Abstract

Aims

To describe healthcare resource utilization (HRU) and costs of patients with metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer (mCSPC).

Methods

Linked data from Flatiron Metastatic PC Core Registry and Komodo’s Healthcare Map were evaluated (01/2016-12/2021). Patients with chart-confirmed diagnoses for metastatic PC without confirmed castration resistance in Flatiron who initiated androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) monotherapy or advanced therapy for mCSPC in 2017 or later (index date) with a corresponding pharmacy or medical claim in Komodo Health were included. Advanced therapies considered were androgen-receptor signaling inhibitors, chemotherapies, estrogens, immunotherapies, poly ADP-ribose polymerase inhibitors, and radiopharmaceuticals. Patients with <12 months of continuous insurance eligibility before index were excluded. Per-patient-per-month (PPPM) all-cause and PC-related HRU and costs (medical and pharmacy; from a payer’s perspective in 2022 $USD) were described in the 12-month baseline period and follow-up period (from the index date to castration resistance, end of continuous insurance eligibility, end of data availability, or death).

Results

Of 871 patients included (mean age: 70.6 years), 52% initiated ADT monotherapy as their index treatment without documented advanced therapy use. During baseline, 31% of patients had a PC-related inpatient admission and 94% had a PC-related outpatient visit; mean all-cause costs were $2551 PPPM and PC-related costs were $839 PPPM with $787 PPPM attributable to medical costs. Patients had a mean follow-up of 15 months, during which 38% had a PC-related inpatient admission and 98% had a PC-related outpatient visit; mean all-cause costs were $5950 PPPM with PC-related total costs of $4363 PPPM, including medical costs of $2012 PPPM.

Limitations

All analyses were descriptive; statistical testing was not performed. Treatment effectiveness and clinical outcomes were not assessed.

Conclusion

This real-world study demonstrated a significant economic burden in mCSPC patients, and a propensity to use ADT monotherapy in clinical practice despite the availability and guideline recommendations of advanced life-prolonging therapies.

PLAIN LANGUAGE SUMMARY

Prostate cancer is one of the most common causes of male cancer death. Almost 1/10 men who are diagnosed early develop advanced disease. Androgen deprivation therapy (ADT), which reduces male hormone levels to slow prostate cancer growth, is part of the standard care for early-stage and advanced/metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer. This form of cancer still responds to hormonal treatment. Recently, new advanced therapies targeting cancer in different ways than ADT and offering benefits in survival and disease progression have become available and are associated with improved survival compared to treatment with only ADT. However, the usage and costs of these therapies in men with advanced hormone-sensitive prostate cancer are not well-understood. Our study utilized clinical information and health insurance data to examine the treatments and healthcare costs for 871 men with advanced hormone-sensitive prostate cancer who received drug treatment between 2017–2021 in the United States. After diagnosis of advanced hormone-sensitive prostate cancer, over half of the men received only ADT without any advanced therapies. Before their disease advanced, patients with early-stage prostate cancer had $2,550 in monthly healthcare costs, increasing to almost $7,000 after the disease became advanced but before starting treatment for this advanced stage. After patients began treatment, costs were ∼$6,000 monthly, with three-quarters of this cost being directly related to prostate cancer. These results emphasize the significant healthcare costs associated with advanced prostate cancer. They underline the importance of considering comprehensive treatment options to enhance patient outcomes and potentially reduce the economic impact of advanced prostate cancer.

Introduction

In men, prostate cancer (PC) represents the most common cancer and the second leading cause of cancer death, with an estimated 288,300 new cases and 34,700 deaths expected in the United States (US) in 2023.Citation1 Though early detection of PC can result in a favorable prognosis, approximately 4% of cases are detected only after metastasis and nearly 10% of diagnosed localized PC progresses to metastatic PC.Citation2,Citation3 PC that metastasizes to bone and other sites, such as lymph nodes, lungs, and liver, increases the complexity of clinical management and can be a major contributor to PC-related mortality, with a 5-year relative survival rate of ∼30% and a 10-year relative survival rate of less than 20%.Citation3,Citation4

Androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) via surgical or medicinal castration has long been a key component in the standard of care for localized and metastatic PC.Citation5,Citation6 However, the annual progression rate to metastatic disease despite ADT is estimated to be nearly 35% in the US, and metastatic patients with initially castration-sensitive PC (mCSPC) typically progress to castration-resistant PC (mCRPC) within a mean of 2–3 years.Citation7 In recent years, the treatment landscape for PC has evolved with advanced therapies that have been approved for the treatment of patients at mCSPC stage of disease, including androgen-receptor signaling inhibitors (ARSIs; e.g. apalutamide approved in 2019 for mCSPC,Citation8 abiraterone acetate plus prednisone approved in 2018 for high-risk mCSPC,Citation9 enzalutamide approved in 2019 for mCSPCCitation10) which have demonstrated improved clinical outcomes, including overall survival (OS), compared to ADT alone in clinical trials.Citation11,Citation12 Importantly, these advanced therapies have been shown to slow progression to castration resistance among patients with mCSPC.Citation13

In addition to the clinical implications associated with progression to metastatic PC in terms of patient morbidity and mortality, previous real-world studies in the US have demonstrated substantial increases in healthcare resource utilization (HRU) and costs once patients progress from localized PC to mCSPC.Citation14 However, recent studies show that the utilization of advanced therapies is low in clinical practice, with the majority of patients continuing treatment with only ADT.Citation14,Citation15 Given the updated treatment landscape and the promising clinical benefits associated with these advanced therapies, there is a need for a contemporary characterization of real-world treatment patterns, HRU, and economic burden among patients diagnosed with mCSPC. To that end, this retrospective study aims to describe treatment patterns, HRU, and costs of patients with mCSPC treated with ADT monotherapy or advanced therapies.

Methods

Data sources

In order to identify patients with mCSPC who were treated with ADT monotherapy or advanced therapy for mCSPC and provide information on HRU and costs, electronic medical record (EMR) data from the Flatiron Metastatic PC Core Registry (01/01/2013–12/01/2021) were linked to anonymized payer claims for patients with medical and prescription benefit information including insurance eligibility from Komodo’s Healthcare Map (01/01/2014–12/01/2021). Data from Flatiron and Komodo Health were de-identified and comply with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) per Title 45 of Code of Federal Regulations, Part 46.101(b)(4).

The Flatiron Registry comprises patients with a diagnosis of PC (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth/Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-9-CM: 185.x or ICD-10-CM: C61.x]) who have explicit physician documentation of metastatic disease and ≥2 clinical visits on different days in the network. It is a longitudinal database which includes patient-level de-identified structured and unstructured data from ∼280 US cancer clinics (∼800 sites of care representing 10-15% of men living with metastatic PC in the US, based on 2018 prevalence estimatesCitation16) curated via technology-enabled abstraction.Citation17,Citation18 The structured EMR data contain detailed clinical information and the unstructured data were abstracted from physicians’ notes and other documents using natural language processing and comprise information on demographics, doctor visits, laboratory tests and vitals, diagnoses, medication administration, medication prescriptions and orders, clinical performance status, and insurance data. The Flatiron Registry also includes information on PC-related characteristics that may not be available in other databases, such as the stage of disease at the initial diagnosis, the date of the initial PC diagnosis, the date of diagnosed progression to metastatic PC and mCRPC, PSA levels, and mortality.

Komodo’s Healthcare Map contains over 320 million US patients insured through Medicaid, Commercial insurance, and Medicare. For medical claims with missing cost information, Komodo relied on an algorithm to impute medical costs from a payer’s perspective derived based on several factors including the type of claim, payer’s channel (e.g. Medicare and commercial insurance), type of service, and setting of care.Citation19 When the costs for pharmacy claims were unavailable, they were imputed with the median amount from a payer’s perspective of the medication by national drug code and payer channel or in reference to the National Average Drug Acquisition Cost and Medicare Average Sales Price.Citation15 Payer claims evaluated in this study from Medicare and Medicaid insurers included claims from Medicare Advantage and Medicaid managed care plans.

The linkage was performed by Datavant using their patent-pending, machine learning validated, de-identification technology to create patient-specific tokens in Komodo Health and Flatiron data sources, allowing linkage without sharing underlying patient information.Citation20 The analysis of this study is exempt from institutional review for the following reasons: (a) it is a retrospective analysis of existing data with no patient intervention or interaction, and (b) no patient identifiable information is included in the EMR and claims datasets.Citation21 Flatiron Health, Inc., Komodo Health Solutions, and Datavant did not participate in the data analyses.

Sample selection and study design

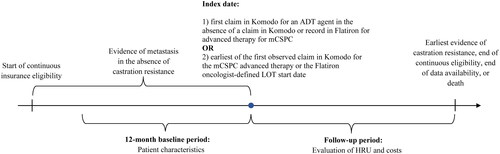

This was a retrospective, longitudinal cohort study design of patients with mCSPC, including a subgroup of those who initiated their first advanced Flatiron oncologist-defined line of therapy (LOT; i.e. ARSIs, chemotherapies, estrogens, immunotherapies, poly [ADP-ribose] polymerase [PARP] inhibitors, and radiopharmaceuticals) on or after the date of mCSPC diagnosis (). Adult patients were included in the study if they had a chart-confirmed diagnosis for metastatic PC in the absence of confirmed CRPC (based on a Flatiron algorithm incorporating physician-reported CRPC in medical charts, observed rise in PSA levels while on hormone therapy, or physician-documented rise in PSA levels on hormone therapy plus a change in treatment).

Figure 1. Study design scheme. ADT: androgen deprivation therapy; HRU: healthcare resource utilization; LOT: line of therapy; mCSPC: metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer.

In order to capture contemporary information on outcomes among patients who initiated more recently approved regimens for the treatment of mCSPC, the index period spanned from 01/01/2017 until 12/01/2021. The overall cohort was composed of patients with mCSPC meeting one of the following mutually exclusive treatment criteria on or after the date of assessment of mCSPC status (and prior to evidence of castration-resistance, if observed): (1) first claim in Komodo for an ADT agent (index date) in the absence of a claim in Komodo or record in Flatiron for advanced therapy for mCSPC anytime; or (2) initiation of a Flatiron oncologist-defined advanced LOT for mCSPC with a corresponding claim in Komodo (advanced therapy subgroup) with the index date representing the earliest between: the first observed claim in Komodo for the mCSPC therapy or the Flatiron oncologist-defined LOT start date.

All patients were required to have ≥12 months of continuous insurance eligibility in Komodo Health records prior to the index date (i.e. the baseline period). Within the 12-month baseline period, the mCSPC pre-treatment period was defined as the portion of the 12-month baseline period that occurred after evidence of metastasis and before the initiation of therapy. It was possible for patients to not contribute time to the mCSPC pre-treatment period if the first evidence of metastasis occurred on the index date. The follow-up period spanned from the index date until the earliest of evidence of castration resistance, the end of continuous insurance eligibility, the end of data availability, or death. The study outcomes were described during the two portions of the 12-month baseline period as well as during the follow-up period. In addition, to understand the characteristics of the subgroup of patients treated with ADT monotherapy, baseline demographic and clinical variables were described.

Outcome measures and statistical analyses

Treatment utilization (i.e. ADT, ARSIs, chemotherapy, and immunotherapy) defined based on a record in Flatiron EMR data was reported during the baseline period and on the index date. Closed claims from Komodo Health were used to describe the all-cause and PC-related HRU and costs during the baseline (overall and during the mCSPC pre-treatment period) and follow-up periods. HRU included inpatient admissions (number of admissions, number of days with admissions), number of days with emergency room visits, number of days with outpatient visits, number of pharmacy claims, and number of days with other services. Healthcare costs were reported as medical costs (i.e. sum of inpatient, emergency room, outpatient, and other costs), pharmacy costs, and total healthcare costs (sum of medical and pharmacy costs). PC-related HRU and costs were defined based on claims with a diagnosis code for malignant neoplasm of the prostate (identified with ICD-10-CM code C61) in any diagnostic position or claims with procedure codes for luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone or other therapies for mCSPC (i.e. ARSIs, chemotherapies, estrogens, immunotherapies, PARP inhibitors, and radiopharmaceuticals). All HRU and cost outcomes were reported per-patient-per-month (PPPM) and costs were measured from a payer’s perspective and expressed in 2022 US dollars. The study was descriptive in nature, and measures were reported using means, medians, and standard deviations (SDs) for continuous variables, and frequencies and proportions for categorical variables. All analyses were conducted using SAS Enterprise Guide software Version 7.15.

Results

Baseline characteristics

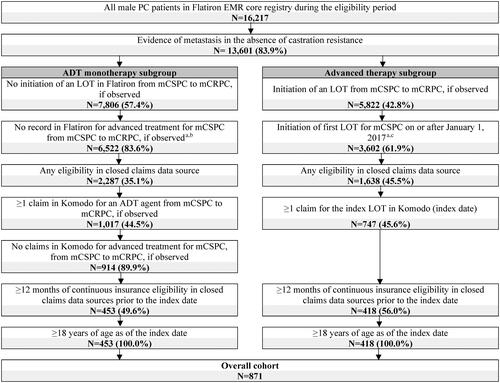

A total of 871 patients with mCSPC were included in the study, among them a subgroup of 453 patients (52.0%) were treated with ADT monotherapy while a subgroup of 418 patients (48.0%) initiated advanced therapy (). In the overall cohort, the mean (median) age was 70.6 (71.0) years, 56.1% of the patients were White and 13.1% were Black, 48.0% were insured through Medicare, 42.5% were commercially insured, and 89.7% were treated in community practice. Patients in the advanced therapy subgroup had a mean (median) age of 67.6 (67.0) years, 56.0% were White and 14.4% were Black, 37.1% were insured through Medicare, 53.1% were commercially insured, and 90.0% were treated in community practice. The mean time between the first observed PC diagnosis and mCSPC status was 37.5 months for the overall cohort and 24.3 months for the advanced therapy subgroup (). Among the subgroup of 453 patients (52.0%) treated with ADT monotherapy, the mean (median) age was 73.3 (76.0) years, 56.3% of the patients were White and 11.9% were Black, 57.8% were insured through Medicare, 34.4% were commercially insured, and 89.4% were treated in community practice (Supplemental Table 1).

Figure 2. Identification of the study population. ADT: androgen deprivation therapy; ARSIs: androgen receptor signaling inhibitors; EMR: electronic medical records; LOT: line of therapy; mCRPC: metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer; mCSPC: metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer; PARP: poly ADP-ribose polymerase; PC: prostate cancer.

aMedications considered as advanced treatment for mCSPC therapy were: ARSIs (i.e., apalutamide, darolutamide, enzalutamide, abiraterone acetate), chemotherapy (i.e., cabazitaxel, carboplatin, cisplatin, docetaxel, etoposide, mitoxantrone), PARP inhibitors (i.e., niraparib, olaparib, rucaparib, talazoparib), immunotherapy (i.e., sipuleucel-T, pembrolizumab), estrogens (i.e., estramustine phosphate, diethystilbestrol, polyestradiol phosphate), radiopharmaceuticals (i.e., radium-223, lutetium-177-PSMA-617).

bRecords for medications used as advanced treatment for mCSPC were evaluated in the Flatiron oncologist-defined LOT tables, as well as medication orders, administrations, and oral tables.

cPatients with clinical trial medication were excluded.

Table 1. Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics.

Healthcare resource utilization

In the overall cohort, the mean (median) mCSPC pre-treatment period during baseline was 3.7 (1.7) months, with most patients contributing time to this period (99.1%). In the advanced therapy subgroup, the mean mCSPC pre-treatment period during baseline was 3.0 (1.7) months and most patients contributed time (99.3%). The mean (median) follow-up period was 14.9 (11.2) months in the overall cohort and 14.5 (12.0) months in the advanced therapy subgroup (). In the overall cohort, 34.3% of patients had their follow-up period censored because they progressed to castration resistance, this proportion was 26.6% in the advanced therapy subgroup, and 41.5% among patients treated with ADT monotherapy.

Table 2. Baseline and follow-up HRU PPPM.

During the full 12-month baseline period, 45.2% of patients in the overall cohort had an all-cause inpatient admission with a mean of 1.1 days PPPM, the mean length of admission was 9.5 days. Over the same period, 31.2% of patients had a PC-related inpatient admission for a mean of 0.6 days PPPM and a mean length of admission of 13.3 days; 93.6% of patients had a PC-related outpatient visit for a mean of 0.7 days PPPM. During the follow-up period, in the overall cohort, 45.2% of patients had an all-cause inpatient admission for a mean of 2.0 days PPPM and a mean length of admission of 13.9 days; 98.6% of patients had an all-cause outpatient visit for a mean of 2.9 days PPPM, 37.9% of patients had a PC-related inpatient admission for a mean of 1.8 days PPPM and a mean length of admission of 17.1 days; 97.6% of patients had a PC-related outpatient visit for a mean of 1.8 days PPPM ().

During the 12-month baseline period, 46.7% of patients in the advanced therapy subgroup had an all-cause inpatient admission for a mean of 0.8 days PPPM and a mean length of inpatient visit of 8.7 days; 99.5% of patients had an all-cause outpatient visit for a mean of 1.9 days with outpatient visits PPPM. Over the same period, 32.3% of those patients had a PC-related inpatient admission for a mean of 0.6 days PPPM and a mean length of admission of 11.7 days; 94.0% of patients had a PC-related outpatient visit for a mean of 0.8 days PPPM. During the follow-up period, in the advanced therapy subgroup, 46.2% of patients had an all-cause inpatient admission for a mean of 1.7 days PPPM and mean length of admission of 14.3 days; 98.8% of patients had an all-cause outpatient visit for a mean of 3.2 days with outpatient visits PPPM, 40.4% of patients had a PC-related inpatient admission for a mean of 1.6 days PPPM and a mean length of admission of 16.5 days; 97.6% of patients had a PC-related outpatient visits for a mean of 2.1 days PPPM ().

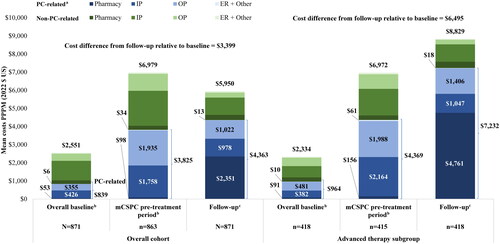

Costs

During the 12-month baseline period, mean all-cause costs for patients in the overall cohort were $2551 PPPM and PC-related costs were $839 PPPM, including $787 PPPM attributable to PC-related medical costs and the remainder comprising pharmacy costs. Baseline costs were generally higher in the mCSPC pre-treatment period, with $6,979 PPPM in mean all-cause costs and $3825 PPPM in PC-related costs, $3727 of which was attributable to PC-related medical costs among patients in the overall cohort. Patients in the overall cohort had a mean (median) of 14.9 (11.2) months of follow-up, during which mean all-cause costs were $5950 PPPM with PC-related costs of $4363 PPPM. This increase in PC-related costs was driven in part by higher PC-related medical costs following mCSPC therapy initiation or treatment with ADT monotherapy ().

Figure 3. Baseline and follow-up costs PPPM. ARSI: androgen receptor signaling inhibitor; ER: emergency room; HRU: healthcare resource utilization; ICD-10-CM: International Classification of Diseases 10th Revision Clinical Modification; IP: inpatient; LHRH: luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone; OP: outpatient; mCSPC: metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer; PARP: poly ADP-ribose polymerase; PC: prostate cancer; PPPM: per-patient-per-month; US: United States.

Notes:

aPC-related HRU and costs were identified with the ICD-10-CM code C61 and procedure codes for LHRH or of the following guideline-recommended therapies for mCSPC: ARSIs, chemotherapy, PARP inhibitors, immunotherapy, estrogens, and radiopharmaceuticals.

bThe mCSPC pre-treatment period was defined as the portion of the 12-month baseline period that occurred on and after evidence of metastasis but prior to the initiation of therapy.

cThe follow-up period was defined as the time from the index date until the earliest of i) evidence of castration resistance, ii) end of continuous insurance eligibility, iii) end of data availability, or iv) death (if available).

During the 12-month baseline period, patients in the advanced therapy subgroup had mean all-cause costs of $2334 PPPM and PC-related costs of $964 PPPM, with $874 PPPM attributable to PC-related medical costs and the remainder comprising pharmacy costs. In the advanced therapy subgroup during the mCSPC pre-treatment period, costs were higher relative to the overall baseline period with $6972 PPPM in mean all-cause costs and $4,369 PPPM in PC-related costs, $4213 of which was attributable to PC-related medical costs. Patients in the advanced therapy subgroup had a mean (median) of 14.5 (12.0) months of follow-up, during which mean all-cause costs were $8829 PPPM with PC-related costs of $7232 PPPM. The increase in PC-related costs was driven in part by higher PC-related medical costs which increased after mCSPC therapy initiation ().

Treatment patterns

Most patients had evidence of ADT use in the baseline period in both the overall cohort (65.1%) and the advanced therapy subgroup (74.4%). During the 12-month baseline period, in the overall cohort and advanced therapy subgroup, 22.5% and 27.0% of patients used leuprolide, 47.3% and 51.7% used bicalutamide, and 17.7% and 36.8% used ARSIs (). More than half of patients in the overall cohort received ADT monotherapy as their index treatment (52.0%). In the overall cohort, the most common index treatments, which were initiated as monotherapy, were leuprolide (43.7%), followed by abiraterone acetate (20.2%), docetaxel (15.3%), enzalutamide (7.1%), and degarelix (5.6%). Among patients in the advanced therapy subgroup (48.0% of overall cohort), abiraterone acetate (42.1%), docetaxel (31.8%), enzalutamide (14.8%), and apalutamide (6.0%) were the most frequently initiated index treatments, which were initiated as monotherapy ().

Table 3. Baseline and index treatment patterns.

Discussion

This study employed novel methodology to provide a contemporary assessment of treatment patterns and real-world HRU and economic burden of patients with mCSPC in the US. In general, disease progression was associated with higher inpatient, outpatient, and pharmacy costs. Despite the availability of advanced therapies with proven survival benefit,Citation11–13 more than 50% of patients with mCSPC continued to be treated with only ADT monotherapy, which in addition to lower OS, has also been associated with substantial incremental HRU and medical costs.Citation14,Citation22

PC treatment costs are increasing more rapidly than those associated with any other cancer

In recent years, the costs associated with treating PC have been increasing more rapidly than those associated with any other cancer in the US,Citation23 with aggregate healthcare costs attributable to metastatic PC estimated by Olsen et al. in 2023 to exceed $8 billion per year.Citation24 Consistent with the findings of the current analysis, previous real-world studies have also documented increases in HRU and costs as PC progresses.Citation14,Citation25,Citation26 Based on linked SEER-Medicare data, the estimated mean difference between the annualized cancer-related costs associated with the first stage of PC and those incurred once the disease becomes metastatic is over $50,000 at 12 months after diagnosis driven by an increase in HRU.Citation25 Using administrative claims data from Commercial, Medicare Advantage and Medicare Fee-for-Service-insured patients, Ryan et al. found that HRU increased after the onset of metastases in CSPC patients resulting in 4-5 times higher health plan paid costs.Citation14 Similarly, Trinh et al. used data from commercial insurance and Medicare claims to show that patients incurred approximately 3 times the total direct all-cause healthcare costs once their disease progressed from localized to mCSPC over a mean follow-up period of 15 months which was primarily driven by an increase in HRU.Citation26 In the current study, once patients initiated treatment for mCSPC, the PPPM days for PC-related inpatient admissions and PC-related outpatient visits more than doubled and PC-related costs increased more than a 5-fold. The increase in PC-related costs reached 7-fold among the subgroup of patients who initiated advanced therapies. Importantly, incremental PC-related costs were the highest when comparing the baseline period (which included time prior to the evidence of metastasis) to the mCSPC pre-treatment period, with marginal increases following the initiation of therapy, highlighting the substantial economic impact of progression to metastasis among patients with PC. Considering the benefit of identifying patients with PC earlier in their disease journey and providing treatment with effective therapies, the 2023 American Urological Association guidelines recommend that clinicians offer germline and somatic genetic testing for patients with mCSPC.Citation27 To that end, certain clinical non-invasive biomarker panels might also be helpful in predicting disease development and could be further utilized for accompanying screening and diagnostics as well as targeted progression prevention.Citation28,Citation29

Suboptimal treatment with ADT monotherapy despite the availability of advanced therapies for mCSPC

Interestingly, over half of the study population remained treated with ADT monotherapy despite the availability of advanced therapies for mCSPC. This is consistent with the low advanced therapy utilization previously reported in the real-world clinical practice in the US.Citation14,Citation15 Ryan et al. showed that among previously untreated patients with mCSPC identified between 2015 and 2019, 40–50% remained untreated or deferred treatment, approximately 45% were treated with ADT monotherapy, and only 2–13% used abiraterone acetate and/or docetaxel.Citation14 Recently, the treatment guidelines for patients with mCSPC report that based on available evidence, ADT monotherapy is no longer considered sufficient treatment for mCSPC.Citation27 In a series of clinical trials, there was significant evidence of improved clinical outcomes, including OS, associated with the use of ADT in combination with advanced therapies compared with ADT monotherapy for patients with previously untreated mCSPC.Citation30–33 Relative to ADT alone, the LATITUDE trial showed that ADT in combination with abiraterone acetate plus prednisone was associated with a significant benefit for OS and progression-free survival in addition to significantly reducing the risk of PSA progression,Citation31 and the TITAN trial showed a significant benefit in terms of 2-year OS for ADT in combination with apalutamide.Citation32 Evidently, advanced therapy helps slow mCSPC patients’ progression to castration resistance which is important as patients with longer time to castration resistance have been found to have longer OS, particularly if they were able to achieve a rapid and deep PSA response during the first mCSPC therapy.Citation13,Citation34 In the current study, patients in the ADT monotherapy subgroup tended to be older than those who received advanced therapies, which is consistent with the low utilization of advanced therapy among older patients with mCSPC observed in Veterans Health Administration claims from 2013 to 2018, whereby 60% received ADT monotherapy and only 13% used abiraterone acetate and/or docetaxel.Citation15 Therefore, treatment decision-making for older patients with mCSPC in clinical practice warrants the consideration of important factors, such as frailty and comorbidities, with the aim of improving treatment tolerance and reducing barriers to care.Citation35

Expert recommendations and outlook

Given that the economic and clinical burden of castration resistance is substantially greater than that of castration sensitivity,Citation14,Citation36,Citation37 this study underscores the unmet needs of patients with mCSPC as many continue to be treated with ADT monotherapy which, despite a smaller economic burden, is inconsistent with clinical guideline recommendations based on poor response to treatment and suboptimal long-term outcomes. Therefore, patients with mCSPC must be given the opportunity to initiate advanced treatment which would optimize their clinical outcomes, including extending survival and delaying progression to mCRPC as well as avoiding the associated incremental economic burden.

Limitations

The findings of the current study should be interpreted in light of certain limitations. All analyses were descriptive in nature; therefore, formal statistical testing is needed to confirm the observed numeric trends. Treatment effectiveness and clinical outcomes were not assessed in this study and warrant further investigation. Additionally, the current study reported costs using a payer perspective, hence it did not incorporate an evaluation of indirect costs (i.e. absenteeism and presenteeism costs) or other intangible costs (e.g. indirect costs faced by caregivers) related to the illness, the inclusion of which would have resulted in a more comprehensive estimate of the economic burden of mCSPC. The use of administrative claims data depends on the correct recording of diagnosis, procedure, and drug codes such that inaccuracies may lead to case misidentification. Moreover, although the Datavant Match method used for linking the two data sources is highly precise, errors may have occurred in identifying all claims for a patient or all matches between the data sources. Cost information is not consistently available in the Komodo Health database, with missing costs in approximately 30% of claims. As a result, the imputation for these missing costs was conducted by Komodo, which may not reflect the actual costs incurred by payers. Although this study highlights major economic implications associated with mCSPC, these results may still underestimate the financial burden with the increased use of newer triplet regimens in mCSPC (i.e. abiraterone acetate or darolutamide + ADT + docetaxel). This study included a large proportion of patients with de novo mCSPC and did not include patients with mCSPC who were not treated with either ADT or advanced therapies, which may have limited the generalizability of study results. Furthermore, the findings of this study may not be representative of the entire population of patients with mCSPC in the US as data were obtained from two linked sources, one which represents the community and academic oncology perspective and another comprising open-source healthcare claims data. Finally, the study period spanned between 01/01/2013 and 12/01/2021, overlapping the COVID-19 pandemic. Several studies have characterized the way in which the pandemic challenged the provision of and accessibility to healthcare services, including for patients with PC.Citation38 Further research is warranted to evaluate the impact of the pandemic on clinical practice patterns and its effect on the healthcare costs of PC disease management.

Conclusions

This real-world study used novel methods to demonstrate the significant economic burden in patients with mCSPC using linked clinical and claims-based data in the US. Despite the availability of advanced therapies, over half of the patients continued treatment with ADT monotherapy. Though the costs associated with advanced therapy for patients with mCSPC can be high, the economic burden of disease progression itself is substantial, as reflected in the high incremental PC-related costs following evidence of metastasis yet before the initiation of therapy. The significant improvement in prognosis in terms of longer OS and PFS for patients treated with advanced therapies relative to ADT monotherapy must be considered when making treatment decisions, with the aim of improving clinical outcomes among patients with mCSPC and reducing the healthcare costs associated with progression to mCRPC.

Transparency

Author contributions

LM, FK, PL, and DP contributed to study conception and design, collection and assembly of data, and data analysis and interpretation. DRK, IK, EM, and DJG contributed to study conception and design, data analysis and interpretation. All authors reviewed and approved the final content of this manuscript.

Reviewer disclosures statement

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have received an honorarium from JME for their review work but have no other relevant financial relationships to disclose.

Previous presentations

Part of the material in this manuscript was presented at the Annual American Society of Clinical Oncology Genitourinary Cancers Symposium held January 25-27, 2024 in San Francisco, CA as a poster presentation.

Data transparency

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary information files.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (16.3 KB)Acknowledgements

Medical writing assistance was provided by Loraine Georgy, PhD, MWC, an employee of Analysis Group, Inc., a consulting company that has provided paid consulting services to Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC, a Johnson & Johnson company, which funded the development and conduct of this study and manuscript.

Declaration of financial interests

DRK is an assistant professor at Duke University School of Medicine and reports the following in the past 24 months: Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC, a Johnson & Johnson company (consultancy). IK is an employee of Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC, a Johnson & Johnson company and stockholder of Johnson & Johnson. At the time of this study, EM was an employee of Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC, a Johnson & Johnson company and stockholder of Johnson & Johnson. LM, FK, PL, and DP are employees of Analysis Group, Inc., a consulting company that has provided paid consulting services to Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC, a Johnson & Johnson company, which funded the development and conduct of this study and manuscript. DJG is a professor at Duke University School of Medicine and reports the following in the past 24 months: has acted in a leadership role for Capio Biosciences; has acted as a paid consultant for and/or as a member of the advisory boards of Bayer, Exelixis, Pfizer, Sanofi, Astellas Pharma, Innocrin Pharma, Bristol Myers Squibb, Genentech, Janssen, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Myovant Sciences, AstraZeneca, Michael J. Hennessy Associates, Constellation Pharmaceuticals, Physicians’ Education Resource, Propella Therapeutics, RevHealth, and xCures; has been a member of the speakers’ bureau of Sanofi, Bayer, and Exelixis; has received honoraria from Sanofi, Bayer, Exelixis, EMD Serono, OncLive, Pfizer, UroToday, Acceleron Pharma, American Association for Cancer Research, Axess Oncology, Janssen Oncology, and Millennium Medical Publishing; has received research funding from Exelixis, Janssen Oncology, Novartis, Pfizer, Astellas Pharma, Bristol Myers Squibb, Acerta Pharma, Bayer, Dendreon, Innocrin Pharma, Calithera Biosciences, and Sanofi/Aventis; and has received other research support (travel, accommodations, expenses) from Bayer, Exelixis, Merck, Pfizer, Sanofi, Janssen Oncology, and UroToday.

Data availability statement

Data that support the findings of this study were used under license from Flatiron Health, Inc. and Komodo Health Solutions. Restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which are not publicly available and cannot be shared. The data are available through request made directly to the data vendor, subject to the data vendor’s requirements for data access.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Wagle NS, et al. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J Clin. 2023;73(1):17–48. doi: 10.3322/caac.21763.

- Mosillo C, Iacovelli R, Ciccarese C, et al. De novo metastatic castration sensitive prostate cancer: state of art and future perspectives. Cancer Treat Rev. 2018;70:67–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2018.08.005.

- Siegel DA, O'Neil ME, Richards TB, et al. Prostate cancer incidence and survival, by stage and race/ethnicity - United States, 2001-2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(41):1473–1480. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6941a1.

- Scher HI, Solo K, Valant J, et al. Prevalence of prostate cancer clinical states and mortality in the United States: estimates using a dynamic progression model. PLoS One. 2015;10(10):e0139440. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0139440.

- American Cancer Society. Hormone Therapy for Prostate Cancer; 2021. Available from: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/prostate-cancer/treating/hormone-therapy.html.

- Pagliuca M, Buonerba C, Fizazi K, et al. The evolving systemic treatment landscape for patients with advanced prostate cancer. Drugs. 2019;79(4):381–400. doi: 10.1007/s40265-019-1060-5.

- Karantanos T, Corn PG, Thompson TC. Prostate cancer progression after androgen deprivation therapy: mechanisms of castrate resistance and novel therapeutic approaches. Oncogene. 2013;32(49):5501–5511. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.206.

- U.S. Food and Drug Adminsitration. FDA approves apalutamide for metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer 2019. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-approves-apalutamide-metastatic-castration-sensitive-prostate-cancer.

- U.S. Food and Drug Adminsitration. FDA approves abiraterone acetate in combination with prednisone for high-risk metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer 2018. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-approves-abiraterone-acetate-combination-prednisone-high-risk-metastatic-castration-sensitive.

- U.S. Food and Drug Adminsitration. FDA approves enzalutamide for metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer 2019. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-approves-enzalutamide-metastatic-castration-sensitive-prostate-cancer.

- de Bono JS, Logothetis CJ, Molina A, et al. Abiraterone and increased survival in metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(21):1995–2005. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1014618.

- Scher HI, Fizazi K, Saad F, et al. Increased survival with enzalutamide in prostate cancer after chemotherapy. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(13):1187–1197. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1207506.

- Crawford ED, Andriole G, Freedland SJ, et al. Evolving understanding and categorization of prostate cancer: preventing progression to metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: RADAR IV. Can J Urol. 2020;27(5):10352–10362.

- Ryan CJ, Ke X, Lafeuille MH, et al. Management of patients with metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer in the real-world setting in the United States. J Urol. 2021;206(6):1420–1429. doi: 10.1097/JU.0000000000002121.

- Freedland SJ, Sandin R, Sah J, et al. Treatment patterns and survival in metastatic castration‐sensitive prostate cancer in the US veterans health administration. Cancer Med. 2021;10(23):8570–8580. doi: 10.1002/cam4.4372.

- Devasia TP, Mariotto AB, Nyame YA, et al. Estimating the number of men living with metastatic prostate cancer in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2023;32(5):659–665. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-22-1038.

- Ma X, Long L, Moon S, et al. Comparison of population characteristics in real-world clinical oncology databases in the US: flatiron health, SEER, and NPCR. medRxiv. 2020. doi: 10.1101/2020.03.16.20037143.

- Birnbaum B, Nussbaum N, Seidl-Rathkopf K, et al. Model-assisted cohort selection with bias analysis for generating large-scale cohorts from the EHR for oncology research. arXiv:200109765. 2020 doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2001.09765.

- Komodo Health Solutions. Imputing allowed amounts development and validation of an encounter-level allowed amount imputation model 2023. Available from: https://www.komodohealth.com/hubfs/2023/Komodo_Imputing_Allowed_Amounts_White_Paper.pdf.

- Datavant. Overview of Datavant’s de-identification and linking technology for structured data 2020. Available from: https://datavant.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/White-Paper_-De-Identifying-and-Linking-Structured-Data_updated-3-10-2020.pdf.

- US Department of Health and Human Services. 45 CFR 46: pre-2018 requirements 2021 June 23, 2023. Available from: https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/regulations-and-policy/regulations/45-cfr-46/index.html#46.101.

- Ke X, Lafeuille M-H, Romdhani H, et al. Healthcare resource use (HRU) in men with metastatic castration sensitive prostate cancer (mCSPC) receiving androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) only or no treatment in the United States (US). J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(15_suppl):e19138–e19138. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2020.38.15_suppl.e19138.

- Ellinger J, Alajati A, Kubatka P, et al. Prostate cancer treatment costs increase more rapidly than for any other cancer-how to reverse the trend? EPMA J. 2022;13(1):1–7. doi: 10.1007/s13167-022-00276-3.

- Olsen TA, Filson CP, Richards TB, et al. The cost of metastatic prostate cancer in the United States. Urol Pract. 2023;10(1):41–47. doi: 10.1097/UPJ.0000000000000363.

- Reddy SR, Broder MS, Chang E, et al. Cost of cancer management by stage at diagnosis among medicare beneficiaries. Curr Med Res Opin. 2022;38(8):1285–1294. doi: 10.1080/03007995.2022.2047536.

- Trinh QD, Chaves LP, Feng Q, et al. The cost impact of disease progression to metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2022;28(5):544–554. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2022.28.5.544.

- Lowrance W, Dreicer R, Jarrard DF, et al. Updates to advanced prostate cancer: AUA/SUO guideline (2023). J Urol. 2023;209(6):1082–1090. doi: 10.1097/JU.0000000000003452.

- Crigna AT, Samec M, Koklesova L, et al. Cell-free nucleic acid patterns in disease prediction and monitoring-hype or hope? Epma J. 2020;11(4):603–627. doi: 10.1007/s13167-020-00226-x.

- Kucera R, Pecen L, Topolcan O, et al. Prostate cancer management: long-term beliefs, epidemic developments in the early twenty-first century and 3PM dimensional solutions. Epma J. 2020;11(3):399–418. doi: 10.1007/s13167-020-00214-1.

- James ND, de Bono JS, Spears MR, et al. Abiraterone for prostate cancer not previously treated with hormone therapy. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(4):338–351. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1702900.

- Fizazi K, Tran N, Fein L, et al. Abiraterone plus prednisone in metastatic, castration-sensitive prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(4):352–360. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1704174.

- Chi KN, Agarwal N, Bjartell A, et al. Apalutamide for metastatic, castration-sensitive prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(1):13–24. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1903307.

- Armstrong AJ, Azad AA, Iguchi T, et al. Improved survival with enzalutamide in patients with metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(15):1616–1622. doi: 10.1200/JCO.22.00193.

- Wenzel M, Preisser F, Hoeh B, et al. Impact of time to castration resistance on survival in metastatic hormone sensitive prostate cancer patients in the era of combination therapies. Front Oncol. 2021;11:659135. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.659135.

- Graham LS, Lin JK, Lage DE, et al. Management of prostate cancer in older adults. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2023;43:e390396. doi: 10.1200/EDBK_390396.

- Rebello RJ, Oing C, Knudsen KE, et al. Prostate cancer. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2021;7(1):9. doi: 10.1038/s41572-020-00243-0.

- Wu B, Li SS, Song J, et al. Total cost of care for castration-resistant prostate cancer in a commercially insured population and a medicare supplemental insured population. J Med Econ. 2020;23(1):54–63. doi: 10.1080/13696998.2019.1678171.

- Dovey Z, Mohamed N, Gharib Y, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on prostate cancer management: guidelines for urologists. Eur Urol Open Sci. 2020;20:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.euros.2020.05.005.