Abstract

Foster carers require high quality evidence-based psychoeducational programs to support them in the care of children with complex trauma-related difficulties. However, there is a lack of systematic development of such programs which may explain mixed results. This paper presents a detailed account of the development of a complex intervention. This program was developed to address a practice gap of evidenced-based foster care programs in the Irish context. It aims to improve foster carers' capacity to provide children with trauma-informed care and in turn improve emotional and behavioural difficulties. The framework of the Medical Research Council (MRC) for the development and evaluation of complex interventions was used to develop Fostering Connections: The Trauma-informed Foster Care Programme. A prior narrative review of the evidence base of similar programs was combined with a prior qualitative study. A Stakeholder Group provided expert feedback during the development process. The development of a promising psychoeducational programs for foster carers using the MRC framework is described

Introduction

Children who enter foster care often have experienced multiple, chronic, and prolonged experiences of abuse (Greeson et al., Citation2011). In Ireland, in 2020, about 5 children per 10,000 population aged 0–17 years were in the care equating to 5818 children, not including children in respite arrangements and separated children seeking asylum (Tusla, Citation2020). Eight hundred and thirty-seven of these children were admitted to care in 2020, of these nearly a quarter (24%) were repeated admissions (n = 200) and the remaining children (76%), it was their first-time admission (n = 637) (Tusla, Citation2020). The majority (85%) of all children admitted to alternative care were placed in foster care (n = 712). Neglect was the primary reasons for children’s first-time admission to care (43%) and the primary reason for being in care (46%). This was followed by child welfare concerns (33%, 38%). Emotional abuse (14%, 8%), physical abuse (8%, 6%), and sexual abuse (2%, 3%) were also indicated (Tusla, Citation2020). While fostering can involve high levels of personal satisfaction for foster carers (Gibbs et al., Citation2004), it is also often experienced as emotionally and psychologically demanding (Brown & Campbell, Citation2007; Whenan et al., Citation2009).

In Ireland, the supervising agency (Tusla, Child and Family Agency or a private agency) is responsible for the provision of training and support to foster carers. However, with no national training policy in place (IFCA & Tusla, Citation2017), training varies from area to area and is dependent on local resources and expertise. Preparation training is widespread and developed within each area, no published data are available. Post-approval training is provided to foster carers after they have completed the assessment process and are registered. Most often, training involves a one-off session and tends to be diverse covering a range of subjects targeting areas such as, internet safety, life story work, cultural awareness, and safe care practices in fostering. There are no data available on Irish single-session training, internationally these type of training have not produced evidence to support improvement in child difficulties (Dorsey et al., Citation2008) and are lacking in rigorous evaluation (Festinger & Baker, Citation2013). Post-approval training is also provided through multisession programs; however, this differs greatly from area to area. Data are limited, whilst there are some examples of training showing positive effects, but evidence of effectiveness is lacking (Pearce & Gibson, Citation2016).

Similar to international research, most of the multisession training programs in practice are not empirically supported (Chamberlain & Lewis, Citation2010; Kinsey & Schlosser, Citation2013). The lack of evidence to support effectiveness is often complicated by methodological limitations (Dickes et al., Citation2018). A recent meta-analysis parenting programs for foster carers report positive effects for carer outcomes: sensitive parenting, dysfunctional discipline, parenting knowledge and attitudes, and parenting stress and for the child outcome: behaviour problems (Schoemaker et al., Citation2019). The authors highlight the need for more in-depth research into effective elements of programs. In the UK, the Hear, Head and Hands Program based on a social pedagogy approach illuminated the importance of contextual issues in program impact (McDermid et al., Citation2016). Similarly, the recent evaluations of the Fostering Changes Program, also in the UK, reflect the consideration for intervention that targets the specific needs of the children and contextual issues to support effectiveness (Channon et al., Citation2020; Moody et al., Citation2020).

The need to improve the quality of foster carer support and training has been also highlighted in Ireland (Moran et al., Citation2017). Key stakeholders in foster care in Ireland echo the need for improved foster-carer training including foster carers (Devaney et al., Citation2018), multidisciplinary practitioners (Lotty, Bantry-White & Duun-Galvin, Citation2021) and children and young people with care experience (McEvoy & Smith, Citation2011). Fostering Connections, a group-based psychoeducational program was developed to address this particular practice gap (Lotty, Citation2019).

Trauma-informed care

Trauma-informed care (TIC) is an approach that aims to provide a more targeted and effective intervention for children and their families who have experienced trauma. The movement towards trauma-informed care in child welfare and protection social work practice is becoming more integrated among the practitioners (Lotty, Citation2019). Psychoeducational group-based interventions in foster care are underpinned by strong theoretical orientations (Benesh & Cui, Citation2017). Predomiantly, these have been underpinned by social learning theoryFootnote1 (Bandura, Citation1977), as well as behavioural managementFootnote2 (Brestan & Eyberg, Citation1998) and/or attachment theoryFootnote3 (Bowlby, Citation1998). TIC programs for foster carers go beyond psychosocial approaches (cognitive, behavioural, and attachment-based) in social work to a broader biopsychosocial approach (Larkin et al., Citation2014). Thus, these programs are also underpinned by the emergent body of knowledge of traumatology which reflects a broad multidisciplinary integrated perspective of from the fields of neurobiology, psychology, sociology, and social work.

Complex interventions are described as comprising of various multifaceted components that may act interdependently or independently (Faes, Reelick, Esselink, & Rikkert, Citation2010). These interacting components impact the length and complexity of the casual chain form intervention to outcome and the influence of the local context (Bleijenberg et al., Citation2018). Foster carer psychoeducational programs involve multicomponents as they seek to improve the diverse needs of children in foster care through their foster carer. Therefore, such programs are complex interventions. The research on foster care is relatively scarce (Kaasbøll et al., Citation2019) and existing research efficacy of foster-carer training programs is mixed (Solomon et al., Citation2017). In this paper, we provide a detailed account of the systematic development of Fostering Connections, a promising program (Lotty, Dunn-Galvin & Bantry-White, Citation2020) to contribute to the literature. The first author, at the time of the study, located herself as an “insider” in this research, having a dual role of doctoral researcher and experienced social work practitioner (Lotty, Citation2019). First, we describe the MRC framework and then its application to the development of Fostering Connections. We also describe the program. The evaluation stage has been completed and is reported elsewhere (Lotty, Bantry-White & Dunn-Galvin, Citation2022). The implementation stage of Fostering Connections has not been completed.

Methods

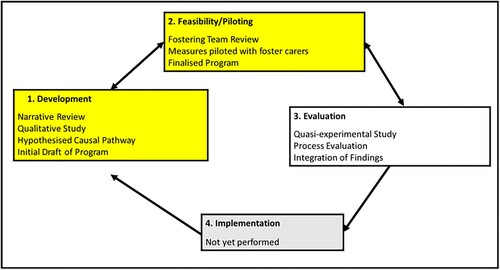

The program was developed using a study design informed by the revised guidelines for developing and evaluating complex interventions of the Medical Research Council (MRC) (Craig et al., Citation2008). The MRC framework has four stages; each stage involves key elements that adhere to a number of methodological approaches. The design allows for an iterative approach involved in the development and evaluation of a complex intervention owing to the reciprocal relationship between the stages and between the elements within each stage. Ethical approval was granted by both the Social Research Ethics Committee (Number 2017--004) in University College Cork and by the Tusla Ethics Review Group.

Development of fostering connections aligning with the MRC framework

The program emerged from a process that involved a series of non-linear key steps informed by the MRC Framework. These steps were identified in line with the elements of Stage 1 (Development) and Stage 2 (Feasibility and Piloting) of the MRC framework. These steps involved drawing from a prior narrative review (Lotty, Citation2019) and a prior qualitative study (Lotty et al., Citation2021) at Stage 1 (Development). Stage 2 (Feasibility) involved completing a review of the program by the local Fostering Social Work Team. A mixed-method approach was used to synthesise the findings of the narrative review and qualitative study (Petticrew et al., Citation2013). The use of mixed methods was particularly relevant as it strengthened the development and design of the program by ensuring results from the narrative review, which explored quantitative evidence which were extended, and complemented through qualitative findings. The qualitative study provided findings that reflected the local needs of foster carers, practices, and contextual issues specific to the Irish experience of foster care. A Stakeholder Group was also established to provide support to the research process. Multiple stakeholder input is identified as important in the research process of complex interventions (Bleijenberg et al., Citation2018), thus we sought the input from the potential providers and recipients of this program. While presented as steps, the process was iterative supported by the input of the Stakeholder Group. The results of each study are summarised separately and then the developmental process is described that synthesised the findings aligning with the MRC framework ().

Figure 1. Study's alignment with the medical research council framework. Adapted from “Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance,” by Craig et al., Citation2008, BMJ, 337, p. 6. Copyright 2008 by the BMJ Publishing Group Ltd.

Summary of findings of the prior narrative review

A prior narrative review assessed the existing knowledge of the effects of TIC programs. The review found that TIC programs for foster carers appear to increase foster carers’ capacity to provide children with trauma-informed care and reduce child trauma-related difficulties. However, the strength of evidence is limited by the methodological weaknesses of the evaluation studies. TIC programs are disseminated widely in practice but lack rigorous evaluation. The programs identified used a group-based social learning model and drew from a wide theoretical base that integrated research on early life experiences, the neurobiology of stress, attachment theory, trauma research and resilience theories within a systems framework. Three theory-based mediators that illuminated how these programs aim to develop foster carers’ capacity to provide trauma-informed care: psychoeducation, reflective engagement, and skills building. Thus, the core components of these programs included a combination of trauma psychoeducation, foster-carer-related factors (self-reflection, awareness, and self-regulation) and positive caregiving strategies that emphasised developing child regulatory and relational skills.

Summary of findings of the prior qualitative study

A prior qualitative study used focus groups with foster carers (n = 6) and multidisciplinary practitioners and clinicians (n = 21) in foster care to capture the current needs of foster carers and practice climate within foster care services in the south of Ireland (Lotty et al., Citation2021). Participants were asked for their views on the most challenging aspects of fostering, what they found supportive, would they support the development of a trauma-informed care program for foster carers, and if so what would they like incorporated into such a program and what factors would support its implementation. In total, the focus groups lasted 3 h and 34mins, with an average time of 54 min per group. About 27,446 words of data were generated. Thematic analysis revealed three themes: The need for trauma-informed care, development of trauma-informed care, and the implementation of trauma-informed care.

The stakeholder group

A stakeholder group was established to support the research process. The group consisted of key stakeholders in foster care that included professionals from areas of social work (6), nursing (1), psychology (4), workforce learning and development (2), the Irish Foster Care Association (1), the foster carer approvals committee (1), foster carers (5), a care leaver (1), academics (3), child welfare practitioners (2) and senior managers(1) creating a multidisciplinary group. Stakeholder Group meetings were convened every 6 months where members provided expert review on the research process. The members were also given the opportunity to provide feedback via email, phone, and one-to-one meetings throughout the course of the project.

Development stage of fostering connections

The developmental stage involved the three elements identified by the MRC Framework of (1) Identifying existing evidence, (2) Identify and develop theory and (3) Modelling processes and outcomes. Bleijenberg et al.'s (Citation2018) contribution to enriching the development phase of the MRC Framework guided the delineation of description and presentation of the research process.

The elements of the development stage

Problem identification and definition

Drawing on the findings of the qualitative study the target problem was identified as a gap in foster-carer training to adequately equip and prepare foster carers to care for their role of caring for children with trauma-related difficulties.

Identifying existing evidence

Drawing on the results from the prior narrative review information on the theoretical base, the program core components and outcomes measured to evaluate these programs was identified.

Identify and develop theory

This stage identified and developed the theory that underpinned the program. The narrative review findings above were supplemented by primary research from the qualitative study in providing contextual data relevant to the Irish experience. This process involved: determining the needs of the target group (foster carers) and examination of the current practices and context in which foster carers operate (the child welfare system) as set out next.

Determine needs

The qualitative study highlighted specific areas of challenge as: child trauma-related behaviours, exposure to secondary trauma, relationships with birth families, access arrangements and relationships with social workers. The qualitative study illuminated perceptions and preferences of program content, design, and how to support implementation. These findings indicated that a group work experiential-based program format would be acceptable to foster carers, the tools being discussion, case studies relevant to their experience and videos, These identified needs informed the development of a program.

Examine current practices and context

The need for more collaborative working practices with foster carers was highlighted in the qualitative study (Lotty et al., Citation2021). Findings also suggested participants were highly motivated to support the implementation of a TIC program, suggesting the development of a TIC program was timely, relevant, and acceptable to the main stakeholders in foster care.

The integration process and making sense of data were also assisted feedback from the stakeholder group. Key themes that emerged from the narrative review informed the core components of the program (Lotty, Citation2019). These were integrated with context-rich findings from the focus groups that informed the determined needs of foster carers and current local practices. The program emphasises a parallel understanding that focuses on the experiences of children in foster care and the experiences of foster caring within the context of a foster care system.

Five areas were identified that the program sought to target. These were:

increasing foster carers’ understanding of the impact of trauma on children;

increasing foster carers’ understanding of the impact of caring for children who have experienced trauma on the caregivers;

developing foster carers’ skills that address trauma impact through remedial relationships, particularly developing skills that support children with emotional and behavioural difficulties;

developing foster carers’ skills that support them managing relationships with birth families and manage access arrangements and

developing foster carers’ skills in developing collaborative working relationships with social workers.

From these five identified targets of intervention, a theoretical framework was developed. This was summarised into six core principles. Principle 1 was informed by the effectiveness of existing programs identified in the narrative review child development and foster caring. Principles 2, 3 and 4 were informed from the theoretical base of TIC which delineated the core components of TIC (child felt safety, carer-child relationships, and child coping skills). Principles 5 and 6 were informed by the specific needs of foster carers in the Irish foster care system: foster carers to build resiliency to combat the complex and stressful nature of their role, including self-care skills and having a positive outlook, managing relationships with birth families and social workers. Consideration was given to the interrelatedness of these components and how they related to projected outcomes. These six core principles were reviewed by the Stakeholder Group and subsequently refined. Minor changes were made to wording and an overarching principle (Child in Mind) was inserted to make the goal of the program more explicit ().

Table 1. The principles of fostering connections.

Modelling process and outcomes

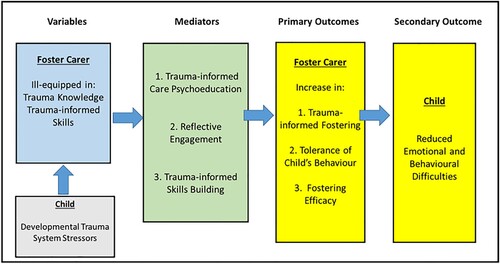

Based on the theoretical framework developed to support the program a proposed hypothesised causal pathway. It is presented here in a linear fashion, the hypothesised causal pathway was developed in a recursive process with the key principles of the program.

Trauma-informed foster care recognises that the foster carer is best placed to provide children with the greatest possible remedial impact as they are in the role of the child's primary caregiver. Thus, the focus of this program was on improving the caregiving capacity of the foster carer. Foster carer variables were identified as carers feeling ill-equipped to care for traumatised children owing to gaps in trauma knowledge and skills. Child variables identified were developmental trauma (experienced before coming into care) and system stressors- (such as separation from family and moves in foster care) related difficulties.

The theoretical basis for the program was delineated by key program mediators and a hypothesised casual pathway. Three program theory-based mediators that aim to develop trauma-informed foster carers were identified as psychoeducation, a reflective engagement and building a trauma-informed skillset. First, it was hypothesised through psychoeducation that carers will increase their knowledge and understanding of trauma impact on children and the impact of caring for children with complex needs on themselves. Second, it was hypothesised that foster carers will engage in a reflective process that will enhance and develop their reflective capacity (Fonagy & Bateman, Citation2007), increasing their awareness of their own needs and of the children they care for and thus, be more able to develop a trauma-informed mindset. Third, it was hypothesised that foster carers who undergo the program will develop a trauma-informed skillset that specifically targets the impact of developmental trauma on children.

It is hypothesised that through these three mediators foster carers will increase their knowledge of trauma-informed fostering, tolerance of child misbehaviour and fostering efficiency. Trauma-informed foster care promotes the carers’ desire to develop ways to respond more effectively to children is likely to reduce negative caregiving strategies arising from reacting to stress (Vanderfaeillie et al., Citation2013). It is also likely to reduce negative perceptions of the children (Muller et al., Citation2013) leading to greater tolerance of challenging child's behaviours and confidence in the fostering role. It is hypothesised that the program will also lead to secondary outcomes of improved child’s emotional and behavioural difficulties ().

Program design and content

Six principles were identified to support the development of an applied program consisting of six sessions. The principles provided six clear domains; each session's learning objectives was structured around a domain. In each session, attention was given to ensure the identified program mediators were facilitated. Thus, in each session, there was an emphasis on increasing understanding (psychoeducation), engagement in a reflective process (reflective engagement) and skills development (building a skillset). The targeted domains were interlinked and thus, the program by design, incorporated a level of repetition across the sessions to reinforce learning.

In each session, the content was selected and developed to reflect the targeted domain. This was informed by the findings of the narrative review and focus groups. Particular emphasis was given to using material that reflected the Irish context such as in case studies and quotes from foster carers. Some content was drawn from the RPC (Grillo & Lott, Citation2010) and a number of other attributed sources (Hughes & Golding, Citation2012; Rock et al., Citation2012; Siegel, Citation2015; Siegel & Bryson, Citation2016; Tronick & Beeghly, Citation2011). Further to this, additional content was developed through the course of this study based on practitioners’ and foster carers’ knowledge and experiences that aimed to root this program within the Irish experience ().

Table 2. Description of program content.

Feasibility stage

The elements of the feasibility stage.

In this study our main goal of stage 2 was to test the feasibility of the program and the evaluation measures for an effectiveness evaluation study (Lotty et al., Citation2020). The program was not piloted to foster carers.

Testing feasibility of the program

The local Fostering Team (n = 26) was invited to review an initial draft of the program that was developed to test for feasibility. Eighteen practitioners and supervisors attended the review. In 2015, the Resource Parents Curriculum (RPC) was piloted to foster carers by two of the practitioners who participated in the program review. The program presented included significantly adapted material from the RPC and new material. These practitioners’ input was particularly useful as they were informed by their experiences of facilitating the RPC (Lotty, Citation2019). The review found that the program content, design, and learning methods were highly acceptable and considered feasible by the Fostering Team. The changes that were recommended were: further consideration to program title that reflected a hopeful message; session on exploration of foster carer history to be scheduled after session 4; message of self-care to be linked into each session; session on “play” to be scheduled after child development section in session 4 and the final session should focus on a hopeful message. These recommendations were incorporated into a finalised version of the program and a Facilitator's Guide, slides for each session, a Toolkit and Homework Copybook were produced.

Testing evaluation measures

The standardised measures for the effectiveness study chosen were informed by the narrative review. The measures were piloted to a group of foster carers (n = 3) and refined/adjusted accordingly. These carers worked with the research team only and were not participants in the evaluation study. Changes were made to Americanised language to denote an Irish context. Estimating recruitment, retention and sample size based on prior research where attrition rates of 29% in the intervention group and 14% in the control group were reported (Purvis et al., Citation2015).

Discussion

The MRC framework supported us to systematically develop an evidenced-based program. In the case of Fostering Connections, it has successfully guided us through a complex study design that was underpinned by a mixed-methods approach.

The MRC framework supported a complex mixed-methods study design. The MRC framework recommends both quantitative and qualitative approaches to be taken in the program development stage advocating that “where possible, evidence should be combined from different sources that do not share the same weakness” (Craig et al., Citation2008, p. 3). This design helped navigate and draw from a number of sources, quantitative evidence from the narrative review, contextual data, expert multiple stakeholder views, to develop a theory-based program that reflected local context. We believe that combining these findings strengthened the program development. The delineated theoretical basis for the program supported the evaluation stage of the MRC that produced an effectiveness study (Lotty et al., Citation2020) and process evaluation (Lotty et al., Citation2021).

The feasibility stages of the MRC also helped us develop an acceptable program to providers and recipients. By seeking foster carers’ views on the design and content of the program, we hoped to contribute to the program acceptability (Marcellus, Citation2010; Spielfogel et al., Citation2011). The developed program emphasises translating complex concepts in an accessible way and comprehendible way so that foster carer can apply them to practical everyday situations. Thus, images, accessible language, repetition, role-play, relatable case studies and practicing skills were used to address this and further reinforced through the Toolkit and Homework Copybook. The program design sought to reflected atmosphere of psychological safety to promote an effective learning owing to the strong emotional content. Strategies used included following a similar format in each session, regular check-in with participants’ level of emotional stress and facilitator preparation of ground rules, structure (timing, breaks), course content, cumulative exposure to material, types of exercises, debriefing plan, how the session is ended and evaluation process.

The group work process was also an important factor in this program emphasising reflective-experiential learning & Leszcz, 2005). Experiential, self-reflective exercises and discussion were used to promote reflective engagement at an emotional level to facilitate learning (Leamnson, Citation2000). Foster carers thus were encouraged to share their experience to promote peer learning. Facilitators were also encouraged to guide foster carers through the dimensions of reflection in the experiential exercises and discussion.

Whilst the MRC framework provided us with a guide to navigate the process, the reciprocity between stages and within stages was central to the process. We were also aware that consideration of contextual issues in program design is important to the success of programs (Wells et al., Citation2012). This is particularly relevant to the field of foster care as most foster-care research is based in the U.S.A. In Ireland, the foster care system operates a care policy of long-term care when children cannot be reunified with their birth family unlike the U.S.A. (Barber & Delfabbro, Citation2005). Ensuring that the program reflected the Irish experience supported program relevance and acceptability.

This research has some limitations. The qualitative study involved a small sample within a limited timeframe. Thus, the findings of this study make generalisability to a larger population of foster carers and practitioners may not be possible. The research also was limited as it did not include children’s views. This is a consideration for future research. There also was a risk of research allegiance bias owing to the “insider” position of the first author. To minimise this risk strategies of transparency and reflexivity were employed that have been highlighted elsewhere (Ritchie et al., Citation2009). While research allegiance is associated with unintentionally reduced researcher objectivity in intervention research; the research also indicates some possible benefits (Yoder et al., Citation2019). Yoder et al. (Citation2019) suggested that research allegiance may reflect a higher level of expertise in delivering intervention. This may have been the case in this study, as the “insider” researcher brought an in-depth level of insider knowledge to the program.

To conclude, we have developed a psychoeducational program for foster carers using the MRC framework. The development of the program reflects a systematic approach that drew from multiple sources to support a promising intervention.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Maria Lotty

Maria Lotty Maria Lotty, PhD is the Senior Coordinator for Health and Social Care and a lecturer at the Centre for Adult Continuing Education, University College Cork. Her research interests are in therapeutic interventions for children and families in social work contexts, programme development and evaluation with a focus on continuous professional development for practitioners across the health, social care and education sectors. Her teaching primarily support professionals to practice trauma-informed care.

Eleanor Bantry-White

Eleanor Bantry-White Eleanor Bantry White, PhD, is the Director, Master of Social Work & Postgraduate Diploma in Social Work Studies and the Director, PhD (Arts) Social Work at University College Cork. Her research interests focus on interventions to support healthy ageing and well-being in later life and her teaching primarily supports social work practice in health care settings.

Audrey Dunn-Galvin

Audrey Dunn-Galvin Audrey Dunn Galvin, PhD, is Co-Director of the Early Years & Childhood Studies and lectures in the School of Applied Psychology, University College Cork. Her interests lie in the psychology of chronic disease, and she has been published widely in medical journals

Notes

1 Social learning theory emphasises learning through the experience of observing, modelling, and imitating the behaviours, attitudes, and emotional reactions of others.

2 Behavioural management emphasises learning prosocial behaviour through traditional reinforcement (through) rewards and punishment (through consequences).

3 Attachment theory empathises child development through positive trusting caregiving relationships that support child security, social and emotional functioning.

References

- Bandura, A. (1977). Self-Efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84, 191–215. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191

- Barber, J., & Delfabbro, P. (2005). Children's adjustment to long-term foster care. Children and Youth Services Review, 27(3), 329–340. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2004.10.010

- Benesh, A. S., & Cui, M. (2017). Foster parent training programmes for foster youth: A content review. Child & Family Social Work, 22(1), 548–559. https://doi.org/10.1111/cfs.12265

- Bleijenberg, N., Janneke, M., Trappenburg, J. C. A., Ettema, R. G. A., Sino, C. G., Heim, N., … Schuurmans, M. J. (2018). Increasing value and reducing waste by optimizing the development of complex interventions: Enriching the development phase of the medical research council (MRC) framework. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 79, 86–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.12.001

- Bowlby, J. (1998). Loss: Sadness and depression. Random House.

- Brestan, E. V., & Eyberg, S. M. (1998). Effective psychosocial treatments of conduct-disordered children and adolescents: 29 years, 82 studies, and 5,272 kids. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 27(2), 180–189. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15374424jccp2702_5

- Brown, J. D., & Campbell, M. (2007). Foster parent perceptions of placement success. Children and Youth Services Review, 29(8), 1010–1020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2007.02.002

- Chamberlain, P., & Lewis, K. (2010). Preventing placement disruptions in foster care: A research-based approach.

- Channon, S., Coulman, E., Moody, G., Brookes-Howell, L., Cannings-John, R., Lau, M., … Robling, M. (2020). Qualitative process evaluation of the fostering changes program for foster carers as part of the confidence in care randomized controlled trial. Child Abuse & Neglect, 109, 104768. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104768

- Craig, P., Dieppe, P., Macintyre, S., Michie, S., Nazareth, I., & Petticrew, M. (2008). Developing and evaluating complex interventions: The new medical research council guidance. BMJ, a1655. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.a1655

- Devaney, C., Roarty, N., Moran, L., McGregor, C., & Leinster, J. (2018). Outcomes for permanence and stability for children in long-term care in Ireland. Foster.

- Dickes, A., Kemmis-Riggs, J., & McAloon, J. (2018). Methodological challenges to the evaluation of interventions for foster/kinship carers and children: A systematic review. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 21(2), 109–145. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-017-0248-z

- Dorsey, S., Farmer, E. M., Barth, R. P., Greene, K. M., Reid, J., & Landsverk, J. (2008). Current status and evidence base of training for foster and treatment foster parents. Children and Youth Services Review, 30(12), 1403–1416. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2008.04.008

- Faes, M. C., Reelick, M. F., Esselink, R. A., & Rikkert, M. G. O. (2010). Developing and evaluating complex healthcare interventions in geriatrics: the use of the medical research council framework exemplified on a complex fall prevention intervention. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 58(11), 2212–2221.

- Festinger, T., & Baker, A. J. L. (2013). The quality of evaluations of foster parent training: An empirical review. Children and Youth Services Review, 35(12), 2147–2153. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2013.10.009

- Fonagy, P., & Bateman, A. W. (2007). Mentalizing and borderline personality disorder. Journal of Mental Health, 16(1), 83–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638230601182045

- Gibbs, I., Sinclair, I., & Wilson, K. (2004). Foster placements: Why they succeed and why they fail. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Greeson, J. K. P., Briggs, E. C., Kisiel, C. L., Layne, C. M., Ake Iii, G. S., Ko, S. J., … Pynoos, R. S. (2011). Complex trauma and mental health in children and adolescents placed in foster care: Findings from the national child traumatic stress network. Child Welfare, 90(6), 91–108.

- Grillo, C. A., Lott, D. A., Foster Care Subcommittee of the Child Welfare Committee & National Child Traumatic Stress Network. (2010). Caring for children who have experienced trauma: A workshop for resource parents—participant handbook. National Child Traumatic Stress Network.

- Hughes, D., & Golding, K. (2012). Creating loving attachments: Parenting with PACE to nurture confidence and security in the troubled child. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- IFCA & Tusla. (2017). Foster care- A national consultation with foster carers & social workers 20152016. Quality matters. https://www.tusla.ie/uploads/content/Foster_Care_-_A_National_Consultation_with_Foster_Carers_and_Social_Workers_2015-2016.pdf

- Kaasbøll, J., Lassemo, E., Paulsen, V., Melby, L., & Osborg, S. O. (2019). Foster parents’ needs, perceptions and satisfaction with foster parent training: A systematic literature review. Children and Youth Services Review.

- Kinsey, D., & Schlosser, A. (2013). Interventions in foster and kinship care: A systematic review. Clinical Child Psychology & Psychiatry, 18(3), 429–463. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359104512458204

- Larkin, H., Felitti, V. J., & Anda, R. F. (2014). Social work and adverse childhood experiences research: Implications for practice and health policy. Social Work in Public Health, 29(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/19371918.2011.619433

- Leamnson, R. (2000). Learning as biological brain change. Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning, 32(6), 34–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/00091380009601765

- Lotty, M. (2019). Enhancing foster carers’ capacity to promote placement stability: initial development and early stage evaluation of fostering connections: the Trauma-informed Foster Care Programme. Doctoral dissertation, University College Cork.

- Lotty, M., Dunn-Galvin, A., & Bantry-White, E. (2020). Effectiveness of a trauma-informed care psychoeducational program for foster carers–Evaluation of the Fostering Connections Program. Child abuse & neglect, 102, 104390.

- Lotty, M., Bantry-White, E., & Dunn-Galvin, A. (2021). A qualitative study in Ireland: Foster carers and practitioners perspectives on developing a trauma-informed care psychoeducation programme. Child Care in Practice, 1–17.

- Lotty, M., Bantry-White, E., & Dunn-Galvin, A. (2022). Towards a more comprehensive understanding of fostering connections: The trauma-informed foster care programme: a mixed methods approach with data integration. International Journal of Child, Youth and Family Studies, 13(1), 1–29.

- Marcellus, L. (2010). Supporting resilience in foster families: A model for program design that supports recruitment, retention, and satisfaction of foster families who care for infants with prenatal substance exposure. Child Welfare, 89(1), 7–29.

- McDermid, S., Holmes, L., Ghate, D., Trivedi, H., Blackmore, J., & Baker, C. (2016). Evaluation of head, heart, hands: Introducing social pedagogy into UK foster care. Final Report. Loughborough: Centre for Child and Family Research.

- McEvoy, O., & Smith, M. (2011). Listen to our voices: Hearing children and young people living in the care of the state. Government Publications.

- Moody, G., Coulman, E., Brookes-Howell, L., Cannings-John, R., Channon, S., Lau, M., … Robling, M. (2020). A pragmatic randomised controlled trial of the fostering changes programme. Child Abuse & Neglect, 108, 104646. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104646

- Moran, L., McGregor, C., & Devaney, C. (2017). Outcomes for permanence and stability for children in long-term care. Galway. The UNESCO child and family research centre. The National University of Ireland.

- Muller, R. T., Vascotto, N. A., & Konanur, S. (2013). Caregiver perceptions and expectations and child emotion regulation: A test of two mediation models predicting child psychopathology among trauma-exposed children. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma, 6(2), 126–141. https://doi.org/10.1080/19361521.2013.781089

- Pearce, C., & Gibson, J. (2016). A preliminary evaluation of the triple-A model of therapeutic care in donegal. Foster, 95.

- Petticrew, M., Rehfuess, E., Noyes, J., Higgins, J. P. T., Mayhew, A., Pantoja, T., … Sowden, A. (2013). Synthesizing evidence on complex interventions: How meta-analytical, qualitative, and mixed-method approaches can contribute. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 66(11), 1230–1243. https://doi.org/10.1080/0145935X.2013.859906

- Purvis, K. B., Razuri, E. B., Howard, A. R. H., Call, C. D., DeLuna, J. H., Hall, J. S., & Cross, D. R. (2015). Decrease in behavioral problems and trauma symptoms among at-risk adopted children following trauma-informed parent training intervention. Journal of Child and Adolescent Trauma, 8(3), 201–210. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40653-015-0055-y

- Ritchie, J., Zwi, A. B., Blignault, I., Bunde-Birouste, A., & Silove, D. (2009). Insider–outsider positions in health-development research: Reflections for practice. Development in Practice, 19(1), 106–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614520802576526

- Rock, D., Siegel, D. J., Poelmans, S. A. Y., & Payne, J. (2012). The healthy mind platter. NeuroLeadership Journal, 4, 1–23.

- Schoemaker, N. K., Wentholt, W. G., Goemans, A., Vermeer, H. J., Juffer, F., & Alink, L. R. (2020). A meta-analytic review of parenting interventions in foster care and adoption. Development and Psychopathology, 32(3), 1149–1172. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579419000798

- Siegel, D. J. (2015). Brainstorm: The Power and Purpose of the Teenage Brain: Penguin.

- Siegel, D. J., & Bryson, T. P. (2016). No-drama discipline: The whole-brain Way to calm the chaos and nurture your child's developing mind. Bantam.

- Solomon, D. T., Niec, L. N., & Schoonover, C. E. (2017). The impact of foster parent training on parenting skills and child disruptive behavior: A meta-analysis. Child Maltreatment, 22(1), 3–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077559516679514

- Spielfogel, J. E., Leathers, S. J., Christian, E., & McMeel, L. S. (2011). Parent management training, relationships with agency staff, and child mental health: Urban foster parents’ perspectives. Children and Youth Services Review, 33(11), 2366–2374. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2011.08.008

- Tronick, E., & Beeghly, M. (2011). Infants’ meaning-making and the development of mental health problems. American Psychologist, 66(2), 107–119. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021631

- Tusla, Child and Family Agency. (2020). Annual review on the adequacy of child care and family Support services available 2018. https://www.tusla.ie/uploads/content/Review_of_Adequacy_Report_2020_final_for_publication_Nov_2021.pdf

- Vanderfaeillie, J., Van Holen, F., Vanschoonlandt, F., Robberechts, M., & Stroobants, T. (2013). Children placed in long-term family foster care: A longitudinal study into the development of problem behavior and associated factors. Children and Youth Services Review, 35(4), 587–593. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2012.12.012

- Wells, M., Williams, B., Treweek, S., Coyle, J., & Taylor, J. (2012). Intervention description is not enough: Evidence from an in-depth multiple case study on the untold role and impact of context in randomised controlled trials of seven complex interventions. Trials, 13(1), 95. https://doi.org/10.1186/1745-6215-13-95

- Whenan, R., Oxlad, M., & Lushington, K. (2009). Factors associated with foster carer well-being, satisfaction, and intention to continue providing out-of-home care. Children and Youth Services Review, 31(7), 752–760. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2009.02.001

- Yoder, W. R., Karyotaki, E., Cristea, I. A., van Duin, D., & Cuijpers, P. (2019). Researcher allegiance in research on psychosocial interventions: Meta-research study protocol and pilot study. BMJ Open, 9(2), e024622. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-024622