ABSTRACT

This introduction to the special issue on ‘Arts-based approaches, migration and violence: intersectional and creative perspectives’ highlights the complexities and paradoxes in relation to existing debates in the field. Drawing on the emerging body of rich work that has recognised the importance of arts-based approaches within research on migration and violence, the introduction provides a critical assessment of the nature of the connections between the two in methodological, empirical and conceptual ways. It explores these intersections across multiple geographical scales, temporalities and imaginations through innovative creative research. In contributing to these debates, the introduction and the papers included in this special issue examine the potential for new insights, understanding and transformations to emerge through engaging with visual, performative, visceral, embodied and collaborative arts-based research. Yet, it also addresses some epistemological and ethical concerns including tensions around participation, positionality, co-production and the decolonisation of research. The introduction also aims to move beyond evaluating the benefits and drawbacks of arts-based approaches and provides a conceptual frame delineated as ‘migration-violence creative pathways’ that emphasise feminist and embodied perspectives. The frame does not prescribe how to engage with the creative arts, but rather encapsulates the variety of ways to do so. Finally, we set out an agenda for future creative research on migration-violence connections that highlights some practical, epistemological and conceptual suggestions for critically and productively engaging with arts-based approaches.

From being subjects of study we were then ‘humanised’ and then I felt at the same level as the audience – from strangeness to recognition’ (Brazilian migrant woman survivor of gendered violence from Migrants in Action in London – McIlwaine et al. Citation2022a)

There are currently multiple ‘creative turns’ emerging throughout the social sciences, from geography (Hawkins Citation2013), to archaeology (Russell and Cochrane Citation2014), and politics and international relations (Harman Citation2019), and of most relevance to this special issue, in migration (Martiniello Citation2022), gender and feminist studies (Gubar Citation2000), and mobilities scholarship (Barry et al. Citation2023). Embracing the arts has continued apace, despite a range of critiques of these shifts from different perspectives (Mould Citation2020), and claims that these are really ‘re-turns’ (de Leeuw and Hawkins Citation2017, Citation2019). Indeed, the primary clarion call has been that engagement with creativity and the arts will facilitate higher quality and more ethical research, improve understanding, and reach beyond the academy. Yet developing more penetrating knowledge of sensitive and complex issues beyond the text through arts-based research has been a methodological genre since the 1970s and especially since the 1990s (Chilton and Leavy Citation2014). Focused on exploring the expressive form of life and living (Barone and Eisner Citation2012), this entails non-verbal or pre-verbal and affective language-making, performative, sensory and aesthetic engagements, as well as the creation of embodied and visceral effects (Bagnoli Citation2009; Coemans and Hannes Citation2017; Leavy Citation2017). Migration scholars have been swift to welcome this turn as part of their wider efforts to subvert damaging representations of migrants and refugees and to prioritise alternative forms of knowledge production (Desille and Nikielska-Sekula Citation2021; Jeffery et al. Citation2019; Lenette Citation2019). In focusing primarily on marginalised populations, arts-based research has increasingly engaged with how migrants, and especially women, deal with structural and direct forms of violence as they negotiate belonging in hostile societies (Kaptani et al. Citation2021; Marnell, Oliveira, and Hoosain Khan Citation2021; Mijić and Parzer Citation2022; Oliveira Citation2019; O'Neill et al. Citation2019). While this emerging body of rich work has made great strides in recognising the importance of arts-based approaches within research on migration, there remains considerable scope to engage more fully and critically with the nature of the connections between migration and violence in methodological, empirical and conceptual ways. This is therefore the focus of this special issue that explores these intersections across multiple geographical scales, temporalities and imaginations through innovative creative research.

In making contributions to these debates, the papers in this special issue examine how, rather than being tools of dissemination alone, arts-based approaches can deepen understandings of the links between migration and violence, and can potentially engender transformation. In different ways, the papers all argue for the benefits of engaging with the visual, performative, visceral, embodied and collaborative dimensions of researching (Kara Citation2015; Leavy Citation2017; Vacchelli Citation2018). Yet, they also address a series of epistemological and ethical concerns alongside these opportunities and speak to dilemmas underlying many of the questions provoked by creative engagement. On the one hand, such approaches offer opportunities for, imperfectly and partially, mitigating power imbalances among researchers, participants and artists, and for generating and sharing knowledges different from those produced through more traditional methods (Coemans and Hannes Citation2017). On the other hand, arts-based participatory methods in particular can risk becoming a ‘new tyranny’ (to borrow from Cooke and Kothari Citation2001) if they are seen as a panacea for redressing fraught issues around participation, positionality, co-production and the decolonisation of research (Nunn Citation2022; Salma, Bita, and Kennedy Citation2023). These concerns become particularly acute in the context of research on borders, violence, race, gender and sexualities among marginalised groups (Erel, Reynolds, and Kaptani Citation2017; McLean Citation2022).

This special issue also aims to move beyond merely evaluating the benefits and drawbacks of creative approaches to researching migration and violence. As arts-based methods move increasingly into the academic mainstream, it seems an appropriate moment to advance steps already taken (Desille and Nikielska-Sekula Citation2021; Jeffery et al. Citation2019; Lenette Citation2019; O’Neill et al. Citation2019) towards a more profound and nuanced conceptualisation of the varied and intersecting creative approaches developed in research on the topic. This special issue therefore puts forward a conceptual frame adapted from the ‘creative translation pathways’ proposed by McIlwaine (Citation2024) that also incorporates established and more recent thinking around the continuum of violence (Kelly Citation1988) in relation to migration across multiple scales (Faria Citation2017; McIlwaine and Evans Citation2020). With an emphasis on feminist perspectives that foreground embodiment (Ahmed Citation2001; Grosz Citation1994), we delineate ‘migration-violence creative pathways’.

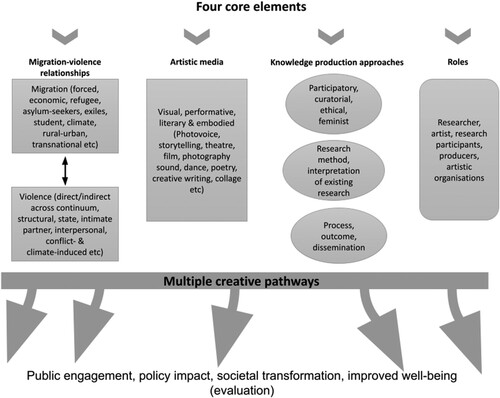

We consider there to be four key elements that influence the creative pathways ultimately followed when carrying out arts-based work on migration and violence. The first element is the specific interrelations between migration and violence with which the research engages. The second is the type or types of artistic media used to address the migration-violence nexus under study. The third element is the range of knowledge production approaches and practices that may be used to carry out arts-based research, ranging from more participatory to more curatorial approaches. The final element relates to the complex roles of researchers, artists and participants, and how these roles and relationships are defined and evolve. Decisions taken regarding each of these dimensions will have a decisive impact on the migration-violence creative pathways subsequently followed. These pathways can have singular or multiple aims that might include deepening understanding, structural transformation, resistance, raising visibility, public engagement, societal and policy impact, enhancing well-being, and/or encouraging belonging.

Through this proposed conceptual approach, this special issue therefore addresses the relationships inherent within migration and violence and how creative engagements can yield new insights, understandings and transformations as a result. Our perspective is informed by a transnational and intersectional approach to migration (McIlwaine Citation2010; McIlwaine et al. Citation2024; Ryburn Citation2018; Citation2022; also Bastia et al. Citation2023). We understand cross-border migration as a process that happens across, and contributes to the construction of, fluid and mutable ‘transnational social spaces’ (Levitt and Jaworsky Citation2007). That is not to deny the fundamental role of borders and the nation-state in governing (im)mobility; rather, transnational social spaces are formed because of, and in spite of, nation-state borders. Although they do not cross international borders, the experiences of internal migrants have also been understood as occurring across and constructing social spaces – for example, between rural and urban areas (Bowstead Citation2017). Moreover, internal and transnational migration are often interconnected, with internal migration often a precursor to transnational migration (McIlwaine Citation2012). People’s ability to move through, and role in constructing, these spaces is highly contingent on their multiple and intersecting social identities (gender, sexuality, race, class, among others). In other words, it is imperative to consider transnational social spaces through an intersectional lens. Intersectionality is ‘a method and a disposition, a heuristic and analytic tool’ (Carbado et al. Citation2013, 303) that enables us to analyse the everyday lived experiences of being at the crossroads of several or multiple structures of oppression.

Reflecting this perspective, in terms of our understanding of violence and migration, we take a lead from what Menjívar and Drysdale Walsh (Citation2019) refer to as the ‘spatial continuum of violence’. This encapsulates how migrants across the world often face multiple forms of violence across their migration trajectories from where they move, along their journeys and when they arrive in their destinations (Ryburn Citation2022). The ‘slow violence’ of intersectional exploitation, exclusion and institutional discrimination are marked for migrants everywhere, especially for women who are also often survivors of gender-based and intimate partner violence (Mayblin, Wake, and Kazemi Citation2020; McIlwaine and Evans Citation2023; Parreñas, Kantachot, and Silvey Citation2021; Phillimore et al. Citation2022). Building on recent work in feminist geography (Brickell and Maddrell Citation2016; Fluri and Piedalue Citation2017), and particularly in migration studies (Mountz Citation2017; Wilkins Citation2017), we conceptualise violence as occurring across geographical scales from the body to the home to the nation-state and transnationally. Adapting Kelly’s (Citation1988) classic continuum approach to sexual violence, we therefore view violence as multiscalar, complex, embodied, routinised and mutually intersecting in damaging ways across and within multiple borders (McIlwaine and Evans Citation2020; McIlwaine et al. Citation2024).

The remainder of this introduction outlines the main current debates in relation to creative engagements around violence and migration. It then outlines our ‘migration-violence creative pathways’ in greater depth. We then set out our agenda for future research that highlights areas that require more research as well as some key issues to take into account in relation to ethical, transformative and decolonial knowledge production through engagements with the arts, and the role of various actors in the process. From our initial workshop in November 2021 through to completion of the final papers, our contributors’ reflections and theorising have been fundamental to the development of the concepts and agenda laid out here, and their papers are introduced and integrated into the final two sections of this Introduction.

Debating arts-based research, violence and migration

The upsurge in arts-based research and approaches in recent years means that any overview cannot be exhaustive. Instead, this section provides an analysis of the current state of the art in relation to arts-based research in the social sciences that addresses the nexus between violence and migration. First, we outline some of the core issues in arts-based research across the social sciences generally. Next, we address arts-based research on violence, before turning specifically to examine creative research on violence and migration. We suggest that, either implicitly or explicitly, much arts-based research about or with migrants is also concerned with violence, seeking as it often does to disrupt and challenge dominant discriminatory representations of migrants, and/or to more directly reveal the multiple forms of structural and direct violence affecting them. We discuss a range of creative approaches that have been used for researching violence and migration, and reflect on the promises and challenges they present.

It is worth noting that there have been multiple terms developed for capturing the essence of ‘arts-based research’ with Chilton and Leavy (Citation2014) identifying 26. These span the social sciences from education and health research and across sociology, anthropology, geography and political science. What these terms share is that while not exclusively, the majority of arts-based research is qualitative in nature. Arts-based approaches represent a move away from interpreting existing art towards a more active form of meaning making through creating art forms as part of the research process (Springgay Citation2005). This might still entail using the arts as ‘knowledge translation’ to communicate research findings and reach wider audiences (Kukkonen and Cooper Citation2019), but increasingly it means more than this. This depends on the configuration of researcher as an artist, researcher using arts-based methods with participants, researcher collaborating with an artist(s), and a researcher collaborating with an artist(s) and participants (Carvajal Citation2020). Researchers can also be migrants and artists and combinations of all of these roles and identities. In this special issue, we use these terms fluidly to reflect the fluidity of these varied roles and identities. These arrangements can be developed across a diversity of media that can broadly include the visual, performing, and the literary within which there are more specific types (Leavy Citation2014). (see also below).

Much arts-based work reflects critical, post – and decolonial and especially feminist commitments linked with the importance of challenging power structures and recognising that research can only ever create situated truths (Haraway Citation1988; also Kara Citation2015; Lenette Citation2022). Furthermore, such disciplinary and epistemological stances that prioritise challenging hegemonies, promoting social inclusion and ensuring that the voices of the excluded are heard and acted upon, lend themselves to arts-based approaches (Coemans and Hannes Citation2017; Harman Citation2018; Keifer-Boyd Citation2011). So too does their concern with engaging with embodiment and lived experience in research. Drawing on long-standing feminist research (Ahmed Citation2001; Grosz Citation1994), embodiment refers to the process of ‘living enquiry’ through which the body understands and lives experiences (Springgay Citation2005, 902). This confronts a Cartesian mind–body separation and other dualisms such as subject – object, rational – emotional, and concrete – abstract (Leavy Citation2014). The lived and embodied experiences of researchers, artists, research participants and audiences can arguably be most effectively understood through arts-based research that captures the sensory, or what Pink (Citation2011) calls ‘multisensoriality’ in relation to ethnography. Whilst not all arts-based research has an explicit focus on embodiment, most does actively seek to evoke different, sensory ways of knowing and understanding (Bagnoli Citation2009; Leavy Citation2014). Certain types of embodied artistic and especially performative approaches can evoke empathy but also re-work understanding of sensitive issues (Harman Citation2016; Tarr, Gonzalez-Polledo, and Cornish Citation2018).

Given the political commitments behind much arts-based research – grounded in critical, post – and decolonial, anti-racist, and feminist beliefs – it is unsurprising that much of it has sought to address issues of violence. As noted above, our conceptualisation of violence in this special issue is deliberately broad. It includes direct and indirect forms of physical, sexual, and emotional intimate partner and interpersonal violence, as well as community, structural, symbolic, state and slow violence. With the creative work that addresses violence in the sense conceptualised here, of particular note has been research on understanding armed conflict and post-conflict transitions (Kinna and Whiteley Citation2020), and peace-building and transitional justice (Boesten and Scanlon Citation2021; Fairey and Kerr Citation2020; Fairey, Cubillos, and Muñoz Citation2023; Redwood, Fairey, and Hasić Citation2022). Everyday slow violence has also been explored from a creative perspective such as in work on housing (Pain, Heslop, and Heslop Citation2019) and debt (Brickell Citation2024). However, different forms of gendered violence have perhaps been the core focus for creative research.

There are many reasons why creative engagements have been mobilised to explore and understand gendered violence. These include being able to represent and communicate the brutality and complexity of violence in emotional and embodied ways (Cahill and Pain Citation2019; Pain and Cahill Citation2022). Forcer et al. (Citation2022, 2) use the term ‘aporia’ to denote ‘those seemingly illogical, irresolvable contradictions and paradoxes – that can arise in experiences of violence’ suggesting that arts-based methods are effective in capturing these. Creative approaches broadly defined have taken multiple forms ranging from examining how artists have interpreted the phenomenon of gender-based violence in society (Kaur Citation2017), to how audiences interpret art on such violence (Corcoran and Annette Citation2018), to how researchers as artists communicate gendered violence (Walker and Di Niro Citation2022). Yet using what can more specifically be defined as arts-based research methods, especially as part of wider participatory approaches, has been the most widely developed creative approach in relation to gendered violence (Thomas, Weber, and Bradbury-Jones Citation2022).

Of the significant arts-based methods work within health research that addresses gendered violence (Woollett et al. Citation2023), and especially in therapeutic contexts (Bird Citation2018), much has been feminist in nature and aims to counter extractive knowledge production, challenge power hierarchies and co-produce research with marginalised groups in more ethical ways (Christensen Citation2019; Parks et al. Citation2022). Arts-based approaches have also been key to efforts by researchers to prevent reproducing violence and retraumatising women, often through developing resistance. Art as resistance to gendered violence has become increasingly widespread as a campaign and research tool, especially in relation to performance ‘artivism’ in Latin America (Martin Citation2023; Serafini Citation2020). Yet resistance has taken other forms such as mural-making (Castañeda Salgado Citation2016) and collective memorialisation (Boesten and Scanlon Citation2021), working both with ‘elite’ artists (Shymko, Quental, and Mena Citation2022) and those from the margins (McIlwaine et al. Citation2022; Moura and Cerdeira Citation2021).

Implicitly or explicitly, much of the burgeoning creative research in migration studies also addresses multiple forms of violence, including gender-based violence. Whilst ‘classical’ research in migration studies has been strongly critiqued for its Eurocentrism and alliance with priorities of states in the Global North (Collins Citation2022; Mayblin and Turner Citation2020; Sammadar Citation2020), there is also an important critical, radical and militant tradition within the discipline (Fiddian-Qasmiyeh Citation2020; Garelli and Tazzioli Citation2013; Grosfoguel, Oso Laura, and Christou Citation2015). For many years, academics associated with this tradition have sought to carry out politically engaged, collaborative, ethical, and impactful research that highlights and challenges the multifarious discriminations faced by migrants, especially those who are marginalised. This critical stance and impulse towards more collective ways of working has been a driving force behind many migration studies scholars’ forays into the arts.

These have taken many forms. There is extensive scholarship that reflects on the interesting ways in which artists have been engaging with migration and mobilities since the 1980s, often addressing indirect and to a lesser extent direct forms of violence (Björgvinsson et al. Citation2020). Indeed, Björgvinsson et al.’s (Citation2020) special issue on art and migration provides a rich collection that covers a wide spectrum of academics and artists writing individually and collectively about the challenges of migration and living in the diaspora (Flynn Citation2022; Lelliott Citation2020; see also Miyamoto and Ruiz Citation2021). Most of the contributions in Björgvinsson et al.’s (2020) special issue address the state violence of borders, of asylum and of injustice. Some address art as violence (Motturi Citation2020 on writing), while others the violence of representation such as Klassen’s (Citation2020) discussion of the ethics of artistic outputs around feminicide in Mexico, among many others. The emphasis in this work is on working with artists rather than using arts-based methods with migrant research participants.

More participatory creative approaches to addressing the complex transnational continuum of violence as experienced by migrants and refugees have become increasingly popular in the last two decades. Important early examples include Frohmann’s (Citation2005) use of Photovoice to carry out the community-based ‘Framing Safety’ project with migrant women who have experienced intimate partner violence. Taking ‘a reflexive approach to the research process’ Frohmann (Citation2005, 1399) structured the project as a collaboration, and intended knowledge gained from it to ‘be used for further research and for individual and social action’. Kaptani and Yuval-Davis (Citation2008), also early practitioners of arts-based research methods in migration studies, take a similar epistemological stance to Frohmann in their participatory theatre work with migrant and refugee community groups. They conclude (2008: np) that, ‘The most important aspect of using participatory theatre technique as a sociological research methodology is that it produces a specific kind of new knowledge … its main characteristics can be summed up as embodied, dialogical and illustrative’.

A similar perspective is developed by O'Neill (Citation2009, 290) through the concept of ‘ethno-mimesis’ which signifies ‘a politics of feeling … a combination of ethnography and arts practice’. Drawing on Benjamin and Adorno, this process develops a theory of ‘sensuousness in critical tension with reason, rationality, objectification and the triangulation of data’ and entails research participants producing art using a range of participatory art forms themselves rooted in participatory action research (PAR). Indeed, the importance of PAR as a foundation for arts-based approaches has been noted by others (Jeffery et al. Citation2019; Thomas, Weber, and Bradbury-Jones Citation2022). O'Neill (Citation2009) addresses the ‘the asylum-migration nexus’ among refugee and asylum-seeking women, with this and subsequent work analysing women’s experiences of indirect and direct violence. It has been claimed elsewhere that the concept of ‘ethno-mimesis’ can be effective in examining traumatic experiences from a collaborative and embodied perspective (Bird Citation2018; Rutter Citation2021). The focus in such work tends to be on using various forms of theatre workshops and walking interviews to examine the state violence of gendered and racialised exclusion among women asylum-seekers and other migrants forced to negotiate a hostile immigration environment (Kaptani et al. Citation2021; O'Neill et al. Citation2019). Many further participatory arts-based methods have also emerged as useful in these violent contexts with some developing multi-media approaches (Nunn Citation2022), while others have focused on one approach such as storytelling (Sheringham and Taylor Citation2022) and Photovoice (Miled Citation2020).

In various ways, and while not always invoked, such work reveals migrants’ affective and embodied experiences linked to deep-seated structural power asymmetries that permeate their lives and which demand a political response (see also O’Neill Citation2011). Indeed, the wider relationships between creativity and resistance among marginalised populations have been long-established (Malik et al. Citation2020). Among marginalised migrants, a central tenet of arts-based approaches has been to provide fertile ground for engendering resistance (Erel et al. Citation2022). Much work focuses on systemic dimensions of violence (Biglin Citation2022), but increasingly, research has focused in particular on how women migrants have created space and mechanisms of resistance through art-based approaches (McIlwaine et al. Citation2022a; Pearce et al. Citation2017). The influence of Paulo Freire, Augusto Boal and Fals Borda, emerges as important (ibid.). Their work on critical knowledge production among the marginalised and the need to provide key spaces for interactions and ‘playback’ as well as the recognition of the relationships between actors and audience have been powerful and enduring (Erel, Reynolds, and Kaptani Citation2017; Kaptani and Yuval-Davis Citation2008; Kaptani et al. Citation2021). They have also been integral in arguing for decolonising research processes from ethical perspectives that centre the voices and experiences of those who have been historically excluded, colonised, racialised and abused (O'Neill et al. Citation2019).

That is by no means to say that using arts-based methods to address migration and violence ensures ethical research practice. Moving beyond traditional academic text can certainly provide a means of deep engagement around highly sensitive themes and an opportunity for different, more inclusive communication and understanding with and about migrants (Guruge et al. Citation2015; Nunn Citation2017; O'Neill et al. Citation2019; Vacchelli Citation2018). Moreover, such methods can evoke ‘stronger, quicker and often more empathetic responses from fellow participants … and other stakeholders’ (Guruge et al. Citation2015, 2). Arts-based migration research, and especially that which is participatory, can also, however, create and exacerbate concerns around ownership, anonymity, confidentiality, and representation in relation to topics where the stakes are already very high (Kaptani and Yuval-Davis Citation2008; Pratt and Johnston Citation2017; Oliveira and Vearey Citation2020). Björgvinsson et al. (Citation2020) provide a considered overview of the contentions around positionality and self-reflexivity raised by arts-based projects about migration or undertaken with migrants. They conclude that for any such project to be ethical it must always be ‘a veritably open-ended dialogical invitation to disagreement and critique’ (Björgvinsson et al. Citation2020, 6; see also Jeffery et al. Citation2019).

It is in this open-ended and dialogic spirit that we now turn to delineate our ‘creative migration-violence pathways’ approach. As evidenced in this brief analysis of the current state-of-the-art, creative research on migration and violence is moving from an initial, more experimental stage to become an increasingly common approach to addressing this complex and sensitive topic. Important work has been done that insightfully reflects on the potential of arts-based methods to enable richer, more collaborative engagement on these themes, as well as highlighting where the limitations of such methods lie. Drawing on this work and in particular the contributions to this special issue, we suggest a consolidation of these insights into a wider conceptual framing.

Delineating migration-violence creative pathways

Bearing in mind these debates, we have developed the notion of non-linear creative pathways to capture the complex variations in arts-based knowledge production around the migration-violence nexus. The six papers in this special issue have fed into the development of this pathways approach in a variety of ways, as will be outlined in this section. A majority of the papers published in this special issue focus on migration within or originating from Latin America, although in our initial workshopping stage we had more contributors focused on other regions. Whilst the Latin America focus is no doubt in part due to our own engagements with the region, we consider that it is also a reflection of the continent’s strong tradition of arts activism and participatory research as noted by people such as Paul Heritage in relation to the work of, among others, Augusto Boal in Brazil (McIlwaine et al. Citation2024). With reference to the papers in the special issue, we first indicate the core dimensions of these migration-violence creative pathways before suggesting how they may be continued through our proposed future research agenda. The aim is not to prescribe how to engage with the creative arts, but rather to encapsulate the variety of ways to do so.

We consider there to be four key elements that play a decisive role in the creative pathways ultimately followed when carrying out arts-based work on migration and violence (). These cover, first, the specific interrelations between migration and violence with which the research engages. As our review of the debates demonstrates, scholars have highlighted how migration and violence may be entangled in multiple ways. It is imperative to consider how different types of migration (internal, transnational, rural, urban, and so forth) and migrants’ social identities intersect with forms of violence that span indirect structural, systemic and symbolic violence – incorporating intersectional discrimination and exploitation – as well as direct intimate partner and interpersonal violence across a complex continuum. These operate across multiple scales from the body to the transnational and geopolitical and mutually reinforce each other.

The contributors to our special issue work across a wide range of such complex entanglements between migration and violence. Gideon’s paper (Citation2024) addresses state-inflicted direct violence during the Pinochet dictatorship in Chile (1973–1990) and the forced exile of over 200,000 people who opposed his regime. She specifically works with survivors of detainment in torture centres and concentration camps who subsequently went into exile in the United Kingdom (UK). Sheringham, Taylor and Duffy-Syedi (Citation2024) also work with survivors of state-inflicted violence and persecution who are refugees or are seeking asylum in the contemporary UK. Whilst Gideon’s work predominantly addresses the violence inflicted on exiles by the state in their country of origin, Sheringham, Taylor and Duffy-Syedi’s work critically addresses the slow violence of the state in the UK, and the specific ways this manifested during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Lopes Heimer’s contribution (Citation2024) also addresses the pervasion of hostile environment politics and bordering on the everyday lives of migrant women in the UK. She considers how such policies, which are embedded in colonial and racialised logics, enable and sustain the infliction of ‘intimate border violence’ by migrant womens’ intimate partners. This connects strongly with McIlwaine’s (Citation2024) paper, which provides an overview of extensive work carried out over a number of years on gender-based violence against Brazilian women in London. Spanning many different artistic engagements, McIlwaine’s work has sought to recognise the multiscalar, transnational and translocational power hierarchies that undergird gender-based violence.

Lines (Citation2024) and Ryburn’s (Citation2024) papers also address gender-based violence, although in different geographical contexts. Lines addresses the murder of internal and transnational migrant women in Quintana Roo, Mexico. She argues for urgent consideration of the systemic foundations of gender-based violence, feminicide and impunity and how these relate to the state. Ryburn analyses research with Colombian migrant women in Antofagasta, Chile. Research participants similarly reflected on the indivisibility of the multiple forms of violence – including physical, psychological, and economic – that they had faced in Colombia, on their migration journeys, and upon settlement in Chile, emphasising their embodied experiences of this violence.

Considering the varied embodied, visceral, and sensory ways of knowing and producing knowledge that can be achieved through different artistic media is the second element that determines the type of migration-violence creative pathway followed. Leavy (Citation2014) highlights the centrality of embodiment to visual, performing, and literary groups of artistic media, which she further breaks down into specific modes. Researchers, artists and research participants variously work with one medium or several simultaneously, depending on the aims of their research and/or creative engagements and practices, desired outputs and epistemological stance (Hawkins Citation2021). This is evidenced through the contributions to this special issue, which vary widely in their aims and outputs in the artistic forms they engage. We are united in our feminist, anti-racist beliefs and commitment to ethical research to challenge violence against migrants in all its manifestations. The artistic practices we have engaged to do this, however, and the specific aims we have in our research, differ significantly.

Both Lines and Gideon have conducted projects that aim at public memorialisation, although with different foci and using different artistic media. Lines is a member of a feminist collective of murallists, Las RestaurAmoras, who paint murals of victims of feminicide in public spaces in Quintana Roo. She argues that both the process and final artwork are essential to disrupting the dominant narratives around gender-based violence through public memorialisation. In her ‘Crafting Resistance’ project, Gideon also contributes to the public documentation of important ‘counter memories’. The exhibition and documentary produced as part of this work reveal and reflect upon over 100 craft objects made by Chileans who were detained as political prisoners during the Pinochet dictatorship and who were subsequently forced into exile in the UK. Gideon explains that the exhibition was only temporary while the film provides a more enduring type of memorial art, with a view to include a wide range of actors in discussions around transitional justice and reparations.

In their work with migrant women survivors of violence, Ryburn and Lopes Heimer have worked with a small group of women through a series of activities. The content produced through the activities has been interpreted with and by an artist or team of artists, as well as being reflected upon and analysed by research participants and the public. In the case of Ryburn, animated film was used to interpret the experiences of 11 Colombian migrant women as expressed through in-person workshops that incorporated a wide range of group activities, such as collectively mapping their migration journeys. The nuance and complexity that can be conveyed by the apparently simple medium of animation was essential for the endemic nature of multiple forms of violence in women's lived experiences. Whilst also using mapping techniques, Lopes Heimer developed an explicitly decolonial approach to arts-based methods from the outset of her project, drawing on the Latin American feminist ontology-epistemology of ‘cuerpo-territorio’ (body-territory). A ‘cuerpo-territorio’ approach informed her use of individual body mapping with 20 survivors of violence and the subsequent multi-layered and multi-media interpretations of these with and by a small team of artists.

Like Lopes Heimer, Sheringham, Taylor and Duffy-Syedi and McIlwaine have used multiple artistic media in their arts-based research on migration and violence. Via online workshops during the Covid pandemic, Sheringham, Taylor and Duffy-Syedi worked with two arts-based refugee organisations, Stories & Supper and Phosphoros Theatre, to ultimately co-produce two digitally published and performed pieces. They suggest that the combination of artistic media used in the workshops generated and were generative of play, movement, and laughter, creating moments which allowed them to interrupt and challenge state and pandemic violence.

McIlwaine reflects on two different but interconnected projects in her paper, spanning a range of artistic media. In the first, she discusses a verbatim theatre play written by a playwright, Gaël Le Cornec, based on McIlwaine’s research with Brazilian migrant women living in London. The second is a community drama project developed with Migrants in Action with 14 Brazilian migrant women survivors who reinterpret the same body of research. The collaborative piece included poetry, storytelling, music, art, and film-making, which were combined to create an audio-visual installation and accompanying performance. These two different approaches to arts-based research in McIlwaine’s paper lead us to define the third core element of migration-violence creative pathways. This third element refers to the range of knowledge production approaches and practices that may be used to carry out arts-based research. While overlapping and not mutually exclusive, these relate to whether the work aims to be participatory and to work with research participants/migrants or whether it employs a curatorial perspective where an artist/migrant interprets the phenomenon or existing research. The former accounts for a large proportion of work with migrants and on violence (O’Neill Citation2011). Overall, participatory artistic approaches are often assumed to be more ethical than those which represent, and potentially misrepresent, migrants without including them in the creative process (Nunn Citation2022). Yet, curatorial perspectives are also important, and the ethical implications of how migrants may be represented through such processes merits more attention (Blomfield and Caroline Citation2018; McIlwaine Citation2024). There are often overlaps between the approaches. Curation can, for example, be driven by research participants (Mainsah and Rafiki Citation2023). Likewise, in some cases, participatory projects may draw on existing research that is then interpreted through creative engagements, sometimes as a form of dissemination but also as a process to further understand the issue being researched (McIlwaine et al. Citation2022a). Participatory approaches may also involve methodological tools that allow participants to share their lived experiences in safe spaces and to drive the research process (Erel, Reynolds, and Kaptani Citation2017).

In varying ways, all of the contributors to this special issue worked in a collaborative and participatory manner with migrants or their family members. As noted above, Lopes Heimer, Ryburn, Sheringham, Taylor and Duffy-Syedi, and McIlwaine all carried out workshops with groups of between 10 to twenty migrants and refugees. Gideon also worked directly with Chilean exiles in the UK to curate together the exhibition of their craft objects and to produce the documentary film for which some of them were interviewed. Lines and Las RestaurAmoras engage in the poignant work of collaborating with the families of murdered migrant women to ensure that the murals they create reflect the families’ wishes and memories. All of our contributors reflect on the complex and nuanced ethics involved in each of these different approaches to knowledge production, the creative process, and the sharing of artistic creations. Such reflection on the ethical dimensions of arts-based research is fundamental to work that aims to develop decolonial, feminist, and critical perspectives that reveals the underlying intersectional power hierarchies that impact the lives of migrants, especially those from colonised contexts.

The fourth element constitutive of migration-violence creative pathways relates to the complex roles of researchers, artists and participants, all or none of whom may be migrants. As noted above, artists may fully drive the creative engagement or collaborate with researchers and/or participants. The academic researcher may lead the artistic work, or take a back seat, while others may become managers, facilitators, or what the artworld would more likely refer to as producers. They will often liaise with arts organisations who may be facilitating the creative work as well as influencing any research issues that may arise. Researchers may also become what theatre practitioners refer to as ‘dramaturgs’ who supervise scripts, have an overview of the research and creative processes and who can also act as constructive critics (McIlwaine Citation2024; McIlwaine et al. Citation2024). The interactions among these groups can be productive but also fraught with tensions and contradictions (Blomfield and Caroline Citation2018; Johnstone and Pratt Citation2020). Our contributors reflect on their roles and these relationships, highlighting the close affective bonds that may emerge amongst teams and participants as well as the challenges that may arise. Drawing on the work of feminist geographers Gokariksel et al. (Citation2021), Ryburn (Citation2024) suggests that it can be helpful to reflexively consider the embodied sensations of ‘discomfort’ that may arise as the relational elements of an arts-based research project are negotiated. Paying attention to this sensation, which is often spoken of by feminist researchers but rarely written about (Gokariksel et al. Citation2021, 7), can help guide us towards more inclusive and ethical research.

Depending on how the four elements outlined feed into the migration-violence creative pathway developed in a given project, different outcomes can emerge. In addition to the ethical, feminist, decolonising and other commitments mentioned above, arts-based approaches have long been associated with engendering transformation, resistance and belonging among those traditionally marginalised and silenced. They can challenge erroneous representations of migrants and allow them to re-signify their own narratives and to confront power asymmetries. This may be linked with providing therapeutic opportunities for research participants or may lead to changes in thinking among the general public or policy impacts (Coemans and Hannes Citation2017; Jeffery et al. Citation2019). Embodied initiatives play an important role in effectively communicating and advocating around sensitive issues such as violence and exploitation among migrants to multiple and diverse audiences in ways that can avoid reproducing violence, reflecting O'Neill’s (Citation2009) concept of ethno-mimesis. These can therefore lead to enhanced public engagement, policy change and/or wider societal transformations as well as improved well-being among research participants (if the artistic work was therapeutic in nature). Yet this also raises the importance of evaluating the artistic work and thinking through how it has influenced all the actors involved as well as the multiple audiences including policy-makers (). Among others, this might be through participatory evaluation with participants, feedback sessions with audiences, and/or working with formal evaluators. However, notable drawbacks to arts-based research are increasingly being recognised, again identified above and summarised as: having limited transformative and empowerment potential; promising a panacea for solving problems; claiming the creation of equitable research relationships that never materialise; and communicating damaging representations that focus on suffering and deny agency.

Whilst keenly aware of these potential pitfalls, we and our contributors remain committed to further developing migration-violence creative pathways that promote more ethical, collaborative, and, hopefully, transformative research. There are many overlaps but also differences in what this looks like for each of us. Gideon stresses the importance of Crafting Resistance in relation to looking after difficult knowledge (see Andrä et al. Citation2020), creating space for counter memories, and enabling difficult but healing intergenerational conversations. For Lines, public memorialisation through the murals of victims of feminicide painted by Las RestaurAmoras has similar but more immediate political intentionsss it in drawing attention to the violence in migrant women's lives and the need to address it in a context where top-down discourse and practices ignores it.

Lopes Heimer reflects upon the potentials inherent within collaborative art-research from a decolonial epistemic perspective, while Ryburn considers how feminist epistemologies invite us to focus on embodiment, the sensory, and the visceral, thereby pushing us creatively towards greater representation of lived experience. For Sheringham, Taylor and Duffy-Syedi, despite the many challenges faced, the workshops run by Stories & Supper and Phosphorous Theatre during the pandemic generated a radical and immediate hope through working together in a creative space. Finally, reflecting McIlwaine's work, we suggest, across all of our contributors’ projects, that our migration-violence creative pathways have led us to aim towards a ‘shared feminist translocational vision' that traverses borders, disciplinary and epistemological boundaries, and is differentiated by language, place, audience and experiences of gendered violence.

Conclusion: agenda for future creative research on migration and violence

Our outline of the creative migration-violence pathways raises a host of issues that need to be addressed in any agenda for future research. Without rehearsing the points discussed already, we reflect on how future enquiry around migration-violence connections might most productively and critically engage with arts-based approaches. At the outset, it is worth making the point that academic writing about these creative engagements through text is potentially paradoxical given their embodied, visual and performative nature. Yet, Hawkins (Citation2021, 1715) notes in relation to geographers that they are increasingly not just writing about their creative collaborations but are also using text as ‘their creative medium of choice’ which may include poetry, pamphlets, zines, comics, play scripts among others. Furthermore, many journals now provide special sections on creative outputs and practices (Hawkins Citation2020). Within migration studies, for example, Migration and Society has a ‘Creative Encounters’ section (see a poem by Qasmiyeh Citation2022), and also encourages submissions that include creative knowledge production (see Ramírez Citation2023).

Yet the strictures of academic life generally make working with the arts complicated and difficult, at least within the social sciences and within the confines of what McLean (Citation2022, 312) calls ‘the corporatized, metric-oriented, hetero-patriarchal, white supremacist, and colonial university sector’ in the UK. The current popularity of arts-based and especially participatory research is being positively embraced by many universities through providing support, space and funding. Yet, this may also reflect a more cynical move by universities to represent themselves as progressive and publicly engaged institutions as part of wider corporatist efforts. It may also be part of research impact and knowledge exchange initiatives that have arguably commodified research that extends beyond the academy in the UK and beyond (Pain Citation2014). These can reify and essentialise collaborative research with artists, arts organisations and community groups using creative methods in ways that reinforce intersectional and colonial inequalities (McLean and de Leeuw Citation2020). However, if conducted with care and full cognisance of the ethical dimensions of what can and cannot be achieved, arts-based research can help build important collaborations that speak to new audiences, reveal underlying neoliberal and colonialist power hierarchies and provide spaces for those often excluded from academic spaces (McLean Citation2022).

These issues are particularly significant for research on the migration-violence nexus in light of the enduring focus on migrants, refugees and asylum-seekers from countries from the so-called global South or Majority World, many of whom have insecure immigration status and who are regularly demonised by the hostile societies they move to. Future research in this field that claims to be transformative, collaborative, non-extractive, anti-racist, decolonial, feminist and participatory must guard against falling into the trap of over-enthusiastic and potentially false claims. Both researchers and artists working with migrants are increasingly becoming more circumspect and careful around how to engage ethically with migrants in contexts of violence. In relation to their ‘encounters in migratory spaces of violence’ through visual methods in Calais and Dunkirk, France, El Qadim et al. (Citation2021, 1625) note the need to discuss ‘feelings of unease, doubt, shock and failure in order to conduct this kind of research without becoming paralysed by the idea that we might be doing more harm than good’. This increasing reflexivity has led to the production of guidelines for ethical research that we refer to below.

One of the most frequently identified issues in relation to arts-based approaches for understanding experiences of violence among migrants is the need to represent them ethically and effectively (see above). Such representations run through our migration-violence creative pathways. For artists working with migrants, there is an imperative to ensure honesty to the migrants they depict and where relevant to the research process (Johnstone and Pratt Citation2020). There are dangers that integrity is compromised in favour of dramatic and/or artistic effect (McIlwaine Citation2024), and related to this, that certain depictions will disempower, ‘other’ and damage the migrants being portrayed which may influence public understanding and political decision-making (Lenette and Miskovic Citation2018). A major challenge, therefore, is representing migrants living in conditions of violence in nuanced ways that avoids essentialist tropes as well as those that focus only on suffering or on unattainable agency (Blomfield and Lenette Citation2018: Ryburn Citation2024). While visibilising the lives of migrants in these contexts through artistic representations may improve their situations, it may place them at further risk (El Qadim et al., Citation2021). As a result, artists must take care to avoid any form of re-traumatisation and to develop counter-narratives that challenge insidious stereotypes (Nunn Citation2010). This also means avoiding what El Qadim (Citation2020) calls ‘border voyeurism’ that fetishises trauma and suffering through a lens of ‘othering’.

Collaboration is key for artists and researchers in creating ethical creative work that evades such problems. While this may be with individual migrants, increasingly it is through migrant organisations who can act as gatekeepers and facilitators. As discussed above, collaborative, co-produced, and co-designed approaches are central to more participatory arts-based approaches and use of creative methods for working with migrants (O'Neill et al. Citation2019). These may be developed by researchers working with combinations of organisations, artists and research participants. But seeking out a migrant organisation does not inherently ensure ethical and participatory approaches nor appropriate representations of migrants experiencing violence. Guidelines produced by RISE (Refugees, Survivors and Ex-detainees), an organisation run ‘by and for’ these groups have outlined ‘10 Things You Need To Consider If You Are An Artist – Not Of The Refugee And Asylum Seeker Community – Looking To Work With Our Community’ authored by director Tania Cañas in 2015 (see Blomfield and Lenette Citation2018; El Qadim Citation2020). Among others, this aims to challenge extractive research through the entreaty to focus on ‘process not product’, to ‘critically interrogate your intention’, to know the difference between presentation and representation, and to acknowledge that participation is not always ‘progressive and empowering’. The need for researcher reflexivity is also key, framed as ‘realise your own privilege’ and bias (see also McLean Citation2022), along with doing background research, recognising that migrants have complex and nuanced experiences, and that artwork is ‘inherently political’.Footnote1 Collaboration should therefore be meaningful for everyone involved but especially migrants who should also be provided with genuine informed consent and anonymity as suits them. Researchers and artists need to be aware of the wider political contestations around migration so as to avoid the pitfalls noted above (Blomfield and Lenette Citation2018).

Related to this is that researchers need to develop sustainable relationships of trust with both migrant organisations and research participants. While this might not always align with the funding demands of universities and research funders, ethical commitments demand that longer-term collaborations are maintained. A host of practical issues must also be resolved. Essential within this is the payment of artists, organisations and research participants (El Qadim Citation2020). Indeed, too often it emerges that participants are not paid and/or are not provided with a copy of the artistic output in return for their participation. We suggest that this is not appropriate. Participants should be paid a fair fee, preferably according to local arts council fee structures. Also important is authorship which needs to be agreed in advance. While it may be the case that artists and organisations are not interested in being included in academic publications, accessibly written reports or an exhibition of some kind that reflects the project can provide recognition. Even then, it is important that everyone involved agrees with what appears in the public sphere.

While many of these points are generic in terms of thinking through different aspects of our migration-violence creative pathways that require choices to be made about the type of artistic media, as well as the artists, migrants, and migrant groups to work with or not, together with the knowledge production approach, there are also several substantive research areas that also require more attention. While this special issue covers a wide spectrum of substantive issues and geographies around the connections between migration and violence, there are others that are excluded here or which need more research. These might include: migration flows within the South; transit migration; and internal displacement, especially due to climate change. Whilst particularly ethically complex, arts-based approaches can also be a sensitive and appropriate way to work with highly vulnerable groups such as, inter alia, child migrants, unaccompanied minors, those with non-conforming sexualities and gender identities, and survivors of trafficking.

As we believe the contributions in this special issue show, when approached with careful consideration, arts-based research has the potential to reveal sensitive, nuanced understandings of the multifarious and disturbing interrelations between migration and violence. Through our engagements with contributors and reflections on our own work, we have taken steps in this Introduction to outline what we term ‘migration-violence creative pathways’. We use this framing to advance conceptual and methodological thinking about arts-based research on migration and violence. We invite arts-based researchers to consider how the four key elements of: research area; artistic media; knowledge production approach and practices; and the roles played by project team members, feed into the creative pathway ultimately followed and the outcomes to which it might lead. As reflected in the powerful work of our contributors, we consider that, when thoughtfully and reflexively carried out, arts-based research projects on migration and violence can have transformative outcomes for participants, team members, and the audiences with whom the project engages. In a global environment of stigma, discrimination, exploitation, hostility and direct physical attacks towards migrants, this could not be more necessary.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the authors included in this special issue for their contributions. We are also grateful to Renata Peppl for comments on an earlier draft as well as those from an anonymous referee, all of which have improved the final paper. Our thanks also to Paul Statham and Nik Ostrand for supporting us in reaching the final stages. Cathy is very grateful for the support of the Visual and Embodied Methodologies (VEM) network at King’s College London (and especially Jelke Boesten, Rachel Kerr and Suzanne Hall) for providing space and creative energy to think through many of the issues discussed here.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 https://aktiontanz.de/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/RISE-statement-on-working-with-the-refugee-community.pdf (accessed 31 October 2023).

References

- Ahmed, S. 2001. Strange Encounters Embodied Others in Post-Coloniality. London: Routledge.

- Andrä, C., B. Bliesemann de Guevara, L. Cole, and D. House. 2020. “Knowing Through Needlework: Curating the Difficult Knowledge of Conflict Textiles.” Critical Military Studies 6 (3-4): 341–359. https://doi.org/10.1080/23337486.2019.1692566.

- Bagnoli, A. 2009. “Beyond the Standard Interview: The use of Graphic Elicitation and Arts-Based Methods.” Qualitative Research 9 (5): 547–570. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794109343625.

- Barone, T., and E. Eisner. 2012. Arts Based Research. London: Sage.

- Barry, K., J. Southern, T. Baxter, S. Blondin, C. Booker, J. Bowstead, C. Butler, et al. 2023. “An Agenda for Creative Practice in the new Mobilities Paradigm.” Mobilities 18 (3): 349–373. https://doi.org/10.1080/17450101.2022.2136996.

- Bastia, T., K. Datta, K. Hujo, N. Piper, and M. Walsham. 2023. “Reflections on Intersectionality: A Journey Through the Worlds of Migration Research, Policy and Advocacy.” Gender, Place & Culture 30 (3): 460–483. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2022.2126826.

- Biglin, J. 2022. “Photovoice as an Unfamiliar act of Citizenship: Everyday Belonging, Place-Making and Political Subjectivity.” Citizenship Studies 26 (3): 263–286. https://doi.org/10.1080/13621025.2022.2036103.

- Bird, J. 2018. “Art Therapy, Arts-Based Research and Transitional Stories of Domestic Violence and Abuse.” International Journal of Art Therapy 23 (1): 14–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/17454832.2017.1317004.

- Björgvinsson, E., N. De Genova, M. Keshavarz, and T. Wulia. 2020. “Art and Migration.” Parse 10: 1–8.

- Blomfield, I., and C. Lenette. 2018. “Artistic Representations of Refugees: What Is the Role of the Artist?” Journal of Intercultural Studies 39 (3): 322–338. https://doi.org/10.1080/07256868.2018.1459517.

- Boesten, J., and H. Scanlon. 2021. Gender, Transitional Justice and Memorial Arts. eds. London: Routledge.

- Bowstead, J. C. 2017. “Women on the Move: Theorising the Geographies of Domestic Violence Journeys in England.” Gender, Place & Culture 24 (1): 108–121. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2016.1251396.

- Brickell, K. 2024. “Slow Violence, Over-Indebtedness, and the Politics of (in)Visibility: Stories and Creative Practices in Pandemic Times.” Political Geography 110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2023.102842.

- Brickell, K., and A. Maddrell. 2016. “Geographical Frontiers of Gendered Violence.” Dialogues in Human Geography 6 (2): 170–172. https://doi.org/10.1177/2043820616653291.

- Cahill, C., and R. Pain. 2019. “Representing Slow Violence and Resistance.” Acme 18 (5): 1054–1065.

- Carbado, D. W., K. W. Crenshaw, V. M. Mays, and B. Tomlinson. 2013. “Intersectionality.” Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race 10 (2): 303–312. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1742058X13000349.

- Carvajal, A. 2020. Exploring the Diverse Range of Visual Embodied Methods Across Social Science - a Useful and Insightful Overview for Research, Learnings and Considerations. London: Visual and Embodied Methodologies Network. https://www.kcl.ac.uk/sspp/assets/visual-embodied-methodologies-network/vem-2-espinoza-carvajal-abr-literature-review-2020.pdf.

- Castañeda Salgado, M. P. 2016. “Feminicide in Mexico: An Approach Through Academic, Activist and Artistic Work.” Current Sociology 64 (7): 1054–1070. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392116637894.

- Chilton, G., and P. Leavy. 2014. “Arts-based Research Practice.” In In The Oxford Handbook of Qualitative Research, edited by Patricia Leavy, 403–422. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Christensen, M. C. 2019. “Using Photovoice to Address Gender-Based Violence: A Qualitative Systematic Review.” Trauma, Violence, & Abuse 20 (4): 484–497. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838017717746.

- Coemans, A., and K. Hannes. 2017. “Researchers Under the Spell of the Arts: Two Decades of Using Arts-Based Methods in Community-Based Inquiry with Vulnerable Populations.” Educational Research Review 22: 34–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2017.08.003.

- Collins, F. L. 2022. “Geographies of Migration II: Decolonising Migration Studies.” Progress in Human Geography 46 (5): 1241–1251. https://doi.org/10.1177/03091325221100826.

- Cooke, W., and U. Kothari. 2001. Participation: The new Tyranny? London: Zed Books.

- Corcoran, L., and L. Annette. 2018. “Exploring the Impact of off the Beaten Path: Violence, Women, and art.” Women's Studies International Forum 67: 72–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2018.01.008.

- de Leeuw, S., and H. Hawkins. 2017. “Critical Geographies and Geography’s Creative re/Turn: Poetics and Practices for new Disciplinary Spaces.” Gender, Place & Culture 24 (3): 303–324. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2017.1314947.

- Desille, A., and K. Nikielska-Sekula. 2021. Visual Methodology in Migration Studies. Springer: Gewerbestrasse.

- El Qadim, N. 2020. “From “Border Spectacle” to “Border Voyeurism”? Questions on Fostering Ethical Engagement with Migration.” Parse 10: 285–292.

- El Qadim, N., B. İşleyen, L. Ansems de Vries, S. S. Hansen, S. Karadağ, D. Lisle, and D. Simonneau. 2021. “(Im)Moral Borders in Practice.” Geopolitics 26 (5): 1608–1638. https://doi.org/10.1080/14650045.2020.1747902.

- Erel, U., E. Kaptani, M. O’Neill, and T. Reynolds. 2022. “PAR: Resistance to Racist Migration Policies in the UK.” In Transformative Research and Higher Education, edited by Azril Bacal Roij, 93–106. Leeds: Emerald.

- Erel, U., T. Reynolds, and E. Kaptani. 2017. “Participatory Theatre for Transformative Social Research.” Qualitative Research 17 (3): 302–312. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794117696029.

- Fairey, T., E. Cubillos, and M. Muñoz. 2023. “Photography and Everyday Peacebuilding.” Peacebuilding.

- Fairey, T., and R. Kerr. 2020. “What Works? Creative Approaches to Transitional Justice in Bosnia and Herzegovina.” International Journal of Transitional Justice 14 (1): 142–164. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijtj/ijz031.

- Faria, C. 2017. “Towards a Countertopography of Intimate war: Contouring Violence and Resistance in a South Sudanese Diaspora.” Gender, Place & Culture 24 (4): 575–593. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2017.1314941.

- Fiddian-Qasmiyeh, E. 2020. “Introduction.” Migration and Society 3 (1): 1–18. https://doi.org/10.3167/arms.2020.030102.

- Fluri, J., and A. Piedalue. 2017. “Embodying Violence: Critical Geographies of Gender, Race, and Culture.” Gender, Place & Culture 24 (4): 534–544. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2017.1329185.

- Flynn, D. 2022. “Sex Work and the City: Liminal Lives in Chika Unigwe’s On Black Sisters’ Street.” Crossings: Journal of Migration & Culture 13 (1): 47–60. https://doi.org/10.1386/cjmc_00055_1.

- Forcer, S., H. Shutt, L. S. Martin, M.-H. Coetzee, A. F. Ibrahim, and S. Fitzmaurice. 2022. “Embracing Aporia: Exploring Arts-Based Methods, Pain, “Playfulness,” and Improvisation in Research on Gender and Social Violence.” Global Studies Quarterly 2 (4): ksac061. https://doi.org/10.1093/isagsq/ksac061.

- Frohmann, L. 2005. “The Framing Safety Project.” Violence Against Women 11 (11): 1396–1419. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801205280271.

- Garelli, G., and M. Tazzioli. 2013. “Challenging the Discipline of Migration: Militant Research in Migration Studies, an Introduction.” Postcolonial Studies 16 (3): 245–249. https://doi.org/10.1080/13688790.2013.850041.

- Gideon, J. 2024. “Crafting Arts-Based Stories of Exile, Resistance and Trauma Among Chileans in the UK.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2024.2345994.

- Gokariksel, B., M. Hawkins, C. Neubert, and S. Smith. 2021. Feminist Geography Unbound. eds. Morgantown: West Virginia University Press.

- Grosfoguel, R., L. Oso Laura, and A. Christou. 2015. “‘Racism’, Intersectionality and Migration Studies: Framing Some Theoretical Reflections.” Identities 22 (6): 635–652. https://doi.org/10.1080/1070289X.2014.950974.

- Grosz, E. 1994. Volatile Bodies. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

- Gubar, Susan. 2000. Critical Condition: Feminism at the Turn of the Century. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Guruge, S., M. Hynie, Y. Shakya, A. Akbari, S. Htoo, and S. Abiyo. 2015. “Refugee Youth and Migration: Using Arts-Informed Research to Understand Changes in Their Roles and Responsibilities.” Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research 16 (3): 1–36.

- Haraway, D. 1988. “Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective.” Feminist Studies 14 (3): 575–599. https://doi.org/10.2307/3178066.

- Harman, S. 2016. “Film as Research Method in African Politics and International Relations: Reading and Writing HIV/AIDS in Tanzania.” African Affairs 115 (461): 733–750. https://doi.org/10.1093/afraf/adw057.

- Harman, S. 2018. “Making the Invisible Visible in International Relations: Film, co-Produced Research and Transnational Feminism.” European Journal of International Relations 24 (4): 791–813. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066117741353.

- Harman, S. 2019. Seeing Politics. Montreal: McGill Queens University Press.

- Hawkins, H. 2013. “Geography and art. An Expanding Field.” Progress in Human Geography 37 (1): 52–71. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132512442865.

- Hawkins, H. 2019. “Geography’s Creative (re)Turn: Toward a Critical Framework.” Progress in Human Geography 43 (6): 963–984. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132518804341.

- Hawkins, Ht. 2020. Geography, Art, Research: Artistic Research in the GeoHumanities. London: Routledge.

- Hawkins, H. 2021. “Cultural Geography I: Mediums.” Progress in Human Geography 45 (6): 1709–1720. https://doi.org/10.1177/03091325211000827.

- Jeffery, L., M. Palladino, R. Rotter, and A. Woolley. 2019. “Creative Engagement with Migration.” Crossings: Journal of Migration & Culture 10 (1): 3–17. https://doi.org/10.1386/cjmc.10.1.3_1.

- Johnstone, C., and G. Pratt. 2020. Migration in Performance. London: Routledge.

- Kaptani, E., U. Erel, M. O'Neill, and T. Reynolds. 2021. “Methodological Innovation in Research: Participatory Theater with Migrant Families on Conflicts and Transformations Over the Politics of Belonging.” Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies 19 (1): 68–81. https://doi.org/10.1080/15562948.2020.1843748.

- Kaptani, E., and N. Yuval-Davis. 2008. “Participatory Theatre as a Research Methodology: Identity, Performance and Social Action among Refugees.” Sociological Research Online 13 (5): 1–12. https://doi.org/10.5153/sro.1789.

- Kara, H. 2015. Creative Research Methods in the Social Science. Bristol: Policy Press.

- Kaur, R. 2017. “Mediating Rape: The Nirbhaya Effect in the Creative and Digital Arts.” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 42 (4): 945–976. https://doi.org/10.1086/690920.

- Keifer-Boyd, K. 2011. “Arts-based Research as Social Justice Activism.” International Review of Qualitative Research 4 (1): 3–19. https://doi.org/10.1525/irqr.2011.4.1.3.

- Kelly, L. 1988. Surviving Sexual Violence. Oxford: Polity Press.

- Kinna, R., and G. Whiteley. 2020. Cultures of Violence. eds. London: Routledge.

- Klassen, L. 2020. “Figurations Following the Ethical Turn.” Parse 10: 181–192.

- Kukkonen, T., and A. Cooper. 2019. “An Arts-Based Knowledge Translation (ABKT) Planning Framework for Researchers.” Evidence & Policy 15 (2): 293–311. https://doi.org/10.1332/174426417X15006249072134.

- Leavy, P. 2014. Social Research and the Creative Arts. New York: Guilford Publications.

- Leavy, P. 2017. Research Design: Quantitative, Qualitative, Mixed Methods, Arts-Based, and Community-Based Participatory Research Approaches. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Lelliott, K. L. 2020. “A More Than Four-Hundred-Year-Long Event.” Parse 10: 9–17.

- Lenette, C. 2019. Arts-based Methods in Refugee Research. Singapore: Springer: Springer Nature Singapore.

- Lenette, C. 2022. “Cultural Safety in Participatory Arts-Based Research: How Can We Do Better?” Journal of Participatory Research Methods 3 (1): 1–16.

- Lenette, C., and N. Miskovic. 2018. “‘Some Viewers may Find the Following Images Disturbing’: Visual Representations of Refugee Deaths at Border Crossings.” Crime, Media, Culture: An International Journal 14 (1): 111–120. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741659016672716.

- Levitt, P., and B. N. Jaworsky. 2007. “Transnational Migration Studies: Past Developments and Future Trends.” Annual Review of Sociology 33 (1): 129–156. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.33.040406.131816.

- Lines, J. 2024. “Portraits of Feminicide: Mural Painting as Protection among Migrant Women in Quintana Roo, Mexico.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2024.2345996.

- Lopes Heimer, R. D. V. 2024. “Embodying Intimate Border Violence: Collaborative Art-Research as Multipliers of Latin American Migrant Women’s Affects.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2024.2345991.

- Mainsah, H., and N. Rafiki. 2023. “Methodological Reflections on Curating an Artistic Event with African Youth in a Norwegian City.” Qualitative Research 23 (5): 1283–1300. https://doi.org/10.1177/14687941221096599.

- Malik, S., C. Mahn, M. Pierse, and B. Rogaly. 2020. Creativity and Resistance in a Hostile World. eds. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Marnell, J., E. Oliveira, and G. Hoosain Khan. 2021. “‘It's About Being Safe and Free to be who you Are’: Exploring the Lived Experiences of Queer Migrants, Refugees and Asylum Seekers in South Africa.” Sexualities 24 (1–2): 86–110. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363460719893617.

- Martin, P. 2023. “Poner la Cuerpa: The Body as a Site of Reproductive Rights Activism in Peru.” Bulletin of Latin American Research 42 (1): 21–35. https://doi.org/10.1111/blar.13421.

- Martiniello, M. 2022. “Researching Arts, Culture, Migration and Change.” Comparative Migration Studies 10 (7): 1–10.

- Mayblin, L., and J. Turner. 2020. Migration Studies and Colonialism. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

- Mayblin, L., M. Wake, and M. Kazemi. 2020. “Necropolitics and the Slow Violence of the Everyday: Asylum Seeker Welfare in the Postcolonial Present.” Sociology 54 (1): 107–123. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038519862124.

- McIlwaine, C. 2010. “Migrant Machismos: Exploring Gender Ideologies and Practices among Latin American Migrants in London from a Multi-Scalar Perspective.” Gender, Place & Culture 17 (3): 281–300. https://doi.org/10.1080/09663691003737579.

- McIlwaine, C. 2012. “Constructing Transnational Social Spaces among Latin American Migrants in Europe: Perspectives from the UK.” Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 5 (2): 289–304. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsr041.

- McIlwaine, C. 2024. “Creative Translation Pathways for Exploring Gendered Violence Against Brazilian Migrant Women Through a Feminist Translocational Lens.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2024.2345990.

- McIlwaine, C., N. Coelho Resende, M. Rizzini Ansari, J. Gonçalves Leal, F. Vieira, A. Dionisio, and P. Heritage. 2022. Digital Storytelling among Women Artists Resisting Violence in Mare, Rio de Janeiro. London: King's College London.

- McIlwaine, C., and Y. Evans. 2020. “Urban Violence Against Women and Girls (VAWG) in Transnational Perspective: Reflections from Brazilian Women in London.” International Development Planning Review 42 (1): 93–112. https://doi.org/10.3828/idpr.2018.31.

- McIlwaine, C., and Y. Evans. 2023. “Navigating Migrant Infrastructure and Gendered Infrastructural Violence: Reflections from Brazilian Women in London.” Gender, Place & Culture 30 (3): 395–417. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2022.2073335.

- McIlwaine, C., Y. Evans, P. Heritage, M. Krenzinger, and E. Sousa Silva. 2024. Gendered Urban Violence among Brazilians. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- McIlwaine, C., N. Sreenan, C. Cal Angrisani, R. Peppl, and I. M. Gomes. 2022a. We Still Fight in the Dark: Evaluation Findings, Reflections, and Lessons for Policy & Practice. London: King's College London.

- McLean, H. 2022. “Creative Arts-Based Geographies.” ACME: An International Journal for Critical Geographies 21 (3): 311–326. https://acme-journal.org/index.php/acme/article/view/2195.

- McLean, H., and S. de Leeuw. 2020. “Enacting Radical Change.” In Handbook on the Geographies of Creativity, edited by A. de Dios, and L. Kong, 266–281. Cheltenham: Elgar.

- Menjívar, C., and S. Drysdale Walsh. 2019. “Gender, Violence and Migration.” In Handbook on Critical Geographies of Migration, edited by K. Mitchell, R. Jones, and J. L. Fluri, 45–57. Cheltenham: Elgar.

- Mijić, A., and M. Parzer. 2022. “The Art of Arriving: A New Methodological Approach to Reframing “Refugee Integration”.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 21: 160940692110663–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/16094069211066374.

- Miled, N. 2020. “Can the Displaced Speak? Muslim Refugee Girls Negotiating Identity, Home and Belonging Through Photovoice.” Women's Studies International Forum 81: 102381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2020.102381.

- Miyamoto, Bénédicte, and Marie Ruiz. 2021. Art and Migration: Revisioning the Borders of Community. eds. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Motturi, A. 2020. “When You Are a Writer.” Parse 10: 126–130.

- Mould, O. 2020. Against Creativity. London: Verso.

- Mountz, A. 2017. “Island Detention: Affective Eruption as Trauma’s Disruption.” Emotion, Space and Society 24: 74–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emospa.2017.02.006.

- Moura, T., and L. Cerdeira. 2021. “Re-Thinking Gender, Artivism and Choices. Cultures of Equality Emerging from Urban Peripheries.” Frontiers in Sociology 6: 637564. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsoc.2021.637564.

- Nunn, C. 2010. “Spaces to Speak: Challenging Representations of Sudanese-Australians.” Journal of Intercultural Studies 31 (2): 183–198. https://doi.org/10.1080/07256861003606366.

- Nunn, C. 2017. “Translations-Generations: Representing and Producing Migration Generations Through Arts-Based Research.” Journal of Intercultural Studies 38 (1): 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/07256868.2017.1269059.

- Nunn, C. 2022. “The Participatory Arts-Based Research Project as an Exceptional Sphere of Belonging.” Qualitative Research 22 (2): 251–268. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794120980971.

- Oliveira, Elsa. 2019. “The Personal is Political: A Feminist Reflection on a Journey Into Participatory Arts-Based Research with sex Worker Migrants in South Africa.” Gender & Development 27 (3): 523–540. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552074.2019.1664047.

- Oliveira, E., and J. Vearey. 2020. “The Seductive Nature of Participatory Research: Reflecting on More Than a Decade of Work with Marginalized Migrants in South Africa.” Migration Letters 17 (2): 219–228. https://doi.org/10.33182/ml.v17i2.785.

- O'Neill, M. 2009. “Making Connections: Ethno-Mimesis, Migration and Diaspora.” Psychoanalysis, Culture & Society 14: 289–302. https://doi.org/10.1057/pcs.2009.5.

- O’Neill, M. 2011. “Participatory Methods and Critical Models: Arts, Migration and Diaspora.” Crossings: Journal of Migration & Culture 2 (1): 13–37. https://doi.org/10.1386/cjmc.2.13_1.

- O'Neill, M., U. Erel, E. Kaptani, and T. Reynolds. 2019. “Borders, Risk and Belonging: Challenges for Arts-Based Research in Understanding the Lives of Women Asylum Seekers and Migrants ‘at the Borders of Humanity’.” Crossings: Journal of Migration & Culture 10 (1): 129–147. https://doi.org/10.1386/cjmc.10.1.129_1.

- Pain, R. 2014. “Impact: Striking a Blow or Walking Together?” ACME: An International E-Journal for Critical Geographies 13 (1): 19–23.

- Pain, R., and C. Cahill. 2022. “Critical Political Geographies of Slow Violence and Resistance.” Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space 40 (2): 359–372. https://doi.org/10.1177/23996544221085753.

- Pain, R., B. Heslop, and G. Heslop. 2019. “Slow Violence and the Representational Politics of Song.” ACME: An International Journal for Critical Geographies 18 (5): 1100–1111.