ABSTRAT

Deaf and hard-of-hearing students were greatly affected by the COVID-19 pandemic due to communication barriers, social distancing, and difficulties with distance education. Numerous researchers have investigated the experiences of such students during the COVID-19 pandemic, but generally addressed single aspects of their lives; hence, there is a need to investigate the broader impact of the pandemic on deaf students. Notably, very few local or international studies on the experiences of deaf students in Georgia are available. To address this gap, I employed qualitative methods to frame the accounts and memories of deaf students during the COVID-19 pandemic. The data for this study were gathered through semi-structured interviews with 12 such students attending specialised boarding schools for the deaf in Georgia. Four main themes were identified: the impact of COVID-19 on their moods, the substantial increase in screen time due to distance learning and screen-based social interactions, the dual nature of COVID-19 as a catalyst for increased interactions with family members, and its role in prompting contemplations of the future. This article describes and explores the lived experiences of deaf students and contributes to the collective memory of affected communities by highlighting the value of individual voices, particularly in a small country that is often unknown or overlooked.

Introduction

We tend to consider only the impact of pandemics on health and health-related issues. However, the outbreak of COVID-19 affected all aspects of life and had multiple global consequences. Many countries underwent significant social changes as governments and organisations took drastic measures and adopted rapid response strategies to prevent the disease’s transmission and consequences. Although lockdowns and curfews were introduced to safeguard society, they caused numerous challenges, leading to disparities, inequalities, and segregation for some groups and communities. For instance, educational disparities encompass limitations of accessibility to and affordability of technology and the Internet for effective distance education among students from lower economic backgrounds or living in rural areas (Allen et al., Citation2020; Basilaia & Kvavadze, Citation2020), inappropriately designed learning materials for students with special educational needs (Tigwell et al., Citation2020) and insufficient protection of the interests of students under social support and special care (Loima, Citation2020). Other major disparities resulted in severe economic consequences for women, immigrants, individuals from lower socioeconomic backgrounds, and people of colour who experienced disproportionate layoffs compared to local/native upper-class populations. COVID-19 and its associated restrictions exacerbated social disparities for ethnic, linguistic, and/or religious minorities who maintained their integrity through meetings and cultural events, which were disrupted by lockdown measures (Mahmood et al., Citation2021).

The COVID-19 pandemic profoundly affected deaf communities, leading to an information vacuum and poor communication during the pandemic (Singh et al., Citation2021). For instance, in Georgia, due to the close collaboration of the National Deaf Union, healthcare systems, and national broadcasting companies, all conferences were supported by national sign language interpreters to ensure accurate, up-to-date information for deaf individuals. However, in the early stages of the pandemic, information was primarily disseminated through social media or individuals, leading to inconsistent use of new COVID-19-related signs. Despite assertions that the varying signs for the term coronavirus were not a significant concern regarding information provision (Murray, Citation2020), the inconsistency and use of multiple signs initially caused confusion, uncertainty and fear among deaf individuals (Castro et al., Citation2020). Indisputably, young deaf students suffered greatly; they not only had to contend with the usual obstacles but also grappled with the new and inappropriate educational format of remote education (Aljedaani et al., Citation2022).

Scientific research has rarely focused on the experiences of deaf individuals during pandemics or crises (Tomasuolo et al., Citation2021). In general, during previous pandemics, information dissemination lacked discretion, failed to convey comprehensive understanding in real-time, also neglected narrative accounts and the issue of reliability (Erll, Citation2020). During the COVID-19 pandemic, the internet and social media played a crucial role in facilitating the rapid dissemination of information, ensuring real-time awareness and generating multiple narratives.

The aim of this study was to give a voice to young deaf students in Georgia and to learn about their lived experiences during the COVID-19 lockdowns. The importance of this study stems primarily from the dearth of qualitative studies conducted in Georgia that presented the voices and incorporated the perspectives of young deaf students or addressed the general need to create a pool of knowledge regarding their traumatic experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. According to Mantzikos and Lappa (Citation2020), it is imperative to examine the far-reaching impact of the pandemic on the lives of deaf students rather than focusing on separate variables, such as face masks, technology, and distance learning. Using qualitative approaches, researchers can frame personal accounts and build upon memories not merely as recollections of experiences, but as means to explore how the experiences were lived.

This exploratory study has an overarching hypothesis that students residing in specialised boarding schools for the deaf would encounter significant difficulties due to school closures and returns to their homes. This assumption stemmed primarily from the fact that most deaf students are born into hearing families and encounter challenges in effectively communicating with family members (Jackson et al., Citation2008; Weaver & Starner, Citation2011). The framework of this study assumed that this lack of effective communication with hearing family members would result in increased boredom, stress, and anxiety, leading deaf students to turn to social media for social support and relief.

Face-to-face interviews and personal narratives proved extremely valuable for providing qualitative data on the personal experiences of deaf students in Georgia during the COVID-19 pandemic. The memories of these personal experiences may help deaf children, their successors, and affected communities reflect on or face other inevitable challenges. History is nothing more than a constructed collective memory (McNeill, Citation1985) but one based on shared, deeply felt experience (Erll, Citation2020), where individual voices add value, especially those of the marginalised, whom the dominant society tends not to hear or see.

Deaf learners encountering the COVID-19 pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic and its associated restrictions psychologically affected more people than the infection itself (Ornell et al., Citation2020). The restrictive policies resulted in numerous indirect consequences, such as reduced non-urgent healthcare, increased poverty, distance education, diminished social relationships, and decreased physical activities (Chanchlani et al., Citation2020). These disruptions often led to sleep deprivation (Altena et al., Citation2020), an increase in sedentary behaviours (Al Majali & Alghazo, Citation2021), mood disturbances, and a reduction in overall quality of life (Barone Gibbs et al., Citation2021). Pandemics have a profound impact on schoolchildren. The school closures not only led to unparalleled global and domestic inequalities in education (Azevedo et al., Citation2021) but also resulted in learning losses across all age groups and subject areas (Engzell et al., Citation2021; Maldonado & De Witte, Citation2021).

COVID-19 and its associated restrictions had pronounced and multifaceted effects on deaf students. Deaf students have diverse learning needs (Guardino & Cannon, Citation2016) that required attention during the COVID-19 pandemic to ensure that their educational needs were effectively met. For example, students at the Texas Woman’s University Future Classroom Lab (TWUFCL) developed a YouTube channel as part of their coursework to provide instructional videos for deaf students, their teachers, and their parents, which facilitated improved communication and connection in the comfort of their homes (Smith & Colton, Citation2020). The importance of self-advocacy and community support for deaf students became extremely important during the pandemic (Swanwick et al., Citation2020). For example, in Italy, deaf communities took the initiative to develop distance-learning modules and materials during the initial phase of COVID-19. Moreover, the public protest of a single deaf student about the lack of a teaching assistant during an online class promoted nationwide communication support (Tomasuolo et al., Citation2021).

Technology-related issues, such as slow internet connections that caused disjoined signs, significantly undermined the communication fluency of deaf students in many countries (Aljedaani et al., Citation2022; Alshawabkeh et al., Citation2021; Lazzari & Baroni, Citation2020; Tigwell et al., Citation2020). A lack of online collaboration and communication with teachers and peers was reported by older (Aljedaani et al., Citation2022) and younger (Mantzikos & Lappa, Citation2020) deaf students. The lack of immediate feedback during screen communication affected the learning experience (Alshawabkeh et al., Citation2021). Furthermore, communication challenges had an impact on students’ performance and instructors’ efficacy (Aljedaani et al., Citation2022). Instructors reported that the absence of visual cues prevented them from delivering appropriate instruction (Alsadoon & Turkestani, Citation2020). It became impossible to interpret on-screen silences (Nkoala, Citation2022), which could indicate either understanding or misunderstanding in classrooms.

Deaf students (Tigwell et al., Citation2020) and their parents (Kritzer & Smith, Citation2020) reported poor pedagogical practices for delivering online information, including inappropriate course designs, materials, and delivery methods. Teachers attributed this poor pedagogical performance to a lack of internet infrastructure, low competence in information and communication (ICT) technology, and the absence of training in online teaching immediately after the outbreak of COVID-19 (Ashraf et al., Citation2021).

Deaf students in the United Arab Emirates claimed that the course content was overwhelming (in volume) and inappropriate (in design) (Alshawabkeh et al., Citation2021). Reflecting on their own experiences as deaf students, Karunaratne and Karunaratne (Citation2020) reported reading extensively to keep up with and mitigate the effects of reduced communication quality.

Alshawabkeh et al. (Citation2021) found that deaf students became frustrated with assessment methods during distance learning that failed to consider the new learning reality, and the authors believed that the gap between deaf and hearing students widened greatly due to the unfairness of assessment systems.

Unlike hearing students, for whom distance learning provided temporary breaks from the exhausting rhythm of school, deaf students found school closures difficult. For deaf students, specialised schools surpass mere educational purposes by offering vital spaces for belonging, communication, and socialisation (Angelides & Aravi, Citation2006; Haakma et al., Citation2017). Distance learning was associated not only with unsatisfactory educational practices for deaf students but also with emotionally stressful experiences (Aljedaani et al., Citation2022). This assertion was echoed by counsellors at the National Technical Institute for the Deaf, who revealed that deaf students experienced social and emotional changes, loneliness, isolation, insecurity, feelings of inadequacy, a decreased sense of belonging, and loss of supportive communication during the COVID-19 pandemic (Lynn et al., Citation2020).

The adverse impacts of distance education on deaf students extend beyond short-term consequences. Online education during the pandemic had the potential to increase the language gap for these children (Whitney & Whitney, Citation2022), which, in turn, increased the risks of language deprivation and sociocultural exclusion, with implications far beyond the loss of two academic years of in-person instruction (Swanwick et al., Citation2020).

However, it is important to note that online education had some advantages, with certain students expressing happiness at having this opportunity to enhance their computer skills. These students believed that acquiring these skills would prove beneficial in their future careers (Alshawabkeh et al., Citation2021).

The Georgian context

Georgia took proactive measures against COVID-19, even before its official declaration as a pandemic. On 18 March 2020, all borders were closed, and an emergency was declared, followed by a general quarantine on 31 March (Kvirkvelia & Tsitsagi, Citation2021). Consequently, on 8 March 2020, following the spring holidays, normal school classes did not resume; instead, remote online learning was launched for all 2,081 public and 221 private schools (Ministry of Education and Science of Georgia, Citation2020) and continued until the end of the 2020 academic year. In 2021, classes reopened in schools or remained online depending on the local epidemic situation and the coordinating committee’s decision.

The Ministry of Education and Science promptly launched numerous platforms, activities, and resources to ensure uninterrupted, high-quality educational processes for children, teachers, and parents (EFA Education Coalition, Citation2020). Georgia received €20 million of European Union (EU) funding during the COVID-19 pandemic, of which €11.3 million was distributed as grants to civil organisations to support local schools with distance learning (Delegation of the European Union to Georgia, Citation2020). To ensure widespread schooling for the population, the collaborative TV School project was launched in partnership with the Georgian Public Broadcasting Service. This project delivered 15–20-minute televised lessons across all subjects and grade levels. The needs of deaf students were considered, and all lessons had sign language subtitles.

The deaf and hard-of-hearing population is heterogeneous (Fuentes et al., Citation2019). The degree, type, and age of the hearing loss, the degree of residual hearing, the hearing status of parents, and the use of cochlear implants and hearing aids vary widely. Consequently, educational practices for deaf students can also vary significantly. Georgia offers three different educational options: specialised, integrated, and inclusive (Abulashvili et al., Citation2021).

Special education schools offer tailored materials, activities, and teaching approaches that are delivered by appropriately trained teachers (Pachkoria et al., Citation2012). In these schools, deaf students can use sign language to improve communication and socialisation with their peers. In the integrated model, deaf pupils are enrolled in mainstream schools but take some lessons in specially designed classes, often called resource classrooms, under the guidance of specially trained teachers (Pachkoria et al., Citation2012). Inclusive education involves the full integration of students into mainstream schools and classrooms with multidisciplinary teams, including parents, developing individual learning plans according to the needs and abilities of deaf students.

Methodology

Population and sample

The sample for this research comprised deaf students enrolled in specialised boarding schools for the deaf in 2020–2022. A total of 12 students were selected for interviews based on various factors, such as parental consent and their willingness to participate. Of the selected students, 8 (67%) were female, and 4 (33%) were male. Their average age was 16 years.

Of the 12 participants, 11 were prelingually and profoundly deaf (80 dBHL or greater) and used sign language as their primary language of instruction and communication. None of them had cochlear implants or used hearing aids. One participant had moderate hearing loss, used a hearing aid, and communicated using both signed and spoken language. Of the participants, 9 (75%) came from hearing families, while 3 (25%) had either parents or siblings who were deaf or hard of hearing. The 12 individuals accounted for 31.4% of the upper secondary student cohort in selected specialised boarding schools for the deaf.

Tools and procedures

The Research Ethics Board of Åbo Akademi gave ethical approval for this study prior to data collection. The Ministry of Education and Science of Georgia also granted official permission to conduct interviews with students. The logistical and operational aspects of the interviews were decided through consultations with the school principals and teachers. Before the interviews, a series of meetings were organised with the schoolteachers to ensure the clarity and accuracy of the interview questions. The discussion regarding the inclusion of boredom in the questions was decided by consensus due to its relevance in the context of prolonged COVID-19 measures, such as curfews and restricted gatherings in Georgia. The researcher´s sign language proficiency is moderate, yet crucial for interpersonal communication. The researcher needs to be familiar with culturally specific and/or universal behaviours among the communities of his/her interest (McDonald, Citation2000). Establishing social interaction with participants using sign language before, during, and after the interviews was critical for building trust between the researcher and participants. However, to ensure the quality of the communication and translations, a sign language teacher, who was also a certified hearing Georgian Sign Language (GSL) interpreter, supported the interviews. All interviews were recorded over nine working days in December 2022. Only semi-structured interview questions were used for data collection. Interview questions were developed based on the literature regarding the impact of COVID-19 on various populations, including deaf individuals (Aljedaani et al., Citation2022; Lynn et al., Citation2020; Makhashvili et al., Citation2020). The questions were designed to provide a general framework for the interviews while allowing participants the freedom to express their thoughts without interruption. This freedom resulted in textual data that extended beyond the immediate scope of the research topics. Nevertheless, we considered it important for the participants to tell their stories.

The questions were designed to be appropriate for deaf students in a specific cultural context, as follows:

How did COVID-19 affect you?

How did you adapt to the new reality?

How has COVID-19 changed the way you think?

How did you spend your free time during the pandemic?

How did you deal with stress and boredom?

Each interview lasted approximately 30–45 min and was held on school premises.

Analysis

Thematic analysis was used to analyse the study data. Many researchers do not view thematic analysis as a standalone method, but rather as a set of generic skills that can be used across a range of different methods (Guest et al., Citation2012; Holloway & Todres, Citation2003). However, others claim that thematic analysis is a powerful and completely independent but largely unrecognised method of qualitative data analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2012).

Several important factors promoted the selection of thematic analysis for this study. First, thematic analysis is suitable for identifying common discourse patterns within specific groups of individuals discussing specific topics (Braun & Clarke, Citation2012) and providing insight into the shared meanings and experiences of these groups. Second, a major advantage of thematic analysis is its flexibility, not only in terms of theory but also in terms of research questions, data collection methods, and the generation of meaning (Braun & Clarke, Citation2012). In addition, thematic analysis can be used effectively with small (Cedervall & Åberg, Citation2010) or large (Mooney-Somers et al., Citation2008) heterogeneous or homogeneous samples.

The thematic analysis comprised six stages (Braun & Clarke, Citation2012). The first was familiarisation with the data through repetitive and in-depth reading to identify multiple meanings (Vaismoradi et al., Citation2016). This step was followed by coding, which involved labelling the research-relevant characteristics of the data (Fereday & Muir-Cochrane, Citation2006). During the third, fourth, and fifth phases, the main attention shifted from codes to themes, which were used as descriptors to organise ideas and generate meaning. Finally, the sixth phase consisted of report writing.

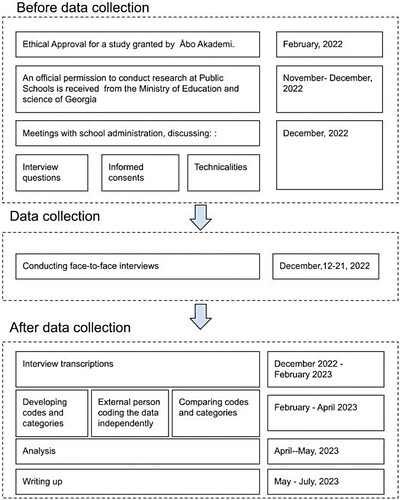

The interview recordings were transcribed immediately after the interviews, as outlined in a data management plan, on which the ethical approval for this study was based. All the interviews were transcribed to text collaboratively with the same interpreter who attended the interviews. Drawing on her 15 years of Sign language teaching, experience as a GSL interpreter, and cultural awareness due to her ties to the deaf community, she provided thoughtful, nuanced interpretations and strategically omitted details (Napier, Citation2004). The resulting textual files underwent multiple revisions before and during the coding process. The analytical approach was inductive (bottom-up), primarily descriptive, and exploratory (Guest et al., Citation2012). The initial coding was performed by the author and reviewed by a fellow researcher using online collaboration software. Disagreements, different ideas, and unclear cases were discussed and addressed. Once the codes were refined, a comprehensive review of the categories preceded the subsequent analysis and write-up. illustrates the entire workflow cycle.

Trustworthiness of the study

Regarding validity and reliability in quantitative research, Lincoln and Guba (Citation1985) reformulated the notion of trustworthiness and developed a revised framework that encompassed credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability. The credibility of a study relies on aligning raw data with the researcher’s interpretation (Polkinghorne, Citation2007). The credibility of this study was ensured by an extensive literature review, the researcher’s sustained and active engagement with the deaf community, collaboration and consultations with professionals, and peer debriefing to externally verify the research process (Foster, Citation2019; Lincoln & Guba, Citation1985). Transferability refers to the extent to which the findings of a study can be generalised. Unlike quantitative studies, the reproducibility of qualitative studies is difficult and epistemologically implausible (Leung, Citation2015). Nevertheless, a comprehensive description of the study context is provided for transparency. Dependability concerns the degree to which another researcher can reach the same or similar conclusions using the same dataset (Leung, Citation2015). This was achieved by describing the research process clearly. Finally, confirmability demonstrates that the researcher’s interpretations are derived from and strongly linked to the data. Once credibility, transferability, and dependability have been achieved, confirmability is established.

Findings

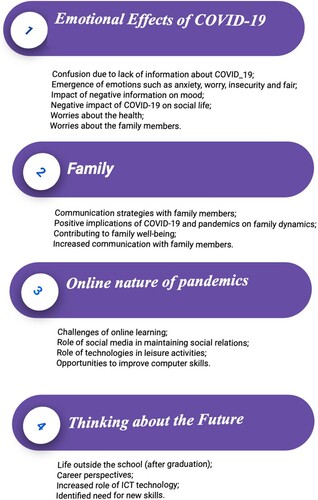

The research findings are arranged into four themes. presents the themes and extracted codes, each of which is described in a separate subsection.

Emotional effects

The participants found the initial stages of the pandemic particularly challenging due to a lack of knowledge and information about COVID-19, accompanied by various emotions, such as anxiety, worry, curiosity, insecurity, and confusion. One participant captured the experience by stating:

At the beginning of the pandemic, there was a sense of quiet waiting. We were silent because we had nothing to say, and the waiting was nerve-racking because we didn’t know what to expect. (F4)

Even though I was not personally feeling low, everyone around us was so desperate that I felt I had no “right” to be happy … The most difficult moments were when the number of deaths was reported. (F10)

We were very worried about not getting infected because we had very young children and grandparents in our families. So I compromised and did not go out, not even during the daytime, when I was allowed to go to the shop or pharmacy. That was very difficult, but thinking I might bring the virus home from outside was even worse. (F2)

Others revealed, “I really needed to do something to forget about the pandemic, so I helped my mother with the housework. That was great” (F1), or “I could not go out and do physical activities; all I could do was follow Facebook” (M9).

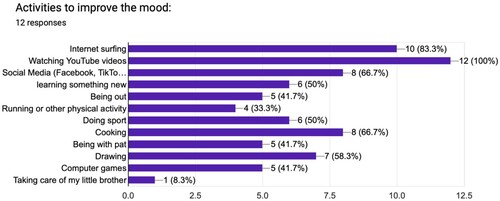

expands on the activities practised by the study participants to improve their moods.

Family

To communicate effectively with parents who could not use sign language, the participants initially used expressive strategies, such as simple pointing or miming, but later employed writing, typing, or even online translation tools. However, they saw such efforts to communicate not as frustrating but as a fun way to achieve greater closeness with family members.

Many students said that it was stressful to be at home during the lockdowns for practical reasons. With two or more generations living together, families in Georgia are typically large, which led to increased foot traffic and noise within households during the pandemic, intensifying stress and anxiety levels, particularly during work and school hours:

My siblings had classes at almost the same time; we all had our own phones to attend classes, but it was difficult to find a quiet corner, particularly with other family members at home all the time, cleaning or cooking. Attending classes online was the hardest part of the day. (F5)

“We were all very worried about the pandemic. My parents were worried about our education, but it was still very positive to be together. (F1)

“My father was very stressed about his job, but we were playing cards in the evenings, and at those times, we did not remember COVID-19 at all”. (F11)

I used to help my mum with the cooking, which gave me a lot of satisfaction because I was doing something good for the whole family and, above all, making my mum happy. When I was not doing classes, I helped my mother with my younger siblings, which meant quite a lot to her. (F7)

“I was helping my father with his job. Sometimes, I was just sitting next to him, but I loved it, and I knew he also enjoyed me being there”. (M6)

“My father trusted me to do some gardening, and knowing this, I did my best to make him proud”. (M12)

Online activities (school and leisure)

Within the frames of this study, none of the interview questions were specifically focused on the challenges of distance learning but rather, explored the general difficulties experienced during the pandemic. However, distance learning was a prominent and extensively discussed theme among the students. Many students highlighted the widespread inappropriateness of online learning due to poor communication, technical problems, and low-quality internet connections or devices. The absence of individual assistance from teachers (a typical element of education for deaf students) was partially mitigated by intensive but informal and irregular communication with teachers through social media or instant messaging.

Additionally, participants widely discussed the online nature of distance learning, both positively and negatively. Deaf students reported using social media for many aspects of their lives, including personal development, hobbies, and formal and informal communication. The merging of education with all these aspects resulted in blurred boundaries between social, educational, and leisure activities. Suddenly, the online space became a platform for all these activities, which led to health concerns among the students regarding the lack of physical activity and the harmful effects of extensive screen time on the eyes: “My mum used to limit my screen time, but during online (learning), that was impossible. I used to spend hours on the phone just for lessons and homework” (F2).

Although ICT is commonly used in traditional face-to-face teaching in Georgia, distance education requires distinct skills and knowledge. Some students viewed this as an opportunity to enhance their computer proficiency, acknowledging the “beneficial side of phones and the internet” as tools for learning rather than mere entertainment.

Thinking about the future

Another theme that has derived from the data concerned the participants’ thoughts and plans. For many participants, school closures served as a simulated experience of their transition to out-of-school life after graduation. Specifically, older participants regarded the pandemic as an eye-opening experience that provided insights into what their future lives might be like forcing them to assess their levels of preparedness for adulthood.

Most of the participants thought about their future education or careers during the pandemic. The significance of ICT skills became increasingly apparent, prompting several participants to recognise the growing demand for technology in today’s world and motivating them to actively seek opportunities to enhance their proficiency in using ICT tools.

Spending more time on social media and YouTube, many participants realised the importance of knowing/improving American sign language (ASL) to access information, which led them to begin learning other sign languages (mostly ASL):

Many videos and resources are available on ASL. Also, if you are very good at it, you can go abroad and learn at universities or colleges there. During the pandemic, I had time to watch many videos and improve my ASL. (F3)

Discussion

In this section, the findings regarding each theme are linked and discussed in relation to relevant existing studies.

The interview data revealed that all participants experienced the impact of COVID-19 on mental health, moods, and emotions (Makhashvili et al., Citation2020). Deaf people were greatly affected because they were already more prone to mental health challenges than their hearing peers (Hindley, Citation2005). This disparity intersected with various other factors, such as limited access to information and reduced social engagement with family members and peers (McElwain & Volling, Citation2005). To alleviate these challenges in Georgia, the Deaf Union offered information support, but the participants in this study found emotional relief mostly within their families by participating in household activities.

Although coping strategies differ by gender and age (Matud, Citation2004; Tamres et al., Citation2002), Makhashvili et al. (Citation2020) found that talking to family and friends was a constant and effective mechanism for reducing stress across numerous populations, together with other activities, such as reading, watching television, or doing household chores. Few study participants mentioned extensive reading as a leisure activity during COVID-19, possibly due to the enforced mandatory reading demands of online education (Alshawabkeh et al., Citation2021; Nkoala, Citation2022). However, they frequently mentioned involvement in family issues or household activities. In general, the COVID-19 pandemic was a double-edged sword for families with deaf or hard-of-hearing members. On the one hand, it posed challenges, but on the other hand, it provided unique opportunities for togetherness. Joint activities encouraged deaf and hearing family members to interact, fostering a deeper understanding of family interactions and the significance of family care and love (Ramadhana et al., Citation2020).

In terms of family dynamics, the participants predominantly discussed their relationships and communication with their fathers. A father’s ability to communicate in sign language can increase the self-esteem of a deaf child (Takala et al., Citation2000). Although it is known that fathers’ involvement is crucial for children’s physical and emotional well-being (Yogman et al., Citation2016), the scientific literature on parents’ roles in bringing up children, including the deaf, still emphasises mothers (Szarkowski & Dirks, Citation2021). Various factors, such as the Georgian social, economic, and cultural context, may influence fathers’ levels of involvement, but unfortunately, to the best of our knowledge, no scientific studies have specifically addressed the role of fathers from a Georgian cultural perspective, apart from one study that explored the representation of family and child-rearing practices in popular folklore proverbs (Rusieshvili & Gözpınar, Citation2014). In that article, mothers were depicted as the most suitable and knowledgeable individuals to raise children. The limited involvement of fathers in childrearing can be attributed to practical factors, such as their work schedules and mothers’ extensive orchestration of family affairs. However, deaf students clearly expressed joy at having opportunities to communicate and spend time with their fathers during the pandemic.

Another dominant topic of discussion was the digital dimension of the pandemic and its profound impact on the educational and social experiences of deaf students. The study participants reported significant distractions while engaging in online education. Deaf students commonly practise visual dispersion, which refers to managing multiple visual inputs simultaneously, but this can result in the loss of important information (Cavender et al., Citation2009; Kushalnagar, Citation2019) and an increased cognitive load (Cavender et al., Citation2009; Vertegaal et al., Citation2002), causing stress, anxiety, and disruption (Lazzari & Baroni, Citation2020). Even before the pandemic, several assistive technologies were introduced to reduce the challenges faced by deaf individuals when participating in video conferences or screen-based communication. However, such technologies mostly focus on automating sign language interpretation and cannot accurately interpret facial and non-manual expressions; consequently, the equal and active participation of signing individuals has not yet been realised (Rui Xia Ang et al., Citation2022). Unfortunately, Georgian students are particularly disadvantaged in terms of using assistive technologies, which usually employ ASL.

Online platforms as learning environments for deaf students require careful planning. Unfortunately, in many instances, essential factors, such as sound quality, lighting, student placement, and visual displays on screens, are ignored or inadequate, with devastating consequences for the performance of deaf students. In addition to technicalities, technology-based education culturally excludes deaf students from pedagogical practices (Ramsey, Citation2004). Unfortunately, most communication platforms, including those used during the pandemic, are designed for the hearing population and do not account for the needs and cultural norms of deaf people (Gugenheimer et al., Citation2017). For example, it is common practice to attract the attention of such people by flashing a light or waving a hand. Flashing has never been a function of any platform, while a raised hand, although physically possible on some platforms, is often missed during online activities, particularly those involving large audiences.

Apart from education, the study participants used social media extensively for personal purposes, which significantly increased their screen time. In general, social media networks, such as Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and blogs, help deaf individuals access information and keep abreast of ongoing sociopolitical processes (Casagrande, Citation2013). Deaf individuals also engage in internet browsing and social media compared more than their hearing peers (Maiorana-Basas & Pagliaro, Citation2014). However, the widespread adoption of social media platforms often leads individuals to become detached from the physical world (Casagrande, Citation2013). During the COVID-19 pandemic, when isolation was an inevitable outcome of lockdowns, social media helped people stay connected. The benefits of social media as a learning or social platform for deaf students were recognised by other scholars, who claimed that these platforms can alleviate loneliness and isolation among underprivileged students and expand formal and informal learning opportunities during distance classes (Mantzikos & Lappa, Citation2020). However, although the risk of isolation from the real world may have been mitigated, other associated risks persisted and intensified. These risks included unintended exposure to inappropriate content, privacy concerns, cyberbullying, compromised information security, and the potential for online stalking.

Nearly all the participants stated that the pandemic sparked contemplation about the future. Participants were recruited from specialised boarding schools for the deaf, which provided secure havens that shielded students from the adverse effects of isolation (Oleszkiewicz, Citation2021). Consequently, the unexpected shutdown of schools and the subsequent reintegration of students into hearing environments to some extent simulated post-school life, with its uncertainties, worries, and doubts.

Regrettably, according to the World Federation of the Deaf (WFD, Citation2003), 80% of deaf students lack access to quality education in the medium of sign language. Unfortunately, there are no deaf students at Georgian universities; typically, they pursue vocational education instead. Despite numerous reforms aimed at enhancing the accessibility and quality of education for children with special educational needs and preparing them for the local labour market, the employment of individuals with special needs continues to pose significant challenges in Georgia (Chanturidze & Verulava, Citation2018). Unfortunately, deaf individuals face greater uncertainty regarding their future education and workplaces, including potential exclusion from certain professions and emerging opportunities. Nevertheless, the increase in online education motivated some students to enhance their computer proficiency and recognise that specific professional skills could be acquired through platforms such as YouTube.

The study confirmed the overarching hypothesis that deaf students encountered challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, it also revealed several unexpectedly positive themes. Surprisingly, the students had predominantly positive perspectives on COVID-19, particularly concerning their families and the sense of togetherness fostered by the pandemic. Returning home was not necessarily a source of stress, even when some family members did not use sign language or used only informal, home signs. However, the participants consistently faced ongoing challenges in online education, which aligned with the global experience of deaf people during the pandemic.

Conclusion

Deaf people have been called “the forgotten victims of the pandemic” (Shin, Citation2020). However, deaf students in small, developing countries like Georgia were doubly forgotten since studies that brought their stories to an international audience were extremely rare. The dynamics of the interviews and the enthusiasm of deaf students about sharing their stories proved that young deaf students in Georgia greatly desire to interact with others.

The research was intended to address this gap by providing Georgian students with the opportunity to share their social experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. Overall, this study is significant because it contributes to the collective memory of deaf students during the COVID-19 pandemic, shedding light on their unique experiences and emphasising the need for increased interaction with and support for them now and in the future.

Undoubtedly, this study has certain limitations, one of which is the method of selecting deaf students for interview purposes. This study investigated the experiences of deaf students residing in specialised boarding schools during the COVID-19 pandemic. This decision was purposeful, as the study assumed that the experiences of deaf students residing in specialised boarding schools would differ markedly from those of students enrolled in mainstream schools. Nonetheless, it is imperative to acknowledge that many deaf students are educated in mainstream educational settings under the purview of inclusive education. Identifying these students would have required access to social services, government departments, and medical institutions – a logistical endeavour that was not feasible within the scope of this study.

Additionally, and notably, this study exclusively captured the perspectives of deaf students, but not the viewpoints of their family members and educators. This exclusion of essential stakeholders prevented a comprehensive understanding of the pandemic’s repercussions for the deaf community and those closely associated with it.

Future research could encompass a broader spectrum of deaf students and consider the different types of educational institutions with which they engage. Such research would foster a better understanding of the nuanced impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the diverse spectrum of deaf students. Given the foundation laid by this study, future researchers could explore the consequences of pandemics over extended periods. Additionally, future studies could delve into the challenges of readjusting to pre-pandemic routines and lifestyles.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Zhuzhuna Gviniashvili

Zhuzhuna Gviniashvili pursues her doctoral studies at Åbo Akademi University, Turku, Finland. Her academic focus centres on leisure reading across different population groups, such as young students, young adults, young immigrants, deaf students etc. Being originally from Georgia and a long resident in Finland, she is particularly interested in cross-cultural studies. Her research delves into the interplay between cultural influences and their effects on attitudes, preferences, and frequency of reading.

References

- Abulashvili, S., Khuroshvili, M., & Verulava, T. (2021). სკოლებში ადაპტირებული გარემოს ხელმისაწვდომობის კვლევა ყრუ/სმენადაქვეითებული ბავშვებისათვის [Access to an adapted school environment for deaf/hard of hearing children]. Health Policy, Econometrics and Sociology, 6(1), 1–11.

- Aljedaani, W., Krasniqi, R., Aljedaani, S., Mkaouer, M. W., Ludi, S., & Al-Raddah, K. (2022). If online learning works for you, what about deaf students? Emerging challenges of online learning for deaf and hearing-impaired students during COVID-19: A literature review. Universal Access in the Information Society, 22(3), 1027–1046. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10209-022-00897-5

- Allen, J., Mahamed, F., & Williams, K. (2020). Disparities in education: E-learning and COVID-19, who matters? Child & Youth Services, 41(3), 208–210. https://doi.org/10.1080/0145935X.2020.1834125

- Al Majali, S. A., & Alghazo, E. M. (2021). Mental health of individuals who are deaf during COVID-19: Depression, anxiety, aggression, and fear. Journal of Communication and Psychology, 49(6), 2134–2143. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.22539

- Alsadoon, E., & Turkestani, M. (2020). Virtual classrooms for hearing-impaired students during the coronavirus COVID-19 pandemic. Revista Romaneasca Pentru Educatie Multidimensionala [Romanian Magazine for Multidimensional Education], 12(2), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.18662/rrem/12.2/262

- Alshawabkeh, A. A., Woolsey, M. L., & Kharbat, F. F. (2021). Using online information technology for deaf students during COVID-19: A closer look from experience. Heliyon, 7(5), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e06915

- Altena, E., Baglioni, C., Espie, C. A., Ellis, J., Gavriloff, D., Holzinger, B., Schlarb, A., Frase, L., Jernelöv, S., & Riemann, D. (2020). Dealing with sleep problems during home confinement due to the COVID-19 outbreak: Practical recommendations from a task force of the European CBT-I Academy. Journal of Sleep Research, 29(4), https://doi.org/10.1111/jsr.13052

- Angelides, P., & Aravi, C. (2006). A comparative perspective on the experiences of deaf and hard of hearing individuals as students at mainstream and special schools. American Annals of the Deaf, 151(5), 476–487. https://doi.org/10.1353/aad.2007.0001

- Ashraf, S., Jahan, M., & Saad, M. (2021). Educating students with hearing impairment during COVID-19 pandemic: A case of inclusive and special schools. Review of Applied Management and Social Sciences, 4(4), 783–794. https://doi.org/10.47067/ramss.v4i4.183

- Azevedo, J. P., Gutierrez, M., de Hoyos, R., & Saavedra, J. (2021). The unequal impacts of COVID-19 on student learning. Primary and Secondary Education During COVID-19, 421–459. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-81500-4_16

- Barone Gibbs, B., Kline, C. E., Huber, K. A., Paley, J. L., & Perera, S. (2021). COVID-19 shelter-at-home and work, lifestyle and well-being in desk workers. Occupational Medicine, 71(2), 86–94. https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqab011

- Basilaia, G., & Kvavadze, D. (2020). Transition to online education in schools during a SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic in Georgia. Pedagogical Research, 5(4), em0060. https://doi.org/10.29333/pr/7937

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2012). Thematic analysis. In H. Cooper, P. M. Camic, D. L. Long, A. T. Panter, D. Rindskopf, & K. J. Sher (Eds.), APA handbook of research methods in psychology, Vol. 2: Research designs: Quantitative, qualitative, neuropsychological, and biological (pp. 57–71). American Psychological Association.

- Casagrande, V. (2013). Learning languages in social networks: Deaf people’s perception of Facebook as a linguistic environment [Doctoral dissertation]. Ca’ Foscari University of Venice. http://hdl.handle.net/10579/4561.

- Castro, H. C., Lins Ramos, A. S., Amorim, G., & Ratcliffe, N. A. (2020). COVID-19: Don’t forget deaf people. Nature, 579(7799), 343–343. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-00782-2

- Cavender, A. C., Bigham, J. P., & Ladner, R. (2009). Class in-focus: Enabling improved visual attention strategies for deaf and hard-of-hearing students. In Proceedings of the 11th International ACM SIGACCESS Conference on Computers and Accessibility (pp. 67–74). Association for Computing Machinery.

- Cedervall, Y., & Åberg, A. C. (2010). Physical activity and implications for well-being in mild Alzheimer’s disease: A qualitative case study on two men with dementia and their spouses. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice, 26(4), 226–239. https://doi.org/10.3109/09593980903423012

- Chanchlani, N., Buchanan, F., & Gill, P. J. (2020). Addressing the indirect effects of COVID-19 on the health of children and young people. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 192(32), https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.201008

- Chanturidze, M., & Verulava, T. (2018). შშმპ დასაქმების პოლიტიკა საქართველოში და ალტერნატიული გზები. ჯანდაცვის პოლიტიკა, ეკონომიკა და სოციოლოგია [Disability employment policy in Georgia and alternate roads]. Health Policy, Economics, and Sociology, 4(1), 1–24.

- Delegation of the European Union to Georgia. (2020). EU announces support package for Georgia [Press release]. EU announces support package for Georgia | EEAS.

- EFA Education Coalition. (2020). რა უნდა გავითვალისწინოთ 2020-2021 აკადემიური წლისათვის [Considerations for academic years 2020–2021]. რა უნდა გავითვალისწინოთ 2020-2021 აკადემიური წლისათვის.

- Engzell, P., Frey, A., & Verhagen, M. D. (2021). Learning loss due to school closures during the COVID-19 pandemic. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118(17), https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2022376118

- Erll, A. (2020). Afterword: Memory worlds in times of corona. Memory Studies, 13(5), 861–874. https://doi.org/10.1177/1750698020943014

- Fereday, J., & Muir-Cochrane, E. (2006). Demonstrating rigour using thematic analysis: A hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 5(1), 80–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690600500107

- Foster, S. (2019). Outsider in the deaf world: Reflections of an ethnographic researcher. Journal of the American Deafness and Rehabilitation Association, 27(3), 1–11. https://repository.wcsu.edu/jadara/vol27/iss3/6.

- Fuentes, P. S. C., Bravo, M. D. M. P., & Guillén, M. D. L. (2019). Perceived quality of care and satisfaction for deaf people with regard to primary care in a health area in the region of Murcia. Enfermería Global, 18(2), 303–322. https://doi.org/10.6018/eglobal.18.2.344761

- Guardino, C., & Cannon, J. E. (2016). Deafness and diversity: Reflections and directions. American Annals of the Deaf, 161(1), 104–112. https://doi.org/10.1353/aad.2016.0016

- Guest, G., MacQueen, K., & Namey, E. (2012). Introduction to thematic analysis. In G. Guest, K. MacQueen, & E. Namey (Eds.), Applied thematic analysis (pp. 3–21). SAGE Publications.

- Gugenheimer, J., Plaumann, K., Schaub, F., Di Campli San Vito, P., Duck, S., Rabus, M., & Rukzio, E. (2017). The impact of assistive technology on communication quality between deaf and hearing individuals. Proceedings of the 2017 ACM Conference on Computer-Supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing (pp. 669–682).

- Haakma, I., Janssen, M., & Minnaert, A. (2017). A literature review on the psychological needs of students with sensory loss. The Volta Review, 116(1/2), 29–58. https://doi.org/10.17955/tvr.116.1.2.768

- Hindley, P. A. (2005). Mental health problems in deaf children. Current Paediatrics, 15(2), 114–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cupe.2004.12.008

- Holloway, I., & Todres, L. (2003). The status of method: Flexibility, consistency and coherence. Qualitative Research, 3(3), 345–357. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794103033004

- Jackson, C. W., Traub, R. J., & Turnbull, A. P. (2008). Parents’ experiences with childhood deafness. Communication Disorders Quarterly, 29(2), 82–98. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525740108314865

- Karunaratne, N., & Karunaratne, D. (2020). The implications of hearing loss on a medical student: A personal view and learning points for medical educators. Medical Teacher, 43(11), 1333–1334. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2020.1839036

- Kritzer, K. L., & Smith, C. E. (2020). Educating deaf and hard-of-hearing students during COVID-19: What parents need to know. Hearing Journal, 73(8), 32. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.HJ.0000695836.90893.20

- Kushalnagar, R. (2019, October 28–30). A classroom accessibility analysis app for deaf students [Paper presentation]. The 21st International ACM SIGACCESS Conference on Computers and Accessibility, Pittsburgh, PA, USA.

- Kvirkvelia, N., & Tsitsagi, M. (2021). Impact of COVID-19 on tourism in Georgia: An overview. Georgian Geographical Journal, 1(1), 27–33. https://doi.org/10.52340/ggj.2021.08.10

- Lazzari, M., & Baroni, F. (2020). Remote teaching for deaf pupils during the COVID-19 emergency. In Proceedings of the IADIS Conference on E-learning 2020 (pp. 170–174). IADIS.

- Leung, L. (2015). Validity, reliability, and generalizability in qualitative research. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care, 4(3), 324. https://doi.org/10.4103/2249-4863.161306

- Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Establishing trustworthiness. In Y. S. Lincoln, & E. G. Guba (Eds.), Naturalistic enquiry (pp. 289–332). Sage.

- Loima, J. (2020). Socio-educational policies and COVID-19: A case study on Finland and Sweden in the spring 2020. International Journal of Education and Literacy Studies, 8(3), 59. https://doi.org/10.7575/aiac.ijels.v.8n.3p.59

- Lynn, M. A., Templeton, D. C., Ross, A. D., Gehret, A. U., Bida, M., Sanger, T. J., & Pagano, T. (2020). Successes and challenges in teaching chemistry to deaf and hard-of-hearing students in the time of COVID-19. Journal of Chemical Education, 97(9), 3322–3326. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jchemed.0c00602

- Mahmood, F., Acharya, D., Kumar, K., & Paudyal, V. (2021). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on ethnic minority communities: A qualitative study on the perspectives of ethnic minority community leaders. BMJ Open, 11(10), 10. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-050584

- Maiorana-Basas, M., & Pagliaro, C. M. (2014). Technology use among adults who are deaf and hard of hearing: A national survey. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 19(3), 400–410. https://doi.org/10.1093/deafed/enu005

- Makhashvili, N., Javakhishvili, J. D., Sturua, L., Pilauri, K., Fuhr, D. C., & Roberts, B. (2020). The influence of concern about COVID-19 on mental health in the Republic of Georgia: A cross-sectional study. Globalization and Health, 16(1), 2–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-020-00641-9

- Maldonado, J. E., & De Witte, K. (2021). The effect of school closures on standardised student test outcomes. British Educational Research Journal, 48(1), 49–94. https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3754

- Mantzikos, C. N., & Lappa, C. S. (2020). Difficulties and barriers in the education of deaf and hard of hearing individuals in the era of COVID-19: The case of Greece – a viewpoint article. European Journal of Special Education Research, 6(3), 75–95. https://doi.org/10.46827/ejse.v6i3.3357

- Matud, M. P. (2004). Gender differences in stress and coping styles. Personality and Individual Differences, 37(7), 1401–1415. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2004.01.010

- McDonald, G. (2000). Cross-cultural methodological issues in ethical research. Journal of Business Ethics, 27(1/2), 89–104. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1006406505398

- McElwain, N. L., & Volling, B. L. (2005). Preschool children’s interactions with friends and older siblings: Relationship specificity and joint contributions to problem behaviour. Journal of Family Psychology, 19(4), 486–496. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.19.4.486

- McNeill, H. (1985). Why study history. The American Historical Association.

- Ministry of Education and Science of Georgia. (2020). Pandemic and general education in Georgia. https://mes.gov.ge/mesgifs/1609844890_2020-Annual-report-ENG.pdf

- Mooney-Somers, J., Perz, J., & Ussher, J. M. (2008). A complex negotiation: Women’s experiences of naming and not naming premenstrual distress in couple relationships. Women & Health, 47(3), 57–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/03630240802134134

- Murray, J. J. (2020). Improving signed language and communication accessibility during COVID-19 Pandemic [online exclusive]. The Hearing Journal. https://journals.lww.com/thehearingjournal/blog/onlinefirst/pages/post.aspx?PostID=66

- Napier, J. (2004). Interpreting omissions. Interpreting: International Journal of Research and Practice in Interpreting, 6(2), 117–142. https://doi.org/10.1075/intp.6.2.02nap

- Nkoala, S. (2022). Educators’ experiences of using multilingual pedagogies during emergency remote teaching: A case study of South African universities. International Journal of Multilingualism, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2022.2074012

- Oleszkiewicz, A. (2021). Blindness enhances interpersonal trust, but deafness impedes the social exchange balance. Personality and Individual Differences, 170, 110425. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.110425

- Ornell, F., Schuch, J. B., Sordi, A. O., & Kessler, F. H. P. (2020). “Pandemic fear” and COVID-19: Mental health burden and strategies. Brazilian Journal of Psychiatry, 42(3), 232–235. https://doi.org/10.1590/1516-4446-2020-0008

- Pachkoria, T., Laghidze, A., & Hegna, H. (2012). განათლების სისტემა სმენის დარღვევის მქონე მოსწავლეებისთვის. რედ. პაჭკორია, თ. მენის დარღვევის მქონე მოსწავლეების სწავლება. [Educational Systems for Deaf and Hard-of-Hearing Students]. In T. Pachkoria (Ed.), Teaching Students with Hearing Impairment (pp. 55–88). The Portal of National Curriculums.

- Polkinghorne, D. E. (2007). Validity issues in narrative research. Qualitative Inquiry, 13(4), 471–486. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800406297670

- Ramadhana, M. R., Karsidi, R., Utari, P., & Kartono, D. T. (2020). Building communication with deaf children during the COVID-19 pandemic. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Social and Political Sciences (ICOSAPS 2020) (pp. 1–8). Atlantis Press.

- Ramsey, C. (2004). What does culture have to do with the education of students who are deaf or hard of hearing? In B. Brueggemann (Ed.), Literacy and deaf people: Cultural and contextual perspectives (pp. 47–58). Gallaudet University Press.

- Rui Xia Ang, J., Liu, P., McDonnell, E., & Coppola, S. (2022, April 29–May 5). In this online environment, we’re limited. CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, New Orleans, LA, USA.

- Rusieshvili, M., & Gözpınar, H. (2014). Similar and unique in the family: How to raise children (using examples of Turkish and Georgian proverbs relating to children). Journal of Language and Linguistic Studies, 10(1), 67–77.

- Shin, S. (2020). The forgotten victims of the pandemic: The deaf community. https://www.ozy.com/news-and-politics/the-forgotten-victims-of-the-pandemic-the-deaf-community/303802/

- Singh, M. M., Garg, S., Deshmukh, C. P., Borle, A., & Wilson, B. S. (2021). Challenges of the deaf and hearing impaired in the masked world of COVID-19. Indian Journal of Community Medicine, 46(1), 11. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijcm.IJCM_581_20

- Smith, C., & Colton, S. (2020). Creating a YouTube channel to equip parents and teachers of students who are deaf. Journal of Technology and Teacher Education, 28(2), 453–461. https://www.learntechlib.org/primary/p/216283/.

- Swanwick, R., Oppong, A. M., Offei, Y. N., Fobi, D., Appau, O., Fobi, J., & Mantey, F. F. (2020). The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on deaf adults, children and their families in Ghana. Journal of the British Academy, 8, 141–165. https://doi.org/10.5871/jba/008.141

- Szarkowski, A., & Dirks, E. (2021). Fathers of young deaf or hard-of-hearing children: A systematic review. The Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 26(2), 187–208. https://doi.org/10.1093/deafed/enaa039

- Takala, M., Kuusela, J., & Takala, E.-P. (2000). ‘A good future for deaf children’: A five-year sign language intervention project. American Annals of the Deaf, 145(4), 366–374. https://doi.org/10.1353/aad.2012.0078

- Tamres, L. K., Janicki, D., & Helgeson, V. S. (2002). Sex differences in coping behaviour: A meta-analytic review and an examination of relative coping. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 6(1), 2–30. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327957PSPR0601_1

- Tigwell, G. W., Peiris, R. L., Watson, S., Garavuso, G. M., & Miller, H. (2020, October 26–28). Student and teacher perspectives of learning ASL in an online setting [Conference paper]. The 22nd International ACM SIGACCESS Conference on Computers and Accessibility, Athens, Greece.

- Tomasuolo, E., Gulli, T., Volterra, V., & Fontana, S. (2021). The Italian deaf community at the time of coronavirus. Frontiers in Sociology, 5, https://doi.org/10.3389/fsoc.2020.612559

- Vaismoradi, M., Jones, J., Turunen, H., & Snelgrove, S. (2016). Theme development in qualitative content analysis and thematic analysis. Journal of Nursing Education and Practice, 6(5), 100–110. https://doi.org/10.5430/jnep.v6n5p100

- Vertegaal, R., Weevers, I., & Sohn, C. (2002, 20 April). GAZE-2: An attentive video conferencing system. In Proceedings of the CHI ‘02 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Kingston, ON, Canada (pp. 736–737). https://doi.org/10.1145/506443.506572

- Weaver, K. A., & Starner, T. (2011). We need to communicate!. The Proceedings of the 13th International ACM SIGACCESS Conference on Computers and Accessibility.

- Whitney, K. S., & Whitney, K. (2022). Inaccessible media during the COVID-19 crisis intersects with the language deprivation crisis for young deaf children in the U.S. Children and Media Research and Practice During the Crises of 2020, 31–34. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003273998-9

- World Federation of the Deaf. (2003). Position paper regarding the United Nations convention on the rights of people with disabilities, ad hoc committee on a comprehensive and integral international convention on the protection and promotion of the rights and dignity of persons with disabilities. https://www.un.org/esa/socdev/enable/rights/contrib-wfd.htm

- Yogman, M., Garfield, C. F., Bauer, N. S., Gambon, T. B., Lavin, A., Lemmon, K. M., Mattson, G., Rafferty, J. R., & Wissow, L. S. (2016). Fathers’ roles in the care and development of their children: The role of paediatricians. Pediatrics, 138(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-1128