Abstract

Purpose: Study of validity of the Medication Adherence Self-Report Inventory (MASRI) for use in clinical practice to treat patients with benign prostatic obstruction (BPO) accompanied with overactive bladder (OAB) symptoms.

Methods: During 12 weeks of the randomized study, 452 patients with BPO and OAB symptoms (mean age of 61.3 (12.7)) were studied for adherence to the treatment with Tamsulosin, Solifenacin and Trospium using the MASRI. External monitoring instruments included the Brief Medication Questionnaire (BMQ) and the visual remaining pill count. The state of the prostate gland and the lower urinary tract was monitored using questionnaires I-PSS, OAB Awareness Tool, uroflowmetry and voiding diaries.

Result: Correlation between the percentage of men non-adherent to treatment (MASRI) and the percentage of patients having a belief barrier on the screen of the BMQ was r = 0.89, p ≤0.05, r = 0.92, p ≤0.01, r = 0.85, p ≤0.05, a number of missed doses on the Regimen Screen of the BMQ was r = 0.79; p ≤0.05; r = 0.81; p ≤0.05; r = 0.75, p ≤0.05, a number of non-adherent patients according to the BMQ was r = 0.83 (p ≤0.05), r = 0.88 (p ≤0.05), r = 0.79, p ≤0.05, the results of the pill count were r = 0.65–0.76; p ≤0.05-0.01. These data confirm high validity of the MASRI.

Conclusion: The MASRI is a valid tool for rapid assessment of adherence to treatment of patients with BPO and OAB receiving Tamsulosin and antimuscarinic drugs and may be recommended for use in clinical practice.

Introduction

Prevalence of prostatic hyperplasia is not less than 10.3%, it increases with age and reaches the highest values at the age of 80–85 (up to 24%) [Citation1]. The possibility of developing prostatic hyperplasia obstruction for a 46-year-old man is at least 45% within the next 30 years of life. Symptoms, typical of benign prostatic obstruction (BPO), normally affect adversely the health-related quality of life [Citation2,Citation3]. In addition to the risk of malignant transformation, BPO disturbs the functional state of the lower urinary tract (LUT), contributes to the development of overactive bladder (OAB) symptoms [Citation4–6].

BPO adversely affects the erectile function, which may lead to depression and often make the elderly patient feel psychologically uncomfortable [Citation7]. The development of BPO is caused by three reasons. This is a chronic bacterial or viral infection [Citation8]. This is metabolic syndrome [Citation9], hypercholesterolemia, in particular. Finally, one of the important mechanisms of BPO development is hormonal diseases (hypogonadism and/or hyperestrogenism) [Citation10]. Such conditions often require testosterone replacement therapy [Citation11,Citation12].

The efficacy of alpha blockers in the treatment of BPO accompanied by pathological LUT symptoms is deemed to be established [Citation13,Citation14]. Recently, there were the results of studies obtained confirming the efficacy of combined therapy (alpha-blocker + antimuscarinics) in the presence of overactivity symptoms in individuals suffering from BPO [Citation15].

Meanwhile, many modern researchers believe that the majority of patients with BPO develop detrusor overactivity. [Citation15–18]. The Sixth International Consultation on New Developments in Prostate Cancer and Prostate Diseases recommended long-term administration of α1-blocker and antimuscarinic (AM) drugs in treatment of BPO with OAB symptoms. However, following the therapeutic protocol does not always provide the desired effect. In earlier studies [Citation19–21], confirming the data of other authors [Citation22], we noticed some difference between the results of randomized controlled clinical trials and the results obtained in routine clinical practice. This may be due to, in particular, patients’ poor adherence to drug therapy [Citation23,Citation24]. However, the tools for assessing treatment adherence in patients with OAB and BPO currently available are not optimal [Citation25].

The standard for the assessment of adherence to physician’s prescriptions are electronic devices that record the number of pills used, pharmacy records, the pill count and interviewer questionnaires. However, researchers using electronic devices in clinical practice often note their high labor input, inconvenience, substantial cost and the possibility of the inaccurate count (a cap opened does not always mean a pill taken). The interviewer questionnaires used in clinical practice have high construct validity, however, they require involvement of an interviewer and take time for processing of the data obtained [Citation26].

Recently, the Medication Adherence Self-Report Inventory (MASRI) Questionnaire was proposed to use for assessing treatment adherence and difficulties in adhering to physician’s orders. Validity of tools for self-assessment of adherence is sometimes questioned. However, data on high correlation of the MASRI with standard monitoring tools is provided more often [Citation27]. High construct and concurrent MASRI validity is demonstrated in assessing adherence to treatment with Fesoterodine in women with OAB [Citation28]. The majority of studies emphasize the ease of use of the MASRI, including that by individuals with cognitive impairment, as well as cost reduction related to diagnosis of adherence.

Given the demand of practicing urologists for a tool for self-assessment of adherence to treatment in patients with OAB and BPO that can be interpreted easily, requires low labor input, is low-cost and accurate, as well as considering the results of earlier studies, we have attempted to study MASRI validity in these patients.

Methods

A randomized study of MASRI validity was conducted at City Polyclinic No. 3 of Vladivostok and the Far Eastern Federal University from 1 September 2014 until 15 December 2014 with the participation of 452 male patients older than 50 years (mean age 61.3 (12.7)). A group included individuals with the diagnosis of BPO (8–19 points on the I-PSS scale, the mean score of 14.1 (3.7)), with OAB symptoms (more than 8 points on the scale of OAB Awareness Tool, the mean score of 16.8 (5.2)) [Citation29], having not taken α1-blockers and antimuscarinic drugs earlier. The exclusion criteria were active or chronic urinary tract infections, acute urinary retention, shortening of the QT interval and terminal cancer.

Patients were randomly allocated into the following groups. In the first group (158 patients, mean age of 57.9 (9.4) years) patients were prescribed with Tamsulosin – 0.4 mg daily. In the second group (145 individuals, 63.4 (7.1) years), patients were prescribed with Tamsulosin – 0.4 mg [Citation20] and Solifenacin – 5–15 mg daily. Given, the positive result obtained earlier in prescribing a α1-blocker and a combination of AMs [Citation12,Citation29], we also formed a third group (149 individuals, 64.1 (7.8) years) patients were prescribed Tamsulosin – 0.4 mg, Solifenacin – 5–15 mg and Trospium – 5 mg daily.

The study protocol included four visits – a starting one treatment was prescribed, as well as at the 4, 8 and 12 weeks, during which level of adherence to drug administration was monitored. Monitoring was carried out using the MASRI. The Brief Medication Questionnaire (BMQ) and the visual pill count were used as the external standard tools [Citation28]. The functional state of the LUT was monitored using uroflowmetry (conducted during each visit) and voiding diaries (evaluated at the end of the study) [Citation30]. The indicators of the state of the LUT were frequency of urination, urgency urge, incontinence, average urine flow rate (Qaver, ml/s), bladder volume, ml. [Citation31] Individuals adhering to less than 80% of prescriptions for drug administration were considered poorly adherent to treatment [Citation32].

The MASRI is a questionnaire for self-assessment of treatment adherence and contains a visual analog scale (VAS) for determining adherence level in the range from 0 to 100%. The MASRI includes also two auxiliary scales with questions that help patients to assess their treatment adherence better. The BMQ is a tool for assessing treatment adherence and difficulties with drug administration. The BMQ is completed by an interviewer while visiting patients in the clinic. The BMQ contains three scales – Regimen, Belief and Recall, and has satisfactory specificity, positive predictive value and overall accuracy [Citation26].

We controlled construct validity by determining a connection between non-adherence to a regime according to the MASRI and presence of a belief barrier on the Belief screen of the BMQ. We suggested that men non-adherent to treatment according to the MASRI will be more likely to have a belief barrier, than patients adherent to treatment.

Criterion concurrent validity was assessed by comparing the percentage of missed doses on an adherence scale of the MASRI, the BMQ and the visual pill count. Correlation was calculated using the Spearman correlation coefficient. Discriminant validity was determined by comparing patients adherent and non-adherent to treatment according to the MASRI, the BMQ and the visual pill count using the chi-square test.

Correlation of MASRI data on adherence and the objective state of the LUT was studied by regression model building. Analyzing feature survival (adherence) the two-parameter Weibull distribution was used with maximum-likelihood estimation by standard iterative methods of function minimization and multiple right type 1 censoring.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis was used to “cut off” invalid data in the optimum way (an external standard is BMQ data). Specificity, sensitivity and the likelihood ratios of the MASRI were found using 95% confidence intervals (CI) for each ratio.

In summing and analyzing all continuous variables, median and interquartile ranges were used. Description of categorical variables was performed using absolute and relative feature frequency. Differences were considered significant at p < 0.05, all p values are two-sided. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 8.0.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

The Ethics Commission of the Far Eastern Federal University found the study protocol ethically acceptable. The study was conducted following the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

439 individuals from 452 patients, who participated in the study, stayed within the follow-up field at the end of the 12 week, which was 97.1%. At the 4, 8 and 12-week follow-up 84%, 86% and 92% of men, respectively, having a belief barrier according to the BMQ data were found among patients non-adherent to treatment according to the MASRI (). The difference in this indicator between the percentage of patients among individuals adherent and non-adherent to treatment according to the MASRI was p ≤ 0.01 throughout the follow-up period. Correlation between the percentage of men having a belief barrier and the percentage of men non-adherent to treatment (MASRI) was r = 0.89 (p ≤ 0.05), r = 0.92 (p ≤ 0.01), r = 0.85 (p ≤ 0.05). These data confirm construct validity of the MASRI.

Table 1. Belief barriers and non-adherent (BMQ) in adherent and non-adherent patients (MASRI).

The tool studied allowed to identify correctly the absence of adherence in 94–98% of patients compared to BMQ data (r = 0.83 (p ≤ 0.05), r = 0.88 (p ≤ 0.05), r = 0.79 (p ≤ 0.05)), and the results of the pill count (r = 0.65–0.76; p ≤ 0.05–0.01), which argued for its discriminant validity ().

Comparison of the number of missed doses on the Regimen screen of the BMQ with the percentage of days, when drugs were not taken for any reason, as well as with the results of the pill count, suggested concurrent validity of the MASRI. Correlation between the two first indicators during the 12-week follow-up was r = 0.79; p ≤ 0.05; r = 0.81; p ≤ 0.05; r = 0.75; p ≤ 0.05.

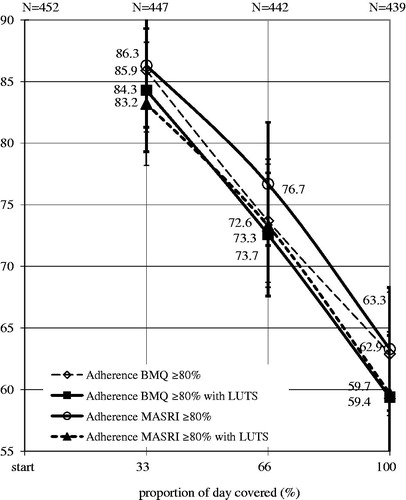

Indicators of the LUT function in adherent and non-adherent patients according to the MASRI differed significantly at the 8 and 12-week follow-up. Correlation between the change in these percentage of men with LUTS adherent to treatment with AMs, according to the MASRI and the BMQ was very high (at the 4, 8 and 12 week r = 0.91, p ≤ 0.01; r = 0.96, p ≤ 0.05; r = 0.91, p ≤ 0.01, respectively, ).

Figure 1. Changes in the percentage of patients LUTS who were identified of MASRY and BMQ as treatment adherence. LUTS: lower urinary tract symptoms, MASRI: questionnaire The Medication Adherence Self-Report Inventory, BMQ: Brief Medication Questionnaire.

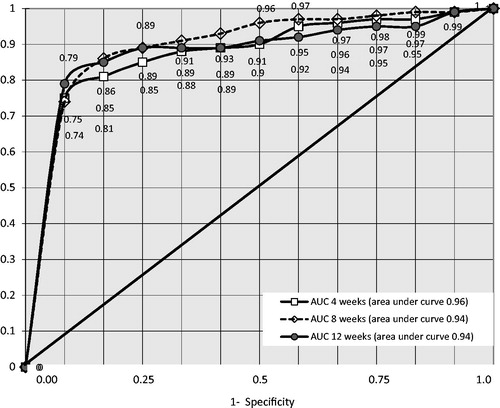

The hypothesis of insufficient/excess discriminant MASRI power was refuted by ROC – analysis (). The area under the curve (AUC) reflected the acceptable values of the variables tending to 1. The AUC proved to be 0.96 ± 0.03 after 4 weeks, 0.94 ± 0.06 after 8 and 0.94 ± 0.05 after 12 weeks after the start of the study. 95% confidence intervals were taken for calculations.

Figure 2. ROC – curve of the MASRI as compared to the BMQ at 4, 8 and 12weeks (n = 629). AUC: area under curve, MASRI: Medication Adherence Self-Report Inventory, BMQ: Brief Medication Questionnaire.

The optimum sensitivity–specificity ratio was determined using the 90% cutoff barrier false positives 87%, 90% at the 4 week of the experiment, 89%, 95% at the 8 week, and 90%, 91% at 12 weeks, respectively (). However, at the 80% cutoff of MASRI adherence method sensitivity was 87–91% and specificity remained at acceptable level. The positive-likelihood ratio was calculated for studying the possibility of result extrapolation to the population. Using the 80% cutoff barrier, this indicator was 7.1, 7.9 and 6.9, at the 4, 8 and 12 week, respectively. These values are lower than at the 90% cutoff, but acceptable for predicting prescription adherence.

Table 2. Significance of different cut points on the MASRI at 4, 8 and weeks study adherence of AM (n = 452).

Comparing data on tool validity in men from different groups (receiving only Tamsulosin, Tamsulosin and Solifenacin, Trospium and Tamsulosin), we found that the differences in the results obtained do not exceed the statistical error.

Ten men from 13 patients not included in the final report, refused to participate in the study without giving a reason, three other refused due to acute infectious diseases. No cases of acute urinary retention were observed in patients receiving two AM drugs. All socio-demographic characteristics of the group at the start and finish of the examination were statistically homogeneous.

Discussion

Comparing the results of study of adherence in men receiving drugs regarding BPO accompanied by OAB symptoms according to MASRI with the results obtained using the BMQ and the visual pill count, a high level of correlation was found. These MASRI adherence scales are closely linked with the Belief Screen of the BMQ (r = 0.85–0.92, p ≤ 0.05–0.01), the Adherence Screen of the BMQ (r = 0.75–0.81, p ≤ 0.05–0.01), the Recall screen of the BMQ (r = 0.79–83, p ≤ 0.05), and the results of the pill count (r = 0.65–0.76; p ≤ 0.05–0.01), which confirms the high construct, concurrent and discriminant tool validity. These data are similar to the results of study of tool validity in women with OAB receiving the flexible-dose fesoterodine therapy [Citation28], and suggest that using the tool in clinical practice may be appropriate.

The purpose of this study was not studying the functional state of the LUT on the background of therapy administered (we studied the change in LUT parameters at BPO earlier [Citation20,Citation21]). Nevertheless, we found it necessary to include monitoring of urodynamic parameters in the design, as such studies have not been conducted earlier, and the functional state of the LUT could be an important indirect criterion of patients’ adherence to treatment. The percentage of patients with LUTS, adherent to treatment according to the MASRI and the BMQ was statistically homogeneous, which, in our opinion, could serve as a further confirmation of the MASRI acceptability as an indicator of men’s adherence to treatment.

ROC-analysis confirmed invalidity of the null hypothesis about excess tool discriminant power that is not in conflict with data of other researchers [Citation28,Citation33]. At the 90% cutoff of data tool sensitivity and specificity levels proved to be quite acceptable with the relatively high positive-likelihood ratio (9.1–15.7). The optimum cutoff for assessing adherence, at least for AMs, is considered 80%. Sometimes even adherence score ≥ 80% is questioned as the optimum for treatment of OAB and BPO [Citation34]. However, according to most researchers, this cutoff is the optimum for assessing adherence and predicting effectiveness of treatment of LUTS (both related and not related to BPO) [Citation25,Citation32,Citation33]. Analysis of data for MASRI showed that at the 80% cutoff sensitivity (0.87–0.91) and specificity (0.81–0.85) levels are quite high, and positive likelihood ratio indicators (6.39–8.29) allow to extrapolate the results to the population.

The important result of this study, in our opinion, is that the MASRI is a tool that is not only effective and valid for rapid assessment of adherence to treatment, but also much more available in clinical practice than the standard assessment tools. Electronic and visual pill counts, as well as the BMQ and other questionnaires optimum for use in randomized clinical trials are often unreasonably time-consuming and expensive for clinical application. Their use is quite appropriate in in-depth clinical trials. At the same time the MASRI, data of which are perfectly valid already at the 4 week, it could serve as an alternative for rapid and qualitative assessment of adherence in men taking Tamsulosin and AMs for predicting and correcting treatment.

The MASRI investigations and assessments performed, of course, need to be further clarified. Further MASRI investigations would be appropriate, in our opinion, for studying efficacy of this tool for the evaluation of clinical outcomes in patients with OAB and BPO receiving long-term therapy, more than 6 months, as well as with polypharmacy.

Conclusions

MASRI is an effective tool for the assessment of adherence to treatment of patients with BPO and OAB receiving Tamsulosin and antimuscarinic drugs. Due to its simplicity and availability, as well as the minimum cost, the MASRI can be used in clinical practice as a rapid method for current assessment of adherence to the treatment during each patient’s visit.

Declaration of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Verhamme KM, Dieleman JP, Bleumink GS, et al. Incidence and prevalence of lower urinary tract symptoms suggestive of benign prostatic hyperplasia in primary care-the Triumph project. Eur Urol 2002;42:323–8.

- Castro-Díaz D, Callejo D, Cortés X. Study of Quality of life in Patients with Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia under Treatment with Silodosin. Actas Urol Esp 2014;38:361–6.

- Cam K, Muezzinoglu T, Aydemir O, et al. Development of a quality of life scale specific for patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia. Int Urol Nephrol 2013;45:339–46.

- Spångberg A, Dahlgren H. Benign prostatic hyperplasia with bladder outflow obstruction. A systematic review. Lakartidningen 2013;110:682–5.

- Liao L, Schaefer W. Qualitative quality control during urodynamic studies with TSPs for cystometry in men with lower urinary tract symptoms suggestive of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Int Urol Nephrol 2014;46:1073–9.

- Efesoy O, Apa D, Tek M, Çayan S. The effect of testosterone treatment on prostate histology and apoptosis in men with late-onset hypogonadism. Aging Male 2016;19:79–84.

- Demir O, Akgul K, Akar Z, et al. Association between severity of lower urinary tract symptoms, erectile dysfunction and metabolic syndrome. Aging Male 2009;12:29–34.

- Auffenberg GB, Helfand BT, McVary KT. Established medical therapy for benign prostatic hyperplasia. Urol Clin North Am 2009;36:443–59.

- Yeh HC, Liu CC, Lee YC, et al. Associations of the lower urinary tract symptoms with the lifestyle, prostate volume, and metabolic syndrome in the elderly males. Aging Male 2012;15:166–72.

- Yassin A, Nettleship JE, Talib R, et al. Effects of testosterone replacement therapy withdrawal and re-treatment in hypogonadal elderly men upon obesity, voiding function and prostate safety parameters. Aging Male 2016;19:64–9.

- Meuleman EJ, Legros JJ, Bouloux PM, Study 43203 Investigators, et al. Effects of long-term oral testosterone undecanoate therapy on urinary symptoms: data from a 1-year, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging trial in aging men with symptomatic hypogonadism. Aging Male 2015;18:157–63.

- Yassin AA, El-Sakka AI, Saad F, Gooren LJ. Lower urinary-tract symptoms and testosterone in elderly men. World J Urol 2008;26:359–64.

- Lin KH, Lin YW, Wen YC, Lee LM. Efficacy and safety of orally disintegrating tamsulosin tablets in Taiwanese patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia. Aging Male 2012;15:246–52.

- Salah Azab S, Elsheikh MG. The impact of the bladder wall thickness on the outcome of the medical treatment using alpha-blocker of BPH patients with LUTS. Aging Male 2015;18:89–92.

- Hanuš T, Zámečník L, Doležal T, et al. Occurrence of overactive bladder in patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia in the Czech Republic. Urol Int 2011;86:407–13.

- Bosch JL, Bangma CH, Groeneveld FP, Bohnen AM. The long-term relationship between a real change in prostate volume and a significant change in lower urinary tract symptom severity in population-based men: the Krimpen study. Eur Urol 2008;53:819–25.

- Shahab N, Seki N, Takahashi R, et al. The profiles and patterns of detrusor overactivity and their association with overactive bladder symptoms in men with benign prostatic enlargement associated with detrusor overactivity. Neurourol Urodyn 2009;28:953–8.

- Wada N, Hashizume K, Matsumoto S, Kakizaki H. Dutasteride improves bone mineral density in male patients with lower urinary tract symptoms and prostatic enlargement: a preliminary study. Aging Male 2015;30:1–3.

- Kosilov K, Loparev S, Ivanovskaya M, Kosilova L. Randomized controlled trial of cyclic and continuous therapy with trospium and solifenacin combination for severe overactive bladder in elderly patients with regard to patient compliance. Ther Adv Urol 2014;6:215–23.

- Kosilov KV, Loparev SA, Ivanovskaya MA, Kosilova LV. effectiveness of solifenacin and trospium for managing of severe symptoms of overactive bladder in patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia. Am J Men′S Health 2016;10:157–63.

- Kosilov KV, Loparev SA, Ivanovskaya MA, Kosilova LV. A randomized, controlled trial of effectiveness and safety of management of OAB symptoms in elderly men and women with standard-dosed combination of solifenacin and mirabegron. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2015;61:212–16.

- Gopal M, Haynes K, Bellamy SL, Arya LA. Discontinuation rates of anticholinergic medications used for the treatment of lower urinary tract symptoms. Obstet Gynecol 2008;112:1311–18.

- Nichol MB, Knight TK, Wu J, et al. Evaluating use patterns of and adherence to medications for benign prostatic hyperplasia. J Urol 2009;181:2214.

- Barkin J. Review of dutasteride/tamsulosin fixed-dose combination for the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia: efficacy, safety, and patient acceptability. Patient Prefer Adherence 2011;5:483–90.

- Ogata I, Yamasaki K, Tsuruda A, et al. Some problems for dosage form based on questionnaire surveying compliance in patients taking tamsulosin hydrochloride. Yakugaku Zasshi 2008;128:291–7.

- Svarstad BL, Chewning BA, Sleath BL, Claesson C. The Brief Medication Questionnaire: a tool for screening patient adherence and barriers to adherence. Patient Educ Couns 1999;37:113–24.

- Morisky DE, Green LW, Levine DM. Concurrent and predictive validity of a self-reported measure of medication adherence. Medical Care 1986;24:67–74.

- Andy UU, Harvie HS, Smith AL, et al. Validation of a self-administered instrument to measure adherence to anticholinergic drugs in women with overactive bladder. Neurourol Urodyn 2015;34:424–8.

- Coyne KS, Zyczynski T, Margolis MK, et al. Validation of an overactive bladder awareness tool for use in primary care settings. Adv Ther 2005;22:381–94.

- Kosilov KV, Loparev SA, Ivanovskaya MA, Kosilova LV. Additional correction of OAB symptoms by two anti-muscarinics for men over 50 years old with residual symptoms of moderate prostatic obstruction after treatment with Tamsulosin. Aging Male 2015;18:44–8.

- Amundsen CL, Parsons M, Cardozo L, et al. Bladder diary volume per void measurements in detrusor overactivity. J Urol 2006;176: 2530–4.

- Kleinman NL, Odell K, Chen CI, et al. Persistence and adherence with urinary antispasmodic medications among employees and the impact of adherence on costs and absenteeism. J Manag Care Spec Pharm 2014;20:1047–56.

- Koneru S, Shishov M, Ware A, et al. Effectively measuring adherence to medications for systemic lupus erythematosus in a clinical setting. Arthritis Rheum 2007;57:1000–6.

- Clifford S, Coyne KS. What is the value of medication adherence? J Manag Care Spec Pharm 2014;20:650–1.