ABSTRACT

Understanding students' sense of belonging in Higher Education is crucial for designing courses that improve retention, learning, and wellbeing outcomes. With the rise of online learning, educators face new challenges in fostering belonging in virtual environments. This study delves into the experiences of twenty postgraduate students in online learning settings. Through surveys, focus groups, and interviews, participants shared insights about their online learning experiences, their feelings of isolation or inclusion, and the aspects of online learning that helped keep them engaged. The findings reveal a complex cross-hatching among the themes of learner-instructor interaction, learner-learner interaction, and learner-content interaction, with the subject architecture and pedagogy enabling meaningful relational connections with both peers and instructors resulting in enhanced sense of belonging. By examining how online strategies and environments can be used to support students’ connections, we demonstrate how universities could reduce student attrition, enhance student wellbeing, and improve student achievement.

Introduction

The move to learning ‘online’ in the HE sector has increased steadily for some years (Martin, Budhrani, and Wang Citation2019), with universities world-wide viewing online learning as something that can be ‘scaled without significant additional cost’ (Fawns, Aitken, and Jones Citation2019, 293) as well as a way of providing access to students from diverse groups; for example international students, primary caregivers, those geographically isolated, or those requiring flexible learning options (Edwards Citation2019). However, literature both prior (Ragusa and Crampton Citation2018) and post the Covid-19 pandemic (Dutta et al. Citation2021) suggests that student satisfaction hasn’t necessarily followed the same growth trajectory as online learning, with significant attrition rates and diminished student belonging of concern. Indeed, there has been speculation that relationships are poorer online, and that online education is somehow ‘lesser’ than in-person or face-to-face education (Stone Citation2017).

Belonging was a well-established concept in psychology before it became the subject of educational research. Baumeister and Leary (Citation1995) propose that belonging is a fundamental human need which shapes behaviour and motivation. Regularity of contact, its stability, as well as affective concern can promote a sense of belonging. May (Citation2011) suggests that belonging is being at ease and comfortable with oneself and one’s environment. Despite its prominence in educational research, belonging continues to lack definitional consistency. Goodenow (Citation1993, 25) defined belonging as a sense of ‘ … being accepted, valued, included, and encouraged by others (teacher and peers) in the academic classroom setting and of feeling oneself to be an important part of the life and activity of the class. More than simple perceived liking or warmth, it also involves support and respect for personal autonomy and for the student as an individual.’ Although the focus of Goodenow’s work is within the school setting, her definition has been widely used within the HE environment (Ahn and Davis Citation2020).

In HE belonging has gained prominence as an important aspect of the student experience, contributing to academic achievement, learner satisfaction and improved retention rates (Ahn and Davis Citation2020; Peacock and Cowan Citation2019). However, much research undertaken prior to the pandemic regarding belonging in HE did not differentiate between on campus and online learning environments. This study was conceived late in 2019 before the onset of the global pandemic of COVID-19, which has required educational institutions to rapidly transfer teaching and learning from physical to virtual classrooms. Research regarding belonging online has increased since 2020, however much of it refers to what Hodges et al. (Citation2020) call ‘emergency remote teaching’ (ERT). This refers to the rapid transfer of teaching and learning from physical to virtual classrooms utilising the internet and digital technologies to enable access to courses that would otherwise only be available in face-to-face modes. The intention in this shift, however, was always to return to the original mode of delivery once the crisis passed. ERT is therefore considered as distinctive from online education that has evolved beyond a context of crisis over several decades. What has been identified in research as core to effective online education which is rarely possible in ERT is

significant planning, the nurturing of a culture, the development of specific forms of educational expertise, and numerous iterations of design and evaluation, in order to build an approach that works for a particular team of educators and their students, in their context, for their purposes (Fawns, Aitken, and Jones Citation2021, 217).

Our study investigates how students just prior to this time experienced a sense of belonging in a flipped classroom online learning situation. By asking which aspects of online learning aided or impeded students’ sense of belonging to a learning community and their resultant learning experience, we extend our understanding of what fosters students’ sense of belonging in online learning communities.

Theoretical framework

‘Distance Education’ is an umbrella term for any form of education in which the educator and learner are separated throughout the period of instruction (Johnson Citation2003). It is a concept that has evolved considerably since the provision of correspondence courses in the US in the eighteenth century (Pregowska et al. Citation2021) with different forms of ‘online learning’ now occupying this space. ‘Online learning’ developed currency in the final decade of the twentieth century. It is however a term that is subject to multiple interpretations. Singh and Thurman (Citation2019) note, ‘ … definitions explicitly discussed the confusion and debate surrounding the definition of online learning … this confusion can be seen in definitions as early as 2001 and as recently as 2017, highlighting the fact that this continues to be an issue.’ (295). Siemens, Gasevic, and Dawson (Citation2015) defined online learning as ‘a form of distance education where technology mediates the learning process, teaching is delivered completely using the Internet, and students and instructors are not required to be available at the same time and place’ (100). In this study we will use this definition of online learning as a form of distance education involving both synchronous and asynchronous delivery and will use this term throughout, acknowledging that terminology in this area at times lack precision. We refer to components of the ‘flipped classroom’ model which Singh and Thurman describe to be a type of blended learning that has become prominent since 2015. The flipped classroom model involves students engaging with preliminary learning (in our case, asynchronous online activities) before taking part in structured learning activities (in our case, synchronous webinars).

Further consulting the field of Distance Education, the work of Moore (Citation1989) provides a typology of interaction. The research of Garrison, Anderson, and Archer (Citation2000) applying the conceptual framework of Community of Inquiry (COI) in the sphere of distance education also provides an illuminating conceptual frame for this study. These perspectives remain seminal and of contemporary relevance in the field of Distance Education. As Hodges et al. (Citation2020) observed, Moore’s original work remains ‘ … one of the more robust bodies of research in online learning.’

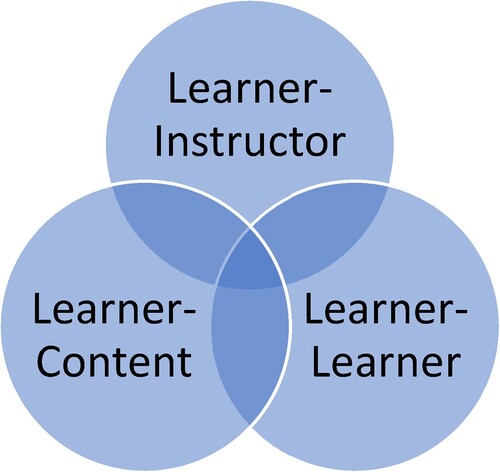

Moore (Citation1989) describes a triangle of interaction between the learner and content, the learner and instructor and between individual learners ().

When these elements of interaction are strongest, Moore’s ‘transactional distance’ is minimised, and the experience of belonging supported. He notes that interaction between the learner and content is the core business of education in which interaction with a prepared and prescribed body of content results in cognitive change for the learner. In some forms of distance education this one-way interaction is the sole type of interaction. In the interaction between learner and instructor, Moore contends the key element is feedback which provides the learner with evaluation of their application of new knowledge. Learner to learner interaction acknowledges and makes available prior knowledge of individual learners to all and endorses ‘the scholar as a maker of knowledge.’ (5). Hodges et al. (Citation2020) observe that it is the meaningful integration of these three points of the triangle that enhances learning outcomes for learners, recognizing ‘learning as both a social and cognitive process, not merely a matter of information transmission.’

Moore’s work has been influential with Mehall (Citation2020) focussing on the two interpersonal elements of Moore’s triangle (learner – instructor and learner – learner), seeking to achieve greater definition and nuance through an exploration of ‘purposeful interpersonal interaction’ (184) and on the Community of Inquiry model as imagined in the Distance Education context involving the interplay of three ‘presences’ – teacher, cognitive and social (Garrison, Anderson, and Archer Citation2000). Cognitive presence is brought by learners as they seek to construct meaning in reflection and dialogue with others. Hawkins, Barbour, and Graham (Citation2012) describe social presence as ‘ … not a property of the medium but the individuals’ ability to move past the medium and establish a sense of immediacy, connection, and co-presences between participants.’ (126)

Teacher presence involves the ‘design, facilitation, and direction of cognitive and social processes for the purpose of realizing personally meaningful and educationally worthwhile learning outcomes’ (Anderson et al. Citation2001). Rovai and Downey (Citation2010) suggest that students undertaking online learning are more likely to experience isolation from both their institution and their peers because of physical separation. In distance education, Tinto (Citation1987) argues that students need both academic and social support when undertaking distance education as low levels of interaction can lead to isolation, a low sense of community and risk of withdrawal. This may be one of the reasons Norton, Cherastidtham, and Mackey (Citation2018) found evidence of course completion and program retention rates to be generally lower in online courses than face-to-face counterparts.

Methods

This research sought to ‘describe, explain and interpret a phenomenon … as understood by the participants’ (Cohen, Manion, and Morrison Citation2017, 300). A mixed methods approach allowed us to comprehensively interrogate participants’ perspectives. This study took place in one Australian University. Alumni from a post-graduate Masters and nested Graduate Certificate course focussed on International education, which was delivered fully online, were invited to participate in an online survey and indicate a willingness to be involved in online focus groups or individual in-depth interviews. Most of the Alumni were working teachers located internationally, so using surveys enabled broad participation in the research. A lecturer with knowledge of the course led the focus groups, enabling deeper exploration of participants’ responses. However, to provide optimum conditions for participants to respond candidly, the team member conducting the in-depth interviews was unknown to participants. This Alumni cohort was chosen as the course contained both synchronous and asynchronous pedagogical activities.

Participants

Seventy past students were invited to take part in the study. Of these twenty responded to the survey; eight participants accepted the invitation to join focus groups (these were spread evenly across two groups according to time zones), and four students opted to undertake individual interviews. This research (Ethics ID: 1955929) was approved by the University Human Ethics Advisory Group (HEAG ID: 225/19) in 2019.

The survey

The survey, employing a five-point Likert scale, was designed to gather student opinion regarding approaches to teaching and learning. Participants were asked to consider approaches to teaching and learning in four key areas; content (what was taught), process (how it was taught?), product (how it was assessed?) and environment (the learning platform) within the online context. Much of the survey material was focussed on course content, materials and learning outcomes which are not relevant in this research. However, of the twenty-seven items, five were of direct relevance to this study’s focus of belonging in online learning environments.

| • | Presenting to, and learning from my peers contributed to my sense of belonging to a learning community | ||||

| • | Studying online has been a lonely experience | ||||

| • | I felt safe and valued in the webinar rooms | ||||

| • | I was able to make positive connections with other students within this course | ||||

| • | I enjoyed being able to work collaboratively in the webinar | ||||

Responses to these questions provide a broad, generalised indication that students experienced a sense of belonging, engagement, comfort and safety within the online environment provided for them. The focus group responses and individual interviews provide more specific and detailed data that point to the particularities that built and engendered this experience.

As can be seen in (above), just over half of the 20 survey respondents resided in Australia, 25 per cent of the respondents were male and participants ranged in age from 20 to 70. Participants had enrolled in either a Masters degree or Graduate Certificate with some completing the course in one year, and others taking up to 7 years to complete the course. The survey was conducted during February and March of 2020.

Table 1. Research respondents.

The focus groups

Focus group participants explored the elements of the course that they believed increased or reduced their sense of belonging to a learning community. To gain an understanding of the focus group participants’ mindsets regarding online learning, they were asked about their prior experience and disposition towards online learning before being asked to consider what helped or hindered their sense of belonging in online learning communities. The interviewer prompted participants to consider elements such as the course structure, weekly webinars, and pedagogical practices. Participants were also asked if their sense of belonging changed during their studies, and reasons for any change. The two focus groups took place in April 2020 (see Table one).

The interviews

The individual interviews explored the same issues using the same set of questions as the focus groups, this format allowing for deeper exploration. The individual interviews of one hour took place in May 2020 being scheduled to accommodate the needs of participants.

The analysis

The survey data was analysed using descriptive statistics to identify patterns. The focus group and interview data were analysed thematically drawing on Moore’s categories of learner-content interaction, learner-instructor interaction and learner-learner interaction. Moore’s framework was used to inform a consistent approach to the analysis and to enable a basis for deductive analysis. Predominant patterns were also detected in the data through inductive analysis; the combination of deductive and inductive analysis enabled a systematic approach avoiding inflexible or hasty assumptions about the data findings (Mills, Durepos, and Wiebe Citation2010).

Results and discussion

Participant responses across the data instruments highlighted four areas that were influential in developing a sense of belonging: prior experience of online learning; relationship with the tutor; relationship with their peers, and the course structure and pedagogy.

Prior experience of online learning

In discussing previous experiences of online learning, the participants’ comments clearly surfaced concerns across all of Moore’s categories. Their comments highlight a range of missed opportunities for connection and interaction, and foreground the desire to meaningfully connect with content, their instructor and peers. Where there was a lack of responsiveness from the instructor, or less collaborative opportunities, students were unable to connect and to seek support. This lack of connection has been reported in the work of Farrell and Brunton (Citation2020), who noted that where good course design promotes interaction and a social presence it is possible to decrease students’ feelings of disengagement. Conversely, the lack of personal connections has an impact on their sense of belonging which has potential ramifications for students’ learning and wellbeing.

Learner-instructor interaction

The learner-instructor relationship was a key topic in focus groups and interviews. When asked to comment on teaching practices 11 out of 12 participants provided extensive responses about their connection to teaching staff. The teaching ‘practices’ they spoke of were less focused on specific pedagogical approaches (although these were mentioned), and more on the teacher’s disposition towards students and opportunities for interpersonal exchanges. The experiences of a ‘felt’ connection resulted in greater comfort and ease for participants and a sense of confidence and safety in being free to be themselves.

The willingness of staff to ‘show of themselves’ (Anita) was appreciated by participants as a conduit to developing interest in their subjects, helping students to ‘identify more with the subject’ (Anita). Simple acts or ‘just small things’ (Anita) such as connecting briefly with the class about ‘something funny that happened that day’ (Anita) and chatting briefly about ‘everybody’s week’ (Anita) were noted as relationship-building blocks within the class. Students saw this relationship building as a way ‘to create a relationship with each of the people in the course’ and develop a ‘sense of camaraderie’ (Paul) among the class. As one participant observed: ‘I think that that was the key thing that struck all of us, that personalization aspect of it’ (Paul).

Ninety percent of participants found the online environment an important element in promoting connection and belonging. Within Synchronous webinars students had the chance to interact with their peers. In the survey, 18 of the 20 participants agreed or strongly agreed with the statement that webinars enabled them to deepen their understanding of the content each week. When asked were there any further comments they would like to make about the learning process one participant stated

The webinars were an integral component to the course, they created a sense of community and reduced the isolation of an online-only delivery. The structure of the webinars was important also. Other courses … delivered webinars as lectures, thus limiting the capacity to ask questions and engage with material. So, it wasn't just that the webinars were available, but that they were classroom/tutorial-structured that allowed success. (Lisa).

The focus groups, interviews and surveys conducted for this study indicated that for the students undertaking this course their interpersonal relationships with their instructors is a key platform from which a sense of connection among students and staff was formed and which in turn was influential in shaping both a sense of belonging and community. This finding is consistent with Moore’s theoretical conceptual framing of distance education, and many previous studies (see Gillen-O’Neel, Citation2021; Watson et al. Citation2010) which identify the teacher-student relationship as contributing to students’ sense of belonging. The teacher attributes which study participants highlighted covered both affective (warm, relationally engaging) and pedagogic (commitment to and passionate about the subject), characteristics which broadly align with Minott’s study on perspectives of upper secondary students on the teacher qualities they most value (Minott Citation2022). Other studies have also identified these two categories (Raufelder et al. Citation2016; Thornberg et al. Citation2020; Watson et al. Citation2010).

Hawkins, Barbour, and Graham (Citation2012) notion of the social presence as something which is not impacted by the mode of delivery is crucial here. Whether teaching face-to-face or online it is the sense of connection which is important. One participant’s description of teachers doing ‘small things’ (Anita) within the class as a way of building connections among all class members resonates strongly with Johnson’s study on the teacher-student relationship (Johnson Citation2008). While this study was conducted in a school, students described the ‘little things’ (Johnson Citation2008, 390) that teachers did to establish and nurture relational connections which Johnson characterised as notably ordinary in nature.

Learner-learner interaction

When responding to the survey 17 of the 20 participants agreed or strongly agreed that ‘presenting to, and learning from my peers contributed to my sense of belonging in a learning community’. However, when asked if they enjoyed undertaking some assessments that were collaborative the results were much more mixed with only 12 of the 20 participants agreeing or disagreeing, and four neither agreeing or disagreeing. When asked if they had any further comments about this one participant stated ‘My work at the time demanded lots of travel and working collaboratively can create some excess stress so I appreciated it when the lecturer attempted to pair students according to locations as well as areas of study.’ (Rachel) Another noted that ‘The collaborative assessments were tricky to coordinate’ (Erica). These comments suggest that one of the reasons that collaborative assessments can be problematic is the actual logistics involved with meeting people, many of whom are working full-time and some of whom are based in quite disparate time zones.

Although most survey participants (n = 13) experienced a sense of connection with their peers, three students found studying online a lonely experience and four participants recorded a neutral response when asked if studying online had been a lonely experience. Given that other items affirm a positive experience of belonging in the course, it may be that for some students, even with the affordances of convenience and accessibility, online learning will always be a less satisfying endeavour because of the simple lack of physical presence and all that that entails.

For statements concerning access and safety such as: ‘I felt safe and valued in the webinar rooms’; ‘I was able to access all elements of the course’ and; ‘studying online enabled self-paced learning’, the responses were still extremely positive with only one dissenter for each of these statements.

Participants were asked a range of questions relating to their peer relationships and the group’s diversity emerged as a key contributor to the quality of interpersonal connections. The course drew enrolments from across the globe and consequently, students from diverse cultural and social contexts came together in the one digital classroom. This diversity was a point of curiosity, engagement, sharing and connection, with one student observing that ‘it was really great hearing other people’s perspectives, particularly their cultural perspectives, which I would never have thought about’ (Erica), while another commented that they ‘got connected with people all round the world, it was amazing’ (Krystal). This sentiment was echoed by another participant, saying ‘that the connection with the people from different countries and different experiences was so informative.’ (Rachel). For one participant the online experience was so absorbing that they ‘sometimes forgot that we were actually all in different places at different times because the connection was really good’ (Joanne).

Diversity of professional experience was also singled out as shaping relationships and engagement. Within the subjects, work-related experience spanned a wide range and one of the less experienced participants observed that this both enhanced learning and on occasions caused some hesitation to contribute as ‘there was an underlying feeling that they (other students) were more advanced’ (Judy). Another participant commented that the less experienced students ‘were sort of a bit in the background’ and this resulted in deeper connections with those with less professional experience (Mark). Yet this spread of experience was on balance seen as making conversations ‘very rich’ through the sharing of many different perspectives (Judy).

In discussing their peer relationships, participants highlighted the ways in which the architecture of the online platform and the pedagogy facilitated these relationships. The platform offered ‘so many opportunities to chat’ (Erica) and the chat box function in the Zoom classroom provided a way to ‘share and connect’ (Erica) for those who may not wish to talk. Another participant spoke of the way the chat box was a locus for student-to-student connection with students sharing ‘personal struggles’ (Joanne) and how surprising that was in contrast to their previous in-person on-campus experience when they ‘never really got to know my peers’ (Joanne). The webinars were also singled out as enabling a deep connection and the sense that ‘I’m not alone’ and that others ‘take an interest in my studies’ (Anita). One participant commented on the lack of engagement of asynchronous platforms in previous online learning, stating that ‘It was much more detached, and I noticed that I didn't always contribute to the forum every week’ (Judy). This previous experience had left this participant feeling ‘a bit alone, I didn't have a group to bounce ideas with and no regular contact with the tutor’ (Judy).

Within webinar class numbers seemed to impact student experience. One participant in the study stated ‘I definitely thought that, you know, the number of students in online class kind of affect the quality’ Noting class size had an impact on their ability to interact in a meaningful way with their classmates and he felt ‘a little bit disconnected’ (Paul). Another participant stated that ‘A larger class minimises your opportunity to speak and to be known’ (Lisa) and a third supported this view ‘the smaller class did help’ (Fatima).

In every subject students were required to prepare a critical reading response in pairs. While shared assessment tasks can create tension in students and present practical and interpersonal challenges, when such hurdles are minimised, collaboration can foster connection to the learning community and a deeper appreciation of different perspectives. The sense of working together forged bonds between participants with students emailing each other and sharing resources, ‘driving towards this common goal’ (Fatima). One participant commented that their ‘engagement with people who were self-motivated’ was ‘transformative’ and ‘it was more than an educational experience, it was a genuine life experience’ (Paul).

For most participants the reciprocity of the interpersonal connections was most compelling in drawing them together. One participant who had not experienced a positive connection with a particular tutor, turned to classmates for guidance and support, noting that ‘we were able to help each other and focus on the important aspects of the unit’ (Joanne). Of note in this observation is that peer support compensated for a perceived lack of relational connection with the instructor. This was in contrast to the way in which some students had experienced previous online learning. One participant recalled a lack of responsiveness from the tutor and an inability to seek information and support from peers which they described as ‘very isolating for me … I just sort of felt like I was drowning. I was reaching out but no one was reaching back and I didn't know where else to look,’ (Rachel).

The climate of the digital classroom, where individual experiences were shared and valued, created a classroom climate which helped to mitigate one participant’s lack of confidence and anxiety whereby they realised that ‘while I was different, I had something to contribute’ (Joanne). The nature of the course also meant that students would at times have the same instructor and be with the same peers across several subjects which ‘was a nice feeling’ (Lisa), contributing to a familiarity among peers. The connections were both personal and professional with one participant observing how ‘refreshing’ it was to have ‘robust discussions with like-minded people’ (Mark). This inclusive and respectful environment made deepened relationships and despite the acknowledged challenges in developing relationships in the online classroom, one participant formed some enduring friendships and described this outcome as ‘something very enriching to take from the program’ (Joanne).

For participants in this study, their peer relationships were central to how they engaged with their studies, facilitating ways of meeting within the online space that was both motivating and supportive and generating a sense of community and connection among the group. Within our study, class size was seen as something that could help or hinder student’s engagement with the instructor, the content and their peers. Koricke, Abernathy, and Pardue (Citation2023) suggests that class sizes of more than 20 students have a negative impact on students’ engagement and their ability to become part of a learning community.

Certainly, peer relationships contribute to students’ sense of belonging to university (Farrell and Brunton Citation2020) and for many students the peer-peer connection is the most important affiliation during their tertiary studies (Ahn and Davis Citation2020). In this study participants identified not only the affiliative and learning outcomes of peer relationships but also the contribution of both the online platform and the course pedagogy in creating spaces and opportunities for sociality practices to flourish.

Extensive research on the teacher-student relationship and the peer-peer relationship within the school environment has demonstrated the crucial role teachers and peers play in fostering a sense of belonging and connectedness (see Allen et al. Citation2017; Gowing Citation2019). In contrast, both relationships have been less well researched in the HE context (Asikainen, Blomster, and Virtanen Citation2018; McLeod, Yang, and Shi Citation2019), although they are associated with outcomes including higher retention rates (Richardson and Radloff Citation2014), academic success (Cress Citation2008;), motivation (Groves et al. Citation2015: Fidalgo et al. Citation2020) and adjustment (Maunder Citation2018). Hagenauer and Volet (Citation2014) warn against drawing too heavily on school-based findings given the significant differences between school and tertiary settings. Nevertheless, when participants in this study were invited to reflect on the dynamics of their teacher-student relationships and their peer relationships when undertaking their course, it was evident that they regarded interpersonal connection with both as key to a sense of belonging. This resonates with characterisations of teaching as an affective endeavour with relationality at its core (Hickey and Riddle Citation2021; Kriewaldt Citation2015).

Learner-content interaction

Participant survey results indicate that in the area of course content, where participants were asked to consider the course content materials and learning intentions, students had a very positive experience. All participants felt that they had extended their knowledge of the area, found the content and reading materials relevant to their learning, and that the course was sequenced to allow them to build and deepen their knowledge. Focus group and interview participants saw the structure of the online materials, the process embedded in each subject and the pedagogical scaffolds, as essential supports to their sense of belonging in the online learning community.

The weekly material in each subject of this course employed a flipped classroom design. All materials were provided in a weekly module, and students were asked to work through the materials at their own pace with the expectation that they would attend a weekly webinar and be able to engage with their colleagues and the material in more depth. Students were able to access materials such as pre-recorded mini-lectures, external material, readings, engage with research through interactive design and participate in discussion boards.

The nature of the flipped classroom appealed to several participants who noted that the flipped classroom approach worked because it gave them the chance to ‘get into the material by myself and then work with other people’ (Anita). This ability to self-pace also offered students the chance to access the material on multiple occasions ‘ … when I read things I like to read them like twice – I kind of understand how to read it and then I'll read it again to really understand, it allows for that but then takes it deeper … ’ (Erica), which enabled participants to control their own learning. Participants also found that the modular structure was helpful as it enabled them to build knowledge at their own pace. ‘The materials are set out for you to engage in chunks so that you can have your chunk and then build and consolidate.’ (Lisa). Participants also noted the accessibility and availability of materials throughout the whole learning journey, suggesting they felt some efficacy in their own learning journey.

A specific feature of the weekly structure integral to the flipped classroom approach was the road map. Far from being revolutionary, the road map comprised a short piece of written text at the head of each week of study explicating the focus, the direction and destination of the week’s activities and where they fitted in the subject as a whole. Yet, this signposting provided an understanding and awareness that appeared to promote security and confidence in students and the sense of journeying together: ‘That road map helped me go, where am I up to? Because I had this road map to keep going back to where am I up to in my learning, it helped me really get it and pace myself’ (Matthew). Others spoke of the road map helping to ‘connect a certain section to the whole course’ (Krystal). Enabling students to learn in their own time and own way, along with the scaffolding of a structured approach to learning appears to have facilitated students’ meaningful engagement with the content.

Social constructivism suggests that the social environment of any classroom is critical to enhancing knowledge and understanding as it allows students to learn from one another and experiment with knowledge (Schunk Citation2008; Vygotsky Citation1962). In this course webinars were seen as instrumental in enabling students’ exploration of ideas in a constructivist learning environment. When asked in the survey if webinars enabled participants to deepen their understanding of the content each week, the results were very encouraging with eighteen of the twenty participants recording a positive result. Of the seven open-ended comments, four focussed on the webinar as an integral learning space, with one person stating ‘they created a sense of community and reduced the isolation of online-only delivery. The structure of the webinars was important also … it wasn't just that the webinars were available, but that they were classroom/tutorial-structured that allowed success’ (Lisa).

Participants repeatedly remarked on the dialogic nature of their webinars and the strongly collaborative approach that was promoted by teaching staff. One participant described their experience as an ‘exchange rather than download’ (Paul). Another added further detail to this observation ‘you get to have a conversation and clarify misconceptions and see what other people's interpretations of the learning was … ’ (Erica) For this participant, an initial anxiety was alleviated by the conversational, participatory atmosphere noting ‘Everybody wanted to have that sort of contribution, or to ask questions … (Erica).’ Furthermore, the invitational dynamic gave this participant a sense of the value of their own voice and a freedom of expression: ‘ … It wasn't like you had to get the correct answer. It wasn't that kind of conversation (Erica).’

Another element of the synchronous weekly webinars noted by participants was the expectation that they were fully present. For some this was because it was ‘a point where all the students are in the room. Their cameras … their microphones are turned on. So I felt that that really created a sense of belonging (Mark).’ This idea of visibility clearly holds its own participation accountability with participants stating

I felt that seeing my instructor, seeing my other classmates’ faces really motivated me to do well, to be a part of the community. When everyone is giving their own opinion, I felt that I really needed to also contribute something even as small as a short comment. (Mark).

In this study focusing on the experience of participants, the weekly webinar was the lynchpin in the course structure that promoted a sense of belonging. The participant observations that follow are a testament to this, with their means of connecting everyone involved being the dominant theme: ‘The weekly webinar is a must. I think that connects with all students.’ (Joanne) adding that for them, the weekly webinar was vital to their learning and sense of belonging.

Moore’s triangle of interaction suggests that where students are given the opportunity to engage with the peers their learning is both social and cognitive. Participants in this research have suggested that when it comes to the content-student dimension of online learning aspects such as the course structure and accessibility, dialogic nature of webinars, and visibility leading to accountability, all help create a sense of belonging.

Limitations

This study consists of overwhelmingly positive responses from participants. Only an occasional dissonant note is sounded in respect of their experiences of online learning in the course. We acknowledge that the overwhelmingly positive responses may be due to the small number of participants and their self-selection into the study. The lack of diversity and the self-selection bias limits the generalizability of the findings. Research investigating the experience of belonging in online learning across several programs at this university and across institutions would provide valuable data and enhance the validity of this small-scale study. Nonetheless, it appears that the dissonance noted above is an individual response driven by unique and specific factors rather than a pattern. Certainly, the factors that contributed to the quality of participants’ experience are worth highlighting and warrant consideration when preparing for online learning in tertiary contexts. Using Lincoln and Guba’s guide for trustworthiness in naturalistic inquiry (Citation1985), this study has merit around the four touchstones of ‘truth value’, applicability, consistency and neutrality. Noteworthy in this regard is the use of triangulation of methods and investigators to increase the likelihood that the ‘truth value’ of the study achieves credibility. Counter voices have been curiously sought across all data collection methods and respondents have provided an unexpected source of credibility and applicability in contrasting their previous online learning experiences with the ones in this study. The consistency of respondents’ views around the key areas of enquiry, linked to their insights on their previous experiences emboldens a modest claim to applicability and consistency. Neutrality has been safeguarded by the inclusion of a third researcher with no previous involvement in the courses under investigation and the positionality of the other two researchers has been foregrounded and acknowledged throughout all stages of the study.

Final observations

Commentary on online learning has gained increased coverage recently and opinions are often reductive in nature with the digital classroom frequently characterised as either as a depersonalised space or the natural habitat of students in the C21st. Opinions about the delivery of online learning similarly attracts divergent views from claims that the movement from in-person learning to the digital classroom requires minimal change whilst others consider the change a seismic shift beyond the already exhausted capacities of many educators. As is often the case when extreme positions are adopted, the experience of most people will lie somewhere towards the middle and almost certainly be complex and nuanced.

This study explored students’ sense of belonging within a HE online learning environment prior to the onset of COVID-19. It is therefore important to note that the online learning landscape has undergone radical changes in delivery, scope and ambitions since that time with understandings of online belonging and social presence continuing to evolve. This study contributes to this knowledge by bringing a a nuanced understanding of the ways in which students experience a sense of belonging in online classrooms, albeit pre-pandemic. The findings from this study also make a valuable contribution to the future experiences of both educators and students, as a return to face-to-face teaching and learning in the context of the COVID-19 era appears more challenging and complex than initially imagined. The responses from study participants suggest establishing personal connection with both instructors and peers, to an extent where a sense of belonging to a learning community is cultivated, takes root and grows strongly, can be achieved in online learning environments when two elements, personnel and pedagogy, work dynamically together.

Not every person who trains to be a teacher is successful or effective in the classroom, similarly not every teacher possesses the disposition to promote student engagement and a sense of belonging in an online environment. Participants in this study noted qualities of personal openness, affability and collegiality in their teachers. It is important to note that there were no comments at all concerning the technical skills of these teachers. The two researchers and their colleagues teaching in this course were not technological wizards, but they were capable of wielding the technology to serve their larger pedagogical purposes, and confident enough in the online classroom for ‘technology’ to recede into the background rather than being a focus of anxiety.

The architecture and underpinning pedagogy of the course was vital in supporting participants’ diverse learning preferences and streamlining course materials to maximise accessibility in the context of their demanding work and family lives. Being attentive to such elements required meticulous learning design. Fawns, Aitken, and Jones (Citation2019) note that institutional administrators do not see, nor perhaps want to see, the huge amount of time required by teachers to prepare work for the online environment: ‘The assumption that online learning can be unproblematically scaled up without significant additional cost or increased pressure on staff is implicit (or, sometimes, explicit) in a number of policies and initiatives in higher education’ (295).

Drawing on Moore’s (Citation1989) triangle of interaction model, and Garrison, Anderson, and Archer (Citation2000) three presences ideas to consider the online learning space enables educators to look beyond the teaching medium. Teacher disposition, pedagogical awareness and versatility, and to a lesser extent technical prowess, are key to students experiencing a sense of belonging in an online learning community. What teachers can build for students may however be severely compromised by a lack of administrative understanding and support. Online courses are not shortcuts to budget savings. Indeed, if appropriate resources are not deployed to support the work of teachers in designing and developing them, students will vote with their fingers and log out.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- Ahn, M.Y., and H. Davis. 2020. Four domains of students’ sense of belonging to university. Studies in Higher Education 45, no. 3: 622–34. doi:10.1080/03075079.2018.1564902.

- Allen, K., M. Kern, D. Vella-Brodrick, and L. Waters. 2017. School values: A comparison of academic motivation, mental health promotion, and school belonging with student achievement. The Educational and Developmental Psychologist 34, no. 1: 31–47. doi: 10.1017/edp.2017.5

- Anderson, T., L. Rourke, D.R. Garrison, and W. Archer. 2001. Assessing teaching presence in a computer conferencing context. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks 5, no. 2: 1–17.

- Asikainen, H., J. Blomster, and V. Virtanen. 2018. From functioning communality to hostile behaviour: Students’ and teachers’ experiences of the teacher-student relationship in the academic community. Journal of Further and Higher Education 42, no. 5: 633–48. doi: 10.1080/0309877X.2017.1302566

- Baumeister, R.F., and M.R. Leary. 1995. The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin 117, no. 3: 497–529. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497

- Cohen, L., L. Manion, and K. Morrison. 2017. Research methods in education. 8th ed. Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781315456539.

- Cress, C.M. 2008. Creating inclusive learning communities: The role of student-faculty relationships in mitigating negative campus climate. Learning Inquiry 2, no. 2: 95–111. doi:10.1007/s11519-008-0028-2.

- Dutta, S., S. Ambwani, H. Lal, K. Ram, G. Mishra, T. Kumar, and S.B. Varthya. 2021. The satisfaction level of undergraduate medical and nursing students regarding distant preclinical and clinical teaching amidst COVID-19 across India. Advances in Medical Education and Practice 12: 113–22. doi:10.2147/AMEP.S290142.

- Edwards, M. 2019. Inclusive learning and teaching for Australian online university students with disability: A literature review. International Journal of Inclusive Education. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2019.1698066.

- Farrell, O., and J. Brunton. 2020. A balancing act: A window into online student engagement experiences. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education 17, no. 25. doi:10.1186/s41239-020-00199-x.

- Fawns, T., G. Aitken, and D. Jones. 2019. Online learning as embodied, socially meaningful experience’. Postdigital Science and Education 1, no. 2: 293–7. doi:10.1007/s42438-019-00048-9.

- Fawns, T., G. Aitken, and D. Jones, eds. 2021. Online postgraduate education in a postdigital world: Beyond technology. Cham: Springer.

- Fidalgo, P., J. Thormann, O. Kulyk, and J. Lencastre. 2020. Students’ perceptions on distance education: A multinational study. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education 17, no. 18. doi:10.1186/s41239-020-00194-2.

- Garrison, D.R., T. Anderson, and W. Archer. 2000. Critical inquiry in a text-based environment: Computer conferencing in Higher Education. The Internet and Higher Education 2: 87–105. doi:10.1016/S1096-7516(00)00016-6.

- Gillen-O’Neel, C. 2021. Sense of belonging and student engagement: A daily study of first- and continuing-generation college students. Research in Higher Education 62: 45–71. doi:10.1007/s11162-019-09570-y

- Goodenow, D. 1993. Classroom belonging among early adolescent students. The Journal of Early Adolescence 13, no. 1: 21–43. doi:10.1177/0272431693013001002.

- Gowing, A. 2019. Peer-peer relationships: A key factor in enhancing school connectedness and belonging. Educational and Child Psychology 36, no. 2: 64–77. doi: 10.53841/bpsecp.2019.36.2.64

- Groves, M., C. Sellars, J. Smith, and A. Barber. 2015. Factors affecting student engagement: A case study examining two cohorts of students attending a post-1992 university in the United Kingdom. International Journal of Higher Education 4, no. 2: 27–37. doi: 10.5430/ijhe.v4n2p27

- Hagenauer, G., and S.E. Volet. 2014. Teacher-student relationship at university: An important yet under-researched field. Oxford Review of Education 40, no. 3: 370–88. doi:10.1080/03054985.2014.921613.

- Hawkins, A., M.K. Barbour, and C.R. Graham. 2012. Everybody is their own island: Teacher disconnection in a virtual school. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning 13, no. 2: 124–44. doi:10.19173/irrodl.v13i2.967.

- Hickey, A., and S. Riddle. 2021. Relational pedagogy and the role of informality in renegotiating learning and teaching encounters. Pedagogy, Culture & Society 30 (5): 787–99, doi:10.1080/14681366.2021.1875261.

- Hodges, C., S. Moore, B. Lockee, T. Trust, and A. Bond. 2020. The difference between emergency remote teaching and online learning. Educause Review. https://er.educause.edu/articles/2020/3/the-difference-between-emergency-remote-teaching-and-online-learning (accessed September 13, 2021).

- Johnson, J.L. 2003. Distance education: The complete guide to design, delivery and improvement. New York: Teachers College Press.

- Johnson, B. 2008. Teacher-student relationships which promote resilience at school: A micro-level analysis of students’ views. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling 36, no. 4: 385–98. doi: 10.1080/03069880802364528

- Koricke, M.W., D. Abernathy, and T. Pardue. 2023. Graduate student perceptions regarding the impact of class size on effective online teaching and learning. Quarterly Review of Distance Education 24, no. 3: 1–15.

- Kriewaldt, J. 2015. Strengthening learner’s perspectives in professional standards to restore relationality as central to teaching. Australian Journal of Teacher Education 40, no. 8: 83–98. doi:10.14221/ajte.2015v40n8.5.

- Lincoln, Y.S., and E.G. Guba. 1985. Naturalistic inquiry. California: Sage.

- Martin, F., K. Budhrani, and C. Wang. 2019. Examining faculty perception of their readiness to teach online. Online Learning 23, no. 3: 97–119. doi:10.24059/olj.v23i3.1555.

- Maunder, R.E. 2018. Students’ peer relationships and their contribution to university adjustment: The need to belong in the university community. Journal of Further and Higher Education 42, no. 6: 756–68. doi:10.1080/0309877X.2017.1311996.

- May, V. 2011. Self, belonging and social change. Sociology 45, no. 3: 363–78. doi: 10.1177/0038038511399624

- McLeod, J., H.H. Yang, and Y. Shi. 2019. Student-to-student connectedness in higher education: A systematic literature review. Journal of Computing in Higher Education 31, no. 2: 426–48. doi:10.1007/s12528-019-09214-1.

- Mehall, S. 2020. Purposeful interpersonal interaction: What is it and How is it measured? Online Learning 24, no. 1: 182–204. doi:10.24059/olj.v24i1.2002.

- Mills, A., G. Durepos, and E. Wiebe. 2010. Encyclopedia of case study research. 2 vols. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Minott, M. 2022. “Teacher characteristics they value”: London upper secondary students’ perspectives. Educational Studies 48, no. 1: 33–43. doi: 10.1080/03055698.2020.1740879

- Moore, M. 1989. Editorial: Three types of interaction. American Journal of Distance Education 3, no. 2: 1–7. doi:10.1080/08923648909526659.

- Norton, A., I. Cherastidtham, and W. Mackey. 2018. Dropping out: The benefits and costs of trying university. Melbourne: Grattan Institute. https://grattan.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2018a/04/904-dropping-out-the-benefits-and-costs-of-trying-university.pdf.

- Peacock, S., and J. Cowan. 2019. Promoting senses of belonging in online learning communities of inquiry in accredited courses. Online Learning 23, no. 2: 67–81. doi:10.24059/olj.v23i2.1488.

- Pregowska, A., K. Masztalerz, M. Garlińska, and M. Osial. 2021. A worldwide journey through distance education—from the post office to virtual, augmented and mixed realities, and education during the COVID-19 pandemic. Education Sciences 11, no. 3: 118–26. doi:10.3390/educsci11030118.

- Ragusa, A., and A. Crampton. 2018. Sense of connection, identity and academic success in distance education: Sociologically exploring online learning environments. Rural Society 27, no. 2: 125–42. doi: 10.1080/10371656.2018.1472914

- Raufelder, D., L. Nitsche, S. Breitmeyer, S. Keßler, E. Herrmann, and N. Regner. 2016. Students’ perception of “good” and “bad” teachers—Results of a qualitative thematic analysis with German adolescents. International Journal of Educational Research 75: 31–44. doi:10.1016/j.ijer.2015.11.004.

- Richardson, S., and A. Radloff. 2014. Allies in learning: Critical insights into the importance of staff-student interactions in university education. Teaching in Higher Education 19, no. 6: 603–15. doi: 10.1080/13562517.2014.901960

- Rovai, A., and J. Downey. 2010. Why some distance education programs fail while others succeed in a global environment. The Internet and Higher Education 13, no. 3: 141–7. doi: 10.1016/j.iheduc.2009.07.001

- Schunk, D. 2008. Learning theories: An educational perspective. Boston: Pearson/Merrill Prentice Hall.

- Siemens, G., D. Gasevic, and S. Dawson. 2015. Preparing for the digital university: A review of the history and current state of distance, blended, and online learning. Athabasca: Athabasca University. http://linkresearchlab.org/PreparingDigitalUniversity.pdf (accessed June 19, 2021).

- Singh, V., and A. Thurman. 2019. How many ways can we define online learning? A systematic literature review of definitions of online learning (1988–2018). American Journal of Distance Education 33, no. 4: 289–306. doi: 10.1080/08923647.2019.1663082

- Stone, C. 2017. Opportunity through Online Learning: Improving student access, participation and success in higher education. Perth: National Centre for Student Equity in Higher Education. https://www.ncsehe.edu.au/publications/opportunity-online-learning-improving-student-access-participation-success-higher-education/.

- Thornberg, R., C. Forsberg, E.H. Chiriac, and Y. Bjereld. 2020. Teacher–student relationship quality and student engagement: A sequential explanatory mixed-methods study. Research Papers in Education, 840–59. doi:10.1080/02671522.2020.1864772.

- Tinto, V. 1987. Leaving college: Rethinking the causes and cures of student attrition. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- Vygotsky, L. 1962. Thought and language. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. doi:10.1037/11193-000.

- Watson, S., T. Miller, L. Davis, and P. Carter. 2010. Teachers’ perceptions of the effective teacher. Research in the Schools 17, no. 2: 11–22.