Dear editor,

There is limited scientific research on the relationship between COVID-19 and erectile dysfunction (ED; defined as the persistent inability to attain and maintain an erection sufficient to permit satisfactory sexual performance [Citation1,Citation2]), and the available data are inconclusive. While there are some reports that COVID-19 infection may increase the risk of ED [Citation3,Citation4], other studies have not found a significant association. The number of relevant studies is limited, with most being case reports or small observational studies [Citation5]. It has been suggested that COVID-19 infection may increase the risk of ED due to the virus’s potential impact on blood vessels and the cardiovascular system, which are essential for erections [Citation5–7]. More in detail, COVID-19 is known to trigger a robust inflammatory response in the body, affecting blood vessels and the endothelium. ED is often associated with vascular problems that impair blood flow to the penis. COVID-19-related damage to blood vessels and endothelial cells could potentially contribute to ED by reducing blood flow and impairing the mechanism responsible for achieving and maintaining an erection [Citation8]. COVID-19 has also been associated with neurological symptoms in some cases; neurological damage caused by the virus could potentially impact nerves that are involved in the erectile response. The cavernosal smooth muscle may also be affected by COVID-19 [Citation9]. Psychological factors are known to play a significant role in the development and progression of ED [Citation10,Citation11]. The stress, anxiety, and depression associated with COVID-19 could contribute to ED. Google Trends (https://trends.google.com/home) can show search interest over time for specific keywords. An infodemiological study in 2022 [Citation12] suggested that during the COVID-19 pandemic the worldwide volume of Google searches, as presented on Google Trends, for “erectile dysfunction” had gradually increased over time. The results of this infodemiological analysis seemingly supported the conclusion of Adeyemi et al. [Citation3], that erectile dysfunction may be another less predictable but certainly unwarranted consequence of COVID19, which may also justify the decreased sexual health-seeking behaviors reported by Sansone et al. [Citation13]. However, the authors of [Citation12] did not take into account the fact that Google Trends has undergone several changes in the way it measures and presents search statistics over the years.

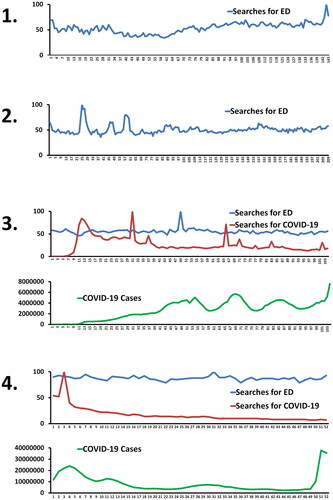

Based on the above, we aimed to reassess the searches for erectile dysfunction before, during and after the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic. We collected worldwide data on Google Trends, regarding the search term “erectile dysfunction” and “COVID-19” in the following time periods: January 1st 2004 to December 31st 2015, January 1st 2016 to December 31st 2019, January 1st 2020 to December 31st 2012 and from January 1st 2022 to December 31st 2022. The time periods were chosen following the changes in Google’s algorithms of reporting data in Google Trends (https://trends.google.com/home). The data for the first period were provided on a monthly basis whereas for the other three periods they were provided on a weekly basis. As we have previously shown, searches on the internet in English dwarf searches in all languages in almost any country [Citation14], thus to simplify the study we included only data for searches in English. We also collected data on recorded new COVID-19 cases worldwide as supplied by the World Health Organization (WHO; https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports). Analysis was done by calculating a linear trend model of “erectile dysfunction” versus time in each time period and with cross-correlation between “erectile dysfunction” versus “COVID-19” as well as versus new reported COVID-19 cases.

Only in the first-pre-COVID-19 period Google searches for “erectile dysfunction” increased over time (r: +0.26, p < 0.01); searches in all other time periods flattened out over time (). Furthermore, searches for “erectile dysfunction” were correlated (at lag 0) - and more particularly positively - with the waning searches for “COVID-19” and new reported COVID-19 cases (r: + 0.28 and +0.44, respectively, both p < 0.05) only during the last time period.

Figure 1. Searches for ED and COVID-19 from Google Trends (provided by Google as relative search volumes (RSVs): they are normalized with a minimum value of 0 and a maximum value of 100) and weekly COVID-19 cases from WHO (in absolute numbers) in the four time periods. Please note that in the first time period Google provides search data RSVs monthly, while in the other three periods this is done weekly. Time period 1: January 1, 2004 to December 31, 2016, time period 2: January 1, 2017 to December 31, 2019, time period 3: January 1, 2020 to December 31, 2021, time period 4: January 1, 2022 to December 31, 2022. The four time periods are defined by the dates when Google Trends implemented changes in the calculation of its results.

In conclusion, searches on Google Trends for "erectile dysfunction", from the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic (early 2020) to the end of 2022, show that there has been a consistent level of search interest for the term throughout this period. There are no significant and persistent changes in search interest that would suggest a sudden increase or decrease in the prevalence of the condition during the pandemic. Overall, it is not yet clear if there is a significant increase in the interest or prevalence of ED due to COVID-19. However, as with many aspects of the COVID-19 pandemic, ongoing research may help to clarify the relationship between the virus and ED.

Consent

All the Authors consent for this publication

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability statement

The data used in this work can be found at: https://zenodo.org/record/8091678

Additional information

Funding

References

- Anonymous. NIH consensus conference. Impotence. NIH consensus development panel on impotence. JAMA. 1993;270:83–90.

- Burnett AL, Nehra A, Breau RH, et al. Erectile dysfunction: AUA guideline. J Urol. 2018;200(3):633–641. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2018.05.004.

- Adeyemi DH, Odetayo AF, Hamed MA, et al. Impact of COVID 19 on erectile function. Aging Male. 2022;25(1):202–216. doi: 10.1080/13685538.2022.2104833.

- Hsieh TC, Edwards NC, Bhattacharyya SK, et al. The epidemic of COVID-19-Related erectile dysfunction: a scoping review and health care perspective. Sex Med Rev. 2022;10(2):286–310. doi: 10.1016/j.sxmr.2021.09.002.

- Nassau DE, Best JC, Kresch E, et al. Impact of the SARS-CoV-2 virus on male reproductive health. BJU Int. 2022;129(2):143–150. doi: 10.1111/bju.15573.

- Ismail AMA. Erectile dysfunction: the non-utilized role of exercise rehabilitation for the most embarrassing forgotten post-COVID complication in men. Aging Male. 2022;25(1):217–218. doi: 10.1080/13685538.2022.2108013.

- Ismail AMA. Post-COVID erectile dysfunction: the exercise may be a good considered complementary choice. Am J Mens Health. 2022;16(4):15579883221114983. doi: 10.1177/15579883221114983.

- Kaynar M, Gomes ALQ, Sokolakis I, et al. Tip of the iceberg: erectile dysfunction and COVID-19. Int J Impot Res. 2022;34(2):152–157. doi: 10.1038/s41443-022-00540-0.

- Unal S, Uzundal H, Soydas T, et al. A possible mechanism of erectile dysfunction in coronavirus disease-19: cavernosal smooth muscle damage: a pilot study. Rev Int Androl. 2023;21(4):100366. doi: 10.1016/j.androl.2023.100366.

- Li JZ, Maguire TA, Zou KH, et al. Prevalence, comorbidities, and risk factors of erectile dysfunction: results from a prospective Real-World study in the United Kingdom. Int J Clin Pract. 2022;2022:5229702–5229710. doi: 10.1155/2022/5229702.

- Rowland DL, Oosterhouse LB, Kneusel JA, et al. Comorbidities among sexual problems in men: results from an internet convenience sample. Sex Med. 2021;9(5):100416. doi: 10.1016/j.esxm.2021.100416.

- Mattiuzzi C, Lippi G, Henry BM. Estimating the global prevalence of erectile dysfunction during the COVID-19 pandemic. Aging Male. 2022;25(1):255–256. doi: 10.1080/13685538.2022.2120981.

- Sansone A, Mollaioli D, Cignarelli A, et al. Male sexual health and sexual behaviors during the first national COVID-19 lockdown in a Western country: a Real-Life, Web-Based study. Sexes. 2021;2(3):293–304. Indoi: 10.3390/sexes2030023.

- Tselebis A, Zabuliene L, Milionis C, et al. Pandemic and precocious puberty - a google trends study. World J Methodol. 2023;13(1):1–9. doi: 10.5662/wjm.v13.i1.1.