ABSTRACT

Viewing sexually explicit media (SEM) can influence young people’s sexual attitudes and behaviours. Media literacy education can help young people navigate this, yet parental opposition is sometimes cited as a barrier to the implementation of comprehensive school programmes. A scoping review explored parent perspectives towards and comfort with SEM literacy education, parent-focused resources, and the level of parental engagement in resource development. An expansive view of SEM included pornography alongside sexually explicit content in movies, television shows, video games, or other online spaces. Collectively, a focused search of five academic databases, an online search for grey literature and resources from non-governmental and government organisations, and interviews (n = 7) with key stakeholders were undertaken. Screening reduced 4,745 peer-reviewed records to seven. The online search located 35 resources from 28 organisations. While parents support SEM literacy education for their children, other sexuality education topics (e.g. contraception and the prevention of sexually transmitted infections) were more widely endorsed. Parental comfort in providing such education was variable. Online resources vary in type and content, with limited information available about development processes or evaluation. Further research and co-design are needed to ascertain parent needs to support their children’s SEM literacy knowledge and understanding.

Background

In Australia, young people learn about sex, sexual health and relationships from various sources including schools, parents and families, peers and media (Power et al. Citation2022). Media and online sources are consistently identified as key sources of information, often more so than parents and schools (Ezer et al. Citation2019; Waling, Fraser, and Fisher Citation2020; Power et al. Citation2022). Online environments provide easy access to a plethora of diverse resources which young people value exploring privately to avoid embarrassment (Waling, Farrugia, and Fraser Citation2023). Online sources also provide access to sexually explicit media (SEM) and pornography, which Australian young people are more likely to view unintentionally in their pre-pubescent years, and intentionally throughout adolescence for pleasure (eSafety Commissioner Citation2023) and education (Power et al. Citation2022).

Globally, young people’s access to pornography is high and commences early in life. A recent survey (n = 1,000) found 79% of young people aged 16 to 21 in the UK had viewed pornography before turning 18, with the average age of first viewing being 13 (Children’s Commissioner for England Citation2023). A nationally representative survey of adolescents (aged 14 to 18) in the USA found 68.4% had viewed pornography (Wright, Herbenick, and Paul Citation2020). A survey of 2,071 young people aged 14 to 17 in New Zealand found 75% had viewed pornography by the age of 17, and 27% by the age of 12 (Office of Film and Literature Classification Citation2018). Similarly, Australian research demonstrates that 75% of 16 to 18 year-olds surveyed (n = 1,004) had viewed online pornography, with 13 being the average age of first viewing (eSafety Commissioner Citation2023).

Published literature reveals a range of perspectives and outcomes for young people viewing pornography. Whilst young people know pornography is unrealistic and may impact their relationships, they also find it useful to learn about sexual behaviours (Baker Citation2016; Office of Film and Literature Classification Citation2018; Waling et al. Citation2019). Attitudinally, whilst pornography use can influence sexual attitudes to be more gender-egalitarian (Kohut, Baer, and Watts Citation2016), it has also been associated with problematic attitudes regarding sexual violence (Peter and Valkenburg Citation2016; Quadara, El-Murr, and Latham Citation2017) and young women reporting harmful sexual experiences often depicted in pornography (Davis et al. Citation2020). Behaviourally, pornography viewing may help develop self-confidence and positive sexual identity by encouraging exploration of different sexual acts (Rothman et al. Citation2018). Similarly, there have been reported associations between pornography use and increased engagement in unprotected sex and early sexual debut (Smith et al. Citation2016).

Experiences of pornography differ across diverse population groups. For example, young people with diverse sexualities or gender identities (McCormack and Wignall Citation2017; Grant and Nash Citation2019) and young people with disabilities (McCann, Marsh, and Brown Citation2019; Botfield et al. Citation2021) report finding material more representative of their own experiences. For example, research with non-heterosexual men has found viewing pornography helped with identity exploration and sexual technique development (McCormack and Wignall Citation2017), while also negatively impacting body satisfaction and expectations of sexual partners (Leickly, Nelson, and Simoni Citation2017). Recent research has outlined a number of criteria for assessing if pornography may be beneficial for healthy sexual development for young adults aged 18 to 25 years. These criteria include pornography that shows various body types, genders, ethnicities and sexual activities that are safe, portray consent negotiation and pleasure for all involved and is produced ethically (McKee, Dawson, and Kang Citation2023).

Discussions in the literature regard pornography literacy as an approach aimed at increasing young people’s skills to critically appraise messages in the material viewed and increasing awareness of the potential harms associated with viewing SEM (Davis et al. Citation2020). The approach is grounded in media literacy theory (Pinkleton et al. Citation2012) and is viewed as a harm reduction strategy to mitigate potential negative impacts of pornography viewing (Davis et al. Citation2020). Research has found merit in literacy content going beyond a focus on potential risks alone, as this can perpetuate shame, potentially increasing resistance to any educative efforts (Dawson, Nic Gabhainn, and MacNeela Citation2020). Young people report wanting robust, pornography-specific education that respects their agency (eSafety Commissioner Citation2023). Because of this, didactic approaches may not be as effective as those that encourage young people to think critically about pornography (Goldstein Citation2020). Pornography can complement or challenge the lessons taught as part of broader comprehensive sexuality education (CSE). A systematic review regarding pornography use for educational purposes, found it useful for learning about having sex and different sexualities, while ultimately providing insufficient information, confirming the need for more effective sex education (Litsou et al. Citation2021). Furthermore, young people believe that a pornography literacy curriculum should reduce shame towards viewing pornography; develop critical analysis skills with respect to body image, realistic expectations of sex, sex and gender-based violence; and provide information specific to gay and transgender people (Dawson, Nic Gabhainn, and MacNeela Citation2020). Wider research supports the effectiveness of health-focused media literacy interventions (Vahedi, Sibalis, and Sutherland Citation2018), including for developing positive sexuality attitudes (Pinkleton et al. Citation2012).

Research consistently documents the positive impacts on sexual health knowledge and attitudes that good quality CSE can provide when delivered in schools (UNESCO Citation2018; Goldfarb and Lieberman Citation2021). In line with international best practice, a comprehensive sexuality curriculum is best supported by the use of a whole-school approach to sex and relationship education (Norozi Citation2023). This kind of approach includes a focus on the curriculum and school policy, together with broader family and community engagement, and partnerships with local services and organisations (Cefai, Caravita, and Simoes Citation2021), recognising that education takes place in a variety of contexts, not just through formal classroom instruction. Because of this, a whole-school approach requires partnership with families (Sawyer, Raniti, and Aston Citation2021), since perceived and actual parental reactions can impact what content is delivered and to what depth (Goldman Citation2008; Igor, Ines, and Aleksandar Citation2015; Millner, Mulekar, and Turrens Citation2015). Furthermore, parents are key to helping their children develop literacy skills for both general media (Liang and Jingyuan Citation2018) and SEM (Baker Citation2016).

This scoping review aimed to explore the perspectives of parents with respect to the provision of SEM literacy education; and existing resources and programmes to help them fulfil their role as SEM educators. The research took an expansive view of SEM, inclusive of pornography and highly sexualised imagery in films, television shows, video games, online or on social media. This kind of approach recognises the differing definitions of pornography in the literature (McKee et al. Citation2020) and the ability of a wide range of media to influence attitudes towards sexuality (Pinkleton et al. Citation2012). Throughout the study, the phrase parent is used to denote all parents and carers of young people.

Method

This study followed the methodological framework proposed by Arksey and O’Malley (Citation2005) for scoping reviews, as enhanced by various researchers over time (Westphaln et al. Citation2021). This framework’s six stages were: identifying the research question; identifying relevant studies; study selection; charting the data; collating, summarising and reporting results; and the integration of expert consultation.

Research questions

The following research questions guided the review:

What are the perspectives of parents, who currently have a child in secondary school, with respect to SEM literacy education (school-based or otherwise)?

How comfortable are parents discussing SEM with their children?

What SEM literacy education resources or programmes exist for parents?

What degree of parental involvement occurred in their development?

Identifying relevant studies

Search strategy

The search strategy was designed to gather peer-reviewed literature, grey literature and online resources that provided guidance to parents on the education of their children about SEM. This broad-based strategy allowed for the inclusion of materials developed by organisations that may not have published their programmes in academic literature.

To ensure a comprehensive sample of peer-reviewed literature, five online databases were searched: Web of Science (Core), ProQuest, Medline, PsycInfo and ScienceDirect. An additional search using Google Scholar was conducted after these databases had been exhausted. The first 20 results pages of Google Scholar were included in keeping with best practice (Haddaway et al. Citation2015).

Search terms

The same search terms were used to locate peer-reviewed literature, as well as grey literature and online resources. Search terms were divided into four categories as follows: sexually explicit media, parents, students, and education. Subsequent lists of search terms were developed for each category as detailed in search terms.

Table 1. Search terms.

Selecting literature

Inclusion criteria

Literature (both peer-reviewed and grey) was included if it assessed parental perspectives towards SEM education (school-based or otherwise) and/or outlined the development of, or evaluated a resource or programme. Both qualitative and quantitative study designs were included. Only studies published in the English language after 2012 were included.

Studies that assessed parental perspectives towards SEM education yielded few results in initial searches. CSE is often discussed as a holistic concept encompassing many topics. Therefore, it was decided to expand the search to include parental perspectives towards CSE and include studies with a specific measure for SEM. Similarly, early attempts to focus solely on Australian publications did not yield a large number of results, therefore the search was expanded to include countries comparable to Australia. These included English-speaking, high-income countries as defined by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).Footnote1 The term ‘children’ was included as a broader search term, so that studies were not limited to the secondary school age group.

While the grey literature search was conducted using the incognito setting, it was still subject to the Google algorithm, filtering resources not published in English. Organisation referral pages were also cross-checked to ensure these resources were captured; and stakeholders engaged for expert interviews (detailed below) were asked to nominate and if necessary provide resources they knew of that the Google search might have missed.

Exclusion criteria

Literature not published in the English language or prior to 2012 was excluded. Studies were also excluded if they did not discuss parental engagement in the development of the resource. Studies that assessed parental perspectives on CSE were excluded if they did not contain a measure specific to SEM. Similarly, studies assessing perspectives with respect to one aspect of CSE that was not SEM were excluded.

Charting the data

Two spreadsheets were developed to collate the peer-reviewed data, and the grey literature and online resource data separately. The second and third authors then confirmed eligibility of all inclusions, with consensus received on all.

Collating, summarising and reporting the results

Findings relevant to the research questions were summarised from each of the selected peer-reviewed studies and collated (see online supplemental material, table A). Online resources located via Google and those provided by interviewed stakeholders were summarised separately (see online supplemental material, table B) by programme or resource name, resource type (programme, course, written or online resource for example), host organisation, content description, target audience, parental engagement in development, year developed, current availability, evaluation status and results, associated publications, and country of origin. Information not available online formed the basis for the interviews with stakeholders from the host organisations.

Integration of expert consultation

Stakeholders identified throughout the searches were emailed directly and invited to participate in an interview to gather more information about the resource development process. If they agreed, stakeholders were emailed an online consent form and participant information sheet. A follow-up email was sent within a month if no response was received. The Curtin University Human Research Ethics Committee approved the study (HRE2022–0191).

Results

Peer reviewed literature

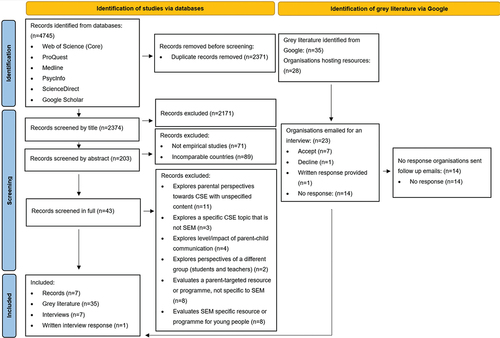

outlines the selection process for the peer reviewed and grey literature. Database searching was undertaken in January 2023. A total of 4,745 records were identified through database searches. After duplicates had been removed, the remaining records were screened first by title, then abstract and finally, underwent a full-text review. The reasons that some records were excluded during the full-text review are outlined in . Seven records were included.

Grey literature and online resources

Initial Google searches took place in January and February 2023, with a secondary search being conducted in November 2023. A total of 35 grey literature documents or online resources, developed by 28 different organisations were identified.

Stakeholder interviews

Nine of the 23 organisations identified in the January/February Google searches responded to an interview request; with one declining, one opting to provide written responses to the questions, and seven interviews being conducted between January and April 2023. Five additional organisations were located in the November 2023 search, however they were not approached for an interview. Interview data is included in tabulated results (see online supplemental material, table B).

Parent perspectives towards SEM education

Six of the peer-reviewed studies assessed parent perspectives and came from Australia (n = 3), Canada (n = 2); and New Zealand (n = 1). Of these, four assessed parental perspectives towards CSE with specific measures for various topics including SEM or pornography (Hendriks et al. Citation2023; McKay et al. Citation2014; Robinson, Smith, and Davies Citation2017; Wood et al. Citation2021) and two explored perspectives towards pornography literacy specifically (Davis et al. Citation2021; Healy-Cullen et al. Citation2022). Parental support for schools delivering CSE and SEM literacy education was high, although the latter generally scored lower than for other CSE topics.

A nationally representative survey of 2,427 Australian parents found widespread support for a total of 40 CSE topics across both primary and secondary school grades. Most parents (89.9%) strongly agreed/agreed that schools should provide CSE and only 3.87% expressly disagreed/strongly disagreed with its delivery. Among the 40 topics endorsed, two topics related to SEM: media literacy skills related to sexual content in advertising, TV, pornography etc. and the influence of SEM (e.g. pornography). These topics received notably lower support than others, with media literacy skills ranking 30th and the influence of SEM at 35th out of 40. Support was however, still overwhelmingly high in the sample at 94.77% for media literacy skills and 92.63% for the influence of SEM (Hendriks et al. Citation2023).

An earlier study of 1,002 parents in Ontario, Canada, found similar strong support for sexual health education implementation. Only 2% of respondents stated that sexual health education should not be provided in schools at all. Respondents rated media literacy as ‘important’ (possible score 1–4; mean 3.1) to teach students, however it was deemed less important amongst the other 12 topics assessed (McKay et al. Citation2014).

A similar study was conducted nationally in Canada in 2021, with 85% of the parent sample strongly agreeing/agreeing with sexual health education implementation in schools. All 33 topics assessed received high levels of support, including media literacy skills related to sexual content in advertising, TV, pornography, etc. (93.2%) and sexuality and communication technology (e.g.‘sexting’) (94.3%) (Wood et al. Citation2021).

A mixed-methods study of Australian parents found widespread support for sexuality education provision to primary school students. The survey of 342 parents/carers found 71% (n = 242) of respondents believed sexuality education to be both relevant and important to their primary school aged children. Underlying reasons behind these views were explored qualitatively. The sample reported sexuality education as important for developing media literacy skills in children to counter common narratives about sexuality expressed in various media. Across the survey, interviews and focus groups conducted as part of the study, parents felt it essential to build young girls’ awareness and critical analysis skills of media that sexualises female bodies. Despite 71% of the sample supporting school-based sexuality education, there were reported concerns that its content could conflict with values parents wanted to teach their children. Parents with both traditional and progressive views on sexuality expressed this concern, with more progressive parents citing concerns originating from their own negative experiences of school-based sexuality education (Robinson, Smith, and Davies Citation2017).

A study in New Zealand explored the perspectives of young people, their parents, and educators towards pornography literacy education (Healy-Cullen et al. Citation2022). Thirty participants completed an online Q-sort and then consented to follow-up interviews. Fifteen participants were parents (6 men and 9 women), all of whom progressed to interview except for one female. This same study revealed two discourses, a pragmatic response, in which pornography literacy is viewed as essential in a world where pornography is unavoidable; and a harm minimisation approach which favoured teaching young people about the harms of viewing pornography and censoring their access (Healy-Cullen et al. Citation2022). This interpretation of what ‘harm minimisation’ might involve is different to the recognised public health use of the term, which aims to reduce the harms associated when SEM is viewed, rather than promote abstinence-only (Crabbe and Flood Citation2021). More parents were aligned to the pragmatic response stance, believing censorship approaches to be sex negative, judgemental and likely ineffective (Healy-Cullen et al. Citation2022). SEM literacy development was favoured as they believed that young people will inevitably view pornography (Healy-Cullen et al. Citation2022).

A qualitative study of Australian parents (n = 20) found greater support for school-based pornography literacy education than home-delivered education, to which parents perceived their children might be less receptive. There was a lack of consensus over what information should be taught, with views ranging from teaching that pornography had negative impacts and should not be viewed, to identifying specific illegal behaviours, to parents who supported the provision of comprehensive information about pornography, although these parents could not articulate what this would include (Davis et al. Citation2021).

Five studies asked parents to indicate in which year group it was most appropriate to commence CSE or SEM literacy specifically, with all reporting the first years of secondary school as the most appropriate age (McKay et al. Citation2014; Wood et al. Citation2021; Davis et al. Citation2021; Healy-Cullen et al. Citation2022; Hendriks et al. Citation2023). In Australia, parents reported grades 7 and 8 (ages 12 to 14) as the most appropriate to commence education for media literacy skills (36.72%) and the influence of SEM (36.09%) in one study (Hendriks et al. Citation2023); and between grades 7–10 (ages 12 to 16) in another study (Davis et al. Citation2021). While parents in Ontario, Canada were not asked about the age at which specific topics should be introduced, over one third (37%) believed implementation should begin in primary school (grades 1 to 6, ages 6 to 12) as part of sexual health education. Nearly half (47%) believed middle school (grades 6 to 8, ages 11 to 14) and 14% secondary school (grades 9 to 12, ages 14 to 18) as the appropriate time for sexual health education (McKay et al. Citation2014). Parents participating in the 2021 Canadian study were asked about ideal age to begin for each topic. For media literacy skills related to sexual content in advertising, TV, pornography, etc., the middle grades were favoured with 18.6% preferring grades 4–5; 33.1% grades 6–8 and 22.7% grades 9–10. This was similar for sexuality and communication technology (e.g .‘sexting’), with the majority preferring grades 6–8 (39.7% or grades 9–10 (20.6%) (Wood et al. Citation2021). Parents in New Zealand aligned with a pragmatic response reported 16-years-of-age as too late to commence pornography literacy education, with 13 years being a better age to do so, and felt ongoing lessons were more beneficial than one-off teaching sessions (Healy-Cullen et al. Citation2022).

Parents comfort with engaging their children in conversations about SEM

Three studies explored parent comfort in engaging with their children about SEM specifically, with comfort levels being dependent on the type of conversation (Robinson, Smith, and Davies Citation2017; Davis et al. Citation2021; Healy-Cullen et al. Citation2022). In a New Zealand study, parents aligned with a pragmatic response reported some discomfort and awkwardness in discussing pornography with their children and therefore valued expert input. Those aligned with a harm minimisation approach were more likely to see themselves as the best provider of pornography literacy education for their children, to ensure it aligned with their own values. Those aligned with this stance also favoured education that emphasised the negative impacts of pornography as opposed to promoting a critical analysis of pornographic material (Healy-Cullen et al. Citation2022). Australian parents in one study reported they were unlikely to discuss pornography at home as they found it controversial, and also expressed concern about schools providing education on pornography (Robinson, Smith, and Davies Citation2017).

The majority of parents in another Australian study preferred open dialogue with their children about pornography over censoring approaches and reported comfort with such conversations. Despite this, most had not initiated conversations with their children, citing hesitation until they were sure their child had been exposed to such material. Members of this sample reported wanting practical resources to help identify if their child’s pornography viewing could be considered normal or problematic. While participants in this study did not reach consensus on what should be taught as part of pornography literacy, an evidence-based curriculum was favoured, provided parents were given clear guidance to support their children’s learning at home (Davis et al. Citation2021).

Two studies explored parent comfort in providing CSE generally, as well as their preferred sources of this education for their children. Parents in Ontario, Canada rated themselves as either very comfortable (37%) or comfortable (52%) discussing sexual health with their child. Parents strongly agreed (33%) and agreed (50%) that their knowledge was sufficient to provide sexual health education to their children. Mothers were significantly more likely to rate themselves comfortable with having these discussions and to consider themselves sufficiently knowledgeable to educate their children, than fathers were. Parents in this study were either not very comfortable or not at all comfortable with five other sources of sexual health education for their children: fictional books, friends of their child/ren, the Internet, other media, and social media (McKay et al. Citation2014). An Australian parent sample found 65% believed the provision of sexuality education to be a shared responsibility between schools and the home (Robinson, Smith, and Davies Citation2017).

What education resources/programmes on SEM education exist for parents?

Online supplemental Table B outlines the resources found. Content type ranged from website content and downloadable fact sheets, to online presentations and webinars provided both in person on request and in downloadable recordings, as well as online courses and material supporting workshops provided in person. Two hard copy books were identified for parents generally (Talk Soon, Talk Often, WA Department of Health Citation2019) and for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families (Yarning Quiet Ways, WA Department of Health Citation2015).

Resources covered a variety of topics, but mainly focused on informing parents about the impact of SEM viewing on young people and how to engage their children in conversations about SEM, including advice and conversation starters (e.g. Outspoken Sex Education). Some resources also included information about online safety, particularly in relation to making and sending SEM (e.g. Netsafe NZ, eSafety Commissioner). Resources also included information about measures to reduce their children’s access, as well as guidance about how to respond if their child is discovered having viewed SEM (e.g. Culture Reframed). Many resources were specific to pornography, but some took a broader view of SEM (e.g. Culture Reframed, Raising Children’s Network).

Media Aware Parent is a programme aimed at assisting parents to communicate with adolescent aged children about sexual imagery in the media (Scull et al. Citation2019). Short-term efficacy was evaluated with 355 pairs of parents or caregivers (172 intervention; 183 control), and their children, aged 12 to 15 years. While both groups reported comfort with the online format and having learned something new, parents in the intervention group reported stronger feelings that the resource would help them discuss sex and relationships with their children (Scull et al. Citation2019).

Degree of parental involvement in resource development

Many online resources did not provide any information about how they had been developed, with much of the relevant data being revealed through stakeholder (expert) interviews (see online supplemental Table B). Data were found for 10 resources. Commonalities in the development process include the use mixed-methods such as literature reviews, desktop reviews of other education providers and school curricula, surveys, focus groups and interviews with parents, young people, educators and experts in sexual health and education, in various combinations. The book resource for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander parents had been developed with relevant communities through a yarning process (WA Department of Health Citation2015). Media Aware Parent had undergone pilot testing with parents prior to its launch (Scull et al. Citation2019).

Evaluation data was limited, with only the Media Aware Parent resource formally publishing this data (Scull et al. Citation2019). However, all stakeholders interviewed stated their resources were regularly revised in response to parental feedback, alongside additional unpublished evaluation data gathered through quality assurance processes such as online surveys and website analytics.

Discussion

This scoping review examined parental perspectives towards SEM literacy education and reviewed existing resources that sought to support parents as educators. The review highlighted widespread parental support for CSE and SEM literacy education, but found a lack of research on how parents view SEM literacy education. Most identified resources had not been formally or rigorously evaluated. This review located only two studies that directly assessed parent perspectives towards literacy education specific to pornography (Davis et al. Citation2021; Healy-Cullen et al. Citation2022) suggesting that further research is required.

Parents in studies conducted in Australia, Canada and New Zealand expressed high levels of support for CSE and its implementation across primary and secondary schools (Hendriks et al. Citation2023; McKay et al. Citation2014; Robinson, Smith, and Davies Citation2017; Wood et al. Citation2021). Whilst this support extended to SEM literacy, the topic was not as strongly endorsed as other CSE topics (Hendriks et al. Citation2023; McKay et al. Citation2014; Wood et al. Citation2021). This disparity may reflect a disconnect between parent’s own sexuality education and the relatively recent advent of social media, streaming services and online devices like smartphones and tablets that enable prolonged viewing. Notably, two of the included studies were published prior to the introduction of social media applications such as TikTok (McKay et al. Citation2014; Robinson, Smith, and Davies Citation2017). This generational shift may explain why many of the available resources include information on SEM viewing prevalence and impacts for young people, to help parents come to understand SEM literacy as equally important to other CSE topics.

Australian research from over a decade ago found parental concern about the media’s impact on their children’s perceptions of relationships (Ollis, Harrison, and Richardson Citation2012), suggesting these concerns pre-date newer media forms. While the literature on parent perspectives towards SEM literacy is less well developed, a small qualitative study of Australian parents (n = 8) attitudes towards pornography literacy education (published after the end of this review) reported that its sample parents thought schools could be doing more to educate students about pornography within the existing health education curriculum (Burke et al. Citation2023). This, alongside the evidence collected in this review and the well-developed international evidence showing high parental support for CSE (Igor, Ines, and Aleksandar Citation2015; Hendriks et al. Citation2023; Millner, Mulekar, and Turrens Citation2015; Wood et al. Citation2021), means that educators should feel confident to deliver SEM literacy content, however a specific review of research examining educator perspectives is warranted.

While parents were generally comfortable engaging their children in discussion about sex and relationships, this comfort decreased when discussing SEM. Parents aligned to the harm reduction approach described by Healy-Cullen et al. (Citation2022) considered themselves the best providers of SEM education, although this group also favoured more restrictive approaches over media literacy development. This supports the idea that developing critical SEM analysis skills is lesser known among parents who may require awareness raising. Currently unpublished data from the Hendriks et al. (Citation2023) study, cited in personal communication, revealed that the sample had high levels of comfort talking about sexual health issues with their children, but the frequency of such discussion was minimal. Other research demonstrates that while parents often have the ability, they generally lack the confidence to discuss pornography with their children (Burke et al. Citation2023), suggesting further research into parent needs, and the development of resources to meet these needs, is required.

While this review found a variety of resources seeking to increase awareness and to build the capacity of parents to help their children navigate the influence of SEM, limited academic evidence was provided to assess the rigour behind existing resource development. Similarly, there was little formal evidence regarding useability, effectiveness or impact, with the exception of the positive evaluation results for Media Aware Parent (Scull et al. Citation2019). Some resources are promoted across a variety of websites which can lead to spiralling searches. There is also limited information about which websites and resources are the most credible, which can cause confusion about what information constitutes best-practice or is evidence-based, as recommended by the World Health Organization and UNESCO (Citation2021). The resources located contained widely varied information at different depths. This highlights an opportunity for co-design approaches to identify parental needs from SEM literacy resources (LaMonica et al. Citation2022). It would be beneficial for such resources to be consistent with content taught in schools, to help parents support their children’s learning at home (Davis et al. Citation2021; Ollis, Harrison, and Richardson Citation2012).

Students view schools as trustworthy sources of information on CSE (Power et al. Citation2022), however they commonly report that school-based programmes are heteronormative, overly focused on the biological aspects of sex, and negatively framed (Pound, Langford, and Campbell Citation2016). Australian young people believe they should have agency over their pornography viewing habits, as well as robust sexuality education, including information specific to pornography (eSafety Commissioner Citation2023). Australian research supports the introduction of pornography literacy within existing health education curricula (Davis et al. Citation2020), and parents are generally supportive of SEM literacy education (Burke et al. Citation2023; Hendriks et al. Citation2023; Davis et al. Citation2021; Robinson, Smith, and Davies Citation2017). Parents and young people are also comfortable with health professionals providing sexual health information (Waling, Fraser, and Fisher Citation2020). Evidence suggests merit in a whole-school approach to addressing these issues in school involving all these stakeholders, as suggested by Crabbe and Flood’s (Citation2021) practice framework.

This framework proposes an approach to SEM literacy that aims to support young people’s agency to develop safe and respectful sexual relationships, rejecting approaches based in stigma and shame (Crabbe and Flood Citation2021), similar to the pragmatic response discourse described by Healy-Cullen et al. (Citation2022) and in line with young people’s own preferred approach (eSafety Commissioner Citation2023). The SEM literacy information currently available to parents is often negatively-framed, focusing on reducing the extent of young people’s viewing habits and stressing the harms linked to the viewing of SEM. This may alienate people who view SEM, which should be a key concern given high viewing rates (Crabbe and Flood Citation2021). Research exploring parental perspectives, needs and preferred resource types could also help inform a best practice, sex-positive SEM knowledge framework.

Strengths and limitations

The use of a flexible scoping review methodology strengthened this study by allowing for the inclusion of grey literature and online content that would have been missed by a systematic literature review. Similarly, stakeholder insights obtained via the interviews strengthened the initial findings with data not locatable in either peer-reviewed or grey literature. Presumably, parents looking for support engaging with their children about SEM would venture online for support and as such, reviewing the available online content is both essential and novel.

A limitation of this study however is the small number of peer-reviewed studies and resources included, perhaps reflecting the contemporary and rapidly changing nature of this topic. It is possible that search engines and databases with an education or social sciences focus may have yielded different results.

Content only existing as hard-copy resources and which lacked an online presence, would also have been missed. Similarly, it is possible that the online search strategy missed resources addressing SEM literacy as one of many topics, or where parents were one of many audiences. The impacts of these omissions were potentially mitigated by the inclusion of complementary stakeholder interviews.

Conclusion

This review has provided an analysis of how parents view SEM literacy education for their children and the content that currently exists to help them support their children in a context where SEM viewing is likely. The results can help organisations engage with parents to develop nuanced content that supports them as educators to help build young people’s critical analysis skills with respect to the SEM they consume. Researchers and educators are encouraged to identify opportunities to work together with parents, families and broader communities to develop SEM literacy frameworks that are adaptable to local contexts. This could guide future content creation and support implementation in schools and at home, which is especially salient in a context where SEM continues to play a sex and sexuality education role for young people.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (46.7 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the organisations who provided resources and participated in interviews, for their time and valuable contributions to the data in this scoping review.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2024.2338275

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Countries included the USA, the UK, New Zealand and Canada.

References

- Arksey, H., and L. O’Malley. 2005. “Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework.” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 8 (1): 19–32.

- Baker, K. E. 2016. “Online Pornography – Should Schools Be Teaching Young People About the Risks? An Exploration of the Views of Young People and Teaching Professionals.” Sex Education 16 (2): 213–228.

- Botfield, J. R., S. Ratu, E. Turagabeci, J. Chivers, L. McDonald, E. G. Wilson, and Y. Cheng. 2021. “Sexuality Education for Primary School Students with Disability in Fiji.” Health Education Journal 80 (7): 785–798.

- Burke, S., M. Purvis, C. Sandiford, and B. Klettke. 2023. ““It’s Not a One-Time Conversation”: Australian Parental Views on Supporting Young People in Relation to Pornography Exposure.” Psych 5 (2): 508–525. doi:10.3390/psych5020034.

- Cefai, C., S. C. S. Caravita, and C. Simoes. 2021. A Systemic, Whole-School Approach to Mental Health and Well-Being in Schools in the EU – Executive Summary. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

- Children’s Commissioner for England. 2023. ‘A Lot of it Is Actually Just abuse’ Young People and Pornography. London: Children’s Commissioner for England.

- Crabbe, M., and M. Flood. 2021. “School-Based Education to Address pornography’s Influence on Young People: A Best Practice Framework.” American Journal of Sexuality Education 16 (1): 1–37. doi:10.1080/15546128.2020.1856744.

- Davis, A. C., M. J. Temple-Smith, E. Carrotte, M. E. Hellard, and M. S. C. Lim. 2020. “A Descriptive Analysis of Young women’s Pornography Use: A Tale of Exploration and Harm.” Sexual Health 17 (1): 69–76.

- Davis, A. C., C. Wright, M. Curtis, M. E. Hellard, M. S. C. Lim, and M. J. Temple-Smith. 2021. “‘Not My child’: Parenting, Pornography, and Views on Education.” Journal of Family Studies 27 (4): 573–588. doi:10.1080/13229400.2019.1657929.

- Davis, A. C., C. Wright, S. Murphy, P. Dietze, M. J. Temple-Smith, M. E. Hellard, and M. S. C. Lim. 2020. “A Digital Pornography Literacy Resource Co-Designed with Vulnerable Young People: Development of “The Gist.” Journal of Medical Internet Research 22 (6). doi:10.2196/15964.

- Dawson, K., S. Nic Gabhainn, and P. MacNeela. 2020. “Toward a Model of Porn Literacy: Core Concepts, Rationales, and Approaches.” The Journal of Sex Research 57 (1): 1–15. doi:10.1080/00224499.2018.1556238.

- eSafety Commissioner. 2023. ‘Accidental, Unsolicited and in Your Face. Young people’s Encounters with Online Pornography: A Matter of Platform Responsibility, Education and Choice’. Australia: eSafety Commissioner.

- Ezer, P. L. K., C. M. Fisher, W. Heywood, and J. Lucke. 2019. “Australian students’ Experiences of Sexuality Education at School.” Sex Education 19 (5): 597–613.

- Goldfarb, E. S., and L. D. P. Lieberman. 2021. “Three Decades of Research: The Case for Comprehensive Sex Education.” Journal of Adolescent Health 68 (1): 13–27.

- Goldman, J. 2008. “Responding to Parental Objections to School Sexuality Education: A Selection of 12 Objections.” Sex Education 8 (4): 415:438.

- Goldstein, A. 2020. “Beyond Porn Literacy: Drawing on Young people’s Pornography Narratives to Expand Sex Education Pedagogies.” Sex Education 20 (1): 59–74. doi:10.1080/14681811.2019.1621826.

- Grant, R., and M. Nash. 2019. “Educating Queer Sexual Citizens? A Feminist Exploration of Bisexual and Queer Young Women’s Sex Education in Tasmania, Australia.” Sex Education 19 (3): 313–328.

- Haddaway, N. R., A. M. Collins, D. Coughlin, and S. Kirk. 2015. “The Role of Google Scholar in Evidence Reviews and Its Applicability to Grey Literature Searching.” PLOS ONE 10 (9). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0138237.

- Healy-Cullen, S., J. E. Taylor, T. Morison, and K. Ross. 2022. “Using Q-Methodology to Explore Stakeholder Views About Porn Literacy Education.” Sexuality Research & Social Policy 19 (2): 549–561.

- Hendriks, J., K. Marson, J. Walsh, T. Lawton, H. Saltis, and S. Burns. 2023. “Support for School-Based Relationships and Sexual Health Education: A National Survey of Australian Parents.” Sex Education. doi:10.1080/14681811.2023.2169825.

- Igor, K., E. Ines, and S. Aleksandar. 2015. “Parents’ Attitudes About School-Based Sex Education in Croatia.” Sexuality Research & Social Policy 12 (4): 323–334.

- Kohut, T., J. L. Baer, and B. Watts. 2016. “Is Pornography Really About “Making Hate to Women”? Pornography Users Hold More Gender Egalitarian Attitudes Than Nonusers in a Representative American Sample.” The Journal of Sex Research 53 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1080/00224499.2015.1023427.

- LaMonica, H. M., J. J. Crouse, Y. J. C. Song, M. Alam, M. Ekambareshwar, V. Loblay, and A. Yoon. 2022. “Developing a Parenting App to Support Young Children’s Socioemotional and Cognitive Development in Culturally Diverse Low- and Middle-Income Countries: Protocol for a Co-Design Study.” JMIR Research Protocols 11 (10). doi:10.2196/39225.

- Leickly, E., K. Nelson, and J. Simoni. 2017. “Sexually Explicit Online Media, Body Satisfaction, and Partner Expectations Among Men Who Have Sex with Men: A Qualitative Study.” Sexuality Research & Social Policy 14 (3): 270–274.

- Liang, C., and S. Jingyuan. 2018. “Reducing Harm from Media: A Meta-Analysis of Parental Mediation.” Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly 96 (1): 173–193. doi:10.1177/1077699018754908.

- Litsou, K., P. Byron, A. McKee, and R. Ingham. 2021. “Learning from Pornography: Results of a Mixed Methods Systematic Review.” Sex Education 21 (2): 236–252. doi:10.1080/14681811.2020.1786362.

- McCann, E., L. Marsh, and M. Brown. 2019. “People with Intellectual Disabilities, Relationship and Sex Education Programmes: A Systematic Review.” Health Education Journal 78 (8): 885–900.

- McCormack, M., and L. Wignall. 2017. “Enjoyment, Exploration and Education: Understanding the Consumption of Pornography Among Young Men with Non-Exclusive Sexual Orientations.” Sociology 51 (5): 975–991.

- McKay, A., S. E. Byers, S. D. Voyer, T. P. Humphreys, and C. Markham. 2014. “Ontario parents’ Opinions and Attitudes Towards Sexual Health Education in the Schools.” The Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality 23 (3): 159–166.

- McKee, A., P. Byron, K. Litsou, and R. Ingham. 2020. “An Interdisciplinary Definition of Pornography: Results from a Global Delphi Panel.” Archives of Sexual Behaviour 49 (3): 1085–1091. doi:10.1007/s10508-019-01554-4.

- McKee, A., A. Dawson, and M. Kang. 2023. “The Criteria to Identify Pornography That Can Support Healthy Sexual Development for Young Adults: Results of an International Delphi Panel.” International Journal of Sexual Health 35 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1080/19317611.2022.2161030.

- Millner, V., M. Mulekar, and J. Turrens. 2015. “Parents’ Beliefs Regarding Sex Education for Their Children in Southern Alabama Public Schools.” Sexuality Research & Social Policy 12 (2): 101–109.

- Norozi, S. A. 2023. “The Nexus of Holistic Wellbeing and School Education: A Literature-Informed Theoretical Framework.” Societies 13 (5): 113.

- Office of Film and Literature Classification. 2018. NZ Youth and Porn: Research Findings of a Survey on How and Why Young New Zealanders View Online Pornography. Wellington: Office of Film and Literature Classification.

- Ollis, D., L. Harrison, and A. Richardson. 2012. Building Capacity in Sexuality Education: The Northern Bay College Experience: Report of the First Phase of the Sexuality Education and Community Support (SECS) Project. Geelong: Deakin University.

- Peter, J., and P. M. Valkenburg. 2016. “Adolescents and Pornography: A Review of 20 Years of Research.” Journal of Sex Research 53 (4–5): 509–531.

- Pinkleton, B. E., E. W. Austin, Y. Y. Chen, and M. Cohen. 2012. “The Role of Media Literacy in Shaping Adolescents’ Understanding of and Responses to Sexual Portrayals in Mass Media.” Journal of Health Communication 17 (4): 460–476.

- Pound, P., R. Langford, and R. Campbell. 2016. “What Do Young People Think About Their School-Based Sex and Relationship Education? A Qualitative Synthesis of Young people’s Views and Experiences.” British Medical Journal Open 6 (9). doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011329.

- Power, J., S. Kauer, C. Fisher, R. Bellamy, and , and A. Bourne. 2022. The 7th National Survey of Australian Secondary Students and Sexual Health 2021. ARCSHS Monograph Series 133. Melbourne: The Australian Research Centre in Sex, Health and Society, La Trobe University.

- Quadara, A., A. El-Murr, and J. Latham. 2017. The Effects of Pornography on Children and Young People: An Evidence Scan. (Research Report). Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Robinson, K. H., E. Smith, and C. Davies. 2017. “Responsibilities, Tensions and Ways Forward: Parents’ Perspectives on children’s Sexuality Education.” Sex Education 17 (3): 333–347.

- Rothman, E. F., A. Adhia, T. T. Christensen, J. Paruk, J. Alder, and N. Daley. 2018. “A Pornography Literacy Class for Youth: Results of a Feasibility and Efficacy Pilot Study.” American Journal of Sexuality Education 13 (1): 1–17.

- Sawyer, S. M., M. Raniti, and R. Aston. 2021. “Making Every School a Health-Promoting School.” The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health 5 (8): 539–540.

- Scull, T. M., C. V. Malik, E. M. Keefe, and A. Schoemann. 2019. “Evaluating the Short-Term Impact of Media Aware Parent, a Web-Based Program for Parents with the Goal of Adolescent Sexual Health Promotion.” Journal of Youth & Adolescence 48 (9): 1686–1706.

- Smith, L. W., B. Liu, L. Degenhardt, J. Richters, G. Patton, H. Wand, and D. Cross 2016. “Is Sexual Content in New Media Linked to Sexual Risk Behaviour in Young People? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Sexual Health 13 (6): 501–515.

- UNESCO. 2018. Revised Edition: International Technical Guidance on Sexuality Education: An Evidence-Informed Approach. Paris: UNESCO.

- Vahedi, Z., A. Sibalis, and J. E. Sutherland. 2018. “Are Media Literacy Interventions Effective at Changing Attitudes and Intentions Towards Risky Health Behaviors in Adolescents? A Meta-Analytic Review.” Journal of Adolescence 67 (1): 140–152. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2018.06.007.

- WA Department of Health. 2015. Yarning Quiet Ways. Perth: WA Department of Health.

- WA Department of Health. 2019. Talk Soon.Talk Often. A Guide for Parents Talking to Their Kids About Sex. Perth: WA Department of Health.

- Waling, A., A. Farrugia, and S. Fraser. 2023. “Embarrassment, Shame, and Reassurance: Emotion and Young People’s Access to Online Sexual Health Information.” Sexuality Research & Social Policy 20 (1): 45–57.

- Waling, A., S. Fraser, and C. Fisher. 2020. Young People and Sources of Sexual Health Information (ARCSHS Monograph Series No. 121). Melbourne: Australian Research Centre in Sex, Health and Society, La Trobe University.

- Waling, A., L. Kerr, S. Fraser, A. Bourne, and M. Carman. 2019. Young People, Sexual Literacy, and Sources of Knowledge: A Review. (ARCSHS Monograph Series No. 119). Melbourne: Australian Research Centre in Sex, Health and Society, La Trobe University.

- Westphaln, K. K., W. Regoeczi, M. Masotya, B. Vazquez-Westphaln, K. Lounsbury, L. McDavid, H. Lee, J. Johnson, and S. D. Ronis. 2021. “From Arksey and O’Malley and Beyond: Customizations to Enhance a Team-Based, Mixed Approach to Scoping Review Methodology.” MethodsX 8: 101375. doi:10.1016/j.mex.2021.101375.

- Wood, J., A. McKay, J. Wentland, and S. E. Byers. 2021. “Attitudes Towards Sexual Health Education in Schools: A National Survey of Parents in Canada.” The Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality 30 (1): 39–55.

- World Health Organization and UNESCO. 2021. Making Every School a Health-Promoting School. Global Standards and Indicators. Geneva: World Health Organization and UNESCO.

- Wright, P. J., D. Herbenick, and B. Paul. 2020. “Adolescent Condom Use, Parent-Adolescent Sexual Health Communication, and Pornography: Findings from a U.S. Probability Sample.” Health Communication 35 (13): 1576–1582.