ABSTRACT

Circle dance, which derives from the tradition of folk dances, is practised worldwide. This article explores the meanings participants attribute to it. In-depth interviews with 39 participants, teachers and coordinators of teacher training programmes from the circle dance network in the United Kingdom were undertaken. Applying a constructivist grounded theory approach, major categories, representing respectively the experiences of circle dance participants, teachers and coordinators, were developed. This article specifically focuses on the first major category, termed “I can't imagine life without it”, which relates to the experience of 22 dancers. From an occupational perspective, the study reveals how participants realise a sense of meaning and satisfaction through engagement in circle dance and the potential contribution of this occupation to well-being.

圆圈舞派生自民间舞蹈传统,现在风靡全球。本文探讨对于参与者而言它的意义所在。对来自英国圆圈舞群体的39名学员、教师和网络教师培训计划组织者进行了深入采访。应用建构基础理论法,建立了圆圈舞学员、教师和组织者这几个大类。本文集中讨论第一大类,这一类被称为“我不能想象生活中没有它”,涉及到22个舞者的经历。从休闲角度来看,研究揭示了参与者如何通过参加跳圆圈舞而产生一种意义感和满足感, 也揭示了这种休闲活动对人们福祉的潜在作用。

Understanding how occupations are organised, the skills necessary to undertake various occupations, and how people realise a sense of meaning through occupation is fundamental to advancing an occupational perspective. Investigating specific occupations, taking into consideration their different social and cultural contexts, can contribute to knowledge of the importance of meaningful occupation in the lives of all people (Hocking, Citation2000, Citation2009; Wilcock & Hocking, Citation2015; Yerxa et al., Citation1990). Such understandings are crucial to improving individuals’ quality of life and realising their potential (Creek, Citation2003) because engaging in meaningful and fulfilling occupations leads to feelings of well-being and positively impacts self-esteem, motivation and socialization (Wilcock & Hocking, Citation2015).

This qualitative study offers an in-depth exploration of a specific occupation; circle dance. The research was part of a larger doctoral study to understand the occupational experience of people who engage in circle dance, outside the context of the health care system. The article explores the meanings that participants attribute to circle dance, where “meaning” is defined as the intent, significance, and importance something has for an individual (Oxford dictionary, Citation2015). The discussion begins with an overview of literature related to the meaning occupations, particularly leisure occupations, hold for the general population. Those meanings are experienced and do not “exist outside the perception of the person within whom it abides” (Hasselkus, Citation2011, p. 2). Relevant aspects of circle dance, including the structure of circle dances, the establishment of the circle dance movement and its network, and the available literature are then discussed.

The meaning of occupation

The concept of meaningful occupation has been explored by many scholars (Hammell, Citation2009; Hasselkus, Citation2011; Pemberton & Cox, Citation2013; Wilcock, Citation1998, Citation1999; Wilcock & Hocking, Citation2015). Hasselkus (Citation2011) proposed that “occupation is a powerful source of meaning in our lives, meaning arises from occupation and occupation arises from meaning” (p. 21). Wilcock (Citation1998) made an important theoretical contribution by proposing a definition of occupation based specifically upon meaning “as a synthesis of doing, being, and becoming” (p. 249). Doing refers to the occupational performance, including the individual's competency to perform occupations that they want, need or are expected to do. Being is captured within the process of doing or the individual's occupational experience and how people find meaning in what they do. Becoming is related to “the notions of potential and growth, of transformation and self-actualisation” (p. 251). A later added concept, belonging, suggests that occupations provide opportunities for developing and maintaining connections with others, and the social context in which occupation is performed (Wilcock, Citation2007). Expanding the role of occupation beyond therapeutic tools, Wilcock (Citation1999) asserted that these components are integral to the health and well-being of all people. Linking these ideas together, Hasselkus (Citation2011) proposed that “being” and “becoming” can be strongly linked with the notion of meaning of occupation, which is an essential aspect of understanding health and well-being. Taken together, these understandings suggest the value of considering the meaning of a variety of occupations related to everyday life (including leisure), and of realising both their transformative potential and contribution to individuals’ sense of well-being (Wilcock, Citation1998).

Amongst the scholars who have addressed the meaning of occupation, Nelson (Citation1996) defined meaning as “the sense that the person makes of a situation,” (p. 776) including their perceptual, symbolic, and affective experience. The meanings occupations hold are understood to motivate individuals’ performance of specific occupations (Trombly, Citation1995). In addition, the quality and meanings of occupation have been related to aspects of time and rhythm, with emphasis given to locating “the occupation within both the internal and the external temporal context of the individual” (Pemberton & Cox, Citation2011, p. 81) in order to understand the reciprocal relationship between occupation and time.

Contesting established categories of occupation, Hammell (Citation2004) argued that “occupation might be best understood, not as divisible activities of self-care, productivity and leisure, but as dimensions of meaning” (p. 297). Jonsson and Josephsson (Citation2005) further suggested that meaning experienced in daily occupations is socially and culturally constructed and that it is the occupations infused with positive meaning that contribute to individuals’ enhanced sense of well-being. This type of occupation can be present in all arenas, including work and leisure.

To advance knowledge of being engaged in occupation, some qualitative researchers have investigated the meanings members of the general population attribute to specific leisure occupations. For example, a small ethnographic study that explored choir singing found that it provides a sense of wholeness, derived from the supportive environment in which the occupation was situated and the combination of the challenges inherent in the occupation, which created opportunities to experience flow (Tonneijck, Kinébanian, & Josephsson, Citation2008). Exploring university students’ experience of participating in a leisure-based choir, another study revealed that feelings of accomplishment, the positive affect on mood, and the sense of community and social bonding were motivational factors for continued involvement (Jacob, Guptill, & Sumsion, Citation2009). Qualitative studies have also identified walking (Wensley & Slade, Citation2012) and gardening (York & Wiseman, Citation2012) to be valued leisure occupations with positive benefits for healthy and clinical populations, such as enhancing a sense of individual well-being and promoting a sense of community and social integration.

Dancing and well-being

Dance, as a topic of inquiry, has been explored from various viewpoints (e.g. dance therapy, dance education, history of dance). Some recent studies have explored how dance enhances well-being amongst healthy individuals. For instance, Kreutz (Citation2008) investigated the potential health benefits of tango Argentino (partnered dance) as a leisure pursuit. It was perceived to bring physical, social and emotional benefits, with the motivation for engaging in this form of dance “related to relaxation, enjoyment and mood management” (p. 82). Similarly, an exploratory study amongst non-professional amateur dancers identified six categories of perceived benefits: emotional, physical, self-esteem social benefits, coping strategies and spiritual beliefs (Murcia, Kreutz, Clift, & Bongard, Citation2010).

Occupational therapists have also reported a relationship between dance and well-being. Exploration of a recreational folk dance community programme for healthy women aged from 50 to 80 years emphasised the relevance of this initiative to the Australian health care system (Connor, Citation2000). Likewise, in an acute mental health setting in the UK, Froggett and Little's (Citation2012) evaluation of a dance programme carried out by a professional dancer in collaboration with hospital-based occupational therapists indicated that dance promotes a sense of relaxation, improves mood and facilitates cultural and social engagement. Within occupational science, Graham (Citation2002) discussed dance as a transformative occupation as it can “serve multiple functions, simultaneously develop the whole self, stimulate intimate and significant social relations, support optimal functioning through the lifespan” (p. 133).

Conceptualising circle dance

Circle dance is a revival of a very ancient art form, which for thousands of years allowed people from different cultures to express themselves through movement and dance. Historically, the circle is the earliest space form in dancing; there is evidence of circle dances in many traditions being performed by people from every continent (Sachs, Citation1937). Self-expression is not the primary aim and the process of learning movements and positions takes place within a social and cultural context (Norris, Citation2001).

Characterised by being vast and diverse, the circle dance repertoire includes traditional dances from different countries and cultures in addition to contemporary choreographies. The participants hold hands in a circle and repeat a pattern of steps, following the rhythm dictated by the music and related to specific dances. As a shared occupation, the integration and inclusion of the participants is a fundamental aspect of circle dance (Borges da Costa, Citation2012). Long term involvement is usually one feature of this group occupation. According to Machado Filho (Citation2005), circle dance can facilitate a sense of collective empathy. In this process, each individual becomes part of a whole unit (the circle), shifting the focus from the individual to the group, from the personal to the collective (p. 55).

In the United Kingdom, the Circle Dance movement emerged through the pioneering and innovative work of Bernhard Wosien (1908–1986), a former German ballet master, choreographer and a researcher of folk dances (Borges da Costa, Citation2014). Inspired by a research project related to folk dances carried out in 1952, Wosien's career as a dancer from 1962 was marked by his deep interest in traditional circle dances, their origins and cultural backgrounds, as well in the pedagogy of dance and the idea that dance should be available to all people. In October 1976, Wosien accepted an invitation to teach a compilation of folk dances and to present his ideas about using this form of communal dance at the Findhorn Community (Barton, Citation2011; Wosien, Citation2006, Citation2012), which is a “spiritual community, ecovillage and an international centre for holistic education” founded 50 years ago (Findhorn Foundation, Citationn.d.). Since then, the movement has spread throughout the UK and other European countries and to the rest of world. Currently, the Circle Dance network includes groups active in Africa, Australia, Europe, North America and South America.

Evidence of the use of circle dance as a strategy to promote well-being has been limited to a few studies in the field of mental health and education. Jerrome (Citation2002) evaluated the therapeutic use of circle dance in the UK with older people with dementia. This study highlighted positive outcomes such as a general sense of well-being, improved fitness and an opportunity to establish relationships within a group context. In Citation2012, a pilot study in East London, UK investigated the potential benefits of circle dance as a psychotherapeutic intervention in dementia (Hamill, Smith, & Röhricht, Citation2012). The findings suggested that dancing together in a circle enhanced the relationship amongst the participants, thereby promoting a sense of integration and connection, “at least for the duration of the sessions” (p. 716). In Brazil, a group intervention using music therapy and circle dance within a mental health service for adults found that it impacted the development of social identity and belonging (Leonardi, Citation2007).

From a Jungian psychology perspective, Hebling's (Citation2004) study with healthy art therapy students demonstrated that circle dance improved their quality of life, brought about positive modifications in body image, and impacted their sense of spirituality. Finally, the first author examined the introduction of circle dance in the curriculum of the School of Occupational Therapy at the University of São Paulo. The study evaluated students’ perceptions of the therapeutic elements of circle dance, highlighting particularly its application in mental health settings (Borges da Costa, Citation1998).

Although these studies provide interesting insights, they do not address the meanings of circle dance which, in the context of this study, is proposed to be a meaningful human occupation that encapsulates the elements of doing, being, becoming and belonging that can impact people's sense of well-being. The larger study aimed to provide an understanding of the subjective occupational experience among people who engage in circle dance (central research question) and the potential contribution of this leisure occupation to well-being through an occupational lens (Borges da Costa, Citation2014). The purpose of this paper is to explore the experience of meanings in circle dance as portrayed by circle dance participants.

Methods

This exploratory qualitative study applied a constructivist approach to grounded theory. Located in the constructivist paradigm, this version of grounded theory presupposes that the researcher plays an integral part in the research process and that both data and analysis are social constructions created through interaction between researcher and participants (Charmaz, Citation2006). From this perspective, the aim of the research process is an interpretative understanding of the studied experience, contextualised in time, place, culture, and situation. Accordingly, constructivist grounded theorists take a reflexive stand about their own interpretations as well as those of their research participants. In this study, the first author acknowledges that her own background and experience as an occupational therapist and circle dance teacher influenced the interpretation of the data. A research diary was kept as a way to facilitate reflexivity and as an audit trail of actions and decisions made throughout the research process.

From an occupational perspective, grounded theory is seen as a suitable methodology to study occupations in depth (Stanley & Cheek, Citation2003), generating new understandings of how occupations are enacted within daily life and the meanings behind individuals’ actions, considering the environment in which occupations take place (Nayar, Citation2011).

Participants

Following ethical approval granted by the University of Bolton Ethics Committee, access to the field was gained through the UK circle dance network. The broad inclusion criteria were UK residents over the age of 18 years who have engaged in circle dance. As the researcher is part of the circle dance network, and is familiar with the structure, this facilitated access to and recruitment of participants and helped to establish trust early in the course of the fieldwork (Morse, Citation2007).

In the larger study, 43 potential participants were contacted. Only four of them declined the offer at different stages: one before receiving the ethical forms, two after sending the signed consent form and one who did not return the consent form; no further explanation was requested and no further contact was made. Of the 39 participants interviewed, 22 were circle dance participants (discussed in this article), 15 were teachers, and two were teacher training coordinators. See for demographic information for the 22 circle dance participants.

Table 1. Circle dance participants’ demographic information

Prospective participants were initially contacted by email, phone or face-to-face. A brief explanation about the study as well as reassurance related to voluntary participation was given. They were then formally invited to take part in the study via mailed cover letter, participant information sheet, and informed consent form. Clarification at every stage of participation was offered and ensured by the researcher. Consent forms were stored with all other information and notes collected during this study in a secure manner and in accordance with the Data Protection Act 1998 and the University of Bolton's policy. Reassurance was also given in relation to confidentiality (Creswell, Citation2007).

Data collection and analysis

Since the focus of this study was on the participants’ lived experience of being engaged in circle dance, in-depth interviews explored their points of view, reflections and insights related to their experience. See for the interview questions. In-depth interviewing techniques are well-suited to grounded theory studies of topics of which participants have substantial experience (Charmaz, Citation2006) and are commonly used to advance knowledge of occupation and its contribution to health and well-being (Laliberte Rudman & Moll, Citation2001).

Table 2. Interview questions

Priority was given to face-to-face interviews (16). However, as some participants were located outside the researcher's geographical area, options such as Skype (Skype Technologies S. A., Citationn.d.) were used for the remainder (6). Interviews were in a private place where the interview would not be interrupted and it would be possible to use a digital voice recorder. All interviews were conducted by the first author and lasted 45–60 minutes. The initial open-ended interview questions were revised as the interviews progressed to inform the development of a conceptual framework grounded in the data (Charmaz, Citation2006). A research diary, field notes and memos were also used as data.

The verbatim transcription of all interviews was carried out by the primary author, removing participants’ names and other identifying information. Full transcripts were forwarded via email to participants who requested an opportunity to check for factual accuracy, amend any passages and add additional comments. Only four requested minor corrections and one added a comment.

Convenience sampling (Morse, Citation2007) was initially used to enter the field and gave an opportunity to identify the overall scope of the research process and determine the next stages of data collection. Initial coding related to the participants’ experiences, views, insights and perspectives, which prompted further purposeful sampling (Morse, Citation2007). This second stage, completed in February 2011, consisted of interviews conducted with four circle dance participants (F5, M6, F7, M10). As a result, preliminary categories were constructed through comparative methods in order to explicate ideas, events and processes in the data. To refine and establish the relevance of these categories, theoretical sampling, which refers to “seeking and collecting pertinent data to elaborate and refine categories” in the emerging theory (Charmaz, Citation2006, p. 96), was used until categories were saturated (Charmaz, Citation2006; Morse, Citation1995).

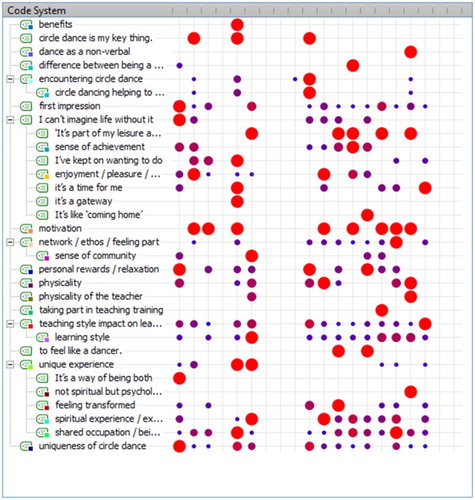

The analytical process incorporated the following stages: (1) initial coding (line-by-line) of the first set of interviews (November 2010), (2) focused coding of the second set of interviews (February 2011), (3) developing the preliminary categories into conceptual categories through theoretical sampling (July 2011 to April 2012); and (4) integrating the categories and sub-categories into a coherent process. Initial coding using gerunds was performed manually by writing notes, using a highlighter, and designing a table. This coding was exploratory and attempted to understand the participants’ experience by attending to actions and language (Charmaz, Citation2008). Focused coding was completed using MAXQDA (Citation2015) (see ). During this stage, the most relevant codes were selected as the first author compared data to data and data with codes.

In the larger study, the analytic process culminated with the development of major categories representing the meanings and experiences of circle dance participants, teachers and training coordinators. For the circle dance participants, the category “I can't imagine life without it” was derived from the constant comparative procedure, an essential element of grounded theory (Charmaz, Citation2006). In this process, categories and sub-categories were constructed in order to explicate ideas, events and processes in the data. As the early coding procedures broke the data up into their component parts, defining the actions implicated in the data, the emerging categories were brought together into a coherent narrative in order to move the analysis forward in a more theoretical way. Participants are identified by their gender (M/F) and registration number.

Findings

“I can't imagine life without it”

The category “I can't imagine life without it” provides a window into the participants’ experience and the meanings they attributed to circle dance, which they reported to be intrinsically rewarding and important in their lives. There were three sub-categories, each with two to four components.

Unique experience of being engaged in circle dance

Being engaged in circle dance was perceived to be a unique and meaningful experience, distinct from everyday occupations. Its components related to self-development, the feeling circle dance invokes, and a spiritual dimension of dancing together.

Self-investment, self-development

Finding deep fulfilment and enjoyment, the participants referred to circle dance as a form of self-investment or self-development. For many, it occupied a special place in their weekly schedule as they could attend on their own, independent of other important family members. One participant (F14) illustrated this in a clear statement:

I call it ‘My [her name] time’ … there's a lot about identity. It's about reinforcing who I am and getting in touch with that sense of self … because I'm not there being the [job role], or [X]’s partner or [Y]’s co-parent. It is just me … and I'm doing one of the things that I like doing best. So it's … something about myself, … almost like self-investment.

Engagement in circle dance was also related to self-development as it provided an opportunity to improve participants’ dancing skills and knowledge of the dances. For one participant (F31), who had been dancing for 21 years, circle dance was still regarded as a continuing and exciting learning opportunity. Another participant (F25) explained how the continued learning helped her to develop a sense of competence in the occupation.

Feeling transformed

For many participants, circle dance was a transformative way to feel revitalised and regenerated. It offered respite from the concerns and stresses of everyday life, and was associated with relaxation, renewal and feelings of happiness and contentment. One participant (M10) described how the process of transformation took place. By immersing himself in the dances and concentrating on the learning required, he forgot his problems and concerns, the worries of everyday life, and reached a state of relaxation, accompanied by feelings of happiness. Another (F26) described the transformation as being invigorating, “washing away” her tiredness after a day's work and generating a state of quietness and calmness during her busy week. A further participant (F21) emphasised the positive feelings she experienced:

When I have been to a circle dance group, either the evening group or a weekend or our residential group, I just feel so much lighter and so much happier inside, better in myself … and it is physical as well because, I mean, the sheer exercise is good for me and that has a good impact. But also I have been around such wonderful people and dancing with them makes me feel good! And I don't get that anywhere else to the same extent.

… a gateway to being something else whilst I'm also being myself. It's quite an intense experience for something that looks so … I don't know, simple really, but it's much more than that … so I think it helps me to get an inner peace. So it's becoming.

Feeling transported

Several participants explained how listening to the music and the collective sharing of patterns of movement induced a unique state of mind, sometimes occurring only occasionally, but intense enough to be significant for those involved. Being absorbed by the movements, the music and the dances, participants referred to one of the elements of flow, namely, the loss of self-consciousness, in which performers become one with their performance (Csikszentmihalyi, Citation1992). The idea of feeling transported to another level, away from everyday life experience, was often commented on. One man (M10), who had been circle dancing for 7 years, described his experience thus:

… when I'm doing circle dance, sometimes it transports you … it is like magic really … it is a bit difficult to explain … first you are thinking about what you are doing, and then … eventually … I find that it is almost hypnotic … and I float along … you feel it [the dance] flowing through your body. It is amazing really … it doesn't happen all the time … I don't know why it happens sometimes and it doesn't happen at other times … but sometimes the dance just flows and you just flow with the dance and you feel really good then.

Spiritual dimension of circle dance

In attempting to define elements of circle dance, a number of participants used terms such as “spirituality”, “spiritual experience” or “extra dimension”. For the purpose of this study, spirituality is defined as “a pervasive life force, manifestation of a higher self, source of will and self-determination, and a sense of meaning, purpose and connectedness that people experience in the context of their environment” (Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists; CAOT, Citation1997, p. 182). Spirituality “resides in persons, is shaped by the environment, and gives meaning to occupations” (CAOT, Citation1997, p. 33). The nature of spirituality experienced by many participants was described as feeling connected with the “divine” (F32) or “the universal life force”, (F20). For a female respondent (F36), dancing had always been the means to be in touch with “something bigger, which has no name” and to “have a great sense of being more alive”.

Feeling part of the ethos of circle dance

Capturing the element of belonging, the participants perceived the ethos of circle dance as a motivating factor for attending groups and suggested it provided an opportunity to develop and maintain connections with others. This sub-category had two components relating to the environment and the connections formed.

Supportive environment

Feeling supported and acknowledged by the other members of a circle dance group whilst maintaining one's individuality were aspects remarked upon by several participants. The supportive environment appeared to be constructed around the idea that circle dance attracts people who have similar characteristics and interests (circle dance, world music). Being welcoming, inclusive and friendly were some of personal attributes mentioned.

Circle dance was perceived as unique in the sense that this shared occupation is performed in a circle, enriching and instigating the development of relationships. Participating in a shared occupation means to align occupational performance with others to achieve a common goal. One participant (M18), who had been circle dancing for 9 years, talked about how “the pleasure of matching the movements to the rest of the group and to the music” made him feel an integral part of his group. His feelings of “enjoyment” derived from the collective action of dancing together. Another participant (F24) remarked that circle dance appeared to facilitate a sense of trust between people, based on qualities such as the honesty and openness that permeate the social world of circle dance.

Fostering connections

The participants frequently referred to the fact that circle dance fosters layers of connections: feeling part of a group, local community (regional or national level), and wider community (international level). One participant (F2) attributed this sense of connection to circle dance being a shared occupation that instigates a sense of cooperation, of being needed. She stated that dancers tend to leave their everyday problems aside, creating a different kind of atmosphere, and working together to learn, perform and enjoy the dances and the company of the group. For another participant (F20), taking part in circle dance meant a sense of belonging, of being part of a community of people who are “willing to share and help”.

The participants also expressed the feeling of being connected to a wider community that affords alternatives for change and brings possibilities. The fact that circle dancers have their own journal (The Grapevine), which lists all available groups in the UK, means they can go to other groups and workshops located in different geographical areas. If a participant moved to the other side of the country, it is very likely that she or he would find a local circle dance group and be able to continue engaging in this occupation. A participant (F17), with 9 years experience, talked about attending circle dance workshops in other locations and coming to realise she had became part of a wider community:

… after the first one, the next one you go to there will be somebody that you've met before. Yes, that's quite nice. And if there is somebody that you've never met before, then in the first dance you join hands … well, then that's alright! You don't need to know people to dance with them.

Circle dance helping to overcome difficulties in life

Circle dance had helped many participants overcome difficulties in their lives, including depression, stress, anxiety and bereavement. This topic was common across narratives of both circle dance participants and teachers and had two components relating to the security circle dance offers and managing one's health.

Sense of security & stability

One respondent (F32), who had been involved for 14 years, remarked how her local circle dance group represented an “anchor-point”, providing a sense of security and stability. Knowing that she could always attend the group due to its regular frequency (weekly), time and venue, allowed her to regard circle dance as “a sanctuary”, a constant occupation in her life, a space she could always rely on, with her circle dance friends there to help her in any circumstance. Another participant (F14) also realised this occupation had been specifically helpful during difficult periods in her life, mentioning the relevance of preserving circle dance in her routine and having the freedom to attend or return to it whenever necessary.

Managing ill health & recovery

The participants described, to varying extents, how circle dance became the means to manage difficult life circumstances and to overcome conditions such as severe depression. One participant (F33) talked about her circumstances 15 years previously: “I was off work with depression for 2 months and I thought: ‘I need to find ways to wind down’.” She also observed that her pathway to circle dance was very similar to other people in the network:

I don't think I'm unique in a lot of things I've said there. I've talked to a lot of people at circle dancing who've said to me that they were, possibly, unwell or depressed when they first started and they were looking for something that would help them to unwind. I know a lot of people who have mentioned that sort of thing.

Discussion

Being engaged in circle dance was perceived as a unique experience and distinct from other everyday occupations, as it created opportunities for self-investment, self-development, feeling transformed and feeling transported. Dedicating quality time to circle dance appeared to provide a sense of fulfilment and regeneration which influenced other areas of participants’ lives. This view of quality time or self-investment emphasised the richness of experience derived from being engaged in circle dance and its contribution towards their sense of well-being (doing, being, becoming and belonging components; Hammell, Citation2004). The participants referred to experiences closely aligned to one of the elements of flow, defined as loss of self-consciousness, in which “people become so involved in what they are doing that the activity becomes automatic; they stop being aware of themselves as separate from the actions they are performing” (Csikszentmihalyi, Citation1990, p. 53). The intense focus and concentrated attention on the movements, the music and the dances created opportunities to feel transported into a new reality. Flow has previously been discussed as the means by which “occupation may help people attain the highest level of well-being” (Wright, Citation2004, p. 73) and explaining the meaning of the experience of occupation (Jonsson & Josephsson, Citation2005; Wilcock & Hocking, Citation2015). This finding is similar to earlier research of the experience of choir singing (Jacob et al., Citation2009; Tonneijck et al., Citation2008).

The participants also identified the sense of unity derived from the experience of collective movement in which one participates voluntarily, as another element contributing to the sense of being transformed. It could be argued that circle dance provides people with the opportunity to experience “a ritual of shared time and space” (Pemberton & Cox, Citation2013, p. 4). The transcendental state evoked by engaging in circle dance, and sense of being more alive and connected with something bigger than themselves, also makes evident that the participants’ spirituality was closely related to self-fulfilment and self-enrichment derived from the practice of circle dance. This aspect parallels the concept of spirituality in occupation (CAOT, 1997), and appears to connect with the idea that traditional folk dances have religious and ritual origins (Wosien, Citation2006). Supporting earlier research on circle dance conducted in Brazil (Hebling, Citation2004), this may suggest that spirituality is part of the rewards of circle dance.

Circle dance also offers a social world, which gives some insight into the way circle dance, as a shared occupation, can facilitate a sense of belonging. Promotion of a sense of community and social integration has also been observed by York and Wiseman (Citation2012) in relation to gardening. This sub-theme may parallel one of the distinct qualities of serious leisure; its unique ethos and social world (Stebbins, Citation2007; Wensley & Slade, Citation2012). It was clear from the participants’ accounts that the social rewards of circle dance were central to sustaining their engagement. Their sense of cooperation, helping, and being needed also came together in the practice of circle dance. Capturing a component of belonging (Wilcock, Citation2007), the participants also suggested that circle dance provided an opportunity to develop and maintain connections with others. Once immersed in the ethos of circle dance, they appear to gain a social identity as circle dancers that allows them to circulate between various events, regular classes or workshops. It could be argued that the social support found in the circle dance network encourages dancers to sustain their engagement, providing opportunities for social integration.

Circle dance appeared to be a significant leisure occupation in which self-fulfilment, transformation, and self-regeneration are some of the perceived benefits. It was evident that involvement with circle dance helped participants overcome difficulties in their lives and continued to be important in their recovery process. This finding aligns with earlier assertions that dance therapy provides “unique multisensory, emotional, cognitive, and somatic” (Hanna, Citation1995, p. 329) experiences when part of broad treatment programmes or a primary intervention modality. Similarly, dance has been used in chronic diseases, mental and physical health prevention and management, both in a health care context and in community settings (Ward, Citation2008).

Limitations and future research

The method of data collection in this study was primarily in-depth interviews. The addition of other sources of data might have expanded the categories. For example, a focus group might have revealed group opinions, refining and extending points generated by individuals. The use of participants’ diaries might have also offered significant insights. Additionally, a comparative study of circle dance, investigating the experience of circle dance participants in different countries could reveal how meanings are constructed, taking into consideration social and cultural differences.

Conclusion

The major category “I can't imagine life without it” and its sub-categories offered deep insight into the meanings and purposes attributed to circle dance. For the participants, meanings were gained through the experiential nature of circle dance, which influenced their sense of well-being and promoted the quality of their experience. Placed in a position of high significance, circle dance appeared to be selected by the participants as a leisure occupation in which self-development, transformation, self-regeneration are some of the perceived benefits. The findings suggest that, as a multifaceted occupation, circle dance creates meaning and is of potential relevance to a healthy lifestyle, influencing people's health and well-being.

Acknowledgement

This research was part of a larger doctoral study completed by the first author at the Centre for Research for Health and Wellbeing, University of Bolton.

ORCID

Ana L. Borges da Costa http://orcid.org/0000-0003-1124-0694

Diane L. Cox http://orcid.org/0000-0003-2691-6423

References

- Barton, A. (2011). Sacred dance at the Findhorn Foundation. In J. King (Ed.), The dancing circle - Volume 5: Back to our roots (pp. 53–56). Winchester, UK: Sarssen Press.

- Borges da Costa, A. L. (1998). Dance: The heritage within everybody's hands. In R. Ramos (Ed.), Sacred circle dance: A proposal for education and health (pp. 19–24). São Paulo, Brazil: Triom.

- Borges da Costa, A. L. (2012). Circle dance, occupational therapy and well-being: The need for research. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 75(2), 114–116. doi:10.4276/030802212X13286281651315

- Borges da Costa, A. L. (2014). An investigation into circle dance as a medium to promote occupational well-being. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Bolton, UK.

- Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists. (1997). Enabling occupation: An occupational therapy perspective. Ottawa, Canada: CAOT Publications ACE.

- Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. London, UK: Sage.

- Charmaz, K. (2008). Grounded theory as an emergent method. In S. N. Hesse-Biber & P. Leavy (Eds.), Handbook of emergent methods (pp. 155–170). London: The Guilford Press.

- Connor, M. (2000). Recreational folk dance: A multicultural exercise component in healthy ageing. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 47(2), 69–76. doi:10.1046/j.1440-1630.2000.00214.x

- Creek, J. (2003). Occupational therapy defined as a complex intervention. London, UK: College of Occupational Therapists.

- Creswell, J. W. (2007). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (2nd ed.). London, UK: Sage.

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. New York, NY: Harper Collins Publishers.

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1992). Flow: The psychology of happiness. London, UK: Rider.

- Findhorn Foundation. (n.d.). Vision. Retrieved from http://www.findhorn.org/aboutus/vision/#.UlaOhNKko2s

- Froggett, L., & Little, R. (2012). Dance as a complex intervention in acute mental health setting: A place ‘in-between’. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 75(2), 93–99. doi:10.4276/030802212X13286281651153

- Graham, S. F. (2002). Dance: A transformative occupation. Journal of Occupational Science, 9(3), 128–134. doi:10.1080/14427591.2002.9686500

- Hammell, K. W. (2004). Dimensions of meaning in the occupations of daily life. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 71(5), 296–305. doi:10.1177/000841740407100509

- Hammell, K. W. (2009). Sacred texts: A skeptical exploration of the assumptions underpinning theories of occupation. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 76(1), 6–13. doi:10.1177/000841740907600105

- Hamill, M., Smith, S., & Röhricht, F. (2012). ‘Dancing down memory lane’: Circle dancing as a psychotherapeutic intervention in dementia – A pilot study. Dementia, 11(6), 709–724. doi:10.1177/1471301211420509

- Hanna, J. L. (1995). The power of dance: Health and healing. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 1(4), 323–331. doi:10.1089/acm.1995.1.323

- Hasselkus, B. R. (2011). The meaning of everyday occupation (2nd ed.). Thorofare, NJ: Slack.

- Hebling, L. H. (2004). Sacred circle dance: Body image, quality of life and religiosity - A Jungian perspective. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Campinas, Brazil.

- Hocking, C. (2000). Occupational science: A stock take of accumulated insights. Journal of Occupational Science, 7(2), 58–67. doi:10.1080/14427591.2000.9686466

- Hocking, C. (2009). The challenge of occupation: Describing the things people do. Journal of Occupational Science, 16(3), 140–150. doi:10.1080/14427591.2009.9686655

- Jacob, C., Guptill, C., & Sumsion, T. (2009). Motivation for continuing involvement in a leisure-based choir: The lived experience of university choir members. Journal of Occupational Science, 16(3), 187–193. doi:10.1080/14427591.2009.9686661

- Jerrome, D. (2002). Circles of the mind: The use of therapeutic circle dance with older people with dementia. In D. Waller (Ed.), Arts therapies and progressive illness: Nameless dread (pp. 165–182). East Sussex, UK: Brunner-Routledge.

- Jonsson, H., & Josephsson, S. (2005). Occupation and meaning. In C. H. Christiansen & C. M. Baum (Eds.), Occupational therapy: Performance, participation and well-being (pp. 116–133). Thorofare, NJ: Slack.

- Kreutz, G. (2008). Does partnered dance promote health? The case of tango Argentino. Journal of the Royal Society for the Promotion of Health, 128(2), 79–84. doi:10.1177/1466424007087805

- Laliberte Rudman, D., & Moll, S. (2001). In-depth interviewing. In J. Valiant Cook (Ed.), Qualitative research in occupational therapy: Strategies and experience (pp. 24–57). Albany, Canada: Delmar.

- Leonardi, J. (2007). The noetic path: Singing and circle dance as vehicles of the existential health in care. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of São Paulo, Brazil.

- Machado Filho, P. T. (2005). Danças circulares e suas correlações psicofísicas, espirituais e integrativas (Circle dances and their psychophysical, spiritual and integrative correlations). Jung & Corpo, 5(5), 49–59.

- MAXQDA. (2015). Qualitative data analysis software (Version 12). Berlin, Germany: VERBI Software GmbH.

- Morse, J. M. (1995). The significance of saturation. Qualitative Health Research, 5(2), 147–149. doi:10.1177/104973239500500201

- Morse, J. M. (2007). Sampling in grounded theory. In A. Bryant, & K. Charmaz (Eds.), The Sage handbook of grounded theory (pp. 229–244). London, UK: Sage.

- Murcia, C. Q., Kreutz, G., Clift, S., & Bongard, S. (2010). Shall we dance? An exploration of the perceived benefits of dancing on well-being. Arts & Health, 2(2), 149–163. doi:10.1080/17533010903488582

- Nayar, S. (2011). Grounded theory: A research methodology for occupational science. Journal of Occupational Science, 19(1), 76–82. doi:10.1080/14427591.2011.581626

- Nelson, D. L. (1996). Therapeutic occupation: A definition. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 50(10), 775–782. doi:10.5014/ajot.50.10.775

- Norris, R. S. (2001). Embodiment and community. Western Folklore, 60(2-3), 111–124. doi:10.2307/1500372

- Oxford Dictionaries. (2015). Oxford dictionaries language matters. Retrieved November 11, 2015 from http://www.oxforddictionaries.com

- Pemberton, S., & Cox, D. (2011). What happened to the time? The relationship of occupational therapy to time. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 74(2), 78–85. doi:10.4276/030802211X12971689814043

- Pemberton, S., & Cox, D. (2013). Perspectives of time and occupation: Experiences of people with chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis. Journal of Occupational Science, 21(4), 488–503. doi:10.1080/14427591.2013.804619

- Sachs, C. (1937). World history of the dance. New York, NY: Norton.

- Skype Technology S. A. (n.d.). Home page. Retrieved November 21, 2011, from http://skype-technologies-s-a1.software.informer.com/

- Stanley, M., & Cheek, J. (2003). Grounded theory: Exploiting the potential for occupational therapy. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 66(4), 143–150. doi:10.1177/030802260306600403

- Stebbins, R. A. (2007). Serious leisure: A perspective for our time. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers.

- Tonneijck, H. I. M., Kinébanian, A., & Josephsson, S. (2008). An exploration of choir singing: Achieving wholeness through challenge. Journal of Occupational Science, 15(3), 173–180. doi:10.1080/14427591.2008.9686627

- Trombly, C. A. (1995). Occupation, purposefulness and meaningfulness as therapeutic mechanisms. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 49(10), 960–972. doi:10.5014/ajot.49.10.960

- Ward, S. A. (2008). The voice of dance education – past, present and future: Health and the power of dance. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance, 79(4), 33–36. doi:10.1080/07303084.2008.10598161

- Wensley, R., & Slade, A. (2012). Walking as a meaningful leisure occupation: The implications for occupational therapy. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 75(2), 85–92. doi:10.4276/030802212X13286281651117

- Wilcock, A. A. (1998). Reflections on doing, being and becoming. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 65(5), 248–256. doi:10.1177/000841749806500501

- Wilcock, A. A. (1999). Reflections on doing, being and becoming. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 46(1), 1–11. doi:10.1046/j.1440-1630.1999.00174.x

- Wilcock, A. A. (2007). Occupation and health: Are they one and the same? Journal of Occupational Science, 14(1), 3–8. doi:10.1080/14427591.2007.9686577

- Wilcock, A. A., & Hocking, C. (2015). An occupational perspective of health (3rd ed.). Thorofare, NJ: Slack.

- Wosien, B. (2006). The dancer's journey: Self-realisation through movement. Findhorn, Scotland: Findhorn Foundation.

- Wosien, B. (2012). About the sacred dances. In F. Kloke-Eibl (Ed.), My dance – A song of silence (pp. 8–11). Oberthingau, Germany: Rondo.

- Wright, J. (2004). Occupation and flow. In M. Molineux (Ed.), Occupation for occupational therapists (pp. 66–67). Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing.

- Yerxa, E., Clark, F., Frank, G., Jackson, J., Parham, D., Pierce, D., … Zemke, R. (1990). An introduction to occupational science, a foundation for occupational therapy in the 21st century. Occupational Therapy in Health Care, 6(4), 1–17. doi:10.1080/J003v06n04_04

- York, M., & Wiseman, T. (2012). Gardening as an occupation: A critical review. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 75(2), 76–84. doi:10.4276/030802212X13286281651072