Abstract

Objective: To determine the prevalence of genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM) and urogynecological conditions associated with menopause, and to evaluate the impact of GSM on quality of life in a cohort of Spanish postmenopausal women.

Methods: Multicenter, cross-sectional, and observational study involving 430 women.

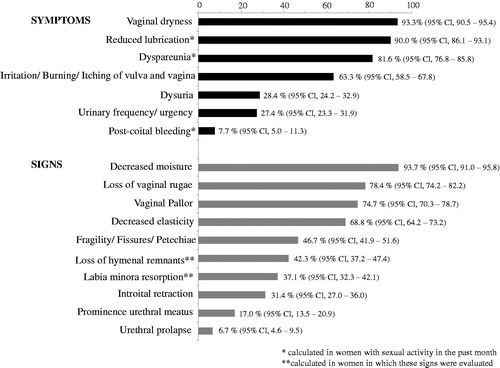

Results: The prevalence of GSM was 70%. GSM was diagnosed in 60.2% of women with no known diagnosis of vulvovaginal atrophy or GSM. Most prevalent symptoms were vaginal dryness (93.3%) and reduced lubrication with sexual activity (90.0%). Most prevalent signs were decreased moisture (93.7%) and loss of vaginal rugae (78.4%). GSM was significantly associated with stress or mixed urinary incontinence, overactive bladder, and vaginal prolapse. Symptoms showed a low-moderate impact on quality of life, mainly in sexual functioning and self-concept and body image.

Conclusions: The GSM is very prevalent in Spanish postmenopausal women, affecting up to 70% of those consulting the gynecologist. Despite the high prevalence of symptoms and signs and its impact on the women's well-being, GSM remains underdiagnosed and undertreated. Given its relationship with urogynecological conditions, it seems necessary to provide an adequate evaluation of postmenopausal women for identifying potential co-morbidities and providing most adequate treatments. An adequate management of GSM will contribute to an improvement in the quality of life of these women.

Introduction

One out of two perimenopausal and postmenopausal women experience, as a consequence of the reduction in estrogen and other sex steroids in the menopause, a collection of symptoms and signs that are associated with the novel proposed term ‘genitourinary syndrome of menopause’ (GSM)Citation1–4. The GSM implicates changes to the labia majora/minora, clitoris, vestibule/introitus, vagina, urethra and bladder. The main symptoms related with GSM include vaginal dryness, irritation/burning/itching of vulva or vagina, reduced lubrication with sexual activity, dyspareunia or discomfort with sexual activity, postcoital bleeding, dysuria, urinary frequency/urgency, and urge incontinenceCitation4. The main signs of GSM include decreased moisture, decreased elasticity, loss of vaginal rugae, vaginal pallor, tissue fragility/fissures/petechiae, introital retraction, prominence of urethral meatus, urethral prolapse, labia minora resorption, loss of hymenal remnants, and recurrent urinary tract infections. GSM has been proposed by the International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health and the North American Menopause SocietyCitation4 in an attempt to cover the full spectrum of symptoms and signs that occur during menopause; however, there is controversy in the medical community related to its accuracy, acceptability and practicalityCitation5. There are concerns that GSM encompasses not only symptoms and signs derived from estrogen deprivation but also some others derived from the natural process of agingCitation6. The fact that this general term might obscure the diagnosis of specific urogynecological pathologies and hamper the indication of the most appropriate therapies has also been addressed.

The prevalence of symptoms of GSM has been reported to vary greatly: between 27% and 55% for vaginal dryness; up to 40% to 77% for dyspareunia, and between 6% and 36% for urinary symptomsCitation7–11. These symptoms appear as a consequence of the vulvovaginal atrophy (VVA)Citation12. They are progressive and require, commonly, treatmentCitation13. Despite the high prevalence of symptoms, most postmenopausal women do not visit the gynecologist to consult symptomatology and available treatmentsCitation14,Citation15. Indeed, only 6–7% of postmenopausal women are treatedCitation2,Citation16. There are several available therapies to manage local symptoms, including hormonal (vaginal estrogens) and non-hormonal therapies (vaginal lubricants and moisturizers)Citation17–19.

On the other hand, symptoms of GSM have been shown to affect daily living activities, sexual health, and quality of life of postmenopausal womenCitation20,Citation21. Nevertheless, to date the information regarding the prevalence and impact of GSM on the daily life of these women is still limited, especially from Spain. Therefore, the main objectives of the GENISSE study were to determine the prevalence of GSM and its symptoms and signs, to evaluate the association of GSM with urogynecological problems of the menopause, and to evaluate the impact of GSM on the quality of life in a cohort of postmenopausal women from Spain.

Methods

Study design and participants

This multicenter, cross-sectional and observational study involved consecutive postmenopausal women visiting the gynecologist for any reason in September–October 2015. Gynecologists were providing health-care assistance in private consultations (95% of cases) or in public Spanish hospitals. Inclusion criteria to participate in the study were as follows: women aged between 30 and 75 years old; absence of menstruation since, at least, 1 year at the time of the visit; having no understanding, reading, or writing problems; and to have signed the informed consent. Exclusion criteria included women participating in any other clinical study, or those considered inadequate to participate in the study by the criteria of the investigator. Procedures were performed in accordance with guidelines established by the Declaration of Helsinki. The protocol was previously approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hospital Clínic de Barcelona (Spain) and Hospital Universitario Puerta de Hierro-Majadahonda, Madrid (Spain).

Study variables

The main aims of the study were to determine the prevalence of GSM and its impact on women’s quality of life. The diagnosis of GSM was established on the basis of genital and urinary symptoms or signs (at least two symptoms, or one symptom and one sign) that are referred as bothersome, and are associated with menopause and not accountable for by other pathologiesCitation4. During the visit to the gynecologist, women were asked about their gynecological history and the relevant medications they were taking. Patients referred their vaginal symptoms and underwent a physical examination to determine the presence of vaginal and vulvar signs. Evaluated genital symptoms were: vaginal dryness, irritation/burning/itching of vulva and vagina, reduced lubrication with sexual activity, dyspareunia or discomfort with sexual activity, and postcoital bleeding. Urinary symptoms were dysuria, urinary frequency/urgency, and urge incontinenceCitation4. Evaluated signs were decreased moisture, decreased elasticity, loss of vaginal rugae, vaginal pallor, tissue fragility/fissures/petechiae, introital retraction, prominence of urethral meatus, urethral prolapse, labia minora resorption, loss of hymenal remnants, and recurrent urinary tract infections. The presence and intensity of every symptom and sign were registered according to the following scale: 0 (no), 1 (mild), 2 (moderate), and 3 (severe)Citation22. The presence of other urogynecological pathologies, such as stress or mixed urinary incontinence, overactive bladder, recurrent urinary tract infections, or vaginal prolapse was also registered. The impact of genital symptoms on the quality of life was assessed by using the day-to-day impact of vaginal aging (DIVA) questionnaire. This questionnaire was completed by women who reported at least one vaginal symptom. This 23-item questionnaire consists of four domain scales: activities of daily living; emotional well-being; sexual functioning; and self-concept and body imageCitation23. For the sexual functioning scale, two separate scale versions were examined: a short version appropriate for all women regardless of sexual activity status, and a longer version appropriate only for sexually active women (considered when they had sexual activity in the last 4 weeks). Each item was scored from 0 to 4 (0 = not at all, 1 = a little bit, 2 = moderately, 3 = quite a bit, and 4 = extremely). Total scores for each domain scale were computed by calculating the average of scores for the corresponding individual items; higher scores denoted greater impact of vaginal symptoms.

Sample size and statistical analysis

Basing on literatureCitation1–4, the expected prevalence of GSM symptoms is 50%. The estimated number of women required to determine the prevalence, with a precision of 4.5%, and a bilateral 95% confidence interval (95% CI), was 475. Assuming 5% of missed data, the final number of women to be recruited was 500. Analyses of the data were primarily performed using descriptive statistical methods. Qualitative variables were expressed as absolute and relative frequencies (%), and the quantitative ones as the mean with the standard deviation (SD) or 95% CI. We evaluated the association between GSM diagnosis and presence of urogynecological disorders using Fisher's exact test. We also determined the magnitude of this association using the odds ratio (OR). We analyzed and compared the impact of vaginal symptoms on quality of life in women with GSM and without GSM using the non-parametric Wilcoxon test. Statistical significance was established with p < 0.05. For all statistical procedures, we used SAS version 9.3.

Results

Characteristics of the study population

From 472 postmenopausal women initially recruited, 430 were finally included in the study. The reasons for the exclusion of 42 women were as follows: six women were not menopausal and 36 did not complete the section of symptoms and signs in the case report form. The mean age of women was 58.1 years (SD 6.9 years). Their last menstruation was 9.1 years ago (SD 6.8 years). The cause of menopause was natural in 89.8% of women. A total of 72.1% had sexual activity in the last 4 weeks, and 92.1% indicated that their health was good, very good, or excellent. The main reasons for visiting the gynecologist were: regular gynecological control (58.8% of women); follow-up of a previously diagnosed pathology (10.2%); menopausal symptomatology (including hot flushes, insomnia, arthralgia/myalgia, or depressive symptoms, in 5.8%); symptoms or signs of VVA or GSM (15.3%); urinary incontinence (stress or mixed, 2.6%) or vaginal prolapse (2.3%). Previous diagnosis of VVA or GSM was present in 40% of women. A total of 24% of women had been previously diagnosed with any type of urinary incontinence; 9% had a diagnosis of urinary tract infections, and 9% had been previously diagnosed of vaginal prolapse.

Prevalence of GSM

The prevalence of GSM was 70% (95% CI 66–75%). GSM was diagnosed in 63.6% of women with no relevant previous gynecological pathology, and in 60.2% of women with no previous diagnosis of VVA or GSM. All women reported at least one genital and/or urinary symptom. Symptoms were considered bothersome to 71% of women. A total of 70.0% of women complained of bothersome genital symptoms, 38.4% of bothersome urinary symptoms, and 37% of bothersome genital and urinary symptoms.

The prevalence of symptoms and signs of GSM is shown in . The most prevalent symptoms were vaginal dryness (93.3%; 95% CI 90.5–95.4%) and, in sexually active women in the past 4 weeks (n = 310), reduced lubrication (90.0%; 95% CI 86.1–93.1%) and dyspareunia (81.6%; 95% CI 76.8–85.8%). The most prevalent signs were decreased moisture (93.7%; 95% CI 91.0–95.8%) loss of vaginal rugae (78.4%; 95% CI 74.2–82.2%) and vaginal pallor (74.7%; 95% CI 70.3–78.7%).

The intensity of main symptoms and signs of GSM is shown in . When present, genital symptoms were mostly moderate to severe: 67.9% (272/401) of women with vaginal dryness, 67.4% (188/279) with reduced lubrication, and 62.9% (159/253) with dyspareunia. Urinary symptoms, when present, were mostly mild to moderate: 100% of women with dysuria (n = 122) and 97.5% with urinary frequency (115/118). A total of 19% (76/401) of women reported severe vaginal dryness, 19% (49/253) severe dyspareunia, and 25% (70/279) severe reduced lubrication. The prevalence of genital symptoms in sexually active women (99.0%) was similar to that in non-sexually active (96.7%), whereas the prevalence of urinary symptoms was higher in non-sexually active women (53.3% vs. 38.4%).

Table 1. Intensity of main symptoms and signs of genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM). Data are given as n (%).

From women with no previous diagnosis of VVA or GSM (n = 254), 97.6% experienced genital symptoms, and 35.8% urinary symptoms. Moreover, 90.9%, 87.6% and 77.8% of these women with no previous diagnosis of VVA reported reduced vaginal dryness, decreased lubrication and dyspareunia, respectively. An important fraction of women with no previous diagnosis of VVA or GSM presented advanced symptoms: 45.7% with at least two moderate to severe symptoms, 25.6% with at least one severe symptom, and 10.2% with at least two severe symptoms.

We analyzed the prevalence of GSM and its symptoms and signs by subgroups, categorized by time from menopause. In women with up to 5 years from their last menstrual period, the prevalence of GSM was 65%, while in women with more than 5 years of menopause, the prevalence was 74%. The prevalence of individual symptoms and signs and their intensities in these two subgroups of women is shown in .

Table 2. Prevalence and intensity of symptoms and signs of genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM) in women with up to 5 years, and more than 5 years of menopause. Data are given as n (%). Percentages of mild, moderate and severe are calculated from the total number of patients with the symptom or the sign.

Association of GSM with urogynecological pathologies

The prevalence of previous diagnosis of premalignant or malignant pathologies of breast, endometrium, or cervix was not significantly different between women with and without GSM. The prevalence of GSM symptoms was higher in women with urogynecological disorders. Urinary urgency/frequency was reported by 61.0% (50/82) of women with stress or mixed incontinence, and by 36.8% (14/38) with recurrent urinary tract infections. Similarly, dysuria was indicated by 76.3% (29/38) of women with recurrent urinary tract infections.

The development of GSM was significantly associated with the presence of urogynecological pathologies: stress incontinence (OR 3.30; 95% CI 1.52–7.15; p = 0.001); mixed incontinence (OR 8.43; 95% CI 1.12–63.69; p = 0.01); overactive bladder (OR 18.44; 95% CI 1.11–307.50; p = 0.002); and vaginal prolapse (p = 0.024). The association of GSM with these urogynecological pathologies is shown in . The prevalence of GSM was higher in women who had received any previous treatment (during the previous 15 days, 1 and 3 months before inclusion), especially vaginal estrogens. Up to 81.8% (121/303) and 76.3% (122/253) of recent users of moisturizers and lubricants presented with GSM.

Table 3. Association of genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM) with urogynecological pathologies. Data are given as n (%).

Impact of GSM on quality of life

Vaginal symptoms barely impacted on activities of daily living and emotional well-being of menopausal women, as shown in the DIVA questionnaire (mean score = 0.7 for both domain scales). However, these symptoms showed a low to moderate impact on the remaining domain scales. They impacted slightly on women’s self-concept and body image (mean score = 1.4) and moderately on sexual functioning (mean scores 1.7, short version, and 1.8, long version in sexually active women). On the other hand, significant differences in DIVA questionnaire responses were found between women with and without GSM (p < 0.001 for all domains). Vaginal symptoms had a marked impact on sexual functioning in sexually active women (score 2.0 in women with GSM and 1.1 in women without GSM; p < 0.001; ).

Table 4. Impact of vaginal symptoms on the quality of life of postmenopausal women (DIVA questionnaire). Data are given as mean ± standard deviation.

Discussion

The novel proposed term GSM denotes a set of bothersome symptoms and signs associated with the estrogen decrease during the menopauseCitation4. These genitourinary symptoms affect approximately 50% of midlife and older womenCitation2,Citation21. In our study, the prevalence of GSM in women who visited the gynecologist was 70%, despite it had been previously diagnosed in 39.8% of women. The discrepancy between previous and recent diagnosis, although it could be partially explained by the different criteria considered for the diagnosis, highlights the situation of underdiagnosis of this condition. An adequate anamnesis at the time of the visit to the gynecologist could probably detect cases that, otherwise, would be unnoticed. The high prevalence of GSM in our study is consistent with the recent Italian AGATA study, in which 64.7% of women at 1 year and 84.2% at 6 years after menopause had developed GSMCitation24. Similarly, the GENISSE study also evidenced that the prevalence of GSM was higher in the group of women with more than 5 years of menopause (74%) than in those with 5 years or less of menopause (62%). Symptoms and signs were more prevalent and more severe in women with more than 5 years of menopause than in women with less time of menopause, which can be explained by the progressive nature of the condition and the impact of aging.

Vaginal dryness and dyspareunia have been reported to be particularly prevalent among perimenopausal and postmenopausal womenCitation12,Citation25,Citation26. Although the prevalence of vaginal dryness varies, it has been shown to be the most frequently referred symptom, in up to 57% of postmenopausal womenCitation15. Dyspareunia affects approximately 40% of midlife womenCitation11. In REVIVE, a survey that involved 3046 postmenopausal US women with VVA, the most frequent symptoms were vaginal dryness (55% of women), dyspareunia (44%), and irritation (37%)Citation27. The European REVIVE study, involving 3768 postmenopausal women from Italy, Germany, Spain and UK, showed that vaginal dryness was the most common VVA symptom (70%), followed by vaginal irritation (32.7%), and dyspareunia (29.0%)Citation28. In the Italian AGATA study, involving 913 postmenopausal women, 100% of women with a diagnosis of GSM had vaginal dryness, 77.6% dyspareunia, 56.9% burning, 56.6% itching, and 36.1% dysuriaCitation24. In another survey, of 4201 postmenopausal women from seven European countries (Belgium, France, Germany, Netherlands, Spain, Switzerland and UK), the overall prevalence of vaginal pain/dryness was 29%, from 19% in Germany, 33% in France, and to 40% in SpainCitation29. In our cohort of postmenopausal women, the prevalence of GSM symptoms, such as vaginal dryness (93.3%), reduced lubrication (90.0%), and dyspareunia (81.6%), was higher than in the literature. A possible explanation for the discrepancy in the prevalence of symptoms may derive from differential characteristics of women among studies, or the different populations or clinical settings involved. Furthermore, in our study the diagnosis of GSM was established with two symptoms, or one symptom and one sign. This choice was arbitrary, as it is not defined in the GSM paperCitation4, and derived to the minimum level of interpretation of the definition. Due to different criteria in defining the problem, comparisons with other studies should be performed with cautionCitation26,Citation29,Citation30. Much more in concordance with the present study are the results obtained in another study carried out in Spain that showed vaginal dryness and dyspareunia as the most frequently reported symptoms of VVA with substantially higher prevalenceCitation17.

Despite vaginal dryness being one of the symptoms more frequently reported by postmenopausal women and frequently requiring treatment, only 25% of women seek medical assistanceCitation13. A survey of 2045 British postmenopausal women revealed that 42% of them considered that seeking treatment for vaginal dryness was not important, 14% considered that it was ‘something to put up with’, and 13% reported that it was ‘too embarrassing to seek for help’Citation31. Moreover, as demonstrated in the VIVA survey, involving 3520 postmenopausal women from the UK, US, Canada, Sweden, Denmark, Finland and Norway, there is a low understanding of vaginal atrophy and associated symptomsCitation32. A very small percentage of these women (4%) attributed symptoms to vaginal atrophy, and 63% failed to define it as a chronic condition. Therefore, from a clinical perspective, clinicians should be aware of the importance of identifying symptoms and signs of GSM during routine visits of postmenopausal women in order to reveal this hidden condition that requires adequate treatment.

The co-existence of GSM with urogynecological pathologies has also been reported to be very frequent in postmenopausal womenCitation33–35. In concordance with the literature, in our study GSM was significantly associated with stress and mixed incontinence, overactive bladder, and vaginal prolapse. On the contrary, an association between GSM and urinary tract infections could not be demonstrated as the analysis almost reached the significance threshold (p = 0.062). Nevertheless, it might be speculated that an association could exist as it is plausible and has been demonstrated previously by many othersCitation4,Citation30,Citation36. The correlation between GSM and urogynecological pathologies highlights the need for an adequate evaluation of postmenopausal women to identify potential co-morbidities and provide effective treatments.

In our cohort of postmenopausal women, 30% of the women with GSM were not receiving any treatment for symptomatology, indicating the existence of an important group of affected postmenopausal women who are not managed properly. Also to note, a great majority of women who had received lubricants and/or moisturizing products suffered from vaginal dryness or dyspareunia.

The GSM has also been shown to produce an adverse emotional and physical impact on postmenopausal womenCitation37. Besides these studies provide valuable information on the impact of GSM symptoms on sexual activity, little is known about the impact on multiple dimensions of functioning and well-being in the daily living of menopausal women. Results from our study demonstrate that genital symptoms have little impact on activities of daily living of women and emotional well-being. The higher reported impact (moderate) was on sexual functioning. Moreover, the impact of vaginal symptoms on the quality of life in women with diagnosed GSM was significantly higher than in women without it. Again, an appropriate diagnosis and management of GSM become of great importance to maintain the well-being and quality of life of these women.

One limitation of this study derives from the fact that it has not been performed in the general population. Women attending gynecological outpatient services may be at higher risk for GSM than the general population, even if the reason for presenting to the gynecologist was a routine gynecological control. Another limitation relates to the ethnical homogeneity of our population, making results not applicable to other ethnicities. An important weakness derives from the fact that this investigation determined GSM according to an updated broader definition, considering criteria involving patient-reported genital and urinary symptoms, and urogenital signs identified by the gynecologist, some of them unspecificCitation4. The criteria to define GSM derived from the interpretation of a vague definition that may have resulted in overestimation of the problem. It could be argued then that a more specific and higher number of symptoms or signs to define the GSM should be considered to provide specificity in the diagnosis and avoid unnecessary demand for treatments for atrophy. Finally, as no cases of vulvodynia or lichen were detected, this possible underestimation of vulvar disease that would have been needed for a correct differential diagnosis of GSM could be another limitation of the study. In light of the present results, it is essential that gynecologists and every health professional involved in the management of these postmenopausal women provide an adequate anamnesis and physical examination to identify symptoms and signs of GSM. Furthermore, they should routinely inform perimenopausal and postmenopausal women about GSM symptoms.

Conclusions

GSM is a very prevalent condition among postmenopausal women in Spain, affecting up to 70% of those visiting a gynecologist. Despite the high prevalence of symptoms and signs, and its impact on quality of life (mainly on sexual functioning and self-concept and body image), GSM is underdiagnosed and undertreated. As GSM impacts on women's well-being, an adequate diagnosis and management of this condition will contribute to improve the quality of life of these women. In addition, given its relationship with certain urogynecological pathologies, it seems necessary to provide an adequate assessment of the postmenopausal woman for identifying potential co-morbidities and provide the most adequate treatments.

Authors' note

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. All authors approved the final manuscript. Ethical approval was provided by the Ethics Committee of the Hospital Clínic de Barcelona (Spain) and by the Hospital Universitario Puerta de Hierro-Majadahonda, Madrid (Spain).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. ITF Research Pharma personnel work in the Medical Department that sponsored the study.

Acknowledgements

Participants in the GENISSE study were as follows: E. M. Contreras (Cádiz), R. León (Cádiz), C. González (Sevilla), M. I. Massé (Sevilla), E. Flores (Sevilla), R. Rodríguez (Orense), I. Lago (Pontevedra), A. M. González (Vigo), O. Valenzuela (Vigo), M. Villegas (Barcelona), A. Jordán (Barcelona), B. Meneses (Barcelona), I. Núñez (Barcelona), C. J. Pace (Barcelona), P. Beroiz (Barcelona), A. Martí (Barcelona), J. G. Hernández (Santa Cruz de Tenerife), L. González (Santa Cruz de Tenerife), M. Muñoz (Barcelona), J. R. Méndez (Barcelona), S. González (Barcelona), V. Rayo (Barcelona), M. Amorós (Barcelona), J. R. Rodríguez (Barcelona), C. Pedrosa (Granada), R. Herrera (Málaga), J. García (Málaga), R. Laza (Málaga), M. C. Rodríguez (Granada), A. Jarque (León), J. L. Solís (Oviedo), L. Vior (Oviedo), C. M. Rodríguez (Asturias), J. V. Carmona (Valencia), J. Server (Valencia), M. González (Valencia), L. J. Matute (Valencia), F. Ridocci (Valencia), R. V. García (Valencia), J. Moro (Salamanca), C. E. García (Zamora), M. J. Velasco (Ávila), A. Martín (Burgos), J. I. González (Valladolid), J. Velasco (Valladolid), C. Oliva (Castellón), A. Estrada (Valencia), D. Mares (Valencia), F. Ruiz (Valencia), C. Vignardi (Madrid), M. A. Martínez (Madrid), J. Lázaro (Madrid), A. Palacín (Madrid), L. San Frutos (Madrid), J. A. Navas (Córdoba), J. J. Hijona (Jaén), E. Velasco (Córdoba), M. Pérez (Lugo), M. J. Carballo (La Coruña), C. González (La Coruña), G. Tejada (Albacete), L. Sánchez (Ciudad Real), C. Martín (Toledo), M. Rey (Islas Baleares), V. H. Chávez (Islas Baleares), M. C. González (Madrid), A. R. Masero (Madrid), I. Ramírez (Madrid), C. Martín-Ondarza (Madrid), E. Vizcaíno (Madrid), N. Ros (Tarragona), A. Calvo (Lérida), J. C. Riera (Gerona), J. Salinas (Tarragona), F. R. Blanco (Badajoz), J. A. Sánchez (Badajoz), A. Monrobel (Cáceres), S. Escudero (La Rioja), A. López (Huesca), M. P. del Tiempo (Zaragoza), C. J. Elorriaga (Zaragoza), C. Ceballos (Cantabria), J. Oraa (Vizcaya), F. Mozo (Vizcaya), B. Otero (Vizcaya), T. M. Diaz (Vizcaya), S. Andreu (Madrid), L. Almarza (Madrid), R. Rodríguez (Guadalajara), M. Puch (Madrid), A. Hernández (Madrid), J. de la Fuente (Madrid), M. Ferrero (Barcelona), A. Reus (Barcelona), M. Guinot (Barcelona), M. Muñoz (Barcelona), A. Bernad (Barcelona), A. Torrent (Barcelona), V. Turrado (Barcelona), I. Etxabe (Guipúzcoa), I. Fernández (Navarra), M. Martínez (Álava), M. C. Castro (Murcia), J. Rodríguez (Alicante), C. González (Alicante), V. M. Lago (Murcia), R. Lorente (Alicante), M. A. Nieto (Las Palmas), M. Sosa (Las Palmas), M. Montero (Huelva), M. M. Falcón (Sevilla), A. Polo (Sevilla), S. Cruz (Madrid), M. Rius (Barcelona).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Castelo-Branco C, Cancelo MJ, Villero J, et al. Management of post-menopausal vaginal atrophy and atrophic vaginitis. Maturitas 2005;52:46–52

- MacBride MB, Rhodes DJ, Shuster LT. Vulvovaginal atrophy. Mayo Clin Proc 2010;85:87–94

- Nappi RE, Palacios S. Impact of vulvovaginal atrophy on sexual health and quality of life at postmenopause. Climacteric 2014;17:3–9

- Portman DJ, Gass ML. Vulvovaginal atrophy terminology consensus conference panel. Genitourinary syndrome of menopause: new terminology for vulvovaginal atrophy from the international society for the study of women’s sexual health and the North American Menopause Society. Climacteric 2014;17:557–63

- Vieira-Baptista P, Marchitelli C, Haefner HK, Donders G, Pérez-López F. Deconstructing the genitourinary syndrome of menopause. Int Urogynecol J 2017;28:675–9

- Palacios S, Castelo-Branco C, Currie H, et al. Update on management of genitourinary syndrome of menopause: a practical guide. Maturitas 2015;82:308–13

- Van Geelen JM, van de Weijer PH, Arnolds HT. Urogenital symptoms and resulting discomfort in non-institutionalized Dutch women aged 50-75 years. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic J 2000;11:9–14

- Pastore LM, Carter RA, Hulka BS, et al. Self-reported urogenital symptoms in postmenopausal women: women’s health initiative. Maturitas 2004;49:292–303

- Jackson SL, Boyko EJ, Scholes D, et al. Predictors of urinary tract infection after menopause: a prospective study. Am J Med 2004;117:903–11

- Oskay UY, Beji NK, Yalcin O. A study on urogenital complaints of postmenopausal women aged 50 and over. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2005;84:72–8

- Valadares AL, Pinto-Neto AM, Conde DM, et al. A population-based study of dyspareunia in a cohort of middle-aged Brazilian women. Menopause 2008;15:1184–90

- Edwards D, Panay N. Treating vulvovaginal atrophy/genitourinary syndrome of menopause: how important is vaginal lubricant and moisturizer composition? Climacteric 2016;19:151–61

- Sturdee DW, Panay N. International Menopause Society Writing Group. Recommendations for the management of postmenopausal vaginal atrophy. Climacteric 2010;13:509–22

- Cardozo L, Bachmann G, McClish D, et al. Meta-analysis of estrogen therapy in the management of urogenital atrophy in postmenopausal women: second report of the hormones and urogenital therapy committee. Obstet Gynecol 1998;92:722–7

- Palacios S. Managing urogenital atrophy. Maturitas 2009;63:315–18

- Prairie BA, Klein-Patel M, Lee M, et al. What midlife women want from gynecologists: a survey of patients in specialty and private practices. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2014;23:513–18

- Cano A, Estévez J, Usandizaga R, et al. The therapeutic effect of a new ultralow concentration estriol gel formulation (0.005% estriol vaginal gel) on symptoms and signs of postmenopausal vaginal atrophy: results from. a Pivotal Phase III Study. Menopause 2012;19:1130–9

- Goldstein I, Dicks B, Kim NN, et al. Multidisciplinary overview of vaginal atrophy and associated genitourinary symptoms in postmenopausal women. Sex Med 2013;1:44–53

- Rahn DD, Carberry C, Sanses TV, et al. Vaginal estrogen for genitourinary syndrome of menopause: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol 2014;124:1147–56

- Nappi RE, Kokot-Kierepa M. Women’s voices in the menopause: results from an international survey on vaginal atrophy. Maturitas 2010;67:233–8

- Parish SJ, Nappi RE, Krychman ML, et al. Impact of vulvovaginal health on postmenopausal women: a review of surveys on symptoms of vulvovaginal atrophy. Int J Womens Health 2013;5:437–47

- Guidance for Industry [webpage on the Internet]. Estrogen and estrogen/progestin drug products to treat vasomotor symptoms and vulvar and vaginal atrophy symptoms – Recommendations for Clinical Evaluation. Food and Drug Administration; 2003. Available from: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/drugs/guidancecomplianceregulatory-information/guidances/ucm071643.pdf [last accessed 16 Oct 2017]

- Huang AJ, Gregorich SE, Kuppermann M, et al. Day-to-day impact of vaginal aging questionnaire: a multidimensional measure of the impact of vaginal symptoms on functioning and well-being in postmenopausal women. Menopause 2015;22:144–54

- Palma F, Volpe A, Villa P, et al. Vaginal atrophy of women in postmenopause. Results from a multicentric observational study: the AGATA study. Maturitas 2016;83:40–4

- Leiblum SR, Hayes RD, Wanser RA, et al. Vaginal dryness: a comparison of prevalence and interventions in 11 countries. J Sex Med 2009;6:2425–33

- Kim HK, Kang SY, Chung YJ, et al. The recent review of the genitourinary syndrome of menopause. J Menopausal Med 2015;21:65–71

- Kingsberg SA, Wysocki S, Magnus L, et al. Vulvar and vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women: findings from the REVIVE (Real women’s Views of treatment options for menopausal vaginal changes) survey. J Sex Med 2013;10:1790–9

- Nappi RE, Palacios S, Panay N, et al. Vulvar and vaginal atrophy in four European countries: evidence from the European REVIVE Survey. Climacteric 2016;19:188–97

- Genazzani AR, Schneider HPG, Panay N, et al. The European menopause survey 2005: Women’s perceptions on the menopause and postmenopause hormone therapy. Gynecol Endocrinol 2006;22:369–75

- Grabe M, Bartoletti R, Bjerklund-Johansen TE, et al. Guidelines on urological infections, 2014. Available from: https://uroweb.org/wp-content/uploads/19-Urological-infections_LR.pdf

- Barlow DH, Cardozo LD, Francis RM, et al. Urogenital ageing and its effect on sexual health in older British women. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1997;104:87–91

- Nappi RE, Kokot-Kierepa M. Vaginal health: insights, views & attitudes (VIVA) - results from an international survey. Climacteric 2012;15:36–44

- Iosif CS, Bekassy Z. Prevalence of genito-urinary symptoms in the late menopause. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 1984;63:257–60

- Molander U, Milsom I, Ekelund P, et al. An epidemiological study of urinary incontinence and related urogenital symptoms in elderly women. Maturitas 1990;12:51–60

- Robinson D, Cardozo L. The pathophysiology and management of postmenopausal urogenital oestrogen deficiency. J Br Menopause Soc 2001;7:67–73

- Kodner CM, Thomas Gupton EK. Recurrent urinary tract infections in women: diagnosis and management. Am Fam Physician 2010;82:638–43

- Nappi RE, Kingsberg S, Maamari R, et al. The CLOSER (CLarifying Vaginal Atrophy’s Impact On SEx and Relationships) survey: implications of vaginal discomfort in postmenopausal women and in male partners. J Sex Med 2013;10:2232–41