ABSTRACT

This systematic literature review examines research on religiosity and happiness within the Muslim population. Earlier investigations predominantly focused on Christianity and happiness in Western countries and found a significant positive association. This literature review was conducted to investigate research exploring the relationship between religiosity and happiness among Muslims. A literature search identified 59 papers examining this relationship between the years 2000 and 2020. Standard quality assessment criteria were used to assess the quality of the selected papers. Each paper was scored by two independent researchers and several of the papers were excluded due to not meeting inclusion criteria or scoring below .55 in the quality assessment. Some 49 studies were included in this literature review, which found a positive correlation between happiness and religiosity within the Muslim population. Furthermore, most studies posited a significant relationship between the variables. This paper explores this suggested positive correlation further, highlights the limitations of the research, and discusses the implications of the findings.

Introduction

What are religiousness, religiosity, happiness, and well-being? Khenfer and Roux (Citation2012) stated that terms such as religious involvement, religious commitment, religiousness, religiosity, and religious orientation are used to refer to the same concept. Ellor and McGregor (Citation2011) described religiosity as indicating the importance of religion in an individual’s life, or the reflection of human characteristics. Hood et al. (Citation2018) described religiosity as an individual’s fundamental belief about existence. Hill (Citation2013) identified spirituality and religion as broad concepts, with a multitude of psychological constructs. Spiritual values are regarded as a central component of quality of life, by WHO (Citation2001). There are five dimensions of religiosity suggested by Glock and Stark (Citation1965). They are consequential, experiential, ideological, intellectual, and ritual. Koenig et al. (Citation2012) defined religiosity as a set of beliefs and practices relating to the transcendent. An operational definition of religiosity proposed by Hood et al. (Citation2018) stated religiosity is defined by the extent to which an individual prays, reads scriptures, attends religious services, and engages in behavioural restrictions concerning marriage and diet, prescribed by their religion. Likewise, religiosity as a concept is defined by Zullig et al. (Citation2006) as an organised belief system with established rituals and practices, acquired in places of worship (p. 255). Extrinsic and intrinsic are two dimensions of religiosity identified by Allport and Ross (Citation1967).

“Happiness” is used as an umbrella term for all that is good and is a subjective and multidimensional construct, consisting of cognitive and emotional components (Diener et al., Citation2003; Hills & Argyle, Citation2001; Veenhoven, Citation2011). Veenhoven (Citation2010) interchangeably uses happiness with the quality of life or well-being. Happiness is defined by Veenhoven (Citation2010) as the degree to which an individual evaluates one’s life as a whole positively. Happiness has also been referred to as life satisfaction, or an undifferentiated state of positive affect (e.g., Argyle, Citation1987) and effective balance between positive and negative affects (Bradburn, Citation1969). Happiness is a positive emotion that impacts psychological, cognitive, and physical mechanisms (Ziapour et al., Citation2018). Subjective well-being is considered the psychological term for what is generally referred to as happiness (Diener, Citation1998). Three possible components of subjective well-being or happiness proposed include satisfaction, positive emotions, and the absence of negative emotions (Argyle et al., Citation1995). Diener et al. (Citation2002) considered subjective well-being as consisting of low levels of negative mood, high life satisfaction, and experiencing pleasant emotions and the balance of both emotions, the positive and negative, is considered to be a significant determinant of happiness or subjective well-being. The theory of happiness proposed by Seligman (Citation2002) had three components. They were engagement, positive emotion and pleasure, and meaning.

On average, religious individuals are happier and more satisfied with life than nonreligious individuals (Stavrova et al., Citation2013). Shaver et al. (Citation1980) found a curvilinear relationship between religiosity and happiness from a sample of 2500 women in America. A significant and positive relationship was reported by Ellison et al. (Citation1989), between happiness and firm religious beliefs. Other studies show a significant positive relationship between religiosity and happiness, including McClure and Loden (Citation1982), Zukerman et al. (Citation1984), Bergin and colleagues (Citation1987), and Robbins and Francis (Citation1996). Ellison et al. (Citation1989) found that greater personal happiness, higher levels of life satisfaction, and fewer negative psychosocial consequences of traumatic life events were reported by participants with strong religious faith. In a literature review conducted by Vishkin et al. (Citation2014), they concluded that religion is a major contributor to happiness and emotion regulation. Likewise, Van Cappellen et al. (Citation2014) found positive emotion as a mediator in the relation between religion, spirituality, and well-being. In an international literature review, Tay et al. (Citation2014) concluded that religion was regarded as an important part of their lives by a majority of the people, in order to obtain happiness and peace. Most of these studies were conducted in Western countries, using different measures of religiosity, and happiness and the sample populations were mainly Christian. Abdel-Khalek (Citation2014b) explained the connection between religiosity and well-being in a Muslim context in Religiosity and Spirituality Across Cultures.

Rizvi and Hossain (Citation2016) reviewed several studies done on religiosity and well-being in different countries and religions. Of which included 35 Christianity, 31 Islam, four Judaism, three Hindu, and two Buddhism studies. All the studies on all the religions except Christianity were found to show a positive association between religiosity and well-being. There were inconsistencies found among the Christianity studies, where 12 studies showed non-significant results.

A systematic literature review was conducted by the authors to review quantitative studies among the Muslim population to identify the relationship between religiosity and happiness. It was intended to update the existing literature reviews on the relationship between religiosity and happiness and report quality studies conducted on the topic with Muslim samples. With regards to the possible finding of the studies, it is expected that all studies would show a significant positive relationship between happiness and religiosity, supporting previous literature reviews with Muslim samples (e.g., Abdel-Khalek, Citation2017, Citation2018, Citation2019; Rizvi & Hossain, Citation2016). Evidence also shows Islamic practices foster subjective well-being, including ablution (Abou El Azayem & Hedayat-Diba, Citation1994) and prayer (Husain, Citation1998; Loewenthal & Cinnirella, Citation1999). Quraishi (Citation1984) stated that Islam is not only a religion; it is also a way of life. This review will shed light on the importance of religion in people’s well-being and the vital role religiosity plays in people’s happiness. It will also highlight the different measures used to measure religiosity and happiness.

Methods

In July 2020, Google Scholar, databases such as EbscoHost, Taylor and Francis Online, and Science Direct, were searched using the keywords “religiosity,” “religion,” “religiousness”, “happiness”, “life satisfaction”, “well-being”, “Islam”, and “Muslims”. Articles with titles or abstracts, including the three main keywords, were searched for full-text articles and downloaded. Upon reviewing reference lists of articles downloaded, frequency of authors, and journals the studies were published in, those journals, articles from reference list, and authors were further examined to search for studies in the area. The aim was to search for articles that explored the relationship between religiosity and happiness among the Muslim population. The search was conducted by the first author.

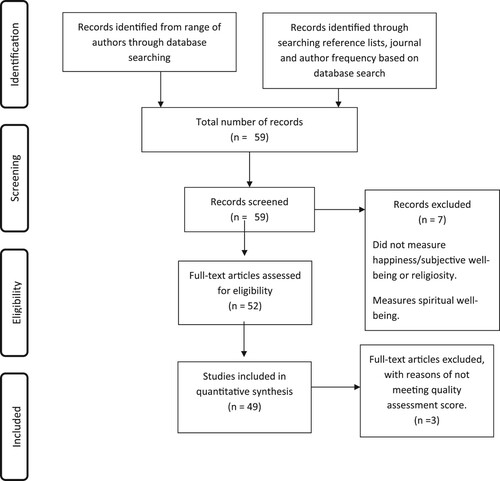

shows a PRISMA flow chart (Moher et al., Citation2009), illustrating the process of searching, screening, selecting, and the inclusion and exclusion criteria to finalise the total number of studies. Inclusion criteria were studies published between the years 2000 and 2020 on the Muslim population, where religiosity and happiness were variables tested, and which scored above .55 on quality assessment, and were published in the English language. Standard Quality Assessment Criteria for Evaluating Primary Research Papers from a Variety of Fields (Kmet et al., Citation2004) were used to assess the quality of the selected papers. Two reviewers (the first two authors) scored the papers, and any differences were resolved by discussion and mutual agreement.

Initially, 59 papers were identified and downloaded, of which seven were excluded as they did not measure happiness, subjective well-being, and religiosity. The remaining 52 articles were access for quality and three were excluded as they did not reach the cut-off score of .55. Therefore, a total of 49 papers remaining were included in the review. All of the 49 papers are quantitative in nature.

Analysis

A descriptive evaluation of each study is presented in and . It includes the country where the research was conducted, participants’ details, the measures used, and the findings. The 49 studies that fit to the inclusion criteria were reviewed, analysed, and categorised with respect to recurrent trends and themes. These categories were sample population and participants, measures used, and other parameters measured. Other literature supporting the themes are is also discussed.

Table 1. Shows a summary of the research conducted only with Muslim populations.

Table 2. Shows a summary of the research conducted with Muslim samples and other groups.

Results

A total of 49 studies were identified as eligible. The description of these studies can be seen in and . The majority of the studies were quantitative. Only one study employed mixed methods (Devine et al., Citation2019).

Sample population and participants

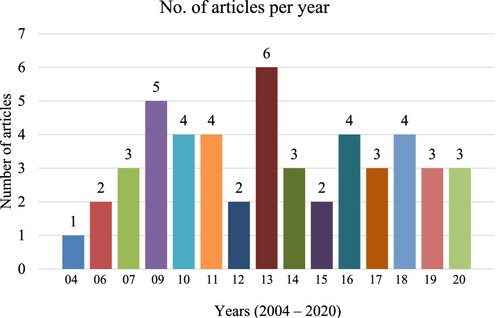

Thirty-six studies had used only Muslim samples (), and 13 studies had Muslim samples with another religious group or a different country (). The average number of participants used in the studies was 829.3. The lowest number of participants was 50 (Gulamhussein & Eaton, Citation2015), and the highest was 7211 (Abdel-Khalek, Citation2009). Except for the studies done by Momtaz et al. (Citation2011), Achour et al. (Citation2014), and Gulamhussein and Eaton (Citation2015), all other studies had both male and female participants. shows the years and number of articles published in the respective years included in the review.

Most of the studies (N = 39) had used a student sample population to collect data (e.g., Abdel Khalek Citation2007; Fatima et al., Citation2018). One study (Stuart & Ward, Citation2018) used a Muslim immigrant youth sample in New Zealand, another individuals and relatives of those who were in a car accident (Ashkanani, Citation2009). Another used participants of 60 years or older (Momtaz et al., Citation2011) and one used adolescents (Baroun, Citation2006). and also show the papers included in the review with the sample size and the countries in which the studies were conducted. Sixteen studies had samples from Kuwait and four studies used samples from the USA of which three are comparison studies with Kuwait (Abdel-Khalek & Lester, Citation2007, Citation2010b, Citation2013). Although the religious practices may have individual differences, Thorson et al. (Citation1997) reported religious motivation to be high in Kuwait, compared with the USA. Using data from the World Database of Happiness, Mookerjee and Baron (Citation2005) confirmed that happiness levels across different countries are greatly impacted by religion and culture.

Measures used

Both religiosity and happiness are multidimensional. Therefore, how they are operationalised and conceptualised in studies differs. Religiosity in some studies is measured by religious commitment (Achour et al., Citation2017), religious orientation (Aghababei et al., Citation2016; Bayani, Citation2014), religious attitude (Francis et al., Citation2016; Jesarati et al., Citation2013; Tekke et al., Citation2018) religious practices (Stuart & Ward, Citation2018), religious identity (Hashemi et al., Citation2020; Stuart & Ward, Citation2018), while others have used the strength of religious faith (Achour et al., Citation2014) and affiliation (Suhail & Chaudhry, Citation2004), intrinsic religious motivation (Abdel-Khalek & Lester, Citation2009; Abdel-Khalek & Singh, Citation2019; Abdel-Khalek & Tekke, Citation2019; Baroun, Citation2006), frequency of prayer (Abu Rahim, Citation2013; Saleem et al., Citation2020), individual’s concern and involvement with spiritual issues (Abu-Raiya & Agbaria, Citation2016), and religious belief, practices, and the use of positive religious coping strategies (Fatima et al., Citation2018)

Likewise, happiness is measured through satisfaction with life (Abdel-Khalek, Citation2011b, Citation2012b, Citation2013b; Abu Rahim, Citation2013; Suhail & Chaudhry, Citation2004), subjective happiness and positive and negative emotions (Abu-Raiya & Agbaria, Citation2016), psychological well-being (Ashkanani, Citation2009; Fatima et al., Citation2018; Hashemi et al., Citation2020), anxiety (Abdel-Khalek, Citation2011a; Abdel-Khalek & Lester, Citation2010b), and depression (Bayani, Citation2014).

Several studies used the Oxford Happiness Inventory (OHI) (e.g., Abdel-Khalek, Citation2011b, Bayani, Citation2014), and two studies used the OHQ to measure happiness (Abdel-Khalek & Lester, Citation2010b; Jesarati et al., Citation2013). The OHI (Argyle et al., Citation1989) is one of the main scales used to measure happiness. All studies used self-report scales to measure additional variables including, religiosity, level of happiness, satisfaction with life, and mental health.

Several studies used single-item measures (e.g., Hossain & Rizvi, Citation2017; Saleem et al., Citation2020), to measure religiosity, happiness, life satisfaction, mental and physical health. When conducting large-scale surveys in communities, single-item measures are more economical and useful, with time limits. A single-item happiness scale was found to be viable in a cross-cultural comparison, as well as in a community survey and research project (Abdel-Khalek, Citation2006b). There are limitations to such scales. They cannot provide sufficient data to evaluate the internal consistency of the scale and have limited score ranges. They cannot cover the influence of social desirability and the complexity of the construct being measured (Gillings & Joseph, Citation1996), nor can factor analysis be applied to their items (Abdel-Khalek, Citation2006b). However, several studies (Wills, Citation2009; Zullig et al., Citation2006) have supported the merits of using single-item, self-rating scales. When there are a large number of scales and items, this type of measure could potentially be beneficial, as participants might not be willing to complete a lengthy questionnaire. A single-item, self-rating scale is based upon the assumption that the most relevant meaning that comes to mind will be assumed by participants, with regards to the subject of the question and answered accordingly (Wills, Citation2009). Cummins (Citation1995) found that reliable and valid data could be yielded by using single-item, self-rated measures. More than 40 studies conducted with single-item self-rating scales showed the same results as multiple-item questionnaires (e.g., Abdel-Khalek, Citation2012a).

Other parameters measured

While examining the relationship between religiosity and happiness often age (Abu Rahim, Citation2013), gender (Ashkanani, Citation2009), income (Momtaz et al., Citation2011), education (Abu Rahim, Citation2013), marital status (Momtaz et al., Citation2011), life satisfaction (Aghababei et al., Citation2016), love of life (Abdel Khalek & Singh, Citation2019), personality (Francis et al., Citation2016), physical health (Abdel-Khalek & Tekke, Citation2019) depression (Stuart & Ward, Citation2018), meaning in life, purpose in life (Aghababei et al., Citation2016), self-esteem (Abdel-Khalek & Lester, Citation2013), optimism and pessimism (Abdel-Khalek & Naceur, Citation2007), and anxiety (Baroun, Citation2006) were measured at the same time.

Several studies reported social support, sense of meaning and purpose in life, healthier lifestyle, generativity, and individual coping mechanism, such as prayer and faith as individual difference factors which mediate the relationship between religiosity and subjective well-being (Compton, Citation2005; Diener et al., Citation2011; Donahue & Benson, Citation1995; Pargament, Citation1997; Pargament et al., Citation1998; Steger & Frazier, Citation2005). Van Cappellen et al. (Citation2014) included hope, satisfaction with life, perceived meaning in life, sense of self-worth, and optimism as positive indicators of association between religiosity and value outcomes. Easterlin (Citation1995, Citation2001) noted income was as an important factor in determining the level of happiness.

Discussion

The results of these studies show a positive correlation between happiness and religiosity. While the majority showed a significant relationship, others have shown weak yet positive relationships ( and ). None of the studies shows any cause and effect. Several meta-analyses have been conducted with studies exploring the association between religion, religiosity, happiness, subjective well-being, and mental health. For example, Abdel-Khalek (Citation2019) examined 26 studies from 13 Arab countries. He found 20 of the 26 studies (77%) showed statistically significant correlations between religiosity and happiness. Bergin (Citation1983) looked at 24 studies, with 30% showing no relationship, 47% a positive relationship, and 23% a negative relationship. Garssen et al. (Citation2020) looked at 48 longitudinal studies and found a small but positive (r = .08) impact of religion and religiosity on mental health. Koenig and Larson (Citation2001) had the largest number of studies (N = 850), in their meta-analysis. Studies included in Koenig et al. (Citation2001) indicated 79% showed positive associations between religion and life satisfaction. Two hundred and twenty-four studies conducted between the years of 1990 and 2010 were included in Koenig et al.’s (Citation2012) meta-analytic study and 78% showed a statistically significant relationship between religiosity and subjective well-being.

Some limitations of conducting research to explore the relationship between happiness, religiosity and life satisfaction, highlighted by the studies, include, despite having a large sample size, not having a representative sample, having a relatively small sample size and therefore concern over statistical power. Also, being underpowered with a smaller effect size, due to measurement complexity, they cannot be generalised. Additionally, a non-probability convenience sampling method being used and cross-sectional correlational studies, which cannot draw causal conclusions, as well as, gender invariance and limited age range. The use of self-report measures, which are not validated by any other form of assessment. Response bias due to self-report measures. Not having a “lie” scale. The use of measures designed and validated among English-speaking and Western countries, being used in other countries, where the main spoken language is not English. Limitations in the translations of such scales. The use of lengthy questionnaires, which could affect the response set. While participation in research is anonymous, responses may be affected for measures of religiosity, as religion is often not discussed openly or usually solicited. Additionally, there may be social desirability bias, irregular distribution amongst participating groups, and the use of only quantitative measures.

Nevertheless, particular strengths in the literature can also be found, such as the study by Suhail and Chaudhry (Citation2004). This was the largest survey conducted, exploring well-being among Pakistani participants from different socio-economic statuses in Lahore. Random sampling was done by Jesarati et al. (Citation2013), Parniyan et al. (Citation2016), and Fatima et al. (Citation2018). Abu-Raiya and Agbaria (Citation2016) urged researchers to explore the role positive religiosity plays in people’s lives, as it is an important dimension of life. In the age of Islamophobia, findings from Stuart and Ward (Citation2018), contributed to negotiating new sociocultural contexts, by providing more in-depth comprehension of the dynamic processes involved. Results found by Tekke et al. (Citation2018), are relevant in the development of empirical theology in the Islamic context.

Several implications of studying happiness and religiosity among the Muslim population have been highlighted by the studies. Some of these include the presentation of alternative measures of religiosity, contributing to fill the gap in measurement (Tiliouine & Belgoumidi, Citation2009). Taking religiosity into account in general mental well-being programs, as it predicts happiness (Sahraian et al., Citation2013), and the use of religious techniques to help improve the field of mental well-being (Hossain & Rizvi, Citation2017).

Future research needs to be conducted with diverse samples and use probability sampling from the general population, instead of student samples. It needs the use of Muslim samples from other countries, more significant sample numbers, different cultures as well as comparison across different religions and different age groups, different socio-economic statuses, and mediating psychosocial factors in the religiosity and subjective well-being link. It needs to explain how religiosity is experienced over the life span, qualitative designs, cross-sectional designs, and longitudinal studies. It needs the use of different scales for measurement and different measures to validate the results, physiological and behavioural measures based in laboratories, the use of more in-depth conceptual analysis, and the environmental influences on the mental health of Muslim populations.

Conclusions

To conclude, this systematic literature review has collated and explored two decades of research investigating religiosity and happiness within the global Muslim population. It is evident that overall, the current research is predominantly focused on Muslim students living in countries in which the prevailing faith is Islam. This literature review has found significant evidence to support a positive correlation between religiosity and subjective well-being. Future research should focus on Muslims living in countries, where they are a minority group as well as Muslims of different socio-economic backgrounds. This literature review has presented empirical evidence suggesting religion is an important dimension of life and therefore through understanding the role religion plays in well-being in countries where Muslims are in a minority, it could help to shape psychological support tools and interventions to better fit the needs of the resident Muslim population. This is especially important with the increasing focus on raising mental health awareness and the growing number of people accessing psychological support. Secondly, the search, screening, scoring, and analysis of this review were conducted solely by two of the authors and so bias in scoring and interpretation of the findings, cannot be ruled out. This review highlights the positive role religiosity can play in people’s lives and its associations with aspects of positive psychology, therefore, posing important implications for the holistic health and well-being of Muslims globally.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abdel-Khalek, A. M. (2006a). Happiness, health, and religiosity: Significant relations. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 9(1), 85–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/13694670500040625

- Abdel-Khalek, A. M. (2006b). Measuring happiness with a single-item scale. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 34(2), 139–150. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2006.34.2.139

- Abdel-Khalek, A. M. (2007). Religiosity, happiness, health, and psychopathology in a probability sample of Muslim adolescents. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 10(6), 571–583. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674670601034547

- Abdel-Khalek, A. M. (2009). Religiosity, subjective well-being, and depression in Saudi children and adolescents. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 12(8), 803–815. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674670903006755

- Abdel-Khalek, A. M. (2010a). Quality of life, subjective well-being, and religiosity in Muslim college students. Quality of Life Research, 19(8), 1133–1143. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-010-9676-7

- Abdel-Khalek, A. M. (2010b). Religiosity, subjective well-being, and neuroticism. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 13(1), 67–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674670903154167

- Abdel-Khalek, A. M. (2011a). Religiosity, subjective well-being, self-esteem, and anxiety among Kuwaiti Muslim adolescents. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 14(2), 129–140. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674670903456463

- Abdel-Khalek, A. M. (2011b). Subjective well-being and religiosity in Egyptian college students. Psychological Reports, 108(1), 54–58. https://doi.org/10.2466/07.17.PR0.108.1.54-58

- Abdel-Khalek, A. M. (2012a). Associations between religiosity, mental health, and subjective well-being among Arabic samples from Egypt and Kuwait. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 15(8), 741–758. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674676.2011.624502

- Abdel-Khalek, A. M. (2012b). Subjective well-being and religiosity: A cross-sectional study with adolescents, young and middle-age adults. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 15(1), 39–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674676.2010.551324

- Abdel-Khalek, A. M. (2013a). Religiosity, health and happiness: Significant relations in adolescents from Qatar. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 60(7), 656–661. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764013511792

- Abdel-Khalek, A. M. (2013b). The relationships between subjective well-being, health, and religiosity among young adults from Qatar. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 16(3), 306–318. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674676.2012.660624

- Abdel-Khalek, A. M. (2014a). Happiness, health, and religiosity: Significant associations among Lebanese adolescents. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 17(1), 30–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674676.2012.742047

- Abdel-Khalek, A. M. (2014b). Religiosity and well-being in a Muslim context. In C. Kim-Prieto (Ed.), Religion and spirituality across cultures, cross-cultural advancements in positive psychology (Vol. 9, pp. 71–85). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-8950-9_4

- Abdel-Khalek, A. M. (2015). Happiness, health, and religiosity among Lebanese young adults. Cogent Psychology, 2(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311908.2015.1035927

- Abdel-Khalek, A. M. (2017). Manual of the Arabic Scale of Happiness. Anglo-Egyptian Book Shop. (in Arabic).

- Abdel-Khalek, A. M. (2018). Religiosity and subjective well-being in the Arab context. Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Abdel-Khalek, A. M. (2019). Religiosity and well-being. In V. Zeigler-Hill & T. Shackelford (Eds.), Encyclopaedia of personality and individual differences (pp. 1–8). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-28099-8_2335-1

- Abdel-Khalek, A. M., & Eid, G. K. (2011). Religiosity and its association with subjective well-being and depression among Kuwaiti and Palestinian Muslim children and adolescents. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 14(2), 117–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674670903540951

- Abdel-Khalek, A. M., Korayem, A. S., & Lester, D. (2020). Religiosity as a predictor of mental health in Egyptian teenagers in preparatory and secondary school. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 67(3), 260–268. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764020945345

- Abdel-Khalek, A. M., & Lester, D. (2007). Religiosity, health, and psychopathology in two cultures: Kuwait and USA. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 10(5), 537–550. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674670601166505

- Abdel-Khalek, A. M., & Lester, D. (2009). A significant association between religiosity and happiness in a sample of Kuwaiti students. Psychological Reports, 105(2), 381–382. https://doi.org/10.2466/PR0.105.2.381-382

- Abdel-Khalek, A. M., & Lester, D. (2010a). Personal and psychological correlates of happiness among a sample of Kuwaiti Muslim students. Journal of Muslim Mental Health, 5(2), 194–209. https://doi.org/10.1080/15564908.2010.487725

- Abdel-Khalek, A. M., & Lester, D. (2010b). Constructions of religiosity, subjective well-being, anxiety, and depression in two cultures: Kuwait and USA. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 58(2), 138–145. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764010387545

- Abdel-Khalek, A. M., & Lester, D. (2013). Mental health, subjective well-being, and religiosity: Significant associations in Kuwait and USA. Journal of Muslim Mental Health, 7(2), 63–76. https://doi.org/10.3998/jmmh.10381607.0007.204

- Abdel-Khalek, A. M., & Lester, D. (2017). The association between religiosity, generalized self-efficacy, mental health, and happiness in Arab college students. Personality and Individual Differences, 109, 12–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.12.010

- Abdel-Khalek, A. M., & Lester, D. (2018). Subjective well-being and religiosity: Significant associations among college students from Egypt and the United Kingdom. International Journal of Culture & Mental Health, 11(3), 332–337. https://doi.org/10.1080/17542863.2017.1381132

- Abdel-Khalek, A. M., & Naceur, F. (2007). Religiosity and its association with positive and negative emotions among college students from Algeria. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 10(2), 159–170. https://doi.org/10.1080/13694670500497197

- Abdel-Khalek, A. M., & Singh, A. P. (2019). Love of life, happiness, and religiosity in Indian college students. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 22(8), 769–778. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674676.2019.1644303

- Abdel-Khalek, A. M., & Tekke, M. (2019). The association between religiosity, well-being, and mental health among college students from Malaysia. Revista Mexicana de Psicología, 36(1), 5–16. https://www.redalyc.org/journal/2430/243058940001/html/

- Abou El Azayem, G., & Hedayat-Diba, Z. (1994). The psychological aspects of Islam: Basic principles of Islam and their psychological corollary. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 4(1), 41–50. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327582ijpr0401_6

- Abu Rahim, M. A. R. (2013). The effect of life satisfaction and religiosity on happiness among post-graduates in Malaysia. IOSR Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 11(1), 34–38. https://doi.org/10.9790/0837-1113438

- Abu-Raiya, H., & Agbaria, Q. (2016). Religiousness and subjective well-being among Israeli-Palestinian college students: Direct or mediated links? Social Indicators Research, 126(2), 829–844. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-015-0913-x

- Achour, M., Grine, F., Mohd Nor, M. R., & MohdYusoff, M. Y. (2014). Measuring religiosity and its effects on personal well-being: A case study of Muslim female academicians in Malaysia. Journal of Religion and Health, 54(3), 984–997. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-014-9852-0

- Achour, M., Mohd Nor, M. R., Amel, B., Bin Seman, H. M., & MohdYusoff, M. Y. Z. (2017). Religious commitment and its relation to happiness among Muslim students: The educational level as moderator. Journal of Religion and Health, 56(5), 1870–1889. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-017-0361-9

- Aghababaei, N., Sohrabi, F., Eskandari, H., Borjali, A., Farrokhi, N., & Chen, Z. J. (2016). Predicting subjective well-being by religious and scientific attitudes with hope, purpose in life, and death anxiety as mediators. Personality and Individual Differences, 90, 93–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.10.046

- Allport, G. W., & Ross, J. M. (1967). Personal religious orientation and prejudice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 5(4), 432–443. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0021212

- Argyle, M. (1987). The psychology of happiness. Methuen.

- Argyle, M., Martin, M., & Crossland, J. (1989). Happiness as a function of personality and social encounters. In J. P. Forgas & J. M. Innes (Eds.), Recent advances in social psychology: An international perspective (pp. 189–203). Elsevier.

- Argyle, M., Martin, M., & Lu, L. (1995). Testing for stress and happiness: The role of social and cognitive factors. In C. D. Spielberger & I. G. Sarason (Eds.), Stress and emotion (Vol. 15, pp. 173–187). Taylor & Francis.

- Ashkanani, H. R. (2009). The relationship between religiosity and subjective well-being: A case of Kuwaiti car accident victims. Traumatology, 15(1), 23–28. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534765608323500

- Baroun, K. A. (2006). Relations among religiosity, health, happiness, and anxiety for Kuwaiti adolescents. Psychological Reports, 99(3), 717–722. https://doi.org/10.2466/PR0.99.3.717-722

- Bayani, A. A. (2014). The relationship between religiosity and happiness among students in an Iranian university. Pertanika Journal of Social Science and Humanities, 22(3), 709–716. http://www.pertanika.upm.edu.my/resources/files/Pertanika%20PAPERS/JSSH%20Vol.%2022%20(3)%20Sep.%202014/01%20Page%20695-708%20(JSSH%200866-2013%20Review%20Article).pdf

- Bergin, A. E. (1983). Religiosity and mental health: A critical re-evaluation and meta-analysis. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 14(2), 170–184. https://doi.org/10.1037/0735-7028.14.2.170

- Bergin, A. E., Masters, K. S., & Richards, P. S. (1987). Religiousness and mental health reconsidered: A study of an intrinsically religious sample. Journal of Counselling Psychology, 34(2), 197–204. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.34.2.197

- Bradburn, N. M. (1969). The structure of psychological well-being. Aldine Publishing Company.

- Compton, W. C. (2005). An introduction to positive psychology. Wadsworth.

- Cummins, R. A. (1995). On the trail of the gold standard for subjective well-being. Social Indicators Research, 35(2), 179–200. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf01079026

- Devine, J., Hinks, T., & Naveed, A. (2019). Happiness in Bangladesh: The role of religion and connectedness. Journal of Happiness Studies, 20(2), 351–371. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-017-9939-x

- Diener, E. (1998). Subjective well- being and personality. In D. F. Barone, M. Hersen, & V. B. Van Hasselt (Eds.), Advanced personality (pp. 311–334). Plenum. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-8580-4_13

- Diener, E., Lucas, R. E., & Oishi, S. (2002). Subjective well- being: The science of happiness and life satisfaction. In C. R. Snyder & S. J. Lopez (Eds.), Handbook of positive psychology (pp. 463–473). Oxford University Press.

- Diener, E., Scollon, C. N., & Lucas, R. E. (2003). The evolving concept of subjective well-being: The multifaceted nature of happiness. Advances in Cell Aging and Gerontology, 15, 187–219. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1566-3124(03)15007-9

- Diener, E., Tay, L., & Myers, D. G. (2011). The religion paradox: If religion makes people happy, why are so many dropping out? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101(6), 1278–1290. https://doi org/10.1037/a0024402

- Donahue, M., & Benson, P. (1995). Religion and the well-being of adolescents. The Journal of Social Issues, 51(2), 145–160. https://doi.org/10.1111/j1540-45601995tb01328x

- Easterlin, R. A. (1995). Will raising the incomes of all increase the happiness of all? Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 27(1), 35–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/0167-2681(95)00003-b

- Easterlin, R. A. (2001). Income and happiness: Towards a unified theory. The Economic Journal, 111(473), 465–484. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0297.00646

- Ellison, C. G., Gay, D. A., & Glass, T. A. (1989). Does religious commitment contribute to individual life satisfaction? Social Forces, 68(1), 100–123. https://doi.org/10.2307/2579222

- Ellor, J. W., & McGregor, J. A. (2011). Reflections on the words “religion,” “spiritual well-being,” and “spirituality”. Journal of Religion, Spirituality & Aging, 23(4), 275–278. https://doi.org/10.1080/15528030.2011.603074

- Fatima, S., Sharif, S., & Khalid, I. (2018). How does religiosity enhance psychological well-being? Roles of self-efficacy and perceived social support. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 10(2), 119–127. https://doi.org/10.1037/rel0000168

- Francis, L. J., Ok, Ü, & Robbins, M. (2016). Religion and happiness: A study among university students in Turkey. Journal of Religion and Health, 56(4), 1335–1347. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-016-0189-8

- Garssen, B., Visser, A., & Pool, G. (2020). Does spirituality or religion positively affect mental health? Meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 31(1), 4–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508619.2020.1729570

- Gillings, V., & Joseph, S. (1996). Religiosity and social desirability: Impression management and self-deceptive positivity. Personality and Individual Differences, 21(6), 1047–1050. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0191-8869(96)00137-7

- Glock, C. Y., & Stark, R. (1965). Religion and society in tension. Rand McNally.

- Gulamhussein, Q. U. A., & Eaton, N. R. (2015). Hijab, religiosity, and psychological wellbeing of Muslim women in the United States. Journal of Muslim Mental Health, 9(2), 25–40. https://doi.org/10.3998/jmmh.10381607.0009.202

- Hackman, J. R., & Oldham, G. R. (1975). Development of the diagnostic survey. Journal of Applied Psychology, 60, 159–170. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0076546

- Hashemi, N., Marzban, M., Sebar, B., & Harris, N. (2020). Religious identity and psychological well-being among middle-eastern migrants in Australia: The mediating role of perceived social support, social connectedness, and perceived discrimination. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 12(4), 475–486. https://doi.org/10.1037/rel0000287

- Hill, P. C. (2013). Measurement assessment and issues in the psychology of religion and spirituality. In R. F. Paloutzian & C. L. Park (Eds.), Handbook of the psychology of religion and spirituality (pp. 48–74). Guilford.

- Hills, P., & Argyle, M. (2001). Emotional stability as a major dimension of happiness. Personality and Individual Differences, 31(8), 1357–1364. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0191-8869(00)00229-4

- Hood, R. W., Hill, P. C., & Spilka, B. (2018). The psychology of religion: An empirical approach (5th ed.). Guilford Press.

- Hossain, M. Z., & Rizvi, M. A. K. (2017). Relationship between religious belief and happiness in Oman: A statistical analysis. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 19(7), 781–790. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674676.2017.1280009

- Husain, S. A. (1998). Religion and mental health from the Muslim perspective. In H. G. Koenig (Ed.), Handbook of religion and mental health (pp. 279–290). Academic.

- Jesarati, A., Hemmati, A., Mohammadi, I., Jesarati, A., & Moshiri, R. (2013). The relationship between religious attitude, social relationship with happiness of college students. International Research Journal of Applied and Basic Sciences, 6(10), 1451–1457. https://irjabs.com/files_site/paperlist/r_1843_131025151039.pdf

- Khenfer, J., & Roux, E. (2012). How does religion matter in the marketplace for minority settings? The case of Muslim consumers in France. EMAC 42nd Conference, Lisbonne, Portugal (pp. 1–7). https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00743900

- Kmet, L. M., Lee, R. C., & Cook, L. S. (2004). Standard quality assessment criteria for evaluating primary research papers from a variety of fields. Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research.

- Koenig, H. G., King, D. E., & Carson, V. B. (2012). Handbook of religion and health (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Koenig, H. G., & Larson, D. B. (2001). Religion and mental health: Evidence for an association. International Review of Psychiatry, 13(2), 67–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540260124661

- Koenig, H. G., McCullough, M. E., & Larson, D. B. (2001). Handbook of religion and health. Oxford University Press.

- Loewenthal, K. M., & Cinnirella, M. (1999). Beliefs about the efficacy of religious, medical and psychotherapeutic interventions for depression and schizophrenia among women from different cultural–religious groups in Great Britain. Transcultural Psychiatry, 36(4), 491–504. https://doi.org/10.1177/136346159903600408

- McClure, R., & Loden, M. (1982). Religious activity, denomination membership and life satisfaction. Psychology: A Quarterly Journal of Human Behavior, 9(4), 12–17.

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., & Group, T. P. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed1000097

- Momtaz, Y. A., Hamid, T., Ibrahim, R., Yahaya, N., & Tyng Chai, S. (2011). Moderating effect of religiosity on the relationship between social isolation and psychological well-being. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 14(2), 141–156. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674676.2010.497963

- Mookerjee, R., & Beron, K. (2005). Gender, religion and happiness. The Journal of Socio-Economics, 34(5), 674–685. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socec.2005.07.012

- Pargament, K. I. (1997). The psychology of religion and coping: Theory, research, and practice. Guilford.

- Pargament, K. I., Smith, B. W., Koenig, H. G., & Perez, L. M. (1998). Patterns of positive and negative religious coping with major life stressors. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 37(4), 710–724. https://doi.org/10.2307/1388152

- Parniyan, R., Kazemiane, A., Jahromi, M. K., & Poorgholami, F. (2016). A study of the correlation between religious attitudes and quality of life in students at Jahrom University of Medical Sciences in 2014. Global Journal of Health Science, 8(10), 43–49. https://doi.org/10.5539/gjhs.v8n10p43

- Quraishi, M. T. (1984). Islam: A way of life and a movement. American Trust Publications.

- Rizvi, M. A., & Hossain, M. Z. (2016). Relationship between religious belief and happiness: A systematic literature review. Journal of Religion and Health, 56(5), 1561–1582. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-016-0332-6

- Robbins, M., & Francis, L. J. (1996). Are religious people happier? A study among undergraduates. In L. J. Francis, W. K. Kay, & W. S. Campbell (Eds.), Research in religious education (pp. 207–217). Gracewing.

- Sahraian, A., Gholami, A., Javadpour, A., & Omidvar, B. (2013). Association between religiosity and happiness among a group of Muslim undergraduate students. Journal of Religion and Health, 52(2), 450–453. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-011-9484-6

- Saleem, T., Saleem, S., Mushtaq, R., & Gul, S. (2020). Belief salience, religious activities, frequency of prayer offering, religious offering preference and mental health: A study of religiosity among Muslim students. Journal of Religion and Health, 60(2), 726–735. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-020-01046-z

- Seligman, M. E. (2002). Authentic happiness: Using the new positive psychology to realize your potential for lasting fulfillment. Free Press.

- Shaver, Y. P., Lenauer, M. A., & Sadd, S. (1980). Religiousness, conversion and subjective well-being: The healthy-minded religion of modern American women. American Journal of Psychiatry, 137(12), 1563–1568. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.137.12.1563

- Stavrova, O., Fetchenhauer, D., & Schlösser, T. (2013). Why are religious people happy? The effect of the social norm of religiosity across countries. Social Science Research, 42(1), 90–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2012.07.002

- Steger, M. F., & Frazier, P. (2005). Meaning in life: One link in the chain from religiousness to well-being. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52(4), 574–582. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167524574

- Stuart, J., & Ward, C. (2018). The relationships between religiosity, stress, and mental health for Muslim immigrant youth. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 21(3), 246–261. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674676.2018.1462781

- Suhail, K., & Chaudhry, H. R. (2004). Predictors of subjective well-being in an Eastern Muslim culture. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 23(3), 359–376. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.23.3.359.35451

- Tay, L., Li, M., Myers, D., & Diener, E. (2014). Religiosity and subjective well-being: An international perspective. In C. Kim-Prieto (Ed.), Religion and spirituality across cultures (pp. 163–175). Springer Science + Business Media. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-8950-9_9

- Tekke, M., Francis, L. J., & Robbins, M. (2018). Religious affect and personal happiness: A replication among Sunni students in Malaysia. Journal of Muslim Mental Health, 11(2), 3–15. https://doi.org/10.3998/jmmh.10381607.0011.201

- Thorson, J. A., Powell, F. C., Abdel-Khalek, A. M., & Beshai, J. A. (1997). Constructions of religiosity and death anxiety in two cultures: The United States and Kuwait. Journal of Psychology and Theology, 25(3), 374–383. https://doi.org/10.1177/009164719702500306

- Tiliouine, H., & Belgoumidi, A. (2009). An exploratory study of religiosity, meaning in life and subjective wellbeing in Muslim students from Algeria. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 4(1), 109–127. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-009-9076-8

- Tiliouine, H., Cummins, R., & Davern, M. (2009). Islamic religiosity, subjective well-being, and health. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 12(1), 55–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674670802118099

- Van Cappellen, P., Toth-Gauthier, M., Saroglou, V., & Fredrickson, B. L. (2014). Religion and well-being: The mediating role of positive emotions. Journal of Happiness Studies, 17(2), 485–505. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-014-9605-5

- Veenhoven, R. (2010). Greater happiness for a greater number: Is that possible and desirable? Journal of Happiness Studies, 11(5), 605–629. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-010-9204-z

- Veenhoven, R. (2011). Greater happiness for a greater number: Is that possible? If so how? In K. Sheldon, T. Kashdan, & M. Steger (Eds.), Designing positive psychology: Taking stock and moving forward (pp. 396–409). Oxford University Press.

- Vishkin, A., Bigman, Y., & Tamir, M. (2014). Religion, emotion regulation, and well-being. In C. Kim-Prieto (Ed.), Religion and spirituality across cultures. Cross-cultural advancements in positive psychology (Vol. 9, pp. 247–269). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-8950-9_13.

- Wills, E. (2009). Spirituality and subjective well-being: Evidence for a new domain in the personal well-being index. Journal of Happiness Studies, 10(1), 49–69. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-007-9061-6

- World Health Organization. (2001). The world health report 2001. Mental health: New understanding, new hope. Retrieved from: https://www.who.int/whr/2001/en

- Ziapour, A., Khatony, A., Jafari, F., & Kianipour, N. (2018). Correlation of personality traits with happiness among university students. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research, 42(2), 172–177. https://doi.org/10.7860/jcdr/2018/31260.11450

- Zuckerman, D. M., Kasl, S., & Ostfeld, A. M. (1984). Psychosocial predictors of mortality among the elderly poor: The role of religion, well-being and social contacts. American Journal of Epidemiology, 119(3), 410–423. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113759

- Zullig, K. J., Ward, R. M., & Horn, T. (2006). The association between perceived spirituality, religiosity, and life satisfaction: The mediating role of self-rated health. Social Indicators Research, 79(2), 255–274. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-005-4127-5