Abstract

Objectives

This cross-sectional study aimed to compare the sexual function (SF) and pelvic floor function of men with systemic sclerosis (SSc) with age-matched healthy controls (HC) and to identify the implications of clinical features on SF.

Material and method

Twenty SSc males and 20 HC aged 18–70 years completed eleven questionnaires assessing SF [International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF), Male Sexual Health Questionnaire (MSHQ)]; sexual quality of life: Sexual Quality of Life Questionnaire-Male (SQoL-M); pelvic floor function: Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire-Short Form 7 (PFIQ-7), fatigue, depression, physical fitness, functional disability, and quality of life. Clinical data were collected.

Results

Significantly worse SF was observed in patients (median IIEF erectile function 12 in SSc versus 29 in HC, p < 0.001), with 70% reporting erectile dysfunction (ED) compared to 15% in HC. However, no significant difference was observed regarding pelvic floor function (median PFIQ7 8.8 in SSc versus 7.0 in HC, p = 0.141). Impaired SF was associated with higher disease activity, increased systemic inflammation, more pronounced fatigue, reduced physical fitness, severe depression, impaired overall quality of life, dyspepsia, and arthralgias (p < 0.05 for all).

Conclusions

Sexual dysfunction is highly prevalent in our SSc patients, whereas pelvic floor dysfunction is unlikely to be associated with these problems.

Background

Systemic sclerosis (SSc) is a rare chronic autoimmune disease characterized by endothelial dysfunction, microvascular damage, immune dysregulation, and fibrosis of the skin and internal organs [Citation1]. Worldwide, the incidence of SSc is estimated at 14 new cases per million per year and the prevalence at 176 cases per million. It affects women 4–6 times more often than men and usually manifests between the age of 35 and 64 [Citation2]. Vascular complications of SSc include Raynaud’s phenomenon (RP), digital ulcers, pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH), and scleroderma renal crisis. One of the vascular complications, erectile dysfunction (ED), frequently remains unaddressed [Citation3], despite its prevalence ranging from 77% to 81% [Citation4].

The association between SSc and ED was first described by Lally and Jimenez in 1981 [Citation5]. Since then the mechanisms of ED in SSc have been relatively well studied, and nowadays, a combination of penile fibrotic and vascular abnormalities and psychological factors is assumed to play a key role [Citation4]. Conversely, abnormalities in the hormonal profile, particularly in serum testosterone, follicle-stimulating hormone, luteinizing hormone, prolactin, estradiol, or thyroid hormones were not demonstrated [Citation3]. In the early phase of SSc, penile RP with a decrease in arterial inflow predominates. Following hypoxia, cytokines such as transforming growth factor (TGF)-β, platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), and TGFβ receptors are overexpressed in the corpora cavernosa. At the same time, penile smooth muscle cells release endothelin 1 (ET1) and induce the expression of the B-type ET1 receptor. These molecular processes contribute to fibrotic remodeling of the corpora cavernosa and concomitant veno-occlusive dysfunction [Citation6]. Increased ET1 expression is involved in both fibrotic lesion development and vascular dysfunction and increased circulating levels of ET1 were found both in SSc with primary vascular disease and pulmonary hypertension and in patients with diffuse cutaneous (dc)SSc with extensive tissue fibrosis [Citation7]. Vascular damage of the penis is present in all patients already at the disease onset, regardless of the presence of sexual dysfunction [Citation6].

Therefore, ED is highly probable in men with SSc. The European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (EULAR) Scleroderma Trial and Research (EUSTAR) multicenter study evaluated the prevalence of sexual dysfunction in 130 men with SSc. Based on the results of the International Index of Erectile Function-5 (IIEF-5) questionnaire, 81% reported some degree of ED, of which 38% had severe ED [Citation8]. Another cross-sectional study of Keck et al. [Citation9] primarily analyzed an association between nailfold capillary abnormalities and the presence and severity of ED in 78 men with SSc. The case-control study of Hong et al. [Citation10] compared the risk of developing ED in 43 men with SSc and 23 men with rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Nevertheless, the number of studies comparing the prevalence of ED in men with SSc to a healthy population is currently very scarce. Therefore, the aim of our study was to determine the extent and severity of sexual dysfunction in male SSc patients compared to age-matched healthy controls (HC) to better understand the actual impact of the disease on sexual health. Furthermore, we aimed to assess the degree of pelvic floor dysfunction since pelvic floor muscles play a significant role in sexual function (SF) in both sexes [Citation11]. Lastly, we aimed to evaluate the associated risk factors and predictors of sexual dysfunction in men with SSc, which have been addressed rarely and often with contradictory results.

Material and methods

Patients and healthy controls

Based on inclusion criteria that comprised the fulfillment of the EULAR/American College of Rheumatology (ACR) classification criteria for SSc in 2013 [Citation12] and the age between 18 and 70 years, we consecutively recruited 20 male patients with SSc from the Institute of Rheumatology in Prague (IoRP) between January 2019 and December 2021. Patients who did not meet the inclusion criteria or were diagnosed with another systemic rheumatic disease or severe chronic disease, as specified elsewhere [Citation13], were excluded from the study. Age-matched healthy individuals (without rheumatic or severe chronic diseases [Citation13]) were recruited from the HC Register at the IoRP consisting mainly of employees and their relatives. This cross-sectional study was approved by the Ethics Committee at the IoRP and all individuals signed written informed consent prior to enrolment in the study.

Assessment methods

Patients with SSc, as well as HC, were asked to complete a set of standardized and validated questionnaires assessing SF, sexual quality of life, pelvic floor function, fatigue, depression, physical fitness, functional disability, and overall quality of life, the names of which are listed below. All patients underwent the clinical examination performed by a rheumatologist experienced in diagnosing and treating SSc and routine laboratory tests. We recorded demographic characteristics including age at enrolment, education levels (primary, secondary, and higher education), current partnership and sexual activity status, disease-related features such as disease duration (from the first non-RP symptom), disease activity determined by the European Scleroderma Study Group (ESSG) SSc activity score [Citation14], skin involvement evaluated by the modified Rodnan skin score (mRSS) [Citation15], current treatment including ED medication, SSc-associated symptoms, and capillaroscopy and pulmonary function tests performed using standard methods [Citation16,Citation17]. We collected the following laboratory parameters: serum C-reactive protein (CRP), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), antinuclear antibodies (ANA), and autoantibodies of the ENA complex that were analyzed as described elsewhere [Citation18]. SF was evaluated by the IIEF which addresses relevant domains of male SF such as erectile function, orgasmic function, sexual desire, intercourse satisfaction, and overall satisfaction [Citation19], and Male Sexual Health Questionnaire (MSHQ) assessing male SF in three main scales (erection, ejaculation, and satisfaction scale) and three additional scales (ED bother, ejaculation dysfunction bother, sexual activity, and desire scale) [Citation20]. Furthermore, the Sexual Quality of Life Questionnaire-Male (SQoL-M) was used to assess the quality of men’s sexual life [Citation21]. To evaluate the pelvic floor function and its impact on patients’ daily activities, we used the Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire-Short Form 7 (PFIQ-7) modified for men which is available for clinical assessments [Citation22], but has not been psychometrically validated yet all these questionnaires were translated into Czech and have been validated [Citation23]. Moreover, respondents were asked some additional questions about the presence of pelvic floor dysfunction symptoms and their severity, which are not covered by the standardized questionnaire and to evaluate the subjective sexual life importance that was quantified by a visual analog scale (VAS) ranging from 0 (not important at all) to 10 (extremely important). Other patient-reported outcomes (PROs) were used to assess fatigue: Multidimensional Assessment of Fatigue (MAF) scale [Citation24] and the Fatigue Impact Scale (FIS) [Citation25], depression: the Beck’s Depression Inventory-II (BDI II) [Citation26], physical fitness: the Human Activity Profile (HAP) [Citation27], functional disability: the Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) [Citation28], functional disability determined by SSc symptoms: the Scleroderma HAQ (SHAQ) [Citation29], and quality of life: the 36-Item Short Form Survey (SF-36) [Citation30]. All these questionnaires were translated into Czech and validated, as described previously [Citation13].

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 25 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL) and GraphPad Prism version 5 (version 5.02; GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA) and are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median [interquartile range (IQR)]. For power analysis, we used Cohen’s d to estimate a power curve for independent groups t-test and the sample size of n = 20 in each group. The normal distribution was determined by Shapiro–Wilk and Kolmogorov–Smirnov normality tests. Differences between SSc and HC were assessed by the independent sample t-test or Mann–Whitney U test, and by the Chi-squared test for categorical variables. The associations between SF and clinical features on the level of bivariate relationships were analyzed using the point-biserial correlation and the Spearman correlation coefficient depending on the variable type. Multiple linear regression was applied to predict SF scores by patients’ PRO scores and disease-specific features. However, taking our sample size and analysis power into account, we limited each model to a maximum of two predictors, This selection process was guided by the strong correlation observed within each group (PRO scores and disease-specific features) of variables, which could potentially introduce multicollinearity in the regression models. Therefore, we chose only the predictor with the strongest correlation with a particular outcome from each group. Statistical significance was defined as p-value <0.05.

Results

Out of 23 eligible men with SSc, 20 completed the questionnaires. Three patients refused to fill in the questionnaires, of which one did not want to participate in any research, one did not want to answer intimate questions, and one was unable to fill out the questionnaires in writing due to his hand disability. The power analysis showed that the sample of 20 individuals in each group is sufficiently powered (using conventional levels 0.05 and 0.2 for type I and type II error, respectively) to detect large effects (differences between SSc patients and HC). Basic sociodemographic, clinical, and laboratory data including pharmacotherapy for 20 SSc males and characteristics of 20 HC are shown in . A significantly lower number of SSc patients were sexually active and had currently a partner compared to HC. As expected, significantly worse scores were observed in SSc regarding fatigue, depression, physical fitness, functional ability, and quality of life ().

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics, disease-related clinical and laboratory features of male patients with SSc and healthy controls.

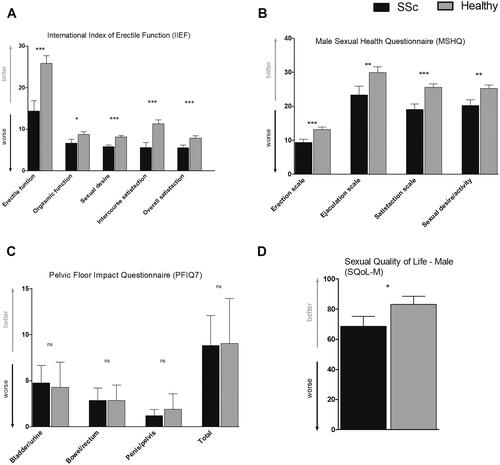

Compared to HC, patients with SSc also reported significantly worse function in all domains of two questionnaires assessing SF (IIEF, MSHQ) and sexual quality of life (SQoL-M). No significant differences were found between groups in pelvic floor function (PFIQ-7) (, Supplementary Table 1). Based on the IIEF cut-off score, the percentage of ED in SSc was 70% (versus 15% in HC). Due to the significant difference in the numbers of sexually active men between groups, we also performed a subanalysis of sexually active men only, into which we included 14 sexually active men with SSc (mean ± SD age: 51.4 ± 10.5 years) and 19 HC (50.8 ± 8.1 years). The differences in SF parameters remained statistically significant except for the quality of sexual life (SQoL-M) ().

Figure 1. Sexual function and pelvic floor function in men with SSc and healthy controls. (A) According to IIEF, patients with SSc exhibited significantly worse scores in all five domains (Erectile function, Orgasmic function, Sexual desire, Intercourse satisfaction, and Overall satisfaction) compared to healthy controls. (B) Scores in all scales of MSHQ (Erection scale, Ejaculation scale, Satisfaction scale, and Sexual desire/activity scale) were significantly decreased in men with SSc compared to healthy controls. (C) No significant differences were observed between patients with SSc and healthy controls in any of the pelvic floor function domains measured by PFIQ-7. (D) Sexual quality of life (SQoL-M) was significantly decreased in SSc patients compared to healthy individuals. Data are presented as mean (columns) and standard error of the mean (whiskers). *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ns: not significant

Table 2. Sexual function and pelvic floor function in sexually active men with SSc and sexually active healthy controls.

In bivariate analysis, worse SF was significantly associated with higher disease activity (ESSG), increased systemic inflammation (CRP, ESR), greater fatigue (FIS, MAF), reduced physical fitness (HAP), more severe depression (BDI-II), impaired quality of life (SF-36), severe dyspepsia (SHAQ VAS-II) and arthralgias (). We have not observed any significant correlations with disease duration, mRSS, RP, digital ulcerations, lung and renal involvement, results of capillaroscopy and spirometry, pharmacotherapy, and autoantibodies. At the multivariate logistic regression level, increased systemic inflammation (CRP), greater fatigue (FIS), more severe depression (BDI-II), and worse dyspepsia (SHAQ VAS-II) were independently associated with decreased SF ().

Table 3. Bivariate relationships of sexual function and pelvic floor function with selected clinical and laboratory parameters in men with SSc evaluated by Spearman’s or Pearson’s* correlation coefficient.

Table 4. Multivariate regression analysis predicting sexual function in men with SSc.

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated that men with SSc reported significantly worse SF with a percentage of ED of 70% compared to age-matched HC (15%). However, no significant difference was shown between the patients and HC regarding pelvic floor function. Worse SF in SSc patients was associated with higher disease activity, increased systemic inflammation, more pronounced fatigue, reduced physical fitness, severe depression, impaired quality of life, severe dyspepsia, and the presence of arthralgias. Multivariate analysis revealed that increased systemic inflammation, greater fatigue, severe depression, and worse dyspepsia could be independent predictors for sexual dysfunction.

The largest limitation of our study is the relatively small sample size. Although power analysis using Cohen’s d evaluating effect size shows that our study is sufficiently powered to detect at least large effects, we might have missed some medium and small effects. It is therefore imperative to underscore that our findings were derived from a notably limited patient sample size, which may potentially compromise the accuracy of our results and lead to lack of generalizability that may limit the broader applicability of our findings. Morover, owing to the limited participant pool, we were unable to assess the impacts of disease characteristics and treatment regimens which, if analyzed, would undoubtedly offer a more comprehensive insight into the issue of sexual dysfunctions in men with SSc. On the other hand, SSc is a very rare disease that predominantly affects women [Citation2], thus it might be challenging to obtain comprehensive data from a robust number of male patients, especially on such a sensitive topic within a single centre. Despite extensive multicentric EUSTAR evaluation of sexual dysfunction in 130 men with SSc from 22 centers in 13 countries [Citation8], which, however, did not include a comparison with HC, further investigation will require multicenter collaboration to obtain a sufficiently large sample of patients to verify these results. Furthermore, it would be beneficial to supplement the subjective evaluation of SF with an objective examination of the penile arteries by dynamic duplex ultrasound as recommended elsewhere [Citation31]. However, the aim of this work was not to evaluate the extent of microangiopathic changes in the penile arteries, which has already been well described in the past [Citation6,Citation7,Citation31,Citation32], but to compare the extent and severity of sexual dysfunctions of men with SSc with HC, and to investigate associations with novel parameters such as pelvic floor function, fatigue, depression, physical fitness, which have not been assessed to date. Another limitation of our study is the high volume of questionnaires that could potentially lead to an excessive data management demands and challenges in interpretating the findings [Citation33]. To avoid biased answers due to the respondent’s fatigue, we asked them to spread out the questionnaires filling over a day in case they feel tired. Nevertheless, according to the patients’ feedback, most respondents were able to complete the questionnaires within an hour. Most of them had enough time to fill in questionnaires during hospitalization, waiting for outpatient appointments by their rheumatologists, or at home. On the other hand, thanks to information from multiple questionnaires, we received pieces of information in different domains of monitored parameters, of which overlapping domains verified the results, and unique domains provided additional information.

A recent systematic review [Citation4] reported that the prevalence of ED in SSc ranges from 76.9% to 81.4% which is slightly more compared to our results. However, all included studies [Citation8–10] used a shortened version of the IIEF-5 questionnaire. A recent study [Citation34] using the IIEF-15 questionnaire reported that ED was observed in 53 of 60 Thai male SSc patients with a prevalence of 88.3%. However, the average age of the group was slightly higher (54.8 ± 7.2) than in our case (51.9 ± 9.1). Another ethnographically more similar study from Germany [Citation31] evaluated 64 men with SSc at a mean age of 52.3 ± 10.8 years in comparison with 123 age-matched healthy individuals using IIEF-15. According to this study, ED was significantly more frequent in patients with SSc with prevalence of 55% compared to 12.7% in HC which, on the contrary, seems relatively modest compared to our results and results published so far. However, patients achieved similar average score in terms of ED evaluation, specifically 12.0 in our study and 13.6 from Krittian et al. [Citation31], that were significantly lower than in HC with 29.0 in our study and 23.6 from Krittian et al. [Citation31]. On the contrary, the scores obtained in our group of healthy subjects seem to be quite high and the percentage of subjects with ED relatively low. Only 15% of the healthy subjects in our study reported some degree of ED which is at the lower end of the worldwide prevalence of ED estimate ranging from 13.1% to 71.2% following the IIEF definition of ED [Citation32]. On the other hand, the prevalence of ED worldwide shows a great deal of variation. Moreover, the 50-to-59-year-old group showed the greatest range of reported prevalence rates [Citation35]. However, to be more specific, the Dutch study with a robust sample of patients which shares the most demographic and cultural similarities with our study, reported a prevalence of 13.7% in the 41–50 age group and 23.7% in the 51–60 age group [Citation36] indicating a mild underestimation in our cohort. Nonetheless, it is essential to acknowledge that comparing our results directly to worldwide data may not be entirely accurate due to several factors. First, our sample size is relatively small, which means it only represents a small portion of the population and may not accurately reflect the overall prevalence. Second, our sample consists of healthy individuals, as we excluded individuals with severe chronic diseases, whereas prevalence rates from larger studies often encompass individuals with various health conditions, which can influence the prevalence of ED. Similarly, if we want to compare seemingly high mean IIEF-15 scores achieved by our 20 healthy males of mean age of 51.9 ± 9.1 years, it is challenging to find direct comparison with culturally similar cohorts with reported absolute values. Nevertheless, the study by Szuster et al. [Citation37] examined the impact of COVID-19 lockdown in 606 Polish men with a mean age of 28.5 ± 9.2 years. This study reported a mean score of the IIEF-15 erectile function domain of 22.3 in their healthy cohort, which is lower than the mean score of 26.2 ± 7.3 in our significantly older helathy controls. Even though it is impossible to compare the results of two cohorts of entirely different sample sizes and age ranges, Polish younger healthy males were more severely affected by the COVID-19 pandemic in terms of markedly worse scores in depression: 17.3% of them were diagnosed with mild depression, 6.1% with moderate depression, and 4.6% with severe depression according to BDI-II compared to 0% of mild/moderate/severe depression in our HCs. Higher depression scores, together with fear, media exposure, and loneliness were significantly associated with lower IIEF-15 scores [Citation37].

While there may be slight variations in the data regarding the prevalence of sexual dysfunction in men with SSc, it is evident that ED affects a substantially higher percentage of men with SSc than HC, and it is essential to continue raising awareness of this issue and actively encourage SSc patients to openly communicate their problems with their physicians.

Pelvic floor function is a novel parameter evaluating SF in SSc men; however, no significant difference was shown between SSc and HC. We assume that the etiology of sexual dysfunction in SSc males is primarily related to vascular involvement and fibrotic changes in the corpora cavernosa and it is unlikely that pelvic floor dysfunction plays a significant role.

In our study, we also demonstrated that worse SF in SSc was associated with higher disease activity, increased systemic inflammation, greater fatigue, reduced physical fitness, more severe depression, impaired quality of life, severe dyspepsia, and arthralgias. However, in the multivariate analysis, only increased systemic inflammation, greater fatigue, severe depression, and worse dyspepsia remained independent predictors of sexual dysfunction in SSc men. Compared to the existing research, we found a certain level of agreement in some of our results, while others differed. We have not observed any significant correlations with vascular alterations such as the presence of RP, digital ulcerations, nailfold microvascular alterations, and PAH. The study by Rosato et al. [Citation6] found that SSc patients with less vascular digital damage achieved better scores in SF than those with greater vascular damage. Similar to our study, Keck et al. [Citation9] did not find any associations between ED and the degree of nailfold microvascular alterations, digital ulcerations, PAH, or SSc subtype. Whereas another study demonstrated that ED correlated with higher mRSS, renal vasculopathy, PAH, and restrictive lung disease [Citation8]. Thus, associations between various clinical manifestations of microvasculopathy and the presence/severity of ED are not common findings of all available studies, as might have been expected. In line with our findings, the relationship between severe ED and higher disease activity score (ESSG) was previously presented by Foocharoen et al. [Citation8]. The associations of worse SF with greater fatigue, reduced physical fitness, severe depression, and worse quality of life might be expected, but has not been studied to date. Nevertheless, similar associations have already been described in other systemic rheumatic diseases [Citation38] and might reflect the chronic, progressive, and disabling nature of SSc and support a multifactorial etiology of sexual dysfunction.

Conclusion

To conclude, even though data from our study cannot be generalizable due to a very low sample size, it still supports the previous findings that men with SSc are affected by a high rate of more extensive sexual dysfunction, which is associated with several SSc-related features. This study not only builds upon existing research on sexual dysfunction in men with SSc, but also presents the first direct comparison between SSc males and age-matched HCs, and a complex analysis of several novel variables using a larger set of complimentary PROs with potential impact on SF. We also provide the first proof that pelvic floor dysfunction is not more prevalent in SSc males than in HC, and it probably does not contribute to more frequent and extensive sexual dysfunction in SSc males. This study revealed some gaps in our current clinical practice, including lack of time, tools, and personnel dedicated to diagnosing, multidisciplinary consulting, examining, and treating this specific clinical manifestation in men with SSc. On the other hand, our study provided the validated Czech versions of PROs assessing SF and pelvic floor function, freely available for routine clinical use throughout rheumatological diagnoses in the Czech Republic. This study also highlighted that for routine clinical practice, and to prevent potential overload of patients and the personnel evaluating the PROs, a careful selection of one representative PRO per clinical or functional domain is vital. Thus, it is imperative to continue researching these difficulties in terms of long-term progression, risk factors, and treatment options to provide new solutions for this generally neglected aspects of quality of life of male patients with SSc.

Informed consent statement

Patients provided informed written consent before the enrolment to the study.

Institutional review board statement

All relevant study documentation and amendments were approved by the independent Ethics Committee of the Institute of Rheumatology in Prague with reference number 10458/2017. It was conducted following the principles outlined in the declaration of Helsinki, the Guidelines of the International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) on Good Clinical Practise (GCP) Guideline E6 (R2) (EMA/CPMP/ICH/135/95) European Union (EU) Directive 95/46/EC, and other applicable regulatory requirements.

Data deposition

Data used in the study will not be shared openly.

Author’s contributions

M.T. and B.H. designed the study. S.O., B.H., M.T., M.Š., H.Š., L.Š., R.B., K.P., and J.V. collected patients’ data. M.K. and B.H. performed the statistical analysis. B.H. and M.T. prepared the original draft of the manuscript. All authors critically interpreted the results, reviewed the drafts, and approved the final manuscript.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (29.6 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all patients and HC who participated in the study and Xiao Švec for language editing.

Disclosure statement

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Data availability statement

Individual anonymized participant data will not be shared. Pooled study data, protocol, or statistical analysis plan can be shared upon request at [email protected].

Additional information

Funding

References

- Denton CP, Khanna D. Systemic sclerosis. Lancet. 2017;390(10103):1685–1699. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30933-9.

- Bairkdar M, Rossides M, Westerlind H, et al. Incidence and prevalence of systemic sclerosis globally: a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2021;60(7):3121–3133. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keab190.

- Jaeger VK, Walker UA. Erectile dysfunction in systemic sclerosis. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2016;18(8):49. doi: 10.1007/s11926-016-0597-5.

- Gao R, Qing P, Sun X, et al. Prevalence of sexual dysfunction in people With systemic sclerosis and the associated risk factors: a systematic review. Sex Med. 2021;9(4):100392–100392. doi: 10.1016/j.esxm.2021.100392.

- Lally EV, Jimenez SA. Impotence in progressive systemic sclerosis. Ann Intern Med. 1981;95(2):150–153. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-95-2-150.

- Rosato E, Aversa A, Molinaro I, et al. Erectile dysfunction of sclerodermic patients correlates with digital vascular damage. Eur J Intern Med. 2011;22(3):318–321. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2010.09.013.

- Aversa A, Proietti M, Bruzziches R, et al. Case report: the penile vasculature in systemic sclerosis: a duplex ultrasound study. J Sex Med. 2006;3(3):554–558. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2005.00169.x.

- Foocharoen C, Tyndall A, Hachulla E, et al. Erectile dysfunction is frequent in systemic sclerosis and associated with severe disease: a study of the EULAR scleroderma trial and research group. Arthritis Res Ther. 2012;14(1):R37. doi: 10.1186/ar3748.

- Keck AD, Foocharoen C, Rosato E, et al. Nailfold capillary abnormalities in erectile dysfunction of systemic sclerosis: a EUSTAR group analysis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2014;53(4):639–643. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ket392.

- Hong P, Pope JE, Ouimet JM, et al. Erectile dysfunction associated with scleroderma: a case-control study of men with scleroderma and rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2004;31(3):508–513.

- Stein A, Sauder SK, Reale J. The role of physical therapy in sexual health in men and women: evaluation and treatment. Sex Med Rev. 2019;7(1):46–56. doi: 10.1016/j.sxmr.2018.09.003.

- van den Hoogen F, Khanna D, Fransen J, et al. 2013 Classification criteria for systemic sclerosis: an American college of rheumatology/european league against rheumatism collaborative initiative. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65(11):2737–2747. doi: 10.1002/art.38098.

- Heřmánková B, Špiritović M, Šmucrová H, et al. Female sexual dysfunction and pelvic floor muscle function associated with systemic sclerosis: a cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(1):612. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19010612.

- Valentini G, Bencivelli W, Bombardieri S, et al. European scleroderma study group to define disease activity criteria for systemic sclerosis. III. Assessment of the construct validity of the preliminary activity criteria. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62(9):901–903. doi: 10.1136/ard.62.9.901.

- Clements P, Lachenbruch P, Seibold J, et al. Skin thickness score in systemic sclerosis: an assessment of interobserver variability in 3 independent studies. J Rheumatol. 1993;20(11):1892–1896.

- Cutolo M, Pizzorni C, Sulli A. Capillaroscopy. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2005;19(3):437–452. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2005.01.001.

- Miller MR, Hankinson J, Brusasco V, et al. Standardisation of spirometry. Eur Respir J. 2005;26(2):319–338. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00034805.

- Štorkánová H, Oreská S, Špiritović M, et al. Plasma Hsp90 levels in patients with systemic sclerosis and relation to lung and skin involvement: a cross-sectional and longitudinal study. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):1. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-79139-8.

- Rosen RC, Riley A, Wagner G, et al. The international index of erectile function (IIEF): a multidimensional scale for assessment of erectile dysfunction. Urology. 1997;49(6):822–830. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(97)00238-0.

- Rosen RC, Catania J, Pollack L, et al. Male sexual health questionnaire (MSHQ): scale development and psychometric validation. Urology. 2004;64(4):777–782. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2004.04.056.

- Abraham L, Symonds T, May K, et al. Psychometric validation of a sexual quality of life questionnaire for use in men with premature ejaculation or erectile dysfunction. J Sex Med. 2008;6(8):2244–2254. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00749.x.

- Beyond PT. Pelvic floor impact questionnaire – short form 7 - male. 2016 [updated 2016–2023 April 25]. Available from: https://physicaltherapybeyond.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/male-pelvic-floor.pdf

- Heřmánková B, Šmucrová H, Mikulášová M, et al. Validace české verze dotazníků hodnotících sexuální funkci a funkci pánevního dna u mužů. Ceska Revmatol. 2021;29(4):133–143.

- Piper BF, Dibble SL, Dodd MJ, et al. Paul SM, editors. The revised piper fatigue scale: psychometric evaluation in women with breast cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1998;25(4):677–684.

- Fisk JD, Ritvo PG, Ross L, et al. Measuring the functional impact of fatigue: initial validation of the fatigue impact scale. Clin Infect Dis. 1994;18(1):S79–S83. doi: 10.1093/clinids/18.supplement_1.s79.

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown G. Beck depression inventory–II. Lutz (FL): Psychological Assessment Resources; 1996.

- Fix AJ, Daughton D. Human activity profile: professional manual. Lutz (FL): Psychological Assessment Resources; 1988.

- Fries JF, Spitz P, Kraines RG, et al. Measurement of patient outcome in arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1980;23(2):137–145. doi: 10.1002/art.1780230202.

- Steen VD, Medsger TA. The value of the health assessment questionnaire and special patient‐generated scales to demonstrate change in systemic sclerosis patients over time. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40(11):1984–1991. doi: 10.1002/art.1780401110.

- Ware JE, Jr, Gandek B. Overview of the SF-36 health survey and the international quality of life assessment (IQOLA) project. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51(11):903–912. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(98)00081-x.

- Krittian SM, Saur SJ, Schloegl A, et al. Erectile function and connective tissue diseases. Prevalence of erectile dysfunction in german men with systemic sclerosis compared to other connective tissue diseases and healthy subjects. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2021;39(4):52–56. doi: 10.55563/clinexprheumatol/e9n3n9.

- Kessler A, Sollie S, Challacombe B, et al. The global prevalence of erectile dysfunction: a review. BJU Int. 2019;124(4):587–599. doi: 10.1111/bju.14813.

- Vickers AJ. Multiple assessment in quality of life trials: how many questionnaires? How often should they be given? J Soc Integr Oncol. 2006;4(3):135–138. doi: 10.2310/7200.2006.017.

- Sirithanaphol W, Mahakkanukrauh A, Nanagara R, et al. Prevalence of erectile dysfunction in thai scleroderma patients and associated factors. PLoS One. 2023;18(1):e0279087. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0279087.

- McCabe MP, Sharlip ID, Lewis R, et al. Incidence and prevalence of sexual dysfunction in women and men: a consensus statement from the fourth international consultation on sexual medicine 2015. J Sex Med. 2016;13(2):144–152. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2015.12.034.

- De Boer B, Bots M, Lycklama A Nijeholt A, et al. Erectile dysfunction in primary care: prevalence and patient characteristics. The ENIGMA study. Int J Impot Res. 2004;16(4):358–364. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3901155.

- Szuster E, Pawlikowska-Gorzelanczyk A, Kostrzewska P, et al. Mental and sexual health of men in times of COVID-19 lockdown. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(22):15327.

- Perez-Garcia LF, Te Winkel B, Carrizales JP, et al. Sexual function and reproduction can be impaired in men with rheumatic diseases: a systematic review. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2020;50(3):557–573. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2020.02.002.