ABSTRACT

The ward round (WR) is an important opportunity for interprofessional interaction and communication enabling optimal patient care. Pharmacists’ participation in the interprofessional WR can reduce adverse drug events and improve medication appropriateness and communication. WR participation by clinical pharmacists in Australia is currently limited. This study aims to explore what is impacting clinical pharmacists’ participation in WRs in Australian hospitals. A self-administered, anonymous national survey of Australian clinical pharmacists was conducted. This study describes the outcomes from qualitative questions which were analyzed thematically in NVivo-2020 according to Braun and Clarke’s techniques. Five themes were constructed: “Clinical pharmacy service structure”, “Ward round structure”, “Pharmacist’s capabilities”, “Culture” and “Value”. A culture supportive of pharmacist’s contribution with a consistent WR structure and flexible delivery of clinical pharmacy services enabled pharmacists’ participation in WR. Being physically “absent” from the WR due to workload, workflow, and self-perception of the need for extensive clinical knowledge can limit opportunities for pharmacists to proactively contribute to medicines decision-making with physicians to improve patient care outcomes. Bidirectional communication between the interprofessional team and the pharmacist, where there is a co-construction of each individual’s role in the WR facilitates consistent and inter-dependent collaborations for effective medication management.

Introduction

Effective teamwork is critical for safe, high-quality healthcare utilizing the skills and perspective that each member of the healthcare team brings to meet patients’ needs (Langlois, Citation2020b). When done well, ward rounds (WRs) can be an example of collaborative teamwork where team members develop a sense of interdependency and make collective sense of patient scenarios (Langlois, Citation2020a; Walton et al., Citation2020). WRs are an important process for communication around the management of inpatients in hospitals and therefore enable pharmacists to be involved in shared decision-making (Perversi et al., Citation2018; Surani & Varon, Citation2015). However, pharmacists’ participation in interprofessional activities such as WR is not routine practice in Australian hospitals (Babu et al., Citation2023).

Background

The involvement of clinical pharmacists in WR has been shown to significantly reduce adverse drug events (ADE) (Bosma et al., Citation2018; Kang et al., Citation2013; Kucukarslan et al., Citation2003; Leape et al., Citation1999; SHPA, Citation2013), and improve medication appropriateness and communication (Bullock et al., Citation2019, Citation2020). For example, a single blind standard care-controlled study found that the ADEs were lower when the pharmacist participated in the WR in addition to documenting medication histories and providing discharge counseling compared to “usual” care (identifying medication problems after medication review each morning) (Kucukarslan et al., Citation2003). There were 5.7 ADE per 1000 patient days in the intervention group compared with 26.5 ADE per 1000 patient days in the “usual” care group which only had a pharmacist to retrospectively solve problems after a prescription has been written and potentially administered to the patient (Kucukarslan et al., Citation2003). Pharmacists’ that participated in WR also had improved job satisfaction compared to those who did not participate (83% versus 65%, respectively, p = .004) (Nguyen-Thi et al., Citation2021). Similarly, a self-administered questionnaire looking into physicians' perception of clinical pharmacy services found that the majority of physicians (76%) were comfortable with pharmacists participating in the WR and assisting them with developing a medication management plan (Li et al., Citation2014). However, an Australian national survey of clinical pharmacists conducted by us highlighted that only 39% of the clinical pharmacists participated in a WR in the previous fortnight, with factors such as lack of role recognition and understaffing being some of the factors that influenced WR participation (Babu et al., Citation2023). Our national survey included free-text responses in addition to the quantitative responses, however these responses were not included in the initial analysis of results. Previous studies have shown that simply relying on quantitative data misses the rich descriptions provided by the respondents (McKillip et al., Citation1992; Moffatt et al., Citation2006; Sofaer, Citation1999; York et al., Citation2011). The open-ended survey questions and responses in our national survey provided a forum for pharmacists to share their experience and views on particular topics, expanding on the responses provided in the quantitative sections of the survey (McKillip et al., Citation1992; Sofaer, Citation1999). Therefore, we conducted an in-depth thematic analysis of free-text survey responses contained in the national survey to gain a deeper understanding on what is impacting pharmacists’ participation in ward rounds.

After the construction of the themes, this study then used collaborative working relationship model to explain the extent and nature of collaboration between the clinical pharmacists and the broader healthcare team (Brock & Doucette, Citation2003; Doucette et al., Citation2005). The collaborative working relationship model postulates that the clinical pharmacists and the medical team can pass through stages of collaboration (Brock & Doucette, Citation2003; Doucette et al., Citation2005). Each stage is characterized by differing levels of interprofessional interaction, trust, interdependence, and shared decision-making (Brock & Doucette, Citation2003). The collaborative working relationship model describes collaboration with the medical team as a continuum (Brock & Doucette, Citation2003). It extends from stage 0 (professional awareness) where interactions are of short duration and discrete to stage 4 (commitment to Collaborative Working Relationship) where pharmacists and the medical team display inter-dependence which is influenced by duration and consistent collaboration (Brock & Doucette, Citation2003).

Methods

We conducted a self-administered, anonymous electronic survey of Australian hospital pharmacists. The overall aim of the survey was to explore the organizational factors, team factors, and individual pharmacists’ characteristics that impact pharmacists’ participation in ward rounds.

The study design and quantitative results have been reported previously (Babu et al., Citation2023). The survey was open to Australian pharmacists who were ≥18 years of age, currently working in an Australian hospital in a clinical unit setting in the 2 weeks prior to completing the survey. The survey was distributed to the members of The Society of Hospital Pharmacists of Australia (SHPA) and promoted on pharmacist-specific threads on social media platforms such as Twitter and Facebook. The survey was open from 29th November 2021 to 24th January 2022 and took approximately 10 min to complete. The survey involved a combination of closed demographic questions, Likert scale responses aimed to capture participant agreement to various statements relating to enablers and barriers to WR participation and open-ended questions. This paper reports on the responses to the open-ended questions. The open-ended questions were generated based on author experience as well as literature (see Supplementary Material One for the full list of open-ended questions). Prior research has shown that positive responses to commitment questions are associated with an increased uptake of the actions or behaviors highlighted in the commitment questions (Pratt et al., Citation2015). Therefore, we included a free-text response commitment question which asked participants to complete the sentence, “I am more likely to participate in the ward round if … .” Open-ended questions give the respondents the opportunity to formulate and present their views and beliefs in a way that is not directed by the survey developers. These questions also allowed the respondents to describe any additional factors that influence WR participation. We performed a qualitative analysis of free-text responses that pharmacists provided in the national survey, to identify what is impacting WR participation. The data are reported using the “Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR).”

The open-ended survey questions asked the respondents to describe past or current workplace experiences that facilitate or hinder WR participation, and what can be improved at an individual level, team level, or organizational level to enable WR participation.

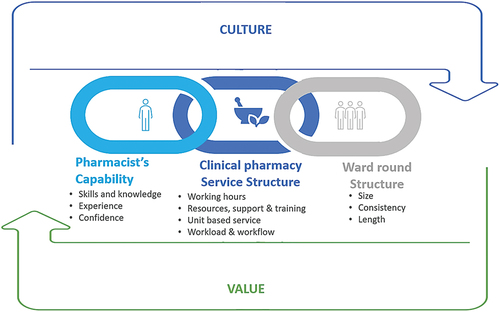

The free-text responses were analyzed thematically on NVivo (version: 2020) following Braun and Clarke’s techniques of (1) familiarization of data, (2) generating codes, (3) searching for themes, (4) reviewing themes, (5) defining and naming themes and (6) write up (Clarke & Braun, Citation2017; Nowell et al., Citation2017). A reflexive thematic analysis was undertaken with an inductive approach utilizing semantic coding. Two authors (DB and SM) independently read the survey free text responses and analyzed the data set to produce initial codes (for themes) of the responses line by line. Themes and subthemes were developed by initially exploring clustered patterns across the entire dataset and combining codes into potential themes and subthemes. Each theme and subtheme were discussed at de-briefs between the two authors, to ensure that they were distinct but broad enough to capture the concepts contained in the survey comments. Any changes made during each de-brief were documented in independent reflexive journals written by the individual authors. As recommended by Crabtree and Miller (Citation1999), we used a diagrammatic representation to explore relationships between the themes (see ) (Crabtree et al., Citation1999).

Figure 1. Diagrammatic representation of the factors that influence the participation in ward rounds.

Research rigor was established by confirming the criteria of credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability. The method of investigator triangulation (two authors independently analyzing and producing codes) was employed to increase credibility and confirmability as similar findings can provide confirmation of results and the differing viewpoints can increase the depth of the themes constructed (Carter et al., Citation2014). Peer-debriefing amongst the other members of the research team not involved in the coding process provided an external check to ensure that the preliminary codes and the final codes were comprehensively constructed from the raw data. A reflexive journal maintained by DB and SM throughout the process of coding ensured that the process was traceable and clearly documented (dependability). To ensure transferability, descriptions and surrounding text are provided for the quotation where applicable so that the readers can judge the transferability of the findings to their context or site.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was granted by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of South Australia (ID: 204320). Participants provided consent for their responses to be used in this research. The following statement was included at the beginning of the questionnaire “By completing and submitting the questionnaire/survey, you are indicating that you have read and understood the Participant Information Sheet and give your consent to the research team to use your responses”.

shows the interplay between each of the five themes identified in our study. It shows how “Pharmacist’s capabilities”, “Clinical pharmacy service structure”, and “Ward round structure” are interconnected. For example, respondents stated that the “Clinical pharmacy service structure” characteristics such as training, and dedicated resources and support would increase their skills, and confidence (Pharmacist’s capability) in contributing to the WR. Even when all the “Clinical pharmacy service structure” characteristics were aligned such that pharmacists are able to participate, the WR structure also needs to be conducive to pharmacist participation. also shows that when departments have a culture that is supportive and values pharmacist’s contribution in WRs, pharmacists were supported with consistent “Ward round structure” and “Clinical pharmacy service structure”.

Results

Ninety-nine participants provided free-text responses. Respondents (clinical pharmacists) had a median age of 34 years and 69.7% were female. Ninety-seven percent of the respondents worked in a public hospital, and the median number of years of experience as a pharmacist was 9 (IQR 5–18). Five inter-related overarching themes relating to factors that influence participation in the WR were constructed from the participant’s free-text responses.

Theme 1: clinical pharmacy service structure

This theme describes the structure in which the clinical pharmacy services are delivered. Participants described demanding workloads and competing tasks that limited their ability to participate in WR. The clinical pharmacists felt that the emphasis was placed on the flow of patients to and from hospital and that if they participated in the WR, this may reduce their ability to perform core tasks. Pharmacists’ role in undertaking medication histories and reconciliation of medicines on admission, and in facilitating safe medication use on discharge were seen as priorities that interfered with pharmacists’ ability to participate in the WR. Alternatively, some respondents who actively participated in WRs identified the efficiencies gained by regular participation which enabled them to undertake regular tasks like planning patients discharge and saving time on interventions by contributing to decision-making.

ID 50:“The pressures of needing to discharge patients (usually at the same time that ward rounds are going) to obtain the bed for the next patient are one of the main factors that prevent your ability to attend ward rounds … ”

ID 27: “When I was on cardiology, I was able to regularly attend ward round. This helps me to identify any issues with patient’s medications and alert the team promptly. This also allowed better patient involvement in their medication decision making as ward round is usually conducted in patient’s room. [The] team was able to raise issues directly and timely to me and helped with better workflow in terms of prioritization. I was also able to build a better relationship with the team … I was seemingly more involved.”

Respondents also indicated that the other members of the healthcare team need to be aware that the participation of pharmacists in the WR may delay actioning of other activities. Some clinical pharmacists stated that during the WR they often get interrupted by the paging system or other members of the healthcare team requesting them to undertake other clinical activities which hinders the clinical pharmacist from participating in the WR in its entirety.

ID 50:“Everyone knows that pharmacists have the ability to contribute significantly to ward rounds and improve medication safety. However this is not always possible due to the organizational pressures of the hospital system, of which a priority is bed turn over. This means that others (i.e. NUMS [nurse unit manager], nurses, executive) place a large emphasis on the patient being discharged as soon as possible, of which they see as a priority for the pharmacist (perception is that their priority should be our priority) … ”

ID 48: I am more likely to participate in the WR if … “there is due consideration from nursing staff that it may delay preparing discharge medications for other patients”

ID 81: I am more likely to participate in the WR if “ … The ward staff are aware that I cannot attend to non-urgent matters during ward rounds.”

Survey respondents highlighted that working in either a unit or team-based service compared to a ward-based service can influence their ability to participate in WR. In a unit or team-based service, the clinical pharmacist is responsible for patients cared for by a particular clinical (medical) team. Patients may be admitted across several wards but are all cared for by the same clinical team. In contrast, pharmacists required to provide a ward-based service are responsible for caring for all patients on a particular ward. These patients are likely to be cared for by several different medical teams or units. Respondents highlighted that when they are required to provide a ward-based clinical pharmacy service, there may be multiple WR occurring simultaneously creating a barrier to their participation on WR.

ID 93: “Operating [on] a ward based service is not conducive to a ward round … the ward I’m currently on is home to 5 teams … ”

The need for a manageable workload is often intertwined with the need for dedicated support to complete other clinical or non-clinical activities and the need for resources to allow for proactive WR participation. Support in terms of physical resources such as access to charts and blood results and staffing (including utilizing the pharmacy assistant workforce) was mentioned by participants.

ID 125: “ … .Pharmacists on the AMU [Acute Medical Unit] ward round allow for early medication review in consultation with the medical team, so other clinical pharmacists within the pod are often able to assist with sharing ward jobs to enable ward round attendance”

ID 135: “ … Not enough pharmacy technician support to allow pharmacists to do things such as ward rounds”

ID 107: “Definitely having access to charts, notes, pathology etc [sic] during round. Otherwise I find myself leaving round(s) regularly to look things up, then join back in.”

The participants also emphasized the importance of having flexible working hours to allow them to participate in WRs when they are not conducted during the usual business hours of the clinical pharmacists. Respondents indicated that there needs to be flexibility from pharmacy management to support clinical pharmacists to change their working hours to facilitate WR participation, when they occur outside of business hours.

ID 83: I am more likely to participate if “there was more time – if I got to start work earlier or extend my morning working hours.”

The clinical pharmacists also stated the importance of having training to undertake a WR. Respondents stated that training relating to duties and expectations of clinical pharmacists in a WR would increase their confidence in participating in WRs.

ID 31: I am more likely to participate in the ward round if … “I had experienced a ward round during internship, I obtained training on what to expect, what activities I can do, and what I can contribute during a ward round and I could shadow another pharmacist attending ward round to observe their contributions … ”

Theme 2: ward round structure

There are aspects of the WR which influence participation by clinical pharmacists. This theme identified that timing, participants, activities undertaken on the round, inconsistencies in structure and how long the WR go for all influence pharmacists’ motivation to participate in WR.

Some respondents attributed the lack of WR participation to the large number of people already participating in the WR. They also noted that the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic further physically limited the number of people able to participate in the WR.

ID 179: “Further difficulties such as room capacity limits during COVID-19 pandemic further discourage attendance by more people than the physician, registrar, intern, patient nurse and Nurse In Charge.”

ID 80: “ … [A barrier to ward round participation is the] size of the ward round group: consultant + registrar + nurse + resident medical officer + pharmacist + med student/s can become prohibitive. I may not be able to get into patient room.”

Respondents also felt that their ability to participate in WRs depended on the length of the WR. Some respondents felt that WRs can take up a large amount of time that could have been better utilized in other clinical activities, creating a barrier to WR participation. Some clinical pharmacists also felt that WRs are utilized to address non-medication related issues and therefore WR may not be a useful vehicle for interprofessional collaboration for medication-related matters.

ID 60: “I rarely participate in the ward round. Often they go for a long period of the day.”

ID 129: “ … Rambling ward rounds that … spend a lot of time on patient care matter[s] not related to drug therapy”

Some clinical pharmacists also felt that when the WR did not start at a specified or consistent time, this presented a barrier to their participation. The start time of WR often depended on the availability of the consultants or specialists which could be variable.

ID 35:“ … my current ward starts their rounds at very odd times which makes it difficult to join … ”

ID 31: “ … In addition, the rotating consultants have different start times and … this can vary depending on the [consultant] … .”

ID 29: “ … In private sector, each patient may have a different admitting doctor [consultant/specialist], and they may choose to attend the hospital at any time…”

In contrast, other respondents reported that regular pharmacist participation in WR may influence the structure of the rounds, with a bigger focus on medicines review and decision-making around medicines in the pharmacist’s presence.

ID 98: “ … Being on the ward round allows you to help be a key part of the decision-making team, gives you the chance to be proactive, push deprescribing opportunities at the appropriate time … They are valuable experiences for all involved (even consultants sometimes say this) … ”

Theme 3: pharmacist’s capabilities

Capabilities such as clinical knowledge and skill and their associated confidence and experience had an important influence on a clinical pharmacist’s participation in WRs. Some clinical pharmacists reported that it was their own lack of confidence in their skills and knowledge that was a barrier to them participating in a WR. They noted that it takes time to develop these skills, and so newly registered pharmacists may not feel confident to participate in WRs.

ID 56: I am more likely to participate in the ward round if “I had more confidence in my clinical knowledge and skills to contribute to the ward round discussion (as a newly registered pharmacist I am not yet confident) and this will come with continued practice and skill/knowledge development”

Whilst WRs can be seen as an opportunity to learn more about patients and develop clinical knowledge, there was a perception that pharmacists needed to have extensive knowledge of their patients as well as extensive clinical knowledge to make a meaningful contribution to patient care in the context of the interprofessional WR. ID 97: “I usually cover one day only so my lack of background knowledge of [patients] is low … ”

Participants also described that an enabler to WR participation was having previous experience in participating in WRs.

ID 165: “ … [When I was an intern], I had experienced oncology round[s] at [Australian hospital name]. I [then] set up the cardiology pharmacy service at the hospital [where I am currently working] and introduced pharmacists on ward rounds. In my experience, I have not had any issues [in participating in ward rounds].”

However, opposing views were also seen where participants who had previously participated in WRs did not continue participating in them. ID 146: “Occasionally as an intern when time permitted I attended ward rounds, this is the only time in my career that I have done so.”

ID 173: “I have mainly worked in oncology which is a highly specialized area therefore ward rounds have been a regular occurrence. When working in more general fields, I haven’t attended ward rounds as its not done in many hospitals in more general scope of practice”

Theme 4: culture

The clinical pharmacists emphasized that having an inter-professional and inter-dependent relationship with the medical team and other clinicians can impact upon their subsequent decision on whether to participate in WRs. A negative experience with members of the treating team or a team that is not inclusive and supportive of clinical pharmacist’s participation was seen to negatively impact upon their WR participation.

ID 53: “In the past, a good relationship with the treating team has provided ease of attendance at ward rounds and more fulfilling experiences at the ward round. They are more likely to advise when the round is starting if they know who you are and where you are, and if they have found the pharmacist useful in the past.”

ID 100: “ … some clinicians within the team supportive of pharmacist attendance, while others are not, & it depends who is on rotation on the inpatient unit at the time.”

The expectation and encouragement of pharmacists to participate in WRs was identified as an enabler for clinical pharmacist’s participation in WRs. The participants identified that expectation and encouragement to participate in WRs can arise from both the pharmacy management and/or the broader clinical team.

ID 90: “If consultants expect pharmacists to be on the ward round, then it is more likely to happen”

ID 156: I am more likely to participate in WRs if “ … I am encouraged [and] requested by the medical team [to participate in the ward round].”

ID 149: I am more likely to participate in WRs if … “ … it is made mandatory or encouraged by my [pharmacy] team leader”

Some participants also recognized the need for the clinicians and the clinical pharmacist in the team to understand the roles and contributions that each team member can contribute to patient care during the WR. The participants highlighted that when there was no clear role or knowledge of how the clinical pharmacist would contribute in a WR, they were less likely to participate in WRs.

ID 62: “When I started working in this hospital the training provided was limited and the medical teams do not seem to acknowledge that pharmacists can contribute to their ward rounds”

When asked about previous workplace experiences that hinders WR participation participant one pharmacist (ID: 100) stated: “Clinicians who make it known they feel uncomfortable with a pharmacist potentially questioning or contributing information in front of a patient.”

Where departments have a culture supportive of clinical pharmacist contribution to WRs, this was supported by a consistent WR structure that enabled pharmacist participation, and a clinical pharmacy service that enabled the pharmacist to participate in the WR.

Theme 5: value

When the value of a clinical pharmacist’s contribution in the WR is recognized by the medical, nursing, and pharmacy team, this enables a culture that supports WR participation by clinical pharmacists. Pharmacists felt that this created an expectation that they contribute, and team members encouraged their contribution to WRs. Many of the respondents reported a reactive role, responding and waiting to be asked to join the WR team as opposed to being proactive and self-recognizing their value in the WR.

ID 35: “ … They also don’t really involve any pharmacy input and on the occasion, they do need pharmacy, they will find you and ask after the round”

ID 103: “- A consultant who is welcoming and open to pharmacist input – At a previous workplace, rounding with the medical team was an expected part of daily activities – Not being interrupted with other work activities (e.g. supply request, discharge work)…”

The clinical pharmacists also emphasized that if their contribution through WR participation was valued by the pharmacy management team by demonstrating support through providing adequate pharmacists and structuring the clinical pharmacy service through flexible working hours, this enabled WR participation. ID 101: I am more likely to participate in the WR if … “My role within the round is recognized and valued and therefore staffed accordingly”

ID 17: “I don’t have protected time for ward rounds; general medicine has a daily multidisciplinary round that is protected and so I will attend that, but that’s mostly as a safety check and for discharge planning”

Participants also highlighted that the participating clinical pharmacist needed to understand how they can be of value to the WR team and have an awareness of how they can contribute during the WR. If the participation in WRs was not seen as a good use of time by the clinical pharmacists, participation in the WR was negatively impacted.

ID 123: “I don’t see ward round as a primary role of the pharmacist, it can be added to our tasks if time persists but should not be a main focus, nor should it take away from our primary duties. There (are) studies to suggest that ward round reduced costs and reduce times to interventions, though this is not comparable to the impact appropriate counselling and discharges can have on patients.”

Discussion

Interpretation of findings

Whilst prior studies have explored the factors affecting participation in ward rounds from a general team perspective (Bharwani et al., Citation2012; Costa et al., Citation2014; Prystajecky et al., Citation2017), this is the first qualitative study that explores this topic with a focus on perspectives from clinical pharmacists. This study adds to the international literature by identifying the five key themes that impact WR participation by clinical pharmacists: 1) Clinical pharmacy service structure, (2) Ward round structure, (3) Pharmacist’s capabilities, (4) Culture, and (5) Value. In a context where pharmacist input in WR is valued, the alignment of clinical pharmacy service and WR structure can enable WR participation. A culture of pharmacist contribution to WR, supported by a consistent WR structure with flexible delivery of clinical pharmacy services also enables pharmacists’ participation in WR. Pharmacists also need to self-recognize their value in WR. When pharmacists do not value their input into WR, their participation is not prioritized. If clinical pharmacists recognized the value of being present at the time of decision-making, this might influence their motivation to participate in a WR. If pharmacists can use the interprofessional WR as a platform from which they can undertake many of their clinical pharmacist activities, such as clinical review, therapeutic drug monitoring, and discharge planning, they may see more value in their participation. This research demonstrated that pharmacists lack of confidence in their clinical knowledge was a barrier to participation in ward rounds, yet those who participated in WR indicated that WR participation was a facilitator of knowledge growth and application.

Our study findings suggest that a trusting, working-relationship, or bidirectional interprofessional relationship was displayed in the responses of some clinical pharmacists. For example, participant ID 53 stated that “a good relationship with the treating team has provided ease of attendance at ward rounds and more fulfilling experiences at the ward round. They are more likely to advise when the round is starting if they know who you are and where you are, and if they have found the pharmacist useful in the past.” In this example, the clinical pharmacist and the broader healthcare team were in a mutually beneficial circumstance where there was value added to the medical practice with the addition of a pharmacy perspective in a WR. A bidirectional interprofessional relationship occurred as the clinical pharmacist was working in stage 4 of the model where both the clinical pharmacists and the healthcare team displayed interdependence (Brock & Doucette, Citation2003; Doucette et al., Citation2005). However, a unidirectional interprofessional relationship was also displayed in responses of some of the clinical pharmacists in this study. For example, ID participant 156 stated “I am more likely to participate in WRs if … I am encouraged [and] requested by the medical team.” This can be closely related to stage 0 of the collaborative working relationship model where the exchanges with the broader healthcare team are minimal, discrete, and reactive.

Doucette et al. also state that as pharmacist’s and physician practitioners begin working together, they may hold expectations of each other from their previous experiences (Doucette et al., Citation2005). However, as the physician evaluates pharmacist’s abilities and the quality of their recommendation and vice versa and both parties jointly determine their specific roles, the collaboration is more likely to reach the stage of consistent inter-professional practice and inter-dependence for effective medication management (Doucette et al., Citation2005). This was reflected in our findings, particularly in relation to theme (5) value where participants described that they felt there was an encouragement and expectation to contribute in the WR when the value was recognized by themselves as well as the medical and nursing staff.

Some clinical pharmacists in this study perceived that they needed to attain more therapeutic knowledge to actively participate in inter-professional activities like WR. However, it was also noted by respondents that skills, knowledge, and confidence will develop with experience, and may be facilitated by the WR environment. This can be related to the collaborative working relationship model where it recommends that the pharmacists proactively begin engaging with the physicians and be the initiator of interprofessional communication, increasing the visibility of the profession (Brock & Doucette, Citation2003). A practice review paper exploring the characteristics associated with pharmacists and their subsequent influence on practice change also suggested that the lack of experience or confidence in their skills is often due to their lack of experience in applying their existing knowledge in novel or unfamiliar situations rather than their actual lack of preparedness (Rosenthal et al., Citation2010).

The “Clinical pharmacy service structure” and the “Ward round structure” are contextual factors that can influence WR participation. The WR is an opportunity for interprofessional practice and factors such as inflexibility of working hours for clinical pharmacists to participate in WRs, lack of staff, and inconsistent WR time with no prior notice of when the WR is occurring can limit the interaction of the WR team with the pharmacists and vice versa. Prior research has shown that the context of systems in which the clinical pharmacist’s work such as the proximity of practices (e.g. getting called away from the WR to attend to the pager, undertaking other tasks during WR, or dispensary duties during interprofessional activity time) can be a driver affecting a cultural shift where there is a commitment to collaborative practices like interprofessional WR (Zillich et al., Citation2004). Workloads, workflows and other organizational features can determine whether there are opportunities for the clinical pharmacist to be present with the broader healthcare team, expanding the professional relationship. Being physically “absent” from the interprofessional activities due to the contextual factors can limit the pharmacist’s opportunities for proactive exchanges with the physicians (Brock & Doucette, Citation2003). Other contextual drivers identified from this study include the environmental barriers such as COVID-19 preventing this collaboration due to the physical limit in numbers.

Similar themes, consistent with this study, were also seen in a study conducted in Poland, which used semi-structured interviews and had the aim to understand pharmacists’ and physicians’ intentions regarding interprofessional collaboration (Zielińska-Tomczak et al., Citation2021). They also identified that the previous experiences of interprofessional collaboration and lack of understanding of the competencies of other professions influenced the physicians’ and pharmacists’ attitudes in developing a partnership in the future (Zielińska-Tomczak et al., Citation2021). The results of this study are also in keeping with other studies conducted in the United Arab Emirates, the United States of America, Switzerland, Canada, and Australia exploring views and factors influencing interprofessional collaboration which identified that the lack of understanding each other’s professional abilities; workload; clinical pharmacists having the appropriate knowledge and skills to respond to queries; and having dedicated support in the form of additional staffing can influence the inter-professional collaboration in a hospital setting (Béchet et al., Citation2016; Giannitrapani et al., Citation2018; Hasan et al., Citation2018; Makowsky et al., Citation2009; Wilson et al., Citation2016).

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this is the first study looking into factors impacting clinical pharmacist’s participation in hospital WRs. A strength of this study is that the raw free-text responses were independently coded by two researchers, adding to the depth of codes and themes constructed. As the survey was anonymous, online, and self-administered, it is likely that the participants provided honest responses. A potential limitation is that this study was undertaken at the peak time for omicron coronavirus variant and WR structures may have been impacted by COVID-19 specific practice changes. Given this was an anonymous survey, there was no opportunity to further elaborate or clarify responses with the participants. This study also does not assess actual staffing and workload levels, it only provides the perception of the clinical pharmacists.

Conclusion

Findings from our study indicate that the five key themes that influence participation in the WR by clinical pharmacists are as follows: (1) Clinical pharmacy service structure, (2) Ward round structure, (3) Pharmacist’s capabilities, (4) Culture, and (5) Value. Interventions targeting these themes and their subsequent impact on participation in WR should be further explored. Being physically “absent” from the WR due to workload, workflow, and self-perception of the need for extensive clinical knowledge can limit opportunities for pharmacists to begin proactive exchanges with the physicians to improve patient care outcomes. Bidirectional communication between the interprofessional team and the pharmacists, where there is mutual understanding and co-construction of each individual’s role in the WR facilitates consistent and inter-dependent collaboration for effective medication management.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (13.9 KB)Acknowledgments

Thank you to the professional body, SHPA for supporting this research by promoting the survey to their members. Most importantly, thank you to all the pharmacists that took the time to contribute to this research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, [DB] upon reasonable request.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2023.2289506.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Dona Babu

Dona Babu is a Doctor of Philosophy student at the University of South Australia. She is also a pharmacist at SA Pharmacy, the statewide public hospital pharmacy service in South Australia.

Sally Marotti

Sally Marotti is a pharmacist and adjunct clinical lecturer at The University of South Australia (UniSA). She is the lead pharmacist for education and research at SA Pharmacy, the statewide public hospital pharmacy service in South Australia.

Debra Rowett

Debra Rowett is a pharmacist and Professor of Pharmacy at the University of South Australia (UniSA), Director of the Drug and Therapeutics Information Service (DATIS) Southern Adelaide Local Health Network. Member of the Drug Utilization SubCommittee of the Australian Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee.

Renly Lim

Renly Lim is a pharmacist and Senior Research Fellow at the University of South Australia. She leads projects to improve medicine safety in Australia and internationally, and is passionate about public engagement to improve medicine use and health outcomes.

Alice Wisdom

Alice Wisdom is a pharmacist working within SA Pharmacy. She is the acting deputy director of pharmacy for medicines governance, mental health and research at Northern Adelaide Local Health Network (NALHN).

Lisa Kalisch Ellett

Lisa Kalisch Ellett is an Associate Professor in Pharmacy and Pharmacoepidemiology and Enterprise Fellow at the University of South Australia.

References

- Babu, D., Rowett, D., Lim, R., Marotti, S., Wisdom, A., & Ellett, L. K. (2023). Clinical pharmacists’ participation in ward rounds in hospitals: Responses from a national survey. International Journal of Pharmacy Practice, 31(4), 409–416. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijpp/riad028

- Béchet, C., Pichon, R., Giordan, A., & Bonnabry, P. (2016). Hospital pharmacists seen through the eyes of physicians: Qualitative semi-structured interviews. International Journal of Clinical Pharmacy, 38(6), 1483–1496. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-016-0395-1

- Bharwani, A. M., Harris, G. C., & Southwick, F. S. (2012). Perspective: A business school view of medical interprofessional rounds: Transforming rounding groups into rounding teams. Academic Medicine, 87(12), 1768–1771. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e318271f8da

- Bosma, B. E., van den Bemt, P., Melief, P., van Bommel, J., Tan, S. S., & Hunfeld, N. G. M. (2018). Pharmacist interventions during patient rounds in two intensive care units: Clinical and financial impact. The Netherlands Journal of Medicine, 76(3), 115–124.

- Brock, K. A., & Doucette, W. R. (2003). Collaborative working relationships between pharmacists and physicians: An exploratory study. Journal of the American Pharmaceutical Association, 44(3), 358–65. https://doi.org/10.1331/154434504323063995

- Bullock, B., Donovan, P., Mitchell, C., Whitty, J. A., & Coombes, I. (2019). The impact of a pharmacist on post-take ward round prescribing and medication appropriateness. International Journal of Clinical Pharmacy, 41(1), 65–73. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-018-0775-9

- Bullock, B., Donovan, P. J., Mitchell, C., Whitty, J. A., & Coombes, I. (2020). The impact of a post-take ward round pharmacist on the risk score and enactment of medication-related recommendations. Pharmacy (Basel), 8(1). https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy8010023

- Carter, N., Bryant-Lukosius, D., DiCenso, A., Blythe, J., & Neville, A. J. (2014). The use of triangulation in qualitative research. Oncology Nursing Forum, 41(5), 545–547. https://doi.org/10.1188/14.ONF.545-547

- Clarke, V., & Braun, V. (2017). Thematic analysis. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 12(3), 297–298. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2016.1262613

- Costa, D. K., Barg, F. K., Asch, D. A., & Kahn, J. M. (2014). Facilitators of an interprofessional approach to care in medical and mixed medical/surgical ICUs: A multicenter qualitative study. Research in Nursing & Health, 37(4), 326–335. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.21607

- Crabtree, B., Miller WLCrabtree, B., & Miller, W. (1999). Using codes and code manuals: A template organizing style of interpretation doing qualitative research. Sage Publications.

- Doucette, W. R., Nevins, J., & McDonough, R. P. (2005). Factors affecting collaborative care between pharmacists and physicians. Research in Social & Administrative Pharmacy: RSAP, 1(4), 565–578. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2005.09.005

- Giannitrapani, K. F., Glassman, P. A., Vang, D., McKelvey, J. C., Thomas Day, R., Dobscha, S. K., & Lorenz, K. A. (2018). Expanding the role of clinical pharmacists on interdisciplinary primary care teams for chronic pain and opioid management. BMC Family Practice, 19(1), 107–107. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-018-0783-9

- Hasan, S., Stewart, K., Chapman, C. B., & Kong, D. C. M. (2018). Physicians’ perspectives of pharmacist-physician collaboration in the United Arab Emirates: Findings from an exploratory study. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 32(5), 566–574. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2018.1452726

- Kang, M., Kim, A., Cho, Y., Kim, H., Lee, H., Yu, Y. J., Lee, H., Park, K. J., & Pyoung Park, H. (2013). Effect of clinical pharmacist interventions on prevention of adverse drug events in surgical intensive care unit. Acute and Critical Care, 28(1), 17–24. https://doi.org/10.4266/kjccm.2013.28.1.17

- Kucukarslan, S. N., Peters, M., Mlynarek, M., & Nafziger, D. A. (2003). Pharmacists on rounding teams reduce preventable adverse drug events in hospital general Medicine units. Archives of Internal Medicine, 163(17), 2014–2018. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.163.17.2014

- Langlois, S. (2020a). Collective competence: Moving from individual to collaborative expertise. Perspectives on Medical Education.

- Langlois, S. (2020b). Collective competence: Moving from individual to collaborative expertise. Perspectives on Medical Education, 9(2), 71–73. https://doi.org/10.1007/S40037-020-00575-3

- Leape, L. L., Cullen, D. J., Clapp, M. D., Burdick, E., Demonaco, H. J., Erickson, J. I., & Bates, D. W. (1999). Pharmacist participation on physician rounds and adverse drug events in the intensive care unit. JAMA, 282(3), 267–70. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.282.3.267

- Li, X., Huo, H., Kong, W., Li, F., & Wang, J. (2014). Physicians’ perceptions and attitudes toward clinical pharmacy services in urban general hospitals in China. International Journal of Clinical Pharmacy, 36(2), 443–450. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-014-9919-8

- Makowsky, M. J., Schindel, T. J., Rosenthal, M., Campbell, K., Tsuyuki, R. T., & Madill, H. M. (2009). Collaboration between pharmacists, physicians and nurse practitioners: A qualitative investigation of working relationships in the inpatient medical setting. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 23(2), 169–184. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820802602552

- McKillip, J., Moirs, K., & Cervenka, C. (1992). Asking open-ended consumer questions to aid program planning: Variations in question format and length. Evaluation and Program Planning, 15(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/0149-7189(92)90054-X

- Moffatt, S., White, M., Mackintosh, J., & Howel, D. (2006). Using quantitative and qualitative data in health services research – what happens when mixed method findings conflict? [ISRCTN61522618]. BMC Health Services Research, 6(1), 28. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-6-28

- Nguyen-Thi, H.-Y., Nguyen-Ngoc, T.-T., Do-Tran, M.-T., Do, D. V., Pham, L. D., & Le, N. D. T. (2021). Job satisfaction of clinical pharmacists and clinical pharmacy activities implemented at ho chi minh city. Vietnam PLoS One, 16(1), e0245537. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0245537

- Nowell, L. S., Norris, J. M., White, D. E., & Moules, N. J. (2017). Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 16(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406917733847

- Perversi, P., Yearwood, J., Bellucci, E., Stranieri, A., Warren, J., Burstein, F., Mays, H., & Wolff, A. (2018). Exploring reasoning mechanisms in ward rounds: A critical realist multiple case study. BMC Health Services Research, 18(1), 643. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-3446-6

- Pratt, N. L., Kalisch Ellett, L. M., Sluggett, J. K., Ramsay, E. N., Kerr, M., LeBlanc, V. T., Barratt, J. D., & Roughead, E. E. (2015). Commitment questions targeting patients promotes uptake of under-used health services: Findings from a national quality improvement program in Australia (Vol. 145). Social Science & Medicine.

- Prystajecky, M., Lee, T., Abonyi, S., Perry, R., & Ward, H. (2017). A case study of healthcare providers’ goals during interprofessional rounds. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 31(4), 463–469. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2017.1306497

- Rosenthal, M., Austin, Z., & Tsuyuki, R. T. (2010). Are pharmacists the ultimate barrier to pharmacy practice change? Canadian Pharmacists Journal / Revue des Pharmaciens du Canada, 143(1), 37–42. https://doi.org/10.3821/1913-701X-143.1.37

- SHPA. (2013). Standards of practice for clinical activities. Journal of Pharmacy Practice and Research, 43(2), 43–46.

- Sofaer, S. (1999). Qualitative methods: What are they and why use them? Health Services Research, 34(5 Pt 2), 1101–1118.

- Surani, S., & Varon, J. (2015). To round or not to round: That is the question! Hospital Practice, 43(5), 268–269. https://doi.org/10.1080/21548331.2015.1109455

- Walton, V., Hogden, A., Long, J. C., Johnson, J., & Greenfield, D. (2020). Exploring interdisciplinary teamwork to support effective ward rounds. International Journal of Health Care Quality Assurance, 33(4–5), 373–387. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJHCQA-10-2019-0178

- Wilson, A. J., Palmer, L., Levett-Jones, T., Gilligan, C., & Outram, S. (2016). Interprofessional collaborative practice for medication safety: Nursing, pharmacy, and medical graduates’ experiences and perspectives. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 30(5), 649–654. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2016.1191450

- York, G. S., Churchman, R., Woodard, B., Wainright, C., & Rau-Foster, M. (2011). Free-text comments: Understanding the value in family member descriptions of hospice caregiver relationships. American Journal of Hospice & Palliative Medicine®, 29(2), 98–105. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909111409564

- Zielińska-Tomczak, Ł., Cerbin-Koczorowska, M., Przymuszała, P., & Marciniak, R. (2021). How to effectively promote interprofessional collaboration? – a qualitative study on physicians’ and pharmacists’ perspectives driven by the theory of planned behavior. BMC Health Services Research, 21(1), 1–903. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-06903-5

- Zillich, A. J., McDonough, R. P., Carter, B. L., & Doucette, W. R. (2004). Influential characteristics of physician/pharmacist collaborative relationships. The Annals of Pharmacotherapy, 38(5), 764–770. https://doi.org/10.1345/aph.1D419