ABSTRACT

This systematic review aimed to identify how children’s right to health, connected to the principles of protection, promotion, and participation, and from the perspectives of children, parents, and professionals in preschool, school, and healthcare has been empirically demonstrated by international scholars between 1989 and 2021. Following the standards of PRISMA-P, two searches, in 2018 and 2020, were conducted in seven databases. In total, 561 studies were found and after the screening process, which entails reviewing titles, abstracts, and full text-versions, 49 studies were finally included. A deductive qualitative content analysis, proposed by Elo and Kyngäs, was performed. According to the findings, protection was demonstrated as Being protected from harmful acts and practices and being entitled to special care and assistance. Promotion was demonstrated as Possessing of resources and Receiving of services, and participation as Being heard and listened to and Being involved in matters of concern. Conforming to the findings, although presented separately, protection, promotion, and participation could be understood as interrelated concepts. In summary, children’s right to health was demonstrated within two major fields: as the use of their own resources, and trust and as aspects provided by adults as support and safety. This is the first review of studies, published 1989–2021, identifying children's right to health through the perspectives of protection, promotion, and participation. During this period, children’s right to health has mainly been demonstrated in studies from a healthcare context. All researchers, policymakers, health workers, and politicians should include children in all decisions that concern them, to increase their participation. As children’s health is closely linked to their physical, social, and cognitive development there is a need for more studies exploring children’s right to health in preschool and school contexts in which children spend their everyday life.

Introduction

For children, the right to health depends on their own opinions and actions, as well as how the people encounter them, and in what way parents and professionals view their rights. In all encounters involving children and adults, acknowledging the child’s perspective and the child's perspective is important (Sommer et al., Citation2010; Söderbäck et al., Citation2011). According to the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child [UNCRC], every child is entitled to the highest attainable health (United Nations, Citation1989). Therefore, children need responsible adults who can claim and defend this right for them.

During the last few decades, to a large extent thanks to the adaptation of the UNCRC (United Nations, Citation1989), children’s rights have attracted significant interest among researchers in various disciplines. However, the UNCRC offers little guidance on how to carry out the responsibilities stated in the articles. One way to clarify the context could be by interpreting the UNCRC articles as principles of protection, promotion, and participation (Alderson, Citation2008). In this paper, protection is defined as the child’s right to special care and assistance, as well as the right to be protected from harmful acts and practices. Promotion refers to the possessing and receiving of and having access to resources and services from healthcare and education. Participation is defined as the child being heard, listened to, and involved in decision-making and in everyday activities.

In this systematic review, the focus is on children’s right to health in the contexts of healthcare, preschools, and schools. Preschools and schools form part of children’s everyday life. Related to their extended hours in these settings, issues of health and right to health need to be an integrated part of all activities performed. During childhood, most children occasionally encounter healthcare contexts, although for some, living with long-term or chronic illnesses, these encounters become regular occurrences. Accordingly, issues of health and the right to health are of equal importance for children in healthcare contexts. Since the ratification of the UNCRC in 1989, there has been no systematic review mapping research on children’s right to health in these contexts. Hence, this systematic review aimed to identify how children’s right to health, connected to the principles of protection, promotion, and participation, and from the perspectives of children, parents, and professionals, has been empirically demonstrated by international scholars between 1989 and 2021.

Method

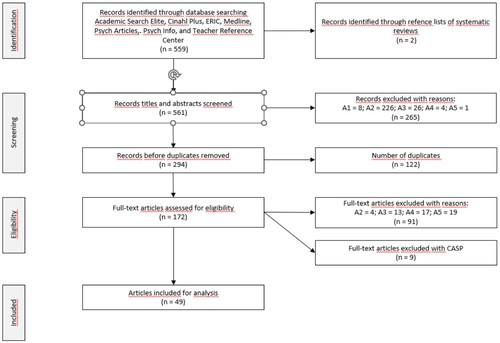

The process of this systematic review follows the standards of PRISMA-P, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis Protocols (Moher et al., Citation2015) and is registered in PROSPERO 2018 with the ID: CRD42019128810. The process described includes identification, screening, and eligibility assessment before the final inclusion and further analysis of the included records (Moher et al., Citation2009).

Identification

Initially, in the identification phase, the main search term—children’s right to health—was constructed and the generic concepts (protection, promotion, and participation) were defined. Additionally, search terms such as population (children, parents, and professionals) and contexts (healthcare, preschool, and school), including synonyms, were established (see ) and inclusion criteria were set regarding peer-review, language, and publication date. Based on the language skills within the research group, research in Danish, English, German, Norwegian, Portuguese, Spanish and Swedish was included. Publication dates were set from 1989 until 2021. The introduction phase also included the distinguishing of databases (see ). When searching the databases, the main search term—children’s right to health—was combined with each generic concept, population, and context into nine various search strings (see ). Research librarians facilitated the construction of search strings and database searches. Two searches were conducted, in September 2018 and September 2020. The nine search strings rendered 559 records in total. Among those, the systematic reviews were scrutinised for additional records and two more were identified. These 561 records were subjected to further screening and eligibility assessment but before that, reasons for exclusion were identified (see ).

Table 1. Definitions of research terms, generic concepts, population, and contexts.

Table 2. The main search term combined with the generic concept of protection and the various populations.

Table 3. The main search term combined with the generic concept promotion and the various populations.

Table 4. The main search term combined with the generic concept of participation and the various populations.

Table 5. Overview of the reasons for exclusion.

Screening process and eligibility assessment

The outcome of the identification phase and the further screening process as well as the eligibility assessment are outlined in the PRISMA flow diagram (see ). The screening process was initiated by reviewing titles and abstracts of the identified records regarding reasons for exclusion (see ). Records meeting one of these reasons were excluded. For this process, as well as the eligibility assessment, the research team was divided into pairs working in parallel with the screening. From this phase, 267 records were excluded, and 123 records identified as duplicates were removed. Records included for eligibility assessment were reviewed in the full text in relation to the exclusion criteria (). Subsequently, the remaining records (n = 172) were reviewed using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. During the screening process and eligibility assessment, the researchers had regular discussions to reach a consensus about which records to include. Eventually, 49 records were included in the final analysis (see ) of which 37 represented healthcare contexts and 12 school contexts. Preschool contexts were not represented. A semi-global representation of the records was shown: Europe = 31, Africa = 6, Asia = 5, Oceania = 5 and North America = 4. Of these 49 records, 37 studies were published during the latter part of the search period (see ).

Table 6. A summary of the included articles.

Table 7. Publishing years of the included articles.

Data analysis

A deductive qualitative content analysis as proposed by Elo and Kyngäs (Citation2008) was performed. The constructed main search term, children’s right to health, constituted the domain from which the analysis emanated. The definitions of the generic concepts were used when identifying the meaning units. Additionally, the perspectives of each population (x 3) in each context (x 3) were identified. Initially, to ensure trustworthiness, the authors jointly identified meaning units in one record. Thereafter, the authors individually identified meaning units in the records they had previously reviewed through both the screening process and eligibility assessment. Any discrepancies in the identification were rectified by discussion and mutual agreement. Consequently, a matrix was constructed for each generic concept, and the meaning units were scrutinised and positioned into the predetermined generic category, context, and population perspective to which they belonged. When needed, the placement of the meaning units was discussed among the authors until a consensus was reached. Thereafter, one of the authors (MS) coded the meaning units and finally, the codes were deduced into subcategories according to the definition of each generic concept. Following that process, discussions among the authors were made during the analysis to verify the choice of categories and subcategories.

Findings

This section presents a synthesis of how children’s right to health, related to the definitions of the generic concepts of protection, promotion, and participation, was demonstrated in the reviewed studies, from the perspective of the children (patients or pupils), families (mostly parents) and professionals in healthcare (henceforth hospital as this was the only healthcare context present in the included studies) and school contexts. As illustrated in the text below, the right to health was either distinctly or scarcely demonstrated, and occasionally it was lacking.

Children’s right to health by protection

Children’s right to health by protection was demonstrated as the child Being protected from harmful acts and practices and Being entitled to special care and assistance.

Being protected from harmful acts and practices

According to the studies, non-discriminating actions were demonstrated by children in both hospital and school contexts as essential to improve bonding (Gallagher et al., Citation2021; John-Akinola et al., Citation2014; Kajubi et al., Citation2014). Professionals viewed non-discrimination against children as a rights issue (Huus et al., Citation2016). In hospitals, children demonstrated a connectedness to and chatted easily with someone suffering from the same disease, since the children shared similar experiences. However, when socialising with healthy children, feelings of stigmatisation and discrimination were demonstrated, feelings that were especially emphasised by children in low-income countries who suffered from HIV/Aids (Kajubi et al., Citation2014; Obong’o et al., Citation2020). In schools, parents stressed the need to implement non-discriminating actions and guarantee equal rights for all pupils (Gallagher et al., Citation2021). Children with special needs demonstrated that they felt discriminated against by peers and teachers, for instance in situations where teachers assumed a direct link between disability and poor learning abilities (Åkerström et al., Citation2015). Although parents and professionals in both contexts stressed the importance of non-discriminating actions, they partially failed to fulfil their obligations. For instance, they withheld information regarding a diagnosis or sexual information, as they considered children as innocent and too young to deal with certain matters (Bhana, Citation2008; Kajubi et al., Citation2014).

In both contexts, the studies identified risks that could negatively influence children’s right to health. Being afraid and feeling pain were two major themes demonstrated by children in hospital contexts. Needle procedures, restraint, and being left alone were factors that were specifically targeted (Coyne & Kirwan, Citation2012; Harder et al., Citation2015; Munford & Sanders, Citation2015). A polarised situation was demonstrated regarding how parents dealt with these situations. Either they tried to avoid potential exposure to fear or pain, or they were demonstrated as non-supportive, not requesting alternative solutions for painful procedures (Quaye et al., Citation2019). Although aware that harmful experiences, such as restraint, could cause hospital-related fear, in some situations professionals described restraint as the sole way of providing good quality care (Kangasniemi et al., Citation2014). Apart from that, professionals described male circumcision as a risk and a violation of children’s rights (Srithanaviboonchai et al., Citation2015). Additionally, professionals in both contexts identified family-related factors, such as domestic violence, limited social relations, and work/family-related problems, as risks that could negatively impact parenting abilities and given that, the child’s position in the family (Häggman-Laitila & Euramaa, Citation2003). In schools, fear was the most pressing harmful element. Children, specifically those with special needs, associate fear with verbal attacks or being exposed by peers or teachers. Although teachers were abusive, the children kept silent due to fear of being expelled (Geiger, Citation2017).

In hospital contexts distraction, such as being close to a parent, chatting with a nurse or a doctor, playing, music, or watching TV, was demonstrated as a way for children to manage identified risks such as fear and pain (Eklund et al., Citation2020; Gilljam et al., Citation2016; Harder et al., Citation2015; Sjöberg et al., Citation2015). Furthermore, from a parental perspective, play, and especially the child being able to bring toys from home, was considered an important distraction method (Thunberg et al., Citation2016).

Being entitled to special care and assistance

In hospitals, the provision of safety was demonstrated when children met skilled professionals who treated them well (Mutambo et al., Citation2020; Sahlberg et al., Citation2020). According to parents, their safety provision was related to being close to the child (Migone et al., Citation2008). From a professional perspective, child-centred care was stressed as a key factor in safety provision and if it was not being performed, professionals demonstrated an awareness that negative consequences for the child could occur (Runeson et al., Citation2002; Sjöberg et al., Citation2015). In schools, children related safety to their physical safety, although they stressed the importance of social and emotional safety regarding bullying (Powell et al., Citation2018). Parents demonstrated safety issues in relation to pupils being unable to raise their voices. For these children to be safe, parents stressed the importance of school personnel taking good care of them (Hewitt-Taylor, Citation2009).

Children in both contexts demonstrated how they cherished their privacy and tried to create private spaces (Lambert et al., Citation2014; Obong’o et al., Citation2020; Powell et al., Citation2018). In hospitals, children identified that their privacy, and body integrity, were threatened when they were touched by professionals without consent or by being half-dressed for extensive periods during examinations (Noghabi et al., Citation2019).

Children’s right to health by promotion

Children’s right to health by promotion was demonstrated as Possessing resources and Receiving services.

Possessing resources

Children demonstrated hospital and school contexts as encouraging environments (Irving, Citation2001; John-Akinola et al., Citation2014; Kajubi et al., Citation2014; Persson et al., Citation2016; Powell et al., Citation2018), and they identified professionals as co-creating these environments by being there to help and support (Irving, Citation2001; Munford & Sanders, Citation2015) and—in school contexts—by paying attention to children’s rights and acknowledging them as individuals (Åkerström et al., Citation2015). According to parents, professionals created an encouraging environment by striving to find ways for individualised and adequate child encounters, an approach of paramount importance for children with special needs (Hewitt-Taylor, Citation2009; Przybylska et al., Citation2019; Thunberg et al., Citation2016). However, children in both contexts demonstrated that distress and anxiety contributed to transforming both hospitals and schools into discouraging environments (Powell et al., Citation2018). Additionally, in hospitals, scarce school activities and having to stay there due to advanced medical treatment not being provided elsewhere enhanced children’s feeling that hospitals were discouraging environments (Noyes, Citation2000).

Age-relevant environments were demonstrated by both children and professionals as designated places where the children could be at ease and have fun (John-Akinola et al., Citation2014; Mutambo et al., Citation2020; Sahlberg et al., Citation2020). Child-friendly communication, for instance, the use of pictures, sometimes interactive, and drawings added to this understanding and were agreed upon also by professionals (Larsson et al., Citation2019; Thunberg et al., Citation2016). However, in hospitals, the studies demonstrated that older children lacked these designated environments, which meant they were unable to meet with same-aged peers, (Coyne & Kirwan, Citation2012; Migone et al., Citation2008).

The trust in hospitals helped children, although reluctant to go there, to realise that spending time in the hospital would make them feel better. The professional’s personality was understood as a resource for creating feelings of trust (Koller et al., Citation2010; Sahlberg et al., Citation2020). Parents and professionals uniformly demonstrated that children’s trust was built on being in safe and familiar environments (Mutambo et al., Citation2020; Quaye et al., Citation2019).

Receiving services

Relationships with professionals were demonstrated by children in both contexts, building on their reliance on professionals being kind, respecting, and supporting them (Coyne, Citation2006; Gilljam et al., Citation2016; Noghabi et al., Citation2019; Powell et al., Citation2018; Sahlberg et al., Citation2020; Yıldız & Yıldız, Citation2019), an understanding also agreed upon by professionals (Anderson & Graham, Citation2015). Parents in hospital contexts described child-professional continuity as essential as that provided a mutual relation and understanding (Thunberg et al., Citation2016). It also provided adequate support from the healthcare sector (Collins & Coughlan, Citation2016). However, long stays in hospital without proper reasons resulted in children and parents feeling deprived of prosperous professional relations (Noyes, Citation2000). In schools, children demonstrated bad child-professional relationships as the result of professionals disrespecting children’s rights (Powell et al., Citation2018).

In both contexts, social/family support was demonstrated by children as being with friends and siblings, being safe, and having fun (Eklund et al., Citation2020; John-Akinola et al., Citation2014). In schools, social support was equal to inclusion which was of definite importance for children with special needs (John-Akinola et al., Citation2014; Powell et al., Citation2018), although children with communication difficulties more often had problems finding friends (Åkerström et al., Citation2015). In hospital, professional social support mostly targeted parents, teaching and helping them to care for their children (Eklund et al., Citation2020; Funkquist et al., Citation2005). In hospital contexts, reduced family support was demonstrated by children when not being listened to or comforted in adequate ways by their parents. Extensive periods away from home risked increasing feelings of exclusion and loneliness (Eklund et al., Citation2020).

Children’s right to health by participation

Children’s right to health by participation was demonstrated as Being heard and listened to and Being involved in matters of concern.

Being heard and listened to

Being noticed and involved was demonstrated by children in both contexts as essential for their well-being and participation (Anderson & Graham, Citation2015; Gilljam et al., Citation2016; Koller & Espin, Citation2018; Larsson et al., Citation2019; Sloper & Lightfoot, Citation2003). The children preferred to decide for themselves when to disclose their perspective, for instance regarding daily activities and did not wish to do so only when asked (Lightfoot & Sloper, Citation2003). They also demonstrated preferences regarding whom they confided in (Kajubi et al., Citation2014; Lightfoot & Sloper, Citation2003). Children with disabilities were demonstrated as requiring special arrangements, such as pictures and interactive devices, to allow them to speak (Thunberg et al., Citation2016), although such arrangements could be beneficial communication tools for all children. These tools allowed the children’s voices, although sometimes non-verbal, to be heard and helped to target the conversation to areas of importance for the child (Larsson et al., Citation2019). However, in situations of opposite opinions or protesting something, the children found themselves not being routinely listened to (Anderson & Graham, Citation2015; Sjöberg et al., Citation2015). In conversations, when professionals exclusively turned to the parents, the children described frustration and anger, perceiving their opinions as being of less importance (Quaye et al., Citation2019). In both contexts, parents emphasised that positive child-professional relations enabled the child’s voice to be heard (Gallagher et al., Citation2021). A child-professional power imbalance or professionals lacking proper communication skills and abilities to listen to and understand the child adequately, risked jeopardising the child being listened to (Kleiderman et al., Citation2014). Likewise, parents viewed professional disbelief in the child’s abilities, especially regarding children with disabilities or children having communication difficulties, as posing a risk of muting the child’s voice (Thunberg et al., Citation2016). Professionals demonstrated a will, and need, for acquiring adequate communication skills regarding talking to children and correctly interpreting their non-verbal expressions (Gallagher et al., Citation2021; Jenholt Nolbris & Ahlström, Citation2014; Lightfoot & Sloper, Citation2003; Mutambo et al., Citation2020; Noghabi et al., Citation2019). Like the children, professionals had a positive attitude to the use of interactive devices, both for enhancing communication and respecting the child’s rights by providing time and space (Larsson et al., Citation2019). In school contexts, the studies demonstrated that parents and professionals unanimously agreed upon all children’s right to express themselves. However, the studies demonstrated that in reality not all children were allowed to express their opinions as professionals let maturity and disability affect who could enjoy that right (Gallagher et al., Citation2021).

Being involved in matters of concern

For children, including siblings, in hospitals, preparation and information worked reassuringly to help them know what to expect (Jenholt Nolbris & Ahlström, Citation2014; Sjöberg et al., Citation2015), a view also agreed upon by parents and professionals (Bray et al., Citation2019; Kleiderman et al., Citation2014; Larsson et al., Citation2019; Przybylska et al., Citation2019; Thunberg et al., Citation2016). Lack of preparation and information resulted in feelings of worry and disbelief (Collings, Citation2011; Gilljam et al., Citation2016; Sjöberg et al., Citation2015). There was a difference in how children preferred to be informed. Some children favoured information from professionals, others from their parents (Migone et al., Citation2008). Children with communication difficulties preferred information provision through images, either interactive or traditional (Larsson et al., Citation2019). Yet another group of children preferred not to be informed as the information could remind them of earlier negative experiences (Koller & Espin, Citation2018; Norena Peña & Rojas, Citation2014; Sjöberg et al., Citation2015). Despite children’s demonstrated wish of being informed, they perceived professionals as taking minimal measures to ensure child understanding. This perception contrasted with the view of professionals who, in school and healthcare contexts, were demonstrated as emphasising use of age-relevant approaches (Eklund et al., Citation2020; Sahlberg et al., Citation2020; Thunberg et al., Citation2016) and allocating enough time for adequate preparation and information (Quaye et al., Citation2019). However, according to professionals, it could happen that children were not asked if they want to be informed or that the information provision was from an adult perspective only (Runeson et al., Citation2002).

Children in both contexts demonstrated that participating in decision-making influenced their situation (Eklund et al., Citation2020; Stålberg et al., Citation2018). However, they realised that not all decisions were for them to make, an opinion agreed upon by parents who believed children did not have enough competence to make decisions on their own (Coyne, Citation2006). Some parents even believed their children were mature enough to make their own decisions only when they reached adulthood (Kleiderman et al., Citation2014). In hospital contexts, parents and professionals demonstrated child decision-making as a child’s rights issue (Larsson et al., Citation2019; Sahlberg et al., Citation2020; Schalkers et al., Citation2016) for which age alone could not be used to determine whether the child should be allowed to participate (Coyne, Citation2006). Professionals found child decision-making was enhanced by adequate preparation and information. However, although informed, professionals mostly allowed children to have a say concerning “minor” decisions (Sahlberg et al., Citation2020; Schalkers et al., Citation2015). Children with chronic diseases could enjoy greater freedom to make their own decisions (Schalkers et al., Citation2015).

Children in hospital wished to be the main actor in the situation as they perceived themselves as having enough knowledge and skills to handle a situation (Koller & Espin, Citation2018; Machado et al., Citation2019). However, they sometimes admitted an occasional need for additional information from professionals. Parents said that the introduction of additional interactive technology in healthcare encounters transformed the child from a bystander to the main actor, a transformation that was understood as simultaneously diminishing the role and involvement of the parent (Larsson et al., Citation2019).

Discussion

This review aimed to identify how children’s right to health, connected to the principles of protection, promotion, and participation, was empirically demonstrated by international scholars between 1989 and 2021. These three concepts were chosen as they are often used to briefly summarise the content of the UNCRC as well as mentioned in the preamble of the convention (United Nations, Citation1989). However, during the analysis, it became obvious that these concepts are not isolated islands; instead, they are interrelated. From our point of view, as authors and representatives of professionals in school and healthcare contexts, we argue that protection is facilitated by participation as children, by being involved, either by themselves or with adult assistance, are enabled to highlight the need for protection from harmful acts and practices. Additionally, we view promotion and participation as interrelated as the possessing and receiving of resources are necessary prerequisites for being noticed and involved. Another way to describe this interconnectedness is borrowed from Quaye (Citation2022), who demonstrates that the principles of protection, promotion, and participation are interrelated and nested in a rather complex way. The child’s right to health is context-dependent, situational, flexible, and dependent on all actors involved. Nevertheless, our analysis was performed in line with the definition of each generic concept, and the findings section was presented accordingly.

The UNCRC, passed in November 1989, was preceded by extensive child’s rights work starting with the Geneva Declaration of the Rights of the Child in 1924, and emanated from the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948 (although the universality of the human rights is not always, or fully, applicable for children) and the Declaration of the Rights of the Child in 1959 (United Nations, Citation1989). Accordingly, the passing of the UNCRC cannot be viewed as ground-breaking news; children’s rights had been in the news for a long time. It is remarkable that most studies included in this review (range 1989–2021) were produced during the latter part of the period, i.e. from 2011 onwards (see ). Although the UNCRC is a significant child’s rights document, now ratified by 196 countries, it takes time to implement the convention. Perhaps 20 years were needed for the world to be ready to adopt, and adapt, to children’s right to health.

This review showed that children’s right to health, through the perspectives of protection, promotion, and participation, was demonstrated within two major fields. Firstly, this right was related to children’s use of their resources, such as trust, distraction, and creation of privacy. These results, mostly stemming from the children’s own perspective, show evidence of a child who wishes to be a main actor, participating in and influencing in what way the situation develops (James et al., Citation1998; Wyness, Citation2014). However, there is a risk that the adult-centric perspective negates the principle of child agency. The second main field that elicited children’s right to health through aspects provided by others (parents and/or professionals), such as support, safety, and preparation/information. This second field, less dichotomous compared to the first, described relations and positive encounters, being bi-directional and sometimes even tri-directional, i.e. child–parent, child-professional, child–child, and child–parent-professional, as contributing to support and understanding. Receiving peer support, for instance from someone suffering from the same disease, was demonstrated as valuable and helpful and could also work as protection from other groups of children, where fear of being discriminated against or stigmatised could arise. The importance of multidimensional support is not a revolutionary finding. Instead, our findings confirm the results of former research (Lygnegård et al., Citation2019; Møller Christensen et al., Citation2019). Yet another field emerging from the findings, partly an angle of what is discussed above, was that children and adults seemed to focus differently in relation to the right to health. Feelings and experiences were predominantly demonstrated in studies targeting children, whereas studies including parents and/or professionals seemed to focus on what should be done in each situation. This variation probably stems from a difference in the research questions posited in each respective study. Regardless of a potential variation in aims and/or research questions, these findings indicate the importance of focusing on both the child and the child’s perspective when working with children (Sommer et al., Citation2010; Söderbäck et al., Citation2011), to get as much knowledge as possible and to target aspects of relevance for all parties involved.

The findings indicated that relations and positive encounters enabled children to participate in communication and decision-making in both contexts. From the child’s perspective, being involved was a matter of respect. However, professionals allowing children to “have a say” is not just a way to show respect for them as individuals, but also a way to respect their human rights (United Nations, Citation1989). Child participation is essential but depends on professionals adjusting their way of working (Shier, Citation2001) and finding flexible ways for communication aligned with age, maturity, and language skills (Ford et al., Citation2018). Some of these flexible ways of communication have been described in this review, such as interactive technology, pictures, and drawings.

In this systematic review, three contexts were of interest: healthcare, preschool, and school. Preschools and schools are part of children’s everyday life, but healthcare contexts are not, at least not for most children. According to the WHO, children’s health is vital and linked to their physical, social, and cognitive development which puts focus on the importance for professionals to reflect on and acknowledge children’s rights according to the UNCRC (United Nations, Citation1989). It is meaningful to study the topic of children’s right to health within these contexts. Although an extensive search process (see ) was implemented, including several search terms, no studies describing preschool contexts were identified. School and healthcare contexts were represented; still, the number of studies in school contexts was strongly underrepresented compared to healthcare contexts. This distribution is surprising as children’s right to health is of equal importance regardless of context. Perhaps health-related issues are still predominantly viewed as relevant for healthcare contexts, while pedagogy is the most relevant for preschools and schools. Another possibility is that, within preschools and schools, other variables than those targeted in this study are used to examine health-related issues. Apart from this, the findings indicated that studies within school contexts, from all three perspectives, more often targeted children with special needs. In healthcare contexts, a broader mix of children was included in the studies, although most of whom were seven years of age or older. The perspective of the younger children was therefore lost.

Children’s right to health, as demonstrated in international studies, has been described in this paper.

However, the findings section reveals opposite scenarios as well, i.e. scenarios where the rights’ perspective was not emphasised, or missing. In summary, these scenarios concerned discrimination, lack of support, exposure and denied participation (Kajubi et al., Citation2014; Noghabi et al., Citation2019; Obong’o et al., Citation2020; Quaye et al., Citation2019). Although all included studies emphasised a child’s right perspective, some studies demonstrated that parents and professionals discriminated against children, for instance regarding age and disability (Bhana, Citation2008; Geiger, Citation2017; Kajubi et al., Citation2014; Åkerström et al., Citation2015). From the children’s perspective, the violation of the right to health was demonstrated by a lack of parental and professional support. Likewise, being ignored in conversations, and not being properly prepared and informed hindered the child from being adequately involved in a situation.

Finally, related to the geographical residence of the included studies, attention should be drawn to the fact that a variety of countries and continents were represented. However, a strong emphasis on the Western world, especially on Europe, was shown, although 196 countries worldwide have signed the UNCRC, indicating an intention of emphasising children’s rights. This review includes too few studies to state statistical assumptions. Regardless of that, we as authors would like, rhetorically, to point at a controversial question: are child issues, and more pressingly child rights issues, more noticed and emphasised within the Western world?

Methodological considerations

The trustworthiness of this review (Lincoln & Guba, Citation1985) derives from a thorough search process when identifying studies for inclusion. To further strengthen the quality of the performed searches, two research librarians were engaged throughout the entire search process. However, although multiple synonyms of relevant search terms were used, perhaps other search terms, including synonyms, could have targeted even more relevant studies, especially within preschool and school contexts. One weakness of the study could be the prolonged period used for finalising the manuscript. However, due to this extensive period, a second database search was conducted that allowed us to include more, and more recently published, studies for analysis. The credibility of the study was further strengthened by our analysis process which was characterised by a mix of joint and individual work.

Conclusion

Since the declaration of the Convention on the Rights of the Child in 1989, a growing body of studies has explored children’s right to health. We found children’s right to health to be demonstrated by the principles of protection, promotion, and participation as interrelated concepts. From the children’s perspective, the right to health is related to their resources, such as being an actor, having trust in and claiming support from others, and thus being able to participate. From the adults´ perspective, children’s right to health is related to them providing support and safety to the child. While studies with a child’s perspective focus on feelings and experiences, studies with an adult’s perspective focus on what should be done in a situation.

This systematic review identified studies related to children´s right to health mainly from the healthcare context. As children’s health is linked to their physical, social, and cognitive development, there is a need for more studies exploring children’s right to health in preschool and school, contexts that are especially important as these settings are where children spend their everyday life. However, many of the studies describing school contexts focused on children with disabilities, a subject scarcely used in healthcare-related studies. Accordingly, the right to health for children with disabilities in healthcare contexts could be of interest to further research, as well as putting a similar interest on the youngest children, a group that was invisible, in both contexts, in the reviewed studies. Furthermore, as all policymakers, health workers, and politicians should include children in all decisions that concern them, it would be interesting to consider the influence of state and community contexts in upholding/ facilitating/ negating children’s rights.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the research librarians Per Nyström and Sara Landerdahl Stridsberg, Mälardalen University, for their excellent support and guidance in the preparation for and execution of the database searches conducted for this review.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Anna Stålberg

Anna Stålberg, PhD, affiliated to the Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, and a paediatric nurse specialist at the PED, Astrid Lindgren's Children's Hospital, Stockholm. Her main research area concerns children's rights within healthcare and child participation in healthcare is an area of specific interest.

Maja Söderbäck

Maja Söderbäck has a PhD and is a Senior researcher and Associate professor at School of Health, Care and Social Sciences at Mälardalen university, Sweden. She has international experiences in children's health and paediatric nursing.

Birgitta Kerstis

Birgitta Kerstis has a PhD, paediatric nurse, and an associate professor in Nursing at Mälardalen University. Kerstis latest research focuses on the mental health of COVID-19 effects on the population, but also the mental health among older men and new parents.

Maria Harder

Maria Harder is an Associate Professor in Caring Science and Director of Research at the School of Health Care and Social Welfare, Mälardalens University, Sweden. Her individual research interest includes, to contribute to the right to health and participation among children and young people by involving them, their parents, and professionals in research, foremost in the context of child health services, preschool and psychiatric care.

Margareta Widarsson

Margareta Widarsson is a midwife, pediatric nurse, and associate professor in reproductive, perinatal, and sexual health at Mälardalen University. She has a PhD and has researched how newly graduated nurses can develop their professional competence through an introduction development program. She has also researched parental stress and support.

Lena Almqvist

Lena Almqvist is a professor of psychology at Mälardalen University, where she leads the ChiP research group. This group focuses on studying and promoting children's health and participation rights. She also works with the CHILD research program at Jönköping University. Her main research interest lies in the mental health of young children, especially those in challenging situations. Lena is keen on participatory research methods, particularly involving children as informants to better understand their participation and everyday functioning.

Marianne Velandia

Marianne Velandia is a Senior Lecturer at the School of Health, Care and Social Welfare, Division of Caring Sciences and Health Care Pedagogics, Mälardalen University.

Anna Karin Andersson

Anna Karin Andersson, PhD and physiotherapist, is a reseacher in ChiP research group at Mälardalen University and n CHILD research group at Jönköping University. Her main research interest lies in health, participation and everyday functioning in children, with a special focus on children with disabilities.

References

- Alderson, P. (2008). Young children’s rights. Believes, principles, and practice (2nd ed). Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Anderson, D. L., & Graham, A. P. (2015). Improving student wellbeing: Having a say at school. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 27(3), 348–366. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2015.1084336

- Åkerström, J., Aytar, O., & Brunnberg, E. (2015). Intra- and inter-generational perspectives on youth participation in Sweden: A study with young people as research partners. Children & Society, 29(2), 134–145. https://doi.org/10.1111/chso.12027

- Bhana, D. (2008). Sex and the right to HIV/AIDS education in early childhood. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 18(3), 439–443. https://doi.org/10.1080/14330237.2008.10820220

- Bray, L., Ford, K., Dickinson, A., Water, T., Snodin, J., & Carter, B. (2019). A qualitative study of health professionals’ views on the holding of children for clinical procedures: Constructing a balanced approach. Journal of Child Health Care, 23(1), 160–171. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367493518785777

- Collings, S. J. (2011). Professional services for child rape survivors: A child-centred perspective on helpful and harmful experiences. Journal of Child & Adolescent Mental Health, 23(1), 5–15. https://doi.org/10.2989/17280583.2011.594244

- Collins, T., & Coughlan, B. (2016). Experiences of mothers in Romania after hearing from medical professionals that their child has a disability. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 13(1), 4–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/jppi.12141

- Coyne, I. (2006). Consultation with children in hospital: Children, parents’, and nurses’ perspectives. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 15(1), 61–71. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2005.01247.x

- Coyne, I., & Kirwan, L. (2012). Ascertaining children’s wishes and feelings about hospital life. Journal of Child Health Care, 16(3), 293–304. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367493512443905

- Eklund, R., Kreicbergs, U., Alvariza, A., & Lövgren, M. (2020). Children’s self-reports about illness-related information and family communication when a parent has a life-threatening Illness. Journal of Family Nursing, 26(2), 102–110. https://doi.org/10.1177/1074840719898192

- Elo, S., & Kyngäs, H. (2008). The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62(1), 107–115. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x

- Ford, K., Dickinson, A., Water, T., Campbell, S., Bray, L., & Carter, B. (2018). Child centred care: Challenging assumptions and repositioning children and young people. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 43(Nov–Dec 2018), e39–e43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedn.2018.08.012

- Funkquist, E.-L., Carlsson, M., & Hedberg Nyqvist, K. (2005). Consulting on feeding and sleeping problems in child health care: What is at the bottom of advice to parents? Journal of Child Health Care, 9(2), 137–152. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367493505051404

- Gallagher, A. L., Murphy, C. A., Conway, P. F., & Perry, A. (2021). Establishing premises for inter-professional collaborative practice in school: Inclusion, difference, and influence. Disability and Rehabilitation, 43(20), 2909–2918. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2020.1725154

- Geiger, B. (2017). Sixth graders in Israel recount their experience of verbal abuse by teachers in the classroom. Child Abuse & Neglect, 63, 95–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2016.11.019

- Gilljam, B.-M., Arvidsson, S., Nygren, J. M., & Svedberg, P. (2016). Promoting participation in healthcare situations for children with JIA: A grounded theory study. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 11(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.3402/qhw.v11.30518

- Harder, M., Christensson, K., & Söderbäck, M. (2015). Undergoing an immunization is effortlessly, manageable, or difficult according to five-year-old children. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 29(2), 268–276. https://doi.org/10.1111/scs.12160

- Häggman-Laitila, A., & Euramaa, K. (2003). Finnish families’ need for special support as evaluated by public health nurses working in maternity and child welfare clinics. Public Health Nursing, 20(4), 328–338. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1446.2003.20410.x

- Hewitt-Taylor, J. (2009). Children who have complex health needs: Parents’ experiences of their child's education. Child: Care, Health and Development, 35(4), 521–526. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2214.2009.00965.x

- Huus, K., Dada, S., Bornman, J., & Lygnegård, F. (2016). The awareness of primary caregivers in South Africa of the human rights of their children with intellectual disabilities. Child: Care, Health and Development, 42(6), 863–870. https://doi.org/10.1111/cch.12358

- Irving, K. (2001). Australian students’ perceptions of the importance and existence of their rights. School Psychology International, 22(2), 224–240. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034301222007

- James, A., Jenk, C., & Prout, A. (1998). Theorizing childhood. Polity Press.

- Jenholt Nolbris, M., & Ahlström, B. (2014). Siblings of children with cancer – Their experiences of participating in a person-centered support intervention combining education, learning and reflection: Pre- and post-intervention interviews. European Journal of Oncology Nursing, 18(3), 254–260. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2014.01.002

- John-Akinola, Y.-O., Gavin, A., O´Higgins, E., & Gabhainn, S.-N. (2014). Taking part in school life: Views of children. Health Education, 114(1), 20–42. https://doi.org/10.1108/HE-02-2013-0007

- Kajubi, P., Bagger, S., Katahoire, A. R., Kyaddondo, D., & Whyte, S. R. (2014). Spaces for talking: Communication patterns of children on antiretroviral therapy in Uganda. Children and Youth Services Review, 45, 38–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2014.03.036

- Kangasniemi, M., Papinaho, O., & Korhonen, A. (2014). Nurses’ perceptions of the use of restraint in pediatric somatic care. Nursing Ethics, 21(5), 608–620. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733013513214

- Kleiderman, E., Knoppers, B. M., Fernandez, C. F., Boycott, K. M., Ouellette, G., Wong-Rieger, D., Adam, S., Richer, J., & Avard, D. (2014). Returning incidental findings from genetic research to children: Views of parents of children affected by rare diseases. Journal of Medical Ethics, 40(10), 691–696. https://doi.org/10.1136/medethics-2013-101648

- Koller, D., & Espin, S. (2018). Views of children, parents, and health-care providers on pediatric disclosure of medical errors. Journal of Child Health Care, 22(4), 577–590. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367493518765220

- Koller, D., Nicholas, D., Gearung, R., & Kalfa, O. (2010). Paediatric pandemic planning: Children’s perspectives and recommendations. Health & Social Care in the Community, 18(4), 369–377. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2524.2009.00907.x

- Lambert, V., Coad, J., Hicks, P., & Glacken, M. (2014). Young children’s perspectives of ideal physical design features for hospital-built environments. Journal of Child Health Care, 18(1), 57–71. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367493512473852

- Larsson, I., Svedberg, P., Arvidsson, S., Nygren, J. M., & Carlsson, I.-M. (2019). Parents’ experiences of an e-health intervention implemented in pediatric healthcare: A qualitative study. BMC Health Services Research, 19(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-019-4643-7

- Lightfoot, J., & Sloper, P. (2003). Having a say in health: Involving young people with a chronic illness or physical disability in local health services development. Children & Society, 17(4), 277–290. https://doi.org/10.1002/CHI.748

- Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Natural inquiry. Sage Publications, Inc.

- Lygnegård, F., Almqvist, L., Granlund, M., & Huus, K. (2019). Participation profiles in domestic life and peer relations as experienced by adolescents with and without impairments and long-term health conditions. Developmental Neurorehabilitation, 22(1), 27–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/17518423.2018.1424266

- Machado, M., Sousa, R., Stone, R., Bareto, M. I., Garcês, F., Cruz, C., Gomes, S., Rodrigues, M., & Guerreiro, A. I. (2019). Informed consent - Vision and perspectives of adolescents, parents and professionals: Multicentric study in six hospitals. Acta Médica Portuguesa, 32(1), 61–69. https://doi.org/10.20344/amp.10826

- Migone, M., Mc Nicholas, F., & Lennon, R. (2008). Are we following the European charter? Children, parents, and staff perceptions. Child: Care, Health and Development, 34(4), 409–417. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2214.2008.00822.x

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., & The PRISMA Group. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

- Moher, D., Shamseer, L., Clarke, M., Ghersi, D., Liberati, A., Petticrew, M., Shekelle, P., & Stewart, L. A., & PRISMA-P Group. (2015). Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Systematic Reviews, 4(1), 1. doi:10.1186/2046-4053-4-1

- Møller Christensen, B., Björk, M., Almqvist, L., & Huus, K. (2019). Patterns of support to adolescents related to disability, family situation, harassment, and economy. Child: Care, Health and Development, 45(5), 644–653. https://doi.org/10.1111/cch.12675

- Munford, R., & Sanders, J. (2015). Components of effective social work practice in mental health for young people who are users of multiple services. Social Work in Mental Health, 13(5), 415–438. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332985.2014.959239

- Mutambo, C., Shumba, K., & Hlongwana, K. W. (2020). User-provider experiences of the implementation of KidzAlive-driven child-friendly spaces in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. BMC Public Health, 20(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7712-2

- Noghabi, F. A., Yektatalab, S., Momennasab, M., Ebadi, A., & Zare, N. (2019). Exploring children's dignity: A qualitative approach. Electronic Journal of General Medicine, 16(2), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.29333/ejgm/94093

- Norena Peña, A. L., & Rojas, J. G. (2014). Ethical aspects of children’s perceptions of information-giving in care. Nursing Ethics, 21(2), 245–256. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733013484483

- Noyes, J. (2000). Enabling young ‘ventilator-dependent’ people to express their views and experiences of their care in hospital. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 31(5), 1206–1215. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.01376.x

- Obong’o, C. O., Patel, S. N., Cain, M., Kasese, C., Mupambireyi, Z., Bangani, Z., Pichon, L. C., & Miller, K. S. (2020). Suffering whether You tell or don’t tell: Perceived Re-victimization as a barrier to disclosing child sexual abuse in zimbabwe. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 29(8), 944–964. https://doi.org/10.1080/10538712.2020.1832176

- Persson, L., Haraldsson, K., & Hagquist, C. (2016). School satisfaction and social relations: Swedish schoolchildren’s improvement suggestions. International Journal of Public Health, 61(1), 83–90. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-015-0696-5

- Powell, M. A., Graham, A., Fitzgerald, R., Thomas, N., & White, N. E. (2018). Wellbeing in schools: What do students tell us? The Australian Educational Researcher, 45(4), 515–531. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-018-0273-z

- Przybylska, M. A., Burke, N., Harris, C., Kazmierczyk, M., Kenton, E., Yu, O., Coleman, H., & Joseph, S. (2019). Delivery of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child in an acute paediatric setting: An audit of information available and service gap analysis. BMJ Paediatrics Open, 3(1), e000445. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjpo-2019-000445

- Quaye, A. A. (2022). The child's best interests during hospitalization - What does it imply? [Doctoral thesis (compilation). Department of Health Sciences]. Lund University, Faculty of Medicine. https://lup.lub.lu.se/record/b164de44-1d5a-48be-80bf-e1acc208a924.

- Quaye, A. A., Coyne, I., Söderbäck, M., & Kristensson Hallström, I. (2019). Children's active participation in decision-making processes during hospitalisation: An observational study. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 28(23-24), 4525–4537. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.15042

- Runeson, I., Hallström, I., Elander, G., & Hermerén, G. (2002). Children’s needs during hospitalization: An observational study of hospitalized boys. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 8(3), 158–166. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1440-172X.2002.00356.x

- Sahlberg, S., Karlsson, K., & Darcy, L. (2020). Children's rights as law in Sweden–every health-care encounter needs to meet the child's needs. Health Expectations, 23(4), 860–869. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.13060

- Schalkers, I., Dedding, C. W. M., & Bunders, J. F. G. (2015). ‘[I would like] a place to be alone, other than the toilet’ – Children's perspectives on paediatric hospital care in The Netherlands. Health Expectations, 18(6), 2066–2078. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.12174

- Schalkers, I., Parsons, C. S., Bunders, J. F. G., & Dedding, C. (2016). Health professionals’ perspectives on children’s and young people’s participation in health care: A qualitative multihospital study. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 25(7-8), 1035–1044. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.13152

- Shier, H. (2001). Pathways to participation: Openings, opportunities, and obligations. Children & Society, 15(2), 107–117. https://doi.org/10.1002/chi.617

- Sjöberg, C., Amhliden, H., Nygren, J. M., Arvidsson, S., & Svedberg, P. (2015). The perspective of children on factors influencing their participation in perioperative care. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 24(19-20), 2945–2953. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.12911

- Sloper, P., & Lightfoot, J. (2003). Involving disabled and chronically ill children and young people in health service development. Child: Care, Health and Development, 29(1), 15–20. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2214.2003.00315.x

- Sommer, D., Pramling Samuelsson, I., & Hundeide, K. (2010). Child perspectives and children's perspectives in theory and practice. Springer.

- Söderbäck, M., Coyne, I., & Harder, M. (2011). The importance of including both a child perspective and the child’s perspective within health care settings to provide truly child-centred care. Journal of Child Health Care, 15(2), 99–106. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367493510397624

- Srithanaviboonchai, K., Pruenglampoo, B., Thaikla, K., Srirak, N., Suwanteerangkul, J., Khorana, J., Grimes, R. M., Grimes, D. E., Danthamrongkul, V., Paileeklee, S., & Pattanasutnyavong, U. (2015). Thai health care provider knowledge of neonatal male circumcision in reducing transmission of HIV and other STIs. BMC Health Services Research, 15(1), 520. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-015-1182-8

- Stålberg, A., Sandberg, A., Larsson, T., Coyne, I., & Söderbäck, M. (2018). Curious, thoughtful and affirmative—Young children's meanings of participation in healthcare situations when using an interactive communication tool. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 27(1–2), 235–246. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.13878

- Thunberg, G., Buchholz, M., & Nilsson, S. (2016). Strategies that assist children with communicative disability during hospital stay. Journal of Child Health Care, 20(2), 224–233. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367493514568298

- United Nations. (1989). The convention on the rights of the child. https://www.unmultimedia.org/searchers/yearbook/page.jsp?volume=1989&page=570&searchType=advanced

- Wyness, M. (2014). Childhood. Polity Press.

- Yıldız, I., & Yıldız, F. T. (2019). Attitudes of the nurses working in pediatric clinics towards children’s rights. Cumhuriyet Medical Journal, 41(2), 372–378. https://doi.org/10.7197/223.vi.479754