Abstract

In 2019–21, research was carried out at the University of Helsinki regarding the development of the degree programme in maritime archaeology. To develop the teaching of the programme, we designed and launched an online learning platform. The platform, entitled ‘Perspectives in Maritime Archaeology’, consists of lectures by international experts and literature on a variety of topics ranging from boatbuilding to seamanship and from trade and exploration to public outreach and contemporary art. The purpose of the platform was to convey a broad image of the discipline and promote multidisciplinary thinking among students. To assess the success of the platform in achieving this objective, we conducted surveys on student expectations and satisfaction as well as on (potential) changes in the perceived image of maritime archaeology. We discovered that a kaleidoscopic and eclectic approach to teaching maritime archaeology online made the topic more interesting to the students and helped them understand the variety and importance of different approaches to researching maritime archaeology. In this article, we report the findings of our research on the development of online learning and discuss them in the wider context of higher education in maritime archaeology. We conclude with a reflection on the potential use of poetry and metaphor in teaching holistically about the cognitive and cultural relevance of water.

Introduction: Towards an integrated approach to teaching maritime archaeology

Between 2019 and 2021, two interconnected research projects were carried out by the authors at the University of Helsinki. The first one assessed the history of teaching maritime archaeology globally and in Finland in order to gain insights into what factors contribute to the long-term success of degree programmes in maritime archaeology (Marila & Ilves, Citation2020). The second project consisted of the practical implementation of the results of the first project, culminating in the launch of an introductory online course in maritime archaeology for the academic year 2021–22. The resulting asynchronous online learning experience, entitled Perspectives in Maritime Archaeology (hereinafter PiMA), consists of a large collection of lectures and other types of contributions, such as discussions, tours and artwork on various topics by close to forty Finnish and international experts. The motivation for developing the course was the fact that, in the popular imagination, maritime archaeology is understood mainly as the study of underwater wrecks (Gately & Benjamin, Citation2018; Ilves, et al., Citation2022). In Finland, this rather simplistic image is at least partly also reflected in actual published research, which is dominated by the study of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century shipwrecks (Ilves & Marila, Citation2021). This focus has led to severe thematic, chronological, and geographical gaps in the research. As a result, the maritime cultural heritage of lake, riverine, and wetland settings in particular and the maritime cultural landscape in general is under-represented in both research and teaching (see also Marila & Ilves, Citation2021). To mitigate the effects of maritime archaeology’s thematic streamlining, and as a way of developing more varied research in the future, it is extremely important that a broad understanding of the discipline is communicated to new students. In turn, this will also contribute to a more nuanced perception of maritime archaeology among the general public.

To provide university students with a holistic and multidisciplinary understanding of the scope of the theories, methods, and approaches used in maritime archaeology, we designed the course to be a kaleidoscope of different research orientations. The PiMA platform, therefore, includes eleven thematic sections, each of which contains lectures of different lengths produced specifically for the course, as well as relevant literature and links to outside sources:

Development of vessel types

Boatbuilding

Life on board

Navigation and exploration

Maritime trade

Lifeways

Worldviews

Maritime heritages

Conservation and documentation

Public outreach

Maritime archaeology and contemporary art

In our opinion, this scope of topics best reflects the so-called integrated approach to maritime archaeology. By integration, we are referring to a definition of maritime archaeology as archaeology but also as a historical development process that has taken place in maritime archaeology during the last forty-five or so years. This development process is marked by discussions on the theoretical and methodological identity of the discipline as well as its thematic scope both in terms of research and teaching. Insofar as the technological development of more easily accessible diving equipment has led to increasing research activity under water, and the separation of maritime archaeology from archaeology at large — manifested in the professionalization of ‘underwater archaeology’ — we also see the attempts to reintegrate underwater and maritime archaeology with archaeology at large as crucial steps in the development of teaching (see also Ilves & Marila, Citation2021; Marila & Ilves, Citationforthcoming).

In addition to the key integrationist work initiated and carried out by Keith Muckelroy (Citation1978), Richard Gould (Citation1983), Christer Westerdahl (Citation1992) and Seán McGrail (Citation1995; Citation1997; see also Ward, Citation2003), equally important was the establishment of the Journal of Maritime Archaeology (JMA) in 2006 to serve as a platform for reflecting on the disciplinary identity of maritime archaeology. JMA quickly came to serve as a venue for discussing more explicitly theoretical approaches as well as topics related to higher education in maritime archaeology. The views put forward in a special thematic issue of JMA (Ransley, Citation2008) on teaching and training in maritime archaeology reflect the multitude of different ways in which higher education in underwater and maritime archaeology can be planned and implemented. Should, for example, field skills be emphasized over academic reflection? What is the role of scientific societies in the transfer of skills? To what extent should private companies, rather than universities, be responsible for providing their employees with the often highly specific technical skill needed in the field?

Antony Firth’s (Citation2008: 126) statement that ‘there is no formula for education in maritime archaeology’ sums up the variety of opinions expressed in that thematic issue, but the sentiment is also reflected in the results of our research into what constitutes successful teaching. We have found that when it comes to the attractiveness and viability of a degree programme in maritime archaeology, it makes no difference whether the programme concentrates on teaching academic research skills or field techniques (Marila & Ilves, Citation2020). More important for the long-term viability of teaching maritime archaeology, be it individual courses, modules, or complete degree programmes, is the integration of that teaching with existing teaching in other disciplines, such as archaeology, cultural heritage studies, history, ethnology, and biology, to name a few (see also Marila & Ilves, Citationforthcoming). Due to the relatively small size and short history of stand-alone maritime archaeology degree programmes, especially in Europe, they are easy targets for budget cuts and layoffs, especially during organizational restructuring (Marila & Ilves, Citation2020). By closely integrating them with existing teaching, it is therefore possible to increase not only the viability of teaching maritime archaeology but, through strengthening the ties with other disciplines in a way that promotes multidisciplinarity, also the relevance of the teaching for academia, heritage management, and the practice sector.

In what follows, we present the PiMA online course from its inception to its design, technical execution, and implementation in teaching. We also reveal the results of pre- and post-course student surveys conducted to measure and evaluate the impact of the online course. Finally, as a practical way forward in teaching maritime archaeology as kaleidoscopic and reflexive, we discuss two of the eleven course themes, ‘Worldviews’ and ‘Maritime archaeology and contemporary art’. In particular, we offer a perspective on the use of poetry and metaphor as tools in teaching students about the importance of water and the maritime environment for human cognition and culture.

Perspectives in Maritime Archaeology: Online learning experience

In the summer of 2020, with financial aid from the Weisell Foundation, we began designing an online course with the intent that it would function as an introduction to a module in maritime archaeology that is offered at the University of Helsinki’s Department of Cultures. We wanted the course to include basic studies-level lectures on a variety of topics, but, to ensure that they retain a connection to maritime archaeology, we envisaged the narrative of the course as the biography or itinerary of a ship from construction to use, from the ship’s role as a social arena and means of transportation to the ship’s conservation and scientific research, and from the role and relevance of the ship in human cognition and cosmology to the ship as a complete metaphor for humans’ interaction with water.

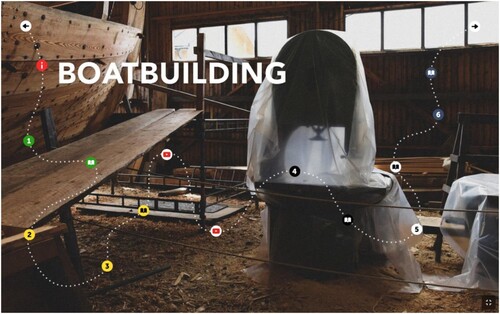

To technically execute the course, we utilized ThingLink, an interactive digital multimedia platform that allows the user to add tags to images and videos. The tags can include text and visuals, or they can be links to content outside ThingLink, allowing the designer to draw the user’s attention to or provide information on an element in the image or video. ThingLink also offers users the possibility to create tours consisting of multiple images or videos. In our case, the flexibility and interactivity of the platform allowed for a game-like design of the PiMA platform. On the PiMA platform, the student proceeds along a marked path reminiscent of a board game interface or the route of a ship (). Along the path, the student clicks on icons that open with a lecture linked to the course’s YouTube channel, references to literature or a link to other content, such as a museum website or historical archives.

Figure 1 Screen capture of one of the eleven thematic pages from the Perspectives in Maritime Archaeology online course. ThingLink was used for the technical execution of the online course. Clickable buttons with text, links, and documents can be added onto the images and videos. The visual appearance of the course platform resembles a board game or the itinerary of a ship (photo: Marko Mikael Marila).

The tour function of ThingLink was used to transition between the thematic pages on the platform, and to create, for instance, a guide to the underwater and maritime cultural heritage of the eighteenth-century island fortress of Suomenlinna in Finland. In practice, the student could walk around Suomenlinna, visit a heritage site marked on the ThingLink tour, and open a short video explaining its history.

The eleven thematic pages on the platform include seventy-five lectures (between four and eight lectures per theme) produced specifically for the course. The total length of recorded teaching on the course platform is approximately 17 hours, whereas the total length of lectures on the individual thematic pages ranges from 30 minutes to 2.5 hours. The length and format of the individual lectures vary from short, one-minute informational or atmospheric videos to full one-hour lectures, discussions, and interviews. The lectures are complemented with literature references provided by the lecturers as well as with links to videos and websites outside the course platform. In addition to the thematic pages, the platform includes an introduction page with a welcoming address and instructions on navigating the site as well as a concluding assignment page with instructions on coursework. The language of the course platform is English, and most lectures are in English, but some are also in Finnish and Swedish. All lectures in Finnish and Swedish have been professionally subtitled in English.

In terms of their thematic scope, the lectures deal with sites, materials, and methods from the Stone Age to the recent past. From a geographical standpoint, the lectures include sites and materials mainly from the Baltic Sea region, but also from the larger Scandinavian and European area, the Mediterranean, South-East Asia, and North America. The eleven sections have some unavoidable thematic overlap, and some lectures could easily have found a place on more than one thematic page. This was communicated to the students at the beginning of the course, as was the fact that none of the lectures aim at providing an in-depth account of their respective topic, but instead are supposed to serve as an example of an approach among a kaleidoscope of perspectives.

As pertains to the selection and contents of the lectures within a single section, ‘Public outreach’, for example, includes a lecture on popular science and the dissemination of research results to a wider audience in international settings, a tour of the Finnish Heritage Agency Collections and Conservation Centre, links to 3D models of shipwrecks, a presentation of the Maritime Archaeological Society of Finland, a video presentation about diving in a Finnish wreck park with interviews with hobby divers, links to Finnish diving club’s websites and maritime museums, and academic literature on community archaeology, public outreach, and accessibility in Finnish and international contexts. The total runtime of the video footage in this section is 119 minutes.

Reception of the course

During the fall term 2021, the Perspectives in Maritime Archaeology asynchronous online course was introduced to students at the University of Helsinki, including the Open University and the University of Turku; it was listed as a five European Credit Transfer and Accumulation System (ECTS) credit online-only course for participants in Helsinki and as a ten ECTS credit hybrid course for participants in Turku. To assess the impact of the course, the participants were also required to take part in pre- and post-course electronic surveys. We designed the pre-course survey to compare certain demographic characteristics and clarify students’ existing perceptions of maritime archaeology as well as their motivations for enrolling in the course. The post-course survey contained questions that addressed students’ perceptions of both online learning and the scope of maritime archaeology.

Pre-course survey

In total, 47 students registered for the course: 24 students from the University of Helsinki and nine from the University of Turku, while 14 participants joined the course through the Open University at the University of Helsinki. In addition, we approached our colleagues actively working in archaeology, both in academia and beyond, in Finland and abroad, none of them maritime archaeologists, to act as a reference group: 11 archaeologists with a degree and work experience in archaeology registered. Thus, altogether 58 participants enrolled in the course.

The pre-course survey consisted of nine items, most of which were multiple-choice questions connected to the demographics and prior training of the participants, while one open-ended question addressed their perceptions of maritime archaeology. Among the registered participants, 29 identified themselves as female, 29 as male, and none as non-binary. Much of the group, 36% (n = 21), fell within the age range of 19–29 years, followed by 26% (n = 15) in the 30–39 age range, and 22% (n = 13) in the 40–49 age range; 9% (n = 5) and 7% (n = 4) belonged in the 50–59 and 60 or above age range, respectively. Most of the older learners, seven out of nine, enrolled through the Open University. Over half of the participants (n = 38) were beginners in terms of their experience in archaeology, while 11 participants in the reference group had years of experience working in archaeological field and the rest, nine participants, had some experience in archaeology.

All but one of the student participants enrolled in the course with the aim of learning about archaeology, but many (n = 23) also mentioned gaining study credits as an objective, which was the main motivator for the one student not opting to choose learning about archaeology among the stated goals. In addition, 11 participants, five of whom were in the reference group, chose entertainment as an aim (as well). Six participants chose all three goals as the reason for taking the course, while no one chose the ‘no idea’ option as a response to the question. Most of the participants, 86% (n = 50), had taken prior online courses and 74% estimated their IT skills as average (n = 21) or above average (n = 23). Only one of the participants, from the Open University, deemed their IT skills as poor, while 14 judged their IT skills to be excellent.

To allow participants to elaborate on their perceptions of maritime archaeology, we added an open-ended question to the survey enquiring about what comes to mind (in one word or a few sentences) when they hear the words ‘maritime archaeology’. The responses submitted were divided into four categories:

Maritime archaeology associated with the underwater environment, activities, and/or shipwrecks (‘Underwater archaeological research’, ‘Water, diving, and shipwrecks’, ‘Study of underwater lost artefacts (sunken ships and cities) for the purpose of understanding the life of our ancestors’)

Maritime archaeology defined holistically (‘Archaeological study that has to do with people’s actions in relation to water and/or in the context of water, or vice versa’, ‘Water affecting the actions of people’, ‘Studying the human material culture of the past that is related to different bodies of water or activities connected to water’)

Maritime archaeology connected to a particular event, site, or person (‘Maritime archaeology lecture on another course I completed’, ‘The battle of Svensksund’, ‘I would like to pursue a career as a research diver and so this seems interesting’)

Maritime archaeology as something else (‘Something that I know almost nothing about’, ‘Sounds very interesting, I would like to learn more’, ‘Marinescape’)

The responses connecting maritime archaeology with a particular event, site, or person and with something else apply to 16% (n = 9) and 7% (n = 4) of the participants, respectively. The most noteworthy aspect among the responses was the fact that four replies out of nine categorized as being associated with an event, site, or person reflected the participants’ passion for maritime archaeology and related to it being a desired future career rather than an aim to associate the discipline with a certain type of source material or a method. Not surprisingly, however, especially considering the typical stereotypes of maritime archaeology, the perceptions of many participants (21%, n = 21) still clearly connected maritime archaeology to the underwater environment, activities, and/or shipwrecks. Yet, an even larger number of enrolled participants, 41% (n = 24), had a more holistic understanding of maritime archaeology.

The breakdown of the data related to a holistic understanding of the discipline demonstrated some noteworthy aspects. Sixty-four per cent (n = 7) of participants in the reference group defined maritime archaeology broadly, while 29% (n = 4) of those from the Open University and 54% (n = 24) of those from the University of Helsinki did so. None of the nine registered students at the University of Turku suggested an integrated understanding of maritime archaeology in their responses. This may be partly explained by the fact that maritime archaeology has not been taught at the University of Turku since 2012, and most enrolled students in Turku were not archaeology students, but instead majoring in landscape or cultural heritage studies. On the other hand, we are inclined to explain the large number of students at the University of Helsinki relating maritime archaeology to the broader archaeological study of the past with the fact that the teaching of maritime archaeology at the University of Helsinki has always aimed to convey a very broad understanding of the discipline (Marila & Ilves, Citationforthcoming). Many students enrolling in the course at the University of Helsinki had already participated in some maritime archaeological lectures. Their responses reflect a holistic and integrationist understanding of the discipline, perfectly illustrated by a quote from one of the registered students: ‘I guess maritime archaeology for me (as for many people) used to be synonymous with diving and underwater archaeology. However, I’ve since learned it also pertains to much more. Maybe the first thing it brings to mind now is the sea/water as a connecting medium for much of human history’.

Post-course survey

The course was completed by 44 participants, 20 females and 24 males: 18 from the University of Helsinki, five from the University of Turku, 12 from Open University, and nine archaeologists in the reference group. The proportionally larger drop-out rate among students from the University of Turku was most likely connected to the higher workload and the time investment needed to complete the ten ECTS credit course.

The post-course survey consisted of 17 items and made extensive use of a five-point Likert scale (1 strongly disagree/poor to 5 strongly agree/excellent), but also open- and close-ended as well as dichotomous (yes/no) and multiple-choice questions. The post-course survey focused on the participants’ experiences with the online learning platform, its contents, and the set up of the course, as well as their perceptions of maritime archaeology.

Forty-eight per cent (n = 21) and 41% (n = 18) of participants, respectively, rated their overall experiences with the online platform as excellent or very good, while five participants assessed their experience as good. While an equal number of participants (43%, n = 19 in both cases) rated the user friendliness of the platform as excellent or very good and 66% (n = 29) of the participants deemed the chosen visual language of the platform excellent, only 32% (n = 14) assessed the visual execution as being very good and one participant rated it as just good. Thus, the post-course survey shows that students generally appreciated the chosen platform, and their open-ended responses likewise praised the usability of the platform: ‘It is very good for this kind of a course. Much, much better than the platforms on Moodle or MOOC’; ‘Really fluid, I was surprised’; and ‘I like a lot when people focus on functionality and the content instead of showing off all possible gadgets, bells and whistles one can add to an application’.

The course made use of both long and short lectures, providing additional readings for the participants as well as some extra material (links to websites and 3D models, for example). When it comes to the setup of the course, 68% (n = 30) of the participants felt that the length of the lecture did not play a role, while 18% (n = 8) found short lectures most interesting, and 14% (n = 6) found long lectures most interesting. Eighty-six per cent (n = 38) of the participants considered the number of lectures appropriate, though 7% (n = 3) reported that the course either contained too many lectures or not enough lectures. The participants considered the suggested readings uniformly interesting and relevant, but 9% (n = 4) deemed the extra material not so interesting. In terms of their overall perceptions of online learning, 48% (n = 21) of the participants felt that the course worked well as a stand-alone course, while 46% (n = 20) felt that the course would benefit from some contact teaching and 7% (n = 3) that the course needs additional contact teaching: students at the Open University especially expressed a strong desire for more contact teaching. Complementary contact teaching was provided at all universities, but to varying degrees. In Turku, for example, the course included 20 hours of contact teaching, which partly contributed to the higher ten ECTS workload.

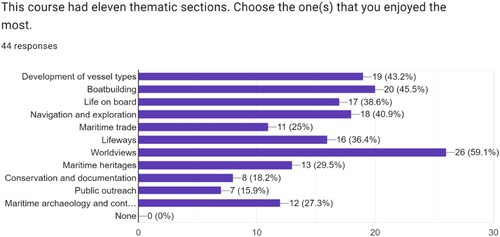

The course had eleven thematic sections, some more conventional than others. All but one of the participants either strongly agreed (52%, n = 23) or agreed (46%, n = 20) that the themes of the course complemented each other well. When asked to choose the themes that the participant enjoyed the most, several participants mentioned all themes as enjoyable, but nonetheless a certain pattern still emerged in the responses ().

Figure 2 Breakdown of the course’s themes based on the percentage of participants who found a particular theme especially enjoyable. The participants were allowed to choose one or more theme. ‘Worldviews’ was selected by 26 students as particularly stimulating.

The participants, 59% (n = 26), tended to appreciate the ‘Worldviews’ theme the most. Clearly distinct from the ‘Worldviews’ theme, though, the themes of ‘Boatbuilding’, ‘Development of vessel types’, ‘Navigation and exploration’, ‘Life on board’. and ‘Lifeways’ comprised a group appreciated by 16–20 participants (36–46%), while 11–13 participants (25–30%) chose the themes of ‘Maritime trade’, ‘Maritime heritages’, and ‘Maritime archaeology and contemporary art’. Moreover, seven (16%) and eight (18%) participants, respectively, appreciated the themes of ‘Public outreach’ and ‘Conservation and documentation’.

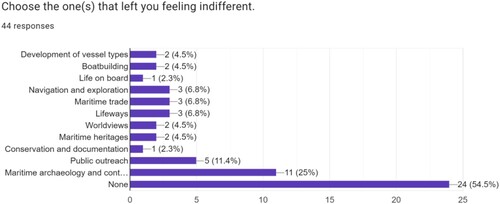

In terms of themes that left the participant feeling indifferent (), although they mentioned all themes, two themes can clearly be distinguished: ‘Public outreach’ left five participants (11%) feeling indifferent, while 11 participants (25%) mentioned ‘Maritime archaeology and contemporary art’. Regarding the ‘Maritime archaeology and contemporary art’ theme, participants from all groups marked this theme as leaving them indifferent: five from the University of Helsinki, four from the Open University, one from the University of Turku, and one from the reference group. Overall, most of the participants (n = 27) did not find any important topics missing from the contents of the course, with some offering the following praise: ‘Very diverse and I loved that there were so many people involved’; ‘The contents were varied and well-balanced’; and ‘The course was a tremendous package of nearly everything under the big umbrella of maritime archaeology. I enjoyed [it] and learned a lot’. However, the post-course survey nonetheless revealed that participants from the Open University (six out of 12), and especially the archaeologists in the reference group (seven out of nine), wanted additional themes that they felt would bring even more value to the course. Among the ‘missing themes’, several participants mentioned naval warfare and the theme of maritime landscapes, but also fieldwork principles and tools, both on the surface and underwater, as well as the specific theme of how to apply laboratory applications to maritime archaeological source material.

Figure 3 Breakdown of the course’s thematic sections that left the students feeling uninspired or indifferent. The participants were allowed to choose one or more theme. ‘Maritime archaeology and contemporary art’ stands out as a topic that divided the students into two distinct groups (see ). Importantly, more than half of the participants felt that none of the topics left them feeling indifferent.

Although a great number of participants had already acquired a holistic and integrationist understanding of maritime archaeology prior to the online course, something that the course explicitly strived to deliver, 63% (n = 28) strongly agreed and 27% (n = 12) agreed that this course helped them better understand maritime archaeology. Furthermore, 66% (n = 29) strongly agreed and 25% (n = 11) agreed that the course made maritime archaeology more interesting. Notably, the few participants who either reportedly disagreed with (n = 1) or felt neutral about (n = 3) having acquired a better understanding of the discipline, as well as those who disagreed with (n = 2) or felt neutral about (n = 2) the course having made maritime archaeology more interesting, were all students from the University of Helsinki. In conclusion, while 5% (n = 2) of the participants chose the neutral option, 61% (n = 27) and 34% (n = 15) strongly agreed or agreed that the course had fulfilled their initial expectations related to taking the course.

Mission accomplished?

Our aim in designing the Perspectives in Maritime Archaeology digital platform was to offer students a kaleidoscopic image of maritime archaeology as much more than just the study of underwater wrecks. We achieved this goal by including in the course curriculum lectures and other elements, such as other readings and links to sites with a wide thematic scope, ranging from boatbuilding to the cognitive elements of the maritime landscape and from the management of maritime heritage to popular science.

Perspectives in Maritime Archaeology was first launched at the University of Helsinki and University of Turku during the fall term of 2021. Altogether, 44 of the 58 registered students completed the course, comprising a good sample body for conducting pre- and post-course student surveys. Participant feedback showed that a very broad topic can be approached in a meaningful and intelligible manner and that the fragmentary nature of the course did not bother most students. The course helped the participants better understand maritime archaeology and made the discipline more interesting to them. One of the reasons why the students found the course interesting is likely due to the choice of the digital platform used for the course. ThingLink offers a very intuitive, engaging, and game-like user interface. This allowed us to design a predetermined study path or itinerary that the students could follow. Students found the platform engaging, fluid, and interesting, and they reported that the platform allowed them to concentrate on the course contents without distraction.

When designing the course, one of our concerns was that our decision to include lectures of different length and format on such a varied collection of topics might prove confusing for some students. However, according to the post-course follow-up survey, the great majority (97.8%) of the participants felt that the themes complemented each other quite well. Nevertheless, the theme of ‘Maritime archaeology and contemporary art’ stood out as a topic that divided the participants in terms of its appeal. Roughly 25% of the participants reported that the section left them feeling indifferent, whereas 27% of them rated it among the themes that they enjoyed the most. No other thematic section divided the responses so dramatically. These responses were most likely at least partly a reaction to how we communicated the relevance of each theme. The participant feedback made us realize that, while a kaleidoscopic approach contributed towards a more nuanced perception of the discipline, future iterations of the course will benefit from a clearer justification of the different approaches in the general context of maritime archaeology. This could be achieved, for instance, by including a section-specific introductory lecture.

In addition to introducing artistic approaches as examples of multidisciplinary research, the ‘Maritime archaeology and contemporary art’ section was also intended as an opportunity for students to reflect more generally on the metaphorical aspects of humans’ relationship with water and the centrality of the element to human culture. Furthermore, placed at the end of the course, the section was also an opportunity for participants to reflect on their own learning process. We chose contemporary art as a conceptual milieu that commonly uses metaphor to communicate those vague, embodied or affective aspects of human experience that are not easily disseminated through discursive means. In other words, we chose to use metaphor to denote an element of reflection that closely resembles the idea of metacognition, that is, the ability to step back and reflect on the learning process (for a survey of the many understandings of reflection in asynchronous online courses, see Rose, Citation2016).

Our intention was that the art section would differ sufficiently from those parts of the course that deal more directly and literally with the subject matter of maritime archaeology, and, therefore, that it would evoke an ‘allegorical impulse’ (Okonski & Gibbs, Citation2019) among students, prompting them to consider metaphor as a tool for reflection. In higher education, metaphor and metaphorization are commonly treated as an element that allows learners to achieve a heightened sense of engagement with their subject matter (e.g. Martínez, et al., Citation2001; Lee & Green, Citation2009; Lynch & Fisher-Ari, Citation2017) and increasingly also as a way to reconceptualize the research process in general (Alvesson & Sandberg, Citation2021). None of the PiMA participants took up the connection between metaphor and reflection in their course feedback, but it was discussed during some class meetings. Most students found the topic inspiring, which is why we will conclude with a more detailed discussion of the possible value of metaphor and metaphorization in the teaching of maritime archaeology.

Poetics of the sea: A postscript

As a postscript, and as a way of highlighting the importance of including elements in teaching that underscore the centrality of humans’ relationship with water, we want to elaborate and reflect on the potential of contemporary art toward that end. In particular, we do so by concentrating on the centrality of metaphor in poetry for a better understanding of water’s role in human cognition and culture. As a case in point on the poetic use of metaphors in teaching, we present and discuss an example derived from the ‘Maritime archaeology and contemporary art’ section of the PiMA platform.

The motivation for including a section on contemporary art in the course curriculum in the first place emanates from the field of art/archaeology and the fact that, due to the centrality of metaphor and other suggestive elements in it, art has become a way to challenge existing and established conceptions of the past as well as a way to assign importance to the many — often repressed — interpretations and representations of the past. It is striking that, while different combinations of archaeology and contemporary art have become numerous during the 2000s (Tilley, et al., Citation2000; Pearson & Shanks, Citation2001; Renfrew, Citation2003; Renfrew, et al., Citation2004; Russell & Cochrane, Citation2014; Chittock & Valdez-Tullet, Citation2016; Gheorghiu & Barth, Citation2019; Bailey, et al., Citation2020), similar examples of the use of contemporary art in the context of maritime archaeology are extremely rare. For this reason, when designing and implementing this thematic page of the course we reached out to artists whose art involves elements related to the maritime environment. Altogether, we included artworks by and interviews with American artist and archaeologist Jeffrey Benjamin and Finnish artists Tuula Närhinen, Pirjo Yli-Maunula, and Jaakko Niemelä. Elements of maritimity are present in their art in various forms, including maritime professions, maritime trade, maritime waste, wreckage and decay, but we focus here on a piece by Jeffrey Benjamin.

In the prose poem ‘Archipelogy’, Benjamin combines poetry with anthotype prints and photographs, focusing on the archipelagic environment as a locus for a host of metaphors that allow us to think about in-betweenness, ambivalence, and fluidity. Consider the metaphors used in the following passages of the poem (used with the artist’s permission):

The solution precedes the problem. The problem arises as soon as we have finished consuming the solution. I find no discourse on the land. The dry dust curls into the empty corners of silence of stone foundations. My mouth becomes heavy and I become mute. Speech is uncompensated manual labor, obligatory repetition of words, sentences, slogans, and phrases. To preserve the joy and musicality of speech we adopt the terseness of our ancestors.

Islands are good for thinking and feeling, even when they’re frozen, or perhaps especially so. Archipelogical thought is aphoristic thought, island hopping of the mind. And in between the waters, the currents, the motion, 99% boredom and 1% terror, as sailors will say. Gradations of light, veils of moisture, reflections in the sky, deflected clouds, a pulsating realm of mirage and illusion. Clouds. Islands cause one to think aphoristically, to look for nuance and subtlety. Archipelogy is an antidote to the tyranny of semiconductor thinking, the hegemony of the doped circuit, gateway thoughts, in or out, yes or no, on or off. Flashing screens, blinking lights and alarms, terrestrial sterility and poverty. On the island shoreline we rediscover chiaroscuro, blending of forms, changing, morphing. We find it in chlorophyll. And of course there will always be separation, boundaries, the mystery of existence, me doing stuff over here, other people doing stuff over there. To reverse Donne’s maxim, and quite thankfully, no island is a man. The solution, by definition, is fluid.

Since then, many have noticed the abundance and relevance of metaphors related to water and the maritime environment. In general, such metaphors have two main functions:

Metaphors that evoke ideas of fluidity expose the universality and centrality of the element to human cognition and culture, serving as a sort of conceptual common ground and embodied foundation for historical understanding and historical empathy (Tilley, Citation1999; Hillman, Citation2009; Steinberg, Citation2013; Costlow, et al., Citation2017; Lehtimäki, et al., Citation2018; Alonso-Población & Niehof, Citation2019; Killian & Rich, Citation2023). A case in point is the finding by Okonski and Gibbs (Citation2019) that, even when pushed toward a literal reading, people tend to interpret a poem through allegory. This ‘allegorical impulse’, Okonski and Gibbs (Citation2019) contend, allows humans to relate to the actions described in the language in a very bodily way, leading to a heightened sense of empathetic connection with others (see also Lakoff & Johnson, Citation1980).

Metaphors involving water and islands in particular allow us to be more reflexive about our research process, but they also encourage us to be more creative in imagining possible research avenues and novel research methodologies (Alvesson & Sandberg, 2021). Metaphors such as beachcombing, archipelago, island hopping, and drift can be particularly useful tools in imagining the multiplicity of methods relevant for historical research and education (Dening, Citation2002; Lawrenz & Huffman, Citation2002; Gates, Citation2010; Stratford, et al., Citation2011; Pétursdóttir & Olsen, Citation2018). The PiMA platform was designed as a form of island hopping, and it is through the metaphor of an archipelago that the students will hopefully be able to better grasp the connections between seemingly different and contrasting approaches. Furthermore, what the archipelago metaphor affords us is a sense of adventure and exploration but also an appreciation of the detours and ultimate dead-ends in the research and learning process.

In the context of maritime archaeology, the usefulness of metaphors underscores for us the importance of water as a connecting medium for all of human history, whether those aspects are related to subsistence, occupation, everyday life, religion, or purely aesthetic experiences. For that reason, metaphor is not only important for understanding the relevance of artistic approaches in the context of maritime archaeology and historical research; it also is connected in particular to the topics that were included in the ‘Worldviews’ section of the course. This thematic page included lectures and literature on boat burials, the ship motif in rock art, human–marine mammal relationships in cosmologies, the ship as symbol as well as maritime cultural legends and beliefs. Humans’ relationship with water and the maritime environment differs geographically and chronologically. To better understand the many immaterial motives behind the activities that produced the various archaeological and historical manifestations of maritime cosmologies and related rituals, it is extremely helpful for students to think through metaphor. Metaphorical thinking not only helps us be more creative in researching, for example, maritime mythologies, maritime subsistence, or the risks involved in interacting with the sea, it also provides a fluid framework through which we can better understand how those customs and beliefs have been transmitted to our time, culture, and cognition.

Disclosure statement

The authors report that there are no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Marko Mikael Marila

Marko Mikael Marila is a postdoctoral researcher in Technology and Social Change at Linköping University. His interests include the history and philosophy of archaeology and the intersection of archaeology and contemporary art. Within the sphere of maritime archaeology, Marila’s research has focused on the history of underwater heritage management, academic education, and the theoretical and methodological development of the discipline.

Kristin Ilves

Kristin Ilves is Associate Professor in Maritime Archaeology at the University of Helsinki. Interested in maritime cultural landscapes, she is currently focusing on relating climate, environment, and culture change to each other and is particularly drawn to the construction of island identities. She has extensive fieldwork experience and a fascination with the development of innovative techniques in order to present archaeological sites to public and professional audiences.

References

- Alonso-Población, E. & Niehof, A. 2019. On the Power of a Spatial Metaphor: Is Female to Land as Male is to Sea? Maritime Studies, 18: 249–57.

- Alvesson, M. & Sandberg, J. 2021. Re-imagining the Research Process: Conventional and Alternative Metaphors. London: Sage.

- Bachelard, G. 1983. Water and Dreams: An Essay on the Imagination of Matter. Dallas, TX: The Dallas Institute of Humanities and Culture.

- Bailey, D. W., Navarro, S., & Moreira, Á. eds. 2020. Ineligible: A Disruption of Artefacts and Artistic Practice. Santo Tirso: International Museum of Contemporary Sculpture.

- Chittock, H. & Valdez-Tullett, J. eds. 2016. Archaeology with Art. Oxford: Archaeopress.

- Costlow, J., Haila, Y., & Rosenholm, A. eds. 2017. Water in Social Imagination from Technological Optimism to Contemporary Environmentalism. Leiden: Brill.

- Dening, G. 2002. Performing on the Beaches of the Mind: An Essay. History and Theory, 41(1): 1–24.

- Eliade, M. 1959. The Sacred and The Profane: The Nature of Religion. Orlando, FL: Harcourt.

- Firth, A. 2008. Education in Maritime Archaeology: An Opinion. Journal of Maritime Archaeology, 3: 125–26.

- Gately, I. & Benjamin, J. 2018. Archaeology Hijacked: Addressing the Historical Misappropriations of Maritime and Underwater Archaeology. Journal of Maritime Archaeology, 13: 15–35.

- Gates, L. 2010. Professional Development through Collaborative Inquiry for an Art Education Archipelago. Studies in Art Education, 52(1): 6–17.

- Gheorghiu, D. & Barth, T. eds. 2019. Artistic Practices and Archaeological Research. Oxford: Archaeopress.

- Gould, R. A. ed. 1983. Shipwreck Anthropology. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico.

- Hillman, B. 2009. Practical Water. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press.

- Ilves, K., Leppäsalko, M., & Marila, M. 2022. Representations of Maritime Archaeology in Two National Newspapers of Finland: A Comparative Perspective between Helsingin Sanomat and Hufvudstadsbladet. In: P. Halinen, V. Heyd, and K. Mannermaa, eds. Odes to Mika. Festschrift for Professor Mika Lavento on the Occasion of His 60th Birthday. Monographs of the Archaeological Society of Finland 10. Helsinki: The Archaeological Society of Finland, pp. 241–47.

- Ilves, K. & Marila, M. 2021. Finnish Maritime Archaeology through Its Publications. Internet Archaeology, 56.

- Killian, J. & Rich, S. A. 2023. Maritime Christening: Anthropomorphism and the Engender(bend)ing of Metaphor. In: S. A. Rich and P. B. Campbell, eds. Contemporary Philosophy for Maritime Archaeology. Flat Ontologies, Oceanic Thought, and the Anthropocene. Leiden: Sidestone Press, pp. 105–22.

- Lakoff, G. & Johnson, M. 1980. Metaphors We Live By. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Lawrenz, F. & Huffman, D. 2002. The Archipelago Approach to Mixed Method Evaluation. American Journal of Evaluation, 23(3): 331–38.

- Lee, A. & Green, B. 2009. Supervision as Metaphor. Studies in Higher Education, 34(6): 615–30.

- Lehtimäki, M., Meretoja, H., & Rosenholm, A. eds. 2018. Veteen kirjoitettu. Veden merkitykset kirjallisuudessa. Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura.

- Lynch, H. L. & Fisher-Ari, T. R. 2017. Metaphor as Pedagogy in Teacher Education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 66: 195–203.

- Marila, M. & Ilves, K. 2020. Long-term Degree Program Success in Maritime Archaeology. Helsinki: University of Helsinki.

- Marila, M. & Ilves, K. 2021. Maritime Archaeology in Finland: History and Future Tasks. Journal of Maritime Archaeology, 16(3): 333–51.

- Marila, M. & Ilves, K., forthcoming. Maritime Archaeology at the University of Helsinki. In: L. Kunnas, M. Marila, V. Heyd, E. Holmqvist, K. Ilves, A. Lahelma, and M. Lavento, eds. Celebrating 100 Years of Archaeology at the University of Helsinki: Past, Present and Future. Iskos 27. Helsinki: Finnish Antiquarian Society.

- Martínez, M. A., Sauleda, N., & Huber, G. L. 2001. Metaphors as Blueprints of Thinking About Teaching and Learning. Teaching and Teacher Education, 17: 965–77.

- McGrail, S. 1995. Training Maritime Archaeologists. In: O. Olsen, J. S. Masden, and F. Rieck, eds. Shipshape. Essays for Ole Crumlin-Pedersen. Roskilde: Viking Ship Museum, pp. 329–34.

- McGrail, S. 1997. Studies in Maritime Archaeology. Oxford: British Archaeological Reports.

- Muckelroy, K. 1978. Maritime Archaeology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Okonski, L. & Gibbs, R. W. Jr. 2019. Diving into the Wreck: Can People Resist Allegorical Meaning? Journal of Pragmatics, 141: 28–43.

- Pearson, M. & Shanks, M. 2001. Theatre/Archaeology. London: Routledge.

- Pétursdóttir, Þ. & Olsen, B. 2018. Theory Adrift: The Matter of Archaeological Theorizing. Journal of Social Archaeology, 18(1): 97–117.

- Ransley, J. 2008. Time for a Little Pedagogical Reflection? Journal of Maritime Archaeology, 3: 53–58.

- Renfrew, C. 2003. Figuring It Out: What Are We? Where Do We Come From? The Parallel Visions of Artists and Archaeologists. London: Thames and Hudson.

- Renfrew, C., Gosden, C., & DeMarrais, E. eds. 2004. Substance, Memory, Display: Archaeology and Art. Cambridge: McDonald Institute.

- Rose, E. 2016. Reflection in Asynchronous Online Postsecondary Courses: A Reflective Review of the Literature. Reflective Practice, 17(6): 779–91.

- Russell, I. A. & Cochrane, A. eds. 2014. Art and Archaeology: Collaborations, Conversations, Criticisms. New York: Springer-Kluwer.

- Steinberg, P. E. 2013. Of Other Seas: Metaphors and Materialities in Maritime Regions. Atlantic Studies, 10(2): 156–69.

- Stratford, E., Baldacchino, G., McMahon, E., Farbotko. C., & Harwood, A. 2011. Envisioning the Archipelago. Island Studies Journal, 6(2): 113–30.

- Tilley, C. 1999. Metaphor and Material Culture. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Tilley, C., Hamilton, S., & Bender, B. 2000. Art and the Re-presentation of the Past. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 6: 35–62.

- Ward, C. 2003. Integrating Maritime Archaeology. American Journal of Archaeology, 107(4): 655–58.

- Westerdahl, C. 1992. The Maritime Cultural Landscape. International Journal of Nautical Archaeology, 21: 5–14.