Abstract

Objective

To explore the preferences of people with memory complaints (PwMC) and their significant others regarding starting a diagnostic trajectory for dementia.

Methods

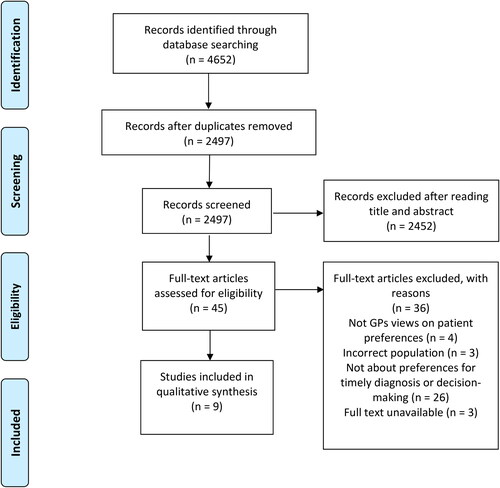

A systematic literature search was conducted in PubMed, PsycINFO, CINAHL, Web of Science, and Embase. Selection of abstracts and papers was performed independently by two researchers. Methodological quality was assessed with the Mixed Method Appraisal Tool. Result sections of the selected papers were thematically synthesized.

Results

From 2497 citations, seven qualitative studies and two mixed methods studies published between 2010 and 2020 were included. Overall quality of the studies was high to moderate. A thematic synthesis showed that preferences for starting a diagnostic trajectory arose from the feeling of needing to do something about the symptoms, beliefs on the necessity and expected outcomes of starting a diagnostic trajectory. These views were influenced by normalization or validation of symptoms, the support or wishes of the social network, interactions with health care professionals, the health status of the PwMC, and societal factors such as stigma and socioeconomic status.

Conclusion

A variety of considerations with regard to decision-making on starting a diagnostic trajectory for dementia were identified. This emphasizes the need to explore individual preferences to facilitate a timely dementia diagnosis.

Introduction

The number of people with dementia in western countries is expected to increase dramatically (Alzheimer’s Association, Citation2021). As a consequence of increased public awareness around dementia, more older people become worried about their memory or the possibility of having dementia and ask for cognitive assessment by a specialist (Brunet et al., Citation2012; Kessler et al., Citation2012). At the same time, dementia is still underdiagnosed in a lot of countries and when people seek help it often occurs in a late stage of the disease when activities in daily living are already heavily impacted (Prince et al., Citation2011). Although the high rates of under diagnoses can partly be explained by difficulties in accessing care and the complexity of healthcare systems (Devoy & Simpson, Citation2017; Samsi et al., Citation2014), this paradox reflects the difficulty of the decision to start a diagnostic process for patients and significant others (SO).

The decision to start diagnostic testing for dementia is considered preference-based (van der Flier et al., Citation2017; Verhey et al., Citation2016). In the absence of curative medicine, the advantages and disadvantages of a diagnostic process are, presumably, valued differently by each individual. Advantages of (early) diagnosis of dementia include: enabling patients and their SOs to plan their future and care (Robinson et al., Citation2015), delaying the disease progression with future effective interventions (Derksen et al., Citation2006; Watson et al., Citation2018), and providing time for the person with dementia to decide on future financial, legal and medical issues while they still have mental capacity (van den Dungen et al., Citation2014; Watson et al., Citation2018). Disadvantages of (early) diagnosis of dementia include: fear or worries about the future due to an absence of curative treatment, possible discrimination or stigmatization, and the risk of misdiagnosis in an early stage of dementia (Dubois et al., Citation2016; Mattsson et al., Citation2010).

Discussing advantages and disadvantages of dementia diagnosis with people with memory complaints (PwMC) and SOs facilitates a timely diagnosis. Timely diagnosis means that a diagnostic process is initiated at the right moment in time for the PwMC and their SO (i.e. the moment in time that they perceive they can benefit most from a diagnosis) (Brooker et al., Citation2014). To explore the ‘timeliness’ of a diagnostic trajectory, preferences of PwMCs and their SOs should be considered by healthcare professionals (HCP) before the onset of the diagnostic process (Brooker et al., Citation2014; Devine, Citation2017; Dhedhi et al., Citation2014) in a process of shared decision making (SDM). SDM assumes that decisions should be influenced by exploring and respecting “what matters most” to patients and that this exploration in turn depends on patients developing informed preferences (Elwyn et al. (Citation2012). The general practitioner (GP) is often the first HCP a PwMC visits to seek medical help (Robinson et al., Citation2015). Therefore GPs are the most obvious HCPs to explore these preferences as is recommended in the Dementia Guideline of the Dutch College of General Practitioners (Nederlands Huisartsen Genootschap, 2021). Although GPs tend to value the “rightness” of time for starting a dementia diagnostic trajectory, they also consider this a complex issue (Dhedhi et al., Citation2014). They experience barriers such as lack of time, confidence and knowledge or are held back due to their own attitudes towards early diagnosis, stigma or therapeutic nihilism (Aminzadeh et al., Citation2012; Koch & Iliffe, Citation2010; Mansfield et al., Citation2019).

Insights in patient preferences and considerations concerning starting a diagnostic trajectory for dementia could support GPs to initiate the SDM process about starting a diagnostic trajectory, and it could assist in optimizing clinical guidelines (Dirksen, Citation2014). Previous reviews have touched upon patient preferences around dementia diagnoses, specifically on systematic population screening (Martin et al., Citation2015), barriers towards help seeking (Parker et al., Citation2020) and diagnostic disclosure (van den Dungen et al., Citation2014). All have concluded that preferences around diagnosing dementia are complex and multi-factorial. They, however, do not address considerations and preferences for starting a diagnostic trajectory in case of actual memory problems.

Therefore, an integrative review is conducted to explore and map the preferences and considerations of PwMCs and their SOs regarding starting a diagnostic trajectory for dementia.

Method

This review was registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) (registration number: CRD42020190580). The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines were followed for article selection (Moher et al., Citation2010).

Design

An integrative review was conducted in line with the methodology described by Whittemore and Knafl (Citation2005). This methodology allows for the inclusion of quantitative, qualitative, and mixed-method studies. By including studies with different methodologies, all aspects of patients’ preferences could be integrated to get an overall understanding of preferences in the context of a timely dementia diagnosis.

Search strategies

Papers were searched for in the PubMed, PsychInfo, Web of Science, Embase, and CINAHL databases. The search strategy included synonyms of the following concepts: ‘timely diagnosis’, ‘dementia’, ‘preferences,’ and ‘population’. MeSH terms, free text words, and equivalent index terms were used. The search was limited to English and Dutch language peer-reviewed journals published from January 2010 onwards. The time restriction was set to capture the most relevant considerations and preferences given the rapid developments in dementia diagnostics such as the possibility for biomarker-based diagnosis (McKhann et al., Citation2011). Additionally, references of included studies were hand-searched. To optimize the search sensitivity and in line with previous studies that examine health-related preferences (Marshall et al., Citation2018) and systematic search strategies for the construct preferences (Selva et al., Citation2017; van Hoorn et al., Citation2016), a broad definition of ‘preferences’ was used to determine eligibility for inclusion: “Patient perspectives, beliefs, expectations, goals, and the processes that individuals use in considering the potential benefits, harms, costs, and inconveniences of options in relation to each other” (Montori et al., Citation2013). We aimed at data triangulation on patient preferences by including GPs views on their patients’ preferences in our search strategy. The decision to start a diagnostic trajectory is usually made in general practice and GPs have longstanding relationships with their patients and knowledge of their patient’s personal life and their preferences (Schers et al., Citation2004). The full electronic search strategy for PubMed can be found in the Appendix. The search strategies in the other databases were similar with equivalent index terms. The literature search was conducted in May 2020 and was updated in January and October 2021.

Study selection

Papers were considered for inclusion if they provided data regarding patients’ and SOs’(i.e. people that are directly involved in the decision-making process, such as spouses, children, other family members or friends) preferences for a dementia diagnosis and (shared) decision-making in that regard (). After removing duplicate papers, two researchers (IL and MH) independently excluded papers based on title and abstract. Next, the remaining papers were read full text. After each step, the researchers compared results and discussed differences. In cases of disagreement, a third researcher (CW) was consulted.

Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Table 2. Study designs, methods, findings, and themes related to patient preferences from included studies.

Quality assessment

The Mixed Method Appraisal Tool (MMAT) was used to evaluate the methodological quality of the included studies. The MMAT is a tool designed for quality appraisal in systematic reviews that include quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods studies (Pluye et al., Citation2009). The MMAT consists of two screening questions and five quality criteria for each study type (qualitative research, randomized controlled quantitative research, non-randomized controlled quantitative research, observational descriptive quantitative research, and mixed methods research). For mixed methods studies 15 quality criteria are evaluated (those for qualitative research, quantitative research and mixed methods research). The screening questions assess if the study is an empirical study and focuses on the clarity of research questions and whether the data collected are sufficient to answer the research questions. Of the corresponding quality criteria, it is evaluated whether they were met or not met. Ratings vary between 0% (no quality criteria met) and 100% (all five quality criteria met) (Pace et al., Citation2012; Pluye et al., Citation2009), and are recommended to be completed with a description of the quality of the studies. IL and MH independently assessed the included studies, discussed their individual ratings, and agreed on a final rating.

Data synthesis

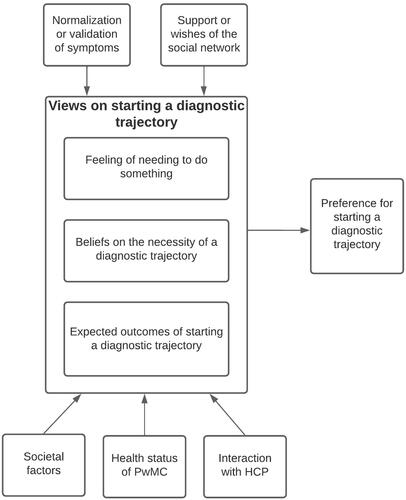

A thematic synthesis of the included studies was performed (Green & Thorogood, Citation2018; Thomas & Harden, Citation2008). Thereto, ATLAS.ti version 8.4. was used to analyze the results sections of each paper. IL and MH independently performed line-by-line coding, conceptualized the data, and identified concepts. This process was deductively led by the conceptual definition of preferences (Montori et al., Citation2013), and completed with the addition of inductive codes. Using this theoretical framework allowed us to integrate single study results on an overarching level. Together, the researchers grouped concepts into themes and subthemes. Conceptual links between the themes were identified and visually displayed in (IL and MH). In several group sessions, researchers (IL, MH, CW, MP) discussed identified concepts, themes, and conceptual links to finalize the analyses.

Results

Nine papers met the inclusion criteria (), seven qualitative studies and two mixed-methods studies (see for their characteristics). Most papers were from the UK (N = 3), followed by the Netherlands (N = 2), Canada (N = 2), Singapore (N = 1), and Germany (N = 1). Study populations consisted of PwMCs and SOs. The sample of PwMCsFootnote1 consisted of people that chose to pursue a diagnostic trajectory for their memory complaints as well as people who chose not to do so. They either visited their GP (Birt et al., Citation2020; Lee et al., Citation2018) or a memory clinic (Birt et al., Citation2020; Chrisp et al., Citation2012; Kunneman et al., Citation2017; Lohmeyer et al., Citation2020; Morgan et al., Citation2014; Visser et al., 2019). In two studies (Koehn et al., Citation2016; Mukadam et al., Citation2011) it was unclear where the diagnostic trajectory had taken place. In all papers, participants were asked to retrospectively reflect on their decision-making process to start a diagnostic trajectory for dementia.

Figure 2. Visual representation of identified themes Note. HCP = Health Care Professional, PwMC = Person with memory complaints.

Quality assessment

The quality of the studies was high to moderate, with MMAT ratings of 80 − 100% (6 studies), 60% (2 studies), and 40% (1 study). The two qualitative studies that were complemented with surveys (Kunneman et al., Citation2017; Visser et al., 2019) did not identify themselves as mixed method studies and mainly focused on the qualitative part of their study, therefore only the qualitative parts of these studies were assessed for quality criteria and used for data synthesis. For the qualitative studies with an 80-100% score the qualitative approach was adequate for the research question, findings were (mostly) adequately derived from the data and interpretation of results was substantiated by data (for example by using quotes). For the studies with an 60% score it was unclear if all results were substantiated with data and whether the data collection methods were adequate to address the research question. In the study with a 40% score, it was impossible to tell how the findings were derived from the data and if there was coherence between data sources, collection, analysis and interpretation.

Findings

Six analytic themes emerged from our data synthesis. Preferences for starting a diagnostic trajectory for dementia arose from (1) views on diagnostic trajectories. These views are influenced by (2) symptom normalization or validation, (3) the support or wishes of the social network, (4) interaction with HCPs, (5) the health status of the PwMC, and (6) societal factors such as stigmatization, cultural beliefs, and socioeconomic status (see ). See the Appendix for an extensive overview of the themes, categories, codes and illustrative quotes.

Theme 1: Views on starting diagnostic trajectories

PwMCs and SOs form a view on starting a diagnostic trajectory based on needs, beliefs on the necessity and expected outcomes of starting a diagnostic trajectory.

Feeling of needing to do something

PwMCs and SOs frequently described the feeling of ‘needing to do something’. PwMCs and SOs described this as ‘the ability to do something for your own health’ or ‘the ability to take control of the situation’(Lohmeyer et al., Citation2021; Morgan et al., Citation2014).

Mrs. Weber: I think that everyone should do something for his health or illness. No? And not simply sit it out and put the blame on other things. (Lohmeyer et al., Citation2020)

PwMCs specifically wanted to reduce uncertainty about the cause of the symptoms (Birt et al., Citation2020; Kunneman et al., Citation2017; Morgan et al., Citation2014). Furthermore, the feeling that something is off and the hope to be reassured were motives for PwMCs and SOs to pursue a diagnostic trajectory (Birt et al., Citation2020).

Beliefs on the necessity of a diagnostic trajectory

PwMCs and SOs held beliefs that determined their perceived necessity of starting a diagnostic trajectory. PwMCs did not perceive a diagnostic trajectory as necessary if they believed an HCP would not be able to help them, believed they did not need help, or prioritized their physical problems (Chrisp et al., Citation2012; Koehn et al., Citation2016; Lee et al., Citation2018).

Things that are important to her–her corns, she has very painful corns that sometimes leads her to not being able to move, and sometimes I can’t even get an appointment at the polyclinics. And then it gets worse to walk… To her, these two things matter more than her mind. In her mind, she’s fine (Lee et al., Citation2018)

These beliefs were often fueled by PwMCs’ fear of developing dementia (Birt et al., Citation2020; Chrisp et al., Citation2012). On the contrary, PwMCs and SOs who believed a diagnosis would help them move forward psychologically or that there was no harm in finding out, pursued a diagnostic trajectory (Kunneman et al., Citation2017; Morgan et al., Citation2014).

Expected outcomes of starting a diagnostic trajectory

SOs specifically had expectations on the benefits of a diagnosis, which resulted in pursuing a diagnostic trajectory. In five studies SOs expected to start (medical) treatment as soon as possible or to at least have “a foot in the door” for future therapy as a result of a diagnosis (Kunneman et al., Citation2017; Lee et al., Citation2018; Lohmeyer et al., Citation2021; Morgan et al., Citation2014; Mukadam et al., Citation2011).

Well I’d like to think there’s a medication that would help her. It helps everything else. It certainly is not going to help her a year or two down the road, it’s not going to, it’s too late. I’m hopeful that maybe there will be yet. (husband) (Morgan et al., Citation2014)

In addition, SOs were more inclined to start a diagnostic trajectory when they expected that a diagnosis would ease caregiver burden, would enable access to support and specialist care (Lee et al., Citation2018; Lohmeyer et al., Citation2021), or provide information on the prognosis of the disease (Morgan et al., Citation2014). In addition, SOs expected that a diagnosis would stimulate the PwMC to start living healthier or aid advance care planning (Birt et al., Citation2020; Lohmeyer et al., Citation2021).

Contrarily, some SOs expected a diagnostic trajectory would do more harm than good. This expectation came from respecting the PwMCs’ wish to not get tested or protecting the PwMC from the distress of diagnostic testing (Chrisp et al., Citation2012; Lee et al., Citation2018; Mukadam et al., Citation2011). Furthermore, they expected that a diagnosis would prevent the PwMC from living happy while still healthy which made them less inclined to pursue diagnostic testing (Lee et al., Citation2018), as did the expectation that a diagnosis would not contribute to future planning or to slowing down dementia (Lee et al., Citation2018; Lohmeyer et al., Citation2021). In one study, a SO explained the PwMC’s reluctance towards diagnostic testing through the expectation that a diagnosis would result in placement in an institution (Koehn et al., Citation2016).

Theme 2: Normalization or validation of symptoms

Normalizing symptoms by PwMCs and SOs weakens beliefs on the necessity of a diagnostic trajectory and the drive to do something because symptoms are not interpreted as problematic. SOs indicated that they did not believe a diagnostic trajectory was necessary if they interpreted memory complaints as part of normal aging, thought they were due to another illness, did not associate them with a disease, or perceived a low level of deterioration (Chrisp et al., Citation2012; Koehn et al., Citation2016; Lee et al., Citation2018; Mukadam et al., Citation2011). Conflicting interpretations of symptoms between the PwMC and the SO delayed starting a diagnostic trajectory (Chrisp et al., Citation2012; Koehn et al., Citation2016; Lohmeyer et al., Citation2021; Mukadam et al., Citation2011). The belief that diagnostic testing was not necessary could be strengthened when others normalized the symptoms too (Chrisp et al., Citation2012; Lohmeyer et al., Citation2021). Contrary, when symptoms are interpreted as problematic by either the PwMC, SO or others such as friends and family members, worries about them increase, which contributes to the feeling of needing to do something about the symptoms and a heightened belief on the necessity of a diagnostic trajectory. Symptoms were interpreted as problematic when changes in the PwMC’ behavior were unmanageable, abnormal, or could not be explained by alternative explanations (Birt et al., Citation2020; Koehn et al., Citation2016; Lee et al., Citation2018; Morgan et al., Citation2014; Mukadam et al., Citation2011). Moreover, the necessity of a diagnostic trajectory was acknowledged by PwMC and SO when the symptoms were validated by others (Birt et al., Citation2020; Koehn et al., Citation2016; Mukadam et al., Citation2011).

Then some a-an old friend of his noticed he was doing that. So err I thought it was about time that we went to see the doctor, our GP. (Mukadam et al., Citation2011)

Theme 3: Support or wishes of the social network

Support of the social network (i.e. close family and friends other than the SO) could be vital in taking the step to start a diagnostic trajectory. The wishes of close family and friends can influence expected outcomes or can weaken beliefs on the necessity of a diagnostic trajectory. PwMCs who were afraid to take the step to start a diagnostic trajectory alone, but were supported by their family and friends (regardless of their perception of symptoms) decided to pursue diagnostic testing (Birt et al., Citation2020), whereas a limited social network of the PwMC is often perceived as a barrier for starting diagnostic testing (Chrisp et al., Citation2012; Koehn et al., Citation2016; Morgan et al., Citation2014).

I was getting a little bit worried because I knew I was repeating things, but I wasn’t brave enough to take the first step myself so when my daughters asked if I would go to the doctor I said I would. (Birt et al., Citation2020)

On top of that, PwMCs pursued a diagnostic trajectory just for the sake of accommodating family wishes (Birt et al., Citation2020; Kunneman et al., Citation2017). On the contrary, the PwMCs’ decision to start a diagnostic trajectory was delayed when caregiving children refused to deal with the symptoms (Morgan et al., Citation2014). Moreover, one PwMC decided to not pursue a diagnostic trajectory because a relative perceived help seeking as unhelpful (Birt et al., Citation2020).

Theme 4: Interaction with HCPs

HCPs’ reactions to symptoms and communication style could heighten and weaken PwMCs’ and SOs’ beliefs on the necessity of a diagnostic trajectory. PwMCs and SOs described interactions with HCPs whereby the HCP normalized or was dismissive of their symptoms, which in most cases delayed starting a diagnostic trajectory (Birt et al., Citation2020; Chrisp et al., Citation2012; Koehn et al., Citation2016; Morgan et al., Citation2014; Mukadam et al., Citation2011).

the family doctor said ‘‘no’’ in the beginning, he did not think of it. He felt I might be too sensitive (Koehn et al., Citation2016)

However, a strong drive to reduce uncertainty on the cause of the symptoms led some PwMCs to seek a second opinion (Birt et al., Citation2020). When the HCP took concerns about memory complaints seriously, PwMCs’ and SOs’ beliefs on the necessity of starting a diagnostic trajectory were confirmed and diagnostic testing was pursued (Birt et al., Citation2020; Mukadam et al., Citation2011). Moreover, when HCPs presented decisions implicitly (instead of an option for which patients’ preferences mattered) beliefs on the necessity of starting a diagnostic trajectory could be heightened or weakened (depending on the patients’ initial beliefs) (Visser et al., 2019). The ability of the PwMC and SO to communicate their concerns, could in turn, impact the HCPs reaction and therewith PwMCs’ and SOs’ views on starting a diagnostic trajectory (Koehn et al., Citation2016). Also, the level of trust in the HCP and their perceived qualifications (e.g. age, education level) influenced whether their advice impacted views on starting a diagnostic trajectory (Birt et al., Citation2020; Koehn et al., Citation2016).

Theme 5: Health status of the PwMC

Beliefs on the necessity of starting a diagnostic trajectory could be affected by heightened or diminished awareness of symptoms due to the health status of the PwMC. PwMCs with a family history of dementia were more inclined to believe diagnostic testing is necessary in the presence of minor memory complaints (Kunneman et al., Citation2017).

It runs in the family, and that is another reason why I decided relatively quickly to do something. (Kunneman et al., Citation2017)

Also, comorbidities often provide a distraction from the memory complaints, which can affect the belief of PwMCs, SOs, and HCPs that diagnostic testing is not yet needed (Chrisp et al., Citation2012; Koehn et al., Citation2016). However, the need for medical help for physical complaints can also lead to HCPs to notice memory complaints, which in turn affect the belief that a diagnostic trajectory is necessary (Chrisp et al., Citation2012; Mukadam et al., Citation2011). In addition, a crisis (e.g. a fall or traffic accident) often strengthens the belief that diagnostic testing is necessary (Chrisp et al., Citation2012; Morgan et al., Citation2014). Other health-related factors can accelerate or decelerate the decision to start a diagnostic trajectory, sometimes regardless of the PwMCs and SOs’ initial views. For example, impaired mobility of the PwMC was a reason to defer a diagnostic trajectory (Lee et al., Citation2018).

Theme 6: Societal factors

The expected outcomes of a diagnostic trajectory could be affected by cultural perceptions on the benefits or drawbacks of a diagnosis and its societal consequences. Some PwMCs and SOs perceived a diagnostic trajectory as harmful due to a fear of being stigmatized for mental health problems (Koehn et al., Citation2016; Lohmeyer et al., Citation2021; Mukadam et al., Citation2011). Cultural beliefs on family hierarchy, the family responsibility of taking care of older family members, and ceding household duties later in life also lead to views that diagnostic testing is not beneficial (Lee et al., Citation2018; Mukadam et al., Citation2011).

You don’t want to bring in outside agencies unless you have to … because it’s intrusive … and when you can’t deal with it we’ll go to outside agencies who will help us deal with it. That’s where we’re coming from. (Mukadam et al., Citation2011)

Moreover, a lack of knowledge due to societal factors like a minority background can impact views on the necessity and accessibility of a diagnostic trajectory as mentioned by a few participants in Koehn et al. (Citation2016). Financial motives related to a diagnosis (e.g. social security income), can be a reason to pursue a diagnostic trajectory (Kunneman et al., Citation2017).

Discussion

This integrative review is the first to explore and map preferences of PwMCs and SOs on starting a diagnostic trajectory for dementia. PwMCs and SOs, who decided to pursue a diagnostic trajectory, were driven by uncertainty about symptoms, believed testing was necessary to help deal with symptoms, or expected to start treatment or have access to other forms of support after a diagnostic trajectory. PwMCs and SOs who delayed or decided to refuse a diagnostic trajectory believed they did not need help, prioritized physical problems, or expected diagnostic testing to be harmful in living (mentally) healthy. These views do not exist independently but are influenced by normalization or validation of symptoms, support or wishes of their social network, interactions with HCPs, health status of the PwMC, and societal factors such as stigmatization, cultural beliefs, and socioeconomic status.

Although in theory the identified feelings, beliefs and expectations are defined as parts of the concept preferences (Montori et al., Citation2013), in this study beliefs on the necessity and expected outcomes of starting a diagnostic trajectory appeared to be partly circular. That is, when the expected outcomes are favorable, beliefs on the necessity of starting a diagnostic trajectory are likely to be heightened and vice versa. For example, PwMCs with a family history of dementia are more inclined to believe diagnostic testing is necessary when minor memory complaints are present (Kunneman et al., Citation2017). This could be explained by expected outcomes in the form of support after diagnosis based on previous experiences with family members.

However, ‘the feeling of needing to do something’ can be seen as ‘the gut feeling’ often described as ‘doing something is better than doing nothing’ or the ‘more-is-better heuristic’ (Epstein & Peters, Citation2009). These ‘gut feelings’ do not always lead to patient preferences that are concordant with their values, because emotions can alter perceptions of quantity and value (Lichtenstein & Slovic, Citation2006). The ‘feeling of needing to do something’ might therefore be less susceptible to the identified factors because it’s a more emotion-based view.

This review highlights the challenge of finding the right timing for starting a diagnostic trajectory for both the PwMC and their SO, as their preferences can be different as was suggested by others (Groen-van de Ven et al., Citation2018; Manthorpe et al., Citation2011). Some PwMCs believed nothing could be done about the symptoms, help was not needed (Koehn et al., Citation2016; Mukadam et al., Citation2011), or a diagnosis was not perceived as beneficial for future planning (Lee et al., Citation2018; Lohmeyer et al., Citation2020), whereas SOs specifically perceived diagnostic testing as beneficial because of possibilities to start treatment or gain access to support (Kunneman et al., Citation2017; Lee et al., Citation2018; Lohmeyer et al., Citation2021; Morgan et al., Citation2014; Mukadam et al., Citation2011).

The expectations on the benefits of a diagnostic trajectory identified in our review are similar to a review that identified perceived benefits of screening such as access to treatment, financial benefits, and the ability to plan ahead in patients, clinicians, and the general public (Martin et al., Citation2015). They highlight the importance of family on the decision to undergo screening, which is similar to the role of the family in deciding on starting a diagnostic trajectory for dementia identified in our review.

Our results show that PwMCs and SOs preferences are shaped by interactions with HCPs, societal factors, and support or opinions of the social network, this is in line with the ecological perspective on patient preferences by Street et al. (Citation2012). Their ecological model suggests that patient preferences are shaped by the social, cultural, economic, and media context. The context of the health care system might influence patients’ preferences on top of the identified societal factors in our review. Access to health and support services has been experienced as complex by persons with dementia and their caregivers (Devoy & Simpson, Citation2017; Samsi et al., Citation2014), which may negatively affect expected outcomes of a diagnostic trajectory. The ecological perspective also describes that patient preferences can in turn be affected by clinical encounters, when patients’ initial preferences based on (mis)conceptions, fears, or anecdotes change when patients learn about the effectiveness of a procedure or treatment. Some of the beliefs on the necessity of testing and expected outcomes found in our review are often indeed stalled on misconceptions, experiences of others, or fear. This highlights the importance of a shared understanding of preferences between the PwMC, SO, and GP. The GP is the key professional to help patients unravel their preferences for diagnostics and care. However, exploring patient preferences in an SDM process has been reported challenging by GPs due to competing demands and priorities or a lack of skills and tools (Joseph-Williams et al., Citation2017).

Strengths and limitations

This review is strengthened by the qualitative thematic synthesis, which resulted in a comprehensive understanding of preferences influencing the decision to initiate a diagnostic trajectory for dementia. Therewith, our findings may contribute to improved SDM and more timely dementia diagnoses. Furthermore, we used a sensitive search strategy by using a broad definition of the construct preferences to increase the possibility of including all relevant studies. Last, data synthesis was performed by two researchers and validated by other researchers with broad clinical and research (including expertise on qualitative analyses and patient preferences), which enhances the credibility of our findings.

We were unable to identify studies that investigated preferences before starting a diagnostic trajectory when decisions on diagnostic testing still had to be made and outcomes were unknown. The included studies asked their participants to retrospectively reflect on their preferences after decisions were made and the consequences of their decision were known. With the majority of the participants receiving a dementia diagnosis. This may have affected their recalled experience and preferences and therewith the findings of this review. Moreover, we aimed to include studies on GP’s views on their patients’ preferences to achieve data- triangulation on the involved perspectives, however, these studies were not identified in our search. Possibly due to the sensitivity of the search terms used for ‘general practitioner’.

This review only includes papers on patient and SOs’ preferences and considerations for starting a diagnostic trajectory for dementia in Western countries. An explanation could be that patient preferences and involving patients in decision-making is less salient in non-Western countries and dementia is still largely associated with stigma (Ghooi & Deshpande, Citation2012; Mazaheri et al., Citation2014). This stresses the need for future research on this topic.

Implications for practice and suggestions for further research

This review gives insight into the considerations on starting a diagnostic trajectory for dementia, which may contribute to more timely diagnoses and SDM in three ways: (1) GPs could use the identified views on diagnostic testing to start an SDM process. For example by asking their patients and/or their SOs about what they expect the outcome of diagnostic testing will bring them. (2) The variety of presented considerations and factors around deciding on diagnostic testing for dementia, could create awareness among GPs that each patient and/or SO can have different views on diagnostic testing that are worth exploring. (3) Barriers mentioned by GPs to discuss starting a diagnostic trajectory for dementia may be solved, when this knowledge is implemented in HCPs’ (communication) training (Aminzadeh et al., Citation2012; Koch & Iliffe, Citation2010; Mansfield et al., Citation2019). Patient decision aids like the one being developed in the S-DeciDeD study can also support SDM in general practice (Linden et al., Citation2021).

Moreover, despite our attempt to understand the process of preference formation, we were only able to include studies that described patients’ retrospective views on the decision-making process for starting a diagnostic trajectory. Future research should attempt to prospectively include patients and their SOs to assess their preferences before the outcomes of their decisions are known.

Conclusions

The different considerations of PwMCs and SOs in deciding on pursuing a diagnostic trajectory for dementia identified, emphasize the relevance of pursuing a timely dementia diagnosis. Individuals have different needs and values, which should be explored together with an HCP in an SDM process. In essence, when PwMCs and SOs are deciding on whether or not to pursue a diagnostic trajectory for dementia, they are driven by the need to do something to decrease feelings of uncertainty and are led by beliefs on the necessity and expected outcomes of a diagnostic trajectory. These views are affected by whether symptoms are normalized or validated, the support or wishes of their social network, the health status of the PwMC, interactions with HCPs, and societal factors.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank all the authors of the studies included in this review. Without their work, we would not be able to form a deeper understanding of people with memory complaints and significant others’ preferences for starting a diagnostic trajectory for dementia. We furthermore wish to thank all the members of the S-DeciDeD projectgroup for their advice; Marjolein de Vugt, Frans Verhey, Ron Handels (Maastricht University/Alzheimer Centrum Limburg, Department of Psychiatry and Neuropsychology, School for Mental Health and Neuroscience (MHeNS), Maastricht, The Netherlands), Trudy van der Weijden, Job Metsemakers (Maastricht University Medical Centre, Department of Family Medicine, Care and Public Health Research Institute (CAPHRI), Maastricht, The Netherlands) and Marcel OldeRikkert (Radboud university medical center/Radboudumce Alzheimer Center, Department of Geriatric Medicine, Nijmegen, The Netherlands).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 In the result and discussion section participants of the included studies are all referred to as people with memory complaints (PwMC) because not all included participants are diagnosed with dementia. Included relatives are referred to as significant others (SO) and not caregivers, for the same reason.

References

- Alzheimer’s Association. (2021). 2021 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers & Dementia, 17(3), 80. https://doi.org/10.1002/alz.12328

- Aminzadeh, F., Molnar, F. J., Dalziel, W. B., & Ayotte, D. (2012). A review of barriers and enablers to diagnosis and management of persons with dementia in primary care. Canadian Geriatrics Journal: CGJ, 15(3), 85–94. https://doi.org/10.5770/cgj.15.42

- Birt, L., Pol, F., Charlesworth, G., Leung, P., & Higgs, P. (2020). Relational experiences of people seeking help and assessment for subjective cognitive concern and memory loss. Aging & Mental Health, 24(8), 1356–1364. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2019.1592111

- Brooker, D., La Fontaine, J., Evans, S., Bray, J., & Saad, K. (2014). Public health guidance to facilitate timely diagnosis of dementia: ALzheimer’s COoperative Valuation in Europe recommendations. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 29(7), 682–693. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.4066

- Brunet, M. D., McCartney, M., Heath, I., Tomlinson, J., Gordon, P., Cosgrove, J., Deveson, P., Gordon, S., Marciano, S. A., Colvin, D., Sayer, M., Silverman, R., & Bhattia, N. (2012). There is no evidence base for proposed dementia screening. BMJ (Clinical Research ed.), 345, e8588. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.e8588

- Chrisp, T. A., Tabberer, S., Thomas, B. D., & Goddard, W. A. (2012). Dementia early diagnosis: Triggers, supports and constraints affecting the decision to engage with the health care system. Aging & Mental Health, 16(5), 559–565. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2011.651794

- Derksen, E., Vernooij-Dassen, M., Gillissen, F., Olde Rikkert, M., & Scheltens, P. (2006). Impact of diagnostic disclosure in dementia on patients and carers: Qualitative case series analysis. Aging & Mental Health, 10(5), 525–531. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607860600638024

- Devine, M. (2017). Patient centred diagnosis of dementia: We must listen to patients’ wishes. BMJ (Clinical Research ed.), 359, j5524. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j5524

- Devoy, S., & Simpson, E. E. A. (2017). Help-seeking intentions for early dementia diagnosis in a sample of Irish adults. Aging & Mental Health, 21(8), 870–878. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2016.1179262

- Dhedhi, S. A., Swinglehurst, D., & Russell, J. (2014). Timely’ diagnosis of dementia: What does it mean? A narrative analysis of GPs’ accounts. BMJ Open, 4(3), e004439. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004439

- Dirksen, C. D. (2014). The use of research evidence on patient preferences in health care decision-making: Issues, controversies and moving forward. Expert Review of Pharmacoeconomics & Outcomes Research, 14(6), 785–794. https://doi.org/10.1586/14737167.2014.948852

- Dubois, B., Padovani, A., Scheltens, P., Rossi, A., & Dell’Agnello, G. (2016). Timely diagnosis for Alzheimer’s disease: A literature review on benefits and challenges. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease: JAD, 49(3), 617–631. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-150692

- Elwyn, G., Frosch, D., Thomson, R., Joseph-Williams, N., Lloyd, A., Kinnersley, P., Cording, E., Tomson, D., Dodd, C., Rollnick, S., Edwards, A., & Barry, M. (2012). Shared decision making: A model for clinical practice. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 27(10), 1361–1367. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-012-2077-6

- Epstein, R. M., & Peters, E. (2009). Beyond information: Exploring patients’ preferences. JAMA, 302(2), 195–197. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2009.984

- Ghooi, R. B., & Deshpande, S. R. (2012). Patients’ rights in India: An ethical perspective. Indian Journal of Medical Ethics, 9(277), e8.

- Green, J., & Thorogood, N. (2018). Qualitative methods for health research. Sage.

- Groen-van de Ven, L., Smits, C., Span, M., Jukema, J., Coppoolse, K., de Lange, J., Eefsting, J., & Vernooij-Dassen, M. (2018). The challenges of shared decision making in dementia care networks. International Psychogeriatrics, 30(6), 843–857. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610216001381

- Joseph-Williams, N., Lloyd, A., Edwards, A., Stobbart, L., Tomson, D., Macphail, S., Dodd, C., Brain, K., Elwyn, G., & Thomson, R. (2017). Implementing shared decision making in the NHS: Lessons from the MAGIC programme. BMJ (Clinical Research ed.), 357, j1744. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j1744

- Kessler, E.-M., Bowen, C. E., Baer, M., Froelich, L., & Wahl, H.-W. (2012). Dementia worry: A psychological examination of an unexplored phenomenon. European Journal of Ageing, 9(4), 275–284. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-012-0242-8

- Koch, T., & Iliffe, S., EVIDEM-ED project. (2010). Rapid appraisal of barriers to the diagnosis and management of patients with dementia in primary care: A systematic review. BMC Family Practice, 11, 52–58. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2296-11-52

- Koehn, S., Badger, M., Cohen, C., McCleary, L., & Drummond, N. (2016). Negotiating access to a diagnosis of dementia: Implications for policies in health and social care. Dementia (London, England), 15(6), 1436–1456. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301214563551

- Kunneman, M., Pel-Littel, R., Bouwman, F. H., Gillissen, F., Schoonenboom, N. S. M., Claus, J. J., van der Flier, W. M., & Smets, E. M. A. (2017). Patients’ and caregivers’ views on conversations and shared decision making in diagnostic testing for Alzheimer’s disease: The ABIDE project. Alzheimer’s & Dementia (New York, NY), 3(3), 314–322. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trci.2017.04.002

- Lee, J. J. Y., Barlas, J., Thompson, C. L., & Dong, Y. H. (2018). Caregivers’ experience of decision-making regarding diagnostic assessment following cognitive screening of older adults. Journal of Aging Research, 2018, 8352816. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/8352816

- Lichtenstein, S., & Slovic, P. (Eds.). (2006). The construction of preference. Cambridge University Press.

- Linden, I., Wolfs, C., Perry, M., Metsemakers, J., van der Weijden, T., de Vugt, M., Verhey, F. R., Handels, R., Olde Rikkert, M., Dirksen, C., & Ponds, R. W. H. M. (2021). Implementation of a diagnostic decision aid for people with memory complaints and their general practitioners: A protocol of a before and after pilot trial. BMJ Open, 11(6), e049322. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-049322

- Lohmeyer, J. L., Alpinar-Sencan, Z., & Schicktanz, S. (2021). Attitudes towards prediction and early diagnosis of late-onset dementia: A comparison of tested persons and family caregivers. Aging & Mental Health, 25(5), 832-843. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2020.1727851

- Mansfield, E., Noble, N., Sanson-Fisher, R., Mazza, D., & Bryant, J. (2019). Primary care physicians’ perceived barriers to optimal dementia care: A systematic review. The Gerontologist, 59(6), e697–e708. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gny067

- Manthorpe, J., Samsi, K., Campbell, S., Abley, C., Keady, J., Bond, J., Watts, S., Robinson, L., Gemski, A., & Warner, J. (2011). The transition from cognitive impairment to dementia: older people’s experiences. Final report. NIHR Service Delivery and Organisation programme.

- Marshall, T., Kinnard, E. N., Hancock, M., King-Jones, S., Olson, K., Abba-Aji, A., Rittenbach, K., & Vohra, S. (2018). Patient engagement, treatment preferences and shared decision-making in the treatment of opioid use disorder in adults: A scoping review protocol. BMJ Open, 8(10), e022267. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-022267

- Martin, S., Kelly, S., Khan, A., Cullum, S., Dening, T., Rait, G., Fox, C., Katona, C., Cosco, T., Brayne, C., & Lafortune, L. (2015). Attitudes and preferences towards screening for dementia: A systematic review of the literature. BMC Geriatrics, 15(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-015-0064-6

- Mattsson, N., Brax, D., & Zetterberg, H. (2010). To know or not to know: Ethical issues related to early diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Alzheimers Dis, 2010, 1–4. https://doi.org/10.4061/2010/841941

- Mazaheri, M., Eriksson, L. E., Nasrabadi, A. N., Sunvisson, H., & Heikkilä, K. (2014). Experiences of dementia in a foreign country: Qualitative content analysis of interviews with people with dementia. BMC Public Health, 14(1), 794–799. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-794

- McKhann, G. M., Knopman, D. S., Chertkow, H., Hyman, B. T., Jack, C. R., Kawas, C. H., Klunk, W. E., Koroshetz, W. J., Manly, J. J., Mayeux, R., Mohs, R. C., Morris, J. C., Rossor, M. N., Scheltens, P., Carrillo, M. C., Thies, B., Weintraub, S., & Phelps, C. H. (2011). The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 7(3), 263–269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.005

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G. (2010). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. International Journal of Surgery (London, England), 8(5), 336–334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2010.02.007

- Montori, V. M., Brito, J. P., & Murad, M. H. (2013). The optimal practice of evidence-based medicine: Incorporating patient preferences in practice guidelines. JAMA, 310(23), 2503–2504. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.281422

- Morgan, D. G., Walls-Ingram, S., Cammer, A., O’Connell, M. E., Crossley, M., Dal Bello-Haas, V., Forbes, D., Innes, A., Kirk, A., & Stewart, N. (2014). Informal caregivers’ hopes and expectations of a referral to a memory clinic. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 102, 111–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.11.023

- Mukadam, N., Cooper, C., Basit, B., & Livingston, G. (2011). Why do ethnic elders present later to UK dementia services? A qualitative study. International Psychogeriatrics, 23(7), 1070–1077. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610211000214

- Nederlands Huisarts Genootschap. (2021). NHG standaard Dementie (M21) versie 5.0 Retrieved November 11, 2021, from https://richtlijnen.nhg.org/standaarden/dementie

- Pace, R., Pluye, P., Bartlett, G., Macaulay, A. C., Salsberg, J., Jagosh, J., & Seller, R. (2012). Testing the reliability and efficiency of the pilot Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) for systematic mixed studies review. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 49(1), 47–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.07.002

- Parker, M., Barlow, S., Hoe, J., & Aitken, L. (2020). Persistent barriers and facilitators to seeking help for a dementia diagnosis: A systematic review of 30 years of the perspectives of carers and people with dementia. Int Psychogeriatr, 32(5) 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1041610219002229

- Pluye, P., Gagnon, M.-P., Griffiths, F., & Johnson-Lafleur, J. (2009). A scoring system for appraising mixed methods research, and concomitantly appraising qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods primary studies in mixed studies reviews. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 46(4), 529–546. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.01.009

- Prince, M., Bryce, R., & Ferri, C. (2011). Alzheimer’s Disease International World Alzheimer Report 2011 the benefits of early diagnosis and intervention. London: Alzheimer’s Disease International.

- Robinson, L., Tang, E., & Taylor, J. P. (2015). Dementia: Timely diagnosis and early intervention. BMJ (Clinical Research ed.), 350, h3029. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h3029

- Samsi, K., Abley, C., Campbell, S., Keady, J., Manthorpe, J., Robinson, L., Watts, S., & Bond, J. (2014). Negotiating a labyrinth: Experiences of assessment and diagnostic journey in cognitive impairment and dementia. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 29(1), 58–67. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.3969

- Schers, H., van den Hoogen, H., Bor, H., Grol, R., & van den Bosch, W. (2004). Familiarity with a GP and patients’ evaluations of care. A cross-sectional study. Family Practice, 22(1), 15–19. https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cmh721

- Selva, A., Sola, I., Zhang, Y., Pardo-Hernandez, H., Haynes, R. B., Martinez Garcia, L., Navarro, T., Schunemann, H., & Alonso-Coello, P. (2017). Development and use of a content search strategy for retrieving studies on patients’ views and preferences. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 15(1), 126. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-017-0698-5

- Street, R. L., Elwyn, G., & Epstein, R. M. (2012). Patient preferences and healthcare outcomes: An ecological perspective. Expert Review of Pharmacoeconomics & Outcomes Research, 12(2), 167–180. https://doi.org/10.1586/erp.12.3

- Thomas, J., & Harden, A. (2008). Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 8, 45. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-8-45[18616818

- van den Dungen, P., van Kuijk, L., van Marwijk, H., van der Wouden, J., Moll van Charante, E., van der Horst, H., & van Hout, H. (2014). Preferences regarding disclosure of a diagnosis of dementia: A systematic review. International Psychogeriatrics, 26(10), 1603–1618. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610214000969

- van der Flier, W. M., Kunneman, M., Bouwman, F. H., Petersen, R. C., & Smets, E. M. A. (2017). Diagnostic dilemmas in Alzheimer’s disease: Room for shared decision making. Alzheimer’s & Dementia (New York, NY), 3(3), 301–304. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trci.2017.03.008

- van Hoorn, R., Kievit, W., Booth, A., Mozygemba, K., Lysdahl, K. B., Refolo, P., Sacchini, D., Gerhardus, A., van der Wilt, G. J., & Tummers, M. (2016). The development of PubMed search strategies for patient preferences for treatment outcomes. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 16, 88. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-016-0192-5 [27473226

- Verhey, F. R., de Vugt, M. E., & Schols, J. M. (2016). Should all elderly persons undergo a cognitive function evaluation? Where is the patient’s perspective? Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 17(5), 453–455. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2016.02.016

- Visser, L. N. C., Kunneman, M., Murugesu, L., van Maurik, I., Zwan, M., Bouwman, F. H., Schuur, J., Wind, H. A., Blaauw, M. S. J., Kragt, J. J., Roks, G., Boelaarts, L., Schipper, A. C., Schooneboom, N., Scheltens, P., van der Flier, W. M., & Smets, E. M. A. (2019). Clinician-patient communication during the diagnostic workup: The ABIDE project. Alzheimer’s & Dementia (Amsterdam, Netherlands), 11, 520–528. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dadm.2019.06.001

- Watson, R., Bryant, J., Sanson-Fisher, R., Mansfield, E., & Evans, T. J. (2018). What is a ‘timely’ diagnosis? Exploring the preferences of Australian health service consumers regarding when a diagnosis of dementia should be disclosed. BMC Health Services Research, 18(1), 612. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-3409-y [30081889

- Whittemore, R., & Knafl, K. (2005). The integrative review: Updated methodology. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 52(5), 546–553. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03621.x

Appendix

Table 1. The full search strategy of electronic database PubMed.

Table 2. Themes, categories, and codes derived from data synthesis.

Table 3. Quotes from participants in primary studies to illustrate the identified themes.