ABSTRACT

By valuing the knowledge of each discipline holistic patient-centered care can be achieved as decisions arise from expertise rather than established hierarchies. While healthcare has historically operated as a hierarchical power structure (i.e., some voices have more influence), these dynamics are rarely discussed. This review addresses this issue by appraising extant quantitative measures that assess multidisciplinary team (MDT) power dynamics. By identifying psychometrically sound measures, change agents can uncover the collective thought processes informing power structures in practice and develop strategies to mitigate power disparities. Several databases were searched. English language articles were included if they reported on quantitative measures assessing power dynamics among MDTs in acute/hospital settings. Results were synthesized using a narrative approach. In total, 6,202 search records were obtained of which 62 met the eligibility criteria. The review reveals some promising measures to assess power dynamics (e.g., Interprofessional Collaboration Scale). However, the findings also confirm several gaps in the current evidence base: 1) need for further psychometric and pragmatic testing of measures; 2) inclusion of more representative MDT samples; 3) further evaluation of unmatured power dimensions. Addressing these gaps will support the development of future interventions aimed at mitigating power imbalances and ultimately improve collaborative working within MDTs.

Introduction

Within healthcare, teams have become an integral feature of care provision emerging to manage the increasingly complex care needs and multimorbidity of a growing aging population, and to handle the rising prevalence of chronic disease (Hartgerink et al., Citation2014). Gawande (Citation2011) outlines the evolution of health systems from care delivery by one “all-knowing” physician to current practice where patients are cared for by multidisciplinary teams (MDTs). MDTs include healthcare professionals (HCPs) from several disciplines, including physicians, nurses, health and social care professionals (i.e., physiotherapists, occupational therapists, dieticians, social workers, pharmacists), management, and support staff (i.e., healthcare assistants, multi-task assistants). By valuing the skills and knowledge of each discipline, holistic patient-centered care can be achieved (Engel et al., Citation2017). When MDTs appreciate the unique expertise of all professions and promote active participation from each member, care decisions are based on staff experience and knowledge rather than established role hierarchies. This represents a departure from compliance with doctor’s orders to care decisions that refocus on patient priorities (Fox & Reeves, Citation2015). By enabling voices across disciplines and seniority to contribute to care decisions a broader, more holistic perspective can be considered from a social (e.g., social workers) and environmental (e.g., occupational therapy) viewpoint in addition to the medical model.

However, interprofessional collaboration (IPC) is challenging. Each professional group has a unique identity that corresponds to their discipline-specific (typically siloed) training and clinical experience (Ferlie et al., Citation2005). These unique identities mean that despite sharing the same goal of improving patient outcomes, HCPs may have differing priorities, roles, and expectations about how care should be delivered (Braithwaite et al., Citation2016; Hall, Citation2005; Weller et al., Citation2014). These divergent interests can result in HCPs working in discipline-specific silos (nursing, medicine, allied health), where professions may leverage their discipline-specific knowledge to strengthen their voice within the MDT (Hall, Citation2005). However, traditional norms of organizations mean that some voices within MDTs are more valued and have more influence than others (Rogers, De Brún, Birken, et al., Citation2020).

Background

Healthcare has historically operated as a hierarchical power structure with physicians assuming dominant roles (Baker et al., Citation2011; Rogers, De Brún, Birken, et al., Citation2020), while other professions encounter challenges establishing their status in terms of patient care decisions (Hall, Citation2005). A recent review by Okpala (Citation2020) identifies five domains that influence team power dynamics in healthcare: 1) team-related factors (unbalanced allocation of influence, respect for medical hierarchy); 2) role allocation (lack of recognition, lack of delineation of duties, lack of confidence in the skills and competencies of others); 3) communication (nature and tone of communication, receptivity and responsiveness); 4) trust and respect; and 5) individual-related traits (teamwork skills, team attitude). Engum and Jeffries (Citation2012) suggest that imbalances of power between professions can influence communication, the coordination of care, and ultimately patient safety. Despite the reported impact of power dynamics, hierarchical structures in healthcare are rarely explicitly discussed (Gergerich et al., Citation2019) or researched (Baker et al., Citation2011; Paradis & Whitehead, Citation2015). The absence of this discourse suggests a hesitancy to acknowledge the realities of hierarchy in healthcare.

Without an understanding of MDT power dynamics, change agents are unable to address these fundamental patient safety issues (e.g., miscommunication) and develop appropriate strategies to mitigate power imbalances in practice. Many sub-cultures can exist within hospital settings that can create difficulties in conducting in-depth qualitative research across each unit/department. Therefore, employing a measure to assess MDT power dynamics will support change agents to uncover the collective thought processes informing local power structures, which can subsequently guide the development of context-specific strategies to address variations in power dynamics across teams.

The purpose of this review is to identify and appraise extant quantitative measures that assess MDT power dynamics or a dimension of power dynamics as outlined by Okpala (Citation2020). By identifying and appraising these measures, change agents can choose psychometrically sound instruments to investigate MDT power dynamics. This enhanced understanding will help in the development and evaluation of future interventions aimed at exploring and mitigating power imbalances within healthcare teams. Enhanced consistency in the application of such measures will facilitate the conduct of high-quality research and promote the comparability of interventions aimed at improving care provision through improved interdisciplinary working and collaborative care approaches. To address this gap in the current evidence base, this research aims to answer the following research questions: 1) What quantitative survey measures exist to assess the dimensions of power within MDTs in acute care settings? and 2) How do the identified survey instruments compare in terms of their psychometric properties and how they were used?

Methods

This systematic review was conducted to explore the proposed research question. This study was informed by the Cochrane handbook’s (Higgins & Green, Citation2011) guidance for conducting systematic reviews and the Preferred Reporting Items of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) (Moher et al., Citation2009). The review protocol was published on the PROSPERO Database in November 2021 (CRD42021283355).

Search strategy

The five dimensions of power identified by Okpala (Okpala, Citation2020) informed the search strategy (Supplementary material 1). Using keywords in conjunction with truncation and Boolean operators, five electronic databases were searched: Medline, CINAHL, EMBASE PsychINFO, and ABI/Inform. Reference lists of included studies were also hand searched to identify potentially relevant studies that were not retrieved from the database searches. However, no additional relevant articles were retrieved.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The studies were restricted to peer-reviewed articles published in English before July 27, 2021. The eligibility criteria were broad to ensure a balance between a specific and sensitive search of the literature. Empirical studies were included if they reported on the development, validation, or empirical use of one or more quantitative measures assessing power dynamics or a dimension of power dynamics as outlined by Okpala (Citation2020). Searches were limited to studies where healthcare staff working in acute/hospital settings used the quantitative survey measure(s) to self-assess power dynamics within their defined multidisciplinary team (i.e., intradisciplinary teams and studies using a random sample of hospital staff or students were excluded). Previous systematic, literature, narrative, and realist reviews were excluded in addition to descriptive studies, studies using only qualitative methods, and studies using external observers/examiners to assess power dynamics within MDTs. Studies that incorporated a random sample of hospital staff/students or used external observers to rate MDT power dynamics were excluded as contextual factors such as power relations are dynamic and require time to be appropriately understood (Rogerset al., Citation2020).

Study screening and data extraction

Covidence, an online data management system, was employed to manage the review process. Article screening and selection was performed independently by three reviewers (LR, SHS, PA) against the eligibility criteria. The reviewers met to discuss and resolve any conflicts or disagreements. To guide data extraction, the reviewers developed a standardized data extraction tool (Supplementary material 2). Adopting Powell’s et al. (Citation2021) approach, articles were compiled into “measure packets,” which included (1) the measure itself; (2) the measure development article; and (3) all identified empirical uses of the measure retrieved from the database search. Researchers also extracted information relevant to nine psychometric rating criteria from the Psychometric and Pragmatic Evidence Rating Scale (Lewis et al., Citation2018; Powell et al., Citation2021): (1) internal consistency, (2) convergent validity, (3) discriminant validity, (4) known-groups validity, (5) predictive validity, (6) concurrent validity, (7) structural validity, (8) responsiveness, and (9) norms. When a full measure was relevant to assessing power dynamics, researchers reported the psychometric evidence for the full measure. However, if only subscales of a broader measure were relevant, researchers reported the psychometric evidence at the subscale level. Each criterion was rated using Lewis et al.’s (Citation2018) scale: “poor” (−1), “none/absent” (0), “minimal/emerging” (1), “adequate” (2), “good” (3), or “excellent” (4). Ratings were summarized using a “rolled up median” approach to assign a single score for each criterion. If the measure had only one rating for a criterion, this value was the final rating. However, if a measure had multiple ratings for a criterion across several articles, the median score was calculated to generate the final rating. To obtain a conservative score, if the computed median resulted in a non-integer rating, the non-integer was rounded down. When a measure was used more than once, the range for each psychometric property was also provided.

Studies reporting less than two psychometric properties were excluded from phase two of the data extraction process (i.e., quality appraisal, and mapping survey power dimensions). This additional criterion ensured the most robust and reliable measures were appraised in further detail. This decision was determined following a review of the articles included in phase 1 of the data extraction process. While almost all articles reported one psychometric property (i.e., norms), only 21 reported three or more psychometric properties. Thus, to ensure a balance between an inclusive and meaningful appraisal, the authors applied the additional criterion of including studies that reported two or more psychometric properties for phase 2 of the data extraction process.

Quality appraisal and mapping of constructs

As appropriate for the study design, sections of the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) were used to assess the quality of articles included in phase two of data extraction (Hong et al., Citation2018). LR appraised all articles included while SHS independently assessed 10% of included studies. Any disagreements over the quality or risk of bias of the included papers were resolved through discussion. To enhance the transparency in reporting the appraisal process, a summary of the quality assessment can be seen in Supplementary material 3. Subsequently, LR mapped all measures or their subscales to Okpala’s (Citation2020) five dimensions of power (team-related factors; role allocation-related factors; communication; trust and respect; and individual-related traits).

Data synthesis

Due to the aim of this study and the heterogeneity of the articles included a narrative synthesis (Popay et al., Citation2006) and thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006) of the findings was the most appropriate approach to examine the review questions. Okpala’s (Citation2020) five dimensions of power supported to structure the narrative synthesis. Results are reported in accordance with PRISMA guidelines (Moher et al., Citation2009).

Results

Overview

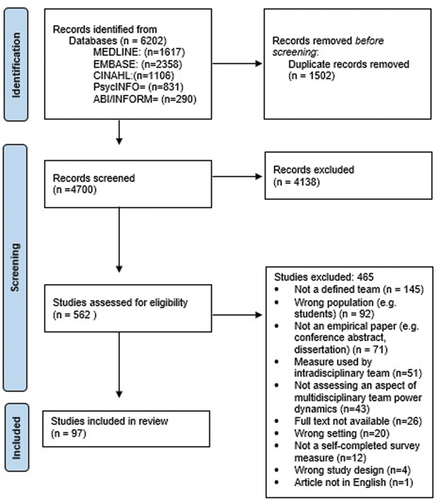

The search returned a total of 6,202 records. Of these, 1,502 were duplicates and were removed. In total, 4,138 articles were excluded following title and abstract screening and a further 465 were excluded during full-text review as they did not meet the inclusion criteria. Reasons for exclusion are evident in the PRISMA diagram (). In total, 97 studies met the inclusion criteria and were reviewed. Sixty-two of these studies reported two or more psychometric properties and progressed to the second phase of data extraction (i.e., quality appraisal and mapping phase).

Phase 1 of data extraction (n = 97 studies)

Supplementary material 4 summaries all empirical uses of identified measures assessing MDT power dynamics (n = 86). Supplementary material 5 outlines study and measure characteristics for papers reporting the development (n = 6) or validation (n = 5) of surveys assessing power. Most studies were conducted in the USA (n = 52), Canada (n = 8), and the UK (n = 7). Studies completed in adult acute care settings were predominantly focused on surgical MDTs (n = 21), while pediatric and neonatal settings mostly conducted their studies among critical care services (n = 8) (Supplementary materials 4 and 5).

While two studies (Ginsburg & Bain, Citation2017; O’Donovan & McAuliffe, Citation2020) provided limited information about their study sample, the remaining ninety-five studies incorporated nursing staff in their sample (i.e., staff nurses, clinical nurse managers, clinical nurse specialists, and advanced nurse practitioners). Eighty-eight studies included physicians (junior and senior physicians), health and social care professionals participated in 42 studies (physiotherapists (n = 25), pharmacists (n = 16), social workers (n = 15) were the most frequently cited), while support staff (healthcare assistants most frequently cited (n = 15)) and administrative staff were incorporated in 17 and 13 studies, respectively. Many articles (n = 35) focused solely on power relations between nurses and physicians

Thirty-six of the included studies employed a cross-sectional approach and four conducted a mixed methods evaluation to explore staff perceptions of interdisciplinary teamworking (e.g., communication openness, MDT collaboration). The remaining studies (36 pre-post designs, 3 mixed methods papers, 6 cohort analytic studies, and 1 cluster randomized control trial) evaluated the impact of a new initiative or care model on team functioning (e.g., structured interdisciplinary rounds, interdisciplinary team training).

Phase 2 of data extraction (n = 62 studies)

lists the 35 studies with limited psychometric information (i.e., less than two psychometric properties), which were excluded from phase two of data extraction. While Smits et al. (Citation2003) reported limited psychometric properties for the Group Environment Scale used within their study, the authors provide adequate information for the additional bespoke measure employed, which resulted in the article's inclusion in the next phase of data extraction. Within the 62 remaining papers (shaded in gray in Supplementary materials 4 and 5), 43 measures were identified (Safety Attitudes Questionnaire (SAQ) full scale and relevant subscales referred to as one measure). Seventy-seven percent (n = 33) of these included measures were used once. The most frequently used surveys were the SAQ (as a full scale and relevant subscales) (n = 20), the Collaboration and Satisfaction about Care Decision-Making scale (n = 5), the Relational Coordination measure (n = 4), and the Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture questionnaire (n = 4). presents the median and range psychometric properties available for the 43 identified measures. reports the diverse psychometric values for the SAQ when researchers use the measure as a full scale or when subscales are adopted. illustrates the dimensions of power dynamics associated with each included survey. While 81% of measures assessed communication processes within MDTs (n = 35), only 15 surveys evaluated role allocation. The Interprofessional Collaboration Scale (Kenaszchuk et al., Citation2010) and Team Development measure (Stock et al., Citation2013) were the only questionnaires that assessed all five power dimensions (). are categorized by Okpala’s (Citation2020) five dimensions of power and present side-by-side comparisons of the psychometric information extracted for each measure.

Table 1. List of studies with limited psychometric properties.

Table 2. Summary of psychometric properties for included measures.

Table 3. Summary of power dimensions assessed by included measures.

Narrative synthesis

Given the heterogeneity of the included papers, studies and their relevant measures are described in the following narrative synthesis using Okpala’s (Citation2020) dimensions of power. The Interprofessional Collaboration Scale assessed all five dimensions of power and provided the most comprehensive psychometric evaluation (recording four out of the nine criteria sought in the rating scale). Overall, measurement quality for the included scales was poor with only five measures (i.e., Assessment for Collaborative Environments, SAQ, Communication and Sharing Information scale, Interprofessional Collaboration Scale, and Healthcare Team Vitality Instrument) receiving an overall score of 9 or higher (out of a possible score of 36).

Team-related factors

Team-related factors refer to the unbalanced allocation of influence within MDTs. Twenty-five surveys identified in this review evaluated this power dimension and assessed whether team decision-making was collaborative (i.e., based on team members’ collective expertise) or embedded in traditional hierarchical assumptions (i.e., physician autonomy). Measures within this domain were primarily developed or used in the USA (76%) by nurses and physicians working in inpatient medical units (36%) (Bohmann et al., Citation2021; Deneckere et al., Citation2013; Drekonja et al., Citation2019; Hastings et al., Citation2016; Khoshab et al., Citation2019; San Martin-Rodriguez et al., Citation2008; Sim et al., Citation2020; Smits et al., Citation2003; Vazirani et al., Citation2005) or multiple team types (36%) (e.g., emergency department, critical care units) (Al-Araidah et al., Citation2018; Ballangrud et al., Citation2017; Deilkas & Hofoss, Citation2008; Ginsburg & Bain, Citation2017; Grymonpre et al., Citation2016; Lavoie-Tremblay et al., Citation2014; Ribeliene et al., Citation2019; Sexton et al., Citation2006; Zaheer et al., Citation2019). Evidence of norms was available for 23 measures, internal consistency for 21 measures, known-group validity for 9 measures, structural validity for 4 measures, convergent validity for 3 measures, and discriminant validity for 1 measure. No psychometric evidence was available for predictive validity, concurrent validity, or responsiveness. The median rating for internal consistency and convergent validity for the included measures assessing team-related factors was good (score = 3). An adequate median rating (score = 2) was identified for norms and discriminant validity (based on one measure, the Interprofessional Collaboration Scale (Kenaszchuk et al., Citation2010), while the rating for structural validity and known group validity was minimal (score = 1). The highest rated measures of team-related factors were the Assessment for Collaborative Environments (Tilden et al., Citation2016) and the SAQ (Sexton et al., Citation2006) which both scored 11 out of a possible score of 36. While the Assessment for Collaborative Environments was used by one study (Tilden et al., Citation2016) and reported excellent (score = 4) internal consistency and convergent validity, adequate norms (score = 2) and minimal structural validity (score = 1), the SAQ used by 20 papers (Abdi et al., Citation2015; Bognar et al., Citation2008; Bohmann et al., Citation2021; Carvalho et al., Citation2015; Chaboyer et al., Citation2013; Chu-Weininger et al., Citation2010; Davenport et al., Citation2007; Deilkas & Hofoss, Citation2008; Drekonja et al., Citation2019; Dwyer et al., Citation2018; Gillespie et al., Citation2018; Ginsburg & Bain, Citation2017; Müller et al., Citation2018; O’leary et al., Citation2010; Pannick et al., Citation2017; Profit et al., Citation2012, Citation2017; Schwendimann et al., Citation2013; Sexton et al., Citation2006; Zaheer et al., Citation2019) scored excellent norms (score = 4), good internal consistency and structural validity (score = 3), and minimal known group validity (score = 1).

Role allocation

Fifteen measures assessed role allocation that refers to staff understanding, recognition, and appreciation of team members’ roles. Sixty-seven percent of measures assessing role allocation were primarily developed and used in the USA and employed by nurses and doctors. Developmental and validation studies focused on broad team types (e.g., MDT working in an inpatient unit) (Kenaszchuk et al., Citation2010; Stock et al., Citation2013; Tilden et al., Citation2016; Yildirim et al., Citation2006), while empirical studies assessing this dimension most frequently investigated surgical MDTs (Burtscher et al., Citation2020; Gittell et al., Citation2000; Paige et al., Citation2009; Villemure et al., Citation2019). Evidence of internal consistency was available for all 15 measures, norms for 14 measures, known-group validity for 3 measures, structural validity for 3 measures, convergent validity for 2 measures, and discriminant validity for 1 measure. No psychometric evidence was available for predictive validity, concurrent validity, or responsiveness. The median rating for internal consistency and convergent validity for the included measures assessing role allocation was good (score = 3). A median rating of adequate (score = 2) was identified for norms and discriminant validity (based on one measure, the Interprofessional Collaboration Scale (Kenaszchuk et al., Citation2010)) and for known-group validity and structural validity the median rating was minimal (score = 1). The highest rated measure of role allocation was the Assessment for Collaborative Environments (Tilden et al., Citation2016) as outlined above. The next highest scoring measure was the Interprofessional Collaboration Scale (Kenaszchuk et al., Citation2010). This study reported good internal consistency (score = 3) and adequate convergent validity, discriminant validity, and structural validity (score = 2).

Communication

Thirty-five measures assessed MDT communication. Topics incorporated in this domain include information exchange (i.e., frequency, accuracy, and timeliness) and the inclusivity of communication. Measures evaluating communication were primarily developed and used in the USA (69%) among surgical MDTs (Bognar et al., Citation2008; Burtscher et al., Citation2020; Carvalho et al., Citation2015; Davenport et al., Citation2007; Gillespie et al., Citation2018; Gittell et al., Citation2000; Klipfel et al., Citation2011; Maxson et al., Citation2011; Müller et al., Citation2018; Paige et al., Citation2009; Villemure et al., Citation2019), where the sample predominantly incorporated nurses and physicians. Evidence of norms was available for 34 measures, internal consistency for 31 measures, known-group validity for 17 measures, structural validity for 5 measures, convergent validity for 3 measures, and discriminant validity for 1 measure. No psychometric evidence was available for predictive validity, concurrent validity, or responsiveness. The median rating for internal consistency and convergent validity for the included measures assessing communication was good (score = 3). For structural validity, norms and discriminant validity (based on one measure (Kenaszchuk et al., Citation2010)), the median rating was adequate (score = 2) and for known group validity the rating was minimal (score = 1). The highest rated measures of communication were the Assessment for Collaborative Environments (Tilden et al., Citation2016) and SAQ (scoring 11) (Abdi et al., Citation2015; Bognar et al., Citation2008; Bohmann et al., Citation2021; Carvalho et al., Citation2015; Chaboyer et al., Citation2013; Chu-Weininger et al., Citation2010; Davenport et al., Citation2007; Deilkas & Hofoss, Citation2008; Drekonja et al., Citation2019; Dwyer et al., Citation2018; Gillespie et al., Citation2018; Ginsburg & Bain, Citation2017; Müller et al., Citation2018; O’leary et al., Citation2010; Pannick et al., Citation2017; Profit et al., Citation2012, Citation2017; Schwendimann et al., Citation2013; Sexton et al., Citation2006; Zaheer et al., Citation2019) as outlined above.

Trust and respect

Eighteen measures assessed trust and respect within MDTs. These measures evaluated team psychological safety (i.e., staff comfort speaking up and taking interpersonal risks), and staff perceptions of feeling valued within their MDTs. Seventy-eight percent of measures were developed or employed in the USA, among nurses and physicians in surgical settings (Bognar et al., Citation2008; Burtscher et al., Citation2020; Carvalho et al., Citation2015; Davenport et al., Citation2007; Gillespie et al., Citation2018; Gittell et al., Citation2000; Müller et al., Citation2018; Sifaki-Pistolla et al., Citation2020). Evidence of norms was available for 17 measures, internal consistency for 16 measures, known-group validity for 9 measures, structural validity and convergent validity for 3 measures, and discriminant validity for 1 measure. No psychometric evidence was available for predictive validity, concurrent validity, or responsiveness. The median rating for internal consistency and convergent validity for the included measures assessing communication was good (score = 3). For structural validity, norms, and discriminant validity (based on one measure (Kenaszchuk et al., Citation2010)) the median rating was adequate (score = 2). The median rating for known group validity was absent (score = 0). The highest rated measures of communication was the Assessment for Collaborative Environments (Tilden et al., Citation2016) and SAQ (both scoring 11) (Abdi et al., Citation2015; Bognar et al., Citation2008; Bohmann et al., Citation2021; Carvalho et al., Citation2015; Chaboyer et al., Citation2013; Chu-Weininger et al., Citation2010; Davenport et al., Citation2007; Deilkas & Hofoss, Citation2008; Drekonja et al., Citation2019; Dwyer et al., Citation2018; Gillespie et al., Citation2018; Ginsburg & Bain, Citation2017; Müller et al., Citation2018; O’leary et al., Citation2010; Pannick et al., Citation2017; Profit et al., Citation2012, Citation2017; Schwendimann et al., Citation2013; Sexton et al., Citation2006; Zaheer et al., Citation2019) as outlined above.

Individual-related factors

Individual-related factors refer to the skills (e.g., conflict management) and attitudes of individual MDT members (friendliness, extra-role behaviors). Seventeen measures identified in this review evaluated this power dimension. Most were primarily developed or used in the USA (76%) among nurses and physicians in surgical teams or across multiple team types (Abu-Rish Blakeney et al., Citation2019; Al-Araidah et al., Citation2018; Ballangrud et al., Citation2017; Deilkas & Hofoss, Citation2008; Ginsburg & Bain, Citation2017; Grymonpre et al., Citation2016; Lavoie-Tremblay et al., Citation2014; Ribeliene et al., Citation2019; Sexton et al., Citation2006; Zaheer et al., Citation2019). Evidence of norms was available for 16 measures, internal consistency for 15 measures, known-group validity for 11 measures, structural validity for 2 measures, and convergent and discriminant validity for 1 measure. No psychometric evidence was available for predictive validity, concurrent validity, or responsiveness. The median rating for internal consistency for the included measures assessing individual-related factors was good (score = 3). For convergent validity, norms, and discriminant validity (based on one measure (Kenaszchuk et al., Citation2010)), the median rating was adequate (score = 2). While the median rating for structural validity was minimal (score = 1), a score for known group validity was absent (score = 0). The highest rated measures of individual-related factors was the SAQ (scoring 11) (Abdi et al., Citation2015; Bognar et al., Citation2008; Bohmann et al., Citation2021; Carvalho et al., Citation2015; Chaboyer et al., Citation2013; Chu-Weininger et al., Citation2010; Davenport et al., Citation2007; Deilkas & Hofoss, Citation2008; Drekonja et al., Citation2019; Dwyer et al., Citation2018; Gillespie et al., Citation2018; Ginsburg & Bain, Citation2017; Müller et al., Citation2018; O’leary et al., Citation2010; Pannick et al., Citation2017; Profit et al., Citation2012, Citation2017; Schwendimann et al., Citation2013; Sexton et al., Citation2006; Zaheer et al., Citation2019), followed by the Interprofessional Collaboration Scale (Kenaszchuk et al., Citation2010) (scoring 9) (details outlined above).

Discussion

The objective of this systematic review was to identify and appraise the existing quantitative measures assessing MDT power dynamics or a dimension of power dynamics as outlined by Okpala’s (Citation2020) (i.e., team-related factors, role allocation, communication, trust and respect, and individual related factors). The extant literature emphasizes the importance of IPC in the provision of optimum patient care (Engel et al., Citation2017). However, to enhance shared responsibility and decision-making among MDTs, the influence of power should be named and addressed (Cohen Konrad et al., Citation2019). This recommendation links to an important finding of this review, which is that no study used their measure to explicitly investigate MDT power dynamics. Instead, these studies aimed to more broadly understand teamworking or evaluate the effectiveness of an intervention on team functioning (e.g., communication processes). Future research in the field of interprofessional care and teamworking needs to openly name and assess MDT power dynamics as understanding these team characteristics, support the development and integration of context-specific interventions to address power disparities in healthcare teams.

Wider macro-level determinants (e.g., governance of care) assist to reinforce these historical power structures in MDTs (i.e., medical dominance) (Baker et al., Citation2011). However, Rogers et al. (Citation2020) emphasize that team-level contextual factors (e.g., team culture) have been almost entirely overlooked in the extant literature implementing change. Therefore, gaining a better understanding of MDT power dynamics and designing context-specific approaches to address these disparities ought to be a priority to support the delivery of collaborative, safe patient-centered care. However, this transparency may result in recruitment challenges and researchers must recognize the increased potential for self-selection bias toward HCPs with extreme experiences of MDT working (i.e., hierarchical vs. collaborative).

While the findings identified some promising measures to assess MDT power dynamics, many studies insufficiently reported on the psychometric properties of their chosen measures. The Interprofessional Collaboration Scale (Kenaszchuk et al., Citation2010) assessed all five power dimensions and provided the most comprehensive psychometric evaluation, recording four out of the nine criteria sought in the rating scale (Lewis et al., Citation2018). However, like most of the measures included (77% of measures used once), only one study used this scale. Most measures provided evidence of norms and internal consistency (95% and 86%, respectively). Although one measure received a poor rating for internal consistency (Assessment of Interprofessional Team Collaboration scale (Grymonpre et al., Citation2016)), over 25% of measures reporting norms scored poorly on the rating scale (see ). This finding likely reflects the limited empirical use of these measures that impacts scale generalizability. Additionally, evidence of other psychometric properties was sparse (i.e., known group validity (n = 20), structural validity (n = 4), convergent validity (n = 3), discriminant validity (n = 1)), insufficiently described or unavailable to extract (i.e., concurrent validity, predictive validity, responsiveness) (see ).

Overall, measurement quality for the included scales was poor. With the exception of internal consistency and convergent validity (based on three studies), most median ratings ranged from absent (score = 0) to adequate (score = 2). Only five measures (i.e., Assessment for Collaborative Environments, SAQ, Communication and Sharing Information scale, Interprofessional Collaboration Scale, and Healthcare Team Vitality Instrument) received an overall score of 9 or higher (out of a possible score of 36). Therefore, future work needs to prioritize further psychometric testing of promising measures identified in this review. The pragmatic properties of these measures also require consideration, as the usability of these scales will likely impact their use in practice.

Additionally, the findings of this review emphasize a continued focus on the nurse–physician dyad in interprofessional care. While this result may relate to the acute care focus of this review, the extant literature suggests that these findings may also reflect the status of medicine, nurses making up the majority of the healthcare workforce, and the historical power relations that exist between these professions (i.e., the dominant–subordinate relationship) (Price et al., Citation2014; Reeves et al., Citation2008). Despite improving the range and quality of services offered to patients, power dynamics across other professional groups (e.g., health and social care professionals and support staff) appears to remain relatively unexplored. Boyce (Citation2006) and Kessler et al. (Citation2010) confirm that many of these disciplines feel marginalized and perceive their influence as invisible or undervalued by their MDTs. However, with health systems prioritizing the better integration of care across acute and community services, these undervalued professions will assume a critical role in this health reform. Therefore, future research exploring MDT power dynamics should expand their sample to accurately depict what represents an authentic/true team in modern healthcare.

Despite the cited importance of role clarity for successful interprofessional working (Ambrose-Miller & Ashcroft, Citation2016; Reeves et al., Citation2010) (i.e., prevent interdisciplinary tension by defining role expectations and avoiding infringement of professional boundaries), role allocation was the least frequently assessed power dimension by the included measures (n = 15). Instead, most (n = 35) investigated interpersonal communication, a factor central to much of the IPC literature (Wei et al., Citation2022). To gain a more holistic understanding of MDT power dynamics, future studies need to proportionately investigate all power dimensions. Similarly, the importance of context in interprofessional collaborative practice needs to be more consistently assessed across settings. While four power dimensions were primarily assessed among surgical staff, team-related factors were the only domain predominantly evaluated among medical MDTs. Literature suggests that the acuity and complexity of care mediates the level of IPC required, which may explain why many studies chose surgical settings as requiring greater investigation (DiazGranados et al., Citation2018; Nugus et al., Citation2010; Retchin, Citation2008). Additionally, the limited focus on team-related factors in surgical settings may reflect the assumption that physician authority is necessary due to the task-oriented nature of the specialty (Rogers et al., Citation2013; Teunissen et al., Citation2020). Emphasizing the importance of technical skills over interpersonal behaviors may explain why authority and influence are factors less frequently assessed among surgical MDTs. However, this assumption requires further investigation in the future research.

Limitations

Despite the final search yielding thousands of articles, the endeavor to strike a balance between a sensitive and specific search strategy increases the possibility that relevant articles may have been omitted from this review. The inclusion of purely empirical studies heightens the risk of publication bias as the gray literature was not appraised. However, we hope to have limited the impact of these challenges and present a comprehensive synthesis of the best available evidence by scanning reference lists of included articles to retrieve additional relevant studies.

Conclusion

This review set out to systematically identify and critically appraise extant quantitative measures that assess MDT power dynamics. The review reveals some promising measures to assess the five dimensions of power outlined by Okpala’s (Citation2020). However, the findings also confirm several gaps in the current evidence base such as the need for 1) further psychometric and pragmatic testing of measures assessing power dynamics; 2) including more representative samples that depict true MDT membership; and 3) further evaluating unmatured dimensions of power (e.g., role allocation) in diverse healthcare contexts. Addressing these gaps will support the development and evaluation of future interventions aimed at mitigating power imbalances and ultimately enhancing care provision by improving collaborative working within MDTs.

Availability of data and material

Data used in this study is available through the journal articles cited herein.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (286.6 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr Emma Nicholson and Dr Robert Fox for providing their expertise during the planning phase of this systematic review.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2023.2168632

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Lisa Rogers

Dr. Lisa Rogers is an Assistant Professor at UCD Centre for Research, Education, and Innovation in Health Systems (UCD IRIS) in the School of Nursing, Midwifery, and Health Systems in University College Dublin, Ireland. She is a registered nurse, whose research interests include healthcare team dynamics and implementation science. Dr. Rogers holds a BSc. in General Nursing, MRes in Clinical Research and a PhD in Nursing, Midwifery, and Health Systems.

Shannon Hughes Spence

Shannon Hughes Spence was a research assistant at UCD IRIS in the School of Nursing, Midwifery, and Health Systems while writing this paper. Currently, she is a PhD student at the South East Technological University (SETU), Ireland. Her PhD focuses on young women’s experiences in the night time economy in Ireland, covering themes such as power, resistance, risk and safety. Hughes Spence holds a BA (Hons) in Community and Youth Development and a MSc in Sociology.

Praveenkumar Aivalli

Praveenkumar Aivalli is a PhD student at the UCD IRIS at the School of Nursing, Midwifery and Health Systems in University College Dublin, Ireland. His research interests include health policy and systems research, realist evaluation, implementation research, health system strengthening and quantitative epidemiological methods. He is an Ayurvedic Physician by profession and holds a post-graduate qualification in Public Health.

Aoife De Brún

Dr. Aoife De Brún is Assistant Professor at the UCD IRIS in the School of Nursing, Midwifery and Health Systems in University College Dublin, Ireland. She is a registered Chartered Psychologist with the British Psychological Society with experience of multi-disciplinary projects in health research. Her research interests include a range of topics in applied health and organisational psychology including team dynamics, collective leadership, and quality and safety in healthcare. Dr De Brún holds a BA(Hons) in Psychology and a PhD in Social Sciences.

Eilish McAuliffe

Prof Eilish McAuliffe is Professor of Health Systems at UCD and the Director of the UCD IRIS in the School of Nursing, Midwifery, and Health Systems. Her research activity is primarily focused on strengthening health systems. Utilising interdisciplinary approaches to identify problems in existing service provision, particularly in the areas of leadership, teamwork and organizational culture, she co-designs and evaluates new models and approaches to improve the quality and safety of healthcare. Prof McAuliffe holds a BSc. in psychology, an M.Sc. in Clinical Psychology, an MBA and a PhD in Health Strategy.

References

- Aaberg, O. R., Hall-Lord, M. L., Husebø, S. I. & Ballangrud, R. (2021). A human factors intervention in a hospital - evaluating the outcome of a TeamSTEPPS program in a surgical ward. BMC Health Services Research, 21(1). https://doi.org/10.1111/21110.1186/s12913-021-06071-6

- Abdi, Z., Delgoshaei, B., Ravaghi, H., Abbasi, M., & Heyrani, A. (2015). The culture of patient safety in an Iranian intensive care unit. Journal of Nursing Management, 23(3), 333–345. https://doi.org/10.1111/jonm.12135

- Abu-Rish Blakeney, E., Lavallee, D. C., Baik, D., Pambianco, S., O’Brien, K. D., & Zierler, B. K. 2019. Purposeful interprofessional team intervention improves relational coordination among advanced heart failure care teams. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 33(5), 481–489. CINAHL Plus. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2018.1560248

- Acal Jiménez, R., Swartz, M., & McCorkle, R. (2018). Improving Quality Through Nursing Participation at Bedside Rounds in a Pediatric Acute Care Unit: A Pilot Project. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 43, 45–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedn.2018.08.010

- Adams, H. A., & Feudale, R. M. (2018). Implementation of a Structured Rounding Tool for Interprofessional Care Team Rounds to Improve Communication And Collaboration in Patient Care. Pediatric Nursing, 44(5), 229–246.

- Aeyels, D., Bruyneel, L., Seys, D., Sinnaeve, P. R., Sermeus, W., Panella, M. & Vanhaecht, K. (2019). Better hospital context increases success of care pathway implementation on achieving greater teamwork: a multicenter study on STEMI care. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 31(6), 442–448. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzy197

- Al-Araidah, O., Nader, A. T., Mariam, B., & Nabeel, M. 2018. A study of deficiencies in teamwork skills among Jordan caregivers. International Journal of Health Care Quality Assurance, 314, 350–360. ABI/INFORM Global. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJHCQA-11-2016-0175

- Ambrose-Miller, W., & Ashcroft, R. (2016). Challenges Faced by Social Workers as Members of Interprofessional Collaborative Health Care Teams. Health & Social Work, 41(2), 101–109. https://doi.org/10.1093/hsw/hlw006

- Austin, S., Powers, K., Florea, S., & Gaston, T. (2021). Evaluation of a nurse practitioner–led project to improve communication and collaboration in the acute care setting. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract, 33(9), 746–753. https://doi.org/10.1097/JXX.0000000000000402

- Awad, S. S., Fagan, S. P., Bellows, C., Albo, D., Green-Rashad, B., De la Garza, M., & Berger, D. H. (2005). Bridging the communication gap in the operating room with medical team training. American Journal of Surgery, 190(5), 770–774.

- Baker, L., Egan Lee, E., Martimianakis, M. A., & Reeves, S. (2011). Relationships of power-implications for interprofessional education. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 25(2), 98–104. https://doi.org/10.3109/13561820.2010.505350

- Ballangrud, R., Husebø, S. E., & Hall-Lord, M. L. 2017. Cross-cultural validation and psychometric testing of the Norwegian version of the TeamSTEPPS® teamwork perceptions questionnaire. BMC Health Services Research, 171, 1–10. CINAHL Plus. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2733-y

- Bamford, D., & Griffin, M. (2008). A case study into operational team‐working within a UK hospital. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 28(3), 215–237. https://doi.org/10.1108/01443570810856161

- Bognar, A., Barach, P., Johnson, J. K., Duncan, R. C., Birnbach, D., Woods, D., Holl, J. L., & Bacha, E. A. (2008). Errors and the burden of errors: Attitudes, perceptions, and the culture of safety in pediatric cardiac surgical teams. The Annals of Thoracic Surgery, 85(4), 1374–1381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.athoracsur.2007.11.024

- Bohmann, F. O., Guenther, J., Gruber, K., Manser, T., Steinmetz, H., Pfeilschifter, W., & STREAM Trial investigators. (2021). Simulation-based training improves patient safety climate in acute stroke care (STREAM). Neurological Research and Practice, 3(1), 37. https://doi.org/10.1186/s42466-021-00132-1

- Boyce, R. (2006). Emerging from the shadow of medicine: Allied health as a ‘profession community’ subculture. Health Sociology Review, 15(5), 520–534. https://doi.org/10.5172/hesr.2006.15.5.520

- Braithwaite, J., Clay-Williams, R., Vecellio, E., Marks, D., Hooper, T., Westbrook, M., Westbrook, J., Blakely, B., & Ludlow, K. (2016). The basis of clinical tribalism, hierarchy and stereotyping: A laboratory-controlled teamwork experiment. BMJ Open, 6(7), e012467. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012467

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Bursiek, A. A., Hopkins, M. R., Breitkopf, D. M., Grubbs, P. L., Joswiak, M. E., Klipfel, J. M., & Johnson, K. M. (2020). Use of High-Fidelity Simulation to Enhance Interdisciplinary Collaboration and Reduce Patient Falls. J Patient Saf, 16(3), 245–250. https://doi.org/10.1097/PTS.0000000000000277

- Burtscher, M. J., Nussbeck, F. W., Sevdalis, N., Gisin, S., & Manser, T. 2020. Coordination and communication in healthcare action teams: The role of expertise. Swiss Journal of Psychology, 793–4, 123–135. APA PsycInfo®. https://doi.org/10.1024/1421-0185/a000239

- Carvalho, P. A., Göttems, L. B. D., Pires, M. R. G. M., & Oliveira, M. L. C. D. (2015). Safety culture in the operating room of a public hospital in the perception of healthcare professionals. Revista latino-americana de enfermagem, 23(6), 1041–1048. https://doi.org/10.1590/0104-1169.0669.2647

- Catchpole, K. R., Dale, T. J., Hirst, D. G., Smith, J. P., & Giddings, T. AEB. (2010). A Multicenter Trial of Aviation-Style Training for Surgical Teams. Journal of Patient Safety, 6(3), 180–186. https://doi.org/10.1097/PTS.0b013e3181f100ea

- Chaboyer, W., Chamberlain, D., Hewson-Conroy, K., Grealy, B., Elderkin, T., Brittin, M., McCutcheon, C., Longbottom, P., & Thalib, L. (2013). Safety culture in Australian intensive care units: Establishing a baseline for quality improvement. American Journal of Critical Care, 22(2), 93–102. https://doi.org/10.4037/ajcc2013722

- Chu-Weininger, M. Y. L., Wueste, L., Lucke, J. F., Weavind, L., Mazabob, J., & Thomas, E. J. (2010). The impact of a tele-ICU on provider attitudes about teamwork and safety climate. Quality & Safety in Health Care, 19(6), e39. https://doi.org/10.1136/qshc.2007.024992

- Cohen Konrad, S., Fletcher, S., Hood, R., & Patel, K. (2019). Theories of power in interprofessional research – developing the field. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 33(5), 401–405. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2019.1669544

- Davenport, D. L., Henderson, W. G., Mosca, C. L., Khuri, S. F., & Mentzer, R. M. J. (2007). Risk-adjusted morbidity in teaching hospitals correlates with reported levels of communication and collaboration on surgical teams but not with scale measures of teamwork climate, safety climate, or working conditions. Journal of the American College of Surgeons, 205(6), 778–784. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.07.039

- Deilkas, E. T., & Hofoss, D. (2008). Psychometric properties of the Norwegian version of the safety attitudes questionnaire (SAQ), generic version (short form 2006). BMC Health Services Research, 8(101088677), 191. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-8-191

- de Lima Garcia, C., Bezerra, I. M., Ramos, J. L., do Valle, J. E., Bezerra de Oliveira, M. L., Abreu, L. C., & Vaismoradi, M. (2019). Association between culture of patient safety and burnout in pediatric hospitals. PLoS ONE, 14(6), e0218756.https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.021875610.1371/journal.pone.0218756.g00110.1371/journal.pone.0218756.t00110.1371/journal.pone.0218756.t00210.1371/journal.pone.0218756.t00310.1371/journal.pone.0218756.t00410.1371/journal.pone.0218756.t005

- Deneckere, S., Euwema, M., Lodewijckx, C., Panella, M., Mutsvari, T., Sermeus, W., & Vanhaecht, K. Better interprofessional teamwork, higher level of organized care, and lower risk of burnout in acute health care teams using care pathways: A cluster randomized controlled trial. (2013). Medical care, 51(1), 99–107. Embase. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182763312

- DiazGranados, D., Dow, A. W., Appelbaum, N., Mazmanian, P. E., & Retchin, S. M. (2018). Interprofessional practice in different patient care settings: A qualitative exploration. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 32(2), 151–159. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2017.1383886

- Drekonja, D. M., Grigoryan, L., Lichtenberger, P., Graber, C. J., Patel, P. K., Van, J. N., Dillon, L. M., Wang, Y., Gauthier, T. P., Wiseman, S. W., Shukla, B. S., Naik, A. D., Hysong, S. J., Kramer, J. R., & Trautner, B. W. (2019). Teamwork and safety climate affect antimicrobial stewardship for asymptomatic bacteriuria. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology, 40(9), 963–967. https://doi.org/10.1017/ice.2019.176

- Dwyer, L., Smith, A., McDermott, R., Breatnach, C., El-Khuffash, A., & Corcoran, J. D. (2018). Staff attitudes towards patient safety culture and working conditions in an Irish tertiary neonatal unit. Irish Medical Journal, 111(7), 786.

- Engel, J., Prentice, D., & Taplay, K. (2017). A power experience: A phenomenological study of interprofessional education. Journal of Professional Nursing, 33(3), 204–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.profnurs.2016.08.012

- Engum, S. A., & Jeffries, P. R. (2012). Interdisciplinary collisions: Bringing healthcare professionals together. Collegian (Royal College of Nursing, Australia), Australia), 19(3), 145–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colegn.2012.05.005

- Ferlie, E., Fitzgerald, L., Wood, M., & Hawkins, C. (2005). The nonspread of innovations: the mediating role of professionals. Academy of Management Journal, 48(1), 117–134. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2005.15993150

- Fox, A., & Reeves, S. (2015). Interprofessional collaborative patient-centred care: A critical exploration of two related discourses. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 29(2), 113–118. https://doi.org/10.3109/13561820.2014.954284

- France, D. J., Greevy, R. A., Liu, X., Burgess, H., Dittus, R. S., Weinger, M. B., & Speroff, T. (2010). Measuring and Comparing Safety Climate in Intensive Care Units. Medical Care, 48(3), 279–284. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181c162d6

- Gawande, A. (2011). Cowboys and Pit Crews. The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/news/news-desk/cowboys-and-pit-crews

- Gergerich, E., Boland, D., & Scott, M. A. (2019). Hierarchies in interprofessional training. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 33(5), 528–535. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2018.1538110

- Gillespie, B. M., Harbeck, E., Kang, E., Steel, C., Fairweather, N., & Chaboyer, W. 2018. Changes in surgical team performance and safety climate attitudes following expansion of perioperative services: A repeated-measures study. Australian Health Review, 42(6), 703–708. CINAHL Plus. https://doi.org/10.1071/AH17079

- Ginsburg, L., & Bain, L. 2017. The evaluation of a multifaceted intervention to promote “speaking up” and strengthen interprofessional teamwork climate perceptions. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 31(2), 207–217. APA PsycInfo®. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2016.1249280

- Gittell, J. H., Fairfield, K. M., Bierbaum, B., Head, W., Jackson, R., Kelly, M., Laskin, R., Lipson, S., Siliski, J., Thornhill, T., & Zuckerman, J. (2000). Impact of relational coordination on quality of care, postoperative pain and functioning, and length of stay: A nine-hospital study of surgical patients. Medical care, 38(8), 807–819. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-200008000-00005

- Gosling, A. S., Westbrook, J. I., & Braithwaite, J. (2003). Clinical team functioning and IT innovation: A study of the diffusion of a point-of-care online evidence system. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association : JAMIA, 10(3), 244–251

- Grymonpre, R., Bowman, S., Rippin-Sisler, C., Klaasen, K., Bapuji, S. B., Norrie, O., & Metge, C. (2016). Every team needs a coach: Training for interprofessional clinical placements. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 30(5), 559–566. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2016.1181611

- Gupta, R. T., Sexton, J. B., Milne, J., & Frush, D. P. (2015). Practice and Quality Improvement: Successful Implementation of TeamSTEPPS Tools Into an Academic Interventional Ultrasound Practice. American Journal of Roentgenology, 204(1), 105–110. https://doi.org/10.2214/AJR.14.12775

- Hall, P. (2005). Interprofessional teamwork: Professional cultures as barriers. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 19(sup1), 188–196. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820500081745

- Haller, G., Garnerin, P., Morales, M., Pfister, R., Berner, M., Irion, O., Clergue, F., & Kern, C. (2008). Effect of crew resource management training in a multidisciplinary obstetrical setting. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 20(4), 254–263. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzn018

- Halverson, A. L. (2009). Surgical Team Training. Arch Surg, 144(2), 107. https://doi.org/10.1001/archsurg.2008.545

- Hartgerink, J. M., Cramm, J. M., Bakker, T. J. E. M., Van Eijsden, A. M., Mackenbach, J. P., & Nieboer, A. P. The importance of multidisciplinary teamwork and team climate for relational coordination among teams delivering care to older patients. (2014). Journal of Advanced Nursing, 70(4), 791–799. Medline. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.12233

- Hastings, S. E., Suter, E., Bloom, J., & Sharma, K. 2016. Introduction of a team-based care model in a general medical unit. BMC Health Services Research, 161. ABI/INFORM Global. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-016-1507-2

- Hendricks, S., LaMothe, V. J., Halstead, J. A., Taylor, J., Ofner, S., Chase, L., Dunscomb, J., Chael, A., & Priest, C. (2018). Fostering interprofessional collaborative practice in acute care through an academic-practice partnership. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 32(5), 613–620. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2018.1470498

- Higgins, J. P., & Green, S. (2011). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews. John Wiley & Sons. http://handbook-5-1.cochrane.org/

- Hill, M., Roberts, M., Alderson, M., & Gale T. (2015). Safety culture and the 5 steps to safer surgery: an intervention study. British Journal of Anaesthesia, 114(6), 958–962. https://doi.org/10.1093/bja/aev063

- Hilt, A. D., Kaptein, A. A., Schalij, M. J., & van Schaik, J. (2020). Teamwork and safety attitudes in complex aortic surgery at a Dutch hospital: Cross-sectional survey study. JMIR Human Factors, 7(1), 11.

- Hong, Q. N., Pluye, P., Fàbregues. S., Bartlett, G., Boardman, F., Cargo, M.et al. (2018). Mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT). Canadian Intellectual Property Office, Industry Canada. Available from: http://mixedmethodsappraisaltoolpublic.pbworks.com/w/file/fetch/127916259/MMAT_2018_criteria-manual_2018-08-01_ENG.pdf

- Kenaszchuk, C., Reeves, S., Nicholas, D., & Zwarenstein, M. 2010. Validity and reliability of a multiple-group measurement scale for interprofessional collaboration. BMC Health Services Research, 101, 83. ABI/INFORM Global. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-10-83

- Kessler, I., Heron, P., Dopson, S., Magee, H., Swain, D., & Askham, J. (2010). The nature and consequences of support workers in a hospital setting. NIHR Service Delivery Organisation Programme.

- Khoshab, H., Nouhi, E., Tirgari, B., & Ahmadi, F. (2019). A survey on teamwork status in caring for patients with heart failure: A cross-sectional study. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 33(1), 8–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2018.1512959

- Klipfel, J. M., Gettman, M. T., Johnson, K. M., Olson, M. E., Derscheid, D. J., Maxson, P. M., Arnold, J. J., Moehnke, D. E., Nelson, E. A. S., & Vierstraete, H. T. (2011). Using high-fidelity simulation to develop nurse-physician teams. Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing, 42(8), 347–349. https://doi.org/10.3928/00220124-20110201-02

- Kuy, S., & Romero, R. AL. (2017). Improving staff perception of a safety climate with crew resource management training. Journal of Surgical Research, 213, 177–183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2016.04.013

- Lau, C. Y. et al. (2020). UC Care Check—A Postoperative Neurosurgery Operating Room Checklist: An Interrupted Time Series Study. J Healthc Qual, 42(4), 224–235. https://doi.org/10.1097/JHQ.0000000000000246

- Lavoie-Tremblay, M., O’Conner, P., Harripaul, A., Biron, A., Ritchie, J., Lavigne, G. L., Baillargeon, S., Ringer, J., MacGibbon, B., Taylor Ducharme, S., & Sourdif, J. 2014. The effect of transforming care at the bedside initiative on healthcare teams’ work environments. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing, 11(1), 16–25. APA PsycInfo®. https://doi.org/10.1111/wvn.12015

- Lewis, C. C., Mettert, K. D., Dorsey, C. N., Martinez, R. G., Weiner, B. J., Nolen, E., Stanick, C., Halko, H., & Powell, B. J. (2018). An updated protocol for a systematic review of implementation-related measures. Systematic Reviews, 7(1), 66. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-018-0728-3

- Lisbon, D., Allin, D., Cleek, C., Roop, L., Brimacombe, M., Downes, C., & Pingleton, S. K. (2016). Improved Knowledge, Attitudes, and Behaviors After Implementation of TeamSTEPPS Training in an Academic Emergency Department. Am J Med Qual, 31(1), 86–90. https://doi.org/10.1177/1062860614545123

- Masten, M., Sommerfeldt, S., Gordan, S., Greubel, E., Canning, C., Lioy, J., & Chuo, J. (2019). Evaluating Teamwork in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. Advances in Neonatal Care, 19(4), 285–293. https://doi.org/10.1097/ANC.0000000000000604

- Maxson, P. M., Dozois, E. J., Holubar, S. D., Wrobleski, D. M., Dube, J. A. O., Klipfel, J. M., & Arnold, J. J. (2011). Enhancing nurse and physician collaboration in clinical decision making through high-fidelity interdisciplinary simulation training. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 86(1), 31–36. https://doi.org/10.4065/mcp.2010.0282

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., & Group, P. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Annals of Internal Medicine, 151(4), 264–269. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135

- Müller, P., Tschan, F., Keller, S., Seelandt, J., Beldi, G., Elfering, A., Dubach, B., Candinas, D., Pereira, D., & Semmer, N. K. 2018. Assessing perceptions of teamwork quality among perioperative team members. AORN journal, 108(3), 251–262. CINAHL Plus. https://doi.org/10.1002/aorn.12343

- Murphy, T., Laptook, A., & Bender, J. (2018). Sustained Improvement in Neonatal Intensive Care Unit Safety Attitudes After Teamwork Training. J Patient Saf, 14(3), 174–180. https://doi.org/10.1097/PTS.0000000000000191

- Notaro, K. A., dos Corrêa, A., Tomazoni, A., Rocha, P. K., & Manzo, B. F. (2019). Cultura de segurança da equipe multiprofissional em Unidades de Terapia Intensiva Neonatal de hospitais públicos. Rev. Latino-Am. Enfermagem, 27. https://doi.org/10.1590/1518-8345.2849.3167

- Nugus, P., Greenfield, D., Travaglia, J., Westbrook, J., & Braithwaite, J. (2010). How and where clinicians exercise power: Interprofessional relations in health care. Social Science & Medicine, 71(5), 898–909. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.05.029

- O’Donovan, R., & McAuliffe, E. 2020. Exploring psychological safety in healthcare teams to inform the development of interventions: Combining observational, survey and interview data. BMC Health Services Research, 20(1), 810. Medline. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-020-05646-z

- Okpala, P. (2020). Addressing power dynamics in interprofessional health care teams. International Journal of Healthcare Management, 0(0), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/20479700.2020.1758894

- O’Leary, K. J., Creden, A. J., Slade, M. E., Landler, M. P., Kulkarni, N., Lee, J., Vozenilek, J. A., Pfeifer, P., Eller, S., Wayne, D. B., & Williams, M. V. (2015). Implementation of unit-based interventions to improve teamwork and patient safety on a medical service. American Journal of Medical Quality: The Official Journal of the American College of Medical Quality, 30(5), 409–416. https://doi.org/10.1177/1062860614538093

- O’Leary, K. J., Wayne, D. B., Haviley, C., Slade, M. E., Lee, J., & Williams, M. V. 2010. Improving teamwork: Impact of structured interdisciplinary rounds on a medical teaching unit. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 25(8), 826–832. APA PsycInfo®. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-010-1345-6

- Opper, K., Beiler, J., Yakusheva, O., & Weiss, M. (2019). Effects of Implementing a Health Team Communication Redesign on Hospital Readmissions Within 30 Days. Worldviews on Evidence‐Based Nursing, 16(2), 121–130. https://doi.org/10.1111/wvn.12350

- Paige, J. T., Aaron, D. L., Yang, T., Howell, D. S., & Chauvin, S. W. (2009). Improved operating room teamwork via SAFETY prep: A rural community hospital’s experience. World Journal of Surgery, 33(6), 1181–1187. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-009-9952-2

- Pannick, S., Athanasiou, T., Long, S. J., Beveridge, I., & Sevdalis, N. (2017). Translating staff experience into organisational improvement: The HEADS-UP stepped wedge, cluster controlled, non-randomised trial. BMJ Open, 7(7), e014333. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014333

- Paradis, E., & Whitehead, C. R. (2015). Louder than words: Power and conflict in interprofessional education articles, 1954-2013. Medical Education, 49(4), 399–407. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.12668

- Patterson, M. D., Geis, G. L., LeMaster, T., & Wears, R. L. (2013). Impact of multidisciplinary simulation-based training on patient safety in a paediatric emergency department. BMJ Qual Saf, 22(5), 383–393. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2012-000951

- Paull, D. E., DeLeeuw, L. D., Wolk, S., Paige, J. T., Neily, J., & Mills, P. D. (2013). The Effect of Simulation-Based Crew Resource Management Training on Measurable Teamwork and Communication Among Interprofessional Teams Caring for Postoperative Patients. J Contin Educ Nurs, 44(11), 516–524. https://doi.org/10.3928/00220124-20130903-38

- Piers, R. D., Versluys, K., Devoghel, J., Vyt, A., & Van Den Noortgate, N. (2019). Interprofessional teamwork, quality of care and turnover intention in geriatric care: A cross-sectional study in 55 acute geriatric units. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 91, 94–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2018.11.011

- Popay, J., Roberts, H., Sowden, A., Petticrew, M., Arai, L., Rodgers, M., Britten, N., Roen, K., & Duffy, S. (2006). Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. A Product from the ESRC Methods Programme.

- Powell, B. J., Mettert, K. D., Dorsey, C. N., Weiner, B. J., Stanick, C. F., Lengnick-Hall, R., Ehrhart, M. G., Aarons, G. A., Barwick, M. A., Damschroder, L. J., & Lewis, C. C. (2021). Measures of organizational culture, organizational climate, and implementation climate in behavioral health: A systematic review. Implementation Research and Practice, 2, 26334895211018864. https://doi.org/10.1177/26334895211018862

- Prenestini, A., Lega, F., & Webb, J., (2013). Do Senior Management Cultures Affect Performance? Evidence From Italian Public Healthcare Organizations. Journal of Healthcare Management, 58(5), 336–351.

- Prentice, D., Jung, B., Taplay, K., Stobbe, K., & Hildebrand, L. (2016). Staff perceptions of collaboration on a new interprofessional unit using the Assessment of Interprofessional Team Collaboration Scale (AITCS). Journal of Interprofessional Care, 30(6), 823–825. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2016.1218447

- Price, S., Doucet, S., & McGillis Hall, L. (2014). The historical social positioning of nursing and medicine: Implications for career choice, early socialization and interprofessional collaboration. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 28(2), 103–109. https://doi.org/10.3109/13561820.2013.867839

- Profit, J., Etchegaray, J., Petersen, L. A., Sexton, J. B., Hysong, S. J., Mei, M., & Thomas, E. J. (2012). Neonatal intensive care unit safety culture varies widely. Archives of Disease in Childhood Fetal and Neonatal Edition, 97(2), F120–6. https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2011-300635

- Profit, J., Sharek, P. J., Kan, P., Rigdon, J., Desai, M., Nisbet, C. C., Tawfik, D. S., Thomas, E. J., Lee, H. C., & Sexton, J. B. (2017). Teamwork in the NICU setting and its association with health care-associated infections in very low-birth-weight infants. American Journal of Perinatology, 34(10), 1032–1040. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0037-1601563

- Reeves, S., Lewin, S., Espin, S., & Zwarenstein, M. 2010. A conceptual framework for interprofessional teamwork. Interprofessional Teamwork for Health and Social Care, 57–76. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444325027.ch4

- Reeves, S., Nelson, S., & Zwarenstein, M. (2008). The doctor–nurse game in the age of interprofessional care: A view from Canada. Nursing Inquiry, 15(1), 1–2. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1800.2008.00396.x

- Retchin, S. M. (2008). A conceptual framework for interprofessional and co-managed care. Academic Medicine, 83(10), 929–933. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181850b4b

- Ribeliene, J., Blazeviciene, A., Nadisauskiene, R. J., Tameliene, R., Kudreviciene, A., Nedzelskiene, I., & Macijauskiene, J. (2019). Patient safety culture in obstetrics and gynecology and neonatology units: The nurses’ and the midwives’ opinion. Journal of Maternal-Fetal and Neonatal Medicine, 32(19), 3244–3250. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767058.2018.1461831. Embase.

- Rogers, L., De Brún, A., Birken, S. A., Davies, C., & McAuliffe, E. (2020). The micropolitics of implementation; a qualitative study exploring the impact of power, authority, and influence when implementing change in healthcare teams. BMC Health Services Research, 20(1059). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-020-05905-z

- Rogers, L., De Brún, A., & McAuliffe, E. (2020). Defining and assessing context in healthcare implementation studies: A systematic review. BMC Health Services Research, 20(591). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-020-05212-7

- Rogers, D. A., Lingard, L., Boehler, M. L., Espin, S., Mellinger, J. D., Schindler, N., & Klingensmith, M. (2013). Surgeons managing conflict in the operating room: Defining the educational need and identifying effective behaviors. American Journal of Surgery, 205(2), 125–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2012.05.027

- San Martin-Rodriguez, L., D’Amour, D., & Leduc, N. (2008). Outcomes of interprofessional collaboration for hospitalized cancer patients. Cancer Nursing, 31(2), E18–27. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NCC.0000305701.99411.ac

- Schwendimann, R., Zimmermann, N., Kung, K., Ausserhofer, D., & Sexton, B. (2013). Variation in safety culture dimensions within and between us and Swiss hospital units: An exploratory study. BMJ Quality & Safety, 22(1), 32–41. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2011-000446

- Scotten, M., Manos, E. L., Malicoat, A., & Paolo, A. M. (2015). Minding the gap: Interprofessional communication during inpatient and post discharge chasm care. Patient Education and Counseling, 98(7), 895–900. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2015.03.009

- Sexton, J. B., Helmreich, R. L., Neilands, T. B., Rowan, K., Vella, K., Boyden, J., Roberts, P. R., & Thomas, E. J. 2006. The safety attitudes questionnaire: Psychometric properties, benchmarking data, and emerging research. BMC Health Services Research, 61, 10. APA PsycInfo®. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-6-44

- Sifaki-Pistolla, D., Melidoniotis, E., Dey, N., & Chatzea, V. -E. 2020. How trust affects performance of interprofessional health-care teams. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 34(2), 218–224. APA PsycInfo®. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2019.1631763

- Sim, M. A., Lee, S. -H., Phan, P. H., & Lateef, A. 2020. Quality improvement at an acute medical unit in an Asian academic center: A mixed methods study of nursing work dynamics. Nursing outlook, 68(2), 169–183. CINAHL Plus. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.outlook.2019.09.002

- Smits, S. J., Falconer, J. A., Herrin, J., Bowen, S. E., & Strasser, D. C. (2003). Patient-focused rehabilitation team cohesiveness in veterans administration hospitals. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 84(9), 1332–1338. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0003-9993(03)00197-7

- Stock, R., Mahoney, E., & Carney, P. A. (2013). Measuring team development in clinical care settings. Family Medicine, 45(10), 691–700.

- Strasser, D. C., Falconer, J. A., Herrin, J. S., Bowen, S. E., Stevens, A. B., & Uomoto, J. (2005). Team functioning and patient outcomes in stroke rehabilitation. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 86(3), 403–409.

- Teunissen, C., Burrell, B., & Maskill, V. (2020). Effective surgical teams: An integrative literature review. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 42(1), 61–75. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193945919834896

- Tilden, V. P., Eckstrom, E., & Dieckmann, N. F. (2016). Development of the assessment for collaborative environments (ACE-15): A tool to measure perceptions of interprofessional “teamness”. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 30(3), 288–294. https://doi.org/10.3109/13561820.2015.1137891

- Vazirani, S., Hays, R. D., Shapiro, M. F., & Cowan, M. 2005. Effect of a multidisciplinary intervention on communication and collaboration among physicians and nurses. American Journal of Critical Care, 14(1), 71–77. APA PsycInfo®. https://doi.org/10.4037/ajcc2005.14.1.71

- Villemure, C., Georgescu, L. M., Tanoubi, I., Dubé, J. -N., Chiocchio, F., & Houle, J. Examining perceptions from in situ simulation-based training on interprofessional collaboration during crisis event management in post-anesthesia care. (2019). Journal of Interprofessional Care, 33(2), 182–189. APA PsycInfo®. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2018.1538103

- Wei, H., Horns, P., Sears, S. F., Huang, K., Smith, C. M., & Wei, T. L. (2022). A systematic meta-review of systematic reviews about interprofessional collaboration: Facilitators, barriers, and outcomes. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 0(0), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2021.1973975

- Weller, J., Boyd, M., & Cumin, D. 2014. Teams, tribes and patient safety: Overcoming barriers to effective teamwork in healthcare. Postgraduate medical journal, 891061, 149–154. CINAHL Plus. https://doi.org/10.1136/postgradmedj-2012-131168

- Yildirim, A., Akinci, F., Ates, M., Ross, T., Issever, H., Isci, E., & Selimen, D. 2006. Turkish version of the Jefferson scale of attitudes toward physician-nurse collaboration: A preliminary study. Contemporary Nurse, 23(1), 38–45. APA PsycInfo®. https://doi.org/10.5172/conu.2006.23.1.38

- Zaheer, S., Ginsburg, L., Wong, H. J., Thomson, K., Bain, L., & Wulffhart, Z. (2019). Turnover intention of hospital staff in Ontario, Canada: Exploring the role of frontline supervisors, teamwork, and mindful organizing. Human Resources for Health, 17(1), 66. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-019-0404-2

- Zech, A. et al. (2017). Evaluation of simparteam - a needs-orientated team training format for obstetrics and neonatology.J Perinat Med, 45(3), 333–341. https://doi.org/10.1515/jpm-2016-0091