Abstract

Objective

To identify seasonal and temporal variations in daily incidence of homicides and suicides in Cali and Manizales, Colombia during 2008–2015.

Materials and methods

An ecological time series study was performed using negative binomial regression models for daily incidence of homicides and suicides; analyses were controlled for yearly trends and temporal autocorrelations.

Results

Saturdays, Sundays, December holidays as well as New Year and New Year’s Eve were associated with an increased risk of homicides in both cities. Suicide risk increased during December holidays and New Year in both cities. In addition, the suicide risk increased on paydays, Saturdays, Sundays, and Mondays in Cali, and it decreased during the Holy Week holidays in Manizales. December patterns of suicides and homicides are the opposite in each city, and between cities.

Conclusions

The incidences of homicides and suicides are not homogeneous over time. These patterns can be explained partially by alcohol consumption and changes in people’s routine activities which may modify exposure to violent circumstances.

INTRODUCTION

Suicides and homicides are external injuries that are a public health problem which generate serious social and economic consequences for the relatives of victims and their societies (Krug, Mercy, Dahlberg, & Zwi, Citation2002). In Colombia, homicides have been a serious problem for the past 60 years. The Colombian homicide rates were surpassed by those in other Latin American countries only during the 21st century (Guerrero & Fandiño-Losada, Citation2017). Between 2007 and 2016, Colombia recorded 273,649 violent deaths, where homicides were the leading cause, registering rates as high as 39.39 homicides/100,000 inhabitants in 2009. On the other hand, the rate of suicides was 5.20 suicides/100,000 inhabitants in 2016 (Instituto Nacional de Medicina Legal y Ciencias Forenses, Citation2016). Cali, the third largest city in the country and the capital of the Valle del Cauca province, has historically presented high homicide rates compared to other Colombian cities, although its suicide rates are low (Concha-Eastman, Espitia, Espinosa, & Guerrero, Citation2002; Fandiño-Losada, Citation2018; Sánchez et al., Citation2011; Villaveces et al., Citation2000). For instance, comparing Cali with the national figures, homicide and suicide rates in 2016 were 55.74 and 3.70/100,000 inhabitants, respectively. On the other hand, Manizales, the capital of the Caldas province, is a middle-sized city, with high suicide rates compared with the national mean, e.g., 6.45/100,000 inhabitants in 2016 (Instituto Nacional de Medicina Legal y Ciencias Forenses, Citation2016).

The seasonal patterns of suicides and homicides have been studied since the 19th century. In countries with temperate or cold climate, this seasonal pattern is explained by the strong variations in the weather related to the seasons and the way it influences human activities (Christodoulou et al., Citation2012; Partonen, Haukka, Nevanlinna, & Lönnqvist, Citation2004). Climatic variations have been associated with higher suicide rates, which are reported at the beginning of Spring and Autumn, as well as during the Winter (Ajdacic-Gross, Bopp, Ring, Gutzwiller, & Rossler, Citation2010; Rock, Judd, & Hallmayer, Citation2008).

It has also been found that violent crimes are influenced by seasonal and temporal variables such as vacations, the end of the school year, paydays and holidays (Ajdacic-Gross et al., Citation2010; Cohn & Rotton, Citation2003). Many of these patterns are associated with temporal changes in alcohol consumption, including weekends, holidays, cultural and commercial celebrations, public demonstrations and paydays (Ajdacic-Gross et al., Citation2010; Rodriguez, Citation2008; Sánchez et al., Citation2011; Villaveces et al., Citation2000).

Recently, studies have focused on seasonal and temporal patterns of suicides and homicides in countries with subtropical and tropical weather, such as Brazil and Singapore. Seasonal variations seem not to be significant, although there are differential patterns of suicides and homicides on different days of the week (Ceccato, Citation2005; Parker, Gao, & Machin, Citation2001; Pereira, Andresen, & Mota, Citation2016). In Colombia, it has been reported that about 32% of homicides in the country are related to recreational activities, cultural events and sports which mainly occur on Saturdays and Sundays (Instituto Nacional de Medicina Legal y Ciencias Forenses, Citation2016). Regarding suicides, peaks are observed in August and December (holiday season) and on Sundays and Mondays (Instituto Nacional de Medicina Legal y Ciencias Forenses, Citation2016). In Cali, it has also been found that homicide rates are higher during weekends, holidays, and weekends after paydays (Concha-Eastman et al., Citation2002; Sánchez et al., Citation2011; Villaveces et al., Citation2000).

Although some seasonal and temporal variables that may influence the homicides and suicides occurrence have been addressed in tropical countries, it is necessary to perform studies at the city level using time series regression, given the auto-correlated nature of the time series data (Bernal, Cummins, & Gasparrini, Citation2017; Fandiño-Losada, Citation2018). Thus, the objective of this study was to identify seasonal and temporal variations on the incidence of suicides and homicides in Cali and Manizales, Colombia, between 2008 and 2015.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Design

It is an ecological study of violent deaths that occurred in the municipalities of Cali and Manizales, Colombia, using time series analyses from 2008 to 2015. This study was approved by the Human Ethics Institutional Review Committee (Acronym in Spanish: CIREH) of the Universidad del Valle, Colombia (Internal Codes 042–017 and 010-017).

Mortality Data

Anonymized data on all deaths classified as homicides and suicides were requested from the External Caused Deaths Surveillance System (Acronym in Spanish: SVMCE) of Cali (Sánchez-Rentería, Bonilla-Escobar, Fandiño-Losada, & Gutiérrez-Martinez, Citation2016), coordinated by the Security Observatory of the Municipality of Cali (Colombia). An injury event could lead to a death of external causes on the same day or the days following the event (Demetriades et al., Citation2005). In order to carry out this study, we collected the dates of the violent events (interpersonal and self-inflicted) which consequently ended in homicide or suicide cases during the same day or the following days (up to 30 days according to SVMCE definitions). Manizales data were obtained from the Colombian Government open data repository (datos.gov.co), which indicates the dates of suicide deaths and homicide cases. Concerning the data on Cali, the daily counts of the external caused events were summed up as homicide events and suicide events, considering the date of each event instead of the date of death (i.e., the mortality date). In Manizales, due to lack of data on dates of external caused events, the daily counts were summed up according to the dates of death. The days during which no homicide or suicide occurred were assigned as zero (0). The data were organized along two time series of daily counts of homicides and suicides, from January 1st, 2008, to December 31st, 2015.

Explanatory Variables

For each date, year and month were considered in analyses. In addition, days of the week (Sunday to Monday), national holidays and labor paydays (each two weeks) were indicated according to the Legislation of the Republic of Colombia. In Colombia, there are 18 official national holidays of civil or religious nature, ten of which are moved to the Monday following the holiday (a movable holiday) and the remaining eight are celebrated on the original day of the week (an unmovable holiday), according to Law 51/1983 or “Emiliani Law” (Congreso de la República de Colombia, Citation1983).

The movable holidays are the New Year (January 1st), the Maundy Thursday (or the Last Supper, a Thursday in March or April), Good Friday (a Friday in March or April), Labor Day (May 1st), National Independence Day (July 20th), the Battle of Boyacá (August 7th), the Immaculate Conception (December 8th) and Christmas (December 25th). Paydays correspond to the first business day (Monday to Friday) after the 14th day and the last day of each month. In this study, the three largest commercial celebrations, which are not official national holidays, were also considered: Mother’s Day (second Sunday in May), Father’s Day (second or third Sunday in June) and Day of Love and Friendship (similar to the Valentine’s Day, but the second or third Saturday of September). Finally, two periods of days were identified: first, the annual celebrations of each city’s carnival: “Feria de Cali” which runs between December 25th and 30th or “Feria de Manizales” which takes place on the weekends before and after the Feast of the Epiphany (January 6th) as well as the days in between. Second, the eight days of the “Holy Week” (in Spanish: “Semana Santa,” a Catholic religious tradition), from Palm Sunday to Easter Sunday.

Lunar phases were operationalized as the day of full moon ± 1 day (i.e., three days of full moon) and the day of new moon ± 1 day (i.e., three days of new moon). The days in the moon cycle between the new and the full moon (including the first quarter) were assigned as the waxing phase. The rest of days in the moon cycle between the full and the new moon (including the third quarter) were assigned as the waning phase.

Statistical Analysis

Daily counts of each outcome event (i.e., suicides and homicides) were determined for the seasonal (i.e., month) and temporal explanatory variables (see the Electronic Supplementary table 1). Suicide and homicide incidence rates were calculated in terms of person-years of exposure, estimating the denominator as follows: addition of the yearly half period population (on June 30th) over the 8 years times the exposure time fraction of each seasonal or temporal variable (see ). The latter was calculated as the ratio between the numbers of days observed for each option of the seasonal and temporal variables (e.g., 78 days of movable holidays) over the total count of days in the study period (i.e., 2,922 days).

TABLE 1. Rates of homicides and suicides in Cali and Manizales, Colombia, 2008–2015.

Furthermore, the outcome variables (daily counts of violent events) were modeled by means of time series regressions (Bernal et al., Citation2017; Bhaskaran, Gasparrini, Hajat, Smeeth, & Armstrong, Citation2013; Yu et al., Citation2020), using negative binomial regression models for each event count (i.e., daily counts of homicides and daily counts of suicides) in each city (Cali and Manizales), with offset of natural logarithm of the daily projection of each city’s population (in person-years units) as the model denominator. The measure of effect for the negative binomial regression is the adjusted Incidence Rate Ratio (aIRR), interpreted as the percentage change in the daily count of homicides or suicides, in relation to the reference categories, adjusted for the other covariables in each regression model (see and , for suicides and homicides, respectively). The differences between saturated models (which include all variables in ) versus more parsimonious models were compared using the Bayesian information criterion (BIC). The final multiple regression models used the explanatory seasonal (i.e., month) and temporal variables of , while controlling for the other explanatory variables in each table as well as controlling for the long-term trend (years) and the significant time lags of response residuals of each regression model, according to (López) Bernal et al., Citation2017 (see their Supplementary material). In addition, the temporal autocorrelations among the adjacent time series observations were controlled by means of the autocorrelation consistent (HAC) variance estimate, using lags up to 32 days (StataCorp., Citation2015).

TABLE 2. Temporal variables effects on suicide rates in Cali and Manizales, Colombia, 2008–2015.

TABLE 3. Temporal variables effects on homicide rates in Cali and Manizales, Colombia, 2008–2015.

For official national holidays and commercial celebrations, the effect of the previous day (i.e., the day eve) and the following day (one day afterwards) were explored using a temporal forward and a temporal lag, respectively. For the final negative binomial regression models, distributions of their residuals were explored graphically against the predicted data, checking their temporal independence using correlograms, partial correlograms and the Bartlett’s periodogram-based test for white noise (please, see the Electronic Supplementary material). The analyses of homicides were not sub-divided by sex because most of victims were men: 94.0% in Cali and 93.6% in Manizales. As the daily mean of suicides was very low (0.25 suicides/day in Cali and 0.07 suicides/day in Manizales), this outcome variable was not divided by sex. The analyses were performed in Stata® version 14.2 (StataCorp., 2015).

RESULTS

From 2008 to 2015, there were 13,824 homicides in Cali and 1,047 in Manizales. During the same period, there were 737 suicides in Cali and 213 in Manizales. Of the 2,922 days observed in this study, there were 80 days (2.74%) without homicides in Cali and 2,113 days (72.31%) without homicides in Manizales. Among days with homicides, between one and 22 deaths occurred in Cali, with a mean of 4.86 cases/day (95% Confidence Interval [CI] = 4.76 − 4.96). In Manizales, one to eight cases occurred in days with homicides, with a mean of 1.29 cases/day (95%CI = 1.25 − 1.34). In Cali, suicide events occurred on 638 (21.83%) of the observed days and there were between one to four suicides on these days with a mean of 1.15 cases/day (95%CI = 1.12 − 1.19). In Manizales, suicides occurred on 203 (6.95%) of the observed days and there were one or two suicides on these days with a mean of 1.05 (95%CI = 1.02 − 1.08).

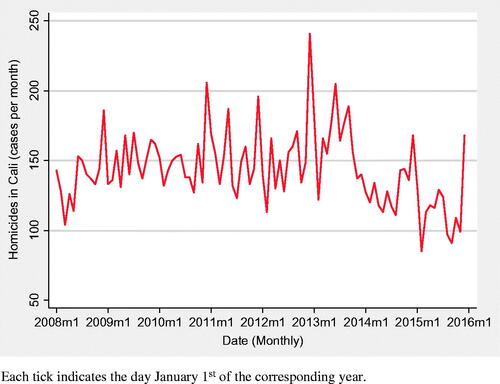

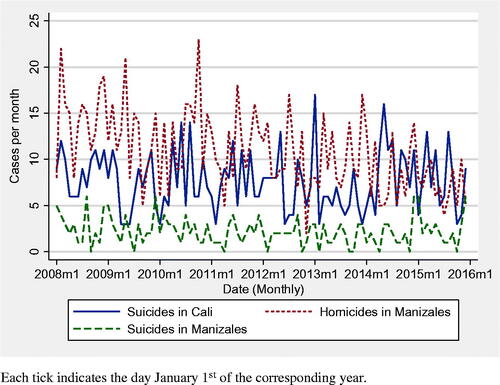

In Cali, the homicide rate for the entire study period was 75.72 cases/100,000 person-years (100KPY) and the suicide rate was 4.04 cases/100KPY. In Manizales, the homicide rate for the entire study period was 33.48 cases/100,000 person-years (100KPY) and the suicide rate was 6.81 cases/100KPY. Although both cities have a decreasing trend in both homicides and suicides (see and and ), some years had higher rates outside of this trend. The year with the highest homicide rate in Cali was 2013 (84.88/100KPY) and the lowest was 2015 (58.19/100KPY). On the other hand, suicide rates were high in Cali during 2014 (4.69/100KPY) and in Manizales during 2015 (7.83/100KPY). The adjusted effects of the years on suicides and homicides are shown in and of the Electronic Supplementary material.

FIGURE 2. Monthly counts of suicides in Cali and suicides and homicides in Manizales, Colombia, 2008–2015.

Regarding other seasonal and temporal variables, incidence analyses indicated that the highest homicide rates in Cali were observed in December, on Saturdays and Sundays, on the eve of December holidays (i.e., Immaculate Conception, Christmas, and the New Year included as a December holiday) and the eve of movable holiday, on December holidays, on days of commercial celebrations as well as the following day, and during the Cali’s Carnival. In contrast, in Cali the lowest rates of homicides were observed on Wednesday, paydays and during the “Holy Week” holidays (see ). In Manizales, the highest homicide rates were observed in December, on Saturdays and Sundays, on the eve of December holidays and the eve of movable holidays, on December holidays, on days of commercial celebrations and the following day, as well as during the Cali Carnival. In contrast, in Manizales, the lowest rates of homicides were observed in October, the “Holy Week” holidays and the first day afterwards, on days of commercial celebrations, and during the New Moon phase (see ).

In Cali, the highest suicide rates occurred on Sundays and Mondays, during December and New Year holidays, the days after other unmovable holidays, and during the Cali Carnival. In contrast, the lowest rates of suicides occurred in July, on Fridays, and on the Holy Week holidays and their eves, the eve of unmovable holidays, and the days before and after commercial celebrations (see ). In Manizales, the highest suicide rates occurred in December and January, and during the Manizales’s Carnival. In addition, the highest suicide rates occurred on Fridays and Sundays, on the eve of December holidays, on December holidays and the days afterwards, as well as the days of before and after commercial celebrations. In contrast, the lowest rates of suicides occurred in July, on Wednesdays, the eve of unmovable holidays, on movable holidays, and the day before commercial celebrations (see ).

According to , it was found that in Cali the adjusted risks of suicides were higher on Saturdays, Sundays, and Mondays, on paydays, on December holidays, on the first day after paydays, on days after other unmovable holidays (i.e., excluding December and the New Year) and during the Cali’s Carnival; although the last three adjusted incidence rate ratios were marginally significant (p < 0.10, see ). In Manizales, the adjusted risks of suicides were lower on the “Holy Week” holidays and the first day afterwards, and the adjusted risks were higher (at p < 0.10 level) during December, and on December holidays and the first day afterwards.

According to , the adjusted risks of homicides were higher on Saturdays and Sundays, and on December holidays in both cities. Additionally, in Cali the adjusted risks of homicides were higher in December, on Fridays, on eves of December holidays, and on the first day following commercial celebrations. The higher risks of homicides were marginally significant on Mondays and Thursdays. On the other hand, the risk of homicides was lower on the “Holy Week” holidays in Cali. In contrast, in Manizales the adjusted risks of homicides were higher on paydays, and on the other unmovable holidays and during the Waxing Moon phase. The adjusted risks of homicides were lower in June, and marginally lower in August and on the first day after commercial celebrations.

In the post-hoc analysis, the most important festivities and celebrations were explored in detail for the Cali data, and a greater risk of homicide was found on the eves of and during the Christmas and New Year holidays, the day of the “Immaculate Conception” (a December holiday) and the first day after the Mother’s Day. There was a lower risk of homicides on the “Good Friday.” Regarding suicides, Mother’s Day and Christmas Day were found to have greater suicide risks.

DISCUSSION

The findings indicate that homicides in Cali have a seasonal pattern with an increase in the number of cases by 23% in December compared to February. This could be explained by the commercial activities that take place during this month that may increase violent robberies and other events. Furthermore, other factors such as a higher consumption of alcohol during the festivities of December and New Year (Rodriguez, Citation2008; Sánchez et al., Citation2011) could play a role. In contrast, in Manizales homicides decreased 31% in June compared to February, which is probably related with the vacations period in the middle of the year. Due to the local climates in Cali and Manizales, Colombia, it is unlikely that differences in the incidence of homicides and suicides were explained by weather differences throughout the year (e.g., the seasons), as it has been found in countries with temperate or cold climate patterns (Pereira et al., Citation2016; Rodriguez, Citation2008), although rainy patterns could play a role at the local context (see below).

Studies in Brazil indicate that crime levels and homicide rates are higher during vacations, which coincide with the warmer months of the year, although temperature variations are modest there (Pereira et al., Citation2016). Therefore, in tropical and subtropical climates, it is more plausible that seasonal variations of homicides incidence are explained by the seasonal changes in human routines and activities, due to Christmas and the end of year celebrations and other holiday periods; instead of the seasonal changes due to the climate (Ceccato, Citation2005; Cohen & Felson, Citation1979). In contrast, temperature changes due to seasons contributes to the temporal changes of violent crimes observed in countries with temperate and cold climates (Cohn & Rotton, Citation2003; Rock et al., Citation2008).

The seasonality found in this study (gauged over the months of the year) is similar to that found in studies of other countries, where the violent deaths were associated with alcohol and psychoactive substances use and abuse, and with carrying of firearms which are common factors during the aforementioned celebrations (Cohn & Rotton, Citation2003; Rock et al., Citation2008; Rodriguez, Citation2008; Villaveces et al., Citation2000). In fact, alcohol abuse increases the likelihood of violent behavior, thus the risk of homicides and suicides increases, particularly on weekends and on days near to holidays (Baird et al., Citation2019; Krug et al., Citation2002; Mäkelä, Martikainen, & Nihtilä, Citation2005; Sánchez et al., Citation2011).

The observed weekly and daily patterns for homicides indicate that they are increased on Fridays, Saturdays, Sundays and Mondays, eves of unmovable holidays and unmovable holidays (especially Christmas and New Year), and the days after commercial celebrations (especially Mother’s Day). According to the classic theory of Cohen and Felson (Cohen & Felson, Citation1979), changes in human routines and behaviors due to traditions or cultural activities (which are associated with holidays, carnivals, and other celebrations) alter the victims’ exposure to perpetrators, increasing their likelihood of being more vulnerable to crimes such as thefts and homicides (Cohn & Rotton, Citation2000, Citation2003).

In this study, unmovable holidays during the period of religious celebration of the “Holy Week” seems to have a protective effect, decreasing the incidence of homicides by 35% in Cali, and decreasing the risk of suicides in Manizales by almost the 100%. In contrast, studies in the United States of America (USA) showed that during important religious holidays, such as the Easter, homicides had a higher relative occurrence in relation with other dates, without changes in suicides (Lester, Citation1987). The last pattern of occurrences could be explained, precisely, by the theory of routine activities (Cohen & Felson, Citation1979), due to cultural traditions altering the exposure to crime situations. The lower risk of homicides during the “Holy Week” observed in this study could be due to a lower alcohol intake, which is a risk factor for homicides (Sánchez et al., Citation2011).

Differences of seasonal and temporal patterns of homicides between cities could be understood considering the higher proportion of young population in Cali, along with a lower coverage in education (Sandoval, Citation2018). The dynamic of violence in Cali has been conceptualized as a regressive tax because it occurs more frequently in areas of low socioeconomic status and function as a systematic form of social distancing (Burbano Valencia & Zafra Sanz, Citation2016). Additionally, a significant level of urban violence has been recognized and the influence of drug trafficking has allowed the development of criminal gangs that have had a major effect on homicides in Cali and other Colombian cities (Poveda, Citation2012). In Cali, homicides reflect the structural aspects of organized crime throughout the country, magnified in the city due to its geographic location (Fandiño-Losada, Guerrero-Velasco, Mena-Muñoz, & Gutiérrez-Martínez, Citation2017). In the case of Manizales, homicides have been explained as issues derived from fights and interpersonal aggressions (Gallego-Jiménez, Citation2012).

Regarding suicides, the seasonal pattern was opposite in relation to December, with a higher risk in Manizales (+65%) and a lower risk in Cali (-34%). Manizales findings are consistent with the higher spring incidence found in other countries, due to that both periods are vacations time. Although, in those countries increase in suicides seems to be related to sudden temperature variations during moderately cold seasons (i.e., beginning of spring, beginning of autumn) (Ajdacic-Gross et al., Citation2010; Casey, Gemmell, Hiroeh, & Fulwood, Citation2012; Yu et al., Citation2020).

In this relationship of weather and suicide, Bando, Scrivani, Morettin, and Teng (Citation2009) explain on the hypothesis that serotonergic neurons are associated with thermoregulatory responses, and that through generalized connections with the Limbic System, they can play a role in cognitive functions and mood (Lowry, Lightman, & Nutt, Citation2009). Other authors hypothesized that climatic variations and the duration of sunlight may affect the binding of 5-HT 1 A receptors in the cortical and subcortical limbic regions of the human brain and that they play a central role in serotonin transport (Spindelegger et al., Citation2012). Furthermore, other scholars report a positive relationship between high peak temperatures and suicides in India (Gaxiola-Robles, Celis de la Rosa, Labrada-Martagón, Díaz-Castro, & Zenteno-Savín, Citation2013); although high peak temperatures are associated with lower crop yields; hence, it ends up being explained as economic suicides (Carleton, Citation2017). Contradictory findings are found in a study that takes data from Cali and four other cities in Colombia (Fernández-Niño, Flórez-García, Astudillo-García, & Rodríguez-Villamizar, Citation2018), because its results did not find a significant relationship between suicides and weather variations. Thus, the literature is not entirely conclusive in this respect. However, differences in previous findings can be explained by the application of different methodologies and by the geographic location of each study (Dixon & Kalkstein, Citation2018).

In tropical zones of Brazil, a seasonal pattern of six months of an increased rate of suicides has been found, however it does not correspond to the seasonality of the cold countries (Bando et al., Citation2009; Benedito‐Silva, Nogueira Pires, & Calil, Citation2007). Also, in Bogotá, Colombia (which has a high-altitude tropical climate), a seasonal behavior of suicides is seen, with peaks during the second semester of the year (Moreno Montoya & Sánchez Pedraza, Citation2009), which could be related with annual cycles of rains and drought. However, the findings of seasonal cycles in tropical countries are not entirely consistent.

In contrast, our findings show that in Cali the suicide risk was lower in December, with exception of its holidays (also, including the New Year) when the suicide risk increased by 26% on the eves of holidays and by 167% on the holidays. In Manizales, the increased risk effects of December holidays (also, including the New Year) and the first day afterwards are marginally significant. Furthermore, in Cali the risk of suicides was higher on paydays and the first day afterwards. The higher risk of suicides on holidays and paydays could be explained by the mixture of several factors such as the increase in alcohol consumption that elevates suicide attempts (Akkaya-Kalayci, Popow, Waldhör, & Özlü-Erkilic, Citation2015; Boenisch et al., Citation2010; Gonçalves, Ponce, de, & Leyton, Citation2018), in addition to increase in psychopathology and mood variations and decrease in the use of psychiatric emergencies during the holidays (Sansone & Sansone, Citation2011). That suicides occur after the holidays or after the December month, as it does in Manizales and Cali respectively, may be due to a broken promise postponement effect (Gabennesch, Citation1988; Jessen & Jensen, Citation1999; Ploderl et al., Citation2015). Additionally, the higher risk of suicides in relation with paydays could be explained by the effects of economic factors on persons’ mental health, especially on those unemployed (Nordt, Warnke, Seifritz, & Kawohl, Citation2015).

In relation to the days of the week, the risk of suicide in Cali was higher on Saturdays, Sundays, and Mondays. Moreover, the risk of suicide in Cali increased by 62% on days following unmovable holidays, although the effect was marginally significant. Studies conducted in Hungary and Italy also show the same pattern in relation to these days (Preti & Miotto, Citation1998; Zonda, Bozsonyi, Veres, Lester, & Frank, Citation2009), and in the USA a similar pattern was found for suicide attempts by poisoning (Beauchamp, Ho, & Yin, Citation2014). In South Korea, Monday is the day with the highest probability of suicides (Kim et al., Citation2019) which could be explained by the theory of Gabennesch (Citation1988). This theory indicates that suicides occur mainly on days when people have expectations of change in their lives and routines (e.g., “Monday blues”); on these days there is a greater risk of severe depressive episodes when these expected changes did not occur. In addition, the increased risk of suicide on Sundays, unmovable holidays, and the Cali Carnival may be explained by high alcohol use during these celebrations, which could worsen the psychiatric conditions that lead to people to commit suicide (Sánchez, Orejarena, & Guzmán, Citation2004; Sánchez Pedraza, Tejada Neira, & Guzmán Sabogal, Citation2008). Another explanation generated by similar findings in the case of Barranquilla Carnival (Colombia) (Guarin-Ardila, Montero-Ariza, Astudillo-García, & Fernández-Niño, Citation2020), assumes that suicide risk increases due to changes in routine activities leading to an increase in problematic human interactions.

In this study, unmovable holidays during the period of religious Catholic celebrations of the “Holy Week” have a protective effect, decreasing the incidence of suicides in Manizales by almost the 100%. These results are also observed in the patterns of suicide in Switzerland and Austria in periods 1969–2010 and 1970–2010, respectively, and their explanations are supported by the social control and the increased contact with relatives and friends during these festivities (Ajdacic-Gross et al., Citation2010; Beauchamp et al., Citation2014; Voracek et al., Citation2008). According to a study in the USA, there may be a cultural effect of religious beliefs influencing perspectives of life, implying an apparent protection against suicide through religiosity and people’s spiritual well-being (Walker, Lester, & Joe, Citation2006).

Many studies aimed to find a relationship between the full moon and different aspects of human health, such as suicide, homicide, or any erratic behavior, finding no correlations (Roy, Biswas, & Roy, Citation2017), so they encourage further research along these lines. Specifically, on the relation between the moon phases (or moon cycle) and suicides and homicides the findings are not recent; a study in Texas (USA), during 1959 to 1961, showed no significant associations, after stratification by day, race, and sex (Pokorny, Citation1964). A similar study (Mathew, Lindesay, Shanmuganathan, & Eapen, Citation1991) analyzed the association between moon phases and suicide attempts, without controlling by weekends or holidays; but its results did not support the associations. In our study, we also tested the moon phases hypothesis by time series analyses; but surprisingly no effect was found for suicide risk. Our results are in line with previous findings (Kmetty, Tomasovszky, & Bozsonyi, Citation2018; Mathew et al., Citation1991; Roy et al., Citation2017; Voracek et al., Citation2008). Nonetheless, in Manizales the waxing moon days were related with an increased risk of homicides by 21%. The local cultural aspects could explain to some extent these findings, because in more rural settings the attributing beliefs regarding the Moon affect some human behaviors and practices (Kelly, Rotton, & Culver, Citation1986).

Finally, in this study we have analyzed the effects of seasonal and temporal variables on homicides and suicides rates altogether. This approach allows to test sociological theories on the homicides and suicides phenomena, such as the one proposed by He, Cao, Wells, and Maguire (Citation2003), who framed suicides and homicides as a single form of violence called “lethal violence,” explaining that the unique difference between the two phenomena is their direction either outwards (homicides) or inwards (suicides). Moreover, the explanation is found both in the economic production, considering a common cause appealing to economic variables such as inequality and wealth, but also integrating the social thesis of the “strength of the relational system,” which He et al. define as the level of relationships of a person with others (He et al., Citation2003). In this manner, we have found that suicides and homicides share common seasonal and temporal patterns in relation with days of the week (higher risk on Saturdays, Sundays, and Mondays) and holidays (higher risk on the eves of December and New Year holidays and during these holidays, and lower risk on holidays of the Holy Week). Nonetheless, seasonality shows opposite patterns for suicides and homicides, and showing opposite patterns between cities: December has a higher risk of homicides and a lower risk of suicides in Cali, with the opposite situation in Manizales, although the seasonal effects were marginally significant in the last city. More research is needed on these contrasting seasonal patterns between suicides and homicides, and on the contrasting patterns between cities.

This study has some limitations: Day/night periods are related to homicide patterns (Sánchez et al., Citation2011), but there were no data available to be included in the time series analyses, thus the smallest unit of analysis was the day. In addition, it was observed that seasonal patterns are related to climatic variables (e.g., seasonal rains) (Butke & Sheridan, Citation2010), even in tropical zones, which were not included in this study. Furthermore, the analyses of both Manizales’ time series and suicides time series in Cali could have had lower statistical power due to the small number of daily counts of deaths. Finally, alcohol use is related with homicides and suicides, unfortunately we do not have data available on alcohol consumption at the study ecological level.

This study has several strengths: Cali is a city with high homicide rates and Manizales is a city with high suicide rates (in the Colombian context), whose seasonal and temporal patterns had not been studied beyond descriptive statistics. In this regard, we analyzed these seasonal and temporal variables using time series regressions, following the most recent methodological advances (Bernal et al., Citation2017; Bhaskaran et al., Citation2013; Yu et al., Citation2020). Additionally, the SVMCE of Cali gave us access to reliable data with the exact dates of violent events leading to mortality by homicides and suicides, irrespective of the date of death (Concha-Eastman et al., Citation2002). The date of the violent event and the date when people died did not necessarily coincide (Demetriades D; Mäkelä et al., Citation2005), therefore knowing the exact date of the violent event decreases the estimation errors due to information biases.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, the incidences of homicides and suicides are not homogeneous over time, and they are influenced by seasonal and temporal factors such as months, days of the week, eves of holidays (civil and religious), holidays (civil and religious), carnivals, religious periods and commercial celebrations. These patterns could be explained by differences in alcohol use and abuse during these days and by changes in people’s routine activities during weekends and festivities that modify their exposure to violent environments. These results are very important for designing and planning interventions for suicide prevention and promotion of mental health, e.g., increasing the availability of counseling phone lines during weekends and holidays (Arendt & Scherr, Citation2017).

OK_Electronic_Suppl_Material_USUI_2020_0208_Jun_2021.docx

Download MS Word (159.2 KB)ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank the Security Secretariat of the Cali Mayor’s Office and the External Caused Deaths Surveillance System of Cali (in Spanish, SVMCE) for allowing access to the data.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Lucy Nieto-Betancurt

Lucy Nieto-Betancurt, Ps, MPH, Student of the Doctoral Program in Health, Universidad del Valle, Cali, Colombia; Lecturer Universidad Católica de Pereira, Pereira, Colombia.

Andrés Fandiño-Losada

Andrés Fandiño-Losada, MD, MSc, PhD, CISALVA Institute Researcher & Associate Professor School of Public Health, Universidad del Valle, Cali, Colombia.

Antonio Ponce de Leon

Antonio Ponce de Leon, PhD, Associate Professor Social Medicine Institute, Universidad do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

Sara Gabriela Pacichana-Quinayaz

Sara Gabriela Pacichana-Quinayaz, Ft, MSc, Assistant Researcher CISALVA Institute of Universidad del Valle, Cali, Colombia.

María Isabel Gutiérrez-Martínez

María Isabel Gutiérrez-Martínez, MD, MSc, PhD, CISALVA Institute Researcher & Professor School of Public Health, Universidad del Valle, Cali, Colombia.

REFERENCES

- Ajdacic-Gross, V., Bopp, M., Ring, M., Gutzwiller, F., & Rossler, W. (2010). Seasonality in suicide-a review and search of new concepts for explaining the heterogeneous phenomena. Social Science & Medicine, 71(4), 657–666. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.05.030

- Akkaya-Kalayci, T., Popow, C., Waldhör, T., & Özlü-Erkilic, Z. (2015). Impact of religious feast days on youth suicide attempts in Istanbul, Turkey. Neuropsychiatrie: Klinik, Diagnostik, Therapie und Rehabilitation: Organ der Gesellschaft Osterreichischer Nervenarzte und Psychiater, 29(3), 120–124. doi:10.1007/s40211-015-0147-9

- Arendt, F., & Scherr, S. (2017). Optimizing online suicide prevention: A search engine-based tailored approach. Health Communication, 32(11), 1403–1408. doi:10.1080/10410236.2016.1224451

- Baird, A., While, D., Flynn, S., Ibrahim, S., Kapur, N., Appleby, L., & Shaw, J. (2019). Do homicide rates increase during weekends and national holidays? The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, 30(3), 367–380. doi:10.1080/14789949.2019.1600711

- Bando, D. H., Scrivani, H., Morettin, P. A., & Teng, C. T. (2009). Seasonality of suicide in the city of Sao Paulo, Brazil, 1979–2003. Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria, 31(2), 101–105. doi:10.1590/S1516-44462009000200004

- Beauchamp, G. A., Ho, M. L., & Yin, S. (2014). Variation in suicide occurrence by day and during major American holidays. The Journal of Emergency Medicine, 46(6), 776–781. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2013.09.023

- Benedito-Silva, A. A., Nogueira Pires, M. L., & Calil, H. M. (2007). Seasonal variation of suicide in Brazil. Chronobiology International, 24(4), 727–737. doi:10.1080/07420520701535795

- Bernal, J. L., Cummins, S., & Gasparrini, A. (2017). Interrupted time series regression for the evaluation of public health interventions: A tutorial. International Journal of Epidemiology, 46(1), 348–355. doi:10.1093/ije/dyw098

- Bhaskaran, K., Gasparrini, A., Hajat, S., Smeeth, L., & Armstrong, B. (2013). Time series regression studies in environmental epidemiology. International Journal of Epidemiology, 42(4), 1187–1195. doi:10.1093/ije/dyt092

- Boenisch, S., Bramesfeld, A., Mergl, R., Havers, I., Althaus, D., Lehfeld, H., … Hegerl, U. (2010). The role of alcohol use disorder and alcohol consumption in suicide attempts – A secondary analysis of 1921 suicide attempts. European Psychiatry, 25(7), 414–420. doi:10.1016/j.eurpsy.2009.11.007

- Burbano Valencia, E. J., & Zafra Sanz, M. I. (2016). Homicide and land prices: A spatial analysis in Santiago de Cali. Cuadernos de Economía, 40(113), 1. doi:10.1016/j.cesjef.2016.06.001

- Butke, P., & Sheridan, S. C. (2010). An analysis of the relationship between weather and aggressive crime in Cleveland, Ohio. Weather, Climate, and Society, 2(2), 127–139. doi:10.1175/2010WCAS1043.1

- Carleton, T. A. (2017). Crop-damaging temperatures increase suicide rates in India. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 114(33), 8746–8751. doi:10.1073/pnas.1701354114

- Casey, P., Gemmell, I., Hiroeh, U., & Fulwood, C. (2012). Seasonal and socio-demographic predictors of suicide in Ireland: A 22 year study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 136(3), 862–867. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2011.09.020

- Ceccato, V. (2005). Homicide in São Paulo, Brazil: Assessing spatial-temporal and weather variations. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 25(3), 307–321. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2005.07.002

- Christodoulou, C., Douzenis, A., Papadopoulos, F. C., Papadopoulou, A., Bouras, G., Gournellis, R., & Lykouras, L. (2012). Suicide and seasonality. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 125(2), 127–146. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2011.01750.x

- Cohen, L. E., & Felson, M. (1979). Social change and crime rate trends: A routine activity approach. American Sociological Review, 44(4), 588–608. doi:10.2307/2094589

- Cohn, E. G., & Rotton, J. (2000). Weather, seasonal trends and property crimes in Minneapolis, 1987–1988. A moderator-variable time-series analysis of routine activities. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 20(3), 257–272. doi:10.1006/jevp.1999.0157

- Cohn, E. G., & Rotton, J. (2003). Even criminals take a holiday: Instrumental and expressive crimes on major and minor holidays. Journal of Criminal Justice, 31(4), 351–360. doi:10.1016/S0047-2352(03)00029-1

- Concha-Eastman, A., Espitia, V. E., Espinosa, R., & Guerrero, R. (2002). La epidemiología de los homicidios en Cali, 1993–1998: Seis años de un modelo poblacional. Revista panamericana de salud publica = Pan American Journal of Public Health, 12(4), 230–239.

- Congreso de la República de Colombia. (1983). Ley 51/1983 “por la cual se traslada el descanso remunerado de algunos días festivos” Retrieved from https://www.funcionpublica.gov.co/eva/gestornormativo/norma_pdf.php?i=4954.

- Demetriades, D., Kimbrell, B., Salim, A., Velmahos, G., Rhee, P., Preston, C., … Chan, L. (2005). Trauma deaths in a mature urban trauma system: Is “trimodal” distribution a valid concept? Journal of the American College of Surgeons, 201(3), 343–348. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2005.05.003

- Dixon, P. G., & Kalkstein, A. J. (2018). Where are weather-suicide associations valid? An examination of nine US counties with varying seasonality. International Journal of Biometeorology, 62(5), 685–697. doi:10.1007/s00484-016-1265-1

- Fandiño-Losada, A. (2018). Letter to the Editor about Pereira, Andresen & Mota (2016) “A temporal and spatial analysis of homicides”. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 59, 111–112. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2018.08.001

- Fandiño-Losada, A., Guerrero-Velasco, R., Mena-Muñoz, J. H., & Gutiérrez-Martínez, M. I. (2017). Efecto del control del crimen organizado sobre la violencia homicida en Cali (Colombia). Revista CIDOB D’Afers Internacionals, (116), 159–178. doi:10.24241/rcai.2017.116.2.159

- Fernández-Niño, J. A., Flórez-García, V. A., Astudillo-García, C. I., & Rodríguez-Villamizar, L. A. (2018). Weather and suicide: A decade analysis in the five largest capital cities of Colombia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(7), 1313. doi:10.3390/ijerph15071313

- Gabennesch, H. (1988). When promises fail: A theory of temporal fluctuations in suicide. Social Forces, 67(1), 129–145. doi:10.2307/2579103

- Gallego-Jiménez, O. L. (2012). Perfil Psicosociológico de los homicidios por las modalidades de riñas, sicariato y agresión en la ciudad de Manizales periodo 2004-2009. Virajes, 14(1), 151–168. https://revistasojs.ucaldas.edu.co/index.php/virajes/article/view/902

- Gaxiola-Robles, R., Celis de la Rosa, A. d J., Labrada-Martagón, V., Díaz-Castro, S. C., & Zenteno-Savín, T. (2013). Ambiental temperature increase. Salud Mental, 36(5), 421–427. doi:10.17711/SM.0185-3325.2013.053

- Gonçalves, R. E. M., Ponce, J., de, C., & Leyton, V. (2018). Alcohol use by suicide victims in the city of Sao Paulo, Brazil, 2011–2015. Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine, 53, 68–72. doi:10.1016/j.jflm.2017.11.006

- Guarin-Ardila, J. A., Montero-Ariza, R., Astudillo-García, C. I., & Fernández-Niño, J. A. (2020). Homicides during the Barranquilla Carnival, Colombia: A 10 year time-series analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(1), 35. doi:10.3390/ijerph17010035

- Guerrero, R., & Fandiño-Losada, A. (2017). Is Colombia a violent country? Colomb Med, 48(1), 9–11. doi:10.25100/cm.v48i1.2979

- He, N., Cao, L., Wells, W., & Maguire, E. R. (2003). Forces of production and direction: A test of an expanded model of suicide and homicide. Homicide Studies, 7(1), 36–57. doi:10.1177/1088767902239242

- Instituto Nacional de Medicina Legal y Ciencias Forenses (2016). Informe Forensis: Datos para la vida. Instituto Nacional de Medicina Legal y Ciencias Forenses. Colombia. Retrieved from https://www.medicinalegal.gov.co/documents/20143/49526/Forensis+2016.+Datos+para+la+vida.pdf.

- Jessen, G., & Jensen, B. (1999). Postponed suicide death? Suicides around birthdays and major public holidays. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior, 29(3), 272–283. doi: 10.1111/j.1943-278X.1999.tb00302.x

- Kelly, I. W., Rotton, J., & Culver, R. (1986). The moon was full and nothing happened | Skeptical inquirer. Skeptical Inquirer, 10(2), 129–143.

- Kim, E., Cho, S. E., Na, K. S., Jung, H. Y., Lee, K. J., Cho, S. J., & Han, D. G. (2019). Blue Monday is real for suicide: A case-control study of 188,601 suicides Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior, 49(2), 393–400. doi:10.1111/sltb.12429

- Kmetty, Z., Tomasovszky, Á., & Bozsonyi, K. (2018). Moon/sun – suicide. Reviews on Environmental Health, 33(2), 213–217. doi:10.1515/reveh-2017-0039

- Krug, E. G., Mercy, J. A., Dahlberg, L. L., & Zwi, A. B. (2002). The world report on violence and health. The Lancet, 360(9339), 1083–1088. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11133-0

- Lester, D. (1987). Suicide and homicide at Easter. Psychological Reports, 61(1), 224. doi:10.2466/pr0.1987.61.1.224

- Lowry, C., Lightman, S., & Nutt, D. (2009). That warm fuzzy feeling: Brain serotonergic neurons and the regulation of emotion. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 23(4), 392–400. doi:10.1177/0269881108099956

- Mäkelä, P., Martikainen, P., & Nihtilä, E. (2005). Temporal variation in deaths related to alcohol intoxication and drinking. International Journal of Epidemiology, 34(4), 765–771. doi:10.1093/ije/dyi025

- Mathew, V., Lindesay, J., Shanmuganathan, N., & Eapen, V. (1991). Attempted suicide and the lunar cycle. Psychological Reports, 68(3 Pt 1), 927–930. doi:10.2466/PR0.68.3.927-930

- Moreno Montoya, J., & Sánchez Pedraza, R. (2009). Muertes por causas violentas y ciclo económico en Bogotá, Colombia: un estudio de series de tiempo, 1997–2006. Retrieved from http://www.scielosp.org/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1020-49892009000700004.

- Nordt, C., Warnke, I., Seifritz, E., & Kawohl, W. (2015). Modelling suicide and unemployment: A longitudinal analysis covering 63 countries, 2000–11. The Lancet. Psychiatry, 2(3), 239–245. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(14)00118-7

- Parker, G., Gao, F., & Machin, D. (2001). Seasonality of suicide in Singapore: Data from the equator. Psychological Medicine, 31(3), 549–553. doi:10.1017/S0033291701003294

- Partonen, T., Haukka, J., Nevanlinna, H., & Lönnqvist, J. (2004). Analysis of the seasonal pattern in suicide. Journal of Affective Disorders, 81(2), 133–139. doi:10.1016/S0165-0327(03)00137-X

- Pereira, D. V. S., Andresen, M. A., & Mota, C. M. M. (2016). A temporal and spatial analysis of homicides. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 46(Supplement C), 116–124. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2016.04.006

- Ploderl, M., Fartacek, C., Kunrath, S., Pichler, E.-M., Fartacek, R., Datz, C., & Niederseer, D. (2015). Nothing like Christmas-suicides during Christmas and other holidays in Austria. European Journal of Public Health, 25(3), 410–413. doi:10.1093/eurpub/cku169

- Pokorny, A. D. (1964). Moon phases, suicide, and HOMOCIDE. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 121(1), 66–67. doi:10.1176/ajp.121.1.66

- Poveda, A. C. (2012). Violence and economic development in Colombian cities: A dynamic panel data analysis. En Serie de Documentos en Economía y Violencia (No 010080; Serie de Documentos En Economía y Violencia). Centro de Investigaciones en Violencia, Instituciones y Desarrollo Económico (VIDE). Retrieved from https://ideas.repec.org/p/col/000137/010080.html.

- Preti, A., & Miotto, P. (1998). Seasonality in suicides: The influence of suicide method, gender and age on suicide distribution in Italy. Psychiatry Research, 81(2), 219–231. doi:10.1016/s0165-1781(98)00099-7

- Rock, D. J., Judd, K., & Hallmayer, J. F. (2008). The seasonal relationship between assault and homicide in England and Wales. Injury, 39(9), 1047–1053. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2008.03.025

- Rodriguez, M. d. (2008). Variación estacional de la mortalidad por homicidio en Colombia, 1985 a 2001. Colombia Médica, 39, 154–160.

- Roy, A., Biswas, T., & Roy, A. (2017). A structured review of relation between full moon and different aspects of human health. SM Journal of Biometrics & Biostatistics, 2(1), 1–4. doi:10.36876/smjbb.1007

- Sánchez, Á. I., Villaveces, A., Krafty, R. T., Park, T., Weiss, H. B., Fabio, A., … Gutiérrez, M. I. (2011). Policies for alcohol restriction and their association with interpersonal violence: A time-series analysis of homicides in Cali, Colombia. International Journal of Epidemiology, 40(4), 1037–1046. doi:10.1093/ije/dyr051

- Sánchez Pedraza, R., Tejada Neira, P. A., & Guzmán Sabogal, Y. (2008). Muertes violentas intencionalmente producidas en Bogotá, 1997–2005: Diferencias según el sexo. Revista Colombiana de Psiquiatría, 37, 316–329. http://www.scielo.org.co/pdf/rcp/v37n3/v37n3a03.pdf.

- Sánchez, R., Orejarena, S., & Guzmán, Y. (2004). Características de los suicidas en Bogotá:1985–2000. Revista de Salud Pública, 6(3), 217–234. doi:10.1590/S0124-00642004000300001

- Sánchez-Rentería, G., Bonilla-Escobar, F. J., Fandiño-Losada, A., & Gutiérrez-Martinez, M. I. (2016). Observatorios de convivencia y seguridad ciudadana: Herramientas para la toma de decisiones y gobernabilidad. Revista Peruana de Medicina Experimental y Salud Pública, 33(2), 362–367. doi:10.17843/rpmesp.2016.332.2203

- Sandoval, L. E. (2018). Socio-economics characteristics and spatial persistence of homicides in Colombia, 2000–2010. Estudios de Economía, 45(1), 51–77. doi:10.4067/S0718-52862018000100051

- Sansone, R. A., & Sansone, L. A. (2011). The Christmas effect on psychopathology. Innovations in Clinical Neuroscience, 8(12), 10–13. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3257984/.

- Spindelegger, C., Stein, P., Wadsak, W., Fink, M., Mitterhauser, M., Moser, U., … Hahn, A. (2012). Light-dependent alteration of serotonin-1A receptor binding in cortical and subcortical limbic regions in the human brain. The World Journal of Biological Psychiatry, 13(6), 413–422. doi:10.3109/15622975.2011.630405

- StataCorp. (2015). Stata: Release 14. Statistical Software. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC.

- Villaveces, A., Cummings, P., Espitia, V. E., Koepsell, T. D., McKnight, B., & Kellermann, A. L. (2000). Effect of a ban on carrying firearms on homicide rates in 2 Colombian cities. JAMA, 283(9), 1205–1209. doi:10.1001/jama.283.9.1205

- Voracek, M., Loibl, L. M., Kapusta, N. D., Niederkrotenthaler, T., Dervic, K., & Sonneck, G. (2008). Not carried away by a moonlight shadow: No evidence for associations between suicide occurrence and lunar phase among more than 65,000 suicide cases in Austria, 1970–2006. Wiener Klinische Wochenschrift, 120(11–12), 343–349. doi:10.1007/s00508-008-0985-6

- Walker, R. L., Lester, D., & Joe, S. (2006). Lay theories of suicide: An examination of culturally relevant suicide beliefs and attributions among African Americans and European Americans. The Journal of Black Psychology, 32(3), 320–334. doi:10.1177/0095798406290467

- Yu, J., Yang, D., Kim, Y., Hashizume, M., Gasparrini, A., Armstrong, B., … Chung, Y. (2020). Seasonality of suicide: A multi-country multi-community observational study. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 29, e163. doi:10.1017/S2045796020000748

- Zonda, T., Bozsonyi, K., Veres, E., Lester, D., & Frank, M. (2009). The impact of holidays on suicide in Hungary. Omega, 58(2), 153–162. doi:10.2190/OM.58.2.e