ABSTRACT

The consumption of performance and image-enhancing drugs (PIEDs) is commonly pathologised in public health discourse as stemming from an unhealthy relationship to masculinity, and is often framed as intrinsically ‘risky’ and fundamentally at odds with ‘good health’. This article examines Australian health promotion materials on PIEDs to analyse their role in shaping notions of good health, normal gender and appropriate self-improvement. To do so, it draws on the work of Butler, Law and Latour to consider how these materials co-constitute men and their health, often in problematic ways. First, we examine the ways in which PIEDs are constituted via a politics of the ‘natural’, then consider how the health promotion materials on PIEDs participate in the regulation of appropriate, healthy masculinity, and conclude by examining how adolescent masculinity is co-constituted with PIEDs. We observe a key tension between health promotion’s avowed interest in improvement and optimisation and its treatment of PIED consumers as aberrant, vulnerable and insecure subjects whose drive to enhance and optimise is characterised by pathology and addiction. We conclude by arguing that health promotion materials on PIEDs fail to acknowledge the exceedingly normative character of enhancement practices in contemporary society.

Introduction

Maintaining and optimising health is an important component of contemporary neoliberal subjecthood (Lupton, Citation1995). A health-enhancing disposition towards the self is constituted as morally good, and those who are unwilling or unable to comply – who ‘choose’ to neglect their health and wellbeing – are often stigmatised (Petersen & Lupton, Citation1996; see also Seddon et al., Citation2012). Men’s PIED consumption is commonly pathologised in public health discourse as stemming from an unhealthy relationship to masculinity, and is often framed as intrinsically ‘risky’ and fundamentally at odds with the production and maintenance of ‘good health’ (Keane, Citation2005; Moore et al., Citation2020). In this article we employ theoretical insights developed by Butler (Citation1999), Law (Citation2004) and Latour (Citation2013) to analyse Australian public health discourse on PIED consumption, arguing that its mobilisation of concepts of health and masculinity instantiates important tensions with significant regulatory effects. We attend specifically to Australian health promotion materials on PIEDs, identifying an important theme in these materials: that men’s accounts of PIED use analysed as part of our project and reported on by others (i.e. Fomiatti et al., Citation2019; Fomiatti et al., Citation2020; Latham et al., Citation2019; Monaghan, Citation2001) are consistent with the health promotion injunction to become health-conscious, self-managing and self-optimising, rather than contrary to it. Our analysis has three parts: first, we examine the ways in which PIEDs are constituted via a politics of the ‘natural’, then consider how these health promotion materials on PIEDs participate in the regulation of appropriate, healthy masculinity, and conclude by examining how adolescent masculinity is co-constituted with PIEDs. Conceptions of health are enrolled in these dynamics in a range of complex ways that expose a distinctly gendered anxiety: that through PIED consumption and emerging understandings of health, masculinity may be in the process of embracing traditionally ‘feminine’ – and therefore assumed to be inferior – practices of bodily enhancement. As part of this, we argue that the concept of health itself – and the production of ‘good health’ – is also being refigured as an enhancement practice, which has important implications for gender. We conclude by arguing that health promotion materials about PIEDs fail to acknowledge the exceedingly normative character of enhancement practices in contemporary society.

Background

The term ‘PIEDs’ covers a diverse range of substances, practices, motivations and consumers. The category conventionally includes anabolic-androgenic steroids, testosterone, anti-oestrogenic agents, beta-2 agonists (e.g. clenbuterol), chorionic gonadotrophin, human growth hormone, insulin, diuretics and peptides (Australian Criminal Intelligence Commission [ACIC], Citation2018). Research suggests amateur athletes, older men and occupational users (e.g. fitness trainers, security guards) comprise the majority of men who consume PIEDs. Motivations for use are diverse, but are typically related to strength and athletic performance, and image-related benefits such as increased muscle mass and fat loss (Van de Ven et al., Citation2018; Zahnow et al., Citation2018). While some of these substances are injected, others are administered orally or topically. In general, the consumption of PIEDs is understood to be increasing in Australia (ACIC, Citation2021, p. 102) and elsewhere, including the United Kingdom and the United States (cited in Seear et al., Citation2015).

Medical, public health, psychological and epidemiological research identifies a range of perceived risks and dangers associated with PIED consumption. These include damage to the liver, reproductive organs and heart (Kutscher et al., Citation2002), and the risk of blood-borne virus (BBV) transmission associated with poor injecting technique and practices (McVeigh & Begley, Citation2017), as well as ‘behavioural issues’ such as increased aggression, depression, conduct disorder, changes in libido, anxiety and paranoid jealousy (Onakomaiya & Henderson, Citation2016). These risks are understood to be compounded due to PIED consumers being an especially hard-to-reach group for targeted health promotion and health services (Maycock & Howat, Citation2005). Overall, this literature enacts PIED consumers as vulnerable, disordered and pathological (Keane, Citation2005; Moore et al., Citation2020), and as at risk of spreading BBVs. The health promotion materials currently circulating in Australia aim to address these concerns, but they have yet to be critically scrutinised.

The term ‘health promotion’ was first used in 1974 by Marc Lalonde, then Canadian Minister for Health, to argue that improvements in ‘lifestyle’ could reduce health problems (Macdonald & Bunton, Citation1992; cited in Fraser & Seear, Citation2011). Health promotion is now endorsed by the World Health Organization (WHO), which frames it as comprising preventative interventions designed to ‘benefit and protect individual people’s health and quality of life’ (WHO, Citation2021). Since the 1970s in Australia, health promotion ‘has flourished at both national and state levels where government bodies have been structured, health promotion foundations established and, in universities, health promotion teaching programs introduced’ (Fleming & Parker, Citation2020, p. xii).

Literature review

Developments in public health and health promotion have long been analysed by sociologists of health and medicine. Petersen and Lupton (Citation1996) argue that the ‘new public health’ – of which health promotion is a part – requires individuals to ‘take responsibility for the care of their bodies’, which involves actively managing their relationship to risk (understood to be ‘everywhere and in everything’) (p. ix). These insights have been taken up in a range of fields, including by critical drug scholars, and applied to analyses of drug use-related health promotion materials (e.g. Fraser & Seear, Citation2011; Moore & Fraser, Citation2006; Winter et al., Citation2013). These studies have analysed the particular subjects, conceptions of health, risk, disease and bodies, and gendering processes enacted through health promotion, arguing that its assumptions about the rational, choosing subject are problematic and naïve to the material constraints faced by those addressed by these resources and discourses.

Health promotion, enhancement and gender

As others have noted, health promotion enacts an approach to health and the subject that is consistent with a neoliberal ideology of individual responsibilisation, particularly in relation to the management of risk. In investigating the contemporary ‘healthism’ project, Petersen and Lupton (Citation1996) argue that health:

has come to be used as a kind of shorthand for signifying the capacity of the modern self to be transformed through the deployment of various ‘rational’ practices of the self. Health is viewed as an unstable property, something to be constantly worked on. (Petersen & Lupton, Citation1996, p. xiv, emphasis added)

Importantly, Petersen and Lupton (Citation1996) identify an emphasis on enhancement as central to the project of neoliberalism. Here:

[the] state is positioned as not domineering, repressive or authoritarian, but rather as part of a set of institutions and agencies that are directed at enhancing personal freedoms and individual development. (Petersen & Lupton, Citation1996, p. 12, emphasis added)

Sociological qualitative work on PIED consumption

Critical sociological literature on men’s PIED consumption is relatively scant. In contrast to the various risks associated with PIEDs through medical discourses, Monaghan (Citation2001) notes the ‘vibrant physicality’ reported by many steroid consumers, and emphasises the need to acknowledge experiences of health and vitality that may co-exist with bodywork practices often constituted as ‘risky’, such as drug consumption.

An influential thread of sociological work in the field that has come to be known as critical drug studies identifies health – and associated concepts of risk and harm – as a set of discourses that relate to power and politics (e.g. Keane, Citation2002; Fraser & valentine, Citation2008; Fraser et al., Citation2014). Critical drug studies scholarship on PIEDs (e.g. Fomiatti et al., Citation2019; Fomiatti et al., Citation2020; Fraser et al., Citation2020; Keane, Citation2005; Latham et al., Citation2019; Moore et al., Citation2020; Seear et al., Citation2020) has analysed the ways in which dominant accounts of PIEDs stabilise specific limiting ‘truths’ about these drugs, their consumers and their health. Some of these studies have, like Monaghan, emphasised the increased sense of health and wellbeing reported by PIED consumers (see Fomiatti et al., Citation2019; Fomiatti et al., Citation2020; Latham et al., Citation2019), and the increases in physical, vocational, and other affective capacities such as increased confidence attributed to their PIED consumption. This sits in stark contrast to the constitution of the ‘male PIED consumer’ enacted in medical and psychological research and, as we demonstrate, in health promotion, which struggles to resolve the risks attributed to drug-using bodies and understandings of health and vitality enacted by PIED consumers.

Approach

To conduct our analysis, we draw on the work of Butler (Citation1999), Law (Citation2004) and Latour (Citation2013). Each raises ontological questions about the body that are relevant to our analysis. Judith Butler’s (Citation1999) concept of gender performativity, which posits that gender is not the product of natural sexed bodies, but an iterative practice that, in contrast, creates the effect of natural sex. We employ Butler’s (Citation1999) theorisation of gender to offer a detailed account of the practices that constitute ‘men’, ‘masculinity’ and the ‘natural’ male body alongside PIEDs. Among the PIEDs literature that engages with masculinity more critically, Connell’s (Citation1995) concept of ‘hegemonic masculinity’ is frequently cited. Within this framing, the enacted primary appeal of steroids is their capacity to provide otherwise subordinated or marginalised men with the means to become more powerful and valued by becoming more masculine through the development of a particular embodied look (e.g. Andreasson & Johansson, Citation2016; Basaria, Citation2018; Filiault & Drummond, Citation2010). While it has been important to have accounts of how consumers perceive their PIED use as instrumentally cultivating their masculinity, this literature tends to contribute to the production of stigmatising accounts of the compensatory male steroid user (Keane, Citation2005) within the social sciences. Thinking with Butler (Citation1999) helps us to counter prevailing, pathologising discourses relating to men’s use of PIEDs (Keane, Citation2005; Moore et al., Citation2020) by aiding an examination of the ‘variety of ways in which men consume PIEDs, particularly those experiences understood as positive or beneficial’ (Latham et al., Citation2019, pp. 151–152).

We combine this approach with that of science and technology studies scholar John Law, who, among other contributions, mobilises Butler’s (Citation1999) concept of performativity to position entities other than sex as likewise ontologically unstable, the effect of repetition or iteration, and therefore emergent and open to change. A further set of tools informing our analysis derives from the late Bruno Latour, specifically his work on ‘modes of existence’ (Citation2013). Latour argues that a key feature of the present historical moment is that key institutions – such as science, the law and religion – each claim to have access to the truth, enacted as singular, yet rendered very differently in each case. This has the effect of creating multiple, competing truth claims, which Latour diagnoses as a distinctly modern predicament. In his book An Inquiry into Modes of Existence (2013), Latour identifies and describes 15 modes, each with its own distinct practices and principles of assessing and making truth, which he calls processes of veridiction. As part of these processes, each mode has its own ‘felicity conditions’ through which it operates ‘explicitly and consciously to decide what is true and what is false’ (Latour, Citation2013, p. 53).

The analysis presented in this article considers health promotion as its own mode of existence, one that works to ‘veridict’ specific realities of PIEDs, PIED consumers and gender. Our analysis pays attention to health promotion’s unique conventions, including its history and aims as a practice and the qualities of its forms – for instance, websites, factsheets and pamphlets. In doing so, we aim to show how these elements actively shape the ‘truths’ about PIEDs and the PIED-using body represented within them, and that different ways of ‘addressing’ PIED use among men actually perform men and their health in different, sometimes problematic, ways. Our approach then examines the regulatory effects of these relations (Butler, Citation1999) and, crucially, highlights the possibility that they might be remade in other, less harmful, ways (Butler, Citation1999; Law, Citation2004).

Method

The dataset for this article comprises 18 Australian health promotion materials collated via online Google searches in June 2018 (n = 8) and February 2020 (n = 10) using the terms ‘performance and image enhancing drug education’, ‘performance and image enhancing drug health resources’, ‘steroid(s) education’ and ‘steroids health resources’. The materials were produced by government and non-government organisations and include pamphlets, factsheets, booklets and websites. They offer definitions of PIEDs, list their effects, describe motivations for use and contain contact details if ‘further help’ is required. Many of the resources are short (one to two pages) while some are longer (up to seven pages). Some use images of young men or diagrams of bodies to, in various ways, illustrate the harms of PIEDs. The resources were developed for a variety of purposes: to inform consumers of the risks associated with PIED use and/or safer drug use practices viewed from a harm reduction perspective; to assist teachers, parents, and sporting and school communities to access drug education resources and prevention programmes; and to assist health practitioners in servicing PIED consumers.

Analysing health promotion as its own mode of existence (Latour, Citation2013) demands attention to its ‘unique history, aims, objectives, epistemology and ontology’ (Fraser & Seear, Citation2011, p. 42) combined with attention to the specific forms of the materials gathered. For instance, websites construct meaning through features specific to their form, such as hyperlinks (Mitra & Cohen, Citation1999), which must be attended to in the analysis. Likewise, the textual genre of brochures and pamphlets is analysed for how the resources organise text and images in a selective way to promote and persuade (Francesconi, Citation2011). Recognising the formal qualities of these health promotion texts is key to performing a thorough analysis of veridiction processes, because the textual strategies adopted by each act uniquely in making – in highly specific ways – PIEDs, health and masculinity.

The dataset was analysed using the inductive constant comparison method (Seale, Citation1999), which entails alternating between the data and thematic coding, consolidating what is identified with what has already been identified, until the emerging themes become repetitive. Initial themes were identified on the basis of existing research and our theoretical approach. Seale’s (Citation1999) iterative process is consistent with the theory mobilised in this article, which emphasises performative ontologies of iteration. Both acknowledge the ways in which ‘realities’ emerge via repetitive processes. For instance, the figure of the adolescent boy emerged as a key theme from the dataset through reading and re-reading the health promotion materials alongside the broader literature on PIEDs, health and masculinity. The adolescent male is constituted specifically in these materials as a product of the mode of health promotion and co-constituted with concepts of PIEDs, health, enhancement and masculinity, and is likewise stabilised as a subject of analysis via research processes (reading and re-reading datasets, analysing the adolescent as an emerging subject-position, presenting the analysis here).

Analysis

Our key observation in analysing Australian health promotion materials is that while health promotion warns against PIED consumption, its foundation in neoliberal values of progress and improvement means it is consistent with, rather than in contrast to, consumer interest in enhancement (see Fomiatti et al., Citation2019; Fraser et al., Citation2020; Latham et al., Citation2019; Monaghan, Citation2001). This association presents a unique challenge for health promotion, which must discursively distinguish between ‘healthy’ and ‘problematic’ enhancement. In the analysis that follows, we demonstrate how health promotion materials that focus on PIEDs uniquely constitute health in ways that bring into focus the somewhat paradoxical contemporary aspiration to, and condemnation of, enhancement of male bodies.

Constituting PIEDs via a politics of the ‘natural’

This section explores ways in which concepts of the natural discursively co-constitute PIEDs and concepts of ‘good health’. Perhaps the most obvious observation to make about the materials analysed here is that they constitute PIEDs as unnatural and foreign substances, setting the ‘healthy’ body against them and co-constituting it in contrast in taken-for-granted ways as natural, uncontaminated, bounded and stable. Helping compose this contrast, the most commonly used images in the dataset are images of vials and syringes. For instance, the two images below are featured in the Australian Government Department of Health's (2017) booklet about PIEDs, and similar images are found in many of the other resources.

Such images of vials and syringes () appear clinical and technical, emphasising the unnatural status of PIEDs (for an analysis of the cultural constitution of vials and syringes, see Vitellone, Citation2017). These qualities are reinforced in the descriptions of relevant substances such as anabolic steroids, peptides and hormones, which mobilise the language of chemistry against that of nature: steroids are ‘synthetic drugs’ that are ‘based on the structure of testosterone’; and ‘there are numerous artificial hormones available, as well as drugs that stimulate the production of hormones’. Each of these definitions highlights the artificiality of the substances and, accompanied by the image of syringes and vials, thoroughly constitute PIEDs as not of the body. The constitution of a substance as ‘foreign’ and unnatural has, since the late nineteenth century, been central to its enactment as a ‘drug’ that can be ‘abused’ (Sedgwick, Citation1993). Conversely, enacting some substances as natural allows them to be separated from the ‘drug’ category and marketed and sold as health products (Conrad & Potter, Citation2004).

Figure 1. ‘PIEDs’ as constituted in health promotion (Australian Government Department of Health, Citation2017).

The distinction between the natural and the unnatural, and its use to delineate the problematic from the normal, is found throughout our health promotion dataset. One example is provided by the Better Health Channel’s website (managed and authorised by the Victorian Department of Health). On it, a factsheet about anabolic steroids (2020) states that ‘anabolic steroids are a group of synthetic drugs that copy the masculinising effects of the male hormone, testosterone’. It draws on the mode of medicine to veridict a distinction between legitimate medical use and illegitimate non-medical use, saying that there ‘are some legitimate medical uses for anabolic steroids’ before saying that ‘people who misuse anabolic steroids may include athletes, bodybuilders and people who feel they need to look muscular to feel good about themselves’. Like other materials in this dataset, this factsheet enacts steroids as synthetic substances that artificially imitate natural hormonal processes, and hints at the insecurity of those who consume them.

The ontology of PIEDs as artificial imitators of the natural enacted in health promotion materials can be seen to gender both the drugs and, by extension, their consumers. Here, the illicit consumption of steroids is again problematised via the notion of artifice: they are used ‘illegitimately’ to increase muscle. In this respect, PIEDs are enacted as allowing their consumers to ‘fake’ who they are. Fraser and valentine (Citation2008) explore the politics of copy and repetition in relation to drugs in a chapter of their book on methadone maintenance treatment. They note that repetition has ‘figured as feminine in Western thought, and simultaneously judged inferior’ (Citation2008, p. 147), citing Simone De Beauvoir’s (Citation1949) account of femininity as mere sisyphean reproduction to argue that Western culture constructs addiction, repetition and femininity as synonymous. All three, the authors argue, are thereby ‘judged inferior to masculine values of autonomy, creativity and activity’ (Citation2008, p. 148), precluding authenticity, originality and agency. Likewise, health promotion materials present PIEDs as artifice: PIEDs are mere copies or artificial iterations of natural (masculine) hormones and are thus coded as feminine, and therefore as ontologically disruptive. Thinking with Butler (Citation1999) and Law (Citation2004) helps us to unpack such implicit and explicit claims to the natural to observe the ways in which they participate in the constitution and regulation of gender (along with that of drugs and health). Here, we argue that iterations of natural masculinity attempt to co-constitute PIED consumption as problematic on the basis that it amounts to illegitimate and misguided improvement; enhancement of the wrong kind and by the wrong means.

Meanwhile, alongside these enactments of what PIEDs ‘are’ and what they ‘do’ to the (natural, healthy) body, is the injunction that those who consume PIEDs need to recognise the risks and the nature of their ‘problem’ and take steps to ‘get better’. For example, a web page on PIEDs published by the youth alcohol and other drug prevention organisation Youth Solutions (accessed, Citation2021)Footnote1, and funded by the NSW Health Department, offers a section titled ‘Further information and support’, which begins by referring to crisis situations such as a suspected drug overdose or other emergency and instructing readers to ‘call triple zero (000) immediately’.Footnote2 This section also presents hyperlinks to the Australian Sports Anti-Doping Authority ‘for more information about drugs in sport, banned substances and support information’, to another health promotion web page about PIEDs and to the Youth Solutions ‘Get Help’ page ‘for the details of different support services available’. These kinds of injunctions to seek help are common throughout the dataset, building a general orientation to PIED consumption as aberrant and problematic. They are also readable as features of a specific health promotion mode of existence (Latour, Citation2013), in which subjects are responsibilised to seek help, to reflexively improve and do better; in other words, to self-enhance (see also Fraser & Ekendahl, Citation2018, on drugs and ‘getting better’).

The politics of ‘getting better’ (Fraser & Ekendahl, Citation2018) is, we argue, what these health promotion materials are attempting to enact and police. As all these examples demonstrate, one such way is through drawing boundaries around the ‘healthy’ body by drawing heavily on discourses of the natural. PIEDs are co-constituted with notions of artifice, repetition and irrationality, and are thus discursively aligned with the feminine (Tanner et al., Citation2013). It is against these qualities that ideal healthy masculinity is enacted as rational, natural and authentic, even as the distinctions between the natural/healthy and the unnatural/unhealthy emerge as arbitrary and political.

Regulating appropriate, healthy masculinity

In this section, we further examine the co-constitution of PIEDs, health and gender, and how these work to regulate appropriate, healthy masculinities and enhancements. As already noted, a key discursive issue for health promotion materials about PIEDs is how to handle the desire for masculine enhancement, given that health promotion, too, incites enhancement as a key value. Here, we examine diagrams of the body included in the health promotion materials to argue that the desire for performance and image enhancement through drug consumption is constituted as unhealthy and risky via articulations of severely disrupted binary sex.

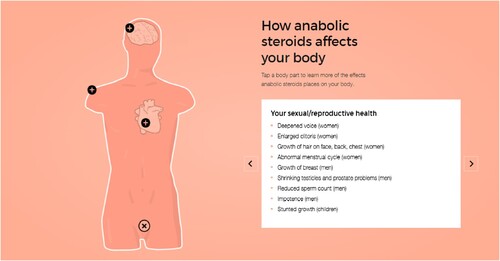

Body diagrams appear in two of the health promotion materials analysed here, both of which represent the generic body as male, upon which the risks of PIEDs are illustrated. While there are only two diagrams of their kind in the dataset, they are illustrative of a broader concern common across the health promotion materials with the capacity of PIEDs to disrupt and make unintelligible the natural, unambiguously sexed body. is an image found on the NSW Health Department’s Your Room web page about steroids (2018), which outlines the effects of steroids on ‘sexual/reproductive health’.

Figure 2. The effects of steroids on the body (Your Room, Citation2018).

Here, steroid effects are listed according to sex: women are at risk of developing a ‘deepened voice’, ‘enlarged clitoris’, ‘growth of hair on face, back and chest’, and an ‘abnormal menstrual cycle’. Meanwhile, men are said to risk developing ‘growth of breasts’, ‘shrinking testicles and prostate problems’, ‘reduced sperm count’ and ‘impotence’. Most of these materials emphasise the capacity of PIEDs to reverse and disrupt supposedly ‘normal’ and natural, unambiguously binary, sexed bodies. Throughout PIED discourses in general, and these health promotion materials in particular, steroids are continually enacted as analogous to testosterone (whether natural or artificial), and this is presented as intrinsically male even though women’s bodies also produce this hormone (Fine, Citation2017). At the same time, the risks of consuming steroids are presented in gender binary terms. For men, the risk is enacted as de-masculinisation, or in some cases, overt feminisation (via shrinking testicles, decreased sperm production and the growth of breast tissue [Drug and Alcohol Services South Australia, Citation2017]). Meanwhile, women consumers risk masculinisation (increased facial hair, a deeper voice, a disrupted menstrual cycle and decreased breast size [Drug and Alcohol Services South Australia, Citation2017; see also Australian Government Department of Defence, Citation2019]).

Thinking with Butler (Citation1999) allows us to see these enactments of PIEDs as performing a politics of the natural sexed body: in these materials, sex is stabilised as predictable, self-evident and binary in nature. Co-constituted with this enactment of sex, the ‘healthy’ body emerges as unambiguously hormonally and physically sexed in binary terms, and any change to this is presented as undesirable and abnormal (for a challenge to this enactment of PIED effects, see Henne & Livingstone, Citation2020). In enacting PIEDs as having the capacity to interrupt the natural, unambiguously sexed body, these texts expose a contemporary anxiety that gender and sex are not the stable basis on which social systems have come to be organised (Butler, Citation1999).

To conclude this section, we consider the Australian Government Department of Defence booklet (2019), which usefully demonstrates the contradictory values operating around the aspiration of improvement or enhancement. As noted above, this article proposes that this contradiction is a distinct challenge for health promotion materials about PIEDs, which are governed by a logic specific to health promotion as a mode existence (Latour, Citation2013): that the healthy individual should always be optimising. Titled ‘Performance and image enhancing drugs and supplements: Defence mental health & wellbeing’, the booklet begins by citing a World Health Organization definition:

‘Mental health and wellbeing is [sic] the state in which the individual realises his or her own abilities, can cope with normal stress of life, can work productively and is able to make a contribution to his or her community’. (WHO)

Defence’s vision is that our people – military and public servants – experience positive mental health and wellbeing. They are Fit to Fight – Fit to Work – Fit for Life.

After demonstrating the alignment between the enhancement aims of health promotion and PIED consumption, however, the final page of the booklet states that the Australian Defence Force (ADF) has a ‘zero tolerance policy on the use of illicit drugs’ and that ‘any member found to be using illicit drugs will be required to ‘show cause’ why they should be permitted to remain in the ADF’. This booklet is one of the clearest examples of the paradox between health promotion as a mode of existence and the logic of PIED consumption, highlighting the specific discursive work required to distinguish between appropriate and inappropriate forms of physical and mental optimisation. We propose that one way this is enacted is through a complex gendering of PIEDs and the PIED consumer through ideas of health.

The adolescent male as co-constituted with unhealthy enhancement

Another group of consumers attended to in the health promotion materials is adolescent boys. This section explores the ways in which the adolescent boy figures in the materials in keeping with the commitments and logics of health promotion as a mode of existence (Latour, Citation2013). Farrugia and Fraser (Citation2017) consider adolescence in their study of Australian drug education resources. They observe that young people have been historically constituted as intrinsically irrational, ‘not-developed, and not-socialised, requiring all-knowing adults to guide them on their life path into adulthood’ (Farrugia & Fraser, Citation2017, p. 590). Similar enactments of adolescence appear throughout the Australian PIEDs health promotion materials analysed here. As we will see, the adolescent boy is constituted as especially vulnerable to peer pressure and insecurity about his physical appearance, and therefore to consuming and ‘abusing’ PIEDs.

The Good Sports web page on performance-enhancing drugs provides a useful example of how themes of adolescence, sports and drug abuse are tied together. Good Sports describes itself as ‘a free Australia-wide programme building stronger community sporting clubs’. Sport emerges here as an activity through which healthy moral values are imparted to young people. At the top of its web page, entitled ‘What you need to know about performance enhancing drugs’, sits an image of a young man (). Stood in front of a classroom blackboard, his arms are folded across his chest and his eyes are downcast. Overall, the image invokes working class aesthetics, and the figure’s stance suggests vulnerability. Drawn in white chalk behind the young man are two oversized, muscular, flexing arms, visually suggesting the elements this young man desires and imagines himself to be lacking. The blackboard implies that the downcast male figure is school-aged, and the use of chalk suggests the ephemerality and artificiality of self-image. The chosen image is curious because the man appears neither adolescent nor particularly ‘sporty’ although the hoodie he is wearing, with its association with boxing as well as generic working-class culture, could be interpreted in this way. This image suggests the complex navigations health promotion must make to deal with the enhancement elements of PIEDs. In her review of medical and psychological literature about steroids, Keane (Citation2005) identifies the connection between youth, sport and steroid use, arguing that it ‘challenges dominant images of young illicit drug users as alienated from school life and unconcerned with health and fitness’ (p. 194). This might suggest the reason for this odd image in that depicting seemingly healthy young men playing group sport, a known context for PIED consumption, would be too incongruous with stereotypical representations of illicit drug use, and potentially aspirational (see also Flacks, Citation2021). Such depictions could challenge, that is, the idea that PIED consumption is unequivocally negative or that it inevitably causes harm.

Figure 3. Image of a young man (Good Sports, accessed, Citation2021).

The Good Sports web page also states that PIED use ‘is not just restricted to elite sport’ but is also found in community sport. It continues:

Much of this more localised use has to do with image-enhancement – a recent study of PIEDs [sic] use among adolescent boys found that this group felt particular pressure to gain muscle size in order to bolster their physical appearance and self-worth among peers. This links to additional data […] that suggests [sic] adolescent boys who already take supplements (like vitamins, protein powder and sports drinks) were significantly more likely to be dissatisfied with their muscularity, and also more lenient towards doping in sport.

Good Sports is funded by the Australian Government Department of Health through the Alcohol and Drug Foundation, and is an expressly health promotion-based intervention programme. Looking again at the mode of existence of health promotion through web functionality, links are important to consider. From the web page about PIEDs, the reader can click through to read about the Good Sports programme overall. This web page describes the organisation’s aim as providing ‘preventative health through good sports’ and explains that the Good Sports programme:

is implemented voluntarily through community sporting clubs; helping clubs to promote healthier, safer and more family-friendly environments. [Good Sports] has been helping community sporting clubs to control the use of alcohol and to promote healthy behaviours – such as healthy eating and smoke free environments – for nearly two decades.

While the figure of the adolescent boy saturates the dataset analysed here, adolescents do not comprise the largest demographic of PIED consumers. The Alcohol and Drug Foundation’s factsheet on anabolic steroids (2020) itself cites statistics from the Australian Needle Syringe Program Survey National Data Report 2014-2018 (Heard et al., Citation2019), finding that the ‘majority of people who use anabolic steroids for non-medical purposes [… are] typically in their mid to late 30s’ (Alcohol and Drug Foundation, Citation2020, p. 1). Given this, a question arises: why does health promotion about PIEDs so strongly constitute its audience, and key object of concern, as sport-loving adolescent boys? As discussed, health promotion as a mode of existence (Latour, Citation2013) posits a rational, risk-managing subject, and rationality and providential personal responsibility as the basis of validity and truth. Most importantly, in being young, the adolescent boy embodies the potential of prevention – a stated aim of health promotion – via the promise of early intervention. Enacted in these materials as ‘deviating from and threatening to dominant neo-liberal values of rationality, autonomy and health’ (Farrugia & Fraser, Citation2017, p. 592), the adolescent boy is constituted as the proper site of guidance and improvement as he matures. It is against the adolescent boy that health promotion articulates (highly onerous) expectations of the healthy, rational, masculine subject: that he continually improves and betters himself, aspires through (moderate, non-obsessive) attention to diet and exercise to embody ‘good health’, and self-reflexively monitors his behaviour or consumption against veering into ‘problematic’ or ‘addictive’ territory. Thus, health promotion’s particular mode of existence enacts a reality both highly demanding and at odds with research on PIED consumption patterns.

Conclusion

In examining Australian health promotion materials about PIEDs using the theoretical insights of Butler (Citation1999), Law (Citation2004) and Latour (Citation2013), we identified a key convention in health promotion as a mode of existence: the emphasis on individual enhancement as a component of health. We argued that, through concepts of the natural body and the use of the figure of the vulnerable and irrational adolescent boy in mobilising the promise of prevention, health promotion invokes the same reflex to do better and get better that is present in men’s accounts of PIED consumption. As we have noted, there is an observable tension here between health promotion’s avowed interest in improvement and optimisation and its failure to recognise the relevance of PIED-related enhancement. This tension works, we have argued, to moralise (otherwise arbitrary) discursive and political boundaries of consumption, enacting PIED consumers as vulnerable, insecure, emasculated subjects whose drive to enhance and optimise is not healthy but pathological (Keane, Citation2005; Moore et al., Citation2020).

As others have argued (e.g. Fraser et al., Citation2020; Latham et al., Citation2019), men who consume PIEDs can be understood not as damaged and vulnerable aberrant subjects, but as rational and self-reflexive managers of their health and wellbeing, carefully and often expertly navigating risks. This reality is obscured through the discursive processes analysed in this article, which constitute any consumption of drugs as necessarily harmful, and invoke a complex articulation of risk in relation to a vain, unnatural, artificial and feminised masculinity. Health promotion’s failure to resolve this contradiction – instead offering ‘just say no’ as the healthy approach to illicit drug consumption – leaves individuals with a significant paradox to navigate. Indeed, these findings suggest reasons why some PIED consumers view health promotion materials as unreliable and lacking in credibility (Maycock & Howat, Citation2005). Notably, as Fraser et al. (Citation2020) have observed, some men who consume PIEDs can be characterised as ‘connoisseurs’ (Stengers, Citation2018) in that, in keeping with health promotion’s injunction to rationality and personal efficacy, they develop sophisticated knowledge about the drugs they consume, and strongly desire access to more credible and balanced information about PIED-related risks and how to manage them.

This article has queried the insecure, irrational, unstable masculinities constituted through the felicity conditions (Latour, Citation2013) of PIED-related health promotion. Missing from health promotion materials about PIEDs is an acknowledgement of how exceedingly normative enhancement practices are in contemporary society (Latham et al., Citation2019), and how these practices can be understood to constitute a central dimension of contemporary enactments of health and masculinity (Tanner et al., Citation2013). In constituting drugs and risk in this way, the health promotion materials simultaneously expose and reproduce a distinctly gendered anxiety: that normative masculinity – through its association with the contemporary project of healthism – might be in the process of deteriorating such that it resembles a traditionally ‘feminine’ and therefore denigrated relation to bodily care and management.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Date accessed is noted for resources that do not state the year published.

2 The emergency services phone number in Australia.

References

- Alcohol and Drug Foundation. (2020). Anabolic steroids. https://adf.org.au/drug-facts/steroids/.

- Andreasson, J., & Johansson, T. (2016). Online doping. The new self-help culture of ethnopharmacology. Sport in Society, 19(7), 957–972. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2015.1096246

- Annandale, E., & Clark, J. (1996). What is gender? Feminist theory and the sociology of human reproduction. Sociology of Health & Illness, 18(1), 17–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.ep10934409

- Australian Criminal Intelligence Commission. (2018). Illicit drug data report 2016-17. Commonwealth of Australia. https://www.acic.gov.au/publications/illicit-drug-data-report/illicit-drug-data-report-2016-17.

- Australian Criminal Intelligence Commission. (2021). Illicit drug data report 2019-20. Commonwealth of Australia. https://www.acic.gov.au/publications/illicit-drug-data-report/illicit-drug-data-report-2019-20.

- Australian Government Department of Defence. (2019). Performance and image enhancing drugs and supplements: Defence mental health & wellbeing. https://www.defence.gov.au/adf-members-families/health-well-being.

- Australian Government Department of Health. (2017). Performance and image-enhancing drugs: What you need to know. https://positivechoices.org.au/documents/XxkC1msC8z/performance-and-image-enhancing-drugs-detailed-resource-for-parentsteachers/.

- Basaria, S. (2018). Use of performance-enhancing (and image-enhancing) drugs: A growing problem in need of a solution. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology, 464, 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mce.2018.02.004

- The Better Health Channel. (2020). Anabolic steroids. https://www.betterhealth.vic.gov.au/health/healthyliving/steroids.

- Butler, J. (1999). Gender trouble: Feminism and the subversion of identity (2nd ed.). Routledge.

- Connell, R. (1995). Masculinities. Allen & Unwin.

- Conrad, P., & Potter, D. (2004). Human growth hormone and the temptations of biomedical enhancement. Sociology of Health & Illness, 26(2), 184–215. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9566.2004.00386.x

- De Beauvoir, S. (1949) The second sex. Vintage Books.

- Derrida, J. (1993). The rhetoric of drugs (first published 1989). Differences: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies, 5(1), 1–25.

- Drug and Alcohol Services South Australia. (2017). What are steroids? What + are + steroids+(00498) + 2017.pdf (sahealth.sa.gov.au).

- Farrugia, A., & Fraser, S. (2017). Young brains at risk: Co-constituting youth and addiction in neuroscience-informed Australian drug education. Biosocieties, 12(4), 588–610. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41292-017-0047-2

- Filiault, S. M., & Drummond, M. J. N. (2010). “Muscular, but not ‘roided out’”: Gay male athletes and performance-enhancing substances. International Journal of Men's Health, 9(1), 62–81. https://doi.org/10.3149/jmh.0901.62

- Fine, C. (2017). Testosterone rex: Myths of sex, science, and society. Norton & Company.

- Flacks, S. (2021). Law, drugs and the politics of childhood: From protection to punishment. Routledge.

- Fleming, M. L., & Parker, E. (2020). Health promotion: Principles and practice in the Australian context (3rd ed.). Routledge.

- Fomiatti, R., Latham, J. R., Fraser, S., Moore, D., Seear, K., & Aitken, C. (2019). A ‘messenger of sex’? Making testosterone matter in motivations for anabolic-androgenic steroid injecting. Health Sociology Review, 28(3), 323–338. https://doi.org/10.1080/14461242.2019.1678398

- Fomiatti, R., Lenton, E., Latham, J. R., Fraser, S., Moore, D., Seear, K., & Aitken, C. (2020). Maintaining the healthy body: Blood management and hepatitis C prevention among men who inject performance and image-enhancing drugs. International Journal of Drug Policy, 75, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2019.10.016

- Francesconi, S. (2011). Images and writing in tourist brochures. Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change, 9(4), 341–356. https://doi.org/10.1080/14766825.2011.634914

- Fraser, S., & Ekendahl, M. (2018). Getting better: The politics of comparison in addiction treatment and research. Contemporary Drug Problems, 45(2), 87–106. https://doi.org/10.1177/0091450917748163

- Fraser, S., Fomiatti, R., Moore, D., Seear, K., & Aitken, C. (2020). Is another relationship possible? Connoisseurship and the doctor-patient relationship for men who consume performance and image-enhancing drugs. Social Science & Medicine, 246, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112720

- Fraser, S., Moore, D., & Keane, H. (2014). Habits: Remaking addiction. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Fraser, S., & Seear, K. (2011). Making disease, making citizens: The politics of hepatitis C. Ashgate Publishing Ltd.

- Fraser, S., & valentine, k. (2008). Substance and substitution: Methadone subjects in liberal societies. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Good Sports. (2021). What you need to know about performance enhancing drugs. https://goodsports.com.au/drugs/drugs-pieds/.

- Heard, S., Iversen, J., & Geddes, L. (2019). Australian NSP survey national data report 2014-2018. Kirby Institute, UNSW Sydney.

- Henne, K., & Livingstone, B. (2020). More than unnatural masculinity: Gendered and queer perspectives on human enhancement drugs. In K. Van de Ven, K. J. D. Mulrooney, & J. McVeigh (Eds.), Human enhancement drugs (pp. 13–26). Routledge.

- Keane, H. (2002). What’s wrong with addiction? Melbourne University Press.

- Keane, H. (2005). Diagnosing the male steroid user: Drug use, body image and disordered masculinity. Health: An Interdisciplinary Journal for the Social Study of Health, Illness and Medicine, 9(2), 189–208. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363459305050585

- Kutscher, E. C., Lund, B. C., & Perry, P. J. (2002). Anabolic steroids: A review for the clinician. Sports Medicine, 32(5), 285–296. https://doi.org/10.2165/00007256-200232050-00001

- Latham, J. R., Fraser, S., Fomiatti, R., Moore, D., Seear, K., & Aitken, C. (2019). Men’s performance and image-enhancing drug use as self-transformation: Working out in makeover culture. Australian Feminist Studies, 34(100), 149–164. https://doi.org/10.1080/08164649.2019.1644952

- Latour, B. (2013) An inquiry into modes of existence: An anthropology of the moderns. Harvard University Press.

- Law, J. (2004). After method: Mess in social science research. Routledge.

- Lupton, D. (1995) The imperative of public health: Public health and the regulated body. SAGE Publications.

- Macdonald, G., & Bunton, R. (1992). Health promotion: Disciplinary developments. In R. Bunton, & G. Macdonald (Eds.), Health promotion: Disciplines, diversity, and developments ((2nd ed, pp. 9–29.

- Maycock, B., & Howat, P. (2005). The barriers to illegal anabolic steroid use. Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy, 12(4), 317–325. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687630500103622

- McVeigh, J., & Begley, E. (2017). Anabolic steroids in the UK: An increasing issue for public health. Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy, 24(3), 278–285. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687637.2016.1245713

- Mitra, A., & Cohen, E. (1999). Analysing the web: Directions and challenges. In S. Jones (Ed.), Doing internet research: Critical issues and methods for examining the net (179–202). SAGE Publications.

- Monaghan, L. (2001). Looking good, feeling good: The embodied pleasures of vibrant physicality. Sociology of Health & Illness, 23(3), 330–356. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.00255

- Moore, D., & Fraser, S. (2006). Putting at risk what we know: Reflecting on the drug-using subject in harm reduction and its political implications. Social Science & Medicine, 62(12), 3035–3047. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.11.067

- Moore, D., Hart, A., Fraser, S., & Seear, K. (2020). Masculinities, practices and meanings: A critical analysis of recent literature on the use of performance and image-enhancing drugs among men. Health: An Interdisciplinary Journal for the Social Study of Health, Illness and Medicine, 24(6), 719–736. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363459319838595

- Moore, S. E. (2010) Is the healthy body gendered? Toward a feminist critique of the new paradigm of health. Body & Society 16(2): 95–118. https://doi.org/10.1177/1357034X10364765

- Onakomaiya, M., & Henderson, L. (2016). Mad men, women and steroid cocktails: A review of the impact of sex and other factors on anabolic androgenic steroids effects on affective behaviors. Psychopharmacology, 233(4), 549–569. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-015-4193-6

- Petersen, A., & Lupton, D. (1996). The new public health: Health and self in the age of risk. SAGE Publications.

- Seale, C. (1999). Quality in qualitative research. Qualitative Inquiry, 5(4), 465–478.

- Seddon, T., Williams, L., & Ralphs, R. (2012). Tough choices: Risk, security and the criminalisation of drug policy. Oxford University Press.

- Sedgwick, E. (1993) Tendencies. Duke University Press.

- Seear, K., Fraser, S., Moore, D., & Murphy, D. (2015). Understanding and responding to anabolic steroid injecting and hepatitis C risk in Australia: A research agenda. Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy, 22(5), 449–455. https://doi.org/10.3109/09687637.2015.1061975

- Seear, K., Moore, D., Fraser, S., Fomiatti, R., & Aitken, C. (2020). Consumption in contrast: The politics of comparison in healthcare practitioners’ accounts of men who inject performance and image-enhancing drugs. International Journal of Drug Policy, 85, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2020.102883

- Stengers, I. (2018) Another science is possible: A manifesto for slow science. Polity Press.

- Tanner, C., Maher, J., & Fraser, S. (2013). Vanity: 21st century selves. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Van de Ven, K., Maher, L., Wand, H., Memedovic, S., Jackson, E., & Iversen, J. (2018). Health risk and health seeking behaviours among people who inject performance and image enhancing drugs who access needle syringe programs in Australia. Drug and Alcohol Review, 37(7), 837–846. https://doi.org/10.1111/dar.12831

- Vitellone, N. (2017). Social science of the syringe: A sociology of injecting drug use. Routledge.

- Winter, R., Fraser, S., Booker, N., & Treloar, C. (2013). Authenticity and diversity: Enhancing Australian hepatitis C prevention messages. Contemporary Drug Problems, 40(4), 505–529. https://doi.org/10.1177/009145091304000404

- World Health Organization. (Accessed 2021). What is health promotion? https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/health-promotion.

- Your Room, Alcohol and Drug Information Service. (2018). Anabolic steroids. https://yourroom.health.nsw.gov.au/a-z-of-drugs/Pages/anabolic-steroids.aspx.

- Youth Solutions. (Accessed 2021). Performance and image enhancing drugs (PIEDs). https://youthsolutions.com.au/drug-information/performance-and-image-enhancing-drugs-pieds/.

- Zahnow, R., McVeigh, J., Bates, G., Hope, V., Kean, J., Campbell, J., et al. (2018). Identifying a typology of men who use anabolic androgenic steroids (AAS). International Journal of Drug Policy, 55, 105–112. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2018.02.022