ABSTRACT

This paper argues for the decolonial feminist potential of multi-layered arts-research collaborations for critical research committed to advancing migrant justice. It reflects on the art-research collaborative project, ‘stitching voices, stitching bodies’, investigating the gendered, racialised, colonial and geopolitical dynamics of violence and resistance of Latin American migrant women. Collaborators included the author and visual artist Nina Franco, twenty anonymous Latin American survivors of violence, three Latin American women activists and a filmmaker, a British-Caribbean sound engineer and an Irish-Caribbean video editor. Through our art-research methodological engagements, the relationship between the researcher, artists and participants was significantly altered as we alternated between and simultaneously occupied those positions. Exchanging and complementing our skills and sensibilities, we tried new ways of working and overlapped various layers of expression to collectively produce knowledge that enhanced understandings of and multiplied affects concerning intimate border violence. Through our art, we were able to envision, explore and represent intimate border violence, coloniality and resistance to these in audio-visual and visceral ways that grasped and multiplied embodied affects not only for research participants and collaborators but also audiences.

Introduction

This paper reflects on the decolonial epistemic potentialities of collaborative art-research by drawing on experiences from the project, ‘Stitching Voices, Stitching Bodies’, investigating the gendered, racialised, colonial and geopolitical dynamics of violence and resistance of Latin American migrant women. Collaborators included me and the visual artist Nina Franco, twenty anonymous Latin American women survivors of violence, and five activists and artists from Latin America and the British and Irish diaspora. Through our art-research methodological engagements, we altered the traditional roles of researchers, artists and participants. The lines between these positions became more blurred as we alternated between those roles and sometimes simultaneously occupied them. As artists and researchers, we aimed to include our whole selves within the various stages of the collaboration, enquiring about and registering how we have experienced and been affected by its processes and encounters. We were able to envision, explore and represent what I have termed elsewhere as ‘intimate border violence’ (Lopes Heimer Citation2022b) in audio-visual and visceral ways that grasped and multiplied embodied affects on research participants, collaborators, and, to some extent, also audiences. Working with bodily, artistic, verbal and non-verbal means of expression enabled us to overcome the limits of traditional research methods whilst giving equal weight to both process and product, ensuring these were engaging and accessible. Exchanging and complementing our skills and sensibilities, we tried new ways of working and overlapped various layers of expression to collectively produce knowledge that enhanced our understanding of intimate border violence.

Despite not having direct colonial links to England, Latin Americans are one of the country's largest and fastest-growing non-EU migrant populations (McIlwaine and Bunge Citation2016; Citation2019; McIlwaine, Camilo Cock, and Linneker Citation2011). They are, nonetheless, impacted by significant and intersecting structural socio-economic disadvantages and migration histories (Carlisle Citation2006; McIlwaine and Bunge Citation2016; Turcatti and Vargas-Silva Citation2022). The Latin American community is a highly heterogenous group comprising multiple nationalities, ethnicities, languages and class positions (McIlwaine and Bunge Citation2016; Román-Velázquez and Retis Citation2021). Informed by their colonial histories and intersecting identities, Latin American women’s experiences of (intimate) border violence differ from other migrant groups. Yet, their experiences help uncover the underpinning multi-scalar dynamics of the British border regime, which may similarly impact other migrant women (Lopes Heimer Citation2022b).

More specifically, intimate border violence is a term I conceptualised as a form of state-sponsored intimate violence that directly stems from the state border violence of the British immigration system and its necropolitical operating logic (El-Enany Citation2020; Mbembe Citation2003; Wright Citation2011). Building on and expanding feminist geopolitics and critical border scholarship, I revealed how intimate border violence is manifested not only at and through the national and transnational scales but also at and through the scales of the body and home, enacted by abusive men through intimate bordering practices to exert power and control against their migrant partners (Cassidy Citation2019; Griffiths and Yeo Citation2021; Hyndman Citation2001; Citation2012; Smith and Pain Citation2016; Yuval-Davis, Wemyss, and Cassidy Citation2019; Citation2018). As I identify throughout this paper, enabling a specific form of representation and multiplication of embodied affects, collaborative art-research proved to be well-suited to elucidate intimate border violence. It sheds light on how coloniality underpins it, its operating logic and dynamics and how Latin American women resist it. Embodied empathetic responses from those collaborating with and witnessing the project suggest how the power of multiplying affects has a transformative potential to generate or enhance commitments to social and migrant justice.

Responding to an identifiable need for more research that is with and by migrants rather than just about them (Lopes Heimer Citation2022a; Oliveira Citation2019; Temple and Moran Citation2011), I argue that art-research collaborations represent an opportunity to advance a decolonising feminist epistemology (see Curiel Citation2015; Espinosa-Miñoso Citation2014; Lugones Citation2010; Tuhiwai Smith Citation2002). This is because those collaborations can be a privileged site to methodologically centre migrants as epistemic subjects, recognise embodied ways of knowing, collectively produce knowledge, create new meanings and multiply embodied affects. Such ethical concerns are core to the field of borders and migration studies. Migration is a highly political area of contemporary life in which the need for more militant investigations has been firmly recognised (De Genova Citation2013; Vickers Citation2020). We live in a global context of hostility towards migrants, strongly intensified in Britain in the past decade by a conservative government that has installed a de facto hostile environment for migrants (Flynn Citation2015; Griffiths and Yeo Citation2021; Yuval-Davis, Wemyss, and Cassidy Citation2018). Anti-migrant sentiments and discourses have gained widespread traction since the Brexit campaign and have progressively solidified with the passing of ever-stricter and more draconian immigration policies (Brawn Citation2023; Griffiths and Yeo Citation2021; Yuval-Davis, Wemyss, and Cassidy Citation2019). These policies have clear racialised gendered implications, affecting migrant women in deeply embodied ways (Lopes Heimer Citation2022b). I maintain that art-research collaborations have a crucial political potential to examine and unveil this reality through a unique sensibility that brings together diverse standpoints. Through these, it is possible to capture embodied nuances of migration experiences, promoting counter-representations that may provoke embodied forms of empathy and transformative change at the scale of the body.

Drawing on the above mentioned year-long art-research collaborative project investigating Latin American migrant women’s experiences through artistic modes of inquiry and expression, I advocate for the political potential of collaborative art-research to critical migration studies. Art-research can become multipliers of embodied affects in ways to engender transformative processes that can help advance migrant justice. I build and expand on other scholars’ observations regarding using participatory arts-based methods in this field. As Oliveira (Citation2019, 537) contends, when implemented ‘responsibly and ethically, arts-based methods can facilitate empathetic responses and horizontal channels of learning: both of which are critical to dismantling oppression and advancing social justice’ (Oliveira Citation2019, 537). I demonstrate how a unique form of embodied and artistic knowledge has been produced through our collaborative project, which has had a transformative power on the body of collaborators and some audiences. By a transformative power, I mean an ability to produce an empathetic embodied emotional response that may instigate affective action to help change oppressive realities (Bagnoli Citation2009; Finley Citation2014; Guruge et al. Citation2015; Stavropoulou Citation2019, 5).

In the following, I situate the embodied affective potential of art-research within migration studies. I then contextualise the collaborative project ‘stitching voices, stitching bodies’, discussing in detail the various phases, processes and outputs that emerged from it. There were three main phases. The first involved the adaptation and remote implementation of the Cuerpo-Territorio (‘Body-Territory’) method, through which Latin American survivors mapped their embodied experiences of intimate border violence. The video essay ‘Travelling Cuerpo-Territorios’ features this exercise and the maps crafted by survivors. The second phase centred on the embodied process of re-enacting the interview transcripts of five survivors, documented in the short film ‘Embodying Survivors’ Voices’ alongside reflections from the five Latin American women collaborators engaging in re-enactment. The third and final iteration is the video performance, ‘Stitching Voices, Stitching Bodies: An audio-visual cartography of survivorhood’, featuring Nina Franco and bringing together the Cuerpo-Territorio maps produced in the first phase and the recordings of transcript re-enacted in the second.

In the second half of this paper, I analyse the embodied engagements of contributors and audiences with the artistic processes and outputs from this project. I first delve into our second phase to discuss the embodied affects that re-enactment generated and multiplied as part of the art-making/art-research process. In addition to the final published outputs, my analysis draws on video recordings and notes produced throughout the project, and a debrief conversation with Nina months after the project ended. Turning to audience responses to our art pieces, a subsequent section reflects on findings from a pilot Cuerpo-Territorio workshop conducted with a small group of people interested in the project. Although the scale of this project limits my observations, I identify a multiplication of embodied affects on collaborators and this small audience, which suggest how collaborative art-research has a transformative potential on the scale of the body and may hopefully stretch and escalate beyond it.

Addressing migration through art-research methods as multipliers of embodied affects

The past few decades have seen increasing use and consolidation of participatory, collaborative and arts-based methods within social science, geographical and interdisciplinary research. Recently, scholars have been stressing the potential of implementing and combining creative qualitative methods for researching borders and migration in exciting ways (Jeffery et al. Citation2019; Kaptani and Yuval-Davis Citation2008; Oliveira Citation2019). They highlight how these methods advance essential ethical, political, methodological, and empirical perspectives in this field. As they suggest, arts-based methods may enable migrants to exercise their agency in all phases of the research, ensuring research is more representative of their experiences and co-producing more complex, sensory types of data.

Although arts-based research methods arguably bring multiple advantages to migration studies, their potential to multiply embodied affects has not been sufficiently explored. Arts-research methods help overcome the limits of more traditional qualitative methods based on verbal and written data (Daniels Citation2003; Dew et al. Citation2018; Mattingly Citation2001; Oliveira Citation2019). Tolia-Kelly (Citation2007, 340) argues that arts-based methods enable the collection of ‘alternative vocabularies and visual grammars that are not always encountered or expressible in oral interviews’. This is particularly emphasised with respect to sensitive and complex topics that are more difficult to verbalise. Through the arts and their focus on the symbolic (Stavropoulou Citation2019), such tropes can be accessed, explored, articulated and expressed in more subjective and reflective ways (Coemans and Hannes Citation2017; Jeffery et al. Citation2019).

Fascinating reflections on arts-based research’s embodied and affective dimensions are also found in the literature. Discussing their experience using participatory theatre as a sociological research methodology with refugees in East London, Kaptani and Yuval-Davis (Citation2008, 9) argued that this technique produced a specific kind of data and knowledge that is ‘embodied, dialogical and illustrative’. They found this particularly useful for disseminating results suggesting that the illustrative character of theatre scenes reproduced ‘the embodied as well as the affective dimensions of the participants’ experiences and thus trigger empathy’ (Citation2008, 10). In line with this research, I would argue that the type of data and knowledge produced through arts inquiry are not only more complex and interesting but, indeed, potentially affective and embodied. Affect is used to express how people affect and are affected in ways that generate certain bodily responses. It refers to the more embodied, visceral and unconscious dimension of feelings and sensations (Hoggett and Thompson Citation2012). As existing research on affect suggests, bodies can become emotionally invested and affectively interpellated by social, political and economic events, relations and encounters (Ahmed Citation2004; Anderson Citation2006; Hoggett and Thompson Citation2012; Wetherell Citation2015).

As I demonstrate in this paper, art-research collaborations into migration can generate processes and results that evoke bodily responses that multiply affects on participants, researchers/artists and audiences. This is suggested by authors recognising the capacity for arts-based methods to ‘evoke stronger empathetic responses’ (Bagnoli Citation2009; Guruge et al. Citation2015; Stavropoulou Citation2019, 5) and to produce emotional and experiential moments (Kaptani and Yuval-Davis Citation2008). As argued by Finley (Citation2014, 532), critical arts-based research may use ‘the arts to create research experiences that are emotionally evocative, captivating, politically and aesthetically powerful, and that, quite literally, move people to protest, to initiate change, to introduce new and provocative ways of living in the world’. Indeed, the art-research collaborative pieces from my project produced a specific kind of embodied affective atmosphere (Anderson Citation2009) that interpellated participants, collaborators and audiences intersectionally (Crenshaw Citation1991; Citation1989) in ways to call and instigate them into affective action. As Anderson (Citation2009) suggests, ‘affective atmospheres’ could be understood as collective affects, an ‘aura’ or a ‘mood’ that are experienced viscerally and simultaneously by a group of people.

Expanding on critical migration studies’ interest in challenging border violence and colonial views of migrants whilst promoting transformative action towards migrant justice, I advocate for the importance of doing so in an embodied and affective manner. I argue that art-research collaborations can be a privileged site from which this can be performed. This is demonstrated through the project ‘stitching voices, stitching bodies’. Collaborative art-research enhanced our understanding of intimate border violence against Latin American women by multiplying its embodied effects. In the next section, I briefly describe our project, its three phases, and some processes and reflections each generated.

Stitching voices, stitching bodies: contextualising the collaborative art-research project

At the beginning of 2020, I invited my friend and visual artist, Nina Franco,Footnote5 to jointly apply to an art-research collaborative project coordinated and funded by King’s VEM network in collaboration with the Arts Cabinet. Having known and been moved by her activist creative practices with photography and installations addressing themes of gender, race and migration, I was excited to bring together my work as a researcher with her artistic skills and sensibilities to collaboratively create an installation building on data generated as part of my PhD research. We were incredibly excited to have our proposal accepted; however, the pandemic had already kicked in by then, and we had to adapt our work to be conducted remotely and online. As a researcher, I had never collaborated with an artist, and as an artist, Nina had never collaborated with a researcher; neither of us had ever conducted research nor created art in a completely remote way. We took on the challenge and embraced it as an opportunity for both to experiment with new ways of doing. We remained flexible throughout the process, and the final project that emerged from it was organically developed from our video calls, reflections and creative ways of dealing with constraints. Apart from myself, Nina and the 20 anonymous Latin American women survivors who were already participants in my PhD research, we ended up working with another five collaborators – something that was initially unplanned. These included the filmmakers Susy Peña and Sé Carr, the sound engineer Mali Larrignton-Nelson (Shy One) and the Latin American activists Jael Garcia and Tatiana Garavito. Their contribution greatly enriched the project, its processes and results, as more skills and sensibilities were brought together and worked as embodied and artistic layers to investigate and represent deeply complex experiences of border violence, coloniality and resistance ().

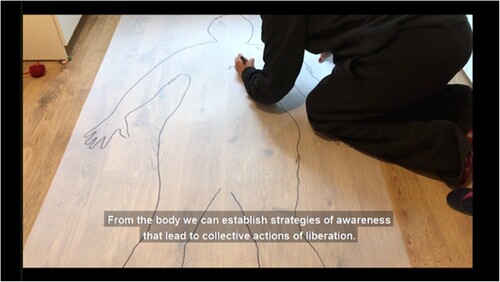

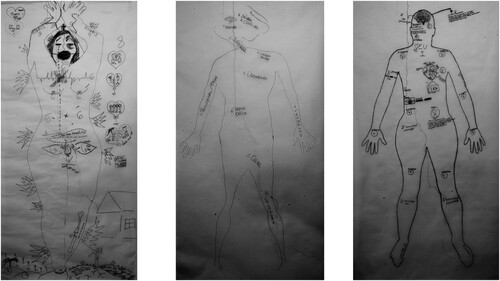

The PhD study on which this collaboration was built investigates Latin American migrant women’s experiences of intimate and state violence and resistance in England (primarily in London), particularly in how these relate to coloniality, territoriality and borders. Adopting a decolonial feminist geographical approach, my research explores how coloniality informs Latin American migrant women’s experiences across multi-scalar spatialities and temporalities. It sheds light on the territorialised effects of violence, starting from the body as the first territory-scale. In this study, I collaborated with the London-based charity Latin American Women’s Aid, where I worked for nearly four years. This organisation generously opened its doors, allowing me to undertake participant observation and facilitating the recruitment of ten Latin American women front-line workers, with whom I conducted in-depth interviews and twenty Latin American women survivors, whom I also interviewed. Ten of them participated in a Cuerpo-Territorio mapping activity carried out as a data collection method for my PhD research and as part of this art-research project (Lopes Heimer Citation2022a). This is a method put forward by Latin American geography collectives and scholars (Colectivo de Geografía Crítica Citation2018; Colectivo Miradas Críticas del Territorio desde el Feminismo Citation2017; Zaragocin and Caretta Citation2020), which builds on the indigenous communitarian feminist notion of Cuerpo-Territorio (‘Body-Territory’) (Cabnal Citation2010; Hernández and Tania Citation2016) that understands bodies and territories as one ().

When our art-research collaboration began, I was halfway through my fieldwork, but I had to stop participant observation and pause interviews due to the pandemic and an ethical commitment with reflecting on and preventing harm. I had planned to conduct a face-to-face Cuerpo-Territorio mapping group activity with the women I interviewed, but due to the pandemic restrictions, I was still trying to re-work how to do this. We also planned to build on the resulting body maps from this activity as part of our art-research collaboration, with Nina artistically layering them for an installation. Having to rethink my PhD methodology and our artistic collaboration simultaneously and in conjunction, working with Nina was crucial to adapt the Cuerpo-Territorio method sensitively and implement it remotely and digitally.

It is crucial to highlight that both my PhD research and this art-research collaboration adhered to rigorous ethical procedures, undergoing review and approval by the King’s ethics committee. All participants and collaborators taking part in this project gave me their informed consent to use the information and materials collectively produced throughout it. As a racialised (mixed-raced) Brazilian migrant woman and an early career migration scholar, my dual identity positions me disruptively and ambivalently. In navigating this, I aimed to engage with the research and contributors ethically, surpassing institutional standards. In this pursuit, I adopted a embodied relational ethics of care and accountability. This involved reflecting on my own positionality, experiences of violence and migration, and journeys in and out of academia, while committing not only to avoiding harm but also countering epistemic violence, amplifying the voices of my community, and generating collective knowledge. Practically, this meant acknowledging unequal power relations, recognising similarities and differences among participants, identifying and accounting for specific contexts of vulnerability, taking the lead without taking control and refusing to reproduce extractive dynamics. Prior to the Cuerpo-Territorio mapping activity, I conducted interviews with each Latin American survivor to build trust and rapport, which helped facilitating the mapping activity with sensitivity. Considering the challenges posed by the pandemic, I personally contacted each participant to check in, explain changes, and encourage thoughtful consideration of potential impacts before continuing. It was essential to recognize women's agency, allowing them to assess their circumstances and decide whether to participate or not (indeed, ten out of twenty declined the invitation, either directly or indirectly). Creating space for collective connection and narrative building became a crucial practice to support one another and process pain throughout all activities. Participants were consistently kept informed about project developments and encouraged to remain involved, even from a distance if they wished. Specifically, in my collaboration with Nina Franco, we maintained professional and personal contact as friends throughout the entire project and beyond, offering support and checking in regarding the potential effects of working on these themes. Nina Franco also reviewed specific parts of this manuscript, reflecting on aspects from our conversations and her personal experiences connected to the project. For a more detailed account of my methodological approach to ethics, refer to Lopes Heimer (Citation2022a).

The first iteration of our project primarily focused on the process of adapting Cuerpo-Territorio.Footnote6 In written and audio-visual formats, it reflects on the ethical and logistical considerations of adapting Cuerpo-Territorio to travel. It also discusses the decolonial feminist potential of doing so and the embodied results imprinted on participants’ maps. Emerging from this experience is a decolonial feminist adapted methodology to study migration, Travelling Cuerpo-Territorios, which I discuss elsewhere (Lopes Heimer Citation2022a). Although there is no scope to offer an in-depth reflection of this methodology here, what is important to highlight about this phase is how all collaborators (research participants included) were able to occupy various positions in the research and creative process. Participants acted as both artists and researchers by mapping their bodies and subsequently decoding their maps. They self-reported gaining new insights about their own embodied experiences of border violence, coloniality and resistance. Crucially, this method enabled them to negotiate and explore embodied experiences relating to different territories they felt connected to and had to navigate across various scales (e.g. from Latin America to Europe and England, cities, neighbourhoods and homes where they lived as well as their own bodies). Similarly, Nina and I also alternated and experienced the positions of artists and researchers. I participated in the editing and producing of our first audio-visual piece, whilst she also actively participated in the undertaking of the Cuerpo-Territorio maps (e.g. by running a pilot, creating a video tutorial and supporting the logistics) ().

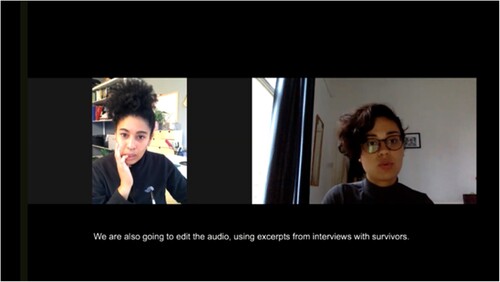

The second contribution from our project is a reflection on the process and embodied affects of re-enacting narratives of violence, coloniality and resistance.Footnote7 To guarantee participants’ safety, we strategically deployed re-enactment as a specific artistic means of expression to address ethical considerations of doing art research with survivors of violence. To preserve survivors’ anonymity whilst still being able to amplify their voices, we re-enacted parts of the transcripts of interviews conducted with survivors instead of using the original recording. These recordings were later used in our final video performance to represent survivors’ experiences in a multi-sensory way, visually and through sound. Re-enacting generated various embodied empathetic responses in each of the collaborators, all of whom were Latin American migrant women who were not actresses. We aimed to reflect on and register those in a short film co-produced between Susy Peña and myself and a poem by Nina Franco.

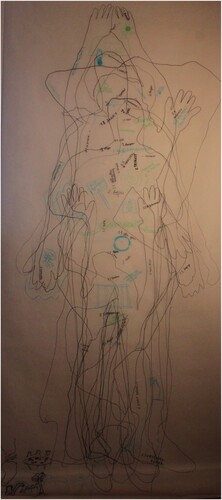

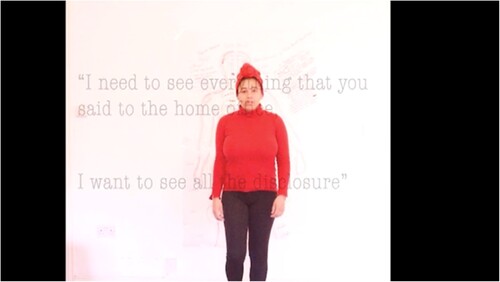

Our final piece is an audio-visual cartography of survivorhood.Footnote8 A video co-produced by Nina Franco and Sé Carr (who also edited it) features a performance by Nina, who artistically layered and brought together ten maps crafted by Latin American survivors of violence who participated in the Cuerpo-Territorio mapping activity. Whilst the re-enacted voices of survivors play in the background, Nina picks up the body maps one by one and overlays them, attaching them to a wall. The video performance created was significantly different from what we first envisioned at the start. This organically developed from the embodied affects and knowledge emerging throughout the project. Nina’s body became a central and active part of the performance alongside ten other Latin American women’s bodies represented by the maps she slowly placed on a wall. She displayed and positioned her own body along with those she overlapped, emphasising how their stories were interconnected and their interconnections needed to be illuminated whilst remaining unique.

Nina’s decision to proceed with the performance in this way conveyed a particular kind of embodied knowledge she acquired throughout our collective creative process. This became clear during our conversations reflecting on this project after it ended. Nina viscerally empathised with the stories of the Latin American women represented in their Cuerpo-Territorio maps. She is, in fact, one of them. However, as the artist responsible for bringing them all together into an art piece, she realised she could not be liable for carrying and healing their pain, even though, as she said, ‘the pain of one is the pain of all’.

Nonetheless, Nina was able to display and amplify their stories, shedding light on the systems of oppression upholding the violence experienced. Through this act, she reasserted how we can connect, support each other and create collective healing practices and spaces, but that healing is ultimately an individual journey. After recording the video, Nina ripped apart the Cuerpo-Territorio maps she had previously stacked together. This was an off-line performative act that played an essential role in her healing process – something which was not planned or expected but presented itself as necessary ().

Figure 4. Screenshot of video performance ‘Stitching Voices, Stitching Bodies: An audio-visual cartography of survivorhood’.

In this art-research collaborative project, we opened up and engaged with multiple embodied positionalities and means of expression, which enabled us to understand better, represent and multiply embodied affects related to the experiences of violence, resistance and migration to which we turned. As we embraced the collaborative and embodied process of art-research and art-making as something as important as its products, we were able to observe, reflect and register our embodied learnings in ways that led us to unexpected places. Acknowledging that power relations can never be equalised entirely (McDowell Citation1992), by complementing each other and exchanging positions, we could at least mitigate those and disrupt hierarchies between art and research. Throughout the creative/research process, we strived to recognise the epistemic and artistic authority of all those involved. By embracing co-production and co-authorship in the art-making process as research inquiry, we can confront epistemic violence (see Alcoff Citation1991; Espinosa-Miñoso Citation2014; Spivak Citation1988), ensuring an active process of research that is more accessible and participatory, particularly for migrants. As Jeffery et al. (Citation2019, 6) contend, ‘the practices of co-production and co-authorship have been instrumental in eliciting new narratives and in challenging the established and hierarchical forms of knowledge productions that are often associated with an elitist intelligentsia’. Similarly, Finley (Citation2008, 74) has stressed how arts-based inquiry can be considered ‘an act of rebellion against the monolithic “truth” that science is supposed to entail’. She contends that knowing through arts has the unique potential to advance ‘critical race, indigenous, queer, feminist, and border theories and research methodologies’ (Finley Citation2008, 72). Indeed, collaborative art-research can confront colonialist and masculinist epistemological traditions based on positivist notions of objectivity in research (see Espinosa-Miñoso Citation2014; Grosfoguel Citation2007; Mignolo Citation2002), welcoming, valuing and bringing into dialogue the standpoint of oppressed subjects in our capacity of thinking-sensing-doing (Alcoff Citation2011; Collins Citation2000; Haraway Citation1988; Trujillo Cristoffanini and Hernández Citation2017). It is, however, essential to note that the transformative power of arts-based methods and art-research collaborations is not a given. The unlocking of their feminist decolonising potential may depend on the quality of the interactions between collaborators, their capacity to acknowledge and navigate power differentials and hierarchical divides between art and science.

Collective art-making as a multiplier of embodied affects: re-enacting narratives of survivorhood

In the second iteration of our collaborative project, five Latin American women re-enacted excerpts from interviews I previously conducted with five other Latin American women as part of my PhD fieldwork. I chose five narratives among the twenty interviews, selecting them based on the unique aspects of their stories, how they were narrated, and how they affected me personally and politically (Anderson Citation2006; Hoggett and Thompson Citation2012). These narratives represented some of the diversity encountered in my research.

Each contributor (including myself and Nina) received three written excerpts of an individual survivor, in which she spoke about three themes I identified from her interview transcript.

The first excerpt narrates a lived experience of abuse underpinned by border violence and coloniality. The second is a narration of embodied affects of violence in emotional, psychological and visceral forms. Finally, in the third set of excerpts, women’s resistance and self-determination are represented by survivors describing an event or process they went through ().

Re-enactment amplified survivors’ voices whilst preserving their safety and anonymity. The impossibility of using the interview recordings with the original voices of survivors removed us one step further from their embodied affects. However, while something was lost, there was also something gained. Survivors’ specific embodied affects were interestingly combined with collaborators’ own affective experiences through re-enactment in a process of multiplying and amalgamation (Anderson Citation2006; Hoggett and Thompson Citation2012). This is observed in video recordings where we re-enact those narratives and provide brief personal reflections on the act of doing so. Apart from myself, nobody had access to the full interview transcripts and interviewees’ personal information beyond what was shared. Collaborators experienced the themes represented through the passages using their bodies and imagination to fill the gaps, creating something that became neither just themselves nor a copy of the survivor whose story they were re-enacting, but rather something new out of the merger of the two. Some of our embodied reflections were collaboratively edited between myself and the filmmaker Susy Peña, included in a short film as part of our second submission (see ), which provides a glimpse of this process of re-enactment. We reflected on how reading and re-enacting were profoundly emotional and moving, felt through our bodies. It is possible to note in the film how our facial expressions changed as we read each phrase, our bodies sometimes shrank, and the tone of our voices trembled. We felt in our bodies specific emotions that we aimed to transmit in our voices: sadness, anger, rage, pain, and loneliness, but also strength, inspiration, and a deep sense of commitment and responsibility to the women represented in those sentences. These embodied affective responses emerged in different shapes and forms, which I now discuss in more detail by focusing on the experiences of each of our collaborators.

Tatiana Garavito, a Colombian facilitator and organiser, re-enacted Hermana's words. Hermana is a white, middle-class Mexican woman who experienced psychological, emotional, verbal, sexual and economic violence from her white, middle-class, English ex-husband in London after migrating to get married. Hermana was targeted with intimate border violence as her husband used his nationality (together with his white male economic privilege) against her immigration status and positionality as a migrant from the South. He used this power imbalance to further his abuse through institutions, threatening Hermana with destitution, criminalisation and deportation. Tatiana reflected how, as she re-enacted this narrative; she felt in the tone of her words the pain and loneliness experienced by Hermana as she confronted intimate border violence from her ex-husband, rooted and normalised by/through institutions.

I feel anger, I feel very uncomfortable. I can feel the dynamics of power of an abusive relationship and can also see how institutions like the Home Office and lawyers are also part of these violences that women face. […] I could feel in the tone of the words used the pain and loneliness, so it brings me a lot of sadness on top of anger to see that these things continue to happen.[…] I also feel a commitment and responsibility that we need to continue to support each other and build networks of support to liberate us from those systems.

(Tatiana Garavito, Colombian mixed-raced migrant woman, facilitator and organiser)

A similar kind of embodied knowledge and affective responsive action was generated in Jael Garcia, a Mexican facilitator and migrant organiser. She re-enacted the story of Diana, a mixed-race, working-class Mexican woman who experienced multiple forms of intimate violence at the hands of her white middle-class English husband. In addition to intimate border violence, coloniality was visibly embedded in the dynamics of abuse experienced by Diana. Her intersecting gender, race, class and nationality identities were used as grounds for her husband to reassert a colonial sense of superiority, based on which he inferiorised and dehumanised her (Crenshaw Citation1991; Lugones Citation2010). After re-enacting Diana’s experiences, Jael Garcia expressed deep pain and sadness at realising how colonial stereotypes about racialised Mexicans, like herself, continue to be reproduced to this day and are being exploited within intimate dynamics of abuse. This made her reflect on her own embodied experiences as a racialised migrant Mexican woman, reaffirming her ongoing commitment towards herself and her peers to fight against such colonial stereotypes.

It’s painful to know that those colonial stereotypes are present in intimate dynamics, it is sad that this reality is still happening. […] This filled me with sadness and brought me back to a cycle of thinking and rethinking my own story, how as a racialised migrant woman, one has to fight on many fronts and sometimes against those kinds of stereotypes.

(Jael Garcia, Mexican mixed-raced migrant woman, community organiser and activist)

Nina Franco, a Brazilian visual artist and main collaborator of the project, re-enacted the story of Arami, a mixed-race indigenous woman from Paraguay who spent years undocumented in England. She was targeted with state and intimate border violence and physical, emotional, psychological and economic abuse. Re-enacting reawakened memories of Nina’s past, making her feel the pain of Arami on her own body. The process of creating our last iteration, the video performance, also had a triggering embodied effect on Nina as she listened to all five narratives repeatedly. This coincided with a worsening period of the pandemic in Brazil and Nina herself experiencing intimate border violence from a previous partner. She needed time and space from the project, as the closeness to other women’s painful embodied experiences of border violence directly spoke to her own. Being her friend and knowing some of her personal journeys helped me navigate this process with her, interpreting her silences as a form of communication and reassuring her that her well-being was a priority over the timeline and outcomes of the project. This unexpected embodied effect on Nina emerged from several factors relating to the project’s theme and visceral character, the pandemic context and her own experiences with border violence as a Black Brazilian migrant woman living in England. Months later, Nina reflected on how although those themes had for a long time been part of her artistic practice (used to amplify her personal and political commitments as well as a form of healing), this particular engagement made her feel an unprecedented weight. She felt unable to carry this and transform it until she changed her approach, leading to the final video performance piece taking a different shape and form than what she initially imagined (as briefly discussed in the previous section).

Having witnessed, registered and discussed the embodied affects of re-enacting narratives of violence and resistance, I suggest that collective art-making as research engendered some forms of transformation (Bagnoli Citation2009; Finley Citation2014; Guruge et al. Citation2015; Stavropoulou Citation2019). Even though each of us re-enacted a different story and approached it from a unique embodied positionality, the embodied processes triggered by this experience followed a similar pattern. I summarise this in three interrelated emerging processes: (1) gaining an embodied knowledge about the nature of violence, (2) an embodied sense of relatability, and (3) an impetus to reaffirm an embodied commitment to affective action to resist violence and act in solidarity. The multiplication of embodied affects was not strictly felt by collaborators who re-enacted survivors’ voices. To edit and clean the audio files we recorded, the British-Carribean sound engineer Mali Larrington-Nelson, had to listen to them repeatedly, and in her words, those narratives ‘really set in’ and ‘stayed with her’. She explained: ‘It really opened my eyes, as someone who was born here and is concerned with the injustices, issues and oppressions that women face, that I was unaware of the extra threat that migrant women can sometimes face […]’. As she suggests, this collaborative art-making experience furthered her understanding of the dynamics of intimate border violence of which she was previously unaware.

Collaborative art-research as multipliers of embodied affects

In December 2021, I ran a small pilot workshop with a small group of eight people to understand the embodied effects of our collaborative art-research on audiences. I invited them to experience and respond to our art pieces by making a collective Cuerpo-Territorio map. In this section, I discuss the potential of our pieces to multiply embodied effects on people engaging with them from variously embodied positionalities by drawing on findings from this experience. Since then, I have organised similar workshops with other audiences that responded similarly; however, those subsequent activities and discussions were not systematically recorded. My analysis, is, therefore, limited to the collective Cuerpo-Territorio map (see ) created by participants during this initial workshop and the debriefing discussion in which they decoded this map in detail. Although I do not intend to overgeneralise my findings, I suggest they may provide a glimpse of the transformative potential that embodied collaborative art-research may trigger in some audiences.

Eight participants from diverse backgrounds took part in this workshop, all of whom were university educated. Four identified as women, two as men, and two as genderqueer/fluid. Three were white British citizens, two were white European citizens, and three were non-white European citizens (one mixed Italian, one Arab French citizen, and a mixed-race Peruvian with Spanish nationality). Two identified as heterosexual, and six identified along the queer spectrum (two as bisexual, two as pansexual, one as dyke and one as gay). I showcased the audio-visual pieces related to the three stages of our collaborative project and asked them to witness and register their embodied sensations, feelings, emotions and memories on a body-size piece of paper. The artistic result of this activity is presented in . In this case, the Cuerpo-Territorio method was applied differently than with survivors from our project. Instead of drawing their silhouettes on individual pieces of paper, all participants drew their bodies on the same paper, on top of and overlapping each other. They each chose a particular position to lay on the paper according to their feelings; some laid down facing upwards or downwards; opened or closed hands, facing up or down; one participant knelt, whilst another held her arms together on top of her head. The result is a collective body with varied and sometimes overlapping positions, emotions, memories, sensations and feelings – representing the multiplicity of embodied affects emerging from our collaborative art pieces and how these touch different bodies in unique ways.

Some of the empathetic bodily responses related to quite visceral sensations which were recurring in more than one participant, such as difficulty breathing and suffocation around the neck and chest; feeling cold and paralysed; feeling sick, nauseous, pain and emptiness in the stomach. Some emerging emotions included anger, rage, distrust, sorrow, shock, upset, impotence/helplessness and sadness – mainly around the head and chest, but also hands. These connected to identified feelings of disillusionment and humiliation, but also a deep respect for the power of survivors – which were embodied around arms and legs. Through drawings around their bodies, participants represented spatialised embodied memories related to places such as detention centres, job centres, and police stations. They also expressed feelings and images of objects such as fences, chains, and a protest placard (written ‘your borders kill’). They drew a sun and a butterfly – a symbol for the ‘migration is beautiful’ pro-migration movement led by artists.Footnote9 Between the legs and below the feet of the body, a Latin American participant drew trees and roots, people sharing food around a table, homes, and the map of Latin America – later explained to be symbols for healing and resistance.

Empathetic reactions fluctuated in participants’ bodies. Whilst they experienced the oppressing weight of violence as near to immobilising, the strength of survivors seemed to trigger a more active transformative response to it. For example, IndigoFootnote10, a white Spanish non-binary person, described how these stories quite viscerally touched their body. They felt a weight on their shoulders and their neck suffocating at realising ‘how borders are making, allowing power dynamics that are putting people in danger’. This brought up memories of a detention centre in Germany, where border violence materialised. Indigo used their white European passport holder privilege to support migrants by accompanying them and interpreting. They identified breathing as a helpful embodied conscious act to move from the intense visceral responses triggered by violence towards healing and transformative action. They contended: ‘The breathing was like let’s go back to where my power is, and it’s through the breathing, opening out this weight’.

Similarly, as a white cis British man, Richard also viscerally felt the dynamics of border violence as anger on his hands and discomfort on his shoulder. The art pieces brought up a visceral memory of border violence against a migrant woman he previously supported as part of housing organising. On the recalled occasion, his body privilege helped challenge border violence as he stood against a xenophobic landlord trying to attack a migrant woman physically. This incident stayed in his body, and he was able to reconnect with it through the embodied representations of intimate border violence showcased in our art pieces. As he described:

I remember this angry and really xenophobic man shouting there, so I wrote the location there on my shoulders, and I had not realised how it had affected me, but then all these stories of men trying to use the border system, it really brought that for me, that violent situation.

As a white English woman, Sarah viscerally related to some of the dynamics of intimate partner violence brought up by the three iterations whilst also reflecting on how these enabled her to appreciate how her own experiences differed from migrant women whose abuse is furthered through institutions. This, therefore, advanced her understanding of (intimate) border violence. As she contends,

realising how much worse it is for migrant women, feeling this sickness really that just carries on and carries on […] people using their power and institutions as another dimension of power to just exploit women in this way, makes me sick.

Roots, which is food, which is sharing, which is talking, being with each other. Bodies don’t function in isolation, function interpersonally and that can also be a way of saving of themselves, of healing, of transforming. It also reminded me of a protest placard, something that we use quite a lot, but also that the body is the placard in itself, saying how ‘borders kill’ and coloniality still exists.

Conclusion

Amidst a deteriorating scenario of anti-migrant policies and discourses, this paper responded to an ethical need to methodologically advance research committed to migrant justice (De Genova Citation2013; El-Enany Citation2020; Vickers Citation2020; Yuval-Davis, Wemyss, and Cassidy Citation2019). Building and expanding the literature on arts-based methods, I argued for using art-research collaborations in migration studies (Coemans and Hannes Citation2017; Daniels Citation2003; Dew et al. Citation2018; Finley Citation2014; Mattingly Citation2001). Whilst essential benefits of deploying creative methods to investigate borders and migration have been previously established, I contributed to this debate by showing their capacity to multiply embodied affects, particularly when implemented collaboratively (Jeffery et al. Citation2019; Kaptani and Yuval-Davis Citation2008; Oliveira Citation2019). I illustrated this by drawing on the generative processes and affects emerging from the art-research collaborative project ‘stitching bodies, stitching voices’, which investigated the experiences of Latin American migrant women in England concerning (intimate) border violence, coloniality and resistance (Lopes Heimer Citation2022b; Citation2023). Mobilising multiple complementary art techniques and social science research skills, we were able to develop and implement creative methods not only to collect data, but also as unique modes of inquiry, representation and dissemination of research (Finley Citation2008; McNiff Citation2008).

In the context of this project, collaborative art-research enabled the multiplication of embodied affects concerning intimate border violence in ways that demonstrates the decolonising feminist potential that such methods bring to migration studies (Curiel Citation2015; Espinosa-Miñoso Citation2014; Lugones Citation2010). Firstly, this was evidenced in its ability to counter epistemic violence by enabling marginalised intersecting positionings and sensibilities to be granted epistemic authority to collectively explore and represent intimate border violence (Alcoff Citation1991; Espinosa-Miñoso Citation2014; Spivak Citation1988). Collaborators involved in the art-research/art-making process occupied and alternated between various positions (as artists, researchers, and participants) in ways that helped mitigate power relations and productively complemented sensibilities, skills and experiences. This disrupts Western masculinist research premises favouring thinking over sensing, separating mind from body, and valuing single authorship over co-creation. Secondly, as we collectively developed the project, we were affected by its themes and processes and, in turn, affected and shaped the collective art outputs in a deeply embodied manner. Art-making triggered embodied affects on collaborators, enhancing our understanding of state and intimate border violence linked to coloniality and resistance (Lopes Heimer Citation2022b; Lugones Citation2010; Quijano Citation2000). Connecting with Latin American migrant women’s embodied experiences reaffirmed our commitment to affective action in resistance and solidarity (Anderson Citation2006). Thirdly, and connected to this, our collective art pieces may generate similar multiplying affects on audiences open to interacting with them through their bodies. The collaborative Cuerpo-Territorio map produced by a small audience during my pilot session powerfully illustrated this. Participants were affected intersectionally in unique and transformative ways at the scale of the body. Participants’ overlapping positions, emotions, memories, sensations and feelings represented in the map the multiplicity of embodied affects triggered by our pieces. It is, however, worth noting the limited scope of this project and that other audiences may respond in different ways. Similarly, although I identified a transformative affective process on the scale of the body, the extent to which this escalates to other scales and leads to meaningful individual and collective affective actions is uncertain. Whether this potential is fulfilled and this renewed sense of collective responsibility becomes materialised is a question that this paper cannot answer.

Despite the limitations of my observations, I advocate for the potential of collaborative art research to advance migrant justice. Collective art-making can function as a mode of inquiry into the embodied affects of border violence and have a transformative power to multiply those affects on participants, collaborators and audiences, potentially calling and bringing them into action. This is particularly important in critical migration studies, where there is a commitment and urgency to disrupting colonising views of migrants and opposing policies and practices that perpetuate symbolic and material violence against us (Lopes Heimer Citation2022a; Oliveira Citation2019; Temple and Moran Citation2011). Similar formats of horizontal multi-layered art-research collaborations may be implemented by researchers interested in expanding decolonising feminist epistemological perspectives that are attentive to the transformative potential of embodied affects.

Acknowledgements

I am profoundly grateful to all the Latin American women participating in my PhD project and the Latin American Women’s Aid for generously opening their doors for me to conduct this research. I also want to thank all the other collaborators of the art-research project ‘stitching bodies, stitching voices’: Nina Franco, Jael Garcia, Mali Larrignton-Nelson, Sé Carr, Susy Peña, and Tatiana Garavito. This project would not have been possible without their sensibilities, emotions, skills, enthusiasm, and friendship. This art-research collaborative project was funded by the Visual and Embodied Methodologies Network based at King’s College London, and CAPES Brazil funded my PhD research. I thank the co-editors of this special issue for their comments and feedback on an earlier version of this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 It was originally written in Portuguese and translated into English by myself.

10 All names of people identified in this section were replaced by pseudonyms in order to preserve participants’ anonymity.

References

- Ahmed, Sara. 2004. “Affective Economies.” Social Text 22 (2): 117–139. https://doi.org/10.1215/01642472-22-2_79-117.

- Alcoff, Linda. 1991. “The Problem of Speaking for Others.” Cultural Critique 20: 5. https://doi.org/10.2307/1354221.

- Alcoff, Linda. 2011. “An Epistemology for the Next Revolution.” Transmodernity 1 (2): 67–78.

- Anderson, Ben. 2006. “Becoming and Being Hopeful: Towards a Theory of Affect.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 24 (5): 733–752. https://doi.org/10.1068/d393t.

- Anderson, Ben. 2009. “Affective Atmospheres.” Emotion, Space and Society 2 (2): 77–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emospa.2009.08.005.

- Bagnoli, Anna. 2009. “Beyond the Standard Interview: The Use of Graphic Elicitation and Arts-Based Methods.” Qualitative Research 9 (5): 547–570. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794109343625.

- Brawn, Steph. 2023. “‘Draconian’ Asylum Bill Could Leave 40,000 Kids Destitute or Locked Up.” The National, March 22, 2023. https://www.thenational.scot/news/23403811.draconian-asylum-bill-leave-40-000-kids-destitute-locked/.

- Cabnal, Lorena. 2010. Feminismos diversos: el feminismo comunitario. Barcelona: ACSUR-Las Segovias.

- Carlisle, Frances. 2006. “Marginalisation and Ideas of Community among Latin American Migrants to the UK.” Gender & Development 14 (2): 235–245. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552070600747230.

- Cassidy, Kathryn. 2019. “Where Can I Get Free? Everyday Bordering, Everyday Incarceration.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 44 (1): 48–62. https://doi.org/10.1111/tran.12273.

- Coemans, Sara, and Karin Hannes. 2017. “Researchers Under the Spell of the Arts: Two Decades of Using Arts-Based Methods in Community-Based Inquiry with Vulnerable Populations.” Educational Research Review 22 (November): 34–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2017.08.003.

- Colectivo de Geografía Crítica. 2018. “Geografiando Para La Resistencia. Los Feminismos Como Práctica Espacial.” Cartilla 3. Quito: Colectivo de Geografía Crítica de Ecuador.

- Colectivo Miradas Críticas del Territorio desde el Feminismo. 2017. Mapeando el cuerpo territorio. Guía metodológica para mujeres que defienden sus territorios. Quito: Colectivo Miradas Críticas del Territorio desde el Feminismo.

- Collins, Patricia Hill. 2000. Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment. New York: Taylor & Francis.

- Crenshaw, Kimberle. 1989. “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics.” University of Chicago Legal Forum 1989 (1, Article 8): 139.

- Crenshaw, Kimberle. 1991. “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence Against Women of Color.” Stanford Law Review 43 (6): 1241–1299. https://doi.org/10.2307/1229039.

- Curiel, Ochy. 2015. “Construyendo metodologías feministas desde el feminismo decolonial.” In Otras formas de (re)conocer: reflexiones, herramientas y aplicaciones desde la investigación feminista, edited by Irantzu Mendia Azkue and Barbara Biglia, 45–60. Bilbao: Universidad del País Vasco.

- Daniels, Doria. 2003. “Learning About Community Leadership: Fusing Methodology and Pedagogy to Learn About the Lives of Settlement Women.” Adult Education Quarterly 53 (3): 189–206. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741713603053003004.

- De Genova, Nicholas. 2013. “‘We Are of the Connections’: Migration, Methodological Nationalism, and ‘Militant Research’.” Postcolonial Studies 16 (3): 250–258. https://doi.org/10.1080/13688790.2013.850043.

- Dew, Angela, Louisa Smith, Susan Collings, and Isabella Dillon Savage. 2018. “Complexity Embodied: Using Body Mapping to Understand Complex Support Needs.” Forum: Qualitative Social Research 19 (2): 25.

- El-Enany, Nadine. 2020. (B)Ordering Britain. Manchester: Manchester University Press. https://doi.org/10.7765/9781526145437.

- Espinosa-Miñoso, Yuderkys. 2014. “Una crítica descolonial a la epistemología feminista crítica.” El Cotidiano 184: 7–12.

- Finley, Susan. 2008. “Chapter 6 - Arts-Based Research.” In Handbook of the Arts in Qualitative Research Perspectives, Methodologies, Examples, and Issues, edited by J. Gary Knowles and Ardra L Cole, 71–82. Los Angeles: Sage Publications.

- Finley, Susan. 2014. “An Introduction to Critical Arts-Based Research: Demonstrating Methodologies and Practices of a Radical Ethical Aesthetic.” Cultural Studies ↔ Critical Methodologies 14 (6): 531–532. https://doi.org/10.1177/1532708614548123.

- Flynn, Don. 2015. “Frontier Anxiety: Living with the Stress of the Every-Day Border.” Soundings 61 (61): 62–71. https://doi.org/10.3898/136266215816772241.

- Griffiths, Melanie, and Colin Yeo. 2021. “The UK’s Hostile Environment: Deputising Immigration Control.” Critical Social Policy 00 (0): 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261018320980653.

- Grosfoguel, Ramón. 2007. “The Epistemic Decolonial Turn: Beyond Political-Economy Paradigms.” Cultural Studies 21 (2–3): 211–223. https://doi.org/10.1080/09502380601162514.

- Guruge, Sepali, Michaela Hynie, Yogendra Shakya, Arzo Akbari, Sheila Htoo, and Stella Abiyo. 2015. “Refugee Youth and Migration: Using Arts-Informed Research to Understand Changes in Their Roles and Responsibilities.” Forum: Qualitative Social Research 15 (3): 37.

- Haraway, Donna. 1988. “Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective.” Feminist Studies 14 (3): 575. https://doi.org/10.2307/3178066.

- Hernández, Cruz, and Delmy Tania. 2016. “Una Mirada Muy Otra a Los Territorios-Cuerpos Femeninos.” Solar 12 (1): 45–46.

- Hoggett, Paul, and Simon Thompson, eds. 2012. Politics and the Emotions: The Affective Turn in Contemporary Political Studies. New York: Continuum.

- Hyndman, Jennifer. 2001. “Towards a Feminist Geopolitics.” Canadian Geographies / Géographies Canadiennes 45 (2): 210–222. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-0064.2001.tb01484.x.

- Hyndman, Jennifer. 2012. “The Geopolitics of Migration and Mobility.” Geopolitics 17 (2): 243–255. https://doi.org/10.1080/14650045.2011.569321.

- Jeffery, Laura, Mariangela Palladino, Rebecca Rotter, and Agnes Woolley. 2019. “Creative Engagement with Migration.” Crossings: Journal of Migration & Culture 10 (1): 3–17. https://doi.org/10.1386/cjmc.10.1.3_1.

- Kaptani, Erene, and Nira Yuval-Davis. 2008. “Participatory Theatre as a Research Methodology: Identity, Performance and Social Action among Refugees.” Sociological Research Online 13 (5): 1–12. https://doi.org/10.5153/sro.1789.

- Lopes Heimer, Rosa dos Ventos. 2022a. “Travelling Cuerpo-Territorios: A Decolonial Feminist Geographical Methodology to Conduct Research with Migrant Women.” Third World Thematics: A TWQ Journal, 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/23802014.2022.2108130.

- Lopes Heimer, Rosa dos Ventos. 2022b. “Bodies as Territories of Exception: The Coloniality and Gendered Necropolitics of State and Intimate Border Violence Against Migrant Women in England.” Ethnic and Racial Studies online (December), 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2022.2144750.

- Lopes Heimer, Rosa dos Ventos. 2023. Coloniality, (Body-)Territory and Migration: Decolonial Feminist Geographies of Violence and Resistance among Latin American Women in England. London: Kings College London.

- Lugones, María. 2010. “Toward a Decolonial Feminism.” Hypatia 25 (4): 742–759. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1527-2001.2010.01137.x.

- Mattingly, Doreen. 2001. “Place, Teenagers and Representations: Lessons from a Community Theatre Project.” Social & Cultural Geography 2 (4): 445–459. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649360120092634.

- Mbembe, Achille Joseph. 2003. “Necropolitics.” Translated by Libby Meintjes. Public Culture 15 (1): 11–40. https://doi.org/10.1215/08992363-15-1-11.

- McDowell, Linda. 1992. “Doing Gender: Feminism, Feminists and Research Methods in Human Geography.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 17 (4): 399. https://doi.org/10.2307/622707.

- McIlwaine, Cathy, and Diego Bunge. 2016. Towards Visibility: The Latin American Community in London. London: Queen Mary University of London.

- McIlwaine, Cathy, and Diego Bunge. 2019. “Onward Precarity, Mobility, and Migration among Latin Americans in London.” Antipode 51 (2): 601–619. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12453.

- McIlwaine, Cathy, Juan Camilo Cock, and Brian Linneker. 2011. No Longer Invisible. London: Queen Mary University of London.

- McNiff, Shaun. 2008. “Chapter 3 - Art-Based Research.” In Handbook of the Arts in Qualitative Research Perspectives, Methodologies, Examples, and Issues, edited by J. Gary Knowles and Ardra L Cole, 29–40. Los Angeles: Sage Publications.

- Mignolo, Walter. 2002. “The Geopolitics of Knowledge and the Colonial Difference.” South Atlantic Quarterly 101 (1): 57–96. https://doi.org/10.1215/00382876-101-1-57.

- Oliveira, Elsa. 2019. “The Personal Is Political: A Feminist Reflection on a Journey Into Participatory Arts-Based Research with Sex Worker Migrants in South Africa.” Gender & Development 27 (3): 523–540. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552074.2019.1664047.

- Quijano, Aníbal. 2000. “Colonialidad del Poder y Clasificacion Social.” Journal of World Systems Research VI (2): 342–386. https://doi.org/10.5195/jwsr.2000.228.

- Román-Velázquez, Patria, and Jessica Retis. 2021. Narratives of Migration, Relocation and Belonging: Latin Americans in London. London: Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-53444-8_4.

- Smith, Susan J., and Rachel Pain. 2016. “Chapter 1 Fear: Critical Geopolitics and Everyday Life.” In Fear: Critical Geopolitics and Everyday Life, edited by Rachel Pain and Susan J. Smith, 19–40. Routledge.

- Spivak, Gayatri Chakravorty. 1988. “Can the Subaltern Speak?” Die Philosophin 14 (27): 42–58. https://doi.org/10.5840/philosophin200314275.

- Stavropoulou, Nelli. 2019. “Understanding the ‘Bigger Picture’: Lessons Learned from Participatory Visual Arts-Based Research with Individuals Seeking Asylum in the United Kingdom.” Crossings: Journal of Migration & Culture 10 (1): 95–118. https://doi.org/10.1386/cjmc.10.1.95_1.

- Temple, Bogusia, and Rhetta Moran, eds. 2011. Doing Research with Refugees: Issues and Guidelines. Bristol: Policy Press.

- Tolia-Kelly, Divya P. 2007. “Fear in Paradise: The Affective Registers of the English Lake District Landscape Re-Visited.” The Senses and Society 2 (3): 329–351. https://doi.org/10.2752/174589307X233576.

- Trujillo Cristoffanini, Macarena, and Paola Contreras Hernández. 2017. “From Feminist Epistemologies to Decolonial Feminism: Contributions to Studies About Migrations.” Athenea Digital 17 (1): 145–162. https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/athenea.1765.

- Tuhiwai Smith, Linda. 2002. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous People. New York: Zed Books and University of Otago Press.

- Turcatti, Domiziana, and Carlos Vargas-Silva. 2022. “‘I Returned to Being an Immigrant’: Onward Latin American Migrants and Brexit.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 45 (16): 287–307. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2022.2058884.

- Vickers, Tom. 2020. “Activist Conceptualisations at the Migration-Welfare Nexus: Racial Capitalism, Austerity and the Hostile Environment.” Critical Social Policy, 026101832094802. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261018320948026.

- Wetherell, Margaret. 2015. “Trends in the Turn to Affect: A Social Psychological Critique.” Body & Society 21 (2): 139–166. https://doi.org/10.1177/1357034X14539020.

- Wright, Melissa W. 2011. “Necropolitics, Narcopolitics, and Femicide: Gendered Violence on the Mexico-US Border.” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 36 (3): 707–731. https://doi.org/10.1086/657496.

- Yuval-Davis, Nira, Georgie Wemyss, and Kathryn Cassidy. 2018. “Everyday Bordering, Belonging and the Reorientation of British Immigration Legislation.” Sociology 52 (2): 228–244. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038517702599.

- Yuval-Davis, Nira, Georgie Wemyss, and Kathryn Cassidy. 2019. Bordering. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Zaragocin, Sofía, and Martina Angela Caretta. 2020. “Cuerpo-Territorio: A Decolonial Feminist Geographical Method for the Study of Embodiment.” Annals of the American Association of Geographers 0 (0): 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/24694452.2020.1812370.