ABSTRACT

The Duterte administration in the Philippines displayed broad hostility towards civil rights. Yet its approach to specific civil rights issues varied significantly. This paper analyses this variation by focusing on two cases: the lowering of the minimum age of criminal responsibility and extra-judicial killings in the war on drugs. In both cases, Duterte and his allies sought to enact and implement policies that infringed civil rights, yet they only succeeded in the latter. The nature and role of mediating coalitions — configurations of actors that opposed, supported, or disengaged from efforts by Duterte and his allies to undermine civil rights — were the key determinants of this variation. The government backed down on lowering the minimum age of criminal responsibility because unified rights groups were supported by sections of the oligarchic elite. But it conducted, incited, and persisted with extra-judicial killings in the war on drugs due to fragmentation among rights groups and an absence of significant support for these groups from oligarchic elites. This variation has significant implications for how scholars understand the politics of civil rights in the Philippines, particularly during the Duterte presidency, as well as strategies to better protect civil rights in the country.

Introduction

The presidency of Rodrigo Duterte in the Philippines (from 2016 to 2022) witnessed an unprecedented level of civil rights violations.Footnote1 Yet there was also significant variation in his administration’s approach to specific civil rights issues. On the one hand, the police, military, and vigilante groups carried out between 6,000 and 27,000 extra-judicial killings in what Duterte called a “war on drugs.”Footnote2 The Duterte administration also attacked and sought to shut down news organizations and journalists critical of his policies;Footnote3 red-tagged,Footnote4 threatened, and in some cases killed rights activists;Footnote5 and enacted an anti-terrorism law containing provisions on warrantless arrests and detention which violated due process rights.Footnote6 Duterte and his allies repeatedly pushed Congress to reinstate capital punishment, which had been abolished in the Philippines in 2006, and to lower the minimum age for criminal responsibility to below fifteen years of age, but these efforts failed. On the other hand, his administration also supported legislation raising the minimum age of sexual consent to sixteen yearsFootnote7 and recognized abandoned children as natural-born citizens, giving them access to government-funded care and services.Footnote8 In addition, his administration advanced education and healthcare rights by enacting a law giving 2.46 million Filipino students free college education,Footnote9 expanded access to national health insurance, and increased conditional cash transfers.Footnote10

What explains this variation in the Duterte administration’s approach to civil rights issues? This paper addresses this question by examining the political dynamics surrounding two issues: the lowering of the minimum age of criminal responsibility and extra-judicial killings in the war on drugs. In both cases, Duterte and his allies promoted an anti-rights stance consistent with a populist political strategy that helped him attract a significant degree of popular support.Footnote11 Throughout his six year term in office, Duterte’s approval ratings rarely fell below eighty percent, with equal support from different geographic groups and social classes in the Philippines.Footnote12 His administration backtracked on its legislative attempts to lower the minimum age of criminal responsibility because rights groups were united in their opposition to these attempts and had the support of key segments of the oligarchic elite. By contrast, the administration conducted, incited, and persisted with extra-judicial killings in the war on drugs because rights groups failed to adopt a unified position on this issue, and those opposing the war on drugs lacked the support of oligarchic elites. These different coalitional patterns translated into different positions on the part of the Philippines Congress, which blocked rights-unfriendly policy changes in the former case and facilitated such changes in the latter. This outcome, we suggest, has significant implications for how we understand the politics of civil rights in the Philippines, particularly during the Duterte administration, and strategies for protecting civil rights going forward.

We begin by examining how scholars have so far understood the politics of civil rights in the Philippines under Duterte and presenting a critique of their approach. We then examine the main sets of actors who engaged with Duterte’s efforts to undermine civil rights, analyze how they did so, and discuss the consequences of their actions. In our conclusion, we consider the implications of our analysis in conceptual and practical terms.

Before beginning, however, it is necessary to address an important definitional issue. Civil rights, as we use this term, are rights that governments provide to citizens and are defined in law. In the Philippines, civil rights refer to rights and freedoms that Filipinos are legally entitled to because they are enshrined in the 1987 Philippine Constitution (especially Articles III, Bill of Rights and XIII, Social Justice and Human Rights) and other domestic legal instruments like the Anti-Torture Act of 2009 and the Juvenile Justice and Welfare Act of 2006. Civil rights are distinct from human rights – rights and freedoms that people acquire simply by virtue of being human – because they “must be given and guaranteed by the power of the state.”Footnote13 In international human rights law, civil and political rights are often distinguished from social and economic rights on the grounds that the former refer to “classic liberty rights against interference by the State, such as freedom of speech, freedom from arbitrary arrest, freedom of religion, the right to vote, and freedom from torture” while the latter “refer to protection against the vicissitudes of life, such as poverty, ill health, old age, or other economic conditions, which are not directly a result of interference by the State, but capable of being corrected by the State.”Footnote14 In examining the politics of civil rights in the Philippines, our focus is on civil and political rights rather than social and economic rights, although we acknowledge that both sets of rights may be provided to citizens by a government; some rights – for instance, the right to education – are generally considered to fall into both categories; and civil and political rights have been found in some jurisdictions to give rise to corresponding social and economic rights, indicating a degree of overlap between the two categories.Footnote15

Understanding the politics of civil rights in the Philippines under Duterte

Much of the literature on Philippine politics during the Duterte period has emphasized Duterte’s populist political strategy and how it undermined democracy and fuelled violence.Footnote16 Richard Heydarian has argued that Duterte engaged in a new form of grievance politics based on “a raging exasperation with the liberal elite, who dominated the post-Marcos regime” and an appeal to a long-suffering “people,” defining elements of a populist strategy.Footnote17 This strategy, Heydarian claims, was extremely popular with the voting public, enabling Duterte not only to win office but to maintain “mind-blowing” popular support throughout his term in office.Footnote18 It also undermined democracy by creating a climate of fear within the country and discouraging opponents from attempting “to check [Duterte’s] power” and “fight for democratic principles.”Footnote19 In general, such analyses suggest that the Duterte administration’s approach to civil rights was driven from the top down, reflecting his populist political approach. Paul Kenny argues that Duterte’s drug war was part of his populist politics of being tough on crime.Footnote20 Similarly, Nicole Curato has described Duterte as a “penal populist,” drawing attention to how he gave police shoot-to-kill orders, offered to pardon officers charged with civil rights abuses, and argued for the reintroduction of the death penalty.Footnote21 This populist, performative, and personality-focused lens on the Duterte administration’s civil rights abuses also extended to coverage of these abuses by international and local media outlets. In an investigative report for the New York Times, Daniel Berehulak traced the drug war killings to Duterte’s populist pronouncementsFootnote22 while Sheila Coronel examined how Duterte’s “license to kill” proclamations translated to police receiving cash incentives for every alleged drug user killed.Footnote23 Using accounts from survivors, vigilantes, and police, Patricia Evangelista concluded that the killings were a result of Duterte’s pronouncements and policies.Footnote24 Charmaine Ramos has argued that Duterte’s populist strategy explains the apparent different approaches of his administration to civil, political, social, and economic rights. Violations of civil and political rights and social policy reforms, she contends, complemented one another to the extent that the latter legitimized the former.Footnote25

Such analyses have been characterized by two important absences. The first relates to the role of bottom-up pressures in shaping Duterte’s approach to civil rights issues. Ronald Pernia has pointed to the ways in his administration’s policies resonated with non-liberal values widely held among the Filipino public.Footnote26 In an updated version of her penal populism approach, Nicole Curato similarly emphasized the role of “populist publics,” arguing that Duterte’s populist strategy was made possible by the fact that Filipinos gave him “negotiated and contingent” support.Footnote27 Adele Webb has noted that the Philippine middle class shares ideas of “democratic ambivalence,” arguing that their support for Duterte was not a rejection of democracy but a “negotiated response to the experience and observation of how democracy works.”Footnote28 These perspectives help to explain the popularity of Duterte’s campaign against civil rights, but they have obscured the concrete actions taken by rights groups to contest this campaign. Such contestation, as Nathan Quimpo among others has noted, has been a key feature of Philippine politics in the post-Marcos era, reflecting the fact that democratization has provided greater scope for rights groups to mobilize for collective action and influence policymaking.Footnote29 To this extent, the notion of populist publics only goes part of the way towards providing a bottom-up account of the politics of civil rights during the Duterte presidency.

The second absence relates to the role of oligarchic elites. The Philippines has been dominated for many decades by a powerful oligarchy whose interests span politics, the bureaucracy, and commerce (see below). Scholars such as Richard Heydarian and Ramon Casiple have noted the oligarchic nature of Filipino politics but framed Duterte’s rise to power and actions while in government as a populist revolt against this elite, echoing statements by Duterte himself.Footnote30 By portraying Duterte as opposed to and having power over the oligarchic elite, they have reinforced the notion that his administration’s actions vis-à-vis civil rights issues were largely the product of his populist political strategy rather than something forged through interactions with this elite. This is problematic to the extent that oligarchic elites have nuanced interests vis-à-vis civil rights. Analysts have shown that, while the country’s oligarchic elites have been broadly opposed to civil rights, some have supported reform and social change if it has not threatened their interests or if these has benefited them in some way.Footnote31 In addition, oligarchic elites have participated in civil rights-related policymaking. These factors mean that they have the potential to tilt the balance of power one way or another in struggles over civil rights issues, making them an important determinant of the Duterte administration’s actions on these issues. Their mediating role — like that of rights groups — is largely missing from existing accounts of the politics of civil rights under Duterte.

Our broader point here, then, is that to fully explain the Duterte government’s approach to specific civil rights issues, and specifically its varied treatment of different issues, scholars need to examine not only how Duterte’s populist political strategy led to efforts by he and his allies to undermine civil rights or legitimized them through use of social policy measures.Footnote32 We also need to examine how these efforts intersected with varying degrees of pushback, acceptance, or disengagement from oligarchic elites and rights groups.

Oligarchic elites and rights groupsFootnote33

Oligarchic elites consist of powerful politico-business families and senior officials in the bureaucracy, military, and police. These elites were nurtured under Spanish and American colonial rule, when a set of regionally based families secured control over vast swathes of land and later the Philippine Assembly, a representative body created by the American colonial administration. When the country became independent in July 1946, these families maintained their political pre-eminence, dominating the state apparatus and extending their economic interests into new domains. During the Ferdinand Marcos era (from 1965 to 1986), characterized by a military-backed dictatorship, traditional elite families were sidelined or co-opted, and a new cohort of powerful families personally linked to Marcos emerged. However, the traditional pattern of oligarchic rule was restored with the return to democratic rule in 1986, with the notable difference that the Marcos family and their cronies remained a key section of the oligarchy.Footnote34 Throughout the post-independence period, some of these powerful families focused on growing their political power at the national and local levels with great success while others focused more on developing their business interests.Footnote35 The election of Duterte has often been framed as a populist revolt against this elite, as noted earlier. Yet, his victory is better understood as a partial break with elite rule, like the Marcos period, to the extent that certain traditional oligarchic elites were sidelined while others were empowered, particularly those with Duterte and Mindanao connections.Footnote36 The catchphrase “Marcos cronies” described elites who benefitted from their friendship with Ferdinand Marcos in terms of political favors and business monopolies. This group included a dozen or so individuals such as business tycoon Lucio Tan, who held a monopoly on the tobacco market in the country and later expanded into liquor and airlines, and Eduardo Cojuangco Jr., who used his profits from a coconut levy to purchase the San Miguel Corporation. Likewise, businesspeople close to Duterte have been labelled “Duterte-garchs.” In both cases, these cronies stand in contrast to the traditional elites whose wealth began with land accumulation during the colonial era and subsequently expanded into the manufacturing and services sectors, among others, such as the Ayala, Aboitiz, and Lopez families.Footnote37

In addition to the distinction between traditional and new members of the oligarchy, there is a distinction between elite families concentrated at the national scale in Manila and those based in rural areas. While national elites have vied for political favors and economic concessions from the national government to capture key industries, provincial elites have maintained their power through the exercise of political violence and rent-seeking at the local level.Footnote38 Political violence in the provinces has been part of what John Sidel has called “bossism,” whereby local elites function as bosses who wield “coercive pressures” and hold “local power monopolies in electoral politics and social relations” to forge and maintain political dynasties.Footnote39 Rent-seeking traditionally has been linked to land ownership,Footnote40 but in recent decades this has taken additional forms including “commercial networks, logging or mining concessions, transportation companies, and/or control over illegal economic activities.”Footnote41 Provincial elites dominate local assemblies and executive offices and participate in national politics by running for seats in the House of Representatives.

Elite family rule has been sustained over the decades by support from key elements in the state apparatus. In particular, the Philippines’ bureaucracy, police, and military have been “a by-product of the long, historical development of elitist power structures,”Footnote42 serving to protect the interests of elite families by intimidating opponents, suppressing dissent, facilitating rent-seeking, and turning a blind eye to these families’ criminal activities.Footnote43

The political elite’s enduring control of the state is most evident in the House of Representatives. Approximately seventy-four percent of elected members in the House come from political dynasties, with all eighty-one provinces having political families of varying political prominence.Footnote44 Elite participation in Congress is distinguished by what in the Philippines is called “turncoatism,” whereby “an issue or class-based party system does not exist.”Footnote45 Party loyalties are always shifting. Before Duterte’s election in 2016, for instance, his party, Partido Demokratiko Pilipino-Lakas ng Bayan (PDP-Laban), had three seats in the House. As a result of the 2016 elections, it was able to form a coalition of nearly 260 of the 297 representatives.Footnote46 This supermajority was formed by creating alliances with other major parties including the Nationalist Party, the Nationalist People’s Coalition, and even the Makabayan Bloc of the national democratic left, as well as with some members of the Liberal Party, which saw at least fifty incumbents switch affiliation to PDP-Laban.Footnote47 These alliances with other parties extended to the Senate, where Duterte’s party had a coalition of twenty-one of the twenty-four members, including four senators from outgoing President Benigno Aquino III’s Liberal Party, who were part of the supermajority until they were ousted by their colleagues in the Senate majority in February 2017.Footnote48 Following the 2019 midterm elections, Duterte’s coalition held 268 out of the 304 seats in the House and twenty out of the twenty-four seats in the Senate.

The oligarchic elite has generally been hostile towards civil rights norms and enforcement. For instance, Philippine journalists have been “continually undermined by political and business elites” and subject to intimidation and threats.Footnote49 Likewise, local government officials “are often more interested in protecting the holdings of local elites than the lives and land rights of peasants.”Footnote50 Big business groups have been linked to a wide range of civil rights abuses, especially in the provinces, including killings, abuses related to justice delivery to victims, abuses of health rights, and environmental degradation.Footnote51 At the same time, however, some oligarchic elites have supported specific rights issues when these have served, or at least not significantly threatened, their interests. For instance, Yoon Ah Oh has argued that the Philippine government was able to implement reforms protecting the rights of overseas Filipino workers because elites “realized that migration was a low-threat political agenda that largely left intact their vested interests.”Footnote52 Similarly, some business elites supported the opposition campaign against Duterte’s attempt to reinstate capital punishment because bringing back the death penalty would mean losing tariff concessions in the European Union’s Generalized Scheme of Preferences.Footnote53 Although many major companies have investments in industries such as agriculture and plantations that are often reliant on child labor, some business elites have provided a degree of support for the promotion of children’s rights because they can present their support as fulfilment of their corporate social responsibilities.Footnote54 However, business elites have been selective in openly campaigning for children’s rights, adopting positions that do not directly threaten their own interests or challenge the government.Footnote55

Rights groups include subaltern elements such as workers, peasants, the urban poor, Indigenous communities, and other vulnerable and marginalized communities and their allies in local and international non-government organizations (NGOs), international bilateral and multilateral organizations, leftist movements, the Catholic Church, and sympathetic parts of the state apparatus. If oligarchic elites have generally shown hostility towards rights norms, this set of actors has generally supported these norms, albeit for distinct reasons and to different extents. Subaltern elements are the main victims of rights abuses, particularly ones that occur in the context of conflicts over land, natural resources, the war on drugs, wages, conditions of employment, and the application of justice.Footnote56 They have accordingly been strong supporters of civil rights norms, often framing their demands for changes in terms of these norms and supporting efforts to enhance legal protection and enforcement of civil rights.Footnote57 These elements are commonly represented in struggles over rights by trade unions, peasant/farmer organizations, Indigenous organizations, grassroots development organizations, and peoples organizations (POs), bodies which are “composed of disadvantaged individuals (who) work to advance their members’ material or social well-being.”Footnote58 Operating though such organizations as well as through smaller, more disorganized and localized groups and networks, subaltern elements have sought to promote civil rights causes by engaging in protests and demonstrations, taking industrial actions, launching legal cases, attracting media attention, appealing to international organizations, and seeking accountability against perpetrators of rights abuses.Footnote59

Local NGOs include groups such as Karapatan Alliance (the country’s leading human rights coalition), ANGOC (a body concerned with agrarian reform and land rights), the Child Rights Network (a nationwide network of NGOs, people’s organizations, church groups, current and former legislators, and sympathetic government agencies committed to promoting child rights), Philippine Action for Youth Offenders (an NGO linked to the Catholic Church), and the Coalition Against the Death Penalty (a religious-based group promoting the rights of persons deprived of liberty). In contrast to groups such as trade unions, these alliances do not try to directly represent the interests of their members so much as support them in their struggles, their base of support being mainly among the middle class and international organisations.Footnote60 Local NGOs commonly receive funding and support from international organizations such as Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, and Oxfam, as well as international bilateral and multilateral organizations such as the United Nations, the European Union, and some bilateral foreign aid agencies. Collectively, these bodies have assisted subaltern elements in their struggles over civil rights by promoting awareness of rights issues and socialization of rights norms, reporting abuses, lobbying government officials, providing technical expertise to government bodies and POs, serving as intermediaries between POs and the state, and facilitating legal action through the provision of financial support and legal expertise.Footnote61

Leftist movements include the National Democratic Left and the Social Democratic Left. The former is composed of the Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP) and its plethora of underground and front organizations. Since the 1986 People Power Revolution that toppled Ferdinand Marcos, the CPP has actively engaged in electoral politics through the National Democratic Front, winning a small number of seats each election, while carrying out guerrilla warfare in the hinterlands through the New People’s Army.Footnote62 The National Democratic Front frames its actions as anti-imperialist and anti-neoliberal, reflective of its Marxist-Leninist-Maoist ideology.Footnote63 The Makabayan Bloc, a coalition of twelve party-lists aligned with the National Democratic Front, won three out of sixty-seven party-list seats in the 2022 elections, a decline from a high of seven seats in each of the 2010, 2013, and 2016 elections.

The Catholic Church’s influence comes from the enduring Spanish colonial legacy in the Philippines. Currently, around eighty-six percent of Filipinos identify as Catholic.Footnote64 Since the Spanish colonial era, the Church has been a key actor in social movements with “a major stake in safeguarding – and sacralizing – the leadership … of civil society.”Footnote65 The Church justifies its political intervention in all levels of Filipino life “by assuming the position of a non-partisan moral arbiter, a social actor tasked to ensure that moral correctness in all aspects of everyday life” is maintained.Footnote66 However, the Church’s engagement with rights issues is selective. On the one hand, it has sought to promote civil rights in relation to issues like the death penalty and extra-judicial killings. On the other, it has challenged sexual and reproductive rights that oppose its doctrine of the sanctity of life. In this latter respect, the Church’s interventions have “been one of the major hindrances to further democratic deepening.”Footnote67

The final element among rights groups is government agencies like the Commission on Human Rights, the Juvenile Justice and Welfare Council, and the Council for the Welfare of Children. Under Philippine law, these agencies are responsible for monitoring government abuses, recommending state action in line with international rights norms, and implementing rights programs. The Commission on Human Rights was established following enactment of the 1987 Constitution as a bulwark against the sorts of civil rights abuses perpetrated by state actors during the Marcos era. The Council for the Welfare of Children was created under the Child and Youth Welfare Code of 1974 and was expanded after the return to democracy in 1986. The Juvenile Justice and Welfare Council was established after passage of the 2006 Juvenile Justice and Welfare Act (RA 9344).

Of these two sets of actors (oligarchic elites and right groups), the first has had dominant influence on state actions vis-à-vis civil rights since independence, reflecting its wider political dominance.Footnote68 However, as noted earlier, the downfall of the Marcos regime led to greater opportunities for rights groups to organize, mobilize, and participate in policymaking, both in general and specifically in relation to civil rights.Footnote69 Congress, while being the most apparent representation of oligarchic elite power, has provided mechanisms for these elements to contest elite agendas. The introduction of the party-list system in the 1987 Constitution and its implementation by the Party-List Systems Act of 1995 has allowed representatives from subaltern communities to win seats in Congress. Both the National Democratic Left and the Social Democratic Left have engaged in electoral politics since 1998, which was the first election with party-list representation. They have used their seats in the House to push for rights-friendly legislation and launch legislative inquiries into civil rights abuses. The presence of these representatives has given rights groups a degree of instrumental influence in Congress and have helped them to forge alliances to block legislation antithetical to civil rights and to keep state forces in check. Similarly, the Commission on Human Rights, which is the Philippines’ national human rights institution, frequently collaborates with NGOs and other rights organizations to monitor, report on, and recommend legal action against rights abuses, while also raising international attention on such issues. The media also provides space for rights groups to contest civil rights abuses. During the Duterte administration, journalists reported crucial information on the drug war that rights groups used to monitor and track extra-judicial killings. In short, while rights groups and their allies have occupied a subordinate position in the country’s power structure, and consequently have had relatively little influence over state action vis-à-vis human rights, they have nevertheless been able to promote civil rights causes to at least some extent in the post-Marcos era by exploiting new spaces made available by democratic reforms.

Lowering the minimum age of criminal responsibility

The Philippine government became a state party to the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child in 1991. In so doing, it committed to establishing “a minimum age below which children shall be presumed not to have the capacity to infringe the penal law.”Footnote70 Yet in ensuing years various administrations moved slowly to pass legislation specifying a minimum age of criminal responsibility, and even took harsh actions antithetical to children's rights. For instance, successive administrations prosecuted children and put them on death row to appear tough on crime.Footnote71 This situation prompted the creation of the Philippine Action for Youth Offenders and Child Rights Network, which launched a sustained campaign for a fairer juvenile justice system during the 2000s that attracted support from key elite politicians in Congress, sections of big business, as well as then-President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo.Footnote72 The result was the passage in 2006 of RA 9344. This law established the minimum age of criminal responsibility at fifteen years, in line with international standards. Opposition to this threshold emerged almost immediately, particularly from legislators who cultivated an image of being tough on crime.Footnote73 Yet in the face of support for the legislation from a solid coalition of rights groups and key elites, opponents made no headway. Child rights organizations secured the support of sufficient legislators in Congress to block proposals to lower the minimum age of criminal responsibility.Footnote74

During the Duterte administration, the contest over the minimum age of criminal responsibility entered a new phase. Upon assuming office in June 2016, Duterte declared that he would lower the minimum age as part of his anti-drug war because, he claimed, children were involved in drug crimes.Footnote75 In November 2016, House Speaker Pantaleon Alvarez, whom Duterte had hand-picked for the speaker role, filed a bill stipulating that the minimum age of criminal responsibility would be lowered to nine years.Footnote76 By May 2017, Duterte’s allies in the House had filed five further bills seeking to lower the age.Footnote77 In 2019, Duterte again raised the issue of the minimum age of criminal responsibility, this time stating that he was “comfortable” with reducing it to twelve years.Footnote78 On January 21, 2019, the House Committee on Justice approved a separate bill, consolidating the six earlier bills proposed by Duterte allies, with a proposed minimum age of criminal responsibility of twelve years.Footnote79 The bill was railroaded through the House of Representatives and was approved barely a week later.Footnote80 This meant that only Senate approval was required before Duterte could sign the bill into law. However, despite the overwhelming support Duterte had in Congress – as noted earlier, he held a supermajority in both houses – his administration ultimately failed to gather enough support in the Senate to pass the bill and send it to the Duterte. This was due to sustained pushback from a unified coalition of rights groups and sections of the oligarchic elite. The bill ultimately got stuck at the committee level and did not reach the Senate floor for a vote. The conclusion of the 17th Congress (2016-2019) with the May 2019 midterm elections meant the bill would have to be refiled to proceed through the Senate. Ultimately, this did not happen as the government had to focus its attention on the COVID-19 pandemic.

Why did this legislation fail? In response to the moves by Duterte and his allies, the Child Rights Network and its member organizations launched a campaign they called “Children Not Criminals.” This campaign sought to reach a broad audience and involved dissemination of messages and images through social media, production of documentaries on children in conflict with the law, the organization of a Change.org petition, nationwide workshops, and lobbying activities, and peaceful protests in both chambers of Congress. At the center of this campaign was an image () of a young child referred to as bunso (young sibling). The network allowed any individual or organization to use the photo in their social media accounts, leading to wide circulation of the image on social media.Footnote81 The campaign’s Change.org petition secured 91,435 signatures.Footnote82 The Child Rights Network drew on the support of its member organizations and their respective networks, both of which had grown significantly since the Child Rights Network’s establishment in 2006. At formation, CRN had ten members. As an indication of its growth, it had sixty-two members from across the Philippines in October 2022. It also successfully reached out to a wider group of individuals and organizations for support. By January 2019, some 343 people’s organizations, NGOs, universities, clubs, political parties, local government units, legislators, experts, and celebrities had publicly endorsed the Children Not Criminals campaign in the Philippine Daily Inquirer, one of the country’s major daily newspapers.Footnote83 While not a particularly large number compared to the country’s population, the coalition of supporters covered diverse geographies, and reflected a wide array of interests that has rarely come together. The campaign also drew broad support from subaltern elements, rights-oriented NGOs, the Catholic Church, leftists, and bureaucrats from sympathetic state agencies such as the Commission on Human Rights, the Council for the Welfare of Children, the Juvenile Justice and Welfare Council, and even the Department of Social Welfare and Development.Footnote84

Figure 1. Bunso image disseminated and promoted on social media platforms by the Child Rights Network. Source: Child Rights Network Philippines.

Importantly, this alliance was not only broad but also united. It remained unified throughout the campaign behind the goal of keeping the minimum age of criminal responsibility at fifteen years instead of being absorbed by internal conflicts, something that has negatively impacted other rights campaigns in the Philippines. This unity reflected the fact that the Child Rights Network had established a framework for engagement and good working relationships with member organizations during the RA9344 campaign.Footnote85 It was also due to the fact that the Child Rights Network was consultative and inclusive in carrying out the campaign, enhancing ownership among its members and other organizations and facilitating engagement with grassroots organizations.Footnote86 For instance, the Child Rights Network added Salinlahi Alliance, a coalition with links to leftist groups working with urban and rural poor communities, to the coalition during the campaign to further broaden their network. This consultative framework is a well-used strategy for child rights organizations in the Philippines, which regularly consult with their stakeholders on issues of legislation and policy.Footnote87 Finally, it was relatively easy for these diverse groups to rally behind support for children and correspondingly hard for Duterte and his allies to demonize them.

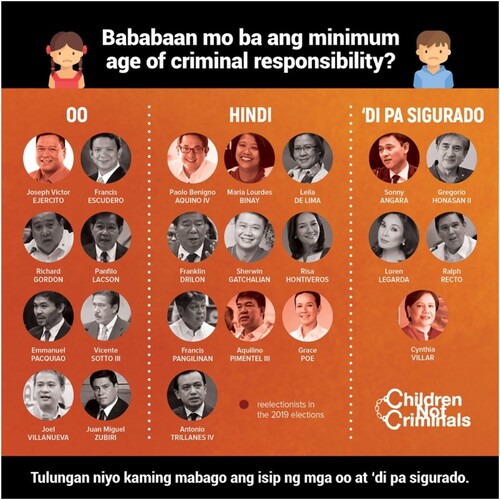

Moreover, rights groups — and the Child Rights Network in particular — successfully garnered support for the Children Not Criminals campaign from key sections of the oligarchic elite. Major business associations like the Makati Business Club and the Philippine Business for Social Progress as well as conglomerates were silent on this issue despite big business’ expressed support for children’s rights.Footnote88 Yet the Child Rights Network was able to secure support for its campaign from a significant number of Congressional representatives through its campaign and lobbying activities, particularly the behind-the-scenes work of its convenor, the Philippine Legislators’ Committee on Population and Development, a grouping comprising former and current legislators. To expand elite support for the campaign, the Child Rights Network and the Philippine Legislators’ Committee on Population and Development reached out to Congressional representatives utilising moral ideologies – that is, ideologies that “employ a conception of authority that may be grounded in metaphysical, charismatic, and/ or traditional sources” in which “conformity to received codes of behaviour assumes pre-eminence in evaluating the conduct of power holders”Footnote89 – that resonated with them (). For instance, religious faith was a powerful influence on some member organizations of the network that has links with the Catholic Church and the Philippine Action for Youth Offenders, as well as with some Congressional representatives. To capitalize on this connection, some members of the network asked Catholic bishops to lobby their respective congressional representatives to block the bill. The Child Rights Network also sent children to legislators’ offices to lobby against the bill and hand out flowers. It also asked legislators’ (primarily female) spouses to lobby their husbands/partners. In an interview, former Commission on Human Rights Commissioner and Philippine Action for Youth Offenders founding member Karen Gomez-Dumpit explained, “with children, it’s easier. It’s natural that parental instincts kick in when it comes to children.”Footnote90 In addition to exploiting religious and parental sympathy, the Child Rights Network also appealed to Congressional representatives’ electoral interests. It presented members of the House of Representatives with data on children in conflict with the law in their respective legislative districts, highlighting the potential use of the issue against legislators’ re-election efforts. For instance, it noted that putting more children in conflict with the law in jail could strain the resources of local governments and generate push back from parents and concerned community members.Footnote91 In the Senate, it employed a similar approach, but with a focus on the national landscape. Because senators are elected nationally in the Philippines, they are more susceptible to public pressure, as well as scrutiny from members of the national media and civil society groups. The network also published and circulated materials such as documentaries, photos, and graphics, both in print outlets and on social media, alongside visual depictions of children in conflict with the law. Finally, the Child Rights Network harnessed support from various government agencies. The Commission on Human Rights, the Committee for the Welfare of Children, and the Juvenile Justice and Welfare Council all provided expertise and credibility by participating as experts at committee hearings and publishing statements in support of the campaign.

Figure 2. This image, posted on Facebook on January 31, 219, shows the positions of senators on lowering the minimum age of criminal responsibility. The question asks, “Do you want to lower the minimum age of criminal responsibility?” Positions are identified as: oo (yes), hindi (no), or ‘di pa sigurado (unsure). Source: Child Rights Network Philippines.

These efforts were not sufficient enough to prevent the House Committee on Justice from passing the consolidated bill in January 2019 but, combined with strong public opinion in favor of maintaining the minimum age of criminal responsibility at fifteen years, the campaign did shift opinion in the Senate. In January 2019, a Social Weather Station poll of 1,500 respondents commissioned by the Commission on Human Rights found that a majority of respondents supported maintaining the median minimum age of criminal responsibility at fifteen years.Footnote92 In the face of elite division and strong popular sentiment in favor of not changing the age, senators ultimately baulked at putting the bill to a vote in the floor, apparently concerned that it could potentially impact forthcoming midterm elections in May 2019. In an interview, campaign chair Melanie Llana said sympathetic senators helped convince other senators to not support the bill.

In sum, the Child Rights Network successfully blocked the lowering of the minimum age of criminal responsibility because it forged a strong coalition of rights groups and important sections of the oligarchic elite. With a coherent movement, public support, and significant elite support, especially in Congress, the bill failed to become law. When the administration’s attention shifted to the government’s COVID-19 pandemic response in 2020, efforts to lower the minimum age were abandoned.

Extra-judicial killings during the War on Drugs

Violations of Philippine citizens’ basic civil rights have long been a prominent feature of political and social life in the country, going back at least as far as the colonial period.Footnote93 These have included the murder of political opponents, peasants, workers, and rights activists, often associated with land conflicts.Footnote94 During the Duterte presidency, extra-judicial killings became associated with the war on drugs. As noted earlier, this included the murder of large numbers of suspected drug users and drug traffickers, mostly by police and vigilante groups and often at the instigation of Duterte and other senior officials.Footnote95 Rights groups have estimated that at least 27,000 people were killedFootnote96 while the Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency has put the number at 6,248.Footnote97 Regardless of the precise number, rights groups have argued that these killings were crimes against humanity and called for prosecution of perpetrators and those who incited them, such as Duterte.Footnote98 Yet, for the most part, no government officials so far have been held to account, with the exception of a few police officers.Footnote99 The war on drugs also attracted popular support. Despite the number of extra-judicial killings, opinion polls by the Social Weather Station in September 2019 found that eighty-two percent of respondents were satisfied with the drug war and seventy-eight percent were satisfied with Duterte.Footnote100 While Duterte’s approval ratings dipped into the low fifties during the 2020 COVID pandemic, the final Social Weather Station survey during his term, conducted from June 26 to 29, 2022, showed that eighty-one percent of Filipinos were satisfied with Duteret’s performance during his six years in office.Footnote101

The extra-judicial killings attracted condemnation from domestic and international human rights organizations, foreign governments, leftist organizations, groups representing victims of the war on drugs and their families, and many other groups.Footnote102 Opponents held protests demanding accountability from Duterte and other senior officials and action on the part of other sections of the government. They also engaged in legal mobilization – that is, the act of mobilizing laws to claim justice for civil rights violations via strategic litigation and other activities – seeking justice for victims and their families.Footnote103 The latter included administrative cases filed with the Ombudsman and the Philippine National Police’s Internal Affairs Service to prosecute erring police officers,Footnote104 criminal cases in regional courts, and petitions to the country’s Supreme Court to stop the drug war on constitutional grounds.Footnote105 However, in contrast to the minimum age of criminal responsibility case, the Duterte administration did not back down in the face of these moves for two reasons.

First, rights groups did not present a united front on the war on drugs, compromising their ability to mobilize politically and legally to contest it. This was in part because these groups had different strategies for responding to extra-judicial killings and in part because their efforts became intertwined with intra-elite rivalries. An illustrative example of the former is how two people’s organizations, both of which were focused on rehabilitating survivors of the war on drugs, engaged with their stakeholders. One [Organization A] took an activist approach, conducting political education, raising awareness of socio-economic issues, and encouraging survivors to join protests and file cases. The other [Organization B] focused solely on addressing survivors’ psycho-spiritual needs. While Organization A was focused on mobilizing survivors to engage in protests, Organization B started providing livelihood opportunities and education plans to survivors. In 2022, tensions heightened because members of Organization A started engaging with Organization B to get livelihood support and education plans. Organization B actively discouraged survivors from engaging in political mobilizations as a condition of joining, resulting in departures from Organization A. Representatives of both these organizations claimed the other side was trying to tarnish its reputation with survivors by attacking the character of the organizers and their strategies. For instance, members of Organization A criticized Organization B for being too passive in its approach, while Organization B critiqued Organization A for using the mothers of victims to push a leftist political agenda. This conflict was resolved when survivors were asked to choose only one organization to engage with.

An illustrative example of how efforts to contest the war on drugs became intertwined with intra-elite rivalries is the case against Duterte that was filed with the International Criminal Court. The first complaint against Duterte was filed on April 24, 2017 by a lawyer named Jude Sabio for alleged mass murder in the war on drugs.Footnote106 Behind the scenes, this effort was supported by figures associated with the pro-military, right-wing Magdalo Party, then-Senator Antonio Trillanes IV and then-House of Representatives member Gary Alejano. The latter two filed supplemental complaints at the International Criminal Court in June 2017.Footnote107 Trillanes is a fierce Duterte critique who was part of the Senate minority at the time. In an interview, Trillanes stated that he tried to persuade the Commission on Human Rights to file a case at the International Criminal Court in the first year of Duterte’s term.Footnote108 The response, he said, was that he should wait for a better political climate before he filed a case. Trillanes alleged that members of the opposition Liberal Party were behind this advice, as they feared that an International Criminal Court case would lead to the impeachment of then- Vice President Leni Robredo, the chairperson of Liberal Party, as retaliation by Duterte and his allies. In the end, Trillanes and Alejano decided to bypass the Commission on Human Rights due to the latter’s political stance.Footnote109

Without a common strategy and faced with internal conflicts, rights groups focused on running their own programs and engagements with survivors. There were pockets of solidarity, with coalitions being established within specific regions. For instance, activists in the Negros region created the Human Rights Alliance of Negros and the North Negros Alliance for Human Rights Advocates to address issues ranging from extra-judicial killings to environmental concerns. Similarly, the Catholic Church mobilized its Social Action Centers, non-profit organizations headquartered in each Catholic diocese, to carry out peaceful protests, assist extra-judicial killing survivors, and call for accountability in relation to the killings. The Archdiocese of Jaro's Social Action Center coordinated with all parishes in the diocese to launch protest caravans in Iloilo and Guimaras against extra-judicial killings and the revival of capital punishment. But, in general, such collaboration was rare.

This inability to present a united front reflected the fact that there were no pre-established umbrella groups like the Child Rights Network or frameworks on how to respond to extra-judicial killings. While groups like Karapatan had a nationwide network of rights defenders before Duterte, other groups mostly worked with allies within the national and social democratic left and the media but were unable to expand partnerships with politically nonaligned NGOs. The necessary financial and human resource arrangements were also not in place. Even the Commission on Human Rights, notwithstanding its possibly compromised position on the International Criminal Court case, had provided crucial support to rights groups but lacked the necessary manpower and resources to deal with the initial onslaught.Footnote110 As former Commission on Human Rights Executive Director Jacqueline De Guia noted in an interview, “Everyone was overwhelmed. Nobody saw it coming. The system was unprepared for it.”Footnote111 The commission relied on funding from the European Union and the Spanish Agency for International Development Cooperation to run their GoJust project, a measure which aimed to strengthen the agency’s institutional mechanisms and fund civil society collaborations.Footnote112

Moreover, rights groups were unable to gain significant support from oligarchic elites, despite employing a range of strategies for this purpose. These included religious organizations and leftist representatives in the House of Representatives who tried to persuade other congressional members to oppose Duterte’s war on drugs, as well as NGOs that named and shamed pro-drug war politicians. Yet, for the most part, rights groups encountered an unreceptive audience within Congress. Early in the war on drugs, Duterte began to intimidate politicians, members of the judiciary, and business elites, resulting in their disengagement from the issue. A key moment was the jailing of Senator Leila de Lima in February 2017 after she led hearings into extra-judicial killings in Davao, where Duterte had been mayor prior to becoming president.Footnote113 Another was the creation and dissemination by the Duterte administration of lists of alleged “narco-politicians.”Footnote114 Ahead of the 2019 senatorial elections, Duterte read out on live television the names of thirty-three mayors, eight vice-mayors, three congressmen, one board member, and one former mayor, all of whom he labelled narco-politicians.Footnote115 By the end of his administration, twenty-seven mayors and vice-mayors who were on such lists had been killed in police operations or by assassins.Footnote116 A third moment was the removal in May 2018 of Supreme Court Chief Justice Maria Lourdes Sereno. Sereno had opposed Duterte in controversial cases like his declaration of Martial Law in Mindanao in May 2017 in response to the Marawi City siege and the heroes’ burial he gave to the former dictator, Ferdinand Marcos. She also had publicly criticized the war on drugs.Footnote117 While instigated by the Supreme Court’s associate justices, her removal is believed to have been linked to her opposition to Duterte, given the repeated threats he made against Sereno and impeachment proceedings begun by Duterte’s allies in Congress.Footnote118 Finally, Duterte launched a series of “law-fare” attacks (cases related to legal or regulatory breaches) on elite business families, particularly those that owned major media companies, as a warning to big business interests to not interfere with his political agenda, including the war on drugs.Footnote119

In the face of such intimidation and the popularity of the war on drugs among the public, the oligarchic elite for the most part chose not to contest Duterte on this issue. According to former Senator Trillanes, de Lima’s arrest had a chilling effect on other senators, claiming, “when he was successful in putting her away, the whole senate was virtually co-opted … nobody dared to question Duterte anymore because you can end up like de Lima.”Footnote120 Indeed, De Lima’s arrest led to “mass defections to Duterte’s legislative coalition.”Footnote121 Carlos Zarate, a former House of Representatives member from the progressive BayanMuna party, believed the drug lists had a similar effect:

Especially for politicians who have skeletons in their closets, at one time or another, the chilling effect was great … … [I]f you’re named, and you’re a politician, you’re done … … That is the zeitgeist [of] the last six years: people were afraid.Footnote122

Rights groups also failed to swing public perceptions of the war on drugs and Duterte their way. As noted earlier, there were high levels of public satisfaction with both Duterte and his anti-drug campaign throughout his term in office. This relatively high level of public support compared to lowering the minimum age of criminal responsibility was due in part because drug war victims and illegal drug users attracted little public sympathy, in contrast to the children affected by the minimum age of criminal responsibility issue.Footnote126

In sum, the extra-judicial killings in the war on drugs continued unabated throughout the Duterte presidency because rights groups were unable to build a unified alliance that could rally public or elite support. The lack of collaboration between rights groups in response to the war on drugs, under-resourcing and weak preparation, and differences in strategy between rights groups inhibited the creation of a nationwide alliance like that forged by the Child Rights Network in relation to minimum age of criminal responsibility issue. Rights groups were also unable to gain elite support due to elite acquiescence in the face of Duterte’s intimidation of political opponents, the judiciary, business owners, and the media. Finally, the fact that drug users and traffickers attracted little public sympathy made it difficult for rights groups to garner popular support for their position. Unchallenged by a strong opposing coalition, the drug war remained popular throughout Duterte’s rule.

Conclusion

We have sought to explain why the Duterte administration’s approach to civil rights varied by issue, notwithstanding its overall hostile stance vis-à-vis these rights. Whereas most analyses of the politics of civil rights in the Philippines under Duterte have explained the Duterte government’s approach to civil rights in terms of his populist political strategy, we emphasize the mediating role of rights groups and factions of the oligarchic elite. Rather than being driven solely by his populist political strategy, the Duterte administration’s decisions with regards to civil rights issues were also shaped by the extent of pushback against, support for, and disengagement on the part of rights groups and the oligarchic elite. More specifically, we argue that outcomes varied according to the extent of unity among rights groups, and the extent of support for by oligarchic elites. To support this analysis, we have focused on two cases, lowering the minimum age of criminal responsibility and extra-judicial killings in the war on drugs. In the first case, Child Rights Network and its allies successfully blocked the lowering of the fifteen-year threshold because they were supported by public opinion, were able to build a unified alliance among rights groups, and had the support of some oligarchic elites. By contrast, in Duterte’s war on drugs, rights groups failed to have a similar impact because of internal divisions borne of competing strategies and interests, a limited history of collective action, and an unwillingness on the part of oligarchic elites — whether in Congress, the judiciary, or the business sector — to stand up to intimidation by Duterte and his allies and contradict public opinion.

Our argument has both conceptual and practical implications. Conceptually, it suggests that analysis of the politics of civil rights during the Duterte period need to go beyond a concern with the effects of Duterte’s political strategy to consider how these effects were mediated by coalitional politics. Frameworks for understanding Philippine politics have in general been elite-centred,Footnote127 a pattern that continued during the Duterte period. Our argument reinforces the need for a more bottom-up perspective while, at the same time, suggesting that this needs to do more than consider the effects of non-liberal values within societyFootnote128 or the role of “populist publics.”Footnote129 Central consideration should be given to the concrete actions taken by rights groups to contest civil rights abuses and how these intersected with oligarchic interests. Further research in this vein will help shed clearer light on the conditions under which the Duterte administration adopted or was forced to adopt rights-friendly or unfriendly policies. This will help in understanding the politics of civil rights in the Philippines more broadly to the extent that populist rule has been a feature of earlier periods of the Philippines’ political history and may be a feature of future periods in its history.

In practical terms, our argument implies a two-pronged approach to combating civil rights abuses in the Philippines. The literature on Philippine politics under Duterte discussed earlier has little to say on how civil rights abuses in the Philippines should be combated. Yet, in emphasizing the effects of Duterte’s populist political strategy, this suggests that the best approach is to prevent the emergence of populist leaders in the first place, by mobilizing support behind more progressive or liberal candidates and challenging populist ideas that resonate with the wider public.Footnote130 Our analysis suggests that we need to not only take such steps but go further in case populist leaders are elected. More specifically, we need to focus on building unified and broad alliances among rights groups and enhancing their alliances with oligarchic elites. The minimum age for criminal responsibility case shows that there is potential to build wide-ranging support among rights groups when lead organizations give allies ownership of rights campaigns, communicate their goals effectively, and consolidate alliances over an extended period. This in turn indicates a need for rights groups to secure sustainable funding beyond project-based grants so they can sustain monitoring of and engagements with civil rights issues and are ready to act when opportunities or needs arise. With regards to the connections between rights groups and oligarchic elites, our analysis points to the important role that progressive legislators such as those in the Philippine Legislators’ Committee on Population and Development can have. Cultivating this and other comparable organizations, while avoiding capture, will contribute to ensuring that civil rights concerns in the Philippines have a broad base of support that includes elements directly engaged in policymaking.

Acknowledgements

Our thanks for research support from the University of Melbourne’s Melbourne Research Scholarship and the Fox Fellowship at Yale University.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

David Lozada

David Lozada is a doctoral candidate at the Asia Institute of the University of Melbourne, and a 2023-2024 Fox International Fellow at Yale University.

Andrew Rosser

Andrew Rosser is Professor of Southeast Asian Studies at the University of Melbourne.

Notes

1 Commission on Human Rights Citation2022; Karapatan Citation2023.

2 Coronel Citation2017; Evangelista Citation2023.

3 Lozada Citation2023.

4 “Red-tagging” in the Philippines is labelling someone a communist or communist sympathizer.

5 Karapatan Citation2023.

6 Karapatan Citation2023.

7 Parrocha Citation2022.

8 CNN Philippines Citation2022.

9 Sevillano 2022.

10 United Nations Human Rights Council Citation2023.

11 Not all parts of this strategy were popular. The push to lower the minimum age of criminal responsibility, for instance, lacked popular support from the beginning.

12 Dulay, Hicken, and Holmes Citation2022.

13 Hamlin Citation2023.

14 Fredman Citation2018, 62.

15 Fredman Citation2018.

16 Cf. Curato Citation2017; Casiple Citation2016; Kenny Citation2019; Heydarian Citation2018.

17 Heydarian Citation2018, 32.

18 Heydarian Citation2018, 9.

19 Heydarian Citation2018,150.

20 Kenny Citation2019,121.

21 Curato Citation2017, 150.

22 Berehulak Citation2016.

23 Coronel Citation2017.

24 Evangelista Citation2023.

25 Ramos Citation2020, 500.

26 Pernia Citation2019.

27 Curato Citation2019, 117.

28 Webb Citation2017, 98.

29 Quimpo Citation2008.

30 Casiple Citation2016; Heydarian Citation2018.

31 Cf. Oh Citation2016; Regilme, Citation2016.

32 Ramos Citation2020.

33 This section and those below draw on fieldwork conducted by the first author in Metro Manila, Iloilo, and Bacolod from July to December 2022. He carried out thirty-five interviews with civil society actors, religious leaders, human rights defenders, journalists, family members of extrajudicial killings (EJK) victims, government officials, and politicians regarding these two issues. He also conducted participant observation of actors involved in mobilizing against EJKs. These sections also draw on reviews by both authors of human rights reports, NGO programs, government resolutions, religious documents, and news reports. Fieldwork was approved by the University of Melbourne’s Office of Research Ethics and Integrity valid from July 2022 to July 2024.

34 Anderson Citation1988; Hutchcroft Citation1998.

35 Sidel Citation1999; Tadem and Tadem Citation2016.

36 Bello Citation2017a.

37 Raquiza Citation2014.

38 McCoy Citation1994.

39 Sidel Citation1999, 9.

40 Tadem and Tadem Citation2016.

41 Sidel 2004:3.

42 Regilme Citation2016, 223.

43 Sidel Citation1999.

44 Rodan Citation2021; Tadem and Tadem Citation2016.

45 Bello Citation2017b, 31.

46 Cabacungan Citation2016.

47 Cabacungan Citation2016; Pasion Citation2016.

48 Viray Citation2017.

49 Coronel Citation2019, 214.

50 Alston Citation2008, 15.

51 Global Witness Citation2019.

52 Oh Citation2016, 198.

53 Lozada, Citationforthcoming.

54 UNICEF Citation2017; Save the Children nd.

55 Online interview with a former CHR Commissioner, December 20, 2023.

56 Alston Citation2008; Global Witness Citation2019.

57 Lamchek & Sanchez Citation2021.

58 Asian Development Bank Citation2007, 3.

59 Hutchison & Wilson 2016.

60 Clarke Citation2012.

61 Asian Development Bank Citation2007; Clarke Citation2012.

62 The CPP has a paradoxical record on rights in that while it mobilizes against government rights abuses, the New People’s Army is known to have carried out abuses of its own (Alston Citation2008).

63 A split within the Communist Party in the 1990s between those who supported and those who rejected its doctrine led to the creation of the Social Democratic Left and political parties like the Philippine Democratic Socialist Party and Akbayan. Akbayan, for instance, participates in elections, strives to have grassroots members, and presents concrete development alternatives while foregoing the idea of a revolution (Quimpo Citation2008). In Congress, Akbayan has consistently authored and supported progressive legislation that promotes rights, most notably the Responsible Parenthood and Reproductive Health Law.

64 Miller Citation2021.

65 Hedman Citation2006, 33.

66 Leviste Citation2016, 38.

67 Leviste Citation2016, 38.

68 Clarke Citation2012; Lorch Citation2021.

69 Quimpo Citation2008.

70 Article 40-3a.

71 Amnesty International Citation2003 and interview with a former CHR Commissioner, Quezon City, Philippines, October 6, 2022.

72 Interview with CHR-Child Rights Center representative, Quezon City, Philippines, October 20, 2022. See also Jimenez-David Citation2005 and Manila Standard Citation2006.

73 Philippine Action for Youth Offenders Citation2008; Save the Children Philippines Citation2007.

74 Online interview with Children Not Criminals campaigner, November 4, 2022, and with CHR-Child Rights Center representative, Quezon City, Philippines, October 20, 2022. See also Villanueva Citation2014.

75 Agence France-Presse Citation2016.

76 Philippine Daily Inquirer Citation2016.

77 Cruz Citation2017.

78 CNN Philippines Citation2019.

79 House of Representatives Public Affairs 2019.

80 Sunstar Citation2019.

81 Online interview with Child Rights Network campaigner, November 5, 2022. The original Facebook post can be seen here: https://m.facebook.com/childrennotcriminals/photos/a.1317969091557342/1335200993167485

82 See: www.change.org/p/no-to-lowering-the-minimum-age-of-criminal-responsibility-in-the-philippines.

83 See the following Facebook post: https://www.facebook.com/salinlahiphilippines/photos/a.1497924023803305/2569395749989455/

84 Tomacruz Citation2018.

85 Interview with CHR-Child Rights Center representative, Quezon City, Philippines, October 20, 2022. See also Estorninos Citation2017.

86 Online interview with a Children Not Criminals campaigner, November 4, 2022.

87 Civil Society Coalition on the Rights of the Child Citation2020.

88 UNICEF Citation2017.

89 Rodan and Hughes Citation2014, 12.

90 Interview with former CHR Commissioner, Quezon City, Philippines, October 6, 2022. Similar views were expressed in interviews with an anonymous Children Not Criminals campaigner, November 4, 2022, and a CHR-Child Rights Center representative, Quezon City, Philippines, October 20, 2022.

91 Online interview with a former Congress representative, December 15, 2022.

92 Gavilan Citation2019.

93 Sidel Citation1999.

94 Alston Citation2008; Franco and Borras Citation2007.

95 Commission on Human Rights Citation2022; Evangelista Citation2023.

96 Karapatan Citation2023.

97 Sarao Citation2022a.

98 Regencia Citation2021.

99 Karapatan Citation2023.

100 Cabato Citation2019.

101 Bacelonia Citation2022.s

102 Gatmaytan Citation2018; Lamchek & Sanchez Citation2021

103 Karapatan Citation2023; Lozada, Citation2021

104 Interview with IDEALS Human Rights Program representative, online, 15 December 2022 and National Union of People’s Lawyers NCR representative, Quezon City, Philippines, 14 December 2022.

105 Buan Citation2017.

106 Esmaquel Citation2017.

107 Senate of the Philippines Citation2017.

108 Interview with a former Senator, Quezon City, Philippines, December 13, 2022.

109 Dizon Citation2017.

110 CHR had thinly spread manpower across its sixteen regional offices. Each region only had between six and eight investigators, who had to both investigate alleged killings and do jail visitations for persons deprived of liberty. Interview with a former CHR Executive Director, Quezon City, Philippines, November 24, 2022.

111 Interview with a former CHR Executive Director, Quezon City, Philippines, November 24, 2022.

112 See https://chr.gov.ph/gojusthrp/.

113 Karapatan Citation2023.

114 Symmes Citation2017.

115 Talabong Citation2019.

116 Ropero 2021.

117 Mogato Citation2018

118 Ibarrra Citation2020; Mogato Citation2018.

119 For details, see Lozada Citation2023 and Ranada 2019.

120 Interview with a former Senator, Quezon City, Philippines, December 13, 2022.

121 Parmanand Citation2023,111.

122 Online interview with a former Congress representative, December 15, 2022.

123 Gatmaytan Citation2018. During his six-year term in office, Duterte appointed twenty Supreme Court Justices, thirteen of whom remain on the fifteen-person court.

124 Adams Citation2018.

125 Santos Citation2019.

126 Gideon Lasco and Vincen Yu (2021:5) describe this situation as one of “methamphetamine exceptionalism” and argue that it created “an enabling, or at least permissive, political environment” for extra-judicial killings. See Vasco and Yu 2021, 5.

127 Kerkvliet, 1990; Kerkvliet, 1995; Quimpo, Citation2008.

128 Pernia Citation2019.

129 Curato 2016.

130 Lorch Citation2021; Pernia Citation2019.

References

- Adams, Brad. 2018. “First Conviction of Officers in Philippines ‘Drug War’.” Human Rights Watch, November 29. Accessed December 3, 2023: https://www.hrw.org/news/2018/11/29/first-conviction-officers-philippines-drug-war

- Agence France-Presse. 2016. “Alarm over proposed Philippine law to jail 9-year-olds.” Rappler, November 21.

- Alston, Philip. 2008. “Report of the Special Rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions: Mission to the Philippines.” United Nations Human Rights Council Report. April. Accessed November 14, 2023: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/626743?ln=en

- Amnesty International. 2003. Philippines: Something Hanging Over Me – Child Offenders Under Sentence of Death, Accessed February 28, 2024: https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/asa35/014/2003/en/.

- Anderson, Benedict. 1988. “Cacique Democracy in the Philippines: Origins and Dreams.” New Left Review (169): 3-31.

- Asian Development Bank. 2007. “Overview of NGOs and Civil Society: Philippines.” Asian Development Bank Report. Accessed November 14, 2023: https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/28972/csb-phi.pdf

- Bacelonia, Wilnard. 2022. “Duterte earns ‘excellent’ rating in final SWS survey.” Philippine News Agency, September 24. Accessed February 21, 2024: https://www.pna.gov.ph/articles/1184485

- Bello, Walden. 2017a. “Rodrigo Duterte: A Fascist Original.” In A Duterte Reader: Critical Essays on Rodrigo Duterte’s Early Presidency, edited by Nicole Curato, 77-91. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press.

- Bello, Walden. 2017b. “The Spider Spins His Web: Rodrigo Duterte’s Ascent to Power”. Philippine Sociological Review 65:19-47.

- Berehulak, Daniel. 2016. “‘They Are Slaughtering Us Like Animals’.” New York Times, December 7. Accessed November 14, 2023: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2016/12/07/world/asia/rodrigo-duterte-philippines-drugs-killings.html

- Buan, Lian. 2017. “Lawyers file petition to declare drug war circulars unconstitutional.” Rappler, October 11. Accessed February 20, 2024: https://www.rappler.com/nation/184909-flag-petition-drug-war-circular/

- Cabacungan, G. 2016. “From 3 to 300: PDP-Laban forms ‘supermajority’ in House. Philippine Daily Inquirer, May 26. Accessed February 21, 2024: https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/787547/from-3-to-300-pdp-laban-forms-supermajority-in-house

- Cabato, Regine. 2019. “Thousands dead. Police accused of criminal acts. Yet Duterte’s drug war is wildly popular. Washington Post, October 23. Accessed February 21, 2024: https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/asia_pacific/thousands-dead-police-accused-of-criminal-acts-yet-dutertes-drug-war-is-wildly-popular/2019/10/23/4fdb542a-f494-11e9-b2d2-1f37c9d82dbb_story.html

- Casiple, Ramon. 2016. “The Duterte Presidency as a phenomenon.” Contemporary Southeast Asia 38(2): 179-184.

- Civil Society Coalition on the Rights of the Child. 2020. “Still in the Sidelines: Children’s Rights in the Philippines 2009-2019.” CRC Coalition. https://www.csc-crc.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/CRC-COALITION_FINAL-NGO-ALTERNATIVE-REPORT.pdf

- Clarke, Gerard. 2012. Civil Society in the Philippines: Theoretical, Methodological, and Policy Debates. New York: Routledge.

- CNN Philippines. 2019. “Duterte ‘comfortable’ with minimum age of criminal responsibility at 12.” CNN Philippines, January 24. Accessed November 14, 2023: https://www.cnnphilippines.com/news/2019/01/23/duterte-minimum-age-of-criminal-responsibility.html

- CNN Philippines. 2022. “More rights, protection for foundlings signed into law.” CNN Philippines, May 18, 2022. Accessed November 14, 2023: https://www.cnnphilippines.com/news/2022/5/18/Duterte-Republic-Act-11767.html

- Commission on Human Rights. 2022. “Report on Investigated Killings in Relation to the Anti-Illegal Drug Campaign.” Commission on Human Rights Report. April. Accessed November 2, 2023:https://chr.gov.ph/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/CHR-National-Report-April-2022-Full-Final.pdf

- Coronel, S. 2017. “Murder as Enterprise: Police Profiteering in Duterte’s War on Drugs.” In A Duterte Reader: Critical Essays on Rodrigo Duterte’s Early Presidency, edited by Nicole Curato, 167-198. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press.

- Coronel, Sheila. 2019. “Press Freedom in the Philippines.” In Press Freedom in Contemporary Asia, edited by Tina Burret and Jeffrey Kingston, 214-229. London: Routledge.

- Cruz, M. 2017. “Solon asks Duterte to rethink stand on lower criminal age.” Manila Standard, May 10, 2017. Accessed November 14, 2023: https://manilastandard.net/news/top-stories/236247/solon-asks-duterte-to-rethink-stand-on-lower-criminal-age.html

- Curato, Nicole. 2017. “‘Flirting with Authoritarian Fantasies? Rodrigo Duterte and the New Terms of Philippine Populism.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 47(1), 142-153.

- Curato, Nicole. 2019. Democracy in a time of misery: from spectacular tragedies to deliberative action. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Dizon, Nikko. 2017. “Trillanes, Alejano file complaint at ICC vs Duterte’s drug war.” Philippine Daily Inquirer, June 6, 2017. Accessed December 3, 2023: https://globalnation.inquirer.net/157711/trillanes-alejano-file-complaint-at-icc-vs-dutertes-drug-war

- Dulay, Dean, Hicken, Allan, and Holmes, Ronald. 2022. “The Persistence of Ethnopopulist Support: The Case of Rodrigo Duterte’s Philippines.” Journal of East Asian Studies, 22: 525-553.

- Esmaquel, Paterno. 2017. “Complaint vs Duterte filed before Int’l Criminal Court.” Rappler, April 24. Accessed: February 20, 2024: https://www.rappler.com/nation/167818-complaint-duterte-international-criminal-court/

- Estorninos, Klarise Anne. 2017. “Batang Bata Ka Pa: An Analysis of the Philippine Minimum Age of Criminal Responsibility in Light of International Standards.” Ateneo Law Journal, 62: 259-273.

- Evangelista, Patricia. 2023. Some People Need Killing: A Memoir of Murder in my Country. New York: Penguin Randomhouse.

- Franco, Jennifer and Borras, Saturnino Jr. 2007. “Struggles Over Land Resources in the Philippines.” Peace Review 19 (1): 67-75.

- Fredman, Sara. 2018. Comparative Human Rights Law. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Freedom Mayors. 2022. “The murdered mayors of the Philippines.” Freedom Mayors, December. Accessed January 26, 2023: http://www.citymayors.com/freedom-mayors/philippine-mayors-killed.html#

- Gatmaytan, Dante. 2018. “Duterte, judicial deference, and democratic decay in the Philippines.” Zeitschrift für Politikwissenschaft 28: 553-563.

- Gavilan, Joedesz. 2019. “Majority of Filipinos want 15 as minimum age of criminal liability – SWS survey.” Rappler, January 29. Accessed December 3, 2023: https://www.rappler.com/nation/222124-public-perception-minimum-age-criminal-responsibility-sws-survey-july-december-2018/

- Global Witness. 2019. Defending the Philippines: How Broken Promises are Leaving Land and Environmental Defenders at the Mercy of Business at all Costs. London: Global Witness.

- GMA News. 2017. “Alvarez: No compromise in lowering age of criminal liability.” GMA News, February 2. Accessed February 20, 2024: https://www.gmanetwork.com/news/news/nation/598069/alvarez-no-compromise-in-lowering-age-of-criminal-liability/story/

- Hamlin, Rebecca. 2023. “Civil Rights.” Britannica, December 23, 2023. Accessed January 26, 2024: https://www.britannica.com/topic/civil-rights.

- Hedman, Eva Lotta. 2006. In the Name of Civil Society: From Free Election Movements to People Power in the Philippines. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press.

- Heydarian, Richard. 2018. The Rise of Duterte: A Populist Revolt against Elite Democracy. Singapore: Palgrave Macmilan.

- Hutchcroft, Paul. 1998. Booty Capitalism: The Politics of Banking in the Philippines. Albany: Cornell University Press.

- Hutchison, Jane, and Wilson, Ian. 2020. “Poor People’s Politics in Urban Southeast Asia.” In The Political Economy of Southeast Asia: Politics and Uneven Development under Hyperglobalisation, edited by Toby Carroll, Shahar Hameiri, and Lee Jones, 271-291. Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Ibarra, Edcel John. 2020. “The Philippine Supreme Court under Duterte: Reshaped, Unwilling to Annul, and Unable to Restrain.” Social Science Research Council, November 10. Accessed February 7, 2024: https://items.ssrc.org/democracy-papers/democratic-erosion/the-philippine-supreme-court-under-duterte-reshaped-unwilling-to-annul-and-unable-to-restrain/

- Jimenez-David, Rina. 2005. “A Bill for the Future”, Philippine Daily Inquirer, 8 October. Accessed February 25, 2024.

- Karapatan. 2023. Rodrigo Duterte and his Crass Legacy of Mass Murder and State Terror: Term-End Situation Report on the Human Rights Situation in the Philippines. Karapatan Report, June. Accessed January 25, 2024: https://www.karapatan.org/report/duterte-term-ender-and-2022-marcos-jr-year-end-report/

- Kenny, Paul. 2019. “Populism and the War on Drugs in Southeast Asia.” Brown Journal of World Affairs 25(2):121-136.

- Lamchek, Jayson and Sanchez, Emerson. 2021. “Friends and Foes: Human Rights, the Philippine Left and Duterte, 2016-2017.” Asian Studies Review 45(1): 28-47.

- Lasco, Gideon and Yu, Vincen. 2021. “’Shabu is different’: Extrajudicial killings, death penalty, and ‘methamphetamine exceptionalism’ in the Philippines.” International Journal of Drug Policy 92: 1-7.

- Leviste, Enrique. 2016. “In the Name of the Fathers, In Defense of the Mothers: Hegemony, Resistance and the Catholic Church Engagement in the Philippine Population Policy Process.” Philippine Sociological Review 64: 5-46.

- Lorch, Jasmine. 2021. “Elite capture, civil society and democratic backsliding in Bangladesh, Thailand, and the Philippines.” Democratization 28(1): 81-102.

- Lozada, David. 2021. “How Duterte’s ‘war on drugs’ is being significantly opposed within the Philippines.” Melbourne Asia Review 7.