ABSTRACT

Children have a right to Comprehensive Sexuality Education (CSE). A key place for this to occur is in schools, and teachers’ comfort and competence in teaching is critical to delivering high-quality CSE. Good quality Initial Teacher Education (ITE) should provide student teachers with a strong foundation for the delivery of CSE and the creation of safe, supportive, and inclusive classrooms and whole-school cultures. This study examined primary ITE students’ perceptions of the quality of input, knowledge and confidence, and attitudes towards Relationships and Sexuality Education (RSE). The study was conducted in Ireland where RSE is mandatory in the primary school curriculum. The level of input student teachers received in RSE was perceived to be insufficient, and less than that provided in other curricular areas. Student teachers reported moderate to high levels of perceived knowledge and comfort in RSE domains and high levels of commitment and intention to teach RSE once qualified. They overwhelmingly agreed that children and young people have the right to RSE. Student teachers reported being particularly unprepared to teach RSE to students with special educational needs and sexual and gender minority students. Recommendations are made for strengthening RSE input in ITE programmes.

Introduction

The provision of Comprehensive Sexuality Education (CSE) is a fundamental right for children and young people (Campbell Citation2016; Daly and O’Sullivan Citation2020). Beyond the right to education and information itself, sexuality education supports the realisation of a wide range of children’s rights from health and wellbeing to protection, participation, identity and equality (Bourke, Mallon, and Maunsell Citation2022). CSE can have immediate and lifelong benefits for children and young people, by promoting a climate of inclusion, particularly relating to Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, Intersex (LGBTQI+)Footnote1 and gender issues (Campbell Citation2016; Proulx et al. Citation2019; Montgomery and Knerr Citation2018); by protecting against abuse and exploitation; and by addressing issues such as bodily integrity and autonomy, sexual consent, and gender relations (Campbell Citation2016). It supports the optimisation of sexual health (Montgomery and Knerr Citation2018) and psychological wellbeing (Allen and Rasmussen Citation2017; Montgomery and Knerr Citation2018).

While there are diverse sources of sexuality education, school-based education has the potential for the near universal delivery of a CSE programme, ideally one that is standardised, age-appropriate and scientifically accurate (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) Citation2018; Pound, Langford and; Campbell Citation2016; Pound et al. Citation2017). Indeed, children and young people themselves have expressed that they want to have sexuality education provided to them through school (Tanton et al. Citation2015) while at the same time they have described the school-based sexuality education they received as being out of touch with their lives and overly hetero- and cis-normative (Pound, Langford, and Campbell Citation2016).

CSE faces challenges not typically encountered by other areas of the curriculum. The development, discourse and implementation of CSE is strongly influenced and informed by the socio-political and historical landscape of the jurisdiction in which it is being provided (Sherlock Citation2012). Globally, disparities exist in terms of the content and approaches to school-based sexuality education, ranging from abstinence only to CSE (Zimmerman Citation2015). When sexuality education is provided, it frequently falls short of the international standards, and is not accurate or comprehensive (Campbell Citation2016). For example, a review of the formal guidance in England suggests contradictory discourses in which rights are ostensibly advanced, but remain structured by adult-centric, heteronormative understandings of sex and relationships (Setty and Dobson Citation2023). In their 2016 report for Ireland, the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child expressed concern at the severe lack of access to sexual and reproductive health education for adolescents and discrimination towards LGBTQI+ children and young people in Ireland (United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child Citation2016).

In Ireland, RSE is mandatory; however, provision is neither universal nor uniform, and young people have reported dissatisfaction with the RSE they received in Irish schools (Department of Education and Skills Citation2017; Lodge, Duffy, and Feeney Citation2022) (supplemental online Appendix A provides an overview of Relationships and Sexuality Education (RSE) in the primary curriculum in Ireland). Although curriculum content guidelines have been set, how RSE content is taught can be influenced by a myriad of factors, including the moral and political values of the teacher and ethos of the school (Jo and Reiss Citation2022). Although there is limited research in the area, school ethos is frequently cited as a barrier to the objective and factual delivery of RSE in Irish schools where almost 90% of schools are under the patronage of the Catholic Church (Hyland and Brian Citation2016; Dáil Éireann debate -Wednesday Citation2021). In 2018, a review of the existing RSE curriculum in Ireland was announced. This came after a series of public events in which the importance of RSE was highlighted, including marches against sexual violence, the passing of the repeal of the eighth amendment (on abortion), and the broader #MeToo movement. More recently, however, Ireland has seen an increase in violence and hate crimes directed at sexual and gender minority communities (Garda Síochána Citation2023; Gallagher and O’Riodan Citation2023) and increased online hate speech targeting the LGBTQI+ community (Gallagher, O’Connor, and Visser Citation2023).

Implementation of a comprehensive RSE curriculum is predicated on several factors. Teacher comfortability is one of the key components of high-quality and effective CSE (Lodge, Duffy, and Feeney Citation2022) and teachers’ competence and confidence is one of the gaps repeatedly highlighted in respect of the consistent implementation of CSE in schools (e.g. Pound et al. Citation2017). Poor confidence, competence, and comfortability in CSE can result in certain topics (e.g. LGBTQI+ issues, sex positivity etc) not being taught while other issues such as physical health are frequently privileged in the teaching of RSE, but are frequently taught without critical evaluation (Hargreaves et al. Citation2018; Lamb Citation2013; Barrie and Smith Citation2015).

While student teachers’ favourable attitudes, confidence, and self-efficacy to teach CSE are associated with positive intentions to teach CSE in the future, insufficient mastery of the subject can temper those intentions (Nuñez, Derluyn, and Valcke Citation2019). Conceptualisations of professional competence in teaching broadly are multidimensional and include cognitive (professional knowledge) and dynamic-affective (professional beliefs and motivational orientations) domains (Baumert and Kunter Citation2013; Blömeke Citation2017). Knowledge, both actual and perceived, is a critical component to such professional competence and there is a significant research gap in this area. To date, only one published study has evaluated pre-service teachers’ knowledge of CSE topics, which found that pre-service teachers had an ‘average knowledge’ of RSE (Nuñez, Derluyn, and Valcke Citation2019).

The potential of teacher education to respond to the opportunities and challenges presented in CSE is significant and upheld internationally as ‘ … one of the crucial levers of success of quality sexuality education programmes and projects’ (World Health Organization WHO Citation2017, 17). Teacher education has been found to be associated with greater student teacher knowledge (Murray, Swennen, and Kosnik Citation2019) and greater self-efficacy and intent to teach CSE (O’Brien, Hendriks, and Burns Citation2021) and the delivery of high-quality sexuality education in schools (Ezer et al. Citation2021). However, the provision of sexuality education in Initial Teacher Education (ITE) warrants significant enhancement (Ketting, Brockschmidt, and Ivanova Citation2021; O’Brien, Hendriks, and Burns Citation2021; Ollis, Harrison, and Maharaj Citation2013; Pound et al. Citation2017; Barrie and Smith Citation2015).

Pound et al. (Citation2017) in their international review recommends the following for effective provision of RSE. RSE should: be ‘sex positive’; reflect sexual diversity; include content on consent, sexting, cyberbullying, online safety, sexual exploitation and coercion; challenge inequality and gender stereotyping; be culturally sensitive; have a ‘whole-school’ ethos; provide impartial sexual health content; discuss relationships and emotions; not overemphasise risk; be co-produced with young people. However, research indicates that what ITE teachers received and considered important largely diverged from those suggested by Pound et al. (Citation2017) and hetero-normative and cis-normative assumptions appeared to underpin what many ITE teachers considered to be important topics for inclusion in RSE (e.g. Costello et al. Citation2022; Goldman and Grimbeek Citation2016; O’Brien, Hendriks, and Burns Citation2021).

Teacher education institutions are often strongly guided by national policies and school curricula as opposed to international guidelines, consequentially teachers are often inadequately prepared to teach CSE during ITE (O’Brien, Hendriks, and Burns Citation2021). In their review of sexuality education across Europe, Ketting, Brockschmidt, and Ivanova (Citation2021) commented on the generally poor level of teacher training for CSE across a number of countries, including Ireland, noting it to be ad-hoc and voluntary, despite the mandatory status of CSE in schools.

Given the critical role of good quality teacher education in the delivery of comprehensive, accurate and developmentally-appropriate RSE, this study examines student teachers’ preparation at ITE to teach RSE across perceived knowledge, comfort and attitudinal domains, and their future orientations to the teaching of RSE once qualified. This will be examined in a sample of ITE students undertaking primary level ITE. The study addressed the following research questions:

What preparation do students on primary ITE programmes receive on RSE?

What is the level of perceived knowledge across RSE topics among primary ITE students?

What is the level of comfort across RSE topics among primary ITE students?

What are primary ITE students’ attitudes to RSE?

Do they view RSE as a children’s rights issue?

Are they committed to the teaching of RSE?

What age do they think children should start RSE?

Do they think RSE should be provided in schools?

Do they think the religious ethos of the schools should be considered when teaching RSE?

What are primary ITE students’ intentions to teach RSE once qualified?

Methodology

The study, was part of a larger investigation entitled the TEACH-RSE Teacher Professional Development and RSE research project (Maunsell et al. Citation2021). It was approved by the Research Ethics Committee at Dublin City University. Informed consent was obtained electronically prior to participation. A quantitative self-report methodology was employed in the study which used a cross-sectional anonymous online survey.

Sample

The sample consisted of 118 student teachers studying for a qualification in Primary Education across four sites of ITE in the Republic of Ireland. An initial sample of 244 respondents were recruited and commenced the survey but only those who completed at least 70% of the survey were retained (n = 118). Inclusion criteria required that respondents were undertaking a programme of study in ITE, had received input on RSE as part of their ITE programme, and were at least 18 years of age.

shows that the sample comprised relatively young, principally heterosexual, female, primary school student teachers, predominantly in the later stages of their ITE programmes. All the respondents who responded to the nationality question (‘what is your nationality?’) were Irish, although only 45% of the sample answered this question. Respondents were not particularly religious given that just over one-third of respondents (38%) indicated that religion was important to them.

Table 1. Sample demographic characteristics (n = 118).

Procedure and survey

In the absence of available standardised tools, a survey instrument was designed for the purposes of this study, drawing on international frameworks and guideline documents for the delivery of sexuality education, empirical literature, and from consultation with experts in RSE (including members of the research team) and two student reviewers. The design recommendations of Krosnick (Citation1999) were used to guide the quality development of the survey instrument. For the purposes of this research paper, the following scales and items were used:

A Demographic and Initial Teacher Education (ITE) programme-level factors survey examined demographic factors, including age, gender identification, nationality, sexual orientation, religiosity, and the stage and programme of study being undertaken.

An ITE preparation survey was developed to examine perceived levels of preparedness to teach RSE at ITE. It consisted of the following questions.

‘How much input have you had in RSE?’ Responses were on four-point response scale: ‘more than enough’, ‘enough’, ‘not enough’ and ‘none’.

‘Compared with other subject areas, how would you rate your professional preparation at ITE level to teach RSE?’ Responses were on a 5-point labelled Likert scale from 1 ‘much worse’ to 5 ‘much better’.

Seven questions asked respondents to rate their professional preparation at ITE level to teach RSE to seven different student groups: ‘Children and adolescents with special educational needs’, ‘Sexual minority children and adolescents’, ‘Gender minority children and adolescents’, ‘Children and adolescents from LGBTQI parented families’, ‘Children and adolescents who are members of the travelling community’, ‘Children and adolescents from diverse cultural backgrounds’, ‘Children and adolescents at risk of early school leaving’. Responses were given on a five-point Likert scale from 1 ‘very unprepared’ to 5’very prepared’.

Two further questions examined preparation opportunities at ITE – teaching opportunities and reflection opportunities; ‘My Initial Teacher Education provided sufficient opportunities for RSE teaching practice’ and ‘My Initial Teacher Education provided opportunities to reflect on my own perspectives related to RSE’. Responses were given on a five-point labelled Likert scale from 1 ’strongly disagree’ to 5’strongly agree’. On each of the aforementioned scales, higher scores reflect higher levels of the measured constructs.

A Perceived Knowledge and Comfort survey examined participants’ levels of perceived knowledge and comfort across ten content domains derived from the WHO-BZgA Standards for Sexuality Education in Europe (World Health Organisation WHO/Regional Office for Europe & Federal Centre for Health Education BZgA Citation2010). Each content domain, with accompanying Cronbach’s alpha, and the reflected topics are presented in . Each item was presented to respondents in the same order within the domains and for each item respondents were asked to rate their knowledge on that topic from 1 (‘no knowledge’) to 5 (‘excellent knowledge’), and their level of comfort for teaching the topic from 1 (‘extremely uncomfortable’) to 5 (‘extremely comfortable’). For each domain, responses were scored by averaging the total number of items, yielding 20 overall domain scores (i.e. 10 perceived knowledge and 10 comfort scores). Higher scores represented higher levels of knowledge and comfort.

Table 2. Topics included in each of the 10 domains of the perceived knowledge and comfort survey.

Attitudes to RSE. Respondents were asked about their attitudes to the following four statements. Responses to these statements were scored on a 5pt Likert-type scale that ranged from 1= strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree with higher scores indicating more agreement with the statements.

‘Children (under 12 years) have a right to RSE’

‘Adolescents (over 12 years) have a right to RSE’

‘RSE should be provided in all Primary Schools’

‘The religious ethos (denominational/multi-denominational ethos, etc.) of the school should be considered when teaching RSE’

A further question asked respondents at what age they thought RSE should start.

Future Orientation. Respondents also rated their commitment to teach RSE on a five-point Likert scale from 1 (extremely uncommitted) to 5 (extremely committed), and their intention to teach RSE when qualified on a five-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

The survey was administered online using Qualtrics software (Qualtrics, Provo, UT). Respondents were asked to complete the survey independently and were given seven days from the time that they logged into the survey to complete it. Participation was estimated to take 30 minutes. The order of questions was the same for all participants. Data collection took place between February and April 2020 at the height of the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in Ireland.

All analyses were conducted in IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 27). Valid percentages are presented in all text except in and where missing values are presented.

Results

ITE preparation to teach RSE

Respondents were asked about the amount of input they had had on RSE. Of respondents who responded to this question (n = 92), 4.3% (n = 4) reported that they had no RSE input in ITE, 61% (n = 56) reported not having enough input, and 34% (n = 31) reported that they had ‘enough’ or ‘more than enough’ input. Of note, one inclusion criterion was that respondents had received some input in RSE.

shows the level of reported input across the years of study in the programme. Of the respondents who answered this question and who were in the final year of their programme (n = 30), 87% (n = 26) reported having received ‘none’ or ‘not enough’ input in RSE.

Table 3. Number of participants across level of input received in RSE (n = 92) and across year of programme.

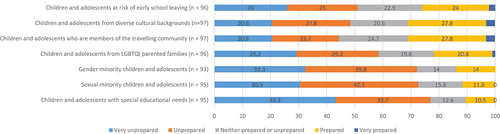

In comparison to their preparation for other subject areas, for which n = 94 responses were recorded, 63% of respondents who answered this question (n = 59) reported that their RSE preparation was ‘worse’ or ‘much worse’ than in other subject areas, 32% (n = 30) reported it was ‘neither better nor worse’, and 5.4% (n = 5) reported it was ‘better’ or ‘much better’. shows respondents’ ratings of their preparation to teach RSE to groups of children and adolescents. In general, respondents on these question (n = 93–96) reported a lack of preparedness for teaching RSE to the groups assessed. In particular, the lowest rating of preparedness was reported for teaching RSE to children and adolescents with special education needs (i.e. 77% reported being very unprepared or unprepared), sexual minority children and adolescents (73% very unprepared/unprepared), and gender minority children and adolescents (72% very unprepared/unprepared).

Figure 1. Professional preparation to teach RSE to groups of children and adolescents expressed as a percentage of total number of responses for each question.

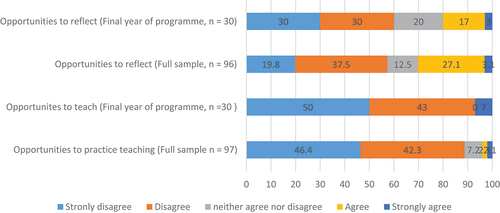

shows the data for the two teaching and practice opportunity provision questions. The data shows that of all the respondents who replied to this question (n = 97), only 4.2% of respondents (n = 4) ‘agreed’/’strongly agreed’ that they were provided with sufficient opportunities to practice teaching RSE and 88.7% (n = 86).

Figure 2. Provision of teaching and practice opportunities across stages of programme expressed as a percentage of responses for each question.

Of the respondents who replied to the opportunities to reflect item (n = 96), 30.2% of respondents ‘agreed’/’strongly agreed’ that they were provided with sufficient opportunities to reflect on their own perspectives related to RSE; 57.3% (n = 55) ‘strongly disagreed’/’disagreed’ with this statement. The data also show that 93% of students in the final year of their programme who responded to this question (n = 30) (data was collected in the final semester of their programme) ‘strongly disagreed’ or ‘disagreed’ that they were provided with opportunities to teach RSE and nearly 57% (n = 17) of the same students were provided with opportunities to reflect on RSE.

Perceived knowledge and comfort with RSE topics

Participants rated their knowledge and comfort related to RSE topics. Their responses are presented in . Alkharusi’s (Citation2022) approach to interpreting the descriptive findings from Likert scale data was employed. Scores falling into the interval of 1–2.33 were deemed ‘Low level of Perceived Knowledge/Comfort’; scores falling into the interval of 2.34–3.67 were deemed a ‘Moderate level of Perceived Knowledge/Comfort’; and scores falling into the interval of 3.68–5.00 were deemed a ‘High level of Perceived Knowledge/Comfort’.

Table 4. Overall mean and standard deviation response scores (per topic domain) for RSE perceived knowledge and comfort (n = 118).

indicates that perceived knowledge and comfort for all categories ranged from moderate to high. Descriptively, teaching Family Structures, Relationships and Lifestyle, and Emotions, respectively, received the highest comfort ratings, and teaching about Sexual Abuse and Coercion. Sexuality: Behaviour and Identity, and Fertility and Reproduction, respectively, received the lowest ratings for comfort. Respondents rated their highest level of knowledge teaching about Sexuality: Rights, Emotions, and the Human Body and Human Development, respectively, and their lowest rating of knowledge was for teaching about Sexual Abuse and Coercion, Sexuality: Behaviour and Identity, Sexuality: Health and Wellbeing, respectively.

Attitudes towards RSE

Perceptions of children’s right to RSE

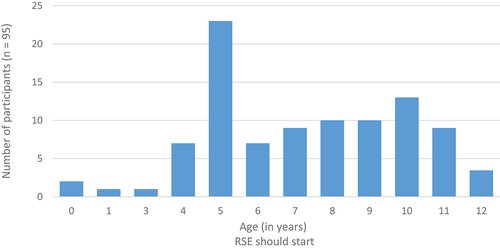

When asked about whether ‘children (under 12 years)’ have a right to RSE, respondents (n = 96) overwhelmingly ‘agreed’/’strongly agreed’ (i.e. 93%, compared with 5% who ‘neither agreed nor disagreed’ and 2% who ‘disagreed’). All respondents (i.e. n = 98) ‘agreed’/’strongly agreed’ that ‘adolescents (over 12 years)’ have a right to RSE. Respondents also rated the age at which they believed that RSE should start (n = 95). The responses are presented in and range from 0 to 12 years (Mean = 7 years, SD = 2.7, Mode = 5 years). Of these respondents, 12% (n = 11) believed RSE should start 0–4 years; 52% (n = 49) 5–8 years; 37% (n = 35) 9–12 years.

Provision of RSE in primary schools and role of school ethos

Respondents were asked whether they thought RSE should be provided in all Primary Schools. Respondents overwhelmingly agreed with this statement. Of those who answered this question (n = 97), 99% agreed that RSE should be provided in all primary schools. Respondents were asked whether the religious ethos of the school should be considered when teaching RSE (n = 97). The majority (i.e. 55%, n = 53) disagreed/strongly disagreed with the notion that the religious ethos of the school should be considered when teaching RSE. Just over one fifth of respondents to this question were neutral (i.e. 22%, n = 21; neither agreeing nor disagreeing) and just below one quarter of respondents (i.e. 24%, n = 23) suggested that religious ethos should be considered.

Commitment to RSE

Respondents rated how committed they are to teach RSE. Of those who responded to this question (n = 91), 85.7% (n = 78) of respondents reported being ‘committed’ or ‘extremely committed’, 12% (n = 11) were ‘neither committed nor uncommitted’, and 2% (n = 2) were ‘uncommitted’.

Future orientation to teach RSE

Respondents (n = 94) were asked whether they intended to teach RSE in the future (i.e. post qualifying as teachers). Ninety-four percent of respondents (n = 88) ‘agreed’ or ‘strongly agreed’ that they intended to teach RSE when qualified and 6% (n = 6) neither agreed nor disagreed; no respondents disagreed with this statement.

Discussion

Good quality ITE preparation for the teaching of CSE is crucial to the quality of its implementation in schools (World Health Organization WHO Citation2017). The findings from this study come at a crossroads in Irish education as steps are taken to review, develop, and roll out new curricula for RSE. The study ddresses significant gaps in the literature on input, knowledge, and confidence of ITE students. Evidence from this study indicates generally positive attitudes among student teachers to RSE in that they view children as having a right to RSE, they are highly committed to teaching it, but nonetheless feel less well prepared to teach it compared to other school subject areas.

Taken together the findings from this study suggest that student teachers were not sufficiently prepared to teach RSE in their ITE. A majority of respondents reported having received either not enough or no RSE input during their initial teacher education and that the level of input was less than that of other areas of the curriculum. This suggests a lower status of RSE relative to other curricular areas at ITE and echoes international findings (O’Brien, Hendriks, and Burns Citation2021; Ketting, Brockschmidt, and Ivanova Citation2021; Barrie and Smith Citation2015; Ollis, Harrison, and Maharaj Citation2013). These are concerning findings, especially as the inclusion criteria for participation in the survey required that respondents had received some input in RSE, and it does not reflect the full cohort of students who received no input in RSE. Respondents also reported being unprepared to teach RSE to specific groups of children, particularly children and adolescents with special education needs, sexual minority children and adolescents.

Opportunities to practise teaching and to reflect on that practice are central to the acquisition of professional competency (Harrison and Ollis Citation2015; Brown Citation2016) and survey findings indicate that such opportunities are lacking for RSE in Ireland. Only a very small proportion of respondents indicated having had the opportunities to practise teaching RSE as part of their ITE. Slightly more respondents reported having had opportunities to engage in self-reflection with respect to RSE, albeit still quite low and with a small sample size. A World Health Organization (WHO) (Citation2017) report on the development of sexuality education in Europe stresses the importance and willingness of teachers to reflect on their own attitudes and social norms as an important prerequisite to teaching sexuality education, and sexual attitudes reassessment or values clarification has been an integral part of sexuality education and training since the 1990s (Sitron and Dyson Citation2009).

Professional knowledge is a key component of professional competency (Baumert and Kunter Citation2013; Blömeke Citation2017) as are less tangible affective components such as attitudes and comfort with teaching RSE (Nuñez, Derluyn, and Valcke Citation2019; Lodge, Duffy, and Feeney Citation2022). This study found moderate to high levels of perceived knowledge and comfort across ten RSE content domains derived from the WHO-BZgA Standards for Sexuality Education in Europe (World Health Organisation WHO/Regional Office for Europe & Federal Centre for Health Education BZgA Citation2010), although with much variation in the responses. The finding that student teachers were least knowledgeable and least comfortable teaching about sexual abuse and coercion is concerning given the important role RSE can play in terms of protection from these issues (Bourke, Mallon, and Maunsell Citation2022; Campbell Citation2016) and echoes more general research on the barriers to engagement with child protection matters in schools (Bourke and Maunsell Citation2016; Buckley and McGarry Citation2011).

Almost all respondents reported being ‘committed’ or ‘extremely committed’ to teaching RSE, and indicated an intention to teach RSE when qualified. A substantial proportion of the student teachers viewed RSE as a child’s right. This is a promising finding given the critical role of teachers as the enablers of children’s rights and the enabling of Article 29 of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (‘the development of the child’s personality, talents and mental and physical abilities to their fullest potential’ (UN General Assembly Citation1989, 9). These findings echo those from previous research in Ireland that found that Social Personal and Health Education (SPHE), and by extension RSE, were perceived by teachers as offering an enabling environment for education about human rights generally, and children’s rights more specifically (Waldron and Oberman Citation2016).

When looking at the age at which that participants believed RSE should start, age five was reported by the largest proportion of respondents (24%) but the overall average (mean) across the full group of participants was 7 years. Just over one in ten respondents believed it should start younger, at between 0 and 4 years. This latter finding is concerning, given the importance of RSE as a means to address relationship, identity development and schema formation in early childhood. For example, if CSE does not begin until age seven, heteronormative and cisnormative ideas may already be internalised and important opportunities for protecting young children from sexual abuse will have missed.

With respect to religious ethos, a substantial minority of respondents suggested that the religious ethos of the school should be considered when teaching RSE but over half of the respondents disagreed with this. While religious ethos is frequently cited in public discourse related to RSE, there is limited published research on the topic.

Limitations

Some considerations should be borne in mind when interpreting the results of this study. The sample size was relatively small, predominantly female, heterosexual and cisgender and so caution should be exercised in relation to the generalisability and inferences to be drawn from the findings. In addition, we pooled data from undergraduate and postgraduate teachers, however there may be important differences between these groups’ attitudes and values to explore in future work. We did not look for any urban-rural differences that might have been present in the results. Given that the proportion of the population living in rural areas in Ireland is higher than the EU average this is another issue worth future exploration.

Overall, there was a low response rate and large amount of missing data, which is not untypical for a self-report study of this kind (Wu, Zhao, and Fils-Aime Citation2022). A review of the missing data indicated that the knowledge and comfort variables were those most affected. Future larger-scale investigations in this domain might seek to remedy this deficiency. The first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in Ireland commenced during data collection which likely affected some participants’ engagement.

Conclusion

This study set out to examine student teachers’ attitudes to, and preparedness to teach, RSE. The findings indicate that this sample of Irish student teachers had generally positive attitudes towards, and were committed to teaching RSE. However, they were not very well prepared to teach RSE and the input they received in ITE was considerably lacking. Good quality input in RSE is necessary to prepare teachers to provide good quality comprehensive sexuality education in the context of a rapidly changing world where recent progression in gender and LGBTQI+ issues and sexual violence, has been accompanied by increased hate crime and homophobic, transphobic and misogynistic online content (e.g. Gallagher, O’Connor, and Visser Citation2023).

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the input of Dr Aisling Costello for her advice in design of the study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. A variety of acronyms are used in the studies reported throughout this paper (e.g. some studies did not include transgender or intersex participants, or ask questions about these individuals in their surveys.

References

- Alkharusi, H 2022. “A Descriptive Analysis and Interpretation of Data from Likert Scales in Educational and Psychological Research.” Indian Journal of Psychology and Education 12 (2): 13–16

- Allen, L, and M. L. Rasmussen, eds. 2017. The Palgrave Handbook of Sexuality Education. London: Palgrave Macmillan

- Barrie, S, and S. J. Smith. 2015. “‘A Lot More to Learn Than Where Babies Come From’: Controversy, Language and Agenda Setting in the Framing of School-Based Sexuality Education Curricula in Australia.” Sex Education 15 (6): 641–654

- Baumert, J, and M. Kunter. 2013. “The COACTIV Model of Teachers’ Professional Competence.” In Cognitive Activation in the Mathematics Classroom and Professional Competence of Teachers: Results from the COACTIV, edited by M. Kunter, J. Baumert, U. Klusmann, W. Blum, S. Krauss and M. Neubrand, 25–48. Boston, MA: Springer.

- Blömeke, S 2017. “Modelling Teachers’ Professional Competence As a Multi-Dimensional Construct.” In Pedagogical Knowledge and the Changing Nature of the Teaching Profession, edited by S. Guerriero, 119–135. Paris: OECD Publishing

- Bourke, A, B. Mallon, and C. Maunsell. 2022. “Realisation of Children’s Rights Under the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child To, In, and Through Sexuality Education.” International Journal of Children’s Rights 30 (2): 271–296

- Bourke, A, and C. Maunsell. 2016. “‘Teachers matter’: The Impact of Mandatory Reporting on Teacher Education in Ireland.” Child Abuse Review 25 (4): 314–324

- Brown, A. 2016. “‘How Did a White Girl Get AIDS?’ Shifting Student Perceptions on HIV-Stigma and Discrimination at a Historically White South African University.” South African Journal of Higher Education 30 (4): 94–111.

- Buckley, H, and K. McGarry. 2011. “Child Protection in Primary Schools: A Contradiction in Terms or a Potential) Opportunity?” Irish Educational Studies 30 (1): 113–128

- Campbell, M 2016. “The Challenges of Girls’ Right to Education: Let’s Talk About Human Rights-Based Sex Education.” International Journal of Human Rights 20 (8): 1219–1243

- Costello, A, C. Maunsell, C. Cullen, and A. Bourke. 2022. “A Systematic Review of the Provision of Sexuality Education to Student Teachers in Initial Teacher Education.” Frontiers in Education 7: 787966

- Dáil Éireann debate -Wednesday, 24 Nov 2021. Accessed 15 January 2023. from https://www.oireachtas.ie/en/debates/debate/dail/2021-11-24/

- Daly, A, and C. O’Sullivan. 2020. “Sexuality Education and International Standards: Insisting Upon Children’s Rights.” Human RightsQ, 4 (42): 835.

- Department of Education and Skills. 2017. Lifeskills Survey. Dublin: Department of Education and Skills

- Ezer, P, C. M. Fisher, T. Jones, and J. Power. 2021. “Changes in Sexuality Education Teacher Training Since the Release of the Australian Curriculum.” Sexuality Research & Social Policy 19: 1–10

- Gallagher, A, C. O’Connor, and F. Visser. 2023. “Uisce Faoi Thalamh an Investigation into the Online Mis- and Disinformation Ecosystem in Ireland.” Institute for Strategic Dialogue. Accessed 15 March 2023. https://www.isdglobal.org/isd-publications/uisce-faoi-thalamh-summary-report/

- Gallagher, C, and A. O’Riodan. 11 23, 2023. “Yousef Palani Jailed for Life for Murder of Aidan Moffitt and Michael Snee in Sligo.” The Irish Times. Accessed 15 January 2023. https://www.irishtimes.com/crime-law/courts/2023/10/23/double-murderer-yousef-palani-jailed-for-life-for-attacks-on-gay-men-spurred-by-hostility-and-prejudice/

- Garda Síochána, A 2023. “Hate Crime Statistics.” Accessed 1 February 2023. https://www.garda.ie/en/information-centre/statistics/

- Goldman, J. D, and P. Grimbeek. 2016. “What do Preservice Teachers Want to Learn about Puberty and Sexuality Education? An Australian Perspective.” Pastoral Care in Education 34 (4): 189–201

- Hargreaves, A, D. Shirley, S. Wangia, C. Bacon, and M. D’Angelo. 2018. Leading from the Middle: Spreading Learning, Well-Being, and Identity Across Ontario. Toronto: Council of Ontario Directors of Education

- Harrison, L, and D. Ollis. 2015. “Stepping Out of Our Comfort Zones: Pre-Service Teachers’ Responses to a Critical Analysis of Gender/Power Relations in Sexuality Education.” Sex Education 15 (3): 318–331

- Hyland, Á, and B. Brian. 2016. “Religion, Education and Religious Education in Irish Schools.” In Religious Education in a Global-Local World. Boundaries of Religious Freedom: Regulating Religion in Diverse Societies, edited by J. Berglund, Y. Shanneik, and B. Bocking, 123–133. Vol. 4. Cham: Springer

- Jo, S, and M. J. Reiss. 2022. “Faith-Sensitive RSE in Areas of Low Religious Observance: Really?” Sex Education 22 (1): 52–67

- Keating, S., M. Morgan, and B. Collins. 2018. “Relationships and Sexuality Education (RSE) in Primary and Post-Primary Irish Schools.” Dublin: NCCA.

- Ketting, E, L. Brockschmidt, and O. Ivanova. 2021. “Investigating the ‘C’in CSE: Implementation and Effectiveness of Comprehensive Sexuality Education in the WHO European Region.” Sex Education 21 (2): 133–147

- Krosnick, J. A 1999. “Survey Research.” Annual Review of Psychology 50 (1): 537–567

- Lamb, S 2013. “Just the Facts? The Separation of Sex Education from Moral Education.” Educational Theory 63 (5): 443–460. doi:10.1111/edth.12034

- Lodge, A, M. Duffy, and M. Feeney. 2022. “‘I Think it Depends on Who You Have, I was Lucky I Had a Teacher Who Felt Comfortable Telling All This Stuff’. Teacher Comfortability: Key to High-Quality Sexuality Education?” Irish Educational Studies 43 (2): 1–18.

- Maunsell, C, A. Bourke, A. Costello, C. Cullen, and M. Machowska-Kosciak. 2021. TEACH-RSE Teacher Professional Development and Relationships and Sexuality Education: Realising Optimal Sexual Health and Wellbeing Across the Lifespan: Findings from the TEACH-RSE Research Project. Dublin: Dublin City University.

- Maycock, P., K. Kitching, and M. Morgan. 2007. Relationships and Sexuality Education (RSE) in the Context of Social, Personal and Health Education (SPHE): An Assessment of the Challenges to Full Implementation of the Programme in Post-Primary Schools. Dublin: Crisis Pregnancy Agency, Department of Education and Science.

- Montgomery, P, and W. Knerr. 2018. Review of the Evidence on Sexuality Education: Report to Inform the Update of the UNESCO International Technical Guidance on Sexuality Education. Paris: UNESCO

- Murray, J, A. Swennen, and C. Kosnik. 2019. “International Research, Policy and Practice in Teacher Education.” In International Policy Perspectives on Change in Teacher Education: Insider Perspectives, edited by J. Murray, C. Kosnik and A. Swennen, 1–14. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Nuñez, J. C, I. Derluyn, and M. Valcke. 2019. “Student Teachers’ Cognitions to Integrate Comprehensive Sexuality Education into Their Future Teaching Practices in Ecuador.” Teaching & Teacher Education 79: 38–47

- O’Brien, H, J. Hendriks, and S. Burns. 2021. “Teacher Training Organisations and Their Preparation of the Pre-Service Teacher to Deliver Comprehensive Sexuality Education in the School Setting: A Systematic Literature Review.” Sex Education 21 (3): 284–303

- Ollis, D, L. Harrison, and C. Maharaj. 2013. “Sexuality Education Matters: Preparing Pre-Service Teachers to Teach Sexuality Education.” Melbourne: Deakin University.

- Pound, P, S. Denford, J. Shucksmith, C. Tanton, A. M. Johnson, J. Owen, R. Hutten, et al. 2017. “What is Best Practice in Sex and Relationship Education? A Synthesis of Evidence, Including Stakeholders’ Views.” British Medical Journal Open 7 (5): e014791

- Pound, P, R. Langford, and R. Campbell. 2016. “What do Young People Think About their School-Based Sex and Relationship Education? A Qualitative Synthesis of Young People’s Views and Experiences.” British Medical Journal Open 6 (9): e011329

- Proulx, C., R. Coulter, J. Egan, D. Matthews, and C. Mair. 2019. “Associations of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Questioning–Inclusive Sex Education with Mental Health Outcomes and School-Based Victimization in US High School Students.” Journal of Adolescent Health 64 (5): 608–614.

- Setty, E, and E. Dobson. 2023. “Department for Education Statutory Guidance for Relationships and Sex Education in England: A Rights-Based Approach?” Archives of Sexual Behavior 52 (1): 79–93

- Sherlock, L 2012. “Sociopolitical Influences on Sexuality Education in Sweden and Ireland.” Sex Education 12 (4): 383–396

- Sitron, J. A, and D. A. Dyson. 2009. “Sexuality Attitudes Reassessment (SAR): Historical and New Considerations for Measuring Its Effectiveness.” American Journal of Sexuality Education 4 (2): 158–177

- Tanton, C, K. G. Jones, W. Macdowall, S. Clifton, K. R. Mitchell, J. Datta, R. Lewis, et al. 2015. “Patterns and Trends in Sources of Information about Sex among Young People in Britain: Evidence from Three National Surveys of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles.” British Medical Journal Open 5 (3): e007834

- UN General Assembly. 1989. “Convention on the Rights of the Child.” United Nations, Treaty Series 1577:3. 20 November 1989

- United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child. 2016. “Concluding Observations on the Combined Third and Fourth Periodic Reports of Ireland. New York/Geneva: United Nations CRC/C/IRL/CO/3–4.

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). 2018. International Technical Guidance on Sexuality Education: An Evidence-Informed Approach. Paris: UNESCO

- Waldron, F, and R. Oberman. 2016. “Responsible Citizens? How Children are Conceptualised as Rights Holders in Irish Primary Schools.” International Journal of Human Rights 20 (6): 744–760

- World Health Organisation (WHO)/Regional Office for Europe & Federal Centre for Health Education BZgA. 2010. Standards for Sexuality Education in Europe: A Framework for Policy Makers, Educational and Health Authorities and Specialists. Cologne: Federal Centre for Health Education - BZgA.

- World Health Organization (WHO). 2017. Training Matters: A Framework for Core Competencies of Sexuality Educators. Cologne: Federal Centre for Health Education - BZgA.

- Wu, M.-J, K. Zhao, and F. Fils-Aime. 2022. “Response Rates of Online Surveys in Published Research: A Meta-Analysis.” Computers in Human Behavior Reports 7: 100206.

- Zimmerman, J 2015. Too Hot to Handle: A Global History of Sex Education. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Appendix A

An overview of Relationships and Sexuality Education (RSE) on the Irish primary curriculum

At the time of data collection (early 2020), RSE in Ireland followed the 1999 Primary School Curriculum; however a major review of the RSE curriculum was underway at the time, including the re=drafting of the Primary Curriculum. Since the late 1990s, RSE has been a compulsory part of the primary curriculum. RSE is delivered as an aspect of Social Personal and Health Education (SPHE) in the Primary School Curriculum.

A child’s right to Social, Personal and Health Education was enshrined in law in the Education Act, 1998. Section 9 of the Act states that every school shall use its available resources ‘to promote the moral, spiritual, social and personal development of students and to provide health education for them, in consultation with their parents and having regard to the characteristic spirit of the school’. At the same time, the Irish constitution recognises parents as the primary educators of their children and while Relationships and Sexuality Education is a mandatory part of the curriculum in schools, parents have a right to request that their child opt out of RSE, as is their right with any aspect of the curriculum.

A Department of Education survey of RSE in 2017 reported that 94% of schools had an RSE policy in place. The same survey found that the majority of primary schools reported that teaching RSE was either challenging (62%) or very challenging (12%) and there was a high reliance on outside expertise in delivering the RSE programme (48% of schools) (Department of Education and Skills Citation2017).

Relationships and Sexuality Education (RSE) involves teaching and learning about the cognitive, emotional, physical and social aspects of relationships and sexuality. It aims to equip children and young people, in an age-appropriate manner, with the knowledge, skills, attitudes and values that will enable them to develop self-awareness and self-esteem; realise their health, wellbeing and dignity; develop positive and respectful, social and intimate relationships; consider how their choices affect their own wellbeing and that of others; and understand their rights and responsibilities in relation to themselves and others (Department of Education).

In their review of RSE in Irish schools, Keating, Morgan, and Collins (Citation2018) note that RSE in Irish schools is multi-faceted, with varying experiences across schools, students and parents. It should also be noted that the majority of primary schools in Ireland (87%) are under the patronage of the Catholic church a factor that is often noted when the context of RSE implementation of in schools (e.g. Maycock, Kitching, and Morgan Citation2007).