them appeal denials of AAC system requests by the health insurance company – as the following quotation illustrates:

We talk about things, and we identify many denials because we have some very simple family members who are very nice but just unable [to determine] whether a mouse, that is, Internet access, which has to be designed differently due to spasticity, whether it will be paid for or not. […] I agree with you there, my colleague has already written so many denials, again in collaboration with the AAC counseling center […] (B3AT0#1, employee of a home for persons with disabilities, 183).

Educators and institutional employees

Working conditions

The working conditions of educators and institutional employees are seen as influencing collaboration, and mixed experiences were reported. Whereas some schools invest in qualifying personnel in AAC, many institutions were reported as understaffed, resulting in a lack of time for AAC. Furthermore, time spent on AAC was in many cases not included in working time. These aspects are illustrated by the following quotation from a remedial teacher:

[…] the kindergarten did not manage to do this because they are simply understaffed and […] they were unable to spend enough time on the individual child. And ultimately, one of us had to do it, to attend to the issue, and then build a communication board, and then also inform the educators and show them how it works. And how it’s intended and so on. There are some … well, there are just some difficulties at the kindergarten because they’re understaffed, those guys. And because they just don’t have any time for that. (B1CT0#2, remedial teacher, 185).

Therapists

Working conditions

Therapists’ working conditions, particularly lack of time, were similarly described as barriers to collaboration, as clarified in this quotation of an AAC consultant: “[…] because I think cooperation is lacking in that therapists are given no time for cooperation.” (B4CT0#2, AAC consultant, 146).

Commitment to AAC implementation

Therapists were often seen as initiating the provision of AAC systems. A lack of collaboration with occupational therapists was emphasized in the interviews as the following quotation illustrates: “And they actually very rarely show up to the round tables. Well, physiotherapists are often there, speech and language pathologists in private practice and often staff speech and language pathologists, but very few occupational therapists.” (B1AT0#1, AAC consultant, 297)

Interface with passive stakeholders

The interviews highlighted that the interface to passive stakeholders has an impact on the collaboration among all stakeholders. In the following, stakeholder-specific barriers or facilitators, which are also presented in the outer circle of , are explained.

Medical care providers

Gatekeeper role

Because physicians as medical care providers have a gatekeeper role in enabling the access to provision with AAC systems, they are described as substantially influencing collaboration. Physicians often feel patronized when caregivers or therapists have to inform them about AAC, leading to a professional dispute, as the following quotation illustrates: “And that is also […] always a professional dispute, it’s a hierarchy problem, because of course, it’s not a therapist or educator’s place to tell a physician what to do.” (B8CT0#1, AAC consultant, 180).

Medical equipment suppliers

Appropriateness of AAC systems

Collaboration with medical equipment suppliers was sometimes described as characterized by distrust and doubt regarding the appropriateness of the AAC system for the individual client. Nevertheless, collaboration with some suppliers was described as trustful. Stakeholders criticized medical equipment suppliers’ economic interests and lack of independent consultation. Thus, AAC care was reported to be more expensive if recommended by a medical equipment supplier. These aspects are illustrated by this quotation:

[…] a large hospital in *urban district3*, every child is discharged with a very exclusive talker the most expensive device the company offers. And they don’t check if the child can even operate the device, if the family even knows how it works. […] And then they’re at home, they call us, and they say, now here we are with this device. (B8CT0#1, AAC consultant, 101).

Health insurance companies

Timely provision of an AAC system

Participants experienced very long waiting times until receipt of the AAC system, particularly when having to appeal denial from the health insurance company. Furthermore, AAC systems were often initially provided for a test phase and were to remain in the household if deemed successful. The delay in provision was said to impact collaboration because collaboration cannot take place without AAC system provision. This is illustrated by the following quotation from a speech and language pathologist:

That the provision simply takes so incredibly long. That you have to appeal […], then you have to write something again, then you have to send it there again, then it might get rejected again, or be sent there again with a justification, so, this entire process, that it takes so incredibly long. (B4CT0#1, speech and language pathologist, 167).

Organization and procedure of AAC care and its funding

Due to the above-mentioned delayed and problematic provision of AAC systems, the organization and procedure of AAC care and its funding was mostly experienced negatively and as particularly exhausting. This is demonstrated by the following quotation from an informal caregiver: “The process is complicated, definitely, not transparent. You don’t get any clear information on what is, in fact, the … the criterion for something being approved or rejected. It’s always a huge fight. Always. I’ve never experienced anything going smoothly there.” (B4AT0#1, mother, 236). However, the development of a collaboration with some health insurance companies was regarded as positive because they increasingly sought advice from AAC counseling centers.

Appropriateness of AAC systems

Participants often experienced dissatisfaction with the health insurance company’s ability to assess the AAC users’ needs and therefore grant an appropriate AAC system. Inappropriate system provision often occurs, which in turn mean that the AAC system will not be used by the client – as the quotation from an AAC consultant illustrates:

Well, the most blatant case I have seen was a man who had worked with *aid_Tablet2* for years and then needed a new device; in this case, the health insurance company wanted to provide a totally different system. And really, the justification […] that it’s really like learning a new language, they couldn’t or wouldn’t understand that at all. (B3BT0#1, AAC consultant, 122).

Collaboration-related desires regarding AAC care

In the focus group interviews the participants were given the opportunity to express their desires for an ideal organization of AAC care. Derived codes on desires concerning better collaboration are presented next. Participants explicitly desired comprehensive, interprofessional, integrated AAC care. This is illustrated by the following quotation from an AAC consultant: “And it’s (chuckles) not about me […] pushing something through, but we think about it together […]. And that’s why I really like moderated round tables because it’s working with a system in place.” (B5AT0, AAC consultant, 349).

Networking was mentioned as a prerequisite that could only be achieved by structural changes that enable teamwork and bring people who jointly use AAC systems together. Participants also wished for a place to turn to with questions about AAC systems and for counseling, as already offered by some AAC counseling centers.

Furthermore, they expressed a need for more willingness to collaborate by all stakeholders involved in care. This is illustrated by the following quotation from a speech and language pathologist:

Overall, I would just like to see more willingness to cooperate by all involved parties; for example, when I as the speech and language pathologist get a prescription from the pediatrician and there is a mistake on there […] that maybe the pediatrician doesn’t feel stepped on his toes because the lowly speech and language pathologist might know more about some things than he does […]. (B1CT0#2, speech and language pathologist, 219).

Participants emphasized that the network should be involved in making the decision about an AAC system in order to ensure the best fit not only for the person in need but also for the person’s network. Because the network must be able to handle the system adequately, their competencies and preferences should be taken into account to ensure acceptance and sustainability of the AAC system.

Most participants found it absolutely essential to initiate communication between the individual stakeholders before choosing an AAC system to first develop a common focus and agree on the care goals, as the quotation of an informal caregiver illustrates: “Still, experience shows […] that it’s extremely important to first initiate communication within the system between the individual experts before you can even start talking about AAC.” (B5BT0#2, personal assistant, 47).

To ensure adequate working conditions, such as sufficient personnel and time for collaboration, collaboration-related expenses must be covered. Moreover, collaboration could be implemented more easily if AAC care was more standardized, preventing the same, AAC user from being supplied with different AAC systems simultaneously. This would ensure that the same AAC systems are used consistently by the different stakeholders, as the quotation of an AAC consultant demonstrates: “That it’s […] consistent. That you don’t offer different systems at school than at home or at the speech and language pathologist’s […].” (B3CT0#2, AAC consultant, 220).

Discussion

We examined collaboration between stakeholders involved in AAC care in Germany, and highlighted barriers to, and facilitators of collaboration, as well as desires regarding collaboration in care from the perspectives of different stakeholders. We identified that the following four factors are central barriers to or facilitators of collaboration: openness toward AAC, knowledge about AAC, implementation of AAC, and communication about AAC. Stakeholder-specific factors, such as working conditions, commitment to AAC implementation, and appropriateness of AAC systems, were revealed.

Overall, collaboration-related experiences were more negative with passive stakeholders than with active stakeholders. Barriers to collaboration, which delayed the receipt of an appropriate AAC system, were often reported. Insufficient knowledge and communication, as well as poor organization, and inappropriateness systems were identified as responsible barriers. Working conditions and poor commitment to AAC implementation were experienced as the main barriers to collaboration with active stakeholders. Especially regarding sheltered workshops and kindergartens, a lack of openness and poor implementation were reported. Collaboration with AAC counseling centers as well as their important role as organizers of the collaboration were emphasized as consistently positive. These results confirm prior knowledge about highly heterogeneous and unregulated AAC care in Germany.

Our results reflect assertions made in the contingency approach of Reeves et al. (Citation2010). This approach includes four different forms of interprofessional work: teamwork, collaboration, coordination, and networking. These four forms differ in the expression of the following elements: shared team identity, clear roles/goals, interdependence, integration, shared responsibility, and team tasks. For teamwork, these elements have the highest level of expression. This level decreases from collaboration to networking approaches. Passive stakeholders are most likely to reflect the networking approach, as the focus group results show that their collaboration is mainly limited to AAC system procurement. Therefore, elements such as integration and shared responsibility seem to be less pronounced in passive stakeholders. Active stakeholders can be classified somewhere between the collaboration and coordination. Speech and language pathologists, for example, tend to have a high degree of shared responsibilities or clarity of roles/goals, but these characteristics are much less pronounced among, for example, occupational therapists. Whereas in the contingency approach, the term collaboration is used as a defined construct, it should be distinguished from the broader use of this term in this article.

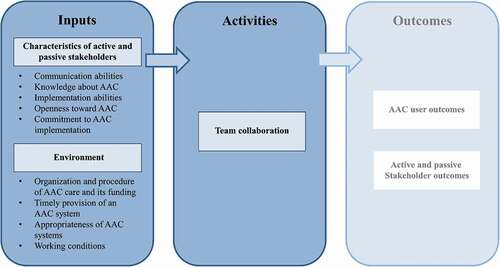

Interestingly, Chung and Stoner (Citation2016) developed a logic model as part of a meta-synthesis of perspectives of team members on supporting students who used AAC at school. This logic model contains three primary categories: inputs, activities, and outcomes. According to this model, certain inputs are necessary for successful collaboration (activities) that in turn influence outcomes such as the use of the AAC system. Applying this model to the present study, which focused not only on the school sector but on the complete AAC network, the derived barriers and facilitators can be defined as inputs that impact collaboration activities and outcomes (). In , outcomes are grayed out as they were not the focus of this research. The characteristics of passive and active stakeholders such as openness toward AAC and certain working conditions (e.g., time, personnel) affect collaboration activities. This model, adapted to the complete AAC network, conceptually summarizes the interrelations between collaboration inputs, which in this study are the identified barriers, and facilitators, collaboration activities, as well as AAC outcomes. Consequently, the transfer to this logic model should primarily present the focus group results in a clear and condensed form within the framework of a conceptual model.

Figure 3. Logic model of interrelations of collaboration inputs, collaboration activities as well as AAC outcomes; own illustration based on Chung and Stoner (Citation2016)

The results also partially align with the conceptual framework for interprofessional teamwork developed by Reeves et al. (Citation2010), which has been applied to several healthcare contexts. Of the four domains identified in the framework, the domains “Relational” such as communication abilities and “Organizational” such as organizational support in the form of working conditions (e.g., time for collaboration) were identified as relevant factors for collaboration in this study. The derived desires correspond to the identified barriers for collaboration so that the desires can be interpreted as a prerequisite for good collaboration in AAC care. The desires underline the relevance of collaboration of all stakeholders who are in contact with the AAC user (e.g., Chung & Douglas, Citation2014). The desire mentioned in this context, that stakeholders, especially informal caregivers, should be involved in the decision-making process was also reflected in the systematic review by Baxter et al. (Citation2012). Based on our results, it can be seen that collaboration among stakeholders involved in AAC care has the potential to create a network with shared responsibilities and common goals in AAC implementation.

Strengths and limitations

Although similar challenges in AAC care have been identified in other countries, the results shown here refer to AAC care in Germany and thus they might not be completely transferable to care in other countries. Although the stakeholders involved in care may be similar in other countries, the regulatory environment might differ. Our results might have been affected by our recruitment of focus group participants that took place with the aid of the AAC counseling centers. As a result, all participants had already been in contact with an AAC counseling center and may thus have more positive experiences than stakeholders in regular care due to improved collaboration fostered by AAC counseling centers. As the focus group interviews were conducted in the AAC counseling centers, we cannot exclude a social desirability bias contributing to more positive evaluations of the AAC counseling centers. The lack of involving AAC users in the focus group interviews can be seen as a limitation. AAC users were not invited to participate due to methodological and pragmatic reasons because AAC users would have needed substantially more support and time to participate in the discussion. For this reason, the views of AAC users are currently being surveyed by conducting individual interviews as part of the larger project. Nevertheless, a large part of the AAC network could be covered in this study and thus a large part of the reality of AAC care in Germany is represented.

Conclusion

This paper makes an important contribution to closing the research gap on collaboration between stakeholders in AAC care. The results show that good collaboration in AAC care is important for the appropriateness of AAC systems as well as for successful implementation of the AAC systems. We clarified the relevance of good collaboration, including with regard to AAC user outcomes. These interrelationships have been found in a few other studies, which were limited to the school sector (e.g., Alant et al., Citation2013; Chung & Stoner, Citation2016; Hunt et al., Citation2002). Although AAC care is a very specific field, some results might be transferable to other forms of complex care such as geriatric care, in which many stakeholders are involved.

Our results suggest that the management of care through an institution such as the AAC counseling center can strengthen the collaboration of stakeholders across different sectors. In addition, the results show that although networking is needed, existing conditions are not yet adequate. Restructuring AAC care to increase collaboration and networking would be the first step. Further research is needed to examine the optimal design of such a restructuring of the health and social care system.

The focus group interviews were conducted as the first step in a larger research project. The next step of the project is to test a new service delivery model as one restructuring approach, also in order to improve the collaboration of the stakeholders (Zinkevich et al., Citation2019). With this new service delivery model, AAC care will be coordinated by the AAC counseling center, and participants will receive independent AAC counseling, patient training, and AAC therapy. Collaboration of the stakeholders involved will be organized as part of case management. Case management is assumed to facilitate collaboration with the passive stakeholders, as it will assist in case of problems with the AAC system procurement. The extent to which this new service delivery model influences collaboration will be investigated as another part of the research project.

Because this paper primarily examines the active stakeholders’ view of collaboration, it would be useful to also examine the passive stakeholders’ view. This perspective could help to improve the identified barriers to collaboration with passive stakeholders.

Authors’ contributions

All authors contributed to designing the study. SAKU drafted all sections of the paper. LA revised all sections of the paper and is the guarantor. SAKU and AZ conducted the focus group interviews and the data analysis. AZ, JB, SKS and TB revised the paper.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ann-Kathrin Löhr (AL) and Helge Schnack (HS) for their excellent support with data collection and all focus group participants and counseling centers for their study participation.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Sarah A. K. Uthoff

Sarah A. K. Uthoff is a Ph.D. candidate at the Department of Health Services Research of the School of Medicine and Health Sciences of the Carl von Ossietzky University of Oldenburg and has a master’s degree in public health. Her Ph.D. thesis is conducted within the project „New Service Delivery Model for Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC) Devices and Intervention„ and focuses on the collaboration of stakeholders involved in AAC care.

Anna Zinkevich

Anna Zinkevich is a Ph.D. candidate at the Department of Health Services Research of the School of Medicine and Health Sciences of the Carl von Ossietzky University of Oldenburg. She is a speech and language pathologist and owns a master’s degree in rehabilitation sciences. Her Ph.D. thesis is conducted within the project „New Service Delivery Model for Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC) Devices and Intervention„ and focuses on care-related burden of informal caregivers involved in AAC.

Jens Boenisch

Jens Boenisch is Professor of Special Education at the Faculty of Human Sciences of the University of Cologne with a professional background in AAC care and research. He is head of the research and counseling center for AAC in Cologne and is scientific project leader of the project „New Service Delivery Model for Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC) Devices and Intervention„.

Stefanie K. Sachse

Stefanie K. Sachse is a senior researcher at the Department of Special Education and Rehabilitation of the Faculty of Human Sciences of the University of Cologne. She works for the research and counseling center for AAC in Cologne and her research focuses on special education in people who rely on AAC.

Tobias Bernasconi

Tobias Bernasconi is a deputy Professor for Special Education at the Technical University Dortmund. He is also a senior researcher at the Department of Special Education and Rehabilitation of the Faculty of Human Sciences of the University of Cologne. He works for the research and counseling center for AAC in Cologne and his research focuses on special education in people who rely on AAC.

Lena Ansmann

Lena Ansmann is Professor for Organizational Health Services Research at the Department of Health Services Research of the School of Medicine and Health Sciences of the Carl von Ossietzky University of Oldenburg. Her work focuses on organizational behavior in healthcare, evaluation and implementation of complex interventions in health care, and patient-centered care.

References

- Alant, E., Champion, A., & Peabody, E. C. (2013). Exploring interagency collaboration in AAC intervention. Communication Disorders Quarterly, 34(3), 172–183. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1525740112455432

- Amelung, V., Hildebrandt, H., & Wolf, S. (2012). Integrated care in Germany – A stony but necessary road! International Journal of Integrated Care, 12(1), Article e16. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5334/ijic.853

- American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (2002). Augmentative and alternative communication: Knowledge and skills for service delivery. American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (Suppl), 22, 97–106. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/98ec/7f063e0095c483bf4c93888c00a41bda8bda.pdf

- Baxter, S., Enderby, P., Evans, P., & Judge, S. (2012). Barriers and facilitators to the use of high-technology augmentative and alternative communication devices: A systematic review and qualitative synthesis. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 47(2), 115–129. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-6984.2011.00090.x

- Beukelman, D. R., Fager, S., Ball, L., & Dietz, A. (2007). AAC for adults with acquired neurological conditions: A review. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 23(3), 230–242. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07434610701553668

- Beukelman, D. R., & Mirenda, P. (2013). Augmentative & alternative communication: Supporting children and adults with complex communication needs (4th ed.). Paul H. Brookes Pub.

- Binger, C., Ball, L., Dietz, A., Kent-Walsh, J., Lasker, J., Lund, S., McKelvey, M., & Quach, W. (2012). Personnel roles in the AAC assessment process. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 28(4), 278–288. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3109/07434618.2012.716079

- Chung, Y. ‑. C., & Douglas, K. H. (2014). Communicative competence inventory for students who use augmentative and alternative communication. TEACHING Exceptional Children, 47(1), 56–68. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0040059914534620

- Chung, Y. ‑. C., & Stoner, J. B. (2016). A meta-synthesis of team members’ voices: What we need and what we do to support students who use AAC. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 32(3), 175–186. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07434618.2016.1213766

- Creer, S., Enderby, P., Judge, S., & John, A. (2016). Prevalence of people who could benefit from augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) in the UK: Determining the need. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 51(6), 639–653. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1460-6984.12235

- D’Amour, D., Goulet, L., Labadie, J. F., Martín-Rodriguez, L. S., & Pineault, R. (2008). A model and typology of collaboration between professionals in healthcare organizations. BMC Health Services Research, 8, Article 188. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-8-188

- Giel, B., & Liehs, A. (2016). ”Moderierte Runde Tische“ (MoRTi) in der Inklusion [“Moderated round tables” (MoRTi) in inclusive education]. Sprachtherapie Aktuell, 3(1), Article e2016–04. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.14620/stadbs160904

- Goodman, E., Kuniavsky, M., & Moed, A. (2012). Observing the user experience: A practitioner’s guide to user research (2nd ed.). Morgan Kaufmann Elsevier.

- Greenbaum, T. L. (1997). The handbook for focus group research (2nd ed.). SAGE.

- Greenhalgh, T. (2008). Role of routines in collaborative work in healthcare organisations. BMJ, 337, Article a2448. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.a2448

- Harding, C., Lindsay, G., O’Brien, A., Dipper, L., & Wright, J. (2011). Implementing AAC with children with profound and multiple learning disabilities: A study in rationale underpinning intervention. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 11(2), 120–129. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-3802.2010.01184.x

- Hunt, P., Soto, G., Maier, J., Müller, E., & Goetz, L. (2002). Collaborative teaming to support students with augmentative and alternative communication needs in general education classrooms. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 18(1), 20–35. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/aac.18.1.20.35

- Hwang, K., Johnston, M., Tulsky, D., Wood, K., Dyson-Hudson, T., & Komaroff, E. (2009). Access and coordination of health care service for people with disabilities. Journal of Disability Policy Studies, 20(1), 28–34. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1044207308315564

- Institute of Medicine. (2001). Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the 21st century. The National Academies Press.

- Jirau-Rosaly, W., Brown, S. P., Wood, E. A., & Rockich-Winston, N. (2020). Integrating an interprofessional geriatric active learning workshop into undergraduate medical curriculum. Journal of Medical Education and Curricular Development, 7, 1–6. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/2382120520923680

- Kitzinger, J. (2006). Focus groups. In C. Pope & N. Mays (Eds.), Qualitative research in health care (3rd ed., pp. 21–31). Blackwell Publishing.

- Kitzinger, J., & Barbour, R. (1999). Developing focus group research: Politics, theory and practice. SAGE Publications.

- Krueger, R. A., & Casey, M. A. (2009). Focus groups: A practical guide for applied research (4th ed.). SAGE.

- Kuckartz, U. (2016). Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse: Methoden, Praxis, Computerunterstützung. Grundlagentexte Methoden [Qualitative content analysis: Methods, practice, software support. Fundamental texts on methods] (3rd ed.). Beltz Juventa.

- Lalani, M., Bussu, S., & Marshall, M. (2020). Understanding integrated care at the frontline using organisational learning theory: A participatory evaluation of multi-professional teams in East London. Social Science & Medicine, 262, Article 113254. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113254

- Lazar, J., Feng, J. H., & Hochheiser, H. (2017). Research methods in human-computer interaction (2nd ed.). Elsevier Morgan Kaufmann.

- Light, J., & McNaughton, D. (2012). The changing face of augmentative and alternative communication: Past, present, and future challenges. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 28(4), 197–204. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3109/07434618.2012.737024

- Loewenbrück, K. F., Stein, D. B., Amelung, V. E., Bitterlich, R., Brumme, M., Falkenburger, B., Fehre, A., Feige, T., Frank, A., Gißke, C., Helmert, C., Kerkemeyer, L., Knapp, A., Lang, C., Leuner, A., Lummer, C., Minkman, M. M. N., Müller, G., van Munster, M., Schlieter, H., Themann, P., Zonneveld, N. & Wolz, M. (2020). Parkinson network eastern Saxony (PANOS): Reaching consensus for a regional intersectoral integrated care concept for patients with Parkinson’s disease in the region of eastern Saxony, Germany. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 9(9), Article 2906. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9092906

- Morgan, D. (1997). Focus groups as qualitative research. SAGE.

- Murray, J., Lynch, Y., Meredith, S., Moulam, L., Goldbart, J., Smith, M., Randall, N., & Judge, S. (2019). Professionals’ decision-making in recommending communication aids in the UK: Competing considerations. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 35(3), 167–179. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07434618.2019.1597384

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2015). Improving diagnosis in health care (E. P. Balogh, B. T. Miller, & J. R. Ball Eds.). The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.17226/21794.

- Patton, M. Q. (2002). Qualitative research and evaluation methods (3rd ed.). SAGE.

- Reeves, S., Lewin, S., Espin, S., & Zwarenstein, M. (2010). Interprofessional teamwork for health and social care. Wiley-Blackwell. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444325027

- Sachse, S. (2010). Interventionsplanung in der Unterstützten Kommunikation: Aufgaben im Kontext der Beratung [Intervention planning in AAC: Tasks in the context of counseling]. von Loeper Verlag.

- Schoen, C., Osborn, R., Squires, D., Doty, M., Pierson, R., & Applebaum, S. (2011). New 2011 survey of patients with complex care needs in eleven countries finds that care is often poorly coordinated. Health Afffairs, 30(12), 2437–2448. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0923

- Sigafoos, J., & Drasgow, E. (2001). Conditional use of aided and unaided AAC. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 16(3), 152–161. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/108835760101600303

- Snodgrass, M. R., & Meadan, H. (2018). A boy and his AAC team: Building instructional competence across team members. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 34(3), 167–179. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07434618.2018.1491059

- Stoner, J. B., Angell, M. E., & Bailey, R. L. (2010). Implementing augmentative and alternative communication in inclusive educational settings: A case study. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 26(2), 122–135. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3109/07434618.2010.481092

- Subihi, A. S. (2013). Saudi special education student teachers’ knowledge of augmentative and alternative communication (AAC). International Journal of Special Education, 28(3), 93–103. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1024412.pdf

- Tsakitzidis, G., Timmermans, O., Callewaert, N., Verhoeven, V., Lopez-Hartmann, M., Truijen, S., Meulemans, H., & van Royen, P. (2016). Outcome indicators on interprofessional collaboration interventions for elderly. International Journal of Integrated Care, 16(2), 1–17. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5334/ijic.2017

- Waller, A. (2013). Public policy issues in augmentative and alternative communication technologies a comparison of the U.K. and the U.S. Interactions, 20(3), 68–75. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1145/2451856.2451872

- Wilkinson, K. M., & Madel, M. (2019). Eye tracking measures reveal how changes in the design of displays for augmentative and alternative communication influence visual search in individuals with down syndrome or autism spectrum disorder. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 28(4), 1649–1658. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1044/2019_AJSLP-19-0006

- World Health Organization. (2010). Framework for action on interprofessional education and collaborative practice (D. Hopkins Eds.). https://www.who.int/hrh/resources/framework_action/en/

- Zinkevich, A., Uthoff, S. A. K., Boenisch, J., Sachse, S. K., Bernasconi, T., & Ansmann, L. (2019). Complex intervention in augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) care in Germany: A study protocol of an evaluation study with a controlled mixed-methods design. BMJ Open, 9(8), Article e029469. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-029469