Abstract

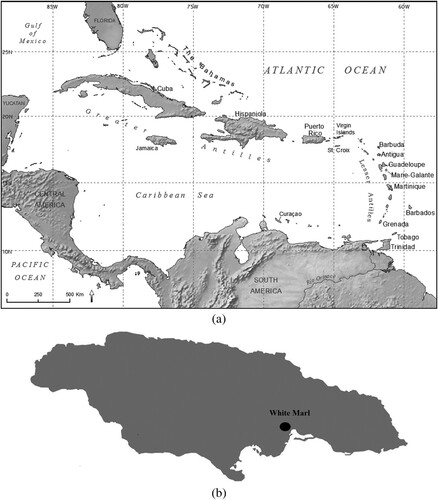

White Marl is the largest, most complexly organized pre-colonial site documented for Jamaica and it is increasingly at risk due to plans for highway improvements. The site is of fundamental importance to overlapping sets of stakeholders: local residents, descendant communities, professional and avocational archaeologists, and heritage managers. We consider concepts of memory and heritage, linking decades of archaeological research at White Marl to current conceptions of the place by descendants of the first Taíno settlers and by residents of Central Village, the modern community surrounding the site. We review White Marl’s archaeological history and situate the site in its current social, cultural, political, and economic context of Central Village. White Marl has been the focus of varied archaeological interpretations since the nineteenth century. In addition to the archaeological community, this heritage resource is important to local community members and descendants of the original Indigenous occupants. The Taíno Museum adjacent to the site, established by the Institute of Jamaica in 1965, now serves as a church and school for local residents. Continuities are explored between the Indigenous pre-colonial occupants of White Marl, current occupants of Central Village, and the Indigenous descendant community.

White Marl is the largest most structurally complex Indigenous site documented for Jamaica. The site represents a place of transcendental significance for overlapping sets of stakeholders on the island, much like Stonehenge does for people in the UK and beyond (Lucas, Citation2005; Bailey, Citation2007) and in the Caribbean the large iconic civic-ceremonial centre of Caguana does for the people of Puerto Rico (Oliver, Citation2005). The integrity and future of White Marl are under potential threats from planned development initiatives sponsored by the Government of Jamaica and from local corporate expansion interests. Our goals in this paper are twofold: (1) highlight the heritage, symbolic, and perhaps emotional significance of White Marl for Jamaicans who have a stake in its preservation and management and (2) build on the heritage significance of White Marl in promoting a more inclusive and long overdue reframing of heritage consideration and management policies by the Government of Jamaica.

White Marl may be viewed as a microcosm of the public archaeology issues and challenges that heritage managers have faced for decades in Jamaica and indeed across many of the island nations of the West Indies (Richards & Henriques, Citation2011; Siegel, et al., Citation2013). As Richards & Henriques (Citation2011: 31) emphasized,

present legislation (JNHT Act 1985) does not address the need for mandated archaeological impact assessments … Legislation is useless if laws are not implemented … Unfortunately, the JNHT [Jamaica National Heritage Trust] undertakes much of the work that it seeks to monitor and regulate.

In this paper we will highlight shifting Indigenous, European, and African occupations, interpretations, public perceptions and values, and national heritage management policies applied to the White Marl site. Focusing on shifting values and management policies relates to ideas about the archaeology of place in that people imbued specific places with particular significance (Tilley, Citation1994; Bailey, Citation2007). Specific places holding great value to a group of people are called Traditional Cultural Properties in the U.S. system of heritage management (Parker & King, Citation1990; Parker, Citation1993).

‘Traditional’ in this context refers to those beliefs, customs, and practices of a living community of people that have been passed down through the generations, usually orally or through practice. The traditional cultural significance of a historic property, then, is significance derived from the role the property plays in a community's historically rooted beliefs, customs, and practices. (Parker & King, Citation1990: 1)

Following an overview of the archaeological history of White Marl, we will address the importance of the place for (1) the pre-colonial Indigenous People who occupied the settlement, (2) the residents of Central Village, which is the modern town currently surrounding the site, (3) the Indigenous descendant communities of the first settlers, and (4) the cultural heritage communities who recognize the site’s importance.

As the island’s largest pre-colonial site, White Marl contains significant and unique sources of information regarding Jamaica’s past (Howard, Citation1965; St. Clair, Citation1970; Silverberg, et al., Citation1972; Allsworth-Jones, Citation2008; Atkinson, Citation2006; Citation2019). It was occupied by Caribbean Indigenous People from c. AD 900 through the early years of European contact, followed by Spanish and English colonizers (Howard, Citation1950; Citation1956; Citation1965; St. Clair, Citation1970; Silverberg, et al., Citation1972; Allsworth-Jones, Citation2008; Mickleburgh, et al., Citation2018; Atkinson, Citation2019; Elliott, et al., Citation2022). White Marl’s existence has been recognized for hundreds of years and the nature of the site became more apparent when a road was put through it in the eighteenth century (Sheffield, Citation1755). Antiquarians, natural historians, and archaeologists have addressed White Marl since the mid-nineteenth century (). Owing to the lack of continuity in these investigations, especially in the absence of a site base map where excavation units can be integrated from the various field projects, Allsworth-Jones (Citation2008: 15) evocatively referred to White Marl as ‘a headless colossus of Jamaican prehistory’.

History of investigations at White Marl

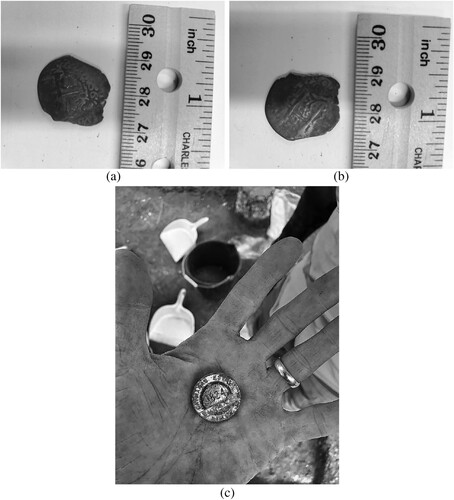

White Marl is a deep, well-stratified site continuously occupied for approximately 800 years (). The larger setting of White Marl was also the location of three British sugar plantations or estates operating during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, referred to as the Caymanas Estates (Higman, Citation1988: 151–58, 226). However, other than isolated surface finds of historic-period artefacts () and some brick architectural features likely related to Caymanas Estate there is no evidence for colonial-era deposits.

Figure 2 Stratigraphic layering documented in Excavation Unit T2-11. Photograph by Zachary J. M. Beier.

Figure 3 Spanish silver real recovered from Excavation Unit G3, Level 1: (a) Obverse. Based on minting execution and last two visible digits the coin dates to 1656 (Pradeau, Citation1938: 43–45, pls II, III); (b) Reverse; (c) 1824 button worn by labourers of the British Caymanas Estate located on or near White Marl. Photographs of the coin by Peter E. Siegel and the button by Zachary J. M. Beier.

Images courtesy of the Jamaica National Heritage Trust

In reviewing the site’s archaeological history, it is important to consider meanings ascribed to the place by the past and present residents of White Marl and Central Village, respectively; the Indigenous descendant community; and the archaeologists who have studied the site. We recognize changing perceptions of Native identity and overlapping perspectives of White Marl during the eras of Indigenous occupations; European colonialism; “anthropologies” of the native other; the beginnings of formal archaeology and public education; increasing development of highway, community, and corporate complexes; and efforts to rescue and interpret the site through multi-stakeholder collaborations and interdisciplinary studies.

The first description of the White Marl site was made by Richard Hill (1795–1872) in the mid-nineteenth century. Hill was a lawyer, naturalist, and friend of Charles Darwin, and he referred to the site as ‘the Indian Village at the Marl Hill, on the Kingston Road’ (Hill, Citation1860: 49; see also Cundall, Citation1920). Hill noted the presence of structures, hearth features, human remains, pottery, and abundant faunal remains including hutias and terrestrial and marine molluscs (Hill, Citation1860; see also Gosse & Hill, Citation1851; Hill, Citation1859). Based on his observations of archaeological materials visible in the bisection of the site by the early road, Hill concluded ‘that [the] Village had been destroyed by violence, and that these are the bones of some of the people who died in the conflict’ (Hill, Citation1860: 50). In his survey of Aboriginal Indian Remains in Jamaica, James Edwin Duerden (1869–1937) placed Hill’s discussion of White Marl into a larger cultural and natural history context (Duerden, Citation1897: chapter II).

The first systematic archaeological study of the site was conducted by Robert Randolph Howard, initially with a few test units as part of his dissertation research in the late 1940s under the supervision of Irving Rouse and later more intensive excavations in the 1960s funded by the National Science Foundation, the Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research, and the University of Wisconsin Graduate School (Howard, Citation1950: 85–87; Citation1956; Citation1965). The White Marl pottery style was defined by Howard (Citation1965) based on his extensive excavations in the site. Rouse subsequently included White Marl initially as an archaeological complex with the Meillacoid series (Rouse & Allaire, Citation1978: 473, fig. 13.8; Rouse, Citation1982: fig. 1) and later with the Meillacan Ostionoid subseries (Rouse, Citation1986: fig. 23; Citation1992: fig. 14). By defining the Meillacan Ostionoid subseries, Rouse recognized sufficient similarities between assemblages in Jamaica and portions of Cuba and Hispaniola between at least c. AD 900 and 1200.

Based on his analysis of White Marl and other Jamaican assemblages, Howard concluded that archaeologically the island represented a form of prehistoric ‘cultural retardation’ in comparison to the other islands of the Greater Antilles and it was seemingly in an ‘out of the way’ location (Howard, Citation1950: 167). Howard’s view of presumed geographic isolation as an explanation for Jamaica’s presumed cultural backwardness stemmed from Alfred Kroeber’s general consideration of ‘marginal retardation’ as a cultural phenomenon, whereby geographically peripheral cultures will be lacking in many of the attributes of those in the ‘higher centres’ (Kroeber, Citation1948: 418–21). Howard further observed that ‘Jamaican ceramics appear somewhat crude, unimaginative, and provincial’ compared to pottery from Puerto Rico and Hispaniola (Howard, Citation1956: 55).

In rejecting Jamaica’s inclusion within Julian Steward’s (Citation1948) characterization of the circum-Caribbean culture area generally and complex chiefly societies in particular, Howard (Citation1950: 187) stated that the island ‘reveals most clearly the absence of ceremonial elaboration … [and that the island] simply never reached the high level of social, political, religious, or technological development’ other islands of the Greater Antilles had achieved. We see in these observations the influence of his mentor, Irving Rouse, who had at that stage of his thinking referred to Sub-Taínos vs. Taínos (Rouse, Citation1948: 516, 521, table 2)/Classic Taínos (Rouse, Citation1986: 114–16). M. R. Harrington (Citation1921: 395) originally coined the term ‘sub-Taino’: ‘there may have been settlements of Jamaican Indians in Cuba before the coming of the true Taino, or at least settlements of Indians with similar sub-Tainan culture’. Sven Lovén too referred to ‘sub-Tainan culture’ as ‘the earlier Tainan culture’ (Lovén, Citation1935: vi). We see in these varying usages of ‘sub-Taíno’ vs. ‘Taíno’ or ‘Classic Taíno’ geographic, chronological, and cultural developmental implications. For Lovén, ‘proper Tainan culture’ equated to ‘the higher Tainan civilization developed on Puerto Rico and Española’ (Lovén, Citation1935: vi). Howard (Citation1956: 47) acknowledged that the paucity of many especially complex organized sites in Jamaica ‘is probably more apparent than real’ owing to the difficulty of finding sites and the lack of systematic surveys.

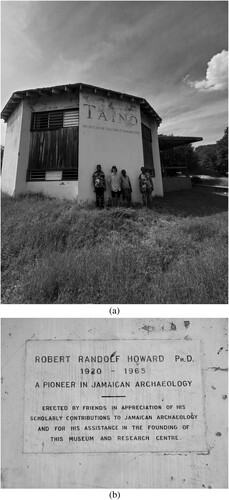

Recognizing the importance of Howard’s archaeological research and the need to preserve White Marl, the Institute of Jamaica (IOJ) established a museum, laboratory, and residence in the area (). Howard died shortly after the museum’s installation at the age of forty-five in 1965 (Rouse, Citation1967) and one of his graduate students, Ronald Vanderwal, continued excavations in the site, which formed the primary basis for his ‘seriation of south coast sites’ (Vanderwal, Citation1968: 87). Following Howard’s work, in the summer of 1969, with support from the IOJ, James St. Clair directed the excavation of a 120-square foot block in the site and reportedly identified a ‘circular structure’ 14 feet in diameter represented by nine post moulds (St. Clair, Citation1970: 8). In addition, St. Clair reported twelve burials in a cave located about 500 yards north–north-west of the Taíno Museum. After Howard’s death, a final report to NSF needed to be prepared. James Silverberg, who was Chair of Anthropology at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, Ron Vanderwal, and Elizabeth Wing teamed up to produce the report. In summarizing the major findings, they observed that ‘White Marl is the best radiocarbon dated site in the West Indies’ at the time of their report (Silverberg, et al., Citation1972: 41).

Figure 4 (a) Taíno Museum with Zach Beier and Central Village collaborators; (b) Plaque dedicated to Robert R. Howard mounted on the exterior of a museum wall. Photographs by Peter E. Siegel.

On completion of St. Clair’s investigations, archaeological field work at White Marl ceased for the next forty-seven years. This lack of attention did not reflect a lack of interest on the part of archaeologists and wider Jamaican society but the increasingly dire social, political, and economic conditions in the modern community of Central Village that surrounds the White Marl site:

Political activists, gunmen take over Indian Village … THE WEEK-END STAR could only go as far as the gate of the site. It was not advisable to go any further. One source said that the Village is occupied by political activists who use the area as a hideout. ‘Sometimes gun-shots can be heard coming from the Village. The bad men are in total control,’ a bystander said. (The Weekend Star, March 9, Citation1990: 7)

Gang warfare continued to impact research and public education at White Marl for many years:

The museum was a casualty of the gang violence and extortion which were rampant in the Central Village and Windsor Heights areas as ongoing feuds left a number of residents dead and kept away potential visitors. Busloads of schoolchildren, who once looked forward to annual trips to the facility to soak up the history of the Tainos, have long since ceased, putting the students at a disadvantage. (Hussey-Whyte, Citation2012)

… it is crucial that researchers recognize that each ethical dilemma encountered during fieldwork is unique and rooted in social contexts, interpersonal relationships, and personal narratives … concerns about ethical research become even more important when considering multiple differences between North and South in relation to culture, power, inequalities, politics, and geographies. (D’souza, et al., Citation2018: 29)

In conducting field work at White Marl, Beier found that it is crucial to foster good and sincere relations initially with selected community members and eventually many people in Central Village through their social networks. After all, White Marl is a heritage resource embedded in their community. Financially compensating a small core group of individuals ensures sustainable and reliable relations within the community. One anonymous project commentator opined that the ethics of paying local residents for assistance in field work and community relations ‘is a HUGELY problematic approach to community-based archaeology’. We would argue that not compensating community members for their help, especially in the context of the pervasive grinding poverty and structural violence that characterizes much of Jamaica, will perpetuate the violent, extractive, exploitative, and colonialist enterprise represented by the seventeenth- and eighteenth-century British plantations that thrived on the backs of unpaid slave labour: ‘ … the present in which we live has been built on a past for which imperialism and racial slavery were foundational’ (Thomas, Citation2011: 5) … ‘extractive labor regimes … excluded non-Europeans from the category human … [were] subsequently mobilized to serve late nineteenth-century projects of imperial rule … as well as the emergent imperialist project of the United States’ (Thomas, Citation2019: 3). In efforts to disrupt the imperialist, exploitative, and neo-colonialist continuum, it is incumbent on researchers to compensate local collaborators for their time, assistance, and knowledge. In other words, treat community collaborators with respect and don't patronize them.

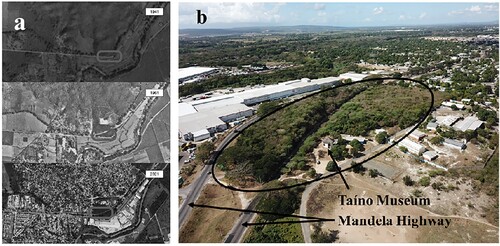

Considerable changes have occurred in Jamaican society and Caribbean archaeology over the forty-seven-year hiatus in formal investigations at White Marl. Aerial photographs of the area between the 1940s and today reveal the expansion of development for transportation, commercial, and residential purposes, resulting in accelerated destruction of the site margins ().

Figure 5 (a) Three aerial photographs of the Central Village area showing the increasingly developed landscape and impacts to the White Marl site. White Marl is situated within the oblong box in each of the images. Compiled by Zachary J. M. Beier and figure created by Edward González-Tennant; (b) Drone/aerial photograph facing southwest over the White Marl site, former Taíno Museum, White Marl Primary School, and Lasco corporate complex. The oblong encircles the White Marl site. Drone photo by Zachary J. M. Beier (6 March 2022).

In 2016, 2018, and 2019 rescue archaeological field work and assessments were conducted in advance of planned expansion of the Mandela Highway that bisects the site (Ramdial, Citation2017). This work was sponsored jointly by the Jamaica National Heritage Trust (JNHT) and the University of the West Indies, Mona Campus (UWI, Mona). Leiden University assisted in the 2016 and 2018 field seasons. A substantial amount of midden material and twelve additional human burials were recovered during this recent work. Combined with work from the mid-twentieth century, twenty-eight human burials are now documented for the site and many more are no doubt still in the ground. This work has revealed a diverse diet based on a range of terrestrial resources collected or cultivated by the inhabitants of White Marl, including the first direct evidence of cacao (Theobroma cacao) consumption in the Indigenous West Indies (Mickleburgh, et al., Citation2018). There is also increasing evidence for the management and possible domestication of Jamaican hutias (Geocapromys brownie), small terrestrial rodents (Shev, et al., Citation2022). Analysis of charcoal particulates collected from sediment samples indicates active landscape management through controlled burns by the village residents (Elliott, et al., Citation2022).

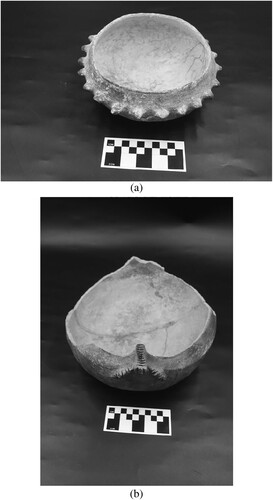

The cumulative field investigations carried out in White Marl clearly indicate that this ‘headless colossus of Jamaican prehistory’ was an important centre or hub of social, political, religious, and economic activities with regional and potentially interregional connections (). Contrary to Howard’s mid-twentieth-century rather dismal view of Jamaican pre-colonial ‘cultural retardation’ and imputing its residents as ‘unimaginative and provincial’, we would suggest that from c. AD 900 to 1600 the people of the island were intimately integrated in a complex socio-political, ideological, and cosmological system across the island, the Greater Antilles, and perhaps the northern Lesser Antilles (, , ). This view is consistent with current thinking regarding a connected Caribbean (Curet & Hauser, Citation2011; Hofman & van Duijvenbode, Citation2011; Keegan, et al., Citation2013; Mol, Citation2014). Distinctive pottery styles and imagery in other classes of artefacts identified across the region may represent unique expressions of identity maintained by interconnected cosmopolitan polities of the late pre-colonial West Indian world (Sinelli, Citation2013: 225). The four wooden artefacts depicted in were included in a pan-Caribbean study of such artefacts carried out under the direction of Joanna Ostapkowicz (Ostapkowicz, et al., Citation2012; Citation2013; Citation2017; Ostapkowicz, Citation2015). Her AMS dating of them indicates a range of c. cal AD 1260–1520 for the group, consistent with the later Indigenous occupations of White Marl (Ostapkowicz, et al., Citation2012; Ostapkowicz, Citation2015; Mickleburgh, et al., Citation2018; Shev, et al., Citation2022).

Figure 6 Two ceramic vessels recovered from White Marl: (a) Distinctive star-shaped vessel associated with a burial from Excavation Unit J2, Level 10; (b) Navicular vessel recovered from Excavation Unit K2, Level 10. Contrary to Howard’s (Citation1950) dismal view of Jamaican pre-colonial ‘cultural retardation’ and its residents ‘unimaginative and provincial’ pottery tradition, these vessels evince a rich iconographic and symbolic system encoded in clay pots. Photographs by Peter E. Siegel.

Images courtesy of the Jamaica National Heritage Trust

Figure 7 Four cosmologically charged wooden artefacts from Jamaica: (a) Cemí spoon, 14 cm high, lignum vitae (Guaiacum sp.), Aboukir cave (St Ann Parish); (b) Pelican cohoba statue, 63 cm high, lignum vitae (Guaiacum sp.), Aboukir cave (St Ann Parish); (c) Cemí staff, 150 cm high, Protium or Bursera wood, Aboukir cave (St Ann Parish); (d) detail of the cemí staff; (e) Duho (ceremonial seat), lignum vitae (Guaiacum sp.), cave (St Catherine Parish).

Images courtesy of the National Gallery of Jamaica

Figure 8 Two ceramic effigy vessels from the Dominican Republic in the form of shamans depicted during hallucinogenic trances (Roe, 1997: pls 104, 108). Left: 27.5 cm high, right: 17 cm high. Photographs by Dirk Bakker.

Interconnections between Jamaica and other islands of the Greater Antilles were anticipated decades ago by Froelich Rainey (Citation1940), albeit not in explicitly social or political terms. In summarizing Jamaican collections known at the time, he noted similarities (interconnectedness) and differences (unique expressions of identity) between what we now call White Marl assemblages in Jamaica and what Rainey called Shell Culture (post-Saladoid) assemblages in Puerto Rico:

The crude pottery, boat-shaped vessels, modeled head lugs, modeled figures on vessel walls, line and puncture incised design (rare), petaloid stone celts, shell celts, and small, carved, stone figures in the bound position, conform to the Shell Culture complex as established in Porto Rico. The absence of Red Slipped Ware, modeled head lugs representing the bat, the limited number of modeled lugs, the rarity of the line and puncture incised design, and the general crudeness of the pottery indicate a noticeable variation of the Shell Culture complex, and suggest a certain cultural segregation in Jamaica. The perforated knobs … as described by de Booy, were not found in Porto Rico, and as far as the writer knows, are also absent in collections from the other islands of the Greater Antilles. (Rainey, Citation1940: 148)

White Marl’s archaeological history is important to understand when considering the current management and cultural heritage challenges facing stakeholders who have an interest in preserving this significant heritage resource, not only for modern Jamaicans but for the wider Caribbean community (). The connected pre-colonial Caribbean has implications for a connected Caribbean of heritage managers (Siegel, et al., Citation2013). We will now address the importance of White Marl as it relates to (1) the current residents of Central Village, (2) the Jamaican Hummingbird Taíno People who are the Indigenous descendants of the first settlers in Jamaica, and (3) the Jamaica National Heritage Trust, the heritage regulatory agency overseeing development activities that could impact the site. Integrating local community members and others in the White Marl project reflects a growing awareness by archaeologists of the importance to seriously engage these stakeholders in heritage consideration, management, and consultation (Zimmerman & Dawn Makes Strong Move, Citation2008; Hofman & Hoogland, Citation2016; González-Tennant, Citation2018; Franklin, et al., Citation2020; Flewellen, et al., Citation2021).

Table 1. STAKEHOLDERS WITH AN INTEREST IN THE WHITE MARL SITE.

Central Village and White Marl

The Taíno Museum and archaeological laboratory located along the edge of the White Marl site and which was dedicated to Robert Howard in 1965 was closed in 2007 and may never reopen. With the increasing levels of violence in the town, local and foreign tourists stopped coming to the museum. There was some discussion by the IOJ to relocate the museum to a cave in Hellshire but that has not come to pass (Hussey-Whyte, Citation2012). The museum complex has since been taken over by a Central Village church, the Christian Rescue Mission. In talking with some of the Central Village community members and church congregants, the place of White Marl is permeated with meaning and memory-making. They also recognize some connection to the original Indigenous settlers of the place.

We interviewed Miss Naomi Johnson (NJ, ), one of the church congregants/Central Village community members (6 March 2022):

You have told me that you consider this place to be sacred, centred on the Christian Rescue Mission [former Taíno Museum]. You have also told me that this place was important to the Taínos before the Europeans and Africans arrived.

We describe them as the pioneers, the Taíno Indians. When Christopher Columbus came here [1494] they were here already. We don’t know if they were originally from here. How can we know? They leave a kind of legacy that people are interested in; archaeology and history. They say our ancestors came from Africa. Well, fine, what about the people who came here before us? I’m sure that when the Africans came here they found cassava, one of the Taínos’ foods.

Which is now a big crop in Africa.

Exactly. And corn or maize too. The Taínos were farmers.

So, when you talk about this church, the Christian Rescue Mission, you told me previously that this place is a sacred space.

Yes, it is.

And I believe the Taínos also certainly thought of White Marl village, or portions of it, as a sacred space, where they buried their dead, etc.

This was the centre for them [the Taínos], where the chief lives. I believe that this is really a sacred historical place. And for the church to be here, where we believe in the Lord Jesus Christ, makes it double, doubly sacred!

So, before the Europeans and Africans were here and it was the Taínos; those people had their religious beliefs.

Yes, down through the ages you have people who worshipped God, who were actually searching because they know there’s a sovereign being. In their mind they are searching for the true God. I love Nature. And when you look at Nature there is no way you can say that there is not a Supreme Being who holds that [Nature] in place. And I believe that the Indians realized that in their time because they were farmers. Last time I spoke to you, I had a visitation; I don’t know if it was a dream or what. I met up with this Indian, a Taíno Indian. I don’t know if he was a chief. We were talking about the garbage [artefacts] around here. So, this place is really sacred and for there to be a church here first brings out what they [the Taínos] were trying to find. Because in their time they were trying to find God. In their way of worship God is in everything. Things are preserved up there in the bush [White Marl site] then you know God allowed those things to be there down through the ages; it’s a long time. These things didn’t sink underground and dissolve out. We can find them. And it shows us that people were here before us.

We see in these comments by Miss Johnson multiple meanings that have formed around the place of White Marl. Although she clearly sees a distinction between her strong faith in Christianity and that of the Taíno belief system (cemíism), the community member recognizes the importance and legitimacy of the pre-colonial Indigenous presence. In some ways, the intersection of Christianity and cemíism engenders or imbues this particular physical space of the White Marl site/museum/church with greater significance than if they were spatially segregated or, as Miss Johnson stated, the place is ‘doubly sacred!’.

Figure 9 Miss Naomi Johnson is a resident of Central Village and member of the Christian Rescue Mission (6 March 2022). Photograph by Peter E. Siegel.

Multiple perspectives or vantages of significance have been ascribed to other heritage resources. This is seen most prominently with Stonehenge: ‘Stonehenge is not just a prehistoric monument – it is also a Roman one, a Medieval one and a contemporary one, no matter whether it has been physically intervened with or not’ (Lucas, Citation2005: 35). As such, Stonehenge holds ‘different significance for different people in successive periods, and perhaps a different significance for different people within the same society, including, in modern society, archaeologists, heritage managers, Druids, New Age enthusiasts and foreign tourists’ (Bailey, Citation2007: 208). The Stonehenge example underscores the importance for archaeologists and heritage managers to consider how humans in both the past and present engaged with heritage places and landscapes (Lucas, Citation2005: 87–88). Just as with Stonehenge, in the case of White Marl we recognize the importance of integrating local and community perspectives into the research and preservation of such places.

We will now address the significance of White Marl for the descendant community.

Taíno identity and White Marl

According to the most recent government census, Jamaica includes persons of African descent, Whites, Asian Indians, and Chinese. Indigenous people are not represented. Recently, the Government of Jamaica is making an effort to more formally recognize the existence and contributions of these first peoples of Jamaica:

Members of the society who identify themselves as Taino through the Yamaye Guani Council (the Council) were engaged, primarily through the Jamaica National Heritage Trust, who, through historical and archaeological research continues to unearth and to preserve, protect and promote our heritage. They have established and promoted Taino Day throughout Jamaica and engage the Council and its membership. (Grange, Citation2022: 16)

recommends that the State party [Government of Jamaica] collect and provide to the Committee updated and comprehensive statistics on the demographic composition of the population, based on the principle of self-identification, disaggregated by ethnic or national origin, including on Maroons, Tainos, Rastafaris … It also notes that the State party considers that there are no Indigenous Peoples in Jamaica, while it recognizes Maroon and Taino as cultures that are indigenous to Jamaica. The Committee is concerned that this approach could marginalize communities within the State party that self-identify as indigenous peoples and could maintain or intensify situations of direct, indirect, multiple and intersecting forms of discrimination faced by them. (Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, Citation2022: 2–4; emphasis added)

What is the importance of White Marl to the Yamaye Guani? You know, we have many sites. What I think makes White Marl special to us is that we can’t connect very well with many of the other sites due to lack of access from development. In the case of White Marl, there’s this feeling of saving history that has been taking place because of work scheduled for some years now to widen the highway running through the site. There has been this rescue archaeology that’s been taking place. There’s been a call to awareness of the importance of the site.

Unfortunately, students can no longer visit the Arawak Museum that was there previously. The site holds this energy, this emblem of a transition and it brings to question, where are our values as a society, as a people? What are we willing to compromise; what lessons do we want to leave for future generations?

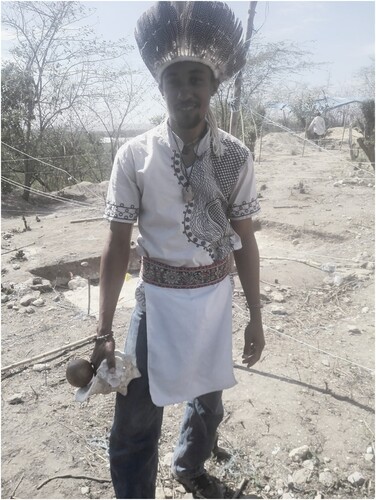

One of the first official interactions that I had with White Marl before becoming chief, when I was a medicine person (behique), was to conduct a ritual here for the ancestors (). This was when a group of infant remains was recovered, and we went there to honour the space. This was the first time we honoured the space in the presence of people from academia, people from the JNHT (Jamaica National Heritage Trust), UWI (University of the West Indies), students, and through this interaction it was realized and understood that this is a sacred space; these (burials) are people that are being found, these are family members, these are stories and it was an opportunity to give life to those stories. Since that first interaction with this space that life force has grown to where today there is a church (Christian Rescue Mission). And those church members want to recognize the Arawakan people and want to know how to honour this space and work with us as a community. To really bring respect to this space.

Figure 10 Prior to his investiture as chief, Kalaan was a behique (medicine person). Behique Kalaan is seen here performing a ceremony held during 2019 fieldwork at White Marl.

There have been several stories that have come forth of them (church members) trying to hold certain services and they couldn’t hold it in the space of the Arawak Museum for whatever reason. They were getting interactions, learning the names of chiefs, having dreams, having visions, having messages, and a lot of the things they were speaking to us I could confirm that these are parts of our tradition. That yuca or cassava (Manihot esculenta) is special to us. Tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum), or cohiba, is special to us. There is an energy, a presence, an awareness, an identity to this space itself. And those who inhabit these spaces, that have a true desire to really connect in a respectful way are able to tap into the understanding of that space. And pass on the messages that are relevant for this time that we are in.

For us there are cycles and death is really the end of one cycle and the beginning of another. It is symbolic of a new moon shifting to a full moon. Symbolic of a summer solstice moving to a winter solstice. From a point of a high peak and rays of heat to a point of descending and decline and how we perceive it is that there was a time of this shift towards that new moon, this darkness as it relates to our culture and our ways of being. And we’re moving towards this full moon now, where there’s more awareness, more growth, more acceptance. And it seems to be centralized around this space [of White Marl], at the epicentre.

One of the last discussions I had about this site was with some of the heads of IOJ and JNHT. And the discussion was to put White Marl back on the table as one of the central Taíno villages and see what work can be done to bring a celebration there and more awareness to the general population. We’re trying to work with the community there to understand the value of the space that they’re in. And how to live in harmony and balance with it. Hopefully, to preserve some areas of that space for continuity of these traditions, for continuities of these ways.

We see the iguana (Cyclura collei) as a totem. The iguana for us is connected to the sun. An animal that spends its time out during the day; it is diurnal. The spikes on its back represent the rays of the sun. The iguana is very close to our heart in Jamaica because it has been one of the most successful in the world. Reintroduction programmes for an animal that was once thought extinct. And like the iguana, we the Indigenous people of Jamaica were also thought extinct. And the story of the iguana has become such a massive success story of the world. It has brought more attention to what is being done in reintroduction.

For us, White Marl was a symbol of transformation. There was an ending of an era and the road opening represented another era, which we are into now to re-establish a new connection. A connection in this space. I can share that all of our community members receive what we call a yamaye-iri, which means ‘name of the land’. This has a connection to White Marl; it has to have a connection to that place. It is the thread that connects us. We either have to be there [at White Marl] physically or we have some organic item like a tree bark or an old shell; something from that space [of White Marl] would call to them, our ancestors, and that would start the process in receiving their name, crafting their item that is worn, which represents our spirit that is connected to our name. So, this place [White Marl] is really anchored in our resurgence and our hope is that as there’s this growth in our community and awareness of Indigenous Caribbean people, our rights, and our place here as the world moves towards a better understanding of how to live in harmony, how to live in balance with all their sustainable development goals.

We believe that the White Marl site can be a strong lesson. People in the diaspora were amazed at how our community was working with archaeologists and academics because there’s always been this concept of us against them and them against us unless there were Indigenous people as part of the academic team or the archaeological team. Explain to them just as it was back in ancient times where the story for Jamaicans was unique, it is unique now because the work that is being done is work to rescue and to preserve what is in that place. We are aligned on that point and that view and it has created this opening for my investiture ceremony, not a request of myself.

The curator of the Jamaica National Gallery got permission from the higher-ups to bring the cacique [chiefly] ceremonial duho [e.g., e] to the investiture ceremony, validating the ceremony. We’re able to have this type of relationship, which to me is symbolic of that death and rebirth, which is very common in our ancestral stories, in Lokono stories, Warao stories, Taíno stories.Footnote1 Of representing the end of one form and rebirth into another form. So, I believe in this age of communication; technology is also an age of collaboration and I say the White Marl site being a site of coming together of different worlds for common cause to benefit the future.

My people link to the entire island although we clearly recognize the modern practicalities of the ruling nation state, hierarchies of power, and development pressures resulting in the erasure of cultural heritage and Indigenous sites. White Marl represents at once a crucial place of renewed identity for the current Taínos of Jamaica and in the diasporaFootnote2 and a symbolically charged physical space to forge peaceful relations with non-Indigenous communities on the island and potentially abroad. In terms of renewed identity, we symbolically link the Taíno Renaissance to the reintroduction of the iguana, also once thought to be extinct on the island.Footnote3 Finally, Jamaicans identifying as Taínos join Maroon communities in advocating for the significance of their cultural traditions and political sovereignty (Agorsah, Citation1994).

We will now present the perspective of the Jamaica National Heritage Trust on the White Marl site as a significant heritage resource for the country as well as the wider Caribbean.

The Jamaica National Heritage Trust and White Marl

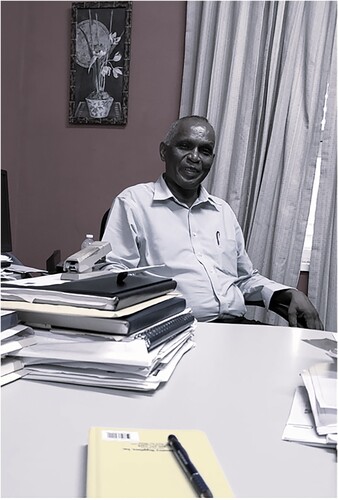

The JNHT is the regulatory agency that oversees the consideration, protection, and management of heritage resources in Jamaica and as such is an important stakeholder in the future of White Marl. To gain the perspective of this agency, we interviewed Mr Selvenious Walters (SW), the JNHT Technical Director for Archaeology (27 September 2023).

Mr Walters, thank you for taking the time to meet with me (). We were hoping to gain your perspective as the Technical Director of Archaeology at the Jamaica National Heritage Trust regarding your views of the White Marl site and its importance for Jamaican heritage specifically and for Caribbean archaeology more generally.

Before I give my perspective on the site, I just want to give some background. The White Marl Taíno site was declared a Jamaican National Monument in the 1990s. As a child growing up, we learned about the site and were told about its significance as an Amerindian archaeological site. It was not until 2016 when we did some work at the site that I realized its magnitude and real significance. This work stemmed from a proposal to expand the existing highway and to cut through an intact portion of the site. Also, there was a proposal at the time for factory expansion in that area.

The Jamaica Board of Trustees (BOT) requested that a team provide an archaeological assessment, which was carried out by the JNHT archaeological field unit. A surface survey revealed vast quantities of pottery across the site. The BOT asked for additional work in the form of exploratory test units to assess subsurface deposits and their depths. We started with 1 × 1 m square units but soon realized that middens went down about 1.5 to 2 m and 1 m square units would not suffice so we opened areas as 2 m square units. We put in perhaps about seven units in the highway median section of the site, where we encountered about four burials and complete or nearly complete ceramic vessels and cemis (deity icons). Our report describing the findings generated a great amount of interest and Mrs Grange, the Minister of Culture, Gender, Entertainment and Sport, came out for a site visit.

Following this initial round of fieldwork, the BOT then wanted additional information about the site to the north of the highway. Fieldwork in 2018 and 2019 recovered three to four more human burials, dense quantities of artefacts, and deep midden deposits in the form of mounds. We excavated about 14 or so 2 × 2 m units in the northern section. In addition, we identified an area we believe might have been a ballcourt.

That’s very interesting. Somebody else from your staff told me that there was the possibility of a ballcourt.

It could be a ballcourt. The mounded middens were placed surrounding the possible ballcourt.

Like a plaza or a ball field. That’s interesting. The Maisabel site that I excavated in Puerto Rico many years ago also produced what we concluded to be a cleared plaza area and it was surrounded by a series of five what we called mounded middens; so you had a plaza with five distinct mounds surrounding the plaza and in the mounds were the most elaborate artefacts manufactured by these people (Siegel, Citation2010).

On the eastern side of the site, heading towards Kingston, we had several middens, pretty much dome-shaped and some elongated and they extended back all the way to the White Marl Primary School, for about 200 or 300 m. But we focused on the area which is closest to the existing highway; that is the area that was going to be impacted by highway expansion. We observed that to create the possible ballcourt, the people had levelled the area by scraping away deposits to marl substrate.

So there was a certain amount of landscaping carried out by the occupants of White Marl?

Yes, that scraped midden material was dumped in a downslope area along the western side of the site.

There were a few burials, maybe two, on the western side that were in the midden itself. The limestone substrate was below these burials. In contrast, the eastern side burials were in the marl substrate.

They dug into the rock itself?

Yes, into the marl; it’s soft limestone. We also observed that some burials preceded the mounds. From the imprint of these graves, it was clear they were there before the mounds.

So, there was a burial and the midden was formed on top of it?

Yes, the midden was not cut by the burial. The grave was there, and the midden was placed on top.

Was the midden in the form of a mound or was it flat?

It was a mound. We also found that some of those graves in the marl substrate were obviously in the early stage of the midden formation. We used the Harris matrix to identify the sequence of layers and features.

Do you have a sense for how much time was represented between the burial itself and the formation of the midden?

We need C14 dates. In our opinion, White Marl is one of the most significant Amerindian sites in Jamaica. Nowhere in Jamaica do we have another site like it. And there’s a whole lot more at White Marl that’s of scientific value. The areas that we examined were near the existing highway. In the 1940s, the road cut into the site producing nearly vertical walls. Over time, the walls collapsed, thereby exposing and damaging more of the site; much of the site had collapsed along the road. As a result of our 2016 report, an amendment to the proposed highway expansion was issued by the BOT. The amendment disallowed any additional disturbance to the site by highway or factory expansion.

The Board of Trustees came up with this determination?

They indicated that they would not permit any development through the sensitive area. So, there was an amendment by the Jamaica National Works Agency; instead of creating a new road the existing road would be expanded to four lanes.

Wouldn’t that impact the site, then?

That’s why in 2018 we went back to do the evaluation on the other (northern) side. The proposal was for the area that was damaged by the landslide after the 1940s work and squeeze the four-lane traffic through that area.

The idea is that they could design it in such a way that there would be no need to further impact the intact portions of the site?

Exactly, the intact portion of the site.

And only go into the areas that have already been compromised. So, they’re trying to accommodate the historic preservation needs?

When we conducted our assessment, we realized that there is some amount of soil slippage in the site. When we got down to about 1 m in some units gaping cracks were documented; the land started to slip and move.

Cracks in the site itself?

In the site itself. Because there is an area that has already been compromised by landslide; this area is poised for further erosion and landslide.

I don’t know, maybe the engineers would know, is there any way to stabilize it so that it doesn’t further degrade? Use geotextile perhaps?

The proposal is that the highway would come through the compromised area and the engineers would build some reinforced steep walls to prevent further landslides. The 2018 and 2019 excavations were confined to that area.

I am getting the pretty strong sense that in your view the White Marl site is one of the most, if not the most significant pre-colonial sites in Jamaica.

I have not visited other sites in the Caribbean, but I do believe White Marl has much to offer across the region.

Right, I think it’s a site that’s important not only to Jamaica but certainly the Greater Antilles and to the prehistory of the West Indies in general. After Robert Howard (Citation1950) did his work years ago for his PhD, Irving Rouse, who was his professor, modified his chronological charts to include a newly defined White Marl archaeological complex (Rouse, Citation1982). In terms of his broad Caribbean-wide perspective, this enabled him to compare White Marl to other archaeological complexes across the West Indies. Clearly, White Marl has broad regional significance.

It didn’t take us long to realize in looking at some of the pottery there’s a possibility that some of these pots were not made here but were coming from elsewhere.

That’s an interesting observation and one that we have been addressing recently.

We look at pottery texture and colour, but we always said that it required further analysis and I’m sure your investigation will shed some light on that. Going forward, because of the significance of White Marl to Jamaica we have decided that we are not going to subject the site to large-scale excavation.

Preserve it intact?

Preserve and whatever work is to be done has to be organized properly; that is key. Some of the criticism of our reporting has been that it is too descriptive. For us, we need to describe what has been uncovered in as much detail as possible because we lose a whole lot of information if we don’t fully describe a particular unit and then in ten, thirty, or forty years another researcher may ask questions about details of the work. For us at JNHT our work must be sufficiently descriptive.

Like I tell my students, archaeology is a destructive science. When you excavate a unit, even a very controlled excavation unit, you’re still destroying that part of the site and the work needs to be described in great detail.

If you don’t describe it, you lose it and you can’t go back. We need that information for the future.

That makes sense. I guess this could be my last question. What relationship do you see between the White Marl archaeological site and the Taíno Indians today, those who claim ancestry to it, like Chief Kalaan and his people?

As a child, we were told that the Amerindians, the Taínos, were obliterated from the landscape. We grew up believing that. My view has changed. What I have observed is that the first Taínos who came to Jamaica were living mostly in coastal areas and over time migrated from the coastal plain to inland portions of the island.

In terms of pottery styles, the first Jamaican Taínos produced Redware or pottery of the Little River complex?

Yes, the Redware people migrated inland. Perhaps people would be more secure if they were in the uplands. We have seen where some Taíno sites shifted from the windward to the leeward side of a mountain, suggesting that they may have moved for protection from such events as hurricanes.

In terms of working with the highway, especially in this White Marl area, we have seen in some upland Taíno sites, a fusion of Taíno pottery techniques or attributes with African ones. And I am now of the view that some pottery, like of the Maroons, especially represented a miscegenation, the mixing of races, as escaped African slaves migrated further into the hills.

Do you make a distinction between the Maroons and others like Chief Kalaan and his people?

No, we are not able to make that distinction.

So, you would consider the Maroons and the modern-day Taínos in Jamaica to be the same?

It is possible there are people of Maroon descent who believe that they are also of Taíno background.

Do you have any last things you want to say about White Marl or heritage in general?

Just that for a site like White Marl, we need to do the best we can to preserve it in perpetuity.

Right.

Many sites across Jamaica have been destroyed by development so a site like White Marl with intact mounds, middens, and a possible ballcourt needs to be preserved.

White Marl is listed as a National Monument; it’s also a national treasure. Perhaps it should be afforded a level of significance that goes beyond an ‘everyday’ monument?

We have two levels of protection in the Jamaica National Heritage Trust. We have the National Monument and we have Protected National Heritage.

Does one afford a higher level of protection?

Yes, National Monuments receive higher levels of protection.

Thanks very much for taking the time, Mr Walters.

You’re most welcome.

White Marl and the archaeology of place

In his book A Phenomenology of Landscape, Christopher Tilley distinguished between space and place. Spaces are abstract units that may be described, measured, and analysed, whereas places are imbued with memories and settings for action, ‘common experiences, symbols and meanings’ (Tilley, Citation1994: 18). Place ‘names create landscapes’ while an ‘unnamed [location] on a map is quite literally a blank space’ (Tilley, Citation1994: 19, emphasis added). Tilley’s discussion of place relates precisely to Chief Kalaan’s observation above: ‘our community members receive what we call a yamaye-iri, which means “name of the land”. This has a connection to White Marl; it has to have a connection to that place. It is the thread that connects us’.

We will never know what name or names people who occupied the place from c. AD 900 to 1600 used for the locale we now call White Marl. For the original occupants and their descendants this place of ‘White Marl’ became a repository of memories, meanings, significance, and history. The Indigenous people of White Marl actively created sacred and ritualized spaces within this landscape of meaning, at least in the form of burial concentrations and direct cosmological linkages to the spirit world (Mickleburgh, et al., Citation2018; see also Siegel, Citation1996; Citation2010; Curet & Oliver, Citation1998; Oliver, Citation2005; Citation2009).

Likewise, for the later inhabitants of Central Village, White Marl continues to serve as a meaningful place of action, interaction, negotiation, connection, and active memory making. And for the citizens of Central Village this place of White Marl becomes an active stage of connection with the original settlers over 1,000 years ago. Those original settlers followed a belief system called cemíism, which invoked direct communication and interaction with their ancestors (Oliver, Citation2009). Cemíism would have been intimately linked to this place of White Marl. The current residents of Central Village follow a belief system called Christianity, which is also linked to this place of White Marl in the form of their church and Taíno Museum. At the same time, the Jamaican Hummingbird Taíno People also connect to this place of White Marl. It is their ancestors who originally imbued the place with their memories, symbols, and history, which in this twenty-first century provides some sense of continuity in a landscape of meaning.

Conclusions

White Marl is a structurally complex archaeological site. It is equally complex in terms of the varying memories, meanings, and interpretations ascribed to the place over time and by multiple stakeholders. Tensions that frequently exist between archaeologists, descendant communities, and modern residents of an area have not become an overwhelming issue in the case of White Marl. This is largely through the vision of Chief Kalaan and his interest in maintaining good relations with all stakeholders while furthering the goals of ethnic preservation in this twenty-first century globalized world (). Likewise, recent archaeological research and perspectives are increasingly highlighting the interconnectedness of the Taíno world, a form of Indigenous West Indian globalization, in contrast to previous views of Jamaican insularity or ‘marginal retardation’.

Moving forward, White Marl is under threat of destruction by the Government of Jamaica in its interest to widen the Mandela Highway that bisects the site (Ramdial, Citation2017) as well as possible expansion of nearby corporate complexes. The JNHT is doing its best to mitigate the impacts to this heritage resource of significance to different stakeholders (Richards, Citation2006: 85–86; Richards & Henriques, Citation2011). The JNHT Act of 1985 is the implementing legislation that has formalized the agency’s regulatory mandate (http://jnht.com/jnht_act_1985.php).

Compounding the heritage management challenges is how the work is carried out: ‘Unfortunately, the JNHT undertakes much of the work that it seeks to monitor and regulate’ (Richards & Henriques, Citation2011: 31). Ideally, the onus for conducting the necessary heritage studies in advance of proposed development activities should be on the project applicant (e.g., local developer, multinational corporation, public-works agency). As a true regulatory agency, the JNHT would then function in an oversight and quality-control capacity: reviewing and approving heritage-management proposals and ensuring that heritage-resource investigations are carried out following ethically and scientifically sound and agreed-upon plans (Siegel, Citation2011). When such a system is implemented, not only does the onus of conducting required heritage studies shift from the government to the development or permit applicants but it also creates a marketplace for heritage professionals or consultants to seek and carry out the work. Currently, there are very few employment opportunities for students who graduate from UWI-Mona with training in archaeology and heritage management. Requiring project permit applicants to retain the services of qualified heritage-resource consultants would go a long way to insuring a sustainable sector of heritage managers.

Fortunately, local heritage managers and JNHT regulatory staff recognize that the Act of 1985 is woefully dated and lacking in clear and explicit guidance for the consideration, management, and protection of heritage resources on the island. The JNHT Act Sub-Committee was formed in 2018 by the JNHT Trustees in response to the urgent need to revise the existing legislation. In our view, an integrated JNHT cultural heritage management plan that explicitly addresses regulatory oversight will greatly enhance heritage consideration in Jamaica. One of the common frustrations voiced by heritage managers in Jamaica and other Caribbean Island nations has been the lack of government interagency understanding and cooperation regarding critical heritage resources in the face of development pressures (Branford, Citation2011; Farmer, Citation2011; Keegan & Phulgence, Citation2011; Lewis, Citation2011; Murphy, Citation2011; Reid & Lewis, Citation2011; Richards & Henriques, Citation2011; Siegel, Citation2011). A well-developed plan with inter-agency support and compliance could serve as a model for other Caribbean nations and their regulatory and development agencies.

It remains to be seen what the future holds for the White Marl site as a Jamaican, Taíno, and West Indian heritage resource. At this time, the future of the site is at an existential crossroads. If the Government of Jamaica follows the strong recommendations from the UN Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination in formally recognizing Taíno identity, then perhaps the Taíno people today will be in a stronger position to promote the protection of White Marl specifically and pre-colonial Indigenous Jamaican heritage generally. The Taíno people would become a formally recognized voice at the table of consulting parties or stakeholders in project planning and review. In a worst-case scenario, this ‘headless colossus of Jamaican prehistory’ is literally relegated to an increasingly faded memory for the diverse stakeholders, many of whom have found common ground in the place and the only remaining tangible significance of White Marl may reside in boxes of artefacts curated by Jamaica’s cultural institutions.

Acknowledgements

The community engagement efforts reported here were supported by the University of the West Indies, Mona Campus Department of History and Archaeology. The Dean's Office of the Montclair State University College of Humanities and Social Sciences provided valuable support. Siegel’s involvement was made possible through a Fulbright U.S. Scholar grant. We appreciate the openness of the Central Village Christian Rescue Mission and the Yukayeke Yamaye Guani Taíno people under Chief Kalaan’s leadership. We also appreciate the valuable input, assistance, and friendship we received from the wider Central Village community. Staff at the Jamaica National Heritage Trust provided essential input into Jamaican heritage-management policies, especially Executive Director Mrs Michele Creed Nelson and Technical Director of Archaeology Mr Selvenious Walters. Addressing journal reviewers’ comments and especially those of Emlen Myers greatly improved the paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Peter E. Siegel

Peter E. Siegel is Professor of Anthropology at Montclair State University. He is a New World archaeologist and has conducted projects throughout much of the Caribbean, eastern North America, and portions of greater Amazonia. Research interests include the evolution of complex society, historical ecology, cosmological and village spatial organization, and heritage management.Correspondence to: Dr Peter E. Siegel.

Zachary J. M. Beier

Zachary J. M. Beier is a Senior Archaeologist at SEARCH, Inc. He formerly served as the Lecturer in Archaeology at the University of the West Indies, Mona Campus; President of the Archaeological Society of Jamaica; and Trustee on the Board of the Jamaica National Heritage Trust. His research focuses on the archaeology and heritage of the Caribbean at both prehistoric and historical sites, and, principally, colonialism and the diversity of human encounters in the emergent modern world.

Kalaan Nibonrix Kaiman

Kalaan Nibonrix Kaiman is Kasike (Chief) of Yamaye Gunaí Taíno Peoples (Jamaican Hummingbird Taíno People). He is also the Caribbean Region Organizer for Peace and Dignity Journeys (an inter-tribal prayer run) and holds memberships in the Council of Indigenous Traditional Healers of the Americas, Yamaye Council of Indigenous Healers (YCOIL), and the Caribbean Organization of Indigenous Peoples. Chief Kalaan is an Indigenous rights activist and promotes recognition of his people in Jamaica as well as the rights of Indigenous peoples across the West Indies and globally. He is the custodian of Yamaye/Jamaican Taíno traditions and represents YCOIL at the United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination and at the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (an entity of the Organization of American States).

Notes

1 Lokono Amerindians are Arawakan speakers native to north-eastern South America. Warao Amerindians are native to the Orinoco delta. Caribbean archaeologists generally believe that Arawakan speakers dispersed out of the Orinoco Valley into the West Indies no later than c. 500 BC represented by the Saladoid series of cultures (Lathrap, Citation1970; Rouse, Citation1992; Siegel, Citation2010).

2 The Taíno diaspora has been discussed at length by a number of scholars and activists (e.g., Dávila, Citation2001; Forte, Citation2005; Citation2006; Haslip-Viera, Citation2001; Martínez-San Miguel, Citation2011).

3 In Taíno mythology, the iguana was a cosmologically important creature linked to a sacred cave called Iguanaboina, from which the Sun and Moon emerged (Pané, Citation1999: Chapter XI).

References

- Agorsah, E. K., ed. 1994. Maroon Heritage: Archaeological, Ethnographic and Historical Perspectives. Kingston, Jamaica: University of the West Indies Press.

- Allsworth-Jones, P. 2008. Pre-Columbian Jamaica. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press.

- Atkinson, L.-G. ed. 2006. The Earliest Inhabitants: The Dynamics of the Jamaican Taíno. Kingston, Jamaica: University of the West Indies Press.

- Atkinson, L.-G. M. 2019. Buréns, Cooking Pots and Water Jars: A Comparative Analysis of Jamaican Prehistory. PhD dissertation, University of Florida.

- Bailey, G. 2007. Time Perspectives, Palimpsests & the Archaeology of Time. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, 26: 198–223.

- Branford, M. E. 2011. Saint Lucia. In: P. E. Siegel & E. Righter, eds. Protecting Heritage in the Caribbean. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, pp. 90–95.

- Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination. 2022. Concluding Observations on the Combined Twenty-First to Twenty-Fourth Periodic Reports of Jamaica. CERD/C/JAM/CO/21–24. International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination. Geneva: United Nations.

- Cundall, F. 1920. Richard Hill. The Journal of Negro History, 5(1): 37–44.

- Curet, L. A. & Hauser, M. W., eds. 2011. Islands at the Crossroads: Migration, Seafaring, and Interaction in the Caribbean. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press.

- Curet, L. A. & Oliver, J. R. 1998. Mortuary Practices, Social Development, and Ideology in Precolumbian Puerto Rico. Latin American Antiquity, 9: 217–39.

- Dávila, A. 2001. Local/Diasporic Taínos: Towards a Cultural Politics of Memory, Reality, and Imagery. In: G. Haslip-Viera, ed. Taíno Revival. Critical Perspectives on Puerto Rican Identity and Cultural Politics. Princeton: Marcus Wiener, pp. 33–53.

- D’souza, N. A., Guzder, J., Hickling, F., & Groleau, D. 2018. The Ethics of Relationality in Implementation and Evaluation Research in Global Health: Reflections from the Dream-A-World Program in Kingston, Jamaica. BMC Medical Ethics, 19(Suppl 1): 50. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-018-0282-5.

- Duerden, J. E. 1897. Aboriginal Indian Remains in Jamaica. Journal of the Institute of Jamaica, II(4): 1–53.

- Elliott, S., Maezumi, S. Y., Robinson, M., Burn, M., Gosling, W. D., Mickleburgh, H. L., Walters, S. & Beier, Z. J. M. 2022. The Legacy of 1300 Years of Land Use in Jamaica. Journal of Island and Coastal Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.1080/15564894.2022.2078448.

- Farmer, K. 2011. Barbados. In: P. E. Siegel & E. Righter, eds. Protecting Heritage in the Caribbean. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, pp. 112–24.

- Flewellen, A. O., Dunnavant, J. P., Odewale, A., Jones, A., Wolde-Michael, T., Crossland, Z. & Franklin, M. 2021. ‘The Future of Archaeology Is Antiracist’: Archaeology in the Time of Black Lives Matter. American Antiquity, 86(2): 224–43.

- Forte, M. C. 2005. Extinction: The Historical Trope of Anti-Indigeneity in the Caribbean. Issues in Caribbean Amerindian Studies, VI(4): 1–24.

- Forte, M. C., ed. 2006. Indigenous Resurgence in the Contemporary Caribbean: Amerindian Survival and Revival. New York: Peter Lang.

- Franklin, M., Dunnavant, J. P., Flewellen, A. O. & Odewale, A. 2020. The Future Is Now: Archaeology and the Eradication of Anti-Blackness. International Journal of Historical Archaeology, 24: 753–66.

- González-Tennant, E. 2018. Anarchism, Decolonization, and Collaborative Archaeology. Journal of Contemporary Archaeology, 5(2): 238–44.

- Gosse, P. H. & Hill, R. 1851. A Naturalist’s Sojourn in Jamaica. London: Longman, Brown, Green and Longmans.

- Grange, O. 2022. Ministry of Culture, Gender, Entertainment and Sport Jamaica’s Presentation of its Combined 21st, 22nd and 23rd Report to the 108th Session of the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination. Geneva: United Nations.

- Harrington, M. R. 1921. Cuba Before Columbus. Indian Notes & Monographs. New York: Heye Foundation, Museum of the American Indian.

- Haslip-Viera, G., ed. 2001. Taíno Revival. Critical Perspectives on Puerto Rican Identity and Cultural Politics. Princeton: Marcus Wiener.

- Higman, B. W. 1988. Jamaica Surveyed: Plantation Maps and Plans of the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries. Kingston: Institute of Jamaica Publications.

- Hill, R. 1859. Lights and Shadows of Jamaica History; Being Three Lectures Delivered in Aid of the Mission Schools of the Colony. Kingston: The Educational Repository for Jamaica, Ford & Gall.

- Hill, R. 1860. Sketches of the Natural History of Jamaica. The Jamaica Quarterly Journal of Medicine, Science, and Arts Series 1, Vol. 3: 49–52.

- Hofman, C. L. & van Duijvenbode, A., eds. 2011. Communities in Contact: Essays in Archaeology, Ethnohistory & Ethnography of the Amerindian Circum-Caribbean. Leiden: Sidestone Press.

- Hofman, C. L. & Hoogland, M. L. P. 2016. Connecting Stakeholders: Collaborative Preventive Archaeology Projects at Sites Affected by Natural and/or Human Impacts. Leiden University Scholarly Publications, 5(1): 1–31.

- Howard, R. R. 1950. The Archaeology of Jamaica and its Position in Relation to Circum-Caribbean Culture. PhD dissertation, Yale University.

- Howard, R. R. 1956. The Archaeology of Jamaica: A Preliminary Survey. American Antiquity, 22: 45–59.

- Howard, R. R. 1965. New Perspectives on Jamaican Archaeology. American Antiquity, 31: 250–55.

- Hussey-Whyte, D. 2012. White Marl Historic, But Not Good for Museum. Jamaica Observer [online] 21 October 2012. Available at: https://www.jamaicaobserver.com/news/white-marl-historic-but-not-good-for-museum/.

- Jamaica Observer. 2022. 76-Y-O Among Two Shot in Central Village. Jamaica Observer [online] 12 May 2022. Available at: https://www.jamaicaobserver.com/latest-news/76-y-o-among-two-shot-in-central-village/.

- Keegan, W. F. & Phulgence, W. 2011. Patrimony or Patricide? In: P. E. Siegel & E. Righter, eds. Protecting Heritage in the Caribbean. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, pp. 143–51.

- Keegan, W. F., Hofman, C. L. & Rodríguez Ramos, R., eds. 2013. The Oxford Handbook of Caribbean Archaeology. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Kroeber, A. L. 1948. Anthropology: Race, Language, Culture, Psychology, Prehistory. Revised ed. New York: Harcourt, Brace.

- Lathrap, D. W. 1970. The Upper Amazon. Southampton: Thames & Hudson.

- Lewis, P. E. 2011. St. Vincent and the Grenadines. In: P. E. Siegel & E. Righter, eds. Protecting Heritage in the Caribbean. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, pp. 96–105.

- Lovén, S. 1935. Origins of the Tainan Culture, West Indies. Göteborg: Elanders Bokfryckeri Akfiebolag.

- Lucas, G. 2005. The Archaeology of Time. New York: Routledge.

- Martínez-San Miguel, Y. 2011. Taíno Warriors? Strategies for Recovering Indigenous Voices in Colonial and Contemporary Hispanic Discourses. CENTRO Journal, XXIII(1): 197–215.

- Mickleburgh, H. L., Laffoon, J. E., Pagán Jiménez, J. R., Mol, A. A. A., Walters, S., Beier, Z. J. M. & Hofman, C. L. 2018. Precolonial/Early Colonial Human Burials from the Site of White Marl, Jamaica: New Findings from Recent Rescue Excavations. International Journal of Osteoarchaeology, 2018: 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1002/oa.2707.

- Mol, A. A. A. 2014. The Connected Caribbean: A Socio-Material Network Approach to Patterns of Homogeneity and Diversity in the Pre-Colonial Period. Leiden: Sidestone Press.

- Murphy, R. 2011. Antigua and Barbuda. In: P. E. Siegel & E. Righter, eds. Protecting Heritage in the Caribbean. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, pp. 73–79.

- Oliver, J. R. 2005. The Proto-Taíno Monumental Cemís of Caguana: A Political Religious ‘Manifesto’. In: P. E. Siegel, ed. Ancient Borinquen: Archaeology and Ethnohistory of Native Puerto Rico. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, pp. 230–84.

- Oliver, J. R. 2009. Caciques and Cemí Idols: The Web Spun by Taíno Rulers between Hispaniola and Puerto Rico. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press.

- Ostapkowicz, J. 2015. The Sculptural Legacy of the Jamaican Taíno, Part 1: The Carpenter’s Mountain Carvings. Jamaica Journal, 35(3): 52–59.

- Ostapkowicz, J., Bronk Ramsey, C., Brock, F., Higham, T., Wiedenhoeft, A. C., Ribechini, E., Lucejko, J. J. & Wilson, S. 2012. Chronologies in Wood and Resin: AMS 14C Dating of Pre-Hispanic Caribbean Wood Sculpture. Journal of Archaeological Science, 39: 2238–51.

- Ostapkowicz, J., Bronk Ramsey, C., Brock, F., Cartwright, C., Stacey, R. & Richards, M. 2013. Birdmen, Cemis and Duhos: Material Studies and AMS 14C Dating of Pre-Hispanic Caribbean Wood Sculptures in the British Museum. Journal of Archaeological Science, 40: 4675–87.

- Ostapkowicz, J., Brock, F., Wiedenhoeft, A. C., Snoeck, C., Pouncett, J., Baksh-Comeau, Y., Schulting, R., Claeys, P., Mattielli, N., Richards, M. & Boomert, A. 2017. Black Pitch, Carved Histories: Radiocarbon Dating, Wood Species Identification and Strontium Isotope Analysis of Prehistoric Wood Carvings from Trinidad’s Pitch Lake. Journal of Archaeological Science Reports, 16: 341–58.

- Pané, R. 1999. An Account of the Antiquities of the Indians. Trans. J. J. Arrom. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Parker, P. L. 1993. Traditional Cultural Properties: What You Do and How We Think. CRM, 16: 1–5.

- Parker, P. L. & King, T. F. 1990. Guidelines for Evaluating and Documenting Traditional Cultural Properties. National Register Bulletin 38. Washington, DC: Interagency Resources Division, National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior.

- Pradeau, A. F. 1938. Numismatic History of Mexico from the Pre-Columbian Epoch to 1823. Los Angeles: A. F. Pradeau.

- Rainey, F. G. 1940. Porto Rican Archaeology. Scientific Survey of Porto Rico and the Virgin Islands. Vol. XVIII, Part 1. New York: The New York Academy of Sciences.

- Ramdial, L. 2017. Major Infrastructure Development Programme (MIDP), Mandela Highway Improvement Project. Report on file. National Works Agency, Kingston, Jamaica. https://www.nwa.gov.jm/major-projects.

- Reid, B. A. & Lewis, V. 2011. Trinidad and Tobago. In: P. E. Siegel & E. Righter, eds. Protecting Heritage in the Caribbean. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, pp. 125–33.

- Richards, A. 2006. The Impact of Land-Based Development on Taíno Archaeology in Jamaica. In: L.-G. Atkinson, ed. The Earliest Inhabitants: The Dynamics of the Jamaican Taíno. Kingston, Jamaica: University of the West Indies Press, pp. 75–86.

- Richards, A. & Henriques, A. 2011. Jamaica. In: P. E. Siegel & E. Righter, eds. Protecting Heritage in the Caribbean. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, pp. 26–34.

- Rouse, I. 1948. The Arawak. In: J. H. Steward. The Circum-Caribbean Tribes. Handbook of South American Indians Bull. 143. Washington, D.C.: Bureau of American Ethnology, Smithsonian Institution, pp. 507–65.

- Rouse, I. 1967. Robert Randolph Howard, 1920–1965. American Antiquity 32: 223–24.

- Rouse, I. 1982. Ceramic and Religious Development in the Greater Antilles. Journal of New World Archaeology, 5(2): 45–55.

- Rouse, I. 1986. Migrations in Prehistory: Inferring Population Movement from Cultural Remains. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Rouse, I. 1992. The Tainos: Rise and Decline of the People Who Greeted Columbus. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Rouse, I. & Allaire, L. 1978. Caribbean. In: R. E. Taylor & C. W. Meighan, eds. Chronologies in New World Archaeology. New York: Academic Press, pp. 431–81.

- Sheffield, M. 1755. A New Map of Jamaica in Which the Several Towns, Forts, and Settlements are Accurately Laid Down as Well as ye Situations & Depts of ye Most Noted Harbours & Anchoring Places, Withe Limits & Boundarys of the Different Parifhes as They Have Been Regulated by Law or Settled by Custom; the Greatest Part Drawn or Corrected from Actual Surveys. London: Carrington Bowles. https://www.loc.gov/resource/g4960.ar191600/?r=0.886,0.487,0.131,0.057,0.

- Shev, G., Thomas, R. & Beier, Z. 2022. Zooarchaeological and Isotopic findings from White Marl, Jamaica: Insights on Indigenous Human-Animal Interactions and Evidence for the Management of Jamaican Hutias. Journal of Caribbean Archaeology, 22: 1–30.

- Siegel, P. E. 1996. Ideology and Culture Change in Prehistoric Puerto Rico: A View from the Community. Journal of Field Archaeology, 23: 313–33.

- Siegel, P. E. 2010. Continuity and Change in the Evolution of Religion and Political Organization on Pre-Columbian Puerto Rico. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, 29: 302–26.

- Siegel, P. E. 2011. Protecting Heritage in the Caribbean. In: P. E. Siegel & E. Righter, eds. Protecting Heritage in the Caribbean. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, pp. 152–62.

- Siegel, P. E., Hofman, C. L., Bérard, B., Murphy, R., Ulloa Hung, J., Valcárcel Rojas, R., & White, C. 2013. Confronting Caribbean Heritage in an Archipelago of Diversity: Politics, Stakeholders, Climate Change, Natural Disasters, Tourism, and Development. Journal of Field Archaeology, 38: 376–90.

- Silverberg, J., Vanderwal, R. L. & Wing, E. S. 1972. The White Marl Site in Jamaica: Report of the 1964 Robert R. Howard Excavation. Manuscript on file. Milwaukee: Department of Anthropology, University of Wisconsin.

- Sinelli, P. T. 2013. Meillacoid and the Origins of Classic Taíno Society. In: W. F. Keegan, C. L. Hofman, & R. Rodríguez Ramos, eds. The Oxford Handbook of Caribbean Archaeology. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 221–31.

- St. Clair, J. 1970. Problem Oriented Archaeology. Jamaica Journal, 4(1): 7–10.

- Steward, J. H. 1948. The Circum-Caribbean Tribes: An Introduction. In: J. H. Steward, ed. The Circum-Caribbean Tribes. Handbook of South American Indians Bull. 143. Washington, D.C.: Bureau of American Ethnology, Smithsonian Institution, pp. 1–41.

- Thomas, D. A. 2011. Exceptional Violence: Embodied Citizenship in Transnational Jamaica. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Thomas, D. A. 2019. Political Life in the Wake of the Plantation: Sovereignty, Witnessing, Repair. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Tilley, C. 1994. A Phenomenology of Landscape: Places, Paths and Monuments. Oxford: Berg.

- Vanderwal, R. L. 1968. The Prehistory of Jamaica: A Ceramic Study. Master’s thesis, University of Wisconsin.

- Weekend Star. 1990. Political Activists, Gunmen Take Over Indian Village: Revival of Interest Needed in Arawak Museum. The Weekend Star, 9 March 1990, p. 7.

- Williams, P. H. 2019. Jamaica Gets First Taino Chief in Over 500 Years. The Gleaner [online], 19 June 2019. Available at: https://jamaica-gleaner.com/article/news/20190619/jamaica-gets-first-taino-chief-over-500-years

- Zimmerman, L. J. & Dawn Makes Strong Move. 2008. Archaeological Taxonomy, Native Americans, and Scientific Landscapes of Clearance: A Case Study from Northeastern Iowa. In: A. Smith and A. Gazin-Schwartz, eds. Landscapes of Clearance: Archaeological and Anthropological Perspectives. Walnut Creek, California: Left Coast Press, pp. 190–211.