ABSTRACT

Scholars have long been preoccupied with the role that capital plays in Indonesia’s democratic institutions. Observers emphasize a tight overlap between the worlds of politics and business, with many describing murky connections and corrupt alliances among state officials, oligarchs, and local bosses. While such relations remain fundamental to Indonesian politics, this paper draws attention to a parallel but under-analyzed transformation of both the social and political status of business actors in contemporary Indonesia. From tech entrepreneurs to mining giants, people with established business careers are increasingly taking up the reins of government. Once considered the inferior political and policy actor during Suharto’s New Order, businesspersons now exercise direct political power and entrepreneurial success is valued, even revered, within political and policymaking circles. While evidence of such changes can be identified at different moments in Indonesia’s recent history, during the presidency of businessperson politician, Joko Widodo, there has been a marked intensification of these trends. Today there is a far broader acceptance of business elites as stewards of state institutions. The result is a fusing of private power and public office in a form, and to a degree, that is unprecedented in Indonesia’s political history.

Introduction

There have long been porous borders between the worlds of government and private business in Indonesia. An influential body of political economy scholarship on post-New Order Indonesia characterises the Indonesian state as captured by oligarchs and predatory private interests.Footnote1 In this paper, I argue that developments over the past decade during the administration of businessperson-cum-politician, President Joko Widodo (Jokowi), amount to a political transformation that goes beyond capture. Under Jokowi, businesspeople have come to inhabit a wide range of political positions, and their increasing stewardship of state institutions is now cast as both legitimate and desirable. This new symbiosis of public and private power is reshaping how and for whom the state works.

I begin by demonstrating a transformation in the occupational class backgrounds of Indonesia’s political leadership. Business actors now dominate the executive and parliamentary branches of government, as well as political parties, campaign teams, and in some cases the “special staff” of ministers.Footnote2 This degree of business presence inside government is exceptional in the context of Indonesian history.

A rich literature on electoral clientelism in Indonesia helps, in part, to explain this trend, especially within national and regional legislatures.Footnote3 The rising cost of politics motivates party elites to invite wealthy outsiders into their ranks to help cover election bills, and as the costs of politics increase, people with other occupational profiles have become less and less likely to run for parliament or to win seats if they do. A seat in parliament also offers direct access to the executive branch, making a political career attractive to certain types of actors whose businesses depend on state contracts and licenses. When it comes to the executive, though, I emphasize the causal role of the preferences of Jokowi and the business actors he has integrated into his political network and into government. As a former entrepreneur himself, President Jokowi trusts the private sector, and sees both political and economic value in bringing successful businesspeople into government.

I identify a parallel and related trend—the growing valorization of private enterprise in the language and practices of political actors, as well as in the public sphere more generally. This is a remarkable if incremental shift from the New Order period, when businesspeople were often characterized by scholars as lacking the political and cultural legitimacy enjoyed by the bureaucratic class.Footnote4 Today, individual entrepreneurship is celebrated and revered in public and political life. It is not only typical for businesspeople to enter politics, but also for such figures to emphasize their entrepreneurial accomplishments. The bureaucracy is now in many ways overshadowed by businesspeople who, especially under President Jokowi, are cast as engineers of innovation, creativity, and economic success.

The effect is that a business logic now motivates the design and execution of state development programs. To illustrate this point, I draw on a growing body of comparative scholarship that shows how the occupational class backgrounds of political elites shape countries’ policy trajectories, with business politicians generally pushing the state down more neoliberal and market-oriented paths. In Indonesia, under the leadership of a growing number of business elites, we find a similar pattern whereby policy priorities are reoriented to reflect corporate approaches, and to better serve the interests of capital. I substantiate this point with reference to a range of interventions, and a brief case study on changes to higher education and health sector policy under the leadership of business politicians.

What does this mean for how we understand politics and governance in contemporary Indonesia? The transformations I outline in this paper have, to be sure, their roots in Indonesia’s recent past. A wave of neoliberal reforms in Indonesia in the late 1990s and early 2000s was motivated by pressure from multi-lateral financial organizations in the wake of the 1998 Asian financial crisis, and from coalitions of liberal-reform minded policymakers in parts of the Indonesian bureaucracy, the business sector, and academia. This period of reform prompted abundant scholarly debate, much of it dominated by economists who suggested that such reforms did not go far enough because they were encumbered by bureaucrats’ deep-seated nationalist preferences and hostility toward neoliberal modes of governance. Scholars concerned with the political dimensions of neoliberal reform argued, in a similar vein, that predatory private interests had captured the benefits of economic and political liberalization, in turn undermining neoliberal success.Footnote5

In one important characterization of Indonesia’s post-authoritarian politics, Edward Aspinall interrogated the impact of neoliberalism on post-New Order political life. Aspinall argued that neoliberal practices and ideas, and in particular an emphasis on economic calculation and accumulation, has blended with persistent practices of clientelism to generate a thoroughly fragmented democratic landscape.Footnote6 He argued that Indonesia’s highly competitive and decentralized democracy has “exacerbated the fragmentary effects of clientelism by opening up the market place of potential patrons and enabling them to compete with one another,” in turn accelerating what he called the atomization of social and political relations in contemporary Indonesia.Footnote7

In this paper I argue that over the past decade, Indonesia has entered a new phase in the penetration of neoliberal ideas and practices into political life, driven by the diffusion of private sector interests throughout the country’s political institutions. Unlike during earlier periods, when external pressures from international financial organizations motivated neoliberal reform in the early post-Suharto years,Footnote8 contemporary politics are being corporatized from within. Political institutions are increasingly composed of business actors, and such actors enjoy far greater social and political legitimacy than in the past. I suggest that similar forces noted by Aspinall now generate a growing homogenization of the country’s political landscape. Institutions at all levels of government increasingly involve a similar cast of business politicians, in turn giving rise to a style of governance that embraces enterprise models, often leading policymakers to take analogous corporate approaches to complex social challenges. President Joko Widodo, himself a businessperson politician, has been at the leading edge of these trends.

The paper is structured as follows. The next section maps the shifting occupational class status and growing personal wealth of Indonesia’s political leadership. I then offer explanations for this transformation. Next, I reflect on a shift in political culture marked by a growing valorization of business success and entrepreneurship in political life and policymaking circles. These three sections rely on a mix of secondary research and primary data, including a database on the profiles of Indonesian ministers dating back to the New Order period, and original interview material with prominent businesspersons and senior politicians, including former and current cabinet ministers.Footnote9 The final section explores how businesspeople govern, and how these trends are reshaping policy trajectories. While a systematic assessment of policy outcomes and net welfare effects is beyond the scope of the current study, I show how the Jokowi era has been associated with an increasingly corporate approach to reform, and a business-oriented set of developmental priorities.

There is, however, an important caveat to the emergent picture of business presence inside government in Indonesia. The trends I identify have so far not been associated with a thorough embrace of free markets or a growing suspicion toward the state among Indonesia’s political class. Instead, the state remains, as it has long been in Indonesia, both a major economic actor and a critical conduit for certain types of business actors to expand their empires and protect their interests. The rise of business politicians in Indonesia is, thus, not leading to a wholesale embrace of market fundamentalism or a shrinking of the state, in the way that analysts have observed in other countries. Rather, the migration of business actors into political institutions is changing the composition of the state, accompanied by a socio-cultural shift whereby businesspeople are now widely viewed as legitimate stewards of political institutions. The result is an unprecedented symbiosis between private power and public office in contemporary Indonesia.

The rise of business politicians

During the past decade or so, business politicians have become an increasingly large subsection of Indonesia’s ruling elite. Analysts have long pointed to oligarchic control over national politics, with all the major political parties established after the democratic transition bankrolled by tycoons, usually to use as vehicles for their presidential ambitions.Footnote10 Beyond party leaders, however, a much broader transformation of the country’s political elite has been taking place. A growing number of political powerholders have backgrounds in the business sector, amounting to a privatization of the political class.

For example, regional leaders such as mayors, district heads, and governors increasingly enter politics after careers in business. The Corruption Eradication Commission (Komisi Pemberantasan Korupsi, KPK) reported that forty-five percent of the candidates in the 2020 regional head elections had prior careers as businesspersons.Footnote11 According to Ward Berenschot and Edward Aspinall, twenty-five percent of candidates in the 2015 regional head elections were businesspersons, and a slightly larger proportion were civil servants.Footnote12 Activists and media reports illustrate similar changes in the composition of the national parliament (Dewan Perwakilan Rakyat, DPR). According to Tempo magazine, forty-five percent of national legislators in the 2019-2024 term were businesspeople; Republika reported that for the previous term (2014-2019), twenty-nine percent of legislators had a business background.Footnote13

A number of scholars have observed the growing representation of private sector actors in post-New Order politics. Edward Aspinall notes an increasing number of “wealthy businesspeople entering on the political stage,”Footnote14 while Sharon Poczter and Thomas Pepinsky suggest that there has been a general rise in the number of politicians with prior private sector careers, as well as a decline of “the military and the state as avenues to political influence.”Footnote15 Meanwhile, a forthcoming study by Ward Berenschot and his colleagues that uses company registration data to match politicians’ names to company directors and board members shows a significant number of parliamentarians and ministers have business linkages.Footnote16 Moreover, the authors show that the proportion of representatives with connections to private firms is high by global standards, and on the increase. Marcus Mietzner, meanwhile, observes that the number of super-wealthy oligarchs in the presidential cabinet, both from within and outside of political parties, has increased gradually and consistently since 2004.Footnote17

This new political role for businesspeople is also illustrated by a trend whereby outsider tycoons are invited to lead political campaign teams, despite a lack of formal political experience. Jokowi made Erick Thohir head of his re-election team in 2019. Erick and his brother, Garibaldi “Boy” Thohir, have sprawling business interests in media, mining, and tech. In 2023, Megawati Soekarnoputri, chair of the Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (Partai Demokrasi Indonesia-Perjuangan, PDI-P), appointed Arjsad Rasjid, chair of the Indonesian Chamber of Commerce (Kamar Dagang dan Industri, Kadin) and the CEO of Indika, one of Indonesia’s major mining firms, to run the campaign of PDI-P’s presidential candidate, Ganjar Pranowo. The same year, another presidential candidate, Prabowo Subianto and his running mate, Gibran Rakabuming Raka—Jokowi’s eldest son—appointed Rosan Roeslani to run their campaign. Rosan is also a former head of Kadin and a prominent businessperson with investments across a range of sectors, including shares in Erick Thohir’s conglomerate, Mahaka. Meanwhile, Anies Baswedan, a third presidential candidate in 2024, appointed Tom Lembong, an investment banker and entrepreneur, to be his campaign spokesperson. So, while the candidates themselves had mostly non-business backgrounds, each of their teams was run by prominent and wealthy business elites.

In the past, it was party leaders or retired military generals that usually headed up candidates’ national campaign teams. Seven of former President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono’s nine campaign teams in 2009, for example, were led by elites associated with his political party, the Democrat Party (Partai Demokrat, PD), or former miliary generals, and the chief of his campaign was Hatta Rajasa, chairperson of the National Mandate Party (Partai Amanat National, PAN).Footnote18 In the same year, another presidential candidate, Jusuf Kalla, chose Fahmi Idris, a long-standing member of Golkar, to head his campaign, while Megawati appointed Theo Syafii, a retired military general, to run her campaign. In 2014, Jokowi and Jusuf Kalla’s team was led by high profile PDI-P cadre Tjahjo Kumolo, while Prabowo and Hatta Rajasa’s team was led by a former judge and academic, Mohammad Mahfud Mahmodin. It is certainly the case that politicians like Jusuf Kalla and Hatta Rajasa are also businesspersons, and some party elites that ran campaign teams in the past (including Fahmi Idris) had major business investments. But the recent trend of inviting outsider tycoons with no formal political experience or party membership to direct major campaigns suggests a new phase in the degree to which big business elites engage in national politics. Rather than donate to or support presidential candidates behind the scenes, tycoons are now more likely to participate directly in politics.

Beyond elections and legislatures, the privatization of Indonesia’s political bodies is arguably most dramatic at the executive level. My analysis of the 596 ministerial appointees from 1968 to 2023 (239 during the New Order and 357 since 1999) provides a detailed illustration of this trend. These data show a significant shift in the occupational class of the country’s cabinet ministers, with the number of businesspeople recruited into government increasing over time, most dramatically during Jokowi’s presidency. During the New Order period, cabinet ministers were almost always drawn from the military or bureaucracy, along with some technocrats brought in from the university sector to manage economic portfolios. It was not until the late 1980s and early 1990s that New Order President Suharto put a handful of businesspersons in his cabinet. These included Siswono Yudo Husodo, Abdul Latief, and Hayono Isman, all of whom were high profile members of the country’s two most prominent business associations, the Indonesian Young Entrepreneurs Association (Himpunan Pengusaha Muda Indonesia, HIPMI) and Kadin. President Suharto appointed Tanri Abeng, who at the time was managing director and CEO of several large international and domestic firms, Mohammad “Bob” Hasan, a tycoon and Suharto crony, and former HIPMI leader Agung Laksono to his 1998 cabinet, just before the New Order collapsed.

To be sure, the generals and bureaucrats who dominated Golkar, Suharto’s electoral vehicle, had a range of business interests, and they used their political positions to line their pockets and divert rents from the state to their families and allies. Suharto’s system of “off-budget funding” encouraged military personnel and bureaucrats to set up their own businesses and partnerships to fill funding gaps and contribute to the patron-client networks upon which their careers depended.Footnote19 There has long been a thin line between public office and private enterprise in Indonesia.

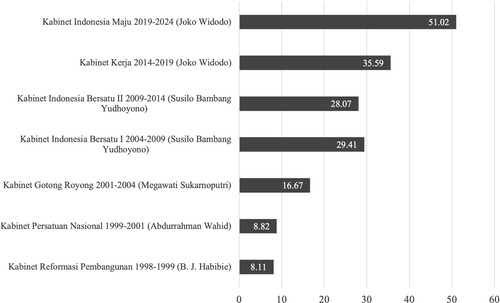

Democratization, however, triggered a dramatic increase in the rate of entry of entrepreneurs into executive government ().Footnote20 The number of appointed ministers with experience in private business (as owners, directors, managers, or commissioners) before entering office has increased steadily since 1998. In the early reform-era cabinets, the proportion of ministerial appointees that had prior business careers peaked at seventeen percent under President Megawati. Under President Yudhoyono the figure hovered at just under thirty percent. In President Jokowi’s second term, fifty-one percent of cabinet appointments went to people with previous career experience in business.

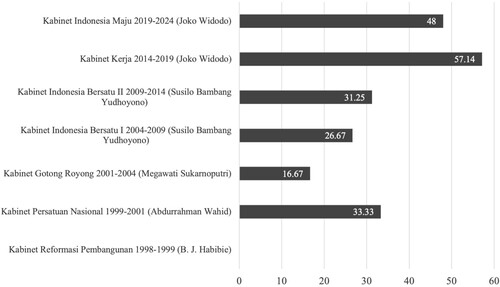

Among these individuals with prior business experience, what proportion are entering government through the party system, and how many are being appointed from outside? By answering these two questions, we can understand if the marked increase in business politicians during Jokowi’s two terms is a function primarily of how political parties themselves are increasingly populated with business elites, of whether the trend is being driven mostly by Jokowi bringing businesspeople into politics via non-party appointments. shows the percentage of business politicians in cabinet that are not formally affiliated with a political party. Jokowi again stands out in comparison to other presidents, with a stronger preference for appointing non-party businesspersons ().

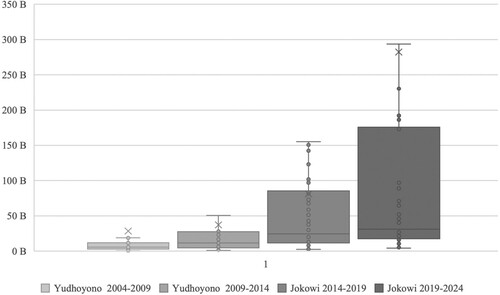

As a growing number of businesspeople have entered the executive cabinet, the average wealth of ministers has, unsurprisingly, soared. uses officially reported wealth data to compare the range and distribution of ministers’ wealth in each cabinet starting from 2004.Footnote21 The data indicate both a steady and incremental rise in the median wealth of ministers, and a dramatic expansion in the upper range of ministers’ wealth during Jokowi’s administration.

Figure 3. Reported wealth of cabinet ministers (billions IDR).Footnote22

The penetration of businesspersons into the state goes further than these figures suggest, because business politicians also employ staff from the private sector. One businessperson-cum-minister explained that it is common for ministers with business backgrounds to, in his words, “bring in people from their companies and private sector networks because they trust them … it’s much easier to work with [them] compared to bureaucrats, who we don’t like having to manage … they [bureaucrats] have other loyalties that means it can be hard to get them to work for you.”Footnote23 Another businessperson minister commented, “I brought just one person in from my company—that’s rare. Others bring in tens or even hundreds.”Footnote24 A former minister with experience in several portfolios and a career in business said that motivating and managing the bureaucracy was their number one headache, and that pulling in their private sector allies was an important strategy for managing bureaucratic challenges.Footnote25

A particularly extreme example of how business politicians establish private sector teams has been the Ministry of Education under the leadership of start-up billionaire Nadiem Makarim. Until Jokowi appointed Nadiem in 2019, the Ministry of Education had never been led by a businessperson, but rather by a practitioner from the education sector, a party member, someone affiliated with one of the major religious organizations (Muhammadiyah or Nadlahtul Ulama), or some combination thereof. The appointment of a tech entrepreneur was thus a significant break with past practices. After taking office, Nadiem contracted a team of around 400 private sector professionals, with over half coming from large technology companies like Gojek (which he founded), Bukalapak, and Grab, as well as people with experience in smaller tech start-ups from Indonesia and the region.Footnote26 The team was designed to mirror—and also bypass—the Education Ministry’s bureaucratic structure and take on the role of designing and executing the ministry’s digital programs, which under Nadiem became the centerpiece of the government’s education sector reforms.Footnote27

The same team established by Nadiem then began working for the Ministry of Health, which was led by a former banker, Budi Gunadi Sadikin, to assist in digital reforms. Sadikin has a very different kind of professional profile than Nadiem. He is not an entrepreneur per se, and instead has decades of experience in the banking sector, including as CEO of the country’s largest bank, Bank Mandiri. Prior to his appointment as Minister of Health, Sadikin had been a special advisor to the Ministry for State-Owned Enterprises during Jokowi’s first term, a role which made him central to managing the nationalization of Freeport McMoran’s gold and copper mines in Papua. Sadikin is only the second health minister in the country’s history to not have a medical degree, and he is the first business politician to lead the country’s health ministry.

In short, a wide range of political institutions at the local and national level are led by business politicians, marking a gradual but dramatic shift in the composition of Indonesia’s ruling elite. In their important 2019 study of electoral clientelism in Indonesia, Aspinall and Berenschot concluded that “political competition has opened up in post-Suharto Indonesia, but it frequently takes the form of competition between bureaucrats.”Footnote28 To the extent that their study attends to the role of businesspersons in politics, the authors cast them as primarily resourceful “allies” of politicians and bureaucrats, rather than political actors in their own right. Today the data suggest a different story. Bureaucratic careers remain common, to be sure. But this pathway into politics, especially at the national level, is overshadowed by private pathways, and by experience in the business world.

Explaining the rise of business politicians

Why has business become such a prominent pathway to politics in contemporary Indonesia? Extant research on rising political costs offers one compelling answer to this question. Studies of vote-buying and clientelism in Indonesia show how the cost of election campaigns has escalated dramatically in recent years, in turn compelling political parties to recruit wealthier candidates and seek relationships with tycoons.Footnote29 One study from 2019, for example, found that a candidate running in a district head election would spend on average about US$2.5 million.Footnote30 Research also shows that under the open-list proportional representation system introduced in 2009, intra-party competition among legislative candidates has generated an explosion in campaign spending and vote-buying.Footnote31 In conversations with candidates running in the 2024 district-level parliamentary elections, they complained about a massive increase in the cost of vote-buying, from around US$6 per vote in 2014 to between US$20 and US$30 per vote in 2024, contributing to what they felt was the most expensive election in the country’s democratic history.

The financial costs of politics do not end once legislative campaigns are over. Some politicians need funds to underwrite the costs of constituency services and to protect their turf from potential rivals. These needs motivate legislators to use their existing or establish new private enterprises as a source of capital. Among incumbent legislators who sit on “wet”Footnote32 parliamentary commissions that provide access to social welfare programs and infrastructure projects that they can direct to their constituents, there is less need for them to draw from their own private savings. But as one business politician in PDI-P (Partai Demokrasi Indonesia Perjuangan) explained, for new candidates and legislators sitting on commissions that provide little access to such projects, they must rely on private finances which gives businesspeople a resource-edge over competitors.Footnote33 The experience of a first-time national legislator from Golkar paints a similar picture:

My husband started a business, and we use that to help fund programs for my constituents. The parliamentarians who have been doing this for many years have by now set up several of their own businesses as a resource, if they didn’t already have businesses before [taking office].Footnote34

The rising cost of politics also helps to explain the appointment of businesspeople to manage political campaigns. Such individuals are appointed not necessarily to foot the election bill themselves —though of course they will be expected to make significant donations—but because they are deeply embedded in domestic business networks. Their job as a campaign director is to convince other tycoons and wealthy business elites to give generously to their candidate. At the presidential level, the true cost of a campaign is difficult to estimate. The official spending by President Jokowi in 2019 for his re-election bid was Rp 606 billion (US$ thirty-eight million), of which his campaign team claimed that just over Rp 250 billion (US$ sixteen million) was contributed by forty companies.Footnote35 But the real costs are likely much higher, as candidates dramatically under-report most private donations. One politician told journalists that he believed the true cost of a presidential campaign is close to Rp 5 trillion (approximately US$320 million).Footnote36

For much of the post-authoritarian period, the country’s largest conglomerates, most of which are owned by ethnic Chinese Indonesian families, have distributed campaign donations in a relatively even manner to the various presidential tickets and parties. While their largest donations go to the candidate most likely to win, they also channel funds to all political parties as a kind of insurance policy against extortion and potential political attacks, given the long history of social and political discrimination in Indonesia against the country’s ethnic Chinese minority. Non-ethnic Chinese businesspeople are less predictable in how, whether, and to whom they choose to donate, so the role of tycoons like Erick Thohir, Arsjad Rasjid, and Rosan Roeslani when they head presidential campaign teams is to draw in funds from a range of business actors.Footnote37 In return, they may hope to be given a position in government once the election is over. For example, Jokowi appointed Erick Thohir Minister of State-Owned Enterprises in 2019, an infamously “wet” position because of the contracts the ministry controls and the state banks it oversees.

Beyond cost considerations, there are other factors at play too, particularly when it comes to executive-level trends. Under Jokowi, the country’s first businessperson president, executive government has come to be dominated by extraordinarily wealthy tycoons, such as the aforementioned Erick Thohir and Nadiem Makarim, as well as Luhut Panjaitan (co-ordinating Minister for Investment and Maritime Affairs), Sandiaga Uno (Minister for Tourism), and Bahlil Lahadalia (Chair of the State Investment Board). Jokowi’s choice of ministers reflects, in many ways, the preferences of his occupational class. In interviews, former ministers described his cabinet appointments as driven by an attraction to successful entrepreneurs. One former minister with an economics portfolio during the president’s first cabinet said, “Jokowi likes people who have ‘made it’ in his world, the business world.”Footnote38 A current cabinet minister, himself a businessperson politician, explained, “I think Jokowi chooses businesspeople because he believes we know how to get things done quickly.”Footnote39

Other government insiders interviewed for this study were more cynical about the president’s motivations. According to a former cabinet minister with experience in economic portfolios during Jokowi’s first administration, prominent businesspersons in Jokowi’s cabinets, particularly his second cabinet, ultimately were selected because they had immense financial resources: “it is really all about money—who helped finance the 2019 campaign? Who paid for Jokowi’s son’s wedding?” he said, referring to Erick Thohir.Footnote40 Another former minister suggested that over time Jokowi has become increasingly concerned with fostering links with the sorts of wealthy, powerful politico-business elites who could continue to represent and protect his interests once he was no longer in the presidential palace:

You have to distinguish between private sector professionals in government, like Tom Lembong [former Minister of Trade and investment banker], and those who are really oligarchs and want to use their wealth for political purposes, like Erick Thohir or Bahlil … Jokowi wanted more of this second group of businesspeople around him as time went on.Footnote41

The political veneration of business

The privatization of political office in recent decades both reflects and drives a broader politico-cultural shift in Indonesia—the social legitimization of capital as a major political and policy actor. Analysts of state-business relations during the New Order characterized the private sector as inhabiting an inferior social position vis-a-vis the civilian bureaucracy and the military. The reasons for this unequal relationship were twofold. First, the Javanese aristocratic (priyayi) roots of bureaucratic power continued to shape perceptions among the governing elite, who took a negative view of groups that sat outside of these circles, including businesspeople. Second, as Andrew MacIntyre points out, this “traditional disdain toward business was … greatly sharpened by the fact that the business community [was] dominated by Chinese Indonesians,” generating a lack of trust and nationalist suspicion among state actors toward the business class.Footnote43 During the late New Order era, businesspersons routinely grumbled that government did not take them seriously, and “openly complained that state officials regarded themselves as being above businesspeople.”Footnote44

This disregard, or even disdain, on the part of the bureaucracy toward business elites was buttressed by a state ideology that emphasized communitarian principles, collectivism, and mutual assistance as the foundations of national development, and rejected persaingan tidak sehat (“unhealthy competition”).Footnote45 Assessing state-business relations in the late 1980s and the apparent “flaccidity of [economic] interest groups,” Jamie Mackie noted:

… the principal tenets of capitalist ideology are still not widely accepted as legitimate or appropriate for Indonesian society; both acquisitiveness and self-interest are widely regarded as reprehensible qualities in traditional Indonesian value-systems and they have not yet been incorporated into the national ideology as desiderata for the sake of development.Footnote46

Today, politicians routinely emphasize the value of a being an enterprising and innovative individual. Business politicians increasingly promote their occupational class with pride. High-profile politicians like Erick Thohir and Sandiaga Uno regularly offer citizens tips on how to grow a successful business via social media platforms, at conferences, or at meetings with community members. This advice is often directed at younger Indonesians, encouraging them to be “enterprising individuals” to improve their lot in life. Footnote48 Minister of Education and tech billionaire Nadiem Makarim tells young Indonesians they must be “brave enough to take risks” and to “innovate and be productive.”Footnote49 President Jokowi has spoken with pride of being a member of the HIPMI “family” when he was a young businessperson starting out in the furniture industry in Solo.Footnote50 His two sons, Gibran and Kaesang, each active now in politics (Gibran as the vice-president elect and Kaesang as the chairperson of Partai Solidaritas Indonesia, PSI) are lauded in the media and by other politicians for their roles in starting or financing a range of business ventures before they entered politics.Footnote51

This new political embrace of entrepreneurship and private business success is, to be sure, connected to broader changes in Indonesian society, in particular the growth of the middle class and diversification of the economy. A 2020 study by the World Bank reported that middle class citizens are increasingly likely to establish and run their own business.Footnote52 The widespread use of social media in Indonesia has also prompted an explosion in digital entrepreneurship and online business ventures designed to reach middle class consumers.Footnote53 The Gross Merchandise Value (GMV) of goods traded online in Indonesia reached US$ fifty-two billion in 2022, far exceeding that of any other country in the region.Footnote54 Although Indonesia’s lead on this measure is partly a function of population size, the country is also among the fastest growing e-commerce markets globally and, according to one report, has the sixth largest number of start-ups in the world.Footnote55

Popular perceptions toward business are changing as well. Between 2013 and 2022, the number of Indonesians who viewed entrepreneurship as a desirable career path tracked steadily up, from seventy-one to seventy-six percent. More strikingly, the number of people who felt there were “good opportunities” to start their own business rose from just under fifty percent in 2013 to eighty-seven percent in 2022.Footnote56 These shifts suggest a widening social base of support for the private business sector and the direct political role that businesspeople increasingly play.

Being rich in Indonesia is also no longer, as it once often was, necessarily connected to rent-seeking industries. For example, the boom in digital services is a new pathway to wealth. While the richest Indonesians almost all still have interests in cash crops and mining, the country’s new tech entrepreneurs have enormous media and political visibility. Indonesia now has twelve tech unicorns—the second largest number after Singapore among ASEAN members—and the merger of two of these, Gojek and Tokopedia, produced a “decacorn,” GoTo, with a net value of more than US$ ten billion.Footnote57 The public face of business success is no longer limited to timber or coal barons. In turn, more and more Indonesians, and in particular younger members of the middle class, see pathways to wealth and status via cleaner economic sectors. The fact that President Jokowi appointed Nadiem Makarim, founder and former CEO of Gojek, as Minister of Education is arguably the most powerful demonstration of the status that these new corporate figures hold in the eyes of the president. Far from expressing either scepticism or suspicion toward the business world, as was the case during the New Order, today’s politicians are keen to associate themselves with successful homegrown entrepreneurs.

In interviews, businessperson politicians and members of business associations spoke of this reversal in the perception of state officials and bureaucrats toward business, which they described as now characterized by respect and dependence. Even when it comes to something as apparently transactional as heading political campaigns, sources emphasized a change in perception about the political role of businesspeople. One business politician and senior member of Kadin explained:

Previously, party elites saw military generals as the kind of people who had the skills to run a big campaign, you know because they understood logistics and how to handle a crisis; not anymore, it’s the businesspeople who are considered best at this now.Footnote58

The characterization of business elites in politics as self-serving oligarchs remains dominant among academics, journalists, and activists in Indonesia. The notion of a democracy captured by predatory private interests continues to be a compelling framework for understanding contemporary Indonesian politics. None of the propositions I have put forward in this paper are intended to challenge these prevailing ways of understanding state-business relations in Indonesia. Whether at the local or national government level, the overlap of business and state power continues to be routinely driven by rent-seeking and corruption.

My point is to illustrate that, beyond the influence of oligarchic interests on democratic institutions, there is a broader and under-appreciated politico-cultural transformation taking place, whereby corporate figures are increasingly celebrated and valued not only for their financial success but also for their political prowess and management of state institutions.

How businesspeople govern

How do businesspeople govern and reorient policy trajectories in Indonesia, and how does Indonesia’s experience compare with similar transformations in other parts of the world? A growing number of private sector actors are moving into government in other countries, motivating more scholars to examine the policy impacts of this trend.Footnote60 Much of this research emphasizes that private sector leadership brings a strong push for market-friendly policies and neoliberal modes of governance. Some scholars have shown that business leadership in the public sector can have positive effects because businesspeople are more likely to pursue reform, drive pro-growth policies, and attract investment.Footnote61 Leaders with these backgrounds are known to systematically prioritize infrastructure and investment over other policy areas, and this has obvious benefits for economic connectivity and growth. But scholars have also shown that, in a range of countries, where there are high numbers of executive-level politicians with business backgrounds, there tends to be lower levels of government spending, in particular on public and social services and redistributive programs.Footnote62

While it is beyond the scope of the current study to provide a systematic account of policy impacts under the leadership of Indonesia’s business politicians, I suggest that a similar picture painted by the comparative literature is emerging in Indonesia. President Jokowi is well-known to be obsessed with the country’s position on rankings like the Global Competitiveness Index, The World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business Index, and the Logistics Performance Index, because he perceives these to be the most important markers of developmental success.Footnote63 Key indicators drawn from The World Bank’s Databank database reveal his administration’s priorities in this regard. For example, the average number of days it takes to start a business shrank from eighty to just thirteen under Jokowi. In turn, the country’s ranking on the Ease of Doing Business index jumped from 120 out of 190 countries in 2014 to 73 in 2020. The total number of different taxes paid by businesses fell from fifty-three in 2013 to twenty-six in 2019 (the latest year for this dataset). The 2020 Omnibus Law on Job Creation, a cornerstone of Jokowi’s reforms during his second term, loosened investment rules and gave space for new incentives for domestic and private business. The law also introduced new constraints on labor and minimum wage negotiations. One analyst described the intervention as “the most neo-liberal deregulation drive in modern Indonesian history.”Footnote64

From the perspective of investors and many economists, these sorts of changes are needed to boost growth and generate more employment opportunities; for critics, the government’s shift toward a more pro-business orientation comes at the cost of support for other areas of governance.Footnote65 Indeed, and in line with findings from the comparative literature, overall government spending in Indonesia as a percentage of GDP tracked down until the Covid-19 pandemic, after a period of consistent increases during the previous Yudhoyono administration. Tax revenue as a percentage of GDP fell from 11.3 percent in 2014 to nine percent in 2022. And while the poverty rate has continued to fall under President Jokowi, certain social spending has stagnated or regressed. For example, spending on health as a proportion of GDP remained stagnant at just under three percent during Jokowi’s presidency until the Covid 19 pandemic, after a decade of incremental increases under President Yudhoyono. And the proportion of spending on education tracked downward, from 3.4 percent of GDP in 2013 to 2.7 percent in 2017, before rising to three percent in 2022.

Meanwhile, policy trajectories within particular ministries have taken a liberal turn under the leadership of business politicians. At the height of the COVID pandemic in late 2020, President Jokowi appointed the banker Budi Gunadi Sadikin (described earlier) as the new Health Minister and tasked him with managing Indonesia's medical response, and in particular the roll-out of vaccinations which, under Sadikin's predecessor (a career doctor for the military) had been woefully inadequate. Most assessments of Sadikin's performance praised his effective approach to vaccine procurement, while at the same time emphasising that, as Charlotte Setijadi put it, his appointment “reflected Jokowi's view of the pandemic as primarily an economic and managerial problem”, rather than a medical crisis.Footnote66 As a result, the government avoided strategies to mitigate the virus that would have had economic consequences, such as mobility restrictions and shutdowns, until the Delta variant began devastating the country in July and August of 2021.Footnote67

Sadikin's tenure as minister was also marked by a major legal change: the introduction of a new health law (Law 17/2023). Despite facing opposition from the bureaucracy, this new law opens the sector to more foreign staff, including nurses and doctors, and removes rules mandating that a minimum of five percent of the national budget be allocated to health. The law also allows complete foreign ownership of hospitals and healthcare facilities. Sadikin has also supported ways to source new and innovative digital solutions from both the public and private sector to help deal with budget and health information challenges.Footnote68 He has advocated for policies to, as he puts it, “disrupt.. democratize…and smash” old ways of developing health and financial systems.Footnote69 It is too early to judge the impact of these liberalizing reforms. On the one hand, health indicators in Indonesia have lagged for decades compared to neighbouring countries, so innovative interventions to try to improve services are welcomed by many observers; others, however, fear that reducing budget commitments to the sector, and increasing privatization, will only widen stark inequalities of access.Footnote70

Education is perhaps the most extreme example of how policy trajectories have changed under business leadership. One of Nadiem Makarim's major reforms is the Independent Teaching (Merdeka Megajar) program for schools across the country. The program provides an online teaching and learning platform and sets up new digital budgeting for schools. The program's goal is to use technology to encourage teachers to innovate, and to provide a flexible online system for teaching, curriculum development, and school management. Nadiem's university reforms take a similar approach. The Independent Campus (Kampus Merdeka) program aims to transform Indonesia's state universities from entities that depend on state funding and centrally determined accreditation systems, into financially and academically autonomous institutions. The objective is to “increase the nation's competitiveness through close cooperation with the Business World and Industrial World, and top world universities.”Footnote71 The ministry also “hopes to increase [students'] competence in building business models” and to produce one million entrepreneurs by 2024 by enabling university students to take time away from their degrees to work at private enterprises.Footnote72

It is, again, too early to judge with certainty the impact of these reforms. But at this stage analysts see little evidence that autonomy is driving productivity among students and staff, and instead old problems of unaffordable fees and unequal access to higher education remain the sector's perennial problems.Footnote73 When it comes to the digital reforms for schools, experts also warn that “implementation…has been far from optimum given 40% of Indonesian schools do not even have access to a reliable internet connection [and the] policy reforms have had little impact on access.”Footnote74

Historically, attempts to reform Indonesia’s bureaucracy in line with more neoliberal modals have faced pockets of strong resistance and a continued “mistrust of private sector participation and solutions, in what government officials claim as the state’s business.”Footnote75 As Andrew Rosser argued in his 2016 study of failed reform in Indonesia’s higher education sector, resistance from within the bureaucracy had long ensured that the “centralist and predatory system of higher education established under the New Order [was sustained],” derailing attempts by reformers to shift toward a more corporate model of delivering education services.Footnote76 So, the introduction of business politicians with new responses to problems of quality, corruption and inefficiency is a welcome shift. Early assessments, however, warn that liberalizing these sectors can, as has been the case in other countries, entrench rather than address inequalities of access.

Allies, not enemies, of the state

The examples surveyed above are revealing of the way in which corporate principles and a business-oriented set of priorities have inspired the Jokowi administration’s approach to reform. But a critical caveat is in order. The growing business presence within politics and government in Indonesia has not led to either a thorough embrace of free market ideas or a “suspicion of the state” that is often associated with business influence over government, and with neoliberal ideologies more generally.Footnote77

Instead, state ownership and statist economic interventions, both of which are antithetical to neoliberalism, remain popular among members of Indonesia’s political and policymaking class. Under Jokowi, for example, the government stopped what had been a consistent, albeit incremental, program of privatizing SOEs since the start of the 2000s, and instead invested heavily in SOEs and used them to execute major infrastructure and extractive projects.Footnote78 In fact, state capital investments into SOEs more than doubled, from around 1.5 percent of GDP in 2010 (approximately 100 trillion rupiah) to 3.5 percent in 2018 (just under 5 trillion rupiah).Footnote79 This seemingly incongruous blend of state ownership and intervention, with a pro-business policy orientation is, I suggest, characteristic of Jokowi’s “new developmentalist” approach of the past decade.Footnote80 Under Jokowi the government has served the interests of domestic capital and embraced a market mode of action when it comes to reform, while maintaining a major role for state-owned business as agents of fast-paced development.

Another reason why the rise of business politicians has not yet led to a more widespread embrace of privatization and free-market approaches concerns the types of businesspeople entering office in Indonesia. Many of the country’s political oligarchs draw their wealth from sectors that require close relations with the state.Footnote81 Control of major state projects by SOEs does not necessarily mean the exclusion of domestic private interests. Instead, SOEs are a source of major subcontracting opportunities for domestic firms, and SOEs remain critical tools for oligarchs, party elites, and the president to access and control the distribution of patronage resources and business opportunities.Footnote82

The state thus remains an ally and source of wealth for many business elites who depend on rent-rich industries like mining, plantations, and construction, all of which lean on the state for permits and contracts. That business politicians in Indonesia may accept certain state interventions, and not advocate for free markets in the way they do elsewhere, is an important line of enquiry for future research—especially as the sectoral base of the country’s business politicians may start to shift, with individuals from the tech or finance sectors taking more direct roles in politics. Indeed, there is a need for more systematic analysis of the sectoral interests of Indonesia’s many thousands of businesspeople politicians at both the national and local levels. I have focused in this paper on mapping the changing composition of Indonesia’s political elite and parsed mostly demand side reasons for this change—that is, the increasing cost of politics and the preferences of the president. We still have limited understanding of the supply side of this trend, and of what motivates different types of businesspersons to enter government.Footnote83

Conclusion

The central role that capital plays in Indonesia’s democratic institutions has long been a preoccupation of country experts. While there are many points of disagreement and emphasis, most scholars have underscored a tight overlap between the worlds of politics and business, with many focused on the often murky connections and alliances among state officials, oligarchs, and local bosses.Footnote84 My intention is not to dismiss or challenge these characterizations of post-New Order governance; entrenched patterns of clientelist politics mean that rent-seeking, corruption, and conflicts of interest remain the everyday stuff of Indonesian politics.

I have instead focused on a parallel and under-analyzed transformation of the political and social place of business. From tech entrepreneurs to mining giants and banking executives, from family-owned conglomerates to medium-sized businesses, businesspeople are increasingly entering politics at all levels of government in Indonesia. Once considered inferior political and policy actors during Suharto’s New Order, businesspersons now enjoy more political power, and entrepreneurship and capitalist success are valued in new and politically important ways. The effects of this trend on governance and representation are critical areas for further study. We know from comparative research that businesspersons in politics tend to pursue more market-oriented policies that favour business interests over those of other sectors of society. Evidence I have surveyed in this paper indicates similar sorts of patterns have emerged during the decade of rule by businessperson-cum-politician, President Jokowi.

Still, there is much we do not know about what motivates an increasingly diverse set of businesspeople to enter politics, and what the fusion of private power and public office means for the country’s long term economic and democratic evolution. For most of the democratic period, analysts have emphasized the capture of the state by oligarchic characters. Today, in some ways, Indonesia's businesspeople do not need to capture the state; instead, it is increasingly entrusted to them.

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank Indikator Politik, and in particular Kennedy Muslim, Rizki Rahmadian, and Tri Rizki Putra for their excellent contribution to data collection on politicians’ backgrounds. I am most grateful to colleagues in ANU’s Department of Political and Social Change, along with the editor and anonymous reviewers, for providing incisive feedback on earlier versions of this paper.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Eve Warburton

Eve Warburton is a Research Fellow in the Department of Political and Social Change, Coral Bell School of Asia Pacific Affairs at Australian National University. She is also Director of ANU's Indonesia Institute in the College of Asia and the Pacific.

Notes

1 Winters Citation2013; Hadiz and Robison Citation2013.

2 Ministers can hire special staff to provide advice on policy issues. Special staff, unlike other staff members in a ministry, do not need to come from the bureaucracy but can instead be brought in from outside government, including from business, academia, and civil society.

3 Aspinall and Berenschot Citation2019; Muhtadi Citation2019.

4 Mackie Citation1990; MacIntyre Citation1991, chapter 1.

5 Rosser Citation2001; Robison and Rosser Citation1998.

6 Aspinall Citation2012.

7 Aspinall Citation2012, 30.

8 Carroll Citation2012.

9 All interviewees spoke on the condition of anonymity. While I indicate their positions in government or business, I have withheld information that might reveal their identities. In terms of the selection of interviewees, I generated a purposive sample of potential persons based on their membership in executive government (current or previous cabinets since 2004) and their profiles as established businesspersons. The interview data are not intended to constitute a representative picture of the preferences of all business politicians, but rather are designed to provide insight into the context behind the trends identified in my analysis of the database.

10 Mietzner Citation2013; Winters Citation2013.

11 Ardito Ramadhan and Dani Prabowo Citation2020.

12 Aspinall and Berenschot Citation2019, 192.

13 Tempo Citation2019; Republika Citation2014.

14 Aspinall 2013, 228.

15 Poczter and Pepinsky Citation2016.

16 It is not illegal for parliamentarians to hold such private sector positions so long as their business interests do not overlap with their parliamentary portfolios.

17 Mietzner Citation2023, 194.

18 Kompas Citation2009.

19 McLeod Citation2008; Ascher Citation1998.

20 A brief word on the data, and how we have identified and counted ministers’ occupations. Each minister’s prior occupation is established by drawing on the biodata made available through profiles on ministerial websites, media reports, and Wikipedia. Given that all of these individuals have a prominent public profile, information on their occupation(s) prior to entering office was relatively accessible. Together with a team of researchers from Indikator Politik, one of Indonesia’s preeminent political research institutes, we coded occupations using categories commonly used in national surveys. The main challenge in the process of coding was that ministers have often had several careers, and they often appear several times in the dataset as they as they have been appointed to different positions in different cabinets. The coding system, therefore, counts and codes each prior occupation of a minister before he or she entered office, and counts them each time they enter cabinet. Luhut Binsar Panjaitan, for example, is a retired military general and a prominent businessperson with major coal and palm oil investments. Both occupations are critical to his identity as a politician and minister so coding him as either/or a businessperson or former general would undermine the analysis. The total number of career positions, therefore, exceeds the total number of ministers, and the number of appointed ministers exceeds the number ministries. Also note that the results in exclude ministers with careers in state-owned enterprises before entering cabinet, because the focus of this study is on private business influence within government.

21 It is widely understood that politicians are likely to be dramatically under-reporting the true value of their assets, but these data constitute the best and most consistent way to judge and compare politicians’ wealth.

22 Wealth figures are adjusted for the average level of inflation during each cabinet period using the World Bank’s Consumer Price Index.

23 Interview, former cabinet minister (2014–2019) and former executive in a domestic conglomerate, September 4, 2023, Jakarta.

24 Interview, current cabinet minister and businessperson, September 4, 2023, Jakarta.

25 Interview, former cabinet minister (2015-2019) and businessperson, June 9, 2023, Jakarta

26 Dewi Citation2022.

27 Nurhakim Citation2022; The Jakarta Post Citation2022.

28 Aspinall and Berenschot Citation2019, 192.

29 Aspinall Citation2013; Mietzner Citation2015; Muhtadi Citation2019; Aspinall and Berenschot Citation2019.

30 Aspinall and Berenschot Citation2019, 210.

31 Muhtadi Citation2019.

32 This is an Indonesian term to describe opportunities for corrupt politicians to extract rents from their government positions.

33 Interview, DPR member from PDI-P (2019-2024), November 2, 2023, Jakarta.

34 Interview, DPR member from Golkar Party, August 31, 2023, Jakarta.

35 Asmara Citation2019.

36 Sorongan Citation2023.

37 Interview, senior member of APINDO, November 1, 2023, Jakarta.

38 Interview, former cabinet minister (2020-2022) August 29, 2023, Jakarta.

39 Interview, cabinet minister (2019–2024) and former businessperson, September 4, 2023, Jakarta.

40 Interview, former cabinet minister (2015-2019) and businessperson, June 9, 2023, Jakarta.

41 Interview, former cabinet minister and (2014-2019) and businessperson, September 4, 2023, Jakarta.

42 Mietzner Citation2023.

43 MacIntyre Citation1991, 45.

44 Citation1991, 45.

45 MacIntyre Citation1991, 46.

46 Mackie Citation1990, 22–23.

47 Robison Citation1986; MacIntyre Citation1991; Shin 199.

48 Safitri and Setiawan Citation2023; www.jpnn.com Citation2023.

49 Kamil and Krisiandi Citation2020.

50 Ali Citation2023.

51 Tempo Citation2023; Bhwana 2023.

52 The World Bank Citation2020, 27.

53 Akbar Citation2023.

54 The next highest GMV was Thailand with just US$ fourteen billion. Akbar Citation2023.

55 Palaon Citation2023.

56 Global Entrepreneur Monitor.

57 SEADS Citation2023.

58 Interview, former cabinet minister (2019–2024), August 29, 2023, Jakarta.

59 Interview, senior member of APINDO, November 1, 2023, Jakarta.

60 Carnes and Lupu Citation2015; Szakonyi Citation2021; Weschle Citation2022.

61 Neumeier Citation2018; Dreher et al. Citation2009.

62 Borwein Citation2022; Szakonyi Citation2021; Babenko, Fedaseyeu, and Zhang Citation2023; Kirkland Citation2021.

63 Warburton Citation2018.

64 Mietzner Citation2021, 108.

65 Sholikin Citation2020; Suroyo and Sulaiman Citation2022.

66 Setijadi Citation2021, 301.

67 Mietzner Citation2021.

68 Coordinating Ministry for Politics, Law and Security 2022.

69 BKPK Citation2022.

70 Sutarsa Citation2023.

71 Director General for Higher Education, Research and Technology 2022.

73 Albar Citation2023.

74 Albar Citation2023

75 Turner, Prasojo, and Sumarwono Citation2022, 336.

76 Rosser 2016.

77 Ferguson Citation2010.

78 Kim and Sumner, Citation2021.

79 Kim Citation2021, 421.

80 Warburton 2016; Warburton Citation2018.

81 Warburton Citation2023.

82 Apriliyanti Citation2023.

83 But see Syechbubakr (Citation2024) for one exploration of this topic.

84 van Klinken et al. Citation2010; Mietzner Citation2023.

References

- Akbar, Caesar. 2023. “Siapa Untung Setelah Tiktok Shop Ditutup.” Tempo, October 4. Accessed November 8, 2023: https://koran.tempo.co/read/berita-utama/484811/siapa-untung-setelah-tiktok-shop-ditutup.

- Albar, Rafsi. 2023. “Grading Nadiem’s Education Reforms.” Indonesia at Melbourne (blog). December 12. Accessed March 12, 2024: https://indonesiaatmelbourne.unimelb.edu.au/grading-nadiems-education-reforms/.

- Ali, Ichsan. 2023. “Sebut HIPMI Keluarga Sendiri, Jokowi Buka Peluang Cawe-cawe Capres 2024.” investor.id, August 31. Accessed March 14, 2023: https://investor.id/national/339346/sebut-hipmi-keluarga-sendiri-jokowi-buka-peluang-cawecawe-capres-2024.

- Apriliyanti, Indri Dwi. 2023. “Continuity and Complexity: A Study of Patronage Politics in State-Owned Enterprises in Post-Authoritarian Indonesia.” Critical Asian Studies 55 (4): 516–537.

- Ardito Ramadhan, Kompas Cyber, and Dani Prabowo. 2020. “KPK Khawatir, Hampir Separuh Calon Kepala Daerah Berlatar Belakang Pengusaha.” Kompas, December 4. Accessed March 12, 2024: https://nasional.kompas.com/read/2020/12/04/14394621/kpk-khawatir-hampir-separuh-calon-kepala-daerah-berlatar-belakang-pengusaha.

- Ascher, William. 1998. “From Oil to Timber: The Political Economy of Off-Budget Development Financing in Indonesia.” Indonesia 65: 37–61.

- Asmara, Chandra Gian. 2019. “Dibantu Pengusaha, Dana Kampanye Jokowi-Ma’ruf Capai Rp 606 M.” CNBC Indonesia, May 2. Accessed March 15, 2024: https://www.cnbcindonesia.com/news/20190502203234-4-70223/dibantu-pengusaha-dana-kampanye-jokowi-maruf-capai-rp-606-m.

- Aspinall, Edward. 2012. “A Nation in Fragments: Patronage and Neoliberalism in Contemporary Indonesia.” Critical Asian Studies 45 (1): 27–54.

- Aspinall, Edward. 2013. “The Triumph of Capital? Class Politics and Indonesian Democratisation.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 43 (2): 226–242.

- Aspinall, Edward, and Ward Berenschot. 2019. Democracy for Sale: Elections, Clientelism, and the State in Indonesia. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Babenko, Ilona, Viktar Fedaseyeu, and Song Zhang. 2023. “Executives in Politics.” Management Science 69 (10): 6251–6270.

- Bhwana, Petir Garda. 2023. “Kaesang Pangarep Shares Business Tips to Gain Success.” Tempo.Co, January 31. Accessed March 10, 2024: https://en.tempo.co/read/1170795/kaesang-pangarep-shares-business-tips-to-gain-success.

- Borwein, Sophie. 2022. “Do Ministers’ Occupational and Social Class Backgrounds Influence Social Spending?” Politics, Groups, and Identities 10 (4): 558–580.

- Carnes, Nicholas. 2013. White-Collar Government: The Hidden Role of Class in Economic Policy Making. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Carnes, Nicholas, and Noam Lupu. 2015. “Rethinking the Comparative Perspective on Class and Representation: Evidence from Latin America.” American Journal of Political Science 59 (1): 1–18.

- Carroll, Toby. 2012. “Working On, Through and Around the State: The Deep Marketization of Development in the Asia-Pacific.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 42 (3): 378–404.

- Coordinating Ministry for Politics, Law, and Security, Government of Indonesia. 2022. “Indonesia Dorong Efisiensi Anggaran Kesehatan Melalui Inovasi Teknologi,” November 13. Accessed March 10, 2024: https://polkam.go.id/indonesia-dorong-efisiensi-anggaran-kesehatan-melalui-inovasi-teknologi/.

- Davidson, Jamie S. 2015. Indonesia’s Changing Political Economy. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Dewi, Intan Rakhmayanti. 2022. “Karyawan Startup Ramai-ramai ke Pindah Kementerian, Ada Apa?” CNBC Indonesia, September 29. Accessed March 10, 2024: https://www.cnbcindonesia.com/tech/20220929142000-37-375955/karyawan-startup-ramai-ramai-ke-pindah-kementerian-ada-apa.

- Director General for Higher Education, Research and Technology, Government of Indonesia. 2022. “Program Kompetisi Kampus Merdeka (PK-KM) Tahun Anggaran 2022.” Accessed March 10, 2024: https://pkkmdikti.kemdikbud.go.id/files/Panduan%20Penyusunan%20Rencana%20Implementasi%20Tahun%20Kedua%20-%20PKKM%20Tahun%20Anggaran%202022.pdf.

- Dreher, Axel, Michael J. Lamla, Sarah M. Lein, and Frank Somogyi. 2009. “The Impact of Political Leaders’ Profession and Education on Reforms.” Journal of Comparative Economics. 37 (1): 169–193.

- Ferguson, James. 2010. “The Uses of Neoliberalism.” Antipode 41 (1): 166–184.

- Global Entrepreneur Monitor. 2022. “Entrepreneurship in Indonesia.” Accessed November 17, 2023: https://www.gemconsortium.org/economy-profiles/indonesia-2.

- Guild, James. 2019. “In Defence of Jokowinomics.” New Mandala (blog), March 22. https://www.newmandala.org/in-defence-of-jokowinomics/.

- Hadiz, Vedi R., and Richard Robison. 2013. “The Political Economy of Oligarchy and the Reorganization of Power in Indonesia.” Indonesia 96 (1): 35–57.

- The Jakarta Post. 2022. “Nadiem Clarifies ‘Shadow Organization’ Comment after Backlash,” September 28. Accessed March 16, 2024: https://www.thejakartapost.com/indonesia/2022/09/28/nadiem-clarifies-shadow-organization-comment-after-backlash.html.

- Kamil, Irfan, and Krisiandi. 2020. “Nadiem Minta Generasi Muda Berani Ambil Risiko untuk Hadirkan Inovasi.” Kompas, November 2. Accessed March 10, 2024: https://nasional.kompas.com/read/2020/11/02/20161001/nadiem-minta-generasi-muda-berani-ambil-risiko-untuk-hadirkan-inovasi.

- Kim, Kyunghoon. 2021. “Indonesia’s Restrained State Capitalism: Development and Policy Challenges.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 51 (3): 419–446.

- Kim, Kyunghoon, and Andy Sumner. 2021. “Bringing State-Owned Entities Back into the Industrial Policy Debate: The Case of Indonesia.” Structural Change and Economic Dynamics 59 (December): 496–509.

- Kirkland, Patricia A. 2021. “Business Owners and Executives as Politicians: The Effect on Public Policy.” The Journal of Politics 83 (4): 1652–1668.

- Klinken, Gerry van and Edward Aspinall. 2010. “Building Relations: Corruption, Competition, and Cooperation in the Construction Industry.” In The State and Illegality in Indonesia, edited by Edward Aspinall and Gerry van Klinken, 139-151. Leiden: Brill.

- Kompas. 2009. “Inilah Sembilan Tim Sukses SBY,” April 28. Accessed March 12, 2024: https://nasional.kompas.com/read/2009/04/28/08441821/~Nasional.

- MacIntyre, Andrew. 1991. Business and Politics in Indonesia. Sydney: Allen & Unwin Pty Ltd.

- Mackie, J.A.C. 1990. “Property and Power in Indonesia.” In The Politics of Middle Class Indonesia, edited by Richard Tanter and Kenneth Young, 71-94. Australia: Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Monash University.

- McLeod, Ross H. 2008. “Inadequate Budgets and Salaries as Instruments for Institutionalizing Public Sector Corruption in Indonesia.” Southeast Asia Research 16(2): 199–223.

- Mietzner, Marcus. 2013. Money, Power, and Ideology: Political Parties in Post-Authoritarian Indonesia. Hawaii: University of Hawaii Press.

- Mietzner, Marcus. 2015. “Dysfunction by Design: Political Finance and Corruption in Indonesia.” Critical Asian Studies 47 (4): 587–610.

- Mietzner, Marcus. 2021. “Indonesia in 2020: COVID-19 and Jokowi’s Neo-Liberal Turn.” Southeast Asian Affairs 2021 (1): 107–121.

- Mietzner, Marcus. 2023. The Coalitions Presidents Make: Presidential Power and its Limits in Democratic Indonesia. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Ministry of Health, Government of Republic of Indonesia. 2022. “Penghargaan Juara Finance and Health HACKATHON 2022.” Badan Kebijakan Pembangunan Kesehatan | BKPK Kemenkes (blog), November 13. Accessed March 10, 2024: https://www.badankebijakan.kemkes.go.id/penghargaan-juara-finance-and-health-hackathon-2022/.

- Muhtadi, Burhanuddin. 2019. Vote Buying in Indonesia: The Mechanics of Electoral Bribery. London; New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Neumeier, Florian. 2018. “Do Businessmen Make Good Governors?” Economic Inquiry 56 (4): 2116–2136.

- Nurhakim, Farid. 2022. “Ada Tim Bayangan, Vox Populi: Nadiem Tak Percaya ASN Kemdikbud.” tirto.id, September 29. Accessed March 10, 2024: https://tirto.id/ada-tim-bayangan-vox-populi-nadiem-tak-percaya-asn-kemdikbud-gwKE.

- Palaon, Hilman. 2023. “Indonesia’s Digital Success Deserves More Attention.” Lowy Interpreter (blog), June 1. Accessed March 10, 2024: https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/indonesia-s-digital-success-deserves-more-attention.

- Poczter, Sharon, and Thomas B. Pepinsky. 2016. “Authoritarian Legacies in Post–New Order Indonesia: Evidence from a New Dataset.” Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 52 (1): 77–100.

- Republika. 2014. “Ini Dia Profil Anggota Legislatif 2014-2019,” October 9. Accessed March 10, 2024: https://www.republika.co.id/berita/koran/teraju/14/10/09/nd6caa-ini-dia-profil-anggota-legislatif-20142019.

- Robison, Richard. 1986. Indonesia: The Rise of Capital. Sydney: Allen & Unwin.

- Robison, Richard, and Andrew Rosser. 1998. “Contesting Reform: Indonesia’s New Order and the IMF.” World Development 26 (8): 1593–1609.

- Rosser, Andrew. 2001. The Politics of Economic Liberalization in Indonesia: State Market and Power. London: Routledge.

- Rosser, Andrew. 2015. “Neo-liberalism and the Politics of Higher Education Policy in Indonesia.” Comparative Education 52 (2): 109-135.

- Safitri, Kiki, and Sakina Rakhma Diah Setiawan. 2023. “Tips Investasi dari Erick Thohir untuk Anak Muda.” Kompas, October 30. Accessed March 10, 2024: https://money.kompas.com/read/2023/10/30/090600426/tips-investasi-dari-erick-thohir-untuk-anak-muda.

- SEADS. 2023. “Indonesia’s Technology Startups: Voices from the Ecosystem.” SEADS, July 3. Accessed March 10, 2024: https://seads.adb.org/report/indonesias-technology-startups-voices-ecosystem.

- Setijadi, Charlotte. 2021. “The Pandemic as Political Opportunity: Jokowi’s Indonesia in the Time of Covid-19.” Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 57 (3): 297–320.

- Shin, Yoon Hwan. 1991. “The Role of Elites in Creating Capitalist Hegemony in Post-Oil Boom Indonesia,” Dissertation, Cornell University Southeast Asia Program. Accessed March 16, 2024: https://hdl.handle.net/1813/54716.

- Sholikin, M. Nur. 2020. “Explainer: Jokowi’s Omnibus Bills, and Why Critics Want to Put on the Brakes.” Indonesia at Melbourne (blog), June 17. Accessed March 10, 2024: https://indonesiaatmelbourne.unimelb.edu.au/explainer-jokowis-omnibus-bills-and-why-critics-want-to-put-on-the-brakes/.

- Sorongan, Tommy Patrio. 2023. “‘Ngebet’ Jadi Capres RI, Siapin Modal Rp 5 Triliun!” CNBC Indonesia, May 27. Accessed March 10, 2024: https://www.cnbcindonesia.com/news/20230527092426-4-441064/ngebet-jadi-capres-ri-siapin-modal-rp-5-triliun.

- Suroyo, Gayatri and Stefanno Sulaiman. 2022. “Explainer: What’s at Stake with Indonesia’s Controversial Jobs Creation Law,” June 9. Accessed February 22, 2024: https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/whats-stake-with-indonesias-controversial-jobs-creation-law-2022-06-09/.

- Sutarsa, Nyoman. 2023. “Indonesian Health System Reform no Simple Fix for Inequity.” East Asia Forum, September 28. Accessed Marc 10, 2024: https://eastasiaforum.org/2023/09/28/indonesian-health-system-reform-no-simple-fix-for-inequity/.

- Syechbubakr, Ahmad Syarif. 2024. “How do Indonesian businesspeople manage risks in electoral participation?” New Mandala. Accessed March 9, 2024: https://www.newmandala.org/how-do-indonesian-businesspeople-manage-risks-in-electoralparticipation/

- Szakonyi, David. 2021. “Private Sector Policy Making: Business Background and Politicians’ Behavior in Office.” The Journal of Politics 83 (1): 260–276.

- Tempo. 2019. “Pengusaha Kuasai Parlemen,” October 5. Accessed March 10, 2024: https://majalah.tempo.co/read/nasional/158519/pengusaha-kuasai-parlemen.

- Tempo. 2023. “17 Deretan Bisnis Kaesang Pangarep Yang Bakal Maju Di Pilwalkot Depok – Metro Tempo.Co,” June 12. Accessed March 10, 2024: https://metro.tempo.co/read/1736386/17-deretan-bisnis-kaesang-pangarep-yang-bakal-maju-di-pilwalkot-depok.

- Turner, Mark, Eko Prasojo, and Rudiarto Sumarwono. 2022. “The Challenge of Reforming Big Bureaucracy in Indonesia.” Policy Studies 43 (2): 333–351.

- Warburton, Eve. 2015. “The Business of Politics in Indonesia.” Inside Indonesia. Accessed March 10, 2024: https://www.insideindonesia.org/the-business-of-politics-in-indonesia.

- Warburton, Eve. 2018. “A New Developmentalism in Indonesia?” Journal of Southeast Asian Economies 35 (3): 355–368.

- Warburton, Eve. 2023. Resource Nationalism in Indonesia: Booms, Big Business, and the State. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Weschle, Simon. 2022. “Politicians’ Private Sector Jobs and Parliamentary Behavior.” American Journal of Political Science (September). Accessed March 16, 2024: https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12721.

- Winters, Jeffrey A. 2013. “Oligarchy and Democracy in Indonesia.” Indonesia 96 (1):11–33.

- The World Bank. 2020. “Aspiring Indonesia: Expanding the Middle Class.” Accessed March 10, 2024: https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/indonesia/publication/aspiring-indonesia-expanding-the-middle-class.

- www.jpnn.com. 2023. “Sandiaga Berbagi Tips kepada Gen Z NTB untuk Lahirkan Wirausahawan Muda,” October 15. Accessed March 10, 2024: https://www.jpnn.com/news/sandiaga-berbagi-tips-kepada-gen-z-ntb-untuk-lahirkan-wirausahawan-muda.