Abstract

Objective

The CLOSER (CLarifying Vaginal Atrophy’s Impact On SEx and Relationships) survey investigated how postmenopausal vaginal atrophy (VA) affects relationships between Brazilian women and male partners.

Methods

Postmenopausal women (age 55–65 years) with VA, and male partners of women with the condition, completed an online survey on the impact of VA and local estrogen treatment on intimacy and relationships.

Results

A total of 360 women and 352 men from Brazil were included. Women (83%) and men (91%) reported that they were comfortable discussing VA with their partners. Women’s key source of information on VA was health-care providers (HCPs), but 44% felt that not enough information is available. VA caused 70% of women to avoid sexual intimacy and resulted in less satisfying sex. VA had a negative impact on women’s feelings and self-esteem. Women (76%) and men (70%) both reported that treatment with vaginal estrogen improved their sexual relationship, primarily by alleviating women’s pain during sex. Women (56%) and men (59%) felt closer to each other after treatment.

Conclusions

VA had a negative impact on sexual relationships for both women and men in Brazil, and reduced women’s self-confidence. Vaginal hormone therapy improved couples’ sexual relationships. A proactive attitude of HCPs is essential to educate women on VA and the potential benefits of treatment.

巴西绝经后阴道不适对性和两性关系的影响:CLOSER调查 摘要

目的:CLOSER(阐明阴道萎缩对性和关系的影响)调查研究了绝经后阴道萎缩(VA)如何影响巴西女性与其男性伴侣之间的关系。

方法:患VA的绝经后女性(年龄55-65岁)及这类女性的男性伴侣, 完成了一项关于VA和局部雌激素治疗对性行为和性关系影响的线上调查。

结果:共纳入来自巴西的360名女性和352名男性。女性(83%)和男性(91%)报告说, 他们很乐意与伴侣讨论VA。女性对于VA的主要信息来源是医疗保健人员(HCPs), 但44%的人认为无法获取到足够的信息。VA导致70%的女性避免性亲密, 并导致性满意度下降。VA对女性的感受和自尊有负面影响。女性(76%)和男性(70%)都报告说, 阴道雌激素治疗改善了他们的性关系, 主要是通过减轻女性在性交过程中的疼痛。治疗后, 女性(56%)和男性(59%)感觉关系更亲密。

结论:VA对巴西男性和女性的性关系都有负面影响, 降低了女性的自信。阴道激素疗法改善了夫妻的性关系。HCPs的积极主动对于进行VA及其治疗的潜在益处的女性教育至关重要

Introduction

Vaginal atrophy (VA) with its associated symptoms, such as dryness, itching, burning and dyspareunia, is common in postmenopausal women and is a key component of the genitourinary syndrome of menopause [Citation1,Citation2]. However, VA is frequently under-reported, in part because vaginal health is still considered a taboo subject, with some differences across countries [Citation3]. Many health-care providers (HCPs) do not approach this issue with their patients and many women are not aware that therapy is available [Citation4]. The lack of discussion translates into poor access to effective treatments [Citation5], with VA symptoms managed only when they are already severe [Citation6].

The VIVA (Vaginal Health: Insights, Views, and Attitudes) survey of postmenopausal women in seven countries in Europe and North America showed that VA has a detrimental impact on women’s quality of life, negatively affecting their self-esteem and intimacy with their partner [Citation4,Citation7]. The VIVA survey was subsequently conducted in Latin America (VIVA-LATAM) and showed that, as in other regions, postmenopausal VA was under-recognized and undertreated [Citation8]. Recently published data from the VIVA-LATAM survey in Brazil, the most populous Latin American country, suggested that Brazilian postmenopausal women could also benefit from increased awareness of VA and available treatment options [Citation9].

Building on the results of VIVA, the CLOSER (CLarifying Vaginal Atrophy’s Impact On SEx and Relationships) survey focused on how vaginal discomfort affects women’s relationships with their male partners. Results from the CLOSER survey of 4100 postmenopausal women and 4100 male partners, in countries in Europe and North America as well as South Africa, have been published, underlining the importance of addressing VA in the context of a relationship [Citation10–14]. As responses to this type of survey may be influenced by cultural background, it is important to publish the results from different countries. Here, we report results from the CLOSER survey conducted in Brazil.

Methods

The survey was undertaken in Brazil by Edelman Intelligence (formerly StrategyOne) from 14 September to 1 October 2018. Details of the CLOSER methodology have been published previously [Citation12], and are reviewed briefly here. As attitudes and behaviors were surveyed, but no interventions administered, formal medical ethics approval was not sought. The study was performed in accordance with the rules and regulations of the Market Research Society in the UK.

Inclusion criteria were as follows for women: age 55–65 years, married or cohabiting, having ceased menstruating for ≥1 year and having experienced vaginal discomfort (defined as the occurrence of any of the following: dryness, itching, burning or soreness of the vagina; bleeding during intercourse; pain during urination or pain in the vagina in connection with touching and/or intercourse). The men enrolled in the study were not necessarily in a relationship with the same women who participated in the survey. However, all men were in a relationship with a postmenopausal woman aged 55–65 years who fulfilled the inclusion criteria.

Women were recruited via a panel of individuals with Internet access who had opted to participate in surveys. Men were recruited by the female respondents, who asked them to complete the male questionnaire, or from a panel of men who opted to participate in surveys. There was no financial incentive for participation. Enrollment was stratified to ensure that women from all parts of Brazil were enrolled.

Respondents were asked to complete an online structured questionnaire (abbreviated in Supplementary Table 1), which covered demographic data as well as information on menopausal symptoms, communication about vaginal discomfort, the impact of vaginal discomfort on intimacy and relationships, and the impact of local estrogen therapy on women’s sexual relationships and self-esteem. The term ‘vaginal discomfort’, rather than VA, was used throughout the questionnaire in order to be well understood by the respondents. In reporting the results, the term ‘doctors’ includes gynecologists, and the term ‘HCPs’ covers doctors, gynecologists and pharmacists. Data were summarized descriptively; no statistical tests were undertaken.

Results

Demographic characteristics of participants and menopausal symptoms

Responses were obtained from 360 postmenopausal women and 352 male partners of postmenopausal women. Demographic characteristics and an overview of menopausal symptoms are presented in . Approximately two-thirds of women and men were aged 55–60 years. Time since the last menstrual cycle was >5 years for 65% of women and 55% of the female partners of male respondents. Overall, 98% of women had experienced symptoms of the menopause – most frequently vaginal dryness, hot flushes, weight gain and mood swings.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of participants and menopausal symptoms.

Talking about vaginal discomfort

Among women, 81% told their partner when they first experienced symptoms of vaginal discomfort; among men, 97% reported that they wanted their partner to talk about vaginal discomfort if they were experiencing it. High proportions of the responding women (83%) and men (91%) reported feeling comfortable talking to their partner about vaginal discomfort; however, 30% of the women also said they would rather try self-treatment first to ease the symptoms, and 24% also said they would not bring it up as it is a natural part of aging. Respondents were prepared to discuss their or their partners’ vaginal discomfort with HCPs (women 92%, men 74%) and also with friends or family (women 54%, men 20%).

Importantly, 44% of women felt there is not enough information available about the symptoms and treatment of vaginal discomfort. In order to obtain relevant information, women turned to the following (women could choose more than one source): HCPs 95%, online information 70% and print materials 29%.

Physical and emotional impact of vaginal discomfort

Vaginal discomfort had a considerable negative impact on a woman’s physical relationship with her partner. Many women (70%) admitted that they always or sometimes avoided being intimate because of vaginal discomfort, and 75% of men perceived that their partner behaved this way (Supplementary Table 2). The main reason for avoiding intimacy was the worry that sex would be painful.

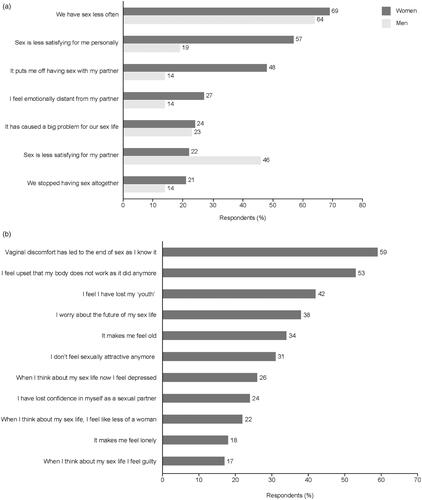

The most frequently reported effects of vaginal discomfort on sexual relationships are shown in . Women and men both reported the top two effects as a lower frequency of sex and sex being less satisfying for the woman.

Figure 1. Impact of vaginal discomfort on (a) sexual relationships and (b) women’s feelings and self-esteem. Note: Top seven responses are shown in part (a).

Vaginal discomfort had a negative impact on women at an emotional level. Women worried that the condition would never go away and would have a long-term impact on their relationship (40%) and on their future sex life (38%).

The effects of vaginal discomfort on women’s feelings and self-esteem are shown in . These included feeling that vaginal discomfort had led to the end of sex as they knew it (59%); and a loss of confidence and self-esteem, with 31% not feeling sexually attractive any more, 24% losing confidence in themselves as a sexual partner and 22% feeling less of a woman in regard to their sex life. Loss of confidence became evident to women’s partners, with 30% saying that their partner avoided being intimate because vaginal discomfort had an impact on their self-esteem. Vaginal discomfort was also a reminder to women about getting older ().

Some women felt lonely because of having vaginal discomfort: 27% felt distant from their partners, but only 14% of men thought that their partner felt this ().

Impact of vaginal estrogen therapy on women’s sexual relationships and self-esteem

Most women had tried some form of treatment (84% as reported by women, 74% as reported by men). Respondents were asked to list all treatments they had tried, whether in the past or whether they were continuing to use them. The most popular treatment reported by the respondents was over-the-counter medication, such as lubricating gels and creams (54%), followed by hormone-based medication (47%) in the form of vaginal creams, tablets and rings (distinct from systemic hormone replacement therapy). Only 22% had used hormone replacement therapy (Supplementary Table 3). Women who used vaginal hormone therapies (n = 168) reported that doctors were their main source of information on treatment (94%), followed by their own research (8%) and pharmacies (4%).

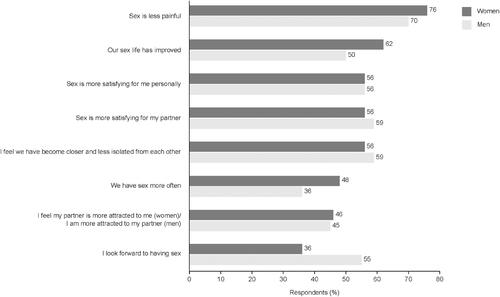

Treatment with vaginal estrogen had a positive effect on women’s relationships and intimacy, as reported by both women and men (). The top benefit was alleviation of women’s pain during sex (76% and 70% for women and men, respectively), followed by an improved sex life (62% and 50%). More than half of women and men felt closer to each other after the woman used vaginal hormones (56% and 59%).

Figure 2. Benefits on relationships and intimacy reported after use of vaginal hormone therapy by the woman.

Treatment with vaginal hormone therapy helped to restore women’s confidence and self-esteem. Among those who used vaginal estrogen therapy, 63% gained confidence in themselves as a sexual partner, 53% felt like more of a woman when thinking about their sex life and 52% felt sexually attractive again. Treatment helped women realize that vaginal discomfort is not irreversible and allowed them to rediscover a part of themselves that had seemed lost: 65% were happy that their body was working again, 57% felt rejuvenated after treatment and 41% felt they had regained their youth.

Discussion

The results of the CLOSER survey in Brazil show that, for many postmenopausal women, vaginal discomfort had a negative effect on sex and relationships and on their self-esteem. Nearly half of the women surveyed felt that not enough information is available about the symptoms and treatment of vaginal discomfort. The survey also revealed improvements for women and their partners after treatment with vaginal hormone therapy.

With its focus on intimate relationships, the CLOSER survey complements the results of the VIVA survey conducted in Brazil, which enrolled women who had ceased menstruating for ≥12 months [Citation9]. Responses in the two surveys were generally similar regarding symptoms of menopause and attitudes toward VA, but respondents in the VIVA survey (for which experience of vaginal discomfort was not an inclusion criterion) had lower knowledge of VA.

Most women (92%) were willing to talk to their HCP about vaginal discomfort. Despite this, 44% of women felt there is not enough information available about the symptoms and treatment of vaginal discomfort, and many women did not realize that VA is due to a loss of estrogen and can be treated using hormonal therapy. Based on their clinical experience, the Brazilian authors are under the impression that even among highly educated women there is a lack of knowledge about VA, and the subject may only arise when women consult them for genitourinary problems. HCPs (including doctors in general, and gynecologists in particular) are a key source of information. They should overcome any barriers in communication and proactively raise the issues of VA and the effectiveness of treatment during consultations with postmenopausal women [Citation1,Citation15,Citation16].

Men appeared to be less aware of the impact of vaginal discomfort on their sexual relationship than women (). This is in line with the Brazilian authors’ (L.M.P., M.C.O.W. and J.K. Jr) observations in clinical practice, and was also reported by respondents in other countries [Citation11–13]. On the other hand, when questioned about the avoidance of intimacy due to vaginal discomfort, the proportions of women (responding for themselves) and men (reporting their perceptions of their partners’ responses) were very similar (Supplementary Table 2). This result, and the high proportion of women (81%) who told their partner when they first experienced symptoms of vaginal discomfort, both suggest an openness in communication between couples in Brazil. Women’s and men’s perceptions of the benefits of vaginal hormone therapy were also very similar (). If closeness and openness of communication between couples could encourage a joint approach to seeking and using therapy, this would be advantageous.

There is a growing recognition of the importance of the perceptions and attitudes to menopause of women’s male partners. A recent survey of 450 men in the USA, in a stable relationship with a woman aged 45‒64 years who had experienced at least one menopausal symptom, showed that men were aware of their partners’ symptoms and the impact on their relationship, but that almost half were unaware that treatments were available [Citation17]. The authors suggest that educational resources for men could benefit both partners in coping with the menopause. Furthermore, it has been suggested that clinicians should approach the midlife changes in both women and men’s sexual health as a couple’s issue for patients who are in stable relationships – a concept termed ‘couplepause’ [Citation18]. This approach includes consideration of men’s midlife changes, but the key point in connection to our study is that a couple-oriented approach can help both members of the couple to improve sexual satisfaction and intimacy.

In our survey, VA had a negative impact on women’s self-esteem and confidence as a woman and a sexual partner. These effects on women’s emotions, and the deterioration of their physical relationship with their partner, should not be underestimated. They could contribute to couples growing apart from each other – a consequence that could potentially be avoided by using effective therapy.

In regard to therapy for VA, 47% of women had used vaginal (local) hormone therapy. The use of low-dose vaginal hormone (estrogen) therapy is in line with recommendations by the Brazilian Climacteric Association [Citation19] and several other societies, such as the International Menopause Society, the North American Menopause Society (NAMS), the European Menopause and Andropause Society (EMAS) and the British Menopause Society [Citation1,Citation2,Citation15,Citation20]. The consensus among these recommendations is that low-dose vaginal estrogen is effective for treating VA, with a good safety profile and minimal systemic absorption, and is preferred over systemic therapies when only genitourinary symptoms need to be treated. Results from the current study suggest that the benefits of treatment with vaginal estrogen therapy included a positive effect on sexual relationships (), with women’s confidence and self-esteem also reported to have been improved.

Estrogen can be administered locally via creams, tablets/suppositories or vaginal rings, all of which are effective. Patient preference should guide the choice, as this will aid adherence. Treatment should be continued in order to maintain benefits, as atrophic symptoms may recur when treatment is stopped [Citation1,Citation15,Citation21]. Clinical trial data and observational studies have not identified any increased risk of endometrial cancer or venous thromboembolism with low-dose local estrogen therapy; however, no trials have lasted for longer than 52 weeks, and unexpected postmenopausal bleeding should always be investigated [Citation1]. For women with breast cancer, low-dose vaginal estrogen could be considered in consultation with their oncologists [Citation1].

The CLOSER survey results for Brazil were broadly similar to those reported for Europe and the USA [Citation12–14]. There appeared to be some differences, based on the ranges of values from the different countries (Supplementary Table 4). For example, 48% of the female respondents in Brazil reported that vaginal discomfort put them off having sex, versus 28–35% in Europe. More Brazilian women and men reported several ways in which their sex lives had improved after treatment with vaginal hormones compared with respondents in other countries. For Brazil, Europe and the USA, respectively, the proportions of women finding sex less painful after the use of vaginal hormone therapy were 76%, 64% and 58%; for men the proportions were 70%, 57‒68% and 61%. Proportions of women finding sex more satisfying for themselves personally were 56%, 49‒50% and 40%, and for men were 56%, 41% and 32%, for Brazil, Europe and the USA, respectively. In Brazil, 62% of women reported that their sex lives had improved, versus 28% in the USA; the proportions for men were 50% and 35%, respectively [Citation13,Citation14].

The reasons for these differences are unknown. It has been noted that in Latin America, menopause is associated with aging and loss of femininity, resulting in a negative cultural attitude toward it, and that women express concern about its impact on their sex life [Citation22,Citation23]. The CLOSER survey results are in line with this. Palacios et al. reported that women in Latin America experience a relatively early onset of menopause (median age 48.6 years), based on a survey conducted in 15 countries [Citation22]. However, other studies suggest that this may not apply to Brazil: for example, a study of women living in São Paulo reported a mean age at menopause of 50 years [Citation24]. Furthermore, unequal access to health care may affect reported rates of vaginal discomfort, as public health care is characterized by constrained resources, and private health care is better resourced [Citation8]. Both types of health care are available in Brazil, but the survey did not record which type women received. These factors may have impacted the reporting rates in Brazil.

The CLOSER survey, to our knowledge, is the first to examine the effects of VA on women and their male partners. The results therefore extend the information available from surveys that collected data only from postmenopausal women. Other strengths include the large sample size and the fact that the same questions were asked in different countries, facilitating comparisons across different cultures. Limitations include the fact that the survey was restricted to participants who had volunteered to participate in research and who had Internet access. This is reflected in the high proportions of respondents with a tertiary educational level (women 76%, men 86%), which is not typical for Brazil. Those with tertiary education are likely to be among the wealthier proportion of the population. Furthermore, the CLOSER survey was designed some years before the ‘couplepause’ concept was published [Citation18], and therefore a shortcoming is that the male respondents were not necessarily the partners of the female respondents, although they were in a relationship with postmenopausal women of the same age. Women had to satisfy clearly defined inclusion criteria, but no adjustments were made for variables possibly relevant to vaginal discomfort [Citation25]. We also cannot rule out the possibility that the participants’ responses regarding their relationships and self-esteem may have been influenced by the other features of menopause and not solely by VA. However, the survey questions used the term ‘vaginal discomfort’ in order to focus respondents’ minds on this specific symptom. Many other interesting questions could have been explored, such as the effect on outcomes of the concomitant use of lubricants in women who did not have a favorable response to topical estrogens alone. However, due to the CLOSER survey’s specific objective of assessing the impact of VA on relationships between women and their male partners, and the need to keep the questionnaire to a manageable length to ensure response completion, such questions were not explored. Finally, the survey was limited to heterosexual women.

Despite these limitations, the CLOSER survey provides an insight into the impact of vaginal discomfort for sexually active postmenopausal women in Brazil. Women educated to a lower level than those who completed the current survey may be expected to have less knowledge of postmenopausal symptoms [Citation9] and may be less confident in communicating with their partners and/or HCPs, but will likely also suffer a negative impact of VA on their sexual relationships and self-esteem.

Conclusions

The CLOSER Brazil survey confirmed that VA had a negative impact on sexual relationships for both women and men, and reduced women’s confidence and self-esteem. Treatment with vaginal hormone therapy improved couple’s sexual relationships. Despite reporting a willingness to discuss VA with HCPs, many women in Brazil felt that not enough information on VA was available. Doctors can play a key role in advising women that VA can be effectively treated.

Potential conflict of interest

L.M.P. has a financial relationship (lecturer or member of advisory boards) with Abbott, Aché, Amgen, Bayer, Besins, FQM, Grunenthal, Hypera, Libbs, MSD, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, Sanofi and Zodiac. M.C.O.W. has a financial relationship (lecturer or member of advisory boards) with Novo Nordisk, Libbs and Grunenthal. J.K. Jr has no conflicts to disclose. I.P. is an employee of Besins Healthcare, São Paulo, Brazil. Y.S. is an employee of Novo Nordisk Global Business Services (GBS), Bangalore, India. R.E.N. has a financial relationship (lecturer, member of advisory boards and/or consultant) with Astellas, Bayer HealthCare, Endoceutics, Fidia, Gedeon Richter, MSD, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, Shionogi and Theramex.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (59.5 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors thank all respondents to the survey. Medical writing support for this manuscript was provided by Grace Townshend of Bioscript Medical, UK and funded by Novo Nordisk Health Care AG, Switzerland.

Additional information

Funding

References

- North American Menopause Society (NAMS). The 2020 genitourinary syndrome of menopause position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2020;27(9):976–992.

- Pitkin J. BMS – consensus statement. Post Reprod Health. 2018;24(3):133–138.

- Nappi RE, Martini E, Cucinella L, et al. Addressing vulvovaginal atrophy (VVA)/genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM) for healthy aging in women. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne)). 2019;10:561.

- Nappi RE, Kokot-Kierepa M. Vaginal health: insights, views & attitudes (VIVA) – results from an international survey. Climacteric. 2012;15(1):36–44.

- Nappi RE, Palacios S, Particco M, et al. The REVIVE (REal Women's VIews of Treatment Options for Menopausal Vaginal ChangEs) survey in Europe: country-specific comparisons of postmenopausal women's perceptions, experiences and needs. Maturitas. 2016;91:81–90.

- Panay N, Palacios S, Bruyniks N, et al. Symptom severity and quality of life in the management of vulvovaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women. Maturitas. 2019;124:55–61.

- Nappi RE, Palacios S. Impact of vulvovaginal atrophy on sexual health and quality of life at postmenopause. Climacteric. 2014;17(1):3–9.

- Nappi RE, de Melo NR, Martino M, et al. Vaginal health: insights, views & attitudes (VIVA-LATAM): results from a survey in Latin America. Climacteric. 2018;21(4):397–403.

- Pompei LM, Wender MCO, de Melo NR, et al. Vaginal health: insights, views & attitudes survey in Latin America (VIVA-LATAM): focus on Brazil. Climacteric. 2021;24(2):157–163.

- Domoney C, Currie H, Panay N, et al. The CLOSER survey: impact of postmenopausal vaginal discomfort on women and male partners in the UK. Menopause Int. 2013;19(2):69–76.

- Guidozzi F, Thomas C, Smith T, et al. CLarifying vaginal atrophy's impact On SEx and Relationships (CLOSER) survey in South Africa. Climacteric. 2017;20(1):49–54.

- Nappi RE, Kingsberg S, Maamari R, et al. The CLOSER (CLarifying Vaginal Atrophy's Impact On SEx and Relationships) survey: implications of vaginal discomfort in postmenopausal women and in male partners. J Sex Med. 2013;10(9):2232–2241.

- Nappi RE, Mattsson L, Lachowsky M, et al. The CLOSER survey: impact of postmenopausal vaginal discomfort on relationships between women and their partners in Northern and Southern Europe. Maturitas. 2013;75(4):373–379.

- Simon JA, Kokot-Kierepa M, Goldstein J, et al. Vaginal health in the United States: results from the vaginal health: insights, views & attitudes survey. Menopause. 2013;20(10):1043–1048.

- Baber RJ, Panay N, Fenton A. 2016 IMS Recommendations on women's midlife health and menopause hormone therapy. Climacteric. 2016;19(2):109–150.

- Palacios S, Nappi RE, Shapiro M, et al. An individualized approach to the management of vaginal atrophy in Latin America. Menopause. 2019;26(8):919–928.

- Parish SJ, Faubion SS, Weinberg M, et al. The MATE survey: men's perceptions and attitudes towards menopause and their role in partners' menopausal transition. Menopause. 2019;26(10):1110–1116.

- Jannini EA, Nappi RE. Couplepause: a new paradigm in treating sexual dysfunction during menopause and andropause. Sex Med Rev. 2018;6(3):384–395.

- Pompei LM, Machado RB, Wender MCO, et al. Consenso Brasileiro de Terapêutica Hormonal da Menopausa [Portuguese] (Brazilian Consensus on Hormonal Therapies of the Menopause); 2018 [2020 Sep]. Available from: http://sobrac.org.br/consenso_brasileiro_de_th_da_menopausa_2018.html.

- Rees M, Pérez-López FR, Ceasu I, EMAS, et al. EMAS clinical guide: low-dose vaginal estrogens for postmenopausal vaginal atrophy. Maturitas. 2012;73(2):171–174.

- Derzko CM, Röhrich S, Panay N. Does age at the start of treatment for vaginal atrophy predict response to vaginal estrogen therapy? Post hoc analysis of data from a randomized clinical trial involving 205 women treated with 10 μg estradiol vaginal tablets. Menopause. 2020;28(2):113–118.

- Palacios S, Henderson VW, Siseles N, et al. Age of menopause and impact of climacteric symptoms by geographical region. Climacteric. 2010;13(5):419–428.

- Sturdee DW, Panay N. Recommendations for the management of postmenopausal vaginal atrophy. Climacteric. 2010;13(6):509–522.

- Roman Lay AA, do Nascimento CF, de Oliveira Duarte YA, et al. Age at natural menopause and mortality: a survival analysis of elderly residents of São Paulo. Brazil. Maturitas. 2018;117:29–33.

- Castelo-Branco C, Cancelo MJ, Villero J, et al. Management of post-menopausal vaginal atrophy and atrophic vaginitis. Maturitas. 2005;52(Suppl 1):S46–S52.