Background

The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) of 2022, which calls for maximum fair prices (MFP) to be implemented in drug price negotiations, has made promises and introduced new uncertainties into the process. This has sparked debates on how to properly evaluate the price of a product and how to compare it with the traditional United States (US) manufacturer price setting and subsequent automatic discount.

Value-based pricing—or setting prices according to the consumer’s perceived or estimated value of a product or service—has been suggested as a potential negotiation tool or foundation for pricing discussions.Citation1 While these discussions are fairly new in the US market, they have been ongoing in other countries for more than three decades. In the US, the Panel on Cost-Effectiveness in Health and MedicineCitation2 (also known as the Washington Panel) and the Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy (AMCP) guidelinesCitation3 have included economic evaluation components for many years; however, economic value was included as more of an ancillary tool than a fundamental tool for negotiation. The establishment of the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (ICER) in 2006,Citation4 which gained wider impact in 2013 as an independent not-for-profit organization, can be viewed as a key milestone in introducing value-based pricing discussions in the US, through their first official report on unsupported price increases in 2019.Citation5

According to the IRA, the final negotiated prices of the first ten selected Medicare Part D drugs are mandated to be published in 2024 and go into effect by 2026.Citation6–8 The negotiation process will exclude “qualifying single source drugs” under section 1192(e) (i.e. certain orphan drugs approved for only one disease, low-spend Medicare drugs (under $200 million), plasma-derived products, and will delay biologics negotiation when biosimilar entry is imminent.Citation8 At this time, it is unclear whether the IRA’s stated factors for determining MFPs (section 1194(e))Citation8 will lead the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) to use a broad perspective that includes value-based pricing, or a more restricted approach based solely on comparative effectiveness, manufacturing costs and costs invested for drug development.Citation9 As explained in the CMS documentation, the current drug negotiation process proposed by CMS rejects the use of quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) or other “lower value” of survivalFootnotei.Citation7 Based on section 1194(e) of the CMS Act.Citation7 Nonetheless, discussions on the most appropriate way to set healthcare technology prices in the US are more pertinent than ever.

The value-based pricing approach

Value-based pricing can help us understand the quantified value of a product and set the proper price for new technologies. However, the interpretation of value-based pricing in pharmaceuticals varies considerably and therefore its translation into practice differs by country.Citation9

Two specificities of healthcare products (compared with non-healthcare products) that support limitations of the traditional pricing approaches (i.e. cost-based approach) include (1) the target consumer being different from the payer, and (2) the leading role of research and development (R&D) in pharmaceutical development. The fact that the payers (i.e. an umbrella term for insurance companies or public players [healthcare systems]), who fund most of the healthcare products and services, are rarely the target consumers (patients) creates the need for a holistic approach such as societal perspective evaluation (or a broadened healthcare perspective) since a pure patient/financial perspective would likely be too restrictive and exclude many important costs and benefits. In addition, payers can restrict reimbursement of drugs, making them unpredictable stakeholders.

In R&D, manufacturers must constantly engage in research, making R&D an ongoing investment rather than a fixed cost. In addition, the nature of R&D in healthcare makes it difficult to rely on a “cost-based” approach due to large, fixed costs (e.g. factory and laboratory certification, and regulatory and reimbursement processes) that are difficult to isolate and properly identify. Therefore, a more refined approach is needed to evaluate pricing based on the WTP threshold for consumers and payers.

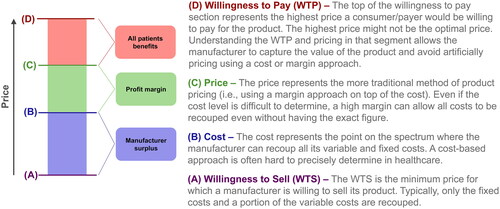

According to economic theory, product pricing evolves on a spectrum, from the lowest (“willingness to sell”) to the highest price (willingness to pay [WTP]), as outlined in .Citation1 At the lowest end of the spectrum (A), not all variable costs are covered, but the manufacturer can recoup some fixed costs. At the high end, the maximum price a customer is willing to pay (D) also elicits the value and preference for a health commodity or service directly from target beneficiaries, while maximizing a profit margin.Citation10

Figure 1. The four components of the value-based spectrum.

Inspired by Stobierski, T., 2022.Citation11

Regarding the willingness-to-sell value (A), the theory suggests that the manufacturer could tolerate this selling price for some time, but at the risk of the inability to undergo the difficult and expensive reimbursement and regulatory processes. Another approach is a cost-based price (B), which covers both fixed and variable costs but does not compensate for the product’s full value or include a proper firm margin. Manufacturers are unlikely to promote products when they can only recoup their total fixed and variable costs, as it may restrict them from setting up advanced factories and laboratories and investing in R&D in the healthcare market, which can be unpredictable. Manufacturers need a reasonable profit margin (C) to ensure they can continue innovating and repaying past innovation efforts.

The other end of the price spectrum (i.e. WTP) is where most healthcare products lie. In healthcare, this portion of the range is likely much wider than in most product markets because healthcare innovations can result in life-changing, if not life-saving outcomes, generating a broader range of potential values.

Cost-effectiveness analyses (CEA) are generally considered a form of value-based pricing referred to as extra-welfarist approaches in traditional economics. Extra-welfaristCitation12 approaches have been strongly preferred by health technology assessment (HTA) agencies worldwide. These approaches involve only partial monetization of the benefits and use clinical outcomes or adjusted quality-of-life measurements as the denominator to create an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio. While these analyses simplify the calculation and avoid some difficult questions, such as the monetization of quality of life or life in general, they offer a restricted view of the pricing range since they do not fully monetize WTP. Nevertheless, they are useful and effective for payers’ and HTA decision-making and were recommended by the Washington panel in addition to being currently in use by the ICER organization for their assessments.Citation2 In the meantime, CEAs as applied by most HTA agencies are not compatible with the CMS US negotiation framework since they require the use of a “lower value” life expectancy, typically using the QALYs.Citation7 Amongst other things, these health outcomes’ measures include age adjustments and disability adjustments that would prevent CMS from using classical efficiency evaluation based on section 1194(e) of the act.Citation7 Therefore, a different method is required. One solution could be to use the equal value of life years gained (evLYG) as proposed by the ICER organization,Citation13 but it must be noted that other standard practices of cost-effectiveness evaluation, such as discounting, could be considered as implying “lower value” for some life years, regardless of the use of QALYs.

In contrast, welfaristFootnoteii approaches involve complete monetization and are considered part of the wider cost-benefit analysis (CBA) family.Citation14 They are rarely used for decision-making by payers but can be extremely useful in evaluating the full spectrum of potential prices since they assess the full WTP in value-based pricing. Since most decision-makers use extra-welfarist approaches, welfarist approaches are rarely discussed. Welfarist approaches have limitations, but one important advantage in the US context is the potential avoidance of QALYs or “lower value” life years. The typical goal of HTA economic evaluations is to determine the best use of funds using a societal or healthcare payer perspective, regardless of development and market access costs for a manufacturer. Since the CMS goal seems to be anchored around finding an optimal price, we suggest classical efficiency evaluation (such as cost-effectiveness models) could be more difficult to implement in this context.

Discussion: how to set my price?

The impact of the new policy is predictable. Manufacturers will go through a more formalized drug price negotiation process, and the number of products affected by these changes could increase rapidly in the coming years. The exclusion of orphan drugs shows intention to avoid curbing innovation. In addition, the methodology for developing the “initial [price]offer” involves the identification of therapeutic alternatives and their price evaluating the clinical benefit of the drug to determine a “preliminary price” and finally adjust to negotiation factors.Citation7 Therefore, the number and price of alternatives, in addition to the therapeutic advantages of the novel therapy will critically affect price positioning. More specifically, the therapy will have to solve unmet needs or address specific population needs, which would result in price premiums. How should manufacturers prepare for negotiating the price of a product? Manufacturers’ prices could be set at a lower or higher point in the pricing range. To ensure you end up with a sustainable price, manufacturers should (1) be aware of their product’s value; (2) be prepared to defend its optimal price; and (3) set the price fairly and competitively.Citation15

To be aware of a product’s value, manufacturers need to ensure that their trial design or primary data collection is properly structured to gather data on a technology’s economic and social values. Additionally, you need to be prepared to perform the appropriate analyses, including statistical analyses and economic evaluations, to demonstrate your product’s value.

To defend the optimal price of a product, manufacturers need to establish a proper evidence base supported by strong clinical and primary data collection; evaluate the costs for the product and its alternatives, but also the economic value; develop a compelling value proposition that addresses unmet needs and patient burden; and prepare solid deliverables for payers and HTA agencies to secure proper reimbursement.

Finally, to set a fair and competitive price, manufacturers will need to evaluate the competitive market and ensure that the pricing respects the capacity of patients and payers to pay, while also positioning their product to look appealing compared with the current market leaders in your indication. This final step must be based on the evidence accumulated in the first two steps and will result in a recommended price for your product. Setting a price too low may leave money on the table and potentially hinder the manufacturers’ capacity for future innovation, while setting a price too high may lead to aggressive price negotiations from payers.

In relation to the new IRA regulations, manufacturers will need to adapt and actively develop value messaging that goes beyond the traditional pricing analyses (e.g. reference pricing, customary HTA-style economic evaluations, etc.) to strengthen the pricing foundation and defend the development and manufacturing costs. The messaging should focus on the product’s therapeutic advantages in comparison to alternative products and ability to target unmet needs, which will act as the basis of the negotiation and rationale for the preliminary price after adjustments. Additionally, manufacturers will need to submit well designed and organized comparative and costing data, as referred to by CMS as the “comparative effectiveness” and “manufacturer-specific data”.Citation7

Considering that payers often adopt an extra-welfarist approach, using a welfarist value-based pricing approach does not exempt manufacturers from fully demonstrating the economic value of their product according to HTA guidelines or developing the materials required for reimbursement submission.

Value-based pricing is a means to determine a fair, evidence-based, and reasonable price for all parties involved rather than a strategy to maximize or achieve the highest price. We highly recommend investing in resources to demonstrate the economic value of the product. If the goal is to meet the requirements of global and US payers, prioritize a standard approach as prescribed by the guidelines (extra-welfarist). In situations where challenging internal or external stakeholder discussions are necessary to determine the appropriate price, we strongly recommend exploring a more comprehensive welfarist approach to gain a complete understanding of the optimal price range. This approach can provide a superior evidence-based foundation for any pricing discussions.

Transparency

Reviewer disclosures

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

GT, AP, LM – Cytel Inc., Employee.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

i Section 1194(e) – ‘…, the Secretary should not use evidence from comparative clinical effectiveness research in a manner that treats extending the life of an elderly, disabled, or terminally ill individual as of lower value than extending the life of an individual who is younger, nondisabled, or not terminally ill’.

ii Welfarism, as applied in cost-benefit analysis, should be understood as interpersonal comparisons of monetary uncompensated gains or losses made, that assign an equal unitary shadow weight to each dollar gain or loss, independently of whose it is.

References

- Shafrin J, Lakdawalla D, Doshi J, et al. A strategy for value-based drug pricing under the inflation reduction act. Health Affairs Forefront. 2023.

- Gold M. Panel on cost-effectiveness in health and medicine. Med Care. 1996;34(12 Suppl):DS197–DS199.

- Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy. The AMCP format for formulary submissions: a format for submission of clinical and economic evidence in support of formulary consideration. Alexandria, VA: AMCP; 2016. https://www.amcp.org/sites/default/files/2019-03/AMCP-Format-V4.pdf.

- Institute for Clinical and Economic Review. ICER’s Impact Boston, MA: ICER; 2023. Available from: https://icer.org/who-we-are/history-impact/.

- Institute for Clinical and Economic Review. Unsupported price increase report: 2019 assessment. Boston, MA: ICER; 2019. http://icerorg.wpengine.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/ICER_UPI_Final_Report_and_Assessment_110619.pdf.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare Drug Price Negotiation Program: selected drugs for initial price applicability year 2026. CMS [cited August 29, 2023]. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/files/document/fact-sheet-medicare-selected-drug-negotiation-list-ipay-2026.pdf.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare drug price negotiation program: revised guidance, implementation of sections 1191–1198 of the social security act for initial price applicability year 2026. Baltimore, Maryland: CMS; 2023. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/revised-medicare-drug-price-negotiation-program-guidance-june-2023.pdf.

- United States House of Representatives. Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 [cited August 16, 2022]. Available from: https://www.congress.gov/117/plaws/publ169/PLAW-117publ169.pdf.

- Angelis A, Lange A, Kanavos P. Using health technology assessment to assess the value of new medicines: results of a systematic review and expert consultation across eight European countries. Eur J Health Econ. 2018;19(1):123–152. doi: 10.1007/s10198-017-0871-0.

- Abbas SM, Usmani A, Imran M. Willingness to pay and its role in health economics. J Bahria Uni Med Dent Coll. 2019;09(01):62–66. doi: 10.51985/JBUMDC2018120.

- Stobierski T. A beginner’s guide to value-based strategy Cambridge, MA2022. Available from: https://online.hbs.edu/blog/post/value-based-strategy.

- Shafrin J. Healthcare economist [Internet] 2008 [cited August 5, 2023]. Available from: https://www.healthcare-economist.com/2008/02/13/welfarists-vs-extra-welfarists/.

- Institute for Clinical and Economic Review. 2020-2023 value assessment framework. Boston, Massachusetts: ICER; 2020. https://icer.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/ICER_2020_2023_VAF_102220.pdf.

- Brouwer WBF, Culyer AJ, van Exel NJA, et al. Welfarism vs. extra-welfarism. J Health Econ. 2008;27(2):325–338. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2007.07.003.

- Moon S, Mariat S, Kamae I, et al. Defining the concept of fair pricing for medicines. BMJ. 2020;368:l4726. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l4726.