Abstract

Objective

To provide a conceptual overview of how medical doctors and nurses experience patient suicide.

Method

A systematic search identified ten qualitative papers for this interpretive meta-synthesis. Constructs were elicited and synthesized via reciprocal translational analysis.

Results

Findings comprised four inter-related themes: (1) Intrinsic but taboo: patient suicide perceived as inevitable yet difficult to discuss. (2) Significant emotional impact: clinicians deeply affected, with resilience important for mitigating impact. (3) Failure and accountability: intense self-scrutiny, guilt and shame, with blame attributed differently across professions. (4) Legacy of patient suicide: opportunities for growth but lack of postvention guidance.

Conclusions

Patient suicide affects clinicians profoundly. Further research should evaluate postvention procedures to inform effective guidance and support, acknowledging professional differences.

Patient suicide profoundly affects doctors and nurses as “suicide survivors.”

Despite common themes, professions differed in blame attributions.

Organizations must develop postvention responses to meet clinicians’ pastoral needs.

Highlights

Approximately 800,000 people die by suicide worldwide annually and many more attempt to take their own lives (World Health Organization, Citation2020). Mental ill-health is a risk factor (Hawton, Houston, Haw, Townsend, & Harriss, Citation2003) and suicide is increasingly regarded as a healthcare issue, with considerable research aimed at identifying and evaluating strategies for clinical intervention (Mann et al., Citation2005; Zalsman et al., Citation2016). Healthcare professionals are consistently identified as key to reducing incidence (NCISH, Citation2014; Stanistreet, Gabbay, Jeffrey, & Taylor, Citation2004), despite clear difficulties in predicting suicide (Leavey et al., Citation2017). However, the effects of this burden on clinicians are little-investigated.

Losing a patient to suicide is often considered an occupational hazard (Chemtob, Bauer, Hamada, Pelowski, & Muraoka, Citation1989; Ruskin, Sakinofsky, Bagby, Dickens, & Sousa, Citation2004), but clinician reactions to patient suicide are poorly-understood and it is essential to improve this understanding urgently. Patient suicide can significantly affect healthcare professionals, with clinicians themselves considered as potential “second victims” following such adverse patient events (Kable & Spigelman, Citation2018; Scott et al., Citation2009; Wu, Citation2000). Common reactive emotions include shock, disbelief and grief (Hendin, Haas, Maltsberger, Szanto, & Rabinowicz, Citation2004; Ng et al., Citation2019) with some also experiencing posttraumatic stress disorder (McAdams & Foster, Citation2000). Clinicians can experience significant consequences harmful to themselves and healthcare organizations, including career change, clinician suicide (Gibbons et al., Citation2019; Kable & Spigelman, Citation2018), and feelings of failure, guilt, shame and fear of litigation (Gaffney et al., Citation2009; Kendall & Wiles, Citation2010; Valente & Saunders, Citation2009). This seems particularly amplified when clinicians have not anticipated their responses and subsequent actions required in the aftermath of patient suicide (Grad & Michel, Citation2005), often termed “postvention” (Schneidman, Citation1971). Professional training does not necessarily confer adequate resilience (Midence, Gregory, & Stanley, Citation1996), and organizational responses typically focus on lessons learned and future prevention, rather than clinician support (Anderson, Byng, & Bywaters, Citation2006; Department of Health, Citation2012; Public Health England, Citation2016). From the clinician-focused and organizational perspectives, it is crucial to understand the processes underlying responses to suicide among healthcare professionals, as there appear to be substantial needs which currently go unmet.

Early autobiographical essays and case reports demonstrated the impact of patient suicide on clinicians (Carter, Citation1971; Fox & Cooper, Citation1998; Kolodny, Citation1979). These were further illustrated by validated scales reporting effects over time including reactive changes that clinicians made to their practice (Chemtob, Hamada, Bauer, Torigoe, & Kinney, Citation1988; Hendin, Lipschitz, Maltsberger, Haas, & Wynecoop, Citation2000; Spencer, Citation2007). The findings have been summarized in narrative (Ellis & Patel, Citation2012) and systematic reviews (Séguin, Bordeleau, Drouin, Castelli-Dransart, & Giasson, Citation2014; Talseth & Gilje, Citation2011). All note diverse clinician attitudes toward the level and type of support required afterwards, encouraging further research to underpin training and postvention guidance. However, the utility of these reviews is constrained by the quantitative methodologies of included studies, which precludes detailed phenomenological explanations of variation and limits our understanding of how differences between clinicians should be considered.

The shift toward rigorous qualitative studies (e.g., Darden & Rutter, Citation2011; Kouriatis & Brown, Citation2014; Sanders, Jacobson, & Ting, Citation2005) allows investigation and contextualization of phenomenological complexity (Clarke & Jack, Citation1998). Such studies support further meaningful exploration of how clinicians experience patient suicide, enabling the development of more nuanced strategies for postvention and clinician self-care (Norcross, Citation2000). Accordingly, there is a need to systematically review the emerging body of qualitative literature in this field.

To date, qualitative studies either aggregate findings from multidisciplinary teams or explore experiences within discrete professions, predominantly doctors or nurses, with one exception; Causer, Muse, Smith, and Bradley (Citation2019) evaluated experiences of suicide across a range of disciplines including school-based counselors, social care, psychologists and nurses. However, their search terms were relatively limited, potentially masking crucial differences in experience between professions (Zimmer, Citation2006).

Accordingly, this review addresses the need for qualitative, discipline-specific meta-synthesis of professionals’ reactions to patient suicide. Our search was limited to studies of medical and nursing professionals only. Our rationale for this sample selection was twofold: (1) they are the dominant healthcare professionals by number and hold responsibility for the majority of clinical contacts; and (2) whilst their professional cultures differ (Hall, Citation2005) they share a history of collaborating to manage risk in medical settings using similar diagnostic models (Johnstone & Dallos, Citation2013; Mackay, Citation1993). The availability of multiple papers for both professions also enabled meaningful cross-study interpretations and comparisons (Paterson, Thorne, Canam, & Jillings, Citation2001). This review therefore aimed to conduct an interpretive meta-synthesis of qualitative literature to provide a conceptual overview of how medical doctors and nurses experience patient suicide.

METHOD

Our method aligned with Noblit and Hare (Citation1988) seven phases of meta-ethnography, including: developing a research question and appropriate search strategy; using inclusion and exclusion criteria to identify relevant studies; appraising study quality; and extracting data for synthesis and re-interpretation via reciprocal translational analysis, where common themes are iteratively translated into one another (Bridges et al., Citation2013; Britten et al., Citation2002; Harrison et al., Citation2014).

Context is fundamental to qualitative research, as it allows methodologically-sound interpretations of differing experiences, but it can be overlooked when aggregating findings. This was addressed by systematically integrating findings, utilizing the same hermeneutic principles that apply to individual studies to honor phenomenological experiences across papers (Noblit & Hare, Citation1988; Zimmer, Citation2006).

Search Strategy

CHIP (Context, How, Issue, Populations) was used to formulate the research question and search strategy (Shaw, Citation2011). Search terms were refined using the library of Medical Subject Headings (MeSH). Three searches were composed based on key words and subject headings linked by the Boolean operator “OR”: describing patient suicide, profession (i.e., medical/nursing), and qualitative research. These searches were then combined using “AND.” No date restrictions were applied. The final search strategy () was developed with support from a librarian subject specialist to optimize study identification across AMED, CINAHL, Medline, PsycINFO, Scopus, and Web of Science. Searches were conducted in February 2020. Finally, reference lists from key studies were manually searched for additional papers. During the peer-review process, one reviewer recommended that we additionally search PubMed and Google Scholar for completeness. These searches were carried out and identified 20 additional papers of interest, of which none met the inclusion criteria.

TABLE 1. Search terms utilized for systematic literature review.

Eligibility Criteria

Peer-reviewed English-language qualitative studies reporting the experiential impact of patient suicide on doctors and nurses were included. Studies were excluded if they focused solely on: patient, family or caregiver experiences; risk assessment, management, prevention or intervention; physician-assisted suicide or euthanasia; or staff experiences of or attitudes toward attempted suicide. Furthermore, studies of participants who were not medical doctors or nurses were excluded, as were papers reported only quantitative findings. Editorials and reviews were excluded since they offered no new data.

Identification of Papers

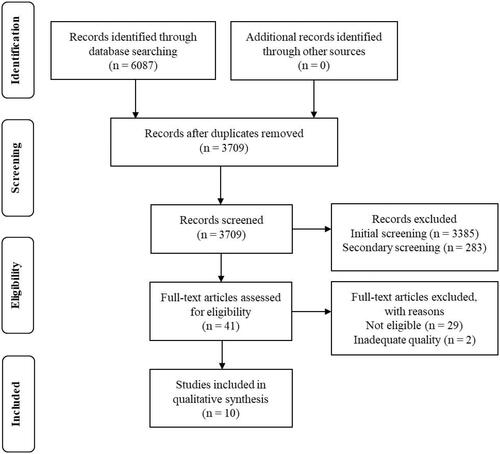

The initial database search identified 3709 unique studies once duplicates were removed. Two reviewers screened titles and abstracts for whether the study focused on exploring clinicians’ experiences of patient suicide, which excluded 3668 studies. Full text was obtained for 41 papers which appeared to meet the inclusion criteria. Further study excluded a further 29 studies, leaving 12 papers requiring quality assessment. Two were subsequently excluded based on low study quality (see below), leaving ten studies for review (). No additional studies were manually identified from key papers. Of the ten selected papers, four comprised studies of general practitioners, two of psychiatrists, and four of nurses (one of these focusing specifically on mental health nurses). For the purposes of this review, these groups will jointly be referred to as “clinicians” except where disambiguated by group for specific discussion.

Quality Review

The three authors independently appraised the 12 papers using a formal appraisal checklist to assess methodological clarity, data collection, analysis, and reporting (CASP, Citation2013). Devising a rating system enabled efficient comparison of studies, where a score of one or zero points was assigned to the answers “yes” or “no,” respectively. A total score of ten points indicated a rigorous study. While ratings were initially only intended to inform weightings for the meta-synthesis, two studies scored three points, indicating severely-flawed methodological and reporting quality. One failed to support interpretations and conclusions with evidence from the data itself (Kahne, Citation1968); the other privileged a quantitative approach to analysis (reporting percentages) and implied that not all participants were qualified clinicians (Midence et al., Citation1996). These were therefore excluded to maintain meta-ethnographic fidelity. The ten retained studies scored between seven and ten points, with particular strengths in robust, reflexive and transparent analysis (see for study profiles).

TABLE 2. Study profiles for the ten papers included in the meta-synthesis.

Interpretive Meta-Synthesis

In the interpretive paradigm, individuals’ narratives are regarded as interpretations based on meanings they assign to their experiences (Noblit & Hare, Citation1988). These primary data are identified as “first-order constructs” (Britten et al., Citation2002; Zimmer, Citation2006). Researchers then make interpretations from the primary data based on their own experiences and epistemological positions (“second-order constructs”). When multiple studies are drawn together in a meta-synthesis, new insights are developed through interpretations of interpretations. These are “third-order constructs,” which carry their own contextual complexity.

In practice, distinguishing between first- and second-order constructs may be difficult as it is often unclear whether researchers’ commentaries describe participant narratives, or interpretations made through their own experiences and methodological standpoints (Atkins et al., Citation2008). To systematize analysis of concepts emergent from each paper and maintain our focus on recurring themes, this review therefore followed the approach recommended by Atkins et al. (Citation2008); all data extracted from the original papers were considered first-order constructs, including participant quotations and authors’ comments from study authors. Original wording was preserved for all content to promote fidelity of meanings and concepts, and to assure the integrity of the methodology (Britten et al., Citation2002). Second-order constructs were developed iteratively with additional interpretations and ideas from the ten papers refined through a process of continuous discussion. Additional interpretations emergent from the first-order constructs were reflected in themes of: perceived helplessness; difficulty talking about suicide; clinician shame following completed suicide; differences in accountability across professional cultures; and the importance of resilience and postvention guidance for personal and professional growth. For illustrative purposes, presents first- and second-order constructs interpreted from one study.

TABLE 3. Example of first- and second-order constructs from a selected paper.

The emergent accounts from the primary studies appeared largely consistent with similar themes arising across papers. It was therefore possible to reliably translate accounts into one another through the development of contextually congruent third-order constructs across studies that maintained phenomenological complexity (Paterson et al., Citation2001; Zimmer, Citation2006). The conceptual themes were initially grouped to develop a coherent line of argument (Britten et al., Citation2002), and interpretations were further refined to ensure they emerged from the original data and captured findings relevant to the review aims (Noblit & Hare, Citation1988). These third-order constructs comprised four inter-related conceptual themes: “Intrinsic but taboo”; “Significant emotional impact”; “Failure and accountability”; and “Legacy of patient suicide” (). The themes are discussed under these headings.

TABLE 4. Third-order constructs—taxonomy of findings.

FINDINGS

All quotations comprise original author commentaries and clinician quotes from the ten included studies.

Intrinsic but Taboo

Although infrequent, clinicians described patient suicide as “part and parcel” (Saini, Chantler, While, & Kapur, Citation2016, p. 417) of healthcare. Most talked about it being “inevitable in certain situations, no matter how hard we try” (Wang, Ding, Hu, Zhang, & Huang, Citation2016, p. 356) and feeling unable to prevent it: “if somebody really wants to, they will” (Foggin et al., Citation2016, p. 740).

Despite this, clinicians “differed in their propensity to explore suicide ideation” (Davidsen, Citation2011, p. 113). Some worried about increasing risk (Wang et al., Citation2016), and most conveyed the discussion as unmentionable, consistent with findings reporting stigma toward family members bereaved by suicide (Pitman, Stevenson, Osborn, & King, Citation2018). This sense of taboo persisted in the aftermath of suicide, evidenced by clinicians expressing discomfort (Robertson, Paterson, Lauder, Fenton, & Gavin, Citation2010) and using euphemisms such as “topped himself [and] this sort of incident” (Foggin et al., Citation2016, p. 740). In some cases where patients had not exhibited apparent risk of suicide, incidents could even be attributed to accident, avoiding acceptance of a deliberate act (Hultsjö et al., Citation2019).

Significant Emotional Impact

Intense emotions including shock, sadness, grief and anger were reported: “I felt like there was a stone on my chest” (Wang et al., Citation2016, p. 358); “it’s something I’ll have to carry forever” (Gibbons et al., Citation2019, p. 237). Greater “proximity to the event” (Joyce & Wallbridge, Citation2003, p. 21) and a high professional attachment (Saini et al., Citation2016) appeared most intensely distressing: “It certainly did affect me because I felt I put myself out…I wanted to help” (Saini et al., Citation2016, p. 418). Patients were commonly characterized as having suffered deeply, which affected clinicians profoundly in turn. Hultsjö et al. (Citation2019) report multiple such expressions: “I had horrible feelings and didn’t know how to handle them…I felt so bad”; and “you could never really reach him, it was like…you became very empty” (p. 1627).

Personal experiences of suicide “could sometimes make it extremely difficult” (Foggin et al., Citation2016, p. 742) and accounts suggested individual variation in recovery time and process. The emotional impact of patient suicide appeared mitigated by “spiritual beliefs” (Joyce & Wallbridge, Citation2003, p. 21), and sharing distress with family and friends: “I was badly hurt and cried to my husband” (Wang et al., Citation2016, p. 358). Positive, reflective reframing of experiences to address negative emotions also seemed helpful, while hostile or persecutory reactions from the clinicians’ employer exacerbated distress (Gibbons et al., Citation2019).

Failure and Accountability

Clinicians emphasized “the sense of failure [as]… the biggest thing” (Joyce & Wallbridge, Citation2003, p. 19), grounded in a sense of ineffectively managing risk. They expected themselves “to have prevented the suicide” (Talseth & Gilje, Citation2007, p. 631), and yet expressed lack of ability to live up to this: “I am not omnipotent” (Pavlič, Treven, Maksuti, Švab, & Grad, Citation2018, p. 179). This evoked a sense of failure to protect vulnerable individuals, one participant describing a case where a patient “was so institutionalized… It is a failure. We know that before they have left the hospital” (Hultsjö et al., Citation2019, p. 1628). These descriptions appear imbued with helplessness and dread.

Patient suicide often prompted “great self-scrutiny” (Saini et al., Citation2016, p. 418), which took “a great deal of mental energy” (Davidsen, Citation2011, p. 115). Self-blame and speculation was prominent: “how could I be so naïve” (Talseth & Gilje, Citation2007, p. 626), along with rumination about what they may have missed, generating fear about “perceived judgment and blame” (Wang et al., Citation2016, p. 354). Some respondents sought to create distance between themselves and the suicide “to show they did their job well and that they are ‘good’ [clinicians]” (Robertson et al., Citation2010, p. 3), seemingly aiming to reducing potential legal accountability. Gibbons et al. (Citation2019) quoted a psychiatrist: “It is a very frightening world where one professional group is given an impossible task and then censured by society (and themselves) for failing to achieve it” (p. 239).

Whilst both doctors and nurses expressed guilt, self-scrutiny, and fear of accountability, attributions of blame differed. Nurses tended to attribute patient suicide externally, reflected in accounts discussing adherence to protocol and doing things “by the book” (Joyce & Wallbridge, Citation2003, p. 19). Some emphasized they had thoroughly assessed risk pre-suicide to rebuff any unspoken judgment of culpability: “there had been nothing untoward indicating…any intention of suicide…she was bright…attended to her hygiene…had her breakfast” (Robertson et al., Citation2010, p. 4). Alternatively, blame was attributed to institutional failure to impart risk-management skills: “I don’t know how to ask… how to comfort” (Wang et al., Citation2016, p. 354).

Medical doctors tended to internalize blame, reporting “shame and responsibility that seems to be accepted in the whole psychiatric community about suicide” (Gibbons et al., Citation2019, p. 238). Patient suicide was attributed to failure to emotionally connect with patients, with particular self-criticism where they had felt unable to facilitate disclosure of suicidal ideation: “they had actually come to talk about this… but they never came out with it… there we have actually failed” (Davidsen, Citation2011, p. 115). Feelings of guilt and self-blame were amplified if doctors felt they had developed meaningful relationships with patients “who they felt [were] on the ‘road to recovery’” (Saini et al., Citation2016, p. 418).

Legacy of Patient Suicide

Clinician reflections on how to change their approach post-suicide were common (Talseth & Gilje, Citation2007). Profound and lasting self-doubt dominated accounts: “I doubt whether I could do this job anymore” (Wang et al., Citation2016, p. 358). Multiple individuals reported seeking to retire or change career after experiencing patient suicide; one clinician reported feeling “ineffectual in changing systems that I recognize as being ineffective and fragmented” (Gibbons et al., Citation2019, p. 237). However, intense self-scrutiny sometimes motivated improvements: “I have got better at asking if they think of suicide” (Davidsen, Citation2011, p. 115). Clinicians often became more cautious reporting “ongoing thoughtfulness about patient contact—made me more vigilant and risk conscious” (Gibbons et al., Citation2019, p. 237). Using experiences to improve future care by “teaching students and colleagues” (Talseth & Gilje, Citation2007, p. 632) also facilitated growth.

Clinicians reported feeling responsible for supporting distressed families post-suicide, yet felt underprepared with insufficient time to do so. Onward referrals for counseling or support were hindered by a lack of “third-sector organisations that specifically supported those bereaved by suicide” (Foggin et al., Citation2016, p. 742). This resulted in avoidance of families by some clinicians, particularly those “afraid of medical disputes” (Wang et al., Citation2016, p. 358).

All studies emphasized a need for organizational support to manage emotional impact and “professional accountability” (Robertson et al., Citation2010, p. 5). The level and type of support required varied “between staff who needed to talk about it right away and staff who didn’t want to discuss it at all” (Joyce & Wallbridge, Citation2003, p. 19). One GP referenced a need for “solace, understanding [and] compassion” (Pavlič et al., Citation2018, p. 179), and a supportive, non-judgmental stance from managers as well as the overall organization was considered helpful (Gibbons et al., Citation2019). Reassurance from colleagues seemed crucial for moving forward: “I talked…with my chief…he clearly said I could not have done anything else…I was relieved” (Talseth & Gilje, Citation2007, p. 627). Where this was unavailable, clinicians “hesitate[d] to share their feelings” (Wang et al., Citation2016, p. 359), and expressed concern at having to manage “the emotional impact of the suicide by themselves” (Davidsen, Citation2011, p. 115). Author commentaries suggested this may reflect insufficient “space to deal with their own grief” (Foggin et al., Citation2016, p. 744) due to the pressures of ongoing patient interactions in the immediate aftermath.

Pervasive across papers was the sense that organizations offered insufficient guidance to effectively manage responses to patient suicide. There was a notable absence of formal postvention arrangements within the narratives, both for working with bereaved families and managing personal impact: “we’re very good at supporting each other…but we don’t have any formal back up” (Saini et al., Citation2016, p. 418). Additionally, barriers to utilizing support were described including “pride…as well as the residual stigma of mental health in health professionals” (Foggin et al., Citation2016, p. 742), particularly among medical professionals (Pavlič et al., Citation2018). Consequently, introducing postvention guidance comprising personal support and professional procedures was highlighted as a necessary outcome “to help [clinicians] better cope with negative consequences of [patient] suicide” (Wang et al., Citation2016, p. 359).

DISCUSSION

Whilst the term “suicide survivor” has traditionally been limited to family and friends bereaved by suicide, clinicians are increasingly recognized as legitimate survivors (Grad & Michel, Citation2005). The current review demonstrates that healthcare professionals share the shame and self-blame seen in families post-suicide, illustrating “second victimhood,” where clinicians become traumatized by adverse patient events (Kable & Spigelman, Citation2018; Scott et al., Citation2009; Wu, Citation2000). Our findings are broadly comparable with Causer et al. (Citation2019), who reviewed studies of professionals from social care, education, psychology and nursing. They found themes of traumatic response to suicide (paralleling our “significant emotional impact), feeling scrutinized and blamed (our “failure and accountability”) and support and learning (our “legacy of patient suicide”). Our additional finding of differences between doctors and nurses in responses to suicide emphasizes the importance of fine-grained exploration of reactions, and the need for profession-specific support.

Cognitive-Emotional Dissonance and Support

Despite the perceived inevitability of patient suicide, this review demonstrates that such incidents deeply affect doctors and nurses. Clinicians experience dissonance between their reported cognitions (suicide is inevitable, even desired by [some] patients, hence untreatable) and the guilt and shame experienced in the aftermath, along with fear of being held responsible for a patient’s death (Chemtob et al., Citation1988; Hultsjö et al., Citation2019; Talseth & Gilje, Citation2007). For some, the fear of blame was linked to litigation (Foggin et al., Citation2016); for others, it was colleagues’ perceptions of their competence (Joyce & Wallbridge, Citation2003). This supports existing consensus that losing a patient to suicide is an intensely challenging experience and may explain high reported levels of post-incident self-scrutiny, as well as the sense of being unworthy or undeserving of formal support (Chemtob et al., Citation1988; Ellis & Patel, Citation2012; McAdams & Foster, Citation2000; Midence et al., Citation1996; Séguin et al., Citation2014; Spiegelman & Werth, Citation2005).

The distress generated by this cognitive-emotional dissonance may contribute to some clinicians attempting to cope alone or through family and friends, with some wary of voicing distress to colleagues in case it reinforces impressions of their perceived guilt (Robertson et al., Citation2010). However, our review demonstrated that when clinicians felt supported by colleagues and discussed concerns with them, it was beneficial (Saini et al., Citation2016), aligning with findings that support-seeking following adverse patient events is invaluable for clinicians’ growth (Scott et al., Citation2009). This was further supported by Gibbons et al. (Citation2019) report that a critical employer response increased distress, while compassionate organizational responses lessened it.

Given the significant emotional impact of patient suicide identified here and in prior work, it seems vital to normalize such reactions among clinicians, which may in turn encourage formal support-seeking (Andriessen & Krysinska, Citation2012). This is of particular importance in light of our experience working with suicidal patients. Our experiences show that although distress may endure, acute suicidal crises are often short-lived and can be prevented through brief interventions and coping strategies, for example through collaborative safety planning (McCabe, Garside, Backhouse, & Xanthopoulou, Citation2018).

Differences Across Professional Cultures

The differences between medical and nursing cultures reported here seem to reflect the values and roles of both professions. Specifically, we found differences in attribution of blame following patient suicide. Nurses typically attributed the event to external factors, such as institutional failure to provide necessary training, and would point to having adhered to protocols as evidence of having done their jobs well. Conversely, doctors were more likely to attribute blame internally, to a failure in building relationships with individuals and facilitating disclosure of suicidal ideation. This important difference can potentially be related to discipline-specific factors. Nurses commonly value patient self-determination and traditionally train in teams to problem-solve collectively and perform effective handover of patient information (Hall, Citation2005). Whilst both doctors and nurses seemingly hesitated to discuss patient suicide with colleagues, nurses primarily feared criticism and being held responsible for failing the team (Joyce & Wallbridge, Citation2003). This may explain their external attributions of blame and tendency to enact rule-based denial, minimizing their own stake in the incident (Robertson et al., Citation2010) in favor of criticizing their training (Wang et al., Citation2016). This is supported by other work examining nurses’ interactions with individuals exhibiting suicidal behavior or making suicide attempts; again, nursing staff are reported as risk-averse and highly fearful of being assigned responsibility for their perceived failure (Morrissey & Higgins, Citation2019; Türkleş, Yılmaz, & Soylu, Citation2018).

Conversely, medical doctors train as independent clinicians in highly-competitive environments (Hall, Citation2005). This was described as doctors having “pride [in their abilities] or…personality traits of high achieving…workers” (Foggin et al., Citation2016, p. 742). This may contribute to many internalizing blame and feeling they ought to manage the impact of patient suicide alone (Davidsen, Citation2011). Hall further suggests that doctors tend to uphold an authoritarian physician-patient relationship, and consequently attribute patient suicide to a personal failure to diagnose and identify risk (Saini et al., Citation2016). Subtle differences also emerged between medical specialisms, with psychiatrists tending toward a more reflective stance than GPs, in one study describing themselves as therapists (Talseth, Jacobsson, & Norberg, Citation2000). Since psychotherapeutic models value analysis of clinicians’ personal reactions to their patients (i.e., countertransference; Tillman, Citation2006), this may explain the greater reflexivity (tendency to self-examination and consideration of one’s values as a healthcare practitioner) observed in this professional culture.

Importance of Organizational Responses and Implications for Practice

Individual clinicians utilized various strategies to cope with patient suicide (e.g., talking to others, positive reframing and spiritual practices). However, strategies typically did not include organizational support and this was felt to be lacking, with current policy focused on protocol-driven suicide prevention strategies and critical incident reviews after adverse patient events (Anderson et al., Citation2006; Department of Health, Citation2012; Public Health England, Citation2016). Although these may help improve future patient care, they fail to address clinicians’ experience of patient suicide (Cutcliffe & Stevenson, Citation2008; Kendall & Wiles, Citation2010) and can feel punitive. Consequently, they may exacerbate feelings of guilt and self-blame and detract from clinicians’ self-care (Norcross, Citation2000; Strobl et al., Citation2014). This is broadly consistent with previous research across various healthcare professions, which generally finds organizational support wanting and calls for improvements to better prepare clinicians and facilitate recovery following patient suicide (Ellis & Patel, Citation2012; Grad & Michel, Citation2005; Leaune et al., Citation2019; Sanders et al., Citation2005; Schneidman, Citation1971; Sherba, Linley, Coxe, & Gersper, Citation2019).

Coordinated organizational responses privileging safety and compassion therefore seem vital in addressing the taboo of suicide and offering formal post-suicide interventions. One suggested route is offering supervision for affected clinicians to share concerns and be reassured by supervisors (Fairman, Montross-Thomas, Whitmore, Meier, & Irwin, Citation2014; Grad et al., Citation1997; Henry & Greenfield, Citation2009; Knox, Burkard, Jackson, Schaack, & Hess, Citation2006). For meaningful discussions that account for potential shame and stigma, developing psychological safety in teams feels important, where clinicians are routinely met with compassion and do not feel exposed to threats in their relationships with colleagues. Gibbons et al. (Citation2019) further identified commonly-described wishes for a “suicide lead” to provide confidential advice and support, and a confidential reflective space specifically for processing the effects of patient suicide, also recommended by Taylor et al. (Citation2007). In practice, this could be achieved by embedding staff psychological wellbeing provision into teams or organizations.

A further suggestion has been provision of guidance for working with grieving families (Foggin et al., Citation2016). Finally, early preparation for those going into healthcare professions is advisable, including education around suicide prevention through safety planning and implementation of protocols to provide support and reduce social isolation (Ruskin et al., Citation2004). In line with our findings, guidance should be co-produced with clinicians to accommodate individual preferences and variations across professional cultures.

Strengths and Limitations

Past reviews regarding the impact of patient suicide on healthcare professionals have not been systematic (Ellis & Patel, Citation2012), have aggregated cross-methodological findings without contextual regard (Séguin et al., Citation2014; Valente & Saunders, Citation2009), have not separated the impact of patient suicide from caring for suicidal patients (Talseth & Gilje, Citation2011) or have amalgamated diverse professional groups (Causer et al., Citation2019). These past reviews therefore present a limited analysis, with low generalizability. Whilst some argue this challenge is mirrored in reviewing qualitative literature with differing epistemological and methodological assumptions (Barbour, Citation2001), this systematic review utilized rigorous, theory-driven techniques to apply an interpretive synthesis, which can improve generalizability of findings (Noblit & Hare, Citation1988).

Although this meta-synthesis may be limited by publication biases and the exclusion of gray literature, the search strategy itself was wide-ranging and covered multiple reputable databases. There was a reasonable quantity of qualitative studies of sound methodological and reporting quality when restricting to medical and nursing professionals, enabling discipline-specific analysis.

Re-interpretation of study findings was necessarily dependent upon the data reported, rather than considering primary data directly. Whilst grounded in transparent methodology, the derivation of second- and third-order constructs is shaped by author subjectivity; a replication might produce some variation in conclusions. One of the review authors has personal experience of suicide, which is likely to have affected interpretations. An iterative and reflective process of discussion when analyzing the data as well as verification of constructs by the two remaining authors therefore minimized subjective bias and enhanced methodological rigor.

Directions for Future Research

The limited amount of rigorous qualitative literature exploring impacts of patient suicide on clinicians reaffirms Hjelmeland and Knizek (Citation2010) call to increase qualitative studies in suicide research. They argue that qualitative methodologies enable exploration of psychological mechanisms, leading to interventions grounded in psychological theory which can then be tested quantitatively. In recognition of the inter-professional differences identified, it is vital that such research extends to healthcare professionals beyond doctors and nurses. Further, the cultural bias in the reported studies highlights a need for research in other cultural contexts, with only one study (Wang et al., Citation2016) conducted outside the West. Finally, little is known about effective organizational approaches to support clinicians following patient suicide (Ellis & Patel, Citation2012), so continued design and evaluation of postvention procedures is crucial to facilitate development of evidence-based guidance and protocols.

CONCLUSION

Patient suicide is considered an occupational hazard for healthcare professionals (Chemtob et al., Citation1989), and only recently have emerging qualitative studies acknowledged the complexity of clinician responses to patient suicide. This review aimed to provide a conceptual overview of qualitative research findings regarding the experiential impact of patient suicide on doctors and nurses. The findings demonstrate that patient suicide profoundly affects clinicians. Whilst there may be opportunities for growth, the lack of formal postvention guidance to support clinicians in managing the personal and professional repercussions of patient suicide may potentiate their distress. Given the high risk of patient suicide and its significant impact on clinicians, organizations must anticipate its occurrence and prepare to respond to clinicians’ needs, taking variations across professional cultures into account. Further research is required to support organizations in defining and developing such strategies for clinician self-care.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

This work was not supported by any funding agency, and no conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Sameen Malik

Sameen Malik, Sarah Gunn and Noelle Robertson, Department of Neuroscience, Psychology and Behaviour, University of Leicester, Leicester, England.

Sarah Gunn

Sameen Malik, Sarah Gunn and Noelle Robertson, Department of Neuroscience, Psychology and Behaviour, University of Leicester, Leicester, England.

Noelle Robertson

Sameen Malik, Sarah Gunn and Noelle Robertson, Department of Neuroscience, Psychology and Behaviour, University of Leicester, Leicester, England.

REFERENCES

- Anderson, M., Byng, R., & Bywaters, J. (2006). Suicide audit in primary care trust localities: A tool to support population based audit of suicides and open verdicts. Nottingham: National Institute for Mental Health in England.

- Andriessen, K., & Krysinska, K. (2012). Essential questions on suicide bereavement and postvention. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 9(1), 24–32. doi:10.3390/ijerph9010024

- Atkins, S., Lewin, S., Smith, H., Engel, M., Fretheim, A., & Volmink, J. (2008). Conducting a meta-ethnography of qualitative literature: Lessons learnt. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 8(1), 1–10. doi:10.1186/1471-2288-8-21

- Barbour, R. S. (2001). Checklists for improving rigour in qualitative research: A case of the tail wagging the dog? BMJ, 322(7294), 1115–1117. doi:10.1136/bmj.322.7294.1115

- Bridges, J., Nicholson, C., Maben, J., Pope, C., Flatley, M., Wilkinson, C., … Tziggili, M. (2013). Capacity for care: Meta-ethnography of acute care nurses’ experiences of the nurse-patient relationship. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 69(4), 760–772. doi:10.1111/jan.12050

- Britten, N., Campbell, R., Pope, C., Donovan, J., Morgan, M., & Pill, R. (2002). Using meta ethnography to synthesise qualitative research: A worked example. Journal of Health Services Research & Policy, 7(4), 209–215. doi:10.1258/135581902320432732

- Carter, R. E. (1971). Some effects of client suicide on the therapist. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 8(4), 287–289. doi:10.1037/h0086678

- Causer, H., Muse, K., Smith, J., & Bradley, E. (2019). What is the experience of practitioners in health, education or social care roles following a death by suicide? A qualitative research synthesis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(18), 3293. doi:10.3390/ijerph16183293

- Chemtob, C. M., Bauer, G. B., Hamada, R. S., Pelowski, S. R., & Muraoka, M. Y. (1989). Patient suicide: Occupational hazard for psychologists and psychiatrists. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 20(5), 294–300. doi:10.1037/0735-7028.20.5.294

- Chemtob, C. M., Hamada, R. S., Bauer, G., Torigoe, R. Y., & Kinney, B. (1988). Patient suicide: Frequency and impact on psychologists. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 19(4), 416–420. doi:10.1037/0735-7028.19.4.416

- Clarke, A. M., & Jack, B. (1998). The benefits of using qualitative research. Professional Nurse, 13(12), 845–847.

- CASP. (2013). Critical Appraisal Skills Programme Qualitative Research Checklist. Retrieved 12 01, 2017, from http://www.casp-uk.net/.

- Cutcliffe, J., & Stevenson, C. (2008). Never the twain? Reconciling national suicide prevention strategies with the practice, educational, and policy needs of mental health nurses (parts one and two). International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 17(5), 341–362. doi:10.1111/j.1447-0349.2008.00557.x

- Darden, A. J., & Rutter, P. A. (2011). Psychologists’ experiences of grief after client suicide: A qualitative study. Omega, 63(4), 317–342. doi:10.2190/OM.63.4.b

- *Davidsen, A. S. (2011). And one day he’d shot himself. Then I was really shocked’: General practitioners’ reaction to patient suicide. Patient Education and Counseling, 85(1), 113–118. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2010.08.020

- Department of Health. (2012). Suicide prevention strategy for England. London: The Stationery Office.

- Ellis, T. E., & Patel, A. B. (2012). Client suicide: What now? Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 19(2), 277–287. doi:10.1016/j.cbpra.2010.12.004

- Fairman, N., Montross-Thomas, L. P., Whitmore, S., Meier, E. A., & Irwin, S. A. (2014). What did I miss: A qualitative assessment of the impact of patient suicide on hospice clinical staff. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 17(7), 832–836. doi:10.1089/jpm.2013.0391

- *Foggin, E., McDonnell, S., Cordingley, L., Kapur, N., Shaw, J., & Chew-Graham, C. A. (2016). GPs' experiences of dealing with parents bereaved by suicide: A qualitative study. British Journal of General Practice, 66(651), e737–e746. doi:10.3399/bjgp16X686605

- Fox, R. C., & Cooper, M. (1998). The effects of suicide on the private practitioner: A professional and personal perspective. Clinical Social Work Journal, 26(2), 143–157. doi:10.1023/A:1022866917611

- Gaffney, P., Russell, V., Collins, K., Bergin, A., Halligan, P., Carey, C., & Coyle, S. (2009). Impact of patient suicide on front-line staff in Ireland. Death Studies, 33(7), 639–656. doi:10.1080/07481180903011990

- *Gibbons, R., Brand, F., Carbonnier, A., Croft, A., Lascelles, K., Wolfart, G., & Hawton, K. (2019). Effects of patient suicide on psychiatrists: Survey of experiences and support required. BJPsych Bulletin, 43(5), 236–241. doi:10.1192/bjb.2019.26

- Grad, O. T., & Michel, K. (2005). Therapists as client suicide survivors. In K. M. Weiner, (Ed.), Therapeutic and legal issues for therapists who have survived a client suicide: Breaking the silence (pp. 71–82). New York: Haworth Press.

- Grad, O. T., Zavasnik, A., & Groleger, U. (1997). Suicide of a patient: Gender differences in bereavement reactions of therapists. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior, 27(4), 379–386. doi:10.1111/j.1943-278X.1997.tb00517.x

- Hall, P. (2005). Interprofessional teamwork: Professional cultures as barriers. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 19(sup1), 188–196. doi:10.1080/13561820500081745

- Harrison, S. L., Apps, L., Singh, S. J., Steiner, M. C., Morgan, M. D., & Robertson, N. (2014). ‘Consumed by breathing’ – a critical interpretive meta-synthesis of the qualitative literature. Chronic Illness, 10(1), 31–49. doi:10.1177/1742395313493122

- Hawton, K., Houston, K., Haw, C., Townsend, E., & Harriss, L. (2003). Comorbidity of Axis I and Axis II disorders in patients who attempted suicide. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 160(8), 1494–1500. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.160.8.1494

- Hendin, H., Haas, A. P., Maltsberger, J. T., Szanto, K., & Rabinowicz, H. (2004). Factors contributing to therapists’ distress after the suicide of a patient. American Journal of Psychiatry, 161(8), 1442–1446. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.161.8.1442

- Hendin, H., Lipschitz, A., Maltsberger, J. T., Haas, A. P., & Wynecoop, S. (2000). Therapists’ reaction to patients’ suicides. American Journal of Psychiatry, 157(12), 2022–2027. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.157.12.2022

- Henry, M., & Greenfield, B. J. (2009). Therapeutic effects of psychological autopsies: The impact of investigating suicides on interviewees. Crisis, 30(1), 20–24. doi:10.1027/0227-5910.30.1.20

- Hjelmeland, H., & Knizek, B. L. (2010). Why we need qualitative research in suicidology. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior, 40(1), 74–80. doi:10.1521/suli.2010.40.1.74

- *Hultsjö, S., Wärdig, R., & Rytterström, P. (2019). The borderline between life and death: Mental healthcare professionals’ experience of why patients commit suicide during ongoing care. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 28(9-10), 1623–1632. doi:10.1111/jocn.14754

- Johnstone, L., & Dallos, R. (2013). Formulation in psychology and psychotherapy: Making sense of people’s problems. London: Routledge.

- *Joyce, B., & Wallbridge, H. (2003). Effects of suicidal behaviour on a psychiatric unit nursing team. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services, 41(3), 14–23.

- Kable, A. K., & Spigelman, A. D. (2018). Why clinicians involved with adverse events need much better support. International Journal of Health Governance, 23(4), 312–315. doi:10.1108/IJHG-09-2018-0049

- Kahne, M. J. (1968). Suicide among patients in mental hospitals: A study of the psychiatrists who conducted their psychotherapy. Psychiatry: Journal for the Study of Interpersonal Processes, 31(1), 32–43. doi:10.1080/00332747.1968.11023532.

- Kendall, K., & Wiles, R. (2010). Resisting blame and managing emotion in general practice: The case of patient suicide. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 70(11), 1714–1720. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.01.045

- Knox, S., Burkard, W., Jackson, J. A., Schaack, A. M., & Hess, S. A. (2006). Therapists in training who experience a client suicide: Implications for supervision. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 37(5), 547–557. doi:10.1037/0735-7028.37.5.547

- Kolodny, S. (1979). The working through of patients’ suicides by four therapists. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behaviour, 9(1), 33–46.

- Kouriatis, K., & Brown, D. (2014). Therapists’ experience of loss: An interpretative phenomenological analysis. OMEGA – Journal of Death and Dying, 68(2), 89–109. doi:10.2190/OM.68.2.a

- Leaune, R., Ravella, N., Vieux, M., Poulet, E., Chauliac, N., & Terra, J. L. (2019). Encountering patient suicide during psychiatric training: An integrative, systematic review. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 27(3), 141–149. doi:10.1097/HRP.0000000000000208

- Leavey, G., Mallon, S., Rondon-Sulbaran, J., Galway, K., Rosato, M., & Hughes, L. (2017). The failure of suicide prevention in primary care: Family and GP perspectives – A qualitative study. BMC Psychiatry, 17(1), 1–10. doi:10.1186/s12888-017-1508-7

- Mackay, L. (1993). Conflicts in care: Medicine and nursing. London: Chapman and Hall.

- Mann, J. J., Apter, A., Bertolote, J., Beautrais, A., Currier, D., Haas, A., … Hendin, H. (2005). Suicide prevention strategies: A systematic review. JAMA, 294(16), 2064–2074. doi:10.1001/jama.294.16.2064

- McAdams, C. R., & Foster, V. A. (2000). Client suicide: Its frequency and impact on counsellors. Journal of Mental Health Counselling, 22(2), 107–121.

- McCabe, R., Garside, R., Backhouse, A., & Xanthopoulou, P. (2018). Effectiveness of brief psychological interventions for suicidal presentations: A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry, 18(1), 120 doi:10.1186/s12888-018-1663-5

- Midence, K., Gregory, S., & Stanley, R. (1996). The effects of patient suicide on nursing staff. J Clin Nurs, 5(2), 115–120. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2702.1996.tb00236.x

- Morrissey, J., & Higgins, A. (2019). “Attenuating Anxieties”: A grounded theory study of mental health nurses’ responses to clients with suicidal behaviour”. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 28(5–6), 947–958. doi:10.1111/jocn.14717

- NCISH: National Confidential Inquiry into Suicide and Homicide by People with Mental Illness. (2014). Suicide in primary care in England: 2002–2011. Manchester: University of Manchester.

- Ng, L., Steane, R., Scollay, N., Harris, S., Milosevic, J., Young, K., … Chow, S. (2019). The crucible of early career psychiatry. Australasian Psychiatry: Bulletin of Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists, 27(3), 245–248. doi:10.1177/1039856218810153

- Noblit, G. W., & Hare, R. D. (1988). Meta-ethnography: Synthesizing qualitative studies. Newbury Park: Sage.

- Norcross, J. C. (2000). Psychotherapist self-care: Practitioner-tested, research-informed strategies. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 31(6), 710–713. doi:10.1037/0735-7028.31.6.710

- Paterson, B. L., Thorne, S. E., Canam, C., & Jillings, C. (2001). Meta-study of qualitative health research: A practical guide to meta-analysis and meta-synthesis. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- *Pavlič, D. R., Treven, M., Maksuti, A., Švab, I., & Grad, O. (2018). General practitioners’ needs for support after the suicide of patient: A qualitative study. European Journal of General Practice, 24(1), 177–182. doi:10.1080/13814788.2018.1485648

- Pitman, A. L., Stevenson, F., Osborn, D. P. J., & King, M. B. (2018). The stigma associated with bereavement by suicide and other sudden deaths: A qualitative interview study. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 198, 121–129. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.12.035

- Public Health England. (2016). Suicide prevention: Developing a local action plan. London: PHE.

- *Robertson, M., Paterson, B., Lauder, B., Fenton, R., & Gavin, J. (2010). Accounting for accountability: A discourse analysis of psychiatric nurses’ experience of a patient suicide. The Open Nursing Journal, 4(1), 1–8. doi:10.2174/1874434601004010001

- Ruskin, R., Sakinofsky, I., Bagby, R. M., Dickens, S., & Sousa, G. (2004). Impact of patient suicide on psychiatrists and psychiatric trainees. Academic Psychiatry: The Journal of the American Association of Directors of Psychiatric Residency Training and the Association for Academic Psychiatry, 28(2), 104–110. doi:10.1176/appi.ap.28.2.104

- *Saini, P., Chantler, K., While, D., & Kapur, N. (2016). Do GPs want or need formal support following a patient suicide?: A mixed methods study. Family Practice, 33(4), 414–420. doi:10.1093/fampra/cmw040

- Sanders, S., Jacobson, J., & Ting, L. (2005). Reactions of mental health social workers following client suicide completion: A qualitative investigation. OMEGA – Journal of Death and Dying, 51(3), 197–216. doi:10.2190/D3KH-EBX6-Y70P-TUGN

- Schneidman, E. (1971). Prevention, intervention and postvention. Annals of Internal Medicine, 75(3), 453–458.

- Scott, S. D., Hirschinger, L. E., Cox, K. R., McCoig, M., Brandt, J., & Hall, L. W. (2009). The natural history of recovery for the healthcare provider “second victim” after adverse patient events. Quality and Safety in Health Care, 18(5), 325–330. doi:10.1136/qshc.2009.032870

- Séguin, M., Bordeleau, V., Drouin, M., Castelli-Dransart, D. A., & Giasson, F. (2014). Professionals’ reactions following a patient’s suicide: Review and future investigation. Archives of Suicide Research, 18(4), 340–362. doi:10.1080/13811118.2013.833151

- Shaw, R. (2011). Identifying and synthesizing qualitative literature. In D. Harper, & A. R. Thompson (eds), Qualitative research methods in mental health and psychotherapy: A guide for students and practitioners (pp. 9–22). Chichester: Wiley.

- Sherba, R. T., Linley, J. V., Coxe, K. A., & Gersper, B. E. (2019). Impact of client suicide on social workers and counselors. Social Work in Mental Health, 17(3), 279–301. doi:10.1080/15332985.2018.1550028

- Spencer, J. (2007). Support for staff following the suicide of a patient. Mental Health Practice, 10(9), 28–32. doi:10.7748/mhp2007.06.10.9.28.c4311

- Spiegelman, J. S., & Werth, J. L. (2005). Don’t forget about me: The experiences of therapists-in-training after a client has attempted or died by suicide. In K. M. Weiner (Ed.), Therapeutic and legal issues for therapists who have survived a client suicide: Breaking the silence (pp. 35–57). New York: Haworth Press.

- Stanistreet, D., Gabbay, M. B., Jeffrey, V., & Taylor, S. (2004). The role of primary care in the prevention of suicide and accidental deaths among young men: An epidemiological study. British Journal of General Practice, 54(501), 254–258.

- Strobl, J., Panesar, S., Carson-Stevens, A., McIldowie, B., Ward, H., & Cross, H. (2014). Suicide by clinicians involved in serious incidents in the NHS: A situational analysis. Salford: Salford Royal NHS Foundation Trust Clinical Leaders Network.

- Talseth, A. G., & Gilje, F. L. (2011). Nurses’ responses to suicide and suicidal patients: A critical interpretive synthesis. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 20(11–12), 1651–1667. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03490.x

- *Talseth, A. G., & Gilje, F. (2007). Unburdening suffering: Responses of psychiatrists to patients’ suicide deaths. Nursing Ethics, 14(5), 620–636. doi:10.1177/0969733007080207

- Talseth, A. G., Jacobsson, L., & Norberg, A. (2000). Physicians’ stories about suicidal psychiatric inpatients. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 14(4), 275–283.

- Taylor, C., Graham, J., Potts, H., Candy, J., Richards, M., & Ramirez, A. (2007). Impact of hospital consultants’ poor mental health on patient care. British Journal of Psychiatry, 190(3), 268–269. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.106.023234

- Tillman, J. G. (2006). When a patient commits suicide: An empirical study of psychoanalytic clinicians. The International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, 87(Pt 1), 159–177. doi:10.1516/6ubb-e9de-8ucw-uv3l

- Türkleş, S., Yılmaz, M., & Soylu, P. (2018). Feelings, thoughts and experiences of nurses working in a mental health clinic about individuals with suicidal behaviours and suicide attempts. Collegian, 25(4), 441–446. doi:10.1016/j.colegn.2017.11.002

- Valente, S. M., & Saunders, J. M. (2009). Nurses’ grief reactions to a patient’s suicide. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care, 38(1), 5–14. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6163.2002.tb00650.x

- *Wang, S., Ding, X., Hu, D., Zhang, K., & Huang, D. (2016). A qualitative study on nurses’ reactions to inpatient suicide in a general hospital. International Journal of Nursing Sciences, 3(4), 354–361. doi:10.1016/j.ijnss.2016.07.007

- World Health Organization. (2020). Mental Health: Suicide Data. World Health Organization. Retrieved February 23, 2020 from https://www.who.int/mental_health/prevention/suicide/suicideprevent.

- Wu, A. W. (2000). Medical error: The second victim. The doctor who makes the mistake needs help too. BMJ, 320(7237), 726–727. doi:10.1136/bmj.320.7237.726

- Zalsman, G., Hawton, K., Wasserman, D., van Heeringen, K., Arensman, E., Sarchiapone, M., … Zohar, J. (2016). Suicide prevention strategies revisited: 10-year systematic review. The Lancet. Psychiatry, 3(7), 646–659. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30030-X

- Zimmer, L. (2006). Qualitative meta-synthesis: A question of dialoguing with texts. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 53(3), 311–318. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.03721.x