Abstract

To cope with the multi-faceted challenges our world is increasingly confronted with, new planning approaches aimed at integration and collaboration are adopted. Co-creation is one of them. In literature, co-creation is described as facilitating innovation and creativity. Similar to other collaborative approaches, it can build institutional capacity and thereby adaptivity for coping with current challenges. Through an in-depth study of the case of replanning the Hegewarren polder in the Netherlands, we show that a co-creation process can support the development of institutional capacity by enhancing its three components – intellectual, social, and political capital.

Introduction

Our world is increasingly confronted with multi-faceted challenges encompassing technical, ecological, economic, and social dimensions. Coping with them requires exploring ‘win-win-wins’ that combine economic, social and environmental aspects through collaboration among diverse stakeholders, and experimentation with new flexible, cooperative and integrative planning approaches. Consequently, in planning practice there have emerged various collaborative approaches (Ansell & Torfing, Citation2021; Puerari et al., Citation2018), which respect and seek to integrate the stakeholders’ heterogeneity of values, perspectives, and types of knowledge, and show “explicit appreciation of complexity and uncertainty, likelihood of surprise and need for flexibility and adaptive capacity” (Kemp et al., Citation2005, p. 17).

One of these collaborative approaches is co-creation. It originates from the business domain, where it successfully created innovative products and services due to involving customers in the creation process (Ansell & Torfing, Citation2021; Prahalad & Ramaswamy, Citation2004; Puerari et al., Citation2018). Co-creation has recently gained popularity in planning due to its expected benefits not only in terms of innovation and creativity but also in terms of creating a more fair, sustainable and socially connected society in the face of increasingly intricate challenges (Ansell & Torfing, Citation2021; Leino & Puumala, Citation2021; Voorberg et al., Citation2015). Co-creation has numerous interpretations derived from the various domains where it is utilized. We follow the definition proposed by Ansell and Torfing (Citation2021), who define co-creation as a “process through which a broad range of interdependent actors engage in distributed, cross-boundary collaboration in order to define common problems and design and implement new and better solutions” (p. 6). This definition indicates that the contribution of ‘co-creation’ to the planning field may go beyond creating smart alternatives by building institutional capacity, defined by Polk (Citation2011) as the ability to respond to and manage social and environmental challenges through decision-making, planning and implementation processes.

Existing studies have mainly focused on definitional issues, on the conditions co-creation needs to thrive, and its tangible outcomes (Ansell & Torfing, Citation2021; Voorberg et al., Citation2015). Our research explores whether and how co-creation, as a collaborative planning approach, may contribute to building institutional capacity for integrative, collaborative, and adaptive (spatial) planning. The research is structured around three constituting elements, namely the intellectual capital or knowledge resources, the social capital or social networks and relations, and political capital or the capacity to act collectively (Healey, Citation2006; Khakee, Citation2002), which Cars et al. (Citation2017) identify as the building blocks of institutional capacity.

To understand how co-creation may enable the development of institutional capacity in practice, we adopt an in-depth case study approach (Flyvbjerg, Citation2001) and look at how the intellectual, social, and political capitals are expressed over time in the replanning case of the Hegewarren polder, situated in the Province of Friesland, in the northern Netherlands. In this case, the Province of Friesland (‘the Province’), in collaboration with Waterboard Friesland (‘the Waterboard’) and the Smallingerland Municipality (‘the Municipality’), initiated a process to co-create potential future development scenarios for the polder.

The following section provides an overview of the elements of our analytical framework. Next, we introduce the research methodology and an overview of the case study, followed by a section providing the case study findings. The last two sections consist of the analysis and discussion, respectively the conclusions of our research.

Capacity Building through Co-Creation. A Capitals’ Perspective

To explore whether and how co-creation contributes to building institutional capacity, we follow Cars et al. (Citation2017), who argue that building up institutional capacity happens by affecting each of its three components: the knowledge resources (intellectual capital), the relational resources (social capital), and the capacity for mobilization (political capital).

Intellectual Capital

The intellectual capital refers to a collective social knowledge and knowing capability (Nahapiet & Ghoshal, Citation1998). As previously mentioned, challenges in planning may be defined in multiple ways and may have multiple responses depending on the different stakeholders’ knowledge, values, perspectives and interests. Therefore, a diverse base of knowledge resources is essential for enabling a comprehensive perspective of the problem at stake, formulating a joint problem definition, and boosting ‘collective creativity’ (Puerari et al., Citation2018; Rădulescu et al., Citation2022). From the reviewed literature, we distinguish four key attributes for building intellectual capital: integration of knowledge, local knowledge, reflection and evaluation, and integrators.

According to Ansell and Torfing (Citation2021), it is important that the co-creation process stimulates the integration of knowledge, understood as “the process of bundling knowledge from diverse sources to jointly solve complex problems” (Acharya et al., Citation2022, p. 1). Ansell and Torfing (Citation2021) mention knowledge integration as paramount for advancing problem-solving capacity because “innovations are new combinations of existing knowledge and incremental learning” (Kogut & Zander, Citation1992, p. 392).

Further, a co-creation process should incorporate local knowledge developed through the stakeholders’ experiences related to the context and location (Edelenbos et al., Citation2011; Hilbers et al., Citation2022; Kyttä et al., Citation2013). Integrating local knowledge with scientific or expert knowledge, in which the focus is mainly on technical expertise (Van Buuren & Edelenbos, Citation2004), together with bureaucratic knowledge that connects to administrative and governmental practices (Edelenbos et al., Citation2011), is essential for the design alternatives to be context-responsive.

According to Akhilesh (Citation2017) and Rill and Hämäläinen (Citation2018), a co-creation process should resemble a learning journey and take the form of an iterative process sprinkled with moments of reflection and evaluation. Multiple iterative loops allow improvement through learning (Hagman et al., Citation2018; Steen & Van Bueren, Citation2017). Rădulescu et al. (Citation2022) show that a co-creation process can include loops during the initial phase for the creation of a generally agreed upon problem definition and process rules, during the co-creative design phase when design alternatives are developed, or during the evaluation phase when groups of internal or external evaluators appraise these alternatives and propose changes or refinements. Finally, given the practical, normative, epistemic and ontological challenges of knowledge integration (Byskov, Citation2020), for the building up intellectual capital, co-creation processes need integrators. According to Nyström et al. (Citation2014), integrators are people with the capacity and experience to understand the language and perspectives of others, and thus have the ability to integrate heterogenous knowledge and development ideas into a functional entity.

Social Capital

According to Bourdieu (Citation1986), social capital is “the aggregate of the actual or potential resources which are linked to possession of a durable network of more or less institutionalized relationships of mutual acquaintance and recognition” (p. 248). Social capital refers to the social structures and interpersonal relations (Som, Citation2014) and the creation and maintenance of social relations and interactions between diverse stakeholders. These result in the build-up of ‘relational resources’ (Healey, Citation2006; Khakee, Citation2002), thus enabling the creation of coalitions and the development of shared values for influencing decision-making processes.

According to Rill and Hämäläinen (Citation2018) and Steen and Van Bueren (Citation2017), for a co-creation process inclusiveness and diversity is essential. A co-creation process characterized by inclusiveness and diversity encompasses a wide range of stakeholders and their various perspectives, and fosters the identification of innovative ways to build upon interdependencies and develop collective creativity (Ansell & Torfing, Citation2021; Rill & Hämäläinen, Citation2018).

For the social interactions to flourish and the relational resources to emerge, the co-creation process needs to be based on and foster trust among the different stakeholders. Various authors stress the importance of initial trust, which is influenced by the history of stakeholder relations (Ansell & Gash, Citation2007; Bryson et al., Citation2006). Antecedents of hostile relations determine low levels of trust and low commitment and willingness for co-creation (Ansell & Gash, Citation2007). Contrarywise, antecedents of good cooperation prompt stakeholders’ willingness to co-create because they serve as guarantees for adopting a risk-taking behaviour, which “is not about avoiding or eliminating vulnerability, or resigning to it, but about positively accepting it” (Möllering, Citation2008, p. 8). Important is also the cultural context in which the co-creation process is embedded. Meyer (Citation2015) distinguishes between countries that favour task-based trust (e.g., Netherlands, Denmark, Germany, US) that is built through business-related activities, and countries that favour trust based on social relations (e.g., Spain, Italy, Mexico, Brazil). According to Vangen and Huxham (Citation2003), the design of a co-creation process, its place within the formal planning and decision-making process, and the wide range of stakeholders involved can bring about power imbalances which may lead to mistrust. To prevent mistrust and to enable social capital building, attention needs to be paid to the different dimensions of trust and their dynamics over time, i.e., the trust based on interpersonal bonds and interaction built via personal contact, the trust based on others’ values and norms, and the trust in (planning) institutions, the planning system and the planning profession (Laine et al., Citation2022; Swain & Tait, Citation2007).

By enabling social interactions among diverse stakeholders that possess various skills, knowledge resources, and expertise, co-creation may facilitate building a shared language, a shared vision, and shared values (Ansell & Torfing, Citation2021; Hagman et al., Citation2018; Steen & Van Bueren, Citation2017). For this, it is vital to keep the language simple, eliminate jargon as much as possible, and ensure that all participants feel welcome and willing to engage (Rădulescu et al., Citation2022; Steen & Van Bueren, Citation2017). A shared language provides a “shared medium of communication” (Hedlund, Citation1999, p. 11) that helps build mutual understanding and social capital.

According to Haataja et al. (Citation2018), for social relations to develop throughout a co-creation process, a key role is played by the facilitator who creates a suitable atmosphere, helps to create trust, enables a multi-voiced creative process, and ensures the fluency of the process. The facilitator enables the transformation of a group of stakeholders into one with a shared vision and values, all while remaining outside the actual development process (Hagman et al., Citation2018; Heikkinen et al., Citation2007).

Political Capital

Szreter and Woolcock (Citation2004, p. 655) define political capital as “the norms of respect and networks of trusting relationships between people who are interacting across explicit, formal or institutionalized power or authority gradients in society.” Political capital relates to power relations, potentially enabling better resources, a better position, and a stronger voice in the planning process.

Being aimed at facilitating change, co-creation processes need to mobilize as much knowledge, relational, financial or technical resources as possible (Ansell & Torfing, Citation2021; Steen & Van Bueren, Citation2017). This is because the generation and implementation of innovative interventions can be improved when different resources are mobilized, exchanged, and coordinated (Hartley et al., Citation2013).

Torfing et al. (Citation2021) argue that co-creation helps to build joint ownership of the process and the created alternatives, thus promoting their flow through the decision-making process and leading to their implementation. Participation and dialogue (Hartley et al., Citation2013) regarding the design and management decisions and the allocation of roles, tasks and responsibilities supports joint ownership building.

For building up political capital, it is vital to create storylines, understood as “narratives on social reality through which elements from many different domains are combined and that provide actors with a set of symbolic references that suggest a common understanding” (Hajer, Citation1997, p. 62). Storylines define problems, alternatives and goals in rather broad and ambiguous terms, and put in the spotlight a winning argument that can attract and align multiple stakeholders with diverging interests (Ansell & Torfing, Citation2021). All-encompassing storylines help to build political support and thus contribute to the ‘migration’ of creative outcomes outside the informal co-creation arena towards the formal planning and decision-making arenas.

Finally, adopting collaborative planning approaches which involve process- and organizational-related changes, requires key persons in mobilization efforts (Khakee, Citation2002). Hence, Bonvillian and Weiss (Citation2015) stress the critical role of change agents as catalysts for change. Change agents are experienced and knowledgeable individuals who can overcome potential resistance from different institutions and promote and enable the adoption of new practices (Battilana & Casciaro, Citation2012). They often hold multiple roles and responsibilities, i.e., agent for community participation, trust builder, networker, leader, socially responsible advocate, resource developer, proactive innovator, financial supporter, or strategic planner (Schulenkorf, Citation2010). According to Rotmans and Verheijden (Citation2021) it is the combination of different types of change agents that plays a determining role at different stages. The art is to find and bring together the different types of change agents within the governmental bodies, the private sector, the societal organisations and the local communities. Facilitating change agents can influence the lean transformation of planning practices and, in the long run, the utilization of co-creation processes not only as niche experiments but as systemic approaches.

An Analytical Framework for Exploring Institutional Capacity Building through Co-Creation

The framework presented in summarizes the constituting elements of the three components of institutional capital as discussed above and represents the backbone of our research based on linking literature about capitals with literature about co-creation.

Table 1. Analytical framework for exploring institutional capacity building through co-creation.

Methodology

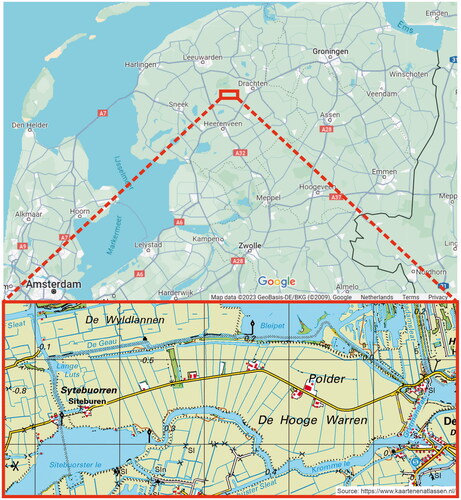

To obtain a nuanced, empirically-rich view of how co-creation may support institutional capacity building, we adopted an exploratory in-depth case study approach (Flyvbjerg, Citation2001) of the Hegewarren polder in the Province of Friesland (). We followed, in real-time, the co-creation process from its inception until the decision-making phase.

Our research used a multi-methods qualitative approach involving process observation, in-depth semi-structured interviews with key stakeholders, and documents’ analysis. Through observation in a pre-defined setting, determined by the Hegewarren case’s planning process, the principal author, a young female researcher, followed the co-creation process for approximately two years. The observation was overt and passive; the Province’s project manager informed all those involved about the researcher’s presence and the scope of the research, and permitted the researcher to observe the co-creation sessions, the weekly communication meetings, the periodic meetings with the extended project team and those with the advisory committee.

We triangulated the notes taken during observation with data from ten in-depth, semi-structured interviews with key stakeholders involved in the co-creation process (). The interviews were conducted between May and June 2021 and lasted between 40 and 70 minutes. Given the Covid-19 restrictions, interviews were conducted online, in the language preferred by the interviewee, Dutch or Frisian. Interviewees were informed about the purpose of the research and consented to audio recording and data interpretation and utilization. All interviews were fully transcribed, translated into English and rendered anonymous, following the ethical guidelines of the University of Groningen. Data gathered from observation (see ) and interviews (see ) was complemented with a review of documentary sources, including internal project documents, reports, and media communication materials (see ). The transcripts and documents were qualitatively analysed using a coding scheme based on the analytical framework from ; it consisted of codes related to the three elements of institutional capacity, i.e., intellectual, social, and political capital, and their corresponding attributes.

The Hegewarren Polder Co-Creation Process

The Hegewarren polder is located in the Province of Friesland, in northern Netherlands (). The 360 hectares of agricultural land, situated on a thick peat meadow, and enclosed by water, nature, and recreational areas, are confronted with multiple interrelated challenges like climate change, peat layer oxidation and soil subsidence, greenhouse gas emissions, and onerous maintenance of the polder quays. To deal with these problems, in 2019, in cooperation with the Waterboard, the Province designated the polder as a development area in the provincial Peat Meadow Areas Vision. Given the area’s numerous stakeholders and varied interests, an integrated area development approach was deemed necessary. For this, a co-creation approach was adopted to bring together the different stakeholders, bundle the challenges and opportunities, and explore creative design alternatives for the polder.

In November 2019, the initiation phase started. Given the broader perspective and the numerous interested stakeholders, the Province, the Waterboard and the Municipality jointly decided to start a co-creation process aimed at identifying responses for current challenges and for improving the polder’s water system, recreation and farming activities started (Eindrapport co-creatieproces Hegewarren, Citation2021).

The preparatory phase started around March 2020 with a stakeholder-analysis conducted by the initiators. They identified potential co-creators – political actors, decision-makers, and actors from the agriculture, recreation and tourism, water sports, and nature conservation sectors. Further, the initiators contracted a team of facilitators (Open Kaart) for steering the process, a team of landscape architects (H + N + S Architects) for supporting the process with ideas and drawings, and a team of engineers and consultants (RHDHV) for helping with detailing and modelling the ideas.

The co-creative design phase started in November 2020 with an introduction meeting in which 54 stakeholders were present. The initiators exposed the polder’s challenges and explained their choice for a co-creative approach. The initiating parties set the basics of the co-creation process, its main goals – reducing CO2 emissions, lowering water system’s costs, reducing desiccation of the nature area – and the conditions for a more robust water system. Based on the earlier identified representative stakeholders, interests and perspectives, the initiators selected the core members of the co-creation team, hereafter referred to as co-creators (see ).

Afterwards, six co-creative sessions were organised between November 2020 and May 2021. We present an overview of these workshops and their content in . Parallel, expert knowledge was brought in through thematic sessions called ‘college tours’, in which experts from various domains shared information that the co-creators, together with the landscape architects and the engineers involved in the process, could use to shape future development scenarios for the polder.

The co-creation process ended with an evaluation phase in Atelier 6 where the co-creators internally reviewed and clarified each alternative’s advantages and disadvantages. Subsequently, the alternatives were shared via the newsletter with a broader group of stakeholders, and with the politicians. Based on the feedback received, specific themes were deepened and the variants were refined. In Atelier 7, the co-creators voted for and argued in favour of their two preferred alternatives, which were handed over to the initiators in October 2021, thus marking the linking moment with the formal decision-making process.

Findings

The findings will be described hereafter following the framework presented in . Further, in , we outline some key activities that contributed to the build-up of intellectual, social and political capitals.

Table 2. Overview of key activities for building institutional capacity in the Hegewarren polder case.

Intellectual Capital

From its inception, the co-creative approach was aimed at the integration of knowledge. The expert knowledge was brought in by the landscape architecture and engineering bureaus. Additional expert knowledge on water management and safety, land and water recreation, CO2 emission schemes, business models in peat areas, wet farming/paludiculture and nature-inclusive farming, and building with nature was brough in through thematic sessions, each led by an expert in one of the aforementioned topics (see ). However, the co-creators sometimes felt the expert knowledge was too detached from the local context; for example, Interviewee 9 stated “especially in the beginning, I found the knowledge of the area a problem, but that gradually got better.” The facilitator and the advisory committee members, two professionals with vast experience in living labs and co-creation processes, brought specific knowledge on the design of the co-creation processes. According to Interviewee 5, very important was the advisory committee, whose members were not involved directly in the co-creation process, and thus could bring in factual information and a neutral perspective on the critical aspects of the design and evolution of the co-creation process.

Local or experiential knowledge represented one of the main reasons for starting the co-creation process because, as Interviewee 5 argued, the mix of local and expert knowledge is essential for having a good sense of the place when creating development alternatives. Local knowledge was brought in by the co-creators, i.e., the inhabitants of the polder (farmers, recreation business owners, holiday house owners, sailing school owners), ‘neighbours’ of the polder (interest groups of the surrounding villages and the National Park De Alde Feanen), and cross-regional stakeholders (water sports associations, nature conservation and agricultural nature management organisations, inland shipping organisation). The team shared locally-grounded knowledge, such as the accessibility of bicycle routes and ferries, and fed the process with multiple perspectives about different issues, such as water safety. This information proved extremely valuable because “there are always things about an area that are very specific and about which information is outdated, or not detailed enough or simply not correct” (Interviewee 4). Similarly, Interviewee 6 argued that “an expert can never know the whole local situation, but must be able to listen well and translate.” The co-creation process was marked by moments of reflection and evaluation, and multiple iterative loops (rounds). Although the co-creation process was iterative, Interviewee 2 mentioned that some steps came too early, leading to the recalibration of the process. Or, as Interviewee 1 mentioned:

you work from coarse-to-fine; you try something out and based on that you learn new things and you take the next step. However, the experts were already calculating the end product, while we just needed an intermediary step.

In these iterations, the landscape architect acted as an integrator in the process by bringing together the different perspectives and interests, and coupling local and expert knowledge in integrated designs. Interviewee 2 acknowledged this role of “the spatial integrator who brings together goals, ideas and wishes in a logical way.”

Social Capital

Much attention was paid in the process design to inclusiveness and diversity. Firstly, a stakeholder analysis was done in the preparatory phase to pre-select the co-creation team based on the rings of influence model (Rădulescu et al., Citation2022) to identify all possible concerned stakeholders, their current role, the role they might want to have in the co-creation process and the role that the co-creation process initiators would like them to have. A key moment that reflects the inclusiveness and diversity was the general information meeting. However, the co-creation team’s diversity is not equally acknowledged by all its members; for example, Interviewee 8 remarked that

There are all kinds of people at the table who have an interest but have no knowledge, and they sit at the table because they live or work there. They see the area very differently than people who look at it from the content point of view; and I still find difficult the combination between the layman who has a certain opinion in that session in connection with an expert opinion.

As a result of diversity, Interviewee 1 indicated that it took extra effort and time to make the dialogue inclusive. Contrastingly, Interviewee 2 considered “the composition of the co-creation team one-sided, not so much in terms of themes, but they are all elderly men.”

Each co-creation and thematic session was designed to build trust by working together and establishing common ground. The thematic sessions and the small break-out rooms discussions supported a lively dialogue between participants and led to increased trust. Significantly, participants’ trust in the government proved difficult; Interviewee 5 mentioned: “trust in the government is pretty minimal, and despite our best efforts, there’s much doubt about how fair they’ll be.” Similarly, Interviewee 2 stated that regarding the co-creation process’ outcome, people “did not trust the authorities to make the right choice.” At the beginning of the process, there was much mistrust about the government’s position in combining the alternatives with a new waterway, which was a political wish (Interviewee 4). Trust was also enhanced by providing the opportunity to develop alternatives without this waterway. The trust-building process was partly constrained by the digital co-creation process due to the Covid-19 pandemic. Interviewee 5 indicated that “it takes much longer in a digital process before trust is established, and it is also difficult to maintain.” Similarly, Interviewees 1 and 4 revealed that a digital co-creation process limits informal moments and trust-building opportunities.

The information meeting at the beginning of the process, in which the co-creation process was explained and dilemmas and questions were shared, was crucial for building shared values and a shared vision for the polder. By sharing and discussing their interests and perspectives throughout the process, the co-creators became aware of each other’s positions. This awareness further increased in Atelier 1 when each co-creator was asked to highlight what they found valuable in the polder and how they viewed its future. Interviewee 10 indicated: “in the beginning, it took some time getting used to letting go of your interest and coming to something together.” Another important moment for creating shared values and a shared vision was the joint development, in Atelier 3, of the assessment framework for evaluating the design alternatives. The review and the choice and argumentation of two preferred alternatives by the co-creators in Atelier 7 acted as a consolidation moment. Interestingly, this step was perceived more nuanced by Interviewee 10, who mentioned that co-creation is about bringing people to work together and understand each other’s problems, but forcing them to make choices makes everyone return to their initial position. The development of a set of shared values and a shared vision is reflected by the co-creation team’s final selection of two preferred alternatives, which shows that despite their differences, they were able to find proposals acceptable enough to support them.

Additionally, the co-creation process contributed to developing a shared language synergistically with creating shared values and vision. First, the emergence of shared language was observed when highly complex or specialized information had to be transmitted in an easily comprehensible manner to the stakeholders. Secondly, we observed the creation of a shared language when trying to make the different stakeholder’s perspectives understandable so that each can put themselves in the shoes of the others. However, this proved sometimes tricky, as Interviewee 4 argued that “what experts use and what participants use are different languages.”

In developing a shared language, shared values and a shared vision, a crucial role was played by the facilitator(s). They acted as ‘knowledge brokers’ who translated the information between the co-creation team members, but also between them and the experts. Further, the facilitators acted as mediators – making co-creators aware of each other’s perspectives, or as Interviewee 10 indicated, “intervening at the right moment, but also binding people together.” According to Interviewee 3, the facilitator was also available for individual consultations, via phone or email, for those who wanted to share their opinion or perspectives privately. As a result, the different rounds could be better prepared and organized. The facilitator generally ‘steered’ the process and explained what each round was aimed at, managed to crystalize the ideas and perspectives of the co-creation team members, and translated them to the experts and vice versa in each round. The facilitator also ensured communication with the external world by managing a website and sending regular updates about the process.

Political Capital

The co-creation process of the Hegewarren polder was jointly initiated by the Province, the Municipality and the Waterboard, all concerned with and responsible for the mobilization of resources. They signed a cooperation agreement which indicated the financial commitments and the distribution of risks and revenues. Additionally, the initiators coordinated the provincial objectives with the national ones and mobilized different streams of financial resources, for example, to reduce CO2 emissions.

The memos and reports for the presentation of the co-creation process adopted a storyline constructed along the lines of adaptiveness, integration, public engagement, and experimentation, which consists of phrasings like: “the socially most optimal future design of the area through an integrated area process,” “we do this with the environment in co-creation,” “not only the peat meadow and nitrogen tasks are considered, but also other tasks such as renewable energy, a robust water system and recreation” (Eindrapport co-creatieproces Hegewarren, Citation2021). Although the storyline represents just a part of the story of translating the broad range of challenges into tangible outputs of the co-creation process, it represents a powerful message and signal given to the stakeholders in the area that a new inclusive approach to the integrated spatial redevelopment of the polder was adopted involving an active role of the stakeholders in sketching the design alternatives for the future.

The joint initiation of the co-creation process by stakeholders situated on both local and regional tiers, promoted joint ownership of the process and its outcomes. However, Interviewee 5 stated, “the interaction with governments was too minimal; perhaps we were a little too reluctant to put governments at the table.” This approach of the initiators was triggered by the lack of trust in the government, as mentioned above. As a result, the initiators’ sense of ownership of the process and its outcomes might have been negatively impacted.

By acting from the early phases of the project as a supporter of a co-creation approach aimed at fostering the involvement, participation and cooperation of the different local, regional and national stakeholders, the project manager from the province of Friesland acted as a change agent. By putting the community central in the Hegewarren polder redevelopment process through a co-creative approach, she also acted as an initiator (Goudswaard & van Oosten, Citation2022). She (Interviewee 5) commented on the adoption of a co-creative approach:

‘mienskip’ (‘community’ in Frisian) is number one priority. I think it is inappropriate to do that only with governments and agencies and with the occasional public consultation because those people live there. They know a lot, and have to deal with the consequences for a long time. We don’t. So, I think it’s essential to put them in the centre.

Analysis and Discussion

Our research focused on a case of co-creation within the planning domain. Whilst it shares similarities with the concept of public participation, co-creation is an approach with a different flavour. Arnstein (Citation1969) presents public participation as a ladder in which each rung corresponds to a different degree of citizen participation and involvement in the planning processes, thus exposing and challenging existing power relations. On the other hand, ideally, a co-creation process provides a fair playing field for all stakeholders, the ‘co’, meaning that all relevant stakes and stakeholders are involved in the creation process. In our case, the co-creation process was placed outside the formal planning and decision-making trajectory to protect it from power relation pressures, especially those from the government, and to give room for local flavour and creativity. This positioning, together with the fact that the co-creation team members act on behalf of different groups and some are embedded within different organisations (e.g., farmers’ organisation), posed challenges to the organisation (‘co’) and the process (‘creation’) in relation to institutional capacity building by strengthening the three types of capital.

Intellectual Capital

The co-creation process brought together expert, local and bureaucratic knowledge related to farming, water navigation and safety, land and water recreation, land use planning, and nature conservation. The co-creation process has contributed to creating new intellectual capital, as each developed scenario for the polder represents a (re)combination of different types of knowledge (Nahapiet & Ghoshal, Citation1998). In line with the literature (Kurtzberg & Amabile, Citation2001; Mangelsdorf, Citation2018; Verhoeven, Citation2021) the case shows that the iterative combination of co-creation and thematic sessions facilitated the integration of different knowledge resources, thus generating creativity. However, the exchange and combination of diverse knowledge resources came with challenges resulting from the difficult communication of knowledge and the non-overlapping types of knowledge among those participating in the process (Verhoeven, Citation2021). Thus, our findings highlight the essential role played by the facilitators and landscape architects, who, due to their more generalist training and broader perspective, could, on the one hand, act as a communication hub that eased the exchange of knowledge (as also discussed by Verhoeven, Citation2021), and on the other hand act as integrators who helped with the combination of knowledge.

However, the role of facilitator, communication hub and integrator came with challenges. Significant was the discrepancy between the expectations of some co-creators and those of the experts concerning the process’s freedom, flexibility, timeline, and rhythm. While the co-creators were expecting a less structured and freer-from-constraints process, the project team initially adopted a linear phased (‘project management’) approach, considering the time and budget constraints the initiators imposed. In reaction to both the formal (e.g., the co-creative and thematic sessions, the pre-planned feedback moments) and the informal (e.g., informal chats with the facilitators) channels of communication that allowed the co-creators to voice their concerns and frustrations regarding the evolution of the process, supplementary co-creation sessions, enriched with moments of reflection and evaluation, were added. The extra iterative loops and alterations of the timeline reveal the stakeholders’ engagement and ability to change the process and its co-creative nature. Further, this confirms that there can be no blueprint for interactive and multi-stakeholder processes, that “facilitating a co-creation process in an inclusive and participatory manner is a time-consuming activity that neither conforms to pre-set schedules, nor can be based on predetermined activities” (Leino & Puumala, Citation2021, p. 791), and that “maximum flexibility for fine-tuning and adaptation must be accommodated because each process is unique and iteratively evolving” (Rădulescu et al., Citation2022, p. 483).

Social Capital

The findings show that a strength of the co-creation process was the inclusive approach towards bringing together a diverse group of stakeholders in terms of occupation, interests, location, and a diverse group of experts regarding background and expertise. Mangelsdorf (Citation2018) asserts that team diversity has a higher probability of interpersonal conflicts, which we did not observe. The lack of conflict within the co-creation team can be explained by age homogeneity, which correlates with a shared generational set of values, ideas, beliefs and ethics, but also with relational benefits, such as better and more frequent communication (Johnson & Romanello, Citation2005; Williams, Citation2016). According to Johnson and Romanello (Citation2005), age homogeneity can contribute to a lack of conflicts due to similarities in learning and collaboration styles. In line with the findings of Reagans (Citation2011), our results indicate that the positive effects of age similarity were amplified by the proximity of the co-creation team members, who all live in the polder or its vicinity.

The co-creators’ homogeneity regarding age, gender and physical proximity indicates bonding social capital (Putnam, Citation1995) and, consequently, some potential degree of initial trust. Following previous studies (for example, Swain & Tait, Citation2007), our findings expose the mistrust in government and institutions. However, towards the end of the process, we observed a positive evolution of both the task-based and relationship-based trust (Meyer, Citation2015) due to the institutions’ non-direct involvement approach, but also due to the trust gained and fostered by the facilitators.

As mentioned above, the latter proved essential in establishing a shared ‘language’ between the co-creators, the landscape architects, the engineers, and the experts. The shared language acted as an “invisible operational mortar” (McKenna, Citation2021) that helped cross boundaries and strengthened the relationships, communication and mutual understanding among stakeholders. In line with Whitehouse et al. (Citation2021), we observed that the shared language shapes and is shaped throughout the transdisciplinary co-creation process. Again, the facilitators proved essential by moulding the process to give it more freedom or to restrict it.

Political Capital

As Ansell and Torfing (Citation2021) mention, resource asymmetries in co-creation processes are ubiquitous, due to the diverse stakeholders involved (Leino & Puumala, Citation2021). In our study we recognized this asymmetry, especially in the beginning with respect to the role of the governmental bodies in the process. However, we focused in our study on capacity building by mobilizing and sharing multiple resources (Ansell & Torfing, Citation2021; Steen & Van Bueren, Citation2017), leading to the creation of new resources and the enhancement of planning capacity. Our case shows that especially combining financial resources brings tensions as certain stakeholders wanted their financial contributions to be used exclusively for tasks related to their specific domain. This ‘silo’ thinking appeared very strong in the case. To facilitate this more attention could be paid to the initial joint agreements regarding (financial) contributions and especially the degree of freedom in resource silos because creativity needs possibilities to cross borders. Another possibility could be the initiators’ direct involvement in the co-creation to gain a better sense of ownership of the process and its outcomes. However, the direct involvement of the initiators in the co-creation process could enhance power asymmetries which may lead to challenges concerning trust. Having thought about these challenges, the initiators in the studied case choose not to be a part of the co-creation process but only to act as orchestrators from a ‘distance’, whilst keeping in touch by delivering the project manager.

Creating a storyline proved an essential vehicle for making the different stakeholders get a comprehensive understanding of the problems and challenges involved, but also of the nature and aims of the co-creation process, which had to “set limits on what practices and solutions are deemed to be suitable and reasonable” (Lovell et al., Citation2009, p. 93). This proved challenging because making the process pre-conditions too strict would be an overkill for creativity, whilst too much freedom could lead to irrelevant and unrealistic results. Further, by aiming to streamline the objectives of different stakeholders with vested interests in different policy areas, the storyline and the process respectively lacked clarity on whether these preconditions were strict or not, thus leading to confusion and controversies.

A key role in strengthening the political capital was played by the Province’s project manager, who acted as a change agent by initiating, contributing to and supporting the adoption of a co-creation approach for the Hegewarren polder. She acted as a change agent because she knew the challenges the area faced and the planning process’s subtleties and had connections with different stakeholders and decision-makers that proved helpful. She also acted as an initiator (Goudswaard & van Oosten, Citation2022) by opting for a co-creative approach. Whereas the initiative and dedication of the project manager proved to be critical for the success of the co-creation process, the entire trajectory is critically linked to the support of the political actors. In line with the observations of Bonvillian and Weiss (Citation2015), the politicians representing the initiating institutions acted as ‘meta-change agents’ by supporting the process through their collective decision to search for “the socially most optimal layout of the area” (Eindrapport co-creatieproces Hegewarren, Citation2021, p. 21). This reflects Lunenburg’s (Citation2010) conclusions, who noticed that “the success of any change effort depends heavily on the quality and workability of the relationship between the change agent and the key decision makers within the organisation” (p. 5).

Conclusions

In the field of spatial planning, there is abundant literature that advocates for a shift towards theoretical and practical approaches focused on integration, collaboration and adaptiveness. In support of this paradigm shift, this paper aimed to take one step further and explore whether and how co-creation, as a collaborative planning approach, may contribute to building institutional capacity. Our findings show that the co-creation process strengthened each of the three types of capital (see ). Another important finding of the study is that the different capitals influence each other. For example, higher levels of trust among the different actors involved in the co-creation process make them more willing to exchange information and knowledge, thus leading to the co-creation of new knowledge. Thus, social capital plays a key role in the exchange and combination of intellectual capital, and may contribute to the creation of new intellectual capital. At the same time, the interaction and exchange of intellectual capital help to create and sustain social capital. This mutual relationship between the intellectual and social capital also appears from the interpretation of the ‘co-creation’ term in which the ‘co’ element refers to the stakeholders involved and their mutual relationships, i.e., the social capital, and the ‘creation’ element refers to knowledge creation, and, thus, to the intellectual capital.

This study shows that despite the attractiveness of collaborative planning approaches regarding the building of intellectual, social and political capital, the adoption of a co-creative approach in the (spatial) planning practice proved challenging. Therefore, beyond the academic-oriented insights, by using the Hegewarren polder as an example, we use our findings to point to some key elements that can contribute to the curation of a co-creation process and thus support the building of planning capacity. First, the preparations must allow for flexibility and adaptation as co-creation has been shown to be an iterative process, which cannot be completely pre-arranged. Second, in co-creation processes, the change agents are essential as they initiate, contribute and support the adoption of experimental approaches. Third, given the diversity of stakeholders involved in spatial planning co-creation processes, the facilitators and landscape architects are essential for integrating different perspectives, interests and types of knowledge, building trust, and facilitating the creation of a shared language that ultimately allows the stakeholders to communicate and build a shared vision. Fourth, trust is built and evolves throughout the co-creation process, either through business-related activities or through social activities, depending on the cultural context in which the process takes place. Fifth, all-encompassing storylines are an essential vehicle for helping the different stakeholders to get a comprehensive understanding of the problems and challenges involved, but also of the nature and aims of the co-creation process. Lastly, it is important to prepare a balanced set of pre-conditions that can trigger the development of creative responses that fit well with the requirements derived from the problem definition, thus increasing the chances of the newly developed responses to be validated through the decision-making process. Fortunately, despite challenges stemming from the configuration of the pre-conditions set, in the Hegewarren case, at the end of September 2022, the decision-makers opted to go forward with one of the co-created scenarios. The subsequent planning phase is currently conducted co-creatively, thus using the already-built capitals and further enhancing the capacities of each stakeholder.

In addition to the practice-oriented findings related to the co-creation process, our research also contributes to the planning theory by adding an analytical framework (see ) to the existing body of knowledge. By bringing the literature about institutional capacity and intellectual, social and political capitals together with the one about co-creation, this framework opens up the opportunity to conduct further research on co-creation and capacity building in other fields and in different geographical contexts.

To conclude, co-creation is a process in which new knowledge is created by exchanging and combining local and expert knowledge. A process through which new relations are developed based on trust building and sharing of visions and values. And a process through which the capacity to act collectively is enhanced due to the joint mobilization of resources and the creation of a sense of ownership of the process and its outcomes. As this article has only briefly elaborated upon the resource and stakeholder asymmetries, we invite academics and practitioners to investigate issues of differences in resources and power and their influence on capacity building within a co-creation process in practice. Further, our exploratory study may provide a starting point for further research of the conditions needed to ensure ‘a safe landing’ of the results from a co-creation process in the decision-making phase. A final research avenue worth exploring is how co-creation may lead to new perspectives about the planning processes needed to collaboratively tackle the great challenges our society is facing.

Acknowledgements

The author(s) would like to thank the Province of Friesland for providing access to the Hegewarren case, to the interviewees for participating in this research, and to Reinder Boomsma for his assistance with interviews in the Frisian language.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest is reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Maria Alina Rădulescu

Maria Alina Rădulescu is a PhD candidate at the Faculty of Spatial Sciences of the University of Groningen. She is also a researcher at the Energy Law Section of the Faculty of Law from the University of Groningen, where she conducts research in the field of public participation in environmental and energy matters.

Wim Leendertse

Wim Leendertse works as a senior advisor at Rijkswaterstaat, the executive organization of the Dutch Ministry of Infrastructure and Water Management. He is also part-time professor Management in Infrastructure Planning at the University of Groningen at the Faculty of Spatial Sciences, department of Planning.

Jos Arts

Jos Arts is professor Environment and Infrastructure Planning, University of Groningen, The Netherlands. He is also extraordinary professor at the Unit Environmental Sciences & Management, North West University, Potchefstroom, South-Africa. His research focuses on institutional analysis and design for integrated planning approaches for sustainable infrastructure networks.

References

- Acharya, C., Ojha, D., Gokhale, R., & Patel, P. C. (2022). Managing information for innovation using knowledge integration capability: The role of boundary spanning objects. International Journal of Information Management, 62, 102438. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2021.102438

- Akhilesh, K. B. (2017). Co-creation and learning. Springer India.

- Ansell, C., & Gash, A. (2007). Collaborative governance in theory and practice. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 18(4), 543–571. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mum032

- Ansell, C., & Torfing, J. (2021). Public governance as co-creation: A strategy for revitalizing the public sector and rejuvenating democracy (1st ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Arnstein, S. R. (1969). A ladder of citizeA participation. Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 35(4), 216–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944366908977225

- Battilana, J., & Casciaro, T. (2012). Change agents, networks, and institutions: A contingency theory of organizational change. Academy of Management Journal, 55(2), 381–398. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2009.0891

- Bonvillian, W. B., & Weiss, C. (2015). Technological innovation in legacy sectors. Oxford University Press.

- Bourdieu, P. (1986). The forms of capital. In J. G. Richardson (Ed.), Handbook of theory and research for the sociology of education (pp. 241–258). Greenwood Press.

- Bryson, J. M., Crosby, B. C., & Stone, M. M. (2006). The design and implementation of cross-sector collaborations: Propositions from the literature. Public Administration Review, 66(s1), 44–55. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2006.00665.x

- Byskov, M. F. (2020). Four challenges to knowledge integration for development and the role of philosophy in addressing them. Journal of Global Ethics, 16(3), 262–282. https://doi.org/10.1080/17449626.2020.1858324

- Cars, G., Healey, P., Madanipour, A., & de Magalhães, C. S. (Eds.). (2017). Urban governance, institutional capacity and social milieux. Routledge.

- Edelenbos, J., van Buuren, A., & van Schie, N. (2011). Co-producing knowledge: Joint knowledge production between experts, bureaucrats and stakeholders in Dutch water management projects. Environmental Science & Policy, 14(6), 675–684. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2011.04.004

- Eindrapport co-creatieproces Hegewarren. (2021). https://toekomsthegewarren.frl/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/20211221_Rapportage_co-creatie_Hegewarren_DEF_lowres.pdf

- Flyvbjerg, B. (2001). Making social science matter: Why social inquiry fails and how it can succeed again (S. Sampson, Trans.; 1st ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Goudswaard, T., & van Oosten, J. (2022). Maakkracht: Een nieuwe benadering voor complexe vraagstukken. Uitgeverij Business Contact.

- Haataja, M., Hautamäki, A., Holm, E., Pulkkinen, K., & Suni, T. (2018). Co-creation a guide to enhancing the collaboration between universities and companies (978-951-51-4096–8). University of Helsinki.

- Hagman, K., Hirvikoski, T., Wollstén, P., & Äyväri, A. (2018). Handbook for co-creation. Theseus. https://www.theseus.fi/handle/10024/159825

- Hajer, M. A. (1997). The politics of environmental discourse: Ecological modernization and the policy process (1st ed.). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/019829333X.001.0001

- Hajer, M. A. (2005). Rebuilding ground zero. The politics of performance. Planning Theory & Practice, 6(4), 445–464. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649350500349623

- Hartley, J., Sørensen, E., & Torfing, J. (2013). Collaborative innovation: A viable alternative to market competition and organizational entrepreneurship. Public Administration Review, 73(6), 821–830. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12136

- Healey, P. (2006). Collaborative planning: Shaping places in fragmented societies (2nd ed.). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hedlund, G. (1999). The intensity and extensity of knowledge and the multinational corporation as a nearly recomposable system (NRS). MIR: Management International Review, 39(1), 5–44. WorldCat.org

- Heikkinen, M. T., Mainela, T., Still, J., & Tähtinen, J. (2007). Roles for managing in mobile service development nets. Industrial Marketing Management, 36(7), 909–925. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2007.05.014

- Hilbers, A. M., Sijtsma, F. J., Busscher, T., & Arts, J. (2022). Identifying citizens’ place values for integrated planning of road infrastructure projects. Tijdschrift voor Economische en Sociale Geografie, 113(1), 35–56. https://doi.org/10.1111/tesg.12487

- Johnson, S. A., & Romanello, M. L. (2005). Generational diversity: Teaching and learning approaches. Nurse Educator, 30(5), 212–216. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006223-200509000-00009

- Kemp, R., Parto, S., & Gibson, R. B. (2005). Governance for sustainable development: Moving from theory to practice. International Journal of Sustainable Development, 8(1/2), 12. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJSD.2005.007372

- Khakee, A. (2002). Assessing institutional capital building in a local agenda 21 process in Göteborg. Planning Theory & Practice, 3(1), 53–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649350220117807

- Kogut, B., & Zander, U. (1992). Knowledge of the firm, combinative capabilities, and the replication of technology. Organization Science, 3(3), 383–397. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.3.3.383

- Kurtzberg, T. R., & Amabile, T. M. (2001). From Guilford to creative synergy: Opening the black box of team-level creativity. Creativity Research Journal, 13(3-4), 285–294. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15326934CRJ1334_06

- Kyttä, M., Broberg, A., Tzoulas, T., & Snabb, K. (2013). Towards contextually sensitive urban densification: Location-based softGIS knowledge revealing perceived residential environmental quality. Landscape and Urban Planning, 113, 30–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2013.01.008

- Laine, M., Leino, H., & Santaoja, M. (2022). Building citizens’ trust in urban infill: A dynamic approach. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 42(3), 294–304. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X18817089

- Leino, H., & Puumala, E. (2021). What can co-creation do for the citizens? Applying co-creation for the promotion of participation in cities. Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space, 39(4), 781–799. https://doi.org/10.1177/2399654420957337

- Lovell, H., Bulkeley, H., & Owens, S. (2009). Converging agendas? Energy and climate change policies in the UK. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 27(1), 90–109. https://doi.org/10.1068/c0797j

- Lunenburg, F. C. (2010). Managing change: The role of the change agent. International Journal of Management, Business and Administration, 13(1), 1–6.

- Mangelsdorf, M. E. (2018). The trouble with homogeneous teams. MIT Sloan Management Review, 59(2), 43–47.

- McKenna, C. J. (2021). An invisible operational mortar: The essential role of speech acts within tri-segregated moviegoing. AILA Review, 34(1), 102–121. https://doi.org/10.1075/aila.20010.mck

- Meyer, E. (2015). The culture map: Decoding how people think, lead, and get things done across cultures (International ed.). PublicAffairs.

- Möllering, G. (2008). Inviting or avoiding deception through trust? Conceptual exploration of an ambivalent relationship (MPIfG Working Paper 08/1). https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1105060

- Nahapiet, J., & Ghoshal, S. (1998). Social capital, intellectual capital, and the organizational advantage. The Academy of Management Review, 23(2), 242. https://doi.org/10.2307/259373

- Nyström, A.-G., Leminen, S., Westerlund, M., & Kortelainen, M. (2014). Actor roles and role patterns influencing innovation in living labs. Industrial Marketing Management, 43(3), 483–495. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2013.12.016

- Polk, M. (2011). Institutional capacity-building in urban planning and policy-making for sustainable development: Success or failure? Planning Practice and Research, 26(2), 185–206. https://doi.org/10.1080/02697459.2011.560461

- Prahalad, C. K., & Ramaswamy, V. (2004). Co-creation experiences: The next practice in value creation. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 18(3), 5–14. https://doi.org/10.1002/dir.20015

- Puerari, E., de Koning, J., von Wirth, T., Karré, P., Mulder, I., & Loorbach, D. (2018). Co-creation dynamics in urban living labs. Sustainability, 10(6), 1893. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10061893

- Putnam, R. D. (1995). Bowling alone: America’s declining social capital. Journal of Democracy, 6(1), 65–78. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.1995.0002

- Rădulescu, M. A., Leendertse, W., & Arts, J. (2020). Conditions for co-creation in infrastructure projects: Experiences from the Overdiepse polder project (The Netherlands). Sustainability, 12(18), 7736. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187736

- Rădulescu, M. A., Leendertse, W., & Arts, J. (2022). Living labs: A creative and collaborative planning approach. In A. Franklin (Ed.), Co-creativity and engaged scholarship (pp. 457–491). Springer International Publishing.

- Reagans, R. (2011). Close encounters: Analyzing how social similarity and propinquity contribute to strong network connections. Organization Science, 22(4), 835–849. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1100.0587

- Rill, B. R., & Hämäläinen, M. M. (2018). The art of co-creation: A guidebook for practitioners. Springer Singapore.

- Rotmans, J., & Verheijden, M. (2021). Omarm de chaos (4e druk). De Geus.

- Schulenkorf, N. (2010). The roles and responsibilities of a change agent in sport event development projects. Sport Management Review, 13(2), 118–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2009.05.001

- Som, D. L. (2014). The capitals of nations: The role of human, social, and institutional capital in economic evolution. Oxford University Press.

- Steen, K., & Van Bueren, E. (2017). Urban living labs a living lab way of working. Amsterdam Institute for Advanced Metropolitan Solutions (AMS).

- Swain, C., & Tait, M. (2007). The crisis of trust and planning. Planning Theory & Practice, 8(2), 229–247. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649350701324458

- Szreter, S., & Woolcock, M. (2004). Health by association? Social capital, social theory, and the political economy of public health. International Journal of Epidemiology, 33(4), 650–667. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyh013

- Torfing, J., Ferlie, E., Jukić, T., & Ongaro, E. (2021). A theoretical framework for studying the co-creation of innovative solutions and public value. Policy & Politics, 49(2), 189–209. https://doi.org/10.1332/030557321X16108172803520

- Van Buuren, A., & Edelenbos, J. (2004). Why is joint knowledge production such a problem? Science and Public Policy, 31(4), 289–299. https://doi.org/10.3152/147154304781779967

- Vangen, S., & Huxham, C. (2003). Nurturing collaborative relations: Building trust in interorganizational collaboration. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 39(1), 5–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021886303039001001

- Verhoeven, D. (2021). Knowledge diversity in teams and innovation (Working Paper). https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3795476

- Voorberg, W. H., Bekkers, V. J. J. M., & Tummers, L. G. (2015). A systematic review of co-creation and co-production: Embarking on the social innovation journey. Public Management Review, 17(9), 1333–1357. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2014.930505

- Whitehouse, M., Rahm, H., Wozniak, S., Breunig, S., De Nardi, G., Dionne, F., Fujio, M., Graf, E.-M., Matic, I., McKenna, C. J., Steiner, F., & Sviķe, S. (2021). Developing shared languages: The fundamentals of mutual learning and problem solving in transdisciplinary collaboration. AILA Review, 34(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1075/aila.00038.int

- Williams, M. (2016). Being trusted: How team generational age diversity promotes and undermines trust in cross-boundary relationships: Does team generational diversity influence dyadic trust? Journal of Organizational Behavior, 37(3), 346–373. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2045

Appendices

Appendix 1. Composition of the co-creation team.

Appendix 2. Timeline of the co-creation process.

Appendix 3. Secondary data.

Appendix 4. List of observed meetings, sessions and workshops.

Appendix 5. List of interviews.