ABSTRACT

Healthcare is often conducted by interprofessional teams. Research has shown that diverse groups with their own terminology and culture greatly influence collaboration and patient safety. Previous studies have focused on interhospital teams, and very little attention has been paid to team collaboration between intrahospital and prehospital care. Addressing this gap, the current study simulated a common and time-critical event for ambulance nurses (AN) that also required contact with a stroke specialist in a hospital. Today such consultations are usually conducted over the phone, this simulation added a video stream from the ambulance to the neurologist on call. The aim of this study was to explore interprofessional collaboration between AN’s and neurologists when introducing video-support in the prehospital stroke chain of care. The study took place in Western Sweden. The simulated sessions were video recorded, and the participants were interviewed after the simulation. The results indicate that video has a significant impact on collaboration and can help to facilitate better understanding among different professional groups. The participants found the video to be a valuable complement to verbal information. The result also showed challenges in the form of a loss of patient focused care. Both ANs and neurologists saw the video as benefiting patient safety.

Introduction

Healthcare has undergone numerous changes and become increasingly specialized; ambulance services are no exception. Simultaneously, technical development enables delivery of care under different prerequisites that affect not only the patients but also the work and working environment of healthcare staff. In Sweden, where this study was conducted, each ambulance is required to be staffed with a minimum of one licensed healthcare professional, often a registered nurse, who typically holds a one-year specialization in ambulance care and is designated as an “Ambulance Nurse” (AN) (Lindström et al., Citation2015). Today, ANs are expected to make complex assessments based on scant information and make crucial decisions regarding the next step in the chain of care (Bruce & Suserud, Citation2005). These decisions may require assessment, advice, or authorization by a specialist, (e.g., a cardiologist, neurologist, etc.). Today these are conducted by telephone. According to the clinical guidelines for ANs, one situation where telephone consultations are necessary is in the case of a suspected stroke (FLISA, Citation2017).

Stroke is a condition that affects a large number of patients worldwide and is one of the most time-critical events for ANs to handle. In the region where this study was conducted, guidelines state that if ANs suspect a stroke, the patient should be transported to the nearest local hospital for assessment. Subsequently, if the computed tomography angiography (CTA) scan at the local hospital shows thrombosis, medical treatment is initiated to resolve the clot (thrombolysis). However, if the clot is in a large vessel, the patient should be transported to a regional stroke center for mechanical clot removal (thrombectomy). The local hospital calls the neurologist at the regional stroke center, who decides whether the patient is a thrombectomy candidate. If so, the patient is transported there by ambulance (Andersson et al., Citation2018; Magnusson et al., Citation2021). Overall, the entire process, from identifying symptoms to reaching the right level of care, involves several actors and requires both time and resources. In the region where this study was conducted, this process could, depending on where the patient is located, in all take several hours. At the same time, the outcome of a stroke patient is directly determined by the time from symptom onset to right treatment (Andersson et al., Citation2018). To address this, the study proposes the implementation of direct video consultation between ambulance personnel and neurologists at regional stroke centers, aiming to expedite patient assessment and optimize prehospital stroke care delivery. Real-life simulations, conducted to prepare for this implementation, have shed light on the potential organizational and interprofessional impacts of integrating video-supported collaboration into prehospital stroke management.

There are however well-know information gaps between prehospital and intrahospital settings, partly due to context, work culture differences and professional relationships (Troyer & Brady, Citation2020; Wood et al., Citation2015). Video introduces a new type of collaboration that, as suggested by previous work, may affect the organization of care and how different healthcare professionals interact and communicate (Johansson et al., Citation2019; Neale et al., Citation2004). Despite the recognized potential benefits, there remains a significant gap in research focusing specifically on the challenges and implications of video-supported collaboration within ambulance services. This study aims to explore the impact of video support on remote interprofessional collaboration and teamwork during simulated stroke scenarios within the prehospital context. The findings are expected to provide valuable insights for the successful implementation of video consultation in prehospital stroke care, thereby enhancing the effectiveness of ambulance services in addressing time-sensitive medical emergencies.

Background

Video in prehospital care

Research related to video support in an ambulance context is scarce. Much of the work focuses on different types of technologies, its functionality, properties, or feasibility. There is a wide range of cameras and technologies that have been tested, e.g. tablets, mobile phones, cameras installed in the ambulance, head cameras (Janerka et al., Citation2023) and smart glasses (Ishikawa et al., Citation2022; Zhang et al., Citation2022). The common thread among these studies is their conclusion verifying that the technology indeed works from a technical perspective (Barrett et al., Citation2017; Johansson et al., Citation2019). Previous work specifically about remote stroke support has shown that assessment by a remote neurologist is both reliable and accurate (Wu et al., Citation2017). Other studies have focused on consultation between a neurologist in one hospital and a stroke neurologist in a different location to validate the use of a smartphone application for consultation between hospitals (Sheila et al., Citation2020; Takao et al., Citation2021). A limited number of small-scale studies have investigated the feasibility of video calls in stroke cases between ambulance personnel and neurologists, with observable impacts on local stroke care. They also suggest the potential for ambulance personnel and neurologists to form a collaborative care team during the early stages of patient care, although stress the need for broader implementation and further investigation on a larger scale to verify this (Johansson et al., Citation2019; Magnusson et al., Citation2022; Wireklint Sundström et al., Citation2017). One study identified that when consulting with a remote neurologist ANs felt that video improved their existing processes and increased their confidence in decision-making, while neurologists instead experienced the video as added pressure and workload (Ramsay et al., Citation2022).

There are also studies investigating video between ambulance personnel and physicians in other types of patient cases and situations, including trauma patients (Charash et al., Citation2011) and patients with heart diseases (Cheung et al., Citation1998). Early simulation-based studies (Maurin Söderholm, Citation2013; Söderholm & Sonnenwald, Citation2010; Söderholm et al., Citation2008) on video-supported trauma management concluding that the use of video introduces a new way of working that functions on both a professional and an organizational level. When video consultation between ambulance personnel and regional medical support (RMS) was used in cases involving patients eligible for self-care, evaluation results showed that the use of video helped reach a consensus on the patient’s needs and increased ANs experience of patient safety (Vicente et al., Citation2020, Citation2021).

Overall, there is a consensus among previous work regarding the potential and usefulness of prehospital video contributing to earlier assessment of the patient; directing the patient to the appropriate level of care and health facility; and preparations for when/if the patient arrives at the hospital. Many studies are pilot studies investigating feasibility and effectiveness regarding resources, costs and technology; hence, two overall knowledge gaps stand out specifically regarding: 1) large-scale implementations providing basis for evaluations of patient outcomes; and 2) explorations on how video consultation affects and is affected by the healthcare professionals that are expected to use it and work together in this context, sometimes in completely new professional configurations and couplings.

Remote collaboration across teams and professions

Healthcare today is almost always conducted by interprofessional teams. In this context, research has shown that deficiencies in communication and interprofessional collaboration often endanger patient safety. This implies that improvement in teamwork can lead to significant benefits for patient safety. Apart from the ability to work together, creating strong teams requires an understanding of the knowledge and experience of the individuals involved (Salas et al., Citation2005; Weller et al., Citation2014). Different professionals comprising a healthcare team all have their own ways of communicating, and as a result of which they may not always fully understand each other’s priorities, roles, and working conditions. This can lead to challenges pertaining to interprofessional collaboration (Ann, Citation2012; Hall, Citation2005; Rodehorst et al., Citation2005). According to Neale, Carrol, and Rosson (Neale et al., Citation2004), collaboration can be viewed as a pyramid consisting of five levels. The base of the pyramid represents contextual factors, which are the foundation for all collaboration. Understanding each other’s contexts is critical for interprofessional collaboration. The processes illustrated in the model, from the bottom to the top, are lightweight interaction, information sharing, coordination, collaboration, and cooperation in the model. The higher-up in the pyramid, the more tightly coupled the collaboration and the greater the requirements for communication to enable effective collaboration. Today, consultations between ANs and a neurologist are conducted over the phone. The ANs first report their assessment and the patient’s symptoms. After which the neurologist often asks a few complementary questions. If needed, the primary neurologist brings the attending neurologist on call for additional advice before they (the neurologists) decide the next step for the patient. Subsequently, they inform the AN about their decision. According to Neale and Carrol’s (2004) theory of computer-supported collaboration, this interaction falls under information sharing, which is characterized by communication of an informed and acknowledged nature. In information sharing, the parties involved exchange the necessary information to decide the next step in the chain of care (Neale et al., Citation2004). Individuals involved in such a situation (here, the AN and neurologist) are loosely coupled, in the meaning that although they are accustomed to consulting other professionals, they are both specialists in their field who are familiar with making decisions and performing patient care without consulting others (Pinelle & Gutwin, Citation2006).

For a team to be formed and be able to work together, members must also maintain a certain level of trust among themselves (Ann, Citation2012; D’Amour et al., Citation2005). Many healthcare teams are ad-hoc, temporary teams whose members may or may not have met before the upcoming collaboration. Such teams often face obstacles that they need to overcome (Hautz et al., Citation2020; White et al., Citation2018). Studies have identified hierarchical and communicational barriers between nurses and who work in the same ward, or even the same operation theater (Lingard et al., Citation2004; O’Leary et al., Citation2010). Furthermore, the professional comprising a healthcare team often have different prerequisites for autonomy. In this context, the term professional discretion̕ refers to the ability to make decisions in different situations based on one’s own judgment. Professional discretion also accounts for the possibility of exercising power in everyday work and the differences between different professional groups (Molander et al., Citation2012). The different professional groups considered in this study operate in different organizational contexts that possibly affect their level of influence and liberty to make their own decisions (Evetts, Citation2011). This study includes physicians, who are well acquainted with exercising a prominent level of professional discretion and working closely with nurses in the stroke ward, but under different conditions with respect to hierarchy and professional discretion in the context of ANs. On the other hand, this study involves ANs, who often work independently in the field and exercise a significant level of professional discretion in their everyday work.

Although, previous research has studied different constellations of healthcare teams, intrahospital or prehospital teams located at an injury site, the literature on interprofessional collaboration between AN and hospital personnel is limited, and even more so when it comes to using video support. Considering that interprofessional collaboration can be challenging even when participants are “closer” both physically and professionally than in this set-up, it is crucial to identify, understand and address barriers, challenges, and negative implications as early as possible in the video implementation process. Acceptance and positive effects then have the potential to improve learning, decision-making, patient outcomes, resource allocation, and the overall effectiveness of EMS.

The prerequisite for collaboration between neurologists and ANs today is that they practice different professions, which are characterized by various levels of education, specialization, culture, and majors. They work under different conditions, and they may never see each other face to-face or one’s working environment. These circumstances are likely to be marked by different uses of terminology to describe the same thing, thus creating hierarchical challenges. To make things more difficult, different professionals might need to follow different guidelines, and both have prominent levels of professional discretion. To top it all off, there is a patient in the ambulance probably suffering from a time-critical event.

Aim and research questions

The aim of this study was to explore interprofessional collaboration between ANs and neurologists when introducing video support in the prehospital stroke chain of care. The current study specifically seeks to address the following questions:

What are the potential benefits and challenges of using video?

How does this new way of working affect collaboration and teamwork among different professional roles?

How is communication between professionals affected by using video in consultation?

What are the implications of using video-consultations for patient care?

Methods

Study design

This study was conducted using contextualized real-life simulations and a mixed methods approach involving video recordings and interviews.

Simulations can facilitate research in contexts that are difficult to access due to their mobile, unpredictable, or unsafe characteristics. To explore the use of video consultation in the prehospital stroke process, we took resource to contextualized simulation scenarios (Andersson Hagiwara et al., Citation2019; Backlund et al., Citation2015; Engström et al., Citation2016). Real-life situations were recreated and re-enacted by participants, while the scenarios and environments were designed to be as realistic, engaging, and immersive as possible, with respect to locations, tools, technology, actors, and situations. To ensure this, we set up the simulations in real environments (e.g., a park bench, an office at a university, a real ambulance), used real equipment (e.g., complete bags, monitoring equipment, phones, etc.), included realistic actors (e.g., hired neurologists trained to be patient actors), and built in all the necessary information as well as ensured access to information infrastructure as would be normally available (e.g., access to the real on-call neurology center, phone numbers, access to spouse/family members, dispatch information, etc.).

Three cameras were installed in the ambulance to provide the remote neurologist with a live stream of the side, fisheye, and close-up views of the patient () The ambulance was equipped with a screen that mirrored the neurologist’s view so that the ANs could also look at what the neurologist was seeing. A consultation was initiated over the phone. The AN´s started the consultation with verbal information regarding the patient’s background vital signs and onset of symptoms. Subsequently, they proceeded to the video consultation and conducted the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) assessment in collaboration with the neurologist. The video was streamed separately from the phone call to ensure continuous communication even in the case of interruptions to video transmission.

Participants and setting

This study included eight ANs (paired as four teams) and four remote consulting neurologists, resulting in eight unique neurologist – AN pairings. The use of ANs mirrors the staffing in ambulances in Sweden, the teams are often consisting of two nurses where one or both have a specialization in ambulance care. Although some of the personnel are ambulance technicians (EMT) they are a minority group. Each team participated in two scenarios, one with a patient exhibiting severe stroke symptoms, case A and another with a patient showing more diffuse symptoms, case B. ANs were instructed to work as they normally would, with the biggest difference being making the call to the remote regional neurologist over video instead of only using telephone and calling the local hospital.

Data collection

All the scenarios were video-recorded, after which the audio from these video-consultations was transcribed. The consultations varied in length, in case A from 5 to 11,6 min with a mean time of 9,8 min, and in case B from just over 8 to 12,2 min with a mean time of 10,5 min. After the two scenarios were completed, each ambulance team, participated in a semi-structured interview. The interviews lasted between 28 and 50 min with a mean time of 37.5 min. The interviews commenced with inquiries concerning participants’ experiences with phone consultations to gain some background on what the participants perceive as the challenges in today’s consultations conducted via telephone and proceeded to investigate their views regarding using the video-system, how it would fit into their everyday work, and their perceptions of communication and collaboration with the neurologist. In addition, the participating neurologists were interviewed after the conclusion of the on-site simulations. The interviews were audio-recorded and later transcribed.

Data analysis

Sequential analysis was employed, beginning with a primary focus on analyzing the interview transcripts. This was supplemented with examinations of the video recordings and their corresponding transcripts.

Insights were drawn from the transcripts of the team interviews and interviews with the neurologists using thematic analysis (TA). The TA aims to find patterns in the data to identify themes, which refer to trends appearing in the data that are of interest in relation to the research question. To locate these themes authors of this study followed the steps proposed by Braun and Clarke (Citation2006), which first involves familiarizing oneself with the data noting down any interesting elements observed in it. The next step was to create initial codes, extract data from each interview, and organize the text into suitable groups. The researchers then moved to search for themes within these groups. The identified themes were then scrutinized and paired with other similar themes. Following this, the identified themes were named and defined accurately. The final step of TA procedure was to produce a report and apply the final adjustments (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). The data were analyzed following an inductive “bottom-up” approach. Trustworthiness was reinforced by two researchers analyzing the material and cross-referencing their findings.

The analysis of the video consultation transcripts and recordings were based on an approach in which the researchers repeatedly reviewed the video material. When similarities and differences started to emerge, they were first collated in a document and then further analyzed and integrated with the themes that had emerged from the interviews.

Quotes from transcripts are referred to as [T] or [N] denoting “Team” and “Neurologist” and their respective number, e.g. [T3] for Ambulance team 3 and [N1] for Neurologist 1.

Ethical considerations

According to the Ethical Review Act 2003:460 I Swedish law, the design of this study does not fall within the scope of research that requires ethical approval. The researchers of this study complied with the ethical guidelines according to the ethical principle described in the VMA Declaration of Helsinki (World Medical Association, Citation2022). The participants, who were recruited from the regional stroke center and from the ambulance district in question, were informed about the overall aim of the study and that their participation was entirely voluntary. Furthermore, all participants signed a written consent form. No risks to the participants in the study were identified.

Results

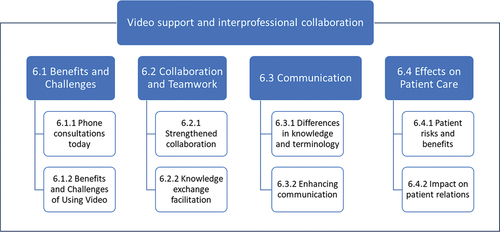

Overall, several types of benefits and challenges when using video are described throughout the results, e.g. in relation to how consultations are conducted today via telephone; and in relation to perceptions of video technology and technical set-up, professional collaboration, competence, and patient care. The results are organized according to four main themes (): benefits and challenges with current (phone based) consultations and video technology and set-up; how participants experienced collaboration and teamwork during the sessions; the communication during the sessions; and, how video consultations might affect patient care.

Benefits and challenges

Phone consultations today

Currently, consultations are conducted over the phone. Both the neurologists and the ANs expressed that this collaboration works well. In general, ANs appreciate having access to the support from the neurologist. This is shared by the neurologists who perceive telephone consultations in general as sufficient for making a decision.

Diverging expectations on professional role

Both AN and neurologist also identified situations in which they failed to fully comprehend the other’s point of view. Such situations can lead to friction between the neurologist and the AN making active collaboration and reaching a consensus about the patients’ continued care more difficult. The neurologists stated that they encountered difficulties in communicating effectively with ANs over the phone because although their competences often vary, the neurologist must rely on their verbal report to decide the course of the patient’s continued care. As a result, the neurologists expressed difficulties trusting the ANs’ competence and assessment of the patient when consulted over the phone, as an AN’s lack of experience can lead to conflicting interpretations of the patient’s status. The neurologists also conveyed facing challenges in establishing a balance in their communication, as they did not want to be perceived as too dominant. Furthermore, the neurologist’s perception of this communication largely depends on their perception of the AN’s articulation and competence.

If I then get the impression that the ambulance driver knows what it is, an inattention, and says clearly that “No, there are no such signs, she is fully attentive to the left and so on,” I also feel confident and sure. But if it is more like, “No, but, what do you mean? No, but I don’t know, maybe she is looking a bit more to the right than to the left,”and so on, then it immediately becomes much more difficult to communicate. N1

Meanwhile, the ANs drew on their experiences to remark that they sometimes find it difficult to get concrete decisions from the neurologist, as there are several actors involved in the overall decision-making process and logistics, e.g., the primary neurologist may initially make a decision, but they might change the decision on where to transport a patient after consulting with an attending on-call specialist. Such instances can lead to back-and-forth trips between hospitals before a final decision is made.

//You´ve made an assessment, and then you start … you talk [with the primary neurologist on call], and then “yes but go to [regional stroke center]” and then you´re almost there and then they call and say “no, we are reversing that, you can go back to [local hospital].”//And then we have lost all that time back and forth.//Both for the patient, but also for the ambulance that is occupied.//If we make a well-founded decision, talk to the neurologist [attending neurologist on call] right away [by video], and that neurologist made this assessment [go to the regional stroke center]//then they won’t back down and send us back. T3

Barriers to collaboration

When consulting on suspected stroke patients, neurologists feel a lack of understanding about the importance of patient’s actual symptoms as opposed to just the total score of the stroke assessment instrument used in the ambulance. Neurologists perceive ANs to be easily offended and reluctant to be corrected, often misunderstanding the reason for follow-up questions being asked. In cases where a neurologist requests to talk directly to the patient, it is not always well received by the AN, who might then be perceived as irritated by the neurologist

We need more details than just NIHSS scores//.//sometimes a difficulty arises when we then say, “Six points are not enough for me to know; you need to describe it a bit more.” Even then, it can be a bit like “What?” We have guidelines that, if it’s six points, to go to Sahlgrenska [regional stroke center].” N1

Meanwhile, the ANs expressed that they feel their abilities are being questioned by the neurologist in such circumstances.

//yes, but you get the feeling of “yes, but it can’t really be that bad, the patient can’t have such a high score.” Yes, but that’s,//how we have assessed it. T1

Benefits and challenges of using video

Video recordings and post-simulation interviews revealed challenges and benefits of using video for remote consultation of stroke patients. These pertain to consultation initiative, where it was not always clear who should take the lead in the consultation, and the technical set-up, where both ANs and neurologists speculated about the benefits of streaming the video both ways (in the simulation in this study, the neurologist could see the scene inside the ambulance and the AN, but the AN could not see the neurologist).

In all simulation scenarios, consultations began with ANs providing a brief report to the neurologist on the patient’s vital parameters, symptom onset, and information about the patient’s background. In half of the consultations, the AN ensured that the neurologist was able to see and listen clearly by inquiring about the sound and image quality. Furthermore, in most consultations, the AN handed over the initiative to the neurologist after conveying the initial report. However, some of the recordings also showed ANs briefly taking back the initiative on several occasions before the neurologist took control of the consultation again. Moreover, instances in which the ANs clearly interrupted the neurologist and took over the call were also observed.

From AN’s perspective, it was helpful to see the same view as the neurologist on the local screen, as it assisted them in adjusting the patient’s or their own position to not obscure the camera view. However, the ANs found it difficult to perform examinations while simultaneously communicating over the phone. The neurologists also expressed concerns regarding the practical implementation of video support for the attendant specialist on call as they could potentially in places that are not conductive to providing consultation when they receive a call from the AN.

//for those of us who are attending specialist neurologist on call, what do you do when you are cycling home from work and the phone rings? Should you stop cycling and connect? N1

From the neurologist’s perspective, streaming the video both ways seemed advantageous. However, the ANs did not express a direct need to see the neurologist, as they were accustomed to consulting over the phone.

I didn’t feel that I had any need for that (video both ways) T4

When asked about the video setup, the ANs speculated that being able to see the neurologist could contribute to a more equal conversation and help build a more personal relation with the neurologist. Furthermore, both the ANs and the neurologists found it beneficial if the neurologist were able to demonstrate the ways in which specific examinations should be carried out, especially those that are not usually performed by ANs.

On equal terms. Maybe. T1

Sometimes, I looked at [the video screen] myself to see the eye movement and such, is the patient facing the camera or is lying on their side a little bit or am I in front of something now that I’m sitting here, when I’m still in front [of the camera] and working. It gave a good idea of what was visible and what was not. T3

The potential of video consultation for collaboration and teamwork

The ANs and the neurologists expressed that using video was advantageous in terms of being able to receive and provide feedback. Both parties also saw the video as an opportunity to increase their understanding of each other’s professions. The neurologist got to see the examinations being carried out and rectify if needed, the AN could show the challenges to carry out specific examinations in relation to their working environment leading to knowledge integration.

Strengthened collaboration

The neurologists expressed that it was easier to provide feedback to the ANs after a video consultation, as they were able to see the person they were speaking to as well as how the examinations were conducted. They observed this as an opportunity to promote interprofessional collaboration in the long run. The fact that the neurologist gets a view of the ANs’ working environment can increase the understanding between the two specialist professions. Furthermore, the ANs found video consultation to be a natural development in advancing ambulance care and as a means of facilitating the extended chain of care.

Then, you can actually give some feedback to the ambulance staff afterwards that maybe you shouldn’t have done this or that, or that was right or wrong in my eyes, or if I were in that situation, I would have done this or that. So, in the long run, it leads to better, I think, better collaboration and better results. N1

I believe this is the future. If we can make this work, this system, our work processes would be easier, I think. T2

Knowledge exchange facilitation

The neurologists expressed that seeing the patient facilitated assessment in cases where the ANs felt insecure. They also saw video support as an opportunity to instruct and, when needed, correct the AN in carrying out examinations, facilitated knowledge exchange.

For a long time, we have been working without even really knowing if we are doing the right thing. T3

The analysis of the video recordings clearly depicted that in all consultations, there were occasions where the neurologist corrected the AN on the way in which specific assessments should be conducted. Furthermore, the neurologist wanted the AN to repeat some examinations with small adjustments. For example, when an AN examined the patient’s visual fields using a pen as a focal point, the neurologist instructed the AN to move the pen farther to the left of the patient’s visual field. During two of the consultations, the ANs expressed some uncertainty in the execution of specific assessments and asked for more instructions.

Definitely. Absolutely. That’s what happens. It’s like a form of guidance, and we get a shared view on how to do the NIHSS, and we became more aware of what the ambulance does, and the ambulance became more aware of how we think it should be done. N2

Moreover, the ANs reported having the neurologist as a support for assessments as another advantage, as getting an expert opinion is crucial. At the same time, both the neurologist and the AN are able to see the same situation, which can lead to fewer exchange of questions. The video fed not only clarifies what the AN is trying to describe but also provides the neurologist with an opportunity to address any questions they might have.

//Avoid having to give descriptions, otherwise it’s like “well, we’ve done the NIHSS, we’ve got this score.” And then you get follow-up questions on basically each NIHSS question,//but really it is better to do the whole thing and score it together with the on-call staff via video because then they see the same thing that I see, and so it is scored by the person who is best at scoring. T3.

Communication

Both ANs and neurologists found that the video complemented verbal communication. They expressed some difficulties pertaining to the different languages used by the two professions in terms of professional terminology. This became evident through the video as they could see that they meant different things and use different terminology. Furthermore, while they recognized several communicative advantages, they also identified some shortcomings in terms of describing the way in which an examination should be conducted and using the video in an optimal way.

Differences in knowledge and terminology

The ANs expressed that they found the video image to be a source of reassurance, as it enabled them to show the patient and the symptoms being exhibited to the neurologist. This helps to address situations in which they are questioned when reporting over the phone. They also experienced ambiguities in communication as a result of the different concepts and terminologies used by neurologists to indicate the same thing, which made ANs feel insecure, that could, in turn, create misunderstandings. The ANs expressed the importance of clarity in communication and the need to use common and familiar expressions.

//they used expressions that I had not heard. They had a word for slurred speech. Not dysphasia, but something else, and so on. And then it can be a bit difficult sometimes//in the ambulance we know a lot, but we know only a bit about everything in some way. T3

The unfamiliarity of ANs with performing some of the stroke examinations, coupled with the neurologist’s lack of experience in instructing about the same, can often lead to misunderstandings. In the interviews, the ANs requested better instruction. However, although they clearly highlighted this need in the interviews, the video recordings revealed that only one team (T4) explicitly asked the neurologist to explain something on one occasion. This specific ambulance team also set themselves apart by frequently verifying with the neurologist whether they had reached a consensus based on their assessments and decisions.

It won’t work because we do a thousand other things as well. So, this one that we have on paper, the modified one, we should be able to do that, of course. But in the other parts that they want//they should be able to develop some detailed instructions. T2

The ANs also requested better telephone discipline from neurologists. The lack of feedback or silence led to uncertainty about whether the communication was ongoing or whether the call had disconnected. This was visible in the video recordings of the sessions, on occasions when the AN asked the neurologist if they were still connected during an ongoing examination. One AN even started fidgeting with the phone to check if the call was still ongoing.

They just get quiet and you don’t know if they are still connected or not, if you say “Hello?” “Yes,” they reply, a bit annoyed. “I’m here.” Sure, but say something you might think. T2

Enhancing communication

Overall, the participants perceived communication as functioning effectively. Furthermore, the ANs reported that once they had received the decision regarding the next step to move forward, they stopped with the examinations.

And then she said yes, “But that’s enough,” she said. It’s good; then you don’t need to talk so long, this is sufficient. T3

The ANs also found the video support advantageous for communication, as the video images helped the neurologist confirm the details being reported. Moreover, the video could help comprehend factors that might be difficult to explain verbally, thus aiding the reporting process. Analysis of the video recordings showed that, on some occasions, the ANs wanted to confirm that the neurologist saw the results of the examinations by simply asking whether they noticed it on the video. On one such occasion, the nurses directly used the video to exhibit a certain incident.

It’s because we see the same things and have the same understanding. There are … I think I’ve seen a picture like that when someone describes … it’s almost like playing telephone sometimes. T3

In all consultations, the ANs reported the results of the examinations verbally, even though they were clearly visible in the neurologists’ video feed. For example, when an AN carried out a sensory examination and the patient reacted by moving their head, the AN explained the reaction to the neurologist – that the patient had reacted by moving their head to the side where the AN was pinching.

The neurologists expressed that the ANs were easy to instruct during consultations. They also emphasized the same advantage as expressed by the ANs – that the video complemented and enhanced verbal communication and also led to increased consensus regarding examinations.

There is a lot that works well, but the NIHSS 8 is a bit of a mystery box. What does it mean? N2

Effects on patient care

The video helped neurologists obtain a holistic view of the patient – observing him/her as a person and not just a list of symptoms. However, the neurologists also reflected on the shift in focus on the part of the AN, highlighting that the examination became more medically oriented, with lesser focus on caring. In this context, the ANs determined patient safety to be the greatest benefit, considering that “the right person” with the highest specialized competence is able to assess the patient at an earlier stage in the chain of care, which is more likely to lead to an early and more valid decision.

Patient risk and benefits

The ANs found the video to be a valuable decision-making support and a way to ensure that the patient gets the right level of care faster. The video can contribute to making a more valid decision, which leads to more efficient patient care.

Not definitively, because if you don’t call the primary neurologist on call//then they get a little unsure “yes, wait a minute, I’ll call my colleague.”//Now you get a correct assessment from the person who is best suited to make an assessment right away, and then you get a decision. So, I think it will be more efficient. T3

The neurologists expressed uncertainty regarding the difficulty of conducting sufficient examinations and assessments over video with the patient in an ambulance. If the neurologist becomes too meticulous, video consultation runs the risk of delaying appropriate care. However, adequate investigation is crucial for making a well-founded decision. Even the ANs expressed encountering difficulty in finding this crucial balance with regard to administering the adequate amount of necessary care.

Yes, I definitely think so. On the other hand, there is a risk that as a neurologist you start examining patients very carefully in the ambulance, and I don’t think you should do that, because then you cause a delay. The key is to do just as much as needed and no more than that. N1

Impact on patient relations

The neurologists expressed that the video contributed to their ability to quickly acquire a holistic view of the patient. As a result, they could begin their assessment even during the AN’s initial report.

And the first thing I thought about was that it helped so much more to see the patient and that when I … for the first case when I got the report from the ambulance staff, I looked at the patient at the same time and already there I could see a lot of things on my own. N1

The neurologists reflected that while they could develop an overall view of seeing the patient on video, this could also foster biases that may influence the overall assessment depending on the patient’s overall appearance. The ANs reflected on the possibility that it can be more difficult for the neurologist to dismiss patients when they see them as a person and not as just a list of symptoms and signs. Therefore, seeing the patient might get the neurologist more involved in the treatment.

So, you get some kind of overall picture when you see a patient,//You become more prejudiced when you see the person, too. N2

No, I think the patient gets a better assessment if they see the patient. I think it will lead to better management. More personal, and I think it’s more difficult for them to just say, “No, we won’t accept this patient.” T2

One participant highlighted that assessing a patient from a distance makes the process more medical, thus negatively affecting the patient's perspective. One of the neurologists also reflected on the fact that the AN had lost the patient's perspective when the consultation started, meaning that the patient became more of an object.

I thought about that when I looked at the ambulance staff, they were very calm and caring, and were very focused on the patient. But I thought that when we spoke via phone, it was more like//well, what should we say? [The patient] became more like an object. N2

The ANs expressed that they actively chose to focus on the patient to maintain sound patient contact while participating in the video consultation. However, the recordings showed that the primary AN appeared to have lost patient focus on initiating the video consultation (). This often led to the second AN trying to maintain contact with the patient through body contact, talking to the patient, and explaining what was being done and why.

Moreover, in one consultation, the neurologist was in direct contact with the patient, asking the patient questions over the speaker phone. Here, the ANs were hesitant about whether having the neurologist on speaker talking directly to the patient would aid or harm the patient.

Discussion

A fundamental benefit of video consultation, as identified by both the neurologists and ANs, was that it depicted elements that were difficult to explain verbally. This helped both the neurologists, who were able to investigate an image of the factors that were perceived as unclear, and the ANs, by providing them with the possibility to show things they had difficulty describing. Overall, this suggests that both professions benefited from using the video in the form of carrying out richer consultations as a basis for patient assessment and continued care. As discussed below, the results also revealed several challenges related to professional boundaries and judgment, hierarchical order, and loss of patient focus.

This new way of working can potentially contribute to more tightly coupled professional collaboration and teamwork. More specifically, the use of video can contribute to professionals’ discretionary reasoning about collaboration between the groups. The theory by Neale, Carrol and Rosson (Citation2004) describes the importance of sharing the same context to reach a more tightly coupled team. Video support enables neurologists to visually access the ambulance and gain an understanding of the AN’s work context, thus creating a richer and more visual basis for collaboration. Video can be a catalyst for a more integrated and effective teamwork among the professionals. Notably, understanding each other’s contexts is critical for interprofessional collaboration. According to Neale, Carrol, and Rosson (Citation2004), current phone consultations may be characterized as information sharing between loosely coupled teams. To reach a higher level in the pyramid, members of the team must efficiently coordinate their work and tasks and establish common ground and goals (Neale et al., Citation2004). In video consultations, the ANs and the neurologists have a clear common goal – administering the right level of care to the patient as soon as possible. Using video, they can perform the examination together, thus enabling tightly coupled collaboration as a result of the possibilities to visually interact, show, instruct, and discuss. In this way, phone-based information sharing advances to reach the level of collaboration. Moreover, as illustrated by the results of this study, ensuring effective collaboration requires further attention and effort, including the need for clarifications about language and terminology, as well as deciding who should take the lead in consultation.

Furthermore, the results of this study show that both professions perceive that video could help establish contact of a more personal nature, making it easier to provide and receive feedback. Moreover, video can contribute to substantial knowledge exchange between fields, thus contributing to expanding the understanding of each field. As described by Svensson (Ann, Citation2012), this encourages knowledge integration between ANs and neurologists. Knowledge integration refers to interactions and collaboration between different professional domains of knowledge that work together toward achieving a common goal. In such circumstances, video streaming can help visualize and integrate the tacit knowledge of the AN and the expert knowledge of the neurologist.

The fact that the ANs expressed the need for better instructions regarding examinations that they normally do not perform in the interviews but rarely asked for this during the simulations might indicate the presence of an uncertainty, where one refuses to ask questions at the risk of appearing ignorant. The discretionary reasoning does accordingly also illustrate professional boundaries between the groups. In such a context, the professional judgment among neurologists might presume that the AN clearly understands what is being asked of them. This is an instance of a circumstance depicting the meeting of two professions, where the neurologist possesses higher medical competence as a stroke specialist and only deals with this specific condition, while the AN specializes in a broad skill set but rarely works with a stroke patient. This apparent hierarchical order can also be an expression of the cohesion problem, which is enhanced by an individual’s professional roles (Ernst, Citation2020). In addition, video support may contribute to ANs experiencing the loss of a part of their professional discretion and autonomy when a neurologist suddenly invades their domain.

The simulated sessions demonstrated communication discrepancies between the AN and neurologist. This included repeated questions and information and situations where it was unclear from both parties regarding who should take the lead in the consultation and patient assessment. This indicates that there is a need for a basic structure for the communication process in the next phase of the video implementation, in order to make the video consultation as efficient as possible. There were also situations when AN and neurologist used the same terminology or term but clearly referred to different things. Here, the video allowed the neurologist to actually see how the AN conducted different assessments and examinations, identify discrepancies and provide feedback and improvement suggestions on the execution of the steps in the stroke assessment. These instances illustrated the development of knowledge integration and exchange between the ANs’ broad “multi-patient multi-situation” competence and the neurologists’ highly specialized stroke and neurology competence.

The video consultations also seem to influence the caregiver-patient relationship. The results indicate a significant risk of ambulance personnel when talking with the neurologist via video, were shifting their focus both visually and in care approach from patient-centered care to a more medically-centered one. Risks associated with this shift include the potential for patients in a vulnerable position to experience objectification, increased exposure, and vulnerability. Another risk identified by both the neurologists and ANs, was to find a balance in doing just enough examinations to provide a basis for a well-founded decision, primarily to avoid prolonging the prehospital time. While this risk is evident, any time lost in the ambulance could potentially be regained at the hospital, both through the correct transport destination decision and given that the patient has already been assessed by a neurologist prior to arrival and thus might avoid the need for repeated assessments.

Limitations and future research

This study is based on a simulation approach, and as such there are inherent limitations. To maximize consistency, transferability, and validity we used a highly contextualized simulation approach, which is further elaborated in a subsequent publication. Despite the inherent artificial limitations, the simulations provided a safe study environment as a basis for generating crucial knowledge pre-implementation, and thus inform and better prepare for the clinical pilot implementation and development of the studies that will be conducted then.

Conclusion

As the development toward more care being provided outside of hospitals, including a wider scope of patients and potential transports for ambulance personnel, e.g. to primary care or scheduling home visits, there is a need for new ways of working where remote care and consultations supported by video plays a significant role. The study has identified several significant advantages of using video for collaboration between neurologists and ANs, one being that it allows both professions to convey and comprehend elements that are challenging to articulate verbally. However, the study also highlights problems that may emerge when two different professions collaborate using a new work tool or approach, including potential uncertainty among ANs to seek clarification on tasks they are less familiar with, possibly due to professional boundaries and hierarchical dynamics. The need for clear guidelines became apparent, not only regarding patient care but also in the case of choosing who should take the lead in the consultation. Additionally, the need for efficient synchronization to ensure that both ANs and neurologists use the same terminology during examinations and in identifying patients’ symptoms became obvious. The risk of prolonging the consultation and thus the total prehospital time and time to care is notable and will be further investigated in the future implementation and clinical trial.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Lise-Lotte Omran

Lise-Lotte Omran is a PhD student in caring science at the Univerity of Borås.

Magnus Andersson Hagiwara

Magnus Andersson Hagiwara is a Professor in prehospital care at the University of Borås.

Goran Puaca

Goran Puaca is a senior lecturer in sociology at the University of Borås.

Hanna Maurin Söderholm

Hanna Maurin Söderholm has a PhD in information science and is program director at PICTA Prehospital Innovation Arena, in Lindholmen Science park , Gothenburg Sweden.

References

- Andersson, E., Bohlin, L., Herlitz, J., Sundler, A. J., Fekete, Z., & Andersson Hagiwara, M. (2018). Prehospital identification of patients with a final hospital diagnosis of stroke. Prehospital and Disaster Medicine, 33(1), 63–70. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049023X17007178

- Andersson Hagiwara, M., Lundberg, L., Sjöqvist, B. A., & Maurin Söderholm, H. (2019). The effects of integrated it support on the prehospital stroke process: Results from a realistic experiment. Journal of Healthcare Informatics Research, 3(3), 300–328. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41666-019-00053-4

- Ann, S. (2012). Kunskapsintegrering med informationssystem i professionsorienterade praktiker [Elektronisk resurs]. Department of Applied Information Technology, University of Gothenburg.

- Backlund, P., Engstrom, H., Johannesson, M., Lebram, M., Hagiwara, M. A., & Soderholm, H. M. (2015). Enhancing immersion with contextualized scenarios: Role-playing in prehospital care training. 2015 7th International Conference on Games and Virtual Worlds for Serious Applications (VS-Games), Skövde Sweden (pp. 1–4). IEEE.

- Barrett, K. M., Pizzi, M. A., Kesari, V., TerKonda, S. P., Mauricio, E. A., Silvers, S. M., Habash, R., Brown, B. L., Tawk, R. G., Meschia, J. F., Wharen, R., & Freeman, W. D. (2017). Ambulance-based assessment of NIH Stroke Scale with telemedicine: A feasibility pilot study. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare, 23(4), 476–483. https://doi.org/10.1177/1357633X16648490

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Bruce, K., & Suserud, B. O. (2005). The handover process and triage of ambulance-borne patients: The experiences of emergency nurses. Nursing in Critical Care, 10(4), 201–209. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1362-1017.2005.00124.x

- Charash, W. E., Caputo, M. P., Clark, H., Callas, P. W., Rogers, F. B., Crookes, B. A., Alborg, M. S., & Ricci, M. A. (2011). Telemedicine to a moving ambulance improves outcome after trauma in simulated patients. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery, 71(1), 49–55. https://doi.org/10.1097/TA.0b013e31821e4690

- Cheung, S.-T., Davies, R. F., Smith, K., Marsh, R., Sherrard, H., & Keon, W. J. (1998). The Ottawa telehealth project. Telemedicine Journal, 4(3), 259–266. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.1.1998.4.259

- D’Amour, D., Ferrada-Videla, M., San Martin Rodriguez, L., & Beaulieu, M.-D. (2005). The conceptual basis for interprofessional collaboration: Core concepts and theoretical frameworks. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 19(sup1), 116–131. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820500082529

- Engström, H., Andersson Hagiwara, M., Backlund, P., Lebram, M., Lundberg, L., Johannesson, M., Sterner, A., & Maurin Söderholm, H. (2016). The impact of contextualization on immersion in healthcare simulation. Advances in Simulation, 1(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41077-016-0009-y

- Ernst, J. (2020). Professional boundary struggles in the context of healthcare change: The relational and symbolic constitution of nursing ethos in the space of possible professionalisation. Sociology of Health & Illness, 42(7), 1727–1741. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.13161

- Evetts, J. (2011). A new professionalism? Challenges and opportunities. Current Sociology, 59(4), 406–422. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392111402585

- FLISA. (2017). Behandlingsriktlinjer Nationella riktlinjer för ambulanssjukvården. cited 2023. [2023-03-22]; Retrieved from https://www.s112.se/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/SLAS-behandlingsriktlinjer-Vuxen-och-barn-20180102-2.pdf

- Hall, P. (2005). Interprofessional teamwork: Professional cultures as barriers. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 19(sup1), 188–196. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820500081745

- Hautz, S. C., Oberholzer, D. L., Freytag, J., Exadaktylos, A., Kämmer, J. E., Sauter, T. C., & Hautz, W. E. (2020). An observational study of self-monitoring in ad hoc health care teams. BMC Medical Education, 20(1), 201. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02115-3

- Ishikawa, K., Yanagawa, Y., Ota, S., Muramatsu, K. I., Nagasawa, H., Jitsuiki, K., Ohsaka, H., Nara, T., Nishizaki, Y., & Daida, H. (2022). Preliminary study of prehospital use of smart glasses. Acute Medicine & Surgery, 9(1), e807. https://doi.org/10.1002/ams2.807

- Janerka, C., Leslie, G. D., Mellan, M., & Arendts, G. (2023). Review article: Prehospital telehealth for emergency care: A scoping review. Emergency Medicine Australasia, 35(4), 540–552. https://doi.org/10.1111/1742-6723.14224

- Johansson, A., Esbjörnsson, M., Nordqvist, P., Wiinberg, S., Andersson, R., Ivarsson, B., & Möller, S. (2019). Technical feasibility and ambulance nurses’ view of a digital telemedicine system in pre-hospital stroke care – a pilot study. International Emergency Nursing, 44, 35–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ienj.2019.03.008

- Lindström, V., Bohm, K., & Kurland, L. (2015). Prehospital care in Sweden. Notfall + Rettungsmedizin, 18(2), 107–109. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10049-015-1989-1

- Lingard, L., Espin, S., Whyte, S., Regehr, G., Baker, G. R., & Reznick, R. (2004). Communication failures in the operating room: An observational classification of recurrent types and effects. Quality & Safety in Health Care, 13(5), 330–334. https://doi.org/10.1136/qshc.2003.008425

- Magnusson, C., Herlitz, J., Sunnerhagen, K. S., Hansson, P.-O., Andersson, J.-O., & Jood, K. (2022). Prehospital recognition of stroke is associated with a lower risk of death. Acta Neurologica Scandinavica, 146(2), 126–136. https://doi.org/10.1111/ane.13618

- Magnusson, C., Lövgren, E., Alfredsson, J., Axelsson, C., Andersson Hagiwara, M., Rosengren, L., Herlitz, J., & Jood, K. (2021). Difficulties in the prehospital assessment of patients with TIA/stroke. Acta Neurologica Scandinavica, 143(3), 318–325. https://doi.org/10.1111/ane.13369

- Maurin Söderholm, H. (2013). Emergency visualized : Exploring visual technology for paramedic-physician collaboration in emergency care. Valfrid, Högskolan i Borås.

- Molander, A., Grimen, H., & Eriksen, E. O. (2012). Professional discretion and accountability in the welfare state. Journal of Applied Philosophy, 29(3), 214–230. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5930.2012.00564.x

- Neale, D. C., Carroll, J. M., & Rosson, M. B. (2004). Evaluating computer-supported cooperative work: Models and frameworks. Proceedings of the 2004 ACM conference on Computer supported cooperative work, November 2004, Chicago, Illinois, USA (pp. 112–121).

- O’Leary, K. J., Ritter, C. D., Wheeler, H., Szekendi, M. K., Brinton, T. S., & Williams, M. V. (2010). Teamwork on inpatient medical units: Assessing attitudes and barriers. BMJ Quality & Safety, 19(2), 117–121. https://doi.org/10.1136/qshc.2008.028795

- Pinelle, D., & Gutwin, C. (2006). Loose coupling and healthcare organizations: Deployment strategies for groupware. Computer Supported Cooperative Work (CSCW), 15(5), 537–572. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10606-006-9031-2

- Ramsay, A. I. G., Ledger, J., Tomini, S. M., Hall, C., Hargroves, D., Hunter, P., Payne, S., Mehta, R., Simister, R., Tayo, F., & Fulop, N. J. (2022). Prehospital video triage of potential stroke patients in North Central London and East Kent: Rapid mixed-methods service evaluation. Health and Social Care Delivery Research, 10(26), 1–114. https://doi.org/10.3310/IQZN1725

- Rodehorst, T. K., Wilhelm, S. L., & Jensen, L. (2005). Use of interdisciplinary simulation to understand perceptions of team members’ roles. Journal of Professional Nursing, 21(3), 159–166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.profnurs.2005.04.005

- Salas, E., Sims, D. E., & Burke, C. S. (2005). Is there a “Big Five”. Teamwork? Small Group Research, 36(5), 555–599. https://doi.org/10.1177/1046496405277134

- Sheila, C. O. M., Gustavo, W., Andrea, G. A., Rosane, B., Leonardo, A. C., Ana Claudia de, S., Martins, M. C. O., Nasi, G., Nasi, L. A., Batista, C., Sousa, F. B., Rockenbach, M. A. B. C., Gonçalves, F. M., Vedolin, L. M., & Nogueira, R. G. (2020). Validation of a smartphone application in the evaluation and treatment of acute stroke in a comprehensive stroke center. Stroke, 51(1), 240–246. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.119.026727

- Söderholm, H. M., & Sonnenwald, D. H. (2010). Visioning future emergency healthcare collaboration: Perspectives from large and small medical centers. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 61(9), 1808–1823. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.21365

- Söderholm, H. M., Sonnenwald, D. H., Manning, J. E., Cairns, B., Welch, G., & Fuchs, H. (2008). Exploring the potential of video technologies for collaboration in emergency medical care: Part II. Task performance. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 59(14), 2335–2349. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.20939

- Takao, H., Sakai, K., Mitsumura, H., Komatsu, T., Yuki, I., Takeshita, K., Sakuta, K., Ishibashi, T., Sakano, T., Yeh, Y., Karagiozov, K., Fisher, M., Iguchi, Y., & Murayama, Y. (2021). A smartphone application as a telemedicine tool for stroke care management. Neurologia medico-chirurgica, 61(4), 260–267. https://doi.org/10.2176/nmc.oa.2020-0302

- Troyer, L., & Brady, W. (2020). Barriers to effective EMS to emergency department information transfer at patient handover: A systematic review. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine, 38(7), 1494–1503. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2020.04.036

- Vicente, V., Johansson, A., Ivarsson, B., Todorova, L., & Möller, S. (2020). The experience of using video support in ambulance care: An interview study with physicians in the role of regional medical support. Healthcare, 8(2), 106. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare8020106

- Vicente, V., Johansson, A., Selling, M., Johansson, J., Möller, S., & Todorova, L. (2021). Experience of using video support by prehospital emergency care physician in ambulance care - an interview study with prehospital emergency nurses in Sweden. BMC Emergency Medicine, 21(1), 44. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12873-021-00435-1

- Weller, J., Boyd, M., & Cumin, D. (2014). Teams, tribes and patient safety: Overcoming barriers to effective teamwork in healthcare. Postgraduate Medical Journal, 90(1061), 149–154. https://doi.org/10.1136/postgradmedj-2012-131168

- White, B. A. A., Eklund, A., McNeal, T., Hochhalter, A., & Arroliga, A. C. (2018). Facilitators and barriers to ad hoc team performance. Baylor University Medical Center Proceedings, 31(3), 380–384. https://doi.org/10.1080/08998280.2018.1457879

- Wireklint Sundström, B., Andersson Hagiwara, M., Brink, P., Herlitz, J., & Hansson, P. O. (2017). The early chain of care and risk of death in acute stroke in relation to the priority given at the dispatch centre: A multicentre observational study. European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 16(7), 623–631. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474515117704617

- Wood, K., Crouch, R., Rowland, E., & Pope, C. (2015). Clinical handovers between prehospital and hospital staff: Literature review. Emergency Medicine Journal, 32(7), 577–581. https://doi.org/10.1136/emermed-2013-203165

- World Medical Association. (2022). WMA declaration of helsinki - ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects [internet]. cited, Retrieved from https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki-ethical-principles-for-medical-research-involving-human-subjects/

- Wu, T. C., Parker, S. A., Jagolino, A., Yamal, J. M., Bowry, R., Thomas, A., Yu, A., & Grotta, J. C. (2017). Telemedicine can replace the neurologist on a mobile stroke unit. Stroke, 48(2), 493–496. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.015363

- Zhang, Z., Joy, K., Harris, R., Ozkaynak, M., Adelgais, K., & Munjal, K. (2022). Applications and user perceptions of smart glasses in emergency medical services: Semistructured interview study. JMIR Human Factors, 9(1), e30883. https://doi.org/10.2196/30883