Abstract

Objectives. To assess whether the use of cardioprotective therapies for type 2 diabetes varies by gender and whether the risk of cardiovascular events is higher in women versus men in the REWIND trial, including an international type 2 diabetes patient population with a wide range of baseline risk. Design. Gender differences in baseline characteristics, cardioprotective therapy, and the achieved clinical targets at baseline and two years were analyzed. Hazards for cardiovascular outcomes (fatal/nonfatal stroke, fatal/nonfatal myocardial infarction, cardiovascular death, all-cause mortality, and heart failure hospitalization), in women versus men were analyzed using two Cox proportional hazard models, adjusted for randomized treatment and key baseline characteristics respectively. Time-to-event analyses were performed in subgroups with or without history of cardiovascular disease using Cox proportional hazards models that included gender, subgroup, randomized treatment, and gender-by-subgroup interactions. Results. Of 9901 participants, 46.3% were women. Significantly fewer women than men had a cardiovascular disease history. Although most women met treatment targets for blood pressure (96.7%) and lipids (72.8%), fewer women than men met the target for cardioprotective therapies at baseline and after two years, particularly those with prior cardiovascular disease, who used less renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors, statins, and aspirin than men. Despite these differences, women had lower hazards than men for all outcomes except stroke. No significant gender and cardiovascular disease history interactions were identified for cardiovascular outcomes. Conclusions. In REWIND, most women met clinically relevant treatment targets, but in lower proportions than men. Women had a lower risk for all cardiovascular outcomes except stroke.

Clinical trials.gov registration number: NCT01394952

Introduction

Despite improvements in diagnosis and management, cardiovascular disease (CVD) remains the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in people with diabetes [Citation1,Citation2]. Although the results are conflicting, some meta-analyses report that diabetes is associated with greater relative risk of fatal coronary heart disease, stroke or cardiovascular death in women compared with men [Citation2–6]. The traditional view that men are at a higher risk for cardiovascular disease than women may account for this difference. It may also result in the use of fewer cardioprotective therapies in women, including lipid-lowering and antiplatelet drugs [Citation2,Citation7]. Possible reasons for this gender disparity are unclear, growing evidence suggests that type 2 diabetes adversely affects metabolic and cardiovascular risk factor profiles to a greater extent in women than men. For example, women with diabetes are more likely to have obesity, hypercholesterolemia, hypertension [Citation2], and a more rapid rise in blood pressure levels than men [Citation8]. Moreover, vascular disease is expressed differently, with men more likely to develop occlusive coronary artery disease, and women more likely to develop nonobstructive coronary artery disease or microvascular dysfunction [Citation9].

The REWIND (Researching cardiovascular Events with a Weekly INcretin in Diabetes) trial was an international cardiovascular outcome trial (CVOT) that enrolled participants older than 50 years with type 2 diabetes and at a wide range of baseline cardiovascular risk [Citation10]. The trial recruited a larger proportion of women (46.3%) than any other completed CVOT in type 2 diabetes population. The aim of this exploratory analysis is to investigate gender differences in baseline characteristics, within trial use of cardioprotective therapies, and observed cardiovascular outcomes in an international type 2 diabetes patient population with a wide range of baseline cardiovascular risk.

Methods

REWIND study design and participants

The REWIND study (NCT01394952) design and primary results have been previously described [Citation10,Citation11]. In brief, REWIND was a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled CVOT conducted in 9901 participants with type 2 diabetes (glycated hemoglobin A1c [HbA1c] of ≤9.5% [80 mmol/mol]) and either a previous cardiovascular event or risk factors, who were randomized to receive weekly injections of 1.5 mg dulaglutide or matching placebo. Key inclusion and exclusion criteria are presented in Table S1. Investigators were advised to promote a healthy lifestyle and to manage glucose concentrations according to local guidelines and were free to add any glucose lowering drug apart from another GLP-1 receptor agonist or pramlintide. Management of blood pressure, lipids, other cardiovascular risk factors, and medical conditions was at the discretion of either the study investigator or the patient’s usual physician(s) as informed by current country guidelines.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of REWIND participants.

The primary outcome was the first occurrence of any component of the composite three-point major adverse cardiovascular event (MACE-3) outcome comprising cardiovascular death, nonfatal myocardial infarction including those which were silent, nonfatal stroke, and heart failure requiring hospitalization. The trial was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences International Ethical Guidelines, the International Conference on Harmonization Good Clinical Practices Guideline, and all other applicable laws and regulations. The trial protocol was approved by local research ethics boards, and all participants provided written informed consent.

Statistical analysis

This post hoc analysis assessed gender differences of women versus men using the intention-to-treat (ITT) population of REWIND, which is identical to the study previously reported cohort. Baseline characteristics including demographics, known cardiovascular risk factors, and use of cardioprotective medications were compared between the genders and by baseline cardiovascular status (with or without history of cardiovascular disease, defined as myocardial infarction, ischemic stroke, unstable angina with electrocardiogram changes, myocardial infarction on imaging or stress test, or coronary, carotid, or peripheral revascularization). The relationship between those characteristics and incident cardiovascular disease was explored. Only those classes of cardiovascular medications that were used by at least 5% of REWIND participants at baseline were analyzed by class including angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs), beta-blockers, diuretics, aldosterone antagonists, calcium channel blockers, aspirin, and statins. Continuous variables were compared using two sample t-tests, and categorical variables were compared using Pearson’s Chi-squared tests if the expected counts were greater than or equal to 5 in at least 80% of the cell otherwise Fisher’s exact test were performed. Variables that were not normally distributed were analyzed using Wilcoxon Rank-Sum test.

The full ITT population was used to determine incidence rates. Absolute risk differences between genders were computed for MACE-3, fatal or nonfatal stroke, fatal or nonfatal myocardial infarction, cardiovascular death, all-cause mortality, and heart failure requiring hospitalization. Incidence rates were calculated as number of participants developing the outcome divided by the person-years of follow-up. The hazard of the MACE-3 outcome, each of its three components, all-cause mortality, and heart failure hospitalization in women versus men was analyzed using two Cox proportional hazard models. The first was adjusted for randomized treatment in addition to gender. The second was adjusted for randomized treatment and key baseline characteristics (Table S2) in addition to gender. These characteristics were identified using stepwise variable selection in a Cox proportional hazards model with all baseline characteristics as candidate variables, using a significance level of p = .05. The bidirectional stepwise variable selection combined both forward and backward selection and assessed the significance of the effect of the variables at each step. Details of this procedure can be found in the SAS Documentation [Citation12].

A subset of the ITT population, which excluded patients with missing data at baseline or at two years for HbA1c, systolic blood pressure, low-density lipoprotein (LDL)-cholesterol, and concomitant medications or baseline history of cardiovascular disease either missing or unknown, was used for all other analyses. Analyses were performed to investigate changes from baseline to two years in the use of cardioprotective therapies and achievement of relevant clinical targets by gender. The two-year time point was chosen, as it was the first post-randomization visit at which all cardiovascular risk factors were measured. The therapies defined as relevant for this comparison included BP-lowering, lipid-lowering, and antiplatelet medications. Glucose-lowering agents were not included because none were known to be cardioprotective at the time of the conduct of REWIND. The relevant targets measured were (a) use of ACE inhibitors or ARBs, (b) use of any other antihypertensive drug or systolic blood pressure <130 mmHg, (c) use of statins or LDL <2.6 mmol/L, (d) use of aspirin, and (e) a composite comprised of at least two of the above.

A time-to-event analysis was performed in the subgroups of patients with and without a history of cardiovascular disease using a Cox proportional hazards regression where the model includes gender, baseline cardiovascular disease subgroup, randomized treatment, and gender by subgroup interaction. The interaction p values between the gender and the subgroups were reported and used for interpretation, using a significance level p < .05. Data were analyzed using the SAS software (Version 9.4).

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The REWIND trial was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences International Ethical Guidelines, the International Conference on Harmonization Good Clinical Practices Guideline, and all other applicable laws and regulations. The trial protocol was approved by local research ethics boards, and all participants provided written informed consent.

Results

Gender differences in baseline clinical characteristics

Of 9901 study participants, 4589 (46.3%) were women. As revealed by several baseline characteristics differed between the genders (). Fewer women than men had a history of cardiovascular disease and met clinically relevant treatment targets for all treatments except use of anti-hypertensive medication or systolic blood pressure <130 mmHg.

Gender differences in CV risk factor management

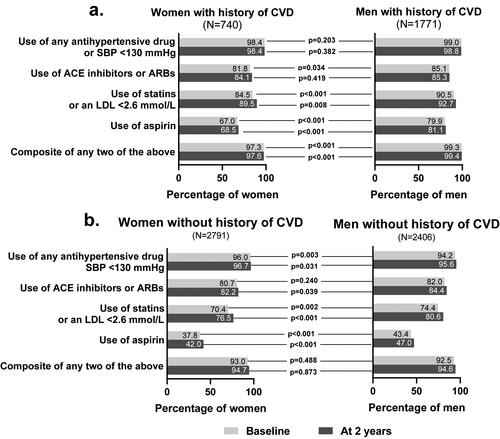

Patients with a history of cardiovascular disease

Of 2511 participants with a history of cardiovascular disease and without missing data for HbA1c, systolic blood pressure, LDL-cholesterol, and concomitant medications, similar proportions of women and men (98.4% vs. 99.0%) were using antihypertensive medications at both baseline and after two years of follow-up (). Conversely, fewer women than men used ACE inhibitors or ARBs, statins, or aspirin (). After two years of follow-up, the proportion of study participants meeting the recommended treatment and risk factor targets was largely unchanged and the differences between genders remained similar for most clinically relevant targets. Women with a history of cardiovascular disease showed increased use of ACE inhibitors or ARBs and statins at two years.

Figure 1. Percentage of patients meeting relevant clinical targets at baseline and at two years in (a) patients with history of cardiovascular disease at baseline, and (b) patients without history of cardiovascular disease at baseline. This subgroup analysis includes a subset of intention-to-treat (ITT) population excluding patients with missing data at baseline or two years for HbA1c, systolic blood pressure, LDL-cholesterol, and concomitant medications or baseline history of CVD either missing or unknown. Abbreviations: ACE: angiotensin-converting enzyme; ARBs: angiotensin-receptor blockers; CVD: cardiovascular disease; HbA1c: glycated hemoglobin A1c; LDL: low-density lipoprotein; N: total number of participants in each gender group; SBP: systolic blood pressure.

Patients without a history of CVD

In this subpopulation, significantly more women were using antihypertensive medications than men, although the absolute difference was small (). At baseline, the use of ACE inhibitors or ARBs was similar between women and men, but at two years of follow-up, significantly fewer women used them than men. At baseline, significantly fewer women than men used statins and aspirin. After two years of follow-up, both women and men reported an increase in use of statins ().

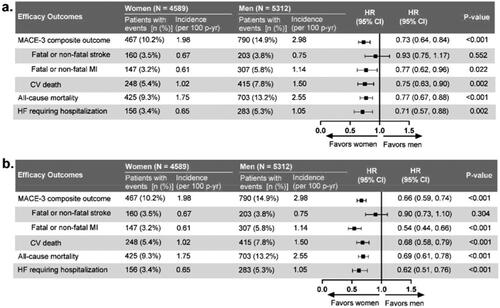

Regardless of the extent of model adjustment, women had a lower risk than men for MACE-3, all-cause mortality, heart failure requiring hospitalization and the individual MACE-3 components except for fatal or non-fatal stroke (using fully adjusted model for gender, randomized treatment, and baseline characteristics: hazard ratio [HR]) 0.93, 95% confidence interval [CI]) 0.75–1.17; p = .552; using minimally adjusted model for gender and randomized treatment: HR 0.90, 95% CI 0.73–1.10; p = .304; ). There were no significant interactions identified between gender and baseline cardiovascular disease status for any of the outcomes measured except for a lower all-cause mortality among women (quantitative interaction p = .035; Table S3). There were no significant interactions between gender and the recommended treatment and risk factor targets at baseline for any cardiovascular outcome with the exceptions of use of aspirin and cardiovascular death (quantitative interaction p = .020; Table S3) and the composite of any two treatments and stroke where women meeting the composite of two treatments have lower risk for stroke and women not meeting the composite have higher risk (qualitative interaction p = .049).

Figure 2. Gender differences in major cardiovascular event (MACE) outcome. (a) Model adjusted for gender, randomized treatment, and selected baseline characteristics. (b) Model adjusted for gender and randomized treatment. This analysis was performed on the full ITT population. Baseline characteristics selected for adjustment for each outcome in are listed in Table S4. Abbreviations: CI: confidence interval; CV: cardiovascular; HF: heart failure; HR: hazard ratio; ITT: intention-to-treat; MACE: major adverse cardiovascular events; MI: myocardial infarction n: number of patients in each category; N: total number of participants in each gender group; p-yr: patient-year.

After adjusting for gender and treatment, the strongest statistically significant predictors for stroke were the baseline systolic blood pressure, a history of stroke or transient ischemic attack, and atrial fibrillation (Table S4). Importantly, aspirin use, which was less frequent in women, did not emerge as a significant predictor for stroke.

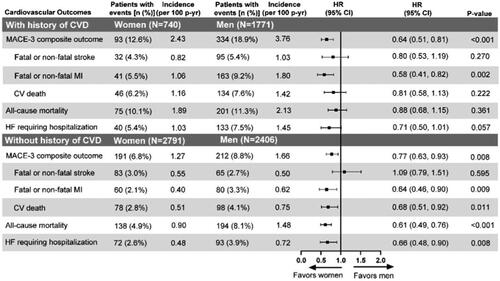

Different patterns of cardiovascular outcomes for women were apparent in both subgroups (with or without a history of cardiovascular disease; ). Women with prior cardiovascular disease had a MACE-3 event rate approximately twice as high as women without prior cardiovascular disease (2.43 vs. 1.27 events per 100 patient-years), which was lower than that of men with prior cardiovascular disease (2.43 vs. 3.76 events per 100 patient-years). The hazard of cardiovascular death (HR 0.81, 95% CI 0.58–1.13; p = .222), all-cause mortality (HR 0.88, 95% CI 0.68–1.15; p = .361), and heart failure requiring hospitalization (HR 0.71, 95% CI 0.50, 1.01; p = .057) did not differ between women and men with prior cardiovascular disease.

Figure 3. Time-to-event analysis of the cardiovascular risk outcomes with gender comparison. This subgroup analysis includes a subset of ITT population excluding patients with missing data at baseline or two years for HbA1c, SBP, LDL-cholesterol, and concomitant medications or baseline history of CVD either missing or unknown. Abbreviations: CI: confidence interval; CV: cardiovascular; CVD: cardiovascular disease; HbA1c: glycated hemoglobin A1c; HF: heart failure; HR: hazard ratio; ITT: intention-to-treat; LDL: low-density lipoproteins; n: number of patients in each category; N: total number of participants in each gender group; MACE: major cardiovascular events; MI: myocardial infarction; p-yr: patient year; SBP: systolic blood pressure.

Discussion

This post hoc analysis showed the expected gender-related pattern of baseline risk, with women less likely to have a history of cardiovascular disease and a baseline cardiovascular risk profile characterized by a clinically similar systolic blood pressure, higher high-density lipoprotein, and higher LDL compared with men. Most participants of both genders met clinically relevant risk factor targets and treatment recommendations for the use of ACE inhibitors or ARBs and statins or LDL <2.6 mmol/L, but women were less likely to meet the targets than men. During follow-up, women were less likely to experience all measured cardiovascular outcomes except stroke.

Other observational studies have reported gender disparities in cardiovascular risk management, indicating that women with diabetes have less well-controlled HbA1c, LDL-cholesterol, and blood pressure compared with men [Citation2,Citation13–15]. The REWIND trial design did not prescribe a specific cardiovascular risk management, but the investigators were asked to ensure that enrolled patients were receiving treatment according to local management guidelines [Citation16–19]. In REWIND, although gender disparities did exist, the absolute differences were generally small, with most women reaching clinically relevant targets for the use of antihypertensive drugs, ACE inhibitors/ARBs, and statins. The proportion of women prescribed recommended treatment increased during the two years of follow-up, reaching parity with men in the cohort with a history of cardiovascular disease for ACE inhibitor or ARB use, but with remaining deficits in the use of statin, aspirin, or achieving a composite of any two targets compared with men. These findings are directionally aligned with data from other CVOTs reporting gender disparities in cardiovascular risk management, including data from the Trial Evaluating Cardiovascular Outcomes with Sitagliptin (TECOS) [Citation20], showing a low percentage of women using cardiovascular protective medications such as ACE inhibitors (49% vs. 55%), statins (73% vs. 83%), and aspirin (72% vs. 81%), and data from a systematic review and meta-analysis [Citation21] of five CVOTs in diabetes showing that fewer women used statins, beta-blockers or aspirin.

Women in REWIND had a lower risk for MACE outcomes and all-cause mortality but a similar risk for stroke compared to men. Additional investigation attempting to identify any gender-specific predictors for stroke only revealed typical risk factors such as history of stroke or transient ischemic attack, higher baseline systolic blood pressure, or a history of atrial fibrillation. Presumably, other unmeasured biological factors such as body composition, fat distribution, or sex hormones may play a role [Citation22]. Our results are in accordance with those of a meta-analysis of 64 population-based cohort studies [Citation23] indicating that the excess risk of stroke associated with diabetes is significantly higher in women than in men, independent of gender differences in other major cardiovascular risk factors. It is also possible that our findings may be because history of stroke is simply underrepresented among the men in REWIND. Further studies, in line with recommendations from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association [Citation24], may shed light on this issue.

As was seen in the overall population, women without a history of CVD had a reduced risk of death compared with men, whether from cardiovascular causes or from any cause, while among participants with a history of cardiovascular disease the overall risk for death was similar. In fact, the lack of evidence for a significant interaction in the outcome analysis between gender and history of cardiovascular disease suggests that the impact of the latter on the risk for a future event is about the same for women and men (except for the significant interaction in all-cause mortality, a finding that is unlikely to be clinically meaningful). An attenuation of the prognostic advantage of women was also demonstrated in a US-based cohort (n = 339,890) hospitalized for MI between 2015 and 2016 [Citation25]. Peters et al. documented reduced risk for women compared with men for several cardiovascular outcomes including myocardial infarction, heart failure, and all-cause mortality, but underlined that the risk for subsequent events after a myocardial infarction was similar. These authors hypothesized that gender differences in time to diagnosis, use of acute coronary procedures, use of guideline-recommended treatments, or in pathophysiology of disease may all be contributing factors. In REWIND, gender differences in baseline characteristics or in the use of evidence-based medications within the cardiovascular risk groups seem too small to explain the cardiovascular outcomes discrepancy. The achievement over time of relevant treatment and risk factor targets represents a relatively small increment in a population with the majority already at target and is probably not a significant effect modifier, and the few statistically significant interactions, in an analysis uncontrolled for multiple testing, might be cautiously interpreted as spurious findings. Differences in underlying cardiovascular conditions known to differ by gender, including higher incidence of nonobstructive cardiovascular disease or heart failure with preserved ejection fraction [Citation9], cannot be excluded.

Strengths of the REWIND study include long median follow-up of 5.4 years, a patient population representative of a wide range of baseline cardiovascular risk from risk factors only to established cardiovascular disease, and as mentioned, the largest cohort of women enrolled among the CVOTs completed to date. The REWIND population was broadly well controlled for cardiovascular risk factors with relatively little change in risk factor management during trial follow-up. However, factors not possible to account for are a discrepant selection process for men and women when recruiting study participants, a possible diverse application of local guidelines in a heterogeneous population both at baseline and during follow-up, and the impact of cardiovascular events on care during the follow-up period. It is also possible that risk factor management in a clinical trial, enrolling high-risk patients with the specific purpose of robustly measuring cardiovascular outcomes, may overestimate the use of cardioprotective medications compared to daily clinical practice. This may also be the reason that most participants met guideline-recommended risk factor targets.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this observational post hoc analysis of a large trial population with type 2 diabetes revealed that although most participants of both genders met relevant treatment targets, women were less likely than men to do so and remained at lower risk than men for all cardiovascular outcomes apart from stroke, an observation in need of further studies. Meanwhile, the fact that gender differences in management of cardiovascular risk is noted even in a strict trial setting should raise the awareness of clinicians of potential inequalities in daily practice which may lead to women losing their advantage in terms of cardiovascular prognosis. A comprehensive cardiovascular risk assessment and target-driven management should be implemented in all patients with diabetes in the same way, regardless of gender, without the preconception that women are “naturally protected” from cardiovascular events.

Author contributions

G.F., J.M.M., L.R., and M.A.B, reviewed the literature and interpreted the data. S.R. P.R-M., and R.K. did or confirmed the statistical analyses and interpreted the data. C.A., L.S., and H.C.G. (REWIND Chair) interpreted the data. All authors critically reviewed and revised the draft and approved the report before submission. All authors agreed to be accountable for accuracy, integrity, and other aspects of the work.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (41.8 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the REWIND study participants, the investigators, and study coordinators who cared for them. The authors thank Dr. Shirin Ghodke (Eli Lilly Services India Limited, Bangalore, India) for medical writing assistance.

Disclosure statement

This study was funded by Eli Lilly and Company. G.F., P.R-M., and R.K. report no conflicts of interest relevant to this article. L.R. reports grants from the Swedish Heart Lung Foundation, Region Stockholm, and Boehringer Ingelheim, fees for consulting, travel, and clinical research grant from Eli Lilly and Company, and fees for consulting and speaking from Boehringer Ingelheim, Novo Nordisk, Merck, and Bayer. H.C.G. holds the McMaster-Sanofi Population Health Institute Chair in Diabetes Research and Care. He reports research grants from Eli Lilly and Company, AstraZeneca, Merck, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi; honoraria for speaking from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly and Company, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi; and consulting fees from Abbott, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly and Company, Merck, Novo Nordisk, Janssen, Sanofi, Kowa. S.R. is an employee of Eli Lilly and Company. J.M.M., L.S., and M.A.B. are employees and stockholders of Eli Lilly and Company. C. A. was an employee of Eli Lilly and Company. No other potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings will be disclosed only upon request and approval of the proposed use of the data by a review committee. All the data for the present report came from the Population Health Institute (PHRI) in Hamilton, Canada, who also did all the data analysis for the REWIND trial. The REWIND data sharing policy is described in the Supplemental Material.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Nichols M, Townsend N, Scarborough P, et al. Cardiovascular disease in Europe 2014: epidemiological update. Eur Heart J. 2014;35(42):2950–2959.

- Wright AK, Kontopantelis E, Emsley R, et al. Cardiovascular risk and risk factor management in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Circulation. 2019;139(24):2742–2753.

- Peters SA, Huxley RR, Woodward M. Diabetes as risk factor for incident coronary heart disease in women compared with men: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 64 cohorts including 858,507 individuals and 28,203 coronary events. Diabetologia. 2014;57(8):1542–1551.

- Huxley R, Barzi F, Woodward M. Excess risk of fatal coronary heart disease associated with diabetes in men and women: meta-analysis of 37 prospective cohort studies. BMJ. 2006;332(7533):73–78.

- Prospective Studies Collaboration and Asia Pacific Cohort Studies Collaboration. Sex-specific relevance of diabetes to occlusive vascular and other mortality: a collaborative meta-analysis of individual data from 980 793 adults from 68 prospective studies. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018;6:538–546.

- Cangemi R, Romiti GF, Campolongo G, et al. Gender related differences in treatment and response to statins in primary and secondary cardiovascular prevention: the never-ending debate. Pharmacol Res. 2017;117:148–155.

- Kulenovic I, Mortensen MB, Bertelsen J, et al. Statin use prior to first myocardial infarction in contemporary patients: inefficient and not gender equitable. Prev Med. 2016;83:63–69.

- Ji H, Kim A, Ebinger JE, et al. S. Sex differences in blood pressure trajectories over the life course. JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5(3):19–26.

- Regitz-Zagrosek V, Kararigas G. Mechanistic pathways of sex differences in cardiovascular disease. Physiol Rev. 2017;97(1):1–37.

- Gerstein HC, Colhoun HM, Dagenais GR, et al. Dulaglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes (REWIND): a double-blind, randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2019;394(10193):121–130.

- Gerstein HC, Colhoun HM, Dagenais GR, et al. Design and baseline characteristics of participants in the researching cardiovascular events with a weekly INcretin in diabetes (REWIND) trial on the cardiovascular effects of dulaglutide. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2018;20(1):42–49.

- SAS®/STAT user’s guide: high performance procedures; 2018 [accessed 2021 Feb 15]. Available from: https://documentation.sas.com/?cdcId=pgmsascdc&cdcVersion=9.4_3.4&docsetId=stathpug&docsetTarget=stathpug_introcom_stat_sect032.htm&locale=en

- Hambraeus K, Tydén P, Lindahl B. Time trends and gender differences in prevention guideline adherence and outcome after myocardial infarction: data from the SWEDEHEART registry. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2016;23(4):340–348.

- Gouni-Berthold I, Berthold HK, Mantzoros CS, et al. Sex disparities in the treatment and control of cardiovascular risk factors in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(7):1389–1391.

- Sekerija M, Poljicanin T, Erjavec K, et al. Gender differences in the control of cardiovascular risk factors in patients with type 2 diabetes -a cross-sectional study. Intern Med. 2012;51(2):161–166.

- 9. Cardiovascular disease and risk management: standards of medical care in diabetes-2018. Diabetes Care. 2018;41:s86–s104.

- Davies MJ, D’Alessio DA, Fradkin J, et al. A consensus report by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care. 2018;41(12):2669–2701.

- Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL Jr, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA guideline on the management of blood cholesterol: executive summary. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73(24):3168–3209.

- Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(19):2273–2275.

- Bethel MA, Green JB, Milton J, et al. Age and sex differences in baseline characteristics of patients enrolled in the trial evaluating cardiovascular outcomes with sitagliptin (TECOS). Diabetes Obes Metab. 2015;17(4):395–402.

- Clemens KK, Woodward M, Neal B, et al. Sex disparities in cardiovascular outcome trials of populations with diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(5):1157–1163.

- Peters SAE, Woodward M. Sex differences in the burden and complications of diabetes. Curr Diab Rep. 2018;18(6):33.

- Peters SA, Huxley RR, Woodward M. Diabetes as a risk factor for stroke in women compared with men: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 64 cohorts, including 775,385 individuals and 12,539 strokes. Lancet. 2014;383(9933):1973–1980.

- Bushnell C, McCullough LD, Awad IA, et al. Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in women: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2014;45(5):1545–1588.

- Peters SAE, Colantonio LD, Chen L, et al. Sex differences in incident and recurrent coronary events and all-cause mortality. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76(15):1751–1760.